The final written paper requires you to prepare a well-written titled "Would You Advise a Friend to Invest in This Company?" based upon your research and analysis of this company's financial informati

Group Project 21

Group R

Group Project – Part 2

Phillip Morris International Inc.

This part involves the computation of the ratios and the analysis of the trends.

Debt Ratio

The debt ratio measures the extent to which borrowed money has been used to finance a company's operation. Investors like to see a low debt ratio, since it shows a company is relying less on creditors (such as banks, suppliers, etc) to finance its operation. Phillip Morris International Inc’s debt ratio for the years 2018 and 2017 are calculated below:

| 2018 | 2017 | |

| Total Debt Total Assets | 50,540,000 39,801,000 | 53,198,000 42,968,000 |

| =1.27 | =1.24 |

The above data means for every dollar that the company has in assets; it has $1.27 and $1.24 in debt in the years 2018 and 2017 respectively.

Debt Ratio Trend:

As indicated above, the debt ratio of the company has increased between 2017 and 2018. This means the company is taking in more debt or in other words more liabilities. It is an indication that the company is getting weaker and moving further away from “self sufficiency”.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin ratio provides an indication on how well a company is setting its prices and controlling its production costs. Investors like to see a high gross profit margin since it indicates the enterprise is generating more money from each sale. The Widget Manufacturing Company's gross profit margin ratios for 2018 and 2017 are calculated below.

| 2018 | 2017 | |

| Sales - Cost of goods sold | $29,625,000 - $10,758,000 $29,625,000 | $28,748,000- $ 10,432,000 |

| = 0.64 | = 0. 64 |

As seen from the data above, in both 2018 and 2017, the gross profit margin is 0.64 or 64%. This means for every dollar generated in sales, 64 cents remain in the company to pay for its operating expenses, income taxes, dividends, etc. If we were to assume, all products sold by the company sell for $1.00, then in both years the company made 64 cents from each sale.

Gross Profit Trend:

The gross profit margin has remained the same over the years 2018 and 2017. This means the company’s management team has managed to keep a balance between price setting policies and/or company’s production costs.

Free Cash Flow:

Free cash flow is the cash a company produces through its operations, less the cost of expenditures on assets. In other words, free cash flow (FCF) is the cash left over after a company pays for its operating expenses and capital expenditures, also known as CAPEX. Free cash flow is an important measurement since it shows how efficient a company is at generating cash.

| 2018 | 2017 | |

| Operating Cash Flow – Capital Expenditure | 9,478,000 - 1,436,000 | 8,912,000 - 1,548,000 |

| = 8,042,000 | = 7,364,000 |

From the data above, we see that PMI has a large amount of free cash flow which can be used to pay dividends, expand operations and deleverage its balance sheet, i.e, reduce debt. There has been an increase in the free cash flow from the year 2017 to 2018.

Free Cash Flow Trend:

Growing free cash flows are frequently a prelude to increased earnings. Companies that experience surging FCF—due to revenue growth, efficiency improvements, cost reductions, share buybacks, dividend distributions, or debt elimination—can reward investors tomorrow. That is why many in the investment community cherish FCF as a measure of value. When a firm's share price is low and free cash flow is on the rise, the odds are good that earnings and share value will soon be heading up.

Times Interest Earned:

The times interest earned ratio measures the ability of an organization to pay its debt obligations. The ratio is commonly used by lenders to ascertain whether a prospective borrower can afford to take on any additional debt. The ratio is calculated by comparing the earnings of a business that are available for use in paying down the interest expense on debt, divided by the amount of interest expense. The formula is:

Earnings before interest and taxes / Interest expense = Times interest earned

| 2018 | 2017 | |

| Earnings before interest and taxes | $11,336,000 | $11,503,000 $1,096,000 |

| =13.26 | =10.5 |

A ratio of less than one indicates that a business may not be in a position to pay its interest obligations, and so is more likely to default on its debt; a low ratio is also a strong indicator of impending bankruptcy. A much higher ratio is a strong indicator that the ability to service debt is not a problem for a borrower.

Hence, from the chart above, it indicates that from the year 2017 to 2018, the capability of taking on more debt for the company has increased and therefore it is more likely to pay off its borrower now than it was before which is a good sign for the company and means it is getting stronger.

Inventory Turnover

The inventory Turnover ratio provides an indication on whether a company has an excessive or inadequate amount of product in inventory. The ratio will determine the number of times per year a company uses or consumes an average stock of inventory.

| 2018 | 2017 | |

| Cost of Goods Sold | $ 10,758,000 | $10,432,000 |

| = 4.8 times | = 4.8 times |

As we see, the inventory turnover has not changed over the 2 years, which means the demand of the product has not gone down which is really impressive. Also, 4.8 is quite a high turnover which indicates the demand for the product exists and it sells its inventory relatively quickly, always a good sign for a company.

Accounts receivable Turnover:

Accounts receivable turnover is the number of times per year that a business collects its average accounts receivable. The ratio is used to evaluate the ability of a company to efficiently issue credit to its customers and collect funds from them in a timely manner.

Net Credit Sales / Average accounts receivable

DuPont Analysis:

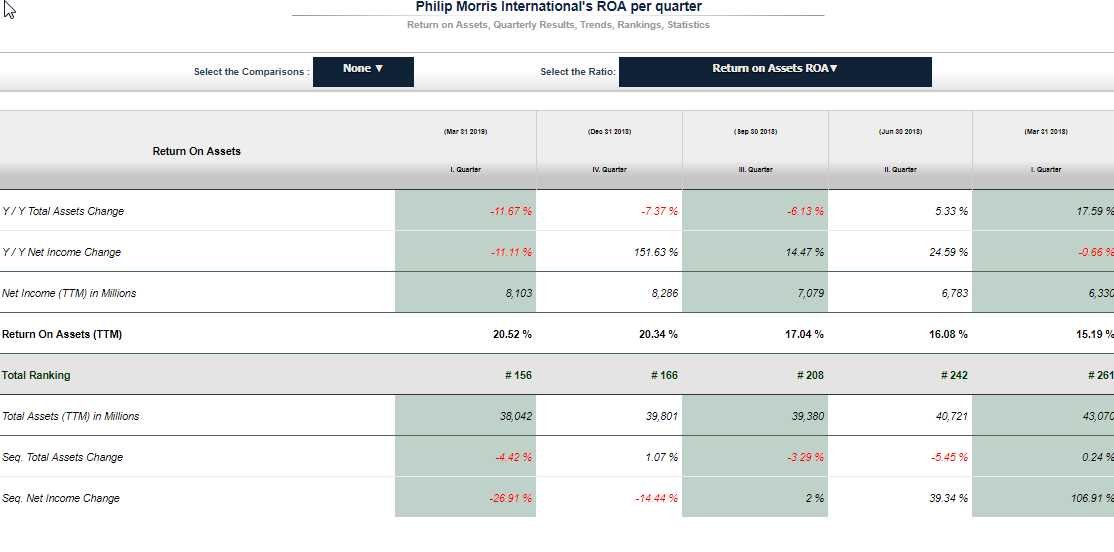

Philip Morris International Inc. yielded Return on Asset in I. Quarter below company average, at 20.52 %.

Despite deuteriation in net income, company improved return on assets compare to previous quarter.

Within Consumer Non-Cyclical sector 7 other companies have achieved higher return on assets. While Return on assets total ranking has improved so far to 156, from total ranking in previous quarter at 166.

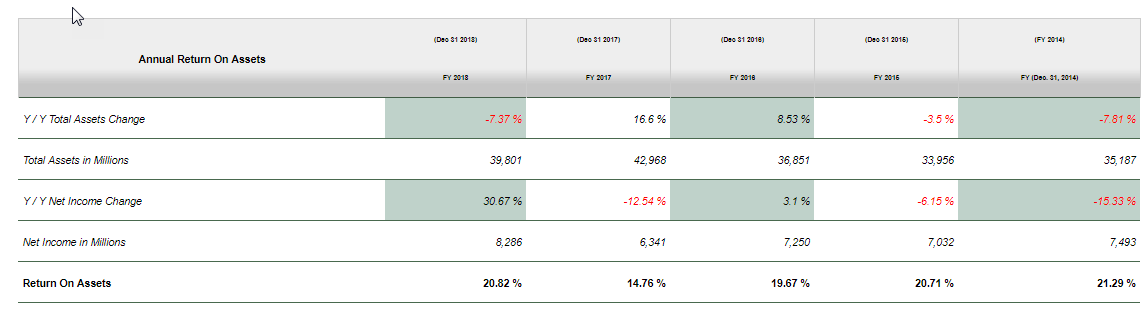

Annual returns on Assets:

Current liabilities:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s current liabilities declined from 2016 to 2017 but then increased from 2017 to 2018 exceeding 2016 level.

Noncurrent liabilities:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s noncurrent liabilities increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018 not reaching 2016 level.

Total liabilities:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s total liabilities increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018

Total PMI stockholders’ deficit:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s total PMI stockholders’ deficit increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018 not reaching 2016 level.

Current assets:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s current assets increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018 not reaching 2016 level.

Property, plant and equipment, less accumulated depreciation:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s property, plant and equipment, less accumulated depreciation increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018.

Noncurrent assets:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s noncurrent assets increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018.

Total assets:

Philip Morris International Inc.’s total assets increased from 2016 to 2017 but then slightly declined from 2017 to 2018 not reaching 2016 level.

Evaluating trends in all the above ratios.

In an industry dogged by health concerns, a shrinking domestic market, and widespread investor fears about its future, Philip Morris Companies Inc. (Morris) continues year after year to achieve record-breaking sales and profits, most of them thanks to the enduring appeal of the Marlboro Man. From a position of relative obscurity in the cigarette business in the early 1960s Philip Morris has ridden Marlboro’s success to leadership of the tobacco world, and in the process accumulated enough cash to finance a series of enormous acquisitions in the food industry. The company most recently annexed both Kraft and General Foods Corporation and is now the world’s second-largest food concern as well as the largest cigarette maker; and there is little doubt that Morris will continue to wean itself of dependence on the profitable but increasingly embattled tobacco trade.

When the tobacco cartel was dissolved by court order in 1911, a U.S. financier named George J. Whelan formed Tobacco Products Corporation to absorb a few of the splinter companies not already organized into the new Big Four of tobacco—American Tobacco, R.J. Reynolds, Lorillard, and Liggett & Meyers. When Whelan picked up the U.S. business of Philip Morris Company in 1919 he formed a new company to manage its assets, Philip Morris & Company Ltd., Inc., owned by the shareholders of Tobacco Products Corporation. Ellis and McKitterick thus became part owners and managers of the new Philip Morris brands.

While George Whelan wheeled and dealed his way toward a collapse in 1929, Reuben Ellis ran Morris as its president after 1923, at which time the company had a net income of about $100,000. Ellis’s first important move at Morris was the 1925 introduction of a new premium—20C—cigarette called Marlboro, which did well from the beginning and leveled off at a steady 500 million cigarettes a year. Industry leaders such as Camel and Lucky Strike sold more than 25 billion a year.

To further cement their alliance with the jobbers, Morris executives let it be known that they would refrain from selling to the new mass marketers directly, preventing the latter from retailing English Blend at less than the price of 15C set by the jobbers and dealers. The jobbers already were beginning to suffer from price competition with the big chains and readily agreed to Morris’s plan—the jobbers would push English Blend at 15c while Morris guaranteed that the same package would not end up on supermarket shelves at 10C.

John Roventini soon earned himself a large fortune, by bellhop standards, and Morris began its long climb to the top of the cigarette world. Sales of English Blend were strong from its introduction in January of 1933, helping Morris to triple its net income, to $1.5 million, in a single year and by 1935 to challenge Lorillard as the fourth-largest cigarette maker in the United States. Ellis and McKitterick were both dead by 1936, but under Alfred Lyon the company continued its rise, in that year selling 7.5 billion cigarettes and laying firm hold on the industry’s fourth position. Morris was viewed as something of a phenomenon, its combination of marketing expertise and jobber loyalty enabling it to take market share from the much larger and wealthier cigarette leaders such as American Tobacco and Reynolds. Alfred Lyon directed the construction of the industry’s largest and most effective sales force, and though Morris’s special relationship with the jobbers did not last long-supermarkets proving to be the wave of the future—Morris remained a company fueled by its expertise in sales and marketing.

By 1939 sales had reached $64 million, and World War II soon put even more pressure on cigarette production. When Morris sales doubled by 1942, Chairman Lyon and President Otway Chalkey began casting about for some means to expand capacity, especially difficult given the need for large amounts of tobacco cured several years before its use. When Axton-Fisher Tobacco Company of Louisville, Kentucky, was put up for sale in 1945, Morris paid a premium price—$20 million— to win its large stores of tobacco and a second manufacturing plant. The move looked good until the war’s end in August of that year precipitated a huge drop in cigarette consumption, a cut in sales made more painful by Morris’s overestimate of peacetime demand. Many of the company’s biggest orders in the fall of 1945 were left to grow stale on retail racks, and Morris’s net income plummeted just as it floated a new bond issue at the end of the year. Morris withdrew the offering and suffered a certain amount of embarrassment, but the company’s underlying business was sound, and it soon bounced back. A massive 1948 advertising campaign claiming that English Blend did not cause “cigarette hangover,” a. previously unknown disorder, led to a fresh gain in market share and profit.

Despite Morris’s success with such advertising claims, the company somehow failed to foresee the most important new development in the cigarette business in many years, the introduction of the milder and less harmful filtered cigarettes. Unlike Morris’s version of mildness, filtered cigarettes were indisputably less damaging to the throat, and increased public awareness of smoking’s real health dangers spurred a rapid shift to filters in the 1950s. Morris was evidently slow to recognize the importance of this innovation, and it was not until 1955 that the company repositioned its old filter entry Marlboro as a cigarette for everyone who responds to the myth of the American cowboy. It took time, however, for the new Marlboro image to take hold, and by 1960 Morris had slipped to sixth and last place among major U.S. tobacco companies, its best-selling entry able to do no better than tenth among the leading brands. It appeared that changing consumer preference had left Morris well out of the new era in tobacco.

Morris had at least three cards yet to play, however. One was the emergence in 1957 of a marketing tactician capable of resurrecting the glory days of Alfred Lyon. Joseph Cullman III took over management of the company in 1957 and guided its amazing growth over the course of the following two decades, much of it earned in the international market. Morris was perhaps the earliest, and certainly became the most successful, of U.S. tobacco companies in foreseeing the potential sales growth in the worldwide cigarette business. In 1960 Cullman appointed George Weissman as director of international operations, and he is generally credited with making Morris the United States’ leading exporter of tobacco products. The company’s third great resource was the Marlboro Man, who would prove in the long run to be likely the most successful advertising image ever created. For whatever combination of reasons—nostalgia for the Old West, clever packaging, tobacco taste—Marlboro almost by itself raised Morris from also-ran to industrial leader during the next quarter century.

While Joseph Cullman attended to Morris’s resurgence in the tobacco business, he also began the first of many attempts to diversify the company’s assets and thereby render it less dependent on a product that was gradually becoming known as a serious health hazard. In the mid-1950s Morris had bought into the flexible packaging and paper manufacturing trades, and in the early 1990s it added American Safety Razor, Burma Shave, and Clark chewing gum, hoping in each case to use Morris’s existing distributor network and marketing experience to sell a wider variety of consumer products. None of these early acquisitions proved to be of great value, except for its packaging division, not sold until the mid-1980s, but in 1970 the company added Miller Brewing to its holdings. Miller was then only the seventh-largest brewer in the United States, but the combination of a repositioned High Life beer and the introduction of the United States’ first low-calorie beer, Miller Lite, brought the company all the way up to number two by 1980. On the other hand, Morris’s 1978 purchase of the Seven-Up Company for $520 million was little more than a disaster, and after several failed advertising campaigns the soft drink manufacturer was sold in the mid-1980s.

In the meantime, the Marlboro Man was running wild, carrying Morris up the ranks of cigarette makers with astonishing speed. Throughout the 1960s Marlboro registered yearly leaps in popularity, especially among the growing segment of young people, and by 1973 it was the second most popular cigarette brand in the United States and accounted for roughly two-thirds of Morris’s tobacco business. In 1976 it moved past Reynolds’s Winston as the leader with 94 billion cigarettes sold that year, helping Morris to become the United States’ and the world’s second-largest seller of tobacco. In 1961, Morris had controlled 9.4% of the market; in 1976 that figure topped 25% and continued to rise. All other competitors except Reynolds declined—between the two of them, Morris and Reynolds owned well more than half the market. The two leaders thus found themselves in a very comfortable position, as growing health concerns about smoking made it unlikely that any new competitor would join the tobacco business, while the need for massive, effective advertising made it difficult for the current players to maintain their positions. The net result was abnormally large profits for the two leaders, especially as their dominance of the market really took hold in the 1980s, and they were able to raise prices frequently without fear of being undercut.

Complementing Marlboro’s success was the emergence of two new fields for Morris. The 1975 introduction of Merit brand signaled Morris’s entry into the new low-tar market, a category that would mushroom into ever larger numbers as U.S. smokers became more concerned with the deleterious effects of smoking. Second, under the guidance of George Weissman, the company’s international business had greatly expanded. While the U.S. cigarette market was flat in the 1970s and retreating by the mid-1980s, the international business continued to grow rapidly, and Morris’s Marlboro was soon the world’s bestselling cigarette. Thus, two of Morris’s responses to the increased controversy in the United States about smoking were to sell cigarettes with lower tar and to push its brands overseas, where generally less affluent people cared less about the health risks involved. Neither strategy went to the heart of Morris’s fundamental problem, the association of tobacco with disease, and the resultant product liability lawsuits. To ensure its own safety, Morris would eventually have to make a major diversification away from the tobacco business.

To that end, even as Morris passed Reynolds as the largest U.S. cigarette manufacturer it paid $5.75 billion in 1985 to acquire General Foods Corporation, the diversified food products giant. General Foods was large enough to offer Morris a significant source of revenue apart from the tobacco industry, and its reliance on advertising and an intricate distribution system was similar to Morris’s business; but General Foods was a rather lackluster company in a mature industry, and the acquisition did not kindle great enthusiasm among business analysts. They compared it unfavorably to Reynolds’s purchase of Nabisco Brands at about the same time, and predicted that the move would not be sufficient to free Morris of its tobacco habit. In 1987, for example, two years after the General Foods purchase, Morris’s total revenue had reached $27.7 billion and its operating income $4.1 billion. The lion’s share of that income—$2.7 billion—was earned by the domestic tobacco division, where the slackening of competition allowed a luxurious rate of return on its $7.6 billion in sales. By contrast, General Foods’s $10 billion contribution to revenue netted only $700 million in operating income, meaning that it was fully five times as profitable to sell a pack of Marlboros as a box of Jell-O or jar of coffee from General Foods. Indeed, 60% of Morris’s total profit for the year was generated by Marlboro’s popularity at home and abroad.

Conclusion:

In 1988 Morris took a more decisive step toward reshaping its corporate profile. For $12.9 billion it acquired Kraft, Inc., an even larger and more dynamic food products corporation. Morris Chairman Hamish Maxwell merged his two food divisions into Kraft General Foods, Inc., the world’s second-largest food company with $24 billion in sales and more than 2,500 different products. Under its chief executive officer Michael Miles, Kraft General underwent a program of labor cuts and efficiency measures designed to raise its earnings level to something approaching that of the tobacco division, and his efforts improved the division’s performance considerably. Along with Miller Brewing’s $3.5 billion in sales—it too is the second-largest competitor in its field—in the early 1990s far more than half of Morris’s revenue was derived from non-tobacco products. It appears likely that Morris will continue to use the extraordinary cash flow generated by its domestic tobacco sales to finance further moves into the food industry, where the relatively low rate of return can be eventually compensated by means of sheer size. It made one such move in 1990, buying Jacobs Suchard, a Swiss maker of coffee and chocolate for $4.1 billion.

Philip Morris' sponsorship of Ferrari was seen visually on the car again at the 2018 Japanese Grand Prix, with the cigarette company's "Mission Winnow" branding. This branding has been seen by authorities as an attempt to flout laws and rules banning tobacco advertising, and it was removed by Ferrari for the 2019 Australian Grand Prix after Australian authorities launched an investigation[57]. Ferrari also decided to remove the branding for the 2019 Canadian Grand Prix and the 2019 French Grand Prix to avoid problems with bans on tobacco advertising[58].

References:

WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. ISBN 978-92-4-159628-2.

https://www.pmi.com/who-we-are/designing-a-smoke-free-future, https://www.pmi.com/who-we-are/our-goal-and-strategies

Tiffany Kary (April 17, 2019) Philip Morris Says It Doesn’t Want You to Buy Its Cigarettes, Bloomberg accessed April 18, 2019

Zlata Rodionova (30 November 2016) - André Calantzopoulos said he would like to work with governments towards the ‘phase-out’ of cigarettes, Independent media group, accessed April 18, 2019

Felsted, Andrea (27 September 2018). "Has the Marlboro Man Gasped His Last?". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018.

"Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made the List". Fortune. Retrieved 10 November2018.

"Philip Morris Companies Inc. - Company Profile, Information, Business Description, History, Background Information on Philip Morris Companies Inc". www.referenceforbusiness.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

"Philip Morris International on the Forbes Global 2000 List". Forbes. Retrieved 20 July2018.