Compare and contrast two works from two different movements in this module: realism, Romanticism, Impressionism, NeoClassicism or another that you are interested in. Think about these artists in relat

European and American Art in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Top of Form

Search for:

Bottom of Form

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism refers to movements in the arts that draw inspiration from the “classical” art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome.

Learning Objectives

Identify attributes of Neoclassicism and some of its key figures

Key Takeaways

Key Points

The height of Neoclassicism coincided with the 18th century Enlightenment era, and continued into the early 19th century.

With the increasing popularity of the Grand Tour, it became fashionable to collect antiquities as souvenirs, which spread the Neoclassical style through Europe and America.

Neoclassicism spanned all of the arts including painting, sculpture, the decorative arts, theatre, literature, music, and architecture.

Generally speaking, Neoclassicism is defined stylistically by its use of straight lines, minimal use of color, simplicity of form and, of course, an adherence to classical values and techniques.

Rococo, with its emphasis on asymmetry, bright colors, and ornamentation is typically considered to be the direct opposite of the Neoclassical style.

Key Terms

Grand Tour: The traditional tour of Europe undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men of means. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transit in the 1840s.

Enlightenment: A concept in spirituality, philosophy, and psychology related to achieving clarity of perception, reason, and knowledge.

Rococo: A style of baroque architecture and decorative art, from 18th century France, having elaborate ornamentation.

The classical revival, also known as Neoclassicism, refers to movements in the arts that draw inspiration from the “classical” art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. The height of Neoclassicism coincided with the 18th century Enlightenment era, and continued into the early 19th century. The dominant styles during the 18th century were Baroque and Rococo. The latter, with its emphasis on asymmetry, bright colors, and ornamentation is typically considered to be the direct opposite of the Neoclassical style, which is based on order, symmetry, and simplicity. With the increasing popularity of the Grand Tour, it became fashionable to collect antiquities as souvenirs. This tradition of collecting laid the foundations for many great art collections and spread the classical revival throughout Europe and America.

Neoclassicism grew to encompass all of the arts, including painting, sculpture, the decorative arts, theatre, literature, music, and architecture. The style can generally be identified by its use of straight lines, minimal use of color, simplicity of form and, of course, its adherence to classical values and techniques.

In music, the period saw the rise of classical music and in painting, the works of Jaques-Louis David became synonymous with the classical revival. However, Neoclassicism was felt most strongly in architecture, sculpture, and the decorative arts, where classical models in the same medium were fairly numerous and accessible. Sculpture in particular had a great wealth of ancient models from which to learn, however, most were Roman copies of Greek originals.

Rinaldo Rinaldi, Chirone Insegna Ad Achille a Suonare La Cetra: Executed in a classical style and adhering to classical themes, this sculpture is a typical example of the Neoclassical style.

Neoclassical architecture was modeled after the classical style and, as with other art forms, was in many ways a reaction against the exuberant Rococo style. The architecture of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio became very popular in the mid 18th century. Additionally, archaeological ruins found in Pompeii and Herculaneum informed many of the stylistic values of Neoclassical interior design based on the ancient Roman rediscoveries.

Villa Godi Valmarana, Lonedo di Lugo, Veneto, Italy: Villa Godi was one of the first works by Palladio. Its austere facade, arched doorways and minimal symmetry reflect his adherence to classical stylistic values.

Neoclassical Paintings

Neoclassical painting, produced by men and women, drew its inspiration from the classical art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the overarching themes present in Neoclassical painting

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Neoclassical subject matter draws from the history and general culture of ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. It is often described as a reaction to the lighthearted and “frivolous” subject matter of the Rococo.

Neoclassical painting is characterized by the use of straight lines, a smooth paint surface, the depiction of light, a minimal use of color, and the clear, crisp definition of forms.

The works of Jacques-Louis David are usually hailed as the epitome of Neoclassical painting.

David attracted over 300 students to his studio, including Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Marie-Guillemine Benoist, and Angélique Mongez, the last of whom tried to extend the Neoclassical tradition beyond her teacher’s death.

Key Terms

Enlightenment: A philosophical movement in 17th and 18th century Europe. Also known as the Age of Reason, this was an era that emphasized rationalism.

Background and Characteristics

Neoclassicism is the term for movements in the arts that draw inspiration from the classical art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. The height of Neoclassicism coincided with the 18th century Enlightenment era and continued into the early 19th century. With the advent of the Grand Tour—a much enjoyed trip around Europe intended to introduce young men to the extended culture and people of their world—it became fashionable to collect antiquities as souvenirs. This tradition laid the foundations of many great collections and ensured the spread of the Neoclassical revival throughout Europe and America. The French Neoclassical style would greatly contribute to the monumentalism of the French Revolution, with the emphasis of both lying in virtue and patriotism.

Neoclassical painting is characterized by the use of straight lines, a smooth paint surface hiding brush work, the depiction of light, a minimal use of color, and the clear, crisp definition of forms. Its subject matter usually relates to either Greco-Roman history or other cultural attributes, such as allegory and virtue. The softness of paint application and light-hearted and “frivolous” subject matter that characterize Rococo painting is recognized as the opposite of the Neoclassical style. The works of Jacques-Louis David are widely considered to be the epitome of Neoclassical painting. Many painters combined aspects of Romanticism with a vaguely Neoclassical style before David’s success, but these works did not strike any chords with audiences. Typically, the subject matter of Neoclassical painting consisted of the depiction of events from history, mythological scenes, and the architecture and ruins of ancient Rome.

The School of David

Neoclassical painting gained new momentum with the great success of David’s Oath of the Horatii at the Paris Salon of 1785. The painting had been commissioned by the royal government and was created in a style that was the perfect combination of idealized structure and dramatic effect. The painting created an uproar, and David was proclaimed to have perfectly defined the Neoclassical taste in his painting style. He thereby became the quintessential painter of the movement. In The Oath of the Horatii, the perspective is perpendicular to the picture plane. It is defined by a dark arcade behind several classical heroic figures. There is an element of theatre, or staging, that evokes the grandeur of opera. David soon became the leading French painter and enjoyed a great deal of government patronage. Over the course of his long career, he attracted over 300 students to his studio.

Jacques-Louis David. The Oath of the Horatii (1784): Oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a Neoclassical painter of history and portraiture, was one of David’s students. Deeply devoted to classical techniques, Ingres is known to have believed himself to be a conservator of the style of the ancient masters, although he later painted subjects in the Romantic style. Examples of his Neoclassical work include the paintings Virgil Reading to Augustus (1812), and Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864). Both David and Ingres made use of the highly organized imagery, straight lines, and clearly defined forms that were typical of Neoclassical painting during the 18th century.

Virgil Reading to Augustus by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1812): Oil on canvas. The Walters Art Museum.

While tradition and the rules governing the Académie Française barred women from studying from the nude model (a necessity for executing an effective Neoclassical painting), David believed that women were capable of producing successful art of the style and welcomed many as his students. Among the most successful were Marie-Guillemine Benoist, who eventually won commissions from the Bonaparte family, and Angélique Mongez, who won patrons from as far away as Russia.

Self-Portrait by Marie-Guillemine Benoist (1788): In this untraced oil on canvas, Benoist (then Leroulx de la Ville) paints a section from David’s acclaimed Neoclassical painting of Justinian’s blinded general Belisarius begging for alms. Her return of the viewer’s gaze and classical attire show her confidence as an artist and conformity to artistic trends.

Mongez is best known for being one of the few women to paint monumental subjects that often included the male nude, a feat for which hostile critics often attacked her.

Theseus and Pirithoüs Clearing the Earth of Brigands, Deliver Two Women from the Hands of Their Abductors by Angélique Mongez (1806): Oil on canvas. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Mongez and Antoine-Jean Gros, another of David’s students, tried to carry on the Neoclassical tradition after David’s death in 1825 but were unsuccessful in face of the growing popularity of Romanticism.

Neoclassical Sculpture

A reaction against the “frivolity” of the Rococo, Neoclassical sculpture depicts serious subjects influenced by the ancient Greek and Roman past.

Learning Objectives

Explain what motifs are common to Neoclassical sculpture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Neoclassicism emerged in the second half of the 18th century, following the excavations of the ruins of Pompeii, which sparked renewed interest in the Graeco-Roman world.

Neoclassical sculpture is defined by its symmetry, life-sized to monumental scale, and its serious subject matter.

The subjects of Neoclassical sculpture ranged from mythological figures to heroes of the past to major contemporary personages.

![Compare and contrast two works from two different movements in this module: realism, Romanticism, Impressionism, NeoClassicism or another that you are interested in. Think about these artists in relat 7]()

Neoclassical sculpture could capture its subject as either idealized or in a more veristic manner.

Key Terms

verism: An ancient Roman technique, in which the subject is depicted with “warts and all” realism.

As with painting, Neoclassicism made its way into sculpture in the second half of the 18th century. In addition to the ideals of the Enlightenment, the excavations of the ruins at Pompeii began to spark a renewed interest in classical culture. Whereas Rococo sculpture consisted of small-scale asymmetrical objects focusing on themes of love and gaiety, neoclassical sculpture assumed life-size to monumental scale and focused on themes of heroism, patriotism, and virtue.

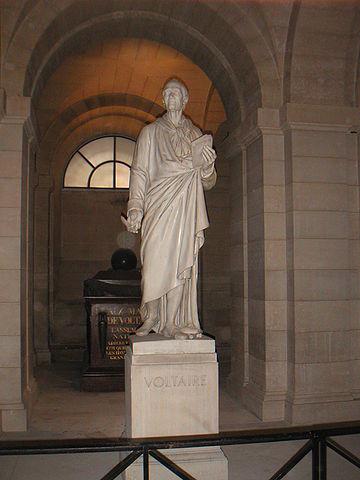

In his tomb sculpture, the Enlightenment philosophe Voltaire is honored in true Neoclassical form. In a style influenced by ancient Roman verism, he appears as an elderly man to honor his wisdom. He wears a contemporary commoner’s blouse to convey his humbleness, and his robe assumes the appearance of an ancient Roman toga from a distance. Like his ancient predecessors, his facial expression and his body language suggest an air of scholarly seriousness.

Voltaire’s tomb.: Panthéon, Paris.

Neoclassical sculptors benefited from an abundance of ancient models, albeit Roman copies of Greek bronzes in most cases. The leading Neoclassical sculptors enjoyed much acclaim during their lifetimes. One of them was Jean-Antoine Houdon, whose work was mainly portraits, very often as busts, which do not sacrifice a strong impression of the sitter’s personality to idealism. His style became more classical as his long career continued, and represents a rather smooth progression from Rococo charm to classical dignity. Unlike some Neoclassical sculptors he did not insist on his sitters wearing Roman dress, or being unclothed. He portrayed most of the great figures of the Enlightenment, and traveled to America to produce a statue of George Washington, as well as busts of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and other luminaries of the new republic. His portrait bust of Washington depicts the first President of the United States as a stern, yet competent leader, with the influence of Roman verism evident in his wrinkled forehead, receding hairline, and double chin.

Bust of George Washington by Jean-Antoine Houdon (c. 1786)

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

The Italian artist Antonio Canova and the Danish artist Bertel Thorvaldsen were both based in Rome, and as well as portraits produced many ambitious life-size figures and groups. Both represented the strongly idealizing tendency in Neoclassical sculpture.

Hebe by Antonio Canova (1800–05).: Hermitage State Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Canova has a lightness and grace, where Thorvaldsen is more severe. The difference is exemplified in Canova’s Hebe (1800–05), whose contrapposto almost mimics lively dance steps as she prepares to pour nectar and ambrosia from a small amphora into a chalice, and Thorvaldsen’s Monument to Copernicus (1822-30), whose subject sits upright with a compass and armillary sphere.

Monument to Copernicus by Bertel Thorvaldsen (1822–30).: Bronze. Warsaw, Poland.

Neoclassical Architecture

Neoclassical architecture looks to the classical past of the Graeco-Roman era, the Renaissance, and classicized Baroque to convey a new era based on Enlightenment principles.

Learning Objectives

Identify what sets Neoclassical architecture apart from other

movements

Key Takeaways

Key Points

Neoclassical architecture was produced by the Neoclassical movement in the mid 18th century. It manifested in its details as a reaction against the Rococo style of naturalistic ornament, and in its architectural formulas as an outgrowth of the classicizing features of Late Baroque.

The first phase of Neoclassicism in France is expressed in the “Louis XVI style” of architects like Ange-Jacques Gabriel (Petit Trianon, 1762–68) while the second phase is expressed in the late 18th-century Directoire style.

Neoclassical architecture emphasizes its planar qualities, rather than sculptural volumes. Projections and recessions and their effects of light and shade are more flat, while sculptural bas- reliefs are flatter and tend to be enframed in friezes, tablets, or panels.

Structures such as the Arc de Triomphe, the Panthéon in Paris, and Chiswick House in London have elements that convey the influence of ancient Greek and Roman architecture, as well as some influence from the Renaissance and Late Baroque periods.

Neoclassical architecture, which began in the mid 18th century, looks to the classical past of the Graeco-Roman era, the Renaissance, and classicized Baroque to convey a new era based on Enlightenment principles. This movement manifested in its details as a reaction against the Rococo style of naturalistic ornament, and in its architectural formulas as an outgrowth of some classicizing features of Late Baroque. In its purest form, Neoclassicism is a style principally derived from the architecture of Classical Greece and Rome. In form, Neoclassical architecture emphasizes the wall and maintains separate identities to each of its parts.

The first phase of Neoclassicism in France is expressed in the Louis XVI style of architects like Ange-Jacques Gabriel (Petit Trianon, 1762–68). Ange-Jacques Gabriel was the Premier Architecte at Versailles, and his Neoclassical designs for the royal palace dominated mid 18th century French architecture.

Ange-Jacques Gabriel. Château of the Petit Trianon.: The Petit Trianon in the park at Versailles demonstrates the neoclassical architectural style under Louis XVI.

After the French Revolution, the second phase of Neoclassicism was expressed in the late 18th century Directoire style. The Directoire style reflected the Revolutionary belief in the values of republican Rome. This style was a period in the decorative arts, fashion, and especially furniture design, concurrent with the post-Revolution French Directoire (November 2, 1795–November 10, 1799). The style uses Neoclassical architectural forms, minimal carving, planar expanses of highly grained veneers, and applied decorative painting. The Directoire style was primarily established by the architects and designers Charles Percier (1764–1838) and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1762–1853), who collaborated on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, which is considered emblematic of French neoclassical architecture.

Arc de Triomphe: The Arc de Triomphe, although finished in the early 19th century, is emblematic of French neoclassical architecture that dominated the Directoire period.

Though Neoclassical architecture employs the same classical vocabulary as Late Baroque architecture, it tends to emphasize its planar qualities rather than its sculptural volumes. Projections, recessions, and their effects on light and shade are more flat. Sculptural bas-reliefs are flatter and tend to be framed in friezes, tablets, or panels. Its clearly articulated individual features are isolated rather than interpenetrating, autonomous, and complete in themselves.

Even sacred architecture was classicized during the Neoclassical period. The Panthéon, located in the Latin Quarter of Paris, was originally built as a church dedicated to St. Geneviève and to house the reliquary châsse containing her relics. However, during the French Revolution, the Panthéon was secularized and became the resting place of Enlightenment icons such as Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Designer Jacques-Germain Soufflot had the intention of combining the lightness and brightness of the Gothic cathedral with classical principles, but its role as a mausoleum required the great Gothic windows to be blocked. In 1780, Soufflot died and was replaced by his student, Jean-Baptiste Rondelet.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot (original architect) and Jean-Baptiste Rondelet. The Panthéon.: Begun 1758, completed 1790.

Similar to a Roman temple, the Panthéon is entered through a portico that consists of three rows of columns (in this case, Corinthian) topped by a Classical pediment. In a fashion more closely related to ancient Greece, the pediment is adorned with reliefs throughout the triangular space. Beneath the pediment, the inscription on the entablature translates as: “To the great men, the grateful homeland.” The dome, on the other hand, is more influenced by Renaissance and Baroque predecessors, such as St. Peter’s in Rome and St. Paul’s in London.

Intellectually, Neoclassicism was symptomatic of a desire to return to the perceived “purity” of the arts of Rome. The movement was also inspired by a more vague perception (“ideal”) of Ancient Greek arts and, to a lesser extent, 16th century Renaissance Classicism, which was also a source for academic Late Baroque architecture. There is an anti-Rococo strain that can be detected in some European architecture of the earlier 18th century. This strain is most vividly represented in the Palladian architecture of Georgian Britain and Ireland.

Lord Burlington. Chiswick House: The design of Chiswick House in West London was influenced by that of Palladio’s domestic architecture, particularly the Villa Rotunda in Venice. The stepped dome and temple façade were clearly influenced by the Roman Pantheon.

The trend toward the classical is also recognizable in the classicizing vein of Late Baroque architecture in Paris. It is a robust architecture of self-restraint, academically selective now of “the best” Roman models. These models were increasingly available for close study through the medium of architectural engravings of measured drawings of surviving Roman architecture.

French Neoclassicism continued to be a major force in academic art through the 19th century and beyond—a constant antithesis to Romanticism or Gothic revivals.

A gentleman architectIn an undated note, Thomas Jefferson left clear instructions about what he wanted engraved upon his burial marker:

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

Father of the University of Virginia

Jefferson explained, “because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.” To be certain, there are important achievements Jefferson neglected. He was also the Governor of Virginia, American minister to France, the first Secretary of State, the third president of the United States, and one of the most accomplished gentleman architects in American history. To quote William Pierson, an architectural historian, “In spite of the fact that his training and resources were those of an amateur, he was able to perform with all the insight and boldness of a high professional.”

Indeed, even had he never entered political life, Jefferson would be remembered today as one of the earliest proponents of neoclassical architecture in the United States. Jefferson believed art was a powerful tool; it could elicit social change, could inspire the public to seek education, and could bring about a general sense of enlightenment for the American public. If Cicero believed that the goals of a skilled orator were to Teach, to Delight, and To Move, Jefferson believed that the scale and public nature of architecture could fulfill these same aspirations.

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello (view from the north), Charlottesville, Virginia, 1770-1806

Return to the classicalJefferson arrived at the College of William and Mary in 1760 and took an immediate interest in the architecture of the college’s campus and of Williamsburg more broadly. A lifelong book lover, Jefferson began his architectural collection while a student. His first two purchases were James Leoni’s The Architecture of A. Palladio (1715-1720) and James Gibbs’ Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732).

Although never formally trained as an architect, Jefferson, both while a student and then later in life, expressed dissatisfaction with the architecture that surrounded him in Williamsburg, believing that the Wren-Baroque aesthetic common in colonial Virginia was too British for a North American audience. In an oft-quoted passage from Notes on Virginia (1782), Jefferson critically wrote of the architecture of Williamsburg:

“The College and Hospital are rude, mis-shapen piles, which, but that they have roofs, would be taken for brick-kilns. There are no other public buildings but churches and court-houses, in which no attempts are made at elegance.”

Thus, when Jefferson began to design his own home, he turned not to the architecture then in vogue around the Williamsburg area, but instead to the classically inspired architecture of Antonio Palladio and James Gibbs. Rather than place his plantation house along the bank of a river—as was the norm for Virginia’s landed gentry during the eighteenth century—Jefferson decided instead to place his home, which he named Monticello (Italian for “little mountain”) atop a solitary hill just outside Charlottesville, Virginia.

French Neo-Classicism for an American audienceConstruction began in 1768 when the hilltop was first cleared and leveled, and Jefferson moved into the completed South Pavilion two years later. The early phase of Monticello’s construction was largely completed by 1771. Jefferson left both Monticello and the United States in 1784 when he accepted an appointment as America Minister to France. Over the next five years, that is, until September 1789 when Jefferson returned to the United States to serve as Secretary of State under newly elected President Washington, Jefferson had the opportunity to visit Classical and Neoclassical architecture in France.

Thomas Jefferson, Rotunda, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1819-26

This time abroad had an enormous effect on Jefferson’s architectural designs. The Virginia State Capitol (1785-1789) is a modified version of the Maison Carrée (16 B.C.E.), a Roman temple Jefferson saw during a visit to Nîmes, France. And although Jefferson never went so far as Rome, the influence that the Pantheon (125 C.E.) had over his Rotunda (begun 1817) at the University of Virginia is so evident it hardly need be mentioned.

Politics largely consumed Jefferson from his return to the United States until the last day of 1793 when he formally resigned from Washington’s cabinet. From this year until 1809, Jefferson diligently redesigned and rebuilt his home, creating in time one of the most recognized private homes in the history of the United States. In it, Jefferson fully integrated the ideals of French neoclassical architecture for an American audience.

In this later construction period, Jefferson fundamentally changed the proportions of Monticello. If the early construction gave the impression of a Palladian two-story pavilion, Jefferson’s later remodeling, based in part on the Hôtel de Salm (1782-87) in Paris, gives the impression of a symmetrical single-story brick home under an austere Doric entablature. The west garden façade—the view that is once again featured on the American nickel—shows Monticello’s most recognized architectural features. The two-column deep extended portico contains Doric columns that support a triangular pediment that is decorated by a semicircular window. Although the short octagonal drum and shallow dome provide Monticello a sense of verticality, the wooden balustrade that circles the roofline provides a powerful sense of horizontality. From the bottom of the building to its top, Monticello is a striking example of French Neoclassical architecture in the United States.

Rembrandt Peale, Thomas Jefferson, 1805, oil on linen, 28 x 23 1/2″ (New-York Historical Society)

Jefferson changed political parties and was a Democratic-Republican by the time he was elected president. He believed the young United States needed to forge a strong diplomatic relationship with France, a country Jefferson and his political brethren believed were our revolutionary brothers in arms. With this in mind, it is unsurprising that Jefferson designed his own home after the neoclassicism then popular in France, a mode of architecture that was distinct from the style then fashionable in Great Britain. This neoclassicism—with roots in the architecture of ancient Rome—was something Jefferson was able to visit while abroad.

Buildings that speak to democratic idealsBy helping to introduce classical architecture to the United States, Jefferson intended to reinforce the ideals behind the classical past: democracy, education, rationality, civic responsibility. Because he detested the English, Jefferson continually rejected British architectural precedents for those from France. In doing so, Jefferson reinforced the symbolic nature of architecture. Jefferson did not just design a building; he designed a building that eloquently spoke to the democratic ideals of the United States. This is clearly seen in the Virginia State Capitol, in the Rotunda at the University of Virginia, and especially in his own home, Monticello.

It is impossible to express the beauty [of the camera obscura image] in words. The art of painting is dead, for this is life itself: or something higher, if we could find a word for it.

— Constantijn Huygens, private letter April 13, 1622

Vermeer & the Camera

Obscura

Function & history

Rediscovery & evidence

The camera's limitations & Vermeer camera

Camera obscura resources

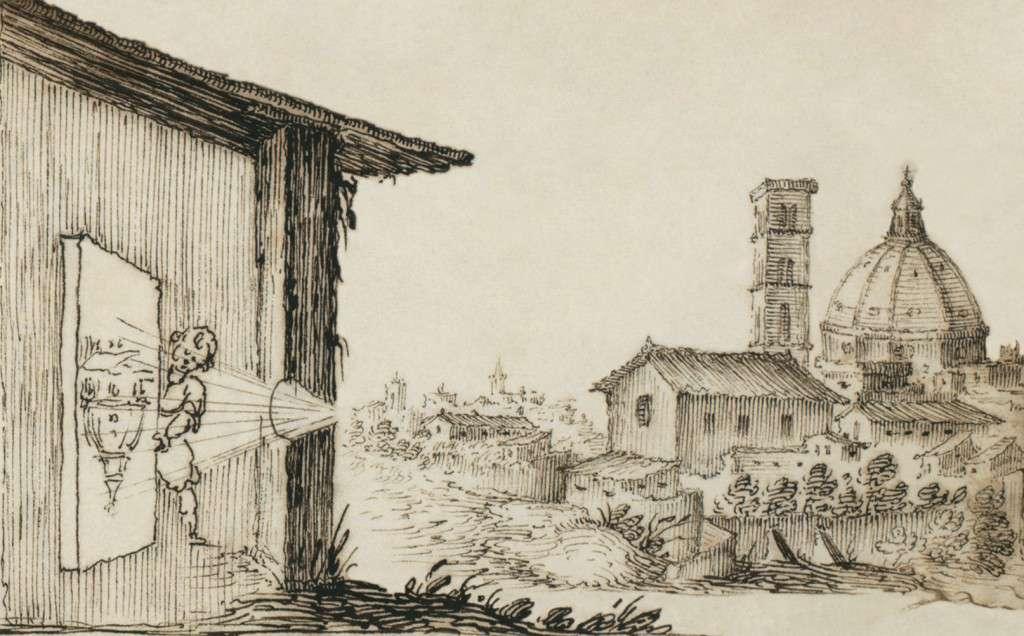

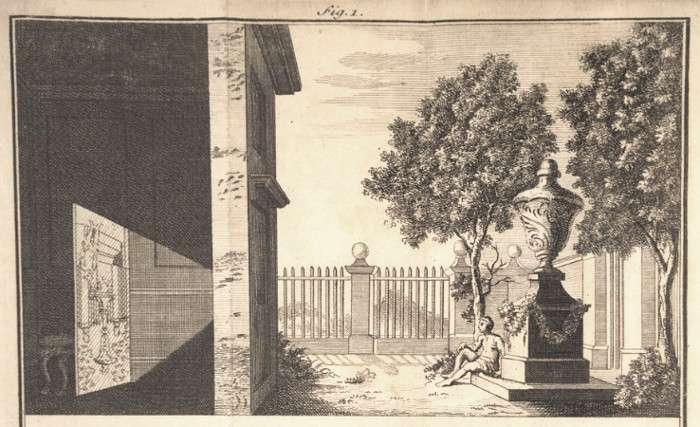

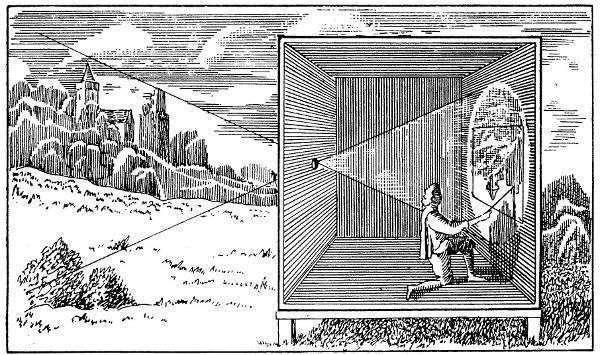

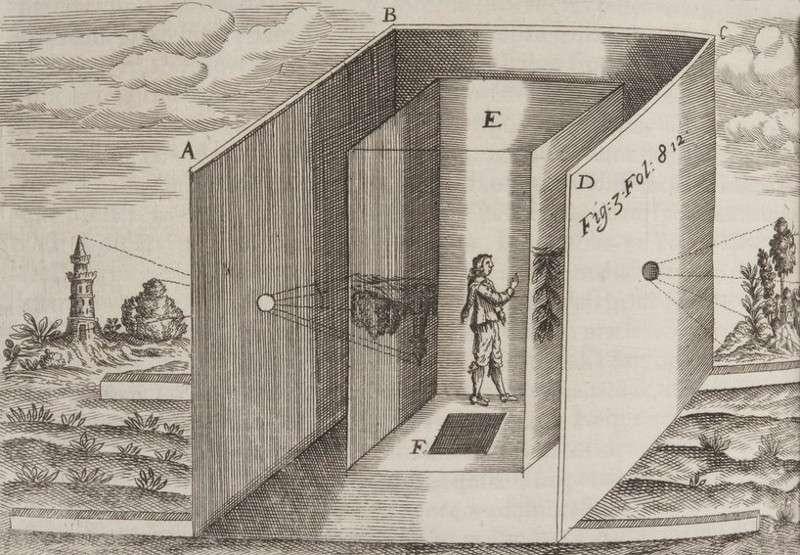

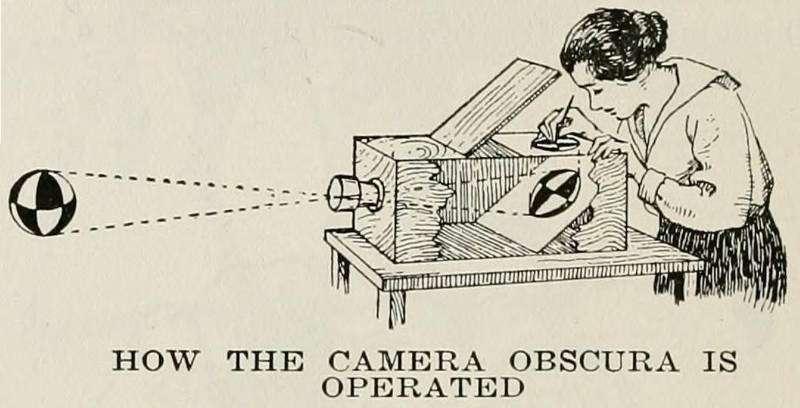

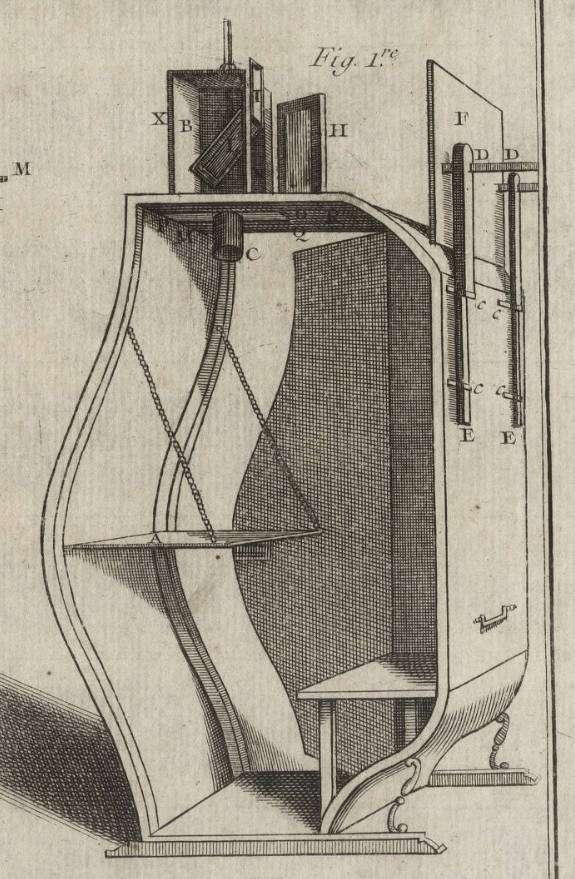

"The principle of the camera obscura is as simple as it seems magical even today. In a camera obscura the rays of light from an observed scene pass through a small aperture in one side of a closed room in such a way (following the laws of optics) as to cross and re-emerge on the other side of the aperture in a divergent configuration (fig. 1 & 2)." 1 The surroundings of the projected image must be dark for the image to be clear, so the first historical camera obscura experiments were performed in dark rooms with a small hole bored into one of its walls (fig. 3 & 4). In later years the room was transformed into a large, portable box (fig. 5 & 6) and later into small boxes that could be carried under ones arms. (fig. 12, 16, 18 & 21). As will become abundantly clear, there are two types of camera obscura: the camera with an internal observer, which can be either stationary or mobile, and the camera obscura with an external observer, which is always mobile.

fig. 1 Principle of the pin-hole camera obscura in Ars magna lucis et umbrae. (p. 121)

Athanasius Kircher

1646

fig. 2

fig. 3 Illustration of camera obscura from "Sketchbook on military art, including geometry, fortifications, artillery, mechanics, and pyrotechnics" (The background shows Brunelleschi's Duomo, Florence.)

Unknown, possibly Italian

Seventeenth century

Pen and ink on paper

Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

fig. 4 The camera obscura principle as illustrated in: A short account of the eye and nature of vision. Chiefly designed to illustrate the use and advantage of spectacles. Wherein are laid down rules for chusing glasses proper for remedying all the different defects of sight. As also some reasons for preferring a particular kind of glass, fitter than any other made use of for that purpose.

fig. 4 The camera obscura principle as illustrated in: A short account of the eye and nature of vision. Chiefly designed to illustrate the use and advantage of spectacles. Wherein are laid down rules for chusing glasses proper for remedying all the different defects of sight. As also some reasons for preferring a particular kind of glass, fitter than any other made use of for that purpose.

James Ayscough

1755

Printed by E Say for A Strahan, 1755

London

fig. 5 Illustration from A New and Complete Dictionary of the Arts and Sciences

Thomas Jeffreys

1754

London: Printed for W. Owen

fig. 6 Engraving of a "portable" camera obscura in Athanasius Kircher's Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae (1645)

The image of the camera obscura has particular properties which makes it quite different from both reality and the photograph: its image is projected upside down, reversed left to right, and its luminosity is very low. A person entering the darkened room must wait a few minutes for his eyes to become accustomed before he can make sense out the projected image. The first phenomenon is due to the laws of optics while the second is due to the necessarily reduced size of the camera’s aperture.

The discovery and development of camera obscura stands at the crossroads of astronomy, perspective, optics, philosophy,2 magic and art. Those who were initially interested in the device were not only scientists (natural philosophers) but philosophers or inventors—but, until the mid-1600s, as far as we know, never practicing artists.

It is impossible to know by whom or when the camera obscura was first theorized. Almost certainly the device itself "was formulized from optical principles that had been accidentally discovered centuries earlier and that are as old as light itself. In the fifth century B.C., the Chinese philosopher Mo Ti noted the 'image-making properties' of a small aperture, although it was not instrumentalized. A century later, Aristotle (384–322 BC) was struck by the many crescent-shaped images of the sun that appeared on the ground beneath a tree during an eclipse of the sun, and attributed them to the small spaces between the leaves."3 Those who has lived for some time in Italy in a house fitted with the typical slatted persiane (shutters) might have experienced the effect of a camera obscura by accident, particularly during the summer months when sun shines all day long. When the shutters are almost closed, every once in a while the direction of the sun rays and particular dispositions of the slats fortuitously create a tiny aperture that functions as a pinhole allowing the person inside the dark room to see part of the landscape outside the window projected on the floor or a wall.

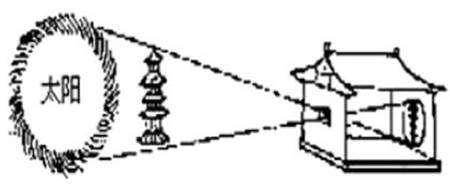

fig. 8 Image of a pin-hole camera obscura with the Chinese characters that translate as "sun."

Jing jing ling chi

Zheng Fu-Guang zhu

In the third century B. C., Chinese writer Tuan Cheng-Shih discussed an inverted pagoda that he had seen form through a small hole made in a screen, although he attributed it to reflections in the nearby sea rather than a result of optics. In 1086–1088, the Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty Shen Kua (1031–1095), correctly explained the principles of the camera obscura—the focal point, the role of the pinhole and inverted images—using a fitting metaphor of an oar and its oarlock. He compared a ray of light to an oar in its oarlock (pinhole): when the handle is up, the blade of the oar is down, and vice versa. The property of image inversion was later illustrated using the canonical image of a pagoda (fig. 8) in the book Jing jing ling chi (Optical and Other Comments) by Zheng Fu-Guang zhu (1780–1853).

In 1038 A.D., the great Arab scholar Al-Hassan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinized as Alhazen; 965–c. 1040) described a working model of the camera obscura in his Perspectiva (i.e., the thirteenth-century Latin translation of his Kitãb al-ma). Alhazen did not actually construct the device because he and his followers were interested in the camera for what it revealed about the behavior of light, not for purposes of representation. He wrote:

If the image of the sun at the time of an eclipse—provided it is not a total one—passes through a small round hole onto a plane surface, opposite, it will be crescent-shaped… If the hole is very large, the crescent shape of the image disappears altogether and the light [on the wall] becomes round if the hole is round… with any shaped opening you like, the image always takes the same shape… provided the hole is large and the receiving surface parallel to it.

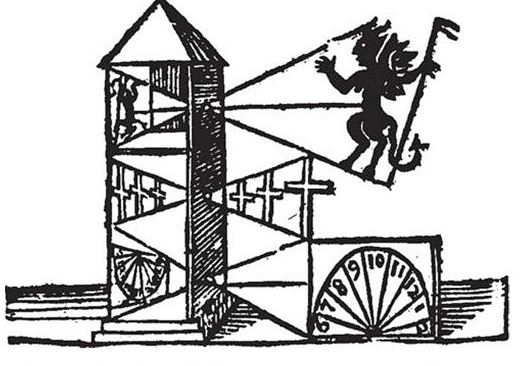

fig. 7 Three-tiered camera obscura, 13th century? (attributed to Roger Bacon)

However, Alhazen's work influenced the English philosopher and Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c. 1219/20–c. 1292; fig. 7), who was interested in optics. In 1267, Bacon created convincing optical illusions by using mirrors and the basic principles of the camera obscura. Later, he used a camera obscura to project the image of the sun directly upon an opposite wall. For centuries, the camera obscura was primarily used to watch solar eclipses because the human eye cannot tolerate the amount of light that floods into it when it looks directly at the sun. In any case, all of the first cameras were literally “dark rooms.” Inside the room, one could see what was happening outside.

In 1490, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was the first to suggest that the camera obscura might be of interest to the artist.

If the facade of a building, or a place, or a landscape is illuminated by the sun and a small hole is drilled in the wall of a room in a building facing this, which is not directly lighted by the sun, then all objects illuminated by the sun will send their images through this aperture and will appear, upside down, on the wall facing the hole. You will catch these pictures on a piece of white paper, which placed vertically in the room not far from that opening, and you will see all the above-mentioned objects on this paper in their natural shapes or colors, but they will appear smaller and upside down, on account of crossing of the rays at that aperture. If these pictures originate from a place which is illuminated by the sun, they will appear colored on the paper exactly as they are. The paper should be very thin and must be viewed from the back.

These descriptions, however, would remain unknown until Giovanni Battista Venturi (1746–1822) deciphered and published them in 1797.

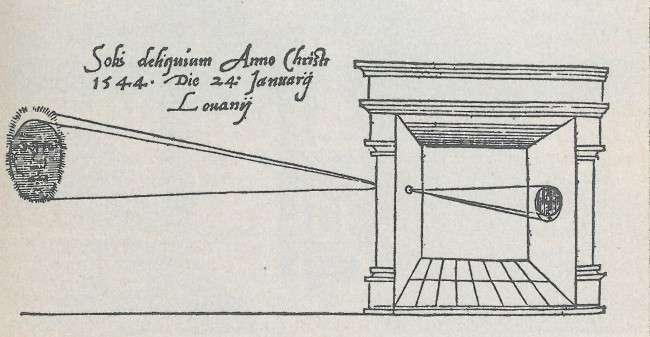

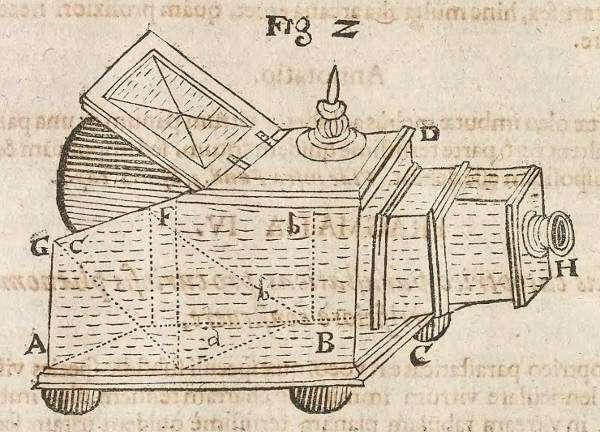

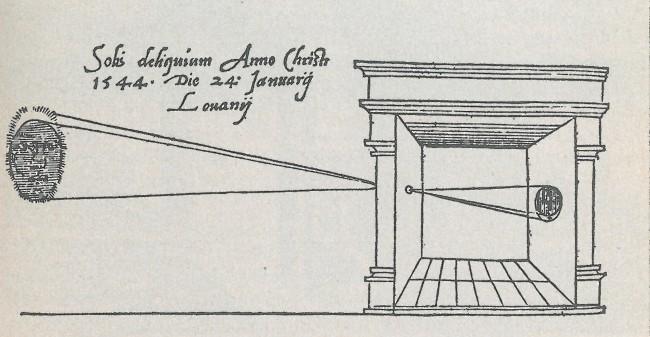

The oldest known drawing of a camera obscura (fig. 9) is found in De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica (1545), by the Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument maker Gemma Frisius (1508– 1555), in which he described how he used the camera obscura to study the solar eclipse of January 24, 1544. In fact, the oldest employment of the camera obscura, dating back to antiquity, was for astronomical purposes, for safely observing phenomena connected with the sun, in particular solar eclipses and sunspots. Since the stationary room-type camera obscura had no focusing mechanism, the only way the viewer could render its often blurry imagessharper was to move a sheet of paper on which they were received back and forth until the point at which the image came into focus was found.

fig. 9 First published picture of camera obscura in Gemma Frisius' 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica

fig. 9 First published picture of camera obscura in Gemma Frisius' 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica

The first documented mention of a "glass disc," probably a convex lens, used in conjunction with the camera obscura is in the Italian mathematician Girolamo Cardano's (1501–1576), De subtilitate, vol. I, Libri IV(1551). He suggested to use it to view "what takes place in the street when the sun shines" and advised to use a very white sheet of paper as a projection screen so the colors wouldn't be dull. Eight years later Giovanni Battista della Porta (1535?–1615), an Italian scholar, polymath and playwright, wrote that the camera obscura, which he called a "obscurum cubiculum," made it “possible for anyone ignorant in the art of painting to draw with a pencil or pen, the image of any object whatsoever” (Magiae Naturalis, first edition, 1558). With Della Porta's book, written in a simple and popular language, news of the camera obscura spread rapidly. Magiae Naturalis was so successful that it was translated into Arabic and several European languages, including Dutch. This explains why Della Porta was sometimes considered as the inventor of the camera obscura. Della Porta also compared the human eye to the camera obscura: "For the image is let into the eye through the eyeball just as here through the window."

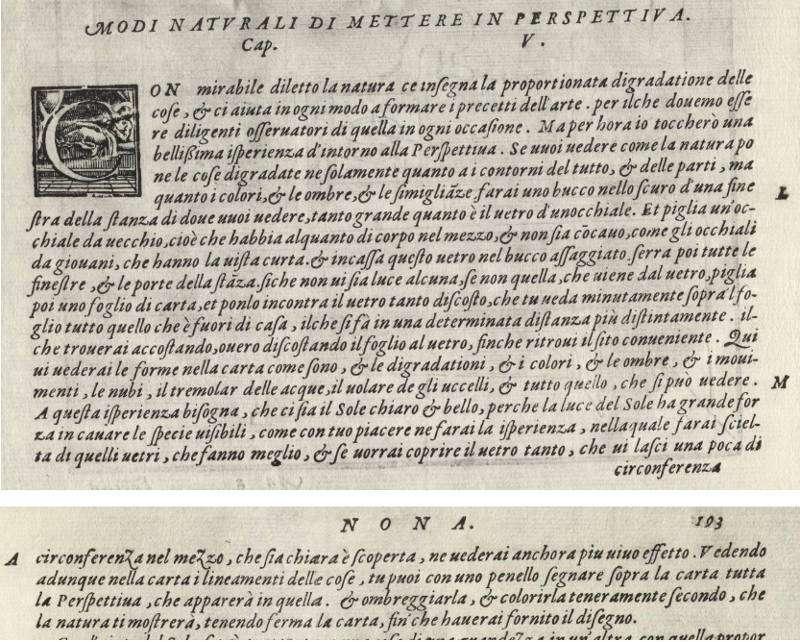

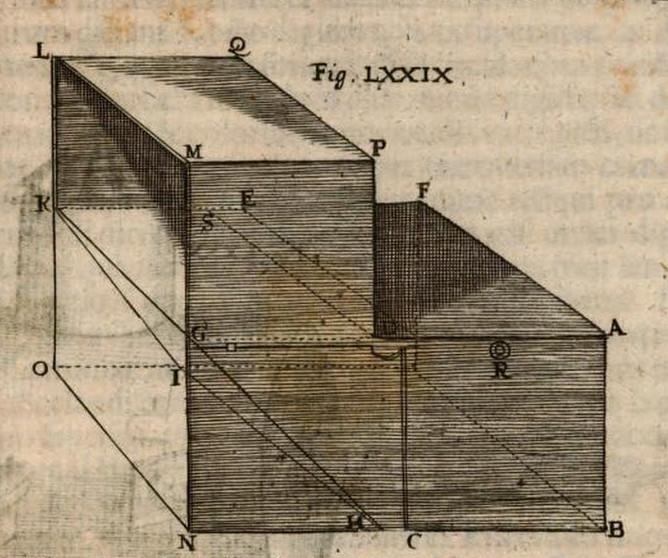

As early as 1568, Daniele Barbaro (1513–1570), a Venetian patrician famous for his editions of the Roman architectural writer Vitruvius, had proposed that the camera be used explicitly for producing drawings in correct “perspective” in his La pratica della perspettiva (1568; fig. 10), one of the most influential texts on perspective at that time. He called it "a most beautiful experiment concerning perspective."

Close all shutters and doors until no light enters the camera except through the lens, and opposite hold a piece of paper, which you move forward and backward until the scene appears in the sharpest detail. There on the paper you will see the whole view as it really is, with its distances, its colors and shadows and motion, the clouds, the water twinkling, the birds flying. By holding the paper steady you can trace the whole perspective with a pen, shade it and delicately color it from nature.

While Leonardo encouraged his readers to make paintings that correspond with the images that appear inside the camera obscura, Barbaro actually recommended coloring them, most likely because, not being an artist, he naively assumed that laying in colors might be easily done. But perhaps more importantly, Barbaro described how to improve the image of the camera with a lens:

You should choose the glass [lens] which does the best, and you should cover it so much that you leave a little in the middle clear and open and you will see a still brighter affect.

By “covering it so much that you leave a little in the middle clear and open” Barbaro evidently meant that the diameter of the lens should be partially narrowed toward its middle, or “stopped down” in modern photography lexicon, in order to create a sharper image, thereby discovering the diaphragm. He used a bi-convex lens taken from a pair of ordinary spectacles used by old men—concave lenses suitable for short-sighted young people brought little success. A lens greatly improves the quality of the camera's image because it allows for a much larger aperture that significantly increases the luminosity of the projection (the pinhole camera produces an image so dim that it is useless for the purpose of painting). Barbaro himself also suggested it could be used to make copies of maps.

fig. 10 La pratica della perspettiva... (pp. 192–193)

fig. 10 La pratica della perspettiva... (pp. 192–193)

Daniele Barbaro

Publsihed: Venice, C. & R. Borgominieri, 1568

Following Barabaro's improvements of the lens, diaphragm and focusing mechanism, many writers began to recommend the camera as an aid to artists. For example, in 1521 Cesare Cesariano (1475–1543), an Italian painter, architect and architectural theorist, wrote that other than for astronomers and opticians (anyone who studies optics) the camera would be of great use for painters.

Some modern writers have proposed that seventeenth-century lenses were largely inadequate for the purpose of painting with a camera obscura. But, according to Cartesn Wirth, "it was not so much the technology of lens grinding, which was still fairly undeveloped at the beginning of the seventeenth century, but rather the limitations of glass technology that presented a problem with regard to producing an objective for a camera obscura with a significantly large diameter. Defects in the glass or an irregularity in grounding have devastating effects in astronomic optics. In contrast, the image of the projection in a camera obscura is fairly insensitive to such faults. Many of the defects that are disturbing in a telescope optic are barely–or not at all– perceptible in the projecting optic of the camera. An unbiased viewer with no concept of a perfect optic might even admire the multiple optical effects in the image of the projection rather than judging them to be a disturbance."4

Portable camera obscuraIn 1572, the German mathematician Friedrich Risner (c.1533–1580) proposed a portable camera obscura drawing aid; a lightweight wooden hut with lenses in each of its four walls that would project images of the surroundings on a paper cube in the middle. The construction could be carried on two wooden poles, like a litter used to transport royalty. A very similar setup was illustrated in 1645 in Athanasius Kircher's Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae (fig. 11).

fig. 11 Engraving of a "portable" camera obscura in Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae

fig. 11 Engraving of a "portable" camera obscura in Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae

Athanasius Kircher

1645

The use of a mirror in conjunction with the camera obscura was first suggested in a manuscript Theorica speculi concavi sphaerici by the Venitian Ettore Ausonio (1520–1570). In 1585, Giovanni Battista Benedetti (1530–1590) proposed the use of a mirror angled at 45 degrees to the direction of the light coming from the lens in order to right the image. In those times, however, mirrors were simply polished metal plates and as such were probably much less reflective than even the cheapest of today's mirrors—the highly reflective mirrors of today were invented somewhere around 1850 when opticians learned how to apply a shiny silver film to a polished flat piece of glass.

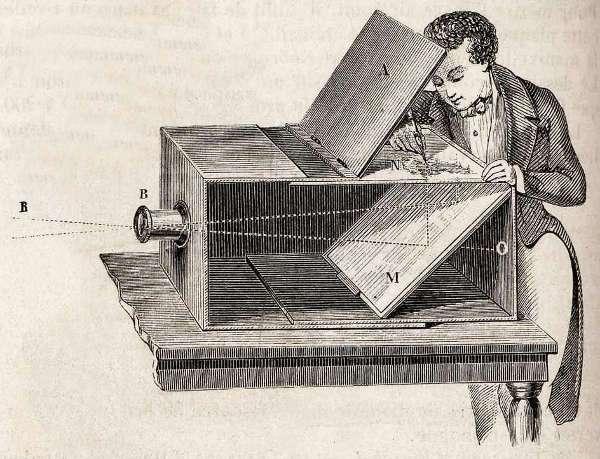

fig. 12 Illustration showing how to operate a camera obscura in The American educator; completely remodelled and rewritten from original text of the New practical reference library, with new plans and additional material (vol. 2; p. 652)

fig. 12 Illustration showing how to operate a camera obscura in The American educator; completely remodelled and rewritten from original text of the New practical reference library, with new plans and additional material (vol. 2; p. 652)

Ellsworth Foster and James L. Hughes

Publsiher: Ralph Durham Co. Chicago (IL)

1919

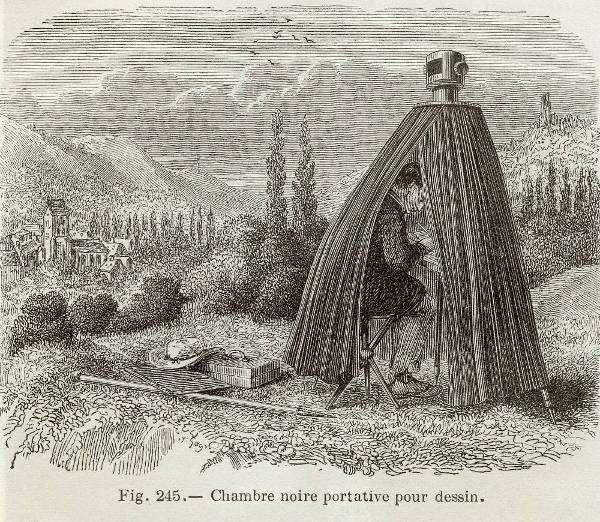

fig. 13 "Chambre noire portative pour dessin"

fig. 13 "Chambre noire portative pour dessin"

Adolphe Ganot

Engraving from: Cours de physique purement expérimentale et sans mathématiques... , chez l’Auteur

Paris, 1863, p. 404, n° 245.

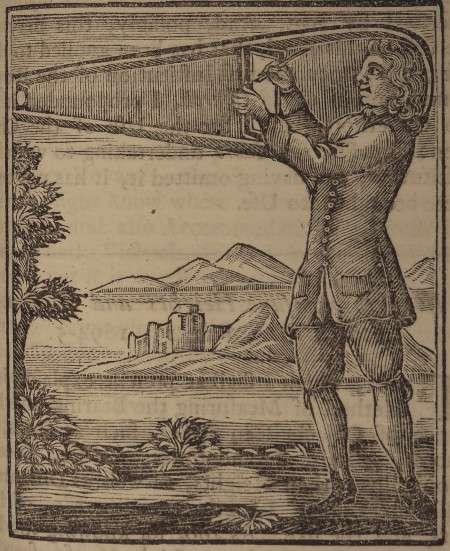

In 1604, the term “camera obscura” (in Italian=dark room), was coined by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) who developed the first portable camera obscura in the form of a tent (fig. 13), with a sheet of paper inside onto which the camera's image could be projected. According to a letter written to Francis Bacon by Sir Henry Wotton (1568–1639) who met Kepler in Linz in 1620, this portable camera had been invented by Kepler for sketching the complete 360° panorama (although Wotton reported that Kepler used the camera obscura to draw from nature Kepler claimed he used it “as a mathematician, not as a painter.")

He hath a little black tent which he can suddenly set up where he will in a field, and it is convertible (like Wind-mill) to all quarters at pleasure capable of not much more than one man, as I conceive, and perhaps at no great ease; exactly close and dark, save at one hole, about an inch and a half in Diameter, to which he applies a long perspective-trunke, with the convex glass fitted to the said hole, and the concave taken out at the other end, which extendeth to about the middle of this erected Tent, through which the visible radiations all the objects without are intromitted, falling upon a paper, which is accommodated to receive them; and so he traceth them with his pen in their natural appearance, turning his little Tent round by degrees, till he hath designed the whole aspect of the field: this I have described to your Lordship, because I think there might be good use made of it for Chorography [the making of maps and topographical views]: For otherwise, to make landskips by it were illiberal, though surely no Painter can do them so precisely. (Reliquiae Wottoniae, London 1651, pp. 413-414.)

In 1611, Frisian/German astronomers David (1564 –1617) and Johannes Fabricius (1587–1616) studied sunspots with a camera obscura, after realizing looking at the sun directly with the telescope could damage their eyes. They are thought to have combined the telescope and the camera obscura into camera obscura telescopy. From 1612 to at least 1630, Christoph Scheiner (c. 1573–1650), Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer in Ingolstadt, would keep on studying sunspots and constructing new telescopic solar-projection systems ((fig. 14). He called these "Heliotropii Telioscopici," later contracted to helioscope. For his helioscope studies, Scheiner built a box around the viewing/projecting end of the telescope, which can be seen as the oldest known version of a box-type camera obscura. Scheiner also made a portable camera obscura.

fig. 14 Christoph Scheiner and a fellow Jesuit scientist trace sunspots in Italy in about 1625

Rosa Ursina sive Sol ex admirando facularum & macularum suarum phoenomeno varius. (p. 150)

Christoph Scheiner

1626–1630

Published Bracciano: Andreas Phaeus at the Ducal Press, 1626–1630

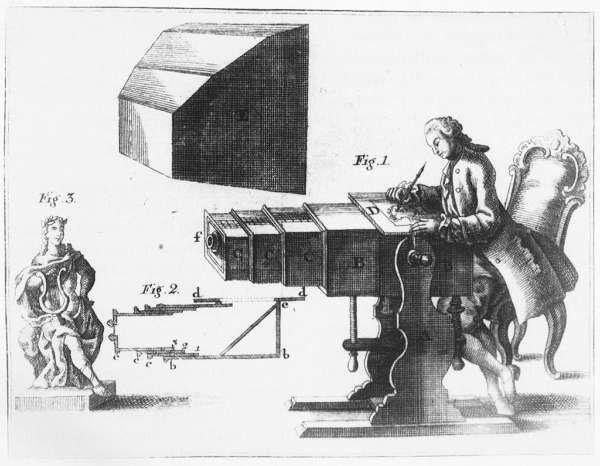

fig. 15 Camera Obscura by Georg Friedrich Brander, 1769

fig. 15 Camera Obscura by Georg Friedrich Brander, 1769

"By 1572, the room-type camera obscura had been shrunk down to a small, portable room, which can be thought of, after all, as a very large box. However, when pin-pointing the first appearance of box-type camera obscuras—devices in which the lens, the mirror and the screen on which the image was projected were put inside a small wooden box—most writers date it to around the mid-seventeenth century, nearly a hundred years later. Gaspar Schott (1608–1666) described a portable camera obscura in his Magia Universalis, in 1657, and in 1669 the British philosopher Robert Boyle (1627–1691), in his paper "Of The Systematicall And Cosmical Qualities Of Things, " (1669) drew landscapes in a box-type camera, perhaps similar to figure 15, he claimed to have constructed 'several years ago.'"5The portable camera fitted with a lens, mirror and translucent screen (fig. 11) became the standard configuration from the late seventeenth century onward.

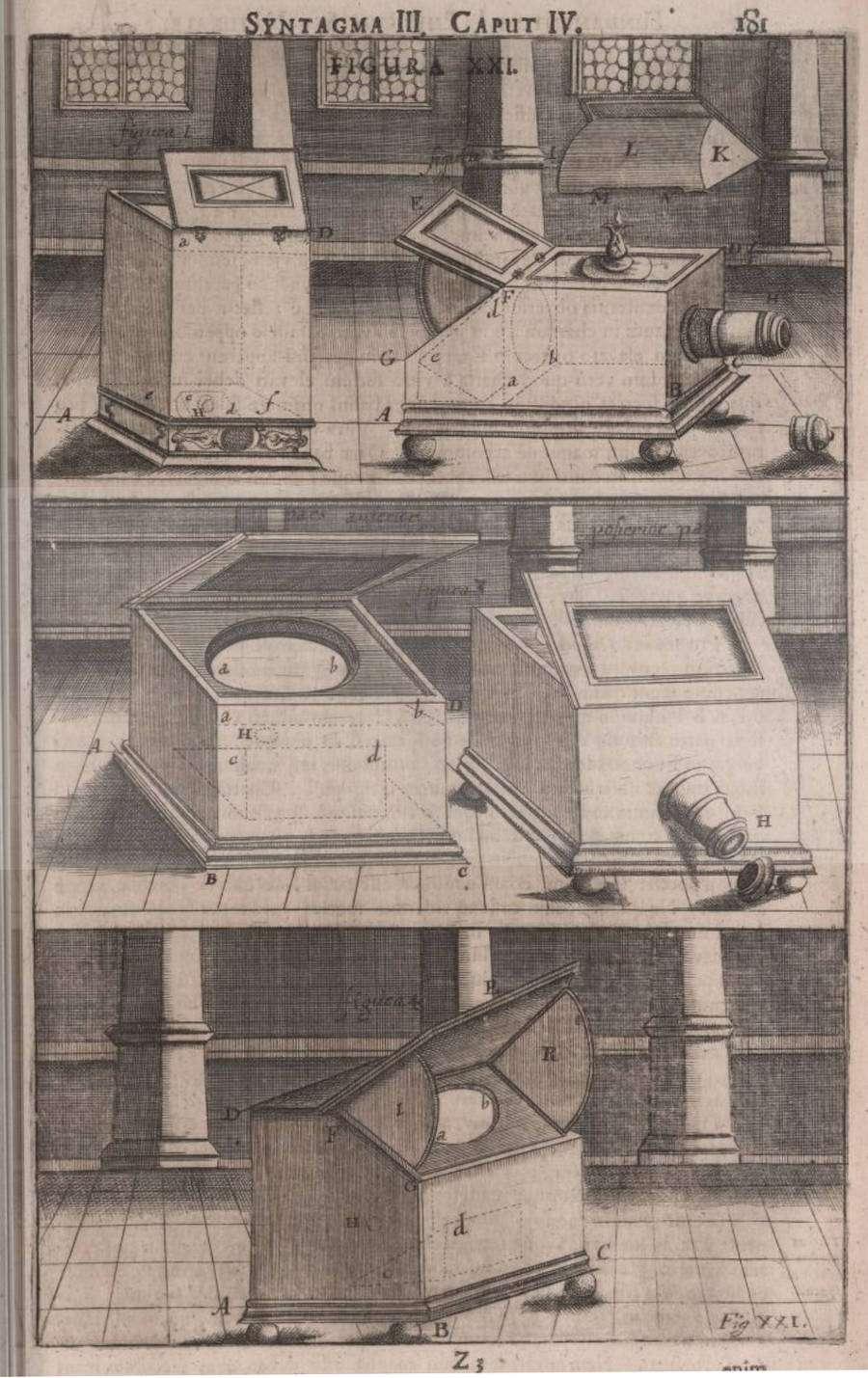

The simple portable camera (fig. 16 & 18)) is essentially a photographic camera without a light-sensitive film or plate. So simple but so effective is the device that it has changed only in size and decoration since the sixteenth century. In portable form, the camera obscura became popular for recording landscape and city views. Using a system of lenses and mirrors that allowed the image to appear on a translucent screen, draftsmen could trace the views to produce early versions of tourist snapshots. The booth-sized version of the camera obscura (fig. 17) was also useful to scientists interested in the behavior of light. The English natural philosopher, architect, polymath and tireless inventor Robert Hooke (1635–1703), built different types of portable cameras for making illustrations for the travel guides or topography. One particularly curious contraption was a “wearable” beak-like object (fig. 19) which, according to his description, was an “an instrument of use to take the draught, or picture of any thing" Philosphical Experiments and Observations (1762). At the time it had become evident that the lens in the camera should be as "bright" as possible, that is, have as large a diameter as possible. Hooke suggest using as a lens a "[...] Glass, which the larger it is the better, because of several Tryals that may be made with it, which cannot be made with a smaller [one]." In 1685, Johann Zahn (1641–1707) was probably the first to have designed a camera obscura that could be manually focused by moving the lens, instead of relocating the screen (fig. 18 & 21).

fig. 16 Illustration from Adolphe Ganot, An Elementary Treatise on Physics, 1882

fig. 16 Illustration from Adolphe Ganot, An Elementary Treatise on Physics, 1882

fig. 17 A booth-type camera obscura from Méthode Pour Apprendre Le Dessin, Ou l'On Donne Les Regles Générales de Ce Grand Art, Et Des Préceptes Pour En Acquérir La Connoissance, Et s'y ... (p. 178)

C. A. Jombert

Paris, 1755 (p. 136)

fig. 18 Illustration of a camera obscura in Oculus artificialis teledioptricus sive telescopium.. (p. 178)

fig. 18 Illustration of a camera obscura in Oculus artificialis teledioptricus sive telescopium.. (p. 178)

Johann Zahn

Publisher: Sumptibus Johannis Christophori Lochneri Bibliopolæ, typis Johannis Ernesti Adelbulneri, Norimbergæ

1702

fig. 19 "An Instrument of Use to take the Draught, or Picture of any Thing," from Philosophical Experiments and Observations

Robert Hooke

London, 1726

Ink on paper

University of Michigan

Camera obscuras of the period were fitted with a single converging lens. There is no mention of any use of multiple lens configuration needed for telescopy in relation to the device. In the time of Vermeer, lenses could be easily purchased from itinerant peddlers—lenses were primarily produced for spectacles—but if one needed a particular lens, for example, for a telescope, they could be ground to specification by a lens grinder. To be sure, a lens improves the luminosity of the image considerably, but it comes with some serious drawbacks. Everything towards the edges is blurry, color fringes appear around bright objects and objects that occupy different planes in space are not all in focus at the same time, even if they are located at the middle of the image. If, for example, Vermeer had brought into focus the foreground chair in The Art of Painting with a camera obscura, the wall-map and the chandelier would have appeared more as colored clouds than solid objects. The individual elements of both objects would have blended completely together and been impossible to distinguish, much less trace. This problem could be temporarily remedied by refocusing, i.e., moving the position of lens back and forth, but the objects that were previously in focus become blurry. There is no way that all planes can be brought into a focus with a single lens, no matter what its shape or configuration.

Some authors have written that color is intensified in the camera obscura image, but this is not objectively proven by any means. Moreover, even the best image of the camera has an overall milky quality—one never has the sensation that absolute black can be perceived. Goethe (1749–1832) noted that the image cast by the lens causes everything to appear "as covered with a faint bloom, a kind of smokiness that reminds many painters of lard, and that fastens like a vice on the painter who uses the camera obscura." But unlike the reflections in a mirror or water, the projection of the camera is perceived as relatively flat, a fact which is particularity advantageous for the painter. In any case, even in the best cases the image produced by the camera is never as sharp, contrasted or as colorful as any painting by Vermeer.

The camera obscura in the time of VermeerThus, the camera obscura was well known in the time of Vermeer. As early as 1622, ten years before Vermeer was born, news of the camera obscura circulated in the Netherlands. In that year, Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), who maintained contacts with eminent artists such as Rubens (1577–1640), Van Dyck (1599–1641), Rembrandt (1606–1669) and perhaps Vermeer himself, purchased a portable camera obscura in London6 from the Dutch engineer and inventor Cornelis Drebbel (1572–1633), and enthusiastically wrote about the image that it produces:

I have at home Drebbel's other instrument, which certainly makes admirable effects in painting from reflection in a dark room It is impossible to express its beauty in words. The art of painting is dead, for this is life itself: or something higher, if we could find a word for it. Shape, contour and movement come together naturally, in a way that is altogether pleasing.

–

Huygens would also report the names of at least two painters who knew about the device, which in his words was “now-a-days familiar to everyone…” Following the example of earlier Italian writers, Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678), an accomplished Dutch painter and author of the widely read tract of painting Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst (1678), recommended the camera obscura to painters:

I am certain that the sight of these reflections in the darkness can be very illuminating to the young painter’s vision; for besides acquiring knowledge of nature, one also sees here the overall aspect which a truly natural painting should have.

A second time he calls the optical machine “a picture-making invention with which one can paint by means of reflections in a closed and darkened room everything which is outside.” However, even though the device was enthusiastically recommended for painting, at least one painter is know to have concealed his familiarity with it, leaving open the possibility that other painters may have used it but chose to conceal their involvement.

Thus, as an aid to painting per se, the camera obscura cannot be considered absolutely innovative in Vermeer’s time: it may be said that a fair number of Dutch painters knew it, and a few probably worked with it, although never on a systematic basis. No documented source that suggests that Vermeer knew of or used a camera obscura has come down to us.

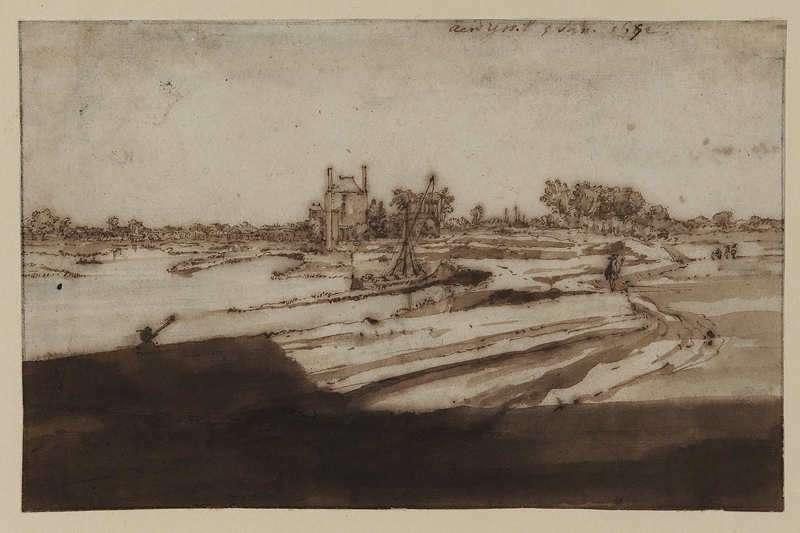

“In Delft, vision-extending and vision-transforming instruments such as the camera obscura must have been readily available. They were the passion of Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), an industrious researcher now best known for his discovery of micro-organisms through the microscope. It is almost impossible to imagine that these exact contemporaries, both baptized in 1632 and both high achievers in their fields, would not have come across each other in the small city of Delft.”7 It has also been suggested…that Vermeer developed an interest in optics through a connection with the painter Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), who moved to Delft in about 1650; or, via Fabritius, with his friend Van Hoogstraten of Dordrecht. Both men were fascinated by the trompe-l’oeil and perspective illusion.8 In any case, the reflected image of the camera obscura, no matter how novel it may have appeared in the seventeenth century, was probably a bit more familiar to the Dutch people who were used to living in a world of reflections, constantly seeing their houses, trees and skies mirrored in canals and lakes.9 It is said that Constantijn Huygens II, a skilled lens maker and draughtsman made a series of landscapes that presumably bear the hallmarks of the camera obscura, although there is no documented evidence that the device was actually used in this case (fig. 20).

There is only one source that specifically claims that painters of Vermeer's time actually used the camera obscura as an aid to their painting. G. J. s'Gravesande, who was born thirteen years after Vermeer's death, wrote : "Several Dutch painters are said to have studied and imitated, in their paintings, the effect of the camera obscura and its manner of showing nature, which has led some people to think that the camera could help them to understand light or chiaroscuro. The effect of the camera is striking, but false."

fig. 20 View of the Ijssel

fig. 20 View of the Ijssel

Constanitjn Huygens

5 June 1672

Pen and ink, Sepia ink, Watercolour

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The Italian landscape painters Canaletto (1697–1768), and Bernardo Bellotto (c. 1721–1780) are said by some art historians to have used the camera to create perspective views of Venice and other cities. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) constructed a small portable camera, presently conserved in the Science Museum of London, for portrait painting.10 After that, the camera was never taken seriously among artists although it continued to be employed by topographical draftsmen and as a source of entertainment to this very day.

It should be remembered that when the device began to be used by professional painters in the eighteenth century, it was never intended as to aid to capture light or darkness, or reproduce color. When mentioned in relation to painting it was almost universally understood to be useful in rendering a complex scene into its outlines, reducing a landscape, for instance, into a series of lines, zones, or bands.

fig. 21 Various types of portable camera obscuras in Oculus artificialis teledioptricus... (p. 181)

fig. 21 Various types of portable camera obscuras in Oculus artificialis teledioptricus... (p. 181)

Johann Zahn

1658

Published: Herbipoli, Würzburg, Germany

But the future of the camera obscura lay not in its usefulness to painters, but as an indispensable precursor to the modern photographic camera.

Why is “Tim’s Vermeer” so Controversial?

On November 17, 2016

Screenshot from Tim’s Vermeer. Tim Jenison sits in his recreation of the room in Vermeer’s The music lesson.

“What do you think about the theory that Vermeer used an elaborate technique involving mirrors when he painted (as proposed in the movie Tim’s Vermeer)?” – asked by Michael

Note: This post will contain spoilers for the movie Tim’s Vermeer.

The documentary film Tim’s Vermeer follows inventor Tim Jenison on his quest to recreate a Vermeer painting using a system of mirrors. The film argues that Vermeer could have used this method when creating his artworks. It also – whether on purpose or not – opens up some interesting art historical debates regarding the concept of “artistic genius” and the separation of art and technology.

I had never seen this movie when I received this question, so for those of you in my situation, here’s a short description: Tim’s Vermeer is a 2013 American documentary film about inventor Tim Jenison’s experiments with duplicating Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer’s paintings. His experiments were based on the idea that Vermeer created his artworks with the help of mirrors. Jenison eventually succeeds in figuring out a technique that allows him to perfectly paint a scene in front of him despite having no artistic training. He thus reconstructs and paints the scene depicted in Vermeer’s The music lesson (1662 – 1665).

The music lesson (1662 – 1665), Johannes Vermeer

First of all, for those who don’t know who Johannes Vermeer is: Vermeer was a Dutch artist, and is one of the most famous artists of all time. You might know him as the artist behind Girl With A Pearl Earring (1665). Vermeer was active during the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th century, and is especially known for his beautifully still and intricate genre paintings.

Given that Vermeer is such a famous artist, the film has been controversial with many art historians and art critics. So let’s take a look at what happens in it, and why it’s been so controversial.

Painting using mirrorsThe claim that Vermeer used some sort of optical device to create his paintings is not new. Vermeer’s life is still a bit of a mystery to us. As the film states, we don’t have any documentation about how he was trained or what sort of methods he used while painting. We do know, however, that mirrors and optical devices were widely known in 17th century Dutch society. This factor, along with the photorealistic quality of Vermeer’s paintings, has caused speculation about his potential use of mirror technology.

Illustration of camera obscura in De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica (1545), Gemma Frisius

Tim Jenison’s theory is inspired by a book, Vermeer’s Camera, written by architect Philip Steadman. It argues that Vermeer used a camera obscura to create his paintings – a theory that in itself has existed since the late 19th century. A camera obscura is a device that allows for a naturally occurring optical phenomenon: when one side of a darkened room or box gets a small hole put into it, the image on the other side becomes projected onto the surface opposite the hole. A lens can then be put into the hole to change the image. Camera obscura devices have been in used as aids for drawing and painting for centuries.

Illustration of a portable camera obscura device from Johann Cristoph Sturm’s Collegium experimentale, sive curiosum (1676)

The specific technology that Jenison invents (or rediscovers) involves a mirror rather than a camera obscura. The problem with the camera obscura is that, if you try to paint over the projection, the colour becomes distorted. Instead, Jenison fastens a small mirror above the canvas at a 45 degree angle. This allows him to paint around it until he finds the exact colour, constantly monitoring the reflection.

Screenshot from Tim’s Vermeer. A demonstration of the mirror technique used in the film.

After some adjustments to the technique, Jenison eventually succeeds in painting an entire Vermeer painting over the course of several years. He does this by reconstructing the exact scene from the artwork in real life and then using the mirror to paint it.

Although we can’t prove it (and might never be able to), the theory holds up. It should, in my opinion, be taken seriously as a possibility. It has the support of art historians and artists, and builds on the two most fundamental art historical methods: visual analysis and historical context.

The reactionIn the film, Philip Steadman tells Jenison that, when Vermeer’s Camera came out, it caused a “really deep anguish” amongst art historians. But if the theory is valid, where does the controversy come from?

Well, in many ways, the movie challenges the idea of “artistic genius”. This is a concept usually applied to the Western canon of artists. The canon is a generally agreed-upon list of the “greatest” artists in art history. It consists of artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Pablo Picasso, Michelangelo, Claude Monet, Rembrandt van Rijn, and – of course – Vermeer. They’re considered the most innovative, groundbreaking artists throughout history – essentially, geniuses.

With very few exceptions, the Western canon consists almost exclusively of white male artists. This norm persists in art historical books, museums, university courses and research. So in questioning the ideals of the canon, we also have to question the idea of “genius”. Do only white male artists possess “genius”, or is a constructed concept? Does clinging to the idea of genius stop us from exploring new, interesting avenues in art history? Does it stop us from actually getting a better understanding of the artists we’re studying?

No matter how much the idea of “genius” has already been challenged, the reaction to Tim’s Vermeer shows that we still have a long way to go. Art critic Jonathan Jones, in his review in The Guardian, argues that – although the theory is “highly possible” – the movie is “a depressing attempt to reduce genius to a trick”. He goes on to say that “the mysterious genius of Vermeer is exactly what’s missing from Tim’s Vermeer. It is arrogant to deny the enigmatic nature of Vermeer’s art.”

Left: The music lesson (copy) (2013), Tim Jenison. Right: The music lesson (1662 – 1665), Johannes Vermeer.

Of course, simply copying Vermeer’s artwork doesn’t make Jenison an amazing artist. Looking at the comparison above, it’s clear that Vermeer has a better handle on things like weight, depth and texture. And Jenison didn’t put together the composition itself – that was all Vermeer. There are definitely some good criticisms out there of the film and the way it oversimplifies Vermeer’s art.

But the film’s very existence forces us to confront our pre-existing ideas regarding the Old Masters. As Jenison points out in the movie, the separation of technology and art is a new concept. And, although ideas of “genius” have popped up throughout art history, our ideas of artistic genius as related to individual originality and creativity, rather than simply talent and knowledge, became ingrained and widespread in the West as late as the 19th century, most clearly shown through the ideals of Romanticism. Before that, artists usually produced their work for patrons rather than for themselves, and often worked with assistants and masters rather than alone.

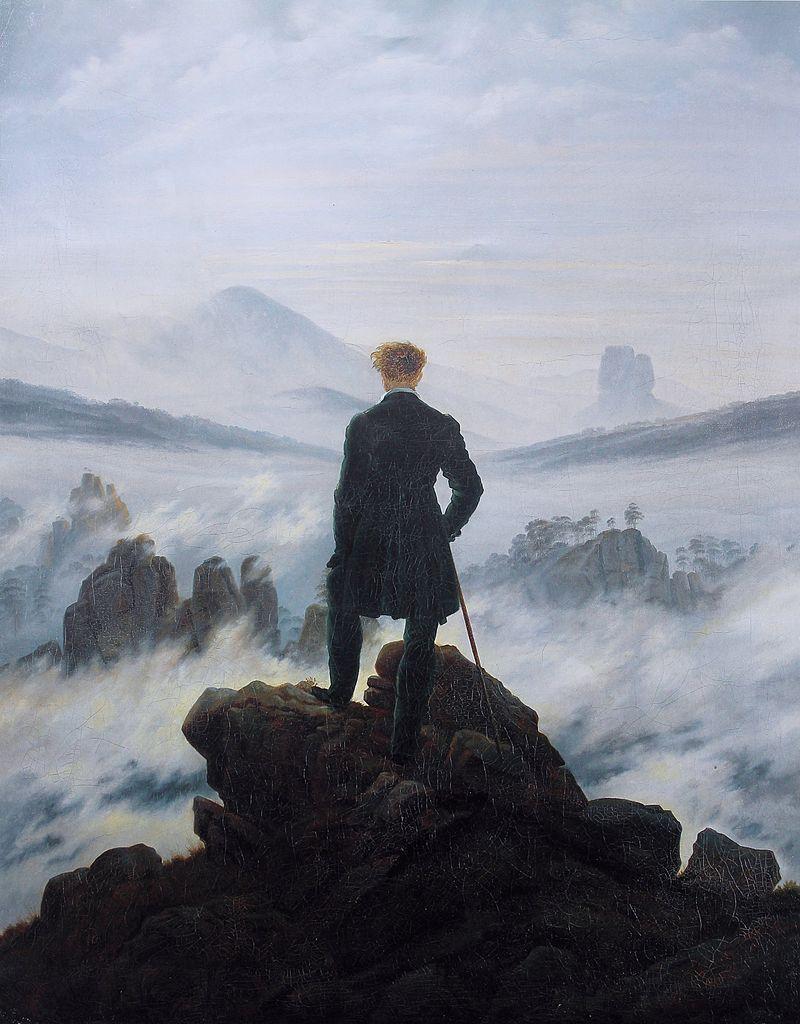

Our modern ideas of “artistic genius” could be said to originate from the Romanticism art movement, such as Wanderer above the sea of fog (1818) by Caspar David Friedrich.

Reducing Vermeer’s innovations and painterly practices to the useless idea of “genius” actually keeps us from fully understanding his work, and we need to allow space for research that contradicts it. Tim’s Vermeer asks some difficult, but necessary questions. Taking its theory seriously doesn’t mean that Vermeer was any less talented, or that his work should mean any less. It just means that, as art historians, we have to be willing to abolish the idea of “genius” and look at the wide range of artistic practices that exist across the world and throughout history.

Note: Article as been edited to clarify the idea of “genius” as appearing in the 19th century.

21