Dress CodeState law does not give students the right to choose their mode of dress. Thus, the matter of student dress and grooming is at the discretion of local school districts. A common question rem

Chapter 5 Due Process, Student Discipline, Athletics, and Title IX

Introduction

Administrators are empowered by a wide variety of federal, state, and local laws and policies to maintain orderly and safe schools. However, students do not forfeit all of their constitutional rights. This is especially true when students are off-campus. For many secondary school leaders, extracurricular activities, especially athletics, are also an important responsibility. Title IX is designed to protect students from being denied the benefits of any educational program or activity, including athletics, because of sex. Basic fairness and a healthy respect for these rights is part of being an ethical and humane school leader. This chapter considers the balance between the obligation to maintain order and safety while respecting the rights of students. The Justice as Fairness principles of the American political philosopher John Rawls, the due process rights of students, corporal punishment, excessive force, and extracurricular activities are presented here.

Focus Questions

What is a “well-ordered” school, and how is this concept related to due process and student discipline?

Can, and should, students be disciplined for off-campus behavior?

Is consistency in student discipline always rational?

Should schools use corporal punishment to control student behavior? What standards should courts use when reviewing charges of excessive force during corporal punishment?

Key Terms

Corporal punishment

Due process

Liberty interest

Procedural due process

Property interest

Shocks the conscience

Substantive due process

Title IX

Well-ordered school

Case Study The Case of the Powdered Aspirin

As principal of Medford Elementary School, Charlene Daniels was quite concerned about the rumors that several students had been bringing powdered aspirin to school and “huffing” the powder in the restroom after lunch and after recess. At the last faculty meeting, Charlene had discussed her concerns with the faculty and asked them to be more vigilant than usual as students left the cafeteria and returned from recess. It was this vigilance that led sixth-grade teacher Ralph Smith to her office. “Ms. Daniels, I just saw sixth-grader Lasiandra Davis go into the girls’ restroom next to the cafeteria. I just caught a glimpse, but I am sure I saw a brown paper bag in her hand. I could not follow her into the restroom, but I sent Mrs. Hale to go check.”

Mrs. Hale came out of the restroom just as Charlene and Ralph arrived holding a brown paper bag covered with a white powdery substance. “I found this in the trash can under some papers. When I arrived Lasiandra Davis was the only one in the restroom. She saw me searching the trash can and left the restroom before I could stop her.”

Charlene immediately placed the brown bag with the white substance in a plastic container, called the police, and started her own investigation. The investigation lasted all afternoon, interrupted several classes, and caused several students to miss significant time in the classroom. All five of the sixth-grade teachers spent considerable time talking to their students trying to get more information. By the end of the day, Charlene was fairly convinced that Lasiandra had indeed been in possession of the paper bag. She based her conclusions on a couple of students’ testimony that they had seen Lasiandra with a paper bag right before lunch, Lasiandra’s teacher’s observation that Lasiandra had seem “agitated” after lunch the past several days, and Mr. Smith’s belief that he had seen Lasiandra take a brown paper bag into the restroom.

Charlene called Lasiandra to the office and confronted her with the allegations. Lasiandra denied that she had brought powdered aspirin to school. She said that she was not in possession of a paper bag after lunch as Mr. Smith had said, and that she knew nothing about the bag found in the trash. Charlene informed Lasiandra that she was suspending her for 5 days for “disturbing instruction.” She based this finding on the fact that all sixth-grade classes had been disrupted, that all five of the sixth-grade teachers had participated in the investigation rather than teach their classes, and that she as principal spent all afternoon investigating the incident.

Lasiandra’s mother and father were not happy with Charlene’s decision. Both parents had called Superintendent Johanson. Charlene’s parents and the superintendent had agreed to meet the next day to appeal the suspension.

Leadership Perspectives

A reasonably orderly school promotes and protects the welfare and safety of students and staff and provides the foundation for a safe and effective school environment (ISLLC Standards 3 & 3C). A reasonably orderly building environment also promotes social justice, equity, and accountability as called for in ISLLC Standard 5E. However, not all orderly schools are good schools. Not all orderly classrooms promote efficient and effective learning (ISLLC Standard 3). As in a maximum-security prison, order in schools and classrooms can be obtained by rigid rules and punishment. As discussed in the previous chapter, schools and classrooms that achieve order in these ways often create a hostile, alienating, and toxic environment that is not conducive to the types of teaching and learning for which “good” schools are noted (Skiba & Peterson, 2000). There is little question, however, that effective schools and classrooms must have a system of enforced rules in place to provide the foundations for orderly and safe school cultures that promote learning. Unfortunately, a very fine line sometimes exists between maintaining order and creating overly punitive school cultures.

ISLLC Standards 3 & 3C

ISLLC Standard 5E

ISLLC Standard 3

The opening case study “The Case of the Powdered Aspirin” illustrates this. ISLLC Standard 2A calls for school leaders to develop and sustain a culture of collaboration and trust. Principal Daniels has exemplified this standard by enlisting faculty in support of her efforts to maintain a substance-free environment. There is no question that students bringing powdered aspirin to school and “huffing” it is a significant school safety and student health concern. Principal Daniels is correct in being concerned about the welfare and safety of students in her school (ISLLC Standard 3C). She is also correct in accepting Mr. Smith’s assertion that he had seen Lasiandra Davis take a brown paper bag into the girl’s restroom after lunch. Principal Daniels may be correct in her belief that Lasiandra Davis is at least one of the students bringing powdered aspirin to school. As principal she is empowered by a wide variety of state laws and school board policies to enforce reasonable rules designed to maintain a safe and substance-free environment. As principal, she also has a responsibility to treat students, teachers, and others fairly and in an ethical manner regardless of the circumstances (ISLLC Standard 5).

ISLLC Standard 2A

ISLLC Standard 3C

ISLLC Standard 5

Lasiandra Davis also has certain rights and responsibilities. She has the responsibility to follow reasonable rules. She also has the right to be treated fairly. School leaders’ responsibility to promote good order and discipline must be balanced with student rights to be treated fairly and in an ethical manner. This balance, reflected in ISLLC Standards 3 and 5, is addressed in this chapter by considering the “justice as fairness” concepts of the American political philosopher John Rawls, and the legal concepts of due process, student discipline, and Title IX.

ISLLC Standards 3 and 5

Student Rights and the Well-Ordered School

John Rawls’s concept of justice as fairness (2001) provides guidance when considering the balance of the sometimes conflicting principles of maintaining a reasonably orderly school that promotes learning, safety and a substance-free environment with the equally compelling requirement that all students be treated fairly. Rawls’s theory of justice as fairness is a political theory, but it is applicable to schools as a concept of local justice. Rawls presents his concept in two principles of justice. The first, presented here, is particularly germane to a discussion of the relationship between student rights and the obligation to maintain order in a positive school culture.

Principle One: Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all. (p. 42)

Principle One assumes that all students, regardless of socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or disciplinary history, are deserving of the same liberties. The fundamental idea is the development of a school culture that exists simultaneously as a fair system of social cooperation that is established by public justification. Social cooperation requires that reasonable persons understand and honor certain basic principles, even at the expense of their own interests, provided that others are also expected to honor these principles. In other words, students can be expected to understand and honor reasonable restrictions on their freedoms. School officials can be expected to reciprocate by promoting fairness and honoring appropriate student rights. In Rawls’s view, it is unreasonable not to honor fair terms of cooperation that others are expected to accept. It is worse than unreasonable to pretend to honor basic principles of social cooperation and then readily violate these principles simply because one has the power to do so. In other words, Rawls views it as unreasonable for school leaders to “talk the fairness talk” but not “walk the walk.” As pointed out in Chapter 1, fairness is a difficult concept. Fairness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. There is no question that walking the walk can be fraught with difficulty. But, as Rawls points out, although it may seem rational at times to violate the principle of fairness and ignore student rights, it is never reasonable.

A school culture based on social cooperation must be publicly justified and acceptable, not only to those who make the rules, but also to others (students, parents, teachers, etc.) who are affected by the school culture. To be effective, public justification should proceed to some form of consensus that assumes that all parties have fundamental rights and responsibilities. Rawls acknowledges that it is unlikely that all members of a diverse school with conflicting needs, values, and priorities will come to the same conclusions and the same definition of a well-ordered school. However, it is important that a reasonable consensus result from the process to serve as a basis for the justification of the need for certain rules and policies to promote order and efficiency.

The Idea of a Well-Ordered School

A school that exists as a fair system of cooperation under a public conception of justice meets ISLLC Standards 2A, 3A, 3C, 4B, 4C, 4D, 5B, 5C, 5D, and 5E. A school existing in this manner—a well-ordered school—has three defining characteristics:

ISLLC Standards 2A, 3A, 3C, 4B, 4C, 4D, 5B, 5C, 5D, and 5E

Everyone in the school accepts, and knows that everyone else accepts, the same concepts of justice. Moreover, this knowledge is mutually recognized as though these principles were a matter of public record. In other words, school leaders, teachers, and students acknowledge and accept that certain basic principles will be honored by everyone.

All personal interactions, policies, and applications of policy are designed to facilitate a system of cooperation.

Students, teachers, and school leaders have a rational sense of justice that allows them to understand and for the most part act accordingly as their positions in the school dictate.

These three concepts provide a mutually recognizable point of view for the development of a school culture that promotes order, safety, and security. A mutual understanding of the roles and responsibilities of administrators, teachers, and students is important. The concept of a well-ordered school characterized by a fair system of social cooperation established by public justification may seem overly theoretical. However, it is embedded in a real problem—the development of a safe, secure, and substance-free school environment that promotes student learning. For example, in a national study of crime and violence in middle schools, Cantor et al. (2001) found that in low-disorder schools, a shared sense of responsibility is present among teachers and administrators. In these schools, principals and teachers for the most part support one another and function well as a team. In contrast, this sense of shared responsibility among teachers and administrators was weak in high-disorder schools. Teachers tended to point fingers at one another, at administrators, and at school security officers for the lack of good order in the school. A school culture based on a public conception of justice provides the framework for a shared sense of responsibility by all concerned in promoting good order and discipline. Well-ordered schools characterized by a fair system of social cooperation established by public justification are most likely to have a school environment that promotes collaboration, trust, and learning (ISLLC Standard 2A); the welfare and safety of students and staff (ISLLC Standard 3C); and social justice and student achievement (ISLLC Standard 5E).

ISLLC Standard 2A

ISLLC Standard 3C

ISLLC Standard 5E

Linking to Practice

Do:

Develop a system of mutually acceptable and publicly justified policies designed to maintain order and promote safety.

Involve a wide range of interested stakeholders in the formulation of school rules.

Model and insist that teachers and other adults in the school honor basic fairness and student rights. Conversely, insist that parents and students honor basic teacher rights.

Use the concept of a well-ordered school to reinforce feelings of emotional safety for students, teachers, and parents.

Use data to publicly justify certain restrictions on student freedom. These data can be used to support school safety interventions or conversely demonstrate that certain interventions may not be needed at this point in time.

Do Not:

Overreact to an isolated incident or criticism and resort to more punitive policies. Defensible school discipline plans should be based on facts, not on opinions, isolated incidents, or whoever can complain the most about student disorder.

Share identifiable student data in group settings or with individuals without a legitimate educational interest in the data. Sharing identifiable student data is a violation of FERPA and can destroy trust and erode feelings of emotional safety.

Due Process and the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

As Rawls points out, the concept of fairness is fundamental to a well-ordered school. The concept of justice as fairness is reflected in the legal principle of due process. Due process is a legal principle that considers the manner of fair and adequate procedures for making equitable and fair decisions integrated into ISLLC Standard 5. A constitutional right to fair procedures is established in the due process clause of both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Both amendments address the concept that persons shall not be deprived of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” A property interest is established by the state when the right to an education is extended to all individuals in a particular class. Therefore, a property interest is affected anytime a student is denied access to a public school education. A liberty interest is defined as a person’s good name, integrity, or reputation. A liberty interest is created when an administrative action creates potential harm to future job or educational opportunities. There are two forms of due process: procedural and substantive. Procedural due process considers the minimum sequence of steps taken by a school official in reaching a decision, usually defined as notice and the right to a fair hearing. Substantive due process considers the fairness of a decision and involves such concepts as adequate notice, consistency of standards, how evidence was collected and applied to the decision, the rationality of the decision, and the nexus of the decision with a legitimate educational purpose.

ISLLC Standard 5

Procedural Due Process and Out-of-School Suspension

Suspension generally refers to removal from school for a relatively short period—usually 1 to 10 days. Expulsion is generally defined as suspension from school for more than 10 days (Stader, 2011). Decisions for suspensions of 10 days or less are usually made by campus administrators. The maximum length of time for which campus administrators can suspend a student varies by state. For example, Missouri state law allows campus administrators to suspend students for up to 10 days (RSMo 167.171.1). Texas state law restricts campus administrators to 3 days or less (Texas Education Code 37.009). Regardless of the differences in state law, the due process requirements for out-of-school suspensions of 10 days or less were established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Goss v. Lopez (1975).

This case considered Ohio law empowering school principals to suspend students for up to 10 days. This law also empowered principals to expel students. Expelled students or their parents had the right to a hearing before the local board of education. However, students suspended for 10 days or less had no recourse. The Court held that students facing temporary suspension from school (defined as 10 days or less) have a property and liberty interest that qualifies them for due process protection. Based on the assumption that education is the most important function of state and local governments (Brown v. Board of Education, 1954), the Court reasoned that a 10-day suspension recorded on a transcript could seriously damage a student’s reputation and interfere with later educational and employment opportunities. Consequently, even the temporary denial of a student’s property interest in established educational benefits or potential harm to the student’s liberty interest may not be constitutionally imposed without adequate due process protection. The Court established the following procedural guidelines for student suspensions of 10 days or less:

The student must be given oral or written notice of the charges. In other words, the student has the right to know what rule has been broken.

If the student denies the charges, an explanation of the evidence the authorities have and an opportunity for the student to present his or her version of the events is required.

These steps may be taken immediately following the misconduct or infraction that may result in suspension.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Develop a system of mutually acceptable and publicly justified policies designed to maintain order and promote safety.

Involve a wide range of interested stakeholders in the formulation of school rules.

Model and insist that teachers and other adults in the school honor basic fairness and student rights. Conversely, insist that parents and students honor basic teacher rights.

Use the concept of a well-ordered school to reinforce feelings of emotional safety for students, teachers, and parents.

Use data to publicly justify certain restrictions on student freedom. These data can be used to support school safety interventions or conversely demonstrate that certain interventions may not be needed at this point in time.

Do Not:

Overreact to an isolated incident or criticism and resort to more punitive policies. Defensible school discipline plans should be based on facts, not on opinions, isolated incidents, or whoever can complain the most about student disorder.

Share identifiable student data in group settings or with individuals without a legitimate educational interest in the data. Sharing identifiable student data is a violation of FERPA and can destroy trust and erode feelings of emotional safety.

Due Process and the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

As Rawls points out, the concept of fairness is fundamental to a well-ordered school. The concept of justice as fairness is reflected in the legal principle of due process. Due process is a legal principle that considers the manner of fair and adequate procedures for making equitable and fair decisions integrated into ISLLC Standard 5. A constitutional right to fair procedures is established in the due process clause of both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Both amendments address the concept that persons shall not be deprived of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” A property interest is established by the state when the right to an education is extended to all individuals in a particular class. Therefore, a property interest is affected anytime a student is denied access to a public school education. A liberty interest is defined as a person’s good name, integrity, or reputation. A liberty interest is created when an administrative action creates potential harm to future job or educational opportunities. There are two forms of due process: procedural and substantive. Procedural due process considers the minimum sequence of steps taken by a school official in reaching a decision, usually defined as notice and the right to a fair hearing. Substantive due process considers the fairness of a decision and involves such concepts as adequate notice, consistency of standards, how evidence was collected and applied to the decision, the rationality of the decision, and the nexus of the decision with a legitimate educational purpose.

ISLLC Standard 5

Procedural Due Process and Out-of-School Suspension

Suspension generally refers to removal from school for a relatively short period—usually 1 to 10 days. Expulsion is generally defined as suspension from school for more than 10 days (Stader, 2011). Decisions for suspensions of 10 days or less are usually made by campus administrators. The maximum length of time for which campus administrators can suspend a student varies by state. For example, Missouri state law allows campus administrators to suspend students for up to 10 days (RSMo 167.171.1). Texas state law restricts campus administrators to 3 days or less (Texas Education Code 37.009). Regardless of the differences in state law, the due process requirements for out-of-school suspensions of 10 days or less were established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Goss v. Lopez (1975).

This case considered Ohio law empowering school principals to suspend students for up to 10 days. This law also empowered principals to expel students. Expelled students or their parents had the right to a hearing before the local board of education. However, students suspended for 10 days or less had no recourse. The Court held that students facing temporary suspension from school (defined as 10 days or less) have a property and liberty interest that qualifies them for due process protection. Based on the assumption that education is the most important function of state and local governments (Brown v. Board of Education, 1954), the Court reasoned that a 10-day suspension recorded on a transcript could seriously damage a student’s reputation and interfere with later educational and employment opportunities. Consequently, even the temporary denial of a student’s property interest in established educational benefits or potential harm to the student’s liberty interest may not be constitutionally imposed without adequate due process protection. The Court established the following procedural guidelines for student suspensions of 10 days or less:

The student must be given oral or written notice of the charges. In other words, the student has the right to know what rule has been broken.

If the student denies the charges, an explanation of the evidence the authorities have and an opportunity for the student to present his or her version of the events is required.

These steps may be taken immediately following the misconduct or infraction that may result in suspension.

Due process procedures and practices are designed to pose a check on improperly denying a student the right to a public education. Review the opening case study, “The Case of the Powdered Aspirin.” Principal Daniels is “fairly convinced” that Lasiandra is guilty of bringing powdered aspirin to school in a brown bag and that she was in possession of the bag when she went into the restroom. Did Principal Daniels meet the requirements of Goss when she suspended Lasiandra? Lasiandra denied that she was in possession of the powdered aspirin. Mr. Smith was “pretty sure” Lasiandra had a brown paper bag in her possession as she entered the restroom. Lasiandra was the only person in the restroom when the female teacher followed her into the restroom. She apparently was not in possession of the bag when Mrs. Hale entered the restroom, because the bag was found in the trash can. Did Principal Daniels provide Lasiandra with the evidence she had? Why did Principal Daniels suspend Lasiandra for “disturbing instruction” rather than for possession of powdered aspirin with what one can assume the intent to “huff”? Principals (and school boards) may make decisions based on a preponderance of the evidence rather than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” requirement in criminal cases. Does a preponderance of the evidence support Principal Daniels’s decision to suspend Lasiandra?

The procedural requirements established in Goss generally pose little problem for school administrators and should be completed before a decision is made to suspend the student. In cases where a student’s presence endangers persons or property or threatens disruption of the academic process, administrators are justified in the immediate removal of the student from school. A preliminary decision to suspend an unruly or dangerous student may be made as long as the decision maker holds a prompt procedural hearing with the understanding that the preliminary decision to suspend can be reversed (Stader, 2001). However, the necessary notice and hearing should follow as soon as practicable (see C.B. & T.P. v. Driscoll, 1996 as an example). Students are usually not considered to have the same due process rights for punishments such as after-school detention or an in-school suspension (Tristan Kipp v. Lorain Board of Education, 2000). Traditionally, suspended students are not allowed to make up schoolwork that is missed because of the suspension. This practice has been supported by the courts (South Gibson School Board v. Sellman, 2002). The Fifth Circuit has recently held that a “student’s transfer to an alternative educational program does not deny access to public education and therefore does not violate a Fourteenth Amendment interest (i.e. require due process)” (Harris v. Pontotoc County School District, 2011). In addition, courts have been consistent in finding that Miranda warnings are not required when a student is questioned by school authorities regarding possible rule violations in school (Taylor, 2002).

Substantive Due Process

Substantive due process may be defined as follows: “The doctrine that the Due Process Clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments require legislation to be fair and reasonable in content and to further a legitimate governmental objective” (Garner, 2006, p. 228). Substantive due process usually involves four questions: (a) Does the rule or policy provide adequate notice of what conduct is prohibited? (b) Does the rule or policy serve a legitimate educational purpose? (c) Is the consequence reasonably (or rationally) connected to the offense? (d) Is the rule or policy applied equitably?

Question 1: Does the rule or policy provide adequate notice of what conduct is prohibited? This question concerns how accurately the policy or rule articulates or describes actions that would violate the rule or policy. School rules are not required to be as detailed as criminal codes. However, school rules must be written in an age-appropriate format that most reasonable students can understand. Sometimes this is difficult to accomplish. Vague or overbroad rules or policies violate substantive due process because these policies fail to provide adequate notice regarding unacceptable conduct, and they offer no clear guidance for school officials to apply the policy. In other words, school officials have wide latitude to interpret the policy at will or to do more than is necessary to achieve the desired ends. Some examples of vague or overbroad rules may include “anything that brings discredit to the school,” “gang-related activities on school grounds,” “misconduct,” “unacceptable behavior,” or behavior that “creates ill will.” Refer back to the case study “The Case of the Powdered Aspirin.” Although school codes need only be reasonable, is suspension for “interrupting instruction” vague or overbroad? What does “interrupting instruction” mean? However, even in incidents where some ambiguity is present, the U.S. Supreme Court has stated that federal courts should not substitute their own notions for a school board’s definition of its rules (Wood v. Strickland, 1975, and Board of Education of Rogers, Arkansas v. McCluskey, 1982). These cases clarify that as long as a school board’s interpretation and enforcement of rules is reasonable, courts should not interfere.

Question 2: Does the rule or policy serve a legitimate educational purpose? This question considers the balance between individual rights (freedom) of students and the need for good order, safety, and efficiency. For student rights to be restricted, the restriction must serve some legitimate educational function. As long as the rule or policy can be linked to good order, safety, or efficiency, the policy will usually pass muster. For example, the drug testing of students and policies prohibiting weapons are clearly linked to school safety. However, arbitrary or capricious actions that are unrelated to maintaining good order and discipline may violate substantive due process (Woodard v. Los Fresnos, 1984).

Question 3: Is the consequence reasonably (or rationally) connected to the offense? This question considers whether the consequence seems rational in light of the offense, or whether it is arbitrary or capricious. For example, referring an honor student with no disciplinary history for expulsion for being late to school would not appear rational. Think about Lasiandra Davis in the opening case study, “The Case of the Powdered Aspirin.” Lasiandra may or may not be an honor student, and it is possible that she is a royal pain. However, should she be suspended for “interrupting instruction”? Is it not part of a school principal’s job description to investigate potential rule violations, especially one as serious as “huffing” powdered aspirin? She was not suspended for possession of powdered aspirin, but for interrupting instruction. Was the suspension reasonably related to the offense? Courts sometimes comment about the wisdom of a rule or policy and the punishment used to enforce the rule (see, for example, Anderson v. Milbank, 2000). But federal courts are reluctant to substitute their judgment for school board interpretation of rules (Wood v. Strickland, 1975).

Question 4: Is the rule or policy applied equitably? This question can be divided into two concepts: (1) Is everyone similarly situated treated in a similar manner? (2) Does the policy have a disproportional impact on a particular identifiable group of students?

The first concept considers whether or not a policy is applied equally. A recent case involving sexual minority students may illustrate this (C. N. v. Wolf, 2006). Two female California high school students were disciplined for expressing affection toward each other. Heterosexual couples were not disciplined for the same behavior. In other words, policies that are applied to one group of students but not to another may violate the substantive due process rights of students. The second concept considers the intentional or unintentional impact of the policy or rule on a particular identifiable group of students. The decision by the Decatur, Illinois, school district to expel several African American students involved in a fight at a football game illustrates this (Fuller v. Decatur, 2000). African American students composed approximately 46 to 48% of the student body, yet 82% of the students expelled during a 2-year period were African American. However, the court found that similarly situated White students had also been expelled. In other words, the students had to demonstrate both inequitable treatment and disproportional impact. This is a very high standard to meet, especially when school safety is involved.

Long-Term Suspension and Expulsion

In most states, the authority to expel students is reserved for superintendents, school boards, or district hearing officers. In some states, such as Missouri, the school district superintendent (or a designee, in large districts) may suspend a student for up to 180 days (RsMo 167.171). This process is generally referred to as long-term suspension. In other states, only the board of education can suspend a student for more than 10 days.

Regardless of how expulsion is defined, due process requirements are proportional to the potential punishment. In short, the greater the potential loss of a student’s property interest in attending school and the greater the threat to the student’s liberty interest in not having his or her record tainted by school officials, the greater the due process requirements. Therefore, suspensions or expulsions from school longer than 10 days require more elaborate due process requirements than the rudimentary requirements established in Goss v. Lopez (1975). Unfortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court has not established these requirements, and student rights in long-term suspension or expulsion hearings are a conglomeration of various federal and state court rulings, state statutes, and school board policies. These patchwork requirements vary from state to state and circuit court to circuit court. At the heart of the matter, due process requires only that a student facing expulsion receive notice of the charges; notice of the date, place and time of the hearing; and a full opportunity to be heard. Some circuit courts have added further due process requirements in expulsion cases. Therefore, it is important to consult state laws and school board policy before instigating long-term suspension or expulsion. The following general guidelines—in addition to notice of charges, time of the hearing, and an opportunity to present evidence refuting the allegations—likely apply in most states to students facing expulsion from public schools:

Students have the right to a prompt written explanation of the facts leading to the expulsion. Expulsion cases can be challenged when a policy is “vague or overbroad.” For example, “gang-related” has been found to be void for vagueness (Stephenson v. Davenport Community School District, 1997), as has “possession of look-alike” drugs (Board of Education of Central Community v. Scionti, 2000).

During the appeal process, students generally have the right to an evidentiary hearing, including having an attorney present. For example, a North Carolina appeals court overturned an expulsion decision because the student in question was denied the right to counsel during his appeal to the board (In re Roberts, 2002).

Students generally have the right to present and refute evidence and to cross-examine and face witnesses (Fuller v. Decatur Public Schools, 2000). The right to cross-examine and face witnesses, especially when the witnesses are fellow students, is particularly controversial. However, courts have overturned the expulsion of a student because none of the student or teacher witnesses testified at the hearing (Board of Education of Central Community v. Scionti, 2000; Colquitt v. Rich Township High School District, 1998; Nichols v. DeStefano, 2002). The right to refute evidence is fundamental to the due process standard. The right to cross-examine witnesses varies from state to state.

Boards may make decisions based on a preponderance of the evidence rather than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” requirement of criminal trials.

The district should be prepared to present data demonstrating that expulsion decisions are not based on racial criteria. For example, in Fuller v. Decatur (2000), significantly more African American students than White students faced suspension and expulsion. However, the district was able to demonstrate that African American and White students who were similarly situated received similar punishments.

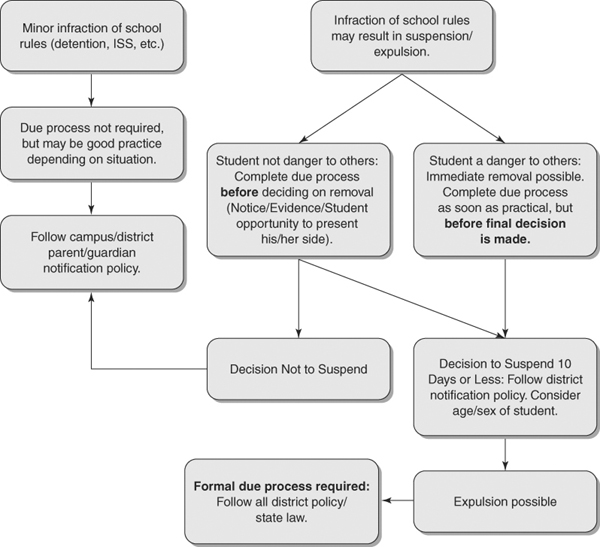

FIGURE 5-1 Procedural due process illustrated.

Corporal Punishment and Excessive Force

Corporal punishment can be defined as “the use of physical force, including hitting, slapping, spanking, paddling or the use of physical restraint or positioning which is designed to cause pain, as a disciplinary measure” (Education Commission of the States, 1998). As of 2008, 21 states (mostly in the South and Southwest) permitted the use of corporal punishment in schools (Human Rights Watch, 2008). Twenty-nine states and Washington, DC, have banned the practice. In states where the decision to use corporal punishment is delegated to the local school board, many state school board associations recommend finding alternative means of discipline. Many school districts have taken such action. In fact, 95 of the largest school districts in the country have banned corporal punishment, including Houston, Dallas, and Memphis (Human Rights Watch, 2008). In addition, states that allow corporal punishment either establish guidelines or require local boards to establish guidelines for administering physical punishment.

The legality of corporal punishment was considered by the U.S. Supreme Court in Ingraham v. Wright (1977). The parents of two students in Dade County, Florida, brought suit under USC 42 Section 1982 alleging a violation of their Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment and of their Fourteenth Amendment rights to a hearing before being deprived of property and liberty interest. The Court ruled that the Eighth Amendment protection applied only to those individuals convicted of a crime and not to public school children. Thus, juveniles in a detention center may bring suit for physical battery, but public school children may not (Roy, 2001, citing Nelson v. Heyne, 1974). In considering the Fourteenth Amendment claims, the Court recognized a liberty interest, but the due process clause did not require prior notice and a hearing before disciplinary paddling of a student could take place.

Most states that allow corporal punishment provide statutory immunity for administrators and teachers who paddle students in their schools. In Mississippi, the only way to prevail in a lawsuit against an educator is if the educator’s conduct constitutes a criminal offense, or if he or she acted with a “malicious purpose” (Human Rights Watch, 2008). Texas statutes provide immunity for persons who administer corporal punishment under both criminal and civil law (Texas Education Code 22.051a). These immunity laws make it very difficult for parents to pursue legal action when their children are injured or subjected to corporal punishment against parental wishes (Human Rights Watch, 2008).

In states where corporal punishment is legal, most federal circuits utilize a “shocks the conscience” standard when considering cases that involve outrageous conduct or physical contact between school personnel and students. The “shocks the conscience” standard is also typically applied in a variety of cases where students are injured by the actions of school officials (see Golden v. Anders, 2003, and Harris v. Robinson, 2001, as examples). Most courts set the “shocks the conscience” standard quite high by considering primarily the intent or lack of intent on the part of school personnel to cause harm. For example, the Third Circuit Court crafted four elements to consider when applying the “shocks the conscience” test: (1) Was there a pedagogical justification for the use of force? (2) Was the force utilized excessive to meet the legitimate objective in the situation? (3) Was the force applied in a good-faith effort to maintain or restore discipline, or maliciously and sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm? (4) Was there a serious injury? (Gottlieb v. Laurel Highlands School District, 2001).

In school discipline cases, the Tenth Circuit Court defines “shocks the conscience” as

whether the force applied caused injury so severe, was so disproportional to the need presented, and was so inspired by malice or sadism rather than a merely careless or unwise excess of zeal that it amounted to a brutal and inhumane abuse of official power literally shocking to the conscience.

(Garcia v. Miera, 1987)

The Eighth Circuit Court has established the following guidelines in considering whether or not the administering of corporal punishment shocks the consciences: (1) the need for the use of corporal punishment, (2) the relationship between the need for the punishment and the amount or severity of the punishment, (3) the extent of the injury inflicted, and (4) whether the punishment was administered in good-faith effort or done in a malicious and sadistic manner for the purpose of causing harm (Wise v. Pea Ridge, 1988).

Based on these definitions, it may be difficult for school personnel to shock the conscience of many federal courts, but not all behaviors are protected. For example, the Eleventh Circuit Court held that the actions of a Green County, Alabama, principal who struck a 13-year-old boy with a metal cane in the head, ribs, and back with enough force to cause a large knot on his head and migraine headaches “obviously” rise to a level that shocks the conscience (Kirkland v. Greene, 2003). A female high school student became quite unruly, profane, and refused to leave a classroom area (Nicol v. Auburn-Washburn School District, 2002). When a school security guard was summoned, he allegedly pushed the girl into a file cabinet, shoved her into another student, grabbed her in a head lock, and “pinned” her “up against [a] wall.” Using the standards established in Harris v. Robinson (2001), the Tenth Circuit Court found that a reasonable jury could find that the actions of the security guard shock the conscience, thus violating the student’s substantive due process rights.

Reaching a similar conclusion, the Second Circuit Court found the actions of a physical education teacher who grabbed a junior high school student by the throat, lifted him off the ground by his neck, dragged him across the gym floor, slammed the back of the student’s head against the bleachers four times, and rammed the student’s forehead into a metal fuse box to be “conscience-shocking” (Johnson v. Newburgh School District, 2001). The court used the following criteria to determine conscience-shocking actions: (1) Is the conduct maliciously and sadistically employed in the absence of a discernible government interest? (2) Is the conduct of a kind likely to produce substantial injury? In this particular case, the court had little difficulty answering yes to both of these criteria.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Follow school district policy and state law regarding the use—or non-use—of corporal punishment.

Search for alternatives in states (and districts) that allow corporal punishment. Sanctioning physical force and the intentional infliction of pain on students may create conditions that could easily escalate to “conscience-shocking” behavior.

Investigate any incidents of physical force by faculty. For example, the physical education teacher in Johnson v. Newburgh (2001) had previously assaulted four other students (mostly African American). Letting this type of teacher-as-bully behavior continue unchallenged is inexcusable.

Develop memoranda of understanding between the district and law enforcement regarding the role of school resource officers and the standards for review of behaviors that may not be appropriate in district schools.

Student Suspension or Expulsion for Off-Campus Behavior

Several states have passed laws allowing school districts to suspend or deny admission to students charged or convicted of serious crimes committed anywhere. For example, Missouri state law provides that no pupil shall be readmitted or enrolled to a regular program of instruction if the student has been convicted, charged with, or adjudicated to have committed a felony (RSM0 167.171.3). Many other states have similar laws that allow school districts to expel or refuse to admit students charged or convicted of serious crimes anywhere.

Courts are generally supportive of school officials’ authority to develop and enforce reasonable rules for student conduct on school grounds and at school-sponsored activities, field trips, and events. However, school authority becomes more tenuous when students break school rules off school grounds. Consequently, most courts require a link between the off-campus behavior and disruption to the school environment (see Kyle P. Parker et al. v. Board of Education of the Town of Thomaston, 1998; Student Alpha ID Number Guiza v. The School Board of Volusia County, Florida, 1993).

Zirkel (2003a) and the National School Boards Association’s Council of School Attorneys (2003) provide the following guidelines pertaining to the discipline of students for off-campus behavior:

Follow all state laws regarding the suspension or expulsion of students charged or convicted of crimes off-campus. These laws do not require a link to on-campus disruption.

Make clear to students and parents that accountability for proper behavior may extend beyond the schoolhouse gate when misbehavior occurs on school buses or at school-sponsored off-campus activities. Students and parents should be aware that students may be disciplined for conduct that starts at school and then extends off-campus. This is especially true when the behavior involves violence, gang activities, or drug sales (Zirkel, 2003a).

Discipline for off-campus behavior should be supported by a link between the behavior and disruption at school. In other words, regardless of how reprehensible the behavior may be, a relationship to the behavior and disruption in the school should be established before taking disciplinary action (National School Boards Association’s Council of School Attorneys, 2003).

Be sure that there is sufficient evidence to support disciplinary decisions. Avoid overreacting when considering student misconduct off-campus. Be sure to follow state and school district procedural due process requirements when suspensions or expulsions are considered for off-campus conduct (Zirkel, 2003a).

Follow all state laws that prohibit the enrollment or readmittance of students convicted or charged of certain crimes regardless of location.

If the student in question is classified as disabled under IDEA and/or Section, all procedural safeguards and requirements under these statutes are in force (Zirkel, 2003a).

Follow all state law reporting requirements to law enforcement when suspending or expelling students for offenses that are classified as felonies under state law.

Extracurricular Activities and Title IX

Title IX is part of the Education Amendments of 1972. It is designed to protect students from being denied the benefits of any educational program or activity because of sex. Title IX applies to admissions, recruiting, course offerings, harassment based on sex, physical education, educational programs and activities, and employment. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is responsible for the enforcement of Title IX. OCR prefers that claims be settled in a peaceful manner without referring issues to the Department of Justice (“Secretary’s Commission,” 2002).

The Title IX regulations issued by the U.S. Department of Education in 1975 require equal athletic opportunities for males and females. Title IX is designed to protect all students. However, because females have been historically underrepresented in secondary school cocurricular activities, the primary focus, and thus one of the more visible impacts, of Title IX athletic enforcement has been improving opportunities for female participation in school-sponsored cocurricular activities at the P–12 level.

Although primarily designed for intercollegiate athletics, the regulations apply equally to secondary schools that accept federal money. In 1979, the U.S. Department of Education developed the following three-pronged test that provides guidance on the application of Title IX to athletics. A school may demonstrate compliance by meeting any one of the three parts:

The school provides opportunities for males and females in numbers that are substantially proportionate to respective enrollments; or

The school can demonstrate a history and continuing practice of program expansion that is responsive to the developing interest and abilities of the members of the sex that is underrepresented among athletes; or

The school can show that the interest and abilities of the members of that sex have been fully and effectively accommodated by the present program (“Secretary’s Commission,” 2002).

Currently this test applies only to colleges and universities. However, a federal district court in California held that a school district violated this test. First, the court concluded that the district did not provide girls with athletic opportunities substantially proportionate to their enrollment in the school. Second, the court found that the district failed to show a history and continuing practice of program expansion proportionate with the interest and abilities of female students, and the district had failed to fully and effectively accommodate female athletes’ interest (Ollier v. Sweetwater High School District, 2009).

At least two courts have considered the question of whether or not Title IX applies when girls’ secondary school sports such as basketball, volleyball, and softball are played during a “non-traditional” season. For example, boys’ and girls’ basketball are a traditional winter sport and girls’ volleyball is a traditional fall sport. The federal district court in Michigan considered this question when the Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA) scheduled several girls’ sports in non-traditional seasons (Communities for Equity v. Michigan High School Athletic Association, 2001). The court held that this type of scheduling of girls’ sports violated the Equal Protection Clause, Title IX, and Michigan state law. Particularly telling in this case was a finding by the court that girls’ basketball was originally scheduled in a non-traditional season to “avoid inconveniencing the boys’ basketball team.” A similar case in New York considered decisions by school districts in a region of the state to schedule certain girls’ sports during non-traditional seasons (McCormick v. the School District of Mamaroneck and the School District of Pelham, 2004). The Second Circuit Court had little problem affirming a trial court ruling that this practice by local school districts is in violation of Title IX.

Title IX prohibits retaliation for reporting potential violations. This protection now extends to coaches and other adults who work with PK–12 public school athletic programs. The U.S. Supreme Court recently held that Title IX’s private right of action encompasses claims of retaliation against an individual (in this case a girls’ basketball coach) after he complained about sex discrimination in the school’s athletic program (Roderick Jackson v. Birmingham Board of Education, 2005). Roderick Jackson, the girls’ basketball coach, complained unsuccessfully to his supervisors about discrepancies in equipment and facilities. He then received negative work evaluations and was ultimately removed as the girls’ coach. It is important to note that the Court did not hold that Coach Jackson was dismissed from his coaching position in retaliation for his complaints, only that he is entitled to offer evidence to support his claim of retaliation.

Interscholastic athletics are not generally governed by state or federal statute, but rather by a state activity association. The Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association (TSSAA) serves as a typical illustration. Founded in 1925, TSSAA is a voluntary association composed of member secondary schools in Tennessee. A Board of Control consisting of nine board members elected by the member schools governs the Association. Changes to the TSSAA constitution and bylaws are possible only by a majority vote of member schools. Funding for the association is derived primarily from state tournament revenues and member fees. Activity associations have not traditionally received state funding and have not been considered state actors by the courts. This is an important point. As a state actor, associations would be subject to the U.S. Constitution, and association bylaws would be open to judicial review. In Brentwood Academy v. TSSAA (2001), the U.S. Supreme Court considered just such a question. The Brentwood case involved the First Amendment rights of private-school (Brentwood Academy) coaches to communicate with and recruit student athletes to their school. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the association is a state actor because of the pervasive entwinement of state school officials in the structure of the association (Brentwood v. TSSAA, 2001).

Participation in interscholastic activities has traditionally been considered a privilege, and students have not had the same property and liberty interest in athletics or other extracurricular activities as they do in access to the general curriculum. However, some due process rights could conceivably be afforded to student athletes in light of the Brentwood decision. The Eighth Circuit Court implicitly acknowledged a senior softball player’s right to due process before being dismissed from the team for missing a game. The coach announced to the team that the offending player was expelled from the team before ascertaining the player’s side of the story. However, the court found that because the superintendent, principal, and coach met soon afterward with the player and her parents, the due process requirement of a hearing had been met by the district (Wooten v. Pleasant Hope R-VI School District, 2001). At least some school-district attorneys advise against establishing the practice of providing some due process rights before dismissing students from extracurricular activities. However, the rudimentary due process rights outlined in Goss do not seem burdensome when applied to extracurricular participation.

Another area of potential litigation includes student athlete eligibility for college sports. In order to be awarded athletic scholarships and compete at the intercollegiate level, student athletes must meet certain guidelines established by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). Included in these guidelines are “core curricular” course requirements that students must complete in order to be eligible for scholarships and participation. All high schools are required to submit to the NCAA Clearinghouse a list of courses for approval. The Clearinghouse checks transcripts of potential college athletes to certify eligibility. Several incidents of high school counselors or principals failing to provide accurate lists to the Clearinghouse have resulted in student athletes being declared ineligible. These incidents have naturally resulted in several lawsuits against high school principals or counselors. In general, courts have granted summary judgment for the school district and have not held individual school employees accountable for these oversights (Abbott, 2002).

Linking to Practice

Do:

Annually evaluate the opportunities for and treatment of boys’ and girls’ extracurricular activities. For example, examine budgets, travel allotments, schedules, funding for uniforms and equipment, and equity of facility use.

Both Title IX and the ISLLC standards require an affirmative response to any inequalities.

Reassignment of coaches should be made for reasons other than in retaliation for complaining about Title IX violations.

Provide training for athletic directors, coaches, band and choir directors, and other sponsors regarding school extracurricular policy and applicable state association rules.

If a student is facing dismissal from a state association–sponsored activity, afford reasonable opportunities for rudimentary procedural due process (the student is informed of the reasons, has a chance to tell his/her side of the story, and, if denying the allegation, is given an explanation of the evidence) before a final decision is made. This precaution appears not to be common practice. However, an ounce of prevention almost always makes decisions more defensible and should increase the chances of summary judgment should a legal challenge occur. This level of protection is not necessary in cases of reasonable punishments such as extra running, benching, or apologies to the team.

Encourage or require coaches and sponsors to meet with the parents of students involved in extracurricular activities. Rules for participation should be clearly outlined, should not be vague or overbroad, and should be related to the activity. Explain rules, expectations of participants, and reasons for possible dismissal from the activity.

Encourage parents to contact coaches or sponsors if there is any question regarding rules, procedures, or punishments.

Know the NCAA Clearinghouse rules. Clearly mark “approved” courses in student curriculum guides or other documents students and parents use to make curricular decisions.

Invite parents to meetings with counselors, coaches, and band and choir directors to discuss the Clearinghouse rules and the courses approved by the campus or district.

Title IX and Pregnancy

Title IX prohibits discrimination based on a student’s actual or potential parental, family, or marital status that treats students differently on the basis of sex. Section of Title IX provides guidance on the treatment of pregnant students. The following guidelines apply to most public K–12 schools.

Schools may not discriminate or exclude any student from an educational program or activity, including any class or extracurricular activity, on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, false pregnancy, termination of pregnancy, or recovery, unless the student requests voluntarily to participate in separate programs.

It is permissible (and possibly advisable) to require a student to obtain a certification from a physician that the student is physically and emotionally able to continue participation so long as such a certification is similarly required of all students for other physical or emotional conditions.

Schools must treat pregnancy, childbirth, false pregnancy, termination of pregnancy, and recovery in the same manner and under the same policies as any other temporary disability.

Schools shall treat these conditions as a justification for a leave of absence for so long a period as is deemed medically necessary by the student’s physician. After this time period the student shall be reinstated to the status which she held when the leave began.

Summary

Parents, students, community members, legislators, and educators do seem to agree on at least one thing: Safe and orderly schools are important. School leaders are empowered to achieve this safety and order by a wide variety of laws and policies at the national, state, and local levels. At the other end of the spectrum, students are required to relinquish many of the rights they have as citizens once they cross onto school grounds. In addition, students can be held accountable by school authorities for some acts outside the school that create disruption in the school. However, students do not check all of their rights at the schoolhouse gate. Interestingly, those individuals charged with protecting the limited rights of students are the very people who have the most authority to violate them. Effective school leaders understand the legal and ethical obligation to provide for a safe and orderly school, protect the rights of students, understand the need for a positive school culture based on social cooperation, and engage in honest interactions with students, parents, and others. Finding this balance may well be one of the biggest challenges future school leaders at all levels will face.

Connecting Standards to Practice

Bad Boys

Riverboat High School Senior Kyle Lacy could be witty, smart, charming, and exasperating—usually all at the same time. In early October, high school principal Tara Hills suspended Kyle for 3 days for being disrespectful to his Senior English teacher, John Mills. While on suspension, a state trooper found 2 ounces of marijuana hidden in the trunk of Kyle’s car during a routine traffic stop. Kyle was charged with possession of marijuana and possession of drug paraphernalia.

Riverboat High School students were notified at the beginning of school that they would be held accountable for out-of-school conduct that has “some impact on what happens in school.” Sharon Grey had in fact used this rule a few times when students were involved in some out-of-school conduct that created a problem at school. Current high school principal Tara Hills suspended Kyle for an additional 5 days for his drug possession arrest. Now, she was being pressured by several faculty members to make an example of Kyle and recommend that he be expelled for the remainder of the semester and banned from extracurricular activities for the remainder of the school year. Several teachers had approached Tara expressing their concern that failure to expel Kyle would make a sham of school rules. They also cited disruption of the educational process by noting that Kyle’s younger brother, a Riverboat sophomore, was in the car at the time of the stop. Tara had overheard several students talking about Kyle’s arrest, and the subject had apparently come up in some classes. She had stopped to listen during her scheduled classroom visits, and some of the discussion about the wisdom of legalizing marijuana had become spirited. But she had not noticed a groundswell of support for Kyle or any more classroom banter regarding recent events than usual.

Question

Argue for or against the expulsion of Kyle Lacy for the remainder of the semester. Clarify the legal question. Cite ISLLC standards, legal guidelines (i.e., procedural and substantive due process, off-campus behavior, and school discipline), and the idea of a well-ordered school to justify your answer. Write a letter or memorandum to the superintendent or school board president outlining your response to the problem of Kyle Lacy.