After reading the reading resources, please refer to the passage on "Law and Order" themes in society and politics. In 3 - 4 paragraphs, please illustrate an understanding of the past manipulation of

Law and Order themes - past and present

After reading the reading resources, please refer to the passage on "Law and Order" themes in society and politics. In 3 - 4 paragraphs, please illustrate an understanding of the past manipulation of the Law and Order theme in politics, and how it may have affected the recent social and political climate or may still affect the forthcoming social and political climate in America.

Note: Please try not to be excessively partisan, as this is not a forum for political opinions.

Reading Resources and Link’s that can be used for reference

Law and Order

International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Ed. William A. Darity, Jr.. Vol. 4. 2nd ed. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008. p369-372.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 369

Law and Order1962 TO 1965: VIOLENT RESISTANCE TO CIVIL RIGHTS

1965 TO 1970: BLACK MILITANT GROUPS AND URBAN UNREST

LAW AND ORDER IN THE 1968 CAMPAIGN

1972 TO 2007: LAW-AND-ORDER THEMES RECYCLED

LAW AND ORDER AND VIGILANTISM IN AMERICAN LIFE AND FILM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The term law and order refers to a prominent theme of Richard Nixon’s (1913–1994) successful 1968 campaign for the American presidency. Law and order became a potent campaign symbol for Nixon, and related themes have sometimes surfaced in later Republican presidential campaigns—especially in 1972 and 1988. The term law and order is a political symbol capturing public anxieties about civil unrest, urban riots, black militant groups (which, some charged, fomented violence), and rising crimerates. Later events, such as the violence in the Boston area in response to court-ordered busing, widely publicized crime sprees like the Son of Sam murders in New York City, and continued rising crime rates, stoked fears of societal breakdown during the 1970s and gave law-and-order appeals additional resonance. These developments, sometimes connected with subtle racial appeals, contributed to the erosion of the Democratic Party’s dominant position in American politics after 1968.

1962 TO 1965: VIOLENT RESISTANCE TO CIVIL RIGHTSAfter a period of relative domestic tranquility in the 1950s, the 1960s came as a rude shock to many Americans. Between 1961 and 1964, violent actions by southern whites bent on defending racial segregation became commonplace. Demonstrators at sit-ins and freedom riders, black and white, faced actual or threatened violence and mass arrests on fabricated charges. More violence erupted as federal officials attempted to carry out court-ordered desegregation. When black student James Meredith sought to enroll at (and integrate) the University of Mississippi, thousands of segregationists rioted, resulting in two deaths and forcing President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) to mobilize thousands of troops to restore order.

As the civil rights movement continued, it was met with more violence. Police in Birmingham, Alabama, deployed dogs and high-pressure water cannons against unarmed civil rights demonstrators in 1963. The murders of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) leader Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1963 and of three civil rights workers near Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1964 fed fears of mounting social unrest. A 1963 bombing of a Birmingham black church killed four little girls, and Alabama state troopers attacked unarmed voting-rights marchers with dogs and electric cattle prods in March 1965. These cumulative shocks to the national consciousness were amplified by the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas.

1965 TO 1970: BLACK MILITANT GROUPS AND URBAN UNRESTIn response to white violence against civil rights activists, some black leaders adopted increasingly belligerent rhetoric. The rise of black radicalism was personified in militants like Stokely Carmichael (1941–1998) and H. Rap Brown. As political scientists Donald Kinder and Lynn Sanders noted, the new rhetoric frightened many whites. There was “less talk of nonviolence and more of self-defense; less yearning for integration and more for solidarity and black nationalism; ‘We Shall Overcome’ was replaced by Black Power and ‘burn, baby, burn’” (1996, p. 103). The image of neatly-dressed blacks pummeled by vicious white violence faded, replaced by images of blacks rampaging through city streets, torching cars and buildings and looting stores. The initial trigger for the changing imagery was the August 1965 Watts riot in Los Angeles. As Kinder and Sanders described the Watts riot:

The violence raged unchecked for three days, and three days longer in sporadic eruptions. Blacks looted stores, set fires, burned cars, and shot at policemen and firemen. Before the violence was halted, 14,000 National Guard troops, 1,000 police officers and 700 sheriff’s deputies were pressed into service.… In the end, 1,000 buildings were damaged, burned, looted or completely destroyed; almost 4,000 people were arrested; more than 1,000 were injured seriously enough to require medical treatment; and 34 were dead, all but three of them black. (Kinder and Sanders 1996, p. 103)

Watts was only the beginning, as 1966, 1967, and 1968 each brought more unrest. In 1967, 250 serious uprisings occurred, including the Detroit riots, which killed forty-three people. More disturbances erupted in multiple cities after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968. As Kinder and Sanders observe:

For one long, hot summer after another, Americans watched what appeared to be the coming apart of their own country. On the front page of their morning newspapers and on their television screens in the evening appeared dramatic and frightening pictures of devastation and ruin: cities on fire, mobs of blacks looting stores and hurling rocks at police, tanks rumbling down the avenues of American cities.… Discussion of the “racePage 370 | Top of Articleproblem” in America … centered on the threat that inner-city blacks posed to social order and public safety. (Kinder and Sanders 1996, p. 103)

In 1968 the Kerner Commission released a report on the civil disturbances, warning that the United States was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” The urban violence and Kerner Commission report created an opening for Republicans to pounce on the law-and-order theme. Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon blasted the report for “blaming everybody for the riots except the perpetrators of violence,” promising “retaliation against the perpetrators” that would be “swift and sure.” As noted by journalists Thomas Edsall and Mary Edsall, Nixon’s running mate, hard-line Maryland governor Spiro Agnew (1918–1996), summoned black leaders in Baltimore to a stormy meeting where he accused them of cowardice for refusing to renounce black militant leaders like Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. Speaking of the violence in Baltimore after the King assassination, Agnew charged: “The looting and rioting which has engulfed our city during the past several days did not occur by chance. It is no mere coincidence that a national disciple of violence, Mr. Stokely Carmichael, was observed meeting with local black power advocates and known criminals in Baltimore three days before the riots began” (quoted in Edsall and Edsall 1991, p. 85).

The 1968 Democratic national convention met in Chicago following the June 1968 assassination of Democratic presidential candidate Robert Kennedy. Chaotic scenes of police beating demonstrators in Chicago’s streets and parks echoed the tumult within the convention hall, as party delegates splintered over the Vietnam War (1957–1975). By 1965 almost all American homes had televisions, bringing searing images of one dramatic (and sometimes horrifying) event after another into the public consciousness. The racial subtext to much of the unrest of the 1960s is unmistakable. As Kinder and Sanders note:

The riots opened up a huge racial rift. Fear and revulsion against the violence were widespread among both white and black Americans, but whites were much more likely to condemn those who participated in the riots and more eager for the police and National Guard to retaliate against them. Where blacks saw the riots as expressions of legitimate grievances, whites were inclined to explain them as eruptions of black hatred and senseless criminality.… To many white Americans, then, the civil disorders of the 1960s amounted to an appalling collective mugging. (Kinder and Sanders 1996, p. 104).

Liberals, then, faced the unenviable task of explaining why, after leading the fight to pass major civil rights laws, blacks appeared to be responding not with gratitude, but with annual explosions of violence, looting, and destruction.

As political analyst James Sundquist observes, the potency of law-and-order themes was evident as early as 1966, when Ronald Reagan (1911–2004) easily won the governorship of California after promising to “get tough” on welfare, crime, riots, and student unrest. In October 1966, the Republican Coordinating Committee charged that officials in the Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973) administration had “condoned and encouraged disregard for law and order.” In an August 29, 1967, press conference, House Republican leader Gerald R. Ford (1913–2006) proclaimed:

The war at home—the war against crime—is being lost. The Administration appears to be in full retreat. The homes and the streets of America are no longer safe for our people. This is a frightful situation.… The Republicans in Congress demand that the Administration take the action required to protect our people in their homes, on the streets, at their jobs.… There can be no further Administration excuse for indecision, delay or evasion. When a Rap Brown and a Stokely Carmichael are allowed to run loose, to threaten law-abiding Americans with injury and death, it’s time to slam the door on them and any like them—and slam it hard! (quoted in Sundquist 1983, p. 385)

As Sundquist notes, Ford’s statement illustrates that “by 1967, the Republicans were pulling out all the stops” (on the law and order issue). In 1968 “the issue was propelled by so many events that it hardly needed partisan exploitation” (1983, p. 385).

The cumulative effect of civil-rights violence, assassinations, urban rioting and unrest, the tumult at the 1968 Democratic convention, and the comparatively peaceful 1968 Republican convention in Miami was to create a climate unmistakably ripe for Republican law-and-order appeals. Many Americans were shell-shocked by the rising crime rates and domestic violence of the 1960s, amplified by the increasingly controversial Vietnam War, with antiwar demonstrators burning their draft cards and soldiers coming home, some in body bags, others maimed. In May 1970, Ohio National Guardsmen opened fire on antiwar protesters at Kent State University, killing four students and injuring nine. Many Americans sympathized more with the shooting guardsmen than with the dead students—a sentiment captured in Neil Young’s protest song “Ohio” (written immediately after the Kent State shootings and performed by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young). Page 371 | Top of ArticleThe song characterized conservative sentiment as celebrating the shootings: “should’ve been done long ago.”

LAW AND ORDER IN THE 1968 CAMPAIGNThe political context in 1968 was clearly ripe for a campaign centering on law and order. The Nixon campaign eagerly seized the opening. Nixon’s selection of Agnew as his running mate sent an unmistakable signal that if elected president he would “crack down” hard on rioters, draft protesters, and others perceived as contributing to or fomenting social and urban unrest. At the 1968 Republican convention, Nixon began his acceptance speech: “As we look at America, we see cities enveloped in smoke and flame. We hear sirens in the night.” Nixon’s speech continued by attacking Democratic-sponsored government programs for the unemployed, the poor, and cities as “reaping an ugly harvest of frustration, violence, and failure across the land.” Nixon’s campaign advertisements, too, reinforced the law-and-order theme. As Kinder and Sanders note:

Nixon’s television advertisements played upon Americans’ fear of crime. While voiceovers pointed to sharp increases in violent crime and blamed the Democrats, the television viewer witnessed scenes of riots and buildings in flames, montages of urban decay, a lonely policeman on the beat, a mugging, crowds taunting the police, faces of anxious and perplexed Americans, and a woman walking alone on a deserted city street as darkness fell. (Kinder and Sanders 1996, p. 226)

After Nixon’s election victory in 1968, Agnew, as vice president, demonstrated a slashing, attack-dog speaking style that further expanded on law-and-order themes. As noted by Sundquist, Agnew toured the country to support Republican candidates, attacking and denouncing “permissivists,” “avowed anarchists and communists,” “misfits,” the “garbage” of society, “thieves, traitors and perverts,” and “radical liberals” (1983, p. 387). This rhetoric is anything but subtle in positioning the Republican Party as representing the masses of “middle America” that abide by society’s rules, are horrified by social violence, and support harsh crackdowns against it—a group that later would be targeted by the appeal of the 1972 Nixon campaign to the “silent majority.” By implication, Agnew sought to position Democrats as representing less savory elements: antiwar radicals, draft-card burners, urban rioters, black militants, hippies, and practitioners of recreational drug use and sexual activity. Agnew’s language, then, expanded the law-and-order theme to imply that Democrats sympathized not only with those who encouraged and practiced crime and violence (i.e., black militants, urban rioters, and draft-card burners), but also with groups that encouraged a more general social permissiveness and breakdown of traditional moral values—that is, permissivists, radical liberals, and perverts. These themes foreshadowed Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign, which would successfully brand Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern as the candidate of “acid, amnesty, and abortion.”

1972 TO 2007: LAW-AND-ORDER THEMES RECYCLEDSince 1972, explicit law-and-order themes have become less central issues in most campaigns. However, a major exception was the 1988 presidential campaign, when George H. W. Bush portrayed Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis as “soft” on violent crime in a campaign that critics charged appealed to racial prejudices. The campaign featured the story of William “Willie” Horton, a black convict who, released from prison on a weekend furlough (a controversial program supported by Massachusetts governor Dukakis), escaped to Maryland, where he attacked a couple in their home. Republican strategists openly exploited the Horton case. One television advertisement, sponsored by an independent pro-Bush group, showed a sinister and unruly-looking Horton in a mug shot, while an announcer recounted Horton’s crimes, emphasized by the words kidnapping, raping, and stabbingappearing in large print on the screen. Republican strategist Lee Atwater (1951–1991) promised that “by the time this election is over, Willie Horton will be a household name.” Later, he said “the Horton case is one of those gut issues that are value issues, particularly in the South, and if we hammer at these over and over, we are going to win.” As Kinder and Sanders note, Atwater joked to a Republican gathering, “There is a story about Willie Horton, who, for all I know may end up being Dukakis’ running mate.… Maybe [Dukakis] will put this Willie Horton on the ticket when all is said and done” (1996, p. 255).

The 1988 campaign illustrates the political dangers for Democrats of not responding adequately to Republican efforts to brand them as “soft on crime.” Especially in the more conservative South, Democrats have responded by emphasizing crime-fighting credentials and support for the death penalty. Bill Clinton used this formula successfully in his 1992 and 1996 presidential campaigns, and in 2005 Democrat Timothy Kaine won the governorship of Virginia, a conservative state. Kaine successfully fended off Republican attacks on his personal opposition to the death penalty by promising to uphold death sentences handed down by Virginia juries. The law-and-order campaign theme most clearly applies to the 1968 presidential campaign. However, it has spawned similar campaign themes, usually pursued by Republicans Page 372 | Top of Articleeager to portray Democrats as “soft on crime,” with varying degrees of success.

LAW AND ORDER AND VIGILANTISM IN AMERICAN LIFE AND FILMParadoxically, the appeal of law-and-order themes has potentially contributed to citizen vigilantism at times. American history offers numerous examples of citizens “taking the law into their own hands.” White southerners’ lynchings of blacks are but one example of vigilante actions defending a social order that is anything but admirable. In 1898, for instance, the majority-black port city of Wilmington, North Carolina, was consumed by a race riot in which an unknown number of blacks (probably dozens) were murdered and hundreds more banished by an armed white mob bent on establishing white supremacy in local and statewide politics. Historian Timothy Tyson described the actions and motives of riot instigators as follows:

On Nov. 10, 1898, heavily armed columns of white men marched into the black neighborhoods of Wilmington. In the name of white supremacy, this well-ordered mob burned the offices of the local black newspaper, murdered perhaps dozens of black residents—the precise number isn’t known—and banished many successful black citizens and their so-called “white nigger” allies. A new social order was born in the blood and the flames, rooted in what News and Observer publisher Josephus Daniels, heralded as “permanent good government by the party of the White Man.” (Tyson 2006)

Tyson added that the riot “marked the embrace of virulent Jim Crow racism” nationwide. The Red Shirts, a paramilitary arm of the then-white-supremacist Democratic Party, had rampaged across North Carolina before the 1898 election, disrupting black church services and Republican meetings, and attacking blacks, who leaned Republican. These violent, vigilante actions were justified as necessary to preserve a cherished social order, white supremacy, by any means necessary. That their actions were neither lawful nor orderly probably never crossed the minds of either the Red Shirts or the white participants in the Wilmington riot.

Similarly, some anti-immigration activists along the U.S.-Mexican border have launched vigilante efforts to deter would-be undocumented immigrants from crossing from Mexico into the United States. Ranch Rescue is one such group, which styles itself as a defender of U.S. borders and private property rights against what it calls “criminal aliens” and “terrorists” out of a belief that law enforcementis unable or unwilling to act appropriately toward these ends. In 2005 Ranch Rescue founder Casey Nethercutt lost his southern Arizona ranch to satisfy a court judgment levied against him and other Ranch Rescue members for seizing and traumatizing two Mexican immigrants (Pollack 2005). The Wilmington riots and the Ranch Rescue case illustrate behaviors that are probably driven by the conviction that to restore law and order—or a cherished social goal—requires violating law and order at least temporarily.

The vigilantism inherent in the actions of the Wilmington riot instigators and Ranch Rescue members is also reflected in some American films. In movies like the Death Wish series starring Charles Bronson (1921–2003) and The Punisher (1989 and 2004), vigilantism is celebrated, with a curious and unmistakable implicit message: exacting revenge sometimes requires violating law and order—even abandoning the rule of law altogether. Law and order, then, has morphed from an often-potent political symbol from the 1960s through the 1980s to a notion that some action films celebrate violating—but whose impact in real-world politics is largely blunted.

Source Citation (MLA 8th Edition)

"Law and Order." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, edited by William A. Darity, Jr., 2nd ed., vol. 4, Macmillan Reference USA, 2008, pp. 369-372. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3045301310/GVRL?u=umd_umuc&sid=GVRL&xid=3e5f0073.

Ecology of Crime

RALPH B. TAYLOR

Encyclopedia of Crime and Justice. Ed. Joshua Dressler. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2002. p573-582.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2002 Macmillan Reference USA, COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 573

ECOLOGY OF CRIMEEcological variation in crime, delinquency, and fear of crime are examined in this entry. The discussion examines macro-level variations at the regional and city-levels, this considers community level variations.

City and regional and city differencesDocumented variations in local crime or arrest or offender rates date to the mid-nineteenth century. In France, for example, officials and researchers were particularly interested in seeing the effects of their new criminal laws. They looked at how many people were being arrested, imprisoned, flogged, or hung in different parts of the country. Researchers like Guerry and Quetelet found spatial variation in the rate at which people were being arrested for crime in different parts of the country (Brantingham and Brantingham).

The specifics of the patterns observed by these researchers still hold true when looking at spatial differences in crime rates today. In France, a few administrative subdivisions had very high rates, a few had very low rates, and many places were in between. Differences between regions were stable over time. In the United States, the South has been the highest violence region for quite some time K. Harris). Nevertheless, rates have varied widely in a range of locations. For example, the rate for people accused of crimes against persons for the period 1826–1830 ranged from 1 in 2,199 on the Mediterranean island of Corsica to 1 in 37,014 in Creuse in central France. In the United States reported violent crime rates at the state level in 1998 varied from 1,023 per 100,000 in Florida to 87 per 100,000 in North Dakota (Maguire and Pastore, eds. Table 3.118).

Patterns for violent and property crimes differ. Violent crimes were highest in rural areas of the U.S. South; in France during the 1990s property rates were highest in the industrialized, northern urban departments. During the same period in the United States, states with high rates of property crime were found not only in the South (Florida), but also in the far West (particularly in Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico) (Maguire and Pastore, eds., Table 3.116). In short, such patterns of local crime rates have proven durable in research over the past one hundred fifty years. Researchers in Britain during the mid-nineteenth century found comparable patterns at the county and local level (Glyde).

By the end of the nineteenth century, environmental criminologists had discovered the following fundamental features about spatial and temporal distributions of crime:

There is spatial variation in rates of reported crime, and that variation shows up no matter the level of detail. The variation is higher in some places than in others, regardless of whether one looks at the large-scale units, such as counties, or at areas within counties, like different towns or different cities, or different sections of a city (Brantingham et al.).

The spatial variation was persistent. Areas that were high on offense or offender or delinquency rates might stay high for a decade, or even generations, regardless of the physical changes made in or the population changes occurring in the locale.

Sometimes the spatial patterns are not what one might expect. High violence in rural areas represents one case in point. In 1980, seventy-one out of the one hundred highest homicide rate counties in the United States were rural counties (Kposowa et al.).

American criminologists have worked hard to explain the higher rates of violence in the South. Some have suggested that historically rooted and racially linked subcultural variations are linked to higher violence (e.g., Messner and Rosenfeld). Studies since the early 1990s, however, focus not on race but on a culture of honor originating in historical patterns of independent pig farming in the Deep South (Cohen and Nisbett). The famous Hatfield-McCoy feud, for example, started over a pig.

A more micro-scale view on subcultural differences has emerged since the mid-1970s. This view builds on Louis Wirth's theory of urbanism (1938), which sought to explain differences in how people acted in cities as compared to nonurban locations. City size, density, and heterogeneity of populations were expected to affect residents' social networks, mood, and community involvement.

The subcultural theory of urbanism does not address crime per se, but rather unconventional behavior that deviates from broader societal norms. Both criminal behavior and delinquency could presumably be considered unconventional behaviors. The theory contains four propositions:

Larger places develop more and more specialized subcultures than do less populous ones, and are therefore more culturally heterogeneous.

More populous places develop not only more distinct subcultures but also more intense subcultures than less populous places.

Between-group contact leads to mutual influence. Diffusion from more unusual to more typical groups is likelier the larger the atypical subculture and is therefore more likely in urban places.

The more urban the place, the higher the rates of unconventionality relative to the wider society, because a) larger places generate more diverse and more specialized subcultures; and b) critical mass and intergroup friction are likelier in larger places (Fischer, 1995, pp. 545–546).

Subcultural theory is an ecological theory because it is about impacts of places, usually cities. This model could explain differences in crime and delinquency linked to city size, as well as urban versus suburban versus rural differences in offending rates and delinquency rates.

Researchers have tried to explain the causes of city-to-city (or metro area-to-metro area) differences in crime rates, the net of regional differences, concentrating largely either on economic or racial differences. A range of theorists link crime and related outcomes to structural inequality. Models differ in the aspects of inequality addressed, forces giving rise to inequality, outcomes of interest, or the different processes whereby inequality leads to crime or related outcomes. All these models presume a conflict perspective.

From the mid-1850s to the 1950s large U.S. cities witnessed increases in industrial manufacturing, and increasing needs for disciplined, cooperative workers. These shifts resulted in increasing orderliness and routine in white and ethnic urban neighborhoods, the improvements in the latter neighborhoods taking place as immigrants became assimilated into the workforce. African Americans, in response to strong demand during World War II, and decreased segregation at least in some cities in the 1960s, also joined these occupational groups, with concomitant shifts in their neighborhoods. This was followed, from about 1965 onward, by deindustrialization and the economic deconcentration of manufacturing jobs from central city locations. Particularly hard hit were African American communities because those workers were the last group permitted entry to the industrial jobs, and the group whose ability to move to the new jobs was lowest.

Inequality theorists describe how in the last thirty years industrial restructuring and the shift to post-industrial economies have further accelerated processes leading to increased inequality across urban communities (e.g., Hagan and Peterson). These shifts have markedly affected urbanites' mood (Fisher, 1982) and their economic well-being. More specifically, since the 1960s poverty has increased rapidly in urban centers, with African Americans being heavily represented among the urban poor. These rapidly increasing concentrations of poverty have transformed low-income, urban communities. In many communities welfare-dependent, female-headed households have become the norm.

Concentration effects linked to high poverty levels may explain between-city differences inPage 575 | Top of Articlecrime rates as well as between-community differences. In extremely poor, predominantly African American urban communities, fundamental transformations take place in neighborhood life when poverty rates climb past 39 percent following class-selective out-migration by lower-middle to middle income African American households (Wilson). The broader commitment to the formal economy falters, as does commitment to mainstream values. Neighborhood institutions disappear, their customer base severely eroded. The joblessness itself triggers a range of social problems, including more disorderly street life, drug use, and crime. Concentration effects are economic in origin, and can operate in the context of a stratified labor market.

As neighborhoods become increasingly disorderly and socially isolated, outsiders avoid them and outside employers become more wary of hiring residents from these stigmatized locations; those remaining become increasingly socially isolated, making it even more difficult to network and get back into the mainstream economy. These represent concentration effects emerging from the extremely high density of unemployment, problems and disadvantage in these locations, not from the racial composition of the locales themselves. Recent ethnographies confirm such isolation in predominantly African American and some predominantly Hispanic communities (e.g., Bourgois).

As neighborhoods become increasingly disadvantaged one might expect crime to go up for any number of reasons. Four possible functional dynamics have been proposed at the city level, focusing on racial inequality, that could be driven by the concentration effects described by W. J. Wilson (Messner and Golden). One path expects more widespread "social disorganization/anomie" and thus more violence as racial inequality increases. Ties across communities will be poorer, and commitment to norms will weaken. Wilson would say that commitment to the formal economy and associated values would weaken. A second pathway ("relative deprivation/frustration-aggression") expects that increasing racial inequality makes the disadvantaged groups experience more relative deprivation; these sentiments increase offending rates among members of those disadvantaged groups. So violence rates just among the deprived groups should increase. A third pathway ("relative gratification/reduced aggression") looks at the reverse; as racial inequality increases those in the better-off contingent, that is, whites, should have lower offending rates because they are less deprived and more advantaged. Finally, an "opportunity effect" model suggests that as concentrations of extremely poor and often African American groups increases in cities, and chances for meaningful contacts between various racial groups decrease, interracial violence rates should drop. Blacks and whites simply have fewer chances of interacting with each other as racial inequality and isolation increase.

In addition to crime being an outcome influenced by inequality, if it increases as disadvantage increases, it can spur further concentration effects, including neighborhood depopulation, as selective out-migration increases.

An alternate view on racial inequality and crime emerges from D. Massey's work on segregation (Massey and Denton). His historical perspective suggests that virtually all ethnic groups except African Americans have moved out of segregated, inner-city, impoverished locations, and successfully assimilated. His work also highlights the constraints on African Americans migrating out of severely distressed neighborhoods. Crime's ability to cause neighborhood depopulation may be limited by poor African Americans continuing to move in, and limitations on the African Americans attempting to leave the distressed neighborhoods. For Massey, concentration effects emerge from long-standing racial attitudes and practices, not economic shifts.

Many researchers addressing city and metropolitan area changes work within a "new urban sociology" perspective, and the processes they highlight may help explain increasing crime rates from the late 1960s through the early 1990s in many large cities, and differences in crime rates between cities and suburban 1ocations (Gottdiener, The New Urban Sociology). These analysts point out:

The international political economy has significant effects on urban, suburban, and rural life.

A fundamental transformation of metropolitan structures took place in the last thirty to forty years as hierarchically arranged, central-city-dominated metro areas serving outlying suburbs and rural areas were transformed into highly differentiated, economically deconcentrated polynucleated metropolitan structures.

The transformation has produced highly uneven development, as capitalist growth always does, resulting in more radical spatial separations of different races and classes, reflected, for example, in increasing numbers of gated communities, hypersegregated "excluded ghettos," and "totalizing suburbs" where all residents' needs can be met in a small area (Marcuse); there is increasing economic, social, and political separation not only within the cities but also in the broader metropolitan areas.

As homogeneity in many city neighborhoods has decreased, so too have shared local ties. These shifts make for weaker local political cultures. In the language of systemic control theory, the increased heterogeneity and decreased local ties weaken informal local ties or parochial control, and the strength of public control as well. In the language of routine activity theory, fewer committed informal place managers may be present, or it may be harder to place managers to decide who belongs where.

The recent crime drop seen in many larger cities starting around 1990 or 1992, and continuing into the mid or even late 1990s has drawn considerable attention. Some have suggested the decline is due to better, "smarter" policing (e.g., Bratton), others have suggested it was due to declining gun use among juveniles, which may have linked to declining activity of crack cocaine-drug dealing activities, but the causes may vary from city to city (Fagan et al.).

Variation at the community and streetblock levelsWithin cities, there are safe neighborhoods and crime-ridden ones; even within crime-ridden neighborhoods, there are safe street-blocks—the two sides of the street bounded by the two cross streets—and dangerous ones. What do these patterns look like, and how are they to be explained? Most of the work in this area has examined neighborhood-to-neighborhood variations, although some have considered block-to-block differences (Taylor et al., 1984). Further, the bulk of the work has focused on social, economic, and cultural factors, although physical design features including landuse mix and design features linked to territorial functioning are relevant as well.

Many of the explanatory models used here have relied on a family of loosely associated perspectives on attributes of community including social problems, called human ecology (Hawley, 1981). These views seek to explain geographic variation in those attributes by concentrating on features of the immediate surround, whether that be streetblock, neighborhood, or city sector, and the connections between that surround and the broader geographic arena. Three fundamental premises of this family of perspectives are that place-to-place differences in racial and ethnic composition, socioeconomic status, and stability and family structure arise from broader dynamics at work in the larger spatial context; that those place-to-place differences in turn simultaneously instigate and reflect local, face-to-face and small group social dynamics; and that those local dynamics link to a wide range of crime-related outcomes such as delinquency rates, local crime rates, and fear of crime and related reactions to crime.

In 1925 Sir Cyril Burt, a British psychologist, published The Young Delinquent. He looked up the addresses of boys and girls reported as "industrial school cases" in London. Then he looked up where they lived, and made up a delinquency rate. Delinquency rates were highest in the areas right near the central business district (CBD), and declined as one moved outward. In addition, the areas of highest delinquency were also the areas of highest poverty. Burt concluded a relationship existed between social class and delinquency. Furthermore, even though his data were cross-sectional, he concluded that the relationship was causal. Later research of individuals continues to find connections between delinquency and social class (e.g., Hindelang et al.). But this does not mean the relationship holds at the individual level—to presume so is to commit the ecological fallacy.

Sociologists at the University of Chicago in the first half of this century investigated a wide array of urban social problems: delinquency, petty theft, dance halls, gambling, and immigrants' "culture shock," to name a few.

Two of these sociologists, Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay, investigated delinquency. They collected data not only from Chicago, but from other cities as well: Philadelphia, Richmond, Cleveland, Birmingham, Denver, and Seattle. Shaw and McKay went to juvenile courts and collected data about the number of juveniles who had been adjudicated delinquent. They were able to construct delinquency rates by posing the question, for every one thousand youths living in the community between the ages of nine and fifteen, how many had officially been adjudicated delinquent by the court? They also constructedPage 577 | Top of Articlerates using other spatial units, such as one square mile areas.

As had Burt, Shaw and McKay found higher delinquency rates closer to the center of the city, the central business district (CBD), than they did further away from the center city. Indeed, they observed that the further away a community was from the center city, the lower its delinquency rate. This pattern appeared not just in Chicago, but in each of the other cities they examined as well.

As is often time in cities, spatial differences link to social and economic differences. At the time Shaw and McKay were writing, populations were increasing in older cities. This "engine" of city growth led to economic differences across communities at varying distances from the city center. More specifically, because of city growth the CBD was expanding to keep up and "serve" the growth in the broader city. This, of course, had happened in the past as well. Given this historical and ongoing pattern, more desirable locations were always at the outer edge of the expanding city. Land use closer to the city center was often converted to nonresidential land uses such as large industries, stockyards (in the case of both Chicago and Baltimore), and large commercial concerns.

Not only were more central locations less desirable per se, they also were the sites of older housing. For the most part, older housing is also more worn-out housing. Given these less desirable locations, and the more dilapidated housing stock, housing in these areas tended to be cheaper. As prices shifted so too did the types of households living there. Poorer households were more likely to locate close to the city center, where housing was cheapest. Further away one would find housing occupied by low wage or blue-collar workers. More distant, one would find middle-income households. And finally, even further away, in an outer-city or perhaps in a more distant suburban location, one would find the highest income households.

These economic differences in house values and rents were exacerbated by the threat of invasion from the expanding CBD. People were constantly trying to "trade up" in their housing anyway, and move to a slightly better location. But since the CBD was growing at the time, residents from each inner zone would be "invading" the zones just beyond. In the innermost zone, the residential areas were in transition, converting from residential to commercial or industrial. This zone was thus labeled the transition zone. These impending changes led those residents who could get out to do so, those who owned properties there to stop maintaining them, and to maximize their return by converting these units to apartments. Left living in these sites were low-income individuals and households that could not afford housing anywhere else. The residential environment there was rather chaotic.

Linked to the economic differences were ethnic ones. It is generally true, with some exceptions (Massey and Denton), that the newest immigrants to a city make up predominantly lower-income households. This is still true today in large U.S. cities even though the immigrant groups in question are different now than they were then. Consequently, many members of these immigrant groups, when they first arrived in U.S. cities, were limited to central-city, low-income neighborhoods where housing was cheap.

In short, Shaw and McKay's basic model was an economic one; location-based dynamics were set in motion based on the socioeconomic status of the group in question. The physical dilapidation of an area matched the segregation of the population on an economic basis. Given the ethnic heterogeneity in these more dilapidated areas, and shorter tenures, supervision of juveniles was more lax, willingness to reprimand others' children was weaker, and delinquency was higher (Maccoby et al.).

The spatial pattern described above has shifted markedly in large cities in the post–World War II era:

Centralized city planning increased in the years following World War II. Urban renewal initiatives destroyed vast tracts of older, worn-out housing in older cities, and replaced them with large numbers of public-housing communities. Many of those displaced from older "slum" locations lost many friends in the process (Frey; Gans). The siting of these communities influenced the surrounding locations, sometimes destabilizing them.

Suburbanization increased as federal highway initiatives, especially under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, provided drastically improved road access to cities.

But for a number of reasons, the suburbanization of African American households proceeded more slowly than the suburbanization of white households (Massey et al.). Consequently, the larger, older cities themselves became increasingly African American in composition.

Passage of various fair housing laws, and related court cases in the 1950s and 1960s increased African Americans' access to housing. In cities where African Americans had historically been limited to specific sections of the city, pent-up demand resulted in rapid racial turnover in large numbers of neighborhoods.

Since about 1970 additional changes in cities have further modified the spatial pattern described above. Most importantly, large numbers of manufacturing jobs have left, migrating from central city locations first to southern locations, then abroad, making it increasingly difficult for those with relatively low education levels to secure employment. Receiving more media attention than has perhaps been warranted given the relatively small number of locations where it has occurred, central city neighborhoods in many urban locations have become partially gentrified. Lower-income households were partially replaced by middle or upper income households that moved in and improved the housing stock.

Given these shifts in cities since around 1950, one would not necessarily expect to see the same spatial pattern for delinquency rates, or crime rates, as were reported for the years prior to World War II. Nonetheless, one still might expect community characteristics to link to these outcomes in a similar way.

At the heart of the human ecological model of offense and delinquency rates is a constellation of processes: social disorganization. Its opposite is collective efficacy. A locale is socially disorganized if several things are true: residents do not get along with one another; residents do not belong to local organizations geared to bettering the community and thus cannot work together effectively to address common problems; residents hold different values about what is and what is not acceptable behavior on the street; and residents are unlikely to interfere when they see other youths or adults engaged in wrongdoing (Bursik, 1988).

By contrast, if collective efficacy is high in a locale, residents will work together on common, neighborhood-wide issues, will get along somewhat with one another, and will take steps to supervise activities of youth or teens taking place in the immediate locale. These outcomes link to organizational participation ("Do you belong to the local improvement association? Does your neighbor?"); informal social control ("If your neighbor saw a young teen spray painting the side of a building about midnight, would he do something about it?"); and local social ties based on propinquity ("How many of the people living on your block do you know by name? How many can you recognize when you see them? If you needed to borrow a tool, could you do so from a close neighbor?").

Researchers have suggested that three levels of resident-based control shape the level of social disorganization versus collective efficacy in a locale (e.g., Bursik and Grasmick). Private control refers to dynamics within families and between close friends. If Junioretta extorts school lunch money from two other neighbors while walking to school, and her parents find out about it, will they punish her appropriately? Parochial control refers to supervisory efforts made by neighbors and acquaintances. If a neighbor while gardening out back sees Junioretta walking down the alley threatening two other children and demanding their lunch funds, will she grab Junioretta by the ear and walk her home to her dad, or will she, the neighbor, just shrug her shoulders and go about planting her tomatoes? How much parochial control is exercised varies from block to block in a neighborhood. Public control refers to the neighborhood leadership's ability to garner resources from public and private agencies outside the neighborhood. Can the community association's leaders effectively lobby city hall for resources for neighborhood improvements and programs? For example, can they obtain funding for more school crossing guards on well-traveled routes leading to and from the local school? Can they work collaboratively with other neighborhood organizations on issues affecting their part of town?

High delinquency rates occurred in low income, ethnically heterogeneous, unstable locations because those ecological characteristics made social disorganization more likely. In lower income locales residents' concerns are more spatially circumscribed than in higher income locales (Taylor, 1988). In some low-income neighborhoods residents only feel safe within their own dwelling. As ethnic heterogeneity increases, it becomes increasingly difficult for residents to "decode" what other residents are doing. Increasing intercultural distance and perhaps language barriers make it harder to figure out what is going on. As instability increases, residents have less time to get to know their neighbors;Page 579 | Top of Articleit is harder to figure out who "belongs" on the block and who does not belong.

In other words, these structural attributes of the community either increase or decrease the chances that residents would exert some control over what took place in their community; these dynamics in turn would influence outcomes like delinquency, the local offending rate, and local victimization rates. Note that social disorganization mediates the impacts of community structure on the outcomes. It represents a crucial link connecting community fabric with the outcomes. It does appear, however, that community fabric; although it affects social disorganization, continues to exert an independent influence on outcomes like delinquency, victimization, and offending (Veysey and Messner). In short there are structural causes of these community-level differences beyond differences in social disorganization or collective efficacy.

Social disorganization is likely to be strongest, and collective efficacy weakest, when a community is in the midst of an invasion-succession cycle. In such a cycle, a neighborhood "turns over," with one type of resident replacing another. In the midst of such a cycle residents are unlikely to know their neighbors, and the local population will be quite heterogeneous in makeup.

Neighborhood residents are always changing: people move in and people move out. But if the two rates are roughly matched, and if the volume is relatively modest, and if those moving in are sociodemographically similar to those moving out, then the neighborhood is stable (Ahlbrandt and Cunningham). But if the volume of in-movers increases beyond a relatively low rate, and if the in-movers are sociodemographically dissimilar from the current residents, then over time the population in the locale would change. There would be an "invasion" of a new type of resident, and eventually that new type of resident would "succeed" the older type of resident.

Such cycles could be seen most clearly in the 1960s and 1970s in urban neighborhoods where racial succession took place, and white populations were replaced in relatively short order by African American households. Many expected that gentrified neighborhoods would follow the same cycle; but they have not. Even in some of the most reclaimed neighborhoods, higher-income, recent in-migrant owners mingle on the street with lower-income, longer-term, renters (Lee and Mergenhagen). The invasion-succession cycle can "stall" before completion. In these partially gentrified locations violent and property crime rates can be higher (Covington and Taylor).

Shaw and McKay's initial cross-sectional findings have been supported again and again (e.g., Baldwin, 1975). Studies routinely find the following.

Delinquency and offense and offender rates are higher closer to the city center than farther away, although there are exceptions, and although each of these outcomes maps differently onto spatial structure (Baldwin and Bottoms). Delinquency and offense and offender rates are higher in lower income, and/or less stable, and/or more predominantly African American communities (K. D. Harries, 1980), although differences have arisen regarding the relative contribution of each attribute, and the appropriate labels to apply to some of the dimensions of urban community structure examined (Sampson and Lauritsen). For example, some have argued that relative socioeconomic status in a locale—how poor the residents are, or how poor they are relative to those residents in adjoining neighborhoods—is the most important community correlate of high violent crime rates (Land et al.). Others argue that family disruption, and/or family structures that are less stable or provide less supervision of the locale are the most important (Sampson and Lauritsen). This debate is not about to end anytime soon.

In essence, the human ecological theory focuses on a community's position in the larger urban fabric, and how that position changes over time. It is its relative status, stability, and racial composition, and the changes in those features, that determine changes in offense, offender, and delinquency rates.

In a series of studies using Shaw and McKay's data on delinquency and census characteristics in Chicago, from the 1930s through the 1960s, more rapid community shifts connected with more rapid changes in the delinquency rate (e.g., Bursik, 1986). The ways in which neighborhoods changed varied across each decade, as did the relative contribution of different types of neighborhood changes to changes in delinquency. What was happening each decade was conditioned by the historical context. But despite these variations in each decade, community changes linked to delinquency changes in the expected ways. For example, increasing unemployment and increasing nonwhite racial composition were both tied to increasing delinquency rates.

Page 580 | Top of Article

Changes in neighborhood fabric are linked not only to changes in delinquency but also to changes in violence. A Baltimore study of changes in the 1970s found that neighborhoods shifting more dramatically on stability or status experienced more sizable shifts in violence as well (Taylor and Covington, 1988). Which particular feature of neighborhood fabric proved important depended on the type of violent crime examined.

Briefly put, one of the major extensions of social disorganization theory in the last two decades has been the application of the model to ecological changes over time. As the theory predicts, neighborhoods whose composition is changing more rapidly, relative to the other neighborhoods in the city, are more likely to experience increasing delinquency or crime problems. Even if the rapid change is in a "positive" direction, such as gentrification, increasing crime may accompany the shift (Covington and Taylor, 1989).

The features of neighborhood structure only predispose a neighborhood to have more or less social disorganization. Key studies, in Britain and in the United States, highlight the central importance of social disorganization versus collective efficacy processes (e.g., Sampson et al.). These processes mediate the impacts of structure on outcomes like offending and victimization, but structural impacts like differences in status and stability continue to exert some impacts on the outcomes separate from these processes (Versey and Messner).

Responses to crime like fear of crime are also ecologically patterned and social disorganization versus collective efficacy processes likewise appear to mediate the impacts of structure—status, race, stability—on the outcomes (Taylor, 1996). Similarly, rapid structural change affects these processes that in turn affect fear of crime (Taylor and Covington, 1993). Generally these studies show that although there are differences from study to study, neighborhood structure—especially status and stability—affects these outcomes in ways anticipated by the human ecological model, and that indicators of social disorganization versus social efficacy at least partially mediate the relationship.

In the last few years a related set of models concentrating on social and physical aspects of disorder in neighborhoods has emerged. The model terms these features incivilities. Physical incivilities include abandoned cars, weed-filled lots, vacant houses, and unkempt properties and yards. Social incivilities, although viewed by some as just misdemeanor crimes, include vandalism, rowdy groups of unsupervised teens, fighting neighbors, public drug use or drug sales, and the like. These models come in different forms, but the version drawing the most attention has suggested that incivilities can contribute independently, over time, to increasing neighborhood crime, neighborhood structural decline, and increased neighborhood fear (Skogan). Longitudinal analyses, however, show that incivilities do not change uniformly in locations (suggesting they are indicative of separate and somewhat unrelated problems) and the independent impacts of incivilities on neighborhood level outcomes are far weaker than the theory anticipates, although some predicted impacts do emerge (Taylor, 2001).

Policy impacts of work on the ecology of crime have been several. Since the early 1900s, city programs have targeted some of the areas where youths are at greatest risk of delinquency. More recently more refined geographic analyses of crime have concentrated enforcement efforts on crime "hot spots"—locations where police are called repeatedly to deal with crimes or disturbances. These targeted interventions can under some conditions have some deterrent or preventive impacts. Concern about incivilities has led to community policing initiatives targeted at these problems in the beliefs that reducing these problems will reduce crime. One recent longitudinal work suggests this enthusiasm may be misplaced (Taylor, 2001).

Interest in this work in the future will increase due in large part to increased availability of mapping software for locating crime and community data geographically, and allowing sophisticated spatial analyses (Weisburd and McEwen). Increasing availability of multilevel models also facilitate work in this area (Bryk and Raudenbush). In addition, after having fallen out of favor in the 1960s and 1970s, interest in the ecology of crime has increased in recent years and sociologists generally are discovering "neighborhood effects" in a range of topic areas. Nonetheless, one of the biggest factors holding work in this area back is the lack of routinely updated data that includes community characteristics, police calls for service and crime data, and social disorganization versus collective efficacy indicators for a number of neighborhoods in a number of cities. Hopefully future efforts of an inter-universityPage 581 | Top of Articleconsortium will work on such an effort.

RALPH B. TAYLOR

Source Citation (MLA 8th Edition)

TAYLOR, RALPH B. "Ecology of Crime." Encyclopedia of Crime and Justice, edited by Joshua Dressler, 2nd ed., vol. 2, Macmillan Reference USA, 2002, pp. 573-582. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3403000101/GVRL?u=umd_umuc&sid=GVRL&xid=caa681dd.

Societal Stratification

ARCHIBALD O. HALLER

Encyclopedia of Sociology. Vol. 4. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2001. p2864-2874.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2001 Macmillan Reference USA, COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning

Listen

Page 2864

SOCIETAL STRATIFICATIONSocietal stratification phenomena are the relatively enduring, hierarchically ordered relationships of power among the units of which society is composed. The smallest units are adults, gainfully employed men and/or women, nuclear families, or sometimes extended families or households. Such units are ordered from highest to lowest in terms of power: political power, acquisitional power, the power of prestige, and the power of informational standing. Everybody experiences stratification every day, although a person often notices it only in the sense that some people seem better or worse off than he or she is. Social thinkers, powerful people, and revolutionaries have always been especially concerned with stratification.

Page 2865 | Top of Article

Secure knowledge of the varying forms stratification structures may take is important because of the effects those structures have on many aspects of human experience, such as people's dreams of a better life, efforts to improve their situations, strivings for success, fear of failure, sympathy for the less fortunate, envy of others' good fortune, and even feelings about revolution.

A complete understanding of stratification requires several kinds of knowledge: first, what stratification structures consist of and how they vary; second, the individual and collective consequences of the different states of those structures; and third, the factors that make stratification structures change. This article reviews current thinking on the first of these elements.

HISTORY: CLASSICAL THEORYTwo different lines of thought inform modern theory on societal stratification. One is classical theory; concerned with political power and privilege, it employs historical evidence. The other is the empirical tradition, which deals with systematic data on stratification as it exists contemporarily. Present-day theory of the behavior of stratification phenomena can be traced to Karl Marx's challenge to the manufacturing and financial elites of his day. Behind his concerns and those of the working class for which he was Europe's chief spokesman for many years lay the great economic and political upheavals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The American and French revolutions and their aftermath culminated in legislation that made adults in many countries equal before the law. The related wave of emancipation of slaves and serfs in Europe and the Americas was also part of the intellectual environment of that day. Of more direct relevance to Marx's thinking was the rise of trade and the factory system, along with the growth of cities and the expansion of wealth. Marx saw urban populations dividing into two opposed classes. The capitalist class employed the workers; owned the workplaces, machines, and tools; and had ready access to large amounts of money for investment. The capitalists were opposed by their employees, the working class, who had nothing to offer but their time and energy. In Marx's view, these two classes differ in terms of power and privilege: power because capitalists give orders that workers must accept, privilege because capitalists take the surplus (whatever is left after paying the cost of production) for themselves and their investments, leaving for workers only the wages that the market for labor forces capitalists to pay. Actually, Marx was interested in how these classes came into being and the conflicting interests they expressed. He did not write specifically on societal stratification as it is understood today.

Later writers on stratification, attempting to elucidate or contradict Marx, spelled out more complex sets of stratification dimensions. Weber (1946, 1947) saw power as the general factor basic to the enduring inequalities referred to as stratification. Sometimes, like Marx, he used categories whose underlying dimensions had to be elucidated by others. Party, class, and status groups were his key concepts. When these concepts are dimensionalized (reconstituted as variables), "party" is seen to be legitimate political influence, "class" is seen to express a hierarchical order of economic status, and the variable underlying "status groups" is seen to be their hierarchical order according to the degree of social honor. In other writings, Weber saw education as a stratification variable. In still others, he often wrote about authority, or legitimate superordinate and subordinate relations of power. Weber said nothing about how people are distributed in these dimensions or, of course, about how and why such distributions vary.

More thoroughly and precisely than Marx or Weber, Sorokin (1927) crafted the bases of modern theories of societal stratification. He distinguished political stratification, economic stratification, and occupational stratification. The first is a dimension of political power, and the second a dimension of the power of income and wealth. He left the dimensionality of occupational status unclear, sometimes implying that it was authority, sometimes privilege, and sometimes intelligence. Much of Sorokin's theory of societal stratification remains intact. First, he noted that all societies are stratified to some degree, a position widely accepted today. Second, empirical researchers continue to refine and elucidate his concepts of occupational status and occupational mobility. Third, in this connection he asked why occupational stratification exists and concluded that organized communalPage 2866 | Top of Articlelife requires mechanisms and people to coordinate essential activities and that such coordination demands and rewards unusual ability. This view, now called the functionalist hypothesis, has been elaborated and disputed ever since. Fourth, he held that the degree of stratification varies from society to society and over time within given society: Stratification, he said, is in "ceaseless fluctuation." Sorokin specified several ways in which stratification structures may vary. The whole structure may rise or fall; the top may rise or fall, changing the degree of inequality; and the "profile," or the shape of the distribution, may vary. Similarly, the rate of individual upward or downward mobility may vary, and whole strata may rise or fall.

Sorokin thus presented a theory that specified (1) the general dimensions by which people are stratified within a society, (2) some ways in which the distributions of people on those dimensions may vary, and (3) why stratification exists. Also, he held such structures to be in ceaseless change.

The latest work in the classical tradition is that of Lenski (1966). His key dimensions are power, privilege, and prestige, in that order of importance. Beyond this, Lenski offers three main ideas. First, both functional theory and conflict theory, its opposite, are partly right. Society's needs demand coordination, implying the existence of strata based on power or authority and implying a degree of consent on the part of many of those whose activities are organized by others. However, conflict results from that control: Authority is often abused and, even when it is not, may be misunderstood. Second, inequalities are mostly those of power, with inequalities of privilege and prestige following mostly as consequences of them. Third, the degree of inequality, which is seen as a single phenomenon encompassing the rate of mobility and the distance between strata, increased with the growing comprehensiveness and complexity of society until the Industrial Revolution, after which it declined. According to Lenski, the main forces driving change in the degree of inequality are the size of the surplus of production and, undergirding this, the march of technological efficiency.

Lenski is clearly in the classical tradition in his concern with power and privilege and dependence on historical evidence. To some extent, he echoes Sorokin's concern with variations in stratification structures through an emphasis on the degree of inequality. He provides a compelling treatment of the issue of conflict versus societal necessity in regard to the existence of stratification. He uses historical evidence effectively and systematically to mark variations of inequality in agrarian and horticultural societies. However, Lenski's emphasis on two main, all-encompassing aspects of stratification—power (his key criterion variable) and inequality (used to denote the way in which power and its concomitants are apportioned)—forces too many separately varying stratification phenomena into too few molds. This problem becomes critical in industrial societies, where stratification dimensions vary independently of one another.

HISTORY: THE EMPIRICAL TRADITIONAs has been noted, this tradition of research on stratification is concerned with the here and now. This line of research has developed excellence in the measurement of the hierarchical positions of small demographic units within larger stratification structures. Although newer than the classical tradition, it has a long history. Several more or less independent status-measurement devices were formulated in the 1920s and 1930s. Most were concerned with either the prestige of the breadwinner's occupation or the quality of the home. They tended to share certain assumptions: that stratification consists of a single hierarchy, in the early days usually called social class; that one or two different scales are sufficient to test hypotheses concerning social class; that social class positions can be distinguished by direct observation and/or interviews with someone who knows the status holders; that routines can be devised that allow one to assign valid and reliable numerical scores to each status holder on each of the scales used to measure social class; that the unit to be scored is the household, which can be one person or several persons living in a single home; and that it is the whole unit that is to be scored, whether with data on the home or data on the head of the household. Many of these devices became obsolete because they had to be recalibrated for each new community or type of community to which they were applied. Those that survived—education and occupational status—did so because they providePage 2867 | Top of Articlecomparable scores across large populations, such as nations.

Of the two main survivors, educational attainment is easy to measure: the exact number of school years successfully completed from none through sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, and so on. Measurement of occupational status is another matter. Two systems are currently in use. Occupational prestige ratings assume that each person in a given occupation shares the prestige most people attribute to that occupation. Occupational prestige scales have been constructed for many countries (Treiman 1977). Occupational socioeconomic status indices (SEI) are scales that use education and income to measure the status level of each occupation and then attribute to an individual the resulting score of her or his occupation. In the United States, Treiman's prestige scale and the SEI provide highly correlated occupational scores (Featherman and Hauser 1978).

Regardless of the original intent of such scales—to measure positions in what once was believed to be the only stratification hierarchy—the two variables educational attainment and occupational status are also appropriate for use with the classical theorists' multidimensional view of stratification.

A SYNTHESISThe current synthesis was carried out by stratification theorists who were both sensitive to the concerns of classical theorists with power and privilege and steeped in the empirical tradition. Thus, they brought the classical theorists' concern with political power, economic power, and social honor (Weber), including Sorokin's occupational status and Lenski's prestige, together with the empiricists' concern with education and occupational status (overlapping Weber, Sorokin, and Lenski) and with quantitative measurement and analysis.

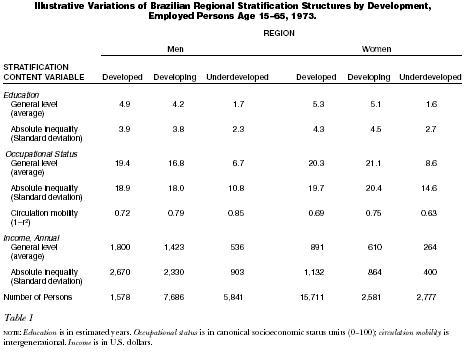

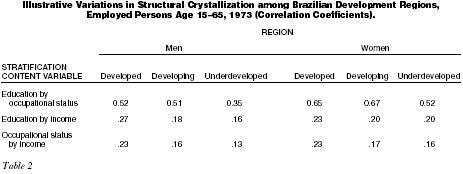

Svalastoga's Social Differentiation (1965) appears to be the first statement of the synthesis. Svalastoga indicates the centrality of four dimensions of status: political, economic, social (mostly occupational), and informational (mostly educational). He calls attention to structural variations through his "parameters": the degree of inequality, the correlation among dimensions, and the degree of permeability (intergenerational circulation mobility or movement up and down the hierarchies). Duncan (1968) both accepted and clarified Svalastoga's synthesis. His list of "scales of reward or status" provides a good outline of the large number of variables that should be measured to achieve a full-scale determination of people's levels on each status dimension. Also, he divides three of Svalastoga's four dimensions into two categories each. He, like Svalastoga, then lists three ways in which the structure of stratification variable may vary. The first is the degree of inequality. The second is called "rigidity of inequality" or "status crystallization," which is the same as Svalastoga's "correlation." The third is "rigidity of stratification," which is Svalastoga's "permeability" turned upside down.

Like Sorokin's and others' positions, Haller's (1970) statement of the synthesis assumes that stratification to one degree or another exists in all societies at all times. Revised slightly in this article, this form of the synthesis holds that there are two classes of dimensions of stratification. The first are "content"— or power—dimensions, after Weber: the capability of a given unit to elicit from others behavior promoted by the first unit, with such power having been routinized by coercion or consent. Agreeing conceptually but not always terminologically with the classical writers, this expression of the synthesis posits political power, economic power, and the power of prestige as universal dimensions of power. For civilized societies, it adds the power of years of formal education.

This position thus posits legitimatized political influence (including authority) as the dimension underlying Weber's "party," Sorokin's "political stratification," Lenski's "power," and Svalastoga's "political status." It posits Weber's "class," Sorokin's "economic stratification," Lenski's "privilege," and Svalastoga's economic status as referring to the same set of hierarchical phenomena: access to goods and services—the economic dimension of a stratification structure. From Weber, it takes the variable of social honor; from Sorokin and modern occupational status researchers, that of occupational stratification; from Svalastoga, that of social status; and from Lenski, that of prestige. From the empirical tradition, it takes the measurement of occupational power ("status"). All these elements are seen as referring to a third homogeneous set of hierarchical phenomena:Page 2868 | Top of Articlethe power of respect or deference attributed to a unit because of that unit's participation in a social category (such as an occupation) that has a specific level of evaluation by a society—the prestigedimension of societal stratification. As has been indicated, from Svalastoga and Duncan, with much support from the empiricists and also some from Weber, it takes informational power as a content dimension of a stratification structure, with education as its main indicator.

At the general level, each power dimension is of course presumed to be applicable in some form to all human societies as far back as human communal life can be traced. It is the exact expression of each dimension and the relationship among the dimension that vary across time and place. For entire contemporary societies, the main expressions of each dimension seem to be the following: for the political power dimension, political power, a variable researchers cannot yet measure despite its centrality in classical theory; for the economic dimension, income (occasionally wealth), a variable of concern to those in the empirical tradition; for the prestige dimension, occupational status in either of its two main forms of occupational prestige ratings (Treiman 1977) and occupational socioeconomic index scores (Featherman and Hauser 1978); and for the informational power dimension, educational attainment level in terms of years of formal schooling successfully completed. Thus, in recent years it has become apparent that for today's societies, the main variables of the empirical tradition have central places among the content dimensions of the classical tradition. Income, occupational status, and education are the theoretically defensible variables most readily available to measure three of the four classical content dimensions.

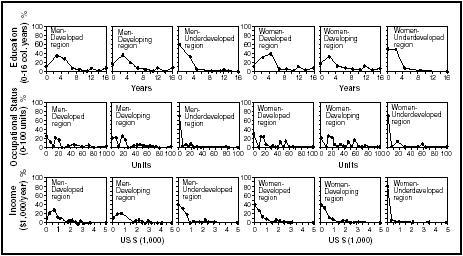

Like Sorokin's, Svalastoga's, and Duncan's, Haller's formulation of the synthesis specifies several structural dimensions, with each one held to be applicable to every appropriate measure of each content dimension. The three structural dimensions of Svalastoga and Duncan are included: degree of inequality, status crystallization, and degree of status inheritance. Two others from Sorokin are included, although they are modified to fit today's understanding. One is the general level or central tendency, and the other is a division of Sorokin's concept of profile into two concepts: mode structure and skewness. Although calculated from data on small units, each structural dimension applies to the society as a whole. Although logically they are partly dependent on one another, each one makes a unique contribution to an understanding of stratification. Each appears to be amenable to statistical description. Each is applicable to every indicator of the standing of every small unit (say, family) in the society. Valid measures of each content dimension taken at one point in time on a generalizable sample of the population of small units of that society would provide a complete description of the stratification structure of that society at that time. Successive measures would provide a complete description of the evolution of that society's stratification structure over time, thus providing a general idea of the variations in the degree of stratification in that society. Each applies to comparisons over time or among societies.

General Level. As Sorokin realized, the levels of structural dimensions may rise and fall as wholes. That is, the average economic, political, prestige, and informational standing of small units changes over time. These rises and falls may be seen in changes in the central tendency—say, the arithmetic mean or the median value—of the standing of small units. The rises and falls of the central tendency of any one of these dimensions do not necessarily follow the same pattern as those of another. Average economic, prestige, and informational power may increase, for example, while average political influence falls. This could happen in a society where a development-oriented dictatorship reduces citizen political participation while increasing levels of income, raising prestige by upgrading the occupational structure, and increasing access to education. Indeed, the economic, prestige, and educational levels of the populations of the more developed democracies have increased almost consistently since World War II, though this may not always be said for dictatorships. Also, raising the level of the occupational structure is exactly what some researchers mean by upward structural mobility, the case in which almost everyone is carried upward by changes in the economy that eliminate low-skill jobs while adding specialized jobs.