Do you believe that the United States should commit to the Paris Agreement? What arguments most influenced your decision? Do you believe that we will experience significant global warming during this

Kyoto Protocol

international treaty, 1997

WRITTEN BY

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Encyclopaedia Britannica's editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working on that content or via study for an advanced degree....

See Article History

Alternative Title: Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

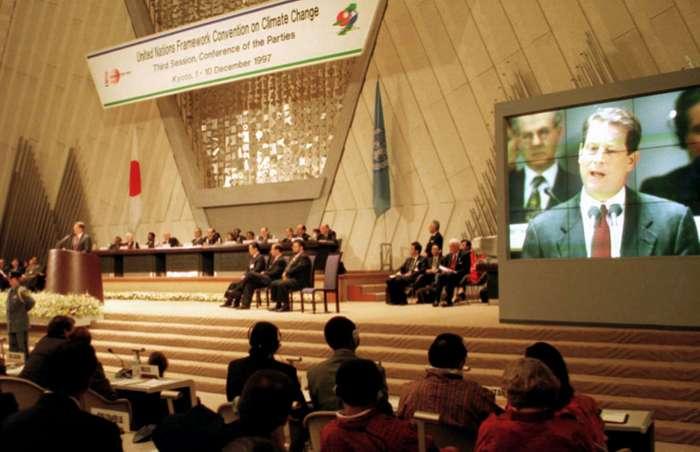

Kyoto Protocol, in full Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, international treaty, named for the Japanese city in which it was adopted in December 1997, that aimed to reduce the emission of gases that contribute to global warming. In force since 2005, the protocol called for reducing the emission of six greenhouse gases in 41 countries plus the European Union to 5.2 percent below 1990 levels during the “commitment period” 2008–12. It was widely hailed as the most significant environmental treaty ever negotiated, though some critics questioned its effectiveness.

Kyoto Protocol

U.S. Vice Pres. Al Gore delivering the opening speech of the conference in Kyōto, Japan, that led to the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, December 1997.

Katsumi Kasahara/AP Images

Background and provisions

The Kyoto Protocol was adopted as the first addition to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), an international treaty that committed its signatories to develop national programs to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases. Greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), affect the energy balance of the global atmosphere in ways expected to lead to an overall increase in global average temperature, known as global warming (see also greenhouse effect). According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, established by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization in 1988, the long-term effects of global warming would include a general rise in sea level around the world, resulting in the inundation of low-lying coastal areas and the possible disappearance of some island states; the melting of glaciers, sea ice, and Arctic permafrost; an increase in the number of extreme climate-related events, such as floods and droughts, and changes in their distribution; and an increased risk of extinction for 20 to 30 percent of all plant and animal species. The Kyoto Protocol committed most of the Annex I signatories to the UNFCCC (consisting of members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and several countries with “economies in transition”) to mandatory emission-reduction targets, which varied depending on the unique circumstances of each country. Other signatories to the UNFCCC and the protocol, consisting mostly of developing countries, were not required to restrict their emissions. The protocol entered into force in February 2005, 90 days after being ratified by at least 55 Annex I signatories that together accounted for at least 55 percent of total carbon dioxide emissions in 1990.

The protocol provided several means for countries to reach their targets. One approach was to make use of natural processes, called “sinks,” that remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The planting of trees, which take up carbon dioxide from the air, would be an example. Another approach was the international program called the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which encouraged developed countries to invest in technology and infrastructure in less-developed countries, where there were often significant opportunities to reduce emissions. Under the CDM, the investing country could claim the effective reduction in emissions as a credit toward meeting its obligations under the protocol. An example would be an investment in a clean-burning natural gas power plant to replace a proposed coal-fired plant. A third approach was emissions trading, which allowed participating countries to buy and sell emissions rights and thereby placed an economic value on greenhouse gas emissions. European countries initiated an emissions-trading market as a mechanism to work toward meeting their commitments under the Kyoto Protocol. Countries that failed to meet their emissions targets would be required to make up the difference between their targeted and actual emissions, plus a penalty amount of 30 percent, in the subsequent commitment period, beginning in 2012; they would also be prevented from engaging in emissions trading until they were judged to be in compliance with the protocol. The emission targets for commitment periods after 2012 were to be established in future protocols.

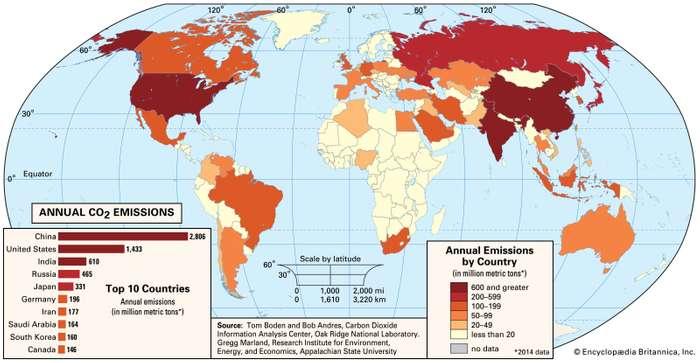

carbon dioxide emissions

Map of annual carbon dioxide emissions by country in 2014.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Challenges

Although the Kyoto Protocol represented a landmark diplomatic accomplishment, its success was far from assured. Indeed, reports issued in the first two years after the treaty took effect indicated that most participants would fail to meet their emission targets. Even if the targets were met, however, the ultimate benefit to the environment would not be significant, according to some critics, since China, the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gases, and the United States, the world’s second largest emitter, were not bound by the protocol (China because of its status as a developing country and the United States because it had not ratified the protocol). Other critics claimed that the emission reductions called for in the protocol were too modest to make a detectable difference in global temperatures in the subsequent several decades, even if fully achieved with U.S. participation. Meanwhile, some developing countries argued that improving adaptation to climate variability and change was just as important as reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Treaty extension and replacement

At the 18th Conference of the Parties (COP18), held in Doha, Qatar, in 2012, delegates agreed to extend the Kyoto Protocol until 2020. They also reaffirmed their pledge from COP17, which had been held in Durban, South Africa, in 2011, to create a new, comprehensive, legally binding climate treaty by 2015 that would require greenhouse-gas-producing countries—including major carbon emitters not abiding by the Kyoto Protocol (such as China, India, and the United States)—to limit and reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. The new treaty, planned for implementation in 2020, would fully replace the Kyoto Protocol.

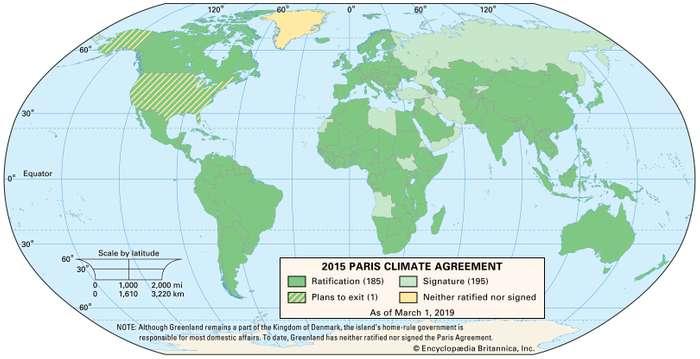

After a series of conferences mired in disagreements, delegates at the COP21, held in Paris, France, in 2015, signed a global but nonbinding agreement to limit the increase of the world’s average temperature to no more than 2 °C (3.6 °F) above preindustrial levels while at the same time striving to keep this increase to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above preindustrial levels. The landmark accord, signed by all 196 signatories of the UNFCCC, effectively replaced the Kyoto Protocol. It also mandated a progress review every five years and the development of a fund containing $100 billion by 2020—which would be replenished annually—to help developing countries adopt non-greenhouse-gas-producing technologies.

Paris Agreement adoption status

Each country's adoption status of the Paris Agreement. Convening in Paris in 2015, world leaders and other delegates signed a global but nonbinding agreement to limit the increase of the world's average temperature.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc./Kenny Chmielewski

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica This article was most recently revised and updated by John P. Rafferty, Editor.

Learn More in these related Britannica articles:

global warming: The UN Framework Convention and the Kyoto Protocol

The reports of the IPCC and the scientific consensus they reflect have provided one of the most prominent bases for the formulation of climate-change policy. On a global scale, climate-change policy is guided by two major treaties: the United Nations Framework Convention on…

climate: Climate, humans, and human affairs

…Kingdom and Australia and the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change are some examples of attempts to combat deleterious environmental change associated with the release of additional carbon dioxide into the air. If humans are to maintain the Earth-atmosphere system, it is through the social…

United Nations: The environment

…amended in 1997 by the Kyoto Protocol and in 2015 by the Paris Agreement on climate change, both of which aimed to limit global average temperature increases through reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.…

Title: Global Warming: An Overview. By: Driscoll, Sally Flynn, Points of View: Global Warming, 6/30/2019

Database: Points of View Reference Center

Global Warming: An Overview

Global warming refers to the increase in the earth's average temperature that occurs naturally or, as theorized in recent years, is induced by human activity. Most discussions on global warming today cite a correlation between an increase in global temperature and the increase in carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the atmosphere. Human activity increases the amount of these gases in the atmosphere and, as a result of the greenhouse effect, increases the earth's temperature. As the earth's temperature rises, glaciers melt, ocean levels rise, and unusual weather patterns occur. Scientists warn of the loss of ecosystems and the endangerment of human lives and communities as a result of climate change.

Global warming refers to the increase in the earth's average temperature that occurs naturally or, as theorized in recent years, is induced by human activity. Most discussions on global warming today cite a correlation between an increase in global temperature and the increase in carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the atmosphere. Human activity increases the amount of these gases in the atmosphere and, as a result of the greenhouse effect, increases the earth's temperature. As the earth's temperature rises, glaciers melt, ocean levels rise, and unusual weather patterns occur. Scientists warn of the loss of ecosystems and the endangerment of human lives and communities as a result of climate change.

Ozone, a gas which occurs naturally in the atmosphere as well as being a byproduct of some fossil fuels, also plays a role in global warming. Most of the naturally occurring ozone is found in the ozone layer, an upper layer of the earth's atmosphere that absorbs ultraviolet radiation that is potentially harmful to humans. In the late twentieth century, the ozone layer became significantly depleted, and scientists have made the case that CFCs, which were nonexistent until the twentieth century, contributed to this depletion by reacting with ozone molecules and causing them to break apart into three oxygen atoms. Climate change may also contribute to the thinning of the ozone layer, as the greenhouse effect leads to cooling of the stratosphere, which increases the release of chlorine into forms that can react with ozone.

Ozone also occurs in the lower atmosphere, or troposphere, where it absorbs infrared radiation emitted by Earth's surface. Pollution from the use of fossil fuels has increased tropospheric ozone levels, contributing to the greenhouse effect. However, its effect is less than that of carbon dioxide or methane.

The National Academy of Scientists and other international groups agree that global warming is occurring. Scientists who disagree cite the discipline of climatology as being too new to be able to deliver accurate data. Others believe some data has been skewed to conform to popular opinion or that data that rejects the notion of global warming has been ignored or underreported.

Nearly all scientists agree that global warming is the result of human activity. Opponents argue that the correlation between higher levels of greenhouse gases and the earth's warming trend do not necessarily mean that greenhouse gases are causing the trend. They see warmer temperatures as part of the normal fluctuations that occur over long periods of time. They also cite the ability of naturally occurring volcanic eruptions to cause temporary changes in weather patterns and levels of gases in the atmosphere.

The body of research on global warming undertaken during the twentieth century has resulted in numerous governmental policies that affect individuals, business, and industry. Environmental regulations and their effect on businesses have increased the controversy surrounding global warming.

Understanding the Discussion

Climatology: Climatology is the scientific study of climate. Climatologists study the weather of a specific region over a given time period. The study of ancient weather conditions is called paleoclimatology. It examines the weather of past millennia by analyzing natural evidence that remains in soil, tree rings, and ice cores. Historical climatology focuses on the weather conditions throughout human history, or, more specifically, the climate of the last few thousand years. A study of the number of hurricanes in a given region over the past one hundred years, for example, would be an example of historical climatology.

Environmental Regulation: State and federal statutes intended to protect the environment, wildlife, and land; prevent pollution and the over-cutting of forests; save endangered species and conserve water; and develop and follow general plans and prevent damaging practices.

Fossil Fuels: Depletable energy sources such as oil, natural gas, and coal, which were formed organically millions of years ago.

Greenhouse Effect: The natural ability of the atmosphere to trap solar energy in amounts that provide temperatures adequate to sustain life. According to data from NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration), the earth's average temperature in 2013 was 58.3 degrees Fahrenheit (14.6 degrees Celsius), which they report was approximately one degree warmer than twentieth-century averages. Increased levels of carbon dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons, methane, and nitrous oxide trap more energy as it radiates from the planet's surface, raising the global temperature of air and ocean water.

Greenhouse Gases (GHGs): With the exception of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are synthetic, greenhouse gases are naturally occurring gases found in the atmosphere that can absorb electromagnetic radiation and, with the exception of ozone, are dispersed throughout the atmosphere. The gases include carbon dioxide, methane, water vapor, ozone, and nitrous oxide.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2): A gas that occurs naturally and is produced by the burning of fossil fuels (most notably in cars and other vehicles) and by deforestation.

Kyoto Protocol: An agreement ratified by over 160 nations that have agreed to reduce carbon dioxide and other emissions. Named for Kyoto, Japan, where the agreement was signed in 1997.

Ozone (O3): A poisonous gas found in the troposphere and stratosphere. It forms a thin layer approximately ten to twenty miles above the earth's surface that helps to block ultraviolet radiation, but also acts as a greenhouse gas at lower levels of the atmosphere.

Ozone-Depleting Substances: Defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as any chemical that breaks down under ultraviolet light and releases chlorine or bromine atoms. These include CFCs, halons, methyl bromide, carbon tetrachloride, and methyl chloroform.

History

The foundation of contemporary research on global warming was established in the nineteenth century. Scientists noted the ability of gases in the atmosphere to create a greenhouse effect and discovered the correlation between the level of carbon dioxide and the earth's temperature. They also noted the increase in carbon dioxide during the Industrial Revolution.

The invention of Freon in the late 1920s played a significant role in the history of global warming. This colorless gas comprised of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) ended up cooling almost every refrigerator manufactured from the 1930s onward and helped spark the air conditioning industry. In the late 1940s, it was found to make an excellent propellant for aerosol cans. Insecticides, hair spray, deodorants, and household cleaners were just some of the widely-used products containing CFCs. However, CFCs were highly reactive with the ozone in the stratosphere as well as being greenhouse gases with the potential to contribute to the greenhouse effect even more than carbon dioxide.

In 1974, Dr. Mario Molina, a researcher in the chemistry department at the University of California, theorized that CFCs were destroying the ozone layer. After several years of additional research by the National Academy of Sciences, the United States banned the use of CFCs in most aerosol cans. In 1987 the United Nations unanimously ratified the Montreal Protocol, an agreement to phase out the use of CFCs, after which levels of CFC use dropped to almost nothing, especially in developed countries. They were mainly replaced by hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which do not react with ozone; however, HFCs are themselves potent greenhouse gases.

Other scientific studies have shown a relationship between the use of fossil fuels and an increase in carbon dioxide. The number of automobiles on the road increased with the post-World War II population boom; in the 1950s most cars were large and inefficient, and leaded gasoline was the norm. However, the smog that hung over cities was attributed mostly to industry. In 1963, the United States passed the first Clean Air Act, which set emissions standards for industry but not for vehicles.

In 1965, geophysicist Roger Revelle of the President's Science Advisory Committee Panel on Environmental Pollution warned of the possibility of global warming from the accumulation of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. During the next few decades, scientists from many disciplines, including biology, physics, meteorology, climatology, chemistry, and geology, contributed research that demonstrated significant changes were taking place and made dire predictions.

In response, the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Program established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 to assess the data and identify options that might slow down or stop global warming. The IPCC became the most influential group on the issue.

In 1970, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) amended the Clean Air Act and set limits for vehicle emissions in response to data that showed vehicles were responsible for roughly 80 percent of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The Clean Air Act was further amended in 1990 to address new environmental concerns such as toxic pollutants and acid deposition.

In 1992, representatives from 170 countries met in Rio de Janeiro at the UN Conference on Environment and Development, commonly referred to as the "Earth Summit." The goal of this meeting was to ensure that all industrial nations shared responsibility for global warming and other environmental issues. The 1992 Earth Summit produced a treaty called the Convention on Biological Diversity that specified conservation strategies, species protection, ecosystem oversight, environmental restoration, and economic incentives for environment-friendly policy and actions. The Convention on Biological Diversity requires each member government to develop a self-implemented strategy and plan of action for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in their country.

Perhaps the most widely known global initiative is the Kyoto Protocol, which the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) took up in 1997. The United States, under the administration of President Bill Clinton, agreed to this treaty and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 7 percent. The US Senate blocked the ratification of the treaty and introduced the Hagel-Byrd Resolution, which stressed the importance of economic priorities and the belief that developing nations, including China and India, should also be required to participate in the Kyoto Protocol, which exempted developing nations because their per-capita emissions levels were considered low. Ultimately, the United States, the world's biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, supported but did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto Protocol resulted in numerous associated environmental gains including the creation of the European Climate Change Program in 2000 and the development of a pro-climate alliance across all decision-making levels of the European Union system.

Environmental regulation focusing on ending global warming has been criticized by business interests for ignoring production processes and for being expensive and excessive. Critics argue that environmental regulation has traditionally focused on "end-of-the pipe" solutions (such as emissions or waste control) rather than addressing the basic processes that created the initial environmental problem.

Global Warming Today

According to the EPA, the global temperature increased between 0.7 and 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit (0.4 to 0.8 degrees Celsius) during the twentieth century. There is speculation that global warming was related to the heat wave in Europe in 2003, which killed more than 25,000 people. Global warming has also been cited as a potential cause or intensifier of severe hurricanes and other strong weather systems throughout the world. The IPCC predicts that in another hundred years, the earth could be 2 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit warmer.

In US politics, Democrats and the Green Party generally support legislation that they believe will curb global warming. This includes tighter emissions caps for industry, more fuel-economy in vehicles, and stronger government sponsorship for research and development of renewable energy sources. Republicans generally tend to oppose these efforts, citing economic concerns that include higher energy costs, a decrease in jobs, and the potential for an economic depression. However, some bipartisan legislation has been passed in the US that aims to improve automobile efficiency.

In 2001, President George W. Bush withdrew the US from the Kyoto Protocol, and instead called for voluntary reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Opponents of the president's actions included the Sierra Club, the World Wildlife Fund, the Union of Concerned Scientists, Greenpeace, and others. Some of these groups joined forces with Massachusetts along with eleven other states and three major US cities in suing the EPA to uphold the federal Clean Air Act and require greenhouse gas emissions to be regulated. A legal opinion issued in 2009 did just that, in what became known as the "endangerment finding."

Upon taking office, US president Barack Obama pledged to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 80 percent by 2050. He also promised to invest billions in the development of new energy sources and energy-saving technologies. However, he was unable to get a cap-and-trade bill through the Senate. By late 2010, President Obama stated that fossil fuel reform and carbon emissions regulations would likely be accomplished through a series of legislative acts as opposed to one large piece of legislation.

In June 2013, President Obama outlined his Climate Action Plan, which was designed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, help sustain forests, encourage alternate forms of energy, and increase studies of actual climate changes. As of 2014, the United States, China, and India stated that they would not ratify any pact that would legally force them to limit the amount of carbon dioxide emissions.

In 2015, Obama announced the Clean Power Plan, which would finally set limitations on carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. The plan established state-by-state targets for emission reductions and was expected to reduce electricity sector emissions by approximately 32 percent by 2030. A Supreme Court injunction in 2016 stayed its implementation, however. The Obama administration also proposed a plan to reduce emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas which often leaks during oil and gas production, by 40 to 45 percent over ten years.

The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Paris, led to the creation of the Paris Agreement, which required each member country to submit a plan for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with progress to be evaluated every five years. Allowing each country to determine its own contribution toward the overall goal led some previously reluctant countries, including the United States, China, and India, to sign the agreement, but some environmentalists criticized the agreement for allowing countries to set their reduction targets too low and for having no enforcement mechanism.

In 2016, at the North American Leaders' Summit (popularly known as the Three Amigos Summit), Presidents Barack Obama of the United States and Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada agreed on a joint environmental action plan, with the goal of deriving 50 percent of their energy from clean power sources by 2025. The agreement also included goals for reducing methane, black carbon, and HFC emissions.

An October 2016 meeting in Rwanda involved almost two hundred member countries of the Montreal Protocol. There an amendment to the protocol was agreed upon that focused on reducing countries' increasingly concerning use of HFCs, largely for refrigeration and air conditioning. Because emissions of HFCs were expected to grow exponentially, especially in developing countries, reducing their use had become a primary goal toward offsetting negative climate change. According to the deal, developed countries would begin reducing HFC emissions by 2019 and developing nations would have until 2024.

Only days earlier, the Paris Agreement had been ratified by the requisite number of countries to become international law. Then, in June 2017, US president Donald Trump announced that he was withdrawing the United States, a process that can only be completed in 2020. Although each country set its own targets and the agreement was nonbinding, Trump claimed that the deal would impose international restrictions on the United States and make its businesses less competitive. He said that the US would attempt to renegotiate the terms. Opponents of the Paris Agreement argued that emerging-market nations, such as China and India, would not have to reduce carbon emissions for another fifteen years and that it was essentially a treaty and had not gone before Congress as the Constitution requires. Proponents of the Paris Agreement feared most that other countries would follow suit. In response to the announcement, however, leaders of other nations renewed their commitment to the deal, and prominent US technology executives and state and local officials pledged their support as well.

During the direction of successive Trump appointees Scott Pruitt and Andrew Wheeler, the EPA moved away from climate change mitigation efforts. In September 2017, Pruitt repealed the Clean Power Plan, arguing that its restrictions on emissions represented federal overreach. The move was seen as a victory for the coal industry, though insufficient to stop coal's decline. But because of the "endangerment finding," a replacement rule must be created at some point. That October, the EPA removed references to and resources about climate change from its active website and prevented three scientists from presenting on climate change at a conference.

A 2018 IPCC report warned that carbon emissions would need to be reduced drastically--by 45 percent within twelve years and down to net zero within thirty-two years, by 2050--in order to prevent the planet from heating another 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100. Partly in response to that report, children and youth around the world, including in the US, led some 1,600 school strikes to lobby their policy makers on March 15, 2019.

Several polls and surveys conducted in 2018 by University of Michigan and Muhlenberg College, Gallup, and the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication all showed most Americans believe the climate is changing and humans have contributed to this. Beliefs about whether climate change is partisan, as well as events in politics such as election campaigns, appear to sway partisan responses on the question of climate change, particularly among conservatives. The Yale survey found that Republicans were more likely to accept the findings of climate science when it was not making news headlines and if they lived in coastal areas, perhaps because of localized storm and other effects. Such swings in views may come into play during the 2020 presidential campaign, as a number of Democratic candidates began including climate policy into their platforms in early 2019 and the Green New Deal resolution proposed by Democratic lawmakers Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey highlighted younger and centrist voters' concerns over the issue.

These essays and any opinions, information or representations contained therein are the creation of the particular author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of EBSCO Information Services.

Bibliography

Books

Flannery, Tim F. The Weather Makers: How Man Is Changing the Climate and What It Means for Life on Earth. New York: Atlantic Monthly, 2005. Print.

Gore, Al. An Inconvenient Truth: The Crisis of Global Warming. New York: Viking Juvenile, 2007. Print.

Maslin, Mark. Global Warming: A Very Short Introduction. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2014. Print.

McCaffrey, Paul. Global Climate Change. New York: Wilson, 2006. Print.

Richter, Burton. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Climate Change and Energy in the 21st Century. New York: Cambridge UP, 2014. Print.

Periodicals

Fowler, Thomas B. "The Global Warming Conundrum." Modern Age 54.1-4 (2012): 40-62. Print.

Friedman, Lisa. "In a Switch, Some Republicans Start Citing Climate Change as Driving Their Policies." The New York Times, 30 Apr. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/04/30/climate/republicans-climate-change-policies.html. Accessed 30 Apr. 2019.

Friedman, Lisa, and Brad Plumer. "E.P.A. Announces Repeal of Major Obama-Era Carbon Emissions Rule." The New York Times, 9 Oct. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/10/09/climate/clean-power-plan.html. Accessed 31 Oct. 2017.

Goodkind, Nicole. "Climate Change Carnival Barkers." Newsweek Global, vol. 171, no. 11, Oct. 2018, p. 30. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=132008645&site=pov-live. Accessed 30 Apr. 2019.

Harvey, Fiona. "Paris Climate Change Agreement: The World's Greatest Diplomatic Success." Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 14 Dec. 2015. Web. 14 Sept. 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/13/paris-climate-deal-cop-diplomacy-developing-united-nations

Jennings, Lane. "No Single Way to Cut Greenhouse Gas Emissions." Futurist 42.3 (2008): 14-15. Print.

Mooney, Chris. "What You Need to Know about Obama's Biggest Global Warming Move Yet--The Clean Power Plan." Washington Post. Washington Post, 1 Aug. 2015. Web. 9 Nov. 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2015/08/01/what-you-need-to-know-about-obamas-biggest-global-warming-move-yet-the-clean-power-plan/.

Neuhauser, Alan. "Political Winds, Not Science, Sway Conservative Republicans on Climate Change." U.S. News - The Report, May 2018, p. C19. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=129580576&site=pov-live. Accessed 30 Apr. 2019.

"Out of Paris." National Review, vol. 69, no. 12, June 2017, p. 12. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=123576485&site=pov-live. Accessed 31 Oct. 2017.

Websites

Beaton, Will. "Greenhouse Gases: What Every College Student Should Know." Dakota Student. U of North Dakota, 21 Dec. 2014. Web. 30 Dec. 2014.

"The Clean Power Plan: A Climate Game Changer." Union of Concerned Scientists. Union of Concerned Scientists, 2015. Web. 9 Nov. 2015. http://www.ucsusa.org/our-work/global-warming/reduce-emissions/what-is-the-clean-power-plan#.VkCsC7erRpg.

"Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change." United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 4 Oct. 2006. Web. 9 Nov. 2015. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.html.

Smith-Spark, Laura. "Nations Agree Landmark Deal to Cut HFCs, Potent Greenhouse Gases." CNN, 15 Oct. 2016, www.cnn.com/2016/10/15/africa/montreal-climate-change-hfc-kigali. Accessed 4 Jan. 2017.

~~~~~~~~

By Sally Flynn Driscoll

Dr. Flynn earned a PhD in Cultural Anthropology from Yale University in 2003. She is a researcher, writer, and teacher based in Amherst, MA.

Copyright of Points of View: Global Warming is the property of Great Neck Publishing and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Title: Think Again: Climate Treaties. By: Shorr, David, Foreign Policy, 00157228, Mar/Apr2014, Issue 205

Database: Points of View Reference Center

Think Again: Climate Treaties

Why the glacial pace of climate diplomacy isn't ruining the planet "An Ironclad Treaty Is the Only Way to Save the Planet."

DON'T COUNT ON IT.

Time is running short for the international community to tackle climate change.

Pressure to act comes from rising temperatures and sea levels, superstorms, brutal droughts, and diminishing food crops. It also comes from fears that these problems are going to get worse. Modern economies have already boosted the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere by 40 percent since the Industrial Revolution. If the world stays on its current course, CO2 levels could double by century's end, potentially raising global temperatures several more degrees. (The last time the planet's CO2 levels were so high was 15 million years ago, when temperatures were 5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit higher than they are today.)

Another source of pressure, however, is self-imposed. Under the auspices of the United Nations, the next global climate treaty -- to be negotiated among some 200 countries, with the central goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions -- should be enacted in 2015, to replace the now-outmoded 1997 Kyoto Protocol. (Once passed by state parties, the new treaty would actually go into effect in 2020.)

The race against both nature and the diplomatic clock is stressful. But in the rush to do something, the international community -- most notably, and ironically, those individuals and organizations most fervent about combating global warming -- is often doing the wrong thing. It has become fixated on the notion of consensus codified in international law.

The U.N. process for climate diplomacy has been in place for more than two decades, punctuated since 1995 by annual meetings at which countries assess global progress in protecting the environment and negotiate treaties and other agreements to keep the ball rolling. Kyoto was finalized at the third such conference. A milestone, it established targets for country-based emissions cuts. Its signal failure, however, was leaving the world's three largest emitters of greenhouse gases unconstrained, two of them by design. Kyoto gave developing countries, including China and India, a blanket exemption from cutting emissions. Meanwhile, the United States bristled at its obligations -- particularly in light of the free pass given to China and India -- and refused to ratify the treaty.

Still, Kyoto was lauded by many because it was a legally binding accord, a high bar to clear in international diplomacy. The agreement's provisions were compulsory for countries that ratified it; violating them would invite a stigma -- a reputation for weaseling out of promises deemed essential to saving the planet.

Today, the principle of "if you sign it, you stick to it" continues to guide a lot of conventional thinking about climate diplomacy, particularly among the political left and international NGOs, which have been driving forces of U.N. climate negotiations, and among leaders of developing countries that are not yet major polluters but are profoundly affected by global warming. For instance, in the lead-up to the last annual U.N. climate conference -- held in Warsaw, Poland, in November 2013 -- Oxfam International's executive director, Winnie Byanyima, said the world should not accept a successor agreement to Kyoto that has anything less than the force of international law: "Of course not. If it's not legally binding, then what is it?" Ultimately, Byanyima and other civil society leaders walked out of the conference to protest what they viewed as a failure to take steps toward a new, ironclad treaty.

The frustration in Warsaw showed an ongoing failure among many staunch advocates of climate diplomacy to learn the key lesson of Kyoto: Legal force is the wrong litmus test for judging an international framework. Idealized multilateralism has become a trap. It only leads to countries agreeing to the lowest common denominator -- or balking altogether.

Evidence shows that a drive for the tightest possible treaty obligations has the perverse effect of provoking resistance. In a seminal 2011 study of climate diplomacy, David Victor of the University of California, San Diego, concluded, "The very attributes that made targets and timetables so attractive to environmentalists -- that they set clear, binding goals without much attention to cost -- made the Kyoto treaty brittle because countries that discovered they could not honor their commitments had few options but to exit."

This argument may sound like one made by many political conservatives, who opposed Kyoto and have long been wary of treaties in general. But the point is not that international efforts are useless. It is that global agreements are most useful when they include a healthy measure of realism in the demands that they make of countries. Instead of insisting on a binding agreement, diplomats must identify what governments and other actors, like the private sector, are willing to do to combat global warming and develop mechanisms to choreograph, incentivize, and monitor them as they do it. Otherwise, U.N. talks will remain a dialogue of the deaf, as the Earth keeps cooking.

"The Biggest Problem Is That Leaders Lack the Political Will to Craft a Treaty."

NOT EXACTLY.

To explain multilateralism's recent failures, from the Kyoto Protocol to the Warsaw conference, its most fervent advocates often take aim at the same purported stumbling block: the spinelessness of politicians. Fainthearted presidents and prime ministers shy away from commitments to protect the planet because it is more politically expedient to focus on economic growth, no matter the environmental consequences.

Thanks to this conventional wisdom, "political will" has become a loaded term. If a leader doesn't sign on to a tough, legally binding treaty, he or she must be morally bankrupt. Mary Robinson, a former president of Ireland who now runs a foundation dedicated to climate change issues, has called the "legal character" of climate agreements "an expression of or an extension of political will." Meanwhile, Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace International, has written that he hopes governments will "find the political will to act beyond short-sighted electoral cycles and the corrupting influence of some business elites."

The fallacy of the political will argument, however, is that it assumes everyone already agrees on the steps necessary to address climate change and that the only remaining task is follow-through. It is true that the weight of scientific evidence tells us humanity can only spew so many more gigatons of CO2 into the air before subjecting the planet and its inhabitants to dire consequences. But the only guidance this gives policymakers is that they must transition to low-carbon economies, stat. It does not tell them how they should do this or how they can do it most efficiently, with the least cost incurred. As a result, advocates of strict climate treaties hammer home the imperative for environmental action without providing for discussion about how countries can actually transform their economies in practice.

Consider environmental author and activist Bill McKibben's comments in early 2013 praising Germany for using more renewable energy: "There were days last summer when Germany generated more than half the power it used from solar panels within its borders. What does that tell you about the relative role of technological prowess and political will in solving this?"

Unfortunately, it tells us very little. It doesn't tell us what it would take to stretch the reliance on solar energy beyond some sunny German days or the subsidy levels required to make solar power a more widely used energy source. It also tells us nothing about how we could translate Germany's accomplishments to countries with very different political and economic circumstances. And it doesn't explain what would induce those diverse countries to accept a multilateral arrangement boosting the global use of renewable energy. All McKibben's factoid tells us is that the myth of political will is quite powerful.

Certainly, economic imperatives should not override environmental ones. Yet the standard for climate diplomacy should not be broad appeals for boldness that ask policymakers to deny trade-offs rather than wrestle with them -- particularly in the countries that the world needs most in the fight against global warming.

"China and India Are Ruining Our Chances to Avert Global Catastrophe."

ACTUALLY, THEY'RE HELPING.

Last fall, after the Warsaw meeting, many experts and pundits were quick to place blame for the gathering's tumult. "The India Problem: Why is it thwarting every international climate agreement?" a headline on Slate demanded. Other observers scorned India and China for saying they would not make "commitments" to greenhouse gas cuts in the 2015 climate agreement. (The meeting's attendees ultimately settled on the word "contributions.")

These complaints, however, are increasingly out of date.

It's true that, throughout most of the 2000s, China and India clung to the exemption that the Kyoto Protocol had granted them, arguing that the industrialized world had caused global warming and that developing countries shouldn't be deprived of their own chance to prosper. This has induced great anxiety because, since 2005, China's annual share of CO2 emissions has grown from around 16 percent to more than 25 percent, while India has emerged as the world's third-largest carbon emitter. In short, without China and India, progress on climate change will be virtually impossible.

By 2010, however, Beijing and New Delhi had begun to change their stance. A desire to save face diplomatically, combined with increasing pollution at home and domestic need for energy efficiency, have made China and India more willing to cut emissions than ever before.

Chinese leaders in particular are eager to recast their country as an environmental paragon, rather than a pariah. Some analysts attribute this shift to China's aspirations to global prominence. Playing off the popular idea of the "Chinese century," Robert Stavins, director of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, has said, "If it's your century, you don't obstruct -- you lead." Recently, China has taken significant steps forward with green energy, mimicking many of the regulations and mandates that have helped the United States achieve environmental progress. Wind, solar, and hydroelectric power now provide one-quarter of China's electricity-generating capacity. More energy is being added to China's grid each year from clean sources than from fossil fuels. And in a show of its willingness to step up to the diplomatic plate, China signed an accord with the United States in 2013 that scales down emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, which are so-called super-greenhouse gases.

Yet these changes have not substantially bent the curve of China's total emissions. According to Chris Nielsen and Mun Ho of Harvard University's China Project, this is largely because the country's rapid economic growth makes the tools that have slowed emissions in other economies less effective in China: "[T]he unprecedented pace of China's economic transformation makes improving China's air quality a moving target." Ultimately, Nielsen and Ho argue, the only way for China to rein in emissions will be to attach a price to carbon, through either a tax or a cap-and-trade system. As if on cue, China is now setting up municipal and provincial markets in which polluters can trade emissions credits, with the goal of creating a national market by 2016.

The point here is that the leaders of countries with rapidly developing economies cannot predict environmental payoffs with any real confidence. Tools that work well for others may not for them. That's why China and India are hesitant to sign legally binding treaties, which would put them on the hook to hit targets that could prove much harder to reach than anticipated. They don't want to undertake costly reforms that might not have the predicted benefits, and they do not want to risk the hefty criticism that failure to abide by a treaty would surely bring.

Chinese and Indian leaders realize they'll be judged by their contributions to a cleaner environment, and they embrace the challenge. (Recently in India, more than 20 major industry players launched an initiative to cut emissions.) And they are apt to be less guarded on the international stage if a new climate agreement functions as a measuring stick, not a bludgeon -- much like the 2009 Copenhagen accord has done.

"But Copenhagen Was a Catastrophe."

NOT AT ALL.

In December 2009, the U.N.'s annual climate conference, hosted in Copenhagen, produced an agreement that is still roundly condemned by environmentalists, the leaders of developing countries, and political liberals alike. Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the agreement let countries voluntarily set their own targets for emissions cuts over 10 years. "The city of Copenhagen is a crime scene tonight," the executive director of Greenpeace U.K. declared when the deal was reached. Lumumba Di-Aping, the chief negotiator for a group of developing countries known as the G-77, which had wanted major polluters like the United States to take greater responsibility for global warming, said the agreement had "the lowest level of ambition you can imagine."

In reality, however, the conference wasn't a fiasco. It offered the basis for a promising, more flexible regime for climate action that could be a model for the 2015 agreement.

The Copenhagen agreement had a number of advantages. It didn't have to be ratified by governments, which can delay implementation by years. Moreover, in an important new benchmark for climate negotiations, the agreement set the goal of preventing a global average temperature rise of more than 2 degrees Celsius, with all countries' emission cuts to be gauged against that objective. This provision went to the heart of climate diplomacy's collective-action problem: Apportioning responsibility for cutting emissions among countries is always tricky, but the 2-degree target creates a shared definition of success.

Most importantly, however, the shift to voluntary pledges showed the first glimmers of lessons learned from the most common mistakes of climate negotiations. In the U.N. process, countries usually operate by consensus: They must all agree on each other's respective climate goals, a surefire recipe for dysfunction. (In 2010, the chair of annual climate talks refused to let a single delegation -- Bolivia -- block consensus, which counts as a daring move at U.N. conferences.)

Under Copenhagen, by contrast, countries can pledge to do their share while remaining within their comfort zones as dictated by circumstances back home. For instance, faced with economic imperatives to continue delivering high growth, China and India pledged at Copenhagen to reach targets pegged relative to carbon intensity (emissions per unit of economic output) rather than absolute levels of greenhouse gases. This was as far as they were willing to go -- but it was further than they'd ever gone before.

Admittedly, the Copenhagen conference wasn't perfect. The deal was struck on the conference's tail end, after U.S. President Barack Obama barged in on a meeting already under way among the leaders of China, India, Brazil, and South Africa. Many of the other delegates registered outrage that the five leaders had negotiated a deal in private by having the conference merely "take note" of the accord.

But the following year's U.N. conference fleshed out the Copenhagen framework, and it has since gained enough legitimacy that 114 countries have agreed to the accord and another 27 have expressed their intention to agree. Taken together, this includes the world's 17 largest emitters, responsible for 80 percent of carbon-based pollution.

The Copenhagen accord will expire as the Kyoto successor agreement takes effect in 2020. But it shouldn't be viewed as just a stopgap. In giving governments more flexibility, Copenhagen offers the chance to build more confidence -- and ambition -- where historically there has only been uncertainty and rancor. Any future climate agreement should do the same.

"Countries Will Never Keep Mere Promises to Cut Emissions."

NEVER SAY NEVER.

The most obvious criticism of Copenhagen's system, of course, is that, while it is nice for countries to set voluntary goals, they will never meet them unless they are legally compelled to do so. That is why, just after the Copenhagen deal was reached, then-British Prime Minister Gordon Brown hastily said, "I know what we really need is a legally binding treaty as quickly as possible."

To date, there has been progress on meeting targets set under Copenhagen. The United States and the European Union, for instance, are all within reach of meeting their 10-year goals, perhaps even ahead of schedule. Meanwhile, China's pledge to cut carbon intensity, based on 2005 levels, has become the framework for the country's new emissions-trading markets.

But the most important reason to have confidence in the Copenhagen deal lies in its provisions for measurement, reporting, and verification. If done right, these so-called MRV mechanisms will alert the world as to how countries are (or are not) reducing greenhouse gases, while also pushing states to keep pace toward pledged cuts.

MRVs rely on peer pressure. Countries report to and monitor one another, tracking and urging progress. This kind of system has already proved effective in a variety of international policy areas. For instance, the Mutual Assessment Process of the G-20 and International Monetary Fund brings together the major economic powers to discuss whether their respective policies are helping to maximize global economic growth or are instead widening imbalances between export- and consumer-based economies. The process is fairly new, but already, it is widely credited with prodding China -- long reluctant to discuss these issues in multilateral forums (sound familiar?) -- to let its currency appreciate and to make boosting domestic consumption a main plank of its five-year (2011-2015) plan.

MRVs have also proved valuable in narrower climate regimes, such as the European Union's cap-and-trade mechanism. As a 2012 Environmental Defense Fund report explained, "[B]ecause EU governments based the system's initial caps and emissions allowance allocation on estimates of regulated entities' emissions governments issued too many emissions allowances ('over-allocation'). Now, however, caps are established on the basis of measured and verified past emissions and best-practices benchmarks, so over-allocation is less of a problem." In other words, MRVs have helped the European Union tighten market standards, correcting an earlier miscalculation and actually heightening the system's ambition.

The Copenhagen agreement enhanced the utility of global, climate-related MRVs by requiring greater transparency from developing countries. Under Kyoto, these countries were only required to provide a summary of their emissions for two years: a choice of either 1990 or 1994, and 2000. Copenhagen, by contrast, committed developing countries to report on their emissions biennially -- the first reports are due in December -- narrowing the gap with the requirement for annual reports that Kyoto imposed on developed countries.

Copenhagen's MRVs are not yet as strong as they could be. For instance, they should require annual reports from all countries, no matter their stages of development. These reports should also include a breakdown of information according to economic subsectors and different greenhouse gases, along with supporting details about data-collection methods. In addition, the process of reviewing reports needs to be fleshed out, taking cues from other strong MRVs that already exist, and wealthier countries should help underwrite the cost to developing countries of preparing comprehensive reports.

The good news is that, given the ongoing nature of U.N. climate diplomacy, it's still possible to strengthen Copenhagen's MRVs. Important new principles and guidelines for peer review have been established in negotiations since 2009, and those involved in climate diplomacy should now buckle down to finish the job. Robust MRVs would guarantee that the world makes the most of the next few years and draws on that experience to chart a new phase of climate action anchored in a 2015 agreement.

"Forget Treaties. Solutions Will Come From the Bottom Up."

DON'T GET CARRIED AWAY.

Some critics of the U.N. process, hailing from conservative political ranks, the private sector, and other areas, have lost all patience and think that a top-down process, particularly one negotiated in an international forum, is the wrong way to go. They point out that, while national leaders negotiated the Copenhagen deal, actual progress toward its goals is being cobbled together by actors at lower levels -- in cities, states, markets, and industries. They are choosing which energy will generate electricity, honing farming practices, improving industrial efficiency, and the like.

Indeed, some policymakers and climate analysts point to the influence of local authorities as a game-changer for climate action. After all, Chinese cities and provinces have begun building emissions-trading markets, and California has passed a law establishing one of the most robust such markets in the world. Meanwhile, leaders of the world's megacities have banded together to cut emissions in what's known as the C40 group, established in 2005. As C40 chair and Rio de Janeiro Mayor Eduardo Paes has put it, "C40's networks and efforts on measurement and reporting are accelerating city-led action at a transformative scale around the world."

Given this sort of local progress, it is certainly worth asking whether diplomats and national policymakers should just get out of the way. Maybe a thoroughly bottom-up approach would be better for the planet than an international climate regime, no matter how flexible. David Hodgkinson, a law professor and executive director of the nonprofit EcoCarbon, which focuses on market solutions for reducing emissions, has argued that such an approach has "more substance" and "probably holds out more hope than a top-down UN deal."

Ultimately, however, this view is misguided. There is no substitute for high-level diplomacy in getting everyone to do their utmost and in keeping track of their efforts. In particular, as Copenhagen reminded the world, the value of the agenda setting, peer pressure, and leverage unique to international diplomacy shouldn't be overlooked. Moreover, we've seen in other policy spheres how the international community can first establish fundamental principles, which then sharpen over time with the aid of global coordinating bodies and more localized initiatives. For instance, the nonbinding 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights established a framework for a host of subsequent international treaties, U.N. agencies, regional charters and courts, national policies, and, more recently, corporate responsibility efforts.

Practically speaking, it would also be shortsighted to rely on an assortment of subnational actors to tackle a global problem like climate change. Determining how the work of these actors intersects, what it adds up to, and who monitors that sum are critical matters best managed from the top-down. As the goal of preventing a global average temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius reminds us, it is the aggregate of countries' reduced emissions that will be the ultimate test of success.

Even so, the status quo of climate talks, focused on badgering countries to join another legally binding treaty, represents diplomatic overreach. This hasn't worked in the past, and it won't in the future. The international community should give up the quest to sign a legally binding treaty in 2015. Stop fretting about political will and acknowledge the various pressures different countries face. Focus on fully implementing Copenhagen's pledge-and-review system and use that as a model for the successor to Kyoto. Then, allow that new pact to be what steers action and innovation.

Interest in this approach is slowly mounting, including in the U.S. government. Todd Stern, the State Department's special envoy for climate change, said in a 2013 speech, "An agreement that is animated by the progressive development of norms and expectations rather than by the hard edge of law, compliance, and penalty has a much better chance of working." Still, there's a long way to go before the all-or-nothing attitude that has dominated climate diplomacy for so long disappears for good.

In the meantime, the environmental clock keeps ticking.

PHOTO (COLOR): Illustration by Maayan Pearl; photo by Joel Simon/Getty Images

PHOTO (COLOR): Pedro PARDO/AFP/Getty Images

PHOTO (COLOR): FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP/Getty Images

PHOTO (COLOR): ATTILA KISBENEDEK/AFP/Getty Images

PHOTO (COLOR): JANEK SKARZYNSKI/AFP/Getty Images

PHOTO (COLOR): JANEK SKARZYNSKI/AFP/Getty Images

~~~~~~~~

By David Shorr

David Shorr has been analyzing multilateral affairs for over 25 years. He has worked with a range of international organizations and participates in Think20, a global meeting of leading think-tank representatives

Copyright of Foreign Policy is the property of Foreign Policy and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.