HIST350: World War I M2D2: The Christmas Truce Discuss the effect modern warfare had upon individual soldiers and how it prompted situations like the Christmas Truce in the winter of 1914 - 1915 (CO4,

Myth or Reality?

The 1914 Christmas Truce

by Stanley Weintraub

Author of Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce

In the 1980s, while researching the days leading up to the First World War’s armistice, I discovered a truce apparently occurred at Christmas 1914. Most historians scoffed; some still do. The bitter stage satire Oh! What a Lovely War! (1963) referred to this truce, but it was largely considered rumor and legend. If a halt in the fighting happened, it was brief and quickly suppressed—hardly more substantial than the "Angels of Mons" fantasy often accepted as fact. Was there an earlier, if only abbreviated, stillness? Impelled by curiosity, I was determined to explore the truce once I completed A Stillness Heard Round the World: The End of the Great War.

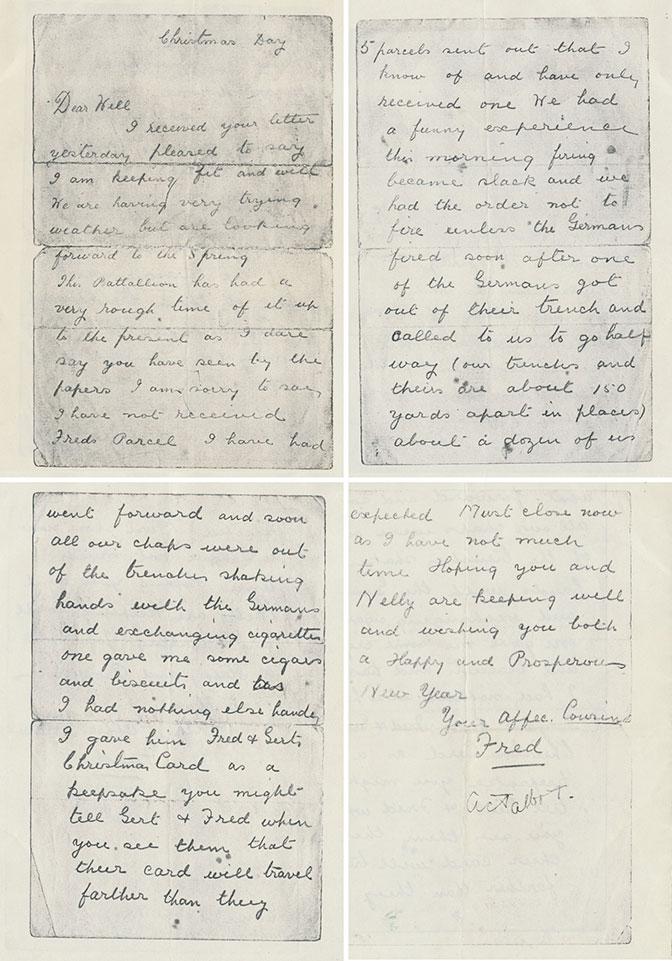

Histories were of little help. The phrase "Christmas Truce" failed to appear in the indices of almost all of them. Where gunfire allegedly ceased at Christmas 1914, it was dismissed as of little consequence. Yet when I explored letters, diaries and memoirs, I found intriguing evidences of its reality.

As my wife and I made trips to England on other research projects, we went to the collections of the Imperial War Museum and hunted through the post-Christmas daily press in the British Museum (as it was then) Newspaper Library in Colindale. We laboriously went through brittle, yellowing January 1915 newspapers, from London to Londonderry. The results were remarkable. On the letter-to-the-editor pages, no censorship was yet in place for soldier mail; some troops wrote graphic letters home.

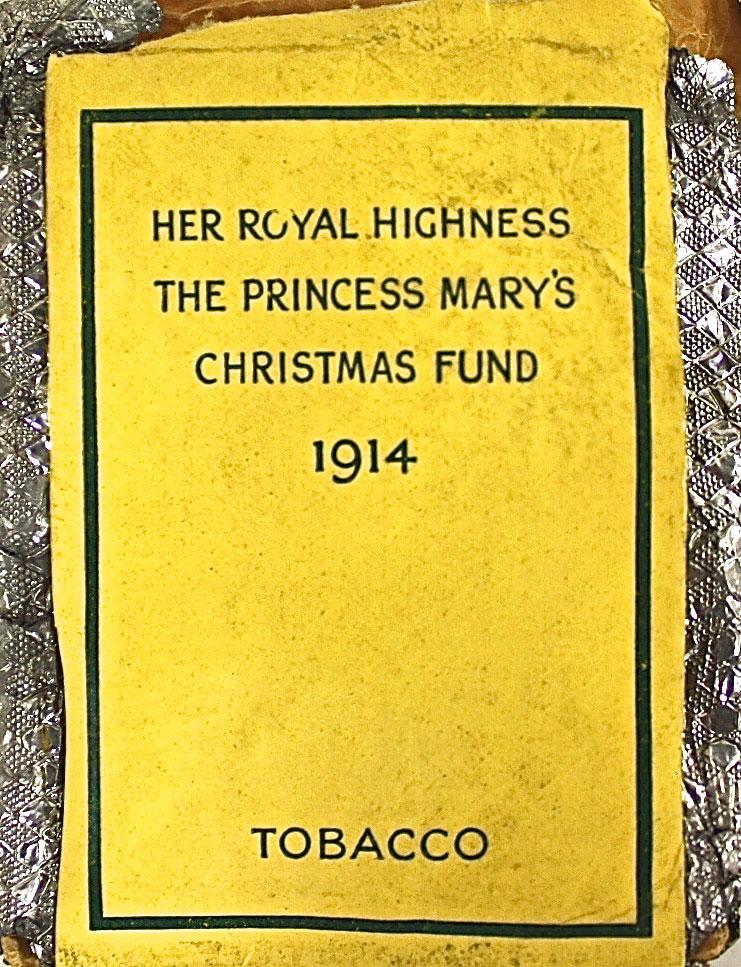

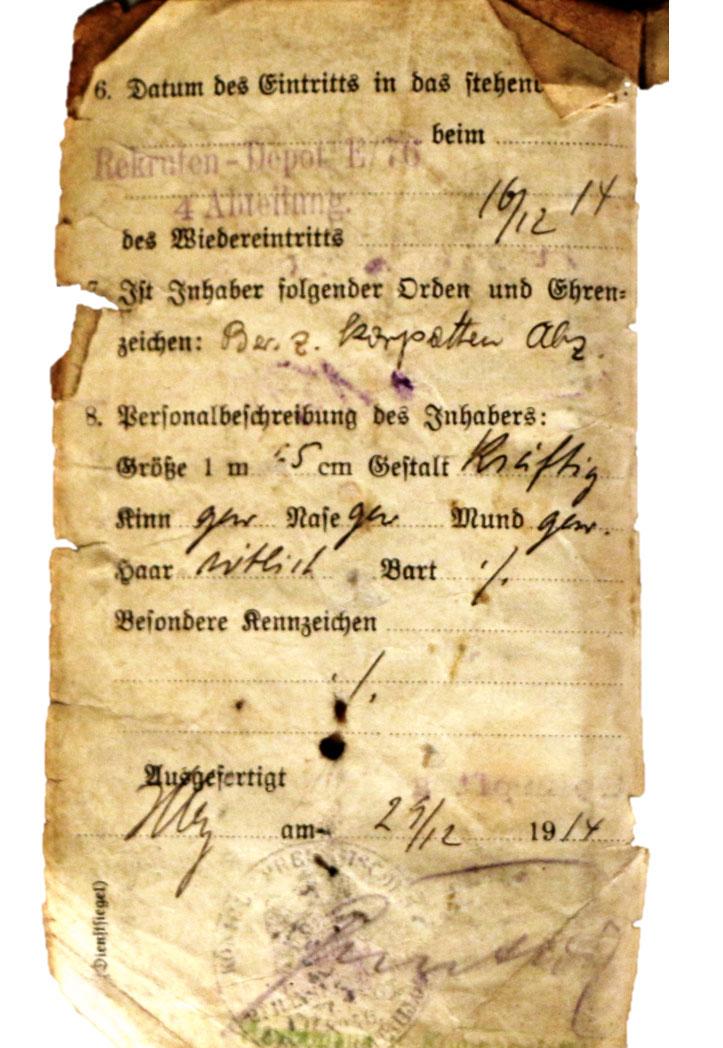

The documented reality left us, daily, in awe. Recipients often forwarded extraordinary letters to their local newspapers, which printed them without restraint. Soldiers wrote of encountering friendly enemies—ordinary blokes like themselves. Opposing sides were flush with official Christmas boxes—brass ones offered to the British troops, wooden equivalents to the Germans, filled with tobacco, sweets or snacks. The urge for bartering arose. Between the warring sides in No Man's Land, with corpses buried with due honor and shell craters filled in, became a place for fraternization rather than confrontation, for sharing Christmas gifts, singing holiday carols and bawdy service songs, even for playing football—our soccer—with improvised balls and goals. We found unit records, as well as letters and diaries, that described friendly kickabouts and even included the scores.

Despite hate propaganda spewing from headquarters on both sides, a fearsome diet of daily casualties from artillery, machine guns and small-arms fire, and trench life in disgusting filth and sludge, the ordinary soldier had no strong desire to kill or maim the enemy—who on the end of the rifle was his unanticipated counterpart—a farmer, factory worker, barber, cabbie, milkman, salesman.

Unfortunately, the pause could not last. Command discipline from afar ended the brief peace.

But it will no longer be dismissed or forgotten

Christmas Truce

by Doran Cart

Senior Curator, The National World War I Museum at Liberty Memorial

Imagine being in a cold, wet and muddy trench in a small area of Flanders [Belgium] before Christmas Day of 1914. A summer war—romantic adventure where heroes defended their homelands and way of life- was supposed to be over by Christmas. After all, it was just a regional conflict that started in the Balkans.

But now, it was Christmas- a time of peace and goodwill toward others, the celebration of the Prince of Peace. Singing started drifting across the opposing lines on the Western Front on that Christmas Eve in 1914. Perhaps imagined? A trick? An olive branch?

The sound of Christmas carols across No Man’s Land encouraged troops from both sides to exchange greetings and for some to leave their trenches to meet in No Man’s Land. What would become known as the Christmas Truce was spontaneous and experienced by hundreds, perhaps thousands, of soldiers. Exchanges of British bread for German sausages were made and German pipes and British cigarettes were lit in Christmas greetings. Wine, beer, schnapps and issue rum marked the occasion. Some ragged games of football might have taken place.

The Truce did not occur along the whole of the Western Front and it was short-lived. Similar experiences occurred on the Eastern Front. Higher command of both sides railed against it. What actually occurred in the Truce is infused with myth, wishful thinking and some truth. In reading the great numbers of letters and newspaper reports, primarily British, one gets the feeling that the observers desperately wished for an all-encompassing event of peace between enemies.

Were descriptions of football matches and singing carols of peace on earth meant to foster the idea of a Christmas Truce they wanted to report to the home folks so that they would not worry so much? If the soldiers from both sides—Englishmen, Scots, Saxons, Prussians, Belgians and French—could come together and shake hands and share food and photographs, could not the world?

The French diarist Michel Corday wrote in Paris:

“January 5th [1915]. I have before me a letter from a soldier, in which he swears, by all that he holds dear, that on the 24th December two regiments in the opposing lines put aside their arms, in defiance of their officers, and fraternized between the trenches. The soldiers exchanged cigars, shook hands, and walked about arm in arm. The Germans promised not to fire that night or the following day. They kept their word. That seemed to me symbolic – it marks a humane spirit far superior to the war.”

Descriptions sent home of the Truce described a world far removed from the gruesome reality of the war: the air filled with jagged artillery shell fragments and shrapnel balls, so thick it seemed that the sky itself was shattered iron. The countless dead were frozen in awkward positions between the lines. The earth itself frozen or so torn apart or still in furrows from lost farms presented no undisturbed fields for football matches. But if letters home and newspaper printings of them could present a picture of even the briefest respite, was that more important?

An Ancient Tradition in an Industrial War

by Michael St. Maur Sheil

Curator of Fields of Battle: 1914 - 1918

Whatever myths surround the Christmas Truce, which was observed between some British and German troops during the first Christmas of the First World War, it stands as one of the most discussed events of that war.

For soldiers of both sides, the prolongation of the war was unlooked for. Many of the Germans were reservists who anticipated a swift victory over the French whilst the British, buoyed by the conceit of being the dominant world power, expected the war to finish by Christmas. For both sides to find themselves bogged down in the wet reality of trench warfare in Flanders came as a rude awakening to the existence of the first truly industrial conflict.

It is an ancient tradition that soldiers of opposing sides fraternize during the winter when campaigning was often suspended due to bad weather. It was hardly surprising that young men of both sides should do the same in 1914. Local truces were almost entirely confined to the British held sector in Flanders as elsewhere the traditional antipathy between French and German troops prevented such overt shows of friendship.

Many German reservists had worked in Britain prior to the war and spoke good English. Both British and German accounts narrate that by early December the close proximity of the entrenched troops led to unofficial contacts with a good deal of verbal banter and even some singing sessions.

As Christmas drew near both sides were organizing the distribution of Christmas parcels: the Germans had a nationwide campaign to send ‘Libesgaben’ (love-gifts) to each soldier whilst the British Princess Mary sent a tin box with tobacco and sweets to every service-man which can only have served to increase expectations of some form of relaxation at Christmas.

The first indication of this relaxed mood came in the form of carol singing and, in the case of the Germans, the placing of makeshift Christmas trees and candles along their trench parapet on Christmas Eve. As Christmas Day dawned the weather played its part as a sharp frost hardened the ground thus enabling the men to move around more freely and even indulge in the impromptu football kickabouts which now symbolize the truce in most peoples’s mind.

Most of the accounts come from soldier’s letters and tell of numerous exchanges of food and cigars but even as they talked together the reality of war was not far away. Accounts tell of the burial of the dead and artillery batteries firing overhead, seemingly unaware of the front-line fraternization, and Rifleman Eade of the 3rd Rifle Brigade recounted a German bidding him a prophetic farewell:

Today we have peace. Tomorrow you fight for your country. I fight for mine. Good luck!

In the following days the war resumed its intensity: higher command was concerned lest the friendships of the day should lessen the offensive spirit of the front-line troops. One hundred years later the fascination of the Christmas Truce is greater than ever though the world seems sadly reluctant to learn the message that reconciliation is a more effective way to co-exist than bloody conflict.

© 2019 - National WWI Museum and Memorial | Credits