Review the information presented in the "General Motor’s Order to Delivery Initiative: A Case Study." Write 500-750 words addressing the following questions. You are not required to answer these quest

General Motor’s Order-to-Delivery Initiative

A Case Study

Background:

Two years after taking on a challenging job as Director of Business Processes in Advance purchasing, Dick Alagna lay back on his chair thinking about what had transpired between him and Harold Kutner –Group Vice-President of WWP. Dick had been nominated to lead the cluster called “Sourcing and Supplier Management” in one of the biggest initiatives of GM “Order to Delivery (OTD)”. This new initiative would radically re-define the business processes at GM. In a presentation, Kutner had challenged Alagna to develop a supply base that “can transform end customers’ clicks on GM’s Buyer Power website into technology and demand requirements that are ‘sensed’ by suppliers throughout GM’s supply chain via Supplier Power and TradeXchange.”

The cross-functional OTD team consisting of some 50 people representing seven clusters had been put together to take the automotive giant’s OTD initiative forward.

OTD as defined by GM as:

“The engine that will deliver the promise of e-business to our customers and shareholders by:

Helping to transform GM from a traditional make and sell company (push) to a dynamic sense and respond company (pull)

Integrating and streamlining the entire supply chain (supply, manufacturing and distribution)

Enabling GM to meet dealer and customer requirements rapidly and reliably”

The biggest challenge of the OTD initiative was to be able to deliver customized vehicles to customers within five days of ordering them from the GM Buyer Power website. This was going to prove to be a daunting task, as GM’s order delivery leadtimes have historically been in the 12 to 16 week timeframe. Dick had been assigned responsibility for the supply part of the initiative. Although this was an exciting project, Dick also realized he had a tough job ahead of him. The problem was complex, he thought. “How do I get 12000 suppliers together to share their ideas?” Dick realized that the first step involved establishing a dialogue with suppliers, find out the problems they faced with the OTD initiative, and then recommend solutions so as to improve the supply chain reliability and responsiveness and align it with OTD’s vision of “sense and respond”.

It was 4p.m on a cold winter evening and as Dick looked out of his window, it was still snowing. The office building was silent, as most employees had left early due to a snow storm warning. Dick rested his face on his palms and thought to himself, “Where do I start? Will I get cooperation from the suppliers? Can I complete my task in a time frame of 3 years (2003)?”

He was known in GM as a go-getter, the new assignment was a challenge and he had to find the answers.

GM HISTORYGeneral Motors was founded in 1908 and is now the largest company in the world, having 377,000 employees worldwide. GM revenue in fiscal year 1999 were $176.6 billion, an increase of 13.6% over 1998. Its net income was $5.6 billion. GM has a presence in 200 countries, operations in 50 countries, 70 assembly plants, and produces 8.1 million vehicles every year. It’ dealer network spans 8,118 dealerships worldwide. GM has its headquarters in Detroit, MI. It owns the Buick, Oldsmobile, Chevrolet, GMC, Cadillac, Pontiac, and Saturn brands. It has also developed a unified web of strategic alliances with a number of global automotive manufacturers, including Fiat, Opel, Isuzu, Subaru, and Saab.

GM produces 80 different models of cars and trucks, which far outnumbers its nearest rival Ford that produces 40 models. Although the largest company in the world (Fortune 1 ), its market share has shrunk in the last two decades. GM’s current market share is 29%, down from 34% in 1995. Apart from being in the automotive industry, GM has interests in digital communications, financial and insurance services, locomotives, and heavy duty automotive transmissions.

GM VISION: Be the world leader in transportation products and related services. We will earn our customers’ enthusiasm through continuous improvement driven by the integrity, teamwork, and innovation of GM people.

CORE VALUES: Customer enthusiasm, Continuous improvement, Innovation, Integrity, and Teamwork.

GM’s transition to a web based companyGeneral Motors (GM) has often been “dragged through the mud” as an example of an organization with archaic management structures, arms-length supplier and dealer relationships, and dysfunctional processes. GM’s loss of market share (now at 30%) has also not helped its image. There is no question that GM has had its share of problems, and has even been the object of derision in films such as “Roger and Me”. However, relatively few people have noticed the quiet accomplishments made by General Motors in becoming global e-business supply chain leader. GM has made a commitment to web-centrism, and in the last five years, has undergone a radical change in its global management structure. While many companies have initiated Web-based strategies, GM has also created a three-pronged strategy to support its intention of doing business entirely via the Web. This strategy involves using the Web to drive, buy, and build innovative new vehicles in ways never imagined. A solid global supply chain structure is already in place to ensure that this new three-pronged strategy is realized.

Led by its recent CEO, Richard Wagoner, GM has made a commitment to become a web-centric organization, and in the last five years, has undergone a radical change throughout its management structure. These changes in fact date back to the early 1990’s, when GM was on the verge of bankruptcy. After the board replaced the infamous CEO Roger Smith with the short tenure of Robert Stempel, a new leader, Jack Smith, was appointed to lead the company from its now beleaguered stage. At that time (1991), Jack Smith recognized that GM was in a crisis situation. During that period, there was a point at which GM was literally two weeks away from bankruptcy. That such a powerful and large organization could be brought to the brink of collapse was a lesson in the dangers of promoting financial measures at the expense of customer satisfaction that few GM managers are likely to forget.

Smith quickly realized that from an economic standpoint, 70% of GM’s expenses were in the area of purchased goods, logistics, and services. If GM was to continue to exist, purchasing cost savings would be a primary means of survival. A new purchasing leader, Jose Ignacio Lopez was appointed. Lopez had come from GM’s European division, and had been successful in achieving a turnaround in this segment of GM’s operations. Upon arriving in North America, Lopez initiated a series of significant cost savings throughout its supply base, which helped to keep GM alive for a few more years. By creating an internal culture focused on driving improved internal integration between purchasing, engineering, logistics, and operations, Lopez turned around a company that was literally on the verge of bankruptcy. During his brief two-year tenure at the head of GM’s purchasing organization, he established a different mindset and raised the importance of purchasing and supply chain management as a core contributor to GM’s competitive success. Although Lopez’s stay was only two years, he had a profound impact on the organization. In restoring GM’s financial health, Lopez also instigated a re-engineering of GM’s entire worldwide operations that is continuing a decade later.

In the last eight years, the company has undergone a metamorphosis, with the initiation of its World Wide Purchasing strategy. WWP provides a means for integrating GM’s product design, sourcing, logistics, and supply chain strategies. GM is now recognized as a leader in global markets that have been overlooked by many other companies, including China, South America, and Eastern Europe. Harold Kutner, Executive VP of WWP and Logistics, has also initiated a bold new Business to Business e-commerce strategy, by joining with DaimlerChrysler and Ford to create the world’s largest B2B e-commerce site (estimated at $400 billion per year). On the customer end, GM is also making radical changes to create a customer web-based sales strategy via its BuyPower site, and is investigating ways to cut its order to delivery lead-times to five days, allowing customers to order customized products directly from the web, (Dell-style!) It is also integrating new and innovative technologies into its future products, including such innovations as On-star, providing in-car web surfing, voice activation, and global positioning systems.

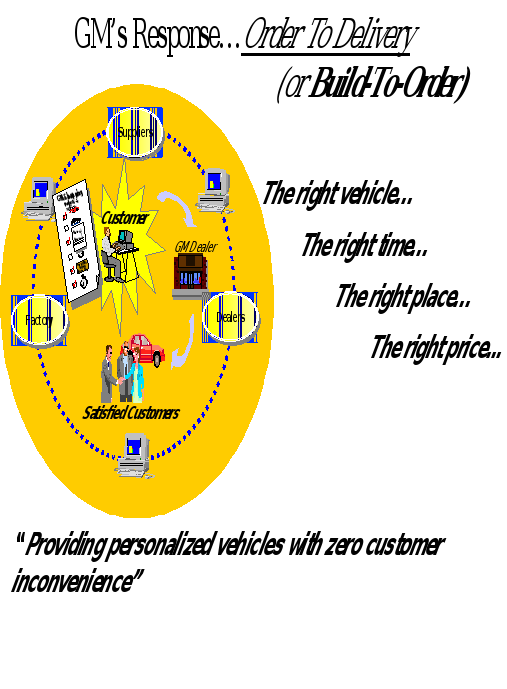

Spurred by the recent growth in on-line business, GM is moving towards a customer-centric organizations, where companies must take their goods and services to the customer in the 24 by 7 world (see Figure 1). Estimates are the e-commerce revenues will reach $1.3 trillion by 2003. The number of Internet users in 1999 was 132 million, and is projected to reach 320 million by 2003. Projections are that 50% of customers will buy vehicles by shopping the web (at least for information on options, pricing, etc.) Because customers will truly be in control of what they buy, GM must provide the right vehicles at the right time, place, and price for customers. This will help suppliers to focus on core technology roadmaps, as well as understand option penetration and associated capacity requirements.

To support its e-business strategy, GM has set-up its web site e.gm.com, SupplyPower portal (GM’s B2B supplier network- communication with the suppliers), BuyPower portal(GM’s customer interface), and TradeXchange ( on-line auction house- to get quotes from supplier, usually on commodity items).

What is GM SupplyPower?

As shown in Figure 2, GM SupplyPower is General Motors’ supplier communication Web site. It is used as a medium for GM to provide up-to-date information to the supplier community quickly, efficiently, and conveniently. Supply power also acts as a gateway to applications that are developed and implemented by groups within GM. Supply Power is for use for the employees at GM’s business partners (suppliers, design organizations, logistics providers, etc.) and GM’s allied divisions.

It has six functional powers under it. They are:

PurchasePower: To receive bid packages, submit quotes, and receive purchase contracts.

QualityPower: To share quality and warranty information, share supplier performance metrics, and participate in a Supplier Suggestion Program.

EngineeringPower: To collaborate on vehicle design by sharing math data, receive vehicle program information, and collaborate on testing.

FinancePower: Query invoice payment status and share information on new vehicle sales and trade discounts programs.

MaterialPower: Collaborate on production capacity planning, production schedules and share logistics information.

ManufacturingPower: Collaborate on manufacturing, share inventory and production information.

What is GM Buy Power?

GM Buy Power is GM’s web based customer interface. Customers can go to this site and configure their GM cars/trucks/SUV, get price quotes, apply for a loan, and be directed to the nearest GM dealer.

What is the TradeXchange?

It is GM’s web based auction house. The suppliers are notified of the time of opening and closing of the bid time and they are required to quote in the specified time. In this manner GM is able to reach out to more suppliers and get quotes at the lowest cost to GM.

Only pre-selected/ pre-qualified are allowed to quote on the TradeXchange. Parts that are put up for quotes are usually one-all/commodity type components that go in all cars in a particular plant irrespective of the customization done by the customers.

Order to Delivery (OTD) InitiativeThe order to delivery process involves all of the activities that occur from the time a customer orders a vehicle through its delivery to that customer. At GM, a customer ordering a customized vehicle today may have to wait up to 70 days to take possession. Traditionally the auto-makers have had their plants produce to capacity and vehicles are pushed on the market rather than pulled by true customer demand leading to long lead times and poor delivery reliability. The ultimate results are higher costs and lower customer satisfaction.

Technology and Internet are changing the automotive industry including the way products and services are marketed. Customers have become more demanding and no longer can GM mass market its vehicles and keep them happy. The customers need instant gratification and that boils down to rapid delivery time of vehicles. GM wants to make buying a GM car an excellent experience. Imagine being able to log on to the Internet, find the vehicle you want, color and financing. Then, the vehicle is delivered where you want it and when you want it.

GM launched the OTD initiative to go head on into the challenge. A sense and respond business environment focussed on the customer and led by Harold Kutner, group vice president, Worldwide purchasing and North American Production Control & Logistics.

To carry this initiative forward the OTD team was formulated with representations from all four global regions and over thirty business functions within GM. GM is working with Deloitte Consulting to move the OTD initiative forward. “Our vision is to deliver personalized vehicles with zero inconvenience,” says Kutner.

GM will align its OTD vision with its other key initiatives in the company, such as

e-GM, the GM SupplyPower, and GM BuyPower. OTD will encompass and affect every function within the enterprise. The bottom line for OTD is to deliver “The right vehicle, the right time, the right place, and the right price i.e. Vehicles …delivered Fast and Reliably. This is viewed as the only way to improve customer satisfaction, enthusiasm, and loyalty.

Why is OTD critical for GM?

GM’s current OTD Capability is yielding unsatisfactory performance. Its market share continues to erode down from 34% in 1995 to 29% in 2000 (based on May’2000 data).

The inventory at the suppliers and at the dealer lot is phenomenal. GM’s supply chain is bloated with over $40 billion worth of inventory, mainly because of in-effective/ not so transparent communication and also due to lack of real time information sharing between GM and its tiered suppliers. Lack of transparency and lack of real time information sharing are a few reasons that explain the large amount of inventory that GM holds. A phenomenon called the “bullwhip effect” is prevails within its supply chain. This means that as one goes back through multiple tiers of suppliers that provide materials and components to GM, the level of inventory increases exponentially the further one goes back. The root cause for this bullwhip effect is the inability of entities in the supply chain to sense demand properly; the gap between supply and demand is thus buffered with inventory. This causes last minute production schedules changes and adds a lot of variability in the system. Rippling effect can be seen down to the suppliers who in order to be responsive, responds to the variability by holding inventory. At the other end, dealers also hold a lot of inventory in order not to turn away any customers. There are times when due to production schedule changes, the suppliers are not holding the right inventory required. Suppliers become less responsive, requiring long lead times to deliver the required part thus increasing the OTD time. There is also a possibility that the inventory they are holding becomes obsolete, which drives cost into the system. GM is losing customers due to long OTD times, who are unwilling to wait and hence go elsewhere.

This situation has caused no end of conflicts within GM’s supply chain. Both suppliers and dealers are critical of GM’s role in the OEM-Supplier/Customer relationship. Further, traditional competition is moving fast and new competitive models are emerging. GM’s rival Ford Motor Co., is attacking the same challenge and appears to be neck and neck in the race to wire its operations to the Internet and is taking aggressive actions to improve its OTD capability as well. This has increased the urgency with which the OTD team has been tasked to wire its operations for real times information sharing. GM believes that OTD is the engine that will deliver the promise of e-business to its customers and shareholders and is a critical link to its e-business strategy. Analysts forecast that, by 2003, the Internet will influence roughly 8 million new car purchases, half a million of which is expected to occur over the net. GM says that the competition is fierce, but it is prepared to win.

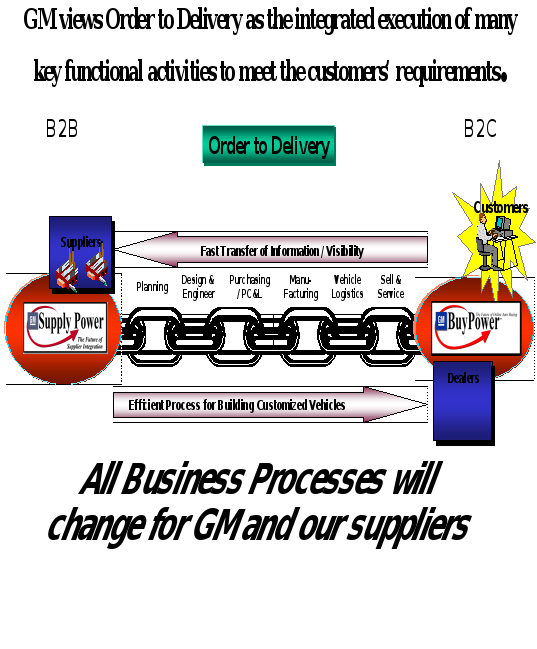

The Strategic Roadmap for World Wide PurchasingIf the Order to Delivery initiative is to become the core enabler for GM’s web-based strategy of linking customers, dealers, plants, and suppliers, then suppliers must be a big part of the process. The associated set of challenges for the OTD team, (comprising of over 30 different members of GM from different functional areas) is the integrated execution of key functional activities to meet customer requirements. Moreover, Buyer Power must be able to transfer information and provide visibility to suppliers via Supplier Power; Supplier Power must provide components to through Order to delivery cycle of planning, design, purchasing, production control and logistics, manufacturing, logistics, and sales and service and ultimately link up to Buyer Power (see Figure 2). A primary deliverable is to cut leadtimes from 50 to 60 days down to 30 days this year, and eventually down to less than a week. For World Wide Purchasing, this translates to three core objectives:

Define OTD requirements, based on input from suppliers.

Understand GM’s current sourcing footprint – is it capable of meeting these requirements? If not, change sourcing patterns and schedules to enable fulfillment of these requirements.

Integrate OTD requirements into all future request for quotations. Eventually, OTD requirements will simply become an entry level requirement for doing business with GM or any other automotive company.

While this appears to be a straightforward task, it is not. The functional leads on the OTD project must be aligned with the Supply Power initiative. Currently, Supply Power (a GM Supplier Portal) provides access to M3 schedules (aggregate volume schedules) that is useful for suppliers to understand broad levels of demand, but does not provide insights into specific part number requirements. Supply Power is linked to all aspects of GM operations, including design, engineering, manufacturing, production control, logistics, purchasing, e-GM, Sales and Marketing, etc. In addition, Supplier Power provides:

Real-time inventory status and production counts

Real-time advanced shipping notices

Online engineering specs

Quality and warranty data

Capacity planning

Supplier communications

Real-time supplier feedback and corrective action process

Link to GM TradeXChange

This is a good foundation for the OTD initiative to work from, but a significant number of challenges exist to realize the goal of complete visibility of requirements to suppliers up the supply chain.

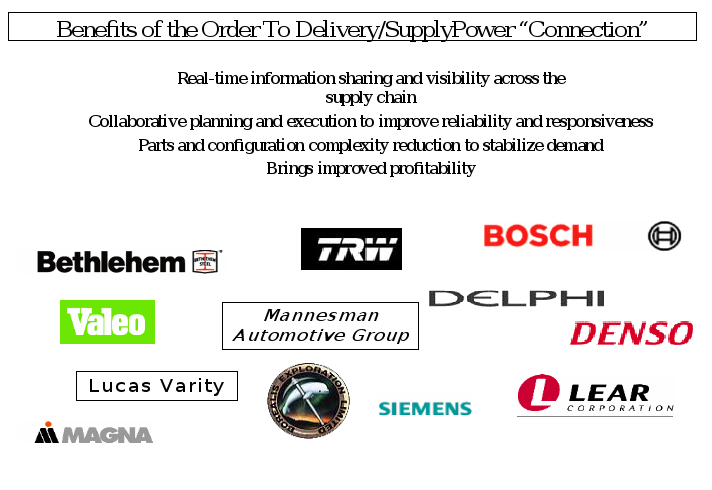

One Node of GM’s Network: Mountainview Automotive1Before embarking on the task of completely re-designing GM’s supply chain, Alagna and his colleague, Sue Toth, decided to conduct a series of pilot case studies with a group of suppliers who currently supply GM. He formed the “OTD Supplier Council”, consisting of some major suppliers to GM (see Figure 3). He also decided to work with Sandeep Sehgal, an NC State University Master of Science in Management student. Sandeep had worked in the auto industry in the Pacific Rim, and was majoring in E-Commerce and Supply Chain Management at NC State’s College of Management. Since GM is also part of NC State’s Supply Chain Management Resource Center, Dick invited Rob Handfield, the Director of the Center, to come along and work with the team. Dick and Sue decided to approach Mountainview first for a pilot case study for a number of reasons.

Overview of MOUNTAINVIEWMountainview Automotive is a manufacturer of electronic components headquartered in Japan, with sales of approximately $300M, with 50% of production in Japan and 50% in the US. It is one of the largest suppliers of switch module to the auto industry. It has its headquarters in Japan and its annual revenue exceeds $4 billion. Mountainview is the six times proud recipient of GM’s “supplier of the year award”. It has manufacturing plants in Korea, Japan, Mexico, and Europe, and produces a variety of products for the automotive and computer industries. In automotive, they build components for ignition switches, power windows, power mirrors, volume controls, and airbag harnesses in steering wheels. The latter product has a standard design that goes into virtually every automobile, but has undergone significant design changes. With the introduction of steering wheel volume controls and cruise control, the number of switches in this product has gone from 2 to 18. Mountainview produces products in all three types of GM demand streams: first tier, directed, and order specific. Mountainview is very well-positioned to grow with GM. It currently produces products for Isuzu, Subaru, Saab, Daewoo, and many other companies. Although GM is its largest customer in the US, it also produces products for every automotive company in the US with the exception of Mercedez Benz and Mitsubishi. It has won a GM QSP Award for the past six years in a row.

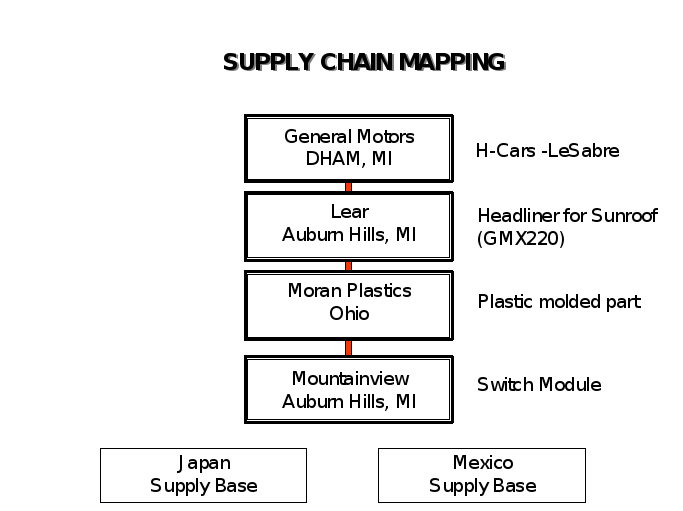

Dick, Sandeep, Sue and Rob visited the Mountainview facility in Auburn Hills, Michigan. The facility is a tier 3 supplier to General Motor’s DHAM- Hamtramck plant in Michigan. It supplies switch assembly for sun roof to Moran Plastics, who is a tier 2 supplier. Moran supplies the switch along with a plastic molded part to the tier 1 supplier Lear Corporation. This plastic part is one of the components that go in the making of the Headliner assembly of the H –cars (Le Sabre).

MOUNTAINVIEW Perspective – Improvement OpportunitiesIn response to Dick’s presentation, Michael Mitchell, the General Manager, made a number of key points that described some of the current supply chain issues that need to be resolved with GM. Mountainview has increased its business with GM from $50M in 1996, to $90M in 2000, and is projected to reach $140 M by 2006. Of this amount in 2005, close to $60M will be a directed source, which is a significant increase in the proportion of models. “Directed source” means that Mountainview will be supplying a first tier supplier (such as an interior module assembler), who will insert the components, ship them to GM, and pay Mountainview directly. The first tier is required to use Mountainview, hence a “directed source”. Mountainview has no desire to build panels and assemblies, but wishes to stay in components. They will consider producing subsystems, however.

The “Triplets”One of the first opportunities for improvement was the issue of design standardization. Michael brought out a set of three power window switch modules that were used on different GM platforms; visually they appear almost identical. Although the plastic outer knobs are not made by Mountainview, the population of components produced is, and are all very different. The PCV’s have different window pressure requirements, different circuits, power, motor characteristics of different vehicles, etc., and therefore have to work in different environments. The problem is that the differences between models are in some cases so minute, that production workers cannot tell them apart. In one case, the wrong set of knobs was shipped, and in testing them, they worked one time, but failed to work thereafter! Mountainview was able to ship new material in the next day, but it is important to try to prevent such design issues from occurring. The Triplets are illustrative of an opportunity to standardize and reduce design complexity. However, if Mountainview were to work with the engineering center to introduce families of products into vehicles, a lot of complexity could be reduced which in turn reduces the possibility of errors.

Mountainview Supply Chain – Lumbar Switch – Directed SourceThe second major issue is a bigger problems: re-designing GM’s current supply chain for components supplied by Mountainview. The supply chain for a GMT800 lumbar switch is very complicated, as parts come from Japan, which are shipped to Auburn Hills, and then to multiple locations of Lear, then to different GM facilities. The network is made even more complex by a lack of EDI in some cases, where orders are still done by fax or phone. The GMX310 program (Triplets) is even more complex. Components come from Japan, go to Alchem2 in Mexico, then onto Mountainview, who ships to Moran3 Plastics in Windsor Ontario. Moran is not connected online, so all information to and from is by fax. Schedule instability often causes chaos in Japan, leading to premium freight charges (someone hand-carrying a part onto an airplane) and engineering obsolescence issues. In some cases, both EDI and fax is used, although these do not match up correctly in some cases.

Order leadtime from Japan is typically 12 weeks. Moran Plastics is a small plastic injection molding operation, and is not used to scheduling suppliers (they typically order plastic resins in truckloads!) This is also typical of many smaller second third suppliers in the automotive supply chain (including Ford, Daimler Chrysler, and others). Few second and third tier suppliers have on-line capabilities, and in fact, many scheduling systems are manual. EDI transmissions may be printed out and simply handled manually within their operations. In the case of Lakeside, they were ordering quantities in excess of the M3 schedules. When Moountainview noted this problem, they were told “Don’t tell us how to place orders”. Moran has made numerous ordering errors in the past. For example, they were using the wrong Bill of Materials, and one scheduler was in fact ordering parts for eight doors per vehicle!

The result of over-ordering, of course, is product obsolescence when the end of life occurs. In January of 1998, Moran had ordered enough components for 50,000 vehicles, but only built 38,000. This resulted in $450,000 of obsolete inventory, which was split 3 ways between Moran, General Motors, and Mountainview. Although the M3 schedule is fairly accurate (within 5-10%), it measures production at an aggregate level, not at a component level. This is where problems occur, which in turn results in the typical “bullwhip” effect throughout the supply chain.

An important issue that has to be addressed in the case of a directed source is: who is the ultimate customer? Is it Moran, who orders the parts and pays Mountainview, or GM, who receives the final product produced by Lear with the parts imbedded in it? The answer right now is Lear – since they pay the bills, Mountainview must deal with them in day-to-day transactions and problems.

Further,

Information flows from GM to Lear via EDI, while it flows via faxes between Lear and Moran and between Moran and Mountainview. Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers do not have access to the GM SupplyPower and therefore are more susceptible to receiving inaccurate forecasts from their next higher tier supplier who usually build a buffer in there requirement. Further, shipment schedules sometimes reach the tier2 and 3 supplier late giving them less time to plan/schedule production. There are times due to poor planning, suppliers are asked to do premium freight shipments.

Other improvement opportunities abound.

Tier 1 Redirected Sourcing – Mountainview supplies a $20 part which is shipped to Moran to be fitted with a $3 part before being shipped to Lear. The higher value of the component makes Mountainview want to be maintained by the tier1 supplier instead of the tier2. At times the tier 2 supplier (Moran) has asked Mountainview to ship its switch module to Moran’s appointed third party. In one case, Lakeside told Mountainview that they had to ship their components to a subcontractor, since they were not making enough money inserting components into plastic parts. The third party then gets the part from both Moran and Lear, puts it together and ships it to Moran. All of a sudden, Mountainview had a different customer who was paying their bills, and GM had never approved this change. This third party is responsible for all payments to Mountainview. Financial history of these third parties is not known; it is not uncommon to find a third party who defaults in making payments. As a result Mountainview is forced to stop all further shipments to them. This kind of situation creates distrust among suppliers and increases the OTD time. To avoid this from happening, GM should be advised of all redirected sourcing at the tier 1 level.

Different Terms and Conditions – When Mountainview is a directed source from GM, they must deal with a variety of terms and conditions. GM’s terms were the original point of departure, but tier 1 suppliers have many different terms. GM should be advised and try to establish a standard set of terms for their tier 1 suppliers.

Unauthorized Debits – Mountainview has been penalized for quality issues which were not their fault. In one case, they were told by a tier 1 that “your switches are falling apart”, and were being penalized for quality problems. Upon closer inspection of the process, they discovered that during installation at Orion, a rubber mallet was being used to pound the switches into the plastic cases! A level 1 containment notice was being sent and Mountainview was having to pay for the defective units!

Inaccurate Forecasts – Forecasts that come in from the Tier 1 suppliers often do not match GM’s. As a result, frequent “pull-aheads” on certain models occur that require handcarrying and premium freight charges from Japan. A solution would be to help create “sensing” of customer requirements up the chain by option, enabling option penetration insights and some sense of which types of optional switches will be required.

Zero Leadtime – Pull-aheads related to inaccurate forecasts means that the tier 1 needs the part immediately (a good example being Worthington Plastics). On the other side of the coin, unexpected obsolescence occurs when the product line is suddenly ended with no prior notification – resulting in one case in $250 M of obsolete inventory. The pattern of pull-aheads and obsolescence is currently impossible to predict – better mechanisms for predicting demand in the chain is necessary.

Engineering Change Management – This is difficult to control, but critical. Mountainview has no way of managing the upstream breakpoint, and must effectively purge their supply chain of materials when they receive an ECN from GM or another tier 1. These are difficult to predict – even batching of these changes would help to some extent.

EDI Conflicts – Different data modules of Future3, an EDI add-on that allows Mountainview to integrate EDI into its JDEdwards ERP system, often causes problems. Future 3 has a different package for each customer, and in fact there exist 25 different modules being used in the GM supply chain. Unfortunately, the transition between these different modules and versions is not seamless: data packets are switched, and the result is EDI transmissions with incorrect data that is out of phase. Clearly, this is a critical issue for the OTD initiative. The OTD group must drive a standard Web-based application through the chain to enable sub-tier suppliers (many of whom are not on EDI today) to become compliant to this standard. Another issue with the current Supply Power system is that as the system was developed, all of the PO’s are by part number by location, meaning that Mountainview may receive 16 different documents for a single shipment of different part families (not just 1 document with the entire order on it). Although this is not ideal, what makes it more difficult is that Supply Power provides this information in pdf format, not in digital format. Thus, there is no way for Mountainview analysts to download the data into an Excel spreadsheet, graph it, and massage it to detect patterns and usage. Future upgrades should provide this format in a downloadable digital format.

Tier 1 Financial Health – This is an on-going concern. Here again, Mountainview has lost money in a situation where a tier 1 supplier to GM became insolvent.

Special Customs Audit – In one case, the government audited a shipment at customs for a week, delaying shipment. The solution will be to increase inventory at this point in the process.

The typical OTD time in GM is between 8-10weeks and the task of the OTD team is to work ways to reduce the time to 35 days in the year 2000. The target is to reduce the OTD time to 5-7 days by the year 2003.

Next Steps

Dick thought to himself about the case in time and said, “This is more or less representative of most suppliers.” What can be done to improve the situation? He had attended a workshop on CPFR (Collaborative Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment) and thought, will it work? CPFR has been very successful on the retail side of the supply chain, but recent material in the press has indicated that it can work of the other end of the supply chain i.e. the suppliers and the OEMs.

Another concept was that supplier parts had come out during a few meetings Dick had had with other functions at GM and Deloitte consulting. It is hard to implement in the US because of the pressure from the UAW (United Auto Workers), who see implementing it against their interests. They see their jobs being taken away and done by the suppliers.

GM is testing this concept at their Gravatai, Brazil plant, which is producing the Chevrolet Celta. For the first time, the world’s largest automaker is putting one of its suppliers on a vehicle assembly line. At GMs’ much watched Blue Macaw project in south Brazil, Lear Corp (one of the largest auto suppliers) has been assigned its own 8000-square-foot subassembly area within the assembly plant, dressing out doors for the Celta. Not only do the 10 to 12 Lear employees install locks, windows and other components in the doors, but they detach those doors after the car body leaves the paint shop and reattach the finished pieces as the vehicle nears completion on the assembly line. This project is unique throughout the global car industry. If successful the setup may be copied in future GM manufacturing operations. Further Lear is one of the 16 suppliers that have plants built adjacent to the GM’s manufacturing plant.

In order to reduce the OTD time, GM’s Celta plant is also testing use of co-designed modules being supplied by the suppliers. GM hopes to introduce the concept in their new Lansing Plant scheduled for production in 2003. With the Gravatai, Brazil plant GM is pushing the use of the Internet for ordering vehicles and hopes to deliver the Celta within 3 days of the order. It is easy to try new concept at new plants, but what needs to be done differently at the existing plants remains a challenge.

Dick had been given 3 months to come out with suggestions for improvement.

Prepared by Sandeep Sehgal and Robert B. Handfield

North Carolina State University

Copy Right:

1 Fictitious company name.

2 Fictitious name

3 Fictitious name