Milestone One: Change Readiness or Needs Assessment Audit Scenario You have been contracted as an HR consultant by a U.S. LLC in Wilmington, Delaware, to solve their internal issues. This U.S. LLC is

Book Title: Leading Organizational Change

Authors: LAURIE LEWIS, JAMES M. KOUZES, BARRY Z. POSNER

Southern New Hampshire University

This edition first published 2019© 2019 Laurie Lewis

Edition History1e 2011 Wiley2e 2019 Wiley

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Laurie Lewis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Office(s)John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

Editorial Office350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of WarrantyWhile the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication data applied for

9781119431244 [Paperback]

Cover Design: WileyCover Image: ©Larry Washburn/Getty Images

CHAPTER 1 (Lewis)Defining Organizational Change

To improve is to change; to be perfect is to change often

Winston Churchill

Life is change. Growth is optional. Choose wisely

Unknown

Wisdom lies neither in fixity nor in change, but in the dialectic between the two

Octavio Paz, Mexican poet and essayist

As these opening quotations hint, change is often considered a sign of progress and improvement. Partly owing to a cultural value, organizations are under extreme pressure to constantly change. Zorn, Christensen, and Cheney (1999) make the case that “change for change's sake” (p. 4) has been glorified to an extent that it has become managerial fashion for stakeholders to constantly change their organizations. If it isn't new, it cannot be good. If we aren't changing, we must be stagnant. If we don't have the latest, we must be falling behind. If we aren't improving, we must be inadequate. These scholars go on to argue that the cultural and market pressures that demand constant change in competitive organizations can lead to disastrous outcomes including adoption of changes that are not suited to the goals of the organization; ill‐considered timing of change; dysfunctional human resource management practices; exhaustion from repetitive cycles of change; and loss of benefits of stability and consistency. It appears that this faddish behavior, like becoming slaves to any fashion, can lead to poor decision‐making and poor use of resources. For example, a case study of the collapse of Ghana Airways (Amankwah‐Amoah and Debrah 2010), evidence of the frequent change of top managers and leaders within the organization played a major role in its demise. From 2002 to 2004 Ghana Airways had five different government‐appointed chief executives. This pattern of change of leadership represented a sort of “ritual scapegoating.” Informants suggested that:

…the airline was treated as an extension of the public administration or government departments under the control of politicians who allot key management posts as political favors. None of the executives had sufficient time to develop and implement any strategy to address the negative profitability and to ensure the long‐term survival of the airline (p. 650)

The Role of Communication in Triggering Change

Communication plays a critical role in fostering the fad of change in organizations. We hear stakeholders in and around organizations making arguments that change is inherently good and that stability is necessarily bad. The continual use of language of change in terms considered positive – improvement, continuous improvement, progressive, innovative, “pushing the envelope,” being “edgy” – is juxtaposed against language of stability in negative terms – stagnant, stale, old fashioned, “yesterday's news,” “behind the times.” The rhetorical force of labeling in this way pushes an agenda that contributes to the faddishness that Zorn et al. point out.

Pressure to change also derives from complex organizational environments that put many demands on organizations to adapt and innovate. For example, current shifts towards a “gig economy” in many parts of the world may demand significant organizational changes in the ways labor is managed. The “gig economy” involves a market of labor based on frequent, independent, short‐term contracts and freelance work rather than longer‐term traditional jobs. Examples of those making use of this increasingly prevalent form of labor are transportation services, delivery services, video producers, couriers, household task workers, among many others. Numerous “gig platforms” that match employers and “giggers” have sprouted up including Uber, Lyft, HopSkipDrive, Airbnb, Postmates, TaskRabbit, Sparehire, Freelancer, and HelloTech (https://smallbiztrends.com/2017/02/gig‐websites.html). For the organization that makes use of these “giggers” there are certainly many implications for how they plan for, maintain relationships with, evaluate, and reward individuals who perform work for them. Benefits of engaging with these sorts of workers include flexibility, the ability to hire/fire at will, reduced costs for benefits, lack of the need to negotiate and honor long‐term contracts, and reducing needs for office space. However, the erratic nature of these multiple relationships, and the lack of continuity and long‐term employee–employer relationships surely brings new human resource challenges.

Oftentimes, the rationale that changing circumstances demand changing tactics, responses, and strategies makes it difficult for organizations to resist trying to do something new or at least appear they are doing something new. Change can be triggered by many factors even in the most calm of financial times. Triggers for change include:

The need for organizations to stay in line with legal requirements (e.g. employment law, health and safety regulations, product regulation, environmental protection policies)

Changing customer and/or client needs (e.g. changing demographics, fashions that spur desire for specific products and services)

Heightened problems or needs of clients served

Newly created and/or outdated technologies

Changes in availability of financial resources (e.g. changes in investment capital)

Funding agencies for nonprofits

Administrative priorities for government agencies

Alterations of available labor pool (e.g. aging workforce, technological capabilities of workforce, immigration)

Trends in alternative labor arrangements

Alteration of trade relationships or global economy

Crisis in the industry, economy, government, or organization.

In addition, some organizations self‐initiate change and innovation. Change initiated within organizations can stem from many sources including the personal innovation of employees (individuals developing new ideas for products, practices, relationships), serendipity (stumbling across something that works and then catches on in an organization), and through arguments espousing specific directions that stakeholders in and around organizations think should be adopted or resisted. As stakeholders assert their own preferences for what organizations do and how they operate, their interactions produce both evaluations of current practice and visions for future practice that incite change initiatives.

Communication is key in triggering all change. In fact, we can easily argue that none of the other factors that trigger change are truly the direct cause for change until stakeholders recognize them, frame them in terms that suggest change is necessary, and convince resource‐holding decision‐makers to act on them by implementing change. That is, the necessity for change or the advantage of responding to changing circumstances is one that is created in the interaction among stakeholders. The process is subtler than we might assume at first glance. It is not as simple as noticing that the environment is demanding change or is presenting the opportunity for productive change. We actually need to piece together a construction of the environment that suggests this reality.

Karl Weick (1979) suggests “managers [and others] construct, rearrange, single out, and demolish many objective features of their surroundings” (p. 164). He calls this process enactment. In this process, stakeholders “enact” or “construct” their environment through a process of social interaction and sensemaking. As we encounter our world we attempt to form coherent accounts of “what is going on.” We do that by selecting evidence that supports one theory over the other – like a detective might in solving a murder mystery. However, the process is far from perfectly rational or a lone act of individuals. We have biases about what we want to be the truth of the matter and we are influenced heavily by the enacted realities of those around us (Weick 1995). Through communication we share our theories of “what is going on” and we purposefully or incidentally influence the process of enactment of others. As Weick (1979, 1995) argues, we simply forget some facts, reconstruct some to better fit the theory of reality we prefer, and look for supportive evidence to bolster our preferred case. He suggests that sensemaking is as much about “authoring” as interpretation.

In this way, communication plays a central role in surfacing or suppressing triggers for change. For example, a theory that the economy is in a downturn can be supported and refuted through different ways of looking at evidence, different ways of framing evidence, and constructing evidence through managing meanings that others attach to their observations. An alternate theory can reconstitute observations, history, and the narrative around these “facts” in ways that suggest not a downturn but a natural lull or a period of great opportunity. Perceptions that an organization is in a crisis; needs to be responsive to a particular stakeholder; is headed for greatness; exists in a time rich with opportunity; or any number of other characterizations are created through this process. As discussed more in Chapter 8, communication among stakeholders is at the heart of change processes in organizations because of this highly social process of making sense of what is going on and “spinning” it into narratives and theories of the world around us.

Failure in Change

Many attempts at organizational change have met with failure by the standards of stakeholders who served as implementers. Statistics on failures of implementation efforts are significant. Knodel (2004) suggests that 80% of implementation efforts fail to deliver their promised value, 28% are canceled before completion, and 43% are overextended or delivered late. Researchers estimate from data that approximately 75% of mergers and acquisitions fall short of their financial and strategic objectives (see Marks and Mirvis 2001), as many as 95% of mergers fail (e.g. Boeh and Beamish 2006), 60–75% of new information technology systems fail (Rizzuto and Reeves 2007), implementation of advanced technologies fail 86% of the time (Decker et al. 2012), and estimates of sales force automation failure are between 55 and 80% (Bush, Moore, and Rocco 2005). A recent global survey of executives by McKinsey consultants revealed that only one‐third of organizational change efforts were considered successful by their leaders (Meaney and Pung 2008). These alarming statistics make one wonder if it is possible to do change well.

The consequences of failure are costly on many levels. Failure of organizational changes may have minor or major consequences for stakeholders associated with an organization and on the ultimate survival of an organization. The energy and resources necessary to undergo moderate to major change are often high. Costs include:

Financial expenditures

Lost productivity

Lost time in training and retraining workers

Confusion, fatigue, and resentment for workers, clients, customers, suppliers, and other key stakeholders

Damage to the brand

Disruption in workflow

Loss of high value stakeholders including workers, supporters, and clients/customers, among others.

Those costs are not paid off if the change does not yield benefits and/or if it causes additional disruption as the organization retreats to previous practices or moves on to yet another change to replace a dysfunctional one. Change, while common in many organizations, is frequently troublesome and often fails to yield desired benefits.

Most of the failure statistics are generated through official accounts of how organizational leaders and managers judge outcomes. The judgments of failure and success made by non‐implementer stakeholders are much more difficult to estimate. Anecdotal evidence in case studies suggests that stakeholders – primarily employees – often have a difficult time during change and that change takes a high toll on stress levels and feelings of commitment to the organization. (I will return to this issue in Chapters 2 and 4.) Negative outcomes of change processes in organizations are much more frequently documented than positive ones but rarely are non‐implementers asked for their assessments of the results of change programs. Certainly, the ways in which stakeholders talk about changes that are occurring and have occurred – as failures or successes – impacts their sensemaking about the worthiness of any given initiative. The degree to which implementers and stakeholders agree in framing success and failure can have tremendous impacts on future change initiatives. I will discuss these issues more in Chapter 4.

What Is Organizational Change?

We should examine more closely exactly what this common and troublesome aspect of organizational life entails and what is meant by the concept of organizational change. Zorn et al. define change as referring “to any alteration or modification of organizational structures or processes” (1999, p. 10). This and other definitions of change often imply that there are periods of stability in organizations that are absent of change or that a normal state for organizations is marked by routine, consistency, and stability (see Figure 1.1).

Diagram displaying a rightward thick arrow at the left having a curved arrow labeled STABILITY pointing to a rightward thick arrow labeled STABILITY.

Figure 1.1 Standard model of relationship between periods of stability and change.

Although stakeholders may experience organizations as more familiar and stable at some points and as more disrupted and in flux at other points, we can certainly observe that organizing activity is made up of processes and as such is always in motion and always changing. Poole (2004) draws attention to the naïve assumption that these two modes are clearly separable. He argues that “all planned change occurs in the context of the ambient change processes that occur naturally in organizations” (p. 4). Thus, change is better illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Diagram a thunder shape at the left having a curved arrow pointing to another thunder shape at the right.

Figure 1.2 Model of continuous change with punctuated moments of noticeable change.

This book is concerned with planned change and periods in organizations where purposeful introductions of change are made in some bracketed moment in the flow of organizing activities. That is, managers and implementers attempt to disrupt what is normal and routine with something else.

Implementing change in organizations may start from a number of sources and processes. However, it nearly always involves these three key elements:

equation

Innovation is a creative process of generating ideas for practice. Although organizational changes are not always the result of a self‐generated idea, often change comes about through intentional innovation processes used by organizations to create new ways of doing or new things to do.

Adoption is the term we use to describe leaders' formal decision to bring a change into an organization. When organizational leaders “adopt” a change, they commit to purchase of materials, hire of individuals, alteration of practice, addition, or development of policies, among other implications of this decision.

Diffusion is the process involved in sharing new ideas with others to the point that they “catch on.” For example, as organizational leaders communicate about a change to other organizational leaders, they may trigger subsequent adoption decisions by those organizations. Sometimes, as noted earlier, pressures from the environment drive changes or changes are spread through a network (e.g. professional associates) or within a particular context (e.g. industry). Organizational changes may be spread through a diffusion process where important organizational stakeholders or networked organizations select an idea and then others in the network become aware of the choice – typically through communication in social networks.

Drive‐thru Diffusion

An illustration of the process of diffusion is provided in the stories of the “drive‐thru window.” As we are all accustomed to now, drive‐thru windows are a modern convenience of fast‐food restaurants, coffee shops, pharmacies, banks, some liquor stores, and even marriage chapels in Las Vegas! The drive‐thru allows customers to do business without leaving their cars. Drive‐thru restaurants (different from drive‐ins where customers parked and received service at their car) were invented by In‐N‐Out Burger in 1948 (In‐N‐Out Burger Home Page n.d.). By 1975 the fast‐food giant McDonald's opened its first drive‐thru in Sierra Vista, Arizona, followed 10 years later by a drive‐thru in Dublin, Ireland (Sickels 2004). The success of drive‐thrus in the high profile fast‐food company doubtlessly encouraged the diffusion of the practice in other fast‐food businesses. As smaller chains sought to mimic the successful practices of McDonald's, they were more likely to adopt this practice to remain competitive.

Another pattern is shown in the use of drive‐thru banks which, following the 1928 adoption by UMB Financial, increased steadily over several decades and spread internationally.1 However, in recent years there has been a decline in drive‐thru banking due to increased traffic and availability of automated teller machines, telephone, and Internet banking. As these new technologies became available, the drive‐thru feature at banks has become less desirable or needed and so is disappearing.

Discontinuance (Rogers 1983), the gradual ending of a practice such as the drive‐thru innovation, is brought about through the rise in other innovations that are being diffused throughout the banking industry. The convenience of automated teller machines in every mall, many stores, and scattered throughout any person's daily path, makes the convenience of the drive‐thru comparatively less desirable. The observations of these changes in the environment as other innovations diffused more and more widely, has led many banks to decrease use of their own drive‐thru.

In the story of adoption of drive‐thrus by pharmacies, we find that some current research indicates that dispensing of medications through drive‐thru windows may increase the chance the pharmacist will become distracted, be less efficient, and make more errors.2 Further, some pharmacists worry that replacing face‐to‐face interaction with a drive‐thru experience will harm both the professional standing of pharmacists and the quality of exchanges between pharmacists and customers. In fact, the American Pharmacists Association put out a statement in 2008 discouraging the use of drive‐thru pharmacies unless pharmaceutical care can be adequately delivered.3 In this case, although the practice of drive‐thru convenience is still common, a set of stakeholders from the professional field may eventually bring enough pressure to bear that the use of drive‐thrus in this context will be discontinued. This example illustrates the power of communication in both spawning and stalling the spread of change in an environment. Owners of pharmacies will have to balance their observations of what successful competitors are doing, and the desires of customers, with pressures from professionals in their employ and agencies that regulate dispensing of medication. Balancing the demands of different stakeholders while keeping an eye on the diffusion and/or discontinuance of drive‐thru pharmacy technology will play a key role in any given pharmacy's decision to maintain this innovation. The means by which organizations keep tabs on such trends is through their communication with stakeholders.

Communication, Social Pressure, and Diffusion

As the drive‐thru examples help illustrate, a key to diffusion is often the social pressure of what other successful organizations in the environment or context are doing and how success is defined. Social pressure is exerted through communicative relationships. For example, Andrew Flanagin (2000) found evidence that nonprofit organizations' self‐perceptions of their status and leadership position in their field are positively correlated with adoption of websites. They ascribed this in part to felt pressures to stay on the leading edge. As more and more organizations in a local area or within an industry adopt a specific innovation, the pressure mounts for those who do not have that innovation to try it. However, as powerful stakeholders eschew an idea or find they desire other alternatives, pressure to drop a new idea may mount. In another communication study, Zorn, Grant, and Henderson (2012) found evidence that social influence within professional networks altered the ways in which new technologies were viewed and the degree of initial enthusiasm for their adoption. They also found that issues related to resources of time, money, and infrastructure also played critical roles in their decisions to use these technologies.

Some ideas provoke more attention as they become more popular (more diffused) in the context or environment in which an organization exists. For example, Total Quality programs became highly popular and started to catch on in the 1980s as a marker of excellence in companies around the world. Having a quality program in your organization became an important indicator that your products, services, and operations were well run, reliable, and continuously being improved (all markers of Total Quality).

Awards are given for organizations that are able to demonstrate evidence of quality programs. The Malcolm Baldridge award (see Highlight Box 1.1), named in honor of the Secretary of Commerce from 1981 until his death in 1987, is the most prominent example of this. The award is recognized internationally as a prominent marker of high quality. Another international standard used in quality management systems is called ISO 9000 and is maintained by the International Organization for Standardization located in Switzerland.

Types of Organizational Change

There are many ways of describing types of organizational changes. Here we will review three ways to categorize and conceptualize different change types. First, we can describe change as planned or unplanned. Keeping in mind that organizing activity is constantly in flux, we can still isolate periods of discernible disruptions to patterned activity.

Planned changes are those brought about through the purposeful efforts of organizational stakeholders who are accountable for the organization's operation.

Unplanned changes are those brought into the organization due to environmental or uncontrollable forces (e.g. fire burns down the plant, governmental shutdown of production), or emergent processes and interactions in the organization (e.g. drift in practices, erosion of skills).

There is sometimes a fine distinction between planned change and planned responses to unplanned change. For example, the death of a founder CEO would count as an unplanned change but the processes involved in replacing that founder with a successor would be considered planned change. Major unplanned changes in the circumstances of organizations often require responses that are more than mere crisis intervention. In some cases, lengthy and complex planned changes are necessary.

Another kind of unplanned change involves the slow evolution of organizational practice and/or structure over time. Some scholars (Hannan and Freeman 1977, 1989) have focused their study of organizations at the level of whole communities or niches of organizations and have examined the ways in which these systems evolve over time. For some theorists, change is conceptualized as occurring gradually as an inherent part of organizing (Miller and Friesen 1982, 1984). Life cycle theories specify standard stages of organizational development such as birth, growth, decline, and death. Others specify development of organizations as a sequence of alteration of organizational characteristics through variation, selection, retention, and variation within environments. As organizational decision‐makers take note of key environmental shifts and/or alterations of the life stage of an organization, they may make planned changes to adapt to those circumstances. Often the difference between planned and unplanned change concerns the perspective from which one views the change and the triggering events for change that are relevant to the analysis.

A second way we can describe change is in terms of the objects that are changed. Typically, scholars refer to these objects in discrete categories of: technologies, programs, policies, processes, and personnel. Lewis and colleagues (Lewis 2000; Lewis and Seibold 1998) have noted that organizational changes usually have multiple components that are difficult to describe with a single term. For example, technological changes usually have implications for new policy and new procedures and specify new role relationships. Making a new technology available necessitates specifying the appropriate use and users of the technology; the schedule and manner of use; and the personnel who can use and approve use. Further, the purposes of technologies are often to improve processes or products. For these reasons, it may not be useful or very accurate to describe “change type” in terms of whether they are technologies, procedures, or policies. Such theorizing is likely to be unreliable since so many changes have multiple components.

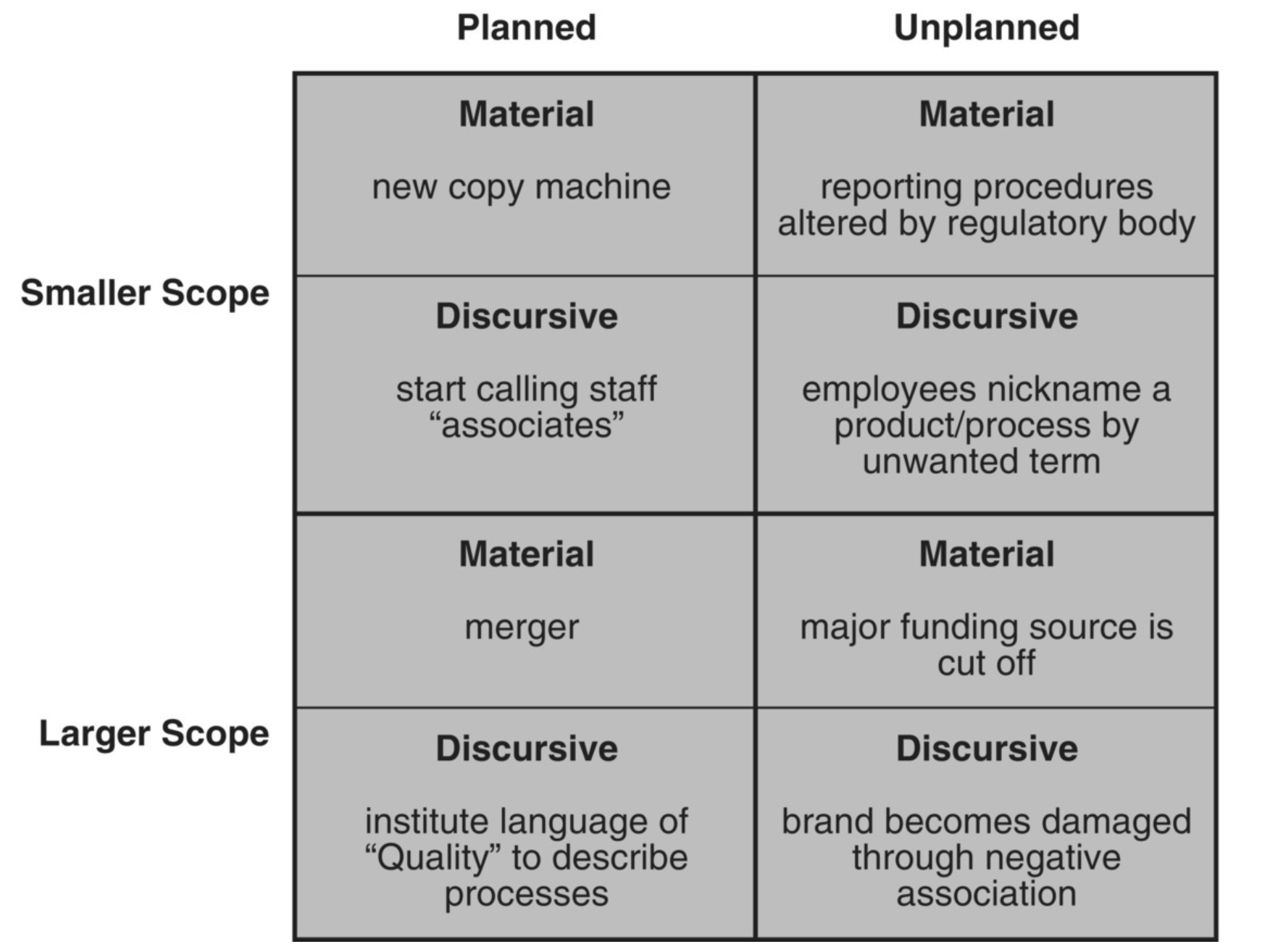

Zorn et al. (1999) have made the distinction between material and discursive changes. Discursive change (p. 10) often involves relabeling of practices as something new in order to give the appearance of changed practice without really doing things differently. They give the example of embracing the term “team” for a work group as a way of discursively altering how the organization considers the work and workers without really changing the practices or process of the work. They contrast this with material change that alters operations, practices, relationships, decision‐making, and the like. Although they underscore that discursive change is still consequential in organizations, it is often experienced differently from these other types of change.

I remember working in a fast‐food restaurant as a high school student when the company came out with a new promotion. This was for discounted deals for a somewhat more modest version of a regularly priced meal and was very popular for a summer. In fact, the deals were so popular that they generated a flood of new customers – good for business, but not necessarily regarded positively by the minimum wage earners whose job it was to serve all those customers. Consequently, we nicknamed the new meal “bummers.” When a customer ordered these meals, the front counter person would call back to the cooks and packaging folks “two bummers!” Once a secret shopper from the district came in to inspect and rate our performance and heard our new nickname for the product. She was not amused. This is a good example of how an unplanned discursive change (the relabeling of the new product) can occur in organizations.

A third way to describe types of changes concerns the size and scope of change. This is usually described in terms of first‐ and second‐order change (Bartunek and Moch 1987).

First‐order changes are small, incremental predictable interruptions in normal practice.

Second‐order changes are large transformational or radical changes that depart significantly from previous practice in ways that are somewhat frame‐breaking. These changes call key organizational assumptions into question.

Third‐order changes involve the preparation for continuous change.

One problem with this means of assessing the magnitude of change is that stakeholders oftentimes view changes in different ways. A change may be viewed as relatively minor and as a somewhat predictable interruption in normal practice for some, but for others it is considered an expansive and significant change. Individuals' experiences and tolerances for change vary and thus their perceptions of size and scope of change will vary as well. So finding an objective standard to judge size and scope may be meaningless if it does not match what stakeholders perceive.

Our individual assessments of the size and scope of change are affected by how directly the change affects us; how profound the change to our own lives may be; what we value in our organizational lives; our own history with change in our personal and organizational life; and perhaps most profoundly, the interactions we have with others about the change. In the example of Allen, the line worker in the Introduction, we see evidence that the merger represents a highly emotionally charged change for him. His reaction to the shift supervisor meeting is a gut‐wrenching feeling. This might be brought on by fears that the merger could result in layoffs and put his position at risk. It might be that the way of work in his unit might change dramatically and he might not be able to maintain an acceptable quality of work. For some of his co‐workers, the rumored merger might bring excitement if they think this will bring greater job security, higher wages, and more opportunities. Some may think it does not really change anything important for them. Each of these workers will potentially assess the size and scope of the change differently. Doubtless, they will share those assessments with one another and that is likely to trigger further sensemaking about “what is going on.”

For changes that are less well defined and less understood, the assessments of the size and scope will vary even more widely. The case of Allison (the professor in the Introduction) is a good example of this. Allison felt the briefing on the expected changes taking place in higher education was a waste of her time. From the perspective of those closer to the Department of Education hearings, this was a far‐reaching change that might reshape higher education. However, to Allison it seemed like another bureaucratic annoyance. Until she is convinced otherwise by trusted colleagues or influential people in her network, she would be dismissive of the change as unimportant and irrelevant.

Another complication in estimating the size and scope of change is that change is sometimes not one single thing. In fact, Nicole Laster (2008) argues that changes are rarely singular. That is, changes have parts and have consequences that are in themselves changes. In her conceptualization, multifaceted change occurs when more than one change occurs within the same time frame. She classifies multifaceted change as either multiple change – two or more independent changes occurring at the same time – or as multi‐dimensional change where one or more changes have subsequent parts. Certainly either type of multi‐faceted change, especially if a larger order of change, presents a greater burden on stakeholders experiencing the change than changes more singular and/or of a smaller order. In her study, the key difference in how individual employees made sense of the size and scope of the change was how implementers talked about it at the outset. This had a huge impact on what these employees were expecting at the outset of change and colored their experiences of change in terms of setting them up for surprises, additional stress, and disappointment.

Overall, the language we have reviewed here for describing types of change help us to estimate both the size of potential ripple effects of change in an organization and the degree to which change is likely to be expected or unexpected. This language also helps us to identify the range of potential stakeholders who will experience impact from a change or set of changes. The three major cases used in this book provide examples of the types of changes from planned (merger, communication technologies) to unplanned (alteration of policy and practices in shaping higher education institutions); material (merger, communication technologies, some aspects of higher education practice) and discursive (some aspects of higher education policies); and small (communication technologies) and large scope (merger, higher education policies and practices). The contexts for these implementation efforts span from an individually newly created organization, to a closely connected interorganizational network, to a geographically dispersed set of institutions. I will rely on examples from these cases to illustrate concepts throughout the book.

We can combine these three categories (planned/unplanned; small scope/large scope; material/discursive) that describe change to construct theory about how some kinds of changes may operate differently; present unique problems; require specific strategies; and/or have different implications for relationships between process and outcome. Figure 1.2 provides an example of how these different descriptors of change type can be used in concert to help us make predictions about change. With empirical work we could easily compare the eight combination types of change. For example, we might hypothesize that large‐scope, material planned changes are some of the most challenging changes to carry out involving high degrees of communicative and other resources. It also may be that unplanned discursive changes are harder to explain to stakeholders than are unplanned material changes and are also more likely to lead to subsequent planned changes. Further, assessment of intended and actual outcomes from discursive changes, especially when unplanned and large, may be more difficult than assessment of material change. These are only examples of the sort of hypothesis‐testing and ultimate theory building that can arise from fuller descriptions of types of change. Examination and comparison of specific real‐life cases of a variety of change types will also potentially yield important insights for both scholars and practitioners from the rich detail provided in such examples (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Types of organizational change in combination.

Complexity of Change Within Organizations

Changes in complex organizations have unique characteristics by virtue of the features of interdependence, organizational structures, and politics.

Interdependence

Interdependence concerns the degree to which stakeholders impact the lives of other stakeholders as they engage change. Unlike individual adoption of ideas/changes in private life (e.g. switching to HD TV, choosing a new doctor), individuals' choices to cooperate in change in organizations nearly always will have implications for others who are asked to make the same adoption choice and for others who are impacted by the ripple effects of change. So, my decision to select a given doctor over my current one may not impact my neighbor's decision (except insofar as he wants to pay attention to my choice or is socially influenced by it). However, my decision not to cooperate in a new work process could completely forestall another unit or set of workers' abilities to participate in that process as well as impact the customers of the product I help to produce. That effect is due to our interdependence.

Sequential interdependence is a special type of interdependence wherein stakeholders affect each other in sequence. An assembly line is a good example of this. As a worker towards the start of the line gets behind in her work, other workers later in the line will have the pace of their work affected too. If the later worker cannot do his part until the earlier worker does hers, they are sequentially interdependent.

Reciprocal interdependence (Thompson 1967) concerns the situation where one stakeholder's inputs are another stakeholder's outputs and vice versa. In this situation, the work of one person is necessitated by the work of another. Further, the products of the individual work provide input back to the original propagator of the work. A good example of reciprocal interdependence is joint authorship of a report or document. As one part is written, other parts may need to be adjusted to account for the new writing. As that rewrite is completed, the original work may be adjusted again. One author cannot adjust until he/she sees what the other author has done, and those changes are the cause of the additional changes.

Where workers or other stakeholders are sequentially or reciprocally interdependent, participation in change becomes highly social and creates greater demands for coordination. Because organizational goals are often premised on interdependence among the participants, organizational leaders are unlikely to utilize an individualized choice model in introducing change. More typically, organizational leaders make the choice on behalf of units or whole organizations and then use implementation strategies to cajole, persuade, or force a predesigned form of participation from internal (and sometimes external) stakeholders.

Organizations cannot always benefit from a particular change unless all, or at least most, of the stakeholders are using/participating in the change in a coordinated manner. For example, if the accounting department decides to switch to a new system for automating payroll that will be faster and more accurate, they would likely require all department supervisors to report employee work hours in the same way by the same deadline. If they let each supervisor decide independently how to report the hours and everyone was doing it differently, the benefits of the new system might not be realized. Not all changes in organizations operate in this manner. Some changes might well be adopted individually and differently. We'll return to this idea in a later chapter. The point here is that when interdependence is high, change often requires cooperative and coordinated efforts on the part of stakeholders.

Structures

Organizational structure is another component that makes organizational change especially complex and different from individual change. Organizations are made up, in part, by structures (Giddens 1984). Structures are rules and resources that create organizational practices. Rules include simple but powerful ideas like “majority wins” or “high performers are rewarded more than lesser performers.” Resources include ways of doing, organizational beliefs, and important possessions in an organization that can be invoked in order to move along a new idea or to make a case for staying the course on an action. Status is a powerful example of a resource in an organization. Those with powerful positions have an important resource in influencing how actions are taken. One reason people have power in organizations is by virtue of their formal (position in the organizational chart) or informal status (close connection with someone with formal status; opinion leadership; expertise; long tenure) (Stevenson, Bartunek, and Borgatti 2003). Information is another resource. As individuals or units increase their access and control over information, especially unique information, they become potentially more powerful. Information can be used, withheld, and shared in various ways that make some individuals or units able to manipulate the decisions made in organizations, shape knowledge claims that can be made, and/or impact the ways resources are allocated.

So, organizations are made up of many structures:

Decision‐making patterns

Decision‐making processes

Ladders of authority

Role relationships

Information‐sharing norms

Communication networks

Reward systems.

As change is implemented in an organization, it must survive all of the potential impacts of these structures. For example, if those who hold power in the organization (even those who are not within the group that approved adoption of the change) fail to support a change effort, it is much harder to sustain the effort. In another instance, a change may face challenges because it creates too many ripples in how rules operate in the organization. In another example, moving from a traditional management structure to a team concept of management may necessitate abandoning rules of hierarchy (move from those with official power making most decisions to sharing decision‐making); information‐sharing norms (move from hoarding information to widely sharing information); and rules of division of labor (move from strict job descriptions to loosening of roles and expanding job responsibilities).

Change may involve altering much about the organization's beliefs about work as well as practices. Because structures are highly embedded in organizations, they often are resistant to change. Stakeholders become accustomed to structures as they are and their mere continued existence over time may be reason enough to maintain them. From the way a group of boys picks teammates for a recess soccer game, to the way that a church group selects its leaders for important committees, to the way that organizations cooperating in an interagency collaboration decide how much money each organization must contribute to a project, structures are often highly fixed and determinant. Change that disrupts those structures often will be resisted or derailed to some extent. Of course, such resistance might be healthy for an organization and/or may end up serving the interests and stakes of more or different groups of stakeholders.

Stephen Barley (1986, 1990) has investigated the effects of the introduction of change on structure. Barley writes about the introduction of new technologies into workplaces and the resultant effects on social structure. In his 1986 study of the implementation of CT scanners in a hospital, he found that the introduction of this new technology had profound effects on the social structure, specifically role relationships, of radiologists and technologists. Technologists were more expert in reading the results of the new CT scanners and now held information and knowledge that violated the normative status relationship between technologists and radiologists. Barley describes this role reversal as generating considerable discomfort for both parties. To cope with the discomfort of dealing with situations in which technologists had to explain or teach radiologists, a clear violation of status norms, they created new patterns of interaction to avoid such encounters. Radiologists retreated from the CT area and the technologists took on more independent work. The discomfort of these structural ripple effects in this hospital made the implementation of the change much more complex.

In another example, Stevenson et al. (2003) studied the restructuring of networks in a school. A new position, academic director, was created in order to increase coordination (and thus more direct ties) among the different academic units at the school. Administrators in the school exercised “passive resistance” against the change over a year of attempted implementation. Much of the resistance centered around overlapping authority, decision‐making power, and areas of responsibility of those involved in curriculum planning. Essentially, those with high structural autonomy (e.g. those who brokered the structural holes in the organization) were opposed to a change that would deflate their influence. Stevenson et al. show how the “backstage” changes in the informal communication networks of this organization had profound effects on the efforts to resist this change. As the implementation effort was trying to promote increasing ties among units, informal processes were at work in increasing separation among units. Clearly, the changes to structure were challenging to accomplish and the power of informal structure, operating underneath the radar of the implementers, was so difficult to detect that they concluded that nothing had changed in the year of introducing the change.

Politics

Politics is another component of organizations that can present challenges for change efforts (Buchanan, Claydon, and Doyle 1999; Kumar and Thibodeaux 1990). Drory and Romm (1990) define the elements of organizational political behavior as (i) a situation conditioned by uncertainty and conflict, (ii) the use of covert nonjob‐related means to pursue concealed motives, and (iii) self‐serving outcomes that are opposed to organizational goals. From their perspective, politics results from the resolution of colliding interests among sets of stakeholder groups in and around organizations through institutional or personal power bases. As Boonstra and Gravenhorst (1998) argue concerning a theory of structural power during organizational change, “power use becomes visible when different interest groups negotiate about the direction of the change process” (p. 99). In politically sensitive change episodes where multiple parties have opposing interests and a balanced power relationship, “negotiations will be needed to come to an agreement about for instance the goals of the change, the way the change is going to be implemented, and the role of the different parties in the change process” (p. 106).

Implementation of change can compete for time, energy, attention, and resources that might otherwise be devoted to other things. The potential for this competition can give rise to politicization of change. Sponsors of a change can feel threatened by the redirection of resources towards other changes or other ongoing practices. Also, change programs that are risky or highly charged with potential for reward can give rise to competitive stakes in getting credit or blame for the outcomes. These dynamics can lead to sabotage, arguments rooted in self‐interest, deal‐making for mutual support, and the like. Buchanan and Badham (1999) conclude from their review of literature and a set of case studies that “political behavior is an accepted and pervasive dimension of the change agent's role” (p. 624). In fact, some research has found that failures of change can sometimes be traced to failure of organizational coalitions supporting the change to marshal effective political strategies (Clegg 1993; Perrow 1983).

In Blazejewski and Dorow's (2003) account of a privatization of the Polish company that produced the Nivea brand of personal care products in Poland, they describe how internal political barriers against organizational change inhibited its effective adaptation to new complex environmental conditions. When the company was reacquired by its former parent company, it was dramatically restructured through a coercive non‐participative model of change implementation. The authors suggest that resistance to this strategy was low because it was accompanied by the investment of a number of desirable resources including new pay and benefits; changing work conditions; and changes to physical environment and office technology. The commitment perceived by the takeover company facilitated tolerance for the top‐down style of management during the change. A micro‐level political game played out where the benefits outweighed the disadvantages of the method of change. This was possible because of the power base available to the implementers – namely, huge financial resources.

The Spellings case provides another example of how politics can play a role in change (US Department of Education 2006; see Case Box 1.2). When one of the Commissioners, a leader in an influential higher education association, decided neither to endorse nor sign the Report it served as a powerful symbol that provided both supporters and critics of the Report as a reference to rally for their side of the issues. For some this was seen as a demonstration of power that thwarted attempts to make progress outlined in the Report; for others it was seen as a useful and high profile means for those in higher education to stand up against the Commission's indictments against higher education. However his action was regarded by individual stakeholders, it is clear that this leader relied upon his status both in higher education and his visible role in the Commission as a means to make a symbolic statement that carried political weight with many stakeholders. The ways in which stakeholders made sense of that symbolic act influenced their own willingness to support the Report's conclusions.

Case Box 1.2: Spellings Commission Political Positions Play a Role

Each of the Spellings Commission members was asked to endorse the Report and all but one did. David Ward, the president of the American Council on Education, refused to sign. This was potentially a big problem since Ward represented the association with the most global and inclusive perspective on higher education. Ward explained his position in a statement that read in part:

I didn't oppose the Report; I just simply said I couldn't sign it. There were significant areas that I supported. But in my case, I needed to be on the record in some formal way about those areas that gave me some disquiet. … I consider [my negative vote to suggest] a qualified support of a substantial part of it, but there were some significant, important areas that I just couldn't sign on to.

David Ward's refusal to sign and explanation stimulated much sensemaking on the part of stakeholders. As one interviewee in our study said “I think it was probably, in the big scheme of things, helpful, because it did indicate that there were different points of view.” Some others expressed the point of view that the withheld signature further contributed to defensiveness and a counterproductive framing that decreased possibilities of a constructive response or collaborative tone. A few felt that Ward's action had little impact since other higher education leaders did endorse the Report.

Source: Adapted from Ruben, Lewis, and Sandmeyer (2008).

The picture emerging of change in complex organizations portrays a dynamic, interdependent, power‐oriented image. How stakeholders react to changes as they are introduced in organizations may certainly be based in part on assessments of costs and benefits of use/participation in the change as a stakeholder examines the features, ties, and likely consequences of the change itself. However, it is just as, if not more, likely that reactions to changes will be rooted in complex social systems, organizational structures, power relations, and other ongoing organizational dynamics. Further, as observed throughout this chapter, the sensemaking engaged in through interaction among stakeholders plays an incredibly important role in enacting the “reality” of “what is really going on” in change, environments, and organizations. Various stakes are played out in these sensemaking conversations that have tremendous implications for how interdependent stakeholders, connected through complex network relationships and power structures, come to grapple with change.

Conclusion

In summary, this chapter has introduced the concept of change and helped to define the ways in which we can describe change. We have noted that organizations of all types are pressured and pushed towards change for all sorts of cultural, environmental, and internal reasons, and that the ways in which stakeholders enact their environments through social interaction are highly influential in enabling change to be considered and implemented. Further, change efforts – especially large‐scale changes – often are constructed by influential stakeholders as having failed. Changes come in many sizes and types. We can describe change in terms of being planned and unplanned; of different types; and of different sizes and scope. We also have much evidence to suggest that change in complex organizations is often more dynamic and potentially more problematic because of the interdependent relationships among stakeholders, the political context of change, and the nature of organizational structures. Communication plays tremendously important roles throughout change processes in serving as the means by which people construct what is happening, influence the constructions of others, and develop responses to what is being introduced to them as change. The next chapter will focus more on some of the specific ways that stakeholders communicate and the communicative roles they play during organizational change.

CHAPTER 4: Outcomes of Change Proceses

Causes for Implementation Failures and Successes

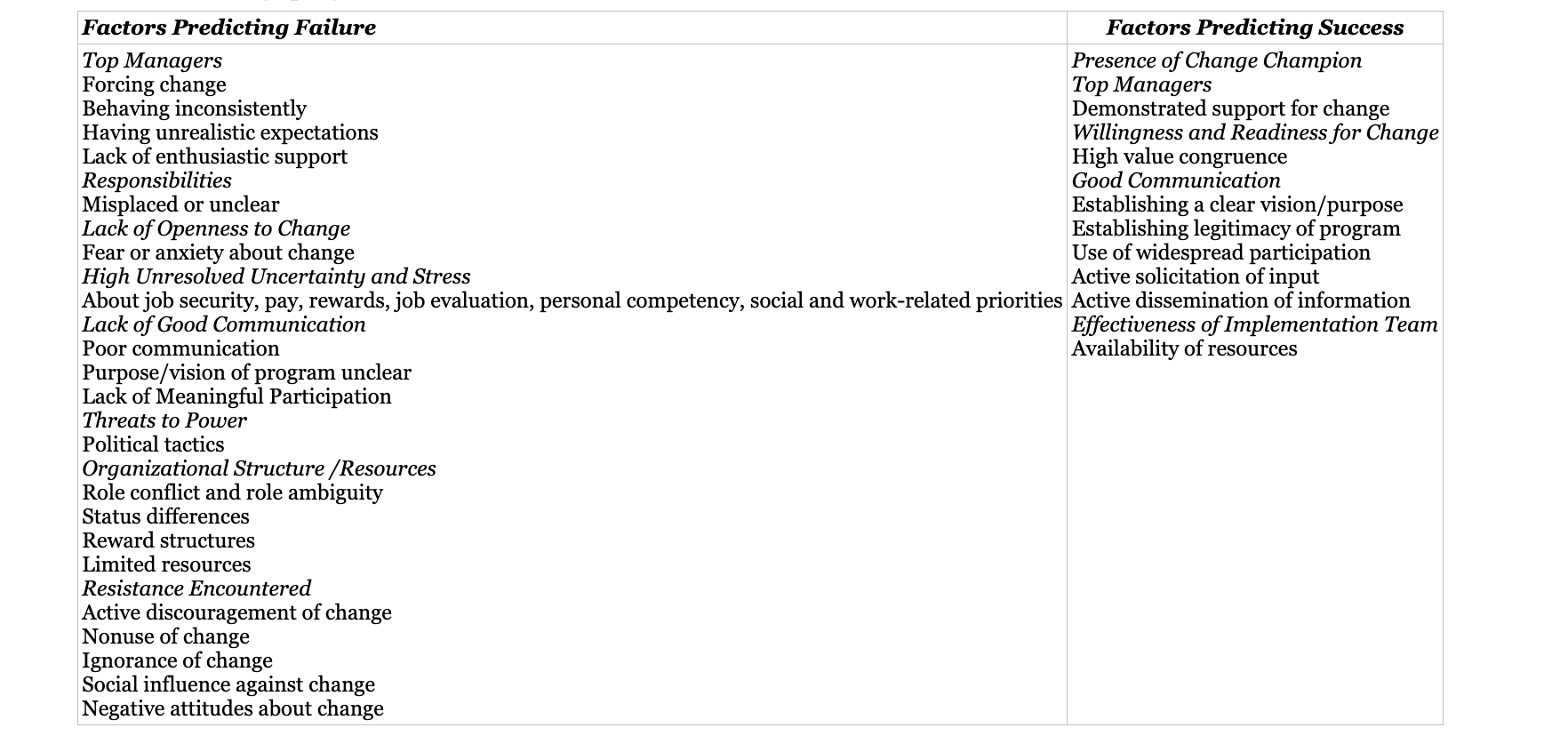

Change scholars have investigated many reasons for the failure or success of change programs in organizations. In a survey of consultants, researchers, and managers, Covin and Kilmann (1990) found that eight themes emerged as having the most impact on results. (See Table 4.1 for a summary of their study and also of themes in studies by Bikson and Gutek 1994; Ellis 1992; Fairhurst, Green, and Courtright

1995 and Miller et al. 1994.) They include issues related to managers' behaviors and communication; general communication; participation practices; vision; and expectations. Other research has called attention to these and other themes such as willingness or readiness for change; impacts of uncertainty and stress caused by change; and politics. Less attention has been paid to factors that tend to encourage success aside from a good deal of research on the effects of involvement and participation. What does exist about achievement of successful results has been dominated by a focus on a few specific types of change. In our review of literature (Lewis and Seibold 1998), David Seibold and I found that of the 18 works examining practice advice for success in change, 11 addressed the implementation of new technologies, and 7 addressed manufacturing technologies. It will be hard to determine general theories of success and failure of change until more studies are conducted using broader samples (Table 4.2).

Table 4.2 Factors predicting failure and success of change programs. Factors Predicting Failure

In a study (Lewis 2000) with an international sample of 76 implementers in for‐profit, nonprofit, and governmental sectors implementing a broad sample of different types of changes (e.g. management programs, reorganization, technologies, customer programs, merger, quality programs, recruitment programs, and reward programs), I found that implementers tended to identify potential problems that might cause failure in terms of fear or anxiety of staff; negative attitudes; politics; limited resources; and lack of enthusiastic support. Problems that implementers identified as having the largest impact on perceived success of change programs were those concerning the functioning of the implementation team and overall cooperation of stakeholders. However, they also considered these kinds of problems to be least anticipated and the least encountered.

A large body of work on important contingencies that impact failure or success of planned change concerns resistance to change. We will return to this topic in Chapter 6, but for now will note some of the general trends in research on resistance. Whether resistance is a predictor of success or failure is debated in the literature. While that may sound counterintuitive, Markus (1983) points out a reasonable explanation, “[resistance can be functional] by preventing the installation of systems whose use might have on‐going negative consequences” (p. 433). Essentially, resistance can be the manifestation of a correct judgment that the change is a bad idea for the organization. Piderit (2000) and Dent and Goldberg (1999) have also suggested that the notion of “resistance to change” as a vilified concept – the ultimate archenemy of implementers – be retired. Piderit's complaints about how the concept has been used in the literature includes:

Largely positive intentions of “resistors” are generally ignored in the research

Dichotomizing responses to change as “for” or “against” oversimplifies the potential attitudinal responses that are possible

The “resistance” term has lost a clear, core meaning in the multiple ways it has been used in the literature.

Piderit points out through her review that resistance has typically been viewed as something less powerful stakeholders do to slow down or sabotage a change effort. She argues that the language of resistance tends to favor implementers viewing those who oppose change as obstacles to success.

Two major concerns arise from this standard treatment of resistance. First, thinking of resistance as an obstacle to “right thinking” blinds the implementer to potentially useful observations of flaws in the change initiative. That is, if implementers are not open to the possibility that the change program might be flawed, and they treat any negative commentary as mere resistance, it is easy to dismiss it without consideration. Efforts are directed at fixing the resistors rather than reconsidering or altering the change initiative itself. Piderit quotes Krantz (1999, p. 42) on the use of the concept of resistance in organizations as “a not‐so‐disguised way of blaming the less powerful for unsatisfactory results of change efforts.” Piderit refers to this tendency as the fundamental attribution error (discussed above as the wrongful attribution of cause and effect). Evidence that practitioners are guided towards such an error abounds in the practice‐oriented literature. Popular press books on change implementation often have sections or chapters devoted to resistance to change. Many present their advice about strategies and specific tactics in terms of their ability to reduce or forestall resistance (Lewis et al. 2006).

A second concern about resistance as it is typically used concerns cueing behavior. Implementers who assume resistance in stakeholders may actually promote that response. Think of the last time someone close to you started their sentence with “I know you are going to hate this, but …” It usually sets up an automatic thinking process for you to search for the worst interpretation of what you hear next. A similar reaction may be triggered when implementers introduce change efforts with warnings of how “none of us will like this but” or “this will be a challenge for some of you.” Zorn, Page, and Cheney (2000) provide an example of this in their study of the cultural transformation by Ken, the manager, who introduced change by telling his subordinates they should be “scared, frightened, and excited of the changes that are about to happen” (p. 530).

We can be certain in considering resistance in change initiatives that a good deal of noncompliant behavior is considered problematic by implementers and that from their perspectives much of it is believed to be born of ignorance, fear, stubbornness, or some political motive. For some more enlightened implementers, signs of resistance may be signals that the change has flaws or needs adjustment so that it can be used in a successful way. Such implementers might treat those who raise objections or concerns about the change as loyal, committed, and/or ethical stakeholders who have the organization and its stakeholders uppermost in mind. In either case, the resistance and the reactions to that resistance by implementers and other stakeholders certainly have large impacts on change initiatives.

Another research area pointing to important sources of explanation for success and failure concerns managers' expectations and influence. King (1974) conducted a field study in which managers' expectations for success or failure of an organizational change effort were manipulated (some being led to believe success was more likely; some being led to believe success was less likely). Findings revealed that the results were related more to the managers' expectations than to qualities of the change program itself. Other research has pointed to the importance of managers' cues and encouragement in the behavioral and attitudinal responses of stakeholders (Isabella 1990; Leonard‐Barton and Deschamps 1988).

Conclusion

This chapter has focused our attention on various ways in which organizations perceive, enact, and assess outcomes and results. We have seen that assessment of outcomes is a very important strategic activity that aids in planning, hindsight learning, and course‐correction. However, we have also noted that assessment can be a very difficult task. Assessment of outcomes in organizations in general can be fraught with challenges in understanding the moving target of goals; the politicization of goal assessment; the attribution of error; and the problems associated with timing and means of assessing outcomes. In the context of organizational change, different stakeholders can come to widely different assessments of outcomes. Also, the material conditions of stakeholders of change can vary widely.

Change outcomes have been treated in different ways in the literature, including focus on “original goals” as baseline for comparison (e.g. fidelity); focus on the degree of implementation or outcome achievement; measurement of the similarity of adoption of change across users (e.g. uniformity); and in terms of the genuine “buy‐in” of key stakeholders (e.g. authenticity). Further, scholars have measured unintended consequences of change programs that can sometimes create additional challenges and burdens for both organizations and individual stakeholders even when overall intended outcomes and results are achieved.

A number of factors have been identified in the change literature as having predictive value in explaining and accounting for failure and success. Most of the research has explored predictors of failure, with a special focus on “resistance.” In Chapter 6 we return to the topic of resistance in some detail.

This review and discussion of outcomes of change processes has called attention to the importance of multiple perspectives in defining and assessing “what has happened” as a result of initiating change. Stakeholders and implementers have various perspectives on those outcomes; may certainly differ on how and when to assess them; and may even be self‐conflicted as to assessing them at any given point. Understanding that “calling” a success or failure in a change process is a highly social activity is an important first step in grappling with the challenges of measuring outcomes – a topic we return to in Chapter 8.

In the 2007 model (Figure 3.1), stakeholder concerns, assessments of each other, and stakeholder interactions are driven by the strategic communication strategies enacted by implementers and stakeholders. As discussed in Chapter 2, implementers and stakeholders make use of different strategies to disseminate information and solicit input. In Chapter 5 we will discuss a more nuanced view of these general strategic approaches, among others.

CHAPTER 3: 3 (Lewis)A Stakeholder Communication Model of Change

People do not always argue because they misunderstand one another, they argue because they hold different goals

William H. Shyte, Jr.

Would you persuade, speak of interest, not of reason

Benjamin Franklin

If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend

Abraham Lincoln

We all have stakes in organizations. Only someone living a Thoreau‐like existence on Walden's Pond with no contact with resource providers, social groups, political affiliations, or proximity to government, business, or any vestige of society could claim no stakes in organizations. As shown in the examples already presented in this book, organizations often have diverse stakeholders both within and without the identifiable boundary of operation. Employees, customers, suppliers, governments, and competitors are obvious types of stakeholders who demand things from organizations; depend on or are effected by organizational operations; and often provide comment on what organizations do. However, the picture of a given organization's stakeholders can be much more complex than this since stakeholders are not always obvious to or acknowledged by organizations. Further, how we are perceived or self‐perceive our stakes and stakeholder status for a given organization can be complex. We may play more than one role in an organization simultaneously (e.g. customer and employee; community member and volunteer) making the relative demands of groups of stakeholders quite dynamic and potentially difficult to manage both for organizations and for stakeholders.

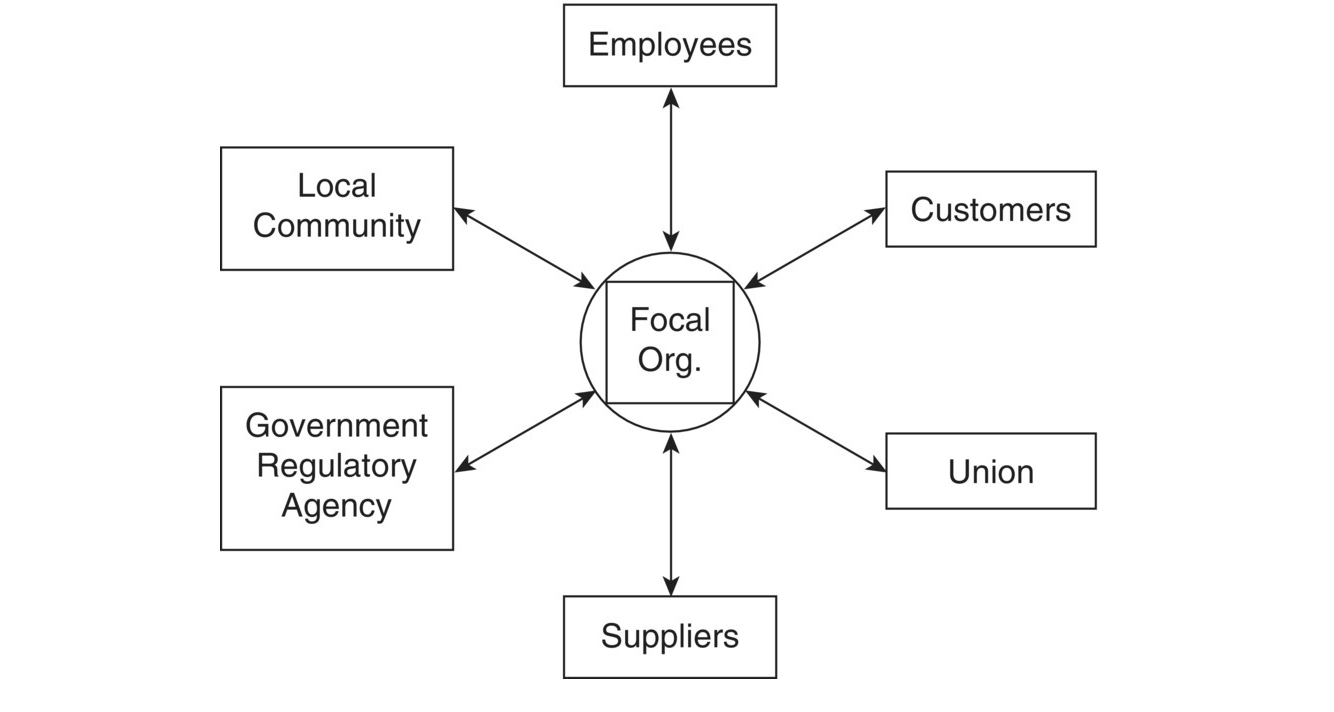

In this chapter, we will explore a model (see Figure 3.1) of change processes in the context of stakeholder communication that frames this book. We will first discuss the importance of Stakeholder Theory and introduce its basic tenets, as well as some novel ways to view the “map” of stakeholders relevant to any given change effort. Second, we will explore key roles that stakeholders play during change, pointing to both formal and informal roles that stakeholders may play in the processes of change. Third, we will briefly tour the model. Each of the major parts of the model including components and relationships among the components will be developed in later chapters.

Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder Theory is aimed at explaining how organizations map the field of potential stakeholders and then decide strategic action in managing relationships with various groups of stakeholders. These relationships are usually conceptualized as a hub and spokes (see Figure 3.2). In this depiction, the organization is at the center of the network and has individual, independent relationships with each of its stakeholder groups. We can compare this to how we might think of our network of friends. We might draw ourselves at the center and then draw a line to each set of friends (my friends at school, my friends at work, my friends from high school, my friends of my partner/spouse). Of course this depiction ignores the fact that friend groups can be overlapping, that friends may have relationships with other friends in other groups, and that each other individual may see the network completely from their own perspective (e.g. placing themselves at the center).

Figure 3.2 Hub and spokes model of stakeholder relationships.

Stakeholder Theory can be thought of as a family of perspectives launched by Edward Freeman in his now classic book, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (1984). Three main branches of this perspective have developed in the literature:

The descriptive approach depicts existing relationships with stakeholders

The instrumental approach focuses on how organizational actions shape stakeholder relationships (e.g. certain strategies with stakeholders are associated with certain outcomes: Jones and Wicks 1999)

The normative approach concerns moral and ethical obligations of managers to various stakeholders. Scholarship in this vein is exemplified in corporate social responsibility

(CSR) literature (cf. Donaldson and Preston 1995; Jennings and Zandbergen 1995).

Stakeholder Theory is centrally concerned with how organizations allocate stakes and attention to various recognized stakeholders. Identifying “important” or “critical” stakeholders is an important part of that calculus. Theorizing from an instrumental perspective of Stakeholder Theory, Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997) suggest that stakeholders be defined according to three attributes: (i) power (the ability of a stakeholder to impose will), (ii) legitimacy (a generalized assessment that a stakeholder's actions are desirable, proper, or appropriate), and (iii) urgency (the degree to which a stakeholder's claims are time‐sensitive, pressing, and/or critical to the stakeholder). Those stakeholder groups that are perceived to possess all three characteristics are labeled definitive stakeholders (Mitchell, Agle and Wood 1997). You can think of stakeholder relationships as you do friends in a friendship network where we allocate how much time, money, attention, and care (friendship resources) we give to each of group of friends. In a friendship model, our “best friends” would be our most important or “definitive” friends. However, we should remember that organizations don't necessarily “like” or “prefer” definitive stakeholders. Compare this to your personal friendship network. Your own “definitive” friends group may be one that you cannot ignore. You may include your in‐laws in that group because they are highly present in your life, are part of your spouse's family, and demand a good deal of your time. You might prefer to hang out with your buddies from high school, but that may not be the allocation of time, care, and attention that you make.

Mitchell and coauthors argue that organizational leaders have a clear and immediate requirement to focus their attention and resources on definitive stakeholders' needs. An example of a definitive stakeholder for those organizations that are part of Homeless Net might be the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) (see Highlight Box 3.1). HUD provides a large amount of funding for municipalities to spend on affordable housing and shelter. Without HUD funding, many cities and counties could not afford to execute their missions to serve homeless persons. In order to secure the funding, applicants must abide by the time schedule, eligibility requirements, reporting requirements, guidelines, and procedures that HUD lays out. HUD fulfills all of Mitchell et al.'s requirements to be a definitive stakeholder for this group of agencies because it has legitimacy as a federal agency; power, as a major source of funding; and urgency, in that it demands timely application and reporting in order for the provider agencies to earn funding. HUD cannot be ignored or put off, given this status.

Figure 3.2 Hub and spokes model of stakeholder relationships.

Stakeholder Theory can be thought of as a family of perspectives launched by Edward Freeman in his now classic book, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (1984). Three main branches of this perspective have developed in the literature:

The descriptive approach depicts existing relationships with stakeholders

The instrumental approach focuses on how organizational actions shape stakeholder relationships (e.g. certain strategies with stakeholders are associated with certain outcomes: Jones and Wicks 1999)

The normative approach concerns moral and ethical obligations of managers to various stakeholders. Scholarship in this vein is exemplified in corporate social responsibility

(CSR) literature (cf. Donaldson and Preston 1995; Jennings and Zandbergen 1995).

Stakeholder Theory is centrally concerned with how organizations allocate stakes and attention to various recognized stakeholders. Identifying “important” or “critical” stakeholders is an important part of that calculus. Theorizing from an instrumental perspective of Stakeholder Theory, Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997) suggest that stakeholders be defined according to three attributes: (i) power (the ability of a stakeholder to impose will), (ii) legitimacy (a generalized assessment that a stakeholder's actions are desirable, proper, or appropriate), and (iii) urgency (the degree to which a stakeholder's claims are time‐sensitive, pressing, and/or critical to the stakeholder). Those stakeholder groups that are perceived to possess all three characteristics are labeled definitive stakeholders (Mitchell, Agle and Wood 1997). You can think of stakeholder relationships as you do friends in a friendship network where we allocate how much time, money, attention, and care (friendship resources) we give to each of group of friends. In a friendship model, our “best friends” would be our most important or “definitive” friends. However, we should remember that organizations don't necessarily “like” or “prefer” definitive stakeholders. Compare this to your personal friendship network. Your own “definitive” friends group may be one that you cannot ignore. You may include your in‐laws in that group because they are highly present in your life, are part of your spouse's family, and demand a good deal of your time. You might prefer to hang out with your buddies from high school, but that may not be the allocation of time, care, and attention that you make.

Mitchell and coauthors argue that organizational leaders have a clear and immediate requirement to focus their attention and resources on definitive stakeholders' needs. An example of a definitive stakeholder for those organizations that are part of Homeless Net might be the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) (see Highlight Box 3.1). HUD provides a large amount of funding for municipalities to spend on affordable housing and shelter. Without HUD funding, many cities and counties could not afford to execute their missions to serve homeless persons. In order to secure the funding, applicants must abide by the time schedule, eligibility requirements, reporting requirements, guidelines, and procedures that HUD lays out. HUD fulfills all of Mitchell et al.'s requirements to be a definitive stakeholder for this group of agencies because it has legitimacy as a federal agency; power, as a major source of funding; and urgency, in that it demands timely application and reporting in order for the provider agencies to earn funding. HUD cannot be ignored or put off, given this status.