This week we have learned about incorporating play into the classroom and planning for disruptions and transitions in the classroom. These ideas are connected to the second pillar of becoming the Whol

3.1 Purposes of Play

Play fulfills a wide variety of purposes in the life of the child. The importance of play in early childhood is strongly emphasized in a recent report by the American Academy of Pediatrics (Milteer & Ginsburg, 2012):

Play is essential to the social, emotional, cognitive, and physical well-being of children beginning in early childhood. It is a natural tool for children to develop resiliency as they learn to cooperate, overcome challenges, and negotiate with others. Play also allows children to be creative. It provides time for parents to be fully engaged with their children, to bond with their children, and to see the world from the perspective of their child.... It is essential that parents, educators, and pediatricians recognize the importance of lifelong benefits that children gain from play. (p. 204)

Play Fosters Physical Development

Sensorimotor Skills

On a very simple level, play promotes the development of sensorimotor skills, or skills that require the coordination of movement with the senses, such as using eye-hand coordination to stack blocks (Frost et al., 2008; Jones & Reynolds, 2011; Morrison, 2004; Tokarz, 2008). Children spend hours perfecting such abilities and increasing the level of difficulty to make the task ever more challenging. Anyone who has lived with a 1-year-old will recall the tireless persistence with which the child pursues the acquisition of basic physical skills.

Fitness and Health

Strenuous, physical play is especially important today, when obesity among children and adults has reached an all-time high. An estimated 64% of all adults in the United States are seriously overweight or obese. Approximately 10% of all children age 2 to 5 years and 15% of older children are overweight (Association for Childhood Education International [ACEI], 2004). It is crucial that early childhood programs offer children the opportunity for active, gross-motor play every day, as habits and attitudes toward physical activity are formed early in life and continue into adulthood.

Outdoor Play Connects Children to Nature and Their Environment

Nature Feels Good and Inspires

Playing outdoors allows children to experience their natural environment with all their senses “open.” They can breathe fresh air and feel the invigoration of their hearts pounding as they charge up a hill. Children learn about the variety of creatures that may live in their area, explore the life cycle when they discover a cocoon or squashed ant, and experience fully with their senses how everything seems different after the rain. Where does the sun go when it is cloudy? Where does the wind come from? Questions about nature arise spontaneously through outdoor play and provoke children into thought and, if properly supported by the teacher, into deep investigations of the world. It is vital that we allow all children—urban, suburban, and rural—to discover the world outside and learn to appreciate the environment around them.

Children must have the opportunity for active, free, gross-motor play every day.

Children with Disabilities

Children with disabilities, too, can discover the world and appreciate the environment through outdoor play. We must accommodate our programs to meet the needs of children with disabilities by encouraging their outdoor activity. After all, discovering the beauty of nature is one of the lasting delights of childhood.

Play Fosters Intellectual Development

Symbolic Thought

Both Piaget and Vygotsky asserted that play is a major influence in cognitive growth (Curwood, 2007; Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 2003; Jones & Reynolds, 2011; Zigler et al., 2004). Piaget (1962) maintained that imaginative, pretend play is one of the purest forms of symbolic thought available to the young child.

Vygotsky (1978) also extolled the value of such fantasy play, arguing that during episodes of fantasy and pretend play, when children are free to experiment, attempt, and try out possibilities, they are most able to reach a little above or beyond their usual level of abilities, referred to as their zone of proximal development.

Acquisition of Information and Skills

Play also offers opportunities for the child to acquire information that lays the foundation for additional learning (Cavanaugh, 2008; Curwood, 2007; Elkind, 2007; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Jones & Reynolds, 2011; Montie, Xiang, & Schweinhart, 2007; Ramani & Siegler, 2007; Zigler et al., 2004). Play fosters children’s math, science, and literacy understanding and skills (Cavanaugh, 2008; Elkind, 2007; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Zigler et al., 2004). For example, through manipulating blocks the child learns the concept of equivalence (two small blocks equal one larger one). Through playing with water the child acquires knowledge of volume, which leads ultimately to developing the concept of reversibility (if you reverse an action that has changed something, it will resume its original state).

TEACHER TALK

“So many of the children spend their time in front of the TV when they are home. One of the benefits of my preschool is that they can run around outside to their hearts’ content.”

Acquisition of Information and Skills

Play also offers opportunities for the child to acquire information that lays the foundation for additional learning (Cavanaugh, 2008; Curwood, 2007; Elkind, 2007; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Jones & Reynolds, 2011; Montie, Xiang, & Schweinhart, 2007; Ramani & Siegler, 2007; Zigler et al., 2004). Play fosters children’s math, science, and literacy understanding and skills (Cavanaugh, 2008; Elkind, 2007; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Zigler et al., 2004). For example, through manipulating blocks the child learns the concept of equivalence (two small blocks equal one larger one). Through playing with water the child acquires knowledge of volume, which leads ultimately to developing the concept of reversibility (if you reverse an action that has changed something, it will resume its original state).

Imaginative, pretend play is one of the purest forms of symbolic thought available to the young child.

Language Development

Language has been found to be stimulated when children engage in play (Bergen, 2004; Cavanaugh, 2008; Isenberg & Quisenberry, 2002; Tokarz, 2008). Ramani and Siegler (2007) found that Head Start children’s math abilities improved after they played numerical board games, in part due to the use of “math-related language” that occurs naturally during the games and that is an important precursor to math learning (Cavanaugh, 2008). Riojas-Cortez (2001) found that children’s play in a bilingual classroom helped to extend the children’s use of language experimentation in both languages.

Play Enhances Social Development

One of the strongest benefits and satisfactions stemming from play is the way it enhances social development (Elkind, 2007; Ginsburg, 2007; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Jones & Reynolds, 2011). Playful social interchange begins practically from the moment of birth (Bergen, 2004; Copple & Bredekamp, 2009).

Pretend Play: Dramatic and Sociodramatic

As children grow into toddlerhood and beyond, an even stronger social component becomes evident as more imaginative pretend play develops. The early research of Smilansky and Shefatya (1990) demonstrated the positive effects of play on social development. Their methodological analysis has proven to be a helpful way of looking at children’s play and is widely used by early educators today. They speak of dramatic and sociodramatic play, differentiating between the two partially on the basis of the number of children involved in the activity. Dramatic play involves imitation and may be carried out alone, but the more advanced sociodramatic play entails verbal communication and interaction with two or more people, as well as imitative role playing, make-believe in regard to objects and actions and situations, and persistence in the play over a period of time.

Sociodramatic play in particular also helps children learn to put themselves in another’s place, thereby fostering the growth of empathy and consideration of others. It helps them define social roles: They learn by experiment what it is like to be the baby or the mother or the doctor. And it provides countless opportunities for acquiring social skills: how to enter a group and be accepted by its members, how to balance power and bargain with other children, and how to work out the social give-and-take that is the key to successful group interaction (Elkind, 2007; Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 2003; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Jones & Reynolds, 2011; Koralek, 2004).

Games with Rules

Piaget maintained that children in the concrete operational stage, approximately 7 to 11 years old, engage in playing games with rules. It is through this type of game playing that children learn what rules are, how to follow them, and what happens when rules are not followed. Larger issues, such as fairness and cheating, emerge and inform the child’s developing sense of social mores and personal moral behavior. In Piagetian theory, playing games in the early elementary years is crucial to the child’s social and moral development (Curwood, 2007; Elkind, 2007; Jones & Reynolds, 2011).

Play Contains Rich Emotional Values

Expression of Feelings

The emotional value of play has been better accepted and understood than the intellectual or social value because therapists have long employed play as a medium for the expression and relief of feelings (Elkind, 2007; Koralek, 2004; O’Connor, 2000). Children may be observed almost anyplace in the early childhood center expressing their feelings about doctors by administering shots with relish or their jealousy of a new baby by walloping a doll, but play is not necessarily limited to the expression of negative feelings. The same doll that only a moment previously was being punished may next be crooned to sleep in the rocking chair.

One of the strongest benefits and satisfactions stemming from play is the way it enhances social development.

Relieves Pressure

Omwake cites an additional emotional value of play (Moffitt & Omwake, n.d.). She points out that play offers “relief from the pressure to behave in unchildlike ways.” In our society so much is expected of children, and the emphasis on arranged learning can be so intense that play becomes indispensable as a balance to pressures to conform to adult standards.

Mastery

Finally, play offers children an opportunity to achieve mastery of their environment. In this way, play supports the child’s psychosocial development, as discussed in Chapter 1, promoting the development of autonomy, initiative, and industry. When children play, they are in command. They establish the conditions of the experience by using their imagination, and they exercise their powers of choice and decision as the play progresses.

Play Develops the Creative Aspect of the Child’s Personality

Imagination

Play, which arises from within, expresses the child’s personal, unique response to the environment. It is inherently a self-expressive activity that draws richly on the child’s powers of imagination (Elkind, 2007; Jones & Cooper, 2006; Jones & Reynolds, 2011; Isenberg & Quisenberry, 2002; Jalongo, 2003). As Nourot (1998) has said, “The joyful engagement of children in social pretend play creates a kind of ecstasy that characterizes the creative process throughout life” (p. 383).

Divergent Thinking

Play increases the child’s repertoire of responses. Divergent thinking is characterized by the ability to produce more than one answer, and it is evident that play provides opportunities to develop alternative ways of reacting to similar situations. For example, when the children pretend that space creatures have landed in the yard, some may respond by screaming and running, others by trying to “capture” them, and still others by engaging them in conversation and offering them a refreshing snack after their long journey.

Play Is Deeply Satisfying to Children

Probably the single most important purpose of play is that it makes children—and adults, too—happy. In a study of 122 preschoolers in eight various child care settings, 98% of the children cited play as their favorite activity. In addition, researchers found that the highest quality centers offered the most opportunities for free play and allowed extended time for children to play. Even in the centers that were rated “low quality” (where teachers were observed yelling at children and punishing them frequently), the children made play the central focus of their day, liked play best, and expressed happiness because they were able to play (Wiltz & Klein, 2001). Regardless of their situation, almost all children find happiness in play.

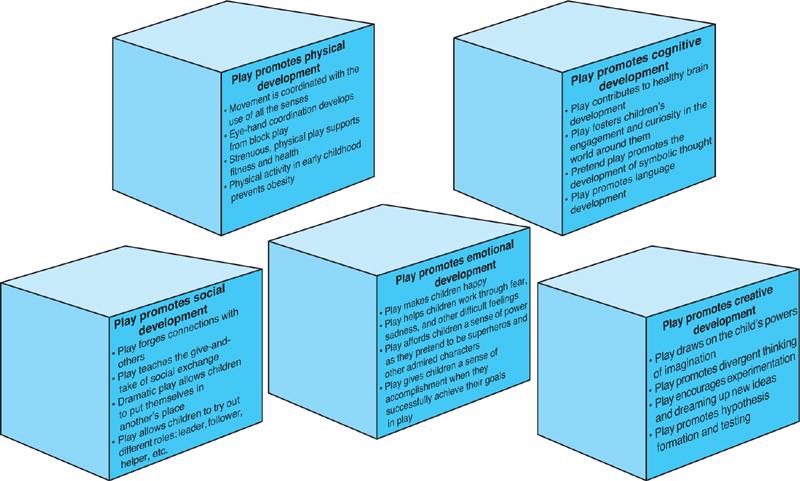

As illustrated in Figure 3.1, play forms the essential building blocks in the construction of the whole child.

Figure 3.1 How the building blocks of play construct the whole child