This is a Humanities class. No Plagiarism or AI work.... This will be checked. Choose a topic from Module 2, which covers late sixteenth and seventeenth century, that you are really interested in. U

The Northern Renaissance

Top of Form

Search for:

Bottom of Form

The Northern Renaissance

The Northern Renaissance

Before 1450, Renaissance humanism had little influence outside Italy; after 1450, these ideas began to spread throughout Europe.

Learning Objectives

Describe how the Northern Renaissance differed from the Italian Renaissance

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Humanism influenced the Renaissance periods in Germany, France, England, the Netherlands, and Poland. There were also other national and localized movements, each with different characteristics and strengths.

Northern painters in the 16th century increasingly looked to Rome for influence, and became known as the Romanists . The High Renaissance art of Michelangelo and Raphael and the stylistic tendencies of Mannerism also had a great impact on their work.

Although Renaissance humanism and the large number of surviving classical artworks and monuments in Italy encouraged many Italian painters to explore Greco-Roman themes, Northern Renaissance painters developed other subject matters, such as landscape and genre painting.

Key Terms

Romanists: A group of artists in the late 15th and early 16th century from the Netherlands who began to visit Italy and started to incorporate Renaissance influences in their work.

Northern Renaissance: The Northern Renaissance describes the Renaissance as it occurred in northern Europe.

The Northern Renaissance describes the Renaissance in northern Europe. Before 1450, Renaissance humanism had little influence outside Italy; however, after 1450 these ideas began to spread across Europe. This influenced the Renaissance periods in Germany, France, England, the Netherlands, and Poland. There were also other national and localized movements. Each of these regional expressions of the Renaissance evolved with different characteristics and strengths. In some areas, the Northern Renaissance was distinct from the Italian Renaissance in its centralization of political power. While Italy and Germany were dominated by independent city-states , parts of central and western Europe began emerging as nation-states. The Northern Renaissance was also closely linked to the Protestant Reformation , and the long series of internal and external conflicts between various Protestant groups and the Roman Catholic Church had lasting effects.

As in Italy, the decline of feudalism opened the way for the cultural, social, and economic changes associated with the Renaissance in northern Europe. Northern painters in the 16th century increasingly looked to Rome for influence, and became known as the Romanists. The High Renaissance art of Michelangelo and Raphael and the stylistic tendencies of Mannerism had a significant impact on their work. Although Renaissance humanism and the large number of surviving classical artworks and monuments in Italy encouraged many Italian painters to explore Greco-Roman themes, Northern Renaissance painters developed other subject matters, such as landscape and genre painting.

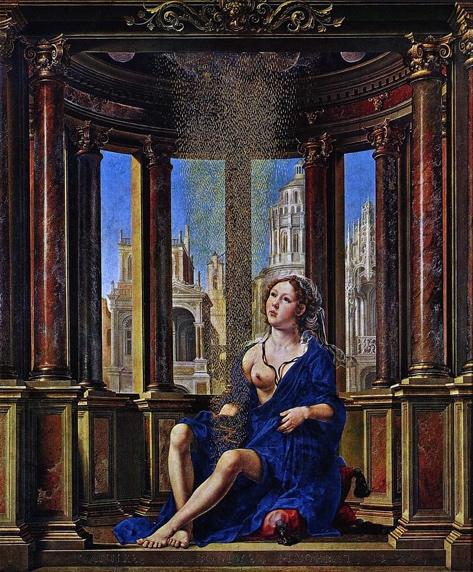

Danae by Jan Mabuse: One of the most well-known Romanists was Jan Mabuse. The influence of Michelangelo and Raphael showed in the use of mythology and nudity in this particular piece.

As Renaissance art styles moved through northern Europe, they were adapted to local customs. For example, in England and the northern Netherlands, the Reformation nearly ended the tradition of religious painting. In France, the School of Fontainebleau, which was originally founded by Italians such as Rosso Fiorentino, succeeded in establishing a durable national style. Finally, by the end of the 16th century, artists such as Karel van Mander and Hendrik Goltzius collected in Haarlem in a brief but intense phase of Northern Mannerism that also spread to Flanders .

Impact of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation was a religious movement in the 16th century that resulted in the theological divide between Roman Catholics and Protestants.

Learning Objectives

Describe the Protestant Reformation and its effects on Western European art of the 16th century

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Art that portrayed religious figures or scenes followed Protestant theology by depicting people and stories accurately and clearly and emphasized salvation through divine grace, rather than through personal deeds, or by intervention of church bureaucracy.

Reformation art embraced Protestant values , although the amount of religious art produced in Protestant countries was hugely reduced. Instead, many artists in Protestant countries diversified into secular forms of art like history painting , landscapes, portraiture, and still life .

The Protestant Reformation induced a wave of iconoclasm , or the destruction of religious imagery , among the more radical evangelists.

Key Terms

Protestant Reformation: The 16th century schism within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other early Protestants; characterized by the objection to the doctrines, rituals, and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church and led to the creation of Protestant churches, which were outside of the control of the Vatican.

iconoclasm: The belief in, participation in, or sanction of destroying religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually with religious or political motives.

The Protestant Reformation and Art

The Protestant Reformation was a religious movement that occurred in Western Europe during the 16th century that resulted in the theological divide between Roman Catholics and Protestants. This movement created a North-South split in Europe, where generally Northern countries became Protestant, while Southern countries remained Catholic. Protestant theology centered on the individual relationship between the worshiper and the divine, and accordingly, the Reformation’s artistic movement focused on the individual’s personal relationship with God. This was reflected in a number of common people and day-to-day scenes depicted in art.

The Reformation ushered in a new artistic tradition that highlighted the Protestant belief system and diverged drastically from southern European humanist art produced during the High Renaissance . Reformation art embraced Protestant values, although the amount of religious art produced in Protestant countries was hugely reduced (largely because a huge patron for the arts—the Catholic Church—was no longer active in these countries). Instead, many artists in Protestant countries diversified into secular forms of art like history painting, landscapes, portraiture, and still life.

Art that portrayed religious figures or scenes followed Protestant theology by depicting people and stories accurately and clearly and emphasized salvation through divine grace, rather than through personal deeds, or by intervention of church bureaucracy. This is the direct influence of one major criticism of the Catholic Church during the Reformation—that painters created biblical scenes that strayed from their true story, were hard to identify, and were embellished with painterly effects instead of focusing on the theological message. In terms of subject matter, iconic images of Christ and scenes from the Passion became less frequent, as did portrayals of the saints and clergy. Instead, narrative scenes from the Bible and moralistic depictions of modern life became prevalent.

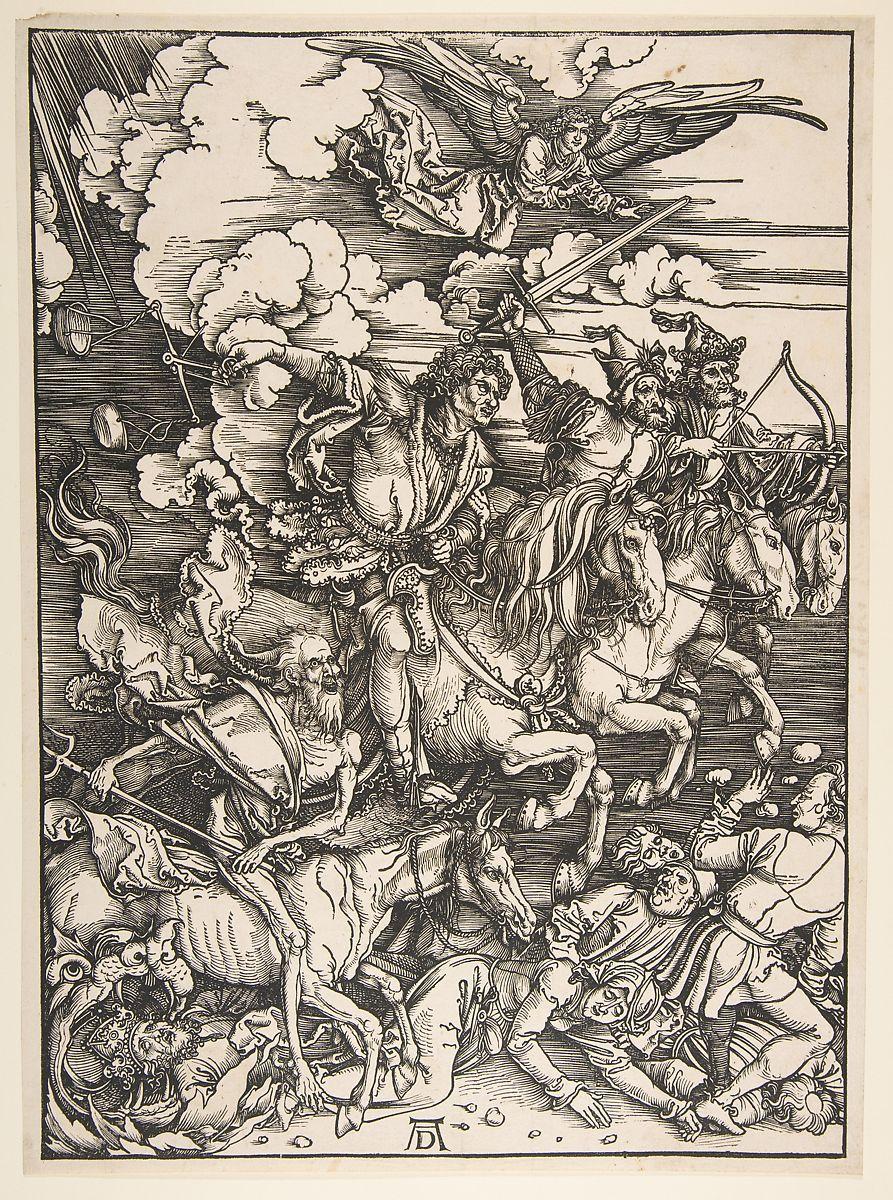

The Protestant Reformation also capitalized on the popularity of printmaking in northern Europe. Printmaking allowed images to be mass produced and widely available to the public at low cost. The Protestant church was therefore able to bring their theology to the people through portable, inexpensive visual media . This allowed for the widespread availability of visually persuasive imagery. With the great development of the engraving and printmaking market in Antwerp in the 16th century, the public was provided with accessible and affordable images. Many artists provided drawings to book and print publishers.

Iconoclasm and Resistance to Idolatry

All forms of Protestantism showed a degree of hostility to religious images, especially sculpture and large paintings, considering them forms of idol worship. After the early years of the Reformation, artists in Protestant areas painted far fewer religious subjects for public display, partly because religious art had long been associated with the Catholic Church. Although, there was a conscious effort to develop a Protestant iconography of Bible images in book illustrations and prints. During the early Reformation, some artists made paintings for churches that depicted the leaders of the Reformation in ways very similar to Catholic saints. Later, Protestant taste turned away from the display of religious scenes in churches, although some continued to be displayed in homes.

There was also a reaction against images from classical mythology, the other manifestation of the High Renaissance at the time. This brought about a style that was more directly related to accurately portraying the present times. For example, Bruegel’s Wedding Feast portrays a Flemish-peasant wedding dinner in a barn. It makes no reference to any religious, historical, or classical events, and merely gives insight into the everyday life of the Flemish peasant.

Bruegel’s Peasant Wedding: Bruegael’s Peasant Wedding is a painting that captures the Protestant Reformation artistic tradition: focusing on scenes from modern life rather than religious or classical themes.

The Protestant Reformation induced a wave of iconoclasm, or the destruction of religious imagery, among the more radical evangelists. Protestant leaders, especially Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin, actively eliminated imagery from their churches and regarded the great majority of religious images as idolatrous—even plain crosses. On the other hand, Martin Luther encouraged the display of a restricted range of religious imagery in churches. For the most part, however, Reformation iconoclasm resulted in a disappearance of religious figurative art, compared with the amount of secular pieces that emerged.

Iconoclasm: Catholic Altar Piece: Altar piece in St. Martin’s Cathedral, Utrecht, attacked in the Protestant iconoclasm in 1572. This retable became visible again after restoration in 1919 removed the false wall placed in front of it.

Antwerp: A Center of the Northern Renaissance

Antwerp, located in Belgium, was a center for art in the Netherlands and northern Europe for much of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Learning Objectives

Describe the characteristics of Antwerp Mannerism

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The Antwerp School for painting flourished during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Antwerp School comprised many generations of artists and is known for portraiture, animal paintings, still lifes, and prints.

Antwerp Mannerism bore no relation to Renaissance Mannerism, but the name suggests a reaction to the “classic” style of the earlier Flemish painters. Although attempts have been made to identify individual artists, most paintings remain attributed to anonymous masters.

Antwerp was an internationally significant publishing center, with prodigious production of old master prints and book illustrations. Furthermore, Antwerp animaliers, or animal painters, such as Frans Snyders, Jan Fyt, and Paul de Vos, dominated animal painting in Europe.

Key Terms

Antwerp School: The Antwerp School is a term for the artists active in Antwerp, first during the 16th century when the city was the economic center of the Low Countries, and then during the 17th century when it became the artistic stronghold of the Flemish Baroque under Peter Paul Rubens.

Antwerp: A province of Flanders, Belgium.

Antwerp, located in present-day Belgium, was a center for art in the Netherlands and northern Europe for much of the 16th and 17th centuries. The so-called Antwerp School for painting flourished during the 16th century when the city was the economic center of the Low Countries, and again during the 17th century when it became the artistic stronghold of the Flemish Baroque . The Antwerp School comprised many generations of artists and is known for portraiture, animal paintings, still lifes, and prints.

Antwerp became the main trading and commercial center of the Low Countries around 1500, and the boost in the economy attracted many artists to the cities to join craft guilds . For example, many 16th century painters, artists, and craftsmen joined the Guild of Saint Luke, which educated apprentices and guaranteed quality. The first school of artists to emerge in the city were the Antwerp Mannerists , a group of anonymous late Gothic painters active in the city from about 1500 to 1520.

Antwerp Mannerism bore no direct relation to Renaissance or Italian Mannerism, but the name suggests a style that was a reaction to the “classic” style of the earlier Flemish painters. Although attempts have been made to identify individual artists, most paintings remain attributed to anonymous masters. Characteristic of Antwerp Mannerism are paintings that combine early Netherlandish and Northern Renaissance styles, and incorporate both Flemish and Italian traditions into the same compositions . Practitioners of the style frequently painted subjects such as the Adoration of the Magi and the Nativity, both of which are generally represented as night scenes, crowded with figures and dramatically illuminated. The Adoration scenes were especially popular with the Antwerp Mannerists, who delighted in the patterns of the elaborate clothes worn by the Magi and the ornamentation of the architectural ruins in which the scene was set.

The Adoration of the Kings by Jan Gossaert: This painting captures the Antwerp Mannerist tradition of using religious themes, particularly the Adoration of the Magi, for inspiration.

The iconoclastic riots (“Beeldenstorm” in Dutch) of 1566 that preceded the Dutch Revolt resulted in the destruction of many works of religious art , after which time the churches and monasteries had to be refurnished and redecorated. Artists such as Otto van Veen and members of the Francken family, working in a late Mannerist style, provided new religious decoration. These also marked the beginning of economic decline in the city, as the Scheldt river was blockaded by the Dutch Republic in 1585 and trade restricted.

The city experienced an artistic renewal in the 17th century. The large workshops of Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens, along with the influence of Anthony van Dyck, made Antwerp the center of the Flemish Baroque. The city was an internationally significant publishing center, with prodigious production of old master prints and book illustrations. Furthermore, Antwerp animaliers or animal painters, such as Frans Snyders, Jan Fyt ,and Paul de Vos, dominated animal painting in Europe for at least the first half of the century. But as the economy continued to decline, and the Habsburg nobility and the Church reduced their patronage , many artists trained in Antwerp left for the Netherlands, England, France, or elsewhere. By the end of the 17th century, Antwerp was no longer a major artistic center.

Hunting Trophies: Jan Fyt, a member of the Antwerp School, was well known for the use of animal motifs in his paintings.

Albrecht Dürer: The painter with 'a magical touch'

(Image credit: The Albertina Museum, Vienna)

By Kelly Grovier19th September 2019

Originally finding fame for his woodcuts, the 16th-Century German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer “collapses the world” between observers today and his paintings created 500 years ago.

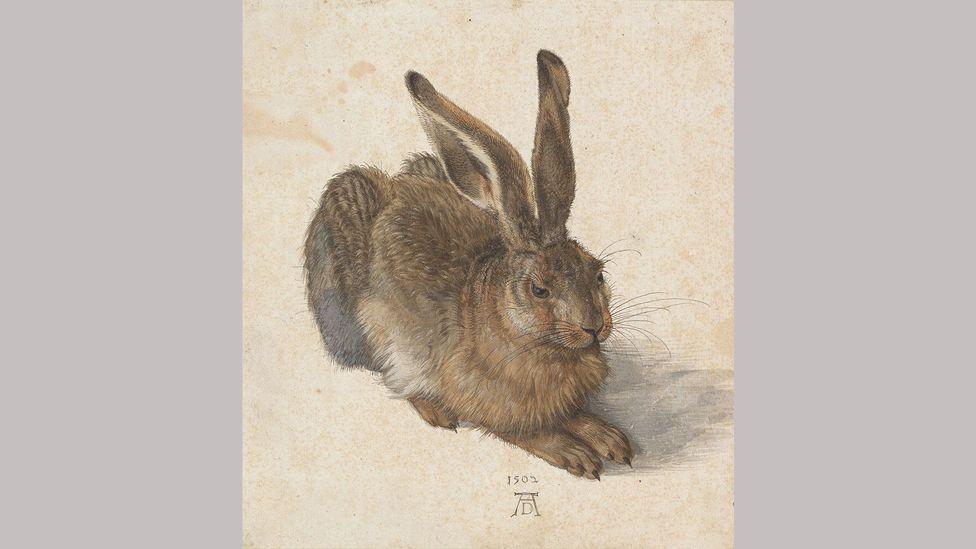

If you look closely, very closely, you can see it in the corner of the hunkered hare’s eye: not merely a pair of concentric glints echoing from its dark cornea, but a portal to the past. A miracle of focused observation and precise draughtsmanship, the famous watercolour, which faithfully transcribes every soft filament of the mammal’s fur, was created by pioneering German Renaissance painter, printmaker, and theorist Albrecht Dürer in 1502. It is now among the highlights of a new exhibition at the Albertina Museum in Vienna devoted to Dürer’s genius – an event that marks only the ninth time that the painting has ever been displayed in public.

Story continues below

Young Hare – Albrecht Dürer (1502); one of Dürer’s most famous works – scholars have pondered how he managed to pose the animal

The reverberating gleam in the hare’s right eye, according to Christof Metzger, who curated the exhibition of more than 200 paintings, drawings and prints, is actually a reflection from inside Dürer’s studio, where the work was made – a magical touch that collapses the distance between observers of the masterpiece today and the bygone world that the artist inhabited half a millennium ago. “It’s really fascinating,” Metzger explained to BBC Culture about the most popular work in the Albertina Museum’s collection. “This animal materialises on paper in his workshop, and in the eye of the painted hare you can see his workshop’s window.”

ADVERTISEMENT

More like this:

- Félix Vallotton: A painter of disquiet and menace

- Picasso: The ultimate painter of war?

- Victor Vasarely: The art that tricks the eyes

Is it indeed ‘the glazing bars from the window in the painter’s studio’, as the accompanying catalogue describes it? That seems to be the scholarly consensus, though the stretched shape of the beguiling glisten is ambiguous, and conjures something more sacred: the tall parallel panes of painted glass that one finds in the high windows of a cathedral’s nave. Dürer’s decision to erase from the surface of his work any suggestion of the animal’s physical environment keeps its situation (and meaning) remarkably elastic. The shroud-like emptiness that surrounds the portrait transforms the marvel into something as mystical as it is material – a fiery figment of the imagination; a vision; a prayer.

Detail of Young Hare – Albrecht Dürer (1502); in the hare’s right eye, you can see the reflection of Dürer’s studio window

In the only other works by Dürer where hares figure – a woodcut from six years earlier, entitled The Holy Family with Three Hares (c1497), and an engraving created two years later, Adam and Eve (1504) – the animal finds itself entangled in overt religious symbolism. But here, the hare is free to fidget in the minds of those who encounter it – as teasingly evasive in spirit as it is fixed physically in pigment and paper.

Many of his works are really timeless – Christof MetzgerHow, exactly, Dürer managed to capture the skittish creature with such painstaking rigour – without the aid of taxidermy to hold the jittery jumper – still has bedevilled admirers of the work for centuries. A photographic memory? A steady, stewy diet of jugged hare? “I think with detail studies,” Metzger posits, when asked how he believes Dürer pulled it off: “studies of the hare in different positions: sitting, springing, from the side, from the front. Drawings like this are often the basis for his watercolours. He observed the living animal and then maybe when he makes the watercolour, the poor little hare is already in Dürer’s kitchen. We do not know.”

What we do know, what we can feel, is the indispensable power of the sublime glimmers that bedew the hare’s eye. Remove those subtle sparkles and the soul of the work would be snuffed out, its magic extinguished. Glimpsed through the gleam of the hare’s intense, almost otherworldly eye, and Dürer’s other masterworks bristle too with such invigorating details – seemingly slight chroniclings that are so astute, so meticulous, their truth transports us and makes us feel as if we are seeing the Earth we inhabit for the very first time. “Many of his works, and you can see this in the exhibition, are really timeless – “his landscapes, his studies of animals, of plants, of persons,” Metzger says. He’s such a brilliant observer of his world, of his context, on the one hand, and on the other hand such a brilliant artist in his ability to fix on paper what he has observed in nature, which is really fascinating and fantastic.”

A master of the natural world

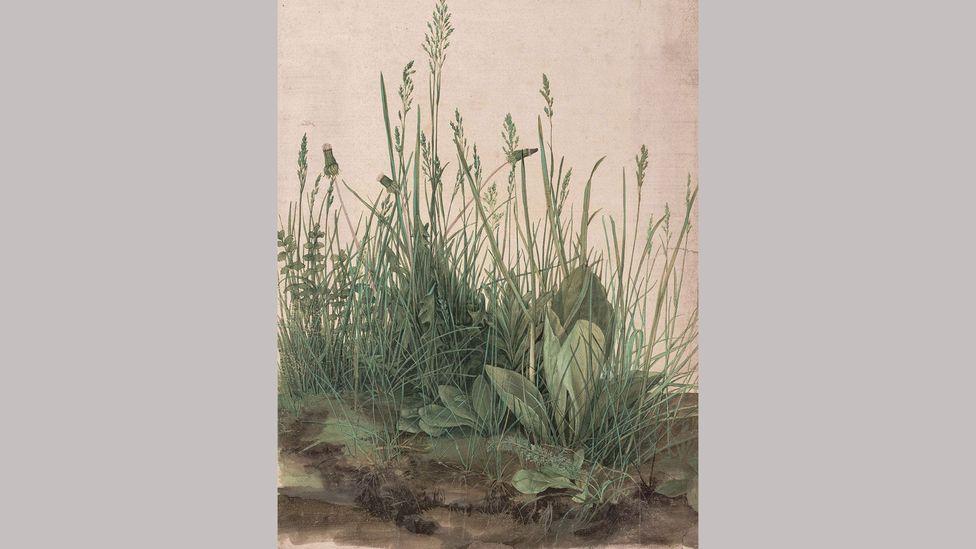

Frequently mentioned in the same breath as Young Hare is Dürer’s hypnotic study of a dishevelled scrap of seemingly random sward known simply as the Great Piece of Turf, a watercolour accented by pen-and-ink that the artist created the following year. His realistic articulation of every feathery fibre of cocks-foot, every soft serration of germander speedwell leaves, and the weightless sway of a sprawling tuft of Agrostis, or creeping bent, is truly breathtaking. Symphonic in its disorder, the study conjures from chaos a sense of organic rhythm undergirding all of life. What elevates the scene into the strangeness of a great work of art is its surreal suspension of plants to reveal below the soil-line the downward reach of their straggling roots, as if the patch of earth were levitating before us, ascending to heaven.

The Great Piece of Turf – Albrecht Dürer (1503); Dürer painted the sprawling roots of the grass, as well as what’s above ground

The Great Piece of Turf and the Young Hare both belong to the Albertina’s permanent collection, which forms the basis of the exhibition. “We have a very large and important collection,” Metzger tells BBC Culture, “and for works on paper, maybe the most important collection in the world.” Why now? “We thought it is time to show Dürer again after the last exhibition which took place in 2003. It’s always the right moment for an Albrecht Dürer show.”

Taking flight

The soaring majesty of uplifting colours is held in cruel check by the spectre of violence that ripped the wing from the bird’s torso

There is indeed something imperishably poignant and up-to-date about Dürer’s meticulous scrutiny of the natural world, which is now, in the light of anxieties surrounding climate change, as much a source of unease as wonder. The brutal beauty of his assiduous study Wing of a Blue Roller, a watercolour on vellum probably created a year or two before the Young Hare, is indicative of the artist’s unflinching eye. “The outspread wing takes up almost the entire surface of a nearly square sheet of parchment,” Metzger writes in the show’s catalogue, “and depicts every detail of its morphology with the highest degree of zoological accuracy: the reddish, cinnamon-coloured back plumage remaining near the tear, the secondary feathers in ultramarine, turquoise, pale green and off-white, as well as the primary feathers ranging in colour from white and azurite to bluish black.

“He even applied the finest of gold lines to his depiction of the dead animal’s breast plumage in order to imitate its iridescent lustre.”

Wing of a Blue Roller – Albrecht Dürer (c1500); here, the wing is disembodied from the bird, taking up almost an entire sheet of parchment

In art history, we’re rarely accustomed to seeing such resplendent plumage unless it is flapping spiritually from the shoulders of the Archangel Gabriel in depictions of the moment he informs the Virgin Mary that she will give birth to Christ, such as Fra Angelico’s celebrated fresco The Annunciation. But in Dürer’s work, the soaring majesty of uplifting colours is held in cruel check by the spectre of violence that ripped the wing from the bird’s torso, displacing the specimen to a decidedly secular context. Seen in the light of present-day unease about the damage humans are inflicting on the natural world, Dürer’s watercolour ruffles with prescient profundity.

Born in Nuremberg in 1471, Dürer rose to prominence in his 20s as a master of woodcut prints. Following stints studying in Colmar, Strasburg, Frankfurt and Venice (where he honed printmaking techniques), he returned to Nuremberg in 1495 and established his own workshop, where he quickly began to build a formidable reputation. The Albertina exhibition displays many of the finest works that Dürer created in the ensuing years, from collections around the world, including such masterworks as the Adoration of the Magi (on loan from the Uffizi), Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum), and Christ among the Doctors (from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid).

The Adoration of the Magi – Albrecht Dürer (1504); his reputation as an artist grew following the establishment of his own workshop in Nuremberg

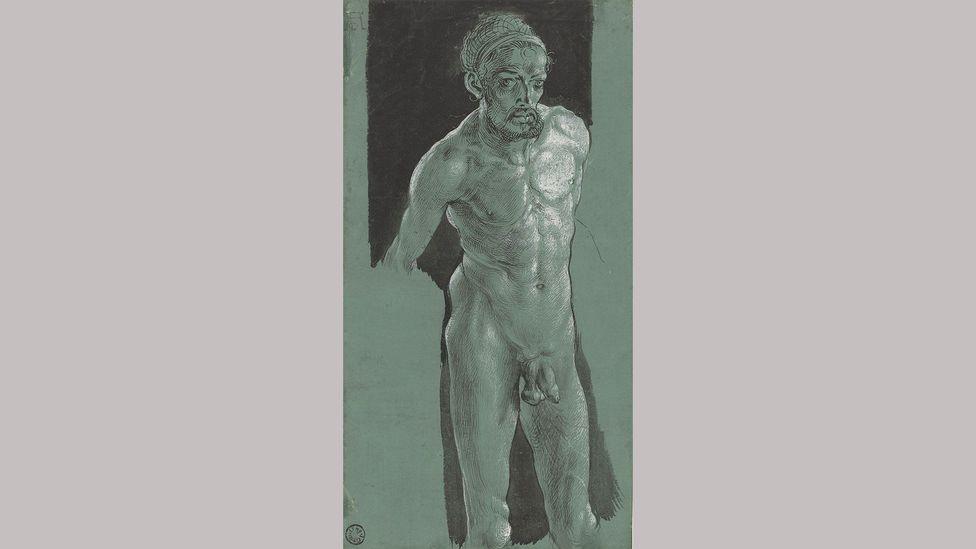

Are there any surprises? “We have a very interesting example in the exhibition,” Metzger says, “of a self-portrait as a nude.” He’s referring to a rather unsettling ink-and-whitelead drawing on green paper that shows the naked artist wearing only a hairnet, framed by an abstract field of self-abnegating black. “You see him from his legs up completely naked. We do not know how Dürer made this. With only a small mirror he constructed his naked body. His body is absolutely detailed in the way it’s observed and drawn, but it’s fragmented. The arms are missing. The legs are missing. It’s only the torso of his body.”

Nude Self-Portrait – Albrecht Dürer (c1499); it’s unclear how Dürer created this self-portrait, as he only had a small mirror

Yet it is the work’s very disjointedness that paradoxically pulls it together into something pulsing and intense. Dürer’s ability to spin into existence from an almost miserly economy of strokes “a person filled with life whom you can meet on the street 10 minutes later”, as Metzger puts it, is exhilarating. “In my opinion, the exhibition is really a once-in-a-lifetime possibility. We are really trying to give an impression of his whole cosmos.” Through Dürer’s fastidious eye we find ourselves transported to another reality – a world we never knew we knew.

Albrecht Dürer is at Vienna’s Albertina Museum until 6 January 2020.

Was Albrecht Dürer a Genius? An Idiosyncratic New Book Searches for Answers

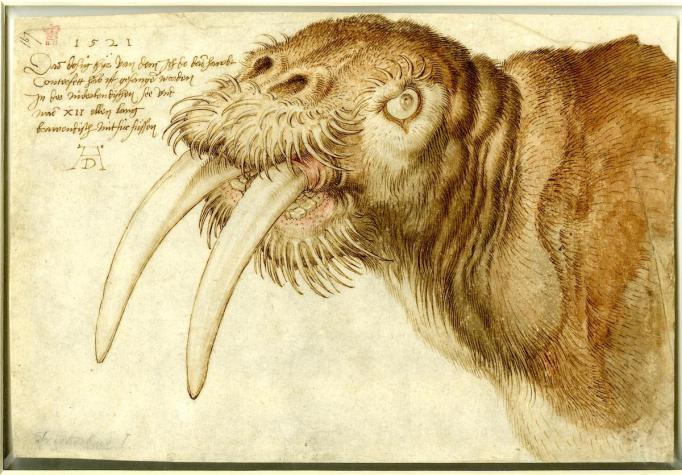

In Albert and the Whale, Philip Hoare seeks to understand how Albrecht Dürer created such detailed images of animals, including this 1521 drawing of a walrus. ©The Trustees of the British Museum

It is a sad fact that artists’ lives are often nowhere near as interesting as their work. That’s because, in some ways, they’re just like the rest of us. Even the most talented biographers find themselves beleaguered in the face of an artistic giant like, say, Albrecht Dürer, perhaps the most famous artist of the Northern Renaissance. A case in point: In 1913, when critic Robert Fry edited Dürer’s journals, he thought he would obtain grand insights into Dürer’s art. Instead, he found something like a bland travelogue. He discovered that Dürer traded a print for dried fishes and coral, as well as some other trinkets, and that he once gave a prince some engravings in exchange for a coconut, two parrots, a fur coat, and more. He also learned that Dürer bought a pair of socks.

Related Articles

The tale of Fry’s disappointment is included in Albert and the Whale: Albrecht Dürer and How Art Imagines Our World (Pegasus), a new book by Philip Hoare. Hoare did not set out to write out a biography of Dürer, though he probably could have, given that he penned the definitive tome about the life of playwright Noël Coward back in 1995. Instead, Hoare offers up a text that is something closer to a book of essays. Its focus is less on the Renaissance artist than on his continued allure today. Why, Hoare wonders, do we still care about an artist who lived and died centuries ago? Was Dürer a genius, and does that matter, anyway?

The central event in this fascinating book involves a missed connection between Dürer and a dead whale. In 1520, while attempting to run away from a plague that was sweeping through Europe, Dürer set sail for the Netherlands’ Zeeland region, where he was told there was a beached whale washed ashore. Dürer had a knack for etching almost impossibly detailed images of animals—he was exceptionally good at lending them the kind of psychology typically only afforded to humans in portraits at the time—and so he simply had to see the creature for himself. Dürer’s ship just barely made it there in one piece, and the artist caught malaria in the process. When he got there, he never even saw the whale—the canals were covered in an ooze that made them impassable, so he never got to see the maritime beast.

“Dürer’s own abortive, amphibious expedition would shorten his life, from a condition he couldn’t name, because of an animal he didn’t see,” Hoare writes. And yet, good art resulted: Dürer developed a fascination with sea creatures, and he wound up making work about them. In 1521, for one pen drawing now in the British Museum’s collection, Dürer made an image of a walrus, its skin flecked with spiky-looking hairs. The walrus appears to seethe with rage—its eyes seem to pop out of its skull. The image is so exacting that it’s hard to believe that historians don’t even know for sure that Dürer ever saw a walrus up close.

Mulling a skeleton of a walrus, Hoare marvels at Dürer’s abilities. “We cannot capture living, quivering creatures, their flesh and bone, tusks and fur, instincts and apprehensions,” he writes. “Yet Dürer got close, even when he didn’t see the real thing.”

Courtesy Pegasus Books

Hoare is hardly alone in finding himself awed by Dürer’s craft. A range of figures throughout history have similarly fallen under the artist’s spell, from the writer Herman Melville (who himself created the ultimate artwork about whales, Moby-Dick) to the essayist W. G. Sebald, whose influence on Albert and the Whale is palpable.

A lengthy digression focused on the life of novelist Thomas Mann forms the book’s centerpiece. Mann was also a big Dürer fan, as Hoare continuously points out—his novels are laced with allusions to the artist. The protagonist of Mann’s 1943 novel Doctor Faustus, a doctor named Adrian Leverkühn, has a passion for Dürer, and at one point in Mann’s revision of the Faust tale, Adrian begins to look disheveled, growing a beard. Hoare claims this is an allusion to Dürer’s own 1500 self-portrait, in which the artist’s piercing gaze meets the viewer’s. “He has become Dürer,” Hoare writes.

Albert and the Whale nearly spins out of control as Hoare delves into the history of Marianne Moore, an eccentric poet who loved Dürer and who, like the artist, found herself entranced when standing before monumental creatures hauled out of the ocean and onto land. But the story snaps back into place in its own idiosyncratic way.

This is a whirlwind book, filled with people, places, and things that are often deliberately left blurry. The text is dotted with images without captions to identify them, and the prose is interspersed with unmarked quotations from writings of all kinds. (For those unwilling to surrender to the book’s controlled chaos, there’s a source list on Hoare’s website.) It’s all a bit confounding—but it has a mesmerizing effect.

Toward the end of Albert and the Whale, Hoare finds himself in a Vienna library, holding a small piece of glass that contains what may be a wisp of Dürer’s hair. “I’m holding Dürer,” Hoare remarks. A 1550 note from a merchant certifies that this is Dürer’s hair, though for all we know it could just as well belong to anyone. Hoare seems convinced, however, and he’s concocted a whole story in his head about how valuable it is. “Dürer was raised on relics,” he writes. “Now he is one.”