write a research paper on the issue of social economic effects on good governance with respect to the economic growth of nation. select a case study of a nation in the third world countries and write

105

MATTHEW NIYONGABO

Social economic effect of good governance on the economic growth of nations: Case study of Kenya

A Project Proposal in Partial Fulfillment for the Award of Doctorate in Leadership Administration and Management at North Western Christian University

DECLARATIONI declare that this research project is my original work and has never been submitted to any other university for the award of a degree.

Signature…………………………. Date……………………………

Declaration by the Supervisor

I declare that this research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University supervisor.

Signature…………………………. Date……………………………

Eldoret, KENYA

I do appreciate the moral, spiritual and financial support that was accorded to me towards this project by both my family members and Zion Holy City Pentecostal Church. I also give thanks to Northwestern Christian university Eldoret campus Director, Apostle Hannah Wairimu and my classmates for their spiritual, moral and technical support given to me towards this process. I also wish to address my thanks to the government of Kenya for the immense liberty and permission. Finally, I do appreciate the technical support and guidance given to me to accomplish this process by Mr. Emmanuel.

Dedication

I do dedicate this project to my beloved parents Edmond Nyabenda and Yollanda Bankuwiha. Jenifer Nininahazwe for her moral and financial support, Professor Miongechong for the spiritual support, Teresiah wangari, Dr.Robinson Makoha. More also to the almighty God for the gift of life, calling and strength that he has blessed me with to accomplish this project.

GDP- Gross Domestic Product

KANU Kenya African National Union

NEPAD The New Partnership for Africa’s Development

WB World Bank

MENA Middle East and North Africa

Kenyatta First President of Kenya

Moi Second president of Kenya

Kibaki Third president of Kenya

Table of Contents

ContentsDECLARATION 1

Acknowledgement 2

Vocabularies/Acronyms 4

Contents 5

Abstract 7

CHAPTER 1 8

1.1Introduction 8

1.2 Background of the Study 8

1.3 Statement of the Problem 11

1.4 Study Significance 13

1.5 Research Methodology 14

1.6 Purpose of the Study 14

1.7 Theoretical Framework 14

1.8 Research Objectives 15

1.9 Research Questions 15

1.9.1 Research Assumptions 15

1.9.2 Scope of the Study 16

1.10 Justification of the Study 17

Chapter 2 17

2.1 Introduction 17

2.2 Quality of Governance 26

2.3 Relationship between Good Governance and Economic Growth 32

2.4 Good Governance Explained 38

2.5 Service Delivery Theories 47

2.5.1 The Shared Governance Theory 47

2.6 Conflict Theory 52

2.7 Feedback Mechanisms Theories 54

2.7.1 The Citizen Involvement Theory 54

2.9 Citizen Empowerment 60

2.10 Governance and major growth theories 68

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 79

3.0 Introduction 79

3.1 Research Design 79

3.2 Population and Sampling 80

3.3 Data Collection 81

3.4 Data Analysis 84

3.5 Research Quality 85

3.6 Ethical Considerations 86

Chapter 4: DATA ANALYSIS, INTERPRETATION, AND PRESENTATION 89

4.0 Introduction 89

4.1 Questionnaire Response 89

4.2 Questionnaire Response Rate 89

4.3 Study Demography 90

4.4 Educational Level 90

4.5 Positive Indication of governance 91

4.6 Benefits of Proper Governance 92

CHAPTER 5: SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 94

5.0 Introduction 94

Conclusion 96

Recommendations 96

References 99

AbstractSub-Sahara African countries have had a checkered past when it comes to good governance and institutions. Increasingly, economists and policy makers are recognizing the importance of governance and institutions for economic growth and development. The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) has four main goals: eradicating poverty, promoting sustainable growth and development, integrating Africa into the world's economy, and accelerating the empowerment of women. Using fixed and random effects, and Arellano-Bond models, this paper investigates the role of governance in explaining the sub-optimal economic growth performance of African economies. Our results suggest that good governance or lack thereof, contributes to the differences in growth of African countries. Furthermore, our results indicate that the role of governance on economic growth depends on the level of income. In a nutshell, our results demonstrate that without the establishment and maintenance of good governance, achieving the goals of NEPAD will be hampered in Africa.

CHAPTER 1- Introduction

Kenya is a land endowed with much resources that can sustain its development and feed its people. Leadership Is a critical tool that determines the level of achievement a nation, institution, or organization can attain. In the recent times, Kenya, like most African nations has began experiencing good leadership that has registered increased development and a high appetite for foreign development and investment. The paper brings issues around governance with Kenya as the case study in examining the social economic effect of good governance through literature review of the past cases and a case study that looks into the specific factors under study.

1.2 Background of the StudyIt is every nation’s dream to grow and compete favorably with the rest of nations in an increasingly global world. In order to achieve this desire, the political leadership and government policies on development have to align and give room for players in the diverse industry to work independently in a cool political atmosphere. In Kenya, the pace of development has picked up with the reason being attributed to the development in governance standards that has elicited the present success. Development is directly tied to the governance patterns fixed on key leaders that hold the economy close to their heart. Improper leadership and governance always result in lower returns, cases of corruption, and an economy that fails to pick-up. The aspect of governance is an all-round affair that encompasses the political, economic, social, and cultural factor all of which contribute to an efficient growth in the GDP. The past two decades in Kenya have exhibited a spirited growth in the economy attributed to the kind of leadership in all the four dimensions.

International trade policy consists of bilateral and multilateral arrangements between countries I and dictates the terms of commerce between them. These trade policies and relations vary in ! scope and content but generally depend on the structure of the economy of a particular country. In developing countries, trade policy-making is shaped by the interaction of international and domestic factors - economic and political. At the international level, the processes of globalization play a major role in influencing and shaping subsequent trade policies. At the domestic level, policy-making is intimately linked with the nature of the public-private relationship as well as the autonomy of state agencies and their institutional strength and capacity. Trade policies and their coherency clearly have a bearing on the overall trade strategy pursued and consequently on the economic gains from trade. Kenya's trade policy development has evolved through the following distinct policy orientations: import Substitution Policies (1960s -80s); Trade Liberalization through Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs) (1980s) and Export Oriented Policies (1990s). Presently Kenya's Trade regime is guided by market-driven principles of liberalization under the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the increased efforts in the regional economic integration that has resulted in the establishment of the East African Community (EAC), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA.) This study reflects on Kenya's international trade experiences and examines the institutional arrangements and interaction of its actors in the trade policy formulation and negotiations processes. It also identifies and contributes to a better understanding of the factors that constrain effective formulation, negotiation, monitoring and evaluation of the country's international trade policy.

Therefore, the fate of the nation hanged on the leadership and the ability of the nation’s governance to strike trade deals through creating a good business environment that attracts investors.

The periods of 70s to 90s period were characterized by less development given the one-party issues that prevented the political wing from growing and rendering its benefits to the nation. Cases of dictatorship and open reward of the political class based on their affiliation prevented the free will and potential of the nation to grow as those that opposed the awarding were restrained and taken into political oblivion. However, the coming of multi-party in 1992 tagged along renewed hope for the nation with a raft of changes on the way. A decade later, after the exit of the long-serving regime KANU, a sigh of relief engulfed the nation. The period recorded a renewed growth in the infrastructure, manufacturing, and processing sectors that were steered by proper governance. The facts underlined inform the benefits of proper governance and its reflection on the development of a nation’s economy.

1.3 Statement of the ProblemGovernance is and remains to be a determining factor in as far as a country, continent, or world can go in achieving its socio-economic growth. The type of leadership a place has is directly related to the growth of a given place or region. Poor governance has always been a recipe of chaos and confusion that leads to lower or reduced development.

Governance in Kenya has faced many challenges leading to cases of poor economic performance over the past decades. It is commonly acknowledged that governance steers development, where the reverse leads to underdevelopment. The promulgation of the new constitution brought to an end a clamor that had persisted for more than twenty years that marked a period of agitation for better governance and greater democratic space. The structure of government was changed radically in the new constitution so as to position devolution at the core of national life.

Chapter eleven of the constitution of Kenya provide for devolution, its objects and principles, the county governments, functions and powers of the national and county governments and relationships between levels of governments.

To achieve these objectives, the constitution established 47 county governments in addition to the national government. Each county will have a government consisting of County assembly and County Executive. Since independence, Kenya has had long history o f bad governance, from the oppression of the British Colonial government, to the Kenyatta and Moi dictatorship and previously the Kibaki ineffective, undisciplined and un-responsive administration. Kenya has had a centralized form of government characterized by Constitutional limitations, failure to implement national policies, lethargy in the civil service, corruption, tribalism and impunity.

At the heart of the clamor for a new constitution was a determination by the people of Kenya to devolve governance and decision making so as to give them a greater say in how they and their resources are governed. Therefore, Kenyans have had high hopes for devolution so that they could change the kind of governance to have a government characterized by accountability, effectiveness, efficiency and responsiveness. Although efforts have been made to devolve governance in the past, the central government has always played an active role in undermining the same efforts hence the long history of unequal distribution of resources, poverty, exclusion of minorities, marginalization of some regions and communities of the country and thereby skewed development.

These mistakes can only be, to some extent, rectified through the proper establishment and operationalization of devolved governance so that the locals can manage and account for their own resources. Therefore, the paper seeks to point out the effects of proper governance on development of a nation using the case of Kenya as documented in its development record in the past two decades. The research shall outline the problem of poor governance in bringing up a struggling economy.

1.4 Study SignificanceGovernance determines a lot in the process of growth and development and thus remains a critical factor in understanding the rising and falling of economies. Enforcement of good governance leads to positive outcomes that steer a nation’s growth. The study findings and recommendations shall be important in understanding the core factors that lead to a given situation. The study shall be significant to the students in the leadership and administration in bettering their skills in operating different entities of the economy. Moreover, the research findings shall be important to policy developers and leaders in the governance sector in bettering their skills towards posterity. The study recommendations shall be important to the policy developers, future researchers, the prosecution departments, anti-corruption entities, and general public in understanding the underlying factors to proper governance.

1.5 Research MethodologyThe research uses several means towards achieving its end goals in understanding and overcoming corruption. The research involved evaluation of the existing literature on the identified research topic through the use of secondary data obtained from reliable sources including books, journals, government reports, documentaries, e-books, study reports, and past research works on corruption. Further, the research shall employ the use of questionnaires and interview in finding out the extent to which the issue prevails in the government departments. The combination of the two shall be essential in finding out and accomplishing the objectives to the research topic.

1.6 Purpose of the StudyThe study seeks to establish aspects surrounding good governance and their benefits to an all-round economic growth. It purposes to research on governance, its implications and examples of benefits accrued from proper leadership. The study shall help in understanding the determining factors to good governance as well as their benefits to the subjects as evidenced in the case of Kenya and its development in the last two decades.

1.7 Theoretical FrameworkThe research shall utilize the Utilitarianism theory in explaining the effects of good governance on the socio-economic development. Utilitarianism theory was developed by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. The theory is based on morality which advocates for acts that promote the overall goodness or happiness of individual while rejecting actions that cause unpleasant feeling or harm upon people. In this respect, it advocates for economic, social, and political good for the same of the people in bettering a society. The theory shall remain important towards discovering the good and pointing out the benefits it renders to the society.

1.8 Research ObjectivesThe objectives of this research are divided into two comprising the main objective and specific objectives. The main objective of this research study is to assess the impact governance on the development of a nation.

However, the specific objectives include:

To examine the aspect of governance in Kenya

To identify the benefits it renders to diverse entities

To examine the gaps obtained in improper governance situations

To suggest appropriate strategies to proper governance

- What is governance and how is it achieved?

-what aspects of governance are key to development?

-what are the benefits of good governance to a nation?

-what are the gaps in exercising proper governance?

1.9.1 Research AssumptionsThis research study was based on the assumption that; proper governance leads to development in the diverse sectors of the economy. Compliance to governance standards and remaining true to its values leads to development among partners in the economic sectors. The assumptions were based on the differences experienced in the previous regimes as opposed to the present operating in the last two decades in Kenya. .

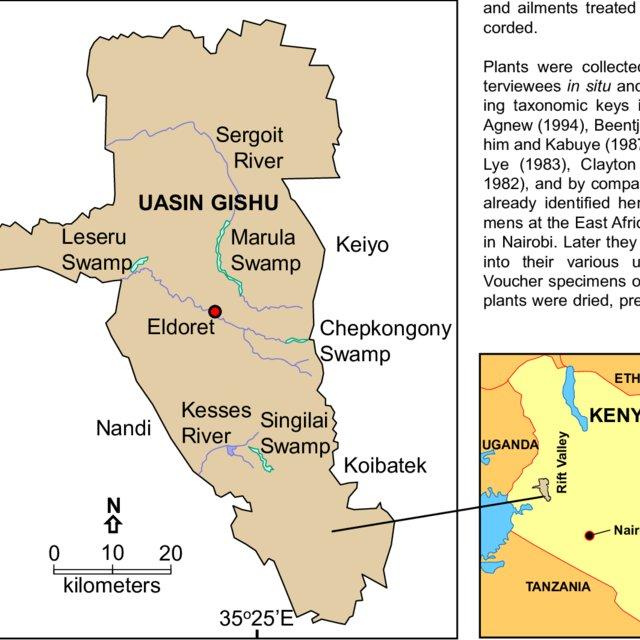

1.9.2 Scope of the StudyThe research acknowledges the steps taken in the process of enhancing governance. The study uses the case of devolved government and the national government to demonstrate the values of proper governance to the development exhibited across the nation. The research targets persons in the national and the county government leadership in obtaining information on the issue governance. In so doing, the study shall target government offices at both levels in ascertaining the measures embraced in developing governance to its people. The scope of study shall be limited to Uasin Gishu County, examining the leadership and devolution case and its effects on socio-economic development.

The global world focuses on good governance in realizing benefits for its nation. The differences in the government abilities around the world relates to opportunities and proper governance in implementing a change process. Thus, the study is important in portraying the effect of governance on the development aiming on the positive utilization of power to turn opportunities into benefits for the people. The study findings shall propel the need for good governance in ripping the benefits for the people. The study is justified in explaining the increased developments experienced in Kenya since the change of power in the last two decades of change.

Chapter 2 2.1 IntroductionSince the end of the Cold War until the early 1990’s, however, the issue of good governance has become an important concept in the international development debates and policy discourse. The working definition of what constitutes good governance has evolved over the years. Schneider (1999) defines good governance as the exercise of authority, or control to manage a country’s affairs and resources. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID, 2002), on the other hand, defines good governance as a complex system of interaction among structures, traditions, functions, and processes characterized by values of accountability, transparency, and participation. The UNDP (2002) defines good governance as striving for rule of law, transparency, equity, effectiveness /efficiency, accountability, and strategic vision in the exercise of political, economic, and administrative authority. Historically, sub-Saharan African countries have had a checkered good governance record in comparison to other regions of the world. These countries have been bogged down with political instability, government ineffectiveness, the lack of rule of law, and serious problems of corruption which are signs of bad governance. With respect to the importance of good governance to development, improving governance in this region has been given a central place in the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). Over the past few years, some countries in this region including, but not limited to Botswana and Ghana, have made significant progress in terms of governance.

The global distribution of income shows a highly uneven pattern of distribution. For instance, in 2015, the per capita GDP of North America was at least 34 times higher than the per capita GDP in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (Eds.). (2014). ). In addition to that, countries in some parts of the world have grown strongly, over time, while countries in other regions have not. The average nominal GDP in East Asia and the Pacific countries in 2015 increased by 3711 times in comparison with the figures in 1968. But in the same period, the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa grew only 868 times (The World Bank, 2016). These figures reveal a growth difference in the different parts of the world. Although the theoretical models including the Solow model and new growth theory provide some level of explanation for the economic growth within a particular geographic boundary, understanding of economic growth is still incomplete (Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (Eds.). (2014).

In addition to that, the existing growth models fail to provide a complete explanation for the cross-country growth differences. Human capital accumulation, physical capital accumulation, and technological progress are important determinants of economic growth in the major growth models. The concept of governance and its importance to economic growth was raised in the early 1990s (Atkinson & Bourguignon, 2014). Governance is a broad concept with great complexity to its major pillars. Governance is defined as a set of traditions and institutions that can be used to exercise the power of authority. Six basic dimensions of the governance are included political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, voice and accountability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, control of corruption and the rule of law (Atkinson & Bourguignon, 2014). These governance characteristics may influence several critical institutions that are essential for economic growth. These key institutions include well-defined property rights, unbiased contract enforcement, reduced information gap and stable macroeconomic conditions. The governance indicators influence on these and eventually decide the country's economic growth in two ways.

2.1.1 Good Governance

Economists agree that governance is one of the critical factors explaining the divergence in performance across developing countries. The differences of view between economists regarding governance are to do first, with the types of state capacities that constitute the critical governance capacities necessary for the acceleration of development and secondly, with the importance of governance relative to other factors at early stages of development. On the first issue, there is an important empirical and theoretical controversy between liberal economists who constitute the mainstream consensus on good governance and statist and heterodox institutional economists who agree that governance is critical for economic development but argue that theory and evidence show that the governance capacities required for successful development are substantially different from those identified by the good governance analysis. The economists in favor of good governance argue that the critical state capacities are those that maintain efficient markets and restrict the activities of states to the provision of necessary public goods to minimize rent seeking and government failure. The relative failure of many developing country states are explained by the attempts of their states to do too much, resulting in the unleashing of unproductive rent-seeking activities and the crowding out of productive market ones. The empirical support for this argument typically comes from cross-sectional data on governance in developing countries that shows that in general, countries with better governance defined in these terms performed better. In contrast, heterodox institutional economists base their argument on case studies of rapid growth in the last fifty years. This evidence suggests that rapid growth was associated with governance capacities quite different from those identified in the good governance model. States that did best in terms of achieving convergence with advanced countries had the capacity to achieve and sustain high rates of investment and to implement policies that encouraged the acquisition and learning of new technologies rapidly. The institutions and strategies that achieved these varied from country to country, depending on their initial conditions and political constraints, but all successful states had governance capacities that could achieve these functions. This diversity in governance capacities in successful developers means that we cannot necessarily identify simple patterns in the governance capacities of successful states, but nevertheless, we can identify broad patterns in the functions that successful states performed, and this can provide useful insights for reform policy in the next tier of developers. The empirical and theoretical issues involved here clearly have critical policy implications for reform efforts in developing countries. The second area of disagreement concerns the relative importance of governance reforms in accelerating development in countries at low levels of development. An important challenge to the mainstream good governance approach to reform in Africa has come from Sachs and others (2004) who argue that at the levels of development seen in Africa and given the development constraints faced by that continent, a focus on governance reforms is misguided. They support their argument with an empirical analysis that shows that the differences in performance between African countries is not explained by differences in their quality of governance (measured according to the criteria of good governance) once differences in their levels of development have been accounted for. The important policy conclusion that they derive is that in Africa the emphasis has to be on a big push based on aid-supported investment in infrastructure and disease control.

Good governance has several characteristics. It is participatory, consensus oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, effective, efficient, equitable, and inclusive and follows the rule of law. At a minimum, good governance requires fair legal frameworks that are enforced impartially by an independent judiciary and its decisions and enforcement are transparent or carried out in a manner that follows established rules and regulations. Since accountability cannot be enforced without transparency and the rule of law, accountability is a key requirement of good governance. Not only governmental institutions, but also private sector and civil society organizations must be accountable to the public and to their institutional stakeholders.

The United Nations Millennium Project, the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Reports, and the World Bank’s annual World Development Reports each list over one hundred “must do” items for countries to achieve good governance. Even allowing for the considerable overlap among the various items, it is a formidable agenda-not only for the world’s least developed and post-conflict countries, but also for many middle-income and transitional economies. However, the reports provide little prioritization or guidance regarding what governance items are essential and what can wait, how they should be sequenced and implemented, how much they will cost and how they will be paid for. They also suffer from flaws typical to commissioned reports: a tendency to provide “one-size-fits-all” prescriptions, despite the fact that research shows, although governance reforms share commonalities, they must also be judiciously determined on a country-by-country basis-the institutional innovations tailored to local political and institutional realities, with the most essential sequenced in first. The various report recommendations can be broadly divided into two sections: the general and the substantive. The general emphasize “capacity development,” which includes both the building of effective states (which can deliver public goods and services to the populace and ensure peace and stability), and an empowered and responsive society which can hold states accountable for their actions. The reports correctly note that poor or inadequate governance may not always be the result of venal or rapacious leadership, but because the state may suffer from weak formal political institutions and lack the resources and capacity to manage an efficient public administration. However, what is not always appreciated is that good governance cannot be had on the cheap simply through the implementation of bureaucratic and administrative policies.

Moreover, governance reforms without concomitant economic reforms are doomed to failure. Again, research shows that political-institutional reforms are more successful in settings where economic development already has started to take place. This is not to imply that political development is simply a consequence of economic development, but to underscore that institution building and consolidation are more likely to succeed where development already has taken place, or is taking place. Arguably, many of the items listed on the good governance agenda as preconditions for development are actually consequences of it. The implications are profound: institution building and the promotion of good governance demand simultaneous commitment to economic development. That is, what needs to be measured is the government’s delivery of public goods and not just its budgetary provisions, its actual accomplishments, and its good intentions. Substantively, the reports view institution building, democracy, and political-economic decentralization as essential for good governance and economic development. Although intuitively appealing, the questions of precisely how each contributes to democratic institutionalization and economic development are poorly understood-and the reports’ overly sanguine rhetorical statements shed little light on these issues. For example, how does a society devise an institutional framework that nurtures both democracy and market economies; how does it best ensure that government has sufficient power to provide security and public services, while being inhibited from predation on its own citizenry; how can democratic governance, economic growth, and human development become mutually reinforcing; or, how does a society prevent the devolution and decentralization of political-economic authority from exacerbating regional or particularistic divisions? Although the reports do not provide a nuanced discussion of these issues, a growing body of research sheds useful insights into these important issues. The following sections draw on this scholarly research to elaborate these concerns.

While informal interpersonal exchanges and social networks can serve the needs of traditional societies, modern economies (given their specialization and complex division of labor) require formalized political, judicial, and economic rules. In providing specific rules of the game, political and economic institutions create the conditions that enable the functioning of a modern economy. That is, formal institutions, by securing property rights, establishing a polity and judicial system, and implementing flexible laws that allow a range of organizational structures, create an economic environment that induces increasing productivity. To North, institutions are “growth enhancing” because they reduce uncertainty and transaction costs. Thus, North’s paradigm is often labeled as the “new institutionalism” because it has at its core a set of ideas derived from the analysis of “transaction costs”-that is, costs that result from the imperfect character of real-world institutions and that have to be surmounted in order for economic activity to occur. Specifically, the institutional framework affects growth because it is integral to the amount spent on both the costs of transactions and the costs of transformation inherent in the production process. Transaction costs are far higher when property rights of the rule of law are absent and not enforced. In such situations, private firms typically operate on a small scale and rely on extra-legal means to function. Conversely, an institutional environment that provides impartial third-party enforcement of agreements promotes exchange and trade because the parties know that a good or service will be delivered after it is paid for. Because institutions and the enforcement of rules largely determine the costs of transacting, good institutions can also minimize transaction costs-or costs incurred in making an economic exchange. Both political and economic institutions are necessary to sufficiently reduce transaction costs in order to make potential gains from trade realizable.

2.2 Quality of GovernanceGovernance quality is an important variable to explain investment rate which means one way to promote economic growth is improving the capital market and investment climate. Meanwhile, there are some other approaches by which good governance can improve economic performance, such as a stable bureaucratic system promoting long-term investment in the private sector (Moore, 2004). Bureaucratic professionalization encourages investment in public facilities; reduction of corruption and encouraging productive investment. Moreover, a good economic power structure promotes the optimization of resource allocation of a political power structure thus affecting economy system and economic policy.

Recently good governance has become conditionality for the disbursement of development assistance to less developed nations. Furthermore, foreign investors are increasingly basing their investment decisions on good governance. Granted, there are some economists including Owens (1987), and Sen (1990) who recognized and advocated for the need for political and economic freedom as an essential dimension for economic growth, these studies were theoretical discourses rather than being empirical expositions. Since 1990s, however, empirical studies in this area have dealt with the effects of lack of good governance rather than its direct impact on the economic growth of emerging countries. Given that the governance situation differs from one sub-Saharan African country to the other, the objectives of this inquiry are twofold. First, we investigate the effect of various governance indices on economic growth of sub-Saharan African countries while considering the conventional sources of growth. Second, we investigate whether the impact of these governance indicators differ by the conditional distribution of economic growth. Thus, we investigate whether the impact of governance on economic growth depends on the relative level of growth.

2.2.1 Growth Enhancing Governance

Growth Enhancing Governance

The prediction of the theory is that differences in the quality of governance measured by these characteristics will correlate with performance in economic development. We will see that the evidence provides at best very weak support for this prediction. There are at two related theoretical problems with this view of market-led development that are stressed in the growth-enhancing view. First, the historical evidence (some of it discussed below) shows that it is extremely difficult if not impossible to achieve these governance conditions in poor countries. In terms of economic theory, this observation is not surprising. Each of these goals, such as the reduction of corruption, the achievement of stable property rights and of an effective rule of law requires significant expenditures of public resources. Poor economies do not have the required fiscal resources and requiring them to achieve these goals before economic development takes off faces a serious problem of sequencing (Khan, 2005). It is not surprising that developing countries do not generally satisfy the market-enhancing governance criteria at early stages of development even in the high-growth cases. Thus, critically important resource re-allocations that are required at early stages of development are unlikely to happen through the market mechanism alone. Not surprisingly, a significant part of the asset and resource re-allocations necessary for accelerating development in developing countries have taken place through semi-market or entirely non-market processes. These processes have been very diverse. Examples include the English Enclosures from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries; the creation of the chaebol in South Korea in the 1960s using public resources; the creation of the Chinese “town village enterprises” (TVEs) using public resources in the 1980s and their privatization in the 1990s; and the allocation and appropriation of public land and resources for development in Thailand. Successful developers have displayed a range of institutional and political capacities that enabled semi-market and non-market asset and property right re-allocations that were growth enhancing. In contrast, in less successful developers, the absence of necessary governance capabilities meant that nonmarket transfers descended more frequently into predatory expropriation that impeded development.

Secondly, even reasonably efficient markets face significant market failures in the process of organizing learning to overcome low productivity in late developers (Khan, 2000). Growth in developing countries requires catching up through the acquisition of new technologies and learning to use these new technologies rapidly. Relying only on efficient markets to attract capital and new technologies is inadequate given that efficient markets will attract capital and technology to countries where these technologies are already profitable because the requirement skills of workers and managers already exist. Developing countries have lower technological capabilities and therefore lower labor productivity in most sectors compared to advanced countries, but as against this, they also have lower wages. If markets are efficient, capital will flow to sectors and countries where the wage advantage outweighs the productivity disadvantage. However, for many mid to high-technology sectors in developing countries, the productivity gap remains larger than the wage gap. This explains why most developing countries specialize in low technology sectors and why this specialization would not change rapidly if markets became somewhat more efficient. However, if developing countries could accelerate learning, and therefore productivity growth in mid to high-technology sectors, this would amount to an acceleration of the pace of development. Rapid catching up therefore typically requires some strategy of targeted technology acquisition that allows the follower country to catch up rapidly with leader countries. However, technology-acquisition strategies have been remarkably diverse and high-growth countries have used very different variants of growth enhancing governance that allowed the acceleration of social productivity growth. Thus, not only are markets unlikely to become very efficient in developing countries, even relatively efficient markets would not necessarily help overcome some of the critical problems constraining rapid catching up in developing countries. To the extent that productivity growth depends on better resource allocation, improving market efficiency is clearly desirable. But sustained productivity growth depends on the creation of new technologies or (in the case of developing countries), learning to use existing technologies effectively. Markets by themselves are not sufficient to ensure that productivity growth will be rapid unless appropriate incentives and compulsions exist to induce the creation of new technologies or the learning of old ones. While technical progress is possible along the trajectory set by a market-driven strategy, the climb up the technology ladder is likely to be slower through diffusion and spontaneous learning compared to an active technology acquisition and learning strategy. But to achieve growth faster than that possible through spontaneous learning and technology diffusion, states have to possess the appropriate governance capabilities both to create additional incentives (rents) for investments in advanced technologies that would not otherwise have taken place but also to ensure that non-performers in these sectors do not succeed in retaining the implicit rents. The creation and management of incentives by states in developing countries has been very diverse. In many developing countries, import substituting industrialization attempted to leapfrog technological levels by protecting domestic private or public sector enterprises. But the absence of credible commitments to withdraw support in case of failure and of adequate institutions to assist technology acquisition and learning meant that in most cases, the results were inefficient public and private sector firms that never grew up. Successful countries used many policies that appear superficially similar, including tariff protection, direct subsidies (in particular in South Korea), subsidized and prioritized infrastructure for priority sectors (in China and Malaysia), and subsidizing the licensing of advanced foreign technologies. But while the mechanisms used in many less successful developers appear similar to the ones on this list, there were significant differences in the governance capacities for successfully implementing growth-enhancing strategies.

2.3 Relationship between Good Governance and Economic GrowthNumbers of economists of development consider that good governance, defined as the quality management and orientation of development policies has a positive influence on economic performance. The question is what content the literature gives to the concept of governance? According to the World Bank, good governance is evaluated by the implementation capacity of governance principles of a country, providing a framework for market development and economic growth (Mira & Hammadache, 2017). However, a good governance policy is allows developing countries to achieve minimum economic growth and political reforms in order to reach a level of development similar to that of industrialized countries? We focus on the definition and the work on the concept of good governance made by the World Bank and criticism that reconstructed the notion of governance in a broader sense, taking into account the capacity of states to drive structural change in institutional, political, economic and social fields, in order to ensure long-term economic growth.

Economically, the proper functioning of markets is correlated to the proper functioning of institutions through efficient practice of state governance, what is commonly called” good governance”. Therefore, underdevelopment and low economic growth performance of countries could be explained by a ”state failure” and the components of good governance with the increase in corruption, instability of property rights, market distortions, and lack of democracy (Mira & Hammadache, 2017). The transition of developing countries towards a capitalist system comparable to that of developed countries, cannot operate without the establishment of efficient institutions in relation with distribution of political power in these countries.

Conversely, those countries would face a state failure, as a result of a mismatch between institutions and economic policy for development. The research consists first to present the results of an empirical model that we have done based on a panel of developing countries chosen by region (MENA, Latin America, and Asia) and due to their natural resource endowment. The aim is to check if growth rate may or may not be correlated with good governance indicators as defined by the World Bank (Fayissa & Nsiah, 2013). The goal is to lead in a second time an analysis of criticism made by Mushtaq Khan on the definition of governance, the causes of state failure and barriers to economic development.

Our contribution is to discuss the concept of good governance and the failure of states that take into account the level of development and governance capacity that is based on a structure and distribution of political power that evolves in time and may or may not be positive for growth. The assumption we make here is that the so-called good governance policies are relevant if countries reach a sound level of economic and social development that enable institutions of good governance to boost growth.

2.3.1: Democracy and Economic Development

Not only are political institutions necessary for economic development more likely to exist and function effectively under democratic rule, but also the adaptive efficiencies are best sustained in democracies because institution building to promote good governance and economic development is conterminous with democracy. It is no accident that countries that have reached the highest level of economic performance across generations are all stable democracies. Today, liberal democracy justifiably enjoys near-universal appeal and is regarded as the ideal system of government. According to the “procedural minimum,” liberal democracy is a form of government by means of which citizens, through open and free institutional arrangements, are empowered to choose and remove leaders in a competitive struggle for the people’s vote. According to Robert Dahl, the dean of democratic studies, a truly representative democratic government must be based on the principles of popular sovereignty; competitive political participation and representation; an independent judiciary; free, fair and regular elections; universal suffrage; freedom of expression and conscience; the universal right to form political associations and participate in the political community; inclusive citizenship; and adherence to the constitution and the rule of law. Scholars have long argued that democracies have embedded institutional advantages that support economic development. According to Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, democracies enrich individual lives through the granting of political and civil rights, and do a better job in improving the welfare of the poor, compared to alternative political systems. Second, they provide political incentives to rulers to respond positively to the needs and demands of the people. That is, democracies are seen to be responsive to the demands and pressures from the citizenry, since the right to rule is derived from popular support manifested in competitive elections-or as Robert Dahl long ago noted: governmental responsiveness to citizens’ demands is built into periodically held electoral contests guaranteed by juridically protected individual rights. No doubt, the experiences of the proverbial developmental states of East Asia (Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) offer evidence that efficacious state capacity and good governance can be achieved in developmental authoritarian regimes-albeit, not in predatory authoritarian systems. Yet, it is also recognized that authoritarian regimes that are “developmental” are an exception rather than the rule, as authoritarian regimes are more conterminous with pathologies such as predation and expropriation. Minxin Pei makes precisely such a case with reference to the PRC-which at first glance has all the attributes of a developmental state, but is not. Pei’s examination of the sustainability of the Chinese Communist Party’s developmental strategy-that of pursuing pro-market economic policies under dictatorial one-party rule leads him to a number of novel conclusions. Perhaps, most provocatively, Pei refutes the conventional view which sees the Chinese model as reminiscent of the East Asian “developmental state.” Moreover, democracies, unlike authoritarian regimes, offer a better long-term protection of property rights as well as individual and collective freedoms. Indeed, Robert Barro’s cross-country study finds only three former dictatorships in the world (Chile, Singapore, and South Korea) that had not engaged in any expropriation. Also, as noted, recent research on the authoritarian legacies in East Asia has questioned the “human developmental outcomes” of these developmental states. David Kang’s important book, Crony Capitalism: Corruption and Development in South Korea and the Philippines, compelling shows that authoritarian regimes, including the erstwhile developmental ones such as South Korea-once they were well-entrenched-rarely showed any concern for the greater public good and long-term growth.

Contrary to popular belief, under authoritarian rule, health care accessibility was piecemeal and “health care policy outcomes far from universal.” However, Wong notes that the transition toward democracy in both countries dramatically changed the political imperatives of social policy reform. Vote-seeking politicians needing to promote popular policies aligned themselves with health-care reform advocates, including grass-roots activists, to push top-level bureaucrats to implement reformist programs and policies. The end result is that there is a qualitative difference between health care (including other welfare measures) under authoritarian rule and since democratization. In Wong’s view, greater democratic participation in Taiwan and South Korea literally has led to a revision of the social contract between the state and popular classes. His research underscores how democratic political competition in South Korea and Taiwan has compelled the state to redirect its energy away from simply narrow conceptions of economic development (meaning rapid industrialization) to address quality-of-life issues such as health care and education, among other welfare-enhancing measures.

Evidence from a poor democracy such as India is also illustrative. Jenkins claims that, in practice, the Indian state has a far greater degree of autonomy than is assumed by theorists who claim that a democratic state can be easily compromised and captured by particularistic groups, lobbies, dominant-class coalitions, and other vested interests. To the contrary, he argues that India’s “real” functioning democratic state (unlike the idealist theoretical conceptions of it) is actually made up of a rather loose, fluid, and frequently changing conglomeration of interest groups. This reality on the ground gives the state much flexibility and autonomy over policy issues. According to Jenkins, nothing underscores this more vividly than the introduction of economic reforms in 1991 and their continued sustainability. He asks (1) why and how India’s governing elite, long-wedded to a statist-cum-protectionist economic program, suddenly abandoned this in favor of integrating India into the global economic system; (2) how the governing elite succeeded in “selling the benefits of reform to individual constituencies and the public at large,” and (3) how the elite went about implementing their ambitious economic reform agenda. To Jenkins, the answers to these questions lie in appreciating the mechanisms under which “real democracy” functions in India-which he argues can best be understood as “incentives,” “institutions,” and “skills.” With regard to incentives, India’s mercurial political elites are willing to take risks (i.e., to introduce reforms) because they have correctly calculated that reforms will not endanger their political and electoral survival. They know the rules of the game well enough to develop new avenues for collecting rents, distributing patronage, and, given the highly fluid and fragmented nature of interest groups, creating new coalitions for reform, including dividing and isolating interests opposed to reform. Similarly, India’s political institutions, both formal (federal structure) and informal (political party networks), work in ways that help the political elites to implement reforms with surprising ease.

2.4 Good Governance ExplainedFirstly, good governance means strong government capacity, namely, local government has enough resources, such as manpower and financial resources; to improve the capital market and investment climate; to keep the bureaucratic system stable and maintain bureaucratic professionalization; to develop a good economic power structure and political power structure; to promote system reform in all fields like science and technology; and to provide public services like medical treatment and education, which facilitates industrial upgrading and economic growth, resulting in strengthening the “helping hand” of government power (Fayissa & Nsiah, 2013).

The Nature of Governance

The Nature of Governance The root of the word governance, like government, is a word related to steering a boat. A steering metaphor is indeed a good way in which to approach the idea of governance in contemporary societies. Societies require collective choices about a range of issues that cannot be addressed adequately by individual action, and some means much be found to make and to implement those decisions. The need for these collective decisions has become all the more obvious when the world as a whole, as well as individual societies, are faced with challenges such as climate change, resource depletion. and arms control that cannot be addressed by individual actions, and indeed are often cases in which individual self-interest is likely to result in collective harm (Hardin, 1977; Ostrom, 1990). Governance also implies some conception of accountability so that the actors involved in setting goals and then in attempting to reach them, whether through public or private action, must be held accountable for their actions (Van Keersbergen and Van Waarden, 2004) to society.

Effective governance, except in very rare exceptions, therefore, may be better provided with the involvement of State actors, and hence governance is an essentially political concept, and one that requires thinking about the forms of public action. The tendency of some contemporary theories of governance to read the State out of that central position in governance therefore appear misguided. Just as more traditional versions of governance that excluded non-State actors ignored a good deal of importance in governing so too would any conception–academic or practical–that excluded the State from a central role. There are a variety of ways in which these collective problems associated in governance can be addressed. Scholars have advanced some rather important arguments that autonomous action through voluntary agreements can solve these problems (Ostrom, 2005; Lam, 1998). This style of solving collective action problems is important but may depend upon special conditions, and perhaps on factors such as leadership.

In addition to the monopoly of legitimate force, governments also have ex ante rules for making decisions. At the most basic level these are constitutions (Sartori, 1994) and then there are rules and procedures within public institutions that enable them to make decisions in the face of conflicts. Although many of the social mechanisms that have been central in thinking about governance may be able to involve a range of actors but these mechanisms may encounter difficulties in reaching decisions, and especially in teaching high quality decisions (but see Klijn and Koppenjanns, 2004). Lacking ex ante decision rules, networks and analogous structures must bargain to consensus through some means or another. This style of decision-making may appear democratic but it is also slow and tends to result in poor decisions. Others argue concerning systems in which all actors have de facto vetoes outcomes tend to be by the lowest common denominator, so that highly innovative and potentially controversial decisions are unlikely to emerge. This “joint decision trap” can be overcome in part by recognizing the iterative nature of decisions and by the capacity of actors involved to build package deals that enable them to overcome marked differences in preferences.

Effective government matters, but what is it? Good governance indicators go some way to provide a definition, but how much do they say about what effectiveness is, why this is so, and how it matters to development? This article argues that much work on the good governance agenda suggests a one-best-way model, ostensibly of an idyllic, developed country government: Sweden or Denmark on a good day, perhaps. The implied model lacks consistency, however, seems inappropriate for use in the development dialogue and is not easily replicated. In short, it resembles a set of well meaning but problematic proverbs. The good governance picture of effective government is not only of limited use in development policy but also threatens to promote dangerous isomorphism, institutional dualism and “flailing states”. It imposes an inappropriate model of government that “kicks away the ladder” that today's effective governments climbed to reach their current states. The model's major weakness lies in the lack of an effective underlying theoretical framework to assist in understanding government roles and structures in development. A framework is needed before we measure government effectiveness or propose specific models of what government should look like. Given the evidence of multiple states of development, the idea of a one-best-way model actually seems very problematic.

Additionally, China’s economy has the characteristics of transition and development, which may bring market absence and market failure, resulting in a negative impact on local economic growth. Therefore, local governments must play an important role in economic growth to weaken the “grabbing hand” of market power.

Secondly, good governance also means that market mechanism plays a key role in resource allocation, which can make full use of local comparative advantages, and strengthen the market competitiveness of products, resulting in the expansion of the market share of enterprise and the scale of industry, and the rapid growth of the local economy in China (Fayissa & Nsiah, 2013). Therefore, we define the positive effect of the market on economic growth as the “helping hand” of market power. At the same time, the full development of local market economy not only supports the “helping hand” of government power by providing tax, products, and services, among others, but also weakens the “grabbing hand” of government power by forcing the local government to gradually reduce the intervention.

Thirdly, good governance also means rule of law, that is, market subjects and government entities are forbidden to act as the “grabbing hand” and are encouraged to be the “helping hand” by legal institutions, they are willing to act in strict accordance with the law, none of them have the privilege to overstep the Constitution and other laws. Rule of law belongs to the software infrastructure, and has an important impact on local economic growth by institutionalization (Fayissa & Nsiah, 2013). For example, through the protection of private property rights, rule of law weakens the “grabbing hand” of government power, and strengthens the “helping hand” of market power; through the protection of intellectual property rights, rule of law relieves the “grabbing hand” of market power, and encourages the “helping hand” of market.

Political Change and Governance Outcomes

The arguments pointing to the efficacy of elections are intuitively appealing. The lower the cost to citizens of expelling non-performing officials, the more we would expect officials to act in the interests of citizens. In practice, however, electoral markets are often highly imperfect, disrupting electoral accountability and the ability of citizens to sanction governments that allow poor governance outcomes to persist. One key political market imperfection is uninformed citizens. If citizens cannot draw a connection between public policy and their own welfare, neither elections nor other, non-electoral means of expelling politicians easily limit governance abuses by government officials. Citizens may not understand the relationship between political decision making and their welfare, perhaps because of substantial delay between government actions and welfare changes (for example, banking crises triggered by corrupt financial sector regulation may not emerge until years after corrupt regulatory decisions are made); or shocks cloud the ability of citizens to assess political contributions to their welfare. India experienced a number of significant shocks in the 1970s that had this effect. A second political market imperfection arises when the promises of politicians are not credible. For example, if the leaders of non-elite parties cannot credibly promise to non-elites that they will refrain from expropriating non-elite investments, the introduction of elections in unequal societies does not necessarily result in faster growth. Parties struggle to build reputations for preferring particular policies or for serving particular groups of citizens better than their opponents. When political competitors cannot make broad promises, they resort to appeals to those narrow groups of citizens to whom they can make credible promises—but when those groups are narrow, incentives to improve governance for all citizens dwindle (Keefer and Vlaicu 2005). An important aspect of the political history of India that underlies changes in the governance environment is the emergence of credible political challenges to the Congress Party. Political market imperfections are more acute in countries beset by deprivation or profound social polarization. Isolated and poor populations are less likely to know of the relationship between political actions and the governance environment, or to appreciate the importance of the country’s governance environment for their own personal well-being. Similarly, in countries riven by social tension, the costs of making credible political promises to all citizens dwarf those of making promises targeted to individual groups. Each political competitor belongs to one of the groups and is therefore mistrusted by all the others. Political checks and balances also play a significant role in improving governance outcomes. They limit the ability of narrowly focused parties or individual decision makers to act unilaterally in their own interests. Efforts to divert resources for private benefit, or to expropriate some citizens to favor others, are all more difficult in the presence of political checks and balances. More obviously, political checks and balances limit the chances that any one leader will embark on disastrous policy experiments. Regardless of whether they face competitive elections, political leaders pursue good governance outcomes to the extent that it helps them remain in office. If improving the economic welfare of all citizens is a cornerstone of the leadership’s political strategy in a country without competitive elections, then the leadership has a strong incentive to pursue good governance. They can do this if they build a large ruling party and develop intra-party institutions that allow them to make credible promises to party members. The logic here is straightforward: government leaders cannot convince average citizens that they will not expropriate their investments, since average citizens have no easy way to punish such expropriation. However, if government leaders can make credible promises to party members, the larger the number of party members, the greater is investment, and the greater is the demand for the labor of average citizens. The key change in China from the 1970s to the 1980s was the introduction of institutions that constrained the discretion of the top leadership towards the large membership of the Communist Party. Large parties, organized to protect members from arbitrary decisions by the party leadership, are costly for leaders to establish; hence, their rarity (Gehlbach and Keefer 2006). For example, a necessary condition for party member loyalty is that members receive larger rents than they could outside the party. As their number rises, so too does the share of rents party members as a whole receive. All of the intra-party institutions that make promises to party members credible also require leaders to surrender rents. Intra-party checks and balances reduce the rent share of any individual leader. Investments in elaborate intra-party evaluation and promotion processes, such as those China introduced in the 1970s and 1980s, enhance credibility, since the investments are lost if the criteria are violated. They also are expensive. Regular turnover of the party leadership and rule-based succession improves the credibility of leaders, but these obviously reduce the share of rents that flows to party leaders. Institutionalized parties in settings without competitive elections are therefore less likely where large rents can be extracted from little investment; President Sese Mobutu, for example, made no attempt to create a broad-based, institutionalized political party in Zaire, choosing instead to personalize government and to treat even close supporters unpredictably. The huge rents available from natural resources (copper) explain this strategy: the gains from credibility (higher rents from productive investment) were offset by the natural resource rents he would have lost if he had had to share them with a broad, institutionalized party. Power sharing is also less likely when a single leader of the unelected government commands disproportionately more influence (military, popular or otherwise) than the others. When this is not the case, political checks and balances emerge naturally, as the consequence of a balance of power among key leaders. When the distribution of power within the leadership group is unbalanced, as in China under Mao Zedong, political checks and balances are difficult to establish.

2.5 Service Delivery Theories 2.5.1 The Shared Governance TheoryThe theory of shared governance is best demonstrated when he wrote about the desired need to reorganize Canadian health care institutions. In his study, Anthony argued that one of the early but enduring goals of the shared governance theory was to improve the work environment of nurses, their satisfaction, and retention (Fan & Zietsma, 2017). A number of pre/post shared governance implementation studies demonstrate their effect on the work environment. Historically, the theoretical underpinnings of the shared governance seem to have been anchored on a broad set of perspectives that included organizational, management, and sociological theories.

Understanding the variation in these theoretical viewpoints helps us to appreciate the history of how the shared governance theory was designed and implemented. The earliest foundation for shared governance arose from the human resource era of organizational theories. This era represented the first departure from the traditions of scientific management. Theorists such as Herzberg in 1966 and McGregor in 1960 championed employees as an organization’s most important asset encouraging 17 organizations to invest in employee motivation and growth (Fan & Zietsma, 2017). From the human resource era emerged business and management philosophies that directly influenced the development of the shared governance model. It has influenced broader redesign initiatives that emphasize performance.

A critical examination of the shared governance theory reveals that its tenets are so similar to the fundamentals on which public participation is anchored. Practicing the shared governance theory seems to suggest that it leads to an accrual of greater performance benefits of organizations and a significantly improved work environment (He, Eden & Hitt, 2016). This theory, therefore, is a great anchor of this study on public participation within the discourse of devolution in Kenya. The belief that large and monopolistic public bureaucracies are inherently inefficient was a critical force driving the emergence of the new public management. The theory represents a set of ideas, values and practices aimed at emulating private sector practices in the public sector.

Recently, there was a need to reinvent government and harness the entrepreneurial spirit to transform the public sector and later “banish the bureaucracy”. The new public management theory takes its intellectual foundations from public choice theory, which looks at government from the standpoint of markets and productivity, and from managerialism, which focuses on management approaches to achieve productivity gains (He, Eden & Hitt, 2016). The three underlying issues which new public management theory attempts to resolve includes: citizen-centered services; value for taxpayers’ money and a responsive public service workforce.

Notably, there are also studies that indicate that the new public management reforms do not necessarily lead to 18 improved service deliveries. The new public management is often mentioned together with governance. Governance is about setting up of structure of government and of overall strategy, while new public management is the operational aspect of the new type of public administration. The theory has also been supported by individuals who contend that the dominant theme of new public management is the use of market techniques to improve the performance of the public sector.

The main features of new public management include performance management, e-governance, contracting out and outsourcing, decentralization and accountability among others. The proponents of this theory advocates that the government should put in place social accountability mechanisms to increase efficiency in service delivery. The new public management theory is relevant to the current study as it informs public participation, social accountability practices and service delivery variables (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2017). The theory advocates for citizens participation in the process of evaluating public services since the new public management principle of customer responsiveness requires that the degree of the user satisfaction be measured.

This study drew from the theory of new public management in understanding the impact of social accountability on service delivery. The broad idea of new public management theory, is the use of market mechanisms in the public sector to make managers and providers more responsive and accountable (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2017). The theory is also important in understanding the service delivery variable. The rationale of establishing county governments is to ensure efficient service delivery. In this regard, county governments are important tool for new public management reforms in improving the quality public services and increasing the efficiency of governmental operations.

The new public management theory is, therefore, evident in the quality of services delivered by the county governments and is a great anchor of this study (Schwartz, 2017). This theory refers to measures that are designed to improve the overall performance of an organization (as a composition of sub-systems) by increasing its effectiveness and legitimacy. It advocates for the establishment of a solid foundation for management structures, public participation, policies and procedures which help institutions to fulfill their set goals. Although, this could lead to legal challenges, delays and cost to decisions, applying the governance theory in the management of devolved systems ensures full participation of all the stakeholders and sectors within the devolved governance systems (Schwartz, 2017).

2.5.2 Government Functional Requirements

Goal Selection

Governing is steering and steering requires some knowledge about the destination toward which one is steering. This function can be performed by State actors along but also may involve social actors. We do need to remember, however, that goals are not simple, and exist at a variety of levels ranging from broad goals such as “social justice” down to operational goals of departments and programs. Therefore, effective governance requires the integration of goals across all levels of the systems.

Goal Reconciliation and Coordination

The multiple actors within government all have their own goals, and effective governance therefore requires establishing some priorities and coordinating the actions taken according to those priorities.

Implementation

The decisions made in the first two stages of the process above must then be put into effect, requiring some form of implementation. This stage of the process is more likely to can be performed by State actors along but also may involve social actors. A successful implementation calls for a proper governance and leadership that is mandated to execute the deliberations to its latter form.

Feedback and Accountability

Finally, individuals and institutions involved in governance need to learn from their actions. This is important both for improving the quality of the decisions being made and also important for democratic accountability. Therefore, some well-developed method of feedback must be built into the governance arrangements. These functions are rather basic to the process of governance, and can be elaborated further by considering the processes involved, such as decision-making, resource mobilization, implementation and adjudication. The functions themselves may be excessively broadly conceived, but the process elements involved in them can be detailed to a much greater extent and can also be related to many processes discussed in other areas of political science.

2.6 Conflict TheoryAny political system revolves around conflict. A study observed that conflict is a struggle over values and claim to scarce resources, services, power and resources (Rupesinghe, 2016). The author further observed that conflict, between inter groups and intra groups are part of social life and is part of relationship building and not necessarily a sign of instability. It is worth noting at this point that all cases that involve people from diverse backgrounds, social and political beliefs necessarily witness levels of conflict (Rupesinghe, 2016). However, there are positive effects of conflict which include; the development of a sense of identity, priority setting and provision of legitimate ground for organizing and seeking preventive measures, management and conflict resolution approaches.

In this context, conflict serves as a lens to monitor institutional and government activities whose target beneficiaries are the citizens. According to Rupesinghe (2016), conflict is the main feature of partnership experienced between the government, private sector and nonprofit centers.

Conflict management has become a major source of concern. These conflicts can affect the county government decision-making process due to public servants’ personal or private interests. The process can be affected either positively or negatively.

The assessment of public understanding on devolution is essential in the development process. Misunderstanding on devolution leads to low expectations on leaders as well as low participation by the public. This obviously creates a gap between the public and the leaders in the society thereby a challenge in the development process (Lubell, Mewhirter, Berardo & Scholz, 2019). On the other hand, understanding leads to high expectations from the leaders and raises participation of the public in the development process. Positive effects of conflict are highlighted and include developing a sense of identity, priorities setting and provision of legitimate ground for organizing, seek preventive measures, management and resolution systems (Lubell, Mewhirter, Berardo & Scholz, 2019). Although conflicts among citizen is a major source of due to personal vested interest it should be closely monitored to avoid stifling performance and it is not necessarily a sign of instability and is part of relationship building hence the application of the theory to boost performance in the devolved governance systems.

2.7 Feedback Mechanisms Theories 2.7.1 The Citizen Involvement TheoryCitizen participation is a process which provides individuals an opportunity to influence public decision-making process. The roots of citizen participation can be traced to ancient Greece and Colonial New England. Before the 1960s, governmental processes and procedures were designed to facilitate external participation. Citizen participation was institutionalized in the mid1960s with President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society Programs (Beresford & Croft, 2016).

Democratic decision-making in contrast to bureaucratic or technocratic decision making is based on the assumption that all who are affected by a given decision have the right to participate in the making of that decision. Participation can be direct in the classical democratic sense, or can be through representatives for their 21 point of view in a pluralist-republican model (Beresford & Croft, 2016). In a democracy, it is the public that determines the direction to go and their representatives and bureaucratic staff role is to get them there. This means the end should be chosen democratically even though the means are chosen technocratically. Although many government agencies or individuals choose to exclude or minimize public participation in planning efforts claiming citizen participation is too expensive and time consuming (Beresford & Croft, 2016). Yet, many citizen participation programs are initiated in response to public reaction to a proposed project or action.

A successful citizen participation program must be: integral to the planning process and focused on its unique needs; designed to function within available resources of time, personnel, and money; and responsive to the citizen participants (Beresford & Croft, 2016). At a practical level, public consultation programs should strive to isolate and make visible the extremes. The program should therefore create incentives for participants to find a middle ground. This theory instigates public participation as an influence of performance of devolved governance systems in Kenya. 2.8 The Communication Development Theory Development

Communication is an educational process. It aims at developing social consciousness, personal responsibility towards one’s fellowmen, one’s community and country. In other words, it is a social conscience hence sensitizing the conscience. Beunen, Van Assche & Duineveld (2016) imply development communication as respect for the human person, respect for his intelligence and his right to self-determination. Development communication help organization to engage the community as a stakeholder in educative and awareness issues and this helps to establish conducive working environment for assessing risks and opportunities and promotes information exchanges to bring about positive social change via sustainable development (Beunen, Van Assche & Duineveld, 2016). Development communication implies respect for the human person, respect for his intelligence and his right to self-determination.