Course is Strategic Management Case - Cervus equipment corporation: Harvesting a new future: write one page summary and the theme is Cervus Equipment’s approach to growth. 1 1/2 single spane. Case wha

.

![]()

W13414

CERVUS EQUIPMENT CORPORATION: HARVESTING A NEW FUTURE

Daniel J. Doiron and Davis Schryer wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality.

This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) [email protected]; www.iveycases.com.

Copyright © 2013, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation Version: 2014-11-18

Looking out his office window at the growing skyline surrounding the Calgary Airport, Graham Drake thought about the recent growth of Cervus Equipment Corporation (Cervus Equipment). The company had realized several significant accomplishments over the previous five years — Drake had never dreamed that Cervus Equipment would be approaching $1 billion in revenue!

Why, then, was he cautious about the future?

The company had accomplished so much over the previous nine years, growing from $56 million (in 2003) to $734 million. Profits had grown even faster than revenue. It was a good news story in the face of a global economic slowdown and a contribution to a proud legacy that had begun with the company’s founder, Peter Lacey. Customers were experiencing unprecedented growth amid a dynamic business environment. Shareholders were happy with the growth in their shares and dividends. Original equipment manufacturer (OEM) partnerships with John Deere, Bobcat, JCB, Clark, Peterbilt and others were stronger than ever. And Cervus Equipment had recently topped 1,200 employees.

However, Drake knew that to reach his board’s goal of $2.5 billion in revenue by 20201 — three times the current run rate — they would have to stretch both their business model and organization well beyond anything they had experienced to date. This would likely take them into new markets and new product and service categories and would require a much more focused innovation effort than they had experienced in the past. Could they achieve this growth and maintain the corporate values their employees had grown to embrace — the principles over policy approach and the practice of letting employees make critical decisions about customer needs and requirements. Could they continue to be seen as “local” by their customers, yet achieve the economies of scale in their operations they knew were needed to effectively grow their business? Could they continue to have close, meaningful partnerships with OEMs in an industry that was beginning to see a number of arguably revolutionary changes? Were they diversified enough, given the cyclical nature of the farming and construction industries and the relatively small geographic footprint they served in western Canada and New Zealand? Could they foster the leadership talent throughout the organization needed to achieve this level of growth? Could they continue to successfully acquire small equipment retailers at reasonable valuations that would enable acceptable payback periods?

1 This does not necessarily reflect the actual target, forecast or goal for the company at the time of publication; it is designed to complement the teaching goals associated with this case study.

These questions would all have to be carefully considered before Drake met with his board in April to prepare for the 2013 annual shareholder meeting. Board members expected him to present a new growth strategy for Cervus Equipment.

THE EARLY YEARS

The foundation for Cervus Equipment was a simple notion: that owners of John Deere farm equipment dealerships were nearing retirement and looking for viable succession opportunities. Second-generation owners had difficulty accessing the large amount of capital required to purchase dealerships and/or were not able to provide the level of leadership and management necessary to run the growing operations; given this, some dealerships were not performing at optimal levels. It became apparent that these types of owners were becoming interested in divesting their dealerships but not to just anyone. They cared not only about achieving a fair value for their businesses but also about selling to a reputable operator who would continue to dutifully service and respect the rural communities where they lived with their customers and employees. These factors amounted to a real opportunity for Cervus Equipment to execute its business plan by establishing a reputation built upon integrity and goodwill.

Cervus Equipment began as a partnership between Peter Lacey, Graham Drake and other owners of a few John Deere dealerships in the 1990s. At the time, they had no intention of managing these dealerships from a central organization. Rather, they believed that entrepreneurs with a material ownership position in the stores were in the best position to operate and grow these businesses. The model had no integration challenges, as no integration was required — until 1999, that is, when the business partners pooled their remaining dealership assets into the company, took it public2 and embarked on an aggressive consolidation-based growth strategy.

The second important element of their approach was the relationship with the OEM John Deere. They knew OEMs were usually treated as “suppliers” by dealers, and this could result in a business relationship that might become confrontational or contentious. Cervus Equipment recognized that a more positive “partnership” approach with OEMs would provide, among other things, opportunities to purchase dealerships with growth potential. After all, John Deere was knowledgeable about the relative market performance of all their dealers, was aware of opportunities for potential acquisitions and had final approval of all ownership transactions within their dealer network.

Lastly, Lacey and Drake knew that they wanted to represent premium brands in the markets they served. John Deere was by far the premium leading brand in the North American farming equipment industry, with industry leading technology and market share.

These three factors, when put together, provided a great foundation for Cervus Equipment’s business and growth strategy. Over the next 13 years, the company amassed 55 wholly or partially owned (via partnerships) equipment dealerships, with 36 representing John Deere in the agricultural industry. The remaining 19 stores represented construction equipment brands Bobcat and JCB, material handling equipment OEMs Sellick, Clark, Nissan Forklift and Doosan (forklifts, mulching, etc.) and, recently, long haul trucking manufacturer, Peterbilt (refer to Exhibit 1 for a timeline depicting Cervus Equipments’ growth path). Interestingly, Cervus Equipment was the only public company representing multiple stores in the John Deere dealer network.

Further consolidation of John Deere dealerships was, however, going to be more difficult for a number of reasons. First, historically, manufacturers were uncomfortable having one organization amass a large amount of scale over its dealer network in Canada, as this afforded dealership owners too much

2 As of 1999, Cervus Equipment trades on the Toronto Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol CVL.

bargaining power. For OEMs, the market risk of having too many of their dealerships in one basket was a legitimate concern, because OEMs expect proper coverage of assigned trade areas, and bigger territory equals higher risk. Secondly, Cervus Equipment had already acquired the majority of the low hanging fruit — the smaller, independently run dealerships. Remaining dealerships had already been consolidated into groups of five to nine stores. These more savvy organizations would likely cost more to purchase. Cal Johnson, vice-president Agriculture, dubbed this “round two of consolidation,” suggesting that “these would be more difficult to integrate from a cultural and leadership perspective.” Third, John Deere, at this point in time, was not entertaining Cervus Equipment expansion in the U.S. market, although this had not been ruled out for the future.

MAKING ACQUISITIONS WORK

Conventional wisdom suggests that up to 80 per cent of acquisitions fail.3 Consolidation via acquisition of small, independently owned businesses often fail to meet the required synergy targets crucial to realizing a reasonable return on the investment premium. Cervus Equipment leaders knew this, so they focused on the practical problems of achieving realistic synergies and avoiding integration failure.

They did this in a few ways. First, they built the organization around an employee- and customer-centric model using a value over policy approach that entailed decentralized decision making, that is, keeping key decisions as close to the customer as possible. These factors, coupled with a strong ethos of accountability applied to store managers (and employees), represented a unique approach in the industry. The traditional, smaller mom-and-pop dealerships, more often than not, were built on command-and- control management. Employees of newly acquired companies often experienced the Cervus Equipment approach first as frightening, then as enlightened.

Using this model to build positive change through new acquisitions was the primary focus. (Exhibit 2 illustrates the acquisition integration approach developed and successfully implemented by Cervus.) Within three months of an acquisition, the new store management team would present a growth strategy for the store, which they were then empowered to execute. This was wildly successful, with most stores achieving a significant growth in sales in their first year under the Cervus Equipment banner. As Randall Muth, the company’s chief financial officer, said:

We brought our acquisition integration timeline down from three years to eight months, including operational and cultural integration. This is an extraordinary achievement that has, among other things, enabled us to exceed our synergy targets with our recent acquisitions.

Second, Cervus Equipment was very patient in purchasing new dealerships (although the growth numbers would suggest otherwise). It would only purchase dealerships that were not performing to their current market potential (from John Deere’s perspective), or were located in a strong regional growth market, or both. This led to fair valuations at acquisition, followed by exceptional payback in 12 to 18 months.4

An abundance of investment opportunities at reasonable prices, combined with this successful integration model, helped Cervus Equipment to invest in more than 55 dealerships with $734 million in sales.

AGRICULTURE: A GROWTH INDUSTRY

The global agricultural machinery market was forecasted for accelerated growth, reaching over $102 billion by 2016 (up from $61.7 billion in 2011), with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.7 per

3 Rick Johnson, “Why 80% of all Acquisitions Fail,” Supply House Times, 49.2, April 2006, pp. 90-91.

4 The valuations were relative to the immediate growth opportunity in the market or in some cases the performance of the business relative to its current potential.

cent, according to MarketLine Analyst. Key markets would grow robustly, with Europe growing at 12.1 per cent, the Americas 8.7 per cent and Asia-Pacific 12.1 per cent. This would lead to Europe being the largest regional market, with a value of more than $41.9 billion. The Americas would be a close second, valued at $41.1 billion.5

In 2012, the farming industry in western Canada achieved unprecedented growth. Commodity prices for wheat, corn and soybean were at or near historic highs,6 and farming technology enabled increases greater than 20 per cent in crop yields. The future, it would seem, was full of potential. World population was predicted to grow 23 per cent by 2025, while arable farmland remained relatively constant. Global food production was expected to increase by 50 per cent over this same time, driven in part by significant increases in yield productivity enabled by new equipment technology, such as Site Specific Farming. While drought had been on the rise in arid regions of the world, its impact had not reached water-rich Alberta and Saskatchewan. Even in the United States, which had experienced a near record year of drought, farm income was expected to grow 3.7 per cent in 2012 to an unprecedented US$122 billion (the highest level since 1873 when adjusted for inflation).7 Overall U.S. farm cash receipts and balance sheets were at historically high levels, expected to reach US$400 billion in 2013, with debt-to-asset ratios of just 10 per cent.8 This drove the farm and garden equipment wholesale industry in the United States to a record high of US$55 billion, with farm-related equipment representing 75 per cent of this spend.

Regulatory changes were also having an impact on the industry. Recent changes to the Canada Wheat Board regulations now enabled (larger) farmers to market their product directly, essentially eliminating a wholesaler in the supply chain. Also, the legislated requirement for higher levels of bio-fuel in gasoline9 was driving a higher demand for corn acreage, with a high level of certainty for continued growth well into the future.

Additionally, interest rates were at an all-time low. This was important as a large portion of farmers preferred to acquire new equipment using loans or leases. U.S. farm equipment loans grew 3 per cent to US$7.1 billion in 2012. While leasing provided an opportunity to turn over farm equipment more often, thus increasing sales, it also presented a challenge to the dealerships, as they were tasked with profitably selling off used equipment.

Farming was also consolidating, with many industry insiders predicting “the death of the small farmer.” Crop yield increases, driven by scale and advanced farming technology, were making consolidation more attractive and viable for larger farms, advantages not available to smaller farms. The number of farms in Canada actually decreased 10 per cent to 205,000 farms in 2011, while the average size of farms grew 7 per cent to 778 acres. At the same time, the number of farms with sales greater than $1 million grew 31.2 per cent from 2006.10 These farms accounted for 49.1 per cent of farm sales. This was driving important changes and opportunities in the farm equipment business; large combine sales grew 7.3 per cent in 2011 to 2,899 units, while tractor sales only grew by approximately 2.0 per cent. Younger farmers, with bigger farms and more of a business mindset, were an important factor in this trend. These farmers preferred to purchase new combines every one or two years in order to access new, enhanced farming technology. Close to 3,000 new combines were being sold in Canada each year with a price tag from $250,000 to

$400,000. This also presented a challenge, as the used equipment inventories were growing and now

5 www.marketline.com/blog/the-global-agricultural-machinery-market-reached-a-value-of-61-7-billion-in-2011, accessed December 12, 2102.

6 Index mundi, www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=wheat&months=120, accessed December 20, 2012.

7 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444230504577617720338696432.html, accessed December 12, 2012.

8 “John Deere Committed to Those Linked to the Land,” Deere & Company, December 2012/January 2013, www.deere.com/en_US/docs/Corporate/investor_relations/pdf/presentationswebcasts/2012/roadshow_deck.pdf, accessed January 12, 2013.

9 Particularly in the United States.

10 Statistics Canada 2011 Census of Agriculture, www.statcan.gc.ca/ca-ra2011/, accessed December 10, 2012.

represented a significant financial risk to equipment dealerships. Year over year, the values of used combines diminished by 1.5 per cent.11 According to Lacey:

There’s been a bit of overzealousness by the manufacturers to get new product out the door. So there are lots of very, very competitive, multi-unit discounts and strong financial incentives to encourage new sales. We’re seeing a definite trend toward multi-unit deals, lots of trades and flips done every year. We don’t think flipping every year is a good strategy. The industry can’t absorb that much used, so you’re really stealing sales from the future and it’s going to come in one big crash if the industry doesn’t sort it out. Unfortunately, we all can talk about it and agree that it’s not sustainable, but it still happens.

Our preference would be for farmers to trade every two or three years where the owners make full use of the warranty period and get some hours on the equipment, especially combines. By rotating equipment every two or three years, the industry can absorb that; there are enough buyers of used for that.12

Refer to Exhibit 3 for further information related to changing trends in the agricultural sector.

John Deere was by far the premium producer in the North American market. Such a strong brand made running a John Deere equipment dealership easier from a sales and marketing perspective. Very little marketing and advertising was required on the local level, as many customers sought out the brand and had personal relationships with the dealers. As one senior executive put it: “Failure to run a successful [John] Deere dealership was a difficult task. You had to try hard to fail with this brand!” Also, the rural location of these dealerships meant local competition was not as strong, which ultimately drove gross margins on equipment sales and service to 17 per cent on average.

These factors positioned the industry for continued strong growth that was projected to exceed 5 per cent annually over the next five to eight years.

COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL EQUIPMENT

More recently, Cervus Equipment had focused on executing a diversification growth strategy in the construction and industrial equipment markets. The company purchased and operated a number of construction and materials handling equipment dealerships that sold globally recognized brands such as Bobcat, JCB, Clark, Nissan Forklift, Doosan, Sellick and, most recently, Peterbilt trucks. With the continued aggressive growth in the oil and gas industry in western Canada, these dealerships were exceptionally well-positioned. Construction investment for non-residential construction and machinery and equipment had grown from $55.3 billion in 2009 to $84.1 billion in 2012 in Alberta alone.13 (Refer to Exhibit 4 for information related to growth in Alberta’s construction industry.) In the United States, the rental and leasing of equipment represented combined annual revenue of US$45 billion in 2012, with 50 companies accounting for more than half of the revenue.14 Residential construction in Alberta also

11 Ag Equipment Intelligence & Cleveland Research, www.farm-equipment.com/pages/Spre/Forecast-&-Trends-Used- Equipment-Pricing-Slips-As-Inventories-Climb-August-6,-2013.php, accessed December 8, 2012.

12 Dave Kanicki, “The New World of Used Equipment,” June 2012, www.farm-equipment.com/pages/In-this-Issue-June- 2012-Showcase-The-New-World-of-Used-Equipment.php, accessed December 8, 2012.

13 2009 is actual investment, while 2012 represents intended investment. “Q4 2012 Investor Presentation Rocky Mountain Dealerships,” p. 27, http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/RMD/2671480266x0x616170/2BA5C25E-00AC-4475-A4D3- 4FDA3487D262/Q4_2012_RMDI_Investor_Presentation.pdf, accessed March 1, 2013.

14 First Research — Commercial & Industrial Equipment Rental & Leasing. October 22, 2012. www.mergent.firstresearch- learn.com/industry_full.aspx?pid=297, accessed December 12, 2012.

continued to boom, with 19.4 per cent increase in housing starts in 2012. These dealerships were clearly positioned for strong continued annual organic growth in the 5 to 10 per cent range.15

The global construction and equipment market was expected to reach US$192.3 billion by 2017, up from US$143.6 billion in 2012, growing at 6.0 per cent CAGR.16 China was forecast to represent the majority of global construction equipment consumption. India was also expected to grow through multi-billion dollar expenditures in building power plants, telecommunications, ports and roads, with 21 per cent annual growth expected through 2015.17 Material handling equipment was forecast to grow to US$100 billion by 2015.

Much like the agricultural dealership network, the remaining dealerships available in this sector tended to be larger multi-store operations that had already been through a round of regional consolidation. These would be more difficult to purchase, likely demand a larger premium and thus require a stronger effort to achieve synergies and a more focused integration process to realize the payback period Cervus Equipment shareholders expected. On the positive side, there was much more room to grow within these sectors, especially with Peterbilt, whose managers had expressed an interest in having Cervus Equipment grow within their dealer network, with potential for future expansion in the northwestern region of the United States.18

INTERNAL CHALLENGES

Cervus Equipment had seen its organization grow from 176 employees in 2003 to more than 1,200 in 2012. The company wanted to maintain its value-based employee model, but the new opportunities drove a need to build in centralized services for the dealerships in order to drive efficiencies in areas of the business such as parts sourcing, finance and human resource management. Cervus Equipment leaders also did not want to forego the strong entrepreneurial philosophy that ensured that decisions were made as close to the customer as possible, which had proven a very effective approach; now, however, it was proving difficult as they purchased dealerships run with a completely different management philosophy, that is, command-and-control by the owner. On top of this, they were finding it progressively more difficult to find leadership candidates in sales, service, parts and dealership management positions. They required leadership at the dealership level that, among other things, came from the farming community, people who understood the challenges customers were facing. These kinds of employees were becoming increasingly difficult to find. To address this problem, they created Cervus Leadership University (CLU), an internal leadership development initiative.19 Although very promising, CLU could not immediately address the significant current leadership gaps within dealerships. A large number of positions were currently unfilled, with a number of them at the dealership management level. Because of this, the Cervus Equipment leadership team was cautious about seeking out large new acquisitions before CLU was able to grow a strong foundation of new leadership talent. The general manager of the Agriculture division, Sheldon Gellner, stated, “when you stretch an elastic, you can see where it begins to fray along the edges before it breaks. Cervus’s edges are fraying like this and if we stretch it too much further, it may just break!

15 Six of the Best, ConstrucionWeekOnline.com, www.constructionweekonline.com/article-24031-six-of-the-best/1/print/, accessed September 9, 2013.

16 Associated Equipment Distributors, www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/construction-equipment-market-will-reach-usd- 1923-billion-globally-by-2017-transparency-market-research-183321381.html, accessed December 12, 2012.

17 RNCOS Industry Research Solutions, www.rncos.com, accessed February 10, 2013.

18 OEMs in this market had traditionally been resistant to cross-border dealer ownership among dealership consolidators.

19 Currently more than 100 Cervus Equipment employees were participating in this leadership development program; Cervus Equipment 2012 Annual Report.

Since the company followed a decentralized management model, it was perhaps not surprising that they had not finely tuned centralized processes, functions or information technology (IT) systems. This became an issue as the organization grew. Supporting the dealerships were multiple IT systems of varying vintages with related and formidable maintenance and evolution requirements. Only recently had the company leaders integrated some aspects of the parts supply chain. While opportunities for continued centralization of services within the organization were abundant, the efforts to seize these opportunities played second fiddle to the primary focus on integrating new acquisitions.

OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Cervus Equipment was performing near, or slightly above, industry levels. Gross margins in the agricultural industry stood at approximately 17 per cent. In the forklift and materials handling industry, gross margins averaged 34.6 per cent, while in the construction industry they came in around 22.5 per cent. However, given the size and potential for achieving economies of scale (in a fragmented industry), analysts continued to expect better than average results from Cervus Equipment; performance at the industry standard was considered below its potential given the strength of its business model and management team. (Refer to Exhibits 5, 6 and 7 for financial results and performance across business segments.)

Cervus Equipment had yet to implement the sales competencies its leaders believed were needed to achieve future growth success in the construction and industrial side of the business. This was clearly a more competitive business segment. Cross selling across brands in this segment represented a strong growth opportunity, yet it was somewhat elusive. John Higgins, vice-president of the Commercial & Industrial department, said:

We are committed to build best-in-class sales management and market penetration competencies within the construction and industrial segments of our business. This will enable us to more deeply penetrate the oil and gas sector with a broader range of solutions, from construction through to materials handling. Our vision for this is clear; however, we are a long way from achieving this goal.

INTERNATIONAL EXPANSION

In 2009, the leadership team was invited by John Deere to visit a number of dealerships in New Zealand to explore possible partnership opportunities. Cervus Equipment’s founder and CEO at the time, Peter Lacey, went to New Zealand to investigate. He saw these dealerships as a great opportunity for immediate consolidation under the Cervus Equipment model and concluded deals to purchase them on the spot.20 Thereafter, Cervus Equipment moved to consolidate 10 John Deere dealerships in New Zealand, becoming an international company in the process. However, the transition from regional player in Canada to international firm proved challenging. The company did not fully understand the complexity and difficulties of running dealerships halfway around the world and the complexity related to achieving integration synergies associated with the New Zealand investments. Implementing Cervus Equipment’s decentralized management philosophy in New Zealand was accomplished by working closely with stores to find key synergies the company could implement to improve store performance; senior managers were eventually moved to New Zealand full time to lead this integration process. In addition, there are significant differences in the agricultural market in New Zealand versus western Canada. For example, the majority of farms in New Zealand are smaller and tend to buy smaller, higher margin tractors and equipment that is not replaced as often. Thus, overall margins are higher but volume is lower, resulting in

20 This is representative of Cervus Equipment’s acquisition strategy: it was rarely planned and very opportunistic. When opportunities presented themselves, the company was prepared to embrace them and move quickly when required.

used equipment sales representing a bigger challenge. Moreover, the centralized services Cervus Equipment built for western Canada just didn’t translate well to New Zealand. By collaborating closely with the New Zealand store level management team to pick and choose the best practices to support their operations, Cervus Equipment progressed with the New Zealand stores but admitted that it had work to do before these would contribute in a material way to the company’s overall growth targets. These investments in New Zealand ultimately provided Cervus Equipment with an opportunity to develop a greater understanding of the differences in international markets and new cultures.

Undaunted, the company embarked on a less risky partnership in 2012 through Windmill AG as a minority investor in five John Deere dealerships in Australia. Although Cervus Equipment was a non- controlling stakeholder in these dealerships,21 its leaders viewed this as an opportunity to stick a toe in the Australian market, which many thought ripe for consolidation. Australia represented a market growth opportunity equal in size to that of Cervus Equipments’ Canadian market. That being said, Cervus Equipment managers were not so naïve as to believe they could jump into the Australian market and achieve instant success with their Canadian business model — a lesson the New Zealand experience had painfully taught them. The experience in New Zealand made the board and senior management somewhat cautious about expansion in Australia.

More recently, John Deere had invited Cervus Equipment to Russia as a prelude to having it purchase some underperforming dealerships in Eastern Europe. Titan Machinery, a competitor, had begun to expand in this fashion in the Balkans, exploiting a close relationship with Case Construction, a primary supplier of construction and farming equipment. While these represented opportunities for potential expansion and growth, Cervus Equipment quickly concluded that the political and legal environment in these countries had yet to mature to the point where acquiring businesses would be considered a reasonable risk. The experience in “safe” New Zealand had not been satisfactory, and the challenges in Eastern Europe would likely be tougher.

John Deere was also very focused on building a market in Brazil, one of the largest growing economies in the world. Once again, it invited Cervus Equipment to join it on a visit. This was indeed an interesting opportunity, but John Deere was rightfully pursuing a slow and methodical approach to brand building in this market that would take years to unfold. Jumping in now would ensure great growth opportunities for Cervus Equipment in five to 10 years time, but it offered few immediate returns.

COMPETITORS

Cervus Equipment had two primary competitors who were executing similar growth strategies: Rocky Mountain Equipment (RME) in western Canada and Titan Machinery (Titan) in the United States. Both companies had strong ties with the OEM Case Construction.

RME was, in fact, bigger than Cervus Equipment and represented reputable international brands such as Case Construction and Case IH (New Holland) in agriculture. With more than $1 billion in revenue across 39 locations in western Canada, RME amounted to a formidable competitor. The company had grown very quickly from 12 dealerships in 2007. Its range of products in the construction industry was better positioned to take advantage of the oil and gas boom in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Because its growth, which occurred much more quickly than Cervus Equipment’s, resulted in lower margins and bigger consolidation challenges, market analysts were hesitant to support it and seemed to be waiting for the company to rationalize its dealerships and operations. This resulted in a market valuation much lower than Cervus Equipment’s (on 25 per cent higher revenues), which spoke well of that company’s business model, leadership and execution capabilities.

21 Cervus Equipment owned 35 per cent of Windmill AG Pty Ltd.

Titan represented a diversified mix of agricultural, construction and consumer product dealerships across the U.S. upper Midwest. Headquartered in Fargo, North Dakota, the company had 104 North American dealerships and 12 European dealerships in 2012. It also represented Case IH, Case Construction, New Holland and New Holland Construction. Titan went public in 2007 and had since grown to an estimated FY2013 revenue of US$2.0 billion to US$2.15 billion.22 This represented a greater than 35 per cent increase over FY2012. Some store sales were growing 19.2 per cent with gross profit margins at 14.8 per cent.23 Titan had no intentions of venturing into Canada, but it was a force to be reckoned with in the U.S. Midwest. However, its current inventory of used equipment was at an all-time high of US$1.05 billion and represented its toughest business challenge. With inventory turn ratios at historic lows of 1.5 times annually,24 this issue had the potential to ruin the company. Titan was buoyed by the growing energy sector in North Dakota and the related construction industry growth. It had also turned its attention to growing its business in Eastern Europe.

Refer to Exhibit 8 for a basic financial comparison of these organizations.

THE DEALERSHIP OF THE FUTURE

The farm equipment business was not what it used to be, having been truly revolutionized in the last 10 years. The industry was being driven by the requirement to continue to increase crop yield productivity to feed a growing world population with little new arable land. To meet this demand, the industry evolved farming technology in the direction of Site Specific or Precision Farming, which was:

a system to better manage farm resources. Precision farming is an information and technology based management system now possible because of several technologies currently available to agriculture. These include global positioning systems, geographic information systems, yield monitoring devices, soil, plant and pest sensors, remote sensing, and variable rate technologies for application of inputs.25

This change was described as a revolution in farming techniques and technology. For example, the application of fertilizer or seed could be manipulated to the centimeter with enhanced GPS-controlled information systems linked, in real time, to tractor technology. With this revolution, there was pressure to change the fundamental services provided through farm equipment dealerships and their OEM suppliers. For example, dealerships would be expected to have some expertise in agronomy, data management and analytics. IT had moved to the forefront of farming, with all the complexities that came with it.

To better position itself in this space, Cervus Equipment invested in a small company called Prairie Precision Networks, which had a real time kinetics (RTK) product that enabled GPS devices to build accuracy to one centimeter.26 Cervus Equipment also partnered with Agri-Trend, a farming data analytics and consultancy company, through a joint venture investment.

This growing technological change also introduced new business challenges to and added pressures on farmers. They would spend less time in their fields and more time managing crop yields, capital

22 FY 2013 ends March 31, 2013, Titan Machinery Fiscal Third Quarter 2012 Earnings Conference Call, December 6, 2012,

http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=214897&p=irol-calendarPast, accessed December 12, 2012.

23 Titan was rated #66 in Fortune’s Fastest-Growing Companies (September 2012). www.farm-

equipment.com/pages/Industry-News-Titan-Machinery-Ranks-66-on-Fortunes-100-Fastest-Growing-Companies-List.php, accessed December 12, 2012.

24 Down from 3 per cent in January 2011 (Seeking Alpha). More Downside For Titan Machinery; October 31, 2012, www.seekingalpha.com/article/965261-more-downside-for-titan-machinery, accessed December 12, 2012.

25 University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Tifton GA. www.nespal.cpes.peachnet.edu, accessed December 12, 2012.

26 Regular GPS is usually only accurate within a metre or so and thus is not good enough for site specific farming applications.

investments, human resources and bottom lines. By default, this moved the focus in dealerships from traditional sales and service to account management and solution-based selling. The conversation with farmers evolved from how many tractors and related implements they needed to what equipment and services they required to produce a target crop yield (and margin) across current acreage. Dealer services now had to include operator training, optimization, yield data management systems (and benchmarking), human resource management, analytics and information management. Their business model was also changing. How do you make money in this new world? Clearly it would not be on the backs of equipment and parts sales alone.

In fact, when faced with the question of what a dealership of the future should look like, the answers were equally diverse and vague. This was not an easy question to answer. One thing that was certain was that Cervus Equipment was going to need to build and execute an innovation strategy both within and outside its OEM partners. John Deere was a leader in farm equipment technology, but it wasn’t necessarily leading the way in introducing site-specific farming technology. It tended to be more conservative when it came to releasing new products and services under the Deere banner. Cervus Equipment understood this and thus would pursue its desire to move forward in site-specific farming through separate investments and partnerships. Investing in this new level of knowledge and service delivery at its dealerships while growing the number of dealers was a tall order. There was only so much time and capital available within the firm. Gellner discussed this notion:

We can utilize our limited resources to grow our product and service capability to our clients and optimize our operational requirements (like investing in IT systems for just-in-time parts management or used equipment sales solutions) OR we can fund and integrate new acquisitions. Clearly we have chosen in the past to fund growth through acquisitions, but we cannot continue to do this to the detriment of the services available to our customers or our back end systems and processes.

The senior team realized that the dealership of the future would be quite different from those they were running today. How to get there was a deeper, more perplexing question that could not be ignored and would certainly tie up valuable resources in the very near future.

THE NEXT PHASE OF GROWTH

Drake knew one thing for certain: the next phase of growth for Cervus Equipment would make the last few years look easy. On the one hand, he had concerns about which direction the company should choose to grow and how it was going to muster the resources to execute such an ambitious plan while maintaining strong financial performance. He knew that the current approach, while previously successful, would not get the company to its future revenue goal. He also knew the company would need to begin investing more aggressively in its current dealerships to support them as they evolved into the dealerships of the future. On the other hand, he knew that Cervus Equipment was fortunate to be in such a strong financial position in such a robust market and had the solid and reliable relationships it had built with its OEM partners, like John Deere and Peterbilt. Graham also had great confidence in his current senior leadership team to execute a new growth strategy.

This would be the plan that would define his era of leading Cervus Equipment.

EXHIBIT 1: CERVUS EQUIPMENT GROWTH TIMELINE

Source: Company files.

EXHIBIT 2: ACQUISITION INTEGRATION MODEL AT CERVUS EQUIPMENT CORPORATION: ACQUISITION, INTEGRATION, STRATEGY AND CULTURE BEST PRACTICE

SWOT — Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities & Threats KPI — Key Performance Indicators

NPS — Net Promoter Score Source: Company files.

EXHIBIT 3: FARMING INDUSTRY

Source: Rocky Mountain Equipment 2012 Q4 Investor Presentation, pp. 9-

10, http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/RMD/2671480266x0x616170/2BA5C25E-00AC-4475-A4D3-

4FDA3487D262/Q4_2012_RMDI_Investor_Presentation.pdf, accessed September 9, 2013.

EXHIBIT 4: ALBERTA CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

Source: Rocky Mountain Equipment 2012 Q4 Investor Presentation, pp. 27,

14, http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/RMD/2671480266x0x616170/2BA5C25E-00AC-4475-A4D3-

4FDA3487D262/Q4_2012_RMDI_Investor_Presentation.pdf, accessed September 9, 2013.

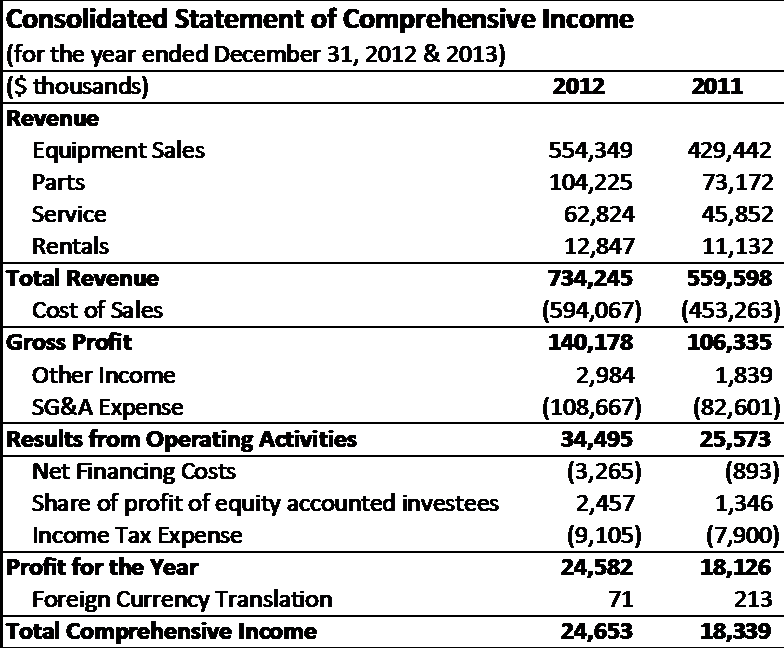

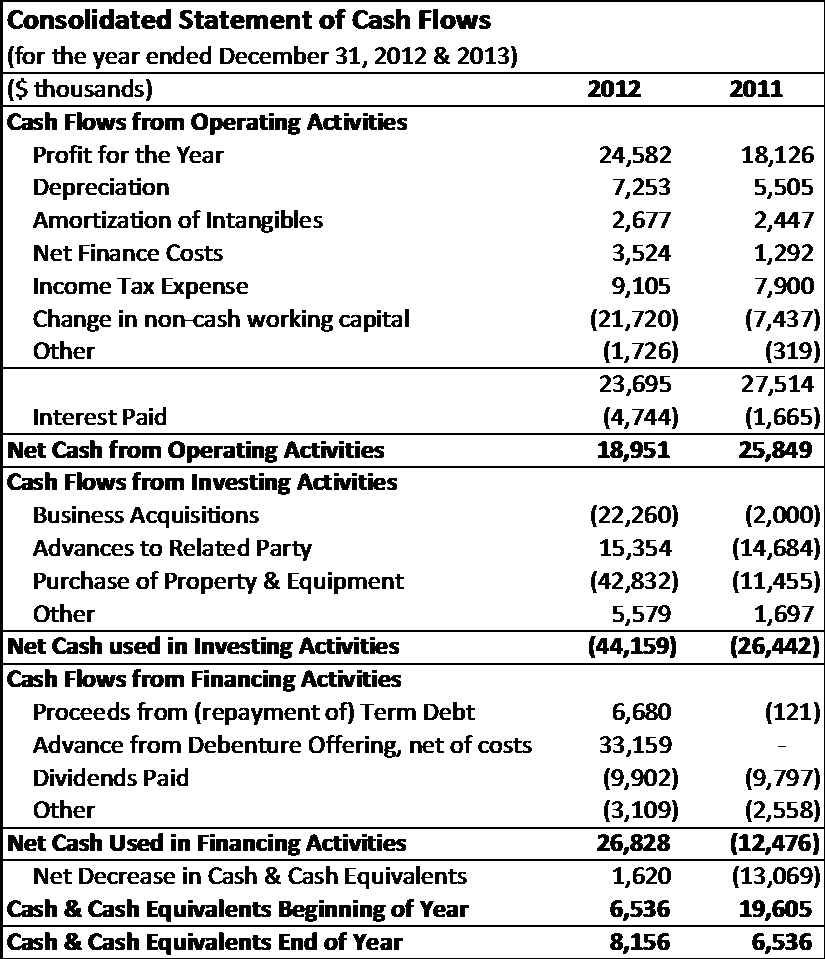

EXHIBIT 5: CERVUS EQUIPMENT FINANCIAL SUMMARY

Accounts Receivable

EXHIBIT 5 (CONTINUED)

Source: Cervus Equipment Corporation Annual Report 2012.

EXHIBIT 6: SUMMARY FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE INFORMATION

Source: Cervus Equipment Corporation annual Report 2012.

EXHIBIT 7: CERVUS EQUIPMENT REVENUE BREAKDOWN

Source: Cervus Equipment Corporation Annual Report 2012.

EXHIBIT 8: COMPETITOR COMPARABLES

Clearly Cervus Equipment price to earnings (P/E) ratio reflects a higher confidence from the Canadian market in their business strategy and approach. Cervus Equipment senior leadership believes this is tied to their principles over policy management philosophy, among other things.