Discussion #1: Pros and Cons to Delivering Community-Based Participatory Care to Those Who Are Vulnerable.Performing health assessments as an Advance Practice Nurse (APRN) will help you to develop a c

76

CHAPTER 4

Assessing Health and Health Behaviors

Objectives

this chapter will enable the reader to:

Describe the expected outcomes of a nursing health assessment.

Identify the components of a nursing health assessment conducted for an individual client.

Examine life span, language, and culturally appropriate nursing health assessment tools for children, adults, and older adults.

Compare the similarities and differences among the various approaches to assessing the family, mindful of cultural influences.

Evaluate the criteria for conducting a screening in the community.

Compare the similarities and differences among the various approaches to assessing

the community.

Athorough assessment of health and health behaviors is the foundation for tailoring a health promotion-prevention plan. Assessment provides the database for making clinical judgments about the client’s health strengths, health problems, nursing diagnoses, desired health or behavioral outcomes, as well as the interventions likely to be effective. This information also forms the nature of the client–nurse partnership such as the frequency of con- tact and the need for coordination with other health professionals. The portfolio of assessment measures depends on the characteristics of the client, including developmental stage and cul- tural orientation. The nurse assesses age, language, and cultural appropriateness of the various measures selected.

Cultural competence is the ability to communicate effectively with people of different cultures. Providing culturally competent care is the cornerstone of the nursing assessment. The nurse’s aware- ness of her own attitude toward cultural differences and her cultural worldview and characteristics

![]()

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 77

are critical to her understanding and knowledge of various cultures. Recognizing that diversity exists in all cultures based on educational level, socioeconomic status, religion, rural/urban residence, and individual and family characteristics will ensure a more successful encounter (The Office of Minority Health, 2013). An online cultural educational program, designed specifically for nurses and featur- ing videotaped case studies and interactive tools, is available.

The Enhanced National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services, based on a definition of culture expanded to include geography, spirituality, language, race and ethnicity, and biology, provides a practical guide to culturally and linguistically sensitive care (The Office of Minority Health, 2013).

Technology is having a significant impact on health care. The Electronic Health Record (EHR) promotes involvement of the client in developing a dynamic, tailored database. The EHR offers great promise to improve health and increase the client’s satisfaction with his care. Data aggregation, cross-continuum coordination, and clinical care plan management are critical com- ponents of the EHR. It allows storage and almost instantaneous access to data while improving quality and efficiency in health care and improving communication among providers, insurers, and consumers (Figure 4–1).

Promising developments in EHRs are facilitating widespread usage. Among these are cooperation between health care providers and technology companies to create standards for seamless communication, regardless of vendor; cost subsidization of implementing EHRs to encourage physician usage; and incentives offered by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009 provides incentives to physicians and hospitals to make “meaningful use” of EHRs by meeting objectives that positively affect the care of their patients. For example, one objective states that more than 50% of patients who request an electronic copy of their health information should have it within three business days. Clients should be encouraged to request their elec- tronic health information so that they know what is in their record and can participate more fully in their care (CMS.gov, 2009).

Data Aggregation

Data acquisition and exchange platforms for ADT feeds, claim,s and clinical data

Ability to import provider directory files

Algorithms and analytics for inclusion/exclusion criteria by population

Processes, algorithms for patient-provider attribution

Cross-Continuum Coordination

• Shared care plans

• Activity tracking and real-time

notification of encounters (ED, admission, discharge)

• Disease registries

• Health information exchanges

• Enhanced communication aides

for care team connectivity

• Patient outreach and messaging

Clinical Care Plan Management

• EMR, case and utilization management systems

• Workflow automation and rules engines

• Assessment tools, clinical care protocols, and work lists • Analytics for high-risk patient

identification

• Telehealth and home monitoring capabilities

FIGURE 4–1 IT Support for Care Management Progresses Beyond EHR Functionality Source: Comstock, J. Asthmapolis, now Propeller, moves beyond asthma. Mobilhealthnews. September 10, 2013; Propeller Health, available at http://propellerhealth.com/, accessed September 25, 2013. The Advisory Board Company interviews and analysis.

78 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

While there are many benefits of the EMR, there are also questions to answer about best practices for the successful implementation of patient-accessible EMRs. These questions include cost, security, privacy, consumer and provider education, and user-friendly systems. To over- come some of the current issues, researchers are investigating tamper-resistant and portable health folders and evidence-based designs to evaluate consumer health informatics (Chen, Lu, & Jan, 2012; Li, Lee, Jian, & Kuo, 2009). In addition, access to web-based portal links (electronic patient portals) for patients to view and modify their record encourages adoption by patients.

Doctors who are more willing to open their doctors’ notes via secure Internet portals, and patients who take advantage of the opportunity to access them, create transparency between pro- viders and patients. This ensures more open communications and shared responsibility for the patient’s health. Most patients are willing to accept some compromises to privacy in order to have more access to their health records and to make records more transparent (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009).

With the implementation of EMRs, computers are showing up in more and more health care settings. The introduction of computers into the examination room potentially is a barrier to meaningful provider/patient relationships. Health care providers should face the client while they are entering data, being careful to maintain eye contact and engagement with the client. To do otherwise is to focus on the technology, and not the client.

The Personal Health Record (PHR) is a another application to help consumers take charge of their health and has the potential to improve care, lower costs, and help clients obtain and manage the care they need. The PHR belongs to the user and is distinct from physician records (Figure 4–2).

Insurance Company

Claims data

Disease management

profile

Medications

Risk score

Data Sources for PHR

Patient

Chronic condition management data, from patient or connected devices

Appointment requests

Allergies

Medications

Family history

Proxy access, consent data

Personal Health Record

FIGURE 4–2 PHRs: Allowing Patients to Actively Manage Their Data Company Interviews and Analysis, 2013.

Provider

Physician visits

Hospitalizations

Lab, test results

Medications

Pre-visit intake forms

Reminders, messages

Billing information

Referral information

Source: The Advisory Board

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 79

GPS Device on Inhaler Provides Accurate Information on Asthma Complications

Inhaler usage automatically tracked, shared with physician

Physician reviews patterns and trends with patient during next scheduled visit

Physician able to proactively reach out to patient between visits if usage increases

Passive Tracking Improves Outcomes

80% Increase in medication adherence among users

>66% Proportion of app users who were well-controlled

Case in Brief: Propeller Health

• Health care technology firm based in Madison, Wisconsin

• Attachable GPS device for asthma and COPD inhalers sends real-time breathing and medication adherence data to provider

FIGURE 4–3 New Technologies Fostering Self-Care Source: The Advisory Board Company Interviews and Analysis, 2013.

CMS initiated a pilot PHR program in 2009 for clients to add supplemental information to their health record, authorize access to third parties such as family members, and track and view claims. The evaluation of this pilot showed the preferences of consumers to include download- able data, direct on-line communication between client and provider, simplified log-ins, and strong technical support.

Nursing clinics, community health centers, and primary care centers are using EHRs, PHRs, and/or cell phone technology to offer comprehensive resources, including easily cus- tomized and self-managed online portfolios (see Figure 4–3). The smartphone, named one of the top medical trends for 2013, increases greatly the option of clients’ involvement in their health care. Governmental approval of mobile software applications such as ones that help clients monitor potential skin cancers, or that provide doctors with a mobile electrocar- diogram, are being promoted as ways to fight disease and get health care costs under control (ANA, SmartBrief, 2012).

Social media such as Facebook and Twitter optimize communications with clients. Tai- lored health information, delivered through these new informatics interventions, has the poten- tial for enhancing self-efficacy, improving decision making, increasing healthy behaviors, and fostering self-care. The potential for consumers to be involved in the ownership and mainte- nance of their health record with “cradle-to-grave” information is especially relevant for com- puter users and technology-savvy consumers who interface with providers and health systems. Age, race, and culture are significant discriminators of computer/Internet home usage, with 65 and older people’s usage at 29.8% and all other age groups’ usage ranging from 55.2% to 62.6%. Whites (56.1%) are more likely to use a home computer to connect to the Internet than Blacks (41.7%) and Hispanics (35.4%) are. Age is the greatest influence on the focus of Internet searches; for example, persons 45 years and older conduct Internet searches about health care more

80 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

![]()

TABLE 4–1

Reported Activity of People Using the Internet, by Selected Individual Characteristics: 2010 Population age 15 and over Number in thousands

Percent of those connected to the Internet who engage in each type of Internet activity

Selected

characteristics the Internet

Take a

course online healthcare services job

Total connected to

Search for

Search about government Search for a

Total 145,286

11.4 35.5 33.2 24.8

13.4 17.6 19.8 31.5 13.5 35.3 34.1 34.3 12.2 38.1 36.4 27.0 10.2 42.8 39.1 19.1

4.3 46.2 34.6 4.0

11.2 36.0 33.2 23.6 11.4 37.0 33.8 23.1 12.0 30.1 30.9 32.3

9.7 27.5 27.8 27.9

10.9 29.6 32.0 25.1 11.8 41.0 34.3 24.5

11.6 36.1 33.4 24.5 8.8 27.1 27.6 26.3 11.5 37.9 37.7 28.6

Age

15–24 years 25–34 years 35–44 years 45–64 years

65 years and over

Race and Hispanic Origin

30,687 27,963 26,471 47,917 12,248

White 119,892 Non-Hispanic 106,947 Black 14,953 Hispanic 14,309 (of any race)

Gender

Male 70,229 Female 75,057

Language spoken at home

Speaks English only at home Speaks Spanish at home Speaks other language at home

126,776 11,141 7,368

![]()

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce. 2010 Census Report

frequently than do those under 45 (Table 4–1; U.S. Department of Commerce Census, 2012). Non-computer users and vulnerable populations are at greater risk, which may exacerbate health disparities unless a safeguard system protects these groups. Safeguards include developing the concept of health care partners, opportunities for clients to access a computer, and staff available to enter information at the client’s request.

Another technology making a significant impact on health care is telehealth, the use of electronics and telecommunications to support long-distance care. Health assessment occurs in a variety of settings including hospitals, clinics, offices, community centers, schools, and

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 81

FIGURE 4–4 Telehealth Improves Access to Care Source: http://www.telehealth.va.gov

homes; and the home is becoming a primary setting for assessing and delivering health services due in large measure to telehealth. The Veterans Administration is a major player in funding, developing, and using telehealth. As technology improves and cost decreases, telehealth is likely to have an even greater impact on health care (Figure 4–4). Three points are spurring adoption of telehealth:

• Governmentalsupportandintegrationintoaccountablecareorganizations • Consumerdemand

• Technologicalinnovation

NURsING FRAmEwoRks FoR HEALTH AssEssmENT

Health assessment performed by the nurse is a collaborative partnership with the client that pro- motes mutual input into decision making and planning to improve the client’s health and well- being. The initial assessment provides a valuable baseline to compare subsequent assessments.

The desired outcomes describe the following:

1. Health assets

2. Health problems

3. Health-related lifestyle strengths

4. Key health-related beliefs

5. Health behaviors that put the client at risk 6. Changes that improve the quality of life

Nursing frameworks are available for nurses to assess and diagnose health and health behaviors. Nursing assessment is the systematic collection of data about a client’s health status, beliefs, and behaviors relevant to developing a health promotion-prevention plan, whereas nurs- ing diagnosis is the identification and enhancement of assessment to maximize health status.

82 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

Nursing diagnostic classification systems (taxonomies) primarily focus on the individual and aspects of illness. Hence, positive health states (or strengths) of the individual, family, or community are not always adequately addressed in these taxonomies. As health promotion and prevention knowledge expands, taxonomies continue to include new definitions supportive of a health promotion/wellness perspective.

The North American Nursing Diagnosis International (NANDA-I) nursing diagnosis tax- onomy responds to the nine human response patterns: exchanging, communicating, relating, valuing, choosing, moving, perceiving, knowing, and feeling (National Association of Nursing Diagnosis-International, 2013). The defining characteristics of each diagnosis, as well as related factors and risk factors, provide guidance about the critical assessment areas for the diagnosis. The NANDA-I classification provides a way to diagnose and intervene in selected health promo- tion and wellness processes and problems across the span of nursing practice (Popkess-Vawter, 2008). For example, stress overload occurs when the client presents feelings of tension and pres- sure that interfere with effective decision making, resulting in physical or psychological distress. Potential interventions, including active listening and decision-making support, address the stress overload diagnosis (Lunney, 2008).

Other examples of wellness nursing diagnoses/processes (client strengths) include the following:

1. Nutrition adequate to meet or maintain body requirements 2. Exercise level appropriate to maintain wellness state

3. Strength derived from one’s spirituality

Case studies and sample care plans are available to illustrate how diagnostic statements provide direction for health promotion-prevention care planning.

Gordon (2009) grouped the NANDA-I diagnoses into 11 functional health patterns to assist in classifying nursing diagnoses:

1. Health perception–health management 2. Nutritional–metabolic

3. Elimination

4. Activity–exercise

5. Sleep–rest

6. Cognitive–perceptual

7. Self-perception–self-concept 8. Role–relationship

9. Sexuality–reproductive

10. Coping–stress tolerance 11. Value–belief

Gordon provides guidelines to conduct a nursing history and examination to assess clients’ functional health patterns. As assessment proceeds, diagnostic hypotheses generate targeted or more detailed data collection. Refer to Gordon’s Manual of Nursing Diagnosis for recommended formats to assess functional health patterns in infants and young children, adults, families, and communities (Gordon, 2009).

The Omaha Visiting Nurse Association System is a useful guide for community health nurs- ing practice, a method of documentation, and a framework for community management. The Omaha System incorporates the needs of individuals and families in the categories of environ- ment, psychosocial, physiological, and health behavior needs. These categories use key words such

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 83

as individual, family, or health promotion in the individual and family categories. Nurse research- ers have shown the usefulness of the Omaha System in quantifying nursing practice in community health, rural nursing practice, primary care, and wellness centers. A difficulty in developing nurs- ing classification systems for communities is that nursing diagnoses/problem classifications focus on nursing practice, whereas community problems focus more on interdisciplinary practice.

Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), a system that generates standardized nursing actions and interventions for providing care, is relevant for community health because nursing services are categorized and linked to direct reimbursement (Bulechek, Butcher, Dochterman, & Wagner, 2013). However, NIC does not have categories for the health behaviors of communities. The Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) system measures the responses of an individual, family, and community behavior/perception to a nursing intervention and is useful in all settings with individuals, families, and communities (Moorhead, Johnson, Maas, & Swanson, 2013).

The next phase of knowledge generation in nursing is the integration of terminologies into EHR information systems to support standards of care across settings worldwide. Integration will make it easier to describe and share interventions that work or do not work to help people be healthy and reduce costs. Research using data from information systems embedded with nursing standards and terminology builds nursing knowledge and documents the contribution of nursing to health care.

GUIdELINEs FoR PREvENTIvE sERvIcEs ANd scREENINGs

An increasing emphasis on the prevention of disease has resulted in the development of varying sets of guidelines for the delivery of preventive services to individuals, families, and communities across the life span. These guidelines focus on clinical care directed toward prevention of specific diseases such as HIV disease and behavioral morbidity such as substance abuse.

The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2012) is an authoritative source for making decisions about preventive services. In 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended limiting the use of screening mammography. The recommendation garnered the media’s attention and, according to one study, the percentage of women screened the year following the recommendation declined by 4.3%, suggesting that the recommendation had a chilling effect on the willingness of women to get mammograms. How- ever, Block and colleagues examined data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study and observed no change in rates among women who had mammograms the previous year, but did observe lower rates of mammogram use among women who reported no mammogram in the previous year (Block, 2013).

Other experts report 1.3 million overdiagnosed breast cancers over 30 years, meaning that their screening detected tumors that would never lead to clinical symptoms (Bleyer & Welsh, 2012). However, the American Cancer Society and the American Radiology Association continue to recommend that women undergo a yearly mammogram beginning at age 40.

Screening is not right for everyone or every health problem. Screenings to detect particular, unrecognized health problems in individuals who are members of at-risk groups reduce false alarms. However, data are not sufficient to address all the uncertainties of general screenings.

Screenings uncover health problems in an efficient and economically feasible manner when the following factors are present:

1. The specific population has a high prevalence of the disease or health problem. 2. Treatment is available if the condition is identified.

3. Screening instruments are valid and reliable.

84 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

The cost of conducting screenings bears on the decision to offer large-scale screenings. For example, conducting a screening to detect osteoporosis requires special equipment, and the cost may be high due to the number of machines needed to screen in a timely, efficient manner. In addition to cost, targeted screenings should consider race/ethnicity, age, and low income and how these factors relate to increased or decreased willingness to participate in screenings, along with the risks and benefits (Kressin, Manze, Russell, Katz, Claudio, Green, & Wang, 2010).

Elective Preventive Services Selector (ePSS) is a quick, hands-on tool available to pri- mary care providers to identify screening services that are appropriate for particular clients based on the recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and can be searched by client characteristics, such as age, sex, and behavioral risk factors. ePSS is available as Web and Mobile applications for the iPhone, iPad, and other mobile devices. Through these appli- cation nurses and other clinicians have preventive information—recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools—available at the point of care (U.S. Preventive Ser- vices Task Force, 2012). Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (U.S. Department of Commerce Census, 2012) and Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (Hagan, Shaw, & Duncan, 2008) also are important guidelines for nurses to be familiar with and use to ensure that clients across the life span benefit from state-of-the-art preventive services.

AssEssmENT oF THE INdIvIdUAL cLIENT

Assessment of the individual client in the context of health promotion extends beyond physical assessment to include a comprehensive examination of other health parameters and health behaviors. The purpose of the assessment, setting, culture, and age determine the components of health assessment. The components are as follows:

• Functionalhealthpatterns • Physicalfitness

• Nutrition

• Lifestress

• Spiritualhealth

• Socialsupportsystems

• Healthbeliefsandlifestyle

Functional assessment of health patterns comprises a health history, including hereditary and family characteristics, and physical assessment. Assessment components focus on individu- als and have particular relevance for health promotion and prevention.

Physical Fitness

Physical activity is an important part of personal health status (see Chapter 6). Determining one’s level of physical fitness is a critical part of the nursing assessment. A sedentary lifestyle, for many individuals, begins early in childhood and continues into adulthood. The assess- ment is applicable to clients of all ages, with restrictions on some components for physically compromised individuals. Skill-related physical fitness and health-related physical fitness focus on different qualities.

Skill-related fitness focuses on qualities that contribute to successful athletic performance: agility, speed, power, and reaction time. Health-related fitness focuses on qualities that contribute

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 85 to general health and include cardio-respiratory endurance (aerobic capacity); muscular endur-

ance, strength, and flexibility; and body composition.

cARdIo-REsPIRAToRy (cR) ENdURANcE (AERoBIc cAPAcITy). Aerobic capacity is the most important component of fitness. Fitness reflects the ability of the CR system to efficiently adjust to and recover from exercise. Research shows that individuals with an acceptable aerobic capacity have a reduced risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and other health problems.

mUscULAR ENdURANcE, sTRENGTH, ANd FLExIBILITy. The goal of muscular endurance, strength, and flexibility tests is to determine the functional health status of the musculoskeletal system. It is important to have strong muscles that maintain body structure and endurance. The strength and endurance of the upper body muscles are good indicators of overall fitness. Flexibil- ity, the ability to move muscles and joints through their maximum range of motion, also is an important component of physical fitness. Flexibility decreases with age and chronic illness. The lack of ability to flex or extend muscles or joints often reflects poor health habits, such as seden- tary lifestyle, poor posture, or faulty body mechanics. Loss of flexibility greatly decreases one’s ability to move about with ease and comfort.

Body comPosITIoN. The increased prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults in the United States is a concern for both the public and private sectors. The availability of high-fat and low-cost fast foods and the decline in levels of physical activity contribute to these trends. Increased levels of body fat are associated with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stroke in adults; and diabetes, hypertension, and increased cholesterol levels occur more frequently in overweight and obese children.

Estimates of body fat include underwater weighing, bioelectrical impedance, skin fold measures, and other anthropometry measures such as the Body Mass Index (BMI). Each method has limitations leading to measurement errors of 2% to 3% for estimates of body fat, with the BMI error rate as great as 6% because body weight includes bone and muscle mass and not just fat composition.

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) provides a measure of body fat when a small, safe electrical current passes through the body, carried by water and electrolytes of the fluid spaces. Impedance is greatest in fat tissue, which contains only 10 to 20% water, while muscle tissue, which contains 70 to 75% water, allows the signal to pass more easily. Height and weight, body type, gender, age, fitness level, and BIA are measures used to calculate percentage of body fat, muscle mass, and hydration level (American College of Sports Medicine, 2009).

BIA is useful in healthy, young, normally hydrated teens and adults, and for monitoring these groups for changes in body fat composition over time. Body fat scales (similar to bathroom scales) and handheld body fat analyzers, both available at reasonable cost, also provide a measure of BIA. While technology is improving, it is difficult to get an accurate body fat composition from commercially available body fat analyzers.

Anthropometric (measures of body fat) methods are simple, convenient, and inexpensive. Skin fold estimates, conducted while maintaining standards and using high-quality skin fold calipers, provide an accurate measure of body fat and compare favorably with bioelectrical impedance. The combination of weight, anthropometric methods, and BIA is an excellent predic- tor of total body fat composition.

A physical fitness assessment is an essential component of health assessment. Careful atten- tion to assessment will optimize the fit of the exercise prescription to the physical capabilities of

86 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

the client. The Presidential Youth Fitness Program adopted FITNESSGRAM, a research-based assessment developed by the nonprofit Cooper’s Institute, and recommends implementation in all public schools. The FITNESSGRAM program assesses cardiovascular fitness, body composi- tion, muscle strength, muscular endurance, and flexibility in children 4 to 17 years of age. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013) is an excellent guide for physical fitness assessment tools for adults.

Nutrition

Good nutrition is one of the primary determinants of good health. Effective planning for health promotion requires an assessment of the nutritional status of the client to establish a baseline. Anthropometrical measurements and/or BIA analysis, laboratory values, and dietary history are useful assessment tools.

Anthropometrics assessment measures include height and weight, circumference of various areas of the body, and skin-fold thickness. BMI is the best method to assess healthy weight (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013). BMI does not assess body fat composi- tion or fat distribution, but it is a useful screening tool for overweight or obesity. It has been determined that childhood BMI is associated with adult adiposity. The classification of over- weight and obesity by BMI, waist circumference, and associated disease risks standards for adults is available in Table 4–2.

Healthy and unhealthy weight guidelines are in Table 4–3. The waist-to-hip ratio assesses the amount of fat distributed in the abdomen versus fat distributed below the waist. The ratio is the waist circumference over the hip circumference. The higher the value of the waist-to-hip ratio, the greater the potential that health problems are present or will occur (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013; WHO Expert Consultation, 2008).

Biochemical analyses of blood and urine help to identify nutritional deficiencies. In addi- tion to laboratory tests for cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and high-density lipoproteins, tests for protein (creatinine index, serum protein, serum albumin, total lymphocyte count, blood urea nitrogen, uric acid), serum or plasma vitamin levels (water-soluble, fat-soluble), and minerals (calcium, sodium, potassium, iron, phosphorus, magnesium) are used to assess

![]()

TABLE 4–2

Normal† Overweight Obesity

Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risk*

Disease Risk* Relative to Normal Weight and Waist Circumference

BMI (kg/m2)

18.5–24.9

25.0–29.9 30.0–or above

Men $ 40 in. Women $ 35 in.

—

Increased High

Men . 40 in. Women . 35 in.

—

High Very High

![]()

*Disease risk for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and CVD.

†Increased waist circumference can also be a marker for increased risk even in persons of normal weight.

Source: Adapted from Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic of Obesity. Report of the World Health Organization Consultation of Obesity. WHO, Geneva, June 1997. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/e_txtbk/txgd/411.htm

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 87 TABLE 4–3 Healthy and Unhealthy Weight Guidelines

![]()

![]()

Are you at a healthy weight? Height*

BMI

18.5

25

30

6' 6"

6' 5" 6' 4" 6' 3" 6' 2" 6' 1" 6' 0"

5' 11" 5' 10" 5' 9" 5' 8" 5' 7" 5' 6" 5' 5" 5' 4" 5' 3" 5' 2" 5' 1" 5' 0" 4' 11" 4' 10"

![]()

![]()

![]()

50 75

100 125 150

Overweight Obesity

175

200 225 250

Pounds† Healthy Weight

* Without shoes.

275 † Without clothes.

The BMI (weight-for-height) ranges shown are for adults. They are not exact ranges of healthy and unhealthy weights. However, they show that health risk increases at higher levels of overweight and obesity. Even within the healthy BMI range, weight gains can carry health risks for adults.

Directions: Find your weight on the bottom of the graph. Go straight up from that point until you come to the line that matches your height. Then look to find your weight group.

BMI of 24.9 defines the upper boundary of healthy weight. BMI of 25 to 29.9 defines overweight.

BMI of 30 or higher defines obesity.

Source: Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. (2000). http:// www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2000/2000DGCommitteeReport.pdf, p. 11.

nutritional status. Three particularly important values in assessing nutritional status are serum albumin less than 3.5 g/dL, total lymphocyte count less than 1800/mm3, and an involuntary loss of body weight greater than 15%. These three indicators correlate significantly with nutri- tional status (Gupta & Lis, 2010; Nishida & Sakakibara, 2010).

The dietary diary, available as either a paper or Web-based option, is one common measure used to assess nutritional status. SuperTracker, a diet planning and tracker tool is a Web-based dietary assessment that is easy to access and use. It incorporates both the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines. After the client, or nurse, enters the

![]()

88 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

requested dietary information, the results are a part of a tailored nutrition plan that empowers the client to make healthier food choices. ChooseMyPlate also has a Spanish-language food icon MiPlato to guide Spanish-speaking consumers in making healthy food choices.

With the paper option dietary diary, clients keep a record of everything eaten for three days during the week prior to their office or home visit. Daily food choices, compared with published daily food guides or a computerized dietary analysis package, identify unusual or poor dietary patterns (see Nutrition and Health Promotion, Chapter 7). The nurse and nutritionist work together to prepare materials and/or recommend websites to ensure that the client has the latest and most accurate research findings about nutritional supplements, including vitamins and min- erals (calcium, iron) as well as proteins and complex carbohydrates. Tools for assessing nutrition in primary care settings are available.

Culture and socioeconomic level influences eating patterns, obesity, and malnutrition. Assessment of nutritional status and dietary habits is a critical part of comprehensive health assessment for individuals, families, and specific target groups, such as high-school students, pregnant women, and the elderly. An analysis of assessment data determines which interventions are most appropriate to improve the nutritional status of the client/family. Understanding cul- tural influences on nutrition and dietary patterns is essential in both assessment and intervention to affect change.

Life stress

Stress is a potential threat to mental health and physical well-being and is associated with ill- nesses such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and gastrointestinal disorders, as well as depres- sion, poor sleep patterns, and inability to carry out daily activities at an effective level. Life stress is a part of a comprehensive health assessment. Assessment begins with helping the cli- ent identify sources of stress. One strategy is to have the client write down the issues, con- cerns, and challenges that trigger stress responses in his or her life. Some of the stressors will be internal, and others will be external events. External stressors are events and situations that happen to individuals.

Examples of external stressors include the following:

Some events may be happy ones such as marriage, birth of a child, and a new home, while some may be negative, such as death of a loved one, loss of a job, and an unplanned preg- nancy. Stress results from both positive and negative events.

The interaction between the individual and the environment involves subjective perception and assessment of stressors. Common events—such as a barking dog, a crying baby, and extreme weather conditions—may cause stress.

Much of life is unpredictable, and one’s personality influences responses to change and unplanned-for events. Unpredictable events include dealing with unexpected house guests, increased rent, or a sick child.

Family stressors include conflicts and arguments between children and spouses, issues resulting from the health problems of family members, and multigenerational households.

Common stressors in the workplace include long working hours, difficult coworkers, and

urgent deadlines.

Social stressors include commitments to family, friends, and organizations balanced with

the need for downtime for oneself, and pressure from peers.

Internal stressors are self-induced thoughts and feelings that lead to unrest and anxiety.

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 89 Examples of internal stressors include the following:

Common fears such as flying, heights, and public speaking.

The inability to predict behaviors such as use of alcohol and not knowing the outcome of

medical tests.

Attitudes and expectations exhibited toward job loss or unexpected guests.

Despite the high prevalence of stress-related health problems, including substance abuse,

primary care providers screen too few clients for these problems. Regular screenings enable ear- lier identification of problems and earlier treatment. Screening tools include the following:

sTREss scALEs. Assessing a person’s vulnerability to stress and strength to cope provides an essential measure of mental and physical well-being. The Derogatis Stress Profile (Derogatis & Lazarus, 1997) assesses personal and professional stress in adolescents and adults. The Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kessler, & Gordon, 1997) measures moods and feelings about life stressors and is considered a measure of global stress.

HAssLEs ANd UPLIFTs. Hassles are the irritating, frustrating, distressing demands such as traffic jams, losing items, and arguments that characterize everyday life. Uplifts, the counterpart of hassles, are the positive experiences or joys of life, such as getting a good night’s rest, receiving an email from a friend, or spending time with a pet. The assessment of daily hassles and uplifts is a better predictor of health or illness than the usual assessment of life events. An example of a hassles and uplifts scale is the Adolescent Hassle Scale (AHS; Wright, Creed, & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2010).

ANxIETy INvENToRy. Anxiety level is a part of the life-stress review. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory consists of 20 items that assess the extent of anxiety one feels at that moment (state anxiety) and 20 items that assess how one generally feels (trait anxiety; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, & Vagg, 1983). A State-Trait Anxiety Inventory is available for children (“How I Feel Questionnaire”; Spielberger et al., 1983). Both instruments and administration manuals are avail- able from Mind Garden, Palo Alto, California.

sTREss wARNING sIGNALs INvENToRy. Clients should understand and be aware of the symptoms of an elevated stress level. When clients are aware of their own stress signals, they can use stress-management techniques (see Chapter 8) more effectively. Symptoms of stress may be physical, behavioral, emotional, or cognitive as shown in Figure 4–5.

coPING mEAsUREs. Coping is an individual’s ongoing efforts to manage specific internal and external demands that exceed personal resources. A commonly used tool to measure coping is the Ways of Coping Questionnaire developed by Folkman and Lazarus (1988). The scale mea- sures both the emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies an individual uses when respond- ing to a stress situation. The Schoolager’s Coping Strategies Inventory is used to measure the type, frequency, and effectiveness of children’s stress-coping strategies, and additional instruments to measure stressors in children are available [Ryan-Wenger, Wilson (Sharrer), & Broussard, 2012].

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) is a two item-screening test that consists of the first two questions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) tool to assist providers with diagnosing depression. The client that answers positively to one or both of the two items (PHQ-2) then answers the remainder of the seven items on the PHQ-9 (Li, Friedman, Conwell, & Fiscella, 2007). The PHQ-2 is effective in screening large groups to detect undiagnosed depression in a variety of populations.

90 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

Headaches Indigestion Stomachaches Sweaty palms Sleep difficulties Dizziness

Excess smoking

Bossiness

Compulsive gum chewing Attitude critical of others

BEHAVIORAL SYMPTOMS

EMOTIONAL SYMPTOMS

Back pain

Tight neck, shoulders Racing heart Restlessness Tiredness

Ringing in ears

Grinding of teeth at night Overuse of alcohol Compulsive eating Inability to get things done

Overwhelming sense of pressure Anger

Loneliness

Unhappiness for no reason Easily upset

Inability to make decisions Thoughts of running away Constant worry

Loss of sense of humor

Stress Warning Signals PHYSICAL SYMPTOMS

Crying

Nervousness, anxiety

Boredom—no meaning to things Edginess—ready to explode Feeling powerless to change things

Trouble thinking clearly Forgetfulness

Lack of creativity Memory loss

COGNITIVE SYMPTOMS

Do any seem familiar to you?

Check the ones you experience when under stress. These are your stress warning signs.

Are there any additional stress warning signals that you experience that are not listed? If so, add them here.

FIGURE 4–5 Stress Warning Signals Source: From Benson, H., & Stuart, E. M. 1992. The Wellness Book. New York, NY: Citadel Press/Kensington Publishing Corp. All rights reserved. Reprinted by arrangement with Citadel Press/Kensington Publishing Corp.

See Instruments for Clinical Healthcare Research (Frank-Stromborg, 2004) for a review of instruments on stress, coping, and anxiety and the relevance of each measure to nursing.

spiritual Health

Spiritual health is the ability to develop one’s inner being to its fullest potential. Spiritual health includes the ability to discover and articulate one’s basic purpose in life; to learn how to experience love, joy, peace, and fulfillment; and to help oneself and others achieve their fullest potential.

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 91

The assessment of spiritual health is critical in a holistic approach to health as spiritual beliefs affect a client’s interpretations of life events and health. Acquiring a better understanding of clients’ spiritual needs will enable health care providers to develop tailored and effective spiritual interventions (Monod, Rochat, Bula, & Spencer, 2010).

Examples of spirituality measures include the following:

The Spiritual Needs Assessment for Patients (SNAP) is a 23-item multidimensional survey instrument to describe and measure spiritual needs (Galek, Flannelly, Vane, & Galek, 2012).

The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale (SIBR) measures actions as well as beliefs across religious traditions (Litwinczuk & Groh, 2007). This instrument and the previous one provide supportive data for understanding the client’s spiritual beliefs and their impact on health needs and care.

The Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) is a 10-item instrument that measures one’s percep- tions of the extent to which one’s spiritual beliefs and one’s daily interactions are consistent (Chung, Wong, & Chan, 2007).

Additional measures are available in Instruments in Clinical Healthcare Research (Frank-Stromborg, 2004).

social support systems

Two approaches for reviewing the social support networks of clients are useful in providing the client and nurse increased insight into existing support resources. When assessing the adequacy of support systems, it is important to be cognizant of factors that may cause the assessments to vary. Such things as the client’s culture, age, social context (school, home, work), and role context (parent, student, professional) influence perceived and received support. Using the Internet to expand one’s social contacts is increasing in popularity and can be included in assessing the cli- ent’s social support system. Definitive measures for assessing social support are abundant in the literature. They can also be found on educational websites, such as Stanford University.

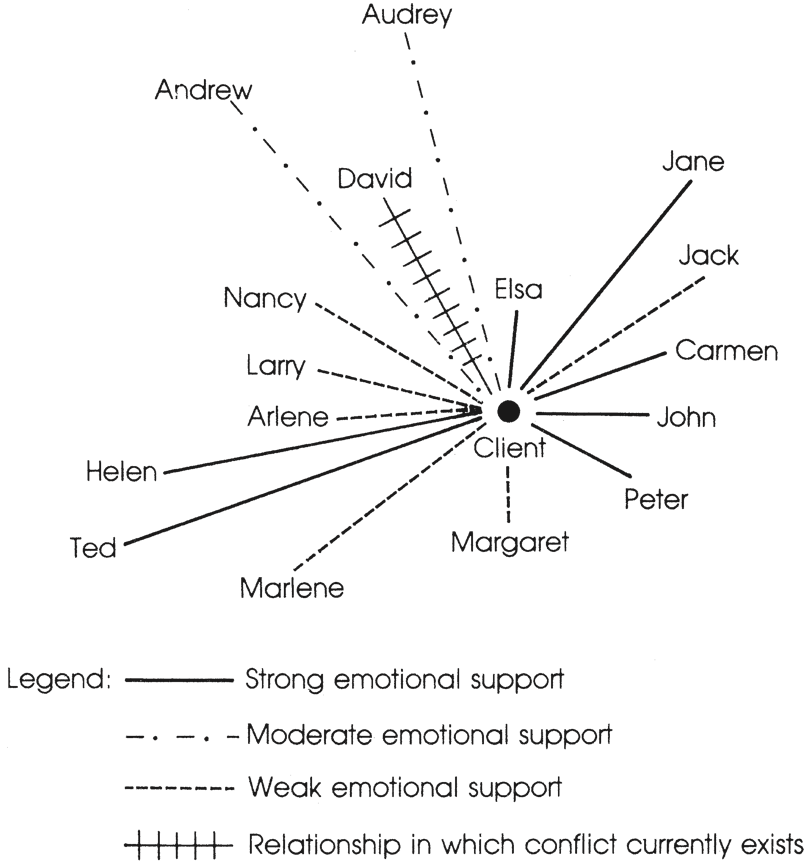

sUPPoRT sysTEms REvIEw. One straightforward, useful approach to assess support systems is to ask the client to list individuals who provide informational, emotional, appraisal, or instru- mental support. Then ask the client to indicate the relationship with the persons listed. Next, identify persons who have been sources of support for five years or more. This list enables the client to become aware of the stability of personal support systems. Last, identify the frequency and types of contacts. These may be face-to-face or telephone and e-mail communication. Exam- ining the social network enables the client and the nurse to assess the adequacy of support. If it is inadequate, generate strategies to enhance existing social networks. Figure 4–6 shows a sample of a completed support system review.

After reviewing the client’s social support systems, explore the following questions:

• Inwhatareasdoyouneedmoresupport:informational,emotional,instrumental,appraisal? • Whowithinyourpresentsupportsystemmightprovidetheneededsupport?

• Whoelsedoyouthinkneedstobecomeapartofyoursupportsystem?

• Whatcanyoudotoaddthepeopleyoubelieveyouneedtoyoursupportsystem?

Answers to these questions suggest actions the client can take to expand sources of per- sonal support.

92 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

List individuals who provide support to you. Next indicate the following relationships: Family member (FM); Fellow worker (FM); or Social Acquaintance (A). Frequency of Contact: Daily (D); Weekly (W); Monthly (M); or Rarely (R). Types of Contact: Face-to- Face (F); Telephone (T); or Email (EM). If individual has been supportive for 5 years

or more, place the number 5. Individual Relationship

Frequency Type D F D F D F W T

Time 5

5

5

5

-

-

5

-

5

John FM (husband)

Peter FM (son)

Helen FM (daughter)

Ted FM (father)

Andrew FW D F

Frances FW Rose FW Elsa A Jack A

W F W T M E M E

Ask the client to identify the type of support provided by individuals in the list. They may provide more than one type of support.

Sources of Emotional Support

FAMILY WORK John Frances Peter Rose Helen Andrew Ted

SOCIAL GROUP Elsa

Jack

Sources of Instrument Support

FAMILY WORK SOCIAL GROUP John Andrew Jack

Ted

Sources of Information Support

FAMILY WORK SOCIAL GROUP

John Andrew Ted Rose

Jack

Sources of Appraisal Support

FAMILY WORK SOCIAL GROUP John Rose Elsa

FIGURE 4–6 Support System Review: Social Network and Type of Support

EmoTIoNAL sUPPoRT dIAGRAm. Diagrams are effective ways to assess the strength and sources of support. Figure 4–7 presents a sample emotional support diagram that indicates strong, moderate, and weak sources of support, as well as current conflicts with supportive indi- viduals. The length of each line indicates geographical proximity to the client. This approach is particularly appropriate for clients who need a visual presentation of their emotional support system to take action to sustain or enhance emotionally satisfying relationships.

An integral part of the assessment is a review of sources of social support. A review enables the client to recognize current sources of support and identify barriers in social rela- tionships that may block desirable health actions. The nurse must always be alert to client

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 93

FIGURE 4–7 Emotional Support Diagram for Client

situations in which social support is minimal or nonexistent. Extensive review of support systems may cause anxiety and depression, and in this case, a more informal, nonthreatening approach is useful.

Social support instruments represent the broad spectrum of measures used in clinical settings as well as research. The Social Support Questionnaire is a six-item measure of per- ceived social support and satisfaction with social support. Each item presents a specific sce- nario for which respondents list the people who would be available for support in that situation. Respondents are also asked to rate their satisfaction with the support available (Sarason, Shearin, Pierce, & Sarason, 1987).

Lifestyle Assessment

In the context of health, lifestyle defines discretionary activities that are a regular part of one’s daily pattern of living and significantly influences health status. Health-promoting behavior is an expression of the human actualizing tendency that optimizes well-being, personal fulfill- ment, and productive living. The 52-item Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP-II), a revision of the original instrument, consists of six subscales to measure major components of a health promoting lifestyle: health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, interpersonal rela- tions, spiritual growth, and stress management. Scores are obtained for each subscale, or a total scale score is calculated to measure overall health-promoting lifestyle (Sechrist, Walker,

94 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

TABLE 4–4 Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II: Subscales and Sample Subscale Items

![]()

![]()

Subscale

Health responsibility Physical activity

Nutrition Interpersonal relations Spiritual growth Stress management

Sample Item

Read or watch TV programs about improving my health.

Question health professionals in order to understand their instructions.

Exercise vigorously for 20 or more minutes at least three times a week (brisk walking, bicycling, aerobic dancing, using a stair climber).

Get exercise during usual day activities (such as walking during lunch, using stairs instead of elevators, parking car farther away from destination and walking).

Choose a diet low in fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol.

Eat 2 to 4 servings of fruit each day.

Spend time with close friends.

Settle conflicts with others through discussion and compromise. Feel connected with some force greater than myself.

Am aware of what is important to me in life. Take some time for relaxation each day.

Pace myself to prevent fatigue.

![]()

Pender, & Frank-Stromborg, 1987). The HPLP-II provides important information about a client’s lifestyle. Sample items for each of the subscales appear in Table 4–4. A HPLP-II profile provides information to develop an individualized health promotion plan that identifies life- style strengths and resources as well as areas for further growth. A Spanish-language version of the HPLPII is available. The Adolescent Lifestyle Profile (ALP) measures seven domains of health-promoting lifestyle (Hendricks, Murdaugh, & Pender, 2006) and is useful for measuring health-promoting behaviors in adolescents.

Additional lifestyle instruments are available at educational websites, including Stanford University.

sTAGE oF cHANGE AssEssmENT. Clients may be at one of several stages in relation to any given behavior change. Table 4–5 shows the stages of change for positive health behaviors. Recognizing the different stages of change in relation to various health behaviors allows for more tailored interventions.

TABLE 4–5 True–False Statements for Assessing Stages of Behavior Change

I currently do not (specify exact behavior, e.g., exercise 30 minutes three times a week, eat 2 to 4 servings of fruit daily) and do not intend to start in the next 6 months. (Precontemplation)

I currently do not (specify behavior), but I am thinking about starting to do so in the next

6 months. (Contemplation)

I have tried several times to (specify behavior) but am seriously thinking of trying again in the

next month. (Planning)

I have (specify behavior) regularly for less than 6 months. (Action)

I have (specify behavior) regularly for more than 6 months. (Maintenance)

![]()

![]()

![]()

AssEssmENT oF THE FAmILy

The contemporary family and the reciprocal influence of family health on individual family members reconfirm the family as the primary social structure for health promotion. Health- promoting as well as health-damaging behaviors and lifestyles learned and reinforced within the context of the family are powerful mediating factors in determining how individual members cope with health concerns and challenges. The family—the logical unit of assessment—has the primary responsibility for the following:

1. Developing self-care and dependent-care competencies of its members

2. Fostering resilience of family members to include shared values and shared goals

3. Providing social and physical resources to the family group

4. Promoting healthy individuals while maintaining family cohesion (Peace & Lutz, 2009)

Although women generally carry the major responsibility for health decision making and health education for the family, the task of fostering health and healthy behaviors should be “mainstreamed” as an integral part of family functioning. The milieu for health promotion is likely to differ significantly across families, depending on their composition, structure, socioeconomic status, living environment, culture and cultural context, and family history. A family history is a window on the individual family members’ health and an invaluable insight into the risk of inheriting specific diseases, shared environmental factors, and individual health concerns. My Family Health Portrait is an example of an Internet-based family health tool that takes about 20 minutes to complete online, or the form is available to download. The nurse may need to print a copy for the family if the family does not have access to a computer or the skills to access the form. The program assembles the information and builds a family tree. Families can share the information with other family members and enter it into the PHR. As noted by Peace and Lutz (2009), the limitation of this traditional family history representa- tion is evident when applied to diverse families. Genopro is a free (with some restrictions) commercial application for drawing genograms and is more useful in assessing nontraditional family units.

Healthy family traits and family strengths have many different modes of expression. One- parent families, blended families, unmarried parents with children, and gay and lesbian fami- lies are examples of the wide variation among families. Variations produced by transitions in family life influence the family assessment as well. Approaches to family assessment are pre- sented below.

A systems approach to family assessment includes five assessment categories: (1) individual members, (2) subsystems (developmental, biological, psychological, social characteristics), (3) interactional patterns (relationships, communication patterns, roles, and attachment patterns), (4) family processing, and (5) change or adaptive abilities (Kaakinen, Gedaly-Duff, Hanson, & Coehlo, 2009).

Three categories of processes underlie a systems model of family assessment: (1) those that regulate exchanges with the environment, (2) processes designed to prevent an overload of the system, and (3) internal processes that regulate the family’s ability to adapt and change (Clark, 2007). Assessment based on systems theory provides insight about the internal pro- cesses of the family as well as the relationship of the family to the environment and larger social system.

Family decision-making patterns in relation to health identify power structure and health care function. In a structural-functional approach to family assessment, the family is a system

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 95

96 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

with communication patterns, power structure, role structure, family values, affective function, socialization patterns, health care function, family stress, coping, and adaptation mechanisms. Family functional assessment dichotomizes instrumental functioning and expressive function- ing. Instrumental functioning refers to the routine activities of everyday living, while expressive functioning connotes emotional communication, verbal communication, nonverbal communica- tion, circular communication, problem solving, roles, control, beliefs, alliances, and coalitions (Melesis, 2012; Kaakinen, Gedaly-Duff, Hanson, & Coehlo, 2009).

The Calgary Family Assessment Model is adapted for nurses to assess families (Wright & Leahey, 2009). This model consists of family structural assessment, family developmental assessment, and family functional assessment. In structural assessment, the family’s internal structure includes family composition, rank order, subsystem, and boundary; components of the external structure are culture, religion, socioeconomic level, mobility, environment, and extended family.

To assess family development, the Calgary model reviews the current stage of the family in relation to family developmental history. Family development focuses primarily on the tradi- tional family developmental cycle, but it also includes assessment of alterations in the family developmental life cycle brought about by separation, divorce, death, single parenthood, and remarriage.

A significant gap in conducting family assessments is the lack of valid and reliable instru- ments that measure family dimensions of a health-related lifestyle. Family assessment and indi- vidual assessment are interrelated processes and complement each other. Table 4–6 lists suggested assessment areas. To provide further guidance, Chapter 5 presents a format for developing a fam- ily health promotion-prevention plan.

TABLE 4–6 Components of Family Assessment Nutrition

Meals prepared in the home are generally consistent with MyPlate.

Healthy snacks are consumed in the home.

Knowledge about healthy eating habits is shared among family members.

Mutual assistance occurs among family members for maintenance of recommended weights

and avoidance of overweight and underweight.

Family members praise each other for healthy eating.

Family members encourage each other to drink 6 to 8 glasses of water per day.

Family members base purchase decisions on nutritional labels on food.

Physical Activity

1. Many family outings consist of vigorous or moderate physical activity. 2. Exercise equipment is available within the home.

3. Use of home exercise equipment is part of “family time.”

4. Family members expect each other to be physically active.

5. A family membership is held in recreational facilities or programs.

6. Time together is seldom spent watching television or playing video games. 7. Family prefers to spend as much time out of doors as possible.

![]()

![]()

Stress Control and Management

1. Family manages time well to minimize stressful demands on members. 2. Family often relaxes, shares stories, and laughs together.

3. Emotional expression is encouraged within the family.

4. Family members share stressful experiences with each other.

5. Family members offer each other assistance with difficult tasks.

6. Family members seldom criticize each other.

7. Periods of relaxation and sleep are considered important by the family.

Health Responsibility

A schedule for preventive care visits is maintained by the family.

Family often discusses news and articles about health topics.

Family members are encouraged to seek health care early if a problem develops.

Personal responsibility for health is encouraged by the family.

Family feels a sense of responsibility for the health of the family and each member.

Health professionals are consulted about health promotion as well as care in illness.

Appropriate protective behaviors are openly discussed and encouraged (abstinence, use

of condoms, hearing protection, eye protection, sunscreen, helmets).

Family Resilience and Resources

1. Worship or spiritual experiences are a regular part of family activities.

2. Family members share a sense of “togetherness” despite difficult life events. 3. Family has a common sense of purpose in life.

4. Family members encourage each other to “keep going” when life is difficult. 5. Growth in positive directions is mutually encouraged within the family.

6. Health is nurtured as a positive family resource.

7. Personal strengths and capabilities are nurtured.

Family Support

1. Family has a number of friends or relatives that they see frequently.

2. Family is involved in community activities and groups.

3. Family members frequently praise each other.

4. In times of distress, the family can call on a number of other families or individuals for help. 5. Disagreements are settled through discussion rather than verbal abuse or physical violence. 6. Family members model healthy habits for each other.

7. Professional support services are sought when needed.

AssEssmENT oF THE commUNITy

A third essential component of assessing the health of individuals is an assessment of the com- munity in which they live, work, and play. Community assessment is a complicated and time- consuming undertaking. However, such assessments are critical to identify community strengths and resources as well as to diagnose community problems and/or deficits. Collabora- tion is required among many individuals in the community as well as health professionals.

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 97

![]()

98 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

A community analysis performed with the community, and not on or for the community, increases the likelihood of success. A team or coalition of local citizens and organizations involved in the assessment process encourages community “ownership” of the program and commitment to implement the plan.

There are four objectives for conducting a community assessment:

Identify community strengths and areas for improvement.

Identify and understand the status of community health needs.

Define improvement areas to guide the community toward implementing and sustaining

policy, systems, and environmental changes around healthy living strategies (e.g., increased physical activity, improved nutrition, reduced tobacco use and exposure, and chronic dis- ease management).

Assist with prioritizing community needs and consider appropriate allocation of available resources (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010).

Assessment involves gathering data and input on what the community needs. Assessing

community needs gives voice to citizens’ concerns and issues and allows that “voice” to influ- ence significantly the program design. Components of a community assessment include human biology, the environment, community lifestyles, and the health system. Table 4–7 lists these components.

An assessment methodology that combines at least three to four data collection methods is more likely to provide a holistic picture of the community than is an assessment that relies on only one or two approaches. Review the advantages and disadvantages of data collection methods at the CDC Healthy Communities website.

Successful implementation of community health promotion-prevention programs depends in large part on a well-developed community plan. Community-level changes such as policy are more sustainable, impact infrastructure, and support social change. For example, an effort to improve family food choices is sustainable only if healthy, affordable, and assessable food loca- tions are available in the community.

TABLE 4–7 Components of Community Assessment

Human Biology

1. Composition of population by age, gender, and race

2. Population patterns of longevity

3. Genetic inheritance patterns by gender and race

4. Disease incidence and prevalence compared to prior years, and to state and national statistics 5. Health status indicators (immunization levels, nutritional status, mobility)

Environment

Physical environment (urban/rural/suburban, housing, water supply, parks and recreation, climate, topography, size, population density, aesthetics, natural or manmade resources, goods and services, health risks)

Psychologic environment (productivity level, cohesion, mental health status, communication networks, intergroup harmony, future orientation, prevalence of stressors)

Social environment (income and education levels, employment, family composition, religious affiliations, cultural affiliations, language[s] spoken, social services, organization profile, leadership and decision-making structures)

![]()

![]()

Community Lifestyles

1. Consumption patterns (nutrition, alcohol)

2. Occupational groups

3. Leisure pursuits

4. Community health attitudes and beliefs

5. Patterns of health-related behaviors in aggregates 6. History of participation in community health action

Health System

Health care services available (health promotion, prevention, primary care, secondary care, tertiary care, mental health)

Accessibility of promotive and preventive care (low income, homeless, varying racial and ethnic groups)

Financing plans for health care

Source: Clark, Mary Jo, Community Health Nursing: Caring for Populations, 4th Edition, © 2003. Reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

A community-based action may improve the overall health of the community, but within the community, certain groups may be disenfranchised based on income level or occupation, exacerbating health disparities. Achieving health equality may be at odds with improving the overall health of the community, and priorities must be determined (Institute of Medicine, 2012). The need for transparency is paramount between the decision makers and the community to ensure that the action plan reflects the values and preferences of the citizens.

PRAcTIcE coNsIdERATIoNs IN AssEssING HEALTH ANd HEALTH BEHAvIoR

Use of assessment measures to document areas for improvement to enhance the health status of individuals, families, and communities is an important responsibility of the nurse. Assess- ment data about health status and behaviors provide the basis for clinical judgments and help plan appropriate individual, family, and community interventions. Nurses’ knowledge and influence can ensure that a portfolio of conceptually congruent assessment instruments is available and used in the work setting. The nurse must know how to administer assessment measures and explain the value of conducting systematic assessments to the client. The busy work environment may discourage the use of detailed assessments because they require time to administer and follow up. One strategy to manage the time issue is to seek innovative ways to communicate with clients through videotapes and brochures that explain assessment proce- dures. Information technology has made computerized assessment possible. Thus, clients may be able to complete self-assessments at home, as time allows, with transmission of the informa- tion by computer prior to health care visits.

Practicing nurses must keep up-to-date about new assessment measures and strategies that can be quickly implemented and yield accurate data. Nurses influence the quality of the health promotion plan of the individual, family, and community through a commitment to thorough assessment of health and health behaviors.

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 99

![]()

100 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

oPPoRTUNITIEs FoR REsEARcH IN HEALTH AssEssmENT

ANd HEALTH BEHAvIoR

Research that develops and tests assessment instruments for health and health behaviors of aggre- gates from diverse racial, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds is a high priority. Reliable and valid instruments based on theory and research are needed to perform meaningful assess- ments. Community interventions should be developed and tested in subgroups. Accurate knowl- edge of the client, family, and community will facilitate the development and implementation of successful health promotion interventions.

![]()

Summary

Health assessment at the individual, family, and community levels is time intensive and costly, so measures must reflect client characteristics and

Learning Activities

Go to the My Family Health Portrait website and record a traditional family health portrait. Examine the differences between My Family Health Portrait and the commercial application at Genopro.

Develop a list of safeguards to ensure that non- computer users are included in the health care technology environment.

Develop an assessment plan based on age-specific instruments for a child, a young adult, and an older adult.

UsingTable4–2,determineyourpercentageofbody fat and outline a personal goal based on the results.

References

American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM’s resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (9th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

ANA SmartBrief. (2012). Mobile apps seen as one of top medical trends for 2013. New York, NY: Wall Street Journal (12/31).

Bleyer, A., & Welsh, H. (2012). Effect of three decades of screening mamography on breast-cancer incidence. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(21),1998–2005.

Block, L. (2013). USPSTF mommo recommendations: Tempest in a teapot? Retrieved May 20, 2013, from HealthImaging: http://www.healthimaging.com

presenting health issues. The nurse and client must mutually establish a relevant plan to ensure its success.

5. Investigate one approach to assessing a family and discuss its strengths and weaknesses for use in the clinical setting.

6. Identify the relationship between a family and a community assessment and discuss how they affect the health outcomes of the family and community.

7. Discuss factors to consider in a community assess- ment including those influencing the extent of assessment conducted.

/topics/womens-health/breast-imaging/uspstf-

mammo-recommendations-tempest-teapot. Bulechek, G., Butcher, H., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2013). Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC)

(6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010).

Community Health Assessment and Group Evaluation (CHANGE) action guide: Building a foundation of knowledge to prioritize community needs. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Chen, Y. Y., Lu, J. C., & Jan, J. K. (2012). A secure EHR system based on hybrid clouds. Journal Medical Sys- tems, 3(5), 3375–3384.

![]()

![]()

Chung, L., Wong, F., & Chan, M. (2007). Relationship of nurses’ spirituality to their understanding and practice of spiritual care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(2), 158–170.

Clark, M. (2007). Community health nursing: Advocacy for population health (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

CMS.gov. (2009). Retrieved February 7, 2013, from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: www .cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/legislation /EHRIncentiveProgram.

Cohen, S., Kessler, R., & Gordon, L. (1997). Measuring stress. New York, NY: Oxford Press.

Derogatis, L., & Lazarus, R. (1997). Evaluating stress. The Derogatis stress profile (DSP): A theory driven aproach to stress measurement. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Folkman, S., &, Lazarus, R. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 466–475.

Frank-Stromborg, M. (2004). Instruments for clinical health-care research (3rd ed.) Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Galek, K., Flannelly, K., Vane, A., & Galek, M. (2012). The Spiritual Needs Assessment for Patients (SNAP): Development and validation of a comprehensive instrument to assess unmet spiritual needs. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 44(1), 44–51.

Gordon, M. (2009). Manual of nursing diagnosis (12th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, Inc.

Gupta, D., & Lis, C. (2010). Pretreatment serum albu- min as a predictor of cancer survival: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutrition Journal, 9, 69.

Hagan, J. F., Jr., Shaw, J. S., & Duncan, P. M. (Eds.). (2008).

Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Hendricks, C., Murdaugh, C., & Pender, N. (2006). The adolescent lifestyle profile: Development and psycho- metric characteristics. Journal of National Black Nurses Association, 17(2), 1–5.

Institute of Medicine. (2012). An integrated framework for assessing the value of community-based prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academy of Sciences.

Kaakinen, J., Gedaly-Duff, V., Hanson, S., & Coehlo, D. (2009). Family health care nursing: Theory, practice, and research. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Co.

Kressin, N., Manze, M., Russell, S., Katz, R., Claudio, C., Green, B., & Wang, M. (2010). Self-reported willing- ness to have cancer screening and the effects of sociodemographic factors. Journal of the National Med- ical Association, 102(3), 219–227.

Li, M., Friedman, B., Conwell, Y., & Fiscella, K. (2007). Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PGQ-2)

in identifying major depression in older people. Journal

of the American Geriatric Society, 55, 596–602.

Li, Y., Lee, P., Jian, W., & Kuo, C. (2009). Electronic Health Record goes personal world-wide. Yearbook of Medical

Informatics, 10(1), 40–43.

Litwinczuk, K., & Groh, C. (2007). The relationship

between spirituality, purpose in life, and well-being in HIV-positive persons. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 18(3), 13–22.

Lunney, M. (2008). The need for international nursing diagnosis research and a theoretical framework. Inter- national Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifi- cations, 19(1), 28–29.

Melesis, A. (2012). Theoretical nursing: Development and progress. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Monod, S., Rochat, E., Bula, C., & Spencer, B. (2010). The spiritual needs model: Spirituality assessment in the geriatric hospital setting. Journal of Religion, Spiritual- ity & Aging, 22(4), 271–282.

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Maas, M., & Swanson, E. (Eds.). (2013). Nursing outcomes classification (NOC) (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

National Association of Nursing Diagnosis-International. (2013). Retrieved from: www.nanda.org

Nishida, T., & Sakakibara, H. (2010). Association between underweight and low lymphocyte count as an indicator of malnutrition in Japanese women. Journal of Womens Health, 19(7), 1377–1383.

Peace, J., & Lutz, K. (2009). Nursing conceptionization of research and practice. Nursing Outlook, 57(5), 42–49.

Popkess-Vawter, S. (2008). Wellness nursing diagnosis: To be or not to be? Journal of Terminologies and Classifica- tions, 2(1), 19–25.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2009). Personal health records. Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/en/search- results.

Ryan-Wenger, N., Wilson (Sharrer), V., & Broussard, A. (2012). Stress, coping, and health in children. In V. H. Rice, Stress, coping, and health implications for nursing research, theory, and practice (pp. 226–253). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Sarason, B., Shearin, E., Pierce, X., & Sarason, J. (1987). A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoreti- cal implications. Journal of Social and Personal Rela- tions, 4, 497–510.

Sechrist, K., Walker, S., Pender, N., & Frank-Stromborg, M. (1987). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Exercise benefits/Barriers Scale. Journal of Nursing Research, 10, 357–365.

Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., & Vagg, P. (1983). Manual for state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.

The Office of Minority Health. (2013). Cultural compe- tency. Retrieved January 30, 2013, from Minority

Chapter4 • AssessingHealthandHealthBehaviors 101

102 Part2 • PlanningforHealthPromotionandPrevention

Health, Health & Human Services: http://aspe.hhs

.gov/sp/reports/2010

U.S. Department of Commerce Census. (2012). Selected

individual characteristics 2010. Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Office.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2012). The Guide to

Clinical Preventive Services. Washington, DC: Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality.

WHO Expert Consultation. (2008). Waist circumference

and waist-hip ratio. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Wright, M., Creed, P., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. (2010). The development and initial validation of a brief daily hassles scale suitable for use with adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 220–226.

Wright, L., & Leahey, M. (2009). Nurses and families: A guide to family assessment and intervention. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Co.