This case is part of your Harvard Business Coursepack on the IKEA Group attached Imagine that you are Steve Howard, the IKEA Group's Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO). What are your recommendations

![]()

W I N T E R 2 0 0 7 V O L . 4 8 N O . 2

SMR239

Sandra Rothenberg

Sustainability Through

Ser vicizing

P le a s e n o te th a t g ra y a re a s re fle c t a r tw o rk th a t h a s

b e e n in te n tio n a lly re m o v e d . T h e s u b s ta n tiv e c o n te n t

R E P R I N T N U M B E R 4 8 2 1 6 o f th e a r tic le a p p e a rs a s o rig in a lly p u b lis h e d .

S T R AT E G Y

Sustainability

Through Servicizing

A

to discount, enlightened companies have begun embracing the vision of

“sustainable development,” defined by the World Commission on Environ-

s the scientific evidence for environmental degradation becomes harder

ment and Development as “the ability of current generations to meet their

needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs.”1 But while sustainable development is a desirable goal for society, critics sug- gest that significant, if not radical, changes in the basic assumptions behind current business models are needed to achieve it.

Contemporary management scholars suggest that sustainability can be ad- dressed by focusing on increased operational efficiency or more

environmentally benign products and processes.2 Some argue, however, that while these changes are necessary, they are not sufficient because they do not address consumption levels. Gains in operational efficiency and environ- ment-friendlier technology may even eventually be counteracted by increases

in consumption.3 Thus, in order to be a truly sustainable society, developed

nations must consume less.4

This is no small challenge to industrial societies, where consumption has

| In an increasingly | traditionally been an end in itself. Ye t companies are often in the best position to help customers reduce consumption — even of their own products. By | ||

| environmentally conscious | “servicizing,” suppliers may change the focus of their business models from selling products to providing services, thereby turning demand for reduced | ||

| and cost-conscious world, | material use into a strategic opportunity. This new approach is part of the larger move throughout industry to the pro- |

suppliers can make their

vision of services, which, evidence has shown, is linked to higher and more stable

| business both more | profits.5 In addition, some argue that because services are more difficult to imitate than products, they are a source of competitive advantage.6 Thus many tradi- | ||

| sustainable and more profitable by focusing on services that extend the efficiency and value of | tional manufacturing companies, especially those faced with shrinking markets and increased commoditization of their products, are adopting service provision as a new path toward profits, growth and increased market share.7 Hewlett-Packard Co., for example, has defined “tomorrow’s sustainable business” as one in which it shifts from selling disposable products to selling a range of services around fewer products.8 Another company embracing this approach is Interface Inc., a commercial carpeting company based in Atlanta, |

their products.

Sandra Rothenberg is an associate professor of management, marketing and interna-

| Sandra Rothenberg | tional business at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s E. Philip Saunders College of Business. She can be reached at [email protected]. |

| Georgia, whose seven-point model of sustainability includes pro- viding “the services their products provide, in lieu of the products themselves.” A study by the Tellus Institute found that in business- | About the Research |

to-business markets, companies such as Coro, DuPont, IBM and

This article is part of a cross-industry research program that

| Xerox have turned to replacing products with services as an inte- looks at how companies develop and implement strategies for gral part of their environmental strategy.9 more environmentally sustainable business practices. The pro- While some researchers have identified companies that are tak- ing this servicizing approach, little has been documented about the process of executing the strategic change.10 Shifting business mod- els so profoundly is not easy, as it challenges the traditional gram is supported by the International Motor Vehicle Program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the RIT Printing In- dustry Center, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The article draws from the experiences of three companies: Gage Prod- ucts, PPG Industries and Xerox. For each of the companies, organizational assumption that selling more of a product is good access occurred through different parts of the organization, as and selling less of it is bad. But for those companies willing to ac- it was important that data come from multiple perspectives. cept the challenge, the result can be even greater financial success. Therefore, semistructured interviews were arranged with at | |||

| Case Studies in Servicizing | least one high-level strategic manager, a company employee involved in the actual provision of services and products, and a | ||

Drawing from the experiences of three companies — Gage Prod-

customer representative. When possible, multiple interviews ucts, PPG Industries and Xerox — whose present business models

in each of these categories were conducted. A total of 24 peo-

help customers purchase less of their traditional products, I dis- ple were interviewed, as detailed below.

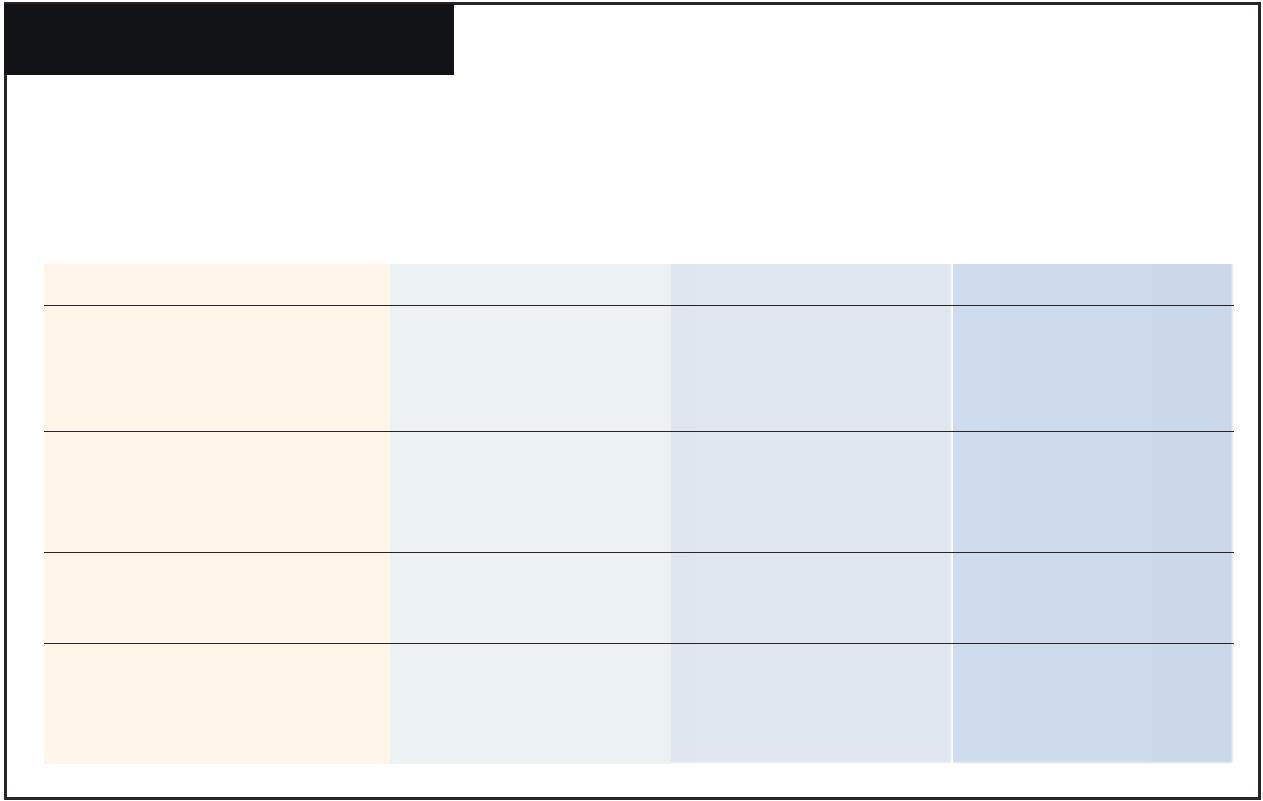

| cuss a few of the obstacles these companies faced and the ways in which they were able to overcome them. (See “About the Re- | Summary of People Interviewed |

Level of Interview Gage PPG Xerox search.”) Each company offers a different set of products, yet they

all profitably shifted to providing services that help customers

High-Level Manager 1 3 3

| meet their goals while using less of these products. Moreover, in all three cases, environmental benefits resulted as well. (See | Line-Level Employee 1 2 4 |

“Three Cases in Servicizing,” p. 86.)

Customer Representative 4 4 2

| Gage Based in Ferndale, Michigan, Gage Products Co. started out | Interviews were coded, and coded segments were then | ||||

| as a distributor of specialty chemicals for Shell Oil Co., but over time it shifted to making combination chemical blends for auto- motive paint applications. Because of the specialized nature of its products, Gage has long needed to take a more active role in the management of customers’ paint shop operations. Its employees | separated from the field notes and placed in a matrix in order to explore how the cases differed from one another.i In this matrix, a mixture of direct quotes and summary phrases was used. An iterative analysis of the data revealed underlying patterns. | ||||

| would routinely work at assembly plants to consult on color changes, adoption of new application equipment or the use of specialty paint blends. Eventually, Gage was looked at by most | i. This method is suggested by R. Yin, “Case Study Research: Design and Methods” (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1994); and M.B. Miles and A.M. Huberman, “An Expanded Sourcebook: Qualitative Data Analysis” (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1994). | ||||

customers not just as a supplier of solvents but also as a color

change expert.

A turning point in Gage’s business model came when it intro- tion in the volume of cleaning solvents that Gage supplied to

duced a new product called Cobra,which cleaned paint circulation Chrysler paint shops.

systems in an environmentally friendlier manner than did its For example, early in 1996, one assembly plant was concerned

predecessor. Gage quickly learned that it could not sell this new that it was going to exceed the Environmental Protection Agency

material, which had some unique characteristics, as it had sold its emission limits on volatile organic compounds by the end of the

traditional products; the company needed to be even more active year. With Gage’s help, it was able to cut VOC emissions by ap-

in managing product use at the customer’s site. proximately one-half, thereby avoiding the installation of costly

This new service role was evolving just as one of Gage’s cus- abatement equipment.

tomers, Chrysler Corp., was facing more stringent environmental

| regulations. To help Chrysler meet these regulatory demands, | PPG Industries In the late 1990s, PPG Industries Inc. of Pitts- |

Gage started to take greater responsibility not only for introduc- burgh, Pennsylvania, a coatings manufacturer, was also faced

ing new materials but also for ensuring their proper use, which with Chrysler’s demand for reductions in product use as a result

included more efficient use, and that meant an ultimate reduc- of two main drivers: high costs and environmental regulations.

84 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW WINTER 2007

from Dec 2022 to Jun 2023.

The strategic response for PPG was to help its customer reduce

paint use.

As one PPG manager explained: “The automotive companies

were going to move down a path of trying to decrease usage,

whether we participated in that relationship or not. So what PPG

decided pretty early in the game was that participating in that

transition and helping to manage it was more beneficial than

waiting for it to be thrust upon us. We tried to structure a pro-

gram that created a win-win scenario.”

With this new arrangement, PPG on-site representatives started

to take over new management tasks at the plant, including material

ordering, inventory tracking, inventory maintenance and even

some regulatory-response duties. Through this increased service

role, the company has helped Chrysler reduce material use. Inter-

estingly, the new business model developed by PPG and Chrysler

has started to become the norm for the industry. Chrysler even

asked PPG to teach the model to its competitors, such as DuPont

Coatings & Color Technologies and BASF Corp., and PPG agreed.

First, it did not want to lose Chrysler as a customer in the relatively

small automotive paint market, and second, PPG considered such

teaching a part of its service offerings.

Xerox Corp. Xerox’s move toward servicizing was part of a larger

move that developed during the 1990s as its core products were

becoming commoditized. In 1994, Xerox started calling itself “the

Document Company,” marking a change in strategy that focused

less on devices that create printed materials and more on the infor-

mation that flows within a business. To drive this strategy forward,

the company launched Xerox Global Services, its Paris-based con-

sulting division, in late 2001 to help customers improve efficiencies

in their document-intensive business processes.

A key component of Xerox Global Services is its focus on the

office. To help improve the productivity of the office environment,

Xerox introduced the Office Document Assessment tool, which

analyzes the total costs associated with alternative document-

making processes. A typical ODA report offers a range of

suggestions for increasing office efficiency, improving worker pro-

ductivity and reducing costs. Often central to such suggestions is

reducing the number of devices through consolidation, which

leads to reductions in the use of toner, paper and other consum-

ables, all of which Xerox sells. The reduction in total devices can

be substantial, moving from a ratio of more than one device per

employee to a ratio of one device per 10 or more employees.

For one of Xerox’s clients, United Health Services Hospitals of

Binghamton, New York, the opportunity to benefit from these ser-

vices persuaded it to stay with Xerox, which had been providing

UHSH with office equipment for more than 10 years. In 2001,

UHSH was tempted by offers from Xerox’s competitors. But after

Xerox completed an ODA, the hospital organization was impressed

enough with the potential savings that it entered into a new part-

WINTER 2007 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW 85

S T R AT E G Y

nership with the company. While some of the initial estimates for to even look at somebody [other than Xerox] would require

savings were high, Xerox eventually helped UHSH reduce costs by something pretty significant to change.”

about $60,000 annually. That was done, in part, through reductions Second, through these closer relationships, suppliers can ex-

in the number of printers being used, the use of related materials pand the range of products they sell within the company. A Gage

and the amount of overall print produced. on-site representative at Chrysler, for example, discussed how he

As was the case with UHSH, Xerox sells this set of services has found other opportunities for his company’s products there.

primarily as a way to increase its clients’ productivity and lower At UHSH, Xerox provides a greater portion of the printers that

its costs. But environmentally aware customers recognize and remain. As one Xerox manager explains, “When you concentrate

value the benefits that accompany reductions in material use. As on what is right for the client, it is inherently going to give you

one Xerox customer commented: “Not only is our printing sys- more business and more revenue, which is an offset to the declin-

tem a massive expense, but it also impacts our rubbish disposal. ing product element of any one transaction.”

We can save a small forest each year!” Third, companies can use this business model to attract new

| Multiple Advantages | customers impressed by the company’s social consciousness, manifested in its array of environmentally friendly services and |

One major concern with the servicizing business model is that products. The first words you see rolling across Gage’s Web site companies could suffer loss of revenue, and maybe even put are “Sustainable solutions, cost reduction, environmental effi-

themselves out of business, if reduced demand for their products ciency,”12 and Gage has indeed won several environmental awards goes to the limit. That has certainly not been the case for the for its programs. These alone, according to one top manager, have companies profiled or for numerous others. With PPG and been leveraged into significant market-share gains.

| Chrysler, for example, PPG saw that its customer was already moving toward decreased paint use. By helping Chrysler sustain | Challenges in the Move to Servicizing |

this shift, the servicizing strategy not only generated good will As with any large-scale initiative for change, the move to servicizing

but was also a way to extract revenue from a new source. For its is not easy. It is no small task to reframe the company credo from

part, Xerox was able to keep UHSH from defecting to a competi- “sell more product” to “help our customers do X and use less of our

tor by offering an attractive combination of services and products product in the process.” A manager at PPG reflected on this chal-

that reduced costs. Meanwhile, all three companies believe they lenge:“One of the things we stress most is that this is a cultural shift.

have attracted new customers with their new business strategy. It is very difficult as a supplier to get the people on your staff used

The benefits of servicizing extend beyond customer attraction to the idea that they want to help take product out of the system.”

and retention, however. For Xerox, this strategy moved the com- The people most resistant to such change are often the sales

panyfrom focusingonproductsthatwerebecomingcommoditized staff. At Gage, salespeople who worked on commission opposed

to a mix of products and

services that increased

Three Cases in Servicizing

revenue. In 2005, approxi-

mately 22% of Xerox’s

The transition to a service-based business model is not an easy one. Three companies that have

profitably shifted to providing services — Gage Products, PPG Industries and Xerox — all still revenue was driven by Xerox

| Global Services; future ser- vice provision represents a | offer a set of products, but they actually help customers to use less of those products, creating an environmental benefit. |

$20 billion market oppor- Gage PPG Xerox

| tunity for Xerox, the company estimates.11 Additionally, all three | Old Business Model of Maximizing Product Sales | Selling chemical blends for automotive paint application | Selling paint for automotive paint application | Selling printers, copiers and support- ing products | |||||

| companies note that as a result of a servicizing strat- egy, they are able to build | New “Servicizing” Business Model | Providing an effective paint shop operation | Managing efficient and quality paint shop operations | Managing efficient document-manage- ment processes | |||||

| closer customer relations, which has three main | Material Goods Reduced Solvents and cleaners Paint Printers, copiers, paper and toner | ||||||||

| advantages. First, the cus- tomer is less likely to change suppliers. As the UHSH representative says, “For us | Other Environmental Benefits | Lower VOC emissions, lower paint use | Lower VOC emissions, improved health and safety protection | Reduced energy use and solid-waste generation | |||||

the new business model, seeing it as directly conflicting with their one that states a cost per gallon of

own financial interests. The transition was not a simple matter product to one that often sets a

for Xerox either. As one top manager said: “While traditionally a “cost per unit,” whereby the cus-

product company, Xerox has certainly recognized the need to tomer pays a set amount

lead our clients in finding ways to better leverage their assets, and — including both products and

in some cases that leads to a cannibalization of our own installed services— foreveryvehiclepainted.

base, which can cause angst within a culture formally dependent “Under this relationship,” explains

mainly on product sales.” one top manager,“contracts are ar-

| Resistance is not limited to the suppliers’ staffs. Within the customer’s organization too, higher-level managers may not have | PPG and Chrysler | ranged so that profits are not 100% dependent on the quantity of ma- | |||

| a clear idea of what this new relationship will look like and how it will ultimately be implemented. At UHSH, it took the purchas- ing manager some time to understand the new relationship with | reformulated their traditional | terial sold to plants.” Thus, there is no incentive on the part of the sup- plier to increase material use. In | |||

| Xerox and the value it would provide to his organization. Moreover, reductions in the use of various materials are likely | contract so that | some cases, these contracts even in- clude specific targets for cost | |||

| to mean changes in customers’ work patterns and assumptions at the operational level. And the concerns of workers there can pre- sent issues for suppliers as well. Gage and PPG employees on the | both parties could share in the | reduction or solvent reduction as part of the service provision. Using a slightly different ap- | |||

| plant floor were sometimes challenged by disgruntled paint shop employees tied to long-held routines. Xerox found that some | savings realized | proach, PPG and Chrysler reformulated their traditional con- | |||

| customers faced employee resistance to new modes of managing information and, perhaps something most people can relate to, from annual reductions in tract so that both parties could share in the savings realized from reduc- the removal of their own personal printing devices. tions in material usage. Before, the | |||||

| Managing the Change | material usage. | customer would pay per gallon of material; now, it pays a preset | |||

Given these challenges, how can companies manage the shift to amount, negotiated yearly, based on

servicizing? In analyzing the three cases, I observed that strategies the prior year’s record of efficiency.

to facilitate such change fell into six general categories: In this way, both PPG and Chrysler have an incentive to reduce paint

use, which not only benefits the bottom lines of both companies but

| Building on Existing Strengths At all the companies, managers en- | also improves Chrysler’s environmental performance — and image. |

couraged employees to think of the shift as an extension of the When developing contracts, uncertainties emerged about how

companies’ existing service orientations. This new thinking was the new relationship would actually play out. What, for example,

least difficult for on-site representatives, who already had a would be the supplier’s role in the customer’s operations, the extent

strong, direct customer-service focus. The companies also built to which operational changes could be made (particularly if they

on the technical knowledge of their staffs. At Gage, for example, involved new technologies or high levels of resistance), and the ac-

| employees used their expertise in cleaning materials and paint shop color changes to offer innovative ways to reduce solvent use. And PPG employees used their expertise in paint material prop- erties, material tracking and data analysis, all of which are critical in analyzing opportunities for material use reduction. Redefining the Basis for Profit in Contractual Agreements All three cases involved changing contracts so that they would (1) encourage sup- pliers to look for opportunities to reduce product use, and (2) | tual amounts of material and money that could be saved? Mutual trust and a willingness to experiment, observe and adjust were criti- cal factors in facing such uncertainties. It was likely, for example, that there would be variances from the contracted numbers based on projections. In fact, for UHSH and Xerox, the first year actually saw increased costs. But because of the strong relationship between the partners, UHSH understood the reasons for this transient increase and stuck with the partnership to see savings in the following year. |

create a win-win situation by which both parties would benefit

Communicating the New Business Model In order to reduce resis-

from the relationship. Perhaps the simplest contract specifies a set tance to change — and, on a more positive note, elicit active

profit for a predetermined bundle of services and products. The cooperation — it is important for management to communicate

contract between Xerox and UHSH, for example, outlines a cost per continually to employees the new business model and the reason

printed impression, which includes estimated service and new- it is making this change. In all three cases, managers needed to

product costs. Gage also changed its contract with Chrysler from explain how a program that was seemingly eroding the sales of its

S T R AT E G Y

products would actually benefit as training in “value selling,” in which they are taught to show the

the company. customer that their services — such as managing a more efficient

Suppliers must also help to paint process — are worth something. In fact, they are taught how

educate staff at the customer or- to estimate the actual dollar value of their services.

ganizations,where managers often At Xerox, the new business model required information tech-

are confused about their new re- nology skills and industry-specific process knowledge. Some of

sponsibilities and employees at these skills were already available in-house, but the company also

the operational level are being had to hire additional staff to augment its knowledge base. In one

| asked to alter processes and do their work with fewer material in- | “If you pay sales- | case, Xerox purchased an entire company in order to obtain ex- pertise in a particular information technology field. | |||

| puts. For example, Gage spends a great deal of time explaining to sometimes-resistant paint shop | people based on overall revenue as | ||||

Highlighting Environmental Advantage To varying degrees, interest

has been generated in this new business model’s positive envi-

| workers why they need to change customary work practices and re- | opposed to per- | ronmental impacts. For Gage and PPG, their customer (Chrysler) was already motivated to reduce material use. Gage also actively | |||||

| strict their solvent use. Changing Incentives Traditionally, | device transaction,” explains a Xerox | educates some of its customers about the connections between environmental performance and cost reduction. “For many years, to be ‘green’ — that is, to be environmentally friendly — | |||||

| salespeople are paid more when they sell more product, but this | manager, “they are | meant to be expensive,” says Gage’s in-plant representative. “But we try to tell people that you can have your cake and eat it, too. | |||||

| incentive structure is inconsis- tent with the goals of servicizing. more inclined to You can put together these very beautiful environmental pro- grams and it can also save you money.” Providing this concentrate on the Therefore, in all three cases, sales overarching view and the data that back it up, he adds, is a valu- incentives were changed to be able service to a customer. bigger picture.” more aligned with the new busi- Similarly, Xerox finds that framing its services as a means to | |||||||

ness model. help both the environmental and financial bottom lines makes an

Gage, seeing that compensat- attractive proposition for many customers.

| ing employees on a transaction-by-transaction basis was working in opposition to the company’s objectives, eliminated sales com- | The Future of Servicizing |

missions. Similarly, Xerox has started paying sales staff on the To date, most management literature on sustainability has not

basis of total year-over-year revenue increase from their customer questioned the basic assumption of the typical business model

base or their targeted geographic area. — that a primary goal of a product manufacturer is to sell more

Still, explains a Xerox manager, “not a lot of the salespeople product. But as society faces environmental limits to material

will make the journey easily. It is a tough transition because you consumption, that belief must be questioned. This article out-

are now selling an intangible alongside a tangible, and the intan- lined the experiences of three suppliers operating under a

gible (services and optimization) is often the more important business model that allows economic growth to occur while also

component of the transaction. But if you pay them based on helping society to step away from the spiral of increasing con-

overall revenue as opposed to per-device transaction, they are sumption. In the servicizing approach, material goods are not

more inclined to concentrate on the bigger picture and you tran- seen as ends in themselves; instead, companies make money by

scend those boundaries of traditional compensation.” helping customers achieve their goals while using less product.

Because of the correlation between reduced material use and

| Acquiring New Skills While companies should of course build on | reduced cost, it is tempting to sell these programs based on their |

their staff’s existing skills, each supplier we studied had to acquire potential cost savings alone. But companies may also use serviciz-

new skills as well. These included technical skills that involve a ing as an integral part of their environmental strategies. In fact,

deep understanding of the customer’s processes, as well as new for each of the cases in this article, some customers expressed

customer relations skills. At Gage, engineers have been retrained interest in reducing their environmental impacts — often

for improved customer service, and new hires are being selected prompted by external (that is, regulatory) pressures. As these

for personality traits and experience that fit with roles they might pressures increase, so too might the customer’s desire to reduce

play in customers’ plants. At PPG, employees who will be working product use. Instead of being threatened by this phenomenon,

on-site are given the traditional technical-service training as well suppliers can take an active role in the reduction. By redefining

their business model, they can turn a potential problem into a

World,”Harvard Business Review 75 (January/February 1997):67-76.

| strategic opportunity. Many questions remain to be answered about servicizing. The

| 3.C.Sanne, “Are We Chasing Our Tail in the Pursuit of Sustainability?”In- ternational Journal of Sustainable Development 4, no. 1 (2001):120-133. 4. Ibid.; P. Dobers and L.Strannegard, “Design, Lifestyles and Sustain- ability: Aesthetic Consumption in a World of Abundance,” Business Strategy and the Environment 14 (2005): 324-336; A.Schaefer and A.Crane, “Addressing Sustainability and Consumption,” Journal of Macromarketing 25, no. 1 (2005): 76-92; and E.F.Schumacher, “Small Is Beautiful: Economics as If People Mattered” (Vancouver, British Co- lumbia: Hartley & Marks, 1999). | |||||||

| broader product base and a strong research and development department may be best placed to benefit from the servicizing approach. They have the potential to offer more innovative solu-

| 5. M. Sawhney, S.Balasubramanian and V. Krishnan, “Creating Growth with Services,” MIT Sloan Management Review 45, no. 2 (winter 2004): 34-43. 6. R. Oliva and R.Kallenberg, “Managing the Transition from Products to Services,” International Journal of Service Industry Management 14, no. 2, (2003): 160-172. | |||||||

| Another question is whether this model can also be applied in a business-to-consumer setting. It certainly worked for Patagonia, based in Ventura, California, which sells clothing and equipment to practitioners of “silent sports” (which use no motors), such as fly fishing, paddling and trail running. This company, which made a strategic decision to reduce growth and instead focus on providing value through product quality13 to its unique consumer base, may well be atypical. The challenges of selling services that replace ma- | 7. Ibid.; K.Bates, H.Bates and R.Johnston, “Linking Service to Profit: The Business Case for Service Excellence,” International Journal of Service Industry Management 14, no. 2 (2003): 173-183; and G. All- mendinger and R.Lombreglia, “Four Strategies for the Age of Smart Services,” Harvard Business Review 83 (October 2005): 131-145.Inter- face, for example, claims that replacing products with services has increased market share at the expense of competitors.The Interface model can be found at www.interfacesustainability.com/model.html. 8.See L.Preston, “Sustainability at Hewlett-Packard:FromTheory to Practice,”California Management Review 43, no. 3 (spring 2001):26-37. | |||||||

| terial use are likely to be far greater for the average company trying to cater to the average consumer. | 9. A.White, M.Stoughton and L.Feng, “Servicizing:The QuietTransition to Extended Product Responsibility,” report by Tellus Institute (1999). | |||||||

| Future research may therefore include exploring whether or not the application of this model is as promising for consumer markets as it is for business-to-business ones, and whether the process of change differs. Answering these and other questions may help diverse companies move toward business models that do not rest on the assumption that selling more is better but in- stead emphasize sustainable levels of consumption. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank the participants in this research study for their time and knowledge, as well as the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the International Motor Vehicle Program at MIT, and the RIT Printing Industry Center for their financial support. The author would also like to acknowledge those who have pro- vided feedback on this and earlier versions of this article. REFERENCES 1. The World Commission on Environment and Development, “Our Common Future” (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987). | 10. As noted by Oliva,“Managing the Transition” and Sawhney, “Creat- ing Growth,” very little has been published on the actual transition process for companies moving from selling products to services.The same holds for transitions that involve reducing material consumption on the part of the consumer.The environmental benefits of servicizing are discussed by White, “Servicizing.” Other articles that mention the environmental benefits of servicizing include: I. Ropke, “Is Consump- tion Becoming Less Material:The Case of Services,” International Journal of Sustainable Development 4, no. 1 (2001): 33-47; Preston, “Sustainability and Hewlett-Packard”; M.W.Toffel, “Contracting for Ser- vicizing,” working paper, Haas School of Business, Berkeley, California, May 15, 2002; E.D. Reiskin, A.L.White, J.K. Johnson and T.J.Votta, “Servicizing the Chemical Supply Chain,” Journal of Industrial Ecology 3, no. 2 and 3 (2000):19-31; K. Hockerts, “Eco-efficient Services Innova- tion, Increasing Business-Ecological Efficiency of Products and Services,” in “Greener Marketing” 2nd. ed. M. Charter and M.J. Polon- sky (Sheffield, United Kingdom: Greenleaf Publishing, 1999), 95-108 and other articles focusing on “product service systems” and “chemical management. Some additional references can be found at the Web site of the Chemical Strategies Partnership, www.chemicalstrategies.org. Some articles that mention this type of strategic approach, although not all focusing on the environmental benefits, include K. Funk, “Sustain- ability and Performance,” MIT Sloan Management Review 44, no. 2 (winter 2003): 65-70; and Sawhney, “Creating Growth.” 11.More information can be found at J.Firestone, “Growth Opportunities: Services,”http://a1851.g.akamaitech.net/f/1851/2996/24h/cacheB.xerox. com/downloads/usa/en/i/ir_2005InvestorConference_JFirestone.pdf. | |||||||

| 2. See, for example, R.S.Marshall and D. Brown, “The Strategy of Sus- tainability: A Systems Perspective on Environmental Initiatives,” California Management Review 46, no. 1 (fall 2003): 101-126; J. Hall and H.Vredenburg, “The Challenges of Innovating for Sustainable De- velopment,” MIT Sloan Management Review 45, no. 1 (fall 2003): 61-68; F.L.Reinhardt,“Environmental Product Differentiation:Implications for Cor- porate Strategy,”California Management Review 40, no. 4 (summer 1998): 43-73;and S.L.Hart,“Beyond Greening:Strategies for a Sustainable | 12. The Gage Web site is www.gageproducts.com. 13. D.H.Meadows, D.L.Meadows and J.Randers, “Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse, Envisioning a Sustainable Future” (Post Mills, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 1992). Reprint 48216. For ordering information, see page 1. Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2007. All rights reserved. |

WINTER 2007 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW 91

PDFs ■ Reprints ■ Permission to Copy ■ Back Issues

Electronic copies of MIT Sloan Management Review

articles as well as traditional reprints and back issues can

be purchased on our Web site: www.sloanreview.mit.edu

or you may order through our Business Service Center

(9 a.m.-5 p.m. ET) at the phone numbers listed below.

To reproduce or transmit one or more MIT Sloan

Management Review articles by electronic or mechanical

means (including photocopying or archiving in any

information storage or retrieval system) requires written

permission. To request permission, use our Web site

(www.sloanreview.mit.edu), call or e-mail:

Toll-free in U.S. and Canada: 877-727-7170 International: 617-253-7170

e-mail: [email protected]

To request a free copy of our article catalog, please contact:

MIT Sloan Management Review

77 Massachusetts Ave., E60-100

Cambridge, MA 02139-4307

Toll-free in U.S. and Canada: 877-727-7170

International: 617-253-7170

Fax: 617-258-9739

e-mail: [email protected]