W5 Discussion "The Real Reason People Won’t Change" Strategies for Change Week 5: "The Real Reason People Won’t Change" Change isn’t easy. If it were, we wouldn’t need an entire course devoted to help

HBR's 10 Must Reads on Change Management: The Real Reason People Won't ChangeThe Real Reason People Won’t Change

by Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey

EVERY MANAGER IS FAMILIAR with the employee who just won’t change. Sometimes it’s easy to see why—the employee fears a shift in power, the need to learn new skills, the stress of having to join a new team. In other cases, such resistance is far more puzzling. An employee has the skills and smarts to make a change with ease, has shown a deep commitment to the company, genuinely supports the change—and yet, inexplicably, does nothing.

What’s going on? As organizational psychologists, we have seen this dynamic literally hundreds of times, and our research and analysis have recently led us to a surprising yet deceptively simple conclusion. Resistance to change does not reflect opposition, nor is it merely a result of inertia. Instead, even as they hold a sincere commitment to change, many people are unwittingly applying productive energy toward a hidden competing commitment. The resulting dynamic equilibrium stalls the effort in what looks like resistance but is in fact a kind of personal immunity to change.

When you, as a manager, uncover an employee’s competing commitment, behavior that has seemed irrational and ineffective suddenly becomes stunningly sensible and masterful—but unfortunately, on behalf of a goal that conflicts with what you and even the employee are trying to achieve. You find out that the project leader who’s dragging his feet has an unrecognized competing commitment to avoid the even tougher assignment—one he fears he can’t handle—that might come his way next if he delivers too successfully on the task at hand. Or you find that the person who won’t collaborate despite a passionate and sincere commitment to teamwork is equally dedicated to avoiding the conflict that naturally attends any ambitious team activity.

In these pages, we’ll look at competing commitments in detail and take you through a process to help your employees overcome their immunity to change. The process may sound straightforward, but it is by no means quick or easy. On the contrary, it challenges the very psychological foundations upon which people function. It asks people to call into question beliefs they’ve long held close, perhaps since childhood. And it requires people to admit to painful, even embarrassing, feelings that they would not ordinarily disclose to others or even to themselves. Indeed, some people will opt not to disrupt their immunity to change, choosing instead to continue their fruitless struggle against their competing commitments.

As a manager, you must guide people through this exercise with understanding and sensitivity. If your employees are to engage in honest introspection and candid disclosure, they must understand that their revelations won’t be used against them. The goal of this exploration is solely to help them become more effective, not to find flaws in their work or character. As you support your employees in unearthing and challenging their innermost assumptions, you may at times feel you’re playing the role of a psychologist. But in a sense, managers are psychologists. After all, helping people overcome their limitations to become more successful at work is at the very heart of effective management.

We’ll describe this delicate process in detail, but first let’s look at some examples of competing commitments in action.

Shoveling Sand Against the Tide

Competing commitments cause valued employees to behave in ways that seem inexplicable and irremediable, and this is enormously frustrating to managers. Take the case of John, a talented manager at a software company. (Like all examples in this article, John’s experiences are real, although we have altered identifying features. In some cases, we’ve constructed composite examples.) John was a big believer in open communication and valued close working relationships, yet his caustic sense of humor consistently kept colleagues at a distance. And though he wanted to move up in the organization, his personal style was holding him back. Repeatedly, John was counseled on his behavior, and he readily agreed that he needed to change the way he interacted with others in the organization. But time after time, he reverted to his old patterns. Why, his boss wondered, did John continue to undermine his own advancement?

Idea in Brief

Tearing out your managerial hair over employees who just won’t change—especially the ones who are clearly smart, skilled, and deeply committed to your company and your plans for improvement?

Before you throw up your hands in frustration, listen to recent psychological research: These otherwise valued employees aren’t purposefully subversive or resistant. Instead, they may be unwittingly caught in a competing commitment —a subconscious, hidden goal that conflicts with their stated commitments. For example: A project leader dragging his feet has an unrecognized competing commitment to avoid tougher assignments that may come his way if he delivers too successfully on the current project.

Competing commitments make people personally immune to change. Worse, they can undermine your best employees’—and your company’s—success.

If the thought of tackling these hidden commitments strikes you as a psychological quagmire, you’re not alone. However, you can help employees uncover and move beyond their competing commitments—without having to “put them on the couch.” But take care: You’ll be challenging employees’ deepest psychological foundations and questioning their longest-held beliefs.

Why bother, you ask? Consider the rewards: You help talented employees become much more effective and make far more significant contributions to your company. And, you discover what’s really going on when people who seem genuinely committed to change dig in their heels.

Idea in Practice

Use these steps to break through an employee’s immunity to change:

Diagnose the Competing Commitment

Take two to three hours to explore these questions with the employee:

“What would you like to see changed at work, so you could be more effective, or so work would be more satisfying?” Responses are usually complaints—e.g., Tom, a manager, grumbled, “My subordinates keep me out of the loop.”

“What commitment does your complaint imply?” Complaints indicate what people care about most—e.g., Tom revealed, “I believe in open, candid communication.”

“What are you doing, or not doing, to keep your commitment from being more fully realized?” Tom admitted, “When people bring bad news, I tend to shoot the messenger.”

“Imagine doing the opposite of the undermining behavior. Do you feel any discomfort, worry, or vague fear?” Tom imagined listening calmly and openly to bad news and concluded, “I’m afraid I’ll hear about a problem I can’t fix.”

“By engaging in this undermining behavior, what worrisome outcome are you committed to preventing?” The answer is the competing commitment—what causes them to dig in their heels against change. Tom conceded, “I’m committed to not learning about problems I can’t fix.”

Identify the Big Assumption

This is the worldview that colors everything we see and that generates our competing commitment.

People often form big assumptions early in life and then seldom, if ever, examine them. They’re woven into the very fabric of our lives. But only by bringing them into the light can people finally challenge their deepest beliefs and recognize why they’re engaging in seemingly contradictory behavior.

To identify the big assumption, guide an employee through this exercise:

Create a sentence stem that inverts the competing commitment, then “fill in the blank.” Tom turned his competing commitment to not hearing about problems he couldn’t fix into this big assumption: “I assume that if I did hear about problems I can’t fix, people would discover I’m not qualified to do the job.”

Test—and Consider Replacing—the Big Assumption

By analyzing the circumstances leading up to and reinforcing their big assumptions, employees empower themselves to test those assumptions. They can now carefully and safely experiment with behaving differently than they usually do.

After running several such tests, employees may feel ready to reevaluate the big assumption itself—and possibly even replace it with a new worldview that more accurately reflects their abilities.

At the very least, they’ll eventually find more effective ways to support their competing commitment without sabotaging other commitments. They achieve ever-greater accomplishments—and your organization benefits by finally gaining greater access to their talents.

As it happened, John was a person of color working as part of an otherwise all-white executive team. When he went through an exercise designed to help him unearth his competing commitments, he made a surprising discovery about himself. Underneath it all, John believed that if he became too well integrated with the team, it would threaten his sense of loyalty to his own racial group. Moving too close to the mainstream made him feel very uncomfortable, as if he were becoming “one of them” and betraying his family and friends. So when people gathered around his ideas and suggestions, he’d tear down their support with sarcasm, inevitably (and effectively) returning himself to the margins, where he was more at ease. In short, while John was genuinely committed to working well with his colleagues, he had an equally powerful competing commitment to keeping his distance.

Consider, too, a manager we’ll call Helen, a rising star at a large manufacturing company. Helen had been assigned responsibility for speeding up production of the company’s most popular product, yet she was spinning her wheels. When her boss, Andrew, realized that an important deadline was only two months away and she hadn’t filed a single progress report, he called her into a meeting to discuss the project. Helen agreed that she was far behind schedule, acknowledging that she had been stalling in pulling together the team. But at the same time she showed a genuine commitment to making the project a success. The two developed a detailed plan for changing direction, and Andrew assumed the problem was resolved. But three weeks after the meeting, Helen still hadn’t launched the team.

Getting Groups to Change

ALTHOUGH COMPETING COMMITMENTS and big assumptions tend to be deeply personal, groups are just as susceptible as individuals to the dynamics of immunity to change. Face-to-face teams, departments, and even companies as a whole can fall prey to inner contradictions that “protect” them from significant changes they may genuinely strive for. The leadership team of a video production company, for instance, enjoyed a highly collaborative, largely flat organizational structure. A year before we met the group, team members had undertaken a planning process that led them to a commitment of which they were unanimously in favor: In order to ensure that the company would grow in the way the team wished, each of the principals would take responsibility for aggressively overseeing a distinct market segment.

The members of the leadership team told us they came out of this process with a great deal of momentum. They knew which markets to target, they had formed some concrete plans for moving forward, and they had clearly assigned accountability for each market. Yet a year later, the group had to admit it had accomplished very little, despite the enthusiasm. There were lots of rational explanations: “We were unrealistic; we thought we could do new things and still have time to keep meeting our present obligations.” “We didn’t pursue new clients aggressively enough.” “We tried new things but gave up too quickly if they didn’t immediately pay off.”

Efforts to overcome these barriers—to pursue clients more aggressively, for instance—didn’t work because they didn’t get to the cause of the unproductive behavior. But by seeing the team’s explanations as a potential window into the bigger competing commitment, we were able to help the group better understand its predicament. We asked, “Can you identify even the vaguest fear or worry about what might happen if you did more aggressively pursue the new markets? Or if you reduced some of your present activity on behalf of building the new business?” Before long, a different discourse began to emerge, and the other half of a striking groupwide contradiction came into view: The principals were worried that pursuing the plan would drive them apart functionally and emotionally.

“We now realize we are also committed to preserving the noncompetitive, intellectually rewarding, and cocreative spirit of our corporate enterprise,” they concluded. On behalf of this commitment, the team members had to commend themselves on how “noncompetitively” and “cocreatively” they were finding ways to undermine the strategic plans they still believed were the best route to the company’s future success. The team’s big assumptions? “We assumed that pursuing the target-market strategy, with each of us taking aggressive responsibility for a given segment, would create the ‘silos’ we have long happily avoided and would leave us more isolated from one another. We also assumed the strategy would make us more competitively disposed toward one another.” Whether or not the assumptions were true, they would have continued to block the group’s efforts until they were brought to light. In fact, as the group came to discover, there were a variety of moves that would allow the leadership team to preserve a genuinely collaborative collegiality while pursuing the new corporate strategy.

Why was Helen unable to change her behavior? After intense self-examination in a workshop with several of her colleagues, she came to an unexpected conclusion: Although she truly wanted the project to succeed, she had an accompanying, unacknowledged commitment to maintaining a subordinate position in relation to Andrew. At a deep level, Helen was concerned that if she succeeded in her new role—one she was excited about and eager to undertake—she would become more a peer than a subordinate. She was uncertain whether Andrew was prepared for the turn their relationship would take. Worse, a promotion would mean that she, not Andrew, would be ultimately accountable for the results of her work—and Helen feared she wouldn’t be up to the task.

These stories shed some light on the nature of immunity to change. The inconsistencies between John’s and Helen’s stated goals and their actions reflect neither hypocrisy nor unspoken reluctance to change but the paralyzing effect of competing commitments. Any manager who seeks to help John communicate more effectively or Helen move her project forward, without understanding that each is also struggling unconsciously toward an opposing agenda, is shoveling sand against the tide.

Diagnosing Immunity to ChangeCompeting commitments aren’t distressing only to the boss; they’re frustrating to employees as well. People with the most sincere intentions often unwittingly create for themselves Sisyphean tasks. And they are almost always tremendously relieved when they discover just why they feel as if they are rolling a boulder up a hill only to have it roll back down again. Even though uncovering a competing commitment can open up a host of new concerns, the discovery offers hope for finally accomplishing the primary, stated commitment.

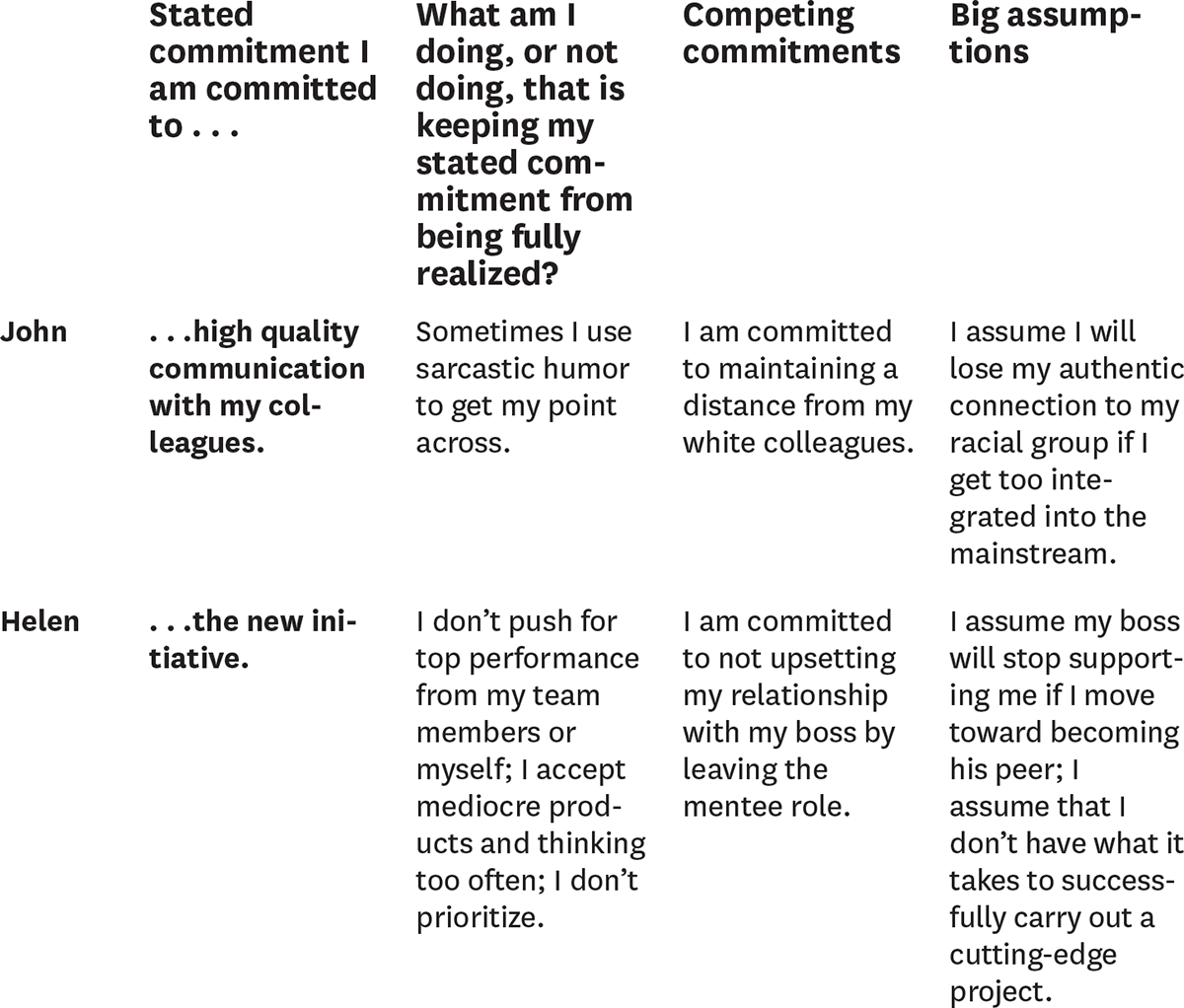

A diagnostic test for immunity to change

The most important steps in diagnosing immunity to change are uncovering employees’ competing commitments and unearthing their big assumptions. To do so, we ask a series of questions and record key responses in a simple grid. Below we’ve listed the responses for six people who went through this exercise, including the examples described in the text. The grid paints a picture of the change-immunity system, making sense of a previously puzzling dynamic.

Based on the past 15 years of working with hundreds of managers in a variety of companies, we’ve developed a three-stage process to help organizations figure out what’s getting in the way of change. First, managers guide employees through a set of questions designed to uncover competing commitments. Next, employees examine these commitments to determine the underlying assumptions at their core. And finally, employees start the process of changing their behavior.

We’ll walk through the process fairly quickly below, but it’s important to note that each step will take time. Just uncovering the competing commitment will require at least two or three hours, because people need to reflect on each question and the implications of their answers. The process of challenging competing commitments and making real progress toward overcoming immunity to change unfolds over a longer period—weeks or even months. But just getting the commitments on the table can have a noticeable effect on the decisions people make and the actions they take.

Uncovering Competing CommitmentsOvercoming immunity to change starts with uncovering competing commitments. In our work, we’ve found that even though people keep their competing commitments well hidden, you can draw them out by asking a series of questions—as long as the employees believe that personal and potentially embarrassing disclosures won’t be used inappropriately. It can be very powerful to guide people through this diagnostic exercise in a group—typically with several volunteers making their own discoveries public—so people can see that others, even the company’s star performers, have competing commitments and inner contradictions of their own.

The first question we ask is, What would you like to see changed at work, so that you could be more effective or so that work would be more satisfying? Responses to this question are nearly always couched in a complaint—a form of communication that most managers bemoan because of its negative, unproductive tone. But complaints can be immensely useful. People complain only about the things they care about, and they complain the loudest about the things they care about most. With little effort, people can turn their familiar, uninspiring gripes into something that’s more likely to energize and motivate them—a commitment, genuinely their own.

To get there, you need to ask a second question: What commitments does your complaint imply? A project leader we worked with, we’ll call him Tom, had grumbled, “My subordinates keep me out of the loop on important developments in my project.” This complaint yielded the statement, “I believe in open and candid communication.” A line manager we’ll call Mary lamented people’s unwillingness to speak up at meetings; her complaint implied a commitment to shared decision making.

While undoubtedly sincere in voicing such commitments, people can nearly always identify some way in which they are in part responsible for preventing them from being fulfilled. Thus, the third question is: What are you doing, or not doing, that is keeping your commitment from being more fully realized? Invariably, in our experience, people can identify these undermining behaviors in just a couple of seconds. For example, Tom admitted: “When people bring me bad news, I tend to shoot the messenger.” And Mary acknowledged that she didn’t delegate much and that she sometimes didn’t release all the information people needed in order to make good decisions.

In both cases, there may well have been other circumstances contributing to the shortfalls, but clearly both Tom and Mary were engaging in behavior that was affecting the people around them. Most people recognize this about themselves right away and are quick to say, “I need to stop doing that.” Indeed, Tom had repeatedly vowed to listen more openly to potential problems that would slow his projects. However, the purpose of this exercise is not to make these behaviors disappear—at least not now. The purpose is to understand why people behave in ways that undermine their own success.

The next step, then, is to invite people to consider the consequences of forgoing the behavior. We do this by asking a fourth question: If you imagine doing the opposite of the undermining behavior, do you detect in yourself any discomfort, worry, or vague fear? Tom imagined himself listening calmly and openly to some bad news about a project and concluded, “I’m afraid I’ll hear about a problem that I can’t fix, something that I can’t do anything about.” And Mary? She considered allowing people more latitude and realized that, quite frankly, she feared people wouldn’t make good decisions and she would be forced to carry out a strategy she thought would lead to an inferior result.

The final step is to transform that passive fear into a statement that reflects an active commitment to preventing certain outcomes. We ask, By engaging in this undermining behavior, what worrisome outcome are you committed to preventing? The resulting answer is the competing commitment, which lies at the very heart of a person’s immunity to change. Tom admitted, “I am committed to not learning about problems I can’t fix.” By intimidating his staff, he prevented them from delivering bad news, protecting himself from the fear that he was not in control of the project. Mary, too, was protecting herself—in her case, against the consequences of bad decisions. “I am committed to making sure my group does not make decisions that I don’t like.”

Such revelations can feel embarrassing. While primary commitments nearly always reflect noble goals that people would be happy to shout from the rooftops, competing commitments are very personal, reflecting vulnerabilities that people fear will undermine how they are regarded both by others and themselves. Little wonder people keep them hidden and hasten to cover them up again once they’re on the table.

But competing commitments should not be seen as weaknesses. They represent some version of self-protection, a perfectly natural and reasonable human impulse. The question is, if competing commitments are a form of self-protection, what are people protecting themselves from? The answers usually lie in what we call their big assumptions—deeply rooted beliefs about themselves and the world around them. These assumptions put an order to the world and at the same time suggest ways in which the world can go out of order. Competing commitments arise from these assumptions, driving behaviors unwittingly designed to keep the picture intact.

Examining the Big AssumptionPeople rarely realize they hold big assumptions because, quite simply, they accept them as reality. Often formed long ago and seldom, if ever, critically examined, big assumptions are woven into the very fabric of people’s existence. (For more on the grip that big assumptions hold on people, see the sidebar “Big Assumptions: How Our Perceptions Shape Our Reality.”) But with a little help, most people can call them up fairly easily, especially once they’ve identified their competing commitments. To do this, we first ask people to create the beginning of a sentence by inverting the competing commitment, and then we ask them to fill in the blank. For Tom (“I am committed to not hearing about problems I can’t fix”), the big assumption turned out to be, “I assume that if I did hear about problems I can’t fix, people would discover I’m not qualified to do my job.” Mary’s big assumption was that her teammates weren’t as smart or experienced as she and that she’d be wasting her time and others’ if she didn’t maintain control. Returning to our earlier story, John’s big assumption might be, “I assume that if I develop unambivalent relationships with my white coworkers, I will sacrifice my racial identity and alienate my own community.”

This is a difficult process, and it doesn’t happen all at once, because admitting to big assumptions makes people uncomfortable. The process can put names to very personal feelings people are reluctant to disclose, such as deep-seated fears or insecurities, highly discouraging or simplistic views of human nature, or perceptions of their own superior abilities or intellect. Unquestioning acceptance of a big assumption anchors and sustains an immune system: A competing commitment makes all the sense in the world, and the person continues to engage in behaviors that support it, albeit unconsciously, to the detriment of his or her “official,” stated commitment. Only by bringing big assumptions to light can people finally challenge their assumptions and recognize why they are engaging in seemingly contradictory behavior.

Big Assumptions: How Our Perceptions Shape Our Reality

BIG ASSUMPTIONS REFLECT the very human manner in which we invent or shape a picture of the world and then take our inventions for reality. This is easiest to see in children. The delight we take in their charming distortions is a kind of celebration that they are actively making sense of the world, even if a bit eccentrically. As one story goes, two youngsters had been learning about Hindu culture and were taken with a representation of the universe in which the world sits atop a giant elephant, and the elephant sits atop an even more giant turtle. “I wonder what the turtle sits on,” says one of the children. “I think from then on,” says the other, “it’s turtles all the way down.”

But deep within our amusement may lurk a note of condescension, an implication that this is what distinguishes children from grown-ups. Their meaning-making is subject to youthful distortions, we assume. Ours represents an accurate map of reality.

But does it? Are we really finished discovering, once we have reached adulthood, that our maps don’t match the territory? The answer is clearly no. In our 20 years of longitudinal and cross-sectional research, we’ve discovered that adults must grow into and out of several qualitatively different views of the world if they are to master the challenges of their life experiences (see Robert Kegan, In Over Our Heads, Harvard University Press, 1994).

A woman we met from Australia told us about her experience living in the United States for a year. “Not only do you drive on the wrong side of the street over here,” she said, “your steering wheels are on the wrong side, too. I would routinely pile into the right side of the car to drive off, only to discover I needed to get out and walk over to the other side.

“One day,” she continued, “I was thinking about six different things, and I got into the right side of the car, took out my keys, and was prepared to drive off. I looked up and thought to myself, ‘My God, here in the violent and lawless United States, they are even stealing steering wheels!’”

Of course, the countervailing evidence was just an arm’s length to her left, but—and this is the main point—why should she look? Our big assumptions create a disarming and deluding sense of certainty. If we know where a steering wheel belongs, we are unlikely to look for it some place else. If we know what our company, department, boss, or subordinate can and can’t do, why should we look for countervailing data—even if it is just an arm’s length away?

Questioning the Big AssumptionOnce people have identified their competing commitments and the big assumptions that sustain them, most are prepared to take some immediate action to overcome their immunity. But the first part of the process involves observation, not action, which can be frustrating for high achievers accustomed to leaping into motion to solve problems. Let’s take a look at the steps in more detail.

Step 1: Notice and record current behaviorEmployees must first take notice of what does and doesn’t happen as a consequence of holding big assumptions to be true. We specifically ask people not to try to make any changes in their thinking or behavior at this time but just to become more aware of their actions in relation to their big assumptions. This gives people the opportunity to develop a better appreciation for how and in what contexts big assumptions influence their lives. John, for example, who had assumed that working well with his white colleagues would estrange him from his ethnic group, saw that he had missed an opportunity to get involved in an exciting, high-profile initiative because he had mocked the idea when it first came up in a meeting.

Step 2: Look for contrary evidenceNext, employees must look actively for experiences that might cast doubt on the validity of their big assumptions. Because big assumptions are held as fact, they actually inform what people see, leading them to systematically (but unconsciously) attend to certain data and avoid or ignore other data. By asking people to search specifically for experiences that would cause them to question their assumptions, we help them see that they have filtering out certain types of information—information that could weaken the grip of the big assumptions.

When John looked around him, he considered for the first time that an African-American manager in another department had strong working relationships with her mostly white colleagues, yet seemed not to have compromised her personal identity. He also had to admit that when he had been thrown onto an urgent task force the year before, he had worked many hours alongside his white colleagues and found the experience satisfying; he had felt of his usual ambivalence.

Step 3: Explore the historyIn this step, we people to become the “biographers” of their assumptions: How and when did the assumptions first take hold? How long have they been around? What have been some of their critical turning points?

Typically, this step leads people to earlier life experiences, almost always to times before their current jobs and relationships with current coworkers. This reflection usually makes people dissatisfied with the foundations of their big assumptions, especially when they see that these have accompanied them to their current positions and have been coloring their experiences for many years. Recently, a CEO expressed astonishment as she realized she’d been applying the same self-protective stance in her work that she’d developed during a difficult divorce years before. Just as commonly, as was the case for John, people trace their big assumptions to early experiences with parents, siblings, or friends. Understanding the circumstances that influenced the formation of the assumptions can free people to consider whether these beliefs apply to their present selves.

Step 4: Test the assumptionThis step entails creating and running a modest test of the big assumption. This is the first time we ask people to consider making changes in their behavior. Each employee should come up with a scenario and run it by a partner who serves as a sounding board. (Left to their own devices, people tend to create tests that are either too risky or so tentative that they don’t actually challenge the assumption and in fact reaf-firm its validity.) After conferring with a partner, John, for instance, volunteered to join a short-term committee looking at his department’s process for evaluating new product ideas. Because the team would dissolve after a month, he would be able to extricate himself fairly quickly if he grew too uncomfortable with the relationships. But the experience would force him to spend a significant amount of time with several of his white colleagues during that month and would provide him an opportunity to test his sense of the real costs of being a full team member.

Step 5: Evaluate the resultsIn the last step, employees evaluate the test results, evaluate the test itself, design and run new tests, and eventually question the big assumptions. For John, this meant signing up for other initiatives and making initial social overtures to white coworkers. At the same time, by engaging in volunteer efforts within his community outside of work, he made sure that his ties to his racial group were not compromised.

It is worth noting that revealing a big assumption doesn’t necessarily mean it will be exposed as false. But even if a big assumption does contain an element of truth, an individual can often find more effective ways to operate once he or she has had a chance to challenge the assumption and its hold on his or her behavior. Indeed, John found a way to support the essence of his competing commitment—to maintain his bond with his racial group—while minimizing behavior that sabotaged his other stated commitments.

Uncovering Your Own ImmunityAs you go through this process with your employees, remember that managers are every bit as susceptible to change immunity as employees are, and your competing commitments and big assumptions can have a significant impact on the people around you. Returning once more to Helen’s story: When we went through this exercise with her boss, Andrew, it turned out that he was harboring some contradictions of his own. While he was committed to the success of his subordinates, Andrew at some level assumed that he alone could meet his high standards, and as a result he was laboring under a competing commitment to maintain absolute control over his projects. He was unintentionally communicating this lack of confidence to his subordinates—including Helen—in subtle ways. In the end, Andrew’s and Helen’s competing commitments were, without their knowledge, mutually reinforcing, keeping Helen dependent on Andrew and allowing Andrew to control her projects.

Helen and Andrew are still working through this process, but they’ve already gained invaluable insight into their behavior and the ways they are impeding their own progress. This may seem like a small step, but bringing these issues to the surface and confronting them head-on is challenging and painful—yet tremendously effective. It allows managers to see, at last, what’s really going on when people who are genuinely committed to change nonetheless dig in their heels. It’s not about identifying unproductive behavior and systematically making plans to correct it, as if treating symptoms would cure a disease. It’s not t about coaxing or cajoling or even giving poor performance reviews. It’s about understanding the complexities of people’s behavior, guiding them through a productive process to bring their competing commitments to the surface, and helping them cope with the inner conflict that is preventing them from achieving their goals.

Step 4

Communicate for Buy-In

In successful change efforts, the vision and strategies are not locked in a room with the guiding team. The direction of change is widely communicated, and communicated for both understanding and gut-level buy-in. The goal: to get as many people as possible acting to make the vision a reality.

Vision communication fails for many reasons. Perhaps the most obvious is lack of clarity. People wonder, “What are they talking about?” Usually, this lack of clarity means step 3 has been done poorly. Fuzzy or illogical visions and strategies cannot be communicated with clarity and sound logic. But, in addition, step 4 has its own set of distinct challenges that can undermine a transformation, even if the vision is perfect.

More Than Data Transfer

When we communicate about a large-scale change, common responses are: “I don’t see why we need to change that much,” “They don’t know what they’re doing,” “We’ll never be able to pull this off,” “Are these guys serious or is this a part of some more complicated game I don’t understand?” “Are they just trying to line their pockets at my expense?” and “Good heavens, what will happen to me?” In successful change efforts, a guiding team doesn’t argue with this reality, declaring it unfair or illogical. They simply find ways to deal with it. The key is one basic insight: Good communication is not just data transfer. You need to show people something that addresses their anxieties, that accepts their anger, that is credible in a very gut-level sense, and that evokes faith in the vision. Great leaders do this well almost effortlessly. The rest of us usually need to do homework before we open our mouths.

Preparing for Q&A

From Mike Davies and Kevin Bygate

Three years after we initiated all the changes, everybody in the organization, from senior management on down, had a different job. Pulling that off without disrupting our customers was quite a trick.

The basic communication about the new team-based organization was carried out by twenty managers, all of whom had helped develop the idea. Eventually, they talked to every worker and trade union. To help the twenty managers, we did a great deal of work, both on the presentation and the preparation for the Q&A. We thought a great deal about how the changes might affect people. Within the uncertainties and the timetables, there were limits to what we knew, but we pushed the limits. We wanted to be able to answer as many questions as possible of the “what does this mean to me” variety. Without that sort of Q&A, we felt it would be very difficult for our people to buy into the direction we were heading and to understand why the team-based strategy was right.

In preparing for the Q&A, we used role plays. The twenty presenters would be themselves and the rest of the management would play the workforce. We would ask every tough question we could think of. We would try to tear the presentation to bits. So some chap would make his pitch and a hand would shoot up and say, “If I’ve only got experience of forklift truck driving and none of this other stuff, does that mean I’m going to be made redundant? Are you going to throw me out?” And before you could do much with that, another person would say, “How are we going to decide who the new team leaders are? How will we know that the process is going to be fair? We have a union because once so much was not done in a fair way. Won’t the union have to have a big role?” About the time your head was spinning, another would ask, with a suspicious look on his face, “I’ve heard this is nothing but a way to disguise cost cutting.” The first time you tried to deal with all this you usually ended up looking like a fool, confusing everyone, including yourself, or causing a riot in the “workforce.”

We created a question-and-answer back-up document for the presenters. It had some 200 questions that came up in the role plays. Each had an answer. For example, one of the questions was “What will happen to the existing management structure, in particular the plant supervisor’s role?” Now, you could have talked for ten minutes trying to begin answering that question. The response in the document took less than thirty seconds. The idea was always to be as clear, simple, and accurate as possible.

Our twenty “communicators” practiced and practiced. They learned the responses, tried them out, and did more role plays until they felt comfortable with nearly anything that might come at them. Handling 200 issues well may sound like too much, but we did it. Remember that this was not like answering questions about beekeeping first, then about fixing a tire, then who knows what topic. Everything was about us and where we were headed. The clearer that is in your mind, the easier it is to remember the issues and answers, and the easier it is to respond in a way that can be communicated well.

In some cases it was just a matter of learning information you did not know. In many cases the problem was how best to respond with the information you had. Questions can come out as statements, not questions. They can be driven by a lot of feeling, not thought. You need to respond to the feeling in the right way. With practice, you can learn to do it. Our people did, and most of them were very effective, even though they were not communication specialists. They didn’t get beat up. They walked away feeling successful, which they were.

Self-confidence was often the key issue. I think you can often tell in thirty seconds whether the person presenting information really believes in it, really understands what is going on. This makes the message more acceptable. For us it was critical that the workers and unions found it acceptable.

I can’t believe that what we did is not applicable nearly everywhere. I think too many people wing it.

Some employees, upon hearing that there will be a merger, or that there is going to be a commitment to developing a revolutionary new product, or whatever, will cheer. “It’s about time.” Some will just need help in understanding. “I’m sure this is great—just say the vision again, I’m not sure if I get the third strategy.” But most people will be nervous, even if they feel a sense of urgency to do something, even if they think the change drivers are okay, even if the vision is sensible. All sorts of insecurities bubble to the surface. People have a fear that softly whispers: “Will this hurt me?” In “Q&A,” they dealt with this reality by creating a play of sorts that spoke to these feelings, that quieted them, that even generated some excitement and new hope for the future. The play came in two acts: presentation, then questions and answers. They wrote the play with the audience constantly in mind. Who are they, what do they need to know, how will they respond? They chose the actors. They rehearsed. The second act was ten times as difficult as the first, so they rehearsed with a simulated, tough audience. Only when the actors were comfortable did they put on the performances. Then:

• They showed the audience a capacity to respond quickly and clearly, suggesting that the change ideas were not muddled.

• The actors responded with conviction, suggesting that they had faith in what they were doing.

• They handled tough questions without becoming defensive, suggesting that they thought what they were doing was good for the enterprise and its employees.

Yes, the audience received information, but, more important, their feelings were addressed and modified. With that, minds opened to hear more clearly any direction for change, and energy developed for helping make it happen.

Preparing for Q&A

SEEING

Employees are given a well-prepared presentation about the change effort and are encouraged to ask any questions. During Q&A, each presenter responds quickly and clearly, with conviction, and without becoming defensive. This shows people that the ideas are not muddled, that the presenters have faith in the vision, and that those answering the questions think the changes are good for employees.

FEELING

Fear, anger, distrust, and pessimism shrink. A feeling of relief grows. Optimism that the changes are good, and faith in the future, grow.

CHANGING

Employees start to buy into the change. They waste less time having angry or anxious discussions among themselves. When asked, they start to take steps to help make the change happen.

Cutting through the Avalanche of Information

Imagine a Q&A session, as carefully planned as in the previous story, being given only for twenty minutes at the end of a day-long meeting, a meeting that included four other discussions, nine speeches, and more. Sounds ridiculous, but we do the equivalent of that all the time.

Our channels of communication are overstuffed. Such is the nature of modern life. But most of the flood of information is irrelevant to us, or marginally relevant at best. An interesting (although disturbing) experiment would be to videotape your day, filming all the conversations, mail, e-mail, meetings, newspapers read, TV watched, and so forth. Then study the tape and see what percentage of that information you really need to do your job well. You’d have to do this with some sophistication because, for example, a seemingly irrelevant short conversation might be important because it builds a relationship with someone upon whom you depend. But still, the results of the experiment would be clear. You are hit daily with a fire hose blast of information, only a fraction of which is required to be an excellent employee. Believe it or not, “a fraction” could mean 1 percent. With clogged channels, even if someone is emotionally predisposed to want to understand a change vision, the information can become lost in the immense clutter.

Part of the solution has to be removing some of the clutter.

My Portal

From Fred Woods

One of the largest obstacles preventing meaningful change in our company is our inability to get important messages to our 120,000 employees. Our people get masses of communication, coming from all different areas. First there’s a message about your 401k. Then there is a memo from your supervisor. Then there is a message from our IT director about internal information security. Then maybe a brochure from a political action committee trying to raise money. All this arrives first thing in the morning, every morning. Sometimes I think people just get paralyzed and don’t read any of it.

When I travel with Doug, our CEO, he’ll inevitably get a question from an employee during a town hall meeting saying, “I didn’t know about such-and-such,” or “Why don’t we talk more about blah, blah, blah?” And Doug’s response is always, “There was a story in Barron’s last week that was just about that” or “We talked about that three times in our staff meeting last month.” Doug will then glare at me because he apparently feels I’m not doing my communications staff job. He thinks I’m not getting this information to them. But we are getting the information to employees. They just don’t remember it because even if they read it ten days ago, they’ve had so much information since then they’ve forgotten. Or they got a huge pile and were paralyzed because they knew that in fifteen minutes six customers were going to be in front of them, so they dumped the whole pile in the wastebasket. We’re in the process of trying to change this.

Leadership needs to hold the primary responsibility for communication. There is no question there. It can’t be assigned to a communications staff. But we can help them by clearing the channels. That’s what we’re now focused on.

We’ve looked at the nature of the communication that flows to employees. What we found was that 80 percent of what they got every day was being pushed out to them. They didn’t ask for it, and they probably didn’t need it. They just got it, like it or not.

To tackle this problem, we’ve taken a lesson from Yahoo.com. We are in the process of developing an employee Web site where we push out information every day for our employees. Using the My Yahoo! idea, we have started to develop what we are calling My Portal, which will let employees tailor the information they see on their desktop. From all the more routine stuff—and that’s what I am talking about, the routine stuff—employees can get information concerning their specific needs in the workplace. And just that information—nothing more unless they want more. They’ll get information that is easy for them to understand, information that they either act upon that day or can put away until they need it.

Once it’s up and running, My Portal will be a huge step in lightening the flood of routine communication landing on employees and make it easier for us to get the big, important, nonroutine messages out. We don’t have precise measures, but all the initial feedback we have says people are very excited about the potential of getting much less irrelevant stuff and designing a tool that will allow them to better understand the important issues. Not only will My Portal help the firm, I think people will really appreciate our efforts to lighten their load.

“My Portal” is far from a panacea. But it’s an interesting use of new technologies to reduce the information clutter. It will run into resistance. “What?” says the marketing, personnel, or finance bureaucrat, “Everyone must know this information about X. It must be sent to them!” You have to deal with situations like this, where people cling to the old ways of communicating. But remember, without a clear channel, you can’t influence feelings and create needed behavior.

The unclogging concept is a good one and can be applied in many places. With today’s technology, why should everyone get the same company newspaper crammed mostly with information of low relevance? We already know that instead of receiving 100 pages of your local city’s newspaper, you can get 2 pages from the Internet each day on topics of relevance to your life. If that’s possible, why not in an organization? In a similar vein, why should large numbers of people be stuck in meetings of marginal importance? We all hate this. It adds to information overload (and to our anger). All this was a problem in a slowly changing world. With a much faster-paced world, the problem grows greatly.

Matching Words and Deeds

People in change-successful enterprises do a much better job than most in eliminating the destructive gap between words and deeds.

Deeds speak volumes. When you say one thing and then do another, cynical feelings can grow exponentially. Conversely, walking the talk can be most powerful. You say that the whole culture is going to change to be more participatory, and then for the first time ever you change the annual management meeting so that participants have real conversations, not endless talking heads with short, trivial Q&A periods. You speak of a vision of innovation, and then turn the people who come up with good new ideas into heroes. You talk globalization and immediately appoint two foreigners to senior management. You emphasize cost cutting and start with eliminating the extravagance surrounding the executive staff.

Nuking the Executive Floor

From Laura Tennison

When we presented our vision of the future, I thought we were getting acceptance, and some enthusiasm. But then I began hearing that a few employees thought it was outrageous that we talked about being a low-cost producer while our executive offices were so grand. They said, in effect, “How can you be serious about improving productivity when you are wasting so many resources maintaining such an elaborate executive area?” In my judgment, they were right. And the more they talked, the more other people began to think the same thing.

The executive floor in our headquarters building was a world unto itself. The rooms were huge. The joke was that you could play a half-court basketball game in the chairman’s office. Almost every office included an adjoining conference room and private bath. Many of the bathrooms had showers. There was enough polished wood all around to build a very nice ship. There was a private express elevator going to that floor. There was an elaborate security system that required a staff of at least four people. There was expensive art on the walls. It was incredible.

All of this had some reason for being. We once didn’t pay that well, and the offices were a big part of the attraction for wanting to be in top management. Big clients once upon a time often judged whether they should do business with us by the prosperity (or lack thereof) shown in the executive area. The security was put in after some unpleasant incidents in the 1970s.

We had discussions about how to deal with the problem. We could take out the bathrooms except the one in the chairman’s office. Maybe we could turn a few of the conference rooms into offices. Or maybe take the most expensive art and give it on loan to the museum. But the discussions went nowhere. “These ideas will cost more money. We’re trying to save money.” “We’ve got big competitive issues, why are we worrying about furniture?”

Two years ago we got a new CEO. I remember wondering if he would do anything about the executive offices. I didn’t have to wonder long.

Almost immediately after taking the job he nuked the entire floor. We tore everything down to the outside walls and rebuilt. People were relocated on another floor while the construction was in process. Offices were reduced in size. The bathrooms disappeared. We put in plenty of conference rooms, but not one per office. The new décor is lighter, looks more contemporary, and was not nearly as expensive as the old mahogany. We added more technology and reduced the number of secretaries. We converted the express elevator to a local one, used by all. We sold the art. We also made the security less noticeable and less labor intensive.

I think just the announcement that we were going to do all this had a powerful effect. When people saw the end result, and lived with it every time they visited that floor, the effect built. You can’t believe how different the executive area looked and felt. The rich men’s club was completely gone.

The one criticism of this was that all the construction was an additional expense. But we could show that by adding offices, reducing secretaries, selling art, reducing security costs, making it easier for employees to move around the building (because of the freed-up elevator), we could pay for the changes in twenty-four months, and after that operating costs would be significantly lower. I’m not sure how many people know that, or care much. They just care that the executives seem to be better at walking the talk.

For at least three reasons, matching words and deeds is usually tough, even for a dedicated guiding team. First, you sometimes don’t even notice the mismatch. “What does the size of the offices have to with the real issues: duplication of effort, too many levels of bureaucracy, a sloppy procurement process?” Second, you see the mismatch but underestimate its importance and then spend too little time seeking a solution. “Redoing the floor will cost more money. There is no way to get around that reality.” Third, you see the answer but don’t like it (a smaller office, no bathroom!).

In highly successful change efforts, members of the guiding team help each other with this problem. At the end of their meetings, they might ask, “Have our actions in the past week been consistent with the change vision?” When the answer is no, as it almost always is, they go on to ask, “What do we do now and how can we avoid the same mistake in the future?” With a sense of urgency, an emotional commitment to others on the guiding team, and a deep belief in the vision, change leaders will make personal sacrifices.

Honest communication can help greatly with all but the most cynical of employees. The guiding team says, “We too are being asked to change. We, like you, won’t get it right immediately. That means there will be seeming inconsistencies between what we say and do. We need your help and support, just as we will do everything to give you our help and support.”

By and large, people love honesty. It makes them feel safer. They often love honesty even when the message is not necessarily what they would most like to hear.

New Technologies

Great vision communication usually means heartfelt messages are coming from real human beings. But new technologies, as cold and inhuman as they are, can offer useful channels for sending information. These channels include satellite broadcasts, teleconferencing, Webcasts, and e-mail.

Although a satellite picture of the boss is not the same as having him in the same room, it can be a lot better than a memo. Even a videotaped interaction with the boss and some employees can show others more than information on paper.

New technology can solve communication problems very creatively. For example, one problem is that messages come and go. The president is in the room, but then she leaves. The memo is good, but it eventually goes in the trash. So what doesn’t leave the room? What could stay day and night, beaming a message on and on?

The Screen Saver

From Ken Moran

There was no set screen saver before we introduced this. Everyone chose their own—some sort of wallpaper, something they downloaded from the Internet. Your normal morning went something like this: You walk into the office, get your coffee, greet your coworkers, go to your desk, log on to the computer . . . and your day begins. Now imagine walking in, getting your coffee, greeting friends, logging on, and discovering that something is different. You take a closer look at your computer screen and realize that the picture of fish that usually greets you every morning has been replaced with a multicolored map of the UK surrounded by a bright blue circle. As the image slowly moves around your screen, you read the words surrounding the circle: “We will be #1 in the UK market by 2001.” This was exactly the image we presented to all employees one morning about two years ago.

Because the screen savers appeared on all computers the same morning, we surprised everyone. We had recently announced our new vision, so the concept wasn’t new. The point was not to introduce the vision in this way, but to show our commitment to it and to keep it fresh in people’s minds. The aspiration to become number one is pretty infinite. We wanted people to know that this was not just another fad, or just a warm and fuzzy hope. This was an absolute, a constant. By putting the message on people’s computers so that they saw the logo every time they logged on, we found a simple way to continually reinforce our message.

Needless to say, the arrival of the screen savers had everyone talking. That day, you’d hear people in the halls saying, “The strangest thing happened when I logged on this morning . . . Oh, you got one of those new screen savers too? Did everyone get one? What’s this all about?” Over the next few weeks, the conversation moved toward “Do you think we can become number one by 2001?” At a later department meeting, they might talk about new metrics: having five new products in the UK by 2001, growing at a rate of at least 15 percent a year, and being number one in sales each year. “If we hit those targets,” people said, “I think we’ll definitely achieve the vision.”

Of course there were the skeptics who didn’t appreciate the fact that we had removed “their” screen saver. They probably felt like we were forcing this down their throats. On the day the screen savers arrived, their conversations were more like, “How dare they change my computer! What happened to my old screen saver?” These were the people who had a problem accepting the fact that they would have to change, so it wasn’t really the screen saver that was the issue. These were the people who wanted to ignore our new vision, to write it off as just another fad and wait for the initiative to go away. The new screen saver and the conversations it sparked, on top of all the other communications circulating around the company, made it very difficult to ignore our vision.

After a while, we updated the computer image to include other metrics. We still had the UK map surrounded in the blue circle, but we changed the message around it. This sparked new conversations about our goals and our vision. I could walk around the office and ask people what last year’s results were and what this year’s target was and many could respond without even having to think about it. These were people that, a year before, might not have even been able to quote the company’s vision, let alone its targets.

We continued to update the screen saver, and it’s become a sort of corporate icon around here. It’s great because, instead of a newsletter or flyer that’s here today and gone tomorrow, it is a constant reminder of our company’s goals. It’s amazing what can happen if large numbers of us all understand what the goals are.

Done poorly, a new and unexpected screen saver could seem like Big Brother in the most Orwellian sense. But look what they were able to do here.

An Exercise That Might Help

The goal is to assess accurately how well those around you understand and have bought into a change vision and strategies.

Method 1

Find a group of individuals who employees see as “safe.” Perhaps Human Resource people who have good relations with the workforce or consultants who swear confidentiality and look credible. Have them talk to a representative sample of employees in your organizational unit (always focus where you have influence). The questions are: “We need to know how well we have communicated the change vision and strategies. What is your understanding? Are they sensible? Do they seem compelling? Do you (really) want to help?” The interviewers can aggregate the information without naming names and give it to you. This need not be expensive, even in a large organization. That’s the beauty of sampling.

Method 2

If your enterprise already polls employees each year with an “attitude study” or the like, add some items related to the communication issue. “Do you understand the change vision? Do you buy into it?” This method is very cheap and easy, but you must wait until the yearly cycle.

Method 3

Construct a special questionnaire and send it to employees. You can ask more questions than in method 2, and do it when you want, but it will cost more and draw more attention. More attention is both good and bad. If you are feeling fragile and risk averse, for whatever reasons, forget it.

Method 4

Just talk to people informally about the issues. Listen to the words, yes, but also pay attention to the underlying feelings.

The visual image is an important part of this method. People read, yes, but they also see, with all the power of seeing. Other new technologies offer similar benefits. The satellite broadcasts a moving picture. The teleconference with an executive people know sends more than voice—an audience can conjure up an image in their minds. A video over the intranet is like the satellite broadcast. We will be seeing increasing video over the Internet, even though the words could come much cheaper as text.

As with the issue of urgency (step 1), none of these methods are remotely sufficient by themselves. You generate a gut-level buy-in with Webcasts and a screen saver in conjunction with well-prepared Q&A sessions, new architecture, and more. At times, you might think all the communication absorbs an inordinate amount of time and resources. But it’s all relative. If we have been raised in an era of incremental change, with little vision and strategy communication required, then what is needed now can seem, quite logically, like a burden. Yet most of the burden is in up-to-speed costs. Learn new skills, unclog the channels, add the new technology, and it is no longer a tall mountain to climb. It becomes just another part of organizational life that helps create a great future.

Step 4

Communicate for Buy-In

Communicate change visions and strategies effectively so as to create both understanding and a gut-level buy-in.

What Works

• Keeping communication simple and heartfelt, not complex and technocratic

• Doing your homework before communicating, especially to understand what people are feeling

• Speaking to anxieties, confusion, anger, and distrust

• Ridding communication channels of junk so that important messages can go through

• Using new technologies to help people see the vision (intranet, satellites, etc.)

What Does Not Work

• Undercommunicating, which happens all the time

• Speaking as though you are only transferring information

• Accidentally fostering cynicism by not walking the talk

Stories to Remember

• Preparing for Q&A

• My Portal

• Nuking the Executive Floor

• The Screen Saver

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FXja0RfjQt4&feature=youtu.be