Write a history paper. Details in the files attached

Inventing an Industrialized Canada

Note:

| | The first part of the lecture notes is written out for you to read (with links to additional, or illustrative information that you may click if you wish). The second part includes movie clips from McCord Museum online that you are to view (a compulsory not optional component of the lecture notes). To view a clip click on the link icon (illustrated at left) beside its title. |

Part I

THE IDEA BEHIND THE DREAM

Mechanization Mania

Worldwide, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (approximately 1870 to 1920), the idea that a better future could be achieved by industrial means was all-pervasive. “Industrialize” was the economic buzzword of the age. The thinking was that an industrial country would increase its output through mechanizing its manufacturing processes (see Fig. 5.0). Industrialization was desired because it was believed that any nation that achieved it would reap wealth and ease.[1]

Fig. 5.0 Mechanized match-making.Photograph,“Eddy’s Match Dipping Machine,” dated 1885, Hull, Quebec. Source: William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada/PA-, Mikan No. 3372746 [Restrictions on use: Nil. Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.0 Mechanized match-making.Photograph,“Eddy’s Match Dipping Machine,” dated 1885, Hull, Quebec. Source: William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada/PA-, Mikan No. 3372746 [Restrictions on use: Nil. Copyright: Expired].

What does/did industrialization mean?

A first step in understanding what Canadians were imagining their country might become if it were industrialized, is to examine what the term industrialization was supposed to mean between 1870 and 1920. This step actually requires some research.

If you look for a definition—online for example—you will find that industrialization is not a particularly well defined word. It has multiple, mostly similar, but somewhat variable meanings. See, for example, "Industrialization,” OneLook Dictionary Search.

The basic premise, as formulated in the 18th and 19th centuries, was that industrialization marked a distinct, large scale transition in the history of Human Civilization (which was a history of progress—societies that made the transition to an industrial society were at the top of an evolutionary ladder).

Primitive Man ("Uncivilized") [2]

Agricultural Man ("Civilized") [3]

Industrial Man ("Superior") [4]

Table 5.0 Theorized Major Transitions in Human Civilization.

Generally, industrialization seems to refer to a very large scale transition from an agrarian (dependant on farming) to an industrial (dependent on industry) world (see Table 5.0). But, to be clear on past ideas, we then have to ask what “industry” means.

See, for example, "Industry,” Thesaurus.com.

Industry, apparently, might mean “manufacturing” or just “hard work,” which doesn’t explain why the hard work of farmers is not regarded as something the industrializing world of the past and the industrialized world of the present depended on as much as the pre-industrial but “civilized” world that existed before. (One might wonder, for example: could the scale of manufacturing have expanded during a prolonged food shortage? And isn’t there such a thing as “industrial agriculture”?)

There are a couple of historical reasons for the term industrialization having such a hazy definition. One reason is that the word is relatively new.

a) Etymology (the history of the word)

It is possible to find the word industrialization in late nineteenth-century sources. [5] However, adding the suffix “ation” to the word “industrialize” did not become commonplace until after about 1906. In turn, industrialize had only become a word after about 1852 when “ize” was added to “industrial” (a word that dates to the French term industriel used as early as 1774 and related to the concepts of systematic diligence and effort in trade or manufacture—see Fig. 5.1).[6]

Fig. 5.1 An example of systematic diligence. Unknown photographer, “Canada’s earliest Industry. Colin Fraser, trader at Fort Chipweyan, sorts fox, beaver, mink & other precious furs,” dated to the 1890s. Source: Library and Archives Canada/C-001229 [Restrictions on use: Nil. Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.1 An example of systematic diligence. Unknown photographer, “Canada’s earliest Industry. Colin Fraser, trader at Fort Chipweyan, sorts fox, beaver, mink & other precious furs,” dated to the 1890s. Source: Library and Archives Canada/C-001229 [Restrictions on use: Nil. Copyright: Expired].

As the photograph above shows, the "systematic diligence" version of industry was still practiced in Canada without the benefit of machines during the period we are considering—though such industrious pursuits were generally regarded as more properly belonging to the past than to an industrializing country’s present.

b) Epistemology (the study of knowing what the word means)

A second reason for the hazy definition of industrialization is the history of how it has been studied. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “industrial” was a buzzword that was only loosely defined, probably because the meaning seemed clear to those who used it.[7] Scholars, analysts, and historians of the time, as well as those of subsequent decades in twentieth century, did not rush to define either industrial or industrialization. Perhaps partly because they assumed that they already knew what the words meant, they instead concentrated on describing what industrialization as a process looked like, and on positing theories about why it would take place.

For a Canadian take on a definition of industrialization as the term applies to Canadian history see: “Industrialization” The Canadian Encyclopedia.

For an overview of how Industrialization is usually described in Canadian historiography see “Excerpts from history textbooks: Industrialization,” EduWeb, McCord Museum.

It wasn’t until the end of the twentieth century that a re-evaluation of historical descriptions revealed that industrialization was not as clear cut and explainable a phenomenon as had been previously assumed.[8] And yes, part of the problem was the lack of a clear definition of the word itself.

c) Working Definition

For this course we need to share some common concept of what is meant by the term industrialization, so that we can try to understand what Canadians involved in inventing Canada from 1870 to 1920 were trying to accomplish and why. I have therefore defined the concept as follows:

For the purpose of this unit, if a past country, region, city, or nation is said to have promoted industrialization, we mean that they emphasised industrial progress as the means not only of sustaining their society but of improving standards of living. By industrial, they meant that labour applied to producing things should not be solely human and animal muscle-powered. Instead, production should incorporate the latest in scientific developments and use new technologies driven by alternate sources of power (such as coal-fired steam and electrical engines).

Note that the above definition emphasizes what people of the period thought.

What the prime minister thought: BY 1870: INVENTING AN INDUSTRIOUS AND INDUSTRIALIZED CANADA THROUGH ECONOMIC POLICY

Faced with an economy that was stalling in the newly confederated Dominion of Canada, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald (in office from 1867-1873, and 1878-1891) promoted a three part plan to industrialize the country, with each part dependent on the others:

Increase government funding to speed the completion of trans-continental railways:

To help create a national market, and to support the Canadian mining industry (including coal); factories that made iron rails, spikes, and spars for bridges etc.; and manufacturers of a myriad of other necessary items (from worker’s shoes to upholstered cushions for passenger cars. See Fig. 5.2). [9]

Fig. 5.2 “Grand Trunk Railway dining car interior, n.d. The fittings and decor of this dining car, built for the Grand Trunk in 1893, illustrate the elaborate fashion of the period.” Source: William Notman/Library and Archives Canada/C-046482 [Restrictions on use: Nil; Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.2 “Grand Trunk Railway dining car interior, n.d. The fittings and decor of this dining car, built for the Grand Trunk in 1893, illustrate the elaborate fashion of the period.” Source: William Notman/Library and Archives Canada/C-046482 [Restrictions on use: Nil; Copyright: Expired].

Impose high import tariffs (taxes) on goods manufactures outside Canada:

To support the establishment and growth of industrial factories in Canada (Canadian-made products would be the cheapest available for purchase in Canada).

Note: This policy was advocated as early as 1867. Therefore the factories that would benefit were those of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

View the Confederation dates for the provinces and territories in Canada.

View: “Map of Canada in 1867,” Library and Archives Canada. (Note geographical change compared to previous units).

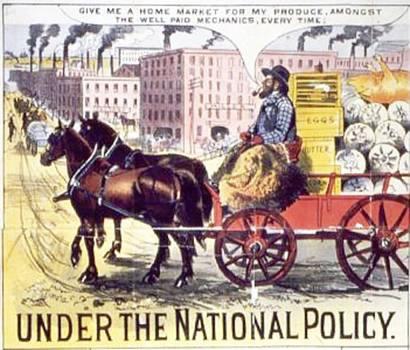

Fig. 5.3 Election poster, detail, showing agrarian support for industrialization. Under the National Policy – 1891 electoral campaign. Unknown Artist, source: National Archives of Canada, C-95470, Acc. No. 1983-33-1115. Author unknown. Copyright: Expired

Fig. 5.3 Election poster, detail, showing agrarian support for industrialization. Under the National Policy – 1891 electoral campaign. Unknown Artist, source: National Archives of Canada, C-95470, Acc. No. 1983-33-1115. Author unknown. Copyright: Expired

Encourage immigration to Western Canada:

Import immigrant farmers to exploit the immense western territories newly acquired in 1870 (while at the same time “civilizing” the so-called”primitive“ people who were already there[10]).

View: immigration pamphlets advertising farming prospects that were readily available via Canadian railways to the West.

View: ”Map of Canada, 1870,“ Library and Archives Canada. Note geographical change since 1867.

The railway would bring immigrant farmers to the West and ship their grain to ports in Eastern Canada (see fig. 5.3). The tariffs on manufactured imports would protect fledgling Canadian industries from competition (particularly from American producers). Immigrants would build the railways, establish the farms, and buy the Canadian-made goods. The government would finance the railway with funds collected from the import tariff.

Dubbed the "National Policy," Macdonald’s plan served as the framework of Canadian development over several decades.

“National Policy,” Canadianencyclopedia.com (accessed 20 May 2013).

Link to speech, “1878: John A. Macdonald Moves His National Policy in the House of Commons.”

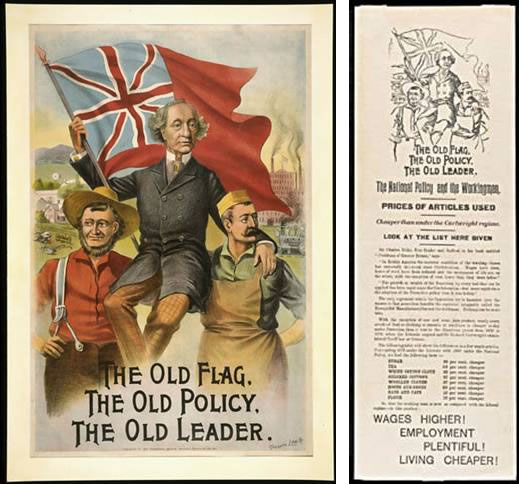

Figures 5.4 and 5.5 Pro-industrialization Campaign Posters with John A. Macdonald’s slogan, “The Old Flag, The Old Policy, The Old Leader.” Equal benefits are promised to working Canadians in the most famous graphic image of the election of 1891. Macdonald, the "Old Leader,” is carried on the shoulders of a farmer and an industrial worker (note their places of work in the background), as though he were a hero on a winning team. Macdonald and the Conservative Party won the election (although Macdonald died a few months later).

Fig. 5.4: Unknown artist, colour lithograph, “The Old Flag - The Old Policy - The Old Leader [Sir John A. Macdonald]: 1891 electoral campaign,” dated 1891. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan no. 2834401. [Copyright: Expired]

Fig. 5.5: Unknown artist, broadside, “The Old Flag, the Old Policy, the Old Leader: The National Policy and the Workingman, 1891.” Source: Library and Archives Canada, Collections Canada, nlc-14247. [© Public Domain (Copyright: Expired)]

The results from the 1891 election suggest that a majority of the Canadians who were eligible to vote supported Macdonald’s idea of an industrialized Canada (see Figs. 5.4 and 5.5), but it is worth remembering that "The franchise (right to vote) was granted only to males over 21 who owned or had the use of a substantial amount of property. ... The electoral candidates tended to be members of the top echelon of this propertied electorate."[11]

On the composition of the politically and economically elite among Canadian men of the time see Unit 5, Reading 1: T.W. Acheson, “Social Origins of the Canadian Industrial Elite, 1880-1910.”[12]

![Write a history paper. Details in the files attached 6]() Fig. 5.6 Elite Fashion for Industrious Men ca. 1870

Fig. 5.6 Elite Fashion for Industrious Men ca. 1870

Edward Minister and Son, illustration, Gazette of Fashion and Cutting-Room Companion, (London: 1871), [Google Books full view [copyright expired], Public Domain. (accessed 10 December 2010).[13]

WHAT THE POLITICALLY AND ECONOMICALLY ELITE MALES OF CANADA THOUGHT: ECONOMIC OPTIMISM, BOOSTERISM, AND PROMOTING AN INDUSTRIAL CANADA

The Theory behind Economic Optimism

Macdonald’s National Policy was not invented out of thin air. It reflected current economic theory and was based on observations that linked together a particular cause and effect. The model observed was Britain—the preeminent example of a wealthy and powerful empire.[14] The British were the first nation to undergo widespread industrialization. Britain’s superior position worldwide was therefore assumed to rest on that factor (see Table 5.1).[15]

The Theory:

Follow the British example, attain a similar outcome

industrialization > economic growth > superior status worldwide

cause ---------------------> effect

Table. 5.1 The Industrial Effect based on the British Model.

In other countries, including Canada, people assumed that by imitating the British example they would attain a similar outcome. This imitation included following the British practice of turning to professional planners and relying on expert know-how (it was the scientific thing to do).

The optimistic among the science-minded (and economics was considered a science[16]) argued in favour of investing in projects that supported industrialization, because by doing so societies would reap certain benefits (see Table 5.2).

The Logic of Industrial Benefits

Benefits for the Nation as a Whole:

Benefits of Industrialization Equation

Increased consumer purchasing at home

+

Increased international trade abroad

=

A wealthier nation

Table. 5.2 The Equation for Industrial Success

Benefits for the Workforce in Particular:

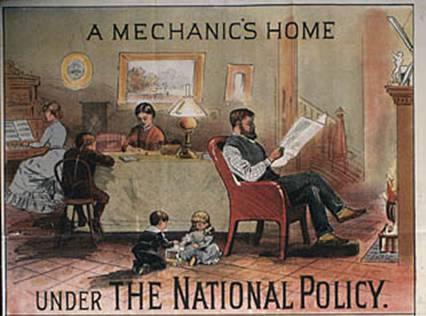

One segment of the population that was promised a large share of the benefits of amassing national wealth was the working class (see Fig. 5.7).

Fig. 5.7 The Industrial Promise to the Working Class. Unknown artist, detail of election poster, "A Mechanic’s Home Under the National Policy," dated 1891. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-33-1117 [Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.7 The Industrial Promise to the Working Class. Unknown artist, detail of election poster, "A Mechanic’s Home Under the National Policy," dated 1891. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-33-1117 [Copyright: Expired].

The logic of industrialization held that an industrialized, wealthier nation would have a healthier population. There would be a stronger, more efficient workforce with better places to live and better educations. In these conditions workers would no doubt be better behaved, because happier, and therefore more inclined to work according to the standard set by (scientifically minded) management.

Benefits for Urban Development:

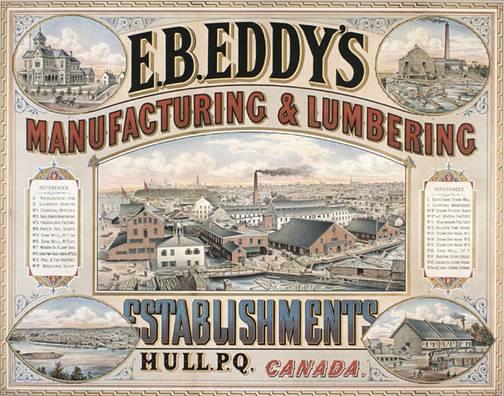

Fig. 5.8 Illustration showing an industrial factory as an integral part of a cityscape. J.H.B., lithograph, "E.B. Eddy’s Manufacturing & Lumbering Establishment, Hull, P.Q.: advertisement poster for E.B. Eddy. ca. 1884." Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan no. 2834406 [Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.8 Illustration showing an industrial factory as an integral part of a cityscape. J.H.B., lithograph, "E.B. Eddy’s Manufacturing & Lumbering Establishment, Hull, P.Q.: advertisement poster for E.B. Eddy. ca. 1884." Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan no. 2834406 [Copyright: Expired].

Logic also dictated that the majority of happy workers would live in urban centres, to be near the machines in the industrial factories (see Fig. 5.8).

Fig. 5.9 The Old: A water-powered mill in a pastoral setting. Joseph Bouchette, watercoulour, “Woolen Factory, Sherbrooke in the Eastern Townships, Lower Canada. ca. 1836.”. Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1993-345-3 [Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.9 The Old: A water-powered mill in a pastoral setting. Joseph Bouchette, watercoulour, “Woolen Factory, Sherbrooke in the Eastern Townships, Lower Canada. ca. 1836.”. Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1993-345-3 [Copyright: Expired].

Canada was a relatively large new creation, with most of its territory still in its original, natural state (see Fig. 5.9). Its resources were considered to be a source of potential wealth. Because cities were viewed as the conduits in which raw materials were converted to money by sending them into the international trade system, urbanization—the creation of wealth producing cities—was the goal. The logic: take a town and make a city out of it—with factories full of workers (men, women, and children) producing products. The more you made, the better off you would be.

The Logical Progression in an Industrializing Country

Have a resource.

Build a factory for refining the resource.

Build a town around the factory for the workers.

Produce refined product to ship for trade on the home and international market.

Watch the town develop into a city.

Table. 5.3 Setting the stage for the development of urban centres.

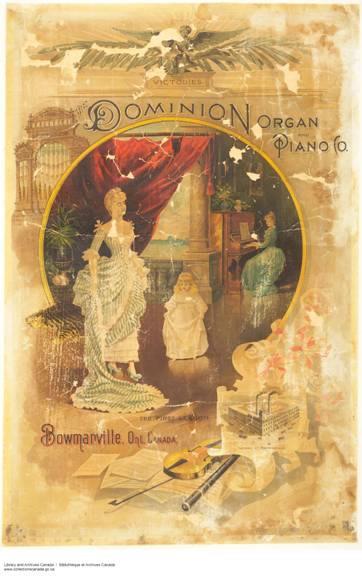

Thus, the theory held, as wealth accrued, towns would expand to become cities (see Table 5.3): factories would grow larger and more numerous requiring more workers to be housed nearby; more workers with more wages to spend would require access to more stores, schools, and services; extra and ambitious sons and daughters raised in the countryside would migrate to the towns and cities to work and raise their own families (see Fig. 5.10).

Fig. 5.10 The New: note that the factory emitting smoke (inset detail, lower right side of the poster) is presented as the source of refinement in an extremely comfortable, industrial era home. Unknown artist, lithograph poster, “The First Lesson: The Dominion Organ and Piano Company [Toronto],” dated ca. 1878-1909. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. R1409-35 [Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.10 The New: note that the factory emitting smoke (inset detail, lower right side of the poster) is presented as the source of refinement in an extremely comfortable, industrial era home. Unknown artist, lithograph poster, “The First Lesson: The Dominion Organ and Piano Company [Toronto],” dated ca. 1878-1909. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. R1409-35 [Copyright: Expired].

Every self-respecting nation desired large cities because they were proof of successful industrial development (in keeping with the British model).

THE METHOD: PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

As Macdonald’s forwarding of a National Policy suggests, it was believed that implementing industrialization required formally instituting measures to promote it. Perhaps the most critically important measure was figuring out how to fund industrializing projects. The federal government had the option of imposing tariffs to raise money. Other sectors, however, had to compete to attract investment dollars.

There was, therefore, a proliferation of advertising directed at attracting the interest of men who controlled fortunes and had ties to financial markets (see Fig. 5.11). All and sundry, but particularly "Boosters" worked to ensure that those who were rich and powerful, and those able to organize the rich and powerful (see Fig. 5.6), would set the industrial process in motion in the boosters’ part of the world.

Fig. 5.11 Post Card celebrating "Post office Guelph, Ont." Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan no. 2265435 [Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.11 Post Card celebrating "Post office Guelph, Ont." Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan no. 2265435 [Copyright: Expired].Open Source graphic from Project Gutenberg EBook: Bertram Poole, The Stamps of Canada, courtesy of Library and Archives Canada. Public Domain (accessed 10 December 2010).

Digital Album"[17]

View: digital album, “Views of Canadian Cities,” produced by civic boosters. The Introduction to the online collection, “Digital Album: Canadian Souvenir View Albums, of Canadian Cities,” from the National Gallery of Canada, Canada’s Digital Collections initiative, Industry Canada, explains:

“Souvenir View albums from the 1880s and 1890s were published by Canadian stationers and booksellers, and by the railways for whose clientele they were destined.

The view albums from the early twentieth century were made to appeal not only to tourism, but to settlement and investment as well. The albums from Western Canada in particular contain high-spirited statistics on such factors as population growth, the number of building permits issued, and the number of miles of paved sidewalks and streets, along with inventories of urban amenities: schools, banks, hospitals, churches, hotels, abattoirs, hydrants, newspapers; and ’gents’ clubs.’

The covers and title pages of the publications reflect this civic pride and boosterism, proclaiming: The City Phenomenal; The Wonder City; The Celestial City; The Electric City; Steady Growth Means Solid Prosperity; Its Present Greatness, Its Future Splendor; and Has Never Known a Set Back.

A flurry of superlatives announces that there is not a city in the Dominion that is not matchless, glorious, irresistible, majestic, delightful, picturesque, sublime, unsurpassed, prosperous, marvellous, prominent, handsome or busy—a mecca, hub, gem, bull’s eye, metropolis, queen, gateway, or doorway—well-situated, well-lighted or well-drained.

Eden, European Kingdoms, Babylon, Switzerland, Naples, the Rhine, Gibraltar, and the Tropics are evoked by way of comparison. Cities vie in claiming the most churchgoers, the most ambitious youth, the fewest uncouth individuals, the most fire alarm systems, and the most right-angled intersections.”

Whether an urban center already existed or was only projected to develop, the hope was that entrepreneurs, industrialists, and financiers (including bankers) would combine to invest in its future.

Booster:

Subscribes to the philosophy of “Boosterism”: the idea that actively "boosting," or promoting a place will improve public perception of it. During the expansion of the Canadian West, civic leaders and local newspapers in small towns made extravagant predictions for their settlement in the hope of attracting more residents and businesses (and thereby inflating real estate prices—boosters were often involved in land speculation).

Land Speculator:

Buyer of undeveloped lots, at a time (or in a place) of low demand, to hold until it is profitable to sell at a time of high demand.

Entrepreneur:

One who organizes, manages, and assumes the risks of a business or enterprise."[17]

Financier:

“One who specializes in raising and expending public moneys."”[18]

Capitalist:

An owner of private capital (money, goods, property, investments, stocks, bonds, wealth etc.).

Industrialist:

“One owning or engaged in the management of an industry.” The first known reference dates to 1864.[19]

Table. 5.4 Defining the ranks of the Industrious Hopeful and of the Rich and Powerful

It is worth keeping in mind that the elite of the business world from 1870 to 1920 (see Table 5.4) expected to profit from actively participating in industrialization. They believed that the “better world” they promoted (and that some may genuinely have anticipated) would include their personal betterment in terms of finances, social status, and power.

Part II

OBSERVATIONS: CANADIAN INDUSTRIALIZATION VIEWED IN HINDSIGHT

View the movie clips below. Note: To connect to a "Featured Thematic Tour" once you arrive at the McCord Museum webpage, click on either the "movie clip" or "flash clip" link for a quick, historical description. (You will note that there is also a link to a "web tour." This is a lengthier description consisting of photographs accompanied by additional information. Taking the web tour is entirely optional).

Urbanization and Industrialization

Existing cities in Eastern Canada

"Montreal 1850-1896: The Industrial City" by Paul-André Linteau, Université du Québec à Montréal

Montreal 1896-1914: The Canadian Metropolis,” by Paul-André Linteau, Université du Québec à Montréal

Boosterism in Western Canada

"Lethbridge: Coal City in the Wheat Country," by Sir Alexander Galt Museum and Archives

Implications of Industrialization

View "Getting Down to Business: Canada, 1896-1919," by Duncan McDowall, Carleton University

View “Brand New and Wonderful: The Rise of Technology,” by Jacques G. Ruelland, Université de Montréal

The Rise of a Professional Class of Experts

(see also Unit 5, Reading 3: Marion McKay, "The Tubercular Cow Must Go’: Business, Politics, and Winnipeg’s Milk Supply, 1894-1922."[20])

| | View “Big Cities, New Horizons,” by Robert Gagnon, Université du Québec à Montréal |

Dealing with Aspects of a Disturbing Downside

The contrast between what had been imagined and what was experienced was at times pretty extreme. There were problems—some that ought to have been anticipated, others that apparently came as a surprise. One problematic outcome of industrialization (that we might think the example of England should have suggested was a likely possibility) was air pollution from coal-fired furnaces and engines. It was hard to breathe in England’s industrial cities. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century bronchitis was known as “the British disease.”[21]

Canadian industrial cities, it turned out, were no healthier than those of England, and in Canada the working class, which included workers’ spouses and children, did not necessarily enjoy conditions that anyone found particularly acceptable.

"The splendour and misery of urban life," McCord Museum.

Health care became an issue (and for some patent-medicine entrepreneurs, an industry). Health remained a concern for Canadians well into the later decades of the 20th century.

"A Bourgeois Duty: Philanthropy, 1896-1919," by Janice Harvey, Dawson College.

“Cures and Quackery: The Rise of Patent Medicines,” Denis Goulet, Université de Sherbrooke.

“Growing Up Healthy in the 20th Century,” Nathalie Lampron.

A graphic example (Fig. 5.12) of how the industrial world did not always work as expected: the new technology, it turned out, was not always safe. Accidents had of course existed prior to industrialization, but mechanized technology tended to increase the scale of an accident. The consequences could be devastating for the large number people who relied on the technology.

Fig. 5.12 “Locomotive of the City of Winnipeg Light and Power Department which caused the collapse of a swing bridge,” dated 30 June 1914. Source: Library and Archives Canada / PA-141075 [Restrictions on use: Nil. Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.12 “Locomotive of the City of Winnipeg Light and Power Department which caused the collapse of a swing bridge,” dated 30 June 1914. Source: Library and Archives Canada / PA-141075 [Restrictions on use: Nil. Copyright: Expired].

| | "Disasters and Calamities, 1867-1896," by Nathalie Lampron. |

Workers were not happy and there was agitation to bring reality into accord with what had been promised. (See Fig. 5.13; also Unit 5, Reading 2: Andrew Graybill, "Texas Rangers, Canadian Mounties, and the Policing of the Transnational Industrial Frontier, 1885-1910."[22])

Fig. 5.13 “Street scene during the Winnipeg strike of 1919.” Source: Library and Archives Canada / PA-202200 [Restrictions on use: Nil; Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.13 “Street scene during the Winnipeg strike of 1919.” Source: Library and Archives Canada / PA-202200 [Restrictions on use: Nil; Copyright: Expired].

| | "Winds of Change: Reforms and Unions," by Peter Bischoff, University of Ottawa. |

CONCLUSION

Evaluating the Plan

Industrialization in Canada did not work out exactly as planned. [In addition to notes below, review Unit 4, Timeline 2, 1913-1940s.]

The Canadian economy does not appear to have been rescued by the National Policy. In 1907, despite railroad building, industrial expansion, and massive immigration, the country experienced a sharp economic recession. By 1913, the necessary, continuous supply of investment capital had dried up. The country started to slide into a severe economic depression marked by industrial contraction. Factories closed and unemployment figures soared, especially in urban centres. There had been crop failures in the West, and the transcontinental railways were debt-ridden.

Then, international war broke out in 1914. Initially it made troubled economic times even worse: unemployment increased, and both the Canadian government and industry had a hard time obtaining credit (which they needed to operate). It was hoped that a war-time munitions industry would give an economic boost. But, by 1915-1916, because many men had joined the army, there were complaints about a labour shortage (particularly from farmers). And, government spending had increased dramatically—on borrowed money. Between 1913 and 1918 the national debt rose from $463 million to $2.46 billion (most of it owed to the United States, because Britain could not afford to lend to anyone).[23]

By war’s end (1918), the “Great [Industrial] Powers of Europe” were virtually bankrupted (including England, although Germany, as the loser, was required to pay off the winners’ debts—a long, drawn-out reparation, because the Germans had no immediate means of doing so).

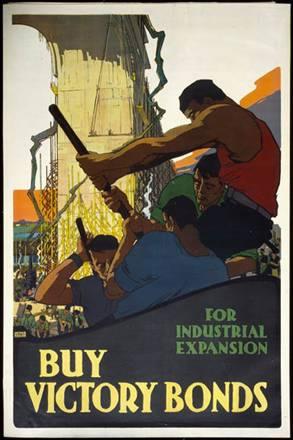

Despite industrialization’s uneven record—when what was promised was weighed against what actually happened—by 1920 the majority of Canadians appear to have been committed to taking the project of inventing Canada as an industrialized nation as far forward as possible.

Fig. 5.14 Arthur Keelor, poster, "For Industrial Expansion: victory loan drive. 1914-1918." Source: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-28-661 [Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.14 Arthur Keelor, poster, "For Industrial Expansion: victory loan drive. 1914-1918." Source: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-28-661 [Copyright: Expired].

This attitude is not surprising. Given the immense sacrifice of Canadian lives that fighting for the right to pursue progress and live in a better world had exacted, anyone who advocated retreating to pre-industrial ways would have been regarded by most Canadians as objectionably unpatriotic—not to mention insane (after all, progress, like time, was perceived to be unidirectional. It only went forward on a linear path; there was no conception of alternative paths that might also lead to an economically prosperous future. And, besides, the economy in 1870 had been depressed as well, so there seemed no point in reverting to a non-industrialized way of life).

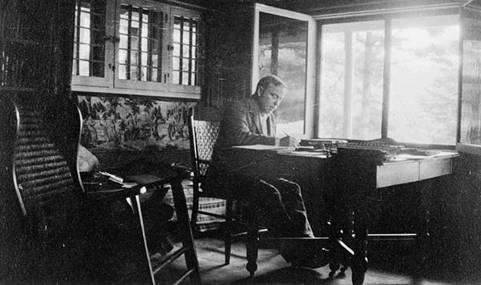

What another Prime Minister Thought by 1920: Inventing an Industrialized Canada through Political Policy

Fig. 5.15 Unknown photographer, “W.L. Mackenzie King writing the book Industry and Humanity,” dated 1917, Kingsmere, Quebec. Source: Library and Archives Canada / C-003176 [Restrictions on use: Nil Copyright: Expired].

Fig. 5.15 Unknown photographer, “W.L. Mackenzie King writing the book Industry and Humanity,” dated 1917, Kingsmere, Quebec. Source: Library and Archives Canada / C-003176 [Restrictions on use: Nil Copyright: Expired].

At the end of the period, towards the end of the Great War, Canada’s future Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, wrote Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction(1918). The book conveyed his unshaken belief that industrialization was key to prosperity and a better future.[24] He did, however, seek to address what he saw to be a fundamental problem: the "relations between Capital [money] and Labor [workers]."

In his prefatory note King explained that:

Fig. 5.16. Text from W.L. Mackenzie King, Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction (Toronto: Houghton Mifflin company, 1918), xii, Internet Archives full text online [copyright expired].

Fig. 5.16. Text from W.L. Mackenzie King, Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction (Toronto: Houghton Mifflin company, 1918), xii, Internet Archives full text online [copyright expired].

The opening paragraph of his introductory chapter further observed:

Fig. 5.17. Text from W.L. Mackenzie King, Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction (Toronto: Houghton Mifflin company, 1918), xv, Internet Archives full text online [copyright expired].

Fig. 5.17. Text from W.L. Mackenzie King, Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction (Toronto: Houghton Mifflin company, 1918), xv, Internet Archives full text online [copyright expired].

Thus, despite evident problems, it is clear that the dream of an industrialized Canada had not died. Post-war Canadians still wanted a country with busy, yet aesthetically pleasing urban centres—hubs of industry—where goods were manufactured and distributed world-wide. They still imagined a future of prosperity and ease in which they and their children could enjoy the benefits that scientifically informed experts and technological innovators would design.

Post Script

The generation that followed did not see prosperity for many years. The 1920s were not a “roaring” decade for everyone, and the Great Depression of the 1930s was a time of hardship for many more.

For a 1930s comedic critique of modernization by mechanization see:

Movie: “Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times.”

It wasn’t until after war broke out again in 1939 that all of Canada’s factories returned to full production levels.

By the 1950s a great many urban dwellers counted getting out of the city—to live in suburban settings that mimicked the simpler, friendlier, “village” life of an imagined past—to be markers of social upward-mobility and financial success (see Unit 3, Inventing Canada as a Consumer’s Playground: Kids, Cars, and Goin’ Down the Road.)

Notwithstanding the slow start, expert opinion continued to maintain that nations that industrialized had made significant gains in wealth and health over those that had not industrialized.

[Recommended] See Hans Rosling, YouTube video, “200 countries, 200 years, 4 minutes,” [BBC expert].

Bibliography

[1] See Dolores Greenburg, “Energy, Power, and Perceptions of Social Change in the Early Nineteenth Century,” The American Historical Review 95, no. 3 (June 1990): 693-714, (accessed 14 December 2010).

[2] Detail of illustration in Louis Figuier, and Edward Burnett Tylor, Primitive Man (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1870), ii, captioned “A Family of the Stone Age,” Google Books full view [copyright expired] (accessed 14 December 2010).

[3] Detail of illustration, “Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry octobre.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, public domain image [copyright expired] (accessed 14 December 2010). See also M. Louis Bordeau, “The Beginnings of Agriculture,” The Popular Science Monthly 46, no. 41 (March 1895): 678-688, Google Books full view [copyright expired] (accessed 14 December 2010). The introduction to the magazine reads, “Popular Science gives our readers the information and tools to improve their technology and their world. The core belief that Popular Science and our readers share: The future is going to be better, and science and technology are the driving forces that will help make it better.”

[4] Currier and Ives, print detail, “The Progress of the Century: the lightning steam press, the electric telegraph, the locomotive, [and] the steamboat,” (ca. 1876), Flikr.com, suggested credit: Library of Congress via pingnews [public domain: copyright expired] (accessed 14 December 2010).

[5] See, for example, Economic history pamphlets, vol. 61 (1885), 88, Google Books full view, (accessed 8 December 2010).

[6] “Industrialization,” Online Etymology Dictionary (accessed 8 December 2010).

[7] For a discussion of how the meaning of words changes over time see “Semantic change,” Rice.edu, (accessed 20 May 2013).

[8] See R.A. Butlin, “Early Industrialization in Europe: Concepts and Problems,” The Geographical Journal 152, no. 1 (March 1986): 1-8, and the observation of scholars that despite prolonged study, by 1982 “we are still little closer to a general or theoretical understanding of the transition from an agrarian to an industrial world”; and Dolores Greenburg, “Reassessing the Power Patterns of the Industrial Revolution: An Anglo- American Comparison,” American Historical Review 87, no. 5 (December 1982): 1237-1261, stable url, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2595302 (accessed 14 December 2010).

[9] See Andrew Merrilies, “The Railway Rolling Stock Industry in Canada: A History of 110 Years of Canadian Railway Car Building,” (accessed 10 December 2010).

[10] See Sarah Carter, “Two Acres and a Cow: ‘Peasant’ Farming for the Indians of the Northwest, 1889-97,” Canadian Historical Review 70, no. 1 (1989), pdf available online, (accessed 10 December 2010).

[11] Geoffrey J. Mathewa, and R. Louis Gentilcore, Historical Atlas of Canada, vol. 2, The land transformed, 1800-1891 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 59, Google Books preview (accessed 10 December 2010).

[12] T.W. Acheson, “Changing Social Origins of the Canadian Industrial Elite, 1880-1910,” The Business History Review 47, no. 2 Canada (Summer 1973): 189-217. Available via U of M Libraries, JSTOR database (accessed 8 December 2010).

[13] Edward Minister and Son, illustration, Gazette of Fashion and Cutting-Room Companion, (London: 1871), Google Books full view [copyright expired] (accessed 10 December 2010).

[14] View any nineteenth-century map of the British Empire.

[15] Scholars have critiqued this theory. See for example, Sidney Pollard, review, Patterns of European Industrialization, The Nineteenth Century, ed. Richard Sylla and Gianni Toniolo, The English Historical Review 110, no. 435 (February 1995): 227-228; and Ray Kiely, Industrialization and development: a comparative analysis (London: UCL Press, 1998), 28, and his explanation of Britain’s economic success. Google Books preview (accessed 10 December 2010).

[16] See Julian M. Sturtevant, Economics, Or, The Science of Wealth (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1886), Google Books full view (accessed 10 December 2010).

[17] “Entrepreneur,” Merriam-Webster.com, (accessed 20 May 2013).

[18] “Financier," Merriam-Webster.com (accessed 20 May 2013).

[19] “Industrialist,” Merriam-Webster.com (accessed 20 May 2013).

[20] Marion McKay, “‘The Tubercular Cow Must Go’: Business, Politics, and Winnipeg’s Milk Supply, 1894-1922,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History / Bulletin canadienne d’historire de la médicine 23, no. 2 (2006): 355-380. Full text online (accessed 8 December 2010).

[21] Derek M. Elsom, quoted in Bjorn Lomborg, The Skeptical Environmentalist (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2001), 164.

[22] Andrew Graybill, “Texas Rangers, Canadian Mounties, and the Policing of the Transnational Industrial Frontier, 1885-1910,”The Western Historical Quarterly 35, no. 2 Summer, 2004): 167-191. Available via U of M Libraries, JSTOR database (accessed 14 December 2010).

[23] See “Forging Our Legacy: Canadian Citizenship and Immigration, 1900–1977,” Citizenship and Immigration Canada (accessed 8 December 2010).

[24] W.L. Mackenzie King, Industry and humanity: a study in the principles underlying industrial reconstruction (Toronto: Houghton Mifflin company, 1918), Internet Archives full text online (accessed 9 December 2010).