This is a Humanities class, I did not see the option below. Book: Boundless Art History by Lumen Corporation Chapters: 19-20-21 Choose a topic from Module 1, Which covers Non-Western Art that you

Japan After 1333 CE

Top of Form

Search for:

Bottom of Form

The Modern Period

Japanese Art in the Meiji Period

The art of the Meiji period (1868–1912) was marked by a division between European and traditional Japanese styles.

Learning Objectives

Explain how the conflict caused by Europeanization and modernization during the Meiji Period was reflected in the artwork of the time

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Meiji period (September 1868 through July 1912) represents the first half of the Empire of Japan, during which Japanese society moved from being an isolated feudalism to its modern form.

During this period, western style painting (Yōga) was officially promoted by the government, which sent promising young artists abroad for studies and hired foreign artists to establish an art curriculum at Japanese schools.

After an initial burst of western style art, there was a revival of appreciation for traditional Japanese styles (Nihonga) led by art critic Okakura Kakuzo and educator Ernest Fenollosa.

In the 1880s, western style art was banned from official exhibitions and was severely criticized by critics. Supported by Okakura and Fenollosa, the Nihonga style evolved with influences from the European pre-Raphaelite movement and European romanticism.

In 1907, with the establishment of the Bunten exhibitions, both competing groups—Yōga and Nihonga—found mutual recognition and co-existence and even began the process toward mutual synthesis.

Key Terms

pre-Raphaelite movement: An art movement founded by a group of English painters, poets, and critics with the intention of reforming art by rejecting what they considered to be the mechanistic approach first adopted by the Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo.

feudalism: A social system based on personal ownership of resources, personal fealty of a lord by a subject, and a hierarchical social structure reinforced by religion.

Romanticism: An artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe toward the end of the 18th century and in most areas was at its peak from 1800 to 1840; partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, it was also a revolt against aristocratic social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and a reaction against the scientific rationalization of nature.

Overview: The Meiji Period

The Meiji period (明 Meiji-jidai) was an era in Japanese history that extended from September 1868 through July 1912. This period represents the first half of Japan’s time as an imperial power. Fundamental changes affected Japan’s social structure, internal politics, economy, military, and foreign relations. Japanese society moved from being an isolated feudalism to its modern form. In art, this period was marked by the division into competing European and traditional indigenous styles. In 1907, with the establishment of the Bunten exhibition under the aegis of the Ministry of Education, both competing groups found mutual recognition and co-existence and even began the process towards mutual synthesis.

The Yōga Style

During the Meiji period, Japan underwent a tremendous political and social change in the course of the Europeanization and modernization campaign organized by the Meiji government. Western style painting (Yōga) was officially promoted by the government, which sent promising young artists abroad for studies. The Yōga style painters formed the Meiji Bijutsukai (Meiji Fine Arts Society) to hold its own exhibitions and to promote a renewed interest in western art. Foreign artists were also hired to come to Japan to establish an art curriculum in Japanese schools. The Yōga style encompassed oil painting, watercolors, pastels, ink sketches, lithography, etching, and other techniques developed in western culture.

Yōga style painting of the Meiji period by Kuroda Seiki (1893): Yōga, in its broadest sense, encompasses oil painting, watercolors, pastels, ink sketches, lithography, etching, and other techniques developed in western culture. However, in a more limited sense, Yōga is sometimes used specifically to refer to oil painting.

The Nihonga Style

After an initial burst of western style art, however, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction. Led by art critic Okakura Kakuzo and educator Ernest Fenollosa, there was a revival of appreciation for traditional Japanese styles (Nihonga). In the 1880s, western style art was banned from official exhibitions and was severely criticized by critics. Supported by Okakura and Fenollosa, the Nihonga style evolved with influences from the European pre-Raphaelite movement and European romanticism. Paintings of this style were made in accordance with traditional Japanese artistic conventions, techniques, and materials based on traditions over a thousand years old.

Nihonga style painting: Black Cat by Kuroki Neko, 1910): Nihonga style paintings were made in accordance with traditional Japanese artistic conventions, techniques, and materials. While based on traditions over a thousand years old, the term was coined in the Meiji period of the Imperial Japan to distinguish such works from Western style paintings, or Yōga.

Japanese Art in the Showa Period

During the Shōwa period, Japan shifted toward totalitarianism until its defeat in World War II, when it led an economic and cultural recovery.

Learning Objectives

Create a timeline describing the upheaval, occupation, democratic reforms, and economic boom of the pre- and post-war Shōwa period

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Shōwa period in Japanese history corresponds to the reign of the Shōwa Emperor, Hirohito, from December 25, 1926 through January 7, 1989.

Japanese painting in the pre-war Shōwa period was largely dominated by the work of Yasui Sōtarō (1888–1955) and Umehara Ryūzaburō (1888–1986).

During World War II, government controls and censorship meant that only patriotic themes could be expressed, and many artists were recruited into the government propaganda effort.

After the end of World War II in 1945, many artists began working in art forms derived from the international scene, moving away from local artistic developments into the mainstream of world art.

Key Terms

Treaty of San Francisco: A treaty between Japan and part of the Allied Powers, officially signed by 48 nations on September 8, 1951 and coming into force on April 28, 1952; representing the official conclusion of World War II, it ended Japan’s position as an imperial power and allocated compensation to Allied civilians and former prisoners of war who had suffered Japanese war crimes.

Surrealism: An artistic movement and an aesthetic philosophy, pre-dating abstract expressionism, that aims for the liberation of the mind by emphasizing the critical and imaginative powers of the subconscious.

fascism: A political regime having totalitarian aspirations, ideologically based on a relationship between business and the centralized government, business-and-government control of the market place, repression of criticism or opposition, a leader cult, and exalting the state and/or religion above individual rights.

![This is a Humanities class, I did not see the option below. Book: Boundless Art History by Lumen Corporation Chapters: 19-20-21 Choose a topic from Module 1, Which covers Non-Western Art that you 4]()

Overview: The Shōwa Period

The Shōwa period in Japanese history corresponds to the reign of the Shōwa Emperor, Hirohito (裕), from December 25, 1926 through January 7, 1989. The Shōwa period was longer than the reign of any previous Japanese emperor. During the pre-1945 period, Japan moved toward political totalitarianism, ultra-nationalism, and fascism, culminating in Japan’s invasion of China in 1937. This was part of an overall global period of social upheavals and conflicts such as the Great Depression and the Second World War.

Defeat in the Second World War brought radical change to Japan. For the first and only time in its history, Japan was occupied by foreign powers. This occupation by the United States on behalf of the Allied Forces (which included the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and China) lasted seven years. Allied occupation brought forth sweeping democratic reforms, leading to the end of the emperor’s status as a living god and the transformation of Japan into a democracy with a constitutional monarch. In 1952, with the Treaty of San Francisco, Japan became a sovereign nation once more and underwent an economic revitalization. In these ways, the pre-1945 and post-war periods regard completely different states: the pre-1945 Shōwa period (1926–1945) concerns the Empire of Japan, while the post-1945 Shōwa period (1945–1989) was a part of the State of Japan.

Art in the Pre-War Shōwa Period

Japanese painting in the pre-war Shōwa period was largely dominated by Yasui Sōtarō (1888–1955) and Umehara Ryūzaburō (1888–1986). These artists introduced the concepts of pure art and abstract painting to the Nihonga tradition (a style based on traditional Japanese art forms) and thus created a more interpretative version of that genre. Yasui Sōtarō was strongly influenced by the realistic styles of the French artists Jean-François Millet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Paul Cézanne; he incorporated clear outlines and vibrant colors in his portraits and landscapes, combining western realism with the softer touches of traditional Nihonga techniques. This trend was further developed by Leonard Foujita (also known as Fujita Tsuguharu) and the Nika Society to encompass surrealism. To promote these trends, the Independent Art Association was formed in 1930.

Portrait of Chin-Jung (1934) by Yasui Sōtarō. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.: Yasui Sōtarō was strongly influenced by the the realistic styles of the French artists Jean-François Millet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and, in particular, Paul Cézanne. He incorporated clear outlines and vibrant colors in his portraits and landscapes, combining western realism with the softer touches of traditional Nihonga techniques.

By the early 20th century, European art forms were also introduced into Japanese architecture. Their marriage with traditional Japanese styles of architecture produced notable buildings like the Tokyo Train Station and the National Diet Building that still exist today.

Tokyo Station: Tokyo Station opened on December 20, 1914, and was heavily influenced by European architectural styles.

Art in the Post-War Shōwa Period

During World War II, government controls and censorship meant that only patriotic themes could be expressed, and many artists were recruited into the government propaganda effort. After the end of World War II in 1945, many artists began working in art forms derived from the international scene, moving away from local artistic developments into the mainstream of world art. Traditional Japanese conceptions endured, however, particularly in the use of modular space in architecture, certain spacing intervals in music and dance, a propensity for certain color combinations, and characteristic literary forms.

Japanese Art after World War II

After World War II, Japanese artists became preoccupied with the mechanisms of urban life and moved from abstraction to anime-influenced art.

Learning Objectives

Describe the flourishing of painting, calligraphy, and printmaking after World War II

Key Takeaways

Key Points

In the post-World War II period of Japanese history, the government-sponsored Japan Art Academy (Nihon Geijutsuin) was formed in 1947, containing both nihonga and yōga divisions.

After World War II, painters, calligraphers, and printmakers flourished in the big cities, particularly Tokyo, and became preoccupied with the mechanisms of urban life, reflected in the flickering lights, neon colors, and frenetic pace of their abstractions.

After the abstractions of the 1960s, the 1970s saw a return to realism strongly flavored by the “op” and “pop” art movements, embodied in the 1980s in the explosive works of Ushio Shinohara.

By the late 1970s, the search for Japanese qualities and a national style caused many artists to reevaluate their artistic ideology and turn away from what some felt were the empty formulas of the West. Contemporary paintings began to make conscious use of traditional Japanese art.

![This is a Humanities class, I did not see the option below. Book: Boundless Art History by Lumen Corporation Chapters: 19-20-21 Choose a topic from Module 1, Which covers Non-Western Art that you 6]()

There are also a number of contemporary painters in Japan whose work is largely inspired by anime subcultures and other aspects of popular and youth culture, such as the work of Takashi Murakami.

Key Terms

Rinpa school: One of the major historical schools of Japanese painting, created in 17th-century Kyoto by Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) and Tawaraya Sōtatsu (d. c. 1643).

Nitten: The annual Japan Art Academy Awards and the premier art exhibition in Japan.

Japanese Art After World War II

Welcoming the new post-World War II period of Japanese history, the government-sponsored Japan Art Academy (Nihon Geijutsuin) was formed in 1947. The Academy contained both nihonga (traditional Japanese) and yōga (European-influenced) divisions. Government sponsorship of art exhibitions had ended, but they were replaced by private exhibitions, such as the Nitten, on an even larger scale. Although the Nitten was initially the exhibition of the Japan Art Academy, since 1958 it has been run by a separate private corporation. Participation in the Nitten became almost a prerequisite for nomination to the Japan Art Academy.

The arts of the Edo and prewar periods (1603–1945) had been supported by merchants and urban people, but they were not as popular as the arts of the postwar period. After World War II, painters, calligraphers, and printmakers flourished in the big cities—particularly Tokyo—and became preoccupied with the mechanisms of urban life, reflected in the flickering lights, neon colors, and frenetic pace of their abstractions. Styles of the New York-Paris art world were fervently embraced. After the abstractions of the 1960s, the 1970s saw a return to realism strongly flavored by the “op” and “pop” art movements, embodied in the 1980s in the explosive works of Ushio Shinohara.

Ushio Shinohara

Japanese painter Ushio Shinohara paint boxing at SUNY New Paltz, 2012.

Many such outstanding avant-garde artists worked both in Japan and abroad, winning international prizes. Some of these artists felt more identified with the international school of art rather than anything specifically Japanese. By the late 1970s, the search for Japanese qualities and a national style caused many artists to reevaluate their artistic ideology and turn away from what some felt were the empty formulas of the West. Contemporary paintings within the modern idiom began to make conscious use of traditional Japanese art forms, devices, and ideologies.

Mono-ha

Mono-ha is the name given to group of 20th century Japanese artists. The mono-ha artists explored the encounter between natural and industrial materials, such as stone, steel plates, glass, light bulbs, cotton, sponge, paper, wood, wire, rope, leather, oil, and water, arranging them in mostly unaltered, ephemeral states. The works focus as much on the interdependency of these various elements and the surrounding space as on the materials themselves. A number of mono-ha artists turned to painting to recapture traditional nuances in spatial arrangements, color harmonies, and lyricism.

Nihonga, Rinpa, and Kano Influence

Japanese-style, or nihonga painting continued in a pre-war fashion, updating traditional expressions while retaining their intrinsic character. Some artists within this style still painted on silk or paper with traditional colors and ink, while others used new materials, such as acrylics.

Many other older schools of art were still practiced, most notably those of the Edo and pre-war periods. For example, the decorative naturalism of the Rinpa school, characterized by brilliant, pure colors and bleeding washes, was reflected in the work of many artists of the postwar period in the 1980s art of Hikosaka Naoyoshi. The realism of Maruyama Ōkyo’s School and the calligraphic and spontaneous Japanese style of the gentlemen-scholars were both widely practiced in the 1980s. At times, all of these schools (along with older ones, such as the Kano School ink traditions) were drawn on by contemporary artists in the Japanese style and in the modern idiom. Many Japanese-style painters were honored with awards and prizes as a result of renewed popular demand for Japanese-style art beginning in the 1970s. More and more, the international modern painters also drew on the Japanese schools as they turned away from Western styles in the 1980s. The tendency had been to synthesize East and West, and some artists such as Shinoda Toko had already leapt the gap between the two. Shinoda’s bold sumi ink abstractions were inspired by traditional calligraphy but were realized as lyrical expressions of modern abstraction.

Anime Influence

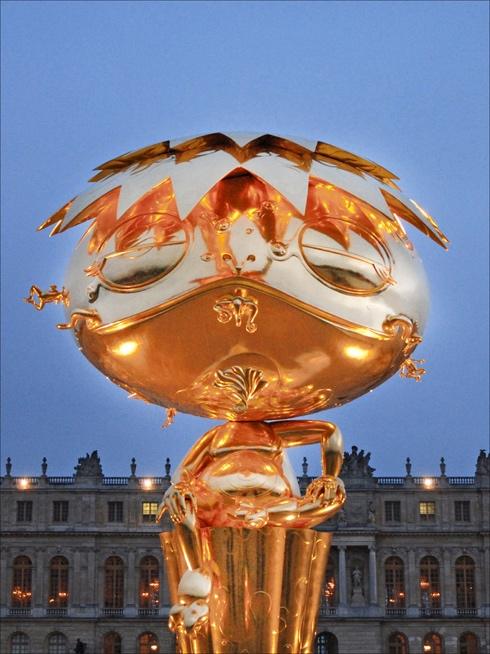

There are also a number of contemporary painters in Japan whose work is largely inspired by anime subcultures and other aspects of popular and youth culture. Takashi Murakami is perhaps among the most famous and popular of these, along with the other artists in his Kaikai Kiki studio collective. His work centers on expressing issues and concerns of post-war Japanese society through seemingly innocuous forms. He draws heavily from anime and related styles but produces paintings and sculptures in media more traditionally associated with fine arts, intentionally blurring the lines between commercial, popular, and fine arts.

Sculpture by Japanese artist Takashi Murakami at Versailles, France. 2007–2010 bronze and gold leaf.: Takashi Murakami is perhaps the most famous and popular contemporary Japanese artist whose work is largely inspired by anime subcultures and other aspects of popular and youth culture.

Hayao Miyazaki's movies: why are they so special?

Miyazaki has captured the hearts of film-goers worldwide and won the best animated film Oscar in 2003 for the spooky and surreal Spirited Away

The stories he animates may be full of whimsy, but the Japanese genius is a hard taskmaster who sets exacting standards for himself, his peers and studio staff

A still from Spirited Away (2001). Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki won the best animated film Oscar in 2003 for the spooky and surreal film. Photo: Studio Ghibli

After Walt Disney, Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki is the best-known animator in the world. Since making his big- screen debut with The Castle of Cagliostro in 1979, films such as 1988’s

My Neighbour Totoro

– a gentle story about friendly woodland spirits that still stands as his signature piece – have frequently topped the Japanese charts, broken box-office records, and won awards in Japan.

Acclaim from animators in the United States led to a breakthrough in the West around the start of the new millennium, and Miyazaki’s films began to gain international appeal after the US release of the ecologically aware Princess Mononoke in 1999. Miyazaki won the best animated film Oscar in 2003 for the spooky and surreal Spirited Away, which also shared the prestigious Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 2002.

Miyazaki, who was born in Tokyo in 1941, began his career working in television at Toei Animation, but most of his films have been produced by Studio Ghibli, which he founded with his friends and colleagues Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki in 1985. Ghibli halted production in 2014 when Miyazaki announced his retirement, but reopened in 2017 when he decided to go back to work on How Do You Live?, which is currently some three years away from completion.

Miyazaki will receive his first North American museum retrospective when the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is inaugurated in April 2021.

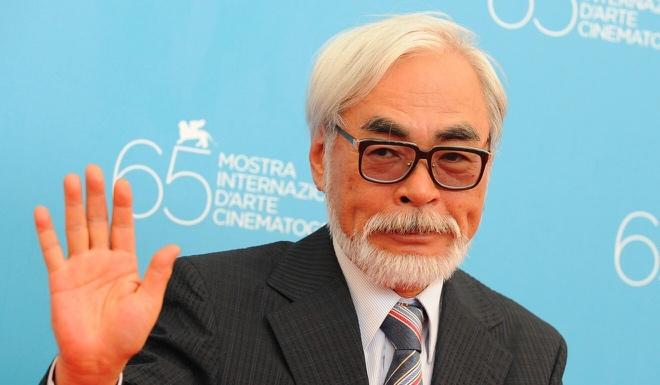

Miyazaki waves to photographers during the premiere for his movie Ponyo on the Cliff during the 65th Venice International Film Festival in Venice, Italy. Photo: AFP

In spite of his avuncular appearance, Miyazaki is known as a hard and sometimes ruthless taskmaster who sets exacting standards for himself, his peers, and his employees.

He is a workaholic who sometimes falls asleep at his desk, and admits he has often neglected his health – and his family – in the pursuit of his art.

What’s special about his work? Miyazaki is a genius, and his films succeed on many levels – technical, emotional, intellectual, philosophical, artistic, and political. They are adored by children and serious film critics alike.

Animated films are often aimed at the young, and with the exception of his anti-war fable

, all of Miyazaki’s films are aimed at children or young teenagers. But he makes his films resonate with adults as well as children by keeping the emotions authentic.

A still from Spirited Away (2001). The film shared the prestigious Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 2002.

Miyazaki does not underestimate the intelligence of children, or their powers of understanding. Characters in films like Castle in the Sky are not protected from the horrors of life – they experience loss and sadness as well as joy, despair as well as hope, in a way that is relatable for both children and adults.

Similarly, Miyazaki does not shy away from addressing adult themes like militarism and environmentalism. He believes that children should be exposed to such ideas and will understand them if they are presented correctly.

Miyazaki draws heavily on Japanese landscapes and culture, although the humanism of his films means they can be appreciated by international viewers. He loves the country’s woodlands (which he says contain more bugs than those of Europe), and he and his team made field trips to forests to research films like My Neighbour Totoro.

A still from My Neighbor Totoro, a 1988 Japanese animated fantasy film written and directed by Miyazaki. Photo: Studio Ghibli

The storyline of Spirited Away is a very detailed examination of the animistic nature gods of Japan, although the film can be enjoyed without any knowledge of them.

In contrast, Castle in the Sky, which features a mining town, was inspired by a trip to Wales during the miners’ strike in Britain in the 1980s, and Howl’s Moving Castle could be set anywhere.

What are Miyazaki’s films about?Miyazaki likes to tell different types of stories in his films, and he does not make sequels. But certain themes appear again and again. Environmentalism, and humankind’s relationship with nature, are themes that are ever-present in his work.

Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind examines humankind’s propensity to destroy the environment, and looks at how nature cleanses itself from our destructive tendencies. Princess Mononoke explores the conflict between human progress and nature, revolving around an ironworking town in the centre of the forest. Miyazaki, who used to help clean his local rivers, has a complex view of our relationship with the natural world, which manifests itself in his films.

Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984) examines humankind’s tendency to destroy the environment. Photo: Studio Ghibli

Miyazaki tends to focus on female heroines, and his work has a feminist angle. Miyazaki says he likes to create female characters because he does not want his films to reflect only his own experiences. Heroines like the eco-warrior Nausicaa, and the wolf-child San and equivocal Lady Eboshi from Princess Mononoke, are powerful women in control of their own fates, and the destinies of whole cities and countries.

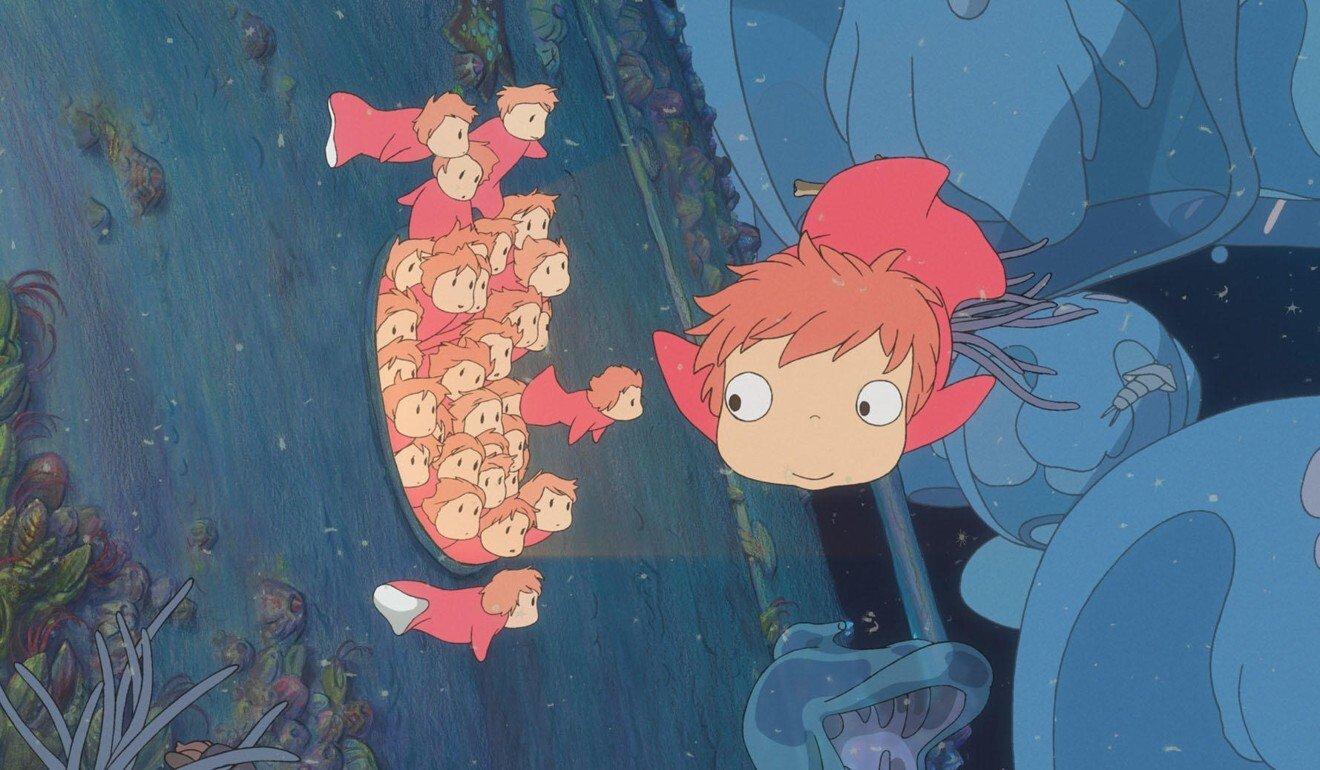

Nausicaa’s self-sacrifice gives her a Joan of Arc-like quality, although Miyazaki has always regretted the religious overtones that crept into the film. Spirited Away and the cheerful Kiki’s Delivery Service are coming-of-age stories about young girls. The strange Ponyo features a girl fish who simply will not stop trying to become a human girl so that she can be with the boy she likes.

Militarism comes up often, most noticeably in Howl’s Moving Castle, which is set during a war, and Nausicaa, which features the military invasion of a peaceful country. Miyazaki is ashamed of the Japanese imperialism of the 20th century, and is highly critical of the mindset behind it. He has said that such imperialism is not representative of all of Japan’s history, and says he tries to look beyond it.

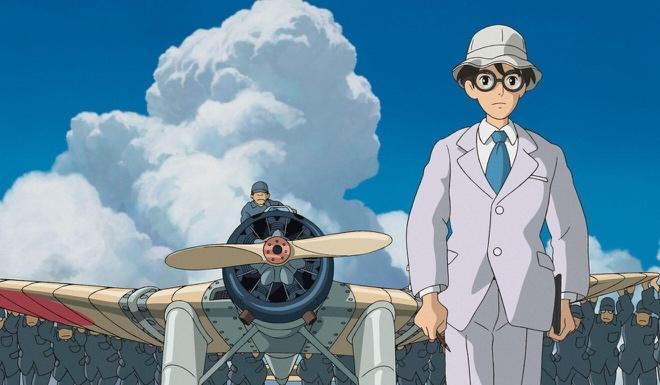

The Wind Rises (2013) shows how benevolent technology can be hijacked by the military for murderous purposes. Photo: Studio Ghibli

His view of the pointlessness of war was also a result of the late-20th century conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, which he says affected him deeply.

The Wind Rises

shows how benevolent technology – in this case, planes – can be hijacked by the military for murderous purposes.

Flying is an activity which Miyazaki loves to animate, and it is a big theme of his films. Miyazaki’s father designed planes, and Ghibli shares its name with an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Miyazaki likes the connection between creative design and engineering that goes into aeroplane design, and thinks it is similar to the process of making animated films. The Wind Rises is about an aeroplane designer.

The way he animates his filmsMiyazaki’s approach to animation is based on Japanese anime, but is uniquely his own. Each of his films looks different, and each uses a unique colour scheme and library of shapes. Like most animators, he is interested in conveying movement, and his acute observational powers – like a painter, he studies the world – have made him the envy of his contemporaries. His skill at depicting human movement has played a big part in his success.

Miyazaki does not favour 3D animation styles like many animators. Japanese anime is characterised by a flat, 2D, hand-drawn look, and Miyazaki has always been a staunch proponent of traditional – and laborious – hand-drawn techniques.

In Princess Mononoke (1997), computer animation was used for the first time to enhance some scenes. Photo: Studio Ghibli

But since Princess Mononoke, Studio Ghibli has used computer animation to enhance some scenes. The studio developed a special programme with an outside company that gives computer animation a hand-drawn look. It is only used to create scenes that could not be drawn by hand, such as the transformation of the great Boar God in Princess Mononoke into a demon.

Miyazaki does not simplify his films for children. In fact, his stories and plots are often complicated, and sometimes even esoteric. Instead of writing the scripts and then adding the animation later – the modern Hollywood way – he focuses on the visual storyboards and then constructs the stories around the images he creates. Miyazaki’s focus on visual storytelling has allowed his imagination free reign.

What are his key films?Miyazaki directs and writes his own films, which are sometimes adaptations of books. Animation is a laborious process, so he has no time to be involved in the Ghibli films he is not writing or directing, such as his son Goro’s debut Tales of Earthsea.

A still from Castle in the Sky (1986), which was retitled Laputa: Castle in the Sky for re-release in the UK and Australia. Photo: Studio Ghibli

He has never made a bad film. The Castle of Cagliostoro, his debut, features conventional animation but the car chases are innovative. The eco-fable Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind is his first masterpiece, setting his visual style and his recurrent themes. Castle in the Sky, about a technological paradise, saw him hone his skills and tell a story that was as grounded as it was phantasmagorical.

My Neighbour Totoro, about a giant forest beast and two children with a sick mother, remains his best loved movie. The barest of storylines is full of emotion and deep observations on childhood, while the characters – especially the much-praised Cat Bus – show Miyazaki working at the height of his powers. Kiki’s Delivery Service again has a modest storyline, about a slightly older girl’s journey into adulthood, that allows his fascination with flight full reign.

Porco Rosso – which features a pig fighter-plane ace – is a deep and thoughtful meditation on war. The epic Princess Mononoke is a multilayered look at the conflict between industrialisation and nature, while Spirited Away focuses on a child’s first experience of loss and independence.

Ponyo (2008) is a bizarre children’s tale about a fish that wants to become a human. Photo: Studio Ghibli

Howl’s Moving Castle features incredible aerial animation, monsters, and a strong anti-war message, as well as notes on growing old. Ponyo, aimed at younger children, is a bizarre tale about a fish that wants to become a human. The Wind Rises is a story about the wonders of flight and the dangers of militarisation.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Storied career of a legendary animator

Through his influences and achievements, Kurosawa became one of the first true international filmmakers, inspiring several generations of filmmakers who would explore notions of genre and identity in film.

Throughout its history, Japan has always championed its culture above outside influence. It grudgingly accepted missionaries in the 16th century only because they could provide ships, goods, gold, and guns. In the 1860s, the nation reluctantly opened its ports to international trade when the United States’ Commodore Perry showcased his fleet’s military force. Cinematically, early Japanese filmmakers, due to government involvement, crafted a style of their own based on Noh theater, patient minimalism, and quiet introspection that was clearly distinct from a Western film of the same period.

Akira Kurosawa, however, was not content to continue this isolated protocol. In post-WWII Japan, at a time when his homeland was being occupied by the United States, Kurosawa chose to look toward and embrace certain Western ideologies of filmmaking. He used Shakespeare and American pulp novels as source material and embraced Hollywood narrative styles and filmmaking techniques. Combining these elements with his own training in the Japanese studio system, Kurosawa was one of the early purveyors of a truly international style, a refined alchemy of filmmaking that was embraced by both West and East. Whereas contemporary Japanese filmmakers such as Ozu and Mizoguchi tended to focus on strictly Japanese elements with a nuanced, patient style that did not find Western audiences for many years, Kurosawa’s body of work was easily relatable across many cultures. Beginning with Rashomon, Kurosawa’s work introduced audiences worldwide to Japanese filmmakers and contemporary Japanese culture.

A lifelong student of dramatic work worldwide, Kurosawa was heavily influenced by authors from Dostoyevsky to Shakespeare. In films such as Throne of Blood and Ran he reinterpreted Macbeth and King Lear as tales of war and political intrigue in feudal Japan. The nature of many of Shakespeare’s tragic characters fit well into the no-nonsense code of the samurai, many of who were likely to encounter downfalls because of their own violent ambitions and the scheming of their colleagues. Shakespeare used a modernized version of history to better relate these stories to his audiences and the political and social realms that they inhabited; Kurosawa did the same for contemporary Japan, blending in elements of Japanese Noh theater to reinterpret the English plays for his audience. Much of the makeup and hairstyles used in these renditions recall the emotive masks used in Noh, often indicating the true nature of a character attempting to hide behind false words.

Throne of Blood

Throne of Blood

Many of Kurosawa’s other works, while not directly based on the Bard’s plays, still contain Shakespearean elements. The inclusion of comedic characters, like the fool, in serious dramas is prevalent in both men’s work. These characters would often serve to relate story and setting elements to the audience, as well as provide moments of levity to offset the often time dire nature of the dramas. Comedic elements were present in some dramatic Hollywood works of the time, but few directors could find a proper balance between lightheartedness and menace, their works often running the risk of becoming hokey or cheesy. In adventures such as The Seven Samurai and The Hidden Fortress, comedic characters form an integral (if sometimes annoying) part of the ensemble.

In later years, this balance of comedy and drama would become essential to the Hollywood blockbuster machine. From war films such as The Dirty Dozen to mob movies such as Goodfellas to literature adaptation such as Lord of the Rings — not to mention the works of Altman, Spielberg, and Tarantino — Hollywood directors have played with the motley ensemble, honing the Shakespearean formula to balance levity and gravity. The concept of balancing comedy with tragedy has been around for centuries in Western literature and theater — but Kurosawa was among the first to execute it so deftly on film, a feat that would be adopted by generations of directors after him and so drive the course of Western filmmaking.

The Hidden Fortress, in particular, exemplifies Shakespeare’s influence on Kurosawa, as well as serving as one of Kurosawa’s most influential films. It may not be a straightforward Shakespearean adaptation, but it contains several elements Kurosawa derived from Shakespeare that became staples of his oeuvre, such as using common citizens to relate an aristocratic morality tale entertainingly. In turn, this type of film became prototypical of the modern Hollywood adventure film.

The Hidden Fortress presents itself as a historical tale, relating the story of deposed Princess Yuki, her loyal General Makabe, and their quest to get the princess and her stockpile of gold to safety. Its moral and historical nature is familiar to Shakespeare’s own — fictionalized characters encounter actual historical events, allowing the author to critique social mores such as greed (material and political), loyalty (to one’s beliefs and friends), class, and the role of women. Kurosawa even revisits some Shakespearean imagery in the forest in which the protagonists become entangled, demonstrating the frequently confusing nature of man’s purpose.

The Hidden Fortress

The Hidden Fortress

It is the use of the fools, however, that draws the greatest line of influence. The film opens with two peasants, Tahei and Matakishi, arguing in the desert. Their dialogue sets up the story’s setting, and throughout the film, their greed and bickering serve as elements of comic relief to offset the deathly serious nature of Toshiro Mifune’s Makabe. Many of these opening shots, particularly when the couple’s backbiting leads to a brief parting, are reminiscent of R2D2 and C3PO’s initial moments on the planet Tatooine in George Lucas’ space opera Star Wars.

The story is initially interpreted through the lowliest characters and then expanded upon as the ensemble grows. Lucas has acknowledged the influence of Kurosawa’s film on his own: the imperiled Princesses Yuki and Leia; Makabe as Obi-Wan (or Han Solo), protecting the princess on her journey; General Tadokoro is Darth Vader. The similarities in the garb, lifestyles, and philosophy between samurai and Jedi are notable, as are filmmaking techniques and props like the frame wipes, which are similar in both films, and the use of swords — whether lightsaber or katana — as the primary weapon.

Shakespeare, Kurosawa, and even Lucas used their melodramas as historical critiques. Julius Caesar, focusing on the death of a ruler and the questions of leadership and civil war that arose after, reflected the questions hanging over the head of British citizens during the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, while both Hidden Fortress and Star Wars involve the questioning of leadership in times of crisis. In Hidden Fortress, Kurosawa also critiques the loyal-to-the-death nature of the samurai code, with Makabe protecting the princess while his family is forced to die. Like some of the more prominent Shakespearean fools, the lower-class characters prove to be more than they initially appear; their greediness merely a result of desperation caused by the not-so-noble ruling class that constitutes the work’s protagonists. The Jedi follow a similar code of conduct to the samurai, but the formers’ ragtag appearance in the earlier films helps them seem nobler against the SS-like Imperial fleet.

This tradition of combining moral and social critiques with crowd-pleasing entertainment is familiar to today’s Hollywood audience and traces its roots back as far as Greek morality plays and Biblical parables. To us, Hidden Fortress, beyond its Star Wars similarities, is a prototypical Hollywood adventure: a no-nonsense hero; a spunky heroine; their greedy comedic sidekicks; a journey composed of a series of increasingly difficult undertakings. Along the way, they meet some friends and enemies, and though things may get tough, our heroes pull through. The cinematography shows a series of beautiful vistas, and the soundtrack’s strings and woodwinds serve to underscore the action and intensify the dramatic — if not operatic — effect. In the end and they have gained some invaluable treasure, and the audience goes home happy. Seem familiar? Ask Indiana Jones.

The Criterion Collection

Home

The Rashomon EffectBy Stephen Prince

When Akira Kurosawa made Rashomon (1950), he was a forty-year-old director working near the beginning of a career that would last fifty years, produce some of the greatest films ever made, and exert a tremendous and lasting influence on filmmaking throughout the world. Rashomon emerged from the journeyman period in his career after he temporarily left Toho, the studio where he’d begun and where he would ultimately make most of his films. During these years, 1949 to 1951, he made movies for Shochiku, Shintoho, and Daiei. Daiei was somewhat reluctant to fund Rashomon, finding the project to be too unconventional and fearing that it would be difficult for audiences to understand. Those fears proved to be groundless—the picture was one of Daiei’s best moneymakers in 1950.

But the film is unconventional, even radical in design, and these attributes only helped to skyrocket it to international fame at a time when art cinema was emerging as a powerful force on the film circuit. With great reluctance, Daiei permitted the film to be submitted for overseas festival competition. Winning first prize at the prestigious Venice Film Festival in 1951, Rashomon announced Kurosawa’s talents, and the treasures of Japanese cinema, to the world at large. The rest, as they say, is history.

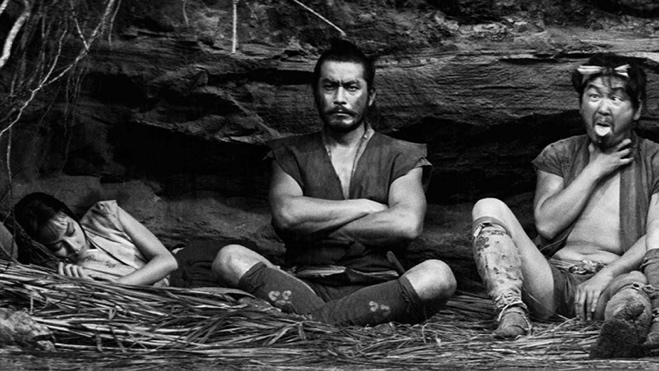

Like most of Kurosawa’s films, Rashomon, based on two stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, is set during a time of social crisis—in this case, the eleventh century in Japan, a period that Kurosawa uses to reveal the extremities of human behavior. As the picture opens, three characters seek shelter from a driving rainstorm (it never sprinklesin a Kurosawa film!) beneath the ruined Rashomon gate that guards the southern entrance to the imperial capital city of Kyoto. As they wait for the storm to pass, the priest (Minoru Chiaki), the woodcutter (Takashi Shimura), and the commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) discuss a recent and scandalous crime—a noblewoman (Machiko Kyo) was raped in the forest, her samurai husband (Masayuki Mori) killed by either murder or suicide, and a thief named Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune) arrested.

When Rashomon played in Venice and then went into international distribution, it stunned audiences. No one had ever seen a film quite like this one. For one thing, its daring, nonlinear approach to narrative shows the details of the crime as they are related, through the flashbacks of those involved. Kurosawa gives us four versions of the same series of events, through the eyes of the woodcutter, the thief, the woman, and the spirit of the husband, each retelling markedly different from the others. Kurosawa’s visionary approach would have enormous cinematic and cultural influence. He bequeathed to world cinema and television a striking narrative device—countless movies and television shows have remade Rashomon by incorporating the contradictory flashbacks of unreliable narrators.

But Rashomon is that rare film that has transcended its own status as film, influencing not just the moving image but the culture at large. Its very name has entered the common parlance to symbolize general notions about the relativity of truth and the unreliability, the inevitable subjectivity, of memory. In the legal realm, for example, lawyers and judges commonly speak of “the Rashomon effect” when firsthand witnesses confront them with contradictory testimony.

Furthermore, the film’s nonlinear narrative marked it as a decisively modernist work, and as a part of the burgeoning world art cinema that was transforming the medium in the 1950s. With Rashomon and his subsequent movies, Kurosawa came to rank among the leading international figures of that cinema, in the company of Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Satyajit Ray. Like their work, Rashomon was more than just commercial entertainment. It was a film of ideas, made by a serious artist, and with a sophisticated aesthetic design.

“Style for Kurosawa is not an empty flourish. The bravura designs of his films are always carefully motivated.”

For it wasn’t only the film’s modernist narrative that impressed audiences and made it a classic. It was also the tremendous visual skill and power that Kurosawa brought to the screen. Like all his best works, Rashomon is a remarkably sensual film. Nobody has ever filmed forests like Kurosawa. Shooting directly into the sun to make the camera lens flare, probing the filaments of shadows in trees and glades, rendering dense thickets as poetic metaphors for the laws of desire and karma that entrap human beings, and, above all, executing hypnotic camera movements across the uneven forest floor, Kurosawa created in Rashomon the most flamboyant and insistently visual film that anyone had seen in decades. All of the critics who reviewed this picture when it first appeared felt compelled to remark upon the beauty of the director’s imagery.

In Rashomon, Kurosawa was consciously attempting to recover and re-create the aesthetic glory of silent filmmaking. Thus, the cinematography (by the brilliant Kazuo Miyagawa) and editing are incredibly vital, and many passages are composed as silent sequences of pure film, in which the imagery, ambient sound, and Fumio Hayasaka’s score carry the action. One of the best such sequences is the long series of moving camera shots that follow the woodcutter into the forest, before he finds the evidence of the crime. These shots, in Kurosawa’s words, lead the viewer “into a world where the human heart loses its way.” Only Kurosawa at his boldest would create such a kinesthetic sequence, in which movement itself—of the camera, the character, and the forest’s foliage—becomes the very point and subject of the scene. Mesmeric, exciting, fluid, and graceful, these are among the greatest moving camera shots in the history of cinema.

Style for Kurosawa is not an empty flourish. The bravura designs of his films are always carefully motivated—this is why he is a great filmmaker. As in all of his outstanding films, in Rashomon Kurosawa is responding to his world as an artist and moralist. The Second World War had devastated Japan. In its aftermath, he embarked— with moral urgency and great artistic ambition—on a series of films (No Regrets for Our Youth, 1946; Drunken Angel, 1948; Stray Dog, 1949) that illuminated the despair and confusion of the period and offered narratives of personal heroism as models for social recovery, seeking, in his art, to produce a legacy of hope for a ruined nation.

The heroism and desire for restoration that these stories embodied, however, had to struggle with a dark opposite. What if the world could not be changed because people themselves are weak and easily corrupted? Kurosawa’s films have a tragic dimension that is rooted in his at times pessimistic reflections on human nature, and Rashomon was the first work in which he allowed that pessimism its full expression. Haunted by the human propensity to lie and deceive, Kurosawa fashioned a tale in which the ego, duplicity, and vanity of the characters make a hell out of the world and make truth a difficult thing to find. Whose account of the crime is reliable? Whose is correct? One cannot tell—all are distorted in ways that flatter their narrators.

This is truly a hellish vision—the world dissolves into nothingness as the illusions of the ego strut like shadows on a shifting landscape. Such a dark portrait was too much even for Kurosawa (at this point in his career, at least, but not in 1985, when he made Ran). Thus, at the last moment, he pulls back from the darkness he has revealed. The woodcutter decides to adopt an abandoned baby, and as he walks off with the child, the rainstorm lifts (Takashi Shimura always supplies the moral center in Kurosawa’s films of the forties and early fifties).

Compassionate action transforms the world—this was Kurosawa’s heroic ideal. Is it enough, however? Each viewer of Rashomon must 9 decide whether this abrupt turnabout at the film’s end is a convincing solution to the moral and epistemological dilemmas that Kurosawa has so powerfully portrayed.

But whatever one decides about the film’s conclusion, Rashomon is the real thing—a genuine classic. Its greatness is palpable and undeniable. Kurosawa’s nonlinear narrative and sensual, kinesthetic style helped to change the face of world cinema. And astonishingly, Kurosawa was still a young filmmaker—so many treasures were yet to come.