How might you apply one of the three sociological perspectives to the ideas and experiences presented in this documentary? (using one or more of the Learning Resources) Ensure to read (or listen to) "

World Religions.

Cite: Wienclaw, R. A. (2013a). World religions. Research Starters: Sociology.

Authors: Wienclaw, Ruth A.

Source:Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2019. 7p.

Document Type: Article

Subject Terms: Religions

Abstract:

To understand the way people act toward each other, both as individuals and as societies, it is often helpful to understand the religious underpinnings that inform their beliefs and actions. The belongingness that arises from identifying with a religious group has shaped societies and political actions throughout human history. Of world religions today, Christianity and Islam both have roots in the monotheistic beliefs of Judaism. These three major world religions, however, disagree strongly on core tenets of their faiths. Hinduism and Buddhism are other major world religions that are often more tolerant of other beliefs. There are many other belief systems in the world today, ranging from those that see the spiritual in everything around them to those that deny the existence of a higher power or do not believe that such existence can ever be proved. Social scientists study the similarities and differences among major world religions in order to better understand how these belief systems affect societies, cultures, and interactions with others of different beliefs.

Full Text

To understand the way people act toward each other, both as individuals and as societies, it is often helpful to understand the religious underpinnings that inform their beliefs and actions. The belongingness that arises from identifying with a religious group has shaped societies and political actions throughout human history. Of world religions today, Christianity and Islam both have roots in the monotheistic beliefs of Judaism. These three major world religions, however, disagree strongly on core tenets of their faiths. Hinduism and Buddhism are other major world religions that are often more tolerant of other beliefs. There are many other belief systems in the world today, ranging from those that see the spiritual in everything around them to those that deny the existence of a higher power or do not believe that such existence can ever be proved. Social scientists study the similarities and differences among major world religions in order to better understand how these belief systems affect societies, cultures, and interactions with others of different beliefs.

Religions are institutional systems grounded in the belief in and reverence for a supernatural power or powers considered to have created and to govern the universe. One's faith informs not only one's personal belief system, but also one's actions in the world. Religions often inform one's ethical and moral belief systems and how one interacts with other people or the greater environment. For many people, religious identity (or lack thereof) also increases one's feelings of association and belongingness within a group composed of other adherents to the same beliefs. This belongingness not only fulfills a basic human need, but also has political and social ramifications. For example, in the United States in the early twenty-first century, the conservative Christian right has become a significant voting bloc that may influence politicians and governments to create and enforce laws that conform to their religious beliefs. This belongingness can lead to an "us-them" mentality between different groups, resulting in political sanctions, terrorism, and wars.

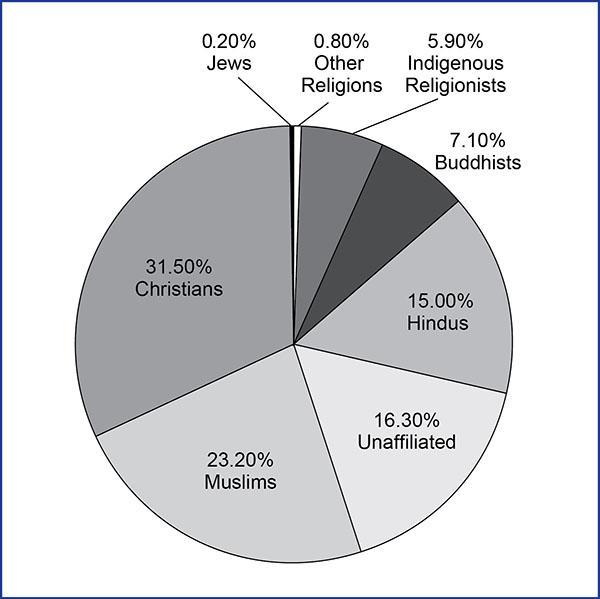

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam are only three of a large variety of religions and sects that can be found around the world. In general, most countries have dominant religions. One is more likely than not to encounter dissenting or alternative views when discussing religion. There is a great range of religious diversity across the planet not only based on belief systems but also regarding the number of adherents, ranging in the billions for Christianity and Islam to the fewer than a million for Unitarian Universalism and Scientology. Figure 1 summarizes the percentage of adherents to various religions across the globe.

Figure 1: Worldwide Percentage of Adherents by Religion (2010)

Figure 1: Worldwide Percentage of Adherents by Religion (2010)

The following sections briefly discuss some of the major belief systems and representative religions within each group. There are, of course, other religions in the world. The following discussions are not meant to be a comprehensive review, but to give the reader the salient points that differentiate religions.

Major Monotheistic Religions

Three of the major religions of the world are monotheistic (i.e., believe in one god) and trace their roots back to the patriarch Abraham: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Although there are commonalities between these religions, they are typically better defined by their differences. Far from being minor (as may appear at first glance to an outsider), to a great extent, these differences define the identities of these groups and have served as the basis for conflicts and wars.

Judaism

Judaism is the earliest of these three religions. This monotheistic religion traces its roots to the ancient Hebrews and Israelites. The spiritual and ethical principles of Judaism are embodied primarily in the Hebrew Bible (also called the Old Testament by Christians) and the Talmud, a collection of ancient rabbinic writings that form the basis of religious authority for orthodox Jews.

Although the story of humanity as described in the Hebrew Bible goes back further, the history of Judaism arguably traces back to God's promise to the ancient patriarch Abram (later called Abraham) that he would make of him the father of many nations. The Hebrews called God "YHWH," a name that they did not pronounce out of respect to the supreme being. YHWH's promise to Abraham included his descendents, Isaac, Jacob, and subsequently all the Jews. One of Jacob's sons, Joseph, was subsequently sold into slavery in Egypt, where he rose to power under the pharaoh. During a time of famine, Joseph's 11 brothers came to Egypt in search of food, were reunited with their brother, and stayed. According to the narrative in the Hebrew Bible, their descendents, the Israelites, were eventually enslaved by the Egyptians and then led to freedom by Moses following a series of plagues and the death of the firstborn children of the Egyptians. Jews still commemorate this landmark event by the celebration of Passover.

In the twelfth century CE, Moses Maimonides condensed the beliefs of Judaism into a creed. Observant Jews live according to the tenets of the Hebrew Bible as well as the doctrines of the Talmud, a body of rabbinical law tradition. Judaism can be further broken down into several subcategories, including Orthodox, Ultraorthodox, Reformed, and Conservative Judaism.

Christianity

One of the sticking points between Judaism and the other two major monotheistic religions is the concept of the messiah. The Hebrew term messiah basically means "the anointed one" (christos, or Christ, in Greek). This ever-anticipated figure in Judaism is expected to bring salvation for God's people (i.e., the Jews) and usher in the Kingdom of God. It is at this point that Christianity and Judaism differ. In its beginnings in the first century CE, Christianity was considered a sect of Judaism that differed from the main body of adherents by their belief that Jesus was not only the expected messiah, or Christ, but also the son of God. Because of this major doctrinal difference, Christians in the first century systematically distanced themselves from the Jews to become a new religion. The belief that Jesus was the expected messiah who came in fulfillment of prophecy, of course, was and is considered heresy by the Jews.

According to the Apostles' Creed, which is still cited by many Christians as a fundamental doctrinal statement, Christians believe in "God the Father Almighty," creator of both heaven and earth. At this point, both Judaism and Christianity agree. It is at the next statement, however, that these two major monotheistic religions diverge. The Apostles' Creed goes on to say that Jesus Christ is God's only son and was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary. Summarizing the story of the Gospels, the creed goes on to say that Jesus suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. After his death, the creed states that Jesus descended into hell, rose from the dead on the third day, and ascended into heaven, where he sits at the right hand of the creator, God the Father, and will judge both the living and the dead. Due to various internal disagreements over the past 2,000 years, Christianity can be further broken down into the Eastern (or Orthodox) Church and the Western Church, comprising the Roman Catholic Church and numerous Protestant denominations.

It is on the doctrine of the person and substance of Jesus Christ that Christians and Jews differ. Both religions are monotheistic. However, rather than merely believing in God the Creator, Christians believe in the Trinity, or the Godhead of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit believed to be "three persons in one." In addition, Christians believe that the New Testament is a revelation from God and that it carries as much weight as the Hebrew Bible, a view Jews do not hold. However, based on the teachings of the Christian New Testament itself, most Christians believe that there will be no further body of revelation from God. It is at this point at which the teachings of Islam deviate from those of Christianity.

Islam

Islam is also a monotheistic religion tracing its roots back to Abraham. As a religion, Islam was founded around 600 CE. The spiritual and ethical principles of Islam are embodied primarily in the Quran. Muslims (the adherents of Islam) believe in Allah to be the sole deity and Mohammad his last and chief prophet. Although believing in the historical Jesus of the Christians, Muslims believe that he was only one in a long line of prophets tracing back through the Hebrew Bible and continuing after Jesus through Mohammed, the greatest in the line of prophets. Because Muslims do not believe that Jesus was God, they do not believe in the doctrine of the Trinity.

Although like Judaism and Christianity, Islam traces its origins back to Abraham, a history of Islam actually starts around the turn of the seventh century and the Prophet Mohammed. As he grew older, Mohammed rejected the polytheism that was the predominant religion in his culture and came to believe in only one god, Allah. At the age of 40, Mohammed had his first vision. Mohammed's revelations are written down in what has come to be known as the Quran. At first, Mohammed was unsure as to the source of these visions. However, his wife encouraged him to believe that they were revelations from God. After Mohammed's death, Islam separated into several sects as a result of various controversies. One major group is the Sunnis. This orthodox sect accepts the Quran, Islamic traditions, and the four bases of Islamic law. The majority of Muslims are Sunnis. The Shi'a, another major Islamic sect, follows the teachings of Ali, a martyred adherent of early Islam. Part of the Shi'a controversy revolves around the fact that some Muslims believe that only direct descendents of Mohammed could be legitimate caliphs and be given first place in the leadership of Islam. Ali, however, was not of this line. Most of the Muslims in Iran are Shi'a. Another major Islamic sect is the Sufis. This sect of Islamic mystics arose in response to orthodox Islam and often with the secular views of some early Islamic leaders. Probably the best known of the Sufi orders is the Dervishes (i.e., "the whirling Dervishes").

Major Nonmonotheistic Religions Hinduism

Despite their familiarity in the West, monotheistic religions are not the only major religions of the world. In fact, worldwide, Hinduism had more adherents than Judaism or any other world religion with the exception of Christianity and Islam, as of 2010, according to the Pew Research Center (See Figure 1). Hinduism is a diverse, polytheistic religion native to India that comprises various religious, philosophical, and social doctrines including dharma (the obligation to fulfill one's duty), pantheism (equation of God with the forces and laws of the created universe), reincarnation (the successive rebirth of a soul in a new body in a continuing cycle of progressive perfection or salvation), karma (total effect of an individual's actions and conduct in successive reincarnations), and nirvana (the final state that transcends suffering and karma). The practice of Hinduism includes various ritual and social observances, often including mystical contemplation and asceticism.

Hinduism has a rich and complex history. In fact, it may be better considered as a family of religions rather than a single unified religion. As opposed to the major monotheistic religions discussed above, Hinduism is a universal religion in that it sees sameness in all religions rather than stressing the diversity in them. As a result, Hinduism is tolerant of other religions. The voluminous Hindu scriptures were written over a period of two millennia starting at 1400 BCE. The oldest of the scriptures is called the Vedas, which literally means "wisdom" or "knowledge." The Vedas contain various hymns, prayers, and rituals that were composed over the first millennium of Hinduism. Another part of the Hindu scriptures is the Upanishads. These are a collection of speculative treatises composed between 800 and 600 BCE. The content of the Upanishads marks a shift in emphasis from sacrifice and magic to mystical ideas about humanity in the universe, in particular the eternal Brahman (the basis of all reality) and the atman (the self or the soul). The Upanishads are said to have a great influence on Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. The Ramayana comprises one of two major epic tales of India. This work describes the life of Rama, a righteous king who was the incarnation of the god Vishnu. The second epic, the Mahabharata, is the story of the deeds of the Aryan clans. Included in this work is the Bhagavad-Gita ("Song of the Blessed Lord"). The Puranas comprise a collection of legends about gods, goddesses, demons, and ancestors.

There are three ways to view the concept of salvation in Hinduism. The way of works (karma marga) is the path of salvation through religious duty. This path to salvation includes performing prescribed ceremonies, duties, and religious rites. It is believed that performing these activities can add favorable karma to one's merit. The second path to salvation is the way of knowledge (jnana marga). The philosophy underlying this approach to salvation is that human suffering is caused by ignorance and that human nature is at the root of humanity's problems. According to Hinduism, however, this is an error because humanity is not a separate and real entity. Rather, the only real entity is Brahman. Humanity, therefore, is part of this whole. Similarly, it is believed that this illusion is what causes one to continue to be chained to the wheel of birth, death, and rebirth. The way of knowledge has particular appeal to intellectuals who are willing to go through the prescribed steps. The third approach to salvation in Hinduism is the way of devotion (bhakti marga). The way of devotion requires devotion to a deity through public and private worship. Further, the way of devotion requires that this attitude be extrapolated to human relationships through love of family, love of one's master, etc.

Buddhism

Another major world religion is Buddhism. Although Buddhism is found throughout eastern and central Asia, it originated in India about 500 BCE. The impetus for the beginning of the Buddhist belief system was disillusionment with various beliefs of Hinduism, including the caste system and the belief in an endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, who was later deified by his disciples, was significantly affected by several encounters in his early life. The first of these was the sight of an old man. The sight was unusual, for the old and infirm had been ordered at that time to stay indoors. When Siddhartha Gautama asked what had happened to the man, he was told that it was only old age and that it would happen to everyone one day. The second encounter that affected Siddhartha Gautama's outlook was the sight of an ill man. Again, he was told that all people were vulnerable to sickness. The sight of a funeral procession again affected him when he was told that death comes to all people. The final sight was of a monk who was begging for food. The look of tranquility on the man's face led Siddhartha Gautama to desire the same life for himself. Although a prince, Siddhartha Gautama left the palace that night to seek enlightenment. One day as he was meditating under a tree, he reached the highest degree of god-consciousness (nirvana). At this point in his story, Siddhartha Gautama becomes known as the Buddha ("enlightened one").

The essence of Buddhism can be summed up by three objectives: cease from all sin, acquire virtue, and purify the heart. Buddhism is based on the philosophy that suffering is a part of life but that one can be liberated from it through moral and mental self-purification. There are a number of fundamental beliefs in Buddhism. First, Buddhists are to show tolerance, forbearance, and brotherly love to all people without distinction as well as kindness toward all animals. The founding truths of Buddhism are founded on the natural world. Buddhists also believe that ignorance fosters desire as well as the belief that rebirth is necessary. Perfection, however, can be obtained by meditation once one learns to let go of the desire to live. As with Hinduism, Buddhism includes the concept of karma. Obstacles to obtaining good karma can be removed by not killing, stealing, indulging in forbidden sexual pleasure, lying, and drinking alcohol or taking drugs.

Other Approaches

There are also many primal/indigenous religions across the world. This term comprises a general category of religious practice and belief usually found in primitive societies. Primal/indigenous religions are based on beliefs, superstitions, and rituals that are passed on from one generation to the next within a specific culture. Primal/indigenous religions include animism (attribution of conscious life to nature or natural objects) and shamanism (animistic religion in which mediation between the visible and spirit worlds is mediated by shamans who practice magic for purposes of healing, divination, and control over natural events). Some examples of primal/indigenous approaches to religion include the religious beliefs of the North American natives and of traditional African tribes.

Agnosticism & Atheism

There is a vast array across the globe of other religions with fewer adherents, each with its own belief system. However, not everyone believes. Although most people in the world ascribe to various religious belief systems, a significant number do not. Of these, there are those who are open to the possibility of a higher power and those who are not. Agnostics believe that any ultimate reality is unknown and unknowable. From a religious point of view, therefore, agnostics do not confirm or deny the existence of God and further believe that no proof of God's existence can exist. Agnostics are distinguished from atheists, who actively disbelieve in or deny the existence of any higher power. As with religious beliefs, these belief systems also affect the way that people act. Nonbelievers represent a significant proportion of individuals in twenty-first-century postmodern society. Like their religious counterparts, the beliefs (or lack thereof) of nonbelievers also help shape society.

Applications

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 by radical Islamists, schism in the Anglican and Episcopal Churches, and the unusual and often illegal activities of various sects and cults have created news headlines implicating the role of religion in these events. Religion can be the stuff of controversy with one group arguing with another over who is right and who is wrong. The attacks on the USS Cole, the World Trade Center, and the London Underground and Tavistock Square were all done in the name of religion. So, too, is the fighting of the Israelis and the Palestinians as well as the national Chinese persecution of the Falun Gong sect. Although it would be easy to think that these contemporary examples herald a disintegration of society, students of history know that they are actually chillingly reminiscent of other religion-inspired events of the past: the Crusades, the martyrdom of the early Christians, the pogroms against Jews in eastern Europe, and the conflicts between Hindus and Muslims on the Indian subcontinent, among others.

Viewpoints

Religion is an important factor in the way that individuals and groups act. Behavioral and social scientists need to understand the role of religion in causing behavior including not only disagreements over spiritual truth, but perhaps even more importantly over the ethics and mores that permeate people's lives and inform their behavior. The belief systems held by adherents of a religion are often more than a matter of personal preference. For example, the caste system of Hinduism that has traditionally permeated Indian society specifies among other things what types of jobs members of certain castes can hold. Similarly, many Middle Eastern countries are considered Islamic not only because the majority of their citizens are Muslims, but also because the very laws governing these societies are themselves Islamic in nature.

As is well illustrated by the frequent conflicts throughout history between the three major monotheistic religions, even religions that hold in common certain basic tenets may disagree violently about other core beliefs and values. Therefore, it would be inappropriate in most cases to link these together as a single group for research or theoretical purposes. Similarly, differences over beliefs even within sects and denominations of a particular religion can make categorization into a unified group ill advised. When theorizing about the theoretical underpinnings of religions or their impact on culture and society, it is extremely important to carefully and operationally define one's terms based on the differences articulated between adherents of various sects or religions. Otherwise, research results can be misleading and theories unlikely to reflect real world realities.

Religion is an important motivator not only for individual human behavior but also for the behavior of individuals within groups. One's belief system affects not only how the person acts in one-on-one situations with others, but also how adherents of one religion treat those of other religions. In some cases, this can be tolerance and acceptance. In other cases, however, it is intolerance and conflict. Many religions are not unified and have multiple belief systems even when they have common core values. In order for social science research into religion to be meaningful, researchers and theorists must carefully and operationally define the terms that they used to describe members of a religion.

Terms & Concepts

Denomination: A large group of congregations united under a common statement of faith and organized under a single legal and administrative hierarchy. Many individual congregations include the name of their denomination in the title of their church (e.g., First Baptist Church, St. Luke's Lutheran Church).

Doctrine: A principle (or body of principles) accepted or believed by a religious group.

Monotheism: The doctrine or belief in only one god.

Mysticism: A belief in the existence and experience of realities that cannot be perceptually or intellectually apprehended but that can be directly accessed through subjective experience. Because mystic realities are beyond both perception and intellect, mystics typically find it difficult or impossible to articulate their experience to others.

Operational Definition: A definition that is stated in terms that can be observed and measured.

Orthodoxy: Beliefs or teachings that are in accordance with the accepted or traditional teachings of an established faith or religion. (cf. orthodoxy)

Polytheism: The belief and worship of multiple gods.

Religion: A personal or institutional system grounded in the belief in and reverence for a supernatural power or powers considered to have created and to govern the universe.

Sect: A distinct subgroup united by common beliefs or interests within a larger group. In religion, sects typically have separated from the larger denomination.

Bibliography

Ammerman, N. T. (2010). The challenges of pluralism: Locating religion in a world of diversity. Social Compass, 57(2), 154-167. Retrieved November 7, 2013 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=51674171

Borowik, I. (2011). The changing meanings of religion: Sociological theories of religion in the perspective of the last 100 years. International Review of Sociology, 21(1), 175-189. Retrieved November 7, 2013 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=59702984

Brown, R. R., & Brown, R. (2011). The challenge of religious pluralism: The association between interfaith contact and religious pluralism. Review of Religious Research, 53(3), 323-340. Retrieved November 7, 2013 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=67364097

Bruce, S. (2011). Defining religion: A practical response. International Review of Sociology, 21(1), 107-120. Retrieved November 7, 2013 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=59702988

Goujon, A. (2014). The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(2), 446–47. Retrieved January 22, 2015, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=96408270&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Johnston, E. (2013). Mapping Religion and Spirituality in a Postsecular World. Sociology of Religion, 74(4), 549–50. Retrieved January 22, 2015, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=93066129&site=ehost-live&scope=site

McDowell, J., & Stewart, D. (1983). Handbook of today's religions. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Martin, J. P. (2005). The three monotheistic world religions and international human rights. Journal of Social Issues, 61(4), 827-845. Retrieved May 14, 2008 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=18856403&site=ehost-live.

Matthews, W. (2006). World religions. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

National and World Religion Statistics, Church Statistics, World Religions. Retrieved May 12, 2008 from: http://www.adherents.com/.

Suggested Reading

Beye, P. (2013). Religion in the context of globalization: Essays on concept, form, and political implication. Abingdon, England: Routledge. Retrieved November 7, 2013 from EBSCO online database eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=615559&site=ehost-live

Healey, S. (2005). Religion and terror: A post-9/11 analysis. International Journal on World Peace, 22(3), 3-23. Retrieved May 12, 2008 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text: http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=19754697&site=ehost-live

Lee, M. R. (2006). The religious institutional base and violent crime in rural areas. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 573-579. Retrieved May 12, 2008 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text: http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=21936858&site=ehost-live

Miles, J., Doniger, W., Lopez, D. S., & Robson, J. (2015). The Norton anthology of world religions (Vols. 1–2). New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2015.

Sharot, S. (2001). A comparative sociology of world religions: Virtuosos, priests and popular religion. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Turner, J. (2006). Contemporary religious violence: Rational reaction to the brutality of globalization. Conference Papers -- American Sociological Association, 2006 Annual Meeting, Montreal, 1-19. Retrieved May 12, 2008 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text: http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=26641956&site=ehost-live

Walsh, T. G. (2012). Religion, peace and the postsecular public sphere. International Journal on World Peace, 29(2), 35-61. Retrieved November 7, 2013 from EBSCO online database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=77369830

~~~~~~~~

Essay by Ruth A. Wienclaw, Ph.D

Dr. Ruth A. Wienclaw holds a Doctorate in Industrial/Organizational Psychology with a specialization in Organization Development from the University of Memphis. She is the owner of a small business that works with organizations in both the public and private sectors, consulting on matters of strategic planning, training, and human/systems integration.

Copyright of World Religions -- Research Starters Sociology is the property of Great Neck Publishing and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Sociological Theories of Religion: Structural Functionalism.

Cite: Wienclaw, R. A. (2013b). Sociological theories of religion: Structural functionalism. Retrieved Authors: Wienclaw, Ruth A.

Source: Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2019. 6p.

Document Type: Article

Subject Terms: Functionalism (Social sciences) Religion & sociology

Abstract:

Functionalism is a theoretical framework used in sociology that attempts to explain the nature of social order, the relationship between the various parts (structures), and their contribution to the stability of the society. Functionalists examine the functionality of each structure to determine how it contributes to the stability of society as a whole. When applied to the sociological study of religion, this approach views religion as a functional entity within society because it creates social cohesion and integration by reaffirming the bonds that people have with each other. In the functionalist view, religious rituals express the spiritual convictions of the members of the religion and help increase the belongingness of the individuals to the group. Although functionalism may be useful for explaining how religious phenomena occur, it is less useful for explaining why they occur. Similarly, it fails to explain—or even adequately define —religion as a whole.

Sociological Theories of Religion: Structural Functionalism

Functionalism is a theoretical framework used in sociology that attempts to explain the nature of social order, the relationship between the various parts (structures), and their contribution to the stability of the society. Functionalists examine the functionality of each structure to determine how it contributes to the stability of society as a whole. When applied to the sociological study of religion, this approach views religion as a functional entity within society because it creates social cohesion and integration by reaffirming the bonds that people have with each other. In the functionalist view, religious rituals express the spiritual convictions of the members of the religion and help increase the belongingness of the individuals to the group. Although functionalism may be useful for explaining how religious phenomena occur, it is less useful for explaining why they occur. Similarly, it fails to explain—or even adequately define —religion as a whole.

Keywords Belief System; Collective Consciousness; Functionalism; Postmodernism; Religion; Ritual; Worldview

Sociology of Religion > Sociological Theories of Religion: Structural Functionalism

Overview

To make sense of the world around them, people make and revise theories in order to develop models of real world phenomena and behavior that will help them better understand and interact with others. To the extent that these models work (i.e., adequately and accurately portray the real world and the interaction of the various parts), the models are retained. To the extent that they do not work, they are revised or discarded. In the social sciences, one of the phenomena that many scientists try to explain is what makes a society stable and why change in one part does not result in anarchy. Functionalism (also called structural functionalism) is a theoretical framework used in sociology that attempts to explain the nature of social order, the relationship between the various parts (structures), and their contribution to the stability of the society by examining the functionality of each part to determine how it contributes to the stability of society as a whole. Using this framework, structures are analyzed in terms of their functions or the role that each plays in maintaining or altering a society. Structural functionalism attempts to explain the highly cohesive nature of societies with unified by a belief system and the relatively less cohesive nature of those societies that are not (i.e., are more diffuse or have competing belief systems).

When applied to the sociological study of religion by such theorists as Émile Durkheim, structural functionalism views religion as a functional entity within society. Religion creates social cohesion and integration by reaffirming the bonds that people have with each other. In the functionalist view, religious rituals express the spiritual convictions of the members of the religion and help increase the belongingness of the individuals to the group. Examples of such religious rituals include Christians' pilgrimages to the holy land or Muslims' pilgrimages to Mecca. Religious rituals occur in smaller ways as well. For example, the daily prayers and cleansing rituals of Islam or the forms and rites of Sunday morning worship in Christian churches serve to unite those who enter into the forms and rituals and separate them from others who do not. According to Durkheim, these reminders of religious belongingness create, express, and reinforce the cohesion of a social group.

According to functionalism, individuals who perform a religious ritual or practice do so not only for spiritual reasons, but also to express their identification with the religion and its adherents as a whole. Further, religious rituals serve to remind individuals of the tenets of the religion. For example, in part, the daily Islamic prayers remind one of the transcendence of God while Christian participation in the Eucharist (Communion) reminds one of the price of salvation. Durkheim further believed that one of the roles of religion was to confer identity on an individual. He believed that religion allowed individuals to transcend their individual identities and, instead, identify as part of a larger group. The wearing of religious symbols in (e.g., the yarmulke of Judaism, the cross of Christianity, or the hijab of Islam), for example, declares to the world one's religious identity and connection with others of similar religious beliefs. According to the functionalist perspective, religion helps establish a collective consciousness (common beliefs of a group or society that give members a sense of belongingness) that helps bind individuals together.

According to the functionalist perspective, there is another component to religion: emotion. Religion allows both the expression and control of emotion which in turn enables the attachment of individuals to one another and thereby increases the cohesiveness of the group as well as reinforces the norms of the group. The expression of emotion can be seen in such examples as the emotional displays at revival meetings or in charismatic worship. However, religious controls on emotion and its display are enforced through definitions of proper versus improper behavior and standards for legitimate behavior within society. This sets social controls that help the society to function.

Applications

Shortcomings & Criticism

Structural Functionalism & Post Modern Society

Like the sociological frameworks provided by conflict analysis, structural functionalism is an approach to studying religion from a sociological perspective that is arguably of interest primarily from a historical view. However, many contemporary theorists no longer see these approaches to be very applicable from a practical point of view. Theorists have argued over why this is true. For example, one of the difficulties with the functionalist approach as applied to religion today is that the role of religion is different in the postmodern era than it was in the modern era in which societies were viewed as totalities (Denzin, 1986). In order for postmodern theories of religion to adequately and accurately reflect the reality of the religious experience and its impact and influence on society, theorists need to work within postmodern reality and leave behind the assumptions of the modern era (such as viewing societies as totalities). This does not necessarily mean that modern work (including Durkheim's) needs to be thrown out without further thought. However, it does mean that it needs to be reevaluated within the realities of postmodern societies. It is only in this way that such theories (or any theories at all) can truly model the postmodern experience.

Eliminating the Divine

In addition, all too often social theories— including functionalism—try to take the concept of the divine out of the equation and view religions not as faith systems but as social systems despite the fact that this was neither their intent nor the reason that they attract adherents. Even during the period of modernity, these theoretical frameworks fell short. As Stark (2003) rightly points out, to leave the concept of the divine or supernatural out of the sociological theory of religion is to doom the theory to failure from the start. Yet, this is what many such historical theories do. However, as Stark goes on to argue, most religious people find the concept of God or the gods to be integral to their definition of religion.

Stark examined Durkheim's structural functionalist approach to studying religion and concluded that the omission of the concept of the divine from Durkheim's theory was in error. Structural functionalism and other early sociological theories of religion emphasized how religion was used within society while deeming the concept of gods as unimportant. For example, structural functionalism viewed the rites and rituals— rather than their underlying meaning— as the important elements of religion. In fact, Durkheim advocated that sociology pay little or no attention to the differences in the ways that people conceptualize the divine or the mysterious. Rather, Durkheim and others advocated that religion be viewed as a purely sociological phenomenon. According to Durkheim, the purpose of religion was to strengthen the ties between religious adherents and their society, with the concept of God merely being a symbol for society. In this worldview, religion becomes nothing more than a series of rites and rituals in which individuals participate. Stark maintains that focusing on the trappings of rituals and rites is in essence focusing on peripheral matters rather than attempting to understand the heart of the religious experience itself. Social scientists that do not understand these underlying concepts (e.g., the divine, spirituality) force their own worldview upon religion, ignore what they do not understand, and attempt to make sense of the rest. Perhaps most importantly, omitting such a variable from research is not in keeping with the scientific method and is unlikely to result in a theory that will adequately and accurately explain religion.

Rodney Stark's Research & Findings

Based on his views, Stark conducted research to test two conclusions: the effects of religiosity on individual morality are contingent on images of gods as conscious, morally concerned beings; and participation in religious rites and rituals will have little or no independent effect on morality. Stark analyzed data from thirty-four nations including the United States. Of the twenty-seven nations where the primary religion was Christianity, he found that the greater the importance subjects placed on the concept of God, the less likely they were to participate in activities that they believed to be immoral (e.g., buying stolen goods, failing to report their involvement in an automobile accident, smoking marijuana). These findings were consistent across Protestant and Catholic nations whether or not church attendance was high. In fact, contrary to the theory underlying many studies of religiosity (which tend to show mixed or unreplicable results), attendance at weekly church services was only weakly linked with morality. In Stark's study, it was not the outward show of religiosity that determined individuals' moral values, but their deeply held religious beliefs. Similar results were found in the analysis of data from primarily Muslim nations. The importance placed on Allah was very strongly correlated with morality, whereas attendance at mosque services was not. On the other hand, in Japan where religion is polytheistic and people believe that the gods have little interest in the morality or immorality of humans, the link between the data showed no connection between religion and moral outlooks. Similar results were found in the analysis of data obtained from China, with the exception that the more an individual prayed, the more likely the individual was to participate in immoral behavior. Stark interprets this result to reflect the nature of the Chinese gods, to whom one prays for self-centered or self-serving reasons rather than to establish and maintain a relationship as in the monotheistic religions. In general, therefore, contrary to the predictions of the structural functionalist perspective, Stark's research showed that rites and rituals have little or no effect on the universally perceived major aspect of religion: moral order. Adherents' perceptions of God or gods as conscious, powerful, beings concerned about morality and who pay attention to the lives and action of humans, however, did.

Based on these findings, Stark concluded that contrary to the theory of Durkheim and structural functionalists, rituals and rites are not the essence of religion. Further, Stark concluded that the omission of the concept of the divine from sociological theories of religion is an error. Stark goes on to point out that although the theories of Durkheim and structural functionalism have had great impact on the way that sociologists view and research religion, this is an unfortunate influence as the data do not support the theory. Stark goes on to urge theorists and researchers to include the concept of gods in the work in order to better explain the effect of religion and understand its role in society.

Contreras-Véjar's Criticism

There are other criticisms of Durkheim's theory of religion as well. Contreras-Véjar (2006) points out that Durkheim and structural functionalism fail to capture what makes religion distinctive from other social structures. Further, Contreras-Véjar concludes that it is essential that social scientists define religion if they wish to scientifically study it. As discussed by Stark, to leave essential elements out of the definition (such as the blatant rejection of the concept of the divine in much sociological work on the subject) is to guarantee that any resultant theory will not adequately or accurately describe religious phenomena or advance the theory or religion. Further, religion is not a sociological phenomenon per se, although it does have sociological implications such as its ability to effect social change. Therefore, religion cannot be studied as a purely secular, sociological phenomenon as was done by Durkheim.

Durkheim argued that individuals are tabulae rasae (blank slates) on which society inscribes various categories. In this way, individuals are the expression and product of society and, in fact, that society can be viewed without taking into account individuals at all. This may be an interesting thought and one that allows the sociologist to look "objectively" at social phenomena. However, this "objectivity" comes at a price: not truly understanding the underlying causes and influences that go to making up reality. Ignoring the data that are not convenient to one's theory does not make the resultant project more objective; it makes it less realistic. For Durkheim, individuals had their roles defined by society. This approach, however, is unable to explain the problem of individuals who break with the mold, hold different opinions, or dissent within society in a way that creates social change within a religion (e.g., the Protestant Reformation) and within society itself.

An increasing number of social scientists, philosophers, and scholars of religion question the ability of functionalism to explain religion. In fact, it has been noted that functionalism does not explain religion so, therefore, does not aid in the study of religion. Burhenn (1980) notes, however, that this may be too all encompassing a denouncement of the functionalist approach. He furthers this discussion by arguing that functional explanations are best used in determining how religious phenomena occur rather than why they occur. Burhenn notes that functional explanations typically do not meet the standard for implementing the scientific method. However, he goes on to state that functional analyses can possibly answer other questions and further our level of understanding about religious and other phenomena.

Conclusion

As applied to the sociological study of religion, functionalism views religion as a functional entity within society because it creates social cohesion and integration by reaffirming the bonds that people have with each other. Structural functionalism as laid out by Durkheim helps one understand the highly cohesive nature of societies with a unified belief system and the less cohesive nature of those societies which do not (i.e., are more diffuse or have competing belief systems). In the functionalist view, religious rituals express the spiritual convictions of the members of the religion and help increase the belongingness of the individuals to the group. However, although functionalism explains some parts of religious phenomena, it fails to explain— or even adequately define—religion as a whole. This may be due to a number of reasons including the fact that it fails to take into consideration the concept of the divine and the spiritual aspect of the religious experience. In addition, it has been observed that the functional approach is a product of modernity and, therefore, may not adequately reflect and address the realities of the postmodern experience. However, when applied properly to questions about how religious phenomena occur rather than why they do so, functionalism still may have applicability today.

Terms & Concepts

Agnostic: An individual who does not deny (or confirm) the possibility that the God may exist, yet concomitantly does not believe that proof of the existence of God can exist.

Atheist: An individual who denies the existence of God or gods.

Belief System: One's ideology (a body of ideas and belief system that reflects the social needs and aspirations of an individual, group, class, or culture) and/or worldview (broad framework of ideas and beliefs used by an individual, class, or culture to interpret the data received from the world and determine the appropriate way of interacting with the world).

Collective Consciousness: Common beliefs of a group or society that give its members a sense of belongingness.

Functionalism: A theoretical framework used in sociology that attempts to explain the nature of social order and the relationship between the various parts (structures) in society. Also investigates the contribution of these structures to the stability of the society by examining the functionality of each. Also referred to as structural functionalism.

Model: A representation of a situation, system, or subsystem. Conceptual models are mental images that describe the situation or system. Mathematical or computer models are mathematical representations of the system or situation being studied.

Mysticism: A belief in the existence and experience of realities that cannot be perceptually or intellectually apprehended but that can be directly accessed through subjective experience. Because mystic realities are beyond both perception and intellect, mystics typically find it difficult or impossible to articulate their experience to others.

Norms: Standards or patterns of behavior that are accepted as normal within the culture.

Postmodernism: A worldview beginning in the latter half of the twentieth century that questions or rejects claims of absolute certainty and objective truth.

Religion: A personal or institutional system grounded in the belief in and reverence for a supernatural power or powers considered to have created and to govern the universe.

Religiosity: The quality of being religious; the intensity and consistency of one's practice of a religion. Religiosity is measured by asking about religious beliefs, measuring membership in religious organizations, and measuring attendance at religious services. The term religiosity can also be used to refer to an excessive devotion to religion.

Ritual: An act or series of symbolic or ceremonial activities.

Scientific Method: General procedures, guidelines, assumptions, and attitudes required for the organized and systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and verification of data that can be verified and reproduced. The goal of the scientific method is to articulate or modify the laws and principles of a science. Steps in the scientific method include problem definition based on observation and review of the literature, formulation of a testable hypothesis, selection of a research design, data collection and analysis, extrapolation of conclusions, and development of ideas for further research in the area.

Social Change: The significant alteration of a society or culture over time. Social change involves social behavior patterns, interactions, institutions, and stratification systems as well as elements of culture including norms and values.

Worldview: Broad framework of ideas and beliefs used by an individual, class, or culture to interpret the data received from the world and determine the appropriate way of interacting with the world.

Bibliography

Andersen, M. L. & Taylor, H. F. (2002). Sociology: Understanding a diverse society. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Burhenn, H. (1980). Functionalism and the explanation of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 19, 350-360. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=4899169&site=ehost-live

Contreras-Véjar, Y. (2006). What is religion? An analysis of some sociological attempts to conceptualize religion. Conference Papers — American Sociological Association, Montreal, 1-20. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=26643976&site=ehost-live

Denzin, N. K. (1986). Postmodern social theory. Sociological Theory, 4, 194-204. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=15372323&site=ehost-live

Marangudakis, M. (2012). Multiple modernities and the theory of indeterminacy—On the development and theoretical foundations of the historical sociology of Shmuel N. Eisenstadt. Protosociology: An International Journal Of Interdisciplinary Research, 2, 97-25. Retrieved October 31, 2013 from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=85443963

Powell, J. L. (2012). A Short Introduction to Social Theory. Hauppauge, N.Y.: Nova Science Publishers. Retrieved October 31, 2013 from EBSCO Online Database eBook Academic Collection. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=601315&site=ehost-live

Stark, R. (2003). Why gods should matter in social science. Chronicle of Higher education, 49, B7-B9. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=9982113&site=ehost-live

Tanaka, S. (2013). Nationalization, modernization and symbolic media—Towards a comparative historical sociology of the nation-state. Historical Social Research, 38, 252-267. Retrieved October 31, 2013 from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=88102080

Suggested Reading

Appelrouth, S. A. & Edles, L. D. (2012). Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory: Text and Readings. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Balée, W. L. (2012). Inside Cultures: A New Introduction to Cultural Anthropology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Fenn, R. (1981). Religion. International Social Science Journal, 33, 285-306. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=5627399&site=ehost-live

Garrett, W. R. (1974). Troublesome transcendence: The supernatural in the scientific study of religion. Sociological Analysis, 35, 17-180. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=19233045&site=ehost-live

Robertson, R. (1985). Beyond the sociology of religion? Sociological Analysis, 46, 355-360. Retrieved May 26, 200, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=17595070&site=ehost-live

Stark, R. (2001). Gods, rituals, and the moral order. Journal for the scientific Study of Religion, 40, 619-636. Retrieved May 26, 2008, from EBSCO Online Database SocINDEX with Full Text. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=5487205&site=ehost-live

~~~~~~~~

Essay by Ruth A. Wienclaw

Dr. Ruth A. Wienclaw holds a PhD in industrial/organizational psychology with a specialization in organization development from the University of Memphis. She is the owner of a small business that works with organizations in both the public and private sectors, consulting on matters of strategic planning, training, and human/systems integration.

Copyright of Sociological Theories of Religion: Structural Functionalism -- Research Starters Sociology is the property of Great Neck Publishing and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Sociological Theories of Religion: Conflict Analysis.

Citation: Wienclaw, R. A. (2013c). Sociological theories of religion: Conflict analysis.

Authors: Wienclaw, Ruth A.

Source: Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2019. 6p.

Document Type: Article

Subject Terms: Conflict theory Religion & sociology

Abstract:

The conflict perspective is an approach to analyzing social behavior which is based on the assumption that social behavior is best explained and understood in terms of conflict or tension between competing groups. When applied to religion, conflict analysis posits that religion is a source of conflict that divides or stratifies society. Marx argued that religion is a tool which helps maintain the status quo in society by making the lower classes content with promises of great rewards in the life after death. The conflict perspective can explain many conflicts seen around the world not only throughout history, but also today. However, this approach does not adequately explain all the data of the religious experience. In reality, religion is often found to be a liberating force within society; promoting equality rather than inequality.

Sociological Theories of Religion: Conflict Analysis

The conflict perspective is an approach to analyzing social behavior which is based on the assumption that social behavior is best explained and understood in terms of conflict or tension between competing groups. When applied to religion, conflict analysis posits that religion is a source of conflict that divides or stratifies society. Marx argued that religion is a tool which helps maintain the status quo in society by making the lower classes content with promises of great rewards in the life after death. The conflict perspective can explain many conflicts seen around the world not only throughout history, but also today. However, this approach does not adequately explain all the data of the religious experience. In reality, religion is often found to be a liberating force within society; promoting equality rather than inequality.

Keywords Conflict Perspective; Ethnocentrism; Fundamentalism; Ideology; Operational Definition; Religion; Social Change; Spirituality

Sociology of Religion > Sociological Theories of Religion: Conflict Analysis

Overview

It is probably safe to assume that most adherents of religion believe that religion makes a difference in their lives. Most religions have stories of people who have changed their lives as the result of a mystical encounter. However, even more commonplace are the benefits religion offers people: a sense of meaning and peace; a feeling of belonging to a group; and a belief that a higher power is watching over them. Theologically, one may talk about the power of conversion or the intervention of God in people's lives. Sociologists, however, typically try to analyze the power of religion by taking God or other higher powers out of the equation and explaining the phenomenon of religion in purely secular terms. This approach, of course, makes certain assumptions about the validity (or invalidity) of various religious beliefs. Whether or not these assumptions are true is open to debate.

Conflict Perspective

One of the frameworks that can be applied in a sociological study of religion is conflict perspective. This approach is based on the assumption that social behavior is best explained and understood in terms of conflict or tension between competing groups. Karl Marx in particular looked at religion as a source of conflict—a divisive rather than a cohesive power within society. Marx argued that religion is a tool that helps maintain the status quo in society by making the lower classes content with promises of great rewards in the life after death. Marx is often quoted as saying that "religion is the opium of the people." He advocated that people should reject other-worldly values in order to focus on the here and now and work for rewards in this life. Marx maintained that the happiness and rewards promised by religion are merely illusions. In this view, religion helps maintain social inequality by justifying oppression and is an institution that justifies and perpetuates the ills of society. Specifically, rather than resolving conflict or curing social injustice, the conflict analysis approach views religion as the basis of intergroup conflict. Further, the inequalities and social injustices that exist in society are reflected within the religious institutions themselves (e.g., race, class, or gender stratification). Conflict analysis theorists also posit that religion provides legitimization for oppressive social conditions, thereby supporting and maintaining the status quo. Similarly, religious practices and rituals define group boundaries within society, thereby supporting an us-them mentality.

According to Marx, religion is a matter of ideology not of faith, focusing more on social needs and aspirations than on spirituality. In particular, Marx believed that religion is an ideology of the ruling class and, therefore, supported the status quo. In this approach to explaining religion, subordinate groups come to believe in the legitimacy of the social order that oppress us them by internalizing the ideology of the ruling class. Rather than supporting social change and growth, Marx believed that religion actually impedes them by encouraging lower stratum social groups to focus on the otherworldly things.

Real World Examples

Examples supportive of this theory are the stuff of today's headlines. The conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, clashes between the Jews and the Muslims in the Middle East, ethnic cleansing against Bosnian Muslims, and the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the underground at Tavistock Square in London are all examples of religious conflict. In fact, world history is full of such examples including wars, terrorism, and genocide all performed in the name of religion. All too frequently, and particularly in the more fundamentalist sects, the picture of religion is one in conflict itself: piety and contemplation on the one hand and wars and battles on the other. Part of the reason for this conflict is ethnocentrism, or the belief that one's own group is superior to other groups. Even religions that teach tolerance and share many of the same moral and ethical principles such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, can be in conflict with one another despite their commonalities. This is well illustrated by the medieval Crusades and the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. Since most religions have historically been patriarchal in nature, this us-them mentality also extends to stratification of genders, with males often being allowed positions of power and authority while women are assigned to subservient roles. This approach can also be used to explain the conflict over gay rights and ordination of gays and lesbians within many churches today.

The Hindu Caste System

Perhaps one of the best examples of religion encouraging the stratification of society is found in the Hindu caste system. This hierarchical religious system influences the social system, defining not only the manifestations of the religion, but also the jobs to which one can aspire and the resulting socioeconomic status and religious privilege of members of that caste. Within Hinduism, the highest caste is the Brahmins. Individuals in this caste are honored by all, and become priests and philosophers. Under the Brahmins, is the Kshatriya caste, the Hindu upper-middle class. Individuals in this caste are considered lower in status than the Brahmins. The Kshatriays take jobs as professionals and government officials. The next lower caste comprises the Vaisyas, who are merchants and farmers. Below them are the Sudras. The duty of members of this caste is to serve as laborers and servants to members of higher castes. Sudras are not only limited both in society in the types of jobs that they can take but also within the religion as they are barred from participating in many rituals. Dalits are traditionally viewed as polluting or “untouchable” outcastes and relegated to tasks considered too degrading or menial for caste members to perform, such as human waste removal, leatherworking, and cobbling (Rathore, 2013; Ghatak & Udogo,2012).

Applications

Women & Christianity

Social stratification occurs and affects the secular culture in many places around the world. An example in the United States is the treatment of women within the Christian Church, particularly as illustrated by the issue of whether or not women are allowed to be ordained to become priests or ministers. The biblical evidence can be interpreted to either support or prohibit the ordination of women. The New Testament states that "there is neither male nor female" (Galatians 3:28), a statement that would seem to support women's ordination. Elsewhere, however, other biblical passages make such statements as "I do not permit a woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she must be silent" (1 Timothy 2:12), a statement that would seem to prohibit it. However, there is also evidence in the Christian New Testament that women were the leaders of house churches and were ordained as deacons in the Church. Similarly, archeological evidence supports the fact that women were not only leaders in the early Church, but also were ordained both as priests and as deacons. So, even in the first century when women were typically subservient to men in most areas, the Church ordained women to the priesthood. It can be argued, in fact, that the acceptance of women as clergy was changed to reflect the secular social structure rather than being implemented from the start as a support system to maintain women in subservient positions.

Gradually, the attitude toward women in the church changed and women's ordination was no longer permitted by many denominations. For example, the Roman Catholic Church today still does not permit the ordination of women as either priests or deacons and appears unlikely to do so in the foreseeable future. However; within recent decades, some Protestant religions have permitted the ordination of women to the priesthood. American Baptists, Evangelical Lutherans, United Methodists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians all now ordain women as priests and ministers. Conflict theory would argue that this change came after the women's liberation movement in the 1960s and '70s which brought about more opportunities and greater equality for women in the workplace. In this view, the ordination of women in the church is merely a reflection of the pervading culture. Although a few women had been ordained in modern times before this movement, it was not until the 1970s that women were regularly ordained. However, the position of ordained women in the church reflects that of women outside the church.

The Glass Ceiling

Feminists often speak of the glass ceiling that women encounter in business. This expression is used to refer to the fact that in practice women often find that they cannot attain the highest level of jobs or pay within an organization while men can. This does not mean that all women are stopped at this invisible ceiling. However, many still are. Similarly, in ecclesiastical circles, ordained women talk about the "stained glass ceiling" to describe the same phenomenon in the Church. Depending on the denomination, ordained women may find that they are less able to find attractive churches or postings as compared to their male counterparts and also that they do not receive the same pay as male clergy. Further, in hierarchical denominational structures, it has been observed that it is often more difficult for women to be ordained as bishops than it was for them to be ordained to the priesthood. However, it must also be noted that it is similarly difficult for ordained men to become bishops just due to the small numbers of openings. It should also be noted that a woman has recently been elected to be primate of the Episcopal Church, the American arm of the worldwide Anglican Communion. This is the highest level which any member of the Episcopal clergy can attain and the primate is considered the national leader of the Episcopal Church.

In many ways, the status of women clergy within the Episcopal Church is a good case study to examine the applicability of the conflict perspective. Sullins (2000), for example, performed an analysis of the status of ordained women within the Episcopal Church. Sullins's hypotheses were that:

"Women have more subordinate or lower status positions than men do and that this inequality is persistent" (p. 248).

Gender "inequality is greater among the more 'loosely coupled' positions, and these positions are in congregations" (p. 249).

Gender "inequality is smallest at the beginning of the clergy career" (p. 249).

The results of the study analysis found that within local churches, there remains strong resistance to the ordination and deployment of female priests. However, this inequality does not exist in the attitudes of the church hierarchy. Based on his analysis, Sullins concluded that these disparities are cultural because they can be seen elsewhere in the culture (e.g., the glass ceiling phenomenon). However, Sullins goes on to discuss the fact that these disparities may possibly also be accounted for by the differences in career choices that are often made by men and women. He also notes that sometimes opposition to female clergy is organizational and that it may arise from perceived difficulties with organizational maintenance if women are admitted to the ranks of clergy in large numbers. Sullins concludes that a better analogy for denominations and churches in the way that they view women clergy is "family."

Shortcomings of Conflict Theory

As illustrated by this study, conflict theory does not adequately account for all the evidence.

First, if conflict theory is correct and religion serves to stratify rather than liberate, no denomination would permit the ordination of women.

Second, even today in the early twenty-first century with its emphasis on equality for all, more conservative or fundamentalist denominations and sects—including the Roman Catholics—do not ordain women. According to social conflict analysis, keeping women in a subservient position is evidence of religion supporting and reinforcing the values of the status quo. However, this approach does not necessarily explain why an increasing number of denominations today are allowing the ordination of women. Conflict analysis cannot sufficiently account for the differences between denominations on the matter of women's ordination.

Third, conflict analysis does not explain why in the early days of Christianity women were not only ordained to the diaconate and the priesthood, but also to the bishopric.

Fourth, even within some broad denominational categories, there is disagreement over the ordination of women. For example, whereas American Baptists do ordain women as ministers, Southern Baptists (as a whole) currently do not. Further, for some time, Southern Baptists did ordain women. However, in the 1990s they changed this policy and forbad the ordination of women (and have actually requested that the women who are already ordained be rescinded). Although conflict theory could account for some of this body of evidence, it cannot account for it all or explain well why there is so much variation in this matter.

Conclusion

The conflict perspective is an approach to analyzing social behavior that is based on the assumption that social behavior is best explained and understood in terms of conflict or tension between competing groups. When applied to religion, this theory states that religion is a tool that helps maintain the status quo in society by making the lower classes content with promises of great rewards in the life after death. However, the conflict perspective cannot account well for all the evidence of the interaction of religion and society. In fact, religion has been known to be an instrument of social change. Contrary to the predictions of conflict analysis, religions and their concomitant belief systems have been shown to positively affect social change in many situations and countries around the world.

Many religions today teach about human rights, social justice, and social responsibility. In those religions, individuals are more likely to go out into the world and put their faith into practice, thereby righting social injustices rather than reinforcing them. For example, African American churches had a prominent role in leadership during the civil rights movement in the United States; churches gave rise to leaders of the civil rights movement and also served as headquarters for protesters, clearing houses for information, and meeting places to develop strategies and tactics. Further, the association of the Church with the activities of the civil rights movement went at the moral authority and helped reinforce the rightness of the movement based on religious values. This is in direct contradiction to the conflict perspective. Even at the time of the Civil War, the Church did not uniformly support the status quo. In fact, the Southern Baptist Convention actually resulted as a break from the mainline Baptist group at the time due to disagreement over slavery. Although an argument could be made that the southern branch of the Church was supporting the status quo in the South, the majority of the Church did not. Similarly, Islam has made positive changes in the lives of many Black Muslims. Islam includes strict dietary regulation and prohibits many socially undesirable behaviors such as drinking, gambling, and drug use. Based on the tenets of their religion, Black Muslims emphasize self-control, self-reliance, and traditional African identity rather than an identity with their past of slavery. As a result, Black Muslims are often critical of white power structures, thereby giving them a radical political dimension rather than supporting the status quo.

Researchers and theorists working in the area of the sociology of religion have a difficult obstacle to overcome: the operational definition of terms such as spirituality, faith, and belief as in reference to intangible things. Some theorists such as Karl Marx and his conflict perspective choose to ignore such concepts and consider them to be irrelevant manifestations of a nonexistent construct. However, this approach is bad science and forces the assumptions of one worldview onto another worldview. Ignoring the assumptions or experience of another group does not make those assumptions or experiences irrelevant; it only means that any resulting theory cannot account for all the data because it has not considered all of it.

Certainly, it is very difficult to operationally define many of the concepts that religious individuals purport to experience regarding their spiritual or mystical experiences. However, this does not mean that the concepts can be ignored or that they are irrelevant. Defining religiosity, for example, in terms of church attendance or membership does not begin to touch on the religious experience. Similarly, describing the societal role of religion without attempting to account for the true meaning of the religious experience is also doomed to fail. A theorist such as Marx who a priori does not believe in God or the religious experience is unlikely to develop a theory that will adequately explain this experience. As far as the conflict perspective of religion is concerned, in the end it must be remembered that Marxism failed in practice. The official ban on religion in Communist states, for example, did not eradicate it but forced it to go underground. After the fall of communism, there was a resurgence of religion in the states that had previously banned it in keeping with Marxist principles. During the Communist era, the number of churches in Russia decreased to only a tenth of what they had been before the Russian Revolution. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, between 50 and 75 percent of Russians once again admitted to believing in God and nearly 25 percent of the Russians who once called themselves atheists professed a belief in God. The conflict perspective cannot explain this phenomenon.

Terms & Concepts

Conflict Perspective: An approach to analyzing social behavior that is based on the assumption that social behavior is best explained and understood in terms of conflict or tension between competing groups.

Denomination: A large group of congregations united under a common statement of faith and organized under a single legal and administrative hierarchy. Many individual congregations include the name of their denomination in the title of their church (e.g., First Baptist Church, St. Luke's Lutheran Church).

Ethnocentrism: The belief that one's own group is superior to other groups.

Fundamentalism: A theological movement within many religions (e.g., Christianity, Islam) that attempts to reject the tenets and influences of contemporary secular culture and return to the basics (i.e., fundamentals) of the faith, typically through the literal interpretation of scripture.

Ideology: A body of ideas and belief system that reflects the social needs and aspirations of an individual, group, class, or culture.

Operational Definition: A definition that is stated in terms that can be observed and measured.

Religion: A personal or institutional system grounded in the belief in and reverence for a supernatural power or powers considered to have created and to govern the universe.

Religiosity: The quality of being religious; the intensity and consistency of one's practice of a religion. Religiosity is measured by asking about religious beliefs, measuring membership in religious organizations, and measuring attendance at religious services. The term religiosity can also be used to refer to an excessive devotion to religion.

Sect: A distinct subgroup united by common beliefs or interests within a larger group. In religion, sects typically have separated from the larger denomination.

Secularization: The process of transforming a religion to a philosophy and worldview based primarily on reason and science rather than on faith and supernatural concepts. Through the process of secularization, religious groups and activities lose their religious significance.