Program Outcome 4 Please respond to the following discussion topic and submit to the discussion forum as a single post. Your initial post should be a minimum of 150 words in length. Then, make at leas

CHAPTER 4

Leadership and the Manager

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

• Address the role of the manager as a principal agent of change.

• Differentiate among the terms power, influence, and authority.

• Recognize the importance of authority for organizational stability.

• Identify the sources of power, influence, and authority.

• Relate the sources of power, influence, and authority to the organizational position of the line manager.

• Recognize the limits placed on the use of power and authority in organizational settings.

• Recognize the importance of delegation of authority.

• Explore the nature of leadership and the reasons why individuals seek leadership positions.

• Identify the styles of leadership, their characteristics, and the circumstances under which they are applied.

CHANGE AND THE MANAGER

The healthcare setting of today is a highly dynamic environment in which the individual manager must embrace the reality of constant change and accept and fulfill the role of change agent within the organization. It is only through addressing essential change and truly leading employees in its acceptance and implementation that the manager can be successful in the long term. Denying or resisting change does not merely mean standing still but losing ground and actually going backward relative to technology and society as they race ahead.

The department manager must be able to deal with employee resistance to change, including the most frequently encountered causes of resistance and how best to approach resistance to change with employees. However, this implies that the manager is already completely on board with the necessity for a particular change. It is now appropriate to acknowledge that the manager may well be fully as susceptible to resistance as the employees. Who is the manger but simply another employee? He or she can be just as affected by misgivings and uncertainty about impending change as the rank-and-file staff. A discussion of how managers may deal with change appears in Chapter 2.

Thus, the manager may have a difficult task up front in the implementation of change, especially change mandated “from on high” or forced by external circumstances, because the manager has nearly the same potential for resistance as the employees. Even the knowledge that a certain change is inevitable regardless of what it entails does not necessarily guarantee that the manager will be a willing advocate for the change.

Of course the manager, and just about everyone else for that matter, is likely to champion a change that was his or her own idea. But when ideas or directives or other requirements come from elsewhere, the manager, who may experience some feeling of resistance, must deliberately strive to overcome that feeling and become champion of the change. It is often extremely difficult for the manager who feels some personal misgivings to go forward as the driver of change.

We are told repeatedly that the manager can address change with the employees in three ways: tell them what to do, convince them of what must be done, or involve them in determining what must be done. This third approach, involving them, is all well and good—but often it cannot be used. The first approach, the tell-them-what-to-do route, is avoided if possible because it does little to temper resistance. This leaves the second approach, the need for the manager to convince the employees of what must be done. Clearly, many employees are more likely to get on board with a particular change if they know why it must be done. And an honest why is not simply telling the employees that it is “orders from administration” or blaming it on the ever-present yet never identifiable “they” as in “they are making me do it.”

The central point of this brief discussion is that if the manager is to be a true agent of change and an honest and effective catalyst for change, the first person to be accepting and supportive of change is the manager. So if you, the manager, experience doubts or misgivings about some change that lies ahead, work these out within yourself and with your superiors as necessary. Your employees should be able to see you as a true agent of change who is there to support their efforts in implementing change and helping them through it such that everyone, yourself included, achieves a new comfort zone as essential change becomes part of the norm.

WHY FOLLOW THE MANAGER?

The manager issues an order or directive, and the result is compliance. But why do employees obey? Is it even appropriate to use the term obey to describe this compliance? Which bases of authority are operative in superior–subordinate transactions? What are the limits of a manager’s authority? What if a particular supervisor is seen as a weak manager? Are there remedies available for addressing problems related to weak or ineffective management leadership? Of what value to the organization is the authority structure? What are the consequences for life within the organization if there is not general, unchallenged compliance most of the time? When actions of compliance are described, which term provides the proper point of reference—power, authority, or influence? Are these terms mutually exclusive or are they synonymous when used in the context of organizational relationships? These questions arise when discussion of authority in organizations is undertaken.

Organizational behavior is controlled behavior, behavior that is directed toward goal attainment. The authority structure is created to ensure adherence to organizational norms, to suppress spontaneous or random behavior, and to induce purposeful behavior consistent with the aims of the organization. No matter how the work within the organization is divided, no matter the extent to which specialization, departmentation, centralization, or decentralization is formalized, there must be some measure of legitimate authority if the organization is to be effective. The concept of formal authority is supported by the two related concepts of power and influence. These concepts may be separated for analytical purposes; in actual practice, however, the concepts of authority, power, and influence are intertwined.

THE CONCEPT OF POWER

Power is the ability to obtain compliance by means of some form of coercion, whether blatant or subtle; one’s own will prevail even in the face of resistance. Power is force or naked strength; it is a mental hold over another. Like authority and influence, power is aimed at encouraging compliance, but it does not seek consensus or agreement as a condition of that compliance.

Power is always relational. An individual who has power over another person can narrow that person’s range of choices and obtain compliance. The power holder does not necessarily force compliance by physical acts but rather may operate in more subtle ways, such as an implied threat to apply sanctions. Latent power is frequently as effective as an overt show of power. Power attaches to people, not to official positions. The formal authority holder (i.e., the person who has the official title, organizational position, and grant of authority) may or may not have power in addition to this formal grant of authority.

An imbalance in superior–subordinate relationships can occur when a nonofficeholder has more power than the official officeholder. This can even be seen in family life. For example, when a 2-year-old boy shows signs of an incipient temper tantrum in the middle of the annual family gathering, the power balance clearly is in favor of the child if the tantrum pattern has developed. The child does not have to carry out the explosive behavior; the mere threat of the possibility brings about some desired behavior from the parent caught in the situation.

Workers often have some degree of power over line supervisors and managers. A worker with specific technical knowledge can withhold key information from a manager or can develop a relationship that is personally favorable. Information may not actually be withheld; the mere possibility that the manager cannot rely on an individual is enough to shift the balance, at least temporarily, in favor of the worker. Groups of workers can control a manager when it is known that the manager is responsible for meeting a deadline or filling a quota; the manager’s ability to do so is dependent on the cooperation of the workers. Normal, steady output may be produced routinely, but the ability to make that extra push needed to surpass the quota or reach a special level of output rests more with the workers than with the manager. Strikes by workers are classic examples of mobilized power, but the power shifts back in favor of management if striking workers are terminated during a strike.

When an individual can supply something that a person values and cannot obtain elsewhere in an accepted manner, or when the individual can deprive one of something valued, then there is a power relationship. This implicit or explicit power relationship may or may not be perceived by one or both parties.

THE CONCEPT OF INFLUENCE

Like power, influence is the capacity to produce effects on others or obtain compliance from others, but it differs from power in the manner in which compliance is evoked. Power is coercive, but influence is accepted voluntarily. Influence is the capacity to obtain compliance without relying on formal actions, rules, or force. In relationships governed by influence, not only compliance but also consensus and agreement are sought; persuasion rather than latent or overt force is the major factor in influence. Influence supplements power, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish latent power from influence in a given situation. Does the individual comply because of a relationship of influence or because of the latent power factor? Together, power and influence supplement formal authority.

THE CONCEPT OF FORMAL AUTHORITY

Authority may be described as legitimate power. It is the right to issue orders, to direct action, and to command or exact compliance. It is the right given to a manager to employ resources, make commitments, and exercise control. By a grant of formal authority, the manager is entitled, empowered, and authorized to act; thus, the manager incurs a responsibility to act. Authority may be expressed by direct command or instruction or, more commonly, by request or suggestion. Through the delegation of authority, coordination is established in the organization.

The authority mandate is delineated, communicated, and reinforced in several ways, including organizational charts, job descriptions, procedure manuals, and work rules. Although the exercise of authority in many situations tends to be similar to transactions of influence, authority differs from influence in that authority is clearly vested in the formal chain of command. Individuals are given specific grants of authority as a result of organizational position. Power and influence may be exercised by an individual authority holder, but they may also be exercised by individuals who do not have specific grants of authority.

Authority is both complemented and supplemented by power on the one hand and influence on the other hand. It is within the realm of formal authority to exact compliance by the threat of firing a person for failure to comply; however, this may be such a rare occurrence in an organization that such a threat is really an application of power more than an exercise of authority. However, formal aspects of authority may be so well developed that the major transactions remain at the level of influence, with the influence based largely on the holding of formal office. The infrequent use of formal authoritative directives to evoke compliance may indicate organizational health; that is, people know what to do and perform willingly.

THE IMPORTANCE OF AUTHORITY

When a subordinate refuses to accept the orders of a superior, the superior has several choices, each of which carries potentially negative consequences for the attainment of organizational goals. The superior can accept the insubordination, withdraw the order, and call on others to carry out the directive. This action would probably further weaken authority, however, because the superior would most likely be perceived as lacking the subtle blend of power and authority needed to exact compliance on a predictable basis. A chain reaction of insubordination could occur. If other workers are asked to carry out a directive that had been refused by one worker, resentment could build up and produce negative consequences. If the order is withdrawn completely, of course, the work will not be accomplished.

The manager who decides to enforce compliance may suspend or fire the insubordinate worker, but the superior still must find a worker to carry out the directive. If there is a chain reaction of insubordination, it may become impractical to suspend or fire the entire work force. In such circumstances, the situation moves from one of authority to one of power. Therefore, managers must identify and widen their bases of authority to help ensure a stable work climate.

SOURCES OF POWER, INFLUENCE, AND AUTHORITY

The manager’s organizational relationships flow along the continuum of power, influence, and authority, varying in emphasis at different times and in different situations. To more fully understand the dynamics of the power–influence–authority triad, it is useful to examine the sources or bases of authority in formal organizations. The wider the base of authority, the stronger the manager’s position; with a broad base of authority, the manager can work in the realm of influence and need not rely only on the formal grant of authority that attaches to organizational position.

The sources of formal authority have been studied by several theorists in the disciplines of social psychology, management, and political science. A review of the literature suggests several sources or bases of authority: (1) acceptance or consent, (2) patterns of formal organization, (3) cultural expectations, (4) technical competence and expertise, and (5) characteristics of authority holders. The limits or weaknesses of each theory are offset by the approach taken in another.

The Consent Theory of Authority

The belief that authority involves a subordinate’s acceptance of a superior’s decision is the basis for the acceptance or consent theory of formal authority. A superior has authority only insofar as the subordinate accepts it. This theory implies that members of the organization have a choice concerning compliance, even when often they do not. It remains important to recognize the concepts of acceptance and consent to identify the centers of more subtle and diffuse resistance to authority, even when there is no overt and massive insubordination.

The zone of indifference and the zone of acceptance are two similar concepts in the acceptance or consent theory of authority. Chester Barnard used the term zone of indifference to describe that area in which an individual accepts an order without conscious questioning.1 Barnard noted that the manager establishes an overall setting by means of preliminary education, prior persuasive efforts, and known inducements for compliance. The order then lies within the range that is more or less anticipated by the subordinate, who accepts it without conscious questioning or resistance because it is consistent with the overall organizational framework. Herbert Simon used the term zone of acceptance to reflect the same authority relationship. The zone of acceptance, according to Simon, is an area established by subordinates within which they are willing to accept the decisions made for them by their superior.2 Simon noted that this zone is modified by positive and negative sanctions in the authority relationship, as well as by such factors as community of purpose, habit, and leadership.

Coupled with the foregoing factors is the concept of the rule of anticipated reactions, which Simon included in his discussion of the zone of acceptance.3 According to this rule, subordinates seek to act in a manner that is acceptable to their superior, even when there has been no explicit command. The authority system, including anticipated review of actions, is so well developed that the superior needs only to review actions rather than issue commands. The past organizational history in which positive and negative sanctions were enforced is recalled; the expectation of the review of actions is fostered so that the subordinates’ zone of acceptance is expanded.

Another approach to the concept of authority as a relationship between organizational leaders and their followers is described by Robert Presthus, who posited a transactional view of authority in which there is reciprocity among individuals at different levels in the hierarchy.4 Compliance with authority is in some way rewarding to the individual, and the individual, therefore, plays an active role in defining and accepting authority. Everyone has formal authority, in that each person has a formal role in the organization. There is, Presthus stated, an implicit bargaining and exchange of authority, with each individual deferring to the other.

The notion of reciprocal expectations in authority relationships is further supported in Edgar Schein’s discussion of the psychological contract.5 As in Barnard’s concept of the zone of indifference and in Simon’s rule of anticipated reactions, the premise of member acceptance of organizational authority and its attendant control system is basic to the psychological contract. The workers’ acceptance of authority constitutes a realm of upward influence; in turn, the workers expect the authority holders to honor the implicit restrictions on their grant of authority. The workers expect the authority holders to refrain from ordering actions that are inconsistent with the general climate of the given organization and from taking advantage of the workers’ acceptance of authority. The workers also expect as part of this psychological contract the rewards of compliance (i.e., positive sanctions readily given and negative sanctions kept at a minimum).

The Theory of Formal Organizational Authority

In his classic study of bureaucracies, Max Weber discussed three forms of authority: charismatic, traditional, and rational–legal. Charisma, as defined by Weber, is a “certain quality of an individual personality by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional qualities.”6 The social, religious, and political groups that form around charismatic leaders tend to lack formal role structure. The routines of bureaucratic structure are not developed and may even be disdained by the group. Charismatic authority figures function as revolutionary forces against established systems of leadership and authority. Such authority is not bound by explicit rules but rather remains invested in the key charismatic individual. Personal devotion to the leader or what might be termed an almost irrational faith in the leader bind the members of the group to one another and to the leader.

Because charismatic authority is linked to the individual leader, the organization’s survival is similarly linked. If the organization is to endure, it must take on some of the characteristics of formal organizations, including a formalized authority pattern. In this area, two developments are possible. Charismatic leadership may evolve into a traditional system of authority, or it may develop into the rational–legal system of formal authority. In traditionalism, a pattern of succession is developed. A successor may be designated by the leader or hereditary/kinship succession may be established; then a system of transferring the leadership to the legitimately designated individual or heir must be developed. This, in turn, leads to a system of roles and formal authority. Weber uses the term routinization of charisma to describe this transformation of charismatic authority into, first, traditional authority, and then rational–legal authority.

Rational–legal authority is the authority predicated in formal organizations. It is generally assumed that formal organizations come into being and derive legitimacy from an overall social and legal system. Individuals accept authority within the formal organizational structure because the rights and duties of members of the organization are consistent with the more abstract rules that individuals in the larger society accept as legitimate and rational.

Within the formal organization, a system of roles and authority relationships is carefully constructed to enable the organization to survive and move toward its formal goal on a continuing, stable basis. Authority has its basis in the organizational position, not in any individual. Weber described in detail the major characteristics of bureaucratic structures; the following characteristics relate to the rational-legal authority structure:7

1. The principle of fixed and official jurisdictional areas means that areas are generally ordered by rules—that is, by laws or administrative regulations.

a. The regular activities required for the purposes of the bureaucratically governed structure are distributed in a fixed way as official duties.

b. The authority to give the commands required for the discharge of these duties is distributed in a stable way and is strictly delimited in a fixed way as official duties.

c. Methodical provision is made for the regular and continuous fulfillment of these duties and for the execution of the corresponding rights; only persons who have generally regulated qualifications to serve are employed.

2. The principles of office hierarchy and of levels of graded authority mean that there is a firmly ordered system of superiority and subordination in which supervision of the lower offices is carried out by the higher ones.

The theory of formal organizational authority rests on this rational–legal system of formal office, impersonality of the officeholder, and a system of rules and regulations to constrain the grant of authority. Delegation of formal authority from top management to each successive level of management is the basis of formal organizational authority. Authority is derived from official position and is circumscribed by the limits imposed by the hierarchical order.

Cultural Expectations

Both the consent theory of authority and the theory of formal organizational authority include an implicit assumption that individuals in a society are culturally induced to accept authority. Furthermore, the acceptable use of authority in organizations is defined in part by the larger societal mores as well as by union contract, corporate law, and state and federal law and regulation.

Acceptance of the status system in a society is learned as part of the general socialization process. General deference to authority is ingrained early in psychosocial development, and social roles with their sanctions are accepted and reinforced throughout life. The role of employee carries with it both formal and informal sanctions; insubordination is not generally condoned. Even as a group cheers the occasional rebel, there is attendant discomfort because something is out of order in the relationship. When the insubordination of an individual begins to threaten the economic security of the group, there is counterpressure on that individual to bring about reacceptance of authority. Fear of authority may bring about a similar response of renewed acceptance of authority and counterpressure on any dissidents.

The expected zone of acceptance or zone of indifference varies with different social roles. These variables are rarely spelled out in great detail; they are learned as much through the pervasive cultural formation process as through the formal orientation process in any one organization. There is a kind of “group mind” that includes the general realization that a particular behavior pattern is part of a given role, and the entire role set reinforces this general acceptance of authority.

Technical Competence and Expertise

Three terms reflect the organizational authority that is derived from or based on the technical competence and expertise of the individual, regardless of which office or position the individual holds in the organization. These terms are functional authority, law of the situation, and authority of facts.

Functional authority is the limited right that line or staff members (or departments) may exercise over specified activities for which they are responsible. Functional authority is given to the line or staff member as an exception to the principle of unity of command. For purposes of this discussion on the sources of authority, it is useful to emphasize the special character of functional authority, which is given to a line or staff member primarily because that individual has specialized knowledge and technical competence. For example, the human resources manager normally assists all other department heads in matters of employee relations, although this manager has no authority to intervene directly in manager–employee relations. The situation changes when there is a legally binding collective bargaining agreement: the human resources manager, with special training in labor relations, may be given functional authority over all matters stemming from the union contract because of specialized knowledge. Another example is that of information technology support staff who, because of technical competence, are given authority to make final decisions over certain aspects of data collection. The authority is granted because of the technical competence of the staff members.

Mary Parker Follett, a pioneer in management thought, introduced the terms law of the situation and authority of facts.8 Follett described the ideal authority relationship as that stemming from the situation as a whole. Each participant in the organization who is assumed to have the necessary qualifications for the position held has authority associated with that position. Orders become depersonalized in that each participant in the process studies and accepts the factors in the situation as a whole. Follett stated that one person should not give orders to another person but rather both should agree to take their orders from the situation.9 She developed this concept further: both the employer and the employee should study the situation and should apply their specialized knowledge and technical competence through the principles of scientific management. The emphasis shifts, in Follett’s approach, from authority derived from one’s official position or office to authority derived from the situation. The individual who has the most knowledge and competence to make the decision and issue the order in a particular situation has the authority to do so. The staff assistant or a key employee potentially has as much authority in a particular situation as does the holder of a hierarchical office. The incident command system used in hospital disaster management is an example of law of the situation, with command passing from unit manager, clinical specialist, or safety officer as the circumstance requires.

Closely tied to the concept of law of the situation is that of authority of facts. Follett stressed that, in modern organizations, individuals exercise authority and leadership because of their expert knowledge.10 Again, leadership and authority shift from the hierarchical position to the situation. The person with the knowledge demanded by the situation tends to exercise effective authority.

Both of these concepts place emphasis on the depersonalization of orders. At the same time, the source of the authority is highly personal, in that knowledge and competence for the exercise of authority belong to an individual. Underlying the concepts of functional authority, law of the situation, and authority of facts is the theme that authority is derived from the technical competence and knowledge of individuals in the organization who do not necessarily hold formal office in the line hierarchy.

Characteristics of Authority Holders

Authority rests in individuals. The talents and traits of the individual may become the source of authority, as in the case of the charismatic leader. A person holding power may use this as a base for gaining legitimate authority, or a group may invest the person of power with legitimate authority as a protective measure and seek to impose the limits and customs of authority. They may also accept the power holder as formal officeholder as a means of accepting the situation without further conflict. Technical competence and knowledge are also personal characteristics that become the basis of authority in certain situations.

Authority by Default

A weak form of authority stems from situations in which the group members, either by conscious decision or by lack of attention to authority–leadership succession, do not develop strong, clear, authority patterns. A professional organization, for example, might decide to rotate authority–leadership roles through a nomination process that limits the choice of candidates from specific geographic regions. In another organization, the committee chair role might be simply rotated through all the members in turn, either because members do not wish to have any one department as dominant or simply because the task is seen as a chore. In another organization, provision for succession might be weakened because the same few members hold officer positions for years, so no new leadership is developed.

Of course, the time invariably comes when a long-term authority holder is no longer able to continue. A vacuum then arises, and a newer member is prevailed on to assume the office. When such occurs, authority by default is the rule. The officeholder must attend to building up the office or accept the realities of the situation, as he or she has only a limited authority mandate.

The Manager’s Use of Sources of Authority

In practice, managers should recognize all the potential sources of authority and weigh the contribution of each theory to obtain as complete a picture of the authority nexus as possible. They should assess their own grants of authority and try to determine which elements tend to strengthen their authority and which tend to erode it.

The base of authority shifts from time to time. As an example, suppose an individual is offered the position of department head of a health information service because of that individual’s competence in the administration of health information systems; this specialized knowledge and technical competence is the first pillar of authority. When the individual accepts the position, the formal authority mandate of that official position is added. This authority, in turn, is shaped by the prevailing organizational climate, which includes either a wide or narrow zone of acceptance on the part of employees. The personal traits of the authority holder complete the authority base for that office.

The individual with a participative management style may emphasize those aspects of authority that widen the zone of acceptance. The setting itself may dictate the predominant authority base, as in the law of the situation; in a highly technical setting, those persons with the most technical knowledge use this knowledge as the base of authority. Although there is a tendency to downplay internal politics in organizations such as healthcare institutions, some individual managers may use power as a major source of authority. Astute managers regularly assess the several bases of authority available to them to enhance the authority relationships and thereby contribute more effectively to the achievement of organizational goals.

RESTRICTIONS ON THE USE OF AUTHORITY

Several factors restrict the use of authority. Some constraints stem from internal factors, such as the limits placed on authority at each organizational level; others stem from external factors, such as laws, regulations, and ethical considerations. The following is a systematic summary of these factors:

1. Organizational position. Each holder of authority receives a limited delegation of authority consistent with the position held in the organization. An individual has no legitimate formal authority beyond that accorded to the organizational position.

2. Legal and contractual mandates. Authority is limited by federal, state, and municipal laws and regulations relating to safety, work hours, licensure, and scope of practice; by internal corporate charter and bylaws; and by union contract.

3. Social limitations. The social codes, mores, and values of society at large include both implicit and explicit limits on the behavior of individuals. Authority holders are expected to act in a manner consistent with the predominant value system of the society. These social limitations are major factors in shaping the zone of acceptance and the general cultural deference of individuals who are members of organizations.

4. Physical limits. An authority holder can neither force a person to do something that is simply beyond that person’s physical capabilities nor escape the natural limits of the physical environment, such as climate or physical laws.

5. Technological constraints. The advances and the limitations of the state of the art must be considered in the exercise of authority; no amount of power or authority can bring about a result that is beyond the technical ability of the individuals.

6. Economic constraints. The scarcity of needed resources limits the behavior of formal authority holders.

7. Zone of acceptance of organization members. Both authority and power have their limits in that the net cost of using either must be calculated. When a weak manager is faced with a strong employee group, perhaps as encountered in a strong union setting, the cost of using even legitimate authority may be too high; the authority grant is actually diminished.

Although many employees do not have complete freedom to choose what they will or will not do, they may resist authority in subtle ways, such as adherence to job duties exactly as stated in the job description, passive resistance, and failure to take initiative in any area not specifically designated by the supervisor. The manager must move into a distinct leadership position to develop a wide zone of acceptance, as leadership becomes an essential adjunct to the exercise of authority.

IMPORTANCE OF DELEGATION

Although the manager retains overall responsibility and authority for the work of the department or service, he or she must necessarily delegate authority to specific workers under his or her jurisdiction. Simply put, it is not possible for the manager to carry out every task. Therefore, each worker receives delegated authority from the manager to proceed on a day-to-day basis. Empowerment of the workers is essential.

Managers set up the parameters for action through several means: the development of policies and procedures, the promulgation of work rules and codes of behavior, the development of job descriptions with job duties and expectations well delineated, and the presentations of formal orientation and training programs associated with job duties. The manager consciously selects an appropriate style of leadership and communication to further enhance an atmosphere in which workers accept responsibility for their part in meeting the organizational goals.

A manager who is new to the role may experience some uneasiness with delegating. First, there is simply that natural tendency to think, “I can do this better or faster myself.” Second, a manager may harbor some fears. For instance, if the worker fails at the task, the responsibility still rests with the manager; it is the manager who will take the heat, so to speak. There is also a certain loss of satisfaction and recognition; managers are often removed from day-to-day interaction with patients and their families and their own professional peers who remain in the arena of active, hands-on practice. Recognition of these inner barriers to delegation is the first step to overcoming resistance to this necessary aspect of authority.

“Dos” and “Don’ts” of Delegation

Know when to delegate. In most day-to-day circumstances, delegation of authority is the norm. Routine tasks such as employee scheduling, for example, are easily accomplished by the supervisor closest to the unit. Certain highly specialized tasks such as revenue-cycle/compliance reviews are best delegated to a member of the department team who specializes in the area. Such a person would have the most up-to-date knowledge related to the topic. Workflow coordination and routine problem solving between or among working units are best accomplished by the immediate unit supervisors who are in continual interaction. Delegation is also a part of team development; the manager builds capability and confidence in the assistant managers, unit supervisors, and specialists. Delegation is part of the intentional training and mentoring goals of the manager.

Know when not to delegate. Certain activities remain the primary responsibility of the manager and normally are not delegated, such as hiring, disciplinary action, and termination. Generally, any task that falls under the heading of personnel management cannot be delegated; no nonmanagement employee must ever be empowered to make personnel decisions that affect other nonmanagement employees. Throughout each process, there will be input from unit managers and supervisors, but the final action is that of the manager. Complex or volatile employee or client situations sometimes arise; these, too, are the manager’s responsibility. Overall systems and workflow, along with equipment and layout, are the manager’s concerns, although there is input from unit managers and supervisors.

Avoid common pitfalls associated with delegation. Two common pitfalls can occur inadvertently; the prudent manager takes care to avoid these. First, a manager might undermine a unit supervisor by countermanding, even informally, a decision made by the first-line supervisor. For example, a unit supervisor might deny a request for a schedule change by an employee because of workflow or staffing considerations. The employee might informally ask the manager to approve the desired schedule change. Managers who allow themselves to override a subordinate manager’s decisions undercut the authority and responsibility grant of this manager. (This is not the same thing as the normal grievance or appeal process during which an employee may meet with a higher-level manager at designated steps in the course of the seeking resolution.) Second, a manager, with the best of intentions, solicits information on a regular basis, perhaps daily, from unit managers. The casual but purposeful question, “How are things going in your unit today?” may lead to on-the-spot reports of one or another workflow or staffing problem. The concerned manager might readily respond, “I’ll look into that and get back to you,” instead of involving the subordinate supervisor in solving the problem.

Interact with workers regularly. It is necessary to set up a balanced system of availability and support. The manager remains available to unit supervisors through a mix of formal and informal interactions, such as the following:

• Formal, periodic meetings with individual supervisors for in-depth feedback about a specific activity. These meetings focus on workflow and related problem solving.

• Formal development meetings with individual supervisors or the team of supervisors. The focus is development of supervisory skills, mentoring, and career path development.

• Informal day-to-day “prn” interaction.

• A combination of formal and informal daily briefing, sometimes referred to as “the huddle.”

The final practice involves a brief daily meeting, about 15 minutes in length, held sometime between the early morning and midday. By this time, any immediate concerns will have surfaced, yet there is sufficient time remaining in the day to solve most problems that arise. The team usually remains standing while each supervisor summarizes the particular concerns in his or her functional unit, allowing each member of the team to become aware of workflow impact, employee issues, and “news of the day.” Team members are able to make immediate plans to deal with intradepartmental concerns without the manager’s having to mediate such coordination. An administrative assistant also attends, bringing materials for distribution on the spot, which eliminates the accumulation of materials in the inbox for each team member. The manager comments on such materials if follow-up is required. The assistant’s presence also facilitates actions that keep things moving without further instruction—for example, he or she will follow up on a purchase order or check on a question relating to a payroll matter.

The manager typically rotates the location of “the huddle” among the different units of the department unless confidential information is involved. In the latter case, the unit supervisor of that department leads a roundtable briefing. This action provides visibility of the authority–responsibility mandate entrusted to that supervisor. The employees of the unit see their unit supervisor as a member of the team. Furthermore, this experience of leading a roundtable briefing provides additional training in leadership for each team member. “The huddle” takes place daily, even when the manager is unable to attend, thereby reinforcing the role set of the supervisors as designated agents of the manager. This practice empowers the unit supervisors by enabling them to take the lead.

Effects of Good Delegation

Recognition of the benefits of proper delegation and, conversely, awareness of the consequences of poor delegation further enhance a manager’s ability to delegate. Just as proper delegation increases the zone of acceptance on the part of employees, so failure to delegate demoralizes workers, thereby shrinking their field of cooperation. Morale suffers, turnover rates increase, and loss of productivity results. When workers in regular contact with clients cannot easily take immediate and effective action, client groups become alienated and unhappy and seek services elsewhere. The organization develops a reputation for being wrapped in bureaucratic red tape.

Finally, without proper delegation, a manager must remain constantly present to authorize action; this is time consuming and wasteful of managerial resources. It is also unrealistic because a manager’s duties frequently require being out of the department or office and even away from the premises. With a manager’s commitment to delegation in place, and with, the day-to-day activities flow toward accomplishing the overall mission of the organization.

LEADERSHIP

Frequently, when professionals describe a leader as a powerful person who has made it to the top of his or her field, they use the expression “industry leader” or other similar label. The successful health professional does not seem to share familiar and common habits with the average practitioner. People imagine the person as a romantic figure who is not human. Drucker describes leadership in reality as “mundane, unromantic and boring. Its essence is performance.”11 Yet leadership is vital for the future growth and development of health professions. This section is designed to address the leadership qualities that everyone has buried within. Rather than define leadership as distant and unusual, this section describes it as a set of characteristics that emerge from individuals who are able to get things done within an organization.

“Natural leaders” do exist, but it is likely that they are few and far between. For the most part leaders are not born; they develop. In fact, leaders are not extraordinary in any way except that they can match organizational goals to the abilities and interests of their work groups. This talent is mercurial; some leaders are effective in one set of circumstances but not in others. Leadership is not based on impossible characteristics possessed by few; rather, it is a collection of abilities that successful managers have carefully cultivated.

Definition of Leadership

A leader is a person who can organize tasks and make things happen through the efforts of a group of people. Using the unique interests and needs of every member of the work group, the effective leader inspires goal-directed behavior that is consistent and efficient. The leader cajoles, rewards, punishes, organizes, stimulates, strengthens, communicates, and motivates. There is no set standard for leadership behavior, as individuals must match their own characteristics to the needs of the organization.

The personal characteristics common to many leaders are a strong self-image, a vision of the future, a firm belief in the goals of the organization, the ability to influence the behavior of subordinates, and the ability to relate to and influence individuals in parallel or superior positions of authority.

Leadership exists both informally and formally. Informal leadership is exerted in many settings, including formal organizations. Within any formal organization, there are subunits and even para-organizations, such as collective bargaining units, that are led by individuals who do not hold formal hierarchical office. Leadership is implied, even explicitly included, in the role of the manager whose function is to achieve organizational objectives by coordinating, motivating, and directing the work group. For the remainder of this discussion on formal leadership, it is presumed that the manager is a leader in addition to being a holder of formal authority.

Where Do “Leaders” Come From?

The word “leaders” in this subheading stands in quotes because not all persons in leadership positions are truly leaders.

In organizational life, leaders are “acquired” in two ways: they are promoted from the ranks of employees, and they are recruited from outside of the organization. Both means have their advantages and disadvantages. The leader promoted from within ordinarily knows the organization and its structure and workings, understands the policies and practices of the organization, knows about the processes he or she will oversee, and is familiar with the staff. But the leader promoted from within usually has drawbacks to overcome in the form of interpersonal relationships that can hamper the transition into a leadership role, especially, as frequently occurs, when one is promoted to managing a department in which he or she was one of the employees.

The leader recruited from outside usually comes in with no knowledge of the personalities already in place. Depending on conditions existing before the new leader’s arrival, this person may be cautiously welcomed by the staff as one who can improve certain conditions or may be regarded with apprehension as a potential “new broom” who will make changes. So whether a new “leader”—whether first-line manager, middle manager, or whatever—rises from within or comes from outside, there are pluses and minuses associated with the appointment.

Anyone who has been part of a work organization for any length of time has learned that the best rank-and-file employees, those who are most knowledgeable and successful, do not necessarily make the best leaders. Yet there is a certain amount of logic in the promotion of the technically best employees into management. After all, promoting weak or even mediocre workers into management is surely not a consideration. But many leadership positions are filled by individuals who have had little or no education in the management of people. This is a large area of concern in many organizations, and it is often addressed through management development programs.

But rather than further consideration of where leaders come from, it is important to consider a related question that says a great deal about many individuals who enter leadership. Why do many individuals seek leadership positions?

What Drives People to Become Leaders?

There is an informal exercise that is worth conducting with a group of employees, especially with people in a supervisory development program who wish to become supervisors or have already been promoted to supervision. Lead them in a brainstorming exercise using this instruction; list any or all reasons a given individual might have for seeking a leadership position. Do not let the participants note just a few of the supposedly standard reasons, and do not be concerned with similarities and overlaps among reasons. Without too much prodding, a group of 10 or more people can come up with literally dozens of reasons why individuals seek leadership positions. Then have the group sort these reasons into two broad categories: (1) those addressing the true needs of leadership and (2) those addressing primarily an individual’s needs or desires.

It does not take too long to discover that the reasons addressing an individual’s needs or desires far outweigh the reasons that address the needs of the organization or entity that requires leadership. On the “up” side will be to make a difference, to serve the customer, to implement my ideas, to improve the organization, to motivate and encourage employees, to solve some long-standing problems, and a number of other similarly noble statements. On the “down” side, always the much longer list coming from this exercise, will be to make more money, to obtain better benefits, to acquire standing as a manager, to acquire power, to exert influence, to position myself to grow further, and other essentially selfish reasons. If asked, of course, one who is seeking a leadership position will never articulate any of the selfish reasons but will surely state a couple of the organization-positive reasons.

Consider the public arena in which we obtain leaders by voting for them. Candidates will tell us what they stand for and what they propose to do if elected (or, in these times of rampant negative campaigning, will regale us with reasons why their opponents are unfit to hold office). A candidate for public office will always articulate some variation on I only want to serve. But consider this question: would this individual still “want to serve” if doing so did not entail acquiring money, benefits, position, power, prestige, influence, acclaim, and such?

Thus, people seek leadership positions for both positive and negative reasons, and many of these reasons are driven by selfishness. It is possible that many of the best potential leaders are buried in the general population; these are people who have or could develop the requisite skills but experience none of the selfish urges or who simply do not want the responsibility of what they may see as a thankless job. Once in a while, in the face of an emergent situation when others have failed or become incapacitated, one of these potential leaders will step into the breach and take charge, but this does not often happen. However, seldom do these best potential leaders step forward and seek leadership positions.

Leadership Qualities

To influence and induce others to strive toward a goal, the leader must possess not only a strong vision of that goal but also the ability to render the goal meaningful to the group. The knowledge, insight, and skill of the leader are greater than those of other members of the group. At an obvious level, the leader leads but does not drag, coerce, or push the group. Group members are steadily induced to move toward the goal; they are influenced in a pervasive way so that the overall goal becomes their own goal. The leader does not achieve the work alone but instead successfully coordinates the work of the group. The leader inspires confidence through both emotional and knowledge ties with the followers. Indeed, a major factor that characterizes a truly successful leader is the willing acceptance of that leadership by the followers.

It is possible to generate a fairly lengthy list of qualities and characteristics that some would say “define” a leader. However, there are a couple of problems related to the creation of such a list. One difficulty, surely minor in the long run, is that no one person’s list is ever complete in the eyes of another person, and it approaches the impossible to get even a few people to agree on which qualities and characteristics are more important than the others. But the greater difficulty with any list of “essential qualities and characteristics of a leader” is that no matter what quality or characteristic is cited as “essential,” we can nevertheless point to some supposedly very successful “leaders” who are lacking in such. Many successful leaders are lacking, for example, in honesty, compassion, analytical ability, and numerous other qualities. So any attempt to define a leader by listing qualities and characteristics simply takes us back to the single characteristic that always holds true: the acceptance of the followers. One who is not accorded the acceptance of the followers does not truly lead but rather pushes.

Leadership Functions

In formal organizations, the leader has certain functions that are tied to the organizational need for leadership. The leader is expected to influence, persuade, and in general control the group. As an individual with vision, the leader is expected to take calculated risks and to act as a catalyst in the change process.

The leader carries out important functions on behalf of group members through the role of representative. For example, employees look to their unit or department head to speak for them and to seek or to obtain advantages for them. The leader may be cast in several roles by followers, especially at the symbolic level, and may even be seen as the father or mother figure who shields the individual from difficulties. The leader may also be the scapegoat. As the management representative closest to the rank-and-file worker, the first-line leader–manager bears the brunt of anger when the organizational situation is less than optimal.

The leader is presumed to embody the values of the group. As such, the leader becomes the focal point in the motivational process. He or she fosters the development of the climate and conditions that favor individual involvement in group effort. Leadership is a process more than a structure; the leader fosters the climate for change so that the organization will possess the adaptability required for long-term survival.

From Theory to Practice: A Leader’s Plan of Action

The manager must make a conscious commitment to the exercise of leadership through specific actions. Leadership activity clusters in natural groupings and to a considerable extent are intertwined. Here are some examples of leadership action relating to health information management:

1. The leader starts and sustains the conversation. By being out in front of the trends, the leader studies the big challenges, “digests them,” “talks them up,” and translates them into action plans within the organization. Examples include encouraging employee development through the attainment of additional specialty credentials and promoting participation in regional health information exchange and e-health initiatives.

2. The leader uses professional and technical competence to promote the health information professionals as the authoritative sources for clinical documentation systems and practices. Activities would typically include monitoring the federal initiatives concerning the electronic health record (EHR) initiative, the dissemination of information about the current changes in electronic discovery civil rule and the related topic of the definition of the electronic legal record, and serving as EHR project manager or team member.

3. The leader partners with key players in the organization. The leader identifies individuals whose support is critical to successful implementation of major systems—for example, the EHR, speech recognition technology, or computerized provider order entry. The leader takes the initiative in interdepartmental collaborative action such as:

○ Policy and procedure affecting joint action

○ Clinical pertinence review protocols

○ In-service training needs

○ Compliance reviews and billing audits

○ Risk management reviews

○ Interorganization peer review

4. The leader is actively engaged in the life of the organization. The leader recognizes and accepts that necessary work extends beyond the routine 9-to-5 day and beyond the borders of the department. The leader’s attitude is one of loyalty to and enthusiasm for the work of the organization. This visible support of the mission might take on a variety of forms:

○ Participation in organizational events to honor employees or volunteers—for example, employee recognition ceremonies and receptions

○ Participation in outreach activities such as career days, health fairs, and fund-raising events

○ Attendance at events sponsored by other departments—for example, the open house celebrating a designated professional week (such as Physical Therapy Week or National Nurses Week)

○ Participation in the organization’s speakers bureau

○ Hosting regional meetings of one’s profession to bring attention to the organization’s areas of excellence

5. The leader passes on the praise and the pride. Employees are not taken for granted; rather, their accomplishments are noted within the department and the organization. The leader takes care to nominate employees for appropriate awards such as “Employee of the Month.” Departmental activities are included in the internal newsletter, with its customary “spotlight on” column. The leader submits entries for trade and professional association newsletters featuring the department. The leader finds opportunities for employees to participate in extradepartmental events, such as annual disaster or emergency preparedness drills, thereby raising the visibility and involvement of the group.

Styles of Leadership

The manner in which a manager interacts with subordinates reflects a collection of characteristics that constitute a style of leadership. Although any manager may use several styles of leadership—choosing the style most appropriate for a given situation—one style generally emerges as that manager’s predominant mode of interaction.

Autocratic Leadership

Also referred to as authoritarian, boss-centered, or dictatorial leadership, autocratic leadership is characterized by close supervision. The manager who uses this style gives direct, clear, and precise directions to employees, telling them what is to be done and how it will be done; there is no room for employee initiative. Employees do not participate in the decision-making process. There is a high degree of centralization and a narrow span of management. The chain of command is clearly and fully understood by all. Autocratic managers use their authority as the principal, or only, method of getting work done because they believe that employees could not properly or efficiently carry out work assignments without detailed instruction.

There are two general types of autocratic leadership, exploitative and benevolent. In the exploitative type, the followers are literally exploited for the benefit of the leader. In the benevolent type, the “father-knows-best” approach to leadership is used; the leader treats followers kindly while sincerely believing he or she must make all the decisions and call all the shots. Both the exploitative autocrat, fortunately a seldom-encountered sort of leader, and the benevolent autocrat, a much more common sort than the other, are dictators; they lay down the law and the followers have no choice other than to comply or leave.

Although autocratic leadership appears to get results much of the time, it can be fatal in the long run. Employees can lose interest in their assignments and stop thinking for themselves, because there is no room for independent thought. Under certain conditions and with specific employees, however, a degree of close supervision may be necessary. Some employees prefer to receive clear and precise orders, because close supervision reassures them they are doing a good job. Even so, it can generally be assumed that an autocratic, close leadership style is the least effective and least desirable method for motivating employees to perform. This remains so whether the leader is the harsh exploitative autocrat or the kindly benevolent autocrat; in either case, the leader dictates and the followers are expected to comply.

Bureaucratic Leadership

Like the autocratic leader, the bureaucratic leader tells employees what to do and how to do it. The basis for this leadership style is almost exclusively the organization’s rules and regulations. For the bureaucrat, the rules are the law. The bureaucratic manager is often afraid to take chances and manages “by the book.” Rules are strictly enforced, and no departures or exceptions are permitted. The bureaucrat, like the autocrat, allows employees little or no freedom. Some bureaucrats become so entrenched in their reliance on rules and regulations that they are essentially paralyzed when encountering a situation for which there is no applicable rule or regulation.

Participative Leadership

In participative leadership, the contribution of the group to the organizational effort is emphasized. This style is the opposite of autocratic, close supervision. The manager who uses the participative method involves the employees in the decision-making process and in the maintenance of cohesive group interaction. The manager involves employees in determining goals, objectives, and work assignments, and similarly he or she involves them in defining the nature and extent of a problem before making a final decision and issuing directives or orders. This approach endeavors to make full use of the talents and abilities of the group members. If approached honestly and with fair consideration of employees’ input, the employees who have participated in the process are likely to experience a sense of ownership in the resulting decision.

Participative management does not weaken a manager’s formal authority, because the manager remains responsible for the final decision whether it is made independently or by the group. The obvious advantage of the participative style of leadership revolves around the meaningful involvement of the employees, which greatly enhances the implementation of the decisions that have been made.

Consultative Leadership

Some managers use a pseudo-participative method of leadership to give employees the feeling that they have participated in decision making. The consultative leader routinely solicits employee input, then just as routinely ignores that input and independently makes the decision. This sort of leader is often self-deluded into believing that he or she is being openly participative by soliciting employee input. However, when the employee input is ignored, employees quickly sense that the manager is manipulating people and that their participation in the decision-making process is not real.

Laissez-Faire Leadership

Laissez-faire or “free rein” or essentially “hands-off” leadership is based on the assumption that individuals are self-motivated and generally self-directed. In this approach, employees receive little or no supervision. Employees, as individuals or as a group, determine their own goals and make their own decisions. The manager, whose contribution is minimal, acts primarily as a consultant and does so only when asked. The manager does not lead but allows the employees to lead themselves. Some managers consider this approach to be true democratic leadership, but the usual end result is disorganization and chaos. The lack of leadership permits different employees to proceed in different directions.

Paternalistic Leadership

This is quite similar to benevolent autocracy, the “father-knows-best” approach to leadership. The paternalistic manager treats employees like children, telling them in a kindly manner what to do and how to do it. It is the paternalistic manager’s belief that employees do not really know what is good for them or how to make decisions for themselves. In this approach, everyone is watched over by the benevolent manager—the benign dictator—and the employees eventually become extremely dependent on their “paternalistic boss.” The paternalistic leader genuinely believes that the followers are incapable and must therefore be told every move to make. In contrast, the benevolent autocrat does not care whether the followers are capable or not, but firmly believes that he or she must think and decide for the entire group.

Continuum of Leadership Styles

Another way to view leadership behavior is on a continuum ranging from highly boss-centered to highly group-centered. The relationship between the manager and the employee in the continuum ranges from completely autocratic, in which there is no employee participation in the decision-making process, to completely democratic, in which the employee participates in all phases of the decision-making process. The following briefly describes the gradations along the continuum:

1. The manager makes the decision and announces it. The manager identifies a problem, considers alternative solutions, selects a course of action, and tells employees what to do. Employees do not participate in the decision-making process; they do not provide input in any form.

2. The manager “sells” the decision. The manager again makes the decision without consulting the employees. Instead of simply dictating the decision, however, the manager attempts to persuade the employees to accept it largely through explaining how the decision serves both the goals of the department and the interests of group members.

3. The manager presents ideas and invites questions. The manager has already made the decision but asks the employees to express their ideas. Thus, the manager allows for the possibility that the initial decision may be modified.

4. The manager presents a tentative decision subject to change. The manager allows the employees the opportunity to exert some influence before the decision is finalized. The manager meets with the employees and presents the problem and a tentative decision. Before the decision is finalized, the manager obtains the reactions of employees who will be affected by it.

5. The manager presents the problem, obtains suggestions, and makes the decision. Up to this point on the continuum, the manager has always come before the employees with at least a tentative solution to the problem. At this point, however, the employees get the first opportunity to suggest solutions. Consultation with the employees increases the number of possible solutions to the problem. The manager then selects the solution that he or she regards as most appropriate in solving the problem.

6. The manager defines limits and asks the group to make the decision. For the first time, the employees make the decision. The manager now becomes a member of the group. Before doing so, however, the manager defines the problem and the limits and boundaries within which the decision must be made.

7. The manager permits subordinates to function within the limits defined by the superior. For the maximum degree of employee participation, the manager defines the problem and lists the guidelines and boundaries within which a solution must be achieved. The limitations imposed on the employees come directly from the manager, who participates as a group member in the decision-making process and is committed in advance to implementing whatever decision the employees make.

In summary, the manager’s relationship with the employees influences morale, job satisfaction, and work output. Employee satisfaction is positively associated with the degree to which employees are permitted to participate in the decision-making process. In contrast, poor supervision causes employee dissatisfaction, high turnover rates, and low morale.

Factors That Influence Leadership Style

No one style of leadership fits all situations. A successful manager is one who has learned how to apply the most appropriate method for a given situation. Before selecting a style of leadership or deciding to blend several styles, the manager must consider a number of factors:

1. Work assignment. If the work assignment is repetitious, properly trained employees do not need constant or close supervision. If the assignment is new or complex, however, close supervision may be required.

2. Personality and ability of employees. Employees who are not self-starters function best under close supervision. Others, by reason of personality and work background, can take on new and important responsibilities on their own; these individuals react best to participative leadership. The occupational makeup of a department may also influence the leadership style used by the manager. For professional practitioners (e.g., physical therapists, occupational therapists, health information personnel) or other highly skilled employees, the employee-centered participative leadership style is often most effective. When employees are unskilled or unable to act independently, the boss-centered or autocratic style of leadership may produce better results.

3. Attitude of employees toward the manager. The manager cannot begin to lead or influence behavior unless he or she is accepted by the group. Employees fully accept the manager’s authority only when they believe that the goals and objectives of the manager are consistent with their own personal and professional interests.

4. Personality and ability of the manager. The manager’s personality has a definite effect on the behavior and performance of employees. The manager must treat employees’ opinions and suggestions with respect and must sincerely encourage employee participation.

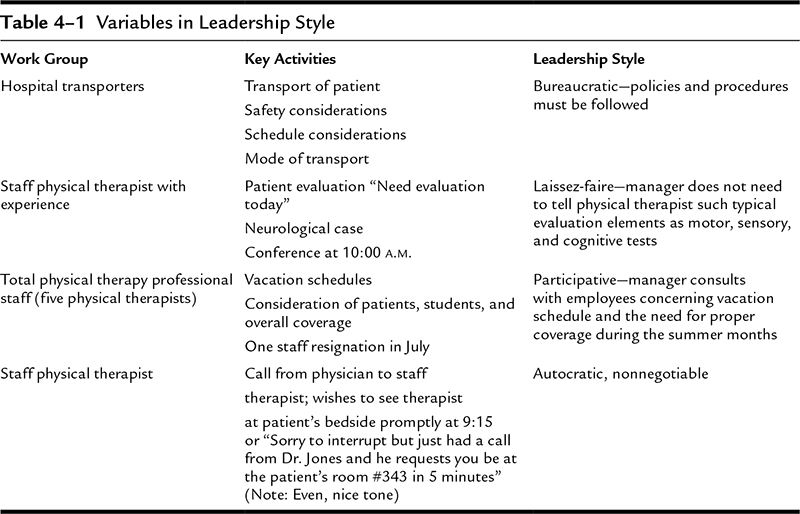

When faced with different work group encounters and situational factors, the effective manager shifts from one style of leadership to another, often without conscious recognition of a shift in style. Table 4–1 shows examples of the adjustments in leadership style that a manager makes to stimulate maximum effort from employees.

Communicating Your Own Managerial Style

A manager may deliberately go out of his or her way to communicate to employees the style of leadership or management he or she practices. It is not particularly uncommon for a manager who is relatively new to an organization or department to make statements such as these: “I believe in employee participation, and I always welcome your input”; “I practice management by wandering around, so you’ll see me a lot in the departments”; or, one of the most oft-heard, “my door is always open.”

There are some significant hazards in introducing yourself as a manager in such a manner. In the words of a wise, anonymous observer of management practices, “It’s Management 101—using the buzzwords, saying what you think you should be saying, telling people that you’re what the ‘management experts’ say you should be.” The hazards inherent in such pronouncements are found in the risk of being trapped by employee perception.

It takes only a few perceived contradictions of your self-described style to create dissonance. As soon as you are seen unilaterally making decisions without soliciting participation or input, you have created a perceived conflict between your words and your actions. And when a few employees have found you unavailable, although you have said “My door is always open,” more such conflicts are created and employee perceptions begin to turn unfavorably against you, whether deservedly or not. Any given perception may not be entirely accurate, but to the perceiver perception is reality.

It is best to say as little as necessary about your own style of leadership and allow your actions to convey your true style. In other words, instead of telling employees what kind of leader you are, let your actions show them. You may not come across as the sort of leader idealized in “Management 101,” but, even more importantly, you are more likely to come across as honest.

Situational Leadership and Adjustment

What is here referred to as “situational leadership” is hardly worth of a label in its own right. For the well-experienced conscientious manager and insightful leader of people, it should be automatic. Situational leadership consists of adapting one’s style to the particular situation at hand or to the unique needs of the moment.

Not every problem submits to the same logical process of analysis and solution. Not every need that arises in the workday can be addressed in an identical manner. And, most important to the manager, not every employee is able to respond as desired to the same management approach. Within the same group you may have “Theory X” individuals, who must be led and who indeed often prefer to be led and have others do their thinking for them, along with “Theory Y” people who are self-motivated and capable of significant self-direction. This is especially likely in department employing both professionals and nonprofessionals. Although the same overall “rules”—that is, the same personnel policies—apply uniformly to all employees, the manager will have to deal differently with individuals in other ways. Some you may consult and invite their participation or input; others you will simply direct.

Avoid making assumptions about people; never assume that what works with one will work with all others. Know your employees and try to understand each one as both a producer and a person. By working with people over a period of time, and especially by working at the business of getting to know them, you can learn a great deal about individual likes and dislikes and capabilities. Learn about your people as individuals and when necessary lead accordingly. If you are convinced that a certain employee genuinely prefers orders and instructions and this attitude is not inconsistent with job requirements, then use orders and instructions. Although many employees of healthcare organizations seem to prefer participative leadership, not everyone will desire this same consideration. Maintain sufficient flexibility to accommodate the employee who wants or requires authoritarian supervision. It is fully as unfair to expect people to become what they do not want to be as it is to allow a rigid structure to stifle those other employees who feel they have something more to contribute.

There is no single style of leadership that is appropriate to all people and situations at all times. Let the situation and the needs of those involved dictate your managerial style.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS ABOUT AUTHENTIC PERSONAL LEADERSHIP

In the preceding discussion, the manager has been identified as an agent of change. The functions of the manager have been noted, and leadership traits and foundations have been explored. All of this leads up to some final thoughts about the manager–leader as a person.

One who would aspire to leadership and become successful in its pursuit must perform some serious self-examination by asking: why should anyone be led by me? This can be a startling question. A person’s initial reaction might be one of defensiveness or even irritation: “Shouldn’t it be obvious? I am up-to-date in my field; I come in every year at or under budget; no accreditation citations arise from my department; there are few, if any, grievances from my staff; and my employee turnover is minimal. What more do they want?”

Now ask the latter question another way: “What more do you want? What kind of person are you striving to be?” Some people view the idea of self-development as trendy: dress for success, or six steps to persuading and negotiating, or similar topics suggesting artificial methods for getting ahead in the organization. Such practices even become the fodder for sit-coms and cartoons, not to be taken seriously. But for others, this focus on self is embarrassing and perhaps discouraging. Who can be the perfect person?

Such reactions could cause us to neglect this important aspect of leadership. Notice the emphasis that major business and management schools place on the cultural, spiritual, and psychological development of the manager–leader. They devote significant curriculum time and resources to these topics. Major business and management journals include regular features on these aspects of leadership. When we observe successful peers, higher-level managers, and leaders both within the organization and external to it, we notice some common traits. Specifically, they possess a set of value-added characteristics.

Value-Added Characteristics

The value-added characteristics flow from a deep respect for the dignity of the human person. This genuinely high regard for oneself and for others is reflected in the presentation of self in everyday life. It is manifested through an attitude of engaged, conscious living; gracious interpersonal relationships; and calm, orderly work habits. It is embodied in the values of integrity, trustworthiness, and respect.

Engaged, Conscious Living

Individuals who display the characteristic of engaged, conscious living have an awareness of and an enthusiasm for life. They bring positive energy to the work setting that is rooted in a balanced life—they like their life! Their approach to life keeps them from overreacting. They are not the caricature characters who are always having a bad day and give off the negative vibration: “don’t even ask; you don’t want to know; wait until I have had my coffee.” No, these are the people who are steady; they are pleasant to associate with; they easily and routinely show graciousness.

Gracious Interpersonal Relationships