Short paper for Econ. Attachments below.

Biodiversity Conservation, Economic Growth and Sustainable Development: An Abridged Summary

Richard E. Rice, Ph.D.

University of Maryland Global Campus, Silver Spring, MD, USA. President, Conservation Agreement Fund, www.conservationagreementfund.org.

The following is a summary of a longer paper published as: Rice. RE. Biodiversity Conservation, Economic Growth and Sustainable Development. In Biodiversity of Ecosystems. Intech Open. 9 August 2021. Open access, peer reviewed book chapter. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.99298 1. IntroductionA growing economy has long been regarded as important for social and economic progress. And indeed, much of what we value in society is the product of economic growth. It is becoming increasingly clear, however, that our current pattern of growth involves significant social and environmental costs. This chapter examines the conflict between growth and the conservation of biological diversity. Included is a discussion of what growth means and a review of the connection between economic growth, sustainable development, and the conservation of nature. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the role that market-based economic policies can play in helping to catalyze necessary change.

2. What growth meansThe standard definition of economic growth is a sustained increase in a nation’s real (inflation adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP). GDP is the monetary value of all goods and services produced in a country each year. In recent years, real GDP growth in the U.S. has averaged around 2% which means that the economy doubles in size every 36 years [1].

2.1 Why grow?

Proponents of economic growth focus on its many benefits, including higher standards of living and the ability to devote more resources to things like health care and education. Increases in sanitation, nutrition, and longevity have all been possible due to economic growth. Since 1800, life expectancy has grown from less than 30 years to more than 70 with eradication of childhood disease and improvements in medicine and nutrition [2]. Vast changes in material abundance have also been possible due to economic growth allowing many the things that only the wealthy could aspire to in the past.

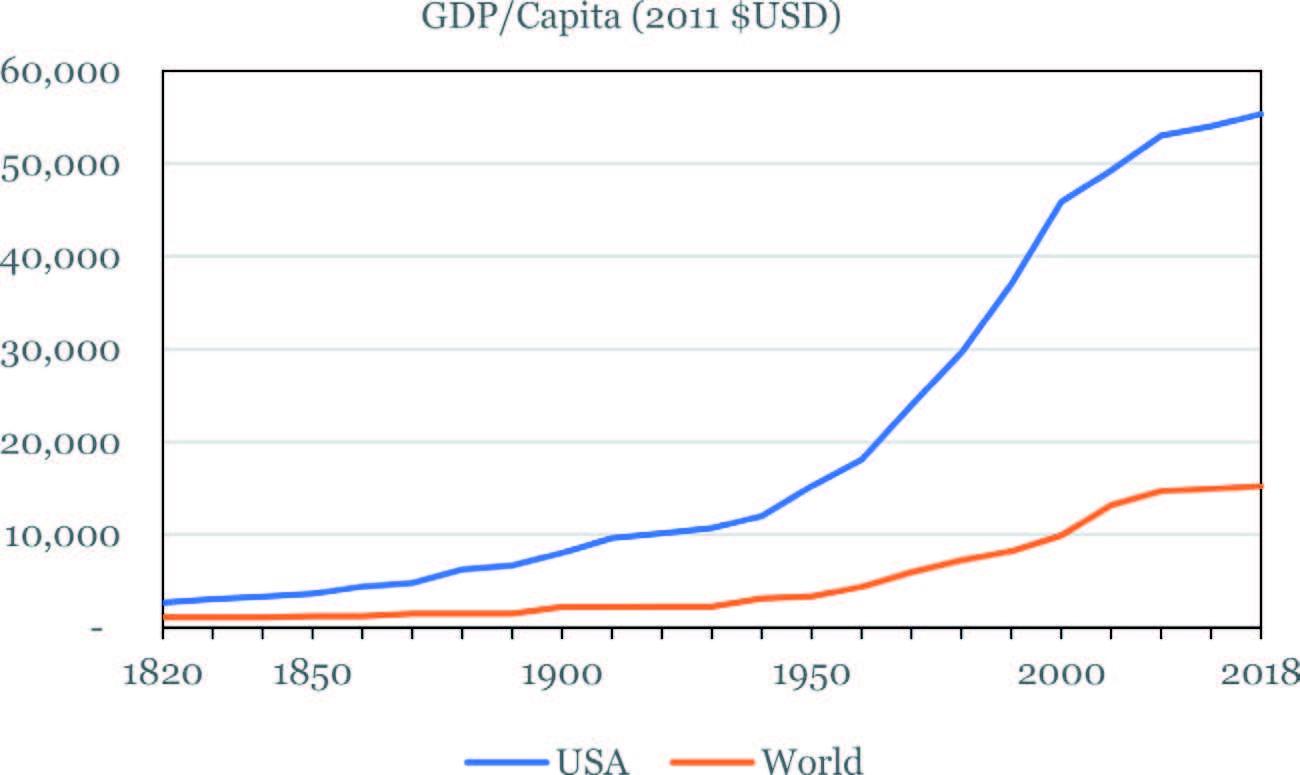

Though something we now take for granted economic growth is a very recent phenomenon. Widespread economic prosperity (as measured by GDP per capita) has only been achieved in the past couple hundred years and as shown in Figure 1, has only really taken off in the past 50 years [3].

2.2 The downsides to growthGiven its many benefits, it is little wonder that economic growth is a focus of global economic policy. Growth, however, has its costs. Environmental destruction and impacts on biodiversity are perhaps the most obvious, but there are also conflicts between economic growth and national security and international stability, and ultimately, economic sustainability itself.

Growing economies consume natural resources and produce wastes. This results in habitat loss, air and water pollution, climate disruption, and other environmental threats, threats which are becoming more apparent as economic activity encounters more and more limits. The depletion of groundwater and ocean fisheries are examples as are shortages of fresh water, and the global spread of toxic compounds such as mercury, chlorofluorocarbons, and greenhouse gases.

Figure 1. The history of Economic growth: GDP/capita, 1820–2018 [3].

Environmental impacts, of course, are not unconnected to society at large. Things like climate change and the extinction crisis have economic impacts and these in turn can threaten national security and international stability. Such threats are often made worse by inequality. Not everyone benefits equally from growth and some have arguably not benefitted at all. The problem of growing inequality is certainly an issue in the U.S. where the nation’s top 10 percent now average more income than the bottom 90 percent [4]. But it is also clearly a problem globally.

Climate change, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation generally are certain to accentuate such inequalities in the future with unavoidable impacts on social unrest, national security, and international stability. The national security implications of these issues were starkly presented in a recent report commissioned by the U.S. Army [5]. According to the study, America could face a grim series of events triggered by climate change involving drought, disease, failure of the country’s power grid and a threat to the integrity of the military itself, all within the next two decades. The report also projects that sea level rise in the future is likely to “displace tens (if not hundreds) of millions of people, creating massive, enduring instability” and the potential for costly regional conflicts [5].

All of the above issues have clear implications for economic sustainability – a healthy environment and international stability, after all, are the foundations for a healthy economy. We need healthy soils for agriculture, healthy oceans for fisheries, clean air and water and a stable political environment for international trade, all of which are threatened by unrestrained growth [6].

3. The quest for sustainable developmentIncreasing awareness of the limitations of growth has led to much discussion of sustainable development. This concept is most commonly associated with a report published by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987. In that report sustainable development is defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [7]. Since the publication of this report, the idea of sustainable development has gained a solid footing in the popular imagination.

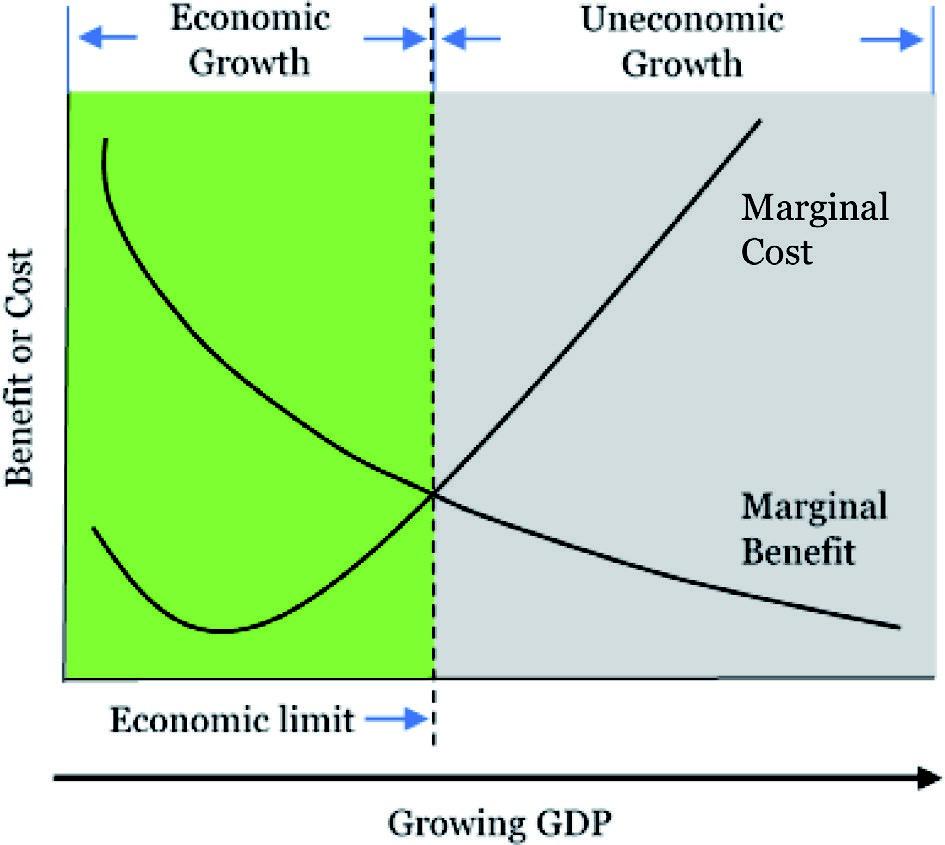

Despite its popularity, the precise meaning of sustainable development is somewhat elusive. From an economic perspective a simple definition might be that growth should proceed so long as the marginal benefits exceed the marginal costs (Figure 2). Marginal cost is the cost of a small increase in an activity and marginal benefit is the additional benefit from that increase. Figure 2 shows the marginal costs and benefits of growth in GDP. Since the benefits tend to decline and the costs to rise with additional GDP growth, the sweet spot is to grow until the marginal costs are exactly equal to the marginal benefits. Any increase in GDP up to this point is “economic growth” whereas growth in GDP past this point, where costs rise above benefits is uneconomic [6].

3.1 The problems with GDPSuch definitions are all well and good, but problems arise in discerning when and where costs begin to exceed benefits. This, in turn, is made more difficult by the way in which we measure growth.

Figure 2. Economic and uneconomic growth in GDP [6].

Ironically, GDP, our global standard measure of growth, was never intended as a measure of costs and benefits. Instead, it is simply a gross tally of market output with no distinction made between output that adds to well-being and output that diminishes it. Instead of separating costs from benefits GDP assumes that all monetary transactions by definition add to social welfare [8].

GDP also excludes everything that happens outside formal markets and therefore ignores many things that clearly benefit society such as volunteer work and unpaid work in households like childcare and elder care. Much of the value of environmental services is ignored as well.

This method of accounting leads to some very counterintuitive results, including the fact that GDP increases with polluting activities and then again with clean-ups, crime and natural disasters are treated as economic gain, and the depletion of natural capital is treated as income [8].

4. Policies to promote a more sustainable futureThe above discussion of how we define and measure sustainability, of course, begs the question of how we get from here to there. Clearly, a part of the answer lies in the measures and definitions themselves. We cannot correct problems if our measures conceal them, and we will never achieve sustainability if we do not define it as an explicit objective.

Nevertheless, this still leaves the difficult work of developing policies to help promote more sustainable outcomes. Experience and the existence of market failures suggests that we cannot leave solutions to the market alone. That said, it would be a mistake to underate the potential for productively using market forces in our search for solutions. Policies based on economic incentives in particular offer an extremely powerful and effective set of options.

Two examples in areas that matter to biodiversity are conservation agreements and carbon pricing. Both illustrate how incentive-based policies can help provide simple, cost-effective, and scalable solutions to environmental problems.

4.1 Conservation agreementsConservation agreements are performance-based agreements in which resource owners commit to a concrete conservation outcome – usually the protection of a particular habitat or species – in exchange for benefits designed to give them an ongoing incentive to conserve [9]. The type of benefits provided vary but can include technical assistance, support for social services, employment in resource protection, or direct cash payments.

One of the great advantages of this approach is that the terms of agreements are flexible and can therefore be tailored to a particular setting. This flexibility makes conservation agreements a very scalable approach that can be implemented on private and indigenous lands outside traditional protected areas as well as on lands managed by national governments. In addition, whereas the creation of a traditional park or protected area requires a long, complex political process, conservation agreements, as a market-based approach, make park creation more akin to a standard business transaction, and this, in turn, makes park creation much more rapid and efficient.

Conservation agreements were first piloted in 2001 in the context of a timber concession in Guyana [9]. Since then, they have been implemented in a wide variety of settings in roughly 20 countries around the world [10]. Examples include agreements focused on particular species as well ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves, and in the Solomon Islands, the largest uninhabited island in the South Pacific [10, 11].

4.2 Pricing carbonCarbon pricing is another example of an incentive-based policy that relates to biodiversity. While this approach does not target biodiversity directly, it is perhaps the most important single policy affecting all life on Earth. When it comes to conservation, and so much else, unless we effectively tackle climate change very little else will matter.

Although there are many ways of putting a price on carbon, by far the simplest and most effective is a tax imposed on fuel suppliers (e.g., oil and gas producers). Once taxed, fuel suppliers raise their prices and, in this way, the higher prices ripple through the whole economy. There is no way to evade the tax and there is nothing to monitor or enforce (other than whether energy producers pay their taxes). Across the economy the cost of energy-intensive goods and services would rise giving both businesses and consumers an incentive to conserve.

One of the many advantages of a carbon tax is that it ensures that emission reductions are achieved at least cost to society. The reason is that unlike regulations that require everyone to adopt a particular technology or reduce their emissions by a certain amount, carbon taxes allow for the fact that some entities can reduce their emissions at a lower cost than others. This flexibility offers the opportunity for substantial cost savings.

Regulations alone, for example, can be twice as expensive as a carbon tax per ton of carbon abated while reducing far fewer emissions [12]. Similarly, subsidies (e.g., for electric vehicles) are unavoidably wasteful since they cannot target those who will only be motivated to buy because of the subsidy. If a tax credit of $7,500 convinces only one in four people to buy a hybrid electric vehicle, for example, the effective cost of the incentive is four times the subsidy or $30,000 – more than the price of many plug-in hybrids [13]. Such subsidies also tend to disproportionately benefit high-income households and while hybrids themselves emit less carbon than conventional cars, if the source of power used to charge them comes from coal they will raise carbon emissions rather than reduce them [14].

Most carbon tax proposals also now involve offsetting rebates so they do not disadvantage the poor who spend a larger percentage of their income on energy. Many proposals, in fact, would leave the majority of households better off with the tax than without it. In effect, such a “tax” would pay people for doing the right thing.

5. Summary and conclusionThe past two centuries of economic growth have provided the world with many benefits. Our lives are longer and healthier. Childhood diseases that afflicted our parents are largely a thing of the past. The creative explosion of the last few decades has yielded advances in medicine, the arts, technology and more. All these things are the benefits of economic growth.

There are, however, downsides to economic growth that put our past progress and the future of life in jeopardy. The question is how to moderate these impacts while still maintaining a focus on advancing economic security and the quality of life.

Part of the answer to this question is in developing better indicators of how economic activity is affecting the things we care about. Having a global standard measure like GDP that ignores the value of nature and counts both pollution and clean up as progress is certain to steer us in the wrong direction. Dethroning GDP and work on replacements are worthy endeavors. Yet they still leave us with the hard work of developing appropriate policies for the future.

How we proceed in this regard will make a difference. Unconstrained markets are not likely to produce a happy ending, but this does not mean that we should ignore the potential for using markets and incentives in our search for solutions.

The good news is that we have some extremely simple and powerful tools at our disposal. A single, small change in the tax code can reorient the entire economy away from carbon. And conservation agreements can be flexibly implemented almost everywhere they are needed. While funding these efforts will not be inexpensive there is ample global willingness and ability to pay for conservation and no shortage of those in a position to conserve who are willing to accept payment.

The challenges are great, but many of the tools needed to address them are at hand. We need only choose to put them to use.

ReferencesTrading Economics. United States GDP Annual Growth Rate. 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/ gdp-growth-annual

Roser, M, Ortiz-Ospina, E., Ritchie, H. Life Expectancy [Internet]. Our World in Data. 2019. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

Boldt, J, Luiten van Zanden, J. Madison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update [Internet]. Madison Project Working Paper WP-15. [updated 2020; cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/ historicaldevelopment/ maddison/ publications/ wp15.pdf

Saez, E. Striking it richer: The evolution of top incomes in the U.S [Internet]. Unpublished update of report published in Pathways Magazine, Stanford Center for the Study of Poverty and Inequality, Winter 2008, 6-7. U.C. Berkeley, Department of Economics. 2020. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/saezUStopincomes-2018.pdf

Brosig, M. Frawley, P, Hill, A, Jahn, M, Marsicek, M, Paris, A, Rose, M, et al. Implications of climate change for the U.S. Army [Internet]. United States Army War College. Carlisle, PA; 2019. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://climateandsecurity.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/implications-of-climate-change-for-us-army_army-war-college_2019.pdf

CASSE, 2021b. The downside of economic growth [Internet]. Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy. 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. https://steadystate.org/discover/ downsides-of-economic-growth/

Brundtland, G. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future [Internet]. United Nations; 1987. United Nations General Assembly document A/42/427. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/ documents/ 5987ourcommon-future.pdf

Hansen, Jay. Overshoot Loop: Evolution Under the Maximum Power Principle [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. https://dieoff.com/page11.htm

Hardner, J, Rice R. Rethinking green consumerism. SciAm. 2002 May. 287:89-95.

CI. What on Earth is a ‘Conservation Agreement’ [Internet]. Conservation International. 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. https://www.conservation.org/blog/ what-on-earth-is-a-conservationagreement

CAF. Conservation Agreement Fund [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. https://conservationagreementfund.org/projects/

Rossetti, P, Bosch, D, Goldbeck, D. Comparing effectiveness of climate regulations and a carbon tax [Internet]. Unpublished research report. American Action Forum, Washington, D.C.; 2018. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.americanactionforum.org/ research/comparing-effectiveness- climate-regulations-carbon-tax123/#ixzz6wCB4GgcU

Metcalf, GE. On the economics of a carbon tax for the United States [Internet]. Brookings Institution. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Spring 2019. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/on-the-economics-of-a- carbon-tax-for-the-united-states/

Tessum, C., Hill, J. Marshall, D. Air quality impacts from light-duty transportation [Internet]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014 Dec. 111 (52):18490-18495. [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.pnas.org/content/111/52/18490 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1406853111