For each chapter ofOB,you should read the entire chapter and take notes (which you will likely use on the respective assignment, as well as in your Final Exam studying and other course work).Once you

| CHAPTER 10: INDUSTRIALIZATION AND IMPERIALISM, Growth and Struggle, 1870s-1904 ContentsDocuments: 8 Document 1, Mark Twain explains his term, “the Gilded Age” in America (Mark Twain Project 1873) 8 Document 2, Frank Norris describes how the “Octopus” threatens California wheat farmers (www.archive.org 1901) 9 Document 3, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets depicts prostitution during the Gilded Age (about.com Classic Literature 1893) 12 Document 4, Carnegie and the “Gospel of Wealth” (Fordham University, 1889) 14 Document 5, The “Life Story of a Polish Sweatshop Girl” (Digital History, 1902) 16 Document 6, Jim Crow in the South (American Memory 1886) (Primary Source Nexus 1913) 21 Document 7, Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” discusses dangerous working conditions in the meatpacking industry (History Matters, 1904) 23 Document 8, Jacob Riis photograph, “It Costs a Dollar a Month to Sleep in These Sheds” (University of Virginia, 1902) 26 Document 9, Francis Walker proposes the “Restriction of Immigration” (The Atlantic, 1896) 26 Document 10, Cartoon illustrating politics in the Gilded Age (University of Texas 1870) 28 Document 11, The New York Times reports on the explosion of the Battleship Maine (www.spanamwar.com 1898) 29 Document 12, Teddy Roosevelt encourages “The Strenuous Life” (Theodore Roosevelt Association 1899) 30 Document 13, Mark Twain condemns American Imperialism (Library of Congress 1900) 34 Post-Reading Exercises 34 Works Cited 35 |

Introduction and Pre-Reading Questions: One of Reconstruction’s major goals was to get the country to a stable and even profitable economic place and politicians were quite successful in achieving this goal. During the last three decades of the 1800s, there was a major and sophisticated transformation in industry, the economy and the nation. This transformation was due to the abundance of raw materials the US had access to, new and rapid innovations in technology, new entrepreneurs who invested in technology and innovation, a growing working class, and an ever-larger market to sell goods at a tremendous profit to. Such inventions as the transatlantic telegraph, the telephone, electric power, and steel processing techniques helped revolutionize and industrialize the United States and led to numerous exciting new technologies and techniques. For example, many entrepreneurs invested in another burgeoning transportation-based industry: the railroads. The railroads were so important because railroads were the primary method of transportation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and railroads provided industry with a way to transport their goods to distant markets. Railroads also allowed for far-away raw materials to be sent to production centers. The men behind the railroads were very interested in expanding the network of railroads because they knew that pumping large amounts of money into the railroad system would pay dividends for them and their investors. As a result, between 1860 and 1900, over 163,000 miles of railroad track were laid. Now that number probably doesn’t mean anything to you, but to compare, in 1860 there was only 30,000 miles of railroad track laid in the United States. What this meant was that entrepreneurs and businessmen now had more access to materials and markets than ever before and these investors were able to get very rich because of lax laws regarding paying employees fair wages, monopolies, and charging farmers fair rates.

Seeing the vast profits railroad barons were accumulating, others quickly sought to jump on board and when railroads began accepting corporate investment, not only did investors abound, but also rapid construction began, while standardization in tracks and cars, cheaper shipping rates, and research into new methods for locomotive power became the norm.

Other industries saw this positive development and quickly followed the railroad’s example. Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie used the corporation concept to buy up coal mines, iron stores, ore ships and railroad interests, allowing him to control every step of the production of steel at his mega-corporation, US Steel. This allowed Carnegie to take out the middle-man/men and make a lot more money for himself and his investors. John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company similarly began doing much of the oil processing in-house to increase profits, and also began buying up smaller oil producers to create one of the first monopolies.

But with pro-monopoly theories and often cutthroat labor practices, many Americans viewed the growth of corporations and corporate power as a major problem. Farmers and workers, for example, criticized corporations as a threat to the fundamentals of republicanism, which held that anyone could pull themselves up by their bootstraps and be successful and be treated to fair competition. Middle-class critics pointed to the corruption that the new industrial titans seemed to produce in their own enterprises and in local, state, and national politics. Overall, critics feared that the development of monopolies was dangerous. They believed that monopolies allowed these large corporations to fix artificially high prices, hurt workers by cutting wages, and destroy opportunity by making it impossible for small businesses to survive.

With all of this criticism, corporate giants went on the defensive, hoping to better the view many had of corporations. Andrew Carnegie, for example, came out as the most prominent spokesperson for the theory of the Gospel of Wealth, which argued that the wealthy, yes, had great power, but that they also had a great social responsibility. Document 4 outlines this social theory—what is Carnegie’s main argument? What effect do you think his actions had on American society at this time?

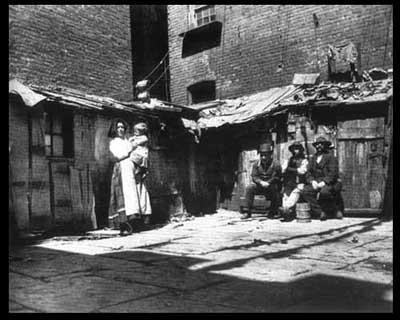

These corporate giants spurred massive industrial growth and enjoyed the wealth it created. But this growth and wealth also required a class of people who would produce the oil, the steel, and the automobiles—accordingly, America would see the creation of a distinct working class as the 18th century ended and the 19th century opened up. This creation of a working class contributed to dramatic changes in American labor—technological innovation had allowed for better production methods and cheaper products, but what do you think it meant for the worker? It meant that fewer workers were needed to produce mass products and it meant workers had fewer skilled jobs available to them. Documents 5 and 8 illustrate the life of an industrial worker in this time period. What was this life like? How did workers benefit from the system they were a part of? In what ways were they exploited?

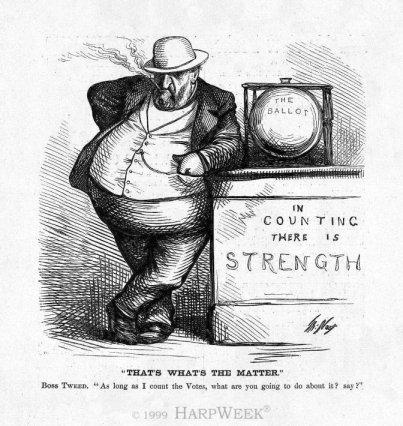

This period from 1877 to 1900 is often referred to as the “Gilded Age,” a reference author Mark Twain came up with to explain the excessive greed of capitalists and businesses during these early years of the Machine Age (Document 1). When the Gilded Age opened up in 1877, American politics were in dire straits. Much of the same greed and corruption that had made the Machine Age such a difficult world for the American worker had ruined the integrity of the American political system. Part of the problem was a lack of interest in politics. Most Americans at the time didn’t vote for important issues or push their representatives to take on pressing causes. Instead, most Americans voted based on cultural ties—for example, most Irish Catholics voted for the Democratic party, regardless of what the Democratic party stood for. And to make matters worse, the Democratic and Republican parties were both heavily corrupt at the start of the Gilded Age. Party Bosses and Political Machines ran the show—these guys would bribe Americans, particularly immigrants, to vote for their candidate in exchange for money or a job. This meant that party bosses could gain power in a pretty undemocratic way. It also meant that party bosses had free reign to appoint their buddies into other positions of power and further corrupt and undemocratize the political process. In particular, these corrupt politicians, when coupled with the already corrupt businessmen, ushered in some major problems – unfair railroad rates (which you’ll read about in Document 2), strong trusts which hurt small businesses, and, perhaps more importantly, a monetary policy—with a limited money supply and high tariffs—that many believed helped out big interests like the banks and hurt small interests like the farmers.

Alongside political problems, many Americans began to pay attention to the myriad social and moral problems taking shape in the United States. Out of concern over these major changes—the technological growth, poor living conditions, corruption, crime and so on—grew the Progressive movement. Journalists exposed problems like child labor, prostitution, racism, drunkenness, tenement housing and other social problems that they believed were direct results of the Machine Age and which they believed needed fixing. Documents 3, 6, 9 and 10 illustrate these problems. As you read these documents, do you think it’s surprising that these problems emerged out of population and industrial growth? Do you think the Progressive movement was a natural development to help correct some of these ills? As more and more Americans read about these problems, hundreds of thousands became involved in Progressive activity.

At the same time that all of these political, social and moral battles were being waged during the Gilded Age, the United States was also waging some major battles internationally. Activity in foreign policy really heated up during the Gilded Age, particularly as the concept of Imperialism began to dictate American international behavior. But where did Imperialism come from? Well, the American population was growing exponentially in the years following the Civil War and people were heading farther and farther west in search of available land and, more importantly, available resources. In the 1890s, the idea of “Manifest Destiny,” that idea that had carried settlers into the westernmost regions of the United States, led the U.S. to even begin spreading their territory to places outside of the continental U.S. Following the lead of European countries that had begun colonizing foreign territories in the nineteenth century, the United States began looking to colonize foreign countries, as well. They did this for three major reasons: new markets to export to; natural resources to exploit; and areas where overseas military bases could be built.

Imperialism took shape in many ways—first, America overthrew the Hawaiian government and made Hawaii an American territory so that sugar could be imported to the US more cheaply and so that a military base could be built on the Hawaiian islands . Next, in 1898, the United States engaged in a brief war with Spain over their colonial territories of Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico (Document 11).

But though the American government was pretty gung-ho about imperialism (Document 8) and about the countries they’d managed to extract from the Spanish Empire, a sentiment of anti-imperialism sprung up in the U.S., counting many influential members in its ranks, men like Mark Twain (Document 13), Andrew Carnegie, Samuel Gompers (the head of the biggest American labor union, the American Federation of Labor), and others. How was Imperialism in line with the idea of Manifest Destiny? What were the positive outcomes of Imperialism for the United States? What were some of the devastating effects of Imperialism? Why do you think the United States government continued to pursue an Imperialist policy for decades to come?

All in all, the Gilded Age was a period where Americans focused on untethered and unregulated growth—for better or for worse, and domestically and internationally. Though the results of this growth were often tremendous—tremendous wealth, tremendous production, tremendous international development—the results were often devastating for the people on the ground. This devastation ultimately led to the corrective measures of the Progressive Era.

Documents: Document 1, Mark Twain explains his term, “the Gilded Age” in America (Mark Twain Project 1873)1AUTHOR’S PREFACE TO THE LONDON EDITION.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In America nearly every man has his dream, his pet scheme, whereby he is to advance himself socially or pecuniarily. It is this all-pervading speculativeness which we have tried to illustrate in “The Gilded Age.” It is a characteristic which is both bad and good, for both the individual and the nation. Good, because it allows neither to stand still, but drives both for ever on, toward some point or other which is a-head, not behind nor at one side. Bad, because the chosen point is often badly chosen, and then the individual is wrecked; the aggregation of such cases affects the nation, and so is bad for the nation. Still, it is a trait which it is of course better for a people to have and sometimes suffer from than to be without.

We have also touched upon one sad feature, and it is one which we found little pleasure in handling. That is the shameful corruption which lately crept into our politics, and in a handful of years has spread until the pollution has affected some portion of every State and every Territory in the Union.

But I have a great strong faith in a noble future for my country. A vast majority of the people are straightforward and honest; and this late state of things is stirring them to action. If it would only keep on stirring them until it became the habit of their lives to attend to the politics of the country personally, and put only their very best men into positions of trust and authority! That day will come.

Our improvement has already begun. Mr. Tweed (whom Great Britain furnished to us), after laughing at our laws and courts for a good while, has at last been sentenced to thirteen years’ imprisonment, with hard labour.1 It is simply bliss to think of it. It will be at least two years before any governor will dare to pardon him out, too. A great New York judge, who continued a vile, a shameless career, season after season, defying the legislature and sneering at the newspapers, was brought low at last, stripped of his dignities, and by public sentence debarred from ever again holding any office of honour or profit in the State.2 Another such judge (furnished to us by Great Britain) had the grace to break his heart and die in the palace built with his robberies when he saw the same blow preparing for his own head and sure to fall upon it.3

MARK TWAIN.

The Langham Hotel,

London, Dec. 11th, 1873.

Document 2, Frank Norris describes how the “Octopus” threatens California wheat farmers (www.archive.org 1901)2As Harran came up, Presley reached down into the pouches of the

sun-bleached shooting coat he wore and drew out and handed him

the packet of letters and papers.

"Here's the mail. I think I shall go on."

"But dinner is ready," said Harran; "we are just sitting down."

Presley shook his head. "No, I'm in a hurry. Perhaps I shall

have something to eat at Guadalajara. I shall be gone all day."

He delayed a few moments longer, tightening a loose nut on his

forward wheel, while Harran, recognising his father's handwriting

on one of the envelopes, slit it open and cast his eye rapidly

over its pages.

"The Governor is coming home," he exclaimed, "to-morrow morning

on the early train; wants me to meet him with the team at

Guadalajara; AND," he cried between his clenched teeth, as he

continued to read, "we've lost the case."

"What case? Oh, in the matter of rates?"

Harran nodded, his eyes flashing, his face growing suddenly

scarlet.

"Ulsteen gave his decision yesterday," he continued, reading from

his father's letter. "He holds, Ulsteen does, that 'grain rates

as low as the new figure would amount to confiscation of

property, and that, on such a basis, the railroad could not be

operated at a legitimate profit. As he is powerless to legislate

in the matter, he can only put the rates back at what they

originally were before the commissioners made the cut, and it is

so ordered.' That's our friend S. Behrman again," added Harran,

grinding his teeth. "He was up in the city the whole of the time

the new schedule was being drawn, and he and Ulsteen and the

Railroad Commission were as thick as thieves. He has been up

there all this last week, too, doing the railroad's dirty work,

and backing Ulsteen up. 'Legitimate profit, legitimate profit,'"

he broke out. "Can we raise wheat at a legitimate profit with a

tariff of four dollars a ton for moving it two hundred miles to

tide-water, with wheat at eighty-seven cents? Why not hold us up

with a gun in our faces, and say, 'hands up,' and be done with

it?"

He dug his boot-heel into the ground and turned away to the house

abruptly, cursing beneath his breath.

"By the way," Presley called after him, "Hooven wants to see you.

He asked me about this idea of the Governor's of getting along

without the tenants this year. Hooven wants to stay to tend the

ditch and look after the stock. I told him to see you."

Harran, his mind full of other things, nodded to say he

understood. Presley only waited till he had disappeared indoors,

so that he might not seem too indifferent to his trouble; then,

remounting, struck at once into a brisk pace, and, turning out

from the carriage gate, held on swiftly down the Lower Road,

going in the direction of Guadalajara. These matters, these

eternal fierce bickerings between the farmers of the San Joaquin

and the Pacific and Southwestern Railroad irritated him and

wearied him. He cared for none of these things. They did not

belong to his world. In the picture of that huge romantic West

that he saw in his imagination, these dissensions made the one

note of harsh colour that refused to enter into the great scheme

of harmony. It was material, sordid, deadly commonplace. But,

however he strove to shut his eyes to it or his ears to it, the

thing persisted and persisted. The romance seemed complete up to

that point. There it broke, there it failed, there it became

realism, grim, unlovely, unyielding. To be true--and it was the

first article of his creed to be unflinchingly true--he could not

ignore it. All the noble poetry of the ranch--the valley--seemed

in his mind to be marred and disfigured by the presence of

certain immovable facts. Just what he wanted, Presley hardly

knew. On one hand, it was his ambition to portray life as he saw

it--directly, frankly, and through no medium of personality or

temperament. But, on the other hand, as well, he wished to see

everything through a rose-coloured mist--a mist that dulled all

harsh outlines, all crude and violent colours. He told himself

that, as a part of the people, he loved the people and

sympathised with their hopes and fears, and joys and griefs; and

yet Hooven, grimy and perspiring, with his perpetual grievance

and his contracted horizon, only revolted him. He had set

himself the task of giving true, absolutely true, poetical

expression to the life of the ranch, and yet, again and again, he

brought up against the railroad, that stubborn iron barrier

against which his romance shattered itself to froth and

disintegrated, flying spume. His heart went out to the people,

and his groping hand met that of a slovenly little Dutchman, whom

it was impossible to consider seriously. He searched for the

True Romance, and, in the end, found grain rates and unjust

freight tariffs.

Document 3, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets depicts prostitution during the Gilded Age (about.com Classic Literature 1893)3In a hall of irregular shape sat Pete and Maggie drinking beer. A submissive orchestra dictated to by a spectacled man with frowsy hair and a dress suit, industriously followed the bobs of his head and the waves of his baton. A ballad singer, in a dress of flaming scarlet, sang in the inevitable voice of brass. When she vanished, men seated at the tables near the front applauded loudly, pounding the polished wood with their beer glasses. She returned attired in less gown, and sang again. She received another enthusiastic encore. She reappeared in still less gown and danced. The deafening rumble of glasses and clapping of hands that followed her exit indicated an overwhelming desire to have her come on for the fourth time, but the curiosity of the audience was not gratified.

Maggie was pale. From her eyes had been plucked all look of self-reliance. She leaned with a dependent air toward her companion. She was timid, as if fearing his anger or displeasure. She seemed to beseech tenderness of him.

Pete's air of distinguished valor had grown upon him until it threatened stupendous dimensions. He was infinitely gracious to the girl. It was apparent to her that his condescension was a marvel.

He could appear to strut even while sitting still and he showed that he was a lion of lordly characteristics by the air with which he spat.

With Maggie gazing at him wonderingly, he took pride in commanding the waiters who were, however, indifferent or deaf.

"Hi, you, git a russle on yehs! What deh hell yehs lookin' at? Two more beehs, d'yeh hear?"

He leaned back and critically regarded the person of a girl with a straw-colored wig who upon the stage was flinging her heels in somewhat awkward imitation of a well-known danseuse.

At times Maggie told Pete long confidential tales of her former home life, dwelling upon the escapades of the other members of the family and the difficulties she had to combat in order to obtain a degree of comfort. He responded in tones of philanthropy. He pressed her arm with an air of reassuring proprietorship.

"Dey was damn jays," he said, denouncing the mother and brother.

The sound of the music which, by the efforts of the frowsy- headed leader, drifted to her ears through the smoke-filled atmosphere, made the girl dream. She thought of her former Rum Alley environment and turned to regard Pete's strong protecting fists. She thought of the collar and cuff manufactory and the eternal moan of the proprietor: "What een hell do you sink I pie fife dolla a week for? Play? No, py damn." She contemplated Pete's man-subduing eyes and noted that wealth and prosperity was indicated by his clothes. She imagined a future, rose-tinted, because of its distance from all that she previously had experienced.

As to the present she perceived only vague reasons to be miserable. Her life was Pete's and she considered him worthy of the charge. She would be disturbed by no particular apprehensions, so long as Pete adored her as he now said he did. She did not feel like a bad woman. To her knowledge she had never seen any better.

At times men at other tables regarded the girl furtively. Pete, aware of it, nodded at her and grinned. He felt proud.

"Mag, yer a bloomin' good-looker," he remarked, studying her face through the haze. The men made Maggie fear, but she blushed at Pete's words as it became apparent to her that she was the apple of his eye.

Grey-headed men, wonderfully pathetic in their dissipation, stared at her through clouds. Smooth-cheeked boys, some of them with faces of stone and mouths of sin, not nearly so pathetic as the grey heads, tried to find the girl's eyes in the smoke wreaths. Maggie considered she was not what they thought her. She confined her glances to Pete and the stage.

The orchestra played negro melodies and a versatile drummer pounded, whacked, clattered and scratched on a dozen machines to make noise.

Those glances of the men, shot at Maggie from under half-closed lids, made her tremble. She thought them all to be worse men than Pete.

"Come, let's go," she said.

As they went out Maggie perceived two women seated at a table with some men. They were painted and their cheeks had lost their roundness. As she passed them the girl, with a shrinking movement, drew back her skirts.

Document 4, Carnegie and the “Gospel of Wealth” (Fordham University, 1889)4The problem of our age is the administration of wealth, so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship. The conditions of human life have not only been changed, but revolutionized, within the past few hundred years. In former days there was little difference between the dwelling, dress, food, and environment of the chief and those of his retainers. . . . The contrast between the palace of the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer with us today measures the change which has come with civilization.

This change, however, is not to be deplored, but welcomed as highly beneficial. It is well, nay, essential for the progress of the race, that the houses of some should be homes for all that is highest and best in literature and the arts, and for all the refinements of civilization, rather than that none should be so. Much better this great irregularity than universal squalor. Without wealth there can be no Maecenas [Note: a rich Roman patron of the arts]. The "good old times" were not good old times . Neither master nor servant was as well situated then as to day. A relapse to old conditions would be disastrous to both-not the least so to him who serves-and would sweep away civilization with it....

. . .

We start, then, with a condition of affairs under which the best interests of the race are promoted, but which inevitably gives wealth to the few. Thus far, accepting conditions as they exist, the situation can be surveyed and pronounced good. The question then arises-and, if the foregoing be correct, it is the only question with which we have to deal-What is the proper mode of administering wealth after the laws upon which civilization is founded have thrown it into the hands of the few? And it is of this great question that I believe I offer the true solution. It will be understood that fortunes are here spoken of, not moderate sums saved by many years of effort, the returns from which are required for the comfortable maintenance and education of families. This is not wealth, but only competence, which it should be the aim of all to acquire.

There are but three modes in which surplus wealth can be disposed of. It can be left to the families of the decedents; or it can be bequeathed for public purposes; or, finally, it can be administered during their lives by its possessors. Under the first and second modes most of the wealth of the world that has reached the few has hitherto been applied. Let us in turn consider each of these modes. The first is the most injudicious. In monarchial countries, the estates and the greatest portion of the wealth are left to the first son, that the vanity of the parent may be gratified by the thought that his name and title are to descend to succeeding generations unimpaired. The condition of this class in Europe today teaches the futility of such hopes or ambitions. The successors have become impoverished through their follies or from the fall in the value of land.... Why should men leave great fortunes to their children? If this is done from affection, is it not misguided affection? Observation teaches that, generally speaking, it is not well for the children that they should be so burdened. Neither is it well for the state. Beyond providing for the wife and daughters moderate sources of income, and very moderate allowances indeed, if any, for the sons, men may well hesitate, for it is no longer questionable that great sums bequeathed oftener work more for the injury than for the good of the recipients. Wise men will soon conclude that, for the best interests of the members of their families and of the state, such bequests are an improper use of their means.

. . .

As to the second mode, that of leaving wealth at death for public uses, it may be said that this is only a means for the disposal of wealth, provided a man is content to wait until he is dead before it becomes of much good in the world.... The cases are not few in which the real object sought by the testator is not attained, nor are they few in which his real wishes are thwarted....

The growing disposition to tax more and more heavily large estates left at death is a cheering indication of the growth of a salutary change in public opinion.... Of all forms of taxation, this seems the wisest. Men who continue hoarding great sums all their lives, the proper use of which for public ends would work good to the community, should be made to feel that the community, in the form of the state, cannot thus be deprived of its proper share. By taxing estates heavily at death, the state marks its condemnation of the selfish millionaire's unworthy life.

. . . This policy would work powerfully to induce the rich man to attend to the administration of wealth during his life, which is the end that society should always have in view, as being that by far most fruitful for the people....

There remains, then, only one mode of using great fortunes: but in this way we have the true antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of the rich and the poor-a reign of harmony-another ideal, differing, indeed from that of the Communist in requiring only the further evolution of existing conditions, not the total overthrow of our civilization. It is founded upon the present most intense individualism, and the race is prepared to put it in practice by degrees whenever it pleases. Under its sway we shall have an ideal state, in which the surplus wealth of the few will become, in the best sense, the property of the many, because administered for the common good, and this wealth, passing through the hands of the few, can be made a much more potent force for the elevation of our race than if it had been distributed in small sums to the people themselves. Even the poorest can be made to see this, and to agree that great sums gathered by some of their fellowcitizens and spent for public purposes, from which the masses reap the principal benefit, are more valuable to them than if scattered among them through the course of many years in trifling amounts.

. . .

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial result for the community-the man of wealth thus becoming the sole agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer-doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves.

Document 5, The “Life Story of a Polish Sweatshop Girl” (Digital History, 1902)5…I was only a little over thirteen years of age and a greenhorn, so I received $9 a month and board and lodging, which I thought was doing well. Mother, who, as I have said, was very clever, made $9 a week on white goods, which means all sorts of underclothing, and is high class work

But mother had a very gay disposition. She liked to go around and see everything, and friends took her about New York at night and she caught a bad cold and coughed and coughed She really had hasty consumption, but she didn't know it, and I didn't know it, and she tried to keep on working, but it was no use. She had not the strength Two doctors attended her, but they could do nothing, and at last she died and I was left alone. I had saved money while out at service, but mother's sickness and funeral swept it all away and now I had to begin all over again.

Aunt Fanny had always been anxious for me to get an education, as I did not know how to read or write, and she thought that was wrong. Schools are different in Poland from what they are in this country, and I was always too busy to learn to read and write. So when mother died I thought I would try to learn a trade and then I could go to school at night and learn to speak the English language well.

So I went to work in Allen street (Manhattan) in what they call a sweatshop, making skirts by machine. I was new at the work and the foreman scolded me a great deal.

"Now, then," he would say, "this place is not for you to be looking around in. Attend to your work. That is what you have to do."

I did not know at first that you must not look around and talk, and I made many mistakes with the sewing, so that I was often called a "stupid animal." But I made $4 a week by working six days in the week For there are two Sabbaths here our own Sabbath, that comes on a Saturday, and the Christian Sabbath that comes on Sunday. It is against our law to work on our own Sabbath, so we work on their Sabbath.

In Poland I and my father and mother used to go to the synagogue on the Sabbath, but here the women don't go to the synagogue much, tho the men do. They are shut up working hard all the week long and when the Sabbath comes they like to sleep long in bed and afterward they must go out where they can breathe the air. The rabbis are strict here, but not so strict as in the old country.

I lived at this time with a girl named Ella, who worked in the same factory and made $5 a week. We had the room all to ourselves, paying $1.50 a week for it, and doing light housekeeping. It was in Allen street, and the window looked out of the back, which was good, because there was an elevated railroad in front, and in summer time a great deal of dust and dirt came in at the front windows. We were on the fourth story and could see all that was going on in the back rooms of the houses behind us, and early in the morning the sun used to come in our window.

We did our cooking on an oil stove, and lived well, as this list of our expenses for one week will show:

ELLA AND SADIE FOR FOOD (ONE WEEK)

Tea $0.06

Cocoa .10

Bread and rolls .40

Canned vegatables .20

Potatoes .10

Milk .21

Fruit .20

Butter .15

Meat .60

Fish .15

Laundry .25

Total $2.42

Add rent 1.50

Grand total $3.92

Of course, we could have lived cheaper, but we are both fond of good things and felt that we could afford them.

We paid 18 cents for a half pound of tea so as to get it good, and it lasted us three weeks, because we had cocoa for breakfast. We paid 5 cents for six rolls and 5 cents a loaf for bread, which was the best quality. Oatmeal cost us 10 cents for three and one half pounds, and we often had it in the morning, or Indian meal porridge in the place of it, costing about the same. Half a dozen eggs cost about 13 cents on average, and we could get all the meat we wanted for a good hearty meal for 20 cents two pounds of chops, or a steak, or a bit of veal, or a neck of lamb something like that. Fish included butter fish, porgies, codfish and smelts, averaging about 8 cents a pound.

Some people who buy at the last of the market, when the men with the carts want to go home, can get things very cheap, but they are likely to be stale, and we did not often do that with fish, fresh vegetables, fruit, milk or meat Things that kept well we did buy that way and got good bargains. I got thirty potatoes for 10 cents one time, tho generally I could not get more than 15 of them for that amount. Tomatoes, onions and cabbages, too, we bought that way and did well, and we found a factory where we could buy the finest broken crackers for 3 cents a pound, and another place where we got broken candy for 10 cents a pound. Our cooking was done on an oil stove, and the oil for the stove and the lamp cost us 10 cents a week.

It cost me $2 a week to live, and I had a dollar a week to spend on clothing and pleasure, and saved the other dollar. I went to night school, but it was hard work learning at first as I did not know much English.

Two years ago I came to this place, Brownsville, where so many of my people are, and where I have friends. I got work in a factory making underskirts all sorts of cheap underskirts, like cotton and calico for the summer and woolen for the winter, but never the silk, satin or velvet underskirts. I earned $4.50 a week and lived on $2 a week, the same as before.

I got a room in the house of some friends who lived near the factory. I pay $1 a week for the room and am allowed to do light housekeepingthat is, cook my meals in it. I get my own breakfast in the morning, just a cup of coffee and a roll, and at noon time I come home to dinner and take a plate of soup and a slice of bread with the lady of the house. My food for a week costs a dollar, just as it did in Allen street, and I have the rest of my money to do as I like with. I am earning $5.50 a week now, and will probably get another increase soon.

It isn't piecework in our factory, but one is paid by the amount of work done just the same. So it is like piecework. All the hands get different amounts, some as low as $3.50 and some of the men as high as $16 a week. The factory is in the third story of a brick building. It is in a room twenty feet long and fourteen broad There are fourteen machines in it. I and the daughter of the people with whom I live work two of these machines. The other operators are all men, some young and some old…

I get up at half past five o'clock every morning and make myself a cup of coffee on the oil stove. I eat a bit of bread and perhaps some fruit and then go to work Often I get there soon after six o'clock so as to be in good time, tho the factory does not open till seven I have heard that there is a sort of clock that calls you at the very time you want to get up, but I can't believe that because I don't see how the clock would know.

At seven o' clock we all sit down to our machines and the boss brings to each one the pile of work that he or she is to finish during the day, what they call in English their" stint" This pile is put down beside the machine and as soon as a skirt is done it is laid on the other side of the machine. Sometimes the work is not all finished by six o'clock and then the one who is behind must work overtime. Sometimes one is finished ahead of time and gets away at four or five o'clock, but generally we are not done till six o'clock.

The machines go like mad all day, because the faster you work the more money you get Sometimes in my haste I get my finger caught and the needle goes right through it It goes so quick tho, that it does not hurt much. I bind the finger up with a piece of cotton and go on working. We all have accidents like that Where the needle goes through the nail it makes a sore finger, or where it splinters a bone it does much harm. Sometimes a finger has to come off. Generally, tho, one can be cured by a salve.

All the time we are working the boss walks about examining the finished garments and making us do them over again if they are not just right So we have to be careful as well as swift But I am getting so good at the work that within a year I will be making $7 a week, and then I can save at least $3.50 a week. I have over $200 saved now.

The machines are all run by foot power, and at the end of the day one feels so weak that there is a great temptation to lie right down and sleep. But you must go out and get air, and have some pleasure. So instead of lying down I go out, generally with Henry. Sometimes we go to Coney Island, where there are good dancing places, and sometimes we go to Ulmer Park to picnics. I am very fond of dancing, and, in fact, all sorts of pleasure. I go to the theater quite often, and like those plays that make you cry a great deal "The Two Orphans" is good. Last time I saw it I cried all night because of the hard times that the children had in the play. I am going to see it again when it comes here.

For the last two winters I have been going to night school at Public School 84 on Glenmore avenue. I have learned reading, writing and arithmetic. I can read quite well in English now and I look at the newspapers every day. I read English books, too, sometimes. The last one that I read was"A Mad Marriage," by Charlotte Braeme. She's a grand writer and makes things just like real to you. You feel as if you were the poor girl yourself going to get married to a rich duke.

I am going back to night school again this winter. Plenty of my friends go there. Some of the women in my class are more than forty years of age. Like me, they did not have a chance to learn anything in the old country. It is good to have an education; it makes you feel higher. Ignorant peole are all low. People say now that I am clever and fine in conversation.

We have just finished a strike in our business. It spread all over and the United Brotherhood of Garment Workers was in it That takes in the cloakmakers, coatmakers, and all the others. We struck for shorter hours, and after being out four weeks won the fight We only have to work nine and a half hours a day and we get the same pay as before. So the union does good after all in spite of what some people say against it that it just takes our money and does nothing.

I pay 25 cents a month to the union, but I do not begrudge that because it is for our benefit The next strike is going to be for a raise of wages, which we all ought to have. But tho I belong to the union I am not a Socialist or an Anarchist I don't know exactly what those things mean There is a little expense for charity, too. If any worker is injured or sick we all give money to help.

Some of the women blame me very much because I spend so much money on clothes. They say that instead of a dollar a week I ought not to spend more than twenty five cents a week on clothes, and that I should save the rest But a girl must have clothes if she is to go into high society at Ulmer Park or Coney Island or the theatre. Those who blame me are the old country people who have old fashioned notions, but the people who have been here a long time know better. A girl who does not dress well is stuck in a corner, even if she is pretty, and Aunt Fanny says that I do just right to put on plenty of style.

I have many friends and we often have jolly parties. Many of the young men like to talk to me, but I don't go out with any except Henry.

Lately he has been urging me more and more to get married -but I think I'll wait

Document 6, Jim Crow in the South (American Memory 1886)6 (Primary Source Nexus 1913)7In the Ohio House of Representatives, March 10, 1886.

Mr. Speaker: We have before us today a subject that is of great interest to the people of the commonwealth of Ohio; one of those questions that called for the efforts of great men in the past, which have been the cause of the organization of the party, and have been the life of the same. I would apologize to this House and to my constituents for the interest I am taking in this work if it were not the continuation of the work of the moral heroes of this country, It is the carrying forward of the work begun by J. G Birney, who, in 1840, had only 7,059 persons on his side. In 1844 he had 62,300; and the columns increased, so that in 1848 there were 291,263 men in the army of the Free Soil Party, with Martin Van Buren as leader.

In 1852 J.P. Hale led the host, with 156,149 bearing his banner in every conquest and victory. In 1856, J. C. Fremont, the "Pathfinder," marched to the bell of Liberty, with 1,341,266 true and tried men. In 1860, the great emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, led 1,866,352. In 1864, when the watchword of the nation. "Freedom and the Union," had an army of 2,216,067. the great emancipator performed his work, broke the chain from the limbs of four millions of human beings, and bade them stand up in the dignity of freedom and defend the Constitution and the Union.

The next work was that of January 13th, 1865. The Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States was passed, which forever prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude in this land. I was present in the Hall of Congress when the great act was performed. It was an occasion to be remembered by all. The hour had arrived for the calling up of that measure. J. M. Ashley, of Ohio, had charge of the measure. The discussion was finished, the vote taken, the result announced. Then the multitude was wild with joy. Men ran, jumped, hugged cried and hallooed; hats were thrown in the air, handkerchiefs were waved by the ladies, old men were young--dignity in men and women surrendered to their joy. The halls were filled with the shouts and cheers of the hour. At the passage of the bill a messenger ran to the front of the Capitol, where a cannon was waiting to announce the news of great joy. In a moment the sound of the cannon was heard, and a battery at the corner of Mt. Vernon avenue and Fourteenth street joined in the joy, and the thunder was sounded along the sky. The death knell of slavery was sounded by the brazen notes of war; the bells of the city tolled forth tunes and chimed the notes of freedom, while the hills resounded with the echoes of the shouts of liberty. It was a grand day for the sons of Liberty and the daughters of Oppression. The scene in the city was indescribable. In the hotels the waiter and the guest congratulated each other. Dinner was interrupted with songs, shouts and cheers. They ate a while, then sang a while, shouted a while, and cheered a while. So, this event was one of the grandest ever known in the history of the city and among the party. It is so far-reaching in its results, so beneficent in its effects--the lifting of the burden from the millions, the closing of the gateway of Oppression, and the opening of the avenues of Universal Freedom for the hundred generations--and, as the years and, as the years roll by, and men appreciate the good deed of the fathers, this act will stand as the grandest in the calendar of legislation in the country.

"Now that we have emancipated him, and he can no more be a slave, what are we going to do with him?" was the question of the hour. "What are his legal rights?" What must we do to protect him in his new home of freedom? and what must we do for him?" Then, in 1866, the National Convention of colored men met in Washington, and presented to the United States Congress papers defending the position, and asking for the reconstruction of the Southern States on the basis of universal freedom and exact equality. The Constitution grants to every man, woman and child equal rights in every State. It is on this that we demand the repeal of these laws; they are contrary to the spirit of the genius of our institutions and the letter of our Constitution, for it guarantees to every citizen his equal rights, his civil rights, and allows him to enjoy the universal blessings of manhood.

We invite you to come with us down the avenues of universal history, and take antiquity by the hand, and, as we roll back the scroll of centuries, and behold the congregated halls, we hear the assembled, throng, we hear the harping and singing host. We pour over the archives; we converse with the king and his subjects; we hear the tale of sorrow from the beggar; we attend to the wants of the distressed, and retire to our State to find that though years have passed, and thousands of lives have been offered on the altar of our common country, an oblation to human freedom by the patriotic, there remains work to be done by the friends of right and justice. The ruins of the ancient cities are to us monuments, that say, "Righteousness exhalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people."

The State is under obligations to protect virtue and to prevent crime. It is the duty of the nation to protect and preserve the purity and freedom of the ballot, because on this depends the life of the nation.

The nation is under obligations to protect all citizens from injustice.

A well-governed State will guard and foster its industries so as to produce the most good to the greatest number.

The nation must fulfill its obligations to the poor man and the freeman. When the nation asked the negro to assist in saving the life of the nation, it guaranteed to him all the rights of an American citizen.

Document 7, Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” discusses dangerous working conditions in the meatpacking industry (History Matters, 1904)8Jurgis heard of these things little by little, in the gossip of those who were obliged to perpetrate them. It seemed as if every time you met a person from a new department, you heard of new swindles and new crimes. There was, for instance, a Lithuanian who was a cattle-butcher for the plant where Marija had worked, which killed meat for canning only; and to hear this man describe the animals which came to his place would have been worth while for a Dante or a Zola. It seemed that they must have agencies all over the country, to hunt out old and crippled and diseased cattle to be canned. There were cattle which had been fed on “whiskey-malt,” the refuse of the breweries, and had become what the men called “steerly”—which means covered with boils. It was a nasty job killing these, for when you plunged your knife into them they would burst and splash foul-smelling stuff into your face; and when a man’s sleeves were smeared with blood, and his hands steeped in it, how was he ever to wipe his face, or to clear his eyes so that he could see? It was stuff such as this that made the “embalmed beef” that had killed several times as many United States soldiers as all the bullets of the Spaniards; only the army beef, besides, was not fresh canned, it was old stuff that had been lying for years in the cellars.

Then one Sunday evening, Jurgis sat puffing his pipe by the kitchen stove, and talking with an old fellow whom Jonas had introduced, and who worked in the canning-rooms at Durham’s; and so Jurgis learned a few things about the great and only Durham canned goods, which had become a national institution. They were regular alchemists at Durham’s; they advertised a mushroom-catsup, and the men who made it did not know what a mushroom looked like. They advertised “potted chicken,”—and it was like the boarding-house soup of the comic papers, through which a chicken had walked with rubbers on. Perhaps they had a secret process for making chickens chemically—who knows? said Jurgis’s friend; the things that went into the mixture were tripe, and the fat of pork, and beef suet, and hearts of beef, and finally the waste ends of veal, when they had any. They put these up in several grades, and sold them at several prices; but the contents of the cans all came out of the same hopper. And then there was “potted game” and “potted grouse,” "potted ham,“ and ”devilled ham“—de-vyled, as the men called it. ”De-vyled“ ham was made out of the waste ends of smoked beef that were too small to be sliced by the machines; and also tripe, dyed with chemicals so that it would not show white; and trimmings of hams and corned beef; and potatoes, skins and all; and finally the hard cartilaginous gullets of beef, after the tongues had been cut out. All this ingenious mixture was ground up and flavored with spices to make it taste like something. Anybody who could invent a new imitation had been sure of a fortune from old Durham, said Jurgis’s informant; but it was hard to think of anything new in a place where so many sharp wits had been at work for so long; where men welcomed tuberculosis in the cattle they were feeding, because it made them fatten more quickly; and where they bought up all the old rancid butter left over in the grocery-stores of a continent, and ”oxidized" it by a forced-air process, to take away the odor, rechurned it with skim-milk, and sold it in bricks in the cities! Up to a year or two ago it had been the custom to kill horses in the yards—ostensibly for fertilizer; but after long agitation the newspapers had been able to make the public realize that the horses were being canned. Now it was against the law to kill horses in Packingtown, and the law was really complied with—for the present, at any rate. Any day, however, one might see sharp-horned and shaggy-haired creatures running with the sheep—and yet what a job you would have to get the public to believe that a good part of what it buys for lamb and mutton is really goat’s flesh!

There was another interesting set of statistics that a person might have gathered in Packingtown—those of the various afflictions of the workers. When Jurgis had first inspected the packing-plants with Szedvilas, he had marvelled while he listened to the tale of all the things that were made out of the carcasses of animals, and of all the lesser industries that were maintained there; now he found that each one of these lesser industries was a separate little inferno, in its way as horrible as the killing-beds, the source and fountain of them all. The workers in each of them had their own peculiar diseases. And the wandering visitor might be sceptical about all the swindles, but he could not be sceptical about these, for the worker bore the evidence of them about on his own person—generally he had only to hold out his hand.

There were the men in the pickle-rooms, for instance, where old Antanas had gotten his death; scarce a one of these that had not some spot of horror on his person. Let a man so much as scrape his finger pushing a truck in the pickle-rooms, and he might have a sore that would put him out of the world; all the joints in his fingers might be eaten by the acid, one by one. Of the butchers and floorsmen, the beef-boners and trimmers, and all those who used knives, you could scarcely find a person who had the use of his thumb; time and time again the base of it had been slashed, till it was a mere lump of flesh against which the man pressed the knife to hold it. The hands of these men would be criss-crossed with cuts, until you could no longer pretend to count them or to trace them. They would have no nails,—they had worn them off pulling hides; their knuckles were swollen so that their fingers spread out like a fan. There were men who worked in the cooking-rooms, in the midst of steam and sickening odors, by artificial light; in these rooms the germs of tuberculosis might live for two years, but the supply was renewed every hour. There were the beef-luggers, who carried two-hundred-pound quarters into the refrigerator-cars; a fearful kind of work, that began at four o’clock in the morning, and that wore out the most powerful men in a few years. There were those who worked in the chilling-rooms, and whose special disease was rheumatism; the time-limit that a man could work in the chilling-rooms was said to be five years. There were the woolpluckers, whose hands went to pieces even sooner than the hands of the pickle-men; for the pelts of the sheep had to be painted with acid to loosen the wool, and then the pluckers had to pull out this wool with their bare hands, till the acid had eaten their fingers off. There were those who made the tins for the canned-meat; and their hands, too, were a maze of cuts, and each cut represented a chance for blood-poisoning. Some worked at the stamping-machines, and it was very seldom that one could work long there at the pace that was set, and not give out and forget himself, and have a part of his hand chopped off. There were the “hoisters,” as they were called, whose task it was to press the lever which lifted the dead cattle off the floor. They ran along upon a rafter, peering down through the damp and the steam; and as old Durham’s architects had not built the killing-room for the convenience of the hoisters, at every few feet they would have to stoop under a beam, say four feet above the one they ran on; which got them into the habit of stooping, so that in a few years they would be walking like chimpanzees. Worst of any, however, were the fertilizer-men, and those who served in the cooking-rooms. These people could not be shown to the visitor,—for the odor of a fertilizer-man would scare any ordinary visitor at a hundred yards, and as for the other men, who worked in tank-rooms full of steam, and in some of which there were open vats near the level of the floor, their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting,—sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!

Document 8, Jacob Riis photograph, “It Costs a Dollar a Month to Sleep in These Sheds” (University of Virginia, 1902)9

When we speak of the restriction of immigration, at the present time, we have not in mind measures undertaken for the purpose of straining out from the vast throngs of foreigners arriving at our ports a few hundreds, or possibly thousands of persons, deaf, dumb, blind, idiotic, insane, pauper, or criminal, who might otherwise become a hopeless burden upon the country, perhaps even an active source of mischief. The propriety, and even the necessity of adopting such measures is now conceded by men of all shades of opinion concerning the larger subject. There is even noticeable a rather severe public feeling regarding the admission of persons of any of the classes named above; perhaps one might say, a certain resentment at the attempt of such persons to impose themselves upon us. We already have laws which cover a considerable part of this ground; and so far as further legislation is needed, it will only be necessary for the proper executive department of the government to call the attention of Congress to the subject. There is a serious effort on the part of our immigration officers to enforce the regulations prescribed, though when it is said that more than five thousand persons have passed through the gates at Ellis Island, in New York harbor, during the course of a single day, it will be seen that no very careful scrutiny is practicable.

It is true that in the past there has been gross and scandalous neglect of this matter on the part both of government and people, here in the United States. For nearly two generations, great numbers of persons utterly unable to earn their living, by reason of one or another form of physical or mental disability, and others who were, from widely different causes, unfit to be members of any decent community, were admitted to our ports without challenge or question. It is a matter of official record that in many cases these persons had been directly shipped to us by states or municipalities desiring to rid themselves of a burden and a nuisance; while it could reasonably be believed that the proportion of such instances was far greater than could be officially ascertained. But all this is of the past. The question of the restriction of immigration to-day does not deal with that phase of the subject. What is proposed is, not to keep out some hundreds, or possibly thousands of persons, against whom lie specific objections like those above indicated, but to exclude perhaps hundreds of thousands, the great majority of whom would be subject to no individual objections; who, on the contrary, might fairly be expected to earn their living here in this new country, at least up to the standard known to them at home, and probably much more. The question to-day is not of preventing the wards of our almshouses, our insane asylums, and our jails from being stuffed to repletion by new arrivals from Europe; but of protecting the American rate of wages, the American standard of living, and the quality of American citizenship from degradation through the tumultuous access of vast throngs of ignorant and brutalized peasantry from the countries of eastern and southern Europe.

The first thing to be said respecting any serious proposition importantly to restrict immigration into the United States is, that such a proposition necessarily and properly encounters a high degree of incredulity, arising from the traditions of our country. From the beginning, it has been the policy of the United States, both officially and according to the prevailing sentiment of our people, to tolerate, to welcome, and to encourage immigration, without qualification and without discrimination. For generations, it was the settled opinion of our people, which found no challenge anywhere, that immigration was a source of both strength and wealth. Not only was it thought unnecessary carefully to scrutinize foreign arrivals at our ports, but the figures of any exceptionally large immigration were greeted with noisy gratulation. In those days the American people did not doubt that they derived a great advantage from this source. It is, therefore, natural to ask, Is it possible that our fathers and our grandfathers were so far wrong in this matter? Is it not, the rather, probable that the present anxiety and apprehension on the subject are due to transient causes or to distinctly false opinions, prejudicing the public mind? The challenge which current proposals for the restriction of immigration thus encounter is a perfectly legitimate one, and creates a presumption which their advocates are bound to deal with. Is it, however, necessarily true that if our fathers and grandfathers were right in their view of immigration in their own time, those who advocate the restriction of immigration to-day must be in the wrong? Does it not sometimes happen, in the course of national development, that great and permanent changes in condition require corresponding changes of opinion and of policy?...

Document 10, Cartoon illustrating politics in the Gilded Age (University of Texas 1870) 11

The Maine Blown Up

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Terrible Explosion on Board the United States Battleship in Havana Harbor

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MANY PERSONS KILLED AND WOUNDED

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All the Boats of the Spanish Cruiser Alfonso XII, Assisting in the Work of Relief

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

None of the Wounded Men Able to Give Any Explanation of the Cause of the Disaster

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Havana, Feb. 15 -- At 9:45 o'clock this evening a terrible explosion took place on board the United States battleship Maine in Havana Harbor.

Many persons were killed or wounded. All the boats of the Spanish cruiser Alfonso XII. are assisting.

As yet the cause of the explosion is not apparent. The wounded sailors of the Maine are unable to explain it. It is believed that the battleship is totally destroyed.

The explosion shook the whole city. The windows were broken in nearly all the houses.

The correspondent of the Associated Press says he has conversed with several of the wounded sailors and understands from them that the explosion took place while they were asleep, so that they can give no particulars as to the cause.

WHAT SENOR DE LOME SAYS

He Declares That No Spaniard Would Be Guilty of Causing Such a Disaster

Senor de Lome, the departing ex-Minister of Spain to this country, who arrived in this city last night, and went to the Hotel St. Marc, at Fifth Avenue and Thirty-ninth Street, was awakened on the receipt of the news from Havana.

He refused to believe the report at first. When he had been assured of the truth of the story he said that there was no possibility that the Spaniards had anything to do with the destruction of the Maine.

No Spaniard, he said, would be guilty of such an act. If the report was true, he said, the explosion must have been caused by some accident on board the warship.

Document 12, Teddy Roosevelt encourages “The Strenuous Life” (Theodore Roosevelt Association 1899)13In speaking to you, men of the greatest city of the West, men of the State which gave to the country Lincoln and Grant, men who preëminently and distinctly embody all that is most American in the American character, I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.

A life of slothful ease, a life of that peace which springs merely from lack either of desire or of power to strive after great things, is as little worthy of a nation as of an individual. I ask only that what every self-respecting American demands from himself and from his sons shall be demanded of the American nation as a whole. Who among you would teach your boys that ease, that peace, is to be the first consideration in their eyes-to be the ultimate goal after which they strive? You men of Chicago have made this city great, you men of Illinois have done your share, and more than your share, in making America great, because you neither preach nor practice such a doctrine. You work yourselves, and you bring up your sons to work. If you are rich and worth your salt, you will teach your sons that though they may have leisure, it is not to be spent in idleness; for wisely used leisure merely means that those who possess it, being free from the necessity of working for their livelihood, are all bound to carry on some kind of non-remunerative work in science, in letters, in art, in exploration, in historical research-work of this type we most need in this country, the successful carrying out of which reflects most honor upon the nation. We do not admire the man of timid peace. We admire the man who embodies victorious effort; the man who never wrongs his neighbor, who is prompt to help a friend, but who has those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life. It is hard to fail, but it is worse to never have tried to succeed. In this life we get nothing save by effort. Freedom from effort in the present merely means that there has been some stored up effort in the past. A man can be freed from the necessity of work only by the fact that he or his fathers before him have worked to good purpose. If the freedom thus purchased is used aright, and the man still does actual work, though of a different kind, whether as a writer or as a general, whether in the field of politics or in the field of exploration and adventure, he shows he deserves his good fortune. But if he treats this period of freedom from the need of actual labor as a period , not of preparation, but of mere enjoyment, even though perhaps not of the vicious enjoyment, he shows that he is simply a cumberer of the earth's surface, and he surely unfits himself to hold his own with his fellows if the need to do so should again arise. A mere life of ease is not in the end a very satisfactory life, and, above all, it is a life which ultimately unfits those who follow it for serious work in the world…

We of this generation do not have to face a task such as that our fathers faced, but we have our tasks, and woe to us if we fail to perform them! We cannot, if we would, play the part of China, and be content to rot by inches in ignoble ease within our borders, taking no interest in what goes on beyond them, sunk in scrambling commercialism; heedless of higher life, the life of aspiration, of toil and risk, busying ourselves only with the wants of our bodies for the day, until suddenly we should find, beyond a shadow of question, what China has already found, that in this world the nation that has trained itself into a career of unwarlike and isolated ease is bound, in the end, to go down before other nations which have not lost the manly and adventurous qualities. If we are to be a really great people, we must strive in good faith to play a great part in the world. We cannot avoid meeting great issues. All that we can determine for ourselves is whether we shall meet them well or ill. In 1898 we could not help being brought face to face with the problem of war with Spain. All we could decide was whether we should shrink like cowards from the contest, or enter into it as beseemed a brave and high-spirited people; and, once in, whether failure or success shall crown our banners. So it is now. We cannot avoid the responsibilities that confront us in Hawaii, Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Phillippines. All we can decide is whether we shall meet them in a way that will redound to the national credit, of whether we shall make of our dealings with these new problems a dark and shameful page in our history. To refuse to deal with them at all merely amounts to dealing with them badly. We have a given problem to solve. If we undertake the solution, there is, of course, always danger that we may not solve it aright; but to refuse to undertake the solution simply renders it certain that we cannot possibly solve it aright. The timid man, the lazy man, the man who distrusts his country, the over-civilized man, who has lost the great fighting, the masterful values, the ignorant man, and the man of dull mind, whose soul is incapable of feeling the mighty lift that thrills "stern men with empires in their brains"-all these, of course, shrink from seeing the nation undertake its new duties; shrink from seeing us build a navy and an army adequate to our needs; shrink from seeing us do our share of the world's work, by bringing order out of the chaos in the great, fair tropic islands from which the valor of our soldiers and sailors has driven the Spanish flag. These are the men who fear the strenuous life, who fear the only national life which is really worth leading. They believe in that cloistered life which saps the hearty virtues in a nation, as it saps them in the individual; or else they are wedded to that base spirit of grain and greed which recognizes commercialism the be-all and end-all of national life, instead of realizing that, though an indispensable element, it is, after all, but one of the many elements that go to make up true national greatness. No country can long endure if its foundations are not laid deep in the material prosperity which comes from thrift, from business energy and enterprise, from hard, unsparing efforts in the fields of industrial activity; but neither was any nation ever yet truly great if it relied upon material prosperity alone. All honor must be paid to the architects of our material prosperity, to the great captains of industry who have built our factories and our railroads, to the strong men who toil for wealth with brain or hand; for great is the debt of the nation to these and their kind. But our debt is yet greater to the men whose highest type is to be found in a statesman like Lincoln, a soldier like Grant. They showed by their lives that they recognized the law of work, the law of strife; they toiled to win a competence for themselves and those dependent upon them; but they recognized that there were yet other and even loftier duties - duties to the nation and duties to the race.

We cannot sit huddled within our own borders and avow ourselves merely an assemblage of well-to-do hucksters who care nothing for what happens beyond. Such a policy would defeat even its own end; for as the nations grow to have ever wider and wider interests, and are brought into closer and closer contact, if we are to hold our own in the struggle for naval and commercial supremacy, we must build up our power without our own borders. We must build the isthmian canal, and we must grasp the points of vantage which will enable us to have our say in deciding the destiny of the oceans of the East and the West…

…When once we have put down armed resistance, when once our rule is acknowledged, than an even more difficult task will begin, for then we must see to it that the islands are administered with absolute honesty and with good judgement. If we let the public service of the islands be turned into prey of the spoils of politician, we shall have begun to tread the path which Spain trod to her own destruction. We must send out there only good and able men, chosen for their fitness, and not because of their partizan service, and these men must not only administer impartial justice to the natives and serve their own government with honesty and fidelity, but show the utmost tact and firmness, remembering that, with such people as those with whom we are to deal, weakness is the greatest of crimes, and next to weakness comes lack of consideration for their principles and prejudices.

I preach to you, then, my countrymen, that our country calls not for the life of ease but for the life of strenuous endeavor. The twentieth century looms before us big with the fate of many nations. If we stand idly by, if we seek merely swollen, slothful ease and ignoble peace, if we shrink from the hard contests where men must win at the hazard of their lives and at the risk of all they hold dear, then the bolder and stronger peoples will pass us by, and will win for themselves the domination of the world. Let us therefore boldly face the life of strife, resolute to do our duty well and manfully; resolute to be both honest and brave, to serve high ideals, yet to use practical methods. Above all, let us shrink from no strife, through hard and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness.

Document 13, Mark Twain condemns American Imperialism (Library of Congress 1900)14From the New York Herald, October 15, 1900:

I left these shores, at Vancouver, a red-hot imperialist. I wanted the American eagle to go screaming into the Pacific. It seemed tiresome and tame for it to content itself with he Rockies. Why not spread its wings over the Phillippines, I asked myself? And I thought it would be a real good thing to do

I said to myself, here are a people who have suffered for three centuries. We can make them as free as ourselves, give them a government and country of their own, put a miniature of the American constitution afloat in the Pacific, start a brand new republic to take its place among the free nations of the world. It seemed to me a great task to which had addressed ourselves.

But I have thought some more, since then, and I have read carefully the treaty of Paris, and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Phillippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. . .

It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.

Post-Reading Exercises1. Pretend you are a muckraking journalist who has been assigned to write an expose about social, moral and political corruption in the United States during the Gilded Age. Write an article discussing the social, moral and political corruption that is occurring; you should be sure to use specific examples and quotes from the primary source documents in this chapter.

2. Using Documents 6 and 9, discuss the ways in which minorities, both African American and immigrants from around the globe, were viewed at the turn of the century. Make sure to also explain the historical context for why white Americans made the arguments they made about minorities, and be sure to bring in specific examples and quotes from Documents 6 and 9 in the course of your answer.

3. JOURNAL OPTION: For this chapter of OB, instead of answering Question 1 or 2, you may instead choose to turn in a 2-4 page typed document (double-spaced) with brief notes on each document in the chapter, as well as 5 questions about the chapter’s material. Please see the handout under Files titled “Journal Notes/Questions Guide” for more specific instructions on how to do this properly.

Works CitedDocument 5: Digital History. (1902, September 25). Digital History. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from The Story of a Sweatshop Girl; Sadie Frowne: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/social_history/5sweatshop_girl.cfm

Document 4: Fordham University. (1889). Fordham University. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Modern History Sourcebook: Andrew Carnegie: The Gospel of Wealth: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1889carnegie.html

Document 7 : History Matters. (1904). History Matters. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Upton Sinclair Hits His Readers in the Stomach: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5727/

Document 9: The Atlantic. (1896, June). The Atlantic. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Restriction of Immigration- Francis A Walker: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1896/06/restriction-of-immigration/6011/

Document 8:University of Virginia. (1902). University of Virginia. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Documenting "The Other Half": Riis photos: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma01/Davis/photography/images/riisphotos/slideshow1.html

Document 3: about.com Classic Literature. (1893). about.com Classic Literature. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Stephen Crane, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets: http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/scrane/bl-scrane-mag-12.htm

Document 6: American Memory. (1886, March 10). American Memory. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from African American Perspectives: Pamphlets from the Daniel A.P. Murray Collection, 1818-1907: http:..memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/murray:@field(DOCID+@lit(lcrbmrpt0d06div1))

Document 13: Library of Congress. (1900, October 15). Library of Congress. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War: Mark Twain: http://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/twain.htm

Document 1: Mark Twain Project. (1873, December 11). Mark Twain Project. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Preface to the Routledge Gilded Age: http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/MTDP00364.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp

Document 12: Theodore Roosevelt Association. (1899, April 10). Theodore Roosevelt Association. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Theodore Roosevelt Speeches: The Strenuous Life: http://www.theodoreroosevelt.org/research/speech%20strenuous.htm

Document 10: University of Texas. (1870, January 1). University of Texas. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from Boss Tweed: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/gov310/SL/Boss_Tweed/index.html