DIRECTIONS: You will submit a total of 3 separate posts for this unit.1) Answer any THREE of the nine questions listed below. You may pick three questions from the same chapter or three ques

Chapter 7

The Madman and the Death of God

Nietzsche is here pointing to the gradual erosion of religious belief already visible in late nineteenth-century Europe. The belief in God, the parable suggests, has lost its hold on the collective consciousness of the West. The morning newspaper has replaced the morning prayer. Our concern with what St. Thomas Aquinas called the Summum Bonum (salvation and eternal life, the highest objects of human striving) has been supplanted by the petty bourgeois virtues of industriousness, thrift, and enlightened self-interest—all with an eye toward achieving no higher goal than mere comfortable self-preservation (what Nietzsche elsewhere refers to as “the green meadow happiness of the herd”). The great cathedrals of Europe are fast becoming “the tombs and monuments of God,” mere tourist attractions much like the Parthenon in Athens is today.

What are the implications of this momentous event? For Nietzsche they are catastrophic. The death of God signals a crisis of meaning the likes of which mankind has never before seen; the entire horizon that once gave the West its unique cultural identity and self-understanding has been wiped clean. To invoke Plato’s famous allegory, there are no longer any shadows on the cave wall because the fire has been extinguished. The sun (representing God), which once formed the moral and existential center of our universe, has been torn away from us. The madman carries a lantern in the morning light because only he recognizes that the world has been cast into the darkness: “I come too early…I am not yet at the right time. This prodigious event is still on its way, and is traveling—it has not yet reached men’s ears.” His prophetic insight into the frightful consequences of the death of God is thus seen by his derisive and uncomprehending fellow unbelievers as a sign of madness.

Ivan Karamozov, one of the chief characters in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1880 masterpiece The Brothers Karamozov, famously proclaims: “If God does not exist, then nothing is true and everything is permitted.” What he means is that, without the Creator God of Judeo-Christianity, man has no essence or nature, and hence no intrinsic purpose. The universe is devoid of any eternal, divine, or natural law in the Thomistic[1] sense (since there is no God to conceive it), and without these there can be no cosmic basis for justice or morality. We are slowly becoming conscious of inhabiting a world deprived of any moral absolutes, a world in which there are no longer any restraints on our conduct other than those established by human law or custom. We are literally free-falling in the Abyss; “Whither do we move? Away from all suns? Do we not dash on unceasingly? Backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an above and below? Do we not stray, as through infinite nothingness?” The death of God has ushered in the single greatest crisis in human history: Nihilism, the bleakest and most destructive of worldviews, which finds its most eloquent expression in the following lines spoken by Shakespeare’s Macbeth:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

What is Noble?

According to Nietzsche, the elevation of the human species necessitates the establishment and maintenance of an aristocratic society—“a society believing in a long scale of gradations of rank and differences of worth among human beings, and requiring slavery in some form or other.” Unlike most Westerners today, Nietzsche vehemently opposes the doctrine of egalitarianism. That all men are created equal, as the U.S. Declaration of Independence asserts, is not in Nietzsche’s eyes a “self-evident truth,” but rather a self-evident lie.

The aristocratic caste creates and embodies the system of values (“master morality”) that ennobles, enriches, and beautifies their civilization. Whereas in liberal democratic societies each individual is free to pursue his or her particular vision of the good life, for Nietzsche civilization exists solely in order to produce those rare and gifted creatures which are its crowning glory. The multitude of men possesses value only insofar as they are useful subordinates to the ruling class; their principal virtues are obedience and submission.

How do aristocratic societies come into being? In a word, through conquest: “Men with a still natural nature, barbarians in every terrible sense of the word, men of prey, still in possession of unbroken strength of will and desire for power, threw themselves upon weaker, more moral, more peaceful races…” For Nietzsche, life is will-to-power, which “is essentially appropriation, injury, conquest of the strange and weak, suppression, severity….and at the least, putting it mildest, exploitation.” All living things, from the unicellular organism to the human being and even whole societies, exhibit the will-to-power. (Suffice it to say that aristocratic individuals possess far more strength and vitality than the slavish multitudes.) Exploitation, which in Nietzsche’s time (no less than our own) is viewed disparagingly as belonging “to a depraved, or imperfect and primitive society,” is in fact identical with the “Will to Life.” This is an indisputable fact which many of us are only too eager to deny: “the truth is hard.”

Master and Slave Morality

Nietzsche recognizes two fundamentally distinct types of morality in the world, what he terms master morality and slave morality. The former has always originated in the noble or aristocratic caste, the latter among the slave or dependent class. The two value terms that are applied in master morality are “good” and “bad.” The aristocratic man—who according to Nietzsche finds historical embodiment in “the Roman, Arabic, German, and Japanese nobility,” as well as among the Homeric heroes and Scandinavian Vikings—“conceives the root idea ‘good’ spontaneously and straight away, that is to say, out of himself.” “He honors whatever he recognizes in himself: such morality is self-glorification.” But what precisely are the qualities that characterize the aristocratic soul, qualities that find concrete expression in the formulation “good”? “The noble man,” Nietzsche explains, “honors in himself the powerful one, him also who has power over himself…who takes pleasure in subjecting himself to severity and hardness, and has reverence for all that is severe and hard.” Thus self-mastery, above even the brute physical strength used to subjugate others, emerges as the defining characteristic of nobility. As Nietzsche asserts in the previous section (What is Noble?), the aristocrats’ “superiority did not consist first of all in their physical, but in their psychical power—they were more complete men…” The aristocratic caste, as the incarnate will-to-power, is fiercely proud of its superior strength and elevated stature. This “instinct for rank” impels the nobles to segregate themselves from the lower beings, those who possess “the opposite of this exalted, proud disposition,” the multitude of slaves and weaklings of all sorts, toward whom the nobles (who have duties only to their equals) may act in whatever manner they wish.

While master morality spontaneously conceives the idea “good” as the embodiment of the nobles’ defining qualities (self-mastery, pride, physical strength, ambition, etc.), the concept “bad” is more of an afterthought: it encompasses all that is devoid of “goodness” and thus rightly deserving of scorn: “the cowardly, the timid, the insignificant, those thinking of narrow utility…” as well as “the distrustful…the self-abasing, the dog-like kind of men who let themselves be abused, the mendicant flatterers, and above all the liars.” So it is that the antithesis “good” and “bad” in master morality “means practically the same as ‘noble’ and despicable.’”

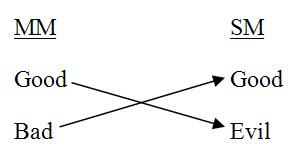

Whereas master morality is properly speaking active, originating out of the spontaneous assertion of the aristocratic caste’s essential qualities as “good,” slave morality, by contrast, is more aptly characterized as passive or reactive: “slave morality says ‘no’ from the very outset to what is ‘outside itself,’ ‘different from itself,’ and ‘not itself,’: and this ‘no’ is its creative deed.” Slave morality is born out of the resentment experienced by “the abused, the oppressed, the suffering, the unemancipated, the weary, and those uncertain of themselves,” who tremble in fear at the “power and dangerousness,” the “dreadfulness, subtlety, and strength” of the noble caste and thus who, “deprived as they are of the proper outlet of action, are forced to find their compensation in an imaginary revenge.” Instead of asserting their will by way of direct action and manly self-assertion (of which only the “well-born” are capable), the impotent multitudes must resort to contriving a system of values whereby they exact “an imaginary revenge” on their betters by consigning them to the illusory category of evil—“the original, the beginning, the essential act in the conception of a slave morality”—in contrast to which the slave caste, by a wild leap of self-delusion, elevates itself to the status of “good”: The “‘tame man,’ the wretched mediocre and unedifying creature, has learnt to consider himself a goal and a pinnacle, an inner meaning, an historic principle, a ‘higher man.’” The transition from master to slave morality therefore looks like this:

Slave morality, Nietzsche explains, is essentially the morality of utility. Those qualities “which serve to alleviate the existence of sufferers,” to make their lives less painful, less insecure, less contemptible, and therefore more tolerable, are enshrined in the morality of the lower class:

It is here that sympathy, the kind, helping hand, the warm heart, patience, diligence, humility, and friendliness attain to honor; for here these are the most useful qualities, and almost the only means of supporting the burden of existence.

As Nietzsche restates in Goodness and the Will to Power, “good” in the aristocratic sense (which Nietzsche fully endorses as the valuation that best corresponds to “the nature of the living being as a primary organic function”) is constituted by “all that enhances the feeling of power.” “Bad,” by contrast, is that which “proceeds from weakness.” True happiness, then, is the “feeling that power is increasing—that resistance has been overcome.” The happiness of the noble caste is thus inseparable from activity, as opposed to the sham happiness “of the weak and oppressed, with their festering venom and malignity,” for whom happiness “appears essentially as a narcotic, a deadening, a quietude, a peace, a ‘Sabbath,’ [i.e., a break from activity]…in short, a purely passive phenomenon.” The aristocrat’s inherent vigor and vitality reveal themselves in his “contempt for safety, body, life, and comfort, [his] awful joy and intense delight in all destruction, in all the ecstasies of victory and cruelty…” The diffident, slavish man, on the other hand—represented by modern egalitarians who “believe almost instinctively in ‘progress’ and the ‘future’”—desires nothing more than comfort and safety, which accounts for Nietzsche’s chilling observation that

The profound, icy mistrust which the German provokes, as soon as he arrives at power—even at the present time—is always still an aftermath of that inextinguishable horror with which for whole centuries Europe has regarded the wrath of the blonde Teuton beast…that lies at the core of all aristocratic races.

Jose Ortega y Gasset, writing in late 1920s Spain, remarks on what he deems the “most important fact in the public life of the West in modern times,” namely “the appearance of the masses in the seats of highest social power[1]”— or, more precisely, “the rebellion of the masses.”

He begins by pointing out what is obvious to all: the phenomenon of “crowding.” The cities are teeming with an abundance of people, as are the cafes and restaurants, theaters, opera houses, and beaches. “We see,” he observes, “the multitude as such in possession of the locales and appurtenances created by civilization.” This is a radically new development, for previously none of these establishments were full. What, then, accounts for the change?

The individuals who constitute the present mass already existed before, although not as “the masses”: in previous generations, “each group, even each individual, occupied a space, each his own space…in the fields, in a village, a town, or even in some quarter of a big city.” Now, however, they appear suddenly as a mass “in the places most in demand,” that is, “the places previously reserved for small groups, for select minorities.” Thus whereas in past ages the mass went unnoticed, now they “have installed themselves in the preferred places of society.”

Framing it in sociological terms, Ortega argues that society has always been “a dynamic unity” comprised of two elements: masses and minorities. Let us begin by discussing the former: “they are,” he remarks, “made up of persons not especially qualified.” The mass-man is the “average man,” or more exactly anyone who does not measure himself “by any particular criterion,” and who is thus content to be “‘just like everybody else.’” He is not in the least perturbed by his mediocre condition, but rather is “smugly at ease” with it.

The “select individual,” by contrast, is the one “who demands more from himself than do others, even when these demands are unattainable.” According to Ortega, whose opposition to democratic egalitarianism was greatly influenced by Nietzsche, humanity is composed of 1) “those who demand much of themselves and assign themselves great tasks and duties,” and 2) “those who demand nothing in particular of themselves, for whom living is to be at all times what they already are, without any effort at perfection—buoys floating on the waves.”

Ortega is at pains to emphasize that the division of society he sketches is not a division “into social classes, but into two kinds of men.” “Strictly speaking,” he clarifies, “there are ‘masses’ and minorities at all levels of society—within every social class.” Thus it is not unusual to find among the working class “outstandingly disciplined minds and souls,” although the inverse trend has become even more common: mass and popular vulgarity have insinuated themselves into the traditionally selective groups. “Even in intellectual life,” Ortega laments, “which by its very essence assumes and requires certain qualifications, we see the progressive triumph of pseudo-intellectuals…” Consider the following:

Then there are activities in society which by their very nature call for qualifications: activities and functions of the most diverse order which are special and cannot be carried out without special talent. Thus: artistic and aesthetic enterprises; the functioning of government; political judgment on public matters. Previously these special activities were in the hands of qualified minorities, or those alleged to be qualified. The masses did not try or aspire to intervene: they reckoned that if they did, they must acquire those special graces, and must cease being part of the mass. They knew their role well enough in a dynamic and functioning social order.

Thus, with the advent of the “crowd phenomenon,” the many rich, rarified, and complex dimensions of political and cultural life—areas which were once the exclusive preserve of select minorities—have been usurped by the mass-man. Ortega refers to this condition as “hyperdemocracy,” a kind of majority tyranny in which the mass imposes “its own desires and tastes by material pressure.” He notes in addition that “the average reader” no longer reads in order to learn anything, but rather “in order to pronounce judgment on whether the writer’s ideas coincide with the pedestrian and commonplace notions the reader already carries in his head.” (This, by the way, is an apt description of the complacent prisoners of Plato’s cave allegory, who violently resist any attempts by the philosopher to enlighten them.)

We are left, finally, with a coarsened society which takes everything noble and praiseworthy out of human beings, turning them into vulgar little herd animals. “The mass,” Ortega concludes, “crushes everything different, everything outstanding, excellent, individual, select, and choice.”

[1] This would encompass political, economic, moral and intellectual influence, as well as “all our collective habits, even our fashions in dress and modes of amusement.”

Chapter 9 Jean-Paul Sartre Chapter MaterialsChapter 9 Quiz

Chapter Files

Sartre: "Existentialism is a Humanism"

Chapter Video Lecture

Chapter 9 Video Lecture

What is Existentialism?In his 1945 lecture on existentialism and humanism, Jean-Paul Sartre asserts: “existentialism is nothing else but an attempt to draw all the conclusions from a coherent atheist position.” He begins his explication of existentialist philosophy by discussing one of its key concepts: that existence precedes essence.

Let us, he says, consider any man-made object, a book or paper cutter, for instance. Here is an object that began as a concept or idea in the mind of the artisan who designed and constructed it. The concept involves the manner by which the paper cutter is constructed and, more importantly, the specific purpose or use to which it is put (in this case, to cut paper). “Therefore,” Sartre concludes,

let us say that, for the paper-cutter, essence—that is, the ensemble of both the production routines and the properties which enable it to be both produced and defined—precedes existence…Therefore, we have here a technical view of the world whereby it can be said that production precedes existence.

In other words, in the “technical view of the world,” the “essence” of the artifact precedes the actual physical existence of the artifact, in the sense that the blueprint or concept of the paper-cutter already exists in the artisan’s mind before he ever commits to its actual production in his workshop.

When we conceive God as the Creator, Sartre continues, He is thought of as a kind of superhuman artisan: God creates the Earth and the human species according to a deliberate and specific plan or idea: “Thus, the concept of man in the mind of God is comparable to the concept of paper-cutter in the mind of the manufacturer, and, following certain techniques and a conception, God produces man, just as the artisan, following a definition and a technique, makes a paper-cutter.” The concept of mankind in the divine intelligence is what we refer to as “human nature”: it defines mankind in terms of what we are and how we are meant to live (as we see, for example, in the natural law teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas).

Atheistic existentialism, Sartre claims, is a more coherent doctrine. It states: “if God does not exist, there is at least one being in whom existence precedes essence, a being who exists before he can be defined by any concept, and this being is man…” That is, man first of all exists, “turns up, appears on the scene, and, only afterwards, defines himself.” Because there is no God who conceives the concept “man” and then creates mankind according to that concept, there is no such thing as human nature. There is, in other words, no particular reason “why” we as a species are here. We are indeterminate beings, without any fixed essence of nature, and hence entirely free to live our lives in whatever manner we choose. The first principle of existentialism is that “man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.” Sartre also refers to this principle as “subjectivity.” Let us explore it in greater detail.

Unlike inert or non-conscious objects like stones and tables, man has a kind of intrinsic dignity insofar as he is a being who “is at the start a plan which is aware of itself…” “Nothing exists prior to this plan; there is nothing in heaven; man will be what he will have planned to be.” The human being creates his own essence or nature through his freely chosen acts, there being no pre-determined human nature with which he is stamped at conception and to which he must conform his actions. Thus if existence precedes essence, then “man is responsible for what he is.” And to be responsible for our own individuality necessarily entails being “responsible for all men,” for “in creating the man that we want to be… [we] at the same time create an image of man as we think he ought to be.” In other words, when we make a fundamental choice in life, we do so according to a set of personally chosen values which projects a certain image of ourselves as we choose to be, and by extension we are projecting an ideal image of man as we think he ought to be. For example,

if I want to marry, to have children; even if this marriage depends solely on my own circumstances or passion or wish, I am involving all humanity in monogamy and not merely myself. Therefore, I am responsible for myself and for everyone else. I am creating a certain image of man of my own choosing. In choosing myself, I choose man.

Anguish, Forlornness, Despair

By anguish Sartre means that “the man who involves himself and who realizes that he is not only the person he chooses to be, but also a law-maker who is, at the same time, choosing all mankind as well as himself, cannot escape the feeling of his total and deep responsibility.” Because man is free and at the same time responsible, he cannot escape the feeling of immense, deep, and total responsibility not only for his own actions but also for other men, since by choosing himself he assumes the responsibility of creating an image for all of humanity. His actions, therefore, are those of a lawmaker to whom “everything happens as if all mankind had its eyes fixed on him and were guiding itself by what he does.” Of course, many people attempt to flee from anxiety either by renouncing freedom (through relying on the advice of others instead of deciding on our own) or through self-deception (by believing that our actions have no affect on anyone else). If we are truly honest with ourselves, we recognize the disquieting and inescapable fact that we alone must choose what to do, without relying on any external source of guidance, however comforting that may be. Thus, in making a decision, one “cannot help having a certain anguish.”

“When we speak of forlornness,” writes Sartre, “we mean only that God does not exist and that we have to face all the consequences of this.” Sartre exposes the naivety of the casual or fashionable atheist who believes one can maintain a secular ethics while dispensing with the need for God altogether. The rationale of these superficial thinkers runs as follows:

God is a useless and costly hypothesis; we are discarding it, but meanwhile, in order for there to be an ethics, a society, a civilization, it is essential that certain values be taken seriously and that they be considered as having an a priori existence. It must be obligatory, a priori, to be honest, not to lie, not to beat your wife, to have children, etc., ...In other words…nothing will be changed if God does not exist. We shall find ourselves with the same norms of honesty, progress, and humanism, and we shall have made of God an outdated hypothesis which will peacefully die off by itself.

The thoughtless atheist wants to have the best of both worlds—that is, to jettison entirely the belief in God (with all the irksome restraints on our personal liberty such belief necessarily entails) while at the same time preserving the universal moral structure that makes civilization possible (but for which there is absolutely no place in a godless universe).

The existentialist, on the other hand, “thinks it very distressing that God does not exist,” for once God is out of the picture, “there can be no longer an a priori Good, since there is no infinite and perfect consciousness to think it.” If God does not exist, then “everything is permitted” because, to invoke St. Thomas Aquinas, there would be no natural and eternal law to define and punish evil and injustice. This key insight “is the very starting point of existentialism,” and as a result man is forlorn, consumed by a feeling of abandonment, “because neither within him nor without does he find anything to cling to.” We are utterly alone in the universe, without any natural (or supernatural) basis by which we can guide and assess our lives (This should remind you of Nietzsche’s “Mad Man and the Death of God”). Hence Sartre’s famous dictum that “man is condemned to be free.” Condemned, because he is not self-created, yet, in other respects free; “because, once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.”

In order to give us a better understanding of forlornness, Sartre refers to one of his students, who sought his advice on whether or not to join the French resistance, rather than stay with his mother. Sartre points out that no world-view or ideology (outside of existentialism) would be of any use to this boy because universal values are too vague and broad for the concrete and specific dilemmas each of us faces in life. For this reason Sartre says: “the only thing left for us is to trust our instincts,” by which he means that, “in the end, feeling is what counts. I ought to choose whichever pushes me in one direction.” His young student, embracing his freedom and responsibility, ought therefore to reach a decision in the following way:

If I feel that I love my mother enough to sacrifice everything else for her—my desire for vengeance, for action, for adventure—then I’ll stay with her. If, on the contrary, I feel that my love for my mother isn’t enough, I’ll leave.

But how do we determine the value of a “feeling”? For Sartre, it is precisely through action that we determine the value of our “instincts.” By choosing to stay with his mother, the boy’s feeling for her acquires value; but short of an “act which confirms and defines it,” such “feeling” is worthless. In other words, despite what we may think of ourselves in the safety of our imagination, we cannot possibly know how we would act in a given situation until we actually find ourselves in that situation, being forced by circumstances to make a choice one way or the other: “I may say that I like so-and-so well enough to sacrifice a certain amount of money for him, but I may say so only if I’ve done it.”

We arrive finally at Sartre’s analysis of despair, which results from our awareness that there are a multitude of factors in life that lie completely beyond our control. Thus when “we want something, we always have to reckon with probabilities.” “The moment,” Sartre continues, “the possibilities I am considering are not rigorously involved by my action, I ought to disengage myself from them, because no God, no scheme, can adapt the world and its possibilities to my will.” Thus no matter how well thought out your plan, no matter how determined your will, there will be contingencies you cannot influence. You may, for example, develop a detailed, long-term plan to become, say, an engineer. You may study hard and get into the best schools. But then one day, as you are driving home late one night after a graduate seminar, someone runs a red light and hits your car on the driver’s side, causing you severe and permanent brain damage, and thus in one stroke destroying your chances of fulfilling your plan to become an engineer. Or perhaps you meet the person you think is your “soul mate,” and you invest much effort and hope in building a life-long relationship with that person, only to find out that after ten years of marriage, your spouse has been cheating on you all along.

The lesson here is that it is impossible to conquer chance: hence Descartes’ famous dictum: “Conquer yourself rather than the world,” by which he means that you should accommodate your will to what is probable—knowing full well that circumstances outside of your control may hinder your plans—rather than expect the world (through belief in, for example, Divine Providence, or destiny) to adapt itself to your will, hopes, or desires. “Does this mean,” Sartre asks, “that I should abandon myself to quietism? No. First, I should involve myself; then, act on the old saying, ‘Nothing ventured, nothing gained.’” The existentialist says to himself: “I shall have no illusions and shall do what I can.” This is the very opposite of quietism, since it declares that (in a most fitting end to a chapter on atheistic existentialism)

Man is nothing else than his plan; he exists only to the extent that he fulfills himself; he is, therefore, nothing else than the ensemble of his acts, nothing else than his life.

Chapter 10 Quiz

Chapter Files

Chapter 10 Chapter Files

Chapter Video Lecture

Chapter 10 Video Lecture

The Frivolity of EvilWhen prisoners are released from prison, they often say that they have paid their debt to society.

This is absurd, of course: crime is not a matter of double-entry bookkeeping. You cannot

pay a debt by having caused even greater expense, nor can you pay in advance for a bank robbery

by offering to serve a prison sentence before you commit it. Perhaps, metaphorically

speaking, the slate is wiped clean once a prisoner is released from prison, but the debt is not

paid off.

It would be just as absurd for me to say, on my imminent retirement after 14 years of my

hospital and prison work, that I have paid my debt to society. I had the choice to do something

more pleasing if I had wished, and I was paid, if not munificently, at least adequately. I chose

the disagreeable neighborhood in which I practiced because, medically speaking, the poor are

more interesting, at least to me, than the rich: their pathology is more florid, their need for

attention greater. Their dilemmas, if cruder, seem to me more compelling, nearer to the fundamentals

of human existence. No doubt I also felt my services would be more valuable there: in

other words, that I had some kind of duty to perform. Perhaps for that reason, like the prisoner

on his release, I feel I have paid my debt to society. Certainly, the work has taken a toll on me,

and it is time to do something else. Someone else can do battle with the metastasizing social

pathology of Great Britain, while I lead a life aesthetically more pleasing to me.

121

From City Journal, Autumn 2004 by Theodore Dalrymple. Copyright © 2004 by The Manhattan Institute. Reprinted

by permission.