Protection of Pupil Rights AmendmentMany laws are in place to protect student information. For this discussion begin by reading Chapter 7, next review theModel Notification of Rights Document Under th

Chapter 7 School Safety

Introduction

Maintaining school safety has emerged as one of the most important roles of campus and district leaders. When speaking of school safety, many educators, parents, and students are referring to weapons and school shooters. Most certainly any weapon in school or any threat of violence is serious business. However, promoting school safety encompasses more than efforts to keep weapons out of school. It also includes efforts to promote a positive school culture based on security and equity. Security and equity require school leaders to take measures to reduce student victimization such as sexual harassment and bullying. This chapter addresses the utilitarian views of security and equity as well as school safety issues such as zero tolerance policies and threat assessment; student-on-student victimization such as sexual harassment, bullying, and date violence; sexting; security cameras; and Internet safety.

Focus Questions

What does the term school safety mean?

Is consistency in the application of zero tolerance policies rational?

How important is student-on-student victimization as a school safety issue?

Should district policies designed to reduce peer sexual harassment apply to gay and lesbian students?

What is dating violence? Is dating violence a school safety issue?

What are some of the legal issues associated with security cameras?

What is “sexting,” and how should schools respond to the problem?

Key Terms

Bullying

Cyberbullying

Dating violence

Deliberate indifference

Sexting

Sexual harassment

Student victimization

Threat assessment

Zero tolerance

Case Study That’s Not Fair!

Eighth graders Megan Smith and Aaron Accord had been best friends since they sat next to one another in third grade. Aaron had been taunted and bullied by other boys and girls since sixth grade. Since the beginning of seventh grade, the bullying had taken on a sexual context, and the bullies started calling Aaron “gay,” “faggot,” and similar words on a daily basis. On a least one occasion, Aaron had been punched and kicked in the boys’ restroom by three eighth-grade boys. Aaron tried to stay away from the bullies, but they seemed to find him no matter where he was in the school. Megan had defended Aaron on several occasions and had even been suspended for 2 days for fighting one of the bullies. Starting in November, Aaron began skipping school, his grades fell, and his parents became concerned that he was depressed. Both parents had taken time from their jobs to speak with middle school Principal John Armbruster about the bullying and their concerns about Aaron. Principal Armbruster acknowledged that he had heard some of the taunting and had told the students to “knock it off.” He also informed Mr. and Mrs. Armbruster that Aaron needed to “toughen up and knock the socks off of one of the bullies.”

The next day Aaron told Megan that he had brought a knife to school, and that the next time he was shoved into the boy’s restroom and punched, he was going to use the knife to defend himself. He also told Megan that he was depressed and thinking seriously about suicide so “they will not have me to pick on anymore.” Megan persuaded Aaron to give her the knife and promised to stay as close as she could to him all day. Megan planned on going to Aaron’s parents that evening to tell them that Aaron was afraid about coming to school and had brought a knife to school for protection. She was also determined to tell them what Aaron had said about suicide.

Megan was summoned to Principal Armbruster’s office right before lunch. Principal Armbruster told Megan that a student had told him that she had a knife at school. Megan tried to explain, but Principal Armbruster was not interested. He sent Megan unescorted to her locker to retrieve the knife. Megan went straight to her locker, removed the knife from her gym bag, and returned to the office. By the time she arrived, the school resource officer was in the office. Principal Armbruster informed Megan that she was going to be suspended for 10 days, referred to the police for weapon possession on campus, and recommended for a 1-year expulsion under the district zero tolerance policy. Megan shouted, “That’s not fair! If you would do your job, Aaron wouldn’t be called those names and be beaten up in the restroom!”

Leadership Perspectives

In the not-too-distant past, the issue of Megan taking a knife from her friend might have been viewed much differently than in the introductory case study. However, the Columbine High School shootings in April 1999 changed this mindset, and school safety has become a serious matter. In the MetLife Survey of the American Teacher (MetLife, 2003), students, teachers, parents, and principals overwhelmingly reported that school safety is the most important part of the principal’s job. As ISLLC Standard 3C states, school leaders must communicate to students, teachers, parents, and community members that the welfare and safety of students and staff is a primary concern and any weapon or school safety issue regardless of circumstances will be taken seriously. Anything less would be a breach of public trust.

ISLLC Standard 3C

Consequently, the need to balance the authority of school leaders with the responsibility to maintain order in a positive and caring school often generates difficult choices for school administrators. Principal Armbruster in the case study “That’s Not Fair!” is faced with just such a challenge. Principal Armbruster is required to take school safety seriously. Under state and federal law, it is possible that Megan could be expelled for up to one school year. One of the common themes of this text is that Megan, like all students, has the right to be treated fairly simply because she is a student and a person. Megan may very well have had a good reason for doing what she did. After hearing about Aaron’s parents’ conversation with Principal Armbruster, she may have believed that school administrators would punish Aaron rather than the bullies. She may have been trying to protect her friend the only way she knew how. After all, she is a young teenager and most likely has little experience with serious issues of sexual-orientation bullying and suicide ideation. Whatever decisions are made by school officials should be defensible. They should balance good order and discipline with Megan’s basic right to be treated fairly. This balance can be difficult. But, ISLLC Standard 5 encourages Principal Armbruster to reflect on his decisions and think about how an understanding of ethical behavior impacts his leadership.

ISLLC Standard 3

ISLLC Standard 5

ISLLC Standard 5

ISLLC Standard 5

The Purpose of Policy

According to the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1970), the purpose of all governmental action should be to produce benefit, good, or happiness and to prevent evil, mischief, or unhappiness to the individuals whose interest is being considered. One theme throughout this text is that all good schools are reasonably orderly. Bentham uses the term greatest happiness principle or utility to define or quantify this concept. Utility depends on two basic principles: security and equity (fairness). Security in Bentham’s view is a means to the end and a necessary precondition for the maximization of the greater good. ISLLC Standard 3C is about security. Another theme throughout this text is the concept of fairness or equity. Fairness, although subservient to security, also serves as a precondition for the maximization of happiness. In the utilitarian view of Jeremy Bentham, the primary purpose of district or campus policy should be to promote the principles of security and equity. In other words, the purpose of all school district policy should be to promote the utility (or the greater good) of the school community.

ISLLC Standard 3.0

ISLLC Standard 3C

ISLLC Standard 5

To Bentham, a community is a fictitious body, composed of the individual persons who are considered as members. For example, the school community is composed of students, teachers, administrators, school board members, parents, and others who are affiliated, even temporarily, with the district or campus. The general happiness of the community can only be considered in terms of the individuals who are members of the community. In other words, the utility of the community cannot be considered without considering the utility of the individual members of which the community in question is composed. This is an important point. Utility is measured not by some vague concept of what is good for the community, but rather by what is in the best interests of the individual members of the community.

Utility is not possible without security. The principle of utility depends on the deliberate creation of policy and practice specifically implemented to provide for security. Security results from policy that averts pain or danger. For Aaron in the opening case study “That’s Not Fair,” this would mean policy and practice designed to protect him and other students from ongoing bullying. Without this basic principle in place, all other efforts to promote equity and the greater good of the school community will surely fail. Rules against fighting, appropriate supervision of students, and efforts to prevent bullying are examples of policy implemented to promote security and avert pain. For example, Aaron fears for his safety in school and brings a knife for protection. Utility is also not possible without fairness. In Megan’s case she believes she is not being treated fairly because she was trying to help her friend. Bentham, and common sense, recognizes that not all pain or danger can be avoided. In fact, the act of making policy to provide security to prevent pain or danger creates conditions that may result in punishment (or pain) for those individuals who violate the policy. However, Bentham clearly recognized the need for proportional punishment for transgressors as a necessary component of policy designed to promote community utility.

School Safety

Violent deaths—defined as a homicide, suicide, legal intervention (involving a law enforcement officer), or unintentional firearm-related death—in which the fatal injury occurred on the campus of a functioning elementary or secondary school in the United States are rare but tragic events. For example, in the 2007–2008 school year, 1,701 youth ages 5 to 18 were victims of homicide or suicide. Of this number, 21 homicides and 5 suicides occurred at school. This number, although significant, equates to 1 homicide or suicide of a school-age youth at school per 2.1 million students enrolled during the 2008–2009 school year. This statistic has remained virtually unchanged from 1992 to 2009. In fact, youth homicides and suicides are significantly more likely to occur away from school than at school (Robers, Zhang, & Truman, 2010).

In spite of these facts, concerns over weapons and school shooters remain at the forefront. Peterson, Larson, and Skiba (2001) write:

Whereas school shootings involving multiple victims are still extremely rare . . . these statistics are hardly reassuring as long as the possibility exists that it could happen in our school, to our children. Whatever the absolute level of school violence and disruption, it is clear . . . schools and school districts must do all they can to ensure the safety of students and staff. (p. 12)

As ISLLC Standard 3 indicates, school safety is indeed serious business, and maintaining safe schools is a significant part of the role of school administrators. Therefore, school districts and school administrators have been empowered by a variety of federal, state, and local laws and policies with the intention of promoting school safety. At the federal level, the most visible school safety law is the Gun-Free Schools Act (GFSA, 1994). The GFSA was reauthorized as part of No Child Left Behind (NCLB, 2001). GFSA requires that each state have a law that requires all local education agencies (LEAs) to expel from school for at least 1 year any student determined to have brought a firearm to school or to have possessed a firearm at school. GFSA allows local school administrators to modify (for example, shorten) any disciplinary action for a firearm violation on a case-by-case basis. The primary purpose behind this provision is to allow school district administrators or boards of education to take the circumstances of the infraction into account and, if necessary, to ensure that the legal requirements of IDEA are honored. This information must be reported to the U.S. Department of Education and must include the name of the school concerned, the number of students expelled from each school, and the type of firearms involved.

ISLLC Standard 3

NCLB also includes the following clarifications:

Students must be expelled for possessing a gun in school, not just for bringing a gun to school.

Any modifications to expulsions under GFSA must now be in writing.

NCLB makes exceptions for lawfully stored firearms inside a locked vehicle on school property, and firearms brought to school or possessed in school for activities approved and authorized by the district.

“Firearm” includes not only guns but also other dangerous devices such as bombs, rockets, and grenades.

Disciplinary action taken against Individualized Education Program (IEP) students must be consistent with the provisions of IDEA.

Expelled students may be provided with educational services in an alternative setting.

GFSA data indicate that these efforts may be having a positive effect. There has been a general downward trend in the rate of student expulsions for weapon possession per 100,000 students nationwide since the 1998–1999 school year. Recent data indicate an 11% reduction in expulsions per 100,000 students from the 2005–2006 to the 2006–2007 school years. Some of this reduction may be attributable to an increase nationally in modifications to the 1-year expulsion requirement for weapon possession. In school year 1997–1998, just 30% of expulsions for students determined to have brought a firearm to school were modified (e.g., reduced below the 1-year standard). During 2005–2006, 45% of expulsions for students determined to have brought a firearm to school were modified. In 2006–2007, more than half (53%) were modified (U.S. Department of Education, 2010).

State legislatures have also passed numerous school safety measures. Since 2006, virtually every state legislative body has passed some form of school safety legislation (Education Commission of the States, n.d.). For example, Missouri law empowers school districts to expel or deny admission to any student charged or convicted of a list of violent acts committed anywhere (RSMo 167.171.3).

School District Responses

Individual schools and school districts have responded similarly and increased security measures. Students ages 12 to 18 report an increase in security cameras to monitor the school (from 39% in 1999 to 66% in 2007), security guards and other assigned police officers (54% in 1999 to 69% in 2007), and locked entrance or exit doors during the day (from 38% in 1999 to 61% in 2007) (Robers et al., 2010). School districts have also uniformly enacted “zero tolerance” policies in response to GFSA for students possessing a weapon in school. Zero tolerance is generally defined as a school district policy that mandates predetermined consequences or punishment for specific offenses, regardless of the circumstances, disciplinary history, or age of the student involved. The stated purpose of zero tolerance policies is to send a clear and consistent message that school officials are still in charge and that certain proscribed acts (weapon possession, threats of violence, drugs or alcohol, fighting, or even tardiness) will not be tolerated (Education Commission of the States, 2002).

Support for zero tolerance, once almost universal, now appears to be waning in many states. However, as long as school administrators follow school district policy and observe all due process rights, courts have been supportive of zero tolerance suspensions even when the expulsion seems, at least on the surface, to defy rationality. For example, the Third Circuit Court recently upheld the 3-day suspension of a kindergarten student for saying, “I’m going to shoot you” while playing “guns” with friends at recess (A. G. v. Sayreville Board of Education, 2003). The court reasoned that the student had knowledge of the underlying conduct for which he was sanctioned. The 10th Circuit Court took a similar position when a senior student (Butler) was expelled in spite of a hearing officer’s finding that he had unknowingly brought weapons to school when he borrowed his brother’s car, concluding that (1) the district has a legitimate interest in providing a safe environment for students; (2) based on this legitimate interest, there is a rational basis for the suspension of Butler when he should have known he brought a weapon onto school property; and (3) the district’s decision was not arbitrary, nor did it “shock the conscience.” Consequently, the decision to expel Butler under the circumstances, even for 1 year, does not violate the substantive due process rights of Butler (Butler v. Rio Rancho, 2003).

Generally courts have not held school administrators liable for school shootings or injuries as a result of weapons as long as reasonable action was taken. For example, a federal district court in Colorado has dismissed numerous suits against school and law enforcement officials in the aftermath of the Columbine High School shootings. In another example, John Smith brought a gun to school and fatally shot one of his first-grade classmates (McQueen v. Beecher Community Schools, 2006). Certainly, John Smith’s parents, teachers, his principal, and the district superintendent have spent countless hours second-guessing the decisions that led to this incident. However, absent any evidence of deliberate indifference on the part of the school district, the court could find no reason to hold the teacher, principal, or district superintendent liable for the shooting.

Consistency May Not Always Be Rational

Although there is little ambiguity regarding the expulsion of truly dangerous students, some school district applications of zero tolerance policies cast doubt on the wisdom of school administrators. The case of Benjamin Ratner serves as a classic example (Ratner v. Loudoun County Public Schools, 2001). In a case similar to the opening case study “That’s Not Fair!” a young friend informed Benjamin that she had inadvertently brought a knife to school in her binder that morning. Benjamin knew the student and was aware of previous suicide attempts. He put the binder in his locker with the intent of telling both his and her parents after school. School officials obtained knowledge of the knife. Benjamin was suspended for 10 days for possessing a knife on school grounds. He was notified 2 days later that he was being suspended indefinitely pending further action by the school board. On judicial appeal, the Fourth Circuit Court refused to consider Benjamin’s case, finding he had been given constitutionally sufficient, even if imperfect, due process. In a concurring opinion in Ratner, Judge Hamilton questioned the wisdom of the decision: “Each (Benjamin, his family, and common sense) is the victim of good intentions run amuck.” It is easy, however, to find fault in Benjamin’s choice not to give his friend’s binder to a principal, a counselor, or a trusted teacher.

The problem is straightforward: Not expelling a dangerous student carries significant consequences for all concerned. But, are all weapon possessions created equal? Is consistency rational? As the Sixth Circuit Court pointed out, consistency is not a substitute for rationality, and a school board may not absolve itself of its legal and moral obligation to determine whether students intentionally committed the acts for which their expulsions are sought by hiding behind a zero tolerance policy intended to make the student’s knowledge a non-issue (Seal v. Morgan, 2000).

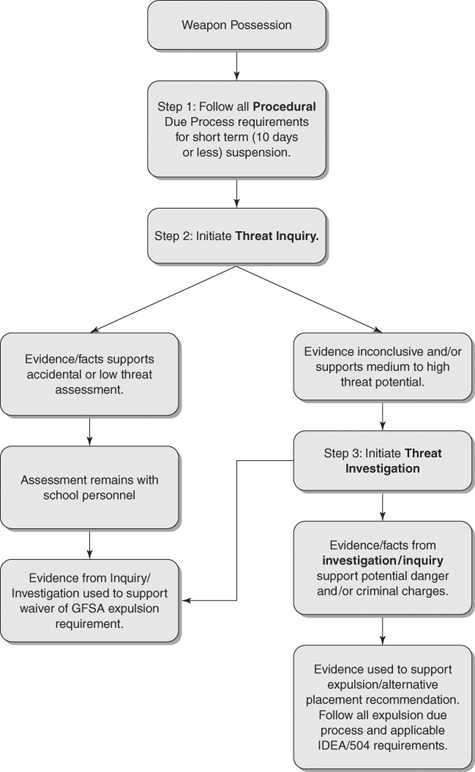

If consistency is not always rational, how may school leaders meet their legal obligation to keep schools safe? The answer may be a well-established threat assessment policy that is publicly justified and supportive of a fair system of cooperation. In a U.S. Secret Service/Department of Education study of targeted school violence, Fein and colleagues (Fein et al., 2004) present a threat assessment model based on an analysis of the facts and evidence of behavior in a given situation. Weapon possession should never be taken lightly. However, the central question of a threat assessment is whether a student poses a threat, not whether the student made a threat. Threat assessment is composed of two parts: threat inquiry and threat investigation. Both use fact-based evidence developed and gathered from a variety of sources to justify return to school, disciplinary decisions, or potential criminal charges.

The first step, threat inquiry, is carried out by district officials or a school-based threat assessment team. Assume, for example, that an initial inquiry determines that the student, such as Megan Smith in the introductory case study “That’s Not Fair” poses little if any threat to others. Evidence gathered can be used to justify an alternative punishment such as short-term suspension, in-school suspension, or short-term referral to an alternative placement. However, if the initial threat inquiry is inconclusive or supportive of a medium or high threat assessment, the more formal threat investigation is activated (Fein et al., 2004). Common sense indicates that activation of the threat investigation process should be accompanied by short-term (10 days or less) or emergency expulsion of the student. Threat investigation would include local law enforcement, a more thorough internal review of the factors surrounding the incident, and possibly referral to a local counseling agency for their assessment. It is important to note that threat inquiry should precede threat investigation. The threat assessment model is illustrated in Figure 7-1.

FIGURE 7-1 Threat assessment.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Have a clear and unambiguous policy regarding threats of violence and weapons in school. Leave no doubt in anyone’s mind that weapons in school will be taken seriously and punishments will follow.

Recommend the adopting of a formal board of education policy authorizing school officials to conduct a threat assessment. Excellent guidelines for policy formulation are presented on pp. 34-35 of Threat Assessment in Schools (Fein et al., 2004). This publication is available free of charge from the U.S. Department of Education.

Develop objective criteria to use in suspension or expulsion decisions. Criteria could include factors surrounding the incident, previous behavior of the student, relative severity or threat of the incident, and evidence of school support.

Work with students, parents, and community groups to articulate and explain school district policy and practice.

Do Not:

Abandon common sense. The provision to modify any disciplinary action for a weapon violation in GFSA (and confirmed in NCLB) is there for a reason.

Student Victimization

Unfortunately, student victimization in various forms is relatively common in public schools. Student victimization may include bullying, intimidation, gender-based sexual harassment, sexual harassment based on real or perceived sexual orientation, dating violence, and sexting. Victimization can occur in the classroom, in school hallways, on school playgrounds, in locker rooms, at school-sponsored events, in cyberspace, in social media, and by cell phone. Student victimization can be perpetrated by peers, older students, and adults in the school. Victims may experience a decline in grades, increased absenteeism, a failure to develop positive self-esteem, withdrawal and depression, and suicide ideation. Therefore, efforts to address student victimization should be part of any comprehensive approach to school safety (Stader, 2011).

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment is defined as unwanted or unwelcome behavior of a sexual nature. Sexual harassment may include unwelcome sexual advances, request for sexual favors, and other conduct of a sexual nature. Sexual violence (i.e., sexual assault or coerced sex) is also prohibited by Title IX (Dear College, April 4, 2011). Title IX protects students from sexual harassment in all school programs or activities, regardless of who the harasser may be, as long as the school maintains control of the program or activity. For example, schools may be liable for sexually harassing behavior by a teacher, an administrator, a custodian, or another student anywhere on school grounds, at school-sponsored events, or on a school bus. Schools may also be liable for sexual harassment or assault after school hours when the behavior involves teachers and students. For example, a male 11th-grade science teacher in Georgia used a fictitious scholarship program as a scheme to lure students to his home. At least one of the students was sexually assaulted by the teacher. The District Court held that the teacher used his position of authority to give a stamp of legitimacy to the scholarship program (Hackett v. Fulton County School District, 2002).

Two types of sexual harassment have been established by law: quid pro quo and hostile environment.

Quid Pro Quo Harassment:

Sexual harassment in which the satisfaction of sexual demands is made the condition of some benefit. For example, quid pro quo harassment occurs when a school employee causes a student to believe that he or she must submit to a sexual demand in order to participate in a school program, or in return for a favorable educational decision or a favorable grade in a course. Whether the student submits or not is beside the point. The fact that the demands were made makes the conduct unlawful (Garner, 2006).

Hostile Environment Harassment:

A hostile environment is created when unwelcome sexually harassing conduct becomes so severe, persistent, or pervasive that it affects a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from an educational program or activity or creates an intimidating, threatening, or abusive educational environment. Hostile environment harassment may be created by school employees, other students, school volunteers, cafeteria workers, and so on (Garner, 2006).

Liability under Title IX

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is responsible for the enforcement of Title IX. OCR prefers that claims be settled in a peaceful manner. OCR does not seek monetary relief for victims of sexual harassment. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has established that a damages remedy is available to students for an action brought to enforce Title IX (Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools, 1992). This case involved a high school student who alleged that she was subjected to continual sexual harassment and abuse, including coercive intercourse, by a male teacher at the school. The student also alleged that other teachers and the school principal had knowledge of the sexual abuse but took no action in response to this knowledge.

A few years later the U.S. Supreme Court considered the question of what criteria should be met before monetary damages were available to students subjected to abuse by school employees (Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School, 1998). This case differs from Franklin in that a student had sexual relations with one of her teachers but did not report the relationship to school officials. The police encountered the teacher and student having sexual intercourse in the teacher’s car and arrested the teacher. The Court held that monetary damages were recoverable for teacher-on-student harassment when:

A school district official who at a minimum has authority to institute corrective measures on the district’s behalf has actual notice of the allegations, and

The school official or officials are deliberately indifferent to the teacher’s misconduct.

These criteria establish that school districts and campus administrators can be held accountable for respondeat superior [Latin for the doctrine holding the “employer liable for the employee’s wrongful acts committed within the scope of employment” (Garner, 2006, p. 12)] of an employee’s quid pro quo or hostile environment sexual harassment if the employer had reasonable notice of the harassment and filed to take appropriate corrective action. In essence, the district is not liable as long as an official who has the authority to institute corrective measures takes action as soon as the teacher-on-student sexual harassment becomes known to the official (see Henderson v. Walled Lake Consolidated School District, 2006; P. H. v. The School District of Kansas City, Missouri, 2001). Officials who have authority to institute corrective measures include campus principals, assistant superintendents, and superintendents.

Once actual notice is established, responding appropriately to allegations of teacher-on-student sexual misconduct is essential. For example, a principal’s failure to adequately respond to parental complaints regarding a fourth-grade teacher’s sexual abuse of their son resulted in a $400,000 jury verdict against the school district (Warren v. Reading School District, 2002). And, not surprisingly, a trial court held that the failure to investigate or confront a female teacher after various school personnel complained to the principal that the teacher was having sex with male students constituted an “unreasonable response” (Doe v. School Admin. Dist. No. 19, 1999).

Linking to Practice

Do:

Ensure that employee training includes warnings that appropriate boundaries with students should be established. These boundaries should be made clear to all students, with particular attention to middle school and high school students.

Also make sure that employee training includes examples of behaviors that may indicate inappropriate boundary crossing by teachers, students, or others.

Be sure that school district policy provides clear reporting guidelines and contact information for faculty, parents, and students to report incidents of suspected boundary crossing or suspected sexual misconduct.

Do Not:

Ignore warning signs of inappropriate boundary crossing by employees or students. An inquisitive mindset is important. See Investigation of Employee Misconduct in Chapter 11 (Teacher Employment, Supervision, and Collective Bargaining).

Do Not:

Ignore warning signs of inappropriate boundary crossing by employees or students. An inquisitive mindset is important. See Investigation of Employee Misconduct in Chapter 11 (Teacher Employment, Supervision, and Collective Bargaining).

Student-on-Student Sexual Harassment

The U.S. Supreme Court next considered the circumstances under which a district could be held monetarily liable for failure to adequately respond to student-on-student sexual harassment (Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, 1999). In a decision similar to Gebser v. Lago Vista (1998), the Court found that under certain circumstances districts could be held monetarily liable for student-on-student (peer) sexual harassment. The case before the Court involved a prolonged pattern of alleged sexual harassment of LaShonda Davis by a fifth-grade classmate. During this several-month period, LaShonda and her mother reported incidents to at least two classroom teachers and a physical education teacher on several occasions. The incidents finally ended in mid-May when the male student was charged with, and pleaded guilty to, sexual battery. However, during this time period LaShonda’s grades suffered, and at one point her father discovered a suicide note. It was also alleged that the male student was not disciplined during the period of prolonged harassment. In addition, no effort was made to separate the two students, and it was only after several months that LaShonda was allowed to change her seat so as not to be near the male student.

The Court found school districts to be liable for student-on-student sexual harassment under the following conditions:

School personnel have actual knowledge of the harassment, and

School personnel are deliberately indifferent to the sexual harassment, and

The harassment is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it can be said to deprive the victim(s) of access to the educational opportunities or benefits provided by the school.

The Court pointed out that the harassment must take place in a context subject to the school district’s control. In the Court’s reasoning, this makes sense in that school personnel should not be directly liable for indifference where the authority to take remedial action is non-existent. This indicates that school personnel would not be responsible for addressing harassing behavior that occurs at, for example, a local mall or a privately sponsored event not under the control of the school. However, school personnel would be responsible for addressing harassing behavior at school dances, during recess, on school buses, or for behavior that may “spill over” into the school context.

In order to prevail in a monetary-damages suit, the student must demonstrate all three prongs established by the Court. First, school officials must have actual notice or knowledge of the alleged harassing behavior. In adult–student harassment, the school authority must be someone who at a minimum has the authority to initiate remedial action. In most cases, this would include the campus principal and most certainly the district superintendent. However, when considering student-on-student harassment, teachers also have the authority to discipline, correct, or refer students to administrative personnel. Regardless, once appropriate school officials have knowledge of the alleged behavior, Davis imposes a duty to act.

Next, school officials must demonstrate deliberate indifference or take actions that are “clearly unreasonable.” The majority in Davis saw no reason why a court could not distinguish a response that is “clearly unreasonable” from one that is “reasonable.” In response to some of the concerns of the dissenting justices, the majority attempted to point out that schools are not like the adult workplace, and every immature act of every student in school was not grounds for suspension or expulsion. Children and young adults are still learning appropriate behaviors and during this learning process may interact from time to time in a manner that would be unacceptable to adults. School administrators were to continue to use good judgment and develop age-appropriate and educationally sound approaches to confronting the problem. To further emphasize this point, the Court restated the concept from New Jersey v. T. L. O. (1985) that judges should refrain from second-guessing the disciplinary actions taken by school administrators. Consequently, school administrators should continue to enjoy flexibility in disciplinary decisions involving peer harassment as long as their actions are not deemed “deliberately indifferent.” In short, all that Davis requires is that the response not be clearly unreasonable (Clark v. Bibb County Board of Education, 2001; Gabrielle M. v. Park Forest-Chicago Heights, 2002; Soper v. Hoben, 1999).

Although no specific response is required, the school must respond and must do so reasonably in light of the known circumstances. Thus, if a school official has knowledge that the remedial action taken is not effective, then reasonable action in light of these circumstances is required. In other words, if a school official knows that efforts to remediate are ineffective, yet continues to use these same methods to no avail, the official has failed to act reasonably in light of the known circumstances. For example, in repeated incidents of sexually harassing behavior, simply continuing to “talk to” the offending students will not pass as a reasonable response (Vance v. Spencer County Public School District, 2000). It would seem from this argument that a flexible policy that takes into consideration the age of the students involved, the severity of the harassment, and previous efforts to remediate should define the term reasonable response.

Finally, the harassment must rise to the level of being so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it can be said to deprive the victim(s) of access to the educational opportunities or benefits provided by the school. For example, the Sixth Circuit Court found that when sexually harassing behavior becomes so pervasive that it forces the victim to leave school on several occasions, results in a diagnosis of depression, and ultimately forces the victim’s withdrawal from school, the behavior rises to the level of systematically depriving the victim access to an education (Vance v. Spencer County Public School District, 2000). Consequently, the Sixth Circuit Court confirmed a $220,000 jury award in this case. Using a similar approach, the 11th Circuit Court (Hawkins v. Sarasota County School Board, 2002) ruled that female students were not entitled to damages for student-on-student sexual harassment. The court found that although the harassment was persistent and frequent, none of the students’ grades suffered, no observable change in their classroom demeanor occurred, and none of the students reported the harassment to their parents until months had passed.

Linking to Practice

School districts should develop well-articulated mechanisms for reporting sexual harassment. Each campus should have a Title IX coordinator. Teachers and other adults in the school should be required to report incidents or reports of sexual harassment to the campus Title IX coordinator. The report should be investigated as soon as practical. Evidence of teacher-on-student harassment should be reported to the district Title IX coordinator immediately.

School officials should flexibly apply response mechanisms to both the victim and perpetrator, taking into account the ages of the students involved and the context of the behavior. For example, a first-grader who kisses another first-grader on the cheek during recess may be guilty of breaking school playground rules but is not guilty of sexual harassment.

All incidents of suspected harassment and the response to the suspected behavior should be carefully documented.

District- and campus-based school and community partnerships should be formed to explain reporting and disciplinary policies and prevention efforts and to solicit input and support from the local community.

Sexual Orientation Harassment

As of 2005 only nine states (California, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin) and the District of Columbia have statutes specifically protecting students on the basis of sexual orientation and/or gender identity (Kosciw & Diaz, 2006). Courts in the states with Non-discriminatory laws have found school districts liable for violating state sex discrimination policies or for a failure to protect students from sexual orientation harassment. For example, the Supreme Court of New Jersey upheld the findings by the director of the Division on Civil Rights that Toms River School District violated the state Law Against Discrimination by not protecting L. W. from ongoing peer harassment based on his sexual orientation (L. W. v. Toms River Regional Schools Board of Education, 2005). Following similar logic, a Massachusetts appeals court held that a 15-year-old transgender eighth-grader has the right under state law to attend school wearing clothing that expresses his female gender identity (Doe v. Yunits, 2000).

It seems logical to assume that cases similar to Toms River will increase as more state legislatures pass non-discrimination laws. However, at present, most student-on-student sexual orientation harassment cases have been heard in federal court. Federal courts generally consider either equal protection or Title IX when deciding student-on-student sexual orientation harassment cases. An equal protection claim requires the student to show that school officials did not abide by antiharassment policies when dealing with sexual orientation harassment, that officials were deliberately indifferent to the harassment, or that the student was treated in a manner that is clearly unreasonable. For example, in Nabozny v. Podlesny (1996), the Seventh Circuit Court held that school administrators are not immune from an equal protection claim involving student-on-student sexual orientation harassment. In this case, student Nabozny was repeatedly subjected to verbal and physical abuse because of his sexual orientation. School administrators had a policy of investigating and punishing student-on-student battery and sexual harassment, but allegedly turned a deaf ear to Nabozny’s complaints. Despite repeated reporting by both the student and his parents to several school officials including principal Podlesny, little or no action was taken to either discipline the offending students or protect Nabozny (despite promises to the contrary) from the students in question. In fact, evidence suggests that some of the administrators themselves mocked Nabozny’s predicament. The harassment (including a mock rape and a physical assault) resulted in Nabozny making two suicide attempts, running away from home, and eventually dropping out of school. On review, the Seventh Circuit Court reversed and remanded Nabozny’s equal protection claim, stating, “We are unable to garner any rational basis for permitting one student to assault another based on the victim’s sexual orientation.” In November 1996, the district agreed to a $900,000 settlement with Nabozny (Bochenek & Brown, 2001). Rational basis is the lowest form of scrutiny for an equal protection claim. A district must be particularly negligent under the rational basis test. Therefore, a finding under this standard by the court surely expedited the large settlement with Nabozny.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals followed similar logic and a rational basis standard of review to find ample evidence of deliberate indifference to the ongoing sexual orientation harassment of six high school students (Flores v. Morgan Hill, 2003). Without admitting wrongdoing, Morgan Hill School District agreed to a $1.1 million settlement and a promise to create a mandatory training program to promote gay tolerance (American Civil Liberties Union, 2004).

In 2000, two separate federal district courts (California and Minnesota, respectively) decided that schools could be held liable under Title IX for acting with “deliberate indifference” toward students who have reported persistent and severe homophobic harassment at school (Montgomery v. Independent School District No. 709, 2000, and Ray v. Antioch Unified School District, 2000). As the California Federal District Court stated:

[There is] no material difference between the instance in which a female student is subject to unwelcome sexual comments and advances due to her harasser’s perception that she is a sex object, and the instance in which a male student is insulted and abused due to his harasser’s perception that he is a homosexual, and therefore a subject of prey. In both instances, the conduct is a heinous response to the harasser’s perception of the victim’s sexuality, and is not distinguishable to this court.

(Ray v. Antioch Unified School District, 2000)

These decisions established important precedents for the application of Title IX sexual harassment standards to several cases that followed (Meyer & Stader, 2009). In fact, students have been remarkably successful in claiming deliberate indifference to sexual orientation harassment under Title IX. For example, school districts have settled for $451,000 (Henkle v. Gregory, 2001; Lambda Legal, 2001), $27,000 (Doe v. Perry Community School District, 2004), and $440,000 (Theno v. Tonganoxie, 2005).

In summary, school districts have been held liable for violating state non-discrimination laws, for not equitably enforcing their own rules, and/or for their deliberate indifference to the sexual orientation harassment of students (Meyer & Stader, 2009). A common theme among these cases is a failure to take reasonable action once the sexual orientation harassment became known to school officials. Therefore, it is incumbent on school districts to take affirmative steps to provide a positive, supportive, and safer school culture for all students.

Teacher or Other Adult Harassment of Lgbt Youth

The value of teacher and other adult support for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students cannot be underestimated. In a study of LGBT youth, Human Rights Watch found that in virtually every case where these students reported a positive school experience, they attributed that fact to supportive teachers (Bochenek & Brown, 2001). However, this is not always the case. For example, Thomas McLaughlin appealed to a federal district court in Arkansas alleging that his choir teacher at Jacksonville Junior High School (Pulaski County, Arkansas) asked him if he was gay (McLaughlin v. Pulaski County, 2003). When he responded yes, she told Thomas that she found homosexuality “sickening,” asked Thomas if he knew what the Bible says about homosexuality, and offered him some scriptures. Thomas also alleged that his computer teacher called him “abnormal” and “unnatural.” When Thomas protested, he was sent to an assistant principal, who preached religious views about homosexuality. At some point Thomas was suspended for 2 days, allegedly for talking to other students about being made to read the Bible by the assistant principal, and later threatened with 4 more days for complaining about his 2-day suspension. The district agreed to a $25,000 settlement with Thomas and his attorneys (Trotter, 2003). This case illustrates that this district court, at least, views adult-on-student sexual orientation harassment similarly to student-on-student sexual orientation harassment. The case also puts school districts (at least in the Eighth Circuit) on notice that this type of harassment will not be tolerated.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Review district policy and sexual harassment training practices for district personal. Be sure the training includes student-on-student sexual harassment based on sexual orientation. The training should provide examples of student homophobic behaviors that may rise to the level of hostile environment. Affirm that the reporting procedures for heterosexual harassment apply to harassment based on real or perceived sexual orientation.

Review school district policy and supervision models to ensure that they prohibit homophobic remarks by school employees. Educate faculty and staff on the potential harmful effects of peer harassment on LGBT students and the importance of support for these students.

Insist that campus administrators apply the same disciplinary standards to student-on-student harassment based on sexual orientation that are applied to all sexual harassment or sexual assault incidents reported in the school. Affirm that once campus administrators have actual knowledge or notice of student-on-student harassment, district policy imposes a duty to act.

Collect data to determine the extent of peer harassment based on sexual orientation in district schools. Set annual measurable objectives and research- and literature-based intervention strategies designed to decrease the incidence and severity of peer harassment based on sexual orientation.

Ensure that students are aware of policies protecting students from peer harassment and that these polices will be enforced.

Bullying

It is well established that peer bullying, especially when it is ongoing and frequent, is a stressful experience with a negative impact on feelings of emotional safety, regardless of the mental health of the victim (Newman, Holden, & Delville, 2005). A wide variety of negative behaviors fall under the bully label including social exclusion, intentional damage to personal property, and hate-filled language and graffiti (Devine & Cohen, 2007). Unfortunately, peer bullying is a relatively common occurrence in schools. In 2007, about 32% of students ages 12 to 18 reported being bullied at school. Of the students who reported being bullied, 21% reported being made fun of, called names, or insulted, 18% reported they were the subject of rumors, 6% were threatened with harm, 11% reported being pushed, shoved, tripped or spit on, 4% were tried to make do things did not want to do, 5% were excluded from activities on propose, 4% had property destroyed, 2% reported hurtful information on the Internet and another 2% reported unwanted contact on Internet. The majority (79%) reported being bullied inside the school and 23% said that they were bullied outside on school grounds. In addition, 7% reported that they had avoided a school activity or one or more places in the school in the past 6 months because of fear of attack or harm (Robers et al., 2010).

Although somewhat disputed, the link between school bullying and school shooters served as a catalyst for virtually every state legislative body to pass some form of anti-bullying law in the years after 2002. These laws vary considerably in content and scope, in the legal requirements that school districts must meet, in requirements placed on the state board of education, and in defining bullying. Regardless, once appropriate school officials have knowledge or reasonably should have known of alleged bullying, state antibullying laws and school board policies impose a duty to act. Bullying or harassment based on race, color, national origin, sex, or disability may also violate civil rights statues (i.e., Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; Title IX, Section of the Rehabilitation Act of 1972; and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act), enforced by the Office for Civil Rights (Dear Colleague, October 26, 2010). If an investigation into harassment that violates any of these civil rights has occurred, “a school must take prompt and effective steps reasonably calculated to end the harassment, eliminate any hostile environment, and prevent the harassment from recurring” (Dear Colleague, October 26, 2010, pp. 2-3).

Clear legal guidelines regarding school district responsibility for peer bullying are not currently available. However, numerous suits are moving through various federal and state courts. For example, according to the Courthouse News Service (www.courthousenews.com), Texas parents blame their 13-year-old son’s suicide on their school district’s deliberate indifference to the ongoing bullying he was experiencing (Ross, 2011). Bullying creates a hostile environment, and although little case law is available, it seems reasonable to assume that when ruling on these cases, courts will depend on the Davis standards of knowledge, deliberate indifference, or failure to take reasonable action, and whether the bullying was severe and pervasive enough to interfere with the victim’s education. For example, a federal district court in New York used the hostile environment framework and the deliberate indifference of school personnel to find that ongoing peer bullying denied a disabled student a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) under IDEA (T. K. v. New York City Department of Education, 2011).

Cyberbullying

Feinberg and Robey (2008) define cyberbullying as follows:

[It is] sending or posting harmful or cruel text or images using the Internet (e.g., instant messaging, e-mails, chat rooms, and social networking sites) or other digital communication devices, such as cell phones. It can involve stalking, threats, harassment, impersonation, humiliation, trickery, and exclusion. (p. 10)

Several states have added cyberbullying laws to their already existing antibullying laws. These laws, however, do not create firm ground for school leaders to discipline students for cyberbullying that occurs or originates off school grounds. Unfortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court has not explicitly addressed technology-enabled speech originated off-campus, and lower court decisions have been inconsistent regarding a school district’s legal rights and/or obligation to address off-campus cyberbullying. This leaves school leaders in a legal quandary (Conn, 2010).

Conn and Brady (2008) report that several school districts have suspended or expelled students for cyberbullying. However, it is well established that student off-campus speech has more protection than on-campus speech. Therefore, school districts generally must demonstrate that student off-campus speech is a true threat or creates substantial disruption on campus, or that substantial disruption to good order and discipline could reasonably be forecast. For example, a high school student sued her school district for suspending her for posting a video clip made off-campus on a website in which students made derogatory, sexual, and potentially defamatory statements about a 13-year-old classmate. A federal district court held that the suspension violated the First Amendment rights of the suspended student, stating that at most, the school had to address the concerns of an upset parent, a student who temporarily refused to go to class, and five students missing some undetermined portion of their classes, and a fear that students would “gossip” or “pass notes” in class did not rise to the level of a substantial disruption (J. C. ex rel. R. C. v. Beverly Hills, 2010).

The Office for Civil Rights has indicated that off-campus sexual harassment may also create a hostile environment on-campus in certain situations. It would seem reasonable to assume that similar logic could be applied to off-campus bullying or cyberbullying. Therefore, if evidence indicates that the off-campus conduct has created a hostile learning environment at school, OCR rules create an obligation to act and take steps to protect the student from further bullying or retaliation from the perpetrator (Dear Colleague, 2011, April 4). For example, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the 5-day suspension of a high school student who created a MySpace.com webpage called “S.A.S.H.,” which stands for “Students Against Sluts Herpes.” The student invited approximately 100 people to her MySpace “friends” list to join the group. The website was largely dedicated to ridiculing a fellow student in the school. The court, citing Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and Donniger v. Niehoff (2008), found that the postings were “sufficiently connected to the school environment as to implicate the School District’s recognized authority to discipline speech which materially and substantially interferes with the requirements of appropriate discipline and collides with the rights of others” (Kowalski v. Berkeley County Schools, 2011).

Linking to Practice

Do:

Educate parents and students on the negative impact of bullying and cyberbullying.

Develop and enforce clear rules regarding student bullying and cyberbullying. Make policy clear that off-campus behavior that creates a material or substantial disruption on campus or creates a hostile environment may be subject to school-administered discipline.

Train faculty to recognize the signs of depression or other mental or physical problems associated with bullying.

Educate students on proper social networking and cyberetiquette.

Sexting

Although there is no legal definition, sexting generally refers to teens taking sexually explicit photos of themselves or others in their peer group and transmitting those photos by text messaging to their peers. It is generally understood that sexting does not include sexually explicit photos sent by minors to adults or photos sent as a result of blackmail or coercion (National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, 2009). Some surveys indicate that as many as 30% of teens 12 to 17 who own cell phones may have “sexted” by sending sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images of themselves to someone else via text messaging or have received a nude or nearly nude image on their phone (Lenhart, 2009). Sexting has caught many school leaders by surprise, and until recently few school districts had policies regarding it. Consequently, at least a few school districts have referred students to local prosecutors (Wastler, 2010).

Prosecutors have brought child pornography charges against participants. For example, Jorge Canal sent a sexually explicit picture to a female student he had known for more than a year. Canal was found guilty of disseminating obscene material to a minor under Florida state law. He was sentenced to 1 year of probation and notified that he would be forced to register as a sex offender (State v. Canal, Jr., 2009). Other prosecutors have opted for education. In 2008, school officials in Tukahannock (Pennsylvania) High School discovered saved images of nude or seminude teenage girls on several students’ confiscated cell phones. After threatening the students with child pornography charges, the prosecutor notified the parents of 20 students who appeared in or possessed the images that the students would be required to participate in a 6- to 9-month education program or face criminal charges. Several students and their parents, supported by the American Civil Liberties Union, appealed to the district court (Miller v. Skumanick, 2009). The district court granted a temporary restraining order prohibiting the prosecutor from initiating criminal charges against the students for two relatively innocuous photographs in question (Wastler, 2010). A unanimous Third Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court ruling (Miller v. Mitchell, 2010).

It is generally acknowledged that child pornography charges and registration as a sex offender may not be appropriate for teens sexting between peers. Since 2009, at least 10 states have enacted bills to address teen sexting (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2010). These laws for the most part define sexting as the electronic transmission or possession of sexually explicit images. Some states, such as Arizona, have classified possession or transmission of sexually explicit images as a class 2 misdemeanor. Other states, such as Illinois, have laws that prohibit the transmission of sexual images of another minor. Violators may be adjudicated as a minor in need of supervision and ordered to obtain counseling or community service (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2010).

In addition, sexting may be viewed as a form of cyberbullying and under certain circumstances creates a hostile environment that has a negative impact on the educational opportunities of the victim. In these cases school leaders would seem to have an obligation to act to protect the victim from further harassment and take steps to eliminate the hostile environment.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Educate parents and students about the dangers of sexting. Once pictures are viral, the sender no longer has control over who sees the images, how they are used, or how they are posted in social networking sites.

Develop a simple process for students, parents, and others to report incidents of sexting regardless of where the images originate.

Train faculty to recognize the symptoms associated with peer harassment.

Do Not:

Hesitate to contact parents when incidents of sexting become known.

Dating Violence

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008) defines dating violence as violence that occurs between two people in a close relationship. Dating violence may include physical violence (pinching, hitting, shoving, or kicking), emotional violence (threatening a partner or harming his or her sense of self-worth), and sexual violence (forcing a partner to engage in a sex act when he or she does not or cannot consent). Dating violence is relatively prevalent and affects the mental health of the victim (CDC, 2008). Studies indicate that at a minimum 10% of high school students are victims of dating violence in one form or another. Among female students who date in high school, some data indicate that as many as 30% are victims of dating violence. The data also indicate that victims of dating violence have an increased risk of drug and/or alcohol use, suicide ideation or attempt, and risky sexual behavior (CDC, 2008). In short, dating violence affects the mental and physical health of the victims and is thus a serious school safety issue (Carlson, 2003).

Several states require school districts to educate students on the issue of dating violence. For example, Georgia law requires the state board of education to develop a rape prevention and personal safety education program, and a program for preventing teen dating violence for grades 8 to 12 (S. B.). Texas state law requires each school district to adopt and implement a dating violence policy to be included in the district improvement plan (37.0831 Texas Education Code). The policy must include a definition of dating violence and address safety planning, enforcement of protective orders, training for teachers and administrators, counseling for affected students, and awareness education for students and parents. Except for states that require some form of education concerning the problem, dating violence at high school campuses has been largely ignored (Carlson, 2003). Regardless of the reasons why dating violence has traditionally not been addressed by school districts, Carlson (2003) proposes that dating violence can be viewed as identical to sexual harassment. The only difference is that dating violence occurs between dating partners, whereas sexual harassment is unwanted or unwelcome behavior of a sexual nature regardless of whether the perpetrator and victim are dating. The effects of off-campus dating violence often carry over to the school environment. For example, if a student alleges that she was sexually assaulted, forced to have sex, or physically abused by her boyfriend and is being taunted and harassed by other students or her boyfriend, the school should take into account the off-campus conduct when evaluating whether there is a hostile environment on campus (Dear Colleague, 2011, April 4). Naturally, in cases of alleged sexual assault or coerced sex school districts have an obligation to involve law enforcement as well.

In addition, dating violence can be a form of bullying, and a student could potentially claim that the school or school district was deliberately indifferent to the dating victimization. If some or all of the emotional abuse from a dating partner is conducted electronically by text messaging, social networking, and so forth, a student could claim deliberate indifference to cyberbullying on the part of schools or school districts. Carlson (2003) makes the following recommendations:

Middle schools and high schools need to educate all students about dating violence. The education should include the signs of an unhealthy relationship.

Train staff and faculty to recognize, prevent, and stop dating violence. Staff and faculty should follow the same curriculum as students including learning about the dynamics of dating violence and identifying the signs and symptoms of teen abuse.

School districts should develop policies and procedures for handling student complaints about dating violence. Most school districts already have such policies and practices in place for handling sexual harassment complaints. Adding dating violence to this process makes intuitive sense.

Schools should educate parents about dating violence.

Security Cameras

In 2007, 66% of students ages 12 to 18 reported the use of one or more security cameras to monitor school (Robers et al., 2010). Security cameras and recording devices may not be a panacea, but they are very good at deterring outsiders from coming on campus. They also deter students from committing infractions and can be invaluable to school administrators and law enforcement when dealing with alleged violations of school rules or criminal codes (Stader, 2011). According to Brady (2008), the U.S. Supreme Court has developed two legal tests that provide guidance in analyzing the legality of emerging surveillance technology. In Katz v. United States (1967), the Court held that recordings may be unconstitutional when a person has an expectation of privacy that society is prepared to recognize as reasonable. The second case, Kyllo v. United States (2001), involved the use of thermal imaging technology. The Court held that when surveillance technology is not in general public use, the surveillance is a search and a warrant is required.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that video surveillance is permissible in areas where an expectation of privacy is minimal, such as hallways, parking lots, or playgrounds. However, video surveillance is not permissible in areas where a reasonable person would have an expectation of privacy. For example, a jury recently awarded $40,000 each to 32 students who were taped by security cameras in a Cookeville, Tennessee, middle school locker room (“Students filmed in locker room win case,” 2007). In 2002, the Overton County School Board had approved the installation of video surveillance equipment throughout the middle school building. The cameras transmitted images to a computer terminal in the assistant principal’s office. The images were also accessible via remote Internet connection, and they were accessed 98 times through Internet service providers. The Sixth Circuit Court upheld the jury award, stating, “Some personal liberties are so fundamental to human dignity as to need no specific explication in our Constitution…. Surreptitiously videotaping [the girls] in various states of undress is plainly among them” (Brannum v. Overton County School Board, 2008).

According to the National Forum on Educational Statistics (NFES) (2006), videotapes or photographs directly related to a specific student created and maintained by the school district are educational records and are subject to FERPA. For example, consider a situation in which a student engages in a fight in a school hallway and the video of the fight is used as evidence to discipline the student. The video would be included in the involved student’s education record, and the school would need to obtain consent before publishing or disclosing the contents of the video to unauthorized individuals. However, at least according the NFES, other non-involved students in the video would be considered “set dressing” (not relevant to the incident) and not covered by FERPA.

One controversial use of security cameras is in classrooms. However, the use of video cameras in the classroom as part of teacher appraisal has been upheld by at least one court. For example, a Texas state court upheld a school board decision to terminate the employment of a teacher based in part on video evidence (Roberts v. Houston Independent School District, 1990). The court held that a public school classroom is not a zone where a teacher has a right to privacy. More recently, a California state court upheld the use of a video camera in an office shared by three employees because one of the employees was suspected of unauthorized use of the computer after school hours (Crist v. Alpine Union School District, 2005).

Internet Statutory Protections

Parental concerns over protecting children, especially young children, from the potential dangers of the unfettered Internet have not been lost on the political agenda setters of both major political parties. This concern has led to several federal legislative efforts. Among these efforts are the Child Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), and most recently the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA).

Child Online Privacy Protection Act

The Child Online Privacy Protection Act (15 USCS 6501, 1998) requires the Federal Trade Commission to enforce rules regarding children’s online privacy. COPPA applies to the online collection of personal information of children under 13. Personal information includes such information as full name, home address, e-mail address, telephone number, or any other information such as hobbies that would allow someone to identify or contact the child. The act also applies to information collected via cookies or other types of tracking mechanisms that are tied to individually identifiable information (Federal Trade Commission, www.ftc.gov). The Federal Trade Commission considers any website that includes subject matter, models, language, or advertising marketing to children to be accountable to this act. Websites must contain plain language prominently displayed outlining the types of information collected, parental rights, and how the operator uses the personal information. Release or sharing information to a third party requires parental signature (Conn, 2002).

Children’s Internet Protection Act

The Children’s Internet Protection Act (2001) requires schools and libraries to enforce a policy of Internet safety that includes the use of filtering or blocking technology in order to qualify for E-rate discounts. CIPA (20 USCS) requires that schools develop and enforce an “Internet safety policy” that protects against Internet access to visual depictions that are obscene, constitute child pornography, or are harmful to minors. Local communities are responsible for determining what constitutes prohibited materials and appropriate school actions under CIPA. At a minimum, however, the district must provide reasonable public notice and hold at least one public hearing that addresses school Internet safety policies and practices.

The American Library Association and others challenged the constitutionality of CIPA. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, based on First Amendment claims, found the act unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed. Although unable to agree on a rationale for their decision, among the various opinions the Court held that the act does not impose an undue burden on libraries; Internet access in libraries is not a “traditional” or a “designated” public forum; concerns of “overblocking” could be easily resolved; libraries traditionally had censored pornographic literature by choosing not to purchase such material; and the act is a legitimate exercise of congressional spending power. In addition, Justices Kennedy and Breyer expressed the view that CIPA serves a legitimate government interest in protecting young users from material inappropriate to minors (United States v. American Library Association, 2003).

Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment

The Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment applies to programs that receive federal funding. PPRA is intended to protect the rights of parents and students by ensuring that schools and contractors make available for inspection by parents any instructional materials used in connection with a survey, analysis, or evaluation funded by the U.S. Department of Education and ensuring that schools and contractors obtain written parental consent before minor students are required to participate in any such survey that reveals information such as political affiliations, mental or psychological problems, sex behavior and attitudes, or illegal, antisocial, or other self-incriminating behaviors. For all practical purposes, filtering software with all its imperfections is the only technology available to meet this requirement (Conn, 2002).

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (20 USCS 1232g) covers the release of student records to third parties. Release of such data for students under 18 is not permissible without parental permission. FERPA applies to identifiable student personal, academic, and disciplinary records. It requires that parental permission be sought whenever student information, especially photographs or other likenesses, are published on the school website.

Linking to Practice

Do:

Schedule yearly public meetings to explain campus or district Internet filtering software. Explain how the software works, the kinds of sites blocked by the software, and punishments for bypassing the software.

Consider making lists of age-appropriate websites for student use. Share this information with teachers, students, parents, and community members.

Consider restricting student research for term papers, essays, and so on to “approved” search engines such as ERIC.

Publicize student privacy rights, including directory information, in a wide range of formats including teacher handbooks, as part of acceptable use policies, newsletters to parents, and on the school website. Regardless of this dissemination, it is probably good policy to obtain affirmative parental permission before posting any student data on school websites.

Do Not:

Refuse parents or other community members access to information regarding the types of sites students and teachers are accessing.

Summary

School safety has evolved into one of the most important tasks associated with campus and district leadership. Security, especially security of expectation, is a prerequisite for learning. Security is not possible without equity. Security and equity are the foundations for meeting ISLLC Standard 3. Security and equity come in many forms, including policies and practices to keep weapons out of school. Security of expectation also includes policy and practices that address teacher-on-student and student-on-student victimization. Student victimization includes sexual harassment, bullying, dating violence, and sexting. Once knowledge of safety or victimization issues are know, the ISLLC standards and federal and state law place an affirmative duty on school leaders to effectively respond to eliminate the victimization.

ISLLC Standard 3

Connecting Standards to Practice

The Lady in Red

Without preamble, Riverboat High School principal Tara Hills said, “Sharon, I may have a Homecoming problem.” Assistant Superintendent Sharon Grey was well aware of the tradition and importance of Homecoming to the Riverboat School District and community. Homecoming consisted of a week full of spirit days, hall decorating, float building, bonfires, pep assemblies, the Friday afternoon parade, the all-important Homecoming game, and the equally important Homecoming dance. Parents and alumni played a large role in the festivities. By tradition, the Homecoming dance capped the weeklong activities, and large numbers of community members came to watch the final dances, view the Homecoming attire, and witness the all-important crowning of the Homecoming Queen.

It was also tradition at RHS to allow students to invite outside guests to the Homecoming dance, provided that the guest was properly registered in the office before the dance. Such was the case on the first day students were allowed to register outside dates as Andrew Wade, a 18-year-old senior, signed up his date, Lindsay Lewis, a 19-year-old freshman at the local community college. Andrew was notably excited and did not hesitate to show Lindsay’s picture to everyone who would take the time to look. Andrew cornered Tara in the office, Lindsay’s picture in hand. “This is the dress she is wearing to the dance. We simply shopped for hours, but finally found this wonderful red one. Isn’t she simply gorgeous?”

Reaching across the desk, Tara handed Lindsay’s picture to Sharon. Lindsay definitely made an impression. Tall and svelte, she posed on a stool wearing a radiant smile, her long brown hair flowing over a very short electric red dress that revealed several inches of muscular leg. “That’s some dress, all right,” was all Sharon could muster. “Does this meet the Homecoming dress code requirements?”

Smiling, Tara replied “You changed that policy, remember?”

“Oh yeah, right. Maybe not one of my smarter ideas. So, what’s the problem?”

“Well, I don’t know how to say this: Andrew’s date is transsexed. I have already heard from several parents who are concerned about this situation. I just sent two boys to assistant principal Tommy Thompson for pushing Andrew in the hallway. Andrew told me they were calling him names. As you know, this community is very traditional, and I don’t think this is going to go over very well.”

Sharon returned to her office. Some telephone messages waited on the desk. She scanned them. Several were typical calls, but a few caught her eye: The superintendent wanted to speak to her about the Homecoming dance, the chairman of the local ministerial alliance would appreciate an explanation of how outside Homecoming dates were screened, and Andrew Wade’s father wished to speak to Sharon regarding the assault on his son that morning.

Question

Argue for or against allowing Andrew Wade to attend the Homecoming dance with Lindsay as his date. What legal protections, if any, does Andrew Wade have? Cite ISLLC standards, case law, Dear Colleague letters from OCR, and ethical principles to support your answer. Write a memorandum to the superintendent or school board president outlining your view.