This is a Humanities class, I did not see the option below. Book: Boundless Art History by Lumen Corporation Chapters: 19-20-21 Choose a topic from Module 1, Which covers Non-Western Art that you

Africa in the Modern Period

Top of Form

Search for:

Bottom of Form

Religious Art in Africa

African Art and the Spirit World

Beliefs about the spirit world are deeply embedded in traditional African culture, but were heavily influenced by Christianity and Islam.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the role of African masks, statues, and sculptures in relation to the spirit world

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Most traditional African cultures include beliefs about the spirit world, which is widely represented through both traditional and modern art such as masks, statues, and sculptures.

Wooden masks are often used to depict deities or ancestors; in many traditions, they are believed to channel spirits when worn by ceremonial dancers.

Statues and sculptures are also used to represent, connect to, or communicate with spiritual forces.

Today, Africans profess a wide variety of religious beliefs, the most common of which are Christianity and Islam; perhaps less than 15% still follow traditional African religions.

Despite the drastic decrease in native African religions, some modern art in Africa has worked to reincorporate traditional spiritual beliefs, such as in modern Makonde Art depicting spirits.

Key Terms

receptacle: A container.

sanctuaries: Consecrated (or sacred) areas of a church or temple.

Background

Like all human cultures, African folklore and religion is diverse and varied. Culture and spirituality share space and are deeply intertwined in most African cultures, which have been heavily influenced by the introduction of Christianity and Islam during the era of European colonization. Most traditional African cultures include beliefs about the spirit world, which is widely represented through both traditional and modern art such as masks, statues, and sculptures. In some societies, artistic talents were themselves seen as ways to please higher spirits.

Traditional Influences on Contemporary Religious Art

Masks and Rituals

Wooden masks, which often take the form of animals, humans, or mythical creatures, are one of the most commonly found forms of traditional art in western Africa. These masks are often used to depict deities or represent the souls of the departed. They may be worn by a dancer in ceremonies for celebrations, deaths, initiations, or crop harvesting. In many traditional mask ceremonies, the dancer goes into deep trance, and during this state of mind he or she is believed to communicate with ancestors in the spirit world. The masks themselves often represent an ancestral spirit, which is believed to possess the wearer of the mask. Most African masks are made with wood and can also be decorated with ivory, animal hair, plant fibers, pigments, stones, and semi-precious gems.

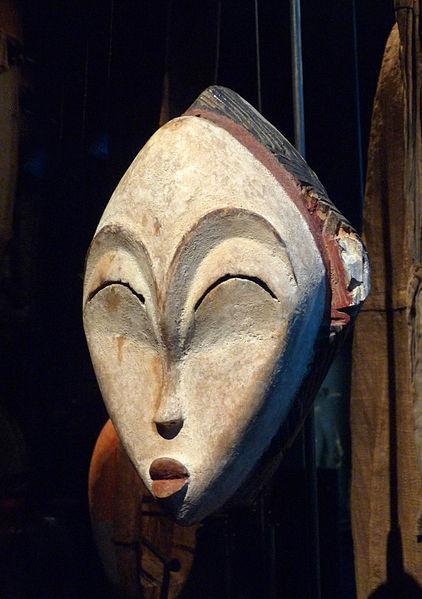

Mask from Gabon: A traditional mask from Gabon.

Statues and sculptures are also used to represent or connect to spiritual forces. For example, Bambara statuettes, such as the Chiwara, are used as spiritually charged objects during ritual. During the annual ceremonies of the Guan society, a group of up to seven figures, some dating back to the 14th century, are removed from their sanctuaries by the elder members of the society. The wooden sculptures, which represent a highly stylized animal or human figure, are washed, re-oiled and offered sacrifices. The Kono and Komo societies use similar statues to serve as receptacles for spiritual forces. The Igbo would traditionally make clay altars and shrines of their deities, usually featuring various figures. In the Kingdom of Kongo, nkisi were objects believed to be inhabited by spirits. Often carved in the shape of animals or humans, these “power objects” were believed to help aid in the communication with the spirit world.

Modern Religion

Today, the countries of Africa contain a wide variety of religious beliefs, and statistics on religious affiliation are difficult to come by. Christianity and Islam make up the largest religions in contemporary Africa, and some sources say that less than 15% still follow traditional African religions. Despite the drastic decrease in native African religions, some modern art in Africa has worked to reincorporate traditional spiritual beliefs. For example, modern Makonde Art has turned to abstract figures in which spirits, or Shetani, play an important role.

Modern Makonde carving in ebony: Modern Makonde sculptures often depict spirits, or Shetani.

Masks in the Kalabari Kingdom

Culture and artistic festivities of the Kalabari Kingdom involve the wearing of elaborate outfits and carved masks to celebrate the spirits.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the role of the spiritual in the masks of the Kalabari Kingdom

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Kalabari Kingdom was an independent trading state of the Kalabari people, an Ijaw ethnic group, in the Niger River Delta. Today it is recognized as a traditional state in what is now Rivers State, Nigeria.

Although the Ijaw are now primarily Christians, they also maintain elaborate traditional religious practices.

Veneration of ancestors plays a central role in Ijaw traditional religion, while water spirits figure prominently in the Ijaw pantheon. In addition, the Ijaw practice a form of divination in which recently deceased individuals are interrogated on the causes of their death.

The role of prayer in the traditional Ijaw system of belief is to maintain the living in the good graces of the water spirits among whom they dwelt before being born into this world.

Each year, the Ijaw hold celebrations involving masquerades that last for several days in honor of the spirits.

Ijaw men wearing elaborate outfits and carved masks dance to the beat of drums and manifest the influence of the water spirits through the quality and intensity of their dancing.

Key Terms

enculturation: The process by which an individual adopts the behavior patterns of the culture in which he or she is immersed.

kin: Race; family; breed; kind.

Introduction: The Kalabari

The Kalabari Kingdom, also called Elem Kalabari (New Shipping Port), or New Calabar by the Europeans, was an independent trading state of the Kalabari people, an Ijaw ethnic group, in the Niger River Delta. Today it is recognized as a traditional state in what is now Rivers State, Nigeria. As well as participating in trade, the Ijaw have traditionally been a fishing and farming culture.

Culture and Art

Although the Ijaw are now primarily Christians (95% profess to be), with Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism being the varieties of Christianity most prevalent among them, they also maintain elaborate traditional religious practices. Veneration of ancestors plays a central role in Ijaw traditional religion, while water spirits, known as Owuamapu, figure prominently in the Ijaw pantheon. In addition, the Ijaw practice a form of divination called Igbadai, in which recently deceased individuals are interrogated on the causes of their death. The Ijaw are also known to practice ritual acculturation, whereby an individual from a different and unrelated group undergoes rites to become Ijaw.

The Role of Ijaw Masks

Ijaw religious beliefs hold that water spirits are like humans, having personal strengths and shortcomings, and that humans dwell among the water spirits before being born. Each year, the Ijaw hold celebrations lasting for several days in honor of the spirits. Central to the festivities is the role of masquerades, in which men wearing elaborate outfits and carved masks dance to the beat of drums and manifest the influence of the water spirits through the quality and intensity of their dancing. Particularly spectacular masqueraders are believed to be possessed by the particular spirits on whose behalf they are dancing.

ljaw mask: Mask, Kalabari Ijo peoples, Nigeria, early 20th century, wood, pigment (National Museum of African Art).

Dogon Sculpture

Dogon sculpture primarily revolves around the themes of religious values, ideals, and freedoms.

Learning Objectives

Describe the characteristics of Dogon art, sculpture, and rituals, as well as the background and location of the Dogon culture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Dogon are an ethnic group living in the central plateau region of the country of Mali, in the West of the African continent, and are well known for their unique sculptures. Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or the hogon (spiritual leader).

Dogon sculptures are typically characterized by an elongation of form and a mix of geometric and figurative images.

The Dogon style has evolved into a kind of cubism: ovoid head, squared shoulders, tapered extremities, pointed breasts, forearms and thighs on a parallel plane, and hair stylized by three or four incised lines.

Key Terms

vessel: A general term for all kinds of craft designed for transportation on water, such as ships or boats.

Tellem: The people who inhabited the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali from the 11th through 16th centuries CE.

Introduction: The Dogon People

The Dogon are an ethnic group living in the central plateau region of the country of Mali, in the West of the African continent. They migrated to the region around the 14th century CE. They are best known for their religious traditions, wooden sculpture, architecture, and funeral masquerades. The past century has seen significant changes in the social organization, material culture, and beliefs of the Dogon, partly because Dogon country is one of Mali’s major tourist attractions.

Dogon Sculpture

Dogon art is primarily sculptural and revolves around religious values, ideals, and freedoms. Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or the hogon (a spiritual leader of the Dogon people). The importance of secrecy is due to the symbolic meaning behind the pieces and the process by which they are made. Dogon sculptures are typically characterized by an elongation of form and a mix of geometric and figurative images.

Dogon Sculpture: Dogon sculptures are typically characterized by an elongation of form and a combination of geometric and figurative images.

Themes

Themes found throughout Dogon sculpture consist of figures with raised arms, superimposed bearded figures, horsemen, stools with caryatids, women with children, figures covering their faces, women grinding pearl millet, women bearing vessels on their heads, donkeys bearing cups, musicians, dogs, quadruped-shaped troughs or benches, figures bending from the waist, mirror-images, apron-wearing figures, and standing figures. Signs of other contacts and origins are evident in Dogon art; the Dogon people were not the first inhabitants of the area, and influence from the Tellem, or the people who inhabited the region in Mali between the 11th and 16th centuries CE, is evident in the use of rectilinear designs.

Dogon art is extremely versatile, although common stylistic characteristics—such as a tendency towards stylization—are apparent on the statues. Their art deals with Dogon myths, whose complex ensembles regulate the life of the individual. The sculptures are preserved in innumerable sites of worship and personal or family altars, and often render the human body in a simplified way, reducing it to its essentials. Many sculptures recreate the silhouettes of the Tellem culture, featuring raised arms and a thick patina, or surface layer, made of blood and millet beer. The Dogon style has evolved into a kind of cubism: ovoid head, squared shoulders, tapered extremities, pointed breasts, forearms and thighs on a parallel plane, and hair stylized by three or four incised lines.

Uses

Dogon sculptures serve as a physical medium in initiations and as an explanation of the world. They serve to transmit an understanding to the initiated, who will decipher the statue according to the level of their knowledge. Carved animal figures, such as dogs and ostriches, are placed on village foundation altars to commemorate sacrificed animals, while granary doors, stools, and house posts are also adorned with figures and symbols. Kneeling statues of protective spirits are placed at the head of the dead to absorb their spiritual strength and to be their intermediaries with the world of the dead, into which they accompany the deceased before once again being placed on the shrines of the ancestors.

Mendé Masks

Mendé masks are commonly used in initiation ceremonies into secret Poro and Sande societies.

Learning Objectives

Discuss how Mendé masks are created and used by the Mendé people

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Mendé people are one of the two largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone; they belong to a larger group of Mandé peoples who live throughout West Africa.

The masks associated with the secret societies of the Mendé are probably the best known and most finely crafted in the region.

Masks represent the collective mind of Mendé community; viewed as one body, they are seen as the Spirit of the Mendé people.

The most important masks personify and embody the powerful spirits belonging to the medicine societies: the goboi and gbini of the Poro society (the secret society for men) and the sowei of the Sande society (the secret society for women).The features of a Sowei mask convey Mendé ideals of female morality and physical beauty; they are somewhat unusual because women wear the masks.

Key Terms

hale: Secret societies of the Mendé people.

![This is a Humanities class, I did not see the option below. Book: Boundless Art History by Lumen Corporation Chapters: 19-20-21 Choose a topic from Module 1, Which covers Non-Western Art that you 5]()

Background and Art of the Mendé People

The Mendé people are one of the two largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone, having roughly the same population as their neighbours the Temne people. Together, the Mendé and Temne both account for slightly more than 30% of the country’s total population. The Mendé belong to a larger group of Mande peoples who live throughout West Africa. Mostly farmers and hunters, the Mendé are divided into two groups: the halemo (or members of the hale or secret societies) and the kpowa (people who have never been initiated into the hale). The Mendé believe that all humanistic and scientific power is passed down through the secret societies.

Mendé art is primarily found in the form of jewelry and carvings. The masks associated with the secret societies of the Mendé are probably the best known and are finely crafted in the region. The Mendé also produce beautifully woven fabrics, which are popular throughout western Africa, and gold and silver necklaces, bracelets, armlets, and earrings. The bells on the necklaces are of the type believed capable of being heard by spirits, ringing in both worlds, that of the ancestors and the living.

Mendé Masks

Masks represent the collective mind of the Mendé community; viewed as one body, they are seen as the Spirit of the Mendé people. The Mendé masked figures are a reminder that human beings have a dual existence; they live in the concrete world of flesh and material things as well as in the spirit world of dreams, faith, aspirations, and imagination.

The standard set of Mendé maskers includes about a dozen personalities embodying spirits of varying degrees of power and importance. The most important of these personify and embody the powerful spirits belonging to the medicine societies: the goboi and gbini of the Poro society (the secret society for men), the sowei of the Sande society (the secret society for women), and the njaye and humoi maskers belonging to the eponymous medicine societies. The maskers of the Sande and Poro societies are responsible for enforcing laws and are important symbolic presences in the rituals of initiation and in public ceremonies that mark the coronations and funerals of chiefs and society officials.

Sowei Masks

The features of a Sowei mask convey Mendé ideals of female morality and physical beauty. They are somewhat unusual in that women traditionally wear the masks. The bird on top of the head represents a woman’s intuition that lets her see and know things that others can’t. The high or broad forehead represents good luck or the sharp, contemplative mind of the ideal Mendé woman. Downcast eyes symbolize a spiritual nature, and it is through these small slits that a woman wearing the mask would look out of. The small mouth signifies the ideal woman’s quiet and humble character. The markings on the cheeks are representative of the decorative scars girls receive as they step into womanhood. The neck rolls are an indication of the health of ideal women; they have also been called symbols of the pattern of concentric, circular ripples the Mendé spirit makes when emerging from the water. The intricate hairstyles reveal the close ties within a community of women. The holes at the base of the mask are where the rest of the costume is attached; a woman who wears these masks must not expose any part of her body, or it is believed a vengeful spirit may take possession of her.

When a girl becomes initiated into the Sande society (the Mendé secret society for women), the village’s master woodcarver creates a special mask just for her. Helmet masks are made from a section of tree trunk, often of the kpole (cotton) tree, and then carved and hollowed to fit over the wearer’s head and face. The woodcarver must wait until he has a dream that guides him to make the mask a certain way for the recipient. A mask must be kept hidden in a secret place when no one is wearing it. These masks appear not only in initiation rituals but also at important events such as funerals, arbitrations, and the installation of chiefs.

Helmet Mendé Mask: Helmet masks of the Mendé, Vai, Gola, Bassa and other peoples of the sub-region are the best documented instance of women’s masking in Africa. These masks are used by the Sande association, a powerful organization with social, political and religious significance. Although worn only by women, these masks, as is the case elsewhere in Africa, are carved by men.

Gbini Masks

Gbini is considered to be the most powerful of all Mendé maskers; it appears both at the final ceremony of the Poro initiation process for a son of the paramount chief and also at the coronation of funeral of a paramount chief. Because of its power, women are made to stand far back from gbini and if a woman accidentally touches it, she must be anointed with medicine immediately.

The Gbini wears a large leopard skin, which indicates its association with the paramount chief. The flat, round headpiece resembles the chief’s crown. The headpiece is constructed of animal hide stretched over a bamboo framework, and the hide is decorated with cowrie shells and black, white, and red strips of cloth that are worked into a geometric pattern. At the center is a round mirror. Several flaps that are similarly decorated hang down from the base of the headpiece and overlap the cape, which covers much of the wearer’s torso.

Gbini mask: Gbini mask, Mendé (wood, leopard skin, sheepskin, antelope skin, raffia fiber, cotton cloth, cotton string, cowry shells), from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

Africa’s influence on modern art/ April 9, 2019

AFRICAN ARTWORKS AND EARLY EUROPEAN CONTACT

African arts today have come to be admired by art aficionados from all over the world, but it has not always been this way. There was a time when artworks from Africa was not considered worthy enough to be even displayed in European art museums.

The Europeans at the time with their myopic view of artefacts from the continent, and assessment clouded by their supremacist and racist standpoint never even considered these artworks as art.

Furthermore, the significance or purpose of the African art objects of which the Europeans were ignorant of, did not help the situation.

Today not only are these same works of art appreciated, admired and proudly displayed the world over, but African arts have also come to influence the works of some great artists and ushered in the era of modern arts. Modern arts would not have existed without African arts.

Most artworks from Africa are mostly but not limited to masks, paintings, textiles, and statues. Africans used different materials depending on their environment to produce these works, materials like wood, clay, shells, ivory, bronze, gold, copper, clay, feathers, bark and raffia.

Artistic creations from Africa have some religious or ceremonial purposes and often times they are expressed as a combination of realism with the supernatural or downright abstract artistic expressions.

Sometimes the works feature distorted elongated and exaggerated figures; sometimes the items are covered with bright dissonant colours resulting in a colour clash that is not necessarily complimentary or pleasing to the eye. Sometimes the surfaces are a repetition of geometric patterns.

THE RISE OF AFRICAN ARTS

The 19th century was rife with the colonization and invasion of the African continent by the European powers; they assumed control of most of the continent including its traditional items. European countries that took part in the Scramble for Africa collected numerous objects which they took back to Europe.

These African artistic objects were not considered art initially but rather symbols of Europe’s imperial power. By the 1870s, European museums had already started exhibiting these African artefacts, not as art creations but rather as ethnographic artefacts of a less civilized people; the art objects were neither appreciated for their aesthetic nor expressive qualities, and the Europeans never understood the meaning or significance of these works.

Towards the turn of the century in the early 1900s, several colonial art exhibitions took place in Europe especially in France and Germany including the Universal Exhibition in Paris which showcased some African statues and masks.

These occasions afforded the public a chance to view a wide variety of many different African artworks.

Initial public reaction was a combination of awe and horror at what they perceived to be savage, frightful and weird objects. Despite the mixed feelings, some open-minded and intellectually far-sighted artists many of whom were dissatisfied with the norm of European art began drawing inspiration from these African artworks.

Meanwhile, the interest of the public in these so-called primitive or tribal artworks greatly increased, this fact is reflected in the sudden appearance of many of such African artefacts in various art museums all across Europe in the early 19th century, and a sharp rise in the number of art galleries that showcased such works.

Around 1905 artists in Paris and Germany began to reflect some African characteristics in their works; this type of fusion is what gave rise to modern arts as we know it.

Expressionist art movements came into being, and the art world as we know it took on a new and different approach to date all as a result of Africa’s artistic creations.

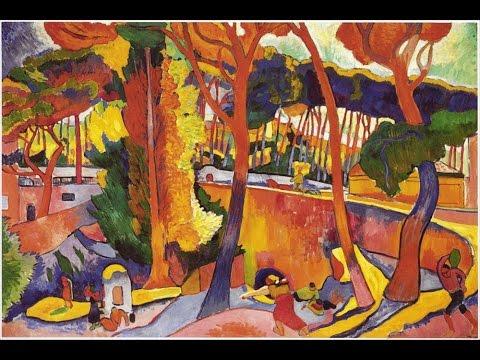

A Fauvism Painting by André Derain

THE INFLUENCE OF AFRICAN ARTS

During the first decade of the 20th century, Africa’s artistic influence shook the world of arts. Several expressionist art movements came into being. The German group Die Bruecke was founded in 1905 by artists like Kirchner, Heckel, Nolde, Schmidt-Rottluff, and Pechstein.

The group was noted for their bold use of clashing colours and distorted forms inspired by African arts. Radical young French painters like Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Rouault, and Dufy also followed suit. The term “Fauves” was used to describe their style.

CUBISM

Next, the term “Cubist” emerged in 1908 and was used to denote a series of paintings by Braque who was inspired by African arts, and later evolved to be applied as a label for a new style of art developed by Picasso and Braque, later joined by Gris and Léger. Cubism, in turn, influenced other artists like a German group “Der Blaue Reiter” founded in 1911 by Kandinsky, Marc, Campendonk, and Klee. Cubism also influenced the futurist school of Boccioni, Severini, and Carrá in France.

Both the Fauves and the Cubists came to know and greatly value African arts from their different points of view.

Within the space of a very short time, African artworks had already significantly started changing the world’s perception and creation of arts. Its influence on the art world was enormous.

It inspired revolutionary and new approaches to creating arts like Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso’s cubism which started between 1907 and 1908. And was derived from Africa’s unique artistic representation of different things into a single figure, which was a sharp departure from European academicism.

Both Picasso and Matisse collected African arts. Picasso had many African artworks in his private collections which inspired his creations. These artefacts mostly of sculptures and masks were obtained from countries like Nigeria, Mali, Gabon, Liberia, Congo and Coté d’ Ivoire. Matisse even travelled to Africa in pursuit of his artistic creations.

The fundamental principle of cubism entails the representation of different views of things, usually objects or figures together onto a single picture, this often results in paintings that appear fragmented and abstract.

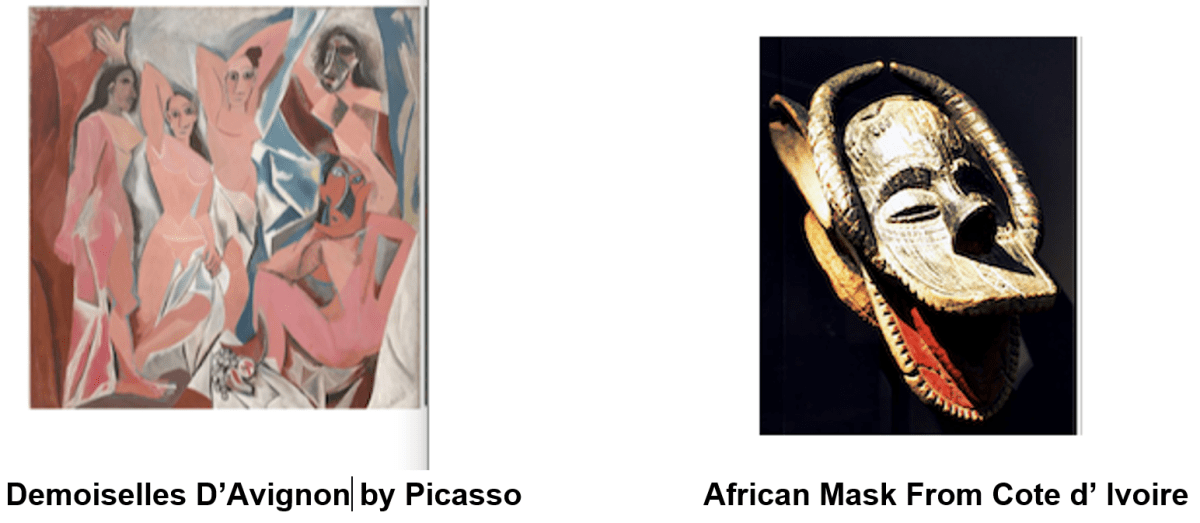

It became one of the most influential painting styles of the twentieth century and began with Picasso’s celebrated painting the Demoiselles D’Avignon.

In the painting, Africa’s influence on the creation of Picasso is evident, not only is this expressed in the way the human forms and the surrounding spaces are fractured and distorted but also in the faces of the two figures depicted at the right of the canvas, their features adopt the angular features of African masks.

In cubism, the artist aims to show different viewpoints at the same time on the same space by breaking the objects and figures into distinct planes or areas and by so doing also suggest their three-dimensional form. By the representation of the objects, the two-dimensional flatness of the canvas is emphasized.

This heralded a revolutionary break from the European artistic norm of forming the illusion of real space from a fixed viewpoint which since the Renaissance had dominated European artistic representation.

The name cubism itself seems to have arisen from a comment by art critic Louis Vauxcelles, who and when commenting on some of Georges Braque’s paintings in a 1908 Paris exhibition described them as reducing everything to “geometric outlines, to cubes.”

Cubism opened up limitless possibilities on the representation of visual reality through arts and marked the starting point for the deluge of European abstract arts which hitherto was not widely practised, including later abstract art styles like constructivism and neo-plasticism.

Italian painter and sculptor Amendo Modigliani is another good example of the influence of African style of arts on Europeans and modern arts in general. His works clearly reflected the angular elongations and geometric patterning of African arts.

Amendo Modigliani Sculpture Inspired by African Arts

FAUVISM

African artworks did not only give rise to the creation of cubism. Artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain took to the abstract and bright dissonant colour representations of some African artwork and thus birthed fauvism.

Other European artists that were influenced by these artistic styles are Albert Marquet, Louis Valtat, Georges Braque, Maurice de Vlaminck, Charles Camoin, Kees Van Dongen, Jean Puy, Othon Friesz, Henri Manguin, Raoul Dufy, Georges Rouault, and Jean Metzinger.

Artists like these favoured bold colours and forms over realism.

The artistic creation of these artists illustrated a high degree of simplification and abstraction of the subject and was characterized by a seemingly wild brush work and strident colours.

EXPRESSIONISM

In Germany artists like Emil Nolde were to a vast extent influenced by African arts, especially pertaining to masks and sculptures even though they may be that they did not fully understand the meaning of African works or the intent of the anonymous creators of African art.

Their style of art, influenced by African artworks, seeks to express the world exclusively from the perspective of the subject, the artwork is radically distorted for impact and to evoke moods or ideas.

This type of art is known as expressionism; expressionist artists favour the expression of emotional experience over physical reality.

Other artists that employ this style of art are Fritz Bleyl, Conrad Felixmüller, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Carl Hofer, Heinrich Campendonk, Käthe Kollwitz, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, August Macke, Franz Marc, Ludwig Meidner, Rolf Nesch, Otto Mueller, Gabriele Münter, Max Beckmann, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff to name a few.

Expressionist art started in Germany around 1905 at the time when African arts were beginning to gain acceptance.

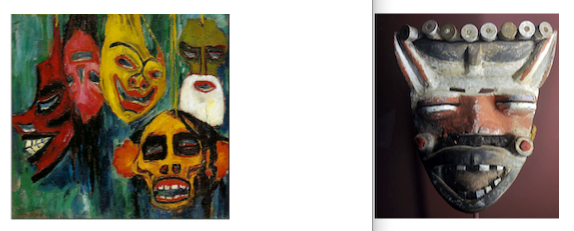

Natura Morta con Maschere III Mask From Dan Culture Africa

Expressionists basically do not create art based on realism. The artist seeks to depict the subjective emotions and responses within a person that are aroused by objects and events.

This expressionist style of art was started by the Germans grew and influenced the work of many other European and American artists like Marsden Hartley and Norris Embry. Even European sculptors like Ernst Barlach imbibed expressionism in his works[1].

A good example of Africa’s influence in Emil Nolde’s work is in the Natura Morta con Maschere III painting, the simplified geometric features, exaggerated expressions, and bold colours reflect the core artistic design of African masks.

African Influence on pop and jazz

John rockwell NYT 1981

Africa might seem too large, imposing and omnipresent a continent to be subject to something so ephemeral as a pop and jazz ''revival.'' But right now we seem to be in the midst of just such a revival, nonetheless. Everywhere Western musicians are turning to Africa, either for reaffirmation of a lost or dimly remembered ethnic heritage or for a more abstract kind of inspiration.

To speak of Africa as if it offered a single, consistent musical style is, of course, a ludicrous oversimplification. As John Storm Roberts points out in his informative book, ''Black Music of Two Worlds,'' Africa offers an area four times the size of the United States, with some 2,000 tribes speaking between 800 and 2,400 tongues, depending on whether some are counted as dialects or languages.

But Mr. Roberts does isolate some general characteristics of black African music - its functional use in society, its indivisibility in the African mind from dance and theater, the use of instruments to imitate the human voice, the primacy of rhythm and particularly the combination of several simulataneous cross-rhythms, and the calland-response structure. In addition, there is North African music, closely related to - but distinct from - other forms of Moslem music, which is closely related both to black African music and to the folk music of Southern Spain.

In America it has been blacks, naturally enough, who have pioneered the renewed interest in Africa. And of all American cities, it has been Chicago, the home of so vital an eruption of black jazz progressivism over the past 15 years, that has led the way - even if some of the key Chicago musicians have now moved to New York.

Of the Chicago groups, the Art Ensemble of Chicago is perhaps the best known. But there is also the aptly titled Ethnic Heritage Ensemble, which has a new disk out called ''Three Gentlemen from Chikago'' (Moers Music 01076, a German jazz label available in import stores or through Daybreak Express Records, 169 Seventh Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11215).

The ensemble consists of Kahil El'Zabar, who plays percussion and flutes; Edward Wilkerson, winds, and (Light) Henry Huff, saxophones. There are four pieces on this disk, two of them frenzied free-jazz eruptions and appealing as such. But there are also two slow, quiet numbers, and here the measured rhythmic impulse and instrumental coloration suggest a more overtly African influence.

George Lewis counts his experience in Chicago jazz circles as his formative years, even if he now lives in New York and directs the music program at the Kitchen, the downtown new-music center. Mr. Lewis's work today amounts to a fascinating instance of the way some black jazz musicians are being revealed to have followed a parallel course to some ''classical'' new-music composers. Mr. Lewis has been calling attention to that parallelism with a fine series of concerts this season at the Kitchen

His latest album, ''Chicago Slow Dance'' (Lovely Music VR 1101, available either at specialty shops or through Lovely Music, 463 West Street, New York, N.Y. 10014), enlists three longtime collaborators: Douglas Ewart and J.D. Parran, winds, and Richard Teitelbaum, a well-known electronic composer in his own right. To this, Mr. Lewis adds his skills as a trombonist and electronic composer.

The results, in their quiet, intense way, are enthralling. Mr. Lewis has long been concerned with adducing aspects of the black experience without being blatant or self-conscious about the process. ''Chicago Slow Dance'' has passages that suggest village drumming and mournful dialogues between voice-like brass instruments. But the music is far from being an ethnic pastiche.

African evocations are hardly the sole preserve of jazz musicians. Some black pop musicians are turning to the Continent, as well, not least Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye. Mr. Gaye has moved to London but also has a home in Senegal, and has stated that he hopes to spend time in Africa and to use more and more African influences to enliven Motown formulas.

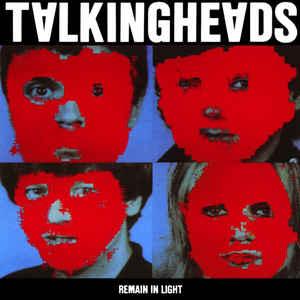

His latest album, ''In Our Lifetime'' (Tamla T8-374M1), is built up over a series of roiling instrumental tracks that recall a blend of George Clinton's densest funk and the supercharged intensity of the Talking Heads' album, ''Remain in Light.'' Add to that Mr. Gaye's winning ways as a singer, and you have what should be a massively popular blend of the accessible and the African - accessible even though one result of the African influence, as it was on the Talking Heads disk, has been a dissolution of the familiar structure of the Western pop song.

Finally, due out shortly, there is the long-awaited duo album of David Byrne and Brian Eno, ''My Life in the Bush of Ghosts'' (Warner Brothers SRK 6093). This is actually the missing link that should have preceeded ''Remain in Light'' and which helps explain the process by which Mr. Byrne, who is the head Talking Head, and Mr. Eno arrived at their African-inspired idiom. But a problem with copyright permission and a desire to improve the album delayed its release until after ''Remain in Light.''

Heads' fans can rest assured that the revised version is no dilution of the original, even if the one disputed track is indeed a loss. The reason for the copyright problems was that the album is a melange of densely textured instrumental tracks and ''found objects,'' many of which are tape recordings of voices taken from records or the radio.

The result is a brilliantly alluring record, an aural collage surging with an almost fevered energy. The musical idiom will be familiar to admirers of ''Remain in Light'' - full of cross-rhythms and polyphonic lines that knit together with an exciting precision. But here Mr. Eno has given his tendencies full rein toward a business of texture that still doesn't impede the music's momentum. After several years of mostly quiet ''ambient'' disks, this reverts to the world of his solo rock records but purged of rock's more tired conventions, enlivened by Mr. Byrne's own intense and bizarre imagination and inspired by the rhythms and vocal colors of both black and Arab Africa. It is a superb achievement and an intimation of the growing influence Africa is likely to have on Western musicians in years to come.

A version of this article appears in print on March 1, 1981, Section A, Page 2 of the National edition with the headline: THE AFRICAN INFLUENCE ON POP AND JAZZ MUSICIANS.

AFRICAN INFLUENCES ON JAZZ IN THE AMERICAS

Dharmadeva (2000)

Introduction

Though jazz originated in America, it was influenced by events and musicians from places in

Africa and Europe and, in particular, is steeped in a rich West African heritage, derived from the

slaves who brought with them their traditions. This is evident in both the United States of

America and Cuba.

In these countries slave owners took offence to the African slaves practising their musical rituals,

particularly drumming, but allowed them to engage in private gatherings of foot stomping and

hand clapping to substitute for drumming. Greater liberty was allowed at the Place Congo, a

square in New Orleans, where slaves were allowed to dance, sing, and play percussion, banjo,

fiddle and other instruments (Tirro: 6-7) in large circles, referred to as Ring Shouts. These

ceremonies were largely based on voodoo culture (Yurochko: 5). New Orleans is generally

thought to be the place where jazz began, branching out to the rest of the United States.

Throughout the 19th century, the music at the Place Congo (Congo Square) was a way for

African tribes to communicate, as in the talking drums of their homeland. With the resulting

interaction between African cultures and that of immigrants from other countries new forms of

music developed. This included the development of jazz at the end of the 19th century in New

Orleans. The music of the slave dances held in Congo Square, was over time transposed into

musical forms used by ensembles led by the likes of Buddy Bolden (1877-1931) and Joe ‘King’

Oliver (1885-1938) and his Creole Jazz Band of the 1920s (Gioia: 3-6). From there jazz went

across America and around the world, multiplying into many different and unorthodox forms

such as swing, bebop, free jazz, cool and jazz-rock fusion.

Emergence of Rag and Stomptime

At around the turn of the 19th century, black musicians such as W C Handy (1873-1958) and

Scott Joplin (1868-1917) - the ‘King of Ragtime’ - played a novel style of piano called ‘jig

piano’ or ragtime. This was an outgrowth of Negro dance music practices demanding great

rhythmic prowess. In part, it can be traced back to the shout and fiddle music of the Gullahs

(descendants of enslaved Africans) along the USA eastern seaboard who were among the last

group of blacks brought to the USA from West Africa (Tirro: 6-7). Joplin's style also

incorporated music of minstrel shows, camp meetings and itinerant songsters, weaving these

together into a melodic and rhythmic tapestry.

Ragtime is actually mostly rhythm. In piano rag music, the left hand provides the percussive

dance rhythm, while the right hand performs syncopated melodies, using motifs reminiscent of

fiddle and banjo tunes. Popular songs include Joplin's “Maple Leaf Rag” and "The Entertainer"

and pieces such as “Cuban Cake Walk” written by Tim Brymn (1881-1946). On becoming

popular, after being used as music for the ‘cakewalk’ dance, ragtime was hurtled away from

black communities into the mainstream and adopted by whites. It was also channelled into

American jazz. After Joplin's death greater improvisation was used and along with boogie

woogie, a simple blues based piano style, ragtime played an important part in the birth of jazz.

Negro worksongs (and children's songs) had also taken on their own peculiarities in the USA,

although derived from polyrhythmic patterns and the call and response styles of West Africa.

Their contribution to early jazz music was the New Orleans Stomp or Stomptime. This was

further developed by the Creoles, a significant sub-culture of blacks from Africa with French and

Spanish ancestry who had a knowledge of Western art music (Yurochko: 10). The most noted

musicians were Ferdinand ‘Jelly Roll’ Morton (1885-1942) with his Red Hot Peppers and Sidney

Bechet (1897-1959). Stomptime takes a rhythmic figure and uses it as a melodic line so as to

repeat it in an ostinato or riff pattern, leading to a polyphonic accentuation that produces strong

rhythmic momentum within the improvising polyphony (Tirro: 129-130).

Jelly Roll Morton brought an exotic style to jazz, which represents the transition from ragtime to

jazz. In the piece called "Black Bottom Stomp" instruments are used to percussively stress a

syncopated feel, and a call and response is used between the trumpet and rest of the ensemble.

Morton wrote music using polyphony, harmonised passages, solo improvisations, and unusual

instrumental combinations. From these early days of jazz, all the musical principles and

aesthetic values of African music are evident and continued to be influential: interlocking and

percussive rhythms, syncopation, density of sound or polyphony, ostinatos, improvised

variations, and call and response.

Polyrhythmic and polymetric patterns

Percussion plays a primary role within nearly all Sub-Saharan African music. This involves

cross rhythms and multiple rhythms and to a lesser degree simultaneous tempi embroidered with

one another (Megill & Demory: 2). Several drummers usually perform at the same time,

weaving a pattern of contrasting beats and accents and each player can be within their own ‘time

signature’ (Chernoff: 45). One percussion part may have a 6 beat pattern and another 8 beats,

dividing the overall time span of a 24 beat tune into different cycles. This is typical in BaMbuti

Pygmy tunes (Turino: 171). Interlocking rhythms are also used in mbira (thumb piano) pieces of

the Shona of Zimbabwe such as in "Nhemamusasa" (Turino: 166).

The steady pulse or metronomic sense (Chernoff: 49) of an African rhythm ensemble in which

additional rhythmic features are superimposed by various percussion instruments over the main

instrument's rhythmic pattern has its parallel in the jazz rhythm section (Tirro: 120). The

emphasis of where the pulse is placed is important in both forms. African music stresses the

‘off-beats’ so that in a 4/4 time signature the second and fourth beats would be emphasised

(Chernoff: 48). In the Ewe dances of Ghana the placement of stressed beats means that none of

the drums play a dominant free beat on the first and third beats (Chernoff: 48). Similarly, jazz

drummers often keep time by playing ‘boom CHICK boom CHICK’ (one TWO three FOUR)

instead of ‘BOOM chick BOOM chick’ (ONE two THREE four). This syncopation is part of

what makes a performance sound like jazz (Gridley: 361).

In African percussion, one instrument's down-beat becomes another's up-beat. This can

imperceptibly shift revealing a third or even a fourth counter-rhythm in African drumming

ensembles. All these different rhythms are used to express the rhythms of life. Jazz pianists,

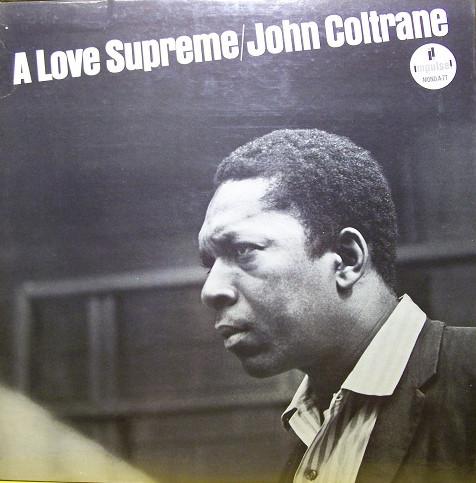

such as McCoy Tyner (born 1938) who played with saxophonist John Coltrane (1926-1967), also

use small jazz riffs creating polyrhythmic or polymetric effects so that the piano falls out of sync

with the rest of the rhythm section for a short period and then comes back in. Just as in African

music, so also in jazz, melodic instruments can be played in a percussive, rhythmic fashion

depending on the piece. For example, in Duke Ellington's big bands from the 1930s the lead

trumpeter Cootie Williams (1911-1985) used his melodic instrument in a percussive, off-beat

manner (Gridley).

Syncopation

Just as in the Ewe drum ensemble where the higher pitch cowbell contrasts against the drums, so

also in jazz, the single free-hanging ride cymbal can provide a repetitive, syncopated feel over

the dissonant chords of the piano and horns (Gridley: 78). Syncopation is the rhythmic effect

produced when the expected rhythmic pattern is deliberately upset by shifting regular accents to

weak beats. It can result in creating an effect of uneven rhythm and filling of spaces between

beats, and comes from complex African drumming.

In the 1910s, Negro conductors were leading syncopated orchestras (later called jazz orchestras).

These dance orchestras and brass bands were another precursor to jazz when they started playing

ragtime songs such as “Didn’t He Ramble” and syncopated marches on ceremonial occasions.

Count Basie (1904-1984) and Lester Young (1909-1959), two eminent names in big band music,

in their "Taxi War Dance" allow the trombone soloist, Dicky Wells (1907-1985), to play rapid

eighth-notes stressing the off-beats. The result is known as swing (Gridley: 35). Some of Count

Basie's other best known works are "One O'Clock Jump" and "Jumping at the Woodside".

Swing is a noted aspect in jazz music. The feel of the pulse is derived from African musical

performance and found in pieces such as the “Yarum Praise Song” (a slave song) which has a

steady underlying and unwavering pulse but with syncopations added (Tirro: 12).

Polyphony and big bands

James Reese Europe (1881-1919) laid the groundwork for the greatest big bands (Sutro: 34)

when he introduced certain innovations to the music such as writing up to as many as 10 or 12

different parts for each group of instruments in his band. This gave the music a full and

symphonic quality not heard in other bands of the time (Balliett: 97). Following James Reese

Europe was Fletcher Henderson (1898-1952) who really popularised the big band movement.

He included exciting music and unorthodox instrumentation by using alto and tenor saxophones,

clarinets, and tuba amidst a total of sixteen players. Chick Webb (1905-1939), a master

percussionist, elaborated with his fast and explosive style and reigned over the birth of such

Negro dances as the ‘lindy-hop’.

The jazz innovators of the time drew heavily on various African musical roots in their playing,

including complex rhythms, flexibility of pitch, polyphonic melodic structures, call and response

patterns, and collective improvisation. When one instrument (such as the trumpet) plays the

melody or a recognizable paraphrase or variation on it, and other instruments improvise around

that melody, this creates a polyphonic sound. Polyphony is also featured in jazz from New

Orleans.

It was Chick Webb who introduced his singing protégé Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996) to the

entertainment world. In the 1940s she used her voice to popularise bebop, a style of jazz that is

fast-moving, uses highly intricate melodies, complex rhythms and dissonant harmonies in which

the soloist dominants over the rest of the band. She brought to life the bebop style of jazz, with

emotional emphasis on the solo, which was an innovation without polyphonic emphasis.

However, polyphonic big bands continued to flourish, even though other styles of jazz such as

bebop developed, and they became more innovative. Stan Kenton (1911-1979) with his

reputation for offbeat compositions, provocative arrangements and fiery soloists augmented his

big bands with extra brass and percussion as a form of innovation.

It was Duke Ellington who came to represent the ideal big ‘swinging band’. His rambunctious

post-ragtime/boogie woogie style was avante-garde and his compositions began to transcend

style. His orchestra had many guises as seen in pieces like "Caravan", "Latin American Suite",

"Prelude to a Kiss" and his Africa-based works.

By the 1960s and 1970s when jazz had become electrified, swirls of sound were able to be

created and people like jazz trumpeter Miles Davis (1926-1991) did precisely that in albums such

as "Bitches Brew" which was essentially the invention of jazz-rock. This form involved

electronic instruments, sound flurries, anarchic textures, a freer jazz, but bound by an intense

rock-inspired rhythm section. African traditional influences also found their way into the kind of

jazz-rock fusion played by bands such as Weather Report.

Ostinato

In many African music traditions everyone has an active role and each person performs in some

manner. This is particularly so with respect to the BaMbuti Pygmy culture (Turino: 170-171).

To accomplish equal involvement of musicians use is made of constant repetitions of rhythmic

patterns or ostinatos. These may seem monotonous and unmoving, but provide a strong way to

communicate on one level and maintain stability. In jazz, short phrases, called riffs, are also

repeated in this way. These can provide ideas to the jazz soloist or create momentum for the

performers and drive within the ensemble. This was evident early on with the style played by the

boogie woogie pianists (Gridley: 44).

The professional or jali musicians of the Mande people of Mali and other places of West Africa

use a repeating kumbengo part or ostinato when playing the kora (a 21 stringed bridge harp over

a gourd sound box). Repeating bass figures and repeating rhythmic patterns on the metallic-

sounding karinyan are also common in Mali peasant songs such as "Hunter's Dance".

Traditional mbira pieces from Zimbabwe use ostinatos that descend progressively and then

repeat.

Similarly, in Count Basie's piece "One O'Clock Jump" a simple riff pattern, played by the

saxophones, is incorporated to give it a swing feeling (Gridley). Likewise, Archie Shepp (born

1937), a ‘free jazz’ saxophonist, in his piece "Le Matin Des Noire" ("The Morning of the

Blacks"), by using African derived patterns, communicates the condition of blacks in American

society in his ‘musical commentaries’ through use of ostinatos in his solos which have a

syncopated feel and utilisation of various buzzings in his tone.

Improvisation

The use of buzzings, overblown notes, shrieks and cries are actually techniques used in

improvisation. Usually improvisation involves creating personalised melodies and rhythms

within the context of the music being performed, but can also extend further than that by use of a

wide range of ornamentations. Improvisation is a key element in jazz music and derives from

Sub-Saharan Africa where it is used by many tribal groups and drum ensembles. In the

Mandinka drum ensemble, the senior player has leeway to improvise more than the others, but

all members are allowed to slightly vary their parts as they play (Gridley: 40). The kora player

will use an instrumental interlude with vocable singing, called the birimintingo, as their form of

improvisation (Turino: 173-175).

In jazz, improvisational techniques have simply matured and adopted their own style, but the

basic element, of the soloist utilising percussive or melodic qualities, still connects to African

music as do the various roughings, buzzes, or ringing sounds that can be incorporated into the

soloist's idea. Drummers in the Ewe drum ensembles of Ghana may use bottletops around their

drums to create a buzzing sound and the mbira players of Zimbabwe will do the same with their

gourds covering the mbira. Jazz drummers may instead insert rivets into a cymbal so that the

vibrations create a sizzling sound (Gridley: 44). Similarly, many jazz instrumentalists create

unique sounds to improvise on tone quality and not just melodic or rhythmic ideas. This

'dirtying' of the sound is an aesthetic feature found in much African music, particularly by adding

rattling and buzzing to tonal sounds.

Louis Armstrong (1900-1971), the famous jazz trumpeter's style was to leave the melody during

his flights of improvisation thereby creating new melodies. This marked the change from group

improvisation of the early brass bands to featured artist improvisations. His rhythmic style also

saw the transition to free-flowing swing from the rigidity of ragtime. But for Charlie Parker

(1920-1955), the bebop jazz saxophonist, swing had become repetitive. Parker's melodic,

rhythmic, and harmonic sense and longer, complicated improvisations were extremely fluid and

immediately engaging. This was revolutionary for the 1940's.

The great saxophonist, John Coltrane (1926-1967) went to the extreme of utilising unique sounds

by producing tones from raspings and buzzings, smooth to guttural and full to shrieking. This is

most evident in his major long works such as "Kulu Se Mama" (incorporating many African

rhythms) and "Ascension". The rousing free shouts and soul-wrenching jazz hollers of Charles

Mingus (1922-1979) also reach with the same emotional punch while he plays bass.

In improvisation, notes ‘in-between’ notes which derive from a variety of scales can also be

employed. This enables a musician to maintain a mood by playing around one scale or mode. It

is this modal approach which also forms the fundamentals of African (and European) jazz music.

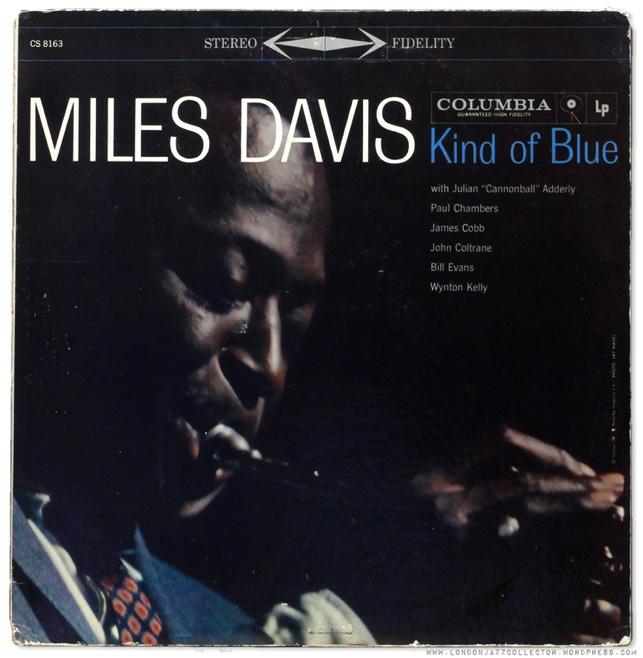

Miles Davis playing his trumpet made prolific albums such as "Milestones" and "Kind of Blue"

using the modal style.

Call-and-response

The call and response of the African tradition has carried through into urban jazz and is found in

early pieces such as "West End Blues" by Joe ‘King’ Oliver (1885-1938). Jazz makes use of call

and response by employing an antiphonal relationship between two solo instruments or between

solo and ensemble. In many forms it involves the lead singer or instrument performing a short

phrase or call followed by a response from a congregation or group of instruments.

In Africa, the BaMbuti Pygmies often use a pattern of || C1/R C1/R C2/R C2/R ||. Regardless

of how simple or complex the pattern, the underlying idea of call and response is that a cyclical

rhythm is formed by constant repetitions. This is also employed by the Ewe drum ensembles of

Ghana (Turino: 178) between the middle size drums of sogo and kidi.

Vocally, Louis Armstrong employed the technique of an instrument providing the primary call

followed by Louis' vocal scat response which he embellishes and improvises as the interaction

between them progresses. For example, he would use scats in his call-and-response dialogue

with the guitarist, echoing or mimicking the scat line.

Call and response between the brass ensemble and saxophones within a big band was also very

common. For example, in Duke Ellington's "Cottontail" there is a repetitive interaction between

both sections and their statements become shorter and more intense in the closing (Gridley).

Cuba

The African influence on jazz did not just extend to the USA. Cuba cannot be overlooked,

where the persistence of the slave trade until its late abolition in 1886 is a reason for the density

and variety of its African cultural elements. By the end of the 19th century some 14 distinct

African ‘nations’ had preserved their identity in Cuba through mutual aid support societies

known as cabildos thereby providing an opportunity for the preservation of their culture, on an

island where the indigenous population had been virtually exterminated by the Spanish long ago.

The term Kongo encompasses the diversity of peoples brought to Cuba from Africa during the

years of slavery. Their secular form of music during the 19th century incorporated the use of

yuka drums played in groups of three. These were made by hollowing out tree trunk sections of

various sizes and nailing on cowhides. The largest master drum is the caja held between the legs

of the drummer. The caja player often wears a pair of wrist rattles. Another musician plays a

pair of sticks against the body of the caja, usually on a piece of tin nailed to the base of the drum.

This stick is called the guagua or cajita, and may be played on a separate instrument. The

middle drum is the mula, and the smallest is the cachimbo. A guataca (a hoe blade played with a

large nail or spike) is used as a timekeeper. Yuka dancing featured the vacunao, a pelvic

movement found in Kongo derived dance styles.

In Cuba, the European instruments like flute, violin, trumpet and guitar met with African congas,

bongos and claves and Spanish rhythms fused with that of Africa to create new hybrids, while

sharing the same West African, primarily Yoruba, roots. New Orleans was the main port of

entry for Cuban rhythms and their impact on American jazz. This influence is seen from as early

as W C Handy's "St. Louis Blues" as performed by Louis Armstrong and the "Jungle Music" that

launched Duke Ellington at the Cotton Club. It is seen in the 1940s and 1950s when Cuban born

Frank Grillo (1908-1984), known as "Machito", and trumpet player Mario Bauza (1911-1993)

formed a big band called ‘Machito's Afro-Cubans’ for which Bauza wrote "Tanga" in 1943, the

quintessential Afro-Cuban jazz piece.

Machito and Bauza also helped introduce Dizzy Gillespie (1917-1993) and other jazz giants to

African strains in Cuban music. Gillespie is largely credited with the invention of Afro-Cuban

jazz while collaborating with Chano Pozo (1915-1948), the great congero percussionist, in the

1940s. "Dizzy Gillespie Live at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium" contains great examples of

seminal Afro-Cuban jazz with compositions like "Manteca", "Tin Tin Deo", "Cubano Be" and

"Cubano Bop". As leader of the 1940s bebop movement, Afro-Cuban jazz was often referred to

a Cubop.

In the 1950s composer and trumpeter Arturo ‘Chico’ O'Farrill (1921-2001) of Havana composed

the "Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite", which was the first extended composition written in that idiom. He

used the big band to explore Afro-Cuban rhythms in large-scale extended compositional works.

He also composed symphonic works for jazz.

Son and Afro-Latin jazz

In Cuba songs (and dance) in a style called son, (literally ‘sound’) is one of the most popular and

influential musical forms. Son originated in the second half of the 19th century in the rural areas

but was further developed by the poor working class of Cuba in the 1920s. Larger ensembles

were also formed that included a marimbula (derived from the African thumb piano), later

replaced by the double bass, and percussion such as the giro or gourd, bongos, maracas and

claves. Now all manner of brass and wind instruments are included.

Son combines African percussion and rhythmic patterns (probably of Bantu origin who came

from the Congo) with the Spanish lyrical style of décima (stanzas of 10 octosyllabic lines in the

form abbaa/aabba in which improvisation plays a major role). The basic rhythmic pattern of

the son is the clave (literally ‘key’) played on 2 hand-held cylindrical hard wooden sticks, also

called claves (approximately 12-18 cm long) which are struck together producing a high-pitched,

resonant sound.

The clave rhythm is a five-note, two-bar rhythm pattern which gives son a type of propulsive

swing and a strongly syncopated style. Typically, the claves player sets the clave beat played in

common 4/4 time. In the first measure, the musician strikes the claves on the first downbeat, on

the second upbeat, and on the fourth downbeat (3 strikes). In the second measure, the emphasis

is placed on the second and third downbeats (2 strikes). This off-balance beat accenting either

one and three, or two and four, in the four beat measure can also be reversed as a 2-3 clave.

The son had a direct impact on American music coinciding with the dance crazes of the rumba in

the 1930s in which traditionally dancers come out one at a time, or in pairs, to ‘strut their stuff’

in front of their peers and rivals, the mambo (up tempo versions of the son) in the 1940s, and the

chachachá in the 1950s prior to the Cuban Revolution (Waxer). The guaracha, an early Cuban

dance genre, also uses the son style as does the more general party salsa music of the 1970s.

These dances resulted in the appearance of large Latin music bands combining trumpet,

trombone, and saxophone sections of American swing era big bands with Afro-Cuban rhythms

and repertoire and giving rise to Afro-Latin jazz. This is a genre of jazz that typically employs

rhythms that have direct or indirect African influences. The two main categories of Afro-Latin

jazz are: the Afro-Cuban style based on clave, often with a rhythm section employing ostinato

patterns; and Afro-Brazilian jazz noticeably the bossa nova and samba styles.

Rumba and Afro-Cuban jazz

In Cuban music, rumba is a genre involving dance, percussion, and song. The rumba style is

most influenced by African rhythms. It derives from the Congo Basin in Africa. The modern

rumba may have grown out of older rhythms (Walser: 208) played on the yuka drums made from

hollowed out tree trunks. Some forms use the guagua stick and wrist rattles. The main stylistic

difference is that the lead or co-ordinating rumba drum is always the high-pitched quinto, the

two deeper tone support drums having taken over the ostinato patterns. This reversal is probably

an European influence on rumba drumming. In addition to brass and woodwind, the cowbell and

shékere (a large gourd covered with a beadladen net) may be used.

As well as the jam session or descarga (a folkloric rumba), there are 3 main rhythms in rumba,

each with its own dance: yambú, columbia and guaguancó. These rhythms are marked by

distinctly African traits such as polymeter, offbeat phrasing of musical accents, and reliance on

a metronomic sense (Waterman: 211214). Singing is done by a chorus (usually large to give it

energy) and a succession of lead singers, who compete to lead the songs and uphold their honour

as rumberos. Use is made of verbal improvisation skills and call and response to build

excitement and generate participation by dancers and the chorus.

While the three varieties differ in instrumentation, vocal style and choreography, they all mimic

each other to some degree. The yambú is performed in slow tempo and is often considered an old

people's dance. In yambú, there is no pelvic movement. The columbia (actually in 6/8 time)

began in the rural areas and involves a male solo dance that features many complex acrobatics

and imitations of ball players, bicyclists, cane-cutters and other figures. The dancer may also

reproduce steps of the Abakwa religious tradition (from the Cross River region in Nigeria, which

the Cubans call Carabali). The guaguancó is the modern, urban form of rumba popular in

Havana. Its dances often involve stylised sexual pursuits.

While Afro-Cuban jazz originated in the 1940s, a more recent development in the 1970s is the

batá-rumba for a big band setting. Chucho Valdes (born 1941), the great Cuban pianist,

introduced the bata and other African instruments of theYoruba into Cuban popular music via

oral traditions learnt from older musicians. The rumba/jazz fusion synthesis of Irakere (meaning

‘jungle’ in Yoruba) was the result, forging a funky, modern rock style while focusing on African

elements of Cuban culture, especially rhythmic contributions. Irakere helped develop the careers

of such internationally recognised musicians as saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera (born 1948) and

trumpeter Arturo Sandoval (born 1949) of Cuba.

Conclusion

Even though the direct African influence on jazz in the USA was already several generations

removed, that influence did exist as an evolving phenomenon ever since the forced

transmigration of people from Africa as slaves. This 'black expressiveness' and undercurrent can

be seen in musical characteristics such as improvised and vital emotionalism, spontaneity,

swinging beats, moving riffs, and swirling complex rhythms.

The development of Afro-Latin jazz and in particular the form of Afro-Cuban jazz further

demonstrates how African influences extended to Cuba and had a more direct impact on its

music. Even this separate development found its way into the USA as the 'Latin' influence on

jazz. This is yet another demonstration of the variety and colourfulness of jazz and its constant

evolution. It also speaks highly of the resilient and dynamic cultures of Africa, despite their past

oppression.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balliett, Whitney. 1986, American Musicians: 56 Portraits in Jazz, Oxford University Press.

Chernoff, John Miller.1979, African Rhythm and African Sensibilities, University of Chicago

Press.

Gioia, Ted. 1997, The History of Jazz, Oxford University Press.

Gridley, Mark C. 1994, Jazz Styles - History and Analysis, 5th ed. Prentice Hall.

Megill, Donald D. & Demory, Richard S. 1996, Introduction to Jazz History, 4th ed. Prentice

Hall.

Sutro, D. 1998, Jazz for Dummies, IDG Books Worldwide.

Tirro, Frank. 1993, Jazz: A History, 2nd ed. WW Norton & Co.

Turino, T. 1997, "The Music of Sub-Saharan Africa" in Excursions in World Music, 2nd ed.

Nettl, B. ed., Prentice Hall, pp 161-190.

Walser, Robert. 1995, "Rhythm, Rhyme, and Rhetoric in the Music of Public Enemy" in

Ethnomusicology, vol. 39, no. 2 (spring/summer), University of Illinois, pp193-217.

Waterman, Richard Allen. 1967, “African Influence on the Music of the Americas” in

Acculturation in the Americas: Proceedings and Selected Papers of the XXIX International

Congress of Americanists, Sol Tax, ed., Cooper Square Publishers, pp 207217.

Waxer, Lise. 1994, "Of Mambo Kings and Songs of Love; Dance Music in Havana and New

York From the 1930s to the 1950s" in Latin American Music Review, vol. 15, no.2 (fall/winter),

University of Texas Press.

Yurochko, Bob. 1993, A Short History of Jazz, Nelson-Hall Publishers.

Other books of interest

Ashenafi, Kebede. 1995, Roots of Black Music, African World Press.

de Lerma, Dominique-Rene. 1970, Black Music in Our Culture, Kent State University Press.

Dennison, Sam. 1982, Scandalize My Name: Black Imagery in American Popular Music,

Garland Publishing.

Feather, Leonard. 1965, The Book of Jazz from Then to Now, Bonanza.

Locke, Alain. 1936, The Negro and His Music, Associates Negro Folk Education.

Lyttelton, Humphrey. 1982, The Best of Jazz II: Enter the Giants 1931-1944, Taplinger

Publishing Co.

Morris, Berenice Robinson. 1974, American Popular Music of the 20th Century, Franklin Watts.

Roach, Hildred. 1976, Black American Music: Past and Present, Crescendo Publishing Co.

Southern, Eileen. 1971, The Music of Black Americans, WW Norton & Co.

18