I want you to show that you understand the social dynamics that influence social trends. First, write about what you have perceived to be the trend in the last ten years or so, regarding the masses

Reading Resources/References

Sociology, Urban

International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Ed. William A. Darity, Jr.. Vol. 8. 2nd ed. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008. p15-17.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 15

Sociology, Urban

BIBLIOGRAPHY

As the cutting edge of change, cities are important for interpreting societies. Momentous changes in nineteenth-century cities led theorists to explore their components. The French word for place (bourg), and its residents (bourgeois), became central concepts for Karl Marx (1818–1883). Markets and commerce emerged in cities where “free air” ostensibly fostered innovation. Industrial capitalists thus raised capital and built factories near cities, hiring workers “free” from the feudal legal hierarchy. For Marx, workers were proletarians and a separate economic class, whose interests conflicted with the bourgeoisie. Class conflicts drove history. Max Weber’s (1864–1920) The City (1921) built on this legacy but added legitimacy, bureaucracy, the Protestant ethic, and political parties in transforming cities. Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) similarly reasoned historically, contrasting traditional villages with modern cities in his Division of Labor (1893), where multiple professional groups integrated their members by enforcing norms on them.

British and American work was more empirical. British and American churches and charitable groups that were concerned with the urban poor sponsored many early studies. When sociology entered universities around 1900, urban studies still focused on inequality and the poor. Robert Park (1864–1944) and many students at the University of Chicago thus published monographs on such topics as The Gold Coast and the Slum (1929), a sociological study of Chicago’s near north side by Harvey Warren Zorbaugh (1896–1965).

The 1940s and 1950s saw many efforts to join these European theories with the British and American empirical work. Floyd Hunter published Community Power Structure (1953), an Atlanta-based monograph that stressed the business dominance of cities, broadly following Marx. Robert Dahl’s Who Governs? (1961) was more Weberian, stressing multiple issue areas of power and influence (like mayoral elections versus schools), the indirect role of citizens via elections, and multiple types of resources (money, votes, media, coalitions) that shifted how basic economic categories influenced politics. These became the main ideas in power analyses across the social sciences.

Page 16 | Top of Article

Parisian theorists like Michel Foucault (1926–1984), Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002), and Henri Lefebvre (1901–1991) suggested that the language and symbols of upper-status persons dominated lower-status persons. Others, such as Jean Baudrillard, pushed even further to suggest that each person was so distinct that theories should be similarly individualized. He and others labeled their perspective postmodernism to contrast with mainstream science, which they suggested reasoned in a linear, external, overly rational manner. Urban geographers like David Harvey joined postmodernist themes with concepts of space to suggest a sea change in architecture, planning, and aesthetics, as well as in theorizing, although Harvey’s main analytical driver is global capitalism.

Saskia Sassen starts from global capitalism but stresses local differences in such “world cities” as New York, London, and Tokyo. Why these? Because the headquarters of global firms are there, with “producer services” that advise major firms, and market centers where sophisticated legal and financial transactions are spawned. Individual preferences enter, via global professionals and executives who like big-city living, but hire nannies and chauffeurs, attracting global migrants, which increases (short-term, within city) inequality. Some affluent persons create gated housing, especially in areas with high crime and kidnapping, like Latin America.

These past theories stress work and production. A new conceptualization adds consumption. Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) theorized that the flaneur drove the modern capitalist economy, by shopping. Typified by the top-hatted gentleman in impressionist paintings, the flaneur pursued his aesthetic sensitivities, refusing standardized products. Mall rats continue his quest.

Theories have grown more bottom-up than top-down, as have many cities, although this is controversial, as some capital and corporations are increasingly global. The father of bottom-up theory is Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859), whose Democracy in America (1835–1840) stressed community associations like churches. Linked to small and autonomous local governments, these associations gave (ideally) citizens the ability to participate meaningfully in decisions affecting them. Such experiences built networks of social relations and taught values of participation, democracy, and trust.

In the late twentieth century, Tocqueville and civic groups became widely debated as nations declined and cities competed for investors, residents, and tourists. With the cold war over, globalization encourages more cross-national travel, communication, investment, and trade. Local autonomy rose. But nations declined in their delivery of egalitarian welfare benefits, since ideal standards are increasingly international. “Human rights” is a new standard. Yet the world is too large to implement the most costly specifics, even if they remain political goals.

Over the twentieth century, many organizations shifted from the hierarchical and centralized to the smaller and more participatory. The community power literature from Hunter (1953) to Dahl (1961) and beyond suggests a decline in the “monolithic” city governance pattern that Hunter described in Atlanta. Dahl documented a more participatory, “pluralistic” decision-making process, where multiple participants combine and “pyramid” their “resources” to shift decisions in separate “issue areas.”

New social movements (NSMs) emerged in the 1970s, extending past individualism and egalitarianism and joining consumption and lifestyle to the classic production issues of unions and parties. These new civic groups pressed new agendas—ecology, feminism, peace, gay rights—that older political parties ignored. In Europe, the national state and parties were the hierarchical “establishment” opposed by NSMs. In the United States, local business and political elites were more often targeted. Other aesthetic and amenity concerns have also arisen— like suburban sprawl, sports stadiums, and parks; these divide people less into rich versus poor than did class and party politics.

Comparative studies emerged after the 1980s of thousands of cities around the world. They have documented the patterns discussed above, and generally show that citizens and leaders globally are more decentralized, egalitarian, and participatory. The New Political Culture (1998), edited by Terry Nichols Clark and Vincent Hoffmann-Martinot, charts these new forms of public decisions and active citizen-leader contacts via NSMs, consumption issues, focused groups, block clubs, cabletelevision coverage of local associations, and Internet groups. Global competition among cities and weaker nations makes it harder to preserve national welfare-state benefits. This encourages more income inequalities, individualism, and frustrated egalitarianism, which is registered in higher crime rates, divorce, and low trust. As strong national governments withdraw, regional and ethnic violence rises (e.g., in the former Soviet Union or diverse cities like Miami). Voter turnout for elections organized by the classical national parties (which still control local candidate selection in most of the world) thus declined, while new issue-specific community associations mushroomed in the late twentieth century. Urbanism has become global, carried by civic groups, diffused by the Internet, and operating in more subtle ways than past theories proposed.

SEE ALSO Anthropology, Urban ; Assimilation ; Bourdieu, Pierre ; Chicago School ; Cities ; Class Conflict ; Community Power Studies ; Dahl, Robert Alan ; Elite Theory ; Foucault, Michel ; Page 17 | Top of ArticleGeography ; Hunter, Floyd ; Marx, Karl ; Metropolis ; Pluralism ; Social Movements ; Street Culture ; Tocqueville, Alexis de ; Urban Renewal ; Urban Riots ; Urban Sprawl ; Urbanization ; Weber, Max

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clark, Terry Nichols, and Vincent Hoffmann-Martinot, eds. 1998. The New Political Culture. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Dahl, Robert A. [1961] 2005. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hunter, Floyd. 1953. Community Power Structure: A Study of Decision Makers. Durham: University of North Carolina Press.

Terry Nichols Clark

Source Citation (MLA 8th Edition)

"Sociology, Urban." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, edited by William A. Darity, Jr., 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2008, pp. 15-17. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3045302542/GVRL?u=umd_umuc&sid=GVRL&xid=dfc27136. Accessed 26 June 2019.

Gale Document Number: GALE|CX3045302542

View other articles linked to these index terms:

Page locators that refer to this article are not hyper-linked.

Decentralization,

urban sociology,

8: 16

Marx, Karl,

urban sociology,

8: 15

Social movements,

urban sociology,

8: 16

Sociology, urban,

8: 15-17

Tocqueville, Alexis de,

urban sociology,

8: 16

Urban sociology,

8: 15-17

Urban studies,

urban sociology,

8: 15-16

Urban Sociology

LEE J. HAGGERTY

Encyclopedia of Sociology. Vol. 5. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2001. p3191-3198.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2001 Macmillan Reference USA, COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 3191

URBAN SOCIOLOGY

Urban sociology studies human groups in a territorial frame of reference. In this field, social organization is the major focus of inquiry, with an emphasis on the interplay between social and spatial organization and the ways in which changes in spatial organization affect social and psychological well being. A wide variety of interests are tied together by a common curiosity about the changing dynamics, determinants, and consequences of urban society's most characteristic form of settlement: the city.

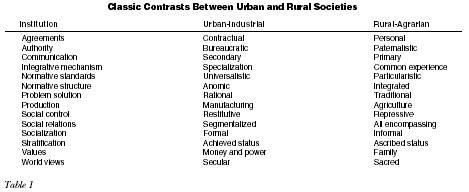

Scholars recognized early that urbanization is accompanied by dramatic structural, cognitive, and behavioral changes. Classic sociologists (Durkheim, Weber, Toinnes, Marx) delineated the differences in institutional forms that seemed to accompany the dual processes of urbanization and industrialization as rural-agrarian societies were transformed into urban-industrial societies (see Table 1).

Several key questions that guide contemporary research are derived from this tradition: How are human communities organized? What forces produce revolutionary transformations in human settlement patterns? What organizational forms accompany these transformations? What differences do urban living make, and why do those differences exist? What consequences does the increasing size of human concentrations have for human beings, their social worlds, and their environment?

Students of the urban scene have long been interested in the emergence of cities (Childe 1950), how cities grow and change (Weber 1899), and unique ways of life associated with city living (Wirth 1938). These classic treatments have historical value for understanding the nature of pre-twentieth-century cities, their determinants, and their human consequences, but comparative analysis of contemporary urbanization processes leads Berry (1981, p. xv) to conclude that "what is apparent is an accelerating change in the nature of change itself, speedily rendering not-yet-conventional wisdom inappropriate at best."

Urban sociologists use several different approaches to the notion of community to capture changes in how individual urbanites are tied together into meaningful social groups and how those groups are tied to other social groups in the broader territory they occupy. An interactional community is indicated by networks of routine, face-to-face primary interaction among the members of a group. This is most evident among close friends and in families, tribes, and closely knit locality groups. An ecological community is delimited by routine patterns of activity that its members engage in to meet the basic requirements of daily life. It corresponds with the territory over which the group ranges in performing necessary activities such as work, sleep, shopping, education,Page 3192 | Top of Article

Table 1

| Table 1 | ||

| Classic Contrasts Between Urban and Rural Societies | ||

| Institution | Urban-Industrial | Rural-Agrarian |

| Agreements | Contractual | Personal |

| Authority | Bureaucratic | Paternalistic |

| Communication | Secondary | Primary |

| Integrative mechanism | Specialization | Common experience |

| Normative standards | Universalistic | Particularistic |

| Normative structure | Anomic | Integrated |

| Problem solution | Rational | Traditional |

| Production | Manufacturing | Agriculture |

| Social control | Restitutive | Repressive |

| Social relations | Segmentalized | All encompassing |

| Socialization | Formal | Informal |

| Stratification | Achieved status | Ascribed status |

| Values | Money and power | Family |

| World views | Secular | Sacred |

and recreation. Compositional communities are clusters of people who share common social characteristics. People of similar race, social status, or family characteristics, for example, form a compositional community. A symbolic community is defined by a commonality of beliefs and attitudes among its members. Its members view themselves as belonging to the group and are committed to it.

Research on the general issue of how these forms of organization change as cities grow has spawned a voluminous literature. An ecological perspective and a sociocultural perspective guide two major research traditions. Ecological studies focus on the role of economic competition in shaping the urban environment. Ecological and compositional communities are analyzed in an attempt to describe and generalize about urban forms and the processes of urban growth (Hawley 1981).

Sociocultural studies emphasize the importance of cultural, psychological, and other social dimensions of urban life. These studies focus on the interactional and symbolic communities that characterize the urban setting (Wellman and Leighton 1979; Suttles 1972).

Early theoretical work suggested that the most evident consequence of the increasing size, density, and heterogeneity of human settlements was a breakdown of social ties, a decline in the family, alienation, an erosion of moral codes, and social disorganization (Wirth 1938). Later empirical research has clearly shown that in general, urbanites are integrated into meaningful social groups (Fischer 1984).

The sociocultural tradition suggests that cultural values derive from socialization into a variety of subcultures and are relatively undisturbed by changes in ecological processes. Different subcultures select, are forced into, or unwittingly drift into different areas that come to exhibit the characteristics of a particular subculture (Gans 1962). Fischer (1975) combines the ecological and subcultural perspectives by suggesting that size, density, and heterogeneity are important but that they produce integrated subcultures rather than fostering alienation and community disorganization. Size provides the critical masses necessary for viable unconventional subcultures to form. With increased variability in the subcultural mix in urban areas, subcultures become more intensified as they defend their ways of life against the broad array of others in the environment. The more subcultures, the more diffusion of cultural elements, and the greater the likelihood of new subcultures emerging, creating the ever-changing mosaic of unconventional subcultures that most distinguishes large places from small ones.

Empirical approaches to urban organization vary according to the unit of analysis and what is being observed. Patterns of activity (e.g., commuting, retail sales, crime) and characteristics of people (e.g., age, race, income, household composition) most commonly are derived from government reports for units of analysis as small as city blocks and as large as metropolitan areas. These types ofPage 3193 | Top of Articledata are used to develop general principles of organization and change in urban systems. General questions range from how certain activities and characteristics come to be organized in particular ways in space to why certain locales exhibit particular characteristics and activities. Territorial frameworks for the analysis of urban systems include neighborhoods, community areas, cities, urban areas, metropolitan regions, nations, and the world.

Observations of networks of interaction (e.g., visiting patterns, helping networks) and symbolic meanings of people (e.g., alienation, values, worldviews) are less systematically available because social surveys are more appropriate for obtaining this kind of information. Consequently, less is known about these dimensions of community than is desirable.

It is clear that territoriality has waned as an integrative force and that new forms of extralocal community have emerged. High mobility, an expanded scale of organization, and an increased range and volume of communication flow coalesce to alter the forms of social groups and their organization in space (Greer 1962). With modern communication and transportation technology, as exists in the United States today, space becomes less of an organizing principle and new forms of territorial organization emerge that reflect the power of large-scale corporate organization and the federal government in shaping urban social and spatial organization (Gottdiener 1985).

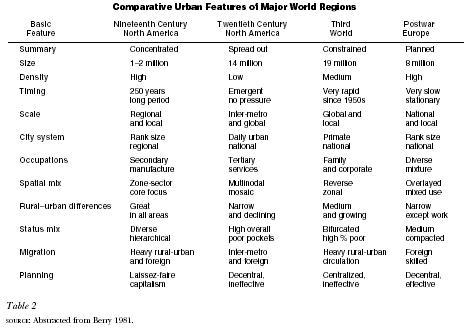

Hawley's (1950, 1981) ecological approach to the study of urban communities serves as the major paradigm in contemporary research. This approach views social organization as developing in response to basic problems of existence that all populations face in adapting to their environments. The urban community is conceptualized as the complex system of interdependence that develops as a population collectively adapts to an environment, using whatever technology is available. Population, environment, technology, and social organization interact to produce various forms of human communities at different times and in different places (Table 2). Population is conceptualized as an organized group of humans that function routinely as a unit; the environment is defined as everything that is external to the population, including other organized social groups. Technological advances allow people to expand and redefine the nature of the relevant environment and therefore influence the forms of community organization that populations develop (Duncan 1973).

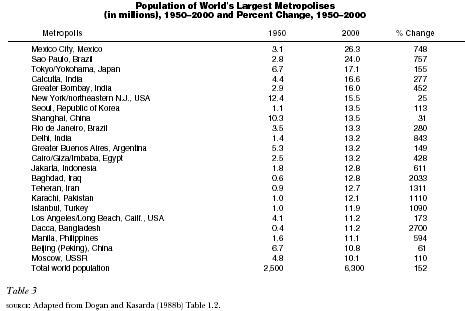

In the last half of the twentieth century, there were revolutionary transformations in the size and nature of human settlements and the nature of the interrelationships among them (Table 3). The global population "explosion" created by an unprecedented rapid decline in human mortality in less developed regions of the world after 1950 provided the additional people necessary for this population "implosion:" the rapid increase in the size and number of human agglomerations of unprecedented size. Urban sociology attempts to understand the determinants and consequences of this transformation.

The urbanization process involves an expansion in the entire system of interrelationships by which a population maintains itself in its habitat (Hawley 1981, p. 12). The most evident consequences of the process and the most common measures of it are an increase in the number of people at points of population concentration, an increase in the number of points at which population is concentrated, or both (Eldridge 1956). Theories of urbanization attempt to understand how human settlement patterns change as technology expands the scale of social systems.

Because technological regimes, population growth mechanisms, and environmental contingencies change over time and vary in different regions of the world, variations in the pattern of distribution of human settlements generally can be understood by attending to these related processes. In the literature on urbanization, an interest in the organizational forms of systems of cities is complemented by an interest in how growth is accommodated in cities through changes in density gradients, the location of socially meaningful population subgroups, and patterns of urban activities. Although the expansion of cities has been the historical focus in describing the urbanization process, revolutionary developments in transportation, communication, and information technology in the last fifty years expanded the scale of urban systems and directed attention toward the broader system of the form of organization in which cities emerge and grow.

Page 3194 | Top of Article

Table 2 SOURCE: Abstracted from Berry 1981.

| Table 2 | ||||

| Comparative Urban Features of Major World Regions | ||||

| Basic Feature | Nineteenth Century North America | Twentieth Century North America | Third World | Postwar Europe |

| SOURCE: Abstracted from Berry 1981. | ||||

| Summary | Concentrated | Spread out | Constrained | Planned |

| Size | 1–2 million | 14 million | 19 million | 8 million |

| Density | High | Low | Medium | High |

| Timing | 250 years long period | Emergent no pressure | Very rapid since 1950s | Very slow stationary |

| Scale | Regional and local | Inter-metro and global | Global and local | National and local |

| City system | Rank size regional | Daily urban national | Primate national | Rank size national |

| Occupations | Secondary manufacture | Tertiary services | Family and corporate | Diverse mixture |

| Spatial mix | Zone-sector core focus | Mutlinodal mosaic | Reverse zonal | Overlayed mixed use |

| Rural–urban differences | Great in all areas | Narrow and declining | Medium and growing | Narrow except work |

| Status mix | Diverse hierarchical | High overall poor pockets | Bifurcated high % poor | Medium compacted |

| Migration | Heavy rural-urban and foreign | Inter-metro and foreign | Heavy rural-urban circulation | Foreign skilled |

| Planning | Laissez-faire capitalism | Decentral, ineffective | Centralized, ineffective | Decentral, effective |

Much research on the urbanization process is descriptive in nature, with an emphasis on identifying and measuring patterns of change in demographic and social organization in a territorial frame of reference. Territorially circumscribed environments employed as units of analysis include administrative units (villages, cities, counties, states, nations), population concentrations (places, agglomerations, urbanized areas), and networks of interdependency (neighborhoods, metropolitan areas, daily urban systems, city systems, the earth).

The American urban system is suburbanizing and deconcentrating. One measure of suburbanization is the ratio of the rate of growth in the ring to that in the central city over a decade (Schnore 1959). While some Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) began suburbanizing in the late 1800s, the greatest rates for the majority of places occurred in the 1950s and 1960s. Widespread use of the automobile, inexpensive energy, the efficient production of materials for residential infrastructure, and federal housing policy allowed metropolitan growth to be absorbed by sprawl instead of by increased congestion at the center.

As the scale of territorial organization increased, so did the physical distances between black and white, rich and poor, young and old, and other meaningful population subgroups. The Index of Dissimilarity measures the degree of segregation between two groups by computing the percentage of one group that would have to reside on a different city block for it to have the same proportional distribution across urban space as the group to which it is being compared (Taeuber and Taeuber 1965). Although there has been some decline in indices of dissimilarity between black and white Americans since the 1960s, partly as a result of increasing black suburbanization, the index for the fifteen most segregated MSAs in 1990 remained at or above 80, meaning that 80 percent or more of the blacks would have had to live on different city blocks to have the same distribution in space as whites; thus, a very highPage 3195 | Top of Article

Table 3 SOURCE: Adapted from Dogan and Kasarda (1988b) Table 1.2.

| Table 3 | |||

| Population of World's Largest Metropolises (in millions), 1950–2000 and Percent Change, 1950–2000 | |||

| Metropolis | 1950 | 2000 | % Change |

| SOURCE: Adapted from Dogan and Kasarda (1988b) Table 1.2. | |||

| Mexico City, Mexico | 3.1 | 26.3 | 748 |

| Sao Paulo, Brazil | 2.8 | 24.0 | 757 |

| Tokyo/Yokohama, Japan | 6.7 | 17.1 | 155 |

| Calcutta, India | 4.4 | 16.6 | 277 |

| Greater Bombay, India | 2.9 | 16.0 | 452 |

| New York/northeastern N.J., USA | 12.4 | 15.5 | 25 |

| Seoul, Republic of Korea | 1.1 | 13.5 | 113 |

| Shanghai, China | 10.3 | 13.5 | 31 |

| Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 3.5 | 13.3 | 280 |

| Delhi, India | 1.4 | 13.2 | 843 |

| Greater Buenos Aires, Argentina | 5.3 | 13.2 | 149 |

| Cairo/Giza/Imbaba, Egypt | 2.5 | 13.2 | 428 |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | 1.8 | 12.8 | 611 |

| Baghdad, Iraq | 0.6 | 12.8 | 2033 |

| Teheran, Iran | 0.9 | 12.7 | 1311 |

| Karachi, Pakistan | 1.0 | 12.1 | 1110 |

| Istanbul, Turkey | 1.0 | 11.9 | 1090 |

| Los Angeles/Long Beach, Cailf., USA | 4.1 | 11.2 | 173 |

| Dacca, Bangladesh | 0.4 | 11.2 | 2700 |

| Manila, Philippines | 1.6 | 11.1 | 594 |

| Beijing (Peking), China | 6.7 | 10.8 | 61 |

| Moscow, USSR | 4.8 | 10.1 | 110 |

| Total world population | 2,500 | 6,300 | 152 |

degree of residential segregation remains. Although there is great social status diversity in central cities and increasing diversity in suburban rings, disadvantaged and minority populations are overrepresented in central cities, while the better educated and more affluent are overrepresented in suburban rings.

A related process—deconcentration—involves a shedding of urban activities at the center and is indicated by greater growth in employment and office space in the ring than in the central city. This process was under way by the mid-1970s and continued unabated through the 1980s. A surprising turn of events in the late 1970s was signaled by mounting evidence that nonmetropolitan counties were, for the first time since the Depression of the 1930s, growing more rapidly than were metropolitan counties (Lichter and Fuguitt 1982). This process has been referred to as "deurbanization" and "the nonmetropolitan turnaround." It is unclear whether this trend represents an enlargement of the scale of metropolitan organization to encompass more remote counties or whether new growth nodes are developing in nonmetropolitan areas.

The American urban system is undergoing major changes as a result of shifts from a manufacturing economy to a service economy, the aging of the population, and an expansion of organizational scale from regional and national to global decision making. Older industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest lost population as the locus of economic activity shifted from heavy manufacturing to information and residentiary services. Cities in Florida, Arizona, California, and the Northwest have received growing numbers of retirees seeking environmental, recreational, and medical amenities that are not tied to economic production. Investment decisions regarding the location of office complexes, the factories of the future, are made more on the basis of the availability of an educated labor pool, favorable tax treatment, and the availability of amenities than on the basis of the access to raw materials that underpinned the urbanization process through the middle of the twentieth century.

Page 3196 | Top of Article

The same shifts are reflected in the internal reorganization of American cities. The scale of local communities has expanded from the central business district–oriented city to the multinodal metropolis. Daily commuting patterns are shifting from radial trips between bedroom suburbs and workplaces in the central city to lateral trips among highly differentiated subareas throughout urban regions. Urban villages with affluent residences, high-end retail minimalls, and office complexes are emerging in nonmetropolitan counties beyond the reach of metropolitan political constraints, creating even greater segregation between the most and least affluent Americans

Deteriorating residential and warehousing districts adjacent to new downtown office complexes are being rehabilitated for residential use by childless professionals, or "gentry." The process of gentrification, or the invasion of lower-status deteriorating neighborhoods of absentee-owned rental housing by middle- to upper-status home or condominium owners, is driven by a desire for accessibility to nearby white-collar jobs and cultural amenities as well as by the relatively high costs of suburban housing, which have been pushed up by competing demand in these rapidly growing metropolitan areas. Although the number of people involved in gentrification is too small to have reversed the overall decline of central cities, the return of affluent middle-class residents has reduced segregation to some extent. Gentrification reclaims deteriorated neighborhoods, but it also results in the displacement of the poor, who have no place else to live at rents they can afford (Feagin and Parker 1990).

The extent to which dispersed population is involved in urban systems is quite variable. An estimated 90 percent of the American population now lives in a daily urban system (DUS). These units are constructed from counties that are allocated to economic centers on the basis of commuting patterns and economic interdependence. The residents of a DUS are closely tied together by efficient transportation and communication technology. Each DUS has a minimum population of 200,000 in its labor shed and constitutes "a multinode, multiconnective system [which] has replaced the core dominated metropolis as the basic urban unit" (Berry and Kasarda 1977, p. 304). Less than 4 percent of the American labor force is engaged in agricultural occupations. Even the residents of remote rural areas are mostly "urban" in their activities and outlook.

In contrast, many residents of uncontrolled developments on the fringes of emerging megacities in less developed countries are practically isolated from the urban center and live much as they have for generations. Over a third of the people in the largest cities in India were born elsewhere, and the maintenance of rural ways of life in those cities is common because of a lack of urban employment, the persistence of village kinship ties, and seasonal circulatory migration to rural areas. Although India has three of the ten largest cities in the world, it remains decidedly rural, with 75 percent of the population residing in agriculturally oriented villages (Nagpaul 1988).

The pace and direction of the urbanization process are closely tied to technological advances. As industrialization proceeded in western Europe and the United States over a 300-year period, an urban system emerged that reflected the interplay between the development of city-centered heavy industry and requirements for energy and raw materials from regional hinterlands. The form of city systems that emerged has been described as rank-size. Cities in that type of system form a hierarchy of places from large to small in which the number of places of a given size decreases proportionally to the size of the place. Larger places are fewer in number, are more widely spaced, and offer more specialized goods and services than do smaller places (Christaller 1933).

City systems that emerged in less industrialized nations are primate in character. In a primate system, the largest cities absorb far more than their share of societal population growth. Sharp breaks exist in the size hierarchy of places, with one or two very large, several medium-sized, and many very small places. Rapid declines in mortality beginning in the 1950s, coupled with traditionally high fertility, created unprecedented rates of population growth. Primate city systems developed with an orientation toward the exportation of raw materials to the industrialized world rather than manufacturing and the development of local markets. As economic development proceeds, it occurs primarily in the large primate cities, with very low rates of economic growth in rural areas. Consequently, nearly all the excess of births over deathsPage 3197 | Top of Articlein the nation is absorbed by the large cities, which are more integrated into the emerging global urban system (Dogan and Kasarda 1988a).

Megacities of over 10 million population are a very recent phenomenon, and their number is increasing rapidly. Their emergence can be understood only in the context of a globally interdependent system of relationships. The territorial bounds of the relevant environment to which population collectively adapts have expanded from the immediate hinterland to the entire world in only half a century.

Convergence theory suggests that cities throughout the would will come to exhibit organizational forms increasingly similar to one another, converging on the North American pattern, as technology becomes more accessible globally (Young and Young 1962). Divergence theory suggests that increasingly divergent forms of urban organization are likely to emerge as a result of differences in the timing and pace of the urbanization process, differences in the positions of cities in the global system, and the increasing effectiveness of deliberate planning of the urbanization process by centralized governments holding differing values and therefore pursuing a variety of goals for the future (Berry 1981).

The importance of understanding this process is suggested by Hawley (1981, p. 13): "Urbanization is a transformation of society, the effects of which penetrate every sphere of personal and collective life. It affects the status of the individual and opportunities for advancement, it alters the types of social units in which people group themselves, and it sorts people into new and shifting patterns of stratification. The distribution of power is altered, normal social processes are reconstituted, and the rules and norms by which behavior is guided are redesigned."

REFERENCES

Berry, Brian J. L. 1981. Comparative Urbanization: Divergent Paths in the Twentieth Century. New York: St. Martins.

——, and John D. Kasarda 1977 Contemporary Urban Ecology. New York: Macmillan.

Childe, V. Gordon 1950 "The Urban Revolution." Town Planning Review 21:4–7.

Christaller, W. 1933 Central Places in Southern Germany, transl. C. W. Baskin. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Dogan, Mattei, and John D. Kasarda 1988a The Metropolis Era: A World of Giant Cities, vol. 1. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

—— 1988b. "Introduction: How Giant Cities Will Multiply and Grow." In Mattei Dogan and John D. Kasarda, eds., The Metropolis Era: A World of Giant Cities, vol. 1. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Duncan, Otis Dudley 1973 "From Social System to Ecosystem." In Michael Micklin, ed., Population, Environment, and Social Organization: Current Issues in Human Ecology Hinsdale, Ill.: Dryden.

Eldridge, Hope Tisdale 1956 "The Process of Urbanization." In J. J. Spengler and O. D. Duncan, eds., Demographic Analysis. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Feagin, Joe R., and Robert Parker 1990 Building American Cities: The Urban Real Estate Game, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Fischer, Claude S. 1975 "Toward a Subcultural Theory of Urbanism." American Journal of Sociology80:1319–1341.

—— 1984 The Urban Experience. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Gans, Herbert J. 1962 "Urbanism and Suburbanism as Ways of life: A Reevaluation of Definitions." In A. M. Rose, ed., Human Behavior and Social Processes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Gottdiener, Mark 1985 The Social Production of Urban Space. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Greer, Scott 1962 The Emerging City. New York: Free Press.

Hawley, Amos H. 1950 Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure. New York: Ronald.

—— 1981 Urban Society: An Ecological Approach. New York: Wiley.

Kleniewski, Nancy 1997 Cities, Change, and Conflict: A Political Economy of Urban Life. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth.

Lichter, Daniel T., and Glenn V. Fuguitt 1982 "The Transition to Nonmetropolitan Population Deconcentration." Demography 19:211–221.

Nagpaul, Hans 1988 "India's Giant Cities." In Mattei Dogan and John D. Kasarda, eds., The Metropolis Era: A World of Giant Cities, vol. 1. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Palen, J. John 1997 The Urban World. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schnore, Leo F. 1959 "The Timing of Metropolitan Decentralization." Journal of the American Institute of Planners 25:200–206.

Page 3198 | Top of Article

Suttles, Gerald 1972 The Social Construction of Communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Taeuber, Karl E., and Alma F. Taeuber 1965 Negroes in Cities: Residential Segregation and Neighborhood Change. Chicago: Aldine.

Weber, Adna F. 1899 The Growth of Cities in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wellman, B., and B. Leighton 1979 "Networks, Neighborhoods and Communities: Approaches to the Study of the Community Question." Urban Affairs Quarterly 15:369–393.

Wirth, Louis 1938 "Urbanism as a Way of Life." American Journal of Sociology 44:1–24.

Young, Frank, and Ruth Young 1962 "The Sequence and Direction of Community Growth: A Cross-Cultural Generalization." Rural Sociology 27:374–386.

LEE J. HAGGERTY

Source Citation (MLA 8th Edition)

HAGGERTY, LEE J. "Urban Sociology." Encyclopedia of Sociology, 2nd ed., vol. 5, Macmillan Reference USA, 2001, pp. 3191-3198. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3404400404/GVRL?u=umd_umuc&sid=GVRL&xid=1fc6cbac. Accessed 26 June 2019.

Urbanization

International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Ed. William A. Darity, Jr.. Vol. 8. 2nd ed. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008. p545-548.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 545

Urbanization

THE CONTEMPORARY SPREAD OF URBANIZATION

DENSITY, DIVERSITY, AND URBANIZATION

URBANISM AND THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Urbanization—the transformation of social life from rural to urban settings—is the seminal process in defining the course of civilization. Urban life evolved approximately ten thousand years ago as a result of sophisticated agricultural innovations that led to a food supply of sufficient magnitude to support both the cultivators and a new class of urban residents. These agricultural innovations, mainly irrigation-based public works, required a more complex social order than that of an agrarian village. Urbanization at its base is thus distinguished from the settled agrarian life that preceded it in two important respects: it embodies a multifaceted social hierarchy and relies on sophisticated technologies to support the activities of daily living (Childe 1936). These uniquely urban characteristics consistently define both urbanization and civilization from the past to the present.

Just as civilization emerged from urbanization in the past, so too does the future course of civilization hinge on our ability to incorporate the reality of contemporary urbanization into our responses to twenty-first-century challenges that include climate change, the elimination of severe poverty, ecological balance, the conquest of communicable diseases, and other pressing social and environmental problems. This is the case because since 2007 more than half of the world’s population resides in urban settings—a historic first.

Page 546 | Top of Article

Urban life can be defined, following Louis Wirth (1938), as life in permanent dense settlements with socially diverse populations. According to Lewis Mumford (1937), the city plays a critical role in the creation and maintenance of culture and civilization. Finally, following Henri Pirenne (1925), the crucial role of trade and production should be stressed. Thus urbanization involves an ongoing threefold process: (1) urbanization geographically and spatially spreads the number and density of permanent settlements; (2) settlements become comprised of populations that are socially and ethnically differentiated; and (3) these urban populations thrive through the production and exchange of a diverse array of manufactured and cultural products.

THE CONTEMPORARY SPREAD OF URBANIZATION

Although city life extends back at least ten millennia, the shape and size of modern urban settlements have roots that extend back only about 250 years to the Industrial Revolution, which marked a significant transformation in the role of cities as loci of critical productive activity and not just as cultural and political centers for a surrounding agrarian countryside. The present characterization of the world as predominantly urban is the cumulative result of this urbanization-industrialization trend. Industrial urbanization emerged first in the countries of the West, then in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, and is now strongly evident in Asia and Africa (Garau et al. 2005).

According to United Nations projections, by 2030 the increase of 2.06 billion in net global population will occur in urban areas. Over 94 percent of that urban total (1.96 billion) will be in the world’s less-developed regions (UN Population Division 2004). This means that virtually all of the additional needs of the world’s future population will have to be addressed in the urban areas of the poorest countries.

UN-Habitat, the United Nations agency responsible for promoting sustainable urban development, estimates that roughly one-third of the current urban population of about three billion live in places that can be characterized as slums. The UN classification schema for slums is a fivefold measure: lack of access to safe drinking water, lack of access to sanitation, inadequate shelter, overcrowding, and lack of security of tenure. If a place of residence meets any one of these measures, it is classified as a slum. By the year 2030, if nothing is done, the proportion of the urban population living in slums will rise to 43 percent (1.7 billion in an urban population of 3.93 billion). All of these people will be living in the urban slums of countries in the developing world, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (UN-HABITAT and Global Urban Observatory 2003).

DENSITY, DIVERSITY, AND URBANIZATION

Urbanization is most powerfully observed through physical density (comparatively large numbers of people living in comparatively small areas). The ratio of population size to land area is the standard metric for evaluating density. It is a precise measurement that is not easily interpreted because neither the numerator (population size) nor the denominator (land area) is static. Political boundaries are only marginally helpful in defining the effective size of an urban settlement because at any moment changes in communications and transport technology alter the size of the relevant space over which urban residents live and work. Until the end of the eighteenth century, cities were spatially compact places with a radius of about one to two miles—the distance an individual could comfortably walk in carrying out daily activities. With the arrival of industrialization, effective urban size spread rapidly through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Contemporary urban or, more properly, metropolitansettlements easily encompass radii of 50 miles or more. This is a result of the continual improvement in rapid overland and even air travel modes and digital and wireless communications technology. The exact spatial configuration of any metropolitan settlement is a compromise between activities that must remain within walking distance and those for which residents are willing to travel (Schaeffer and Sclar 1980).

These spatially widening metropolises are not uniform in terms of their residential population densities. Hence density measurements alone tell us little about the quality of urban life. This quality can vary widely within the comparatively small confines of any metropolitan area. It is especially important to understand that high density per se is not an indicator of compromised living conditions. Metropolitan New York, which includes both the central city and the surrounding suburbs, has an average population density of over 5,300 people per square mile (ppm2), but the wealthiest part of the region, Manhattan Island, has a density that exceeds 66,000 ppm2. By way of comparison Nairobi, Kenya, has a city-wide density of over 1,400 ppm2, but its centrally located slum, Kibera, considered the largest in Africa, has an estimated population density of at least 100,000 ppm2. While Kibera’s density significantly exceeds Manhattan’s, the major determinant of the differences in quality of life relate to the quality of shelter and the ancillary urban services, such as water, sanitation, public safety, and most importantly transportation. Very poor urban residents must exchange life in high-density, poorly serviced places for the ability to walk to the places in the urban center where they earn a livelihood.

The major urban challenge of the twenty-first century concerns the ability of governments to effectively provide Page 547 | Top of Articleadequate shelter and to plan and deliver services for metropolitan-wide areas in developing countries. The difficulty in meeting the challenge is rooted in part in the fact that the historical political boundaries of the central city and suburban (i.e., satellite city) subunits of government typically derive from an earlier century, before contemporary transport and communications technology redefined effective spatial relationships. The urban economies of modern metropolises now run beyond the legal jurisdictions of the subunits of government responsible for infrastructure and public services. The insistence of international financial agencies and donors on governmental decentralization in developing countries has only served to exacerbate this problem because it has left these governmental subunits with the responsibility but without either the technical ability or revenue sources. The result is that necessary regional planning and infrastructure investment to address the challenges of urbanization are often stymied.

Urban population growth is largely migration driven. On one side there is the push of rural poverty and on the other the pull of urban opportunity. This migration-driven growth is further exacerbated by natural rates of urban population increase (birth rates that exceed death rates). Social life in urban settlements is thus more complex than its village counterpart. The transactions of daily living in villages are governed by a social economy where goods and services are exchanged on the basis of social roles and rules of reciprocity rooted in longstanding customs and religious observances. The transactions of urbanization that confront the new arrivals are, in whole or in part, defined by the impersonal exchange relationships typical of a market economy. This transition is never a simple one-for-one exchange.

Because urban populations are continually in flux and often simultaneously expanding, they are often characterized by a multiplicity of informal and formal social relationships and institutions in a similar state of flux. The variations among an informal social economy and a formal market economy in any city at any moment in time are highly reflective of the larger external forces, such as globalization and migration, that are continually redefining the roles of different cities in a world of complex trading and production relationships. In the slum of Kibera, many of the activities of daily life, including the provision of vital public services such as water, sanitation, and public safety, are governed by an informal local, but powerful, social economy (Lowenthal 1975). In contrast, life in the working-class neighborhoods of cities in developed countries is typically an amalgam of informal social institutions imbedded in formal mechanisms of municipal public-service delivery. For the wealthiest residents of these same cities, virtually all the services they consume are provided via the formal institutions of government or market exchanges.

URBANISM AND THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT

Many of the patterns of contemporary urban development are extensions of those set in place in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These patterns were based on three assumptions: (1) energy was relatively inexpensive; (2) safe drinking water was abundant; and (3) the environment could absorb all the waste products of urbanization. None of these assumptions is any longer valid. Consequently, urbanization in the twenty-first century will have to be reconceived in both social and environmental terms. The world cannot afford the political instability and social costs of massive pockets of urban slum dwellers, nor can it accommodate urban growth through a further spatial spread that relies on urban transport powered by carbon-based energy sources and the discharge of waste products into both the local and global atmosphere. A healthy and vibrant environment is now a scarce but vital good.

Environmental problems are principally generated by the disorderly sprawl of urban settlements into the surrounding countryside. In the developed world, metropolitan areas organized around private automobile travel among low-density suburbs and tied to a central business district generate high volumes of automobile travel in the absence of tight land-use regulation and good public transport. This development pattern has led to increased mobile source pollution within the metropolitan areas and significant greenhouse gas emissions that endanger the whole planet. Sprawl requires an ever-increasing spread of impermeable (i.e., paved) ground surfaces. This in turn leads to the runoff of polluted waters into the groundwater supplies. The paved surfaces absorb heat from the sun and create urban heat islands that require more energy consumption and the emission of pollution and greenhouse gases to cool homes and offices. In addition, there are inadequate landfills to collect all the refuse of these high-consumption urban centers.

In the developing world, the problems are similar but more acute in their direct manifestation. The high rates of population growth lead to a pattern in which urban settlement runs ahead of infrastructure improvement. This leads to the establishment of informal settlements (i.e., slums) characterized by an absolute lack of safe drinking water and sanitation. The lack of adequate public transport and public health protection systems leads to a congestion of private cars and informal transports in the center of cities, which exacerbates the air quality problems and greenhouse gas emissions. The social costs of the lack of these services fall disproportionately on the poorest residents of these burgeoning metropolitan areas. These costs take the form of excessive mortality and morbidity rates, low rates of labor productivity, and the reinforcement of an ongoing trap of urban poverty.

Page 548 | Top of Article

Climate change generated by greenhouse gas emissions adds yet another layer of special urgency to these pressing social problems. It is the very concentrated nature of cities—their population densities and their centrality in social functioning—that makes them and their residents so vulnerable to the hazards and stresses that climate change is inducing. Rising sea levels and warming water make serious climatic assaults on cities more frequent. Devastating storms and floods that hit once in a century now occur in far shorter cycles. The impacts are not equitably distributed. The poorest urban residents tend to live in the riskiest portions of the urban environments—flood plains, unstable slopes, river basins, and coastal areas.

Although the challenges of urbanization are formidable, the technical knowledge for their solutions exists. The question for the twenty-first century involves the ability of the international community, nations, and local governments to create institutions of urban planning and democratic governance that can effectively apply these solutions at a sufficiently broad scale that they can make a measurable difference.

SEE ALSO Cities

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Childe, V. Gordon. 1936. Man Makes Himself. London: Watts.

Garau, Pietro, Elliott Sclar, and Gabriella Carolini (lead authors). 2005. A Home in the City. UN Millennium Project: Task Force on Improving the Lives of Slum Dwellers. London and Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

Lowenthal, Martin. 1975. The Social Economy of the Urban Working Class. In The Social Economy of Cities, eds. Gary Gappert and Harold M. Rose, 447–469. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Mumford, Lewis. 1937. What Is a City? Architectural Record 82: 58–62.

Pirenne, Henri. [1925] 1948. Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade. Trans. Frank D. Halsey. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schaeffer, K. H., and Elliott Sclar. 1980. Access for All: Transportation and Urban Growth. New York: Columbia University Press.

UN-HABITAT and Global Urban Observatory. 2003. Guide to Monitoring Target 11: Improving the Lives of 100 Million Slum Dwellers. Nairobi, Kenya: Author.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division. 2004. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2003 Revision. New York: Author.

Wirth, Louis. 1938. Urbanism as a Way of Life. American Journal of Sociology 44: 1–24.

Elliott D. Sclar

Source Citation (MLA 8th Edition)

"Urbanization." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, edited by William A. Darity, Jr., 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2008, pp. 545-548. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3045302860/GVRL?u=umd_umuc&sid=GVRL&xid=ba471bc7. Accessed 26 June 2019.

Human Ecology and Environmental Analysis

LAKSHMI K. BHARADWAJ

Encyclopedia of Sociology. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2001. p1209-1233.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2001 Macmillan Reference USA, COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 1209

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS

With the growing awareness of the critical environmental problems facing the world today, ecology, the scientific study of the complex web of interdependent relationships in ecosystems, has moved to the center stage of academic and public discourse. The term ecology comes from the Greek word oikos("house") and, significantly, has the same Greek root as the word economics, from oikonomos("household manager"). Ernst Haeckel, the German biologist who coined the word ecology in 1868, viewed ecology as a body of knowledge concerning the economy of nature, highlighting its roots in economics and evolutionary theory. He defined ecology as the study of all those complex interrelations referred to by Darwin as the conditions of the struggle for existence.

Ecologists like to look at the environment as an ecosystem of interlocking relationships and exchanges that constitute the web of life. Populations of organisms occupying the same environment (habitat) are said to constitute a community. Together, the communities and their abiotic environments constitute an ecosystem. The various ecosystems taken together constitute the ecosphere, the largest ecological unit. Living organisms exist in the much narrower range of the biosphere, which extends a few hundred feet above the land or under the sea. On its fragile film of air, water, and soil, all life depends. For the sociologist, the most important ecological concepts are diversity and dominance, competition and cooperation, succession and adaptation, evolution and expansion, and carrying capacity and the balance of nature. Over the years, the human ecological, the neo-Malthusian, and the political economy approaches and their variants have come to characterize the field of human ecology.

CLASSICAL HUMAN ECOLOGY

The Chicago sociologists Louis Wirth, Robert Ezra Park, Ernest W. Burgess, and Roderick McKenzie are recognized as the founders of the human ecological approach in sociology. In the early decades of the twentieth century, American cities were passing through a period of great turbulence due to the effects of rapid industrialization and urbanization. The urban commercial world, with its fierce competition for territory and survival, appeared to mirror the very life-world studied by plant ecologists. In their search for the principles of order, human ecologists turned to the fundamental process of cooperative competition and its two dependent ecological principles of dominance and succession. For classical human ecologists, such as Park (1936), these processes determine the distribution of population and the location and limits of residential areas. City development is then understood in terms of succession—an orderly series of invasion—resistance—succession cycles in the course of which a biotic community moves from a relatively unstable (primary) to a more or less permanent (climax) stage. If resistance fails and the local population withdraws, the neighborhood eventually turns over and the local group is succeeded by the invading social, economic, or racial population. Each individual and every community thus finds its appropriate niche in the physical and living environment. In the hands of the classical human ecologists, human ecology became synonymous with the ecology of space. Park and Burgess identified the natural areas of land use, which come into existence without a preconceived design. Quite influential and popular for a while was the "Burgess hypothesis" regarding the spatial order of the city as a series of concentric zones emanating from the central business district. However, Hawley (1984) has pointed out that with urban characteristics now diffused throughout society, one in effect deals with a system of cities in which the urban hierarchy is cast in terms of functional rather than spatial relations.

Page 1210 | Top of Article

Since competition among humans is regulated by culture, Park (1936) made a distinction between the biotic and cultural levels of society: above the symbiotic society based upon competition stands the cultural society based upon communication and consensus. Park identified the problematic of human ecology as the investigation of the processes by which biotic balance and social equilibrium are maintained by the interaction of the three factors constituting what he termed the social complex(population, technological culture [artifacts], and nonmaterial culture [customs and beliefs]), to which he also added a fourth, the natural resources of the habitat. However, while human ecology is here defined as the study of how the interaction of these elements helps maintain or disrupts the biotic balance and the social equilibrium, human agency and the cultural level are left out of consideration by Park and other human ecologists.

NEOCLASSICAL HUMAN ECOLOGY

Essentially the same factors reappear as the four POET variables (population, organization, environment, and technology) in Otis Dudley Duncan's (1964) ecological complex, indicating its point of contact with the early human ecological approach. In any case, it was McKenzie who, by shifting attention from spatial relations to the analysis of sustenance relations, provided the thread of continuity between the classical and the neoclassical approaches. His student Amos Hawley, who has been the "exemplar" of neoclassical human ecology since the 1940s, defines human ecology as the attempt to deal holistically with the phenomenon of organization.

Hawley (1986) views the ecosystem as the adaptive mechanism that emerges out of the interaction of population, organization, and the environment. Organization is the adaptive form that enables a population to act as a unit. The process of system adaptation involves members in relations of interdependence in order to secure sustenance from the environment. Growth is the development of the system's inner potential to the maximum size and complexity afforded by the existing technology for transportation and communication. Evolution is the creation of greater potential for resumption of system development through the incorporation of new information that enhances the capacity for the movement of people, materials, and messages. In this manner, the system moves from simple to more complex forms.

Hawley (1984) has identified the following propositions, which affirm the interdependence of the demographic and structural factors, as constituting the core of the human ecological paradigm:

Adaptation to environment proceeds through the formation of a system of interdependences among the members of a population,

system development continues, ceteris paribus, to the maximum size and complexity afforded by the existing facilities for transportation and communication,

system development is resumed with the introduction of new information that increases the capacity for movement of materials, people, and messages and continues until that capacity is fully utilized. (p. 905)

The four ecological principles of interdependence, key function, differentiation, and dominance define the processes of system functioning and change. A system is viewed as made up of functioning parts that are related to one another. Adaptation to the environment involves the development of interdependence among members, which increases their collective capacity for action. Differentiation then allows human populations to restore the balance between population and environment that has been upset by competition or improvements in communication and transportation technologies. As adaptation proceeds through a differentiation of environmental relationships, one or a few functions come to mediate environmental inputs to all other functions. Since power follows function in Hawley's view, dominance attaches to those units that control the flow of sustenance into the ecosystem. The productivity of the key function, which controls the flow of sustenance, determines the extent of functional differentiation. As a result, the dominant units in the system are likely to be economic rather than political.

Since the environment is always in a state of flux, every social system is continuously subject to change. Change alters the life condition of all participants, an alteration to which they must adapt in order to remain in the system. One of the mostPage 1211 | Top of Articlesignificant nonrecurrent alterations is cumulative change, involving both endogenous and exogenous changes as complementary phases of a single process. While evolution implies a movement from simple to complex, proceeding through variation and natural selection, cumulative change refers to an increase in scale and complexity as a result of increases in population and territory. Whether the process leads to growth or evolution depends on the concurrent nature of the advances in scale and complexity.

Generalizing the process of cumulative change as a principle of expansion, Hawley (1979, 1986) applies this framework to account for growth phases that intervene between stages of development. When scale and complexity advance together, the normal conditions for growth or expansion arise from the colonization process itself. Expansion, driven by increases in population and in knowledge, involves the growth of a center of activity from which dominance is exercised. The evolution of the system takes place when its scale and complexity do not go hand in hand. Change is resumed as the system acquires new items of information, especially those that reduce the costs of movement away from its environment. Thus an imbalance between population and the carrying capacity of the environment may create external pressures for branching off into colonies and establishing niches in a new environment. Since efficiencies in transportation and communication determine the size of a population, the scope of territorial access, and the opportunity for participation in information flows, Hawley (1979) identifies the technology of movement as the most critical variable. In addition to governing accessibility and, therefore, the spread of settlements and the creation of interaction networks among them, it determines the changes in hierarchy and division of labor. In general, the above process can work on any scale and is limited only by the level of development of the technologies of communication and transportation.

Hawley (1986, pp. 104–106) points out how with the growth of a new regional and international division of labor, states now draw sustenance from a single biophysical environment and are converted to subsystems in a more inclusive world system by the expansive process. In this way, free trade and resocialization of cultures create a far more efficient and cost-effective global reach. The result is a global system thoroughly interlinked by transportation and communication networks. The key positions in this international network are occupied by the technologically advanced nations with their monopoly of information and rich resource bases. However, as larger portions of system territories are brought under their jurisdiction, the management of scale becomes highly problematic. In the absence of a supranational polity, a multipolar international pecking order is then subject to increasing instability, challenge, and change. With mounting costs of administration, the system again tends to return to scale, resulting in some degree of decentralization and local autonomy, but new information and improvements in the technologies of movement put the system back into gear and start the growth process all over again. In the modern period of "ecological transition," a large portion of the biophysical environment has progressively come under the control of the social system. Hawley, therefore, believes that the growth of social systems has now reached a point at which the evolutionary model has lost its usefulness in explaining cumulative change.

Hawley points out that while expansionism in the past relied on political domination, its modern variant aims at structural convergence along economic and cultural axes to obviate the need for direct rule by the center. The process of modernization and the activities of multinational corporations are a prime example of this type of system expansion, which undermines traditional modes of life and results in the loss of autonomy and sovereignty by individual states. Convergence of divergent patterns of urbanization is brought about by increased economic interdependence among nations and the development of compatible organizational forms and institutional arrangements. This approach, as Wilson (1984, p. 300) points out, is based on the assumption that convergence is mainly a result of market forces that allow countries to compete in the world on an equal basis. He cites evidence that shows how the subordinate status of non-Western nations has hindered their socioeconomic development, sharpened inequalities, increased rural-to-urban migration and rural–urban disparities, and led to the expansion of squatter settlements.

Human ecological theory accounts for the existence of an international hierarchy in terms of functional differences and the operation of itsPage 1212 | Top of Articleuniversal principles of ecosystem domination and expansion. Quite understandably, underdevelopment is defined by Hawley simply in terms of inferiority in this network. Since not all can enjoy equal position on scales of size, resources, and centrality with respect to information flows, Hawley believes that the resulting "inequality among polities might well be an unavoidable condition of an international division of labor, whether built on private or state capitalist principles" (1986, pp. 106, 119).

As the process moves toward a world system, all the limiting conditions of cumulative change are reasserted at a higher level. On the one hand, a single world order with only a small tolerance for errors harbors the seeds of totalitarianism (Giddens 1990). On the other, there is also the grave danger that a fatal error may destroy the whole system. Human ecologists, however, rely on further expansion as the sure remedy for the problems created by expansion. To restore ecological balance, they put their faith in the creation of value consensus, rational planning, trickle-downs, market mechanisms, technological fixes and breakthroughs, native "know-how," and sheer luck.

The real irony of this relentless global expansion elaborated by Hawley lies, however, in the coexistence of the extreme opulence and affluence of the few with the stark poverty and misery of the majority at home and abroad. The large metropolitan centers provide a very poor quality of life. The very scale of urban decay underscores the huge problems facing the city—congestion, polluted air, untreated sewage, high crime rates, dilapidated housing, domestic violence, and broken lives. One therefore needs to ask: What prospect does this scale and level of complexity hold for the future?

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND THE PROBLEMATICS OF "CHAOS"

Chaos theory is the latest attempt to unravel the hidden structure in apparently random systems and to handle chaos within and between systems. In this view, order and disorder (chaos) are seen as two dimensions of the same process: Order generates chaos and chaos generates order (Baker 1993, p. 123). At the heart of both lies a dynamic element, an "attractor," that creates the turbulence as well as re-creates the order. In the human–social realm, Baker has identified center–periphery, or centriphery, as the attractor. Baker, however, uses the concepts of center and periphery more broadly to cover not only their application in the dependency approach (which views the exploitation and impoverishment of the non-Western peripheral societies as basic to the rise of the dominant Western capitalist center), but also to carry the connotation of humans as "world-constructors." Centriphery is, then, the universal dynamic process that creates both order and disorder, as well as accounts for the pattern of human social evolution. The center has an entropic effect on the periphery, causing increasing randomness and denuding it of its resources. But as the entropic effects mount, they are fed back to the center. Beyond a certain point, the costs of controlling the periphery become prohibitive. Should the center fail to come up with new centering strategies, it may split off into subcenters or be absorbed by another more powerful center. Baker is thus led to conclude that "although the effect of feedback is unpredictable, the iteration of a pattern leads to turbulence. The mechanism for change and evolution are endemic to the centriphery process" (Baker 1993, p. 141).

Several things need to be noted about this approach. For one, since these eruptive episodes are random, "the emergence of repeated patterns . . . must be seen as random . . . not as mechanically predictable occurrences. Among other things, the precise character of the emergent pattern cannot be predicted, even though we would no longer be surprised to find a new thing emerging" (Francis 1993, p. 239). For another, Baker's centriphery theory is essentially Hawley's human ecological theory recast in the language of chaos theory, with the important difference that a specific reference is now made both to the role of agency as "world-constructors" involved in "categorizing, controlling, dominating, manipulating, absorbing, transforming, and so on," and to their devastating impact on the peripheralized "others," the victims of progress, who suffer maximum entropy, exploitation, impoverishment, death, and devastation. Even so, Baker's is the latest, though undoubtedly unintended, attempt to generalize and rationalize Western expansionism and its "chaotic (unpredictable) . . . devastating, and now increasingly well known, impact on native peoples" (BakerPage 1213 | Top of Article1993, p. 137). As such, the centriphery process, said to explain both order (stability) and disorder (change), is presented not only as evolutionary and irreversible, but also as natural and universal: "Thus, the Western world became a center through the peripheralization of the non-Western world. And within the Western world, particularly in North America, the city, which peripheralized the rural hinterland, became the megapolis whose peripheralizing effects were simultaneously wider and greater." (p. 136)]

Not only the recurrent iteration of this pattern but even its "unpredictable" outcomes (new strategies of control, splitting off into new subcenters, absorption into a larger center, etc.), are also prefigured in Hawley (1986). Its process is expansion, and its "attractor" is none other than the old master principle of sociology: domination or control (Gibbs 1989). While Friedmann and Wolff (1982) characterize world cities as the material manifestation of the control functions of transnational capital in its attempt to organize the world for the efficient extraction of surplus, Lechner (1985) leaves little doubt that Western "[materialism] and the emphasis on man's relation to nature are not simply analytical or philosophical devices, but are logically part of an effort to restore world-mastery" (p. 182).

"ECOLOGICAL DEMOGRAPHY"?

Since the study of organizational dynamics as well as the structure and dynamics of population are at the core of sociology, Namboodiri (1988) claims that rather than being peripheral to sociology, human ecology and demography constitute its core. As a result, he contends that the hybrid "ecological demography" promises a more systematic and comprehensive handling of a common core of sociological problems—such as the analysis of power relations, conflict processes, social stratification, societal evolution, and the like—than any other competing sociological paradigm. However, although human ecologists recognize the possibility of other pairwise interactions in addition to competition, and even highlight the points of convergence between the human ecological and the Marxist point of view (Hawley 1984), human ecology as such does not directly focus on conflict in a central way. In this connection, Namboodiri (1988) points out how the very expansionist imperative of human and social systems, identified as a central postulate by human ecologists, generates the possibility of conflict between the haves and the have-nots far more in a milieu of frustrated expectations, felt injustice, and a growing awareness of entitlements, which includes claims to their own resources by nations and to a higher standard of living by deprived populations. How these factors affect the development of and distribution of resources and the relationships among populations by sex, race, ethnicity, and other stratifiers should obviously be of concern to a socially responsible human ecology, one that moreover should be responsive to Borgatta's call for a "proactive sociology" (1989, 1996).

The general neglect of cultural factors and the role of norms and agency in human and organizational interaction has also been a cause for concern to many sociologists. While some latitude is provided for incorporating social norms in specific analyses (e.g., in the relationship between group membership and fertility behavior), their macro-orientation and focus on whole populations compels human ecologists and demographers to ignore the role of the subjective values and purposes of individual actors in ecological and demographic processes (Namboodiri 1988, pp. 625–627).

THE HUMAN ECOLOGICAL APPROACH: AN EVALUATION

While the human ecological approach has strong theoretical underpinnings and proven heuristic value in describing Western expansionism and the colonizing process in supposedly objective terms, its central problem is one of ideology. Like structural functionalism, it is a theory of the status quo that supports existing institutions and arrangements by explaining them as the outcome of invariant principles: "Its concerns are the concerns of the dominant groups in society—it talks about maximizing efficiency but has nothing to say about increasing accountability, it talks of maintaining equilibrium through gradual change and readjustment and rules out even the possibility of fundamental restructuring" (Saunders 1986, pp. 80–81). Not surprisingly, human ecologists downplay the role of social class by subsuming it under the abstract concept of a "categoric unit." They also fail to analyze the role of the state and of the interlocking power of the political, military, andPage 1214 | Top of Articleeconomic establishment, which are centrally involved in the process of expansion and colonization of peoples and cultures. These omissions account for their total lack of concern for the fate of the "excluded others" and the "dark side of expansionism": colonial exploitation, war, genocide, poverty, pollution, environmental degradation, and ecological destruction. Hutchinson (1993) blames the human ecologists for neglecting or downplaying the role of socioeconomic practices and government policies in creating rental, economic resource, and other differentials. He claims that their analyses tend to be descriptive because they take for granted the existence of phenomena such as socioeconomic or racial and ethnic segregation rather than looking at them in terms of spatial processes that result from the competition between capital and labor.

ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIOLOGY AND THE NEW HUMAN ECOLOGY