Hi I need help with filling out the Consulting tables based on the case study.

![]()

.

9B18M110

TVO: LEADING TRANSFORMATIONAL CHANGE (A)

R. Chandrasekhar wrote this case under the supervision of Professors Gerard Seijts and Jean-Louis Schaan solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality.

This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) [email protected]; www.iveycases.com.

Copyright © 2018, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2018-11-21

In July 2013, Lisa de Wilde was reviewing a report that just landed on her desk. The report had been prepared by consultants hired by de Wilde, the chief executive officer (CEO) of TVOntario (TVO), an educational media organization under the aegis of the Ontario Ministry of Education, in Canada. The consultants had outlined a five-year strategic plan aimed at igniting growth in TVO’s revenues.

TVO was originally created in 1970, as the technological extension of the public education system, at a time when technology meant television. TVO’s mandate was rooted in supporting the ministry’s social role of providing education—a crucial public good—to Ontarians of all ages. Over time, the mandate was broadened to include current affairs, documentary, and drama programming. But unlike its private-sector peers in the television industry who relied on commercial advertisements as a source of revenue, TVO depended on annual grants from the ministry of education to the extent of 66 per cent of its annual expenditure. For the rest, it relied on donors and on its own revenue-generating programs.

At the end of the 2012/13 broadcast year, TVO reached 83 per cent of Ontarians. However, new data showed that early adopters to Internet video were beginning to watch as much as 45 per cent of their television through non-traditional channels. These findings and other market conditions suggested three triggers for developing a five-year strategic plan.

The first trigger was the fact that if TVO could properly harness technology advances, it could strengthen its value proposition. Like in many industries, technological advances were causing massive disruption. For TVO, this disruption was manifested in learning. New openings were emerging around technology in the classroom and media, especially in journalism, which was being reshaped by social media and collapsing advertising-based business models.

The second trigger was a change in official policy, announced in March 2012, pertaining to government grants to public agencies. The provincial government had announced that TVO, like other public agencies, should reduce its dependence on government grants. The reduction had become necessary because the provincial government’s annual budget had shown a deficit of CA$15.3 billion1for the year ending March 2012. The deficit for the year ending March 2013 had also been forecast to prevail at the

1 All currency amounts are in Canadian dollars unless otherwise specified.

same level.2 Since pruning the deficit had become a priority for the government, there would be no increases in funding for TVO and, starting in 2014, TVO would see a cutback of over 5 per cent in its annual grant. In contrast to 2011, when the ministry of education had enhanced its annual grant to TVO by 16.2 per cent (from $37.6 million to $43.4 million), the grant would come down in 2014 by 7.8 per cent (from $43.4 million to $40.0 million).3

The third trigger was the fact that the net revenue from donors (individual and corporate) was declining— from $3.21 million in 2009 to $1.95 million in 2013. The need for self-generated revenues was urgent. It had placed TVO on the offensive.

Together, these three triggers provided the burning platform for the organizational transformation at TVO.

In accordance with the new imperatives, TVO had already made tough calls in the short term that created pain for different employee groups. For example, it reduced its operating expenditure by 5 per cent of the provincial operating grant. It discontinued three legacy programs—Big Ideas, which focused on contemporary intellectual culture; Saturday Night at the Movies, a weekly feature; and In Conversation with Allan Gregg, a weekly interview series that aired on Fridays with authors and artists. TVO also closed its Ottawa bureau and announced that it would let go 35 employees—nearly 10 per cent of its total workforce—by March 2014, when the financial year would end.

For the long term, de Wilde had to develop a strategy that would enhance TVO’s financial sustainability by increasing self-generated revenues and take it into a new growth orbit. That was her reason for hiring consultants in February 2013, as she explained:

There is a sense of urgency in moving forward. We must fundamentally transform ourselves as an organization. We have been good, traditionally, at educational broadcasting, journalism, kids programming series, and documentaries. For decades, we have been a “nice to have” television channel. We should now take action to position ourselves as a “must have” educational and journalistic service for Ontario citizens. The big picture I have is to enlarge our audience, hitherto outside the classroom, to those inside the classroom. Our programs should be more focused and their content should be rigorous. I envision a cultural change for the organization: We have to get out into the open and prove our value. And, yes, we should think about metrics. Accountability is crucial.

The brief de Wilde delivered to the consultancy firm asked for a strategic plan that would deliver four specific objectives: re-envision TVO around technology in the classroom; make TVO financially sound; empower TVO employees to generate value; and create greater impact for Ontarians.

LISA DE WILDE

In September 2005, de Wilde joined TVO as CEO, when the roles of chair of the board and CEO, which had been combined since TVO’s inception, were separated. Prior to joining TVO, de Wilde was president and CEO of Astral Television Networks, a subsidiary of Astral Media Inc., which was the largest

2 Sébastien Lavoie, Assistant Chief Economist, LBS Economic Research: Provincial Budget, March 27, 2012, accessed March 10, 2017, https://cebl.vmbl.ca/Economics/9/Ontario_Budget%202012_e.pdf.

3 TVO, Ontario Education Communications Authority, Annual Report 2011–2012, accessed December 20, 2017,

https://tvo.org/sites/default/files/media-library/About-TVO/Annual-Reports/TVO-Annual-Report-2011-12-English.pdf; TVO, Ontario Education Communications Authority, Annual Report 2013–2014, accessed December 20, 2017, https://tvo.org/sites/default/files/media-library/About-TVO/Annual-Reports/TVO_AnnualReport_2013-14_English_AODA.pdf.

broadcaster in Canada with 84 radio stations in eight provinces. It was also a major player in premium and specialty television at the time, until its sale to Bell Canada Enterprises Inc. in June 2013.

With bachelor’s degrees in arts and law from McGill University, de Wilde had worked as a lawyer for seven years with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, the industry regulator, before moving into the corporate sector. Upon joining TVO, de Wilde was thereby armed with a 360-degree view of the Canadian broadcasting industry.

The first thing that struck de Wilde was that TVO had no digital infrastructure, which was essential for operating in an increasingly digital world. TVO had been an analog broadcaster for over four decades. Analog broadcasting was characterized by the transmission of audio and video signals through airwaves (such as radio broadcasting) resulting in low-quality sound and picture. Within four years, de Wilde had taken TVO into the digital world, making over $10 million in investments during that period, thanks in part to a one-time special capital expenditure funding, to build an end-to-end digital content production and management workflow. In August 2012, TVO switched fully to digital transmission, along with its peers in the Canadian television broadcasting industry.4

Digital broadcasting was characterized by high-quality sound and picture. Audio and video signals were transmitted through electromagnetic media (like micro waves). Going digital also meant lower distribution costs and higher economies of scale for TVO. It could finally create content and manage it, all in a digital format. Simultaneously, de Wilde also ensured that TVO was focused on developing more public education programs. This focus was in contrast to the pursuit of local news and entertainment programs by other television channels.

TVO was driven by addressing market failure—providing services that were essential to a prosperous and democratic society but not sustainable as a private sector business model. This gave TVO a purity-of- mission. Its children’s programming, journalism, and documentaries all answered to the highest standards of education and journalism, while not selling advertising. TVO’s businesses comprised two main areas. The first area was responsible for television and media, and included current affairs, documentaries, and children and parent programming. The second area was responsible for educational services, such as the Independent Learning Centre (ILC), and support for learners, such as the Homework Help program.

Commenting on her personal style of leadership, de Wilde explained her focus:

Leadership is all about providing clarity of purpose, giving people reasons to believe that they are making a difference and just letting them do it their way, while making sure that, by and large, they stay the course. At a personal level, I work hard, am driven, and do well in an environment marked by high level of complexity and change. That’s why I like my role at TVO. I’m critical, of myself and I am always asking: “What could have been done better?” or “How can I fine-tune what has been done?” I am also resilient, always optimizing and course correcting. I also have a high sense of urgency. Tomorrow is too late for me. I like the puzzle of figuring things out. I’m not a technologist, but I get satisfaction from leveraging technology for the common good. What we are doing at TVO is important.

TVO was in the midst of introducing further innovations in its programming when de Wilde had a burning platform on her hands.

4 “CBC-TV, TVO End Analog Transmission,” CBC News, August 1, 2012, accessed March 27, 2017, www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/cbc-tv-tvo-end-analog-transmission-1.1145615.

CANADIAN BROADCASTING INDUSTRY

The Canadian broadcasting industry had revenues of $17.1 billion in 2013 (see Exhibit 1). The industry consisted of three segments: radio, which generated 9 per cent of revenues; television, which generated 38 per cent of revenues; and broadcasting distribution undertakings (BDU), which generated 53 per cent of revenues. The five largest radio companies held over 68 per cent of that segment, and consisted of BCE, Corus Entertainment (Corus), Rogers Communications Inc. (Rogers), Newfoundland Capital Corporation, and Cogeco Connexion (Cogeco). Similarly, the five largest television broadcasters held 74 per cent of that segment, and consisted of BCE, Shaw Communications Inc. (Shaw), Rogers, Corus, and Quebecor Inc. Also, the five largest distributors held 86 per cent of the BDU segment, and consisted of BCE, Cogeco, Rogers, Shaw, and Vidéotron.5

The television broadcasting segment (including cable, specialty services, and pay television) consisted of enterprises that largely acquired programming from foreign markets, licensed programming from Canadian independent producers, created some in-house programming (mostly news), and delivered it to viewers. The segment employed about 60,000 people. Canadians had access to over 700 cable channels. Approximately 12 million Canadian homes had a cable or satellite television subscription. TVO was delivered into every one of these homes in Ontario. One in three Canadians watched television over the Internet through services such as Netflix Inc. In 2013, one in 20 Canadians watched Internet television on a tablet or smartphone.6Kids were adapting to these technologies at a rapid pace.

The Canadian broadcasting industry had undergone a transformation over the previous 30 years through the rise of cable channels, which drew viewership away from conventional television channels (i.e., over-the-air broadcasting). Although consumers continued to seek television programming, the industry was facing disruption on an even greater scale, brought on by the rise of global streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon. Consumption was shifting to new platforms, particularly among the young. Since the industry had long operated under a distinct territorial market for Canadian rights, the shift to a global market was potentially catastrophic, given Canada’s small domestic market. Clearly, the Canadian broadcasting industry would soon be engaged in an existential fight for survival. Disruption was also causing similar ripples in the advertising industry, a key source of revenue for the television industry. Change was also present in the regulatory framework that had long supported the Canadian broadcasting industry.

ONTARIO EDUCATION SECTOR

The education space in Ontario was also experiencing a period of disruption. The changing job market brought on by globalization, technology, and the knowledge economy was driving a focus on 21st- century learning competencies to equip students for the current and future job market. There were also advances in pedagogy. Differentiated learning and student supports were moving away from traditional generic models to customized approaches. Silicon Valley’s obsession with the so-called “edutainment” segment resulted in the flow of investment moving toward education-based start-ups. It was like the early days of the web or mobile. The Ontario Ministry of Education was attempting to crystalize all of this change in a strategy it called Achieving Excellence, which made the opportunity implied by TVO’s new strategic direction of technology in the classroom all the more germane.

5 “Communications Monitoring Report 2014: Broadcasting System,” Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, accessed September 10, 2016, www.crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/policymonitoring/2014/cmr4.htm.

6 Ibid.

TVO COMPANY BACKGROUND

TVO was set up in June 1970 by the provincial government of Ontario with a mandate to leverage the technology of television, which was new at the time, to support public education. It had revenues of

$66.97 million for the year ending March 2013 (see Exhibit 2). Unlike the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, which was started as a radio network by the federal government in 1936 and carried commercials as a source of revenue, TVO derived its funding solely from government grants and individual donors or sponsors. Its advertisement-free model of programming and distribution of content was similar to the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. Founded in 1969 as a non- profit, PBS referred to itself as “America’s largest classroom.” PBS programming was watched by 82 per cent of all U.S. television households, and the broadcaster claimed to treat its audience as citizens, not simply consumers.7 The TVO prototype was later emulated by provincial educational broadcasters Knowledge Network in British Columbia, and Télévision française de l’Ontario, the French language network in Ontario. The PBS or TVO model gave broadcasters freedom to develop content without being influenced by advertisers.

TVO’s vision was to “empower people to be engaged citizens of Ontario through educational media.” Its mission was to serve as “Ontario’s public educational media organization and a trusted source of interactive educational content that informs, inspires, and stimulates curiosity and thought.” Toward this end, it organized its products and services into 13 offerings aimed at specific audience segments (see Exhibit 3). The largest of these sections were children and online programming, with a budget of about 30 per cent, and the ILC with about 22 per cent. This was followed by documentaries and prime time programming, with approximately 18 per cent of budget. Current affairs programs, including The Agenda, had a budget of about 16 per cent, and the Homework Help program’s budget was about 14 per cent.

TVO had triggered the financing of children and documentary programs from independent producers in the province of Ontario, valued at $25 million in total production budgets each year, leveraging tax credits and Canada Media Fund grants. The producers had, in turn, generated more than 300 industry jobs.8The channel commissioned more original point-of-view documentaries than any other Canadian broadcaster. Its content generated over 17 million video streams and downloads in 2013.9

The Agenda, hosted by Steve Paikin, was one of TVO’s most popular programs. It was known for its in- depth current affairs analysis. It ranked first among Ontarians for news and current affairs broadcasts in its timeslot of 8:00 p.m. on weekdays. It received 2.2 million downloads, streams or podcasts in 2012, with the microsite receiving more than 1 million page views.10

In describing the TVO audience for its current affairs programming, de Wilde expressed some concerns:

The typical customer for our current affairs TV programming is older, at 55+ years. One of our challenges is to drive a younger audience, aged 35–54, to our programming and making content accessible in smaller pieces in a bid to engage a younger audience. A major attribute of the younger audience is its demand for short-form content. That attribute defines what we should do.

7 “Overview,” Public Broadcasting Corporation (PBS), accessed March 13, 2017, www.pbs.org/about/about-pbs/overview.

8 Canadian Heritage, Evaluation of the Canadian Media Fund 2010-2011 to 2013-2014, Evaluation Services Directorate, July 9, 2015, accessed December 20, 2017, https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pch/documents/corporate/publications/evaluations/cmf-

2010-2014-eng.pdf; Because CMF funding creates 26,150 jobs per year, and TVO’s envelope represents approximately 1 per cent of the fund in 2012-2013, TVO’s share would represent about 300 jobs per year.

9 “TVO Announces Plan that Looks to Future,” Cision, November 13, 2012, accessed December 20, 2017, www.newswire.ca/news-releases/tvo-announces-plan-that-looks-to-future-511145061.html.

10 Ibid.

TVO PROGRAMMING

Independent Learning Centre

The ILC was founded in 1926, when the Ontario Department of Education established a correspondence courses program to provide elementary education for children living in isolated areas of northern Ontario. It was transferred in April 2002 to TVO. Its students consisted of three categories: those seeking to earn secondary school credits and gain an Ontario Secondary School Diploma; those getting their high school equivalency credentials by writing the General Educational Development tests; and those seeking to upgrade their skills for employment, apprenticeship, or post-secondary entry. The ILC not only offered its courses directly to students in the province of Ontario, it also made them available as credit courses to other educational institutions in the province for a fee.

The ILC had a continuous intake, with more than 20,000 students at any time. Its highest demand courses were senior-level English, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and physics. Students were drawn to the ILC because it offered a flexible self-learning model, enabling them to study where, how, and when they wanted.

Homework Help

The Homework Help program was a free and personalized online resource in mathematics for students in grades 7 to 10, with live, one-on-one tutoring provided by Ontario-certified teachers. It was started in 2009 as a pilot in one school district but had since grown province-wide. One of its attractions was that its past sessions provided a library of math resources for students, available on-demand around the clock as well as in the classrooms.

TVOKids

TVOKids was aimed at preparing young children (ages 2 to 11) for both school and life. It showed them ways of doing well in school, enhancing their social competencies, and of acquiring skills required to succeed beyond school years. Its programs, including Odd Squad, Hi Opie!, and Annedroids, were known to ignite a child’s love of learning. They were available on-demand, on the platform of a parent’s choice—desktop, tablet, or mobile—and at the time of their choosing. Its strategy was to focus outside the classroom.

Research conducted by the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education showed that TVOKids offered more educational applications than any other Canadian broadcaster, and that its digital resources improved literacy and numeracy skills among the target audience.

TVO was poised to play an important role at the intersection of technology, Ontario curriculum, and pedagogy. Its educational mandate had two components that gave it an edge: sparking an interest among children in science and mathematics, so that they could go on to seek careers that would help drive the Canadian economy; and providing high quality educational experiences. Its biggest strengths were in educational media (exemplified by TVOKids and ILC) and current affairs (exemplified by The Agenda).

According to de Wilde, these programs offered a great opportunity:

Revenues in an organization like TVO have to be the caboose on the train. So, instead of wondering, “How do we make a buck from our TV programs?” we will ask: “What assets in our

current portfolio can we monetize?” For example, we have high school credit courses. If we can figure out a way to get permission from the ministry of education to not only provide the courses but also offer diplomas, they could become valuable revenue generating assets. We can also take them to educational markets beyond Canada. It is a huge opportunity.

ISSUES BEFORE DE WILDE

The report from the consultancy firm, currently before de Wilde, had been preceded by extensive groundwork on the part of the firm over a period of six months. The consultants had carried out one-on- one interviews with TVO board directors, run a workshop with members of its executive management committee, conducted an organization-wide employee survey, held interactions with key stakeholders, and reviewed the prevailing best practices in digital education.

The firm had suggested a combination of three strategic directions for TVO. First, TVO should grow its role as Ontario’s delivery and innovation partner for digital education inside the classroom, outside the classroom, and abroad. Second, TVO should leverage its brand of in-depth current affairs from an Ontario perspective to increase overall citizen engagement. Third, TVO should empower its employees to deliver its strategy and to thrive in an organization embracing continual change.

It meant that TVO should scale back its television focus and pivot towards education by going inside the classrooms, rather than staying outside. The firm also suggested that TVO should begin to address the needs of other government ministries, in addition to the ministry of education, so that all digital education initiatives in the province could be consolidated under its fold. This included the Ontario Ministry of Training Colleges and Universities, which was providing funding for third parties to deliver digital education programs; the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, which was investing in programs such as the Ontario Centres of Excellence; and the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, which was financing various settlement services.11

As part of executing the strategy, de Wilde had to take a fresh look at the products and services TVO provided and decide which of these to hold on to, which to discontinue, which to monetize, and which to grow. The call would be critical to the larger decision about allocating scarce resources. However, the concept of product management, involving autonomy and decentralization, was new to TVO.

The Ivey Business School and the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Bill and Kathleen Troost in the development of this case.

11 StrategyCorp Business Strategies Group, A New Agenda: A Strategic Plan for TVO, Consolidated Final Report, July 15, 2013.

EXHIBIT 1: CANADIAN BROADCASTING INDUSTRY REVENUES 2009–2013 (IN CA$ MILLION)

| Segment | Sub-segment | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

| Radio | AM | 306 | 307 | 311 | 306 | 295 | ||||

| FM | 1,202 | 1,245 | 1,302 | 1,314 | 1,328 | |||||

| Subtotal | 1,508 | 1,552 | 1,613 | 1,620 | 1,623 | |||||

| TV | CBC conventional TV | 392 | 450 | 500 | 508 | 464 | ||||

| Private conventional TV | 1,971 | 2,142 | 2,144 | 2,038 | 1,944 | |||||

| Pay-per-view and others | 3,121 | 3,475 | 3,748 | 3,968 | 4,091 | |||||

| Subtotal | 5,484 | 6,067 | 6,392 | 6,514 | 6,499 | |||||

| Broadcasting Distribution Undertakings (BDU) | Cable and IPTV | 5,123 | 5,610 | 5,927 | 6,068 | 6,321 | ||||

| DTH/MDS undertakings | 2,196 | 2,385 | 2,532 | 2,492 | 2,472 | |||||

| Non-reporting BDUs | 123 | 134 | 127 | 196 | 196 | |||||

| Subtotal | 7,441 | 8,130 | 8,586 | 8,757 | 8,990 | |||||

| Total | 14,432 | 15,749 | 16,591 | 16,891 | 17,111 | |||||

Note: TV = television; CBC = Canadian Broadcasting Corporation; IPTV = Internet Protocol television; DTH = direct-to- home; MDS = multipoint distribution system

Source: “Communications Monitoring Report 2014: Broadcasting System,” Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, accessed September 10, 2016, www.crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/PolicyMonitoring/2014/cmr4.htm.

EXHIBIT 2: TVO INCOME AND EXPENDITURE STATEMENT (IN CA$ MILLION)

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Revenues | |||||

| Government operating grants | 38,887 | 37,640 | 43,376 | 42,908 | 43,069 |

| Independent Learning Centre | 9,068 | 9,984 | 11,040 | 12,143 | 12,964 |

| Self-generated revenue | 9,563 | 7,419 | 7,290 | 7,529 | 7,443 |

| Government and corporate project funding | 2,867 | 1,879 | 534 | 105 | 905 |

| Amortization of deferred capital contributions | 2,625 | 2,633 | 2,266 | 1,999 | 2,526 |

| 63,010 | 59,555 | 64,506 | 64,684 | 66,907 | |

| Expenses | |||||

| Content and programming | 25,397 | 26,260 | 25,949 | 24,150 | 23,634 |

| Technical and production support services | 12,726 | 13,452 | 12,883 | 12,913 | 13,762 |

| Independent Learning Centre | 8,803 | 9,513 | 10,113 | 11,024 | 11,548 |

| Management and general expenses | 6,200 | 6,001 | 5,652 | 5,850 | 6,905 |

| Cost of self-generated revenue | 2,847 | 2,454 | 2,803 | 2,947 | 3,152 |

| Amortization of capital assets | 5,228 | 5,195 | 4,723 | 4,873 | 3,482 |

| Employee future benefits | 2,018 | 2,223 | 2,274 | 4,075 | 4,316 |

| 63,219 | 65,098 | 64,397 | 65,832 | 66,799 | |

| Profit/(Loss) | (209) | (5,543) | 109 | (1,148) | 108 |

Source: Compiled by the authors using the following sources: TVO, Ontario Education Communications Authority, Annual Report 2009–10, accessed December 20, 2017, https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=https%3A%2F%2Ftvo.org%2Fsites%2 Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fmedia-library%2FAbout-TVO%2FAnnual-Reports%2FTVO_AR_09_10_English.pdf; TVO, Ontario Education Communications Authority, Annual Report 2011–2012, accessed December 20, 2017, https://tvo.org/sites/default/files/media-library/About-TVO/Annual-Reports/TVO-Annual-Report-2011-12-English.pdf; TVO, Ontario Education Communications Authority, Annual Report 2013–2014, accessed December 20, 2017, https://tvo.org/sites/default/files/media-library/About-TVO/Annual-Reports/TVO_AnnualReport_2013-14_English_AODA.pdf.

EXHIBIT 3: TVO—PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

| Mandate | Areas of Activity | Products and Services | Delivery Targets |

| K–12 Education | Curriculum Complimentary | Daytime educational programming |

|

| Online |

| ||

| TVOKids educational material |

| ||

| Curriculum Supplementary | Homework Help |

| |

| Independent Learning Centre |

| ||

| Adult Support | Parenting support |

| |

| Teacher support |

| ||

| Citizen Engagement | Current Affairs | The Agenda |

|

| Other programming |

| ||

| Civics and Issues | Civics 101 |

| |

| Partnership with the Perimeter Institute |

| ||

| Documentaries and productions |

| ||

| Research | Investigation | Studies in partnership with the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education |

|

Note: K–12 = kindergarten to grade 12 Source: Company documents.

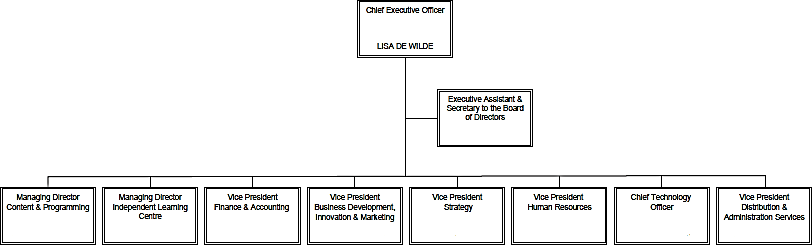

EXHIBIT 4: TVO CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S DIRECT REPORTS JULY 2013

Source: Company documents.