Dress CodeState law does not give students the right to choose their mode of dress. Thus, the matter of student dress and grooming is at the discretion of local school districts. A common question rem

Chapter 3 Education, Religion, and Community Values

Introduction

This chapter discusses one of the most controversial issues school leaders face: the role of religion in the public school. Regardless of personal viewpoint, religious issues elicit strong emotions. There also seems to be very little room for compromise. In addition to community pressure, many teachers, students, school administrators, and school board members have strong beliefs regarding the place of religion in public schools. This chapter addresses some of the legal guidelines regarding religious expression in public schools and presents an ethical model illustrating the importance of effective communication when issues of conflicting interest arise.

Focus Questions

How may school leaders use ethical models to improve communication and decision making?

Are public schools “religion-free” zones?

Should students be allowed to express their religious beliefs at school? Under what circumstances?

Should teachers and other adults express their religious beliefs at school? Under what circumstances?

Key Terms

Discourse ethics

Equal Access Act

Establishment Clause

Forum

Free Exercise Clause

Viewpoint discrimination

Case Study Candy Canes

On Monday before the winter break, Edgewood Elementary School principal Joyce Smith called Flora Norris, Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Education in North Suburban School District. “Dr. Norris,” Joyce began, “It has come to my attention that several third- and fourth-grade students who attend East Unity Church are handing out candy canes to their teachers and classmates. The peppermint candy canes have several religious messages on them. One reads, ‘Jesus is the Reason for the Season.’ The rest have similar messages. All of the candy canes are tied with a green ribbon inviting students and their parents to attend East Unity Church for Christmas Eve services. What should we do?”

Flora thought for a moment. She knew the minister at East Unity quite well. He had a reputation for pushing the envelope when it came to religion and school district policy. “You know the policy, Joyce. Students may hand the candy canes out before school, after school and during lunch, but not in class. Caution your teachers not to allow students to hand out the candy canes in class and not to accept the candy canes from students or comment on them.”

It was not long before the East Unity minister called to state his concerns about students not being able to share their Christian message with other students in their classes. Soon afterwards the school board president called to ask Flora why all of a sudden the district had stopped cooperating with local churches. Sensing a problem, Flora immediately notified the superintendent. After her brief overview of the issue, the superintendent interrupted and stated, “I know. I already have had a call from a couple of board members. Apparently the Reverend enlisted all the elementary students that attend his church to hand out the candy canes. Now he is complaining to school board members about our policy.”

Leadership Perspectives

The case study “Candy Canes” illustrates the conflict generated by the role of religion in public schools. Unfortunately, the controversy has also become one of extremes. At one end of the continuum are those who advocate the promotion of religion (usually their own) in public schools. At the other end of the continuum are those who view public schools as religion-free zones. The stage for this controversy is found in the first 16 words of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The first clause, the Establishment Clause, requires neutrality from government (state legislative bodies, school employees, and school boards) and prohibits public school advancement of religion. The second clause, the Free Exercise Clause, prohibits school officials from interfering with religious expression. The crux of the problem in balancing these two imperatives is this: Enforcing one clause often seems to violate the other. For example, in “Candy Canes,” the Free Exercise Clause clearly establishes the participating students’ right to religious expression. But, at what point does their free exercise violate the Establishment Clause? It is at this point, where one person’s Establishment Clause inhibits another person’s Free Exercise Clause and vice versa, that the seeds of controversy are sown. Part of the problem is that legal scholars, federal judges, and U.S. Supreme Court justices often disagree on when to apply which clause in the context of the public school. Is it permissible for public schools to place restrictions on a grade school student’s religious messages? Does restricting the message send the message that the student’s religious views are not welcome? Is it permissible to hang the Ten Commandments in the hallway of a public high school where the vast majority of teachers and students are Christian? Should it be permissible for student speakers to pray or proselytize during high school graduation ceremonies? These and other questions illustrate the difficulty in balancing the free exercise and establishment clauses. These questions also illustrate the ongoing culture wars over the role of religion in public education.

Steven Waldman, in his excellent book Founding Faith (2008), tells the story of the evolution of the religion clauses in the First Amendment. Much of the following is adapted from his book. In the late 1700s, 11 of the 13 colonies had a state-sponsored religion. Yet Article VI, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution reads, “No religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” It is easy to see why this provision passed without much dissent. The framers of the Constitution were not thinking or contemplating the role of “government” in religion. They were debating the role of “the national government in religion” (Waldman, 2008, p. 131). In other words, the framers were not thinking of state-sponsored religion, but rather thinking about the federal government sponsorship of religion. It is true that many of the framers were very religious men. It is also true that when the framers met for the first time, many of them found themselves in the most religiously diverse group they had ever been in. So, what religion would the national government sponsor? This may be why the U.S. Constitution is a “stunningly secular (document). It does not mention Jesus, God, the Creator, or even Providence. The rights, we are told in the first three words, come from ‘we the people,’ not God the Almighty” (Waldman, 2008, p. 130).

The Bill of Rights, however, was not written by the federal Constitutional Convention, but by the newly created Congress. The Bill of Rights is therefore a product of the “sausage grinder” of debate and political compromise. As one of the primary intellects behind the Bill of Rights, James Madison pushed to give the federal government the power to protect citizens from the “state tyranny” of a sponsored religion, and he argued unsuccessfully to apply the First Amendment to the states. As often happens in politics, Madison ended up completely reversing course and found himself having to convince members of Congress that the beauty of the First Amendment was that it continued to allow state governments to support religion (Waldman, 2008). Thus, the basis for the culture wars over religion and public education rests on a political compromise made more than 200 years ago.

By the 1800s, most states had abandoned sponsorship of a particular religion. However, the controversy continues, and public school leaders often find themselves caught between those who wish to bring religion back into public schools and those who believe that public schools should be religion-free zones. Confronting these challenges requires not only an understanding of the applicable legal concepts, but also an understanding, appreciation, and use of the community’s diverse cultural, social, and religious resources. These challenges may also require

By the 1800s, most states had abandoned sponsorship of a particular religion. However, the controversy continues, and public school leaders often find themselves caught between those who wish to bring religion back into public schools and those who believe that public schools should be religion-free zones. Confronting these challenges requires not only an understanding of the applicable legal concepts, but also an understanding, appreciation, and use of the community’s diverse cultural, social, and religious resources. These challenges may also require the ability to put aside one’s own often deeply held beliefs and seek to understand the perspectives of others. The discourse ethics of Jurgen Habermas can provide guidance.

ISLLC Standard 4B

ISLLC Standards 5B and 5D

Discourse Ethics: Resolving Issues of Conflicting Interests

In the case study “Candy Canes,” Flora Norris is confronted with the conflicting demands of a variety of individuals, which could challenge the skills of even the most experienced school leader. However, the ISLLC standards require that she not only respond legally and decisively to the challenge, but also demonstrate sensitivity and impartiality and respect the rights of others. In other words, Flora’s ethical and legal responsibility is to lead the board of education to “make a conscious choice, rather than permitting the current practice to continue without justification” (Rebore, 2001, p. 242).

ISLLC Standards 5B, 5C, 5D, and 5E

In his book Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action (1990), the contemporary philosopher Jurgen Habermas proposes discourse ethics as a model of communication that may lead to the types of school cultures based on effective communication, collaboration, and mutual agreement outlined in ISLLC Standards 2A, 5B, and 5C. Discourse ethics is not designed to eliminate impartiality of judgment. Rather, it is a model designed to encourage active communication, an understanding of the perspectives of others, empathy, and rational argumentation instead of simply suggesting or imposing a solution on others.

ISLLC Standards 2A, 5B, and 5C

Discourse ethics is premised on active communication. In other words, in the case study “Candy Canes,” Flora Norris cannot assume that she understands the minister’s complaints, the position of several board members, or even Principal Smith’s concerns. To this end, discourse ethics is designed to create opportunities for open discussion and communication that provide a potential for understanding the perspectives of others, mutual agreement, and collective responsibility characteristic of cooperative school cultures. Seeking to understand the perspectives of others does not necessarily mean agreeing with those perspectives. However, seeking to understand serves as the foundation for the empathy necessary for rational arguments, for or against a particular normative practice or policy decision. In short, discourse ethics is a model that promotes the type of understanding necessary for cooperative school cultures characterized by collaboration, mutual agreement, and acceptance, rather than simple enforcement by policy. Reaching understanding, and thus validity, requires an element of unconditional acceptance of the views, needs, and wants of all concerned. It is this unconditional acceptance of the views of others that provides the background for the establishment of the validity of a norm or action rather than the mere de facto acceptance of a practice or action. In other words, what is justified is not necessarily a function of custom (the way things have always been done) but a question of justification.

Discourse Ethics and Cooperative School Culture

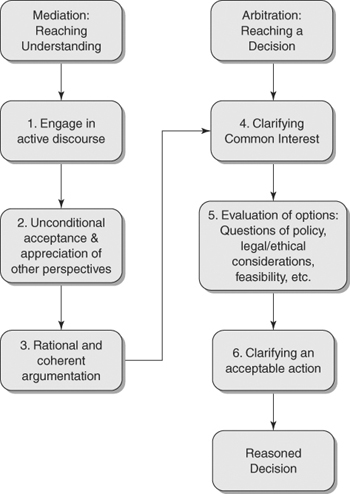

In discussing discourse ethics, Ronald Rebore (2001) makes a distinction between mediation and arbitration that provides guidance in the development of the type of cooperative school cultures called for in ISLLC Standards 2A, 4C, and 4D. Mediation is designed to seek understanding of the perspectives of others in order to facilitate.

ISLLC Standards 2A, 4C, and 4D

FIGURE 3-1 Discourse ethics: Resolving questions of conflicting interests.

Mediation can be viewed as participants striving to reach understanding. Arbitration is designed to give an answer, or in other words, to reach a decision. Arbitration can be viewed in the same way as negotiating a compromise, where the participants try to strike a balance between conflicting interests to reach an equitable solution. The distinction between mediation (seeking to understand) and arbitration (reaching a reasoned decision) can provide a model for school leaders to use when faced with issues of conflicting interest (Figure 3-1).

The case study “Candy Canes” can serve as an illustration of this model. Flora Norris faces several issues of conflicting interest and is charged by her position as assistant superintendent to attempt to lead the board to a conscious choice that is reasonable and justifiable. In this model, Flora’s efforts would begin with mediation.

Step 1: Engage in active discourse. Discourse ethics rest on the assumption that justification of norms or decisions requires real discourse. In other words, Flora Norris cannot assume that she knows the views, claims, and perspectives of all individuals involved. Therefore, she must begin the process by actively seeking and engaging others in verbal communication.

Step 2: Unconditional acceptance and appreciation of the perspectives of others. It is only through appreciating the perspectives of others that true empathy and understanding may occur (Habermas, 1990). Appreciating the perspectives of others does not necessarily mean agreeing with the other’s position. As Ronald Rebore (2001) explains, however, it is only after a school leader has at least a fundamental understanding of the perceptions of others that the leader can begin to form and lead others to reasonable judgments concerning what is right, fair, or just.

Step 3: Rational and coherent argumentation. Rational argumentation results only from the establishment of cooperative relationships. In practical terms, it would be prudent to recognize that some participants may engage in threats, rewards, or manipulation to get their way. However, the normative behaviors of cooperative discourse are fundamental to the justification of policy.

Cases of conflicting interests often require decision making or, in this model, arbitration.

Step 4: Clarifying common interest. The clarification of common interest is not possible without active discourse, the unconditional acceptance of the perspectives of others, and rational argumentation. Reasoned decision making that results in accepted validity also requires consideration of the perspectives of those affected and almost always involves questions of rightness, fairness, and justice.

Step 5: Evaluation of options. Reasoned decision making requires that options address questions of law and policy. Failure to adequately research and consider questions of law and policy creates significant opportunities for erroneous judgments. However, it is important to note that in this model, these considerations commence only after understanding, rational arguments, and clarification of common interest have been attempted.

Step 6: Clarifying acceptable action. An acceptable outcome should meet at least four criteria: (a) it must accomplish the purpose, (b) it must demonstrate a respect for the rights of others, (c) it must be legally and ethically defensible, and (d) it must benefit students and their families.

As Habermas (1990) points out, it is very difficult and often impossible to resolve conflicts of deeply held moral beliefs. “Candy Canes” may be such a case. Failure to reach understanding and at least an acceptable compromise perceived as fair by all concerned is the primary reason some disagreements of conflicting interests are referred to the judicial system in the first place. Consequently, learning to develop and sustain cooperative relationships as outlined in

ISLLC Standards 2A, 4C, 4D, 5B, 5D, and 5E and to appreciate the perspectives of others is a difficult but necessary educational leadership task in a diverse society.

ISLLC Standards 2A, 4C, 4D, 5B, 5D, and 5E

Linking to Practice

Do:

Collaborate with school and community members to develop proactive policies and practices that establish parameters of student religious expression at school. This dialogue may also neutralize some of the criticism that public schools are “antireligion.”

Understand that school cultures become normative. Use the “Resolving Issues of Conflicting Interest” model presented in this chapter (or similar communication model) to develop normative practices of cooperative school cultures.

Train faculty and others (such as a site-based team) in the communication model. Create opportunities to use the communication model in various situations. Begin meetings by sharing guidelines for mediation and arbitration. Make the focus of the meeting clear. Articulate the transition from seeking input, acceptance, and reasonable argumentation and the time for selecting a solution from alternatives.

Know that decisions that lead to conscious choices are often much easier to defend from a legal and ethical point of view than those imposed by a policy-making authority.

Do Not:

Assume that knowledge of law and policy is all a school leader needs to make reasoned and generally accepted decisions.

Public Schools and Religion

There have been thousands of battles similar to the case study “Candy Canes” in local school districts all over the country about the proper role of religion in public schools. Although these battles have ebbed and flowed, Steven Waldman (2008) points to a few “seismic shifts” that stand out, including (1) the Civil War, (2) U.S. Supreme Court rulings that applied the First Amendment to the church–public school battle, and (3) Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species. It is also difficult to argue that the passage of the Equal Access Act in 1984 and the application of forum analysis and viewpoint discrimination to religious expression in public schools have not had a similar impact on the church–public school debate.

The Civil War

At the end of the Civil War, the Northern victors concluded that the basic relationship between the federal government and the states needed to change (Waldman, 2008). Up until this time, the Bill of Rights had applied only to the national government and not to the states. After the war, the Northern victors decided that perhaps James Madison was correct: The Bill of Rights should also apply to state governmental action. The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1866. The purpose of the amendment was to protect citizens by applying the protections of the Bill of Rights to state action. The men who ratified the Fourteenth Amendment most likely did not envision how this amendment would change the dynamic between religion and public schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court and Religion

The U.S. Supreme Court (and federal courts in general) applies strict scrutiny to First Amendment cases. This means that the court does not consider if some religious expression in public schools is permissible, but if there is some compelling reason why it is not permissible. It should also be noted that many—if not most—of the significant Supreme Court cases affecting religion in public schools were brought by religious people (Waldman, 2008). It is through this lens that we view the following summaries of important U.S. Supreme Court cases.

Engel v. Vitale (1962): Held that school officials in New York State could not compose a prayer for students to recite.

Abington Township School District v. Schempp (1963): The Court made it clear that study about religion, as distinguished from espousing or sponsoring religious expression, is constitutional. In other words, teaching about religions objectively or neutrally to educate students about a variety of religious traditions is permissible.

Epperson v. Arkansas (1968): The U.S. Supreme Court invalidated an Arkansas law that forbade the teaching of evolution in public schools.

Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971): The legal question in this case addressed whether or not government aid to religious schools was constitutional. In answering this question, the Court devised a three-pronged test. In order to pass constitutional muster, the governmental action or policy must: (1) have a secular purpose, (2) neither advance nor inhibit religion, and (3) not cause excessive entanglement between government and religion. If the action or policy fails any one of the prongs, then it does not pass constitutional muster.

Stone v. Graham (1980): A Kentucky statute required the posting of a copy of the Ten Commandments, purchased with private contributions, on the wall of each public classroom in the state. The court held that Kentucky’s statute had no secular purpose and was therefore unconstitutional.

Lynch v. Donnelly (1984): The Court considered whether the inclusion of a crèche in the city’s Christmas display violated the Establishment Clause. The court found that the display was not an effort to advocate a particular religious message and had “legitimate secular purposes.” More important to the discussion of religion and education was Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinion, where she established what is referred to as the Endorsement Test. Endorsement is a practice that endorses religion or religious beliefs in a way that indicates to those who agree that they are “favored” insiders. The other side of the coin is the “disapproval” of religion or religious beliefs in a way that indicates that believers are disfavored outsiders.

Aguilar v. Felton (1985): The use of Title I funds to pay salaries of parochial school teachers violated the Establishment Clause.

Wallace v. Jaffree (1985): A 1978 Alabama state law authorized a 1-minute period of silence in all public schools. Over the next few years, this statute evolved to authorize teachers to lead “willing students” in a prescribed prayer. The Court took care to protect the right of students to engage in voluntary prayer during a moment of silence contained in the original legislation, but found the 1982 legislation unconstitutional because of the clear intent to “return voluntary prayer” to the public schools.

Board of Education v. Mergens (1990): The Court found that the Equal Access Act did not violate the Establishment Clause. Schools that have established a limited open forum must allow student-led religious groups the same access to facilities, newspapers, bulletin boards, public address systems, and so forth that is given to other student clubs and activities.

Lee v. Weisman (1992): Prayers at graduation exercises and baccalaureate services have been a long-standing tradition at public schools throughout the United States. A Rhode Island student and her father challenged a school principal’s policy of inviting local clergy to offer an invocation and benediction at graduation. The Court reasoned that high school graduation is of such significance in the lives of many students that the inclusion of prayers at a public school graduation ceremony effectively “coerced” students to participate in religious exercise and resulted in governmental endorsement of religion (coercion test).

Lamb’s Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School District (1993): A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision that found religious speech in public schools to be a fully protected subset of free speech.

Agostini v. Felton (1997): In partially overruling Aguilar v. Felton, the Court found that it was not a violation of the Establishment Clause to use federal Title I funds to allow public school teachers to teach at religious schools. The instructional material must be secular and neutral in nature, and no “excessive entanglement” between religion and public schools was apparent.

Edwards v. Aguillard (1987): The most recent U.S. Supreme Court decision involving teaching of creation science along with evolution involved a Louisiana statute named the Creationism Act. The act forbade the teaching of the theory of evolution in public elementary and secondary schools unless accompanied by instruction in the theory of “creation science.” The act did not require the teaching of either concept unless the other was also taught. The Supreme Court found that the act did not further its stated purpose of “protecting academic freedom” and that it impermissibly endorsed the religious belief that a supernatural being created humankind.

Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000): The U.S. Supreme Court held a Texas District School Board policy allowing student-initiated prayers at football games to be unconstitutional. The policy titled “Prayer at Football Games” limited the message to those deemed “appropriate” by the school administration. The school district argued that students were not required to attend football games and that the student elections served as a “circuit breaker” to state endorsement of religion. However, the majority opinion pointed out that (1) students are subjected to only approved messages broadcast over the school’s public address system, (2) the process does nothing to protect minority views, and (3) many students, such as cheerleaders, band members, and certainly the players, are required to attend. These issues, and the long history in the school district of prayer at athletic events, led the Court to conclude, “The District . . . asks us to pretend that we do not recognize what every Santa Fe High School student understands clearly—that this policy is about prayer.”

Good News Club v. Milford Central School (2001): The Court held that it is viewpoint discrimination when school districts by policy or practice allow non-sectarian groups to use school facilities and disallow religious groups’ equal access. The Court was very careful to point out, however, that not all speech is protected in a limited open forum.

Darwin’s Theory of Evolution

Darwin’s theory of evolution dramatically affected the culture wars in the United States. Rightly or wrongly, many religious people came to fear that the advance of science undermined their faith. Furthermore, many religious people believe that science and secularism have undermined morality and that secularism is at least indirectly responsible for discipline problems, disrespect of authority, and violence in public schools (Waldman, 2008). As a result of Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), there have been several efforts to counter the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools by requiring the addition of a disclaimer in science books. In a recent example, the Tangipahoa Parish School Board (TPSB) in southeastern Louisiana passed a resolution that required teachers to read a disclaimer immediately before the teaching of evolution. This disclaimer, in part, read:

The Scientific Theory of evolution . . . should be presented to inform students of the scientific concept and not intended to influence or dissuade the Biblical version of Creation. . . . It is further recognized . . . that it is the basic right and privilege of each student to form his/her own opinion and maintain beliefs taught by parents. . . . Students are urged to exercise critical thinking.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a district court ruling that this disclaimer violated the Establishment Clause (Freiler v. Tangipahoa Parish Board of Education, 1999). In applying the coercion test, the court found the board’s disclaimer devoid of secular purpose and called the school board’s stated purpose to promote critical thinking a “sham.” The TPSB’s request for an en banc hearing before the Fifth Circuit Court was denied by an 8–7 vote. In addition, the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari by a vote of 6–3. In a rare written dissenting opinion of the denial of certiorari, Justice Scalia (joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Thomas) stated the opinion that Lemon lacked credibility and “we stand by in silence while a deeply divided Fifth Circuit bars a school district from even suggesting to students that other theories besides evolution—including but not limited to, the Biblical theory of creation—are worthy of their consideration” (Stader, Armenta, & Hill, 2002).

In another challenge to the teaching of evolution in high schools, a Pennsylvania school board passed a resolution stating that “students will be made aware of gaps/problems in Darwin’s Theory and other theories of evolution, including . . . intelligent design” (quoted in Armenta & Lane, 2010, p. 78). The policy references intelligent design and the book Of Pandas and People. After a lengthy trial, Judge John E. Jones applied both the Lemon and endorsement tests and issued a sharply worded ruling in which he held that “intelligent design” was, as the plaintiffs argued, a form of creationism, and therefore unconstitutional (Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 2005). Debates at the state level in Kansas, Utah, Texas, and several other states as well as intelligent design and evolution debates at local school boards across the country demonstrate the continued intensity generated by this issue (Armenta & Lane, 2010).

The Equal Access Act and Religious Expression

During the 1970s and early 1980s, courts generally supported the right of school districts to prohibit student-led religious clubs or groups on campus. The Equal Access Act (20 U.S.C. 4071-74) was passed in 1984 in response to public pressure and lobbying by Christian groups. The law applies only to public secondary schools that allow non-curricular clubs to meet outside of the school day or during other non-instructional time. An understanding of the Equal Access Act begins with forum analysis. A forum is simply a place, and speech rights can be determined by the nature of the place. Courts have referred to non-public fora, public fora, designated fora, limited public fora, and open fora. Community and federal parks are generally considered public or open fora. Restrictions on speech in a public forum require that the state demonstrate a compelling interest in suppressing the speech. Schools are usually considered to be either limited open fora or closed fora, depending on the circumstances. A closed forum is created when a school district does not allow non-curricular groups or clubs to meet during non-instructional time. Restrictions on all non-curricular speech are permissible in a closed forum. A limited open forum is created when schools allow non-curricular clubs or groups to meet during non-instructional time. Restrictions on speech are permissible in a limited open forum as long as the restrictions are reasonably related to the educational mission of the school and are viewpoint neutral. For example, a city government may not be able to ban certain activities in a public park (open forum) that a school district (limited open forum) may be able to ban on school property.

The Equal Access Act applies to schools that have created a limited open forum by allowing at least one student-led, non-curriculum club to meet outside of class time. The language in the Equal Access Act is fairly straightforward. A secondary school that has created a limited open forum must allow additional clubs to be organized, as long as:

The meeting is voluntary and student-initiated

Teachers or other school employees do not sponsor the group

School employees do not promote, lead, or participate in a meeting

School employees are present at religious meetings only in a supervisory or non-participatory capacity

The meeting does not materially and substantially interfere with the orderly conduct of educational activities within the school

Non-school persons may not direct, conduct, control, or regularly attend activities of student groups

Viewpoint Discrimination

The Equal Access Act creates a statutory right for equal access to school facilities and vehicles of expression designated as a limited open forum. The extent of these rights is determined by policy and past practice. If a school allows non-curricular clubs to meet at lunch, during an advisory period, or after school, a limited open forum has been created during these times and places. If a school allows non-curricular student groups access to announcements or bulletin boards, for example, then these venues are now considered limited open fora (“Guidance on Constitutionally Protected Prayer,” 2003). Viewpoint discrimination occurs when some groups such as an after-school chess club are allowed to meet or use school bulletin boards, school announcements, or other means of school-sponsored communication and other groups such as the Fellowship of Christian Athletes are denied access on an equal basis (see Donovan v. Punxsutawney, 2003, as an example).

This same logic applies when school districts have a policy or practice of allowing non-profit groups access to school bulletin boards, take-home flyers, or other means of communication. For example, several school districts allow non-profit groups to furnish flyers advertising activities of interest to children for students to take home to their parents. This policy or practice creates a limited open forum (“Guidance on Constitutionally Protected Prayer,” 2003). Consequently, religious groups must be treated the same as non-religious groups (see Child Evangelism Fellowship of Maryland, Inc. v. Montgomery County Public Schools, 2002, and Hills v. Scottsdale, 2003, as examples). Courts use the same logic when considering district facility use by community groups after school. If, for example, by policy or by past practice a board has allowed the YMCA or city council to use school facilities, a limited open forum has been created and religious groups must be treated the same as non-religious groups (Good News Club v. Milford Central School, 2001).

Student Challenges to Equal Access

One of the unintended consequences of the Equal Access Act was to create a venue by which more controversial groups, such as gay and lesbian support groups, could gain access to school facilities. If the school has created a limited open forum by allowing other non-curricular groups to meet during non-instructional time, the Equal Access Act prohibits schools from denying the same access (facilities, bulletin boards, hallways, and announcements, for example) to these groups (Colin v. Orange Unified School District, 2000; East High School Prism Club v. Seidel, 2000; Straights and Gays for Equity v. Osseo Area Schools, 2006, reaffirmed in 2008; and White County High School Peers Rising in Diverse Education v. White County School District, 2006, are examples of federal court equal access decisions supporting gay and lesbian support groups). In an exception to this trend, a Texas federal district court sided with the school’s decision to ban a gay–straight support group in Caudillo v. Lubbock (2004). This case differs from the other cases cited in at least one significant way: The gay–straight group allied itself with an outside advocate whose website linked information about safer sex practices. The school and the court viewed this information as “sexually explicit” and “obscene.”

Unfortunately, supporting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transsexual support groups’ petition for inclusion is sometimes not as easy as it sounds. For example, controversy followed when the Gay–Straight Alliance (GSA) petitioned the Boyd County (Canonsburg, Kentucky) High School to meet during non-instructional time, to use hallways and bulletin boards, and to make club announcements during homeroom as other student groups did. Controversy surrounding the GSA petition included a student walkout, open hostility from opponents, an acrimonious school board meeting, and a protest from local ministers (Boyd County High School Gay Straight Alliance v. Board, 2003). The district court had little trouble determining that Boyd County High School had created and continued to operate a limited open forum during non-instructional time and homeroom. Denying GSA the same opportunities violated the Equal Access Act. Next the court considered the uproar and disruption surrounding GSA. The court acknowledged that schools could ban groups that created “material and substantial disruption” to the educational process (Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969). However, the disruption was caused by GSA opponents, not GSA club members. This is an important point. The court interpreted Tinker v. Des Moines School District (1969) and the “heckler’s veto concept” (Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 1942) as designed to prevent school officials from punishing students for unpopular views instead of punishing the students who respond to the views in a disruptive manner. Consequently, the district must furnish the same opportunities to GSA as other non-curricular student groups. In short, “the values underlying the First Amendment demand that the conduct of hecklers not be permitted to quash the legitimate, non-disruptive, appropriately timed, appropriately mannered, and appropriated placed expression of students in public schools” (Stader & Graca, 2010).

Boy Scouts of America Act

The Boy Scouts of America Equal Access Act (Boy Scouts Act) is part of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002. Under the Boy Scouts Act, school districts that have created a limited open forum by allowing one or more outside youth or community groups to meet on school premises or use school facilities before or after school hours may not deny equal access to the Boy Scouts or any other youth groups listed as a patriotic society. According to this act, school districts may not deny access or discriminate against the Boy Scouts or other patriotic youth groups for reasons based on membership or leadership criteria or oath of allegiance to God and country. The act does not require that schools sponsor the Boy Scouts or other similar organizations, but does require that these groups have equal access to facilities and other means of expression.

State-Sponsored Religious Activities

At least 35 states have legislation authorizing or requiring a moment of silence, meditation, or reflection at the beginning of each school day (Education Commission of the States, 2000). As long as the statutes does not authorize teachers to lead “willing students” in a prescribed prayer (Wallace v. Jaffree, 1985) or use language that seems to encourage students to use the time to pray (Doe v. School Board of Ouachita Parish, 2001), this type of legislation has been challenged with limited success. For example, the Fourth Circuit Court has recently affirmed a district court ruling that Virginia’s moment of silence law is constitutional (Brown v. Gilmore, 2001). The Fifth Circuit has more recently reached a similar conclusion by declaring a Texas moment of silence law constitutional (Croft v. Perry, 2009).

Challenges to the Pledge of Allegiance based on the claim that the words “one nation under God” violate the Establishment Clause have met a similar fate. The Fourth Circuit and the Seventh Circuit both ruled that the National Pledge passes constitutional muster under the Establishment Clause, even though the words “under God” were added to the pledge by Congress in 1954 (Myers v. Loudon County Public Schools, 2005; Sherman v. Community Consolidated School District 21, 1992). The Texas Pledge of Allegiance was amended in 2007 to insert the words “under God.” The amended Texas Pledge reads “Honor the Texas flag: I pledge allegiance to thee, Texas, one state under God, one and indivisible.” Texas state law requires students to recite the National Pledge and the Texas pledge to the state flag once during each school day. The Texas Pledge law has been upheld by the Fifth Circuit (Croft v. Perry, 2010).

District-Sponsored Religious Activites

School districts as well as administrators, teachers, and other school employees are prohibited from sponsoring, endorsing, discouraging, or encouraging religious activity. It is permissible to release students for off-campus religious instruction during the school day, and many states have laws authorizing such practices (see Pierce v. Sullivan, 2004, as an example). Transportation and any expenses for instructional materials may not be supported by school district funds. It is unlikely, although not certain, that the giving of credit toward graduation for participation in off-campus religious instruction is constitutional. Released time for on-campus religious instruction is very problematic (Haynes & Thomas, 2001). For example, the Rhea County (Tennessee) school district had a long-standing practice of permitting Bryan College to conduct “Bible Education Ministry” in the county’s public elementary schools. The classes were conducted by Bryan College volunteers for 30 minutes once a week during the school day. The content of the lessons was clearly religious. On judicial review, the Sixth Circuit Court had little difficulty concluding that because the instruction occurred during the school day and on school property, it sent a “clear message of state endorsement of religion—Christianity in particular—to an objective observer” (Doe v. Porter, 2004).

Displays and Holidays

Holiday programs, often religious in content and purpose, dominate Christian traditions. Increased religious diversity and sensitivity to the religious views of others has created some concern over these traditions. Thus, sensitivity and an understanding of other perspectives are necessary. As Mawdsley and Russo (2004) point out, however, any religious displays may be suspect. The problem is, when is a display too religious? Or conversely, when is a display not religious enough? For example, David Saxe brought suit against the State College (Pennsylvania) Area School District claiming that a table display and song program at an elementary school holiday concert were not “Christian enough” (Sechler & Saxe v. State College Area School District, 2000). The table display was composed of several items including a Menorah, a Kwanzaa candelabrum, and several books. The concert consisted of several non-religious songs and a parody that apparently offended Saxe. On review, the district court found that the holiday display and song program sent a message of inclusion and were consistent with applicable U.S. Supreme Court rulings. Although seemingly frivolous, this case illustrates the fine line many school leaders walk between meeting community demands for continuing religious traditions and increased plurality and demands for neutrality.

It is permissible to include some religious selections in school concerts and even to allow performances at religious sites as long as non-religious sites and music are also selected (Mawdsley & Russo, 2004). However, concerts dominated by religious music, especially when the concert is presented as part of a particular religious holiday, should be avoided (Haynes & Thomas, 2001). It has been clearly established that students should not be required to participate in any school activity, or part of an activity, that may be offensive to their religious beliefs. For example, two sophomore members of the school choir and their parents filed suit to prohibit the choir from rehearsing and performing “The Lord’s Prayer.” The district court granted the plaintiffs’ request for a permanent injunction (Skarin v. Woodbine Community School District, 2002).

Linking to Practice

Do:

Understand the limitations on religious music and displays and where they are allowed as part of the curriculum, in concerts, and other public performances.

Establish policies to fairly accommodate those students who wish to be excused from a concert or public performance (or possibly from a single song) because of religious reasons. The policy should be fairly administered and routinely granted. The policy should state reasonable ways for the student to make up the performance and not suffer grade penalty for failure to participate.

Examine the selection of holiday music and displays before controversy erupts.

Understand that any school-sponsored religious display is open to challenge (Mawdsley & Russo, 2004). Some challengers may consider the display too religious, others that the display is not religious enough.

Including a wide range of secular, religious, and ethnic symbols as part of holiday displays may immunize schools from sponsorship concerns but possibly not from accusations of insensitivity to Christian traditions (Mawdsley & Russo, 2004).

Become familiar with the nature and needs of the religious groups in the school community (Haynes & Thomas, 2001).

Murals, Signs, and Other School-Sponsored Speech

School-sponsored signs, literature, murals, and paintings have also generated controversy. However, courts are reluctant to second-guess the reasonable rules and regulations developed by school administrators. For example, a Wisconsin school principal invited student groups to paint murals in the school. Two student members of the Bible Club sued over the principal’s refusal to approve their preliminary sketch in totality (Gernetzke v. Kenosha Unified School District, 2001). The proposed mural included a heart, two doves, an open Bible with a well-known passage from the New Testament, and a large cross. The principal approved all but the cross, reasoning that so salient a Christian symbol would invite other suits and force him to approve other less savory murals proposed by the Satanic or neo-Nazi elements present in the school. The Seventh Circuit Court affirmed a lower court ruling in favor of the school district. The court was careful to point out that the principal had refused all or parts of other secular murals. His reasonable concerns over litigation and disorder did not demonstrate discrimination, but were a legitimate exercise of his authority to control messages that might cause disruption or bear the imprint of the school. Similarly, the Ninth Circuit Court found a school district’s decision to exclude certain advertisements on a baseball-field fence, including religious ones, reasonable (DiLoreto v. Downey Unified School District, 1999).

In a similar decision, the 10th Circuit Court ruled that Columbine High School officials could exercise editorial control over numerous tiles designed to be permanently attached to school hallways. Current and past students, parents, rescue and police personnel, and mental health workers involved in the 1999 Columbine shooting were among those invited to participate in the project. The guidelines specified that tiles with references to the attack, names or initials of students, Columbine ribbons, religious symbols, or obscene or offensive content would not be fired or hung. Several tiles painted by the families of the victims violated these rules. After a meeting with families, the restrictions against tiles with their children’s names, dates other than 4-20, and the Columbine ribbon were relaxed, and parents were invited to repaint their tiles. The parents refused to change or repaint the tiles and brought suit. In an interesting and wide-ranging opinion, citing various fora analyses, forms of speech, and Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the 10th Circuit Court found that the tiles conveyed approval of the message by the school and were subject to the reasonable rules and restrictions developed by the district (Fleming v. Jefferson County School District R-1, 2002 cert. denied).

Students and Religious Expression

Students often wish to share their religious beliefs with other students in the school. Certainly, students do have this right under the Free Exercise Clause. For example, student-initiated before- and after-school activities such as “see you at the pole,” prayer groups, and religious clubs are permissible. Students may read a Bible or other religious material, pray, or engage other consenting students in religious discussion during non-instructional time such as lunch, recess, or passing time between classes. School officials may impose reasonable rules and regulations to maintain order, but may not discriminate against religiously based activities. Administrators, teachers, and other school employees should refrain from encouraging, discouraging, or promoting student prayer, Bible reading, attendance at a religious club meeting, and so forth (“Guidance on Constitutionally Protected Prayer,” 2003). Teachers and other school employees may not pray with students in public schools and may be terminated for doing so. Schools are not required to allow outside adults to come on campus and lead such an event. It is the rights of students, not outside adults, that are protected (Haynes & Thomas, 2001).

It is not permissible for one student’s religion to determine the curriculum for all other students. Students may be excused from certain reading assignments, homework activities, and so forth on religious grounds. Schools may offer alternative assignments. However, if the requests for exemption or alternative assignments become overly burdensome for teachers, it is conceivable that a court would find the school district’s refusal to continue to offer multiple alternative assignments reasonable. A reasonable number of excused absences for religious reasons seem appropriate. Makeup work may be required (Haynes & Thomas, 2001).

One area of concern to many teachers is what to do with student assignments or projects of a religious nature. Teachers may accept assignments or other student work that has a religious theme. In fact, NCLB (2002) clarifies this concept by stating that students may express religious beliefs in homework, artwork, or other written or oral assignments without penalty or reward because of the religious content. Teachers are not required to accept assignments that do not meet the established objectives of the assignment or inappropriately convey that the school sponsors the message (see Settle v. Dickson County School Board, 1995, and C. H. v. Oliva, 1997, as examples).

If policy or practice has allowed students to distribute literature to other students during non-instructional time on school grounds, school policy should be applied equally to the distribution of religious material (Board of Education v. Mergens, 1990; Pope v. East Brunswick Board of Education, 1993). For example, a Massachusetts district court held that it was viewpoint discrimination to prohibit students from (and later punish them for) distributing candy canes containing proselytizing messages sponsored by a school Bible club during non-instructional time. In this case other groups on campus were allowed to distribute literature during non-instructional time (Westfield High School L. I. F. E. Club v. City of Westfield, 2003).

As always, school administrators can deny the distribution of any literature, such as hate literature or literature containing gang symbols, which may cause substantial disruption. Simple disagreement with the message or undifferentiated concerns of disruption may not suffice to justify suppression of student speech.

Mawdsley and Russo (2004) provide the following guidelines regarding student religious expression in public schools:

Students are private actors and are not restricted by the Establishment Clause.

Students with religious messages should not be prohibited from discussing their religious beliefs with others simply because of some undifferentiated fear of disruption.

Students with religious messages must be treated the same as students with non-religious messages.

Schools may choose to prohibit students from distributing religious literature during class time and at school-sponsored events.

Limit student distribution of religious literature to non-instructional time and before and after school.

In addition, school administrators can and should enforce harassment policies where student-to-student proselytizing has become unwelcome (Mawdsley, 1998).

Linking to Practice

Do:

Acknowledge the rights of students to express their religious beliefs in school assignments, during non-instructional times, and before and after school.

Understand that murals, signs, tiles, sports programs, and advertisements at extracurricular events convey the impression of school sponsorship.

Student-Led Prayers at Graduation

Prayers at graduation exercises and baccalaureate services have been a long-standing tradition at public schools throughout the United States. However, in a hotly debated ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court found such prayers unconstitutional (Lee v. Weisman, 1992). In response to Weisman, several school districts have considered allowing students to vote on whether to select a student to deliver a message of their choosing at school events and graduation. On one side of the debate are those who believe that student religious speech at graduation ceremonies violates the Establishment Clause. The U.S. Supreme Court supported the separationist argument in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000). In Santa Fe, the court pointed out that constitutional rights are not subject to vote. In other words, a majority of students could not vote to suspend the Establishment Clause and have organized prayer at a school-sponsored event. In this reasoning, a graduation exercise is a school-sponsored event, and students are still being coerced, however subtly, to participate in a religious activity. Even a “non-sectarian” and “non-proselytizing” prayer may not solve the problem. To some Christians, the idea of a non-sectarian prayer is offensive. In addition, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Weisman that even non-denominational prayers may not be established by the government. There is also the problem of school officials trying to figure out whether or not a particular student prayer is proselytizing (Haynes & Thomas, 2001).

For example, the Ninth Circuit Court upheld a school district’s decision not to allow two students to deliver a message at graduation that school officials considered proselytizing (Cole v. Oroville Union Free School District, 2000). The Ninth Circuit was soon faced with a similar question of a school principal’s censoring the proselytizing portions of a salutatorian address at graduation (Lassonde v. Pleasanton Unified School District, 2003). In this particular case the speech contained several personal references to God as well as several overtly proselytizing sections. Reasoning that the personal statements were acceptable, the school principal and district legal counsel censored the proselytizing comments of the speech because of Establishment Clause concerns. The student proposed a “disclaimer” stating that the views of the student speakers did not necessarily reflect the views of the district. This proposal was rejected by the district. The student reluctantly agreed to delete the proselytizing portions with the understanding that he could distribute uncensored copies of his speech outside the commencement area. One year later the student brought suit alleging that the censorship of his speech violated his First Amendment rights. The court held the actions of the district necessary to avoid a conflict with the Establishment Clause. The court reasoned that because the school district had obvious control over graduation and by past practice reviewed student speeches, any speech or actions would bear the imprint of the school.

On the other side of this debate are those who contend that not allowing students to express their religious beliefs at graduation violates the Free Exercise Clause. This view has met with some success. For example, the Fifth Circuit Court held in 1992 that student-led prayer that was approved by a vote of the students and was non-sectarian and non-proselytizing was permissible at high school graduation ceremonies (Jones v. Clear Creek Independent School District, 1992). In addition, the 11th Circuit Court affirmed a lower court ruling that found student-initiated, student-led prayer during graduation permissible so long as the administration and faculty were not involved in the decision-making process (Adler v. Duval County School Board, 2000). As Judge Hill of the 11th Circuit Court explains:

The . . . (Santa Fe) . . . policy is not a neutral accommodation of religion. The prayer condemned there was coercive precisely because it was not private. (However), a policy that tolerates religion does not improperly endorse it. Private speech endorsing religion is . . . protected—even in school. Remove the school sponsorship, and the prayer is private [italics added]

(Chandler v. Siegelman, 2000, selected quotes).

One suggestion for avoiding this controversy outlined in “Guidance on Constitutionally Protected Prayer” (2003) is a disclaimer clarifying that the speech (or views) expressed are the speaker’s and not the schools. These guidelines seem to suggest that schools may remain neutral by adding a disclaimer to the program. As Haynes (2003) points out, this approach may essentially create a public forum or free speech zone that relieves school officials from prior review of commencement speeches. Schools could continue to control profane, sexually explicit, or defamatory speech. However, the speech could include political or religious views offensive to many in the audience. In addition, if the speech is not reviewed in advance, any controversial, profane, or explicit views may not be known until after the speech has begun. School officials would then be faced with the unpleasant choice of either interrupting the speech or allowing it to continue. Further, as the Ninth Circuit Court pointed out in Lassonde (2003), disclaimers do not protect those with minority viewpoints from being coerced into choosing between an important milestone and being subjected to an unpleasant or unwanted proselytizing speech.

Haynes (2003) suggests that the best place for prayers and sermons may be baccalaureate or other religious services scheduled after school hours during the week leading up to commencement. Baccalaureate services sponsored by private groups are permissible as long as the district is not favoring or disfavoring particular groups. For example, allowing the senior class to select the location and speakers for baccalaureate would seem permissible. If the school makes facilities available to other private groups, the Equal Access Act requires that facilities also must be made available to private groups for baccalaureate services.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Discuss the role of students as commencement speakers. Develop proactive policies before controversy erupts.

Seek common ground where individual groups of parents and students may express their religious preferences at extracurricular events without involving a school-owned public address system. A “moment of silence” would be one example (Haynes, 2003).

Do Not:

Create an open forum at commencement. It is difficult to understand how a disclaimer can immunize school officials from criticism for excessive proselytizing or from profane or unpopular speech at commencement services sponsored by the school.

Employees and Religious Expression

It would be unreasonable—and impossible—to expect teachers, administrators, and board members not to have religious beliefs. However, when employees walk through the schoolhouse gate, they assume the mantle of state authority and are required to take a neutral position while carrying out their duties. Administrators, teachers, and other school employees are prohibited by the Establishment Clause from encouraging or discouraging prayer, and from actively participating in religious activity with students at school (“Guidance on Constitutionally Protected Prayer,” 2003). For example, teachers and other school officials should not participate in or lead student prayer or use their position as respected role models to promote or encourage outside religious activities such as revivals, church outings, or other faith-based activities. In short, the rights of school employees and school representatives can be limited or curtailed where efforts at religious expression could be reasonably interpreted as implying public school endorsement (Mawdsley & Russo, 2004). For example, a Louisiana district court issued a permanent injunction prohibiting an elementary school principal from distributing Bibles to fifth-grade students (Jabr v. Rapides Parish School Board, 2001). Similarly, the Eighth Circuit found the orchestration of baccalaureate ceremonies by senior class sponsors to violate the Lemon test. The court found that the school district took an active role in the production of “a service that continued the tradition of having local clergy offer prayers and religious messages” (Warnock v. Archer, 2006). This case points out that baccalaureate services should in fact be student organized and led.

Administrators, teachers, and other school employees may take part in religious activities where the overall context makes it clear that they are not acting in their official capacity (“Guidance on Constitutionally Protected Prayer,” 2003). For example, it would seem appropriate for school employees to participate in a religious activity held at the school during the evening and in privately sponsored baccalaureate services. Teachers and others may elect to pray or read the Bible or other religious documents during the school day, as long as students are not involved, and they may wear non-obtrusive jewelry or religious symbols such as a cross or star of David.

Teachers and other employees may be disciplined and even terminated for promoting religious participation, even subtly. For example, fifth-grade teacher Roberts read silently from a Bible he habitually kept in plain view on his desk. In addition, a Christian poster was displayed in the classroom, and the classroom library contained two Christian books. Roberts did not read aloud or overtly proselytize to students. When a parent complained to the principal about Roberts’s poster and the two books, the teacher was instructed to remove the Bible from his desk, not to read from the Bible during school time, and to remove the poster and two Christian books from the classroom. On appeal, the 10th Circuit Court affirmed the trial court ruling, reasoning that the school district acted properly in taking action to disapprove of classroom activity that appears to promote a particular religion (Roberts v. Madigan, 1990). Similarly, a district court in Florida upheld the dismissal of a teacher for consistently refusing to follow a corrective action plan that prohibited her from distributing Bibles and posting religious posters in her classroom (Tuma v. Dade County Public Schools, 1998).

Linking to Practice

Do:

Develop proactive policies that outline the religious rights and responsibilities of public school employees while on campus or representing the school at extracurricular events, field trips, or other off-campus school-sponsored activities.

Do Not:

Permit school employees to lead, encourage, hinder, or participate in student religious expression on school grounds.

Prayer at School Board Meetings

In Lemon v. Kurtzman, the U.S. Supreme Court articulated a three-pronged test to determine whether or not a governmental action is constitutional. Assuming that a school board has an obvious connection to public education, the Sixth Circuit found that prayer before a school board meeting violated all three prongs of Lemon (Coles v. Cleveland Board of Education, 1999). In a more recent example, a Tangipahoa Parish (Louisiana) School Board practice of starting board meetings with a sectarian prayer delivered by a board member, the superintendent, or a local minister was challenged by a parent (Doe v. Tangipahoa, 2005). The federal district court for eastern Louisiana noted that this and similar cases sit between two competing concepts: State-endorsed prayer is not permissible in public schools, but is permissible at the opening of a legislative session. The court also noted that school boards hold both a legislative and an educational function. Following the lead of the Sixth Circuit Court in Coles, the district court reasoned that a school board has an intimate relationship with the public school system. Therefore, the school board prayer violated Lemon and was thus unconstitutional.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit determined that the 1983 U.S. Supreme Court case Marsh v. Chambers applied to school board prayers (Doe v. Tangipahoa, 2006). In Marsh, the court considered a challenge to a Nebraska practice of employing a chaplain to deliver religious invocations during legislative sessions. The court reasoned that historically the framers established a paid chaplain position for federal legislative sessions. Therefore, if the framers did not see a problem with federal legislative prayer or chaplaincy, why should this be a problem for a state legislative body? On review, the district court abandoned Lemon and applied the Marsh test to the prayer practice (Doe v. Tangipahoa, 2009). Using Marsh as a guide, the court concluded that despite numerous prayers that referenced Jesus specifically, the Tangipahoa school board prayers fell within the scope of legality under the Establishment Clause (Fetter-Harrott, 2010).

Public Money and Private Schools

For the past half century, the U.S. Supreme Court and several circuit courts have drawn a relatively well-defined line in the sand between public money and aid to private schools. However, several recent decisions have significantly blurred this line and in some cases erased it altogether. This transition essentially began with Agostini v. Felton (1997), where a Supreme Court majority determined that several past decisions were “no longer good law.” In Agostini the Court determined that Title I monies could be used to provide public employees to teach remedial classes at private schools, including religious schools. In doing so, the Court established two basic criteria for determining the constitutionality of such aid: (1) Can any religious indoctrination that occurs in those schools be reasonably attributed to governmental action, and (2) does the aid program have the primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion? The Court followed this same logic in Mitchell v. Helms (2000) in upholding the constitutionality of the use of Title VI monies to purchase equipment for private schools in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana.

Vouchers

One of the more controversial topics is the use of public money to fund student attendance at private and parochial schools through the use of tax credits/deductions or vouchers. A voucher is a “payment the government makes to a parent, or an institution on a parent’s behalf, to be used for a child’s education expenses” (Education Commission of the States, 2002, p. 1). A tax credit provides a direct reduction to the tax liability of a qualifying individual, and a tax deduction is a reduction in taxable income made prior to calculating tax liability (Education Commission of the States, 2002). The constitutionality of publicly funded vouchers has been established at the federal level by the U.S. Supreme Court in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002). In this case, the Court upheld a voucher program in Cleveland by concluding, “The Cleveland voucher program affords parents of eligible children genuine non-religious options.” The Court did not dispute that the program was established for the valid secular purpose of providing educational support for poor children in an admittedly failed school system. Rather, the Court focused on the single legal question of whether the Ohio program advances or inhibits religion. To answer this question, the Court considered the distinction between governmental programs that provide aid directly to religious schools and those programs in which state funds reach religious schools indirectly through the independent choices of numerous parents and students. In the latter case, the public funding is attributed to the student, who may choose to remain at a public school that receives funding according to average daily enrollment or to attend a religious school that receives funding by tuition. A majority of the Court had little trouble making this distinction and held that the Ohio voucher system did not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The U.S. Supreme Court has also considered the question of tax credits for contributions to support scholarships for private schools, many of which are religious in nature (Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn, 2011). Arizona provides tax credits for contributions to school tuition organizations, or STOs. STOs use these contributions to provide scholarships to students attending private schools, many of which are religious. A group of Arizona taxpayers challenged the STO tax credit as a violation of Establishment Clause. The Court opined that a tax credit allows dissenting taxpayers to use their own funds in accordance with their own consciences. In this case, the STO tax credit does not “extrac[t] and spen[d]” a conscientious dissenter’s funds in service of an establishment or “force a citizen to contribute” to a sectarian organization. Rather, taxpayers are free to pay their own tax bills without contributing to an STO, to contribute to a religious or secular STO of their choice, or to contribute to other charitable organizations.

With the federal question answered, the battleground now moves to the various states. In several states, voucher proponents face more restrictive state constitutional clauses than found in the federal Establishment Clause. These clauses are commonly referred to as “Blaine amendments” and effectively bar the use of public money for religious causes. Other state constitutions have provisions that protect individuals from being compelled to support any religious group without their consent. Currently 36 states have Blaine amendments; 18 states have both Blaine amendments and a consent clause. Only Louisiana, Maine, and North Carolina have neither (Darden, 2002).

Summary

In the past decade the legal battle between two equally determined segments of our society has intensified. On occasion, public school employees and students are vocal advocates of one segment or the other, often simultaneously in the same school. On other occasions, community groups create significant pressure on local schools to accommodate their particular religious preferences. Students, teachers, and community groups do have a legal right to practice and advance their religions, but not at the expense of others. Finding this balance in this emotional arena is exceedingly difficult. However, as America’s schools become more ethnically and religiously diverse, failures to recognize, respect, and accommodate this increased diversity hold the potential of needlessly Balkanizing an already challenged public school system.

Connecting Standards to Practice

Let Us Pray

Assistant Superintendent Sharon Grey was well aware of the religious views of new school board member Alison Watts. Consequently, Sharon was not surprised when Alison introduced a new policy for the board to consider. The proposed policy, entitled “Student Expression of Religious Viewpoints,” would create a limited open forum at football games and commencement activities and allow students to speak at these events. The policy would require Riverboat High School administrators to put disclaimers in graduation and football programs that the student speech is not school sponsored. It also required the administration to consult with the student council membership and create a process for the neutral selection of students to speak at such events.

The proposed policy read, in part:

To ensure that the school district does not discriminate against a student’s publicly stated voluntary expression of a religious viewpoint and to eliminate any actual or perceived affirmative school sponsorship or attribution to the district of a student’s expression of a religious viewpoint Riverboat School District shall adopt a policy, which must include the establishment of a limited open forum for student speakers at commencement activities and all high school home football games. The policy regarding the limited open forum must also require the high school administration in consultation with the student council membership to: (1) Provide the forum in a manner that does not discriminate against a student’s voluntary expression of a religious viewpoint or on an otherwise permissible subject; (2) Provide a method, based on neutral criteria, for the selection of student speakers at high school football games and graduation ceremonies; (3) Ensure that a student speaker does not engage in obscene, vulgar, offensively lewd, or indecent speech; and (4) State, in writing, that the student’s speech does not reflect the endorsement, sponsorship, position, or expression of the district.

Question

Argue for or against the proposed policy to create a limited open forum at football games and commencement. Clarify the legal question. Cite ISLLC standards and case law (i.e., Lee v. Weisman, Lamb’s Chapel v. Center Moriches, Jones v. Clear Creek, etc.) to support your answer. Write a letter or memorandum to the superintendent or school board president justifying your position.