This is a Humanities class. No Plagiarism or AI work.... This will be checked. Choose a topic from Module 2, which covers late sixteenth and seventeenth century, that you are really interested in. U

The Italian Renaissance

Top of Form

Search for:

Bottom of Form

The Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance

The art of the Italian Renaissance was influential throughout Europe for centuries.

Learning Objectives

Describe the art and periodization of the Italian Renaissance

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Florence school of painting became the dominant style during the Renaissance . Renaissance artworks depicted more secular subject matter than previous artistic movements.

Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Rafael are among the best known painters of the High Renaissance .

The High Renaissance was followed by the Mannerist movement, known for elongated figures.

Key Terms

fresco: A type of wall painting in which color pigments are mixed with water and applied to wet plaster. As the plaster and pigments dry, they fuse together and the painting becomes a part of the wall itself.

![This is a Humanities class. No Plagiarism or AI work.... This will be checked. Choose a topic from Module 2, which covers late sixteenth and seventeenth century, that you are really interested in. U 1]()

Mannerism: A style of art developed at the end of the High Renaissance, characterized by the deliberate distortion and exaggeration of perspective, especially the elongation of figures.

The Renaissance began during the 14th century and remained the dominate style in Italy, and in much of Europe, until the 16th century. The term “renaissance” was developed during the 19th century in order to describe this period of time and its accompanying artistic style. However, people who were living during the Renaissance did see themselves as different from their Medieval predecessors. Through a variety of texts that survive, we know that people living during the Renaissance saw themselves as different largely because they were deliberately trying to imitate the Ancients in art and architecture.

Florence and the Renaissance

When you hear the term “Renaissance” and picture a style of art, you are probably picturing the Renaissance style that was developed in Florence, which became the dominate style of art during the Renaissance. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Italy was divided into a number of different city states. Each city state had its own government, culture , economy, and artistic style. There were many different styles of art and architecture that were developed in Italy during the Renaissance. Siena, which was a political ally of France, for example, retained a Gothic element to its art for much of the Renaissance.

Certain conditions aided the development of the Renaissance style in Florence during this time period. In the 15th century, Florence became a major mercantile center. The production of cloth drove their economy and a merchant class emerged. Humanism , which had developed during the 14th century, remained an important intellectual movement that impacted art production as well.

Early Renaissance

During the Early Renaissance, artists began to reject the Byzantine style of religious painting and strove to create realism in their depiction of the human form and space . This aim toward realism began with Cimabue and Giotto, and reached its peak in the art of the “Perfect” artists, such as Andrea Mantegna and Paolo Uccello, who created works that employed one point perspective and played with perspective for their educated, art knowledgeable viewer .

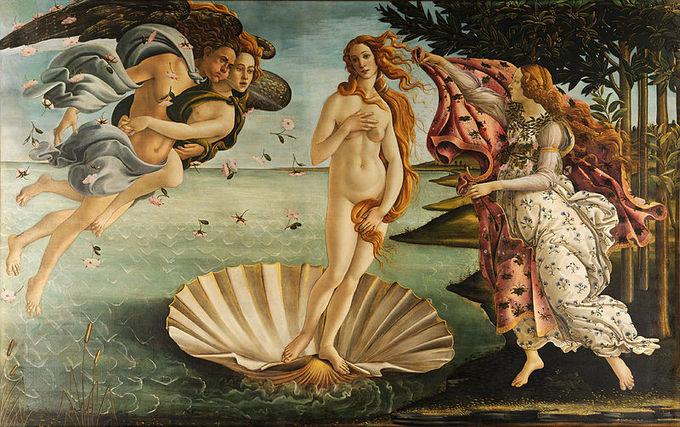

During the Early Renaissance we also see important developments in subject matter, in addition to style. While religion was an important element in the daily life of people living during the Renaissance, and remained a driving factor behind artistic production, we also see a new avenue open to panting—mythological subject matter. Many scholars point to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus as the very first panel painting of a mythological scene. While the tradition itself likely arose from cassone painting, which typically featured scenes from mythology and romantic texts, the development of mythological panel painting would open a world for artistic patronage , production, and themes.

Birth of Venus: Botticelli’s Birth of Venus was among the most important works of the early Renaissance.

High Renaissance

The period known as the High Renaissance represents the culmination of the goals of the Early Renaissance, namely the realistic representation of figures in space rendered with credible motion and in an appropriately decorous style. The most well known artists from this phase are Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and Michelangelo. Their paintings and frescoes are among the most widely known works of art in the world. Da Vinci’s Last Supper, Raphael’s The School of Athens and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling paintings are the masterpieces of this period and embody the elements of the High Renaissance.

Marriage of the Virgin, by Raphael: The painting depicts a marriage ceremony between Mary and Joseph.

Mannerism

High Renaissance painting evolved into Mannerism in Florence. Mannerist artists, who consciously rebelled against the principles of High Renaissance, tended to represent elongated figures in illogical spaces. Modern scholarship has recognized the capacity of Mannerist art to convey strong, often religious, emotion where the High Renaissance failed to do so. Some of the main artists of this period are Pontormo, Bronzino, Rosso Fiorentino, Parmigianino and Raphael’s pupil, Giulio Romano.

Humanism

Humanism was an intellectual movement embraced by scholars, writers, and civic leaders in 14th century Italy.

Learning Objectives

Assess how Humanism gave rise to the art of the Renasissance

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Humanists reacted against the utilitarian approach to education, seeking to create a citizenry who were able to speak and write with eloquence and thus able to engage the civic life of their communities.

The movement was largely founded on the ideals of Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca, which were often centered around humanity’s potential for achievement.

While Humanism initially began as a predominantly literary movement, its influence quickly pervaded the general culture of the time, reintroducing classical Greek and Roman art forms and leading to the Renaissance .

Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, known especially for his Humanist, and unusually erotic, statue of David.

While medieval society viewed artists as servants and craftspeople, Renaissance artists were trained intellectuals, and their art reflected this newfound point of view.

In humanist painting, the treatment of the elements of perspective and depiction of light became of particular concern.

Key Terms

High Renaissance: The period in art history denoting the apogee of the visual arts in the Italian Renaissance. The High Renaissance period is traditionally thought to have begun in the 1490s—with Leonardo’s fresco of The Last Supper in Milan and the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence—and to have ended in 1527, with the Sack of Rome by the troops of Charles V.

Overview

Humanism, also known as Renaissance Humanism, was an intellectual movement embraced by scholars, writers, and civic leaders in 14th- and early-15th-century Italy. The movement developed in response to the medieval scholastic conventions in education at the time, which emphasized practical, pre-professional, and scientific studies engaged in solely for job preparation, and typically by men alone. Humanists reacted against this utilitarian approach, seeking to create a citizenry who were able to speak and write with eloquence and thus able to engage the civic life of their communities. This was to be accomplished through the study of the “studia humanitatis,” known today as the humanities: grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. Humanism introduced a program to revive the cultural—and particularly the literary—legacy and moral philosophy of classical antiquity . The movement was largely founded on the ideals of Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca, which were often centered around humanity’s potential for achievement.

While Humanism initially began as a predominantly literary movement, its influence quickly pervaded the general culture of the time, re-introducing classical Greek and Roman art forms and contributing to the development of the Renaissance. Humanists considered the ancient world to be the pinnacle of human achievement, and thought its accomplishments should serve as the model for contemporary Europe. There were important centers of Humanism in Florence, Naples, Rome , Venice , Genoa, Mantua, Ferrara, and Urbino .

Humanism was an optimistic philosophy that saw man as a rational and sentient being, with the ability to decide and think for himself. It saw man as inherently good by nature, which was in tension with the Christian view of man as the original sinner needing redemption. It provoked fresh insight into the nature of reality, questioning beyond God and spirituality, and provided knowledge about history beyond Christian history.

Humanist Art

Renaissance Humanists saw no conflict between their study of the Ancients and Christianity. The lack of perceived conflict allowed Early Renaissance artists to combine classical forms, classical themes, and Christian theology freely. Early Renaissance sculpture is a great vehicle to explore the emerging Renaissance style . The leading artists of this medium were Donatello, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Lorenzo Ghiberti. Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, known especially for his classical, and unusually erotic, statue of David, which became one of the icons of the Florentine republic.

Donatello’s David: Donatello’s David is regarded as an iconic Humanist work of art.

Humanism affected the artistic community and how artists were perceived. While medieval society viewed artists as servants and craftspeople, Renaissance artists were trained intellectuals, and their art reflected this newfound point of view. Patronage of the arts became an important activity, and commissions included secular subject matter as well as religious. Important patrons , such as Cosimo de’ Medici, emerged and contributed largely to the expanding artistic production of the time.

In painting, the treatment of the elements of perspective and light became of particular concern. Paolo Uccello, for example, who is best known for “The Battle of San Romano,” was obsessed by his interest in perspective, and would stay up all night in his study trying to grasp the exact vanishing point . He used perspective in order to create a feeling of depth in his paintings. In addition, the use of oil paint had its beginnings in the early part of the 16th century, and its use continued to be explored extensively throughout the High Renaissance .

“The Battle of San Romano” by Paolo Uccello: Italian Humanist paintings were largely concerned with the depiction of perspective and light.

Origins

Some of the first Humanists were great collectors of antique manuscripts, including Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Coluccio Salutati, and Poggio Bracciolini. Of the three, Petrarch was dubbed the “Father of Humanism” because of his devotion to Greek and Roman scrolls. Many worked for the organized church and were in holy orders (like Petrarch), while others were lawyers and chancellors of Italian cities (such as Petrarch’s disciple Salutati, the Chancellor of Florence) and thus had access to book-copying workshops.

In Italy, the Humanist educational program won rapid acceptance and, by the mid-15th century, many of the upper classes had received Humanist educations, possibly in addition to traditional scholastic ones. Some of the highest officials of the church were Humanists with the resources to amass important libraries. Such was Cardinal Basilios Bessarion, a convert to the Latin church from Greek Orthodoxy, who was considered for the papacy and was one of the most learned scholars of his time.

Following the Crusader sacking of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, the migration of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés, who had greater familiarity with ancient languages and works, furthered the revival of Greek and Roman literature and science.

Donatello’s Sublime Enigma The sculptor’s ‘Penitent Magdalene’ is surrounded by a sense of timelessness.By Tom L. Freudenheim

Dec. 30, 2016 1:01 pm ET

A rich literary and visual tradition surrounds Mary Magdalene, one of Christianity’s most elusive figures. She is described in the Gospel of St. Luke as the woman “who lived a sinful life…[and] stood behind [Jesus] at his feet weeping [and] began to wet his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them and poured perfume on them.” After reciting one of his parables, Jesus told her “your sins are forgiven.”

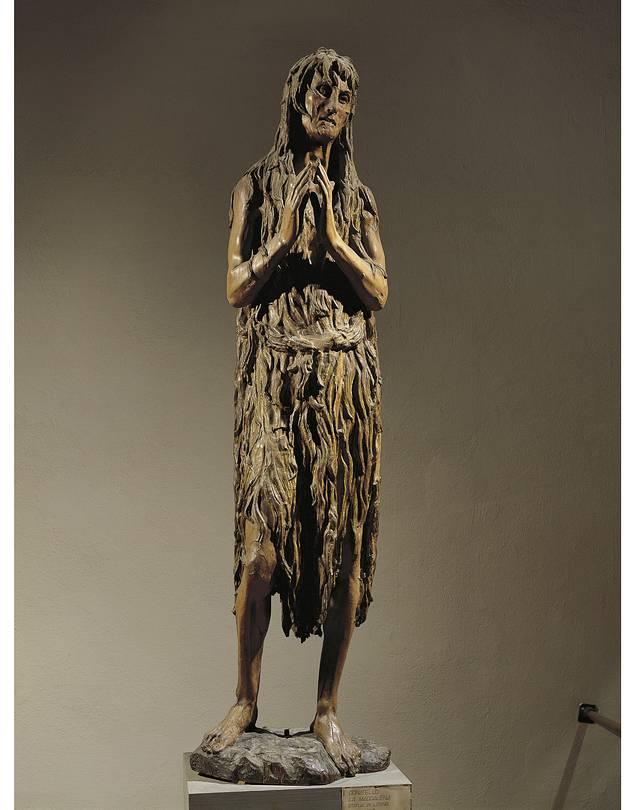

Among the most sublime and emotionally resonant figures in all of Italian Renaissance art, Donatello’s “Penitent Magdalene” appears to have been inspired more by the various biblical texts (she is mentioned in all four Gospels) than by earlier visual versions, of which there are many.

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (c. 1386-1466), known as Donatello, was born in Florence, and early on spent formative time in Rome, where a mania for excavating and learning from the antique held many artists in thrall. The arc of his work defines the development of Italian Renaissance sculpture, ranging from the majestic St. John the Evangelist (1409-11), whose graceful, if inert, heft still reflects the late Gothic taste in sculpture, to the grand equestrian “Gattamelata” (1450)—the first such heroic work since antiquity.

Photo: DeAgostini/Getty Images

Similarly, Donatello’s marble “David” (1408-09) presents an elegant figure who nevertheless comes across as somewhat wimpy, despite the rock in the fallen giant Goliath’s head at David’s feet. Taking up the same subject three decades later, however, Donatello moves Western art forward radically, both in figural attitude and in the development of bronze casting. This homoerotic naked David calmly triumphs over his adversary with placid facial attitude yet a balletic, if aggressive, posture. Michelangelo’s celebrated “David” (1501-04), alluding to ancient Roman sculpture in all its impassive monumentality, is in certain ways a response to Donatello’s more lyrical second work.

The mystery of Donatello’s “Penitent Magdalene” (1453-55), now in Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo (Cathedral Museum), seems far from the competing creative egos of an extraordinarily fertile time in art. Perhaps commissioned for the Baptistry, where it long stood, this dour carved wooden figure suggests that we put aside our admiration for the wonders of Italian Renaissance art to concentrate on devotion and personal anguish. This is not the Magdalene who wiped Jesus’ feet with her hair. It’s more likely the Magdalene who witnessed the Crucifixion. Or maybe not.

One of the most enigmatic figures in art, the sculpture’s gender seems never to have been in question. Raffaello Borghini’s 1584 art historical text, “Il Riposo,” says that “she is consumed by fasting and abstinence, and every part of her body shows a perfect knowledge of anatomy.” And a guidebook of 1591 claims that the work “is so beautifully designed that she resembles nature in every way and seems alive.”

But to this viewer, the figure looks more like a character whose female anatomy is barely discernible under a garment that we can identify as hair primarily because it’s a continuation of her own long hair, making her at once fully clothed and yet somehow very naked. The musculature expressed in exposed arms and legs prefigures the gender-bending women of Michelangelo’s Medici tomb sculptures. Yet the delicacy of the figure’s raised hands, slender fingers not quite connected in prayer, is almost incongruous against her apparently ravaged face. The toenails on her finely carved feet add an expressive note, as do the bone structure and sinews of the legs and the slight rise of her right foot with its barely perceptible suggestion of movement.

During the terrible 1966 Florence flood, the figure’s lower half was immersed in water and heavily stained with oil, causing the thighs to crack in two places. Thanks to heroic salvage and restoration efforts, the Magdalene allegedly now looks much as it did when first created: the brown monochrome wood figure manifests barely any color differentiation between skin and hair/garment. That gives her the sense of timelessness we associate with characters we love in literature and art, whose biographies we feel we know even when we don’t. We share their joys and sorrows, because they are projections of ourselves.

But with the “Penitent Magdalene”—a solitary figure beautifully displayed in a gallery so that we can keep walking around it—the viewer never quite grasps it all, because the artist’s ideas, more than half a millennium away, will always remain as elusive as they are seductive.

—Mr. Freudenheim, a former art-museum director, served as the assistant secretary for museums at the Smithsonian.

Why the Mannerists’ Bizarre Paintings Deserve a Second LookJackson Arn

Nov 26, 2018 4:24pm

Francesco Mazzola, called Parmigianino

Madonna with the Long Neck, 1534-1540

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Agnola Bronzino, Portrait of Lodovico Capponi, 1550–55. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Among the thousands of un-babyish babies in Italian art—a group big and bizarre enough to merit its own Tumblr—there are none quite like the infant Jesus in

Parmigianino

’s Madonna and Child with Angels (1534–40). Though clearly a newborn, Jesus must be well over 2 feet tall, most of that height contained in his long, skinny torso. Then there’s the infant’s lazy, almost languorous pose. He dangles precariously off of his mother’s lap; judging from the slope of Mary’s thigh, baby Jesus is about to slide to the floor. Not many people notice this accident-in-the-making the first time they see Parmigianino’s painting, probably because they’re too busy gaping at an even more bizarre feature of the work, the one that gave it its informal, better-known title: Madonna with the Long Neck.

Learning about

Mannerism

—the movement that arose in Italy in the early 16th century, of which Madonna of the Long Neck is a favorite example—means stumbling upon unbridled weirdness in works of art that might seem dully conventional at first glance. No wonder Mannerism remains a contentious topic for academics: There seems to be some kind of requirement that every essay on the term begin by acknowledging how fiendishly difficult it is to define. Many art historians see the movement as a transitional one, jammed uncomfortably between the

High Renaissance

achievements of

Michelangelo

,

Leonardo

, and

Raphael

at the end of the 15th century and the extravagances of the

Baroque

era at the start of the 17th. They break it down by its key members (Parmigianino,

Agnolo Bronzino

,

Benvenuto Cellini

,

Jacopo da Pontormo

,

Rosso Fiorentino

) and defining features: bright colors, contorted figures, indeterminate spaces, and an overpowering sense of artificiality.

It might be better to understand Mannerism by getting a sense of what it was like to be a young painter in Italy at the beginning of the 16th century. The masters of the preceding generation had produced works that represented, at that moment in time, the apex of dramatic, lifelike painting. The smothering greatness of their achievements ushered in what Susan Sontag called a “late moment” in culture—an era whose peaks are already past—“that presumes an endless discourse anterior to itself.” For the younger generation, making art in the shadows of these giants must have been intimidating, to say the least.

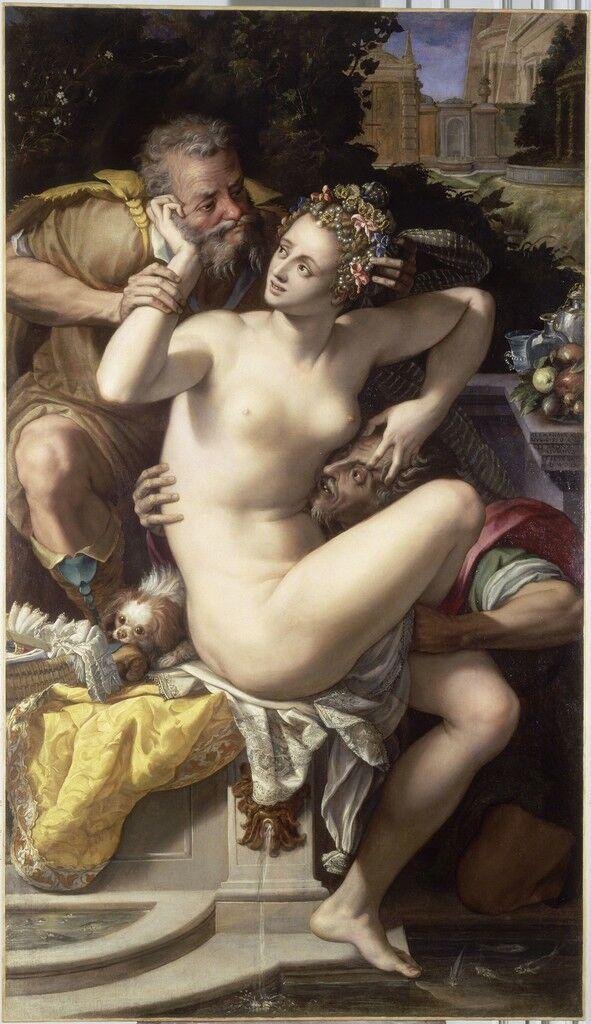

Alessandro Allori

Suzanne et les vieillards (Susanna and the elders)

Musée Magnin

Jacopo da Pontormo

The Deposition, 1525-1528

Santa Felicita, Florence

In our own late moment, already poised to be remembered as the “Age of the Remix,” some postmodern artists have problematized the concept of originality, choosing to reinterpret old styles and forms, rather than start from scratch. Something roughly similar could be said for the Mannerist painters who emerged in the 1520s: The High Renaissance was like an austere parent, one they imitated and occasionally parodied, but could not ignore. “The strongest impression left behind by a typical Mannerist painting,” art historian Eric Newton once wrote, “is that the artist has derived hardly anything direct from nature, but has absorbed, digested, and stylized the paintings of others.” That’s an apt way to characterize Madonna with the Long Neck: It’s as if Parmigianino is playing a pictorial version of the telephone game, copying endless copies of Renaissance masterpieces until the image has mutated into something wilder than Raphael could have ever imagined.

Much as some contemporary artists use humor to distance themselves from their historical precedents, the Italian Mannerists often presented their Renaissance homages in a lighthearted spirit. Over the centuries, many have confused this playfulness with slightness, interpreting it as a tacit admission that Mannerism was just a knockoff of what came before. Until well into the 20th century, in fact, Mannerist painters were by and large considered minor figures in the canon. More recently, art historians have tended to see inventiveness where others once saw stagnation. In a famous 1964 essay, Sontag found in Mannerism an ancestor of the modern Camp sensibility—“a love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,” she wrote. New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl echoed Sontag’s point when he wrote that “we are mostly Mannerists now. Art about art, and style for style’s sake.” Mannerists may not have surpassed Michelangelo, exactly, but they found freedom in subservience, taking pleasure in an ironic form of imitation that was part homage, part parody.

The problem with irony is that some people won’t recognize it. The Florentine painter Bronzino is an excellent case in point: His reputation has gone up and down over the centuries, and his works, like Mannerism itself, are often described as “cold”—technically brilliant, but emotionless. Bronzino’s portrait of Lodovico Capponi, completed between 1550 and 1555, shows its young subject—a page in the Medici court—standing against a green curtain, so that viewers have no idea where he really is. His long, clever fingers; slightly pursed lips; and narrowed eyes make him seem menacing and faintly revolting, like a 16th-century Italian Draco Malfoy.

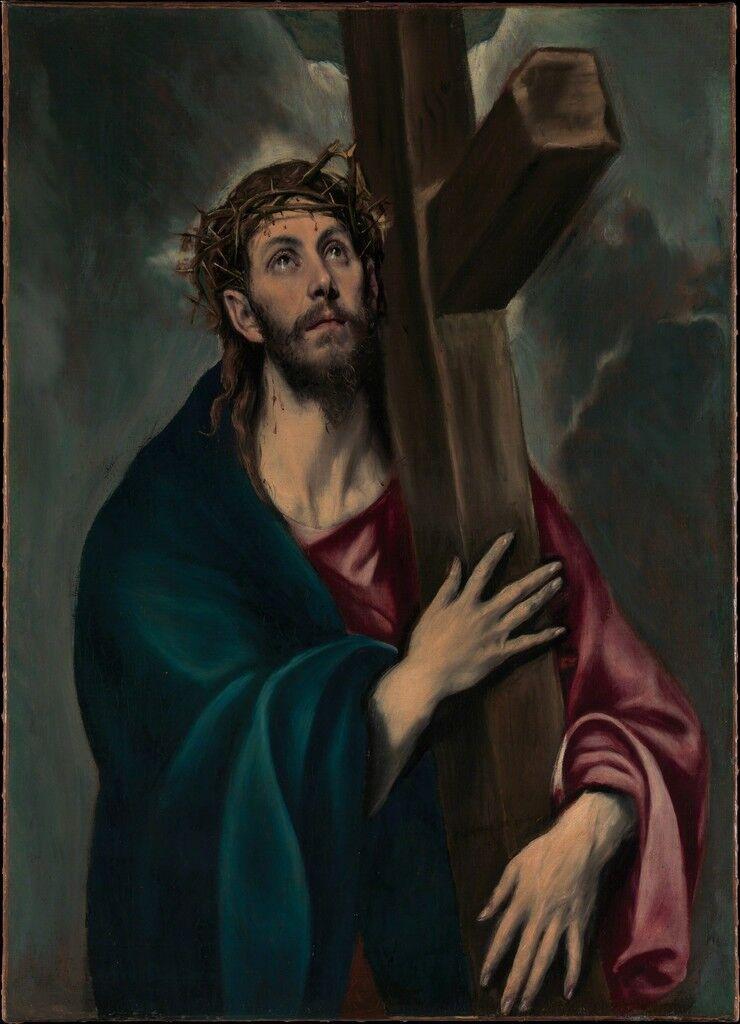

El Greco

Christ Carrying the Cross, ca. 1577–1587

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Four Seasons in One Head, ca. 1590

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Permanent collection

Advertisement

Yet it’s simply wrong to say that this is a “cold” portrait. In a sense, Bronzino presents his viewers with a mask, the kind that many callow, insecure young men still wear today. But he also offers us a glimpse underneath that mask: Witness the medallion Lodovico carries in his right hand, which depicts a woman’s face. It’s crucial to know that at the time he sat for this portrait, Lodovico was having a passionate affair with a woman who’d already been chosen as a bride for a member of the Medici family. Historians have suggested that Bronzino knew about the affair when he painted the portrait, and in this way, the work’s apparent chilliness becomes a joke, even a rather sweet one: No matter how hard this kid tries to model himself off of older, haughtier courtiers, he remains, at heart, a starry-eyed softie.

In the past 50 years or so, Mannerism has made a major comeback, to the point where scholars are trying to claim certain radical 16th-century artists as Mannerists, even if their works traditionally haven’t been studied through such a lens. The delightful paintings of

Guiseppe Arcimoldo

, which depict human beings built out of fruits, books, flowers, and more, may not seem to have much in common with the excessively stylized works of Bronzino or Parmigianino, but their vivid colors and cheeky humor make them excellent candidates. For that matter, the notion of using old or inanimate fragments to build something lively and new almost sounds like a metaphor for the Mannerist aesthetic.

Then there’s

El Greco

, the notoriously unclassifiable, late-16th-century painter who lived in Spain for most of his adult life. Studying in Venice and Rome as a young man, he would have come across many of the key Mannerist works, and later on, he carried their influence—along with that of Byzantine icons and Michelangelo’s sculptures—with him to Toledo. The long, slender martyr in Christ Carrying the Cross (ca. 1577–87) bears a clear resemblance to Parmigianino’s figures—he’s like the man the baby in Madonna of the Long Neck grows up to be—and yet, it would be hard to confuse Parmigianino’s paintings for El Greco’s. In the best Mannerist works, the emotional meaning has to be teased out, slowly and carefully; in El Greco’s, strong emotion soaks through every square inch of the canvas, and the force of the figures’ faith or suffering or joy threatens to tear them to bits. Mannerism’s gaze is fixed on the High Renaissance; even when he’s consciously imitating earlier artists, El Greco seems to be looking forward hundreds of years to Cubism Expressionism, and even Abstract Expressionism

But whether El Greco was or wasn’t a card-carrying Mannerist isn’t really the point: He studied Mannerism for years, and in the process of imitating this highly imitative movement, he happened upon a style all his own. His work—give it whatever label you like—proves that artists can mimic and be highly original at the same time. That’s the thesis to which the Mannerists devoted their careers, one that’s crucial to bear in mind when we look at their paintings today.

Jackson Arn