see attachment

Strategic Management and Planning

This case study assignment measures mastery of ULOs 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, and 1.7.

This assignment will require a thorough situation analysis and SWOT analysis to inform strategic recommendations. To begin, read Case 14: Lime: Is e-Bike Sharing the Next Uber? in the textbook.

Then, perform a comprehensive situation analysis for Lime’s U.S. domestic market. Your analysis should include identified factors from Lime’s external macroenvironment and internal microenvironment. Your external environmental analysis should be conducted using the PESTLEC model discussed in Unit II. The internal environmental analysis should be performed using the value-chain analytical model introduced in Chapter 3 and should include a detailed analysis of primary and support activities at Lime(The last page) The external and internal factors identified in the analyses may include factors discussed in Case 14 and should go beyond these since the textbook case information is not real-time. Please note that there may be multiple political forces, multiple economic forces, and so on, that are important to discuss, but not all forces from the PESTLEC model may be relevant to your business venture. You will decide later which relevant forces to move into the SWOT matrix. The information included in the situation analysis should not be anecdotal but rather heavily supported with recent scholarly sources.

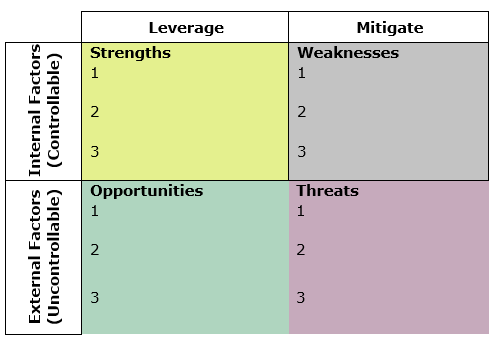

Perform a SWOT analysis informed by your situation analysis. Populate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats quadrants by correctly categorizing the most strategically relevant external and internal environmental factors that were identified in your PESTLEC analysis and value-chain analysis. There should be at least three factors in each quadrant of your SWOT matrix.

Use the SWOT matrix below, or a similar version of your choosing, to complete your SWOT analysis.

Following the completion of your SWOT matrix, complete the following:

Evaluate the internal and external factors you included in your SWOT and provide your rationale as to why you felt these factors were important to include.

Integrate insights from the SWOT with Ansoff’s product-market matrix introduced in Unit III to discuss strategies that address challenges with respect to Lime’s own internal strengths and weaknesses.

Explain the overarching purpose and value of performing external and internal analyses as a precursor to help formulate business strategies to achieve competitive advantage within a market. Explain how the purpose and value of a situation analysis is different from that of a SWOT analysis.

Academic work should always be supported with credible sources. It will be necessary to rely on credible secondary sources to complete this assignment, particularly when performing your situation analysis. At least three sources should support your work.

Please write objectively from the third-person point of view. Avoid writing in the first-person voice (i.e., I and we) and second-person voice (i.e., you and your).

While quality is preferred over quantity, your thorough and substantive situation analysis and SWOT should be at least four pages in length, not counting the required title and reference pages.

Submit your assignment in a Word document following APA Style. You may use section headings and subheadings that align with the assignment requirements. These will ensure you complete all requirements, and it makes a professional presentation

Reading Material

LIME: IS E-BIKE SHARING THE NEXT UBER?*

On November 5, 2021, electric scooter and e-bike sharing provider Lime raised $523 million of convertible debt and term loan financing through investors Abu Dhabi’s growth fund, Fidelity Management & Research Company, Uber Technologies Inc., and Highbridge Capital Management. Lime said its latest funds would be utilized to scale up its Gen4 e-scooters and e-bikes that include additional reflectors to improve rider visibility and a swappable battery between both vehicles.1 The company also planned to use about $20 million of the financing to develop more sustainable hardware and lower the carbon footprint of its supply chain, part of the company’s goal to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. “We think this is a big sign there’s a renewed confidence in micro-mobility,” Chief Executive Officer Wayne Ting said. “I think it’s a recognition that Lime is now the undisputed leader in this space.”

Since its launch in 2017, Lime has managed to gain popularity among the rental transportation market with more than a thousand competitors around the globe. While Lime is one of the leading companies that created the market for cost-effective bike-sharing systems in the United States, it faces several hurdles with neck and neck competitors, municipal pushback, vandalism, and establishing a strong survival strategy for the long run.

Bike-share in the United States has continued its brisk growth, with around 136 million trips taken in 2019, a 60 percent increase from 2018.2 Lime entered the marketplace with a goal of eliminating docking stations in order to make bikes more affordable in comparison to traditional bike-sharing models. The idea of saving millions per year for cities that invested in expensive stations and overpriced bikes appealed to both consumers and the government. The Lime dockless bike-share company operates in over 200 cities globally, with presence in over 30 countries. The mobile app charges $1 to unlock and 15 cents/min to ride after the user unlocks the bike (see Exhibits 1 and 2).

EXHIBIT 1 Lime Electric Bike

Alena Veasey/Shutterstock.

EXHIBIT 2 Lime App and Lime Electric Scooter

Vincent K Ho/Shutterstock.

While early 2019 looked really promising for Lime with the startup being valued at a whopping $2.4 billion, the Covid-19 pandemic significantly stalled its growth prospects. Lime saw an almost 90 percent drop in ridership during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. The San Francisco based startup had to suspend operations across 22 countries including North America during March 2019, but ridership did see a slow return during the summer months as consumers started looking for ways to stay active.3 In mid-2020 Lime signed a $170 million investment deal with Uber that would see Uber increase its stake in Lime. However this much-needed cash infusion came at a cost, i.e., a 79 percent reduction in valuation, placing Lime at just $510 million.4 Lime’s partnership with Uber began in August 2018, when the bike-sharing startup signed a deal with Uber to provide e-scooters as Uber planned to expand its service to bikes and scooters. Uber’s partnership with Lime came as a surprise to some close watchers of the brewing scooter wars, especially considering one of the company’s main competitors in dockless scooter-sharing, Bird, was founded by a former Uber executive.5

Page C121

What is Lime’s long-term strategy in a market with almost more rental business competitors than bikes or scooters to rent?

World of Bike Sharing

Bike sharing can be traced all the way back to 1965 when the White Bicycle Plan was launched in Amsterdam where free white bicycles were placed in various locations. This was introduced by Luud Schimmelpennink, a Dutch industrial designer, who intended to reduce air pollution in the city and facilitate public use of bicycles. While the idea was quite ahead of its time, it collapsed within days due to theft and damage of bikes. The problem of theft was only solved in 1996, when Bikeabout, a small bike-share system limited to students at Portsmouth University in the UK, introduced an individualized magnetic-stripe card to borrow a bike.6 Over the next 15 years many of the major cities across the globe introduced bike-share systems with 2013 witnessing 65 new bike-share launches in China alone. By 2021, the number of bike-share bicycles had hit 10 million with China leading the bike-share market.7

Dockless bikes go back only a few years. The market for bike sharing had increased rapidly throughout the world by 2021. The third generation of bikes consisted of the automated station-based bikes, which could be borrowed from one docking station and returned at another station of the same system. With the automated biking stations, individuals could unlock their bikes with a smartcard or their phones. In 2015, public bike-sharing programs existed on five continents, in 712 cities, operating approximately 806,200 bicycles at 37,500 stations.8 This led companies to invest more time and effort into creating a more cost-effective system, which led to a dockless bike-sharing system. In the United States, by the end of 2019, people took 40 million trips on station-based bike share systems (pedal & e-bikes) and 96 million trips on dockless e-bikes (10 million trips) and scooters (86 million trips); 109 cities had dockless scooter programs, a 45 percent increase from 20189 (see Exhibit 3).

EXHIBIT 3 Shared Micro-mobility Ridership Growth from 2010–2019, in Million Trips

Source: Bike Share in the U.S.: 2019. National Association of City Transportation Officials, nacto.org.

Station-based to dockless bikes is the transition that keeps investors on their toes as companies are looking at higher revenues with lower expenses; the only downside of dockless bikes are expenses in theft, vandalism, and fines. The four major dockless bike-sharing companies in the United States include Lime, Jump, MoBike, and Spin. Ofo, a tough competitor, began to withdraw from many U.S. markets in 2018 as it planned to expand its global reach. Another company, Bluegogo, which was the first to introduce dockless bike-share bikes in the United States, declared bankruptcy during the summer of 2018.10

Lime Background

In 2015, Chinese startups like Ofo developed a new bike-sharing model without the need for docking stations.11 This concept of dockless bikes led the San Mateo-based startup, Lime, to introduce dockless bikes in the United States in mid-2017. In March 2017, the company had managed to gather around $12 million of funding from investors such as Andreessen Horowitz and DCM. Lime launched its first market in Greensboro, North Carolina, in June 2017. By November 2017, it had reached over 300,000 users and penetrated 25 markets including 16 cities and 9 college campuses.

Page C122

Lime was founded by Toby Sun, Brad Bao, and Adam Zang on the simple idea that all communities deserve access to smart, affordable mobility. Their initial belief that electric bikes are preferred over classic bikes and electric scooters for long-distance trips led Lime to surpass over 6 million rides in just over 12 months. Twenty-seven percent of riders in major urban markets reported using Lime to connect to or from public transit during their most recent trip; and 20 percent of riders in major urban markets reported using Lime to travel to or from a restaurant or shopping destination during their most recent trip.12 In February 2018, with the recognition that there was market demand for scooters, Lime added electric scooters to its product mix. Riders can locate and unlock scooters using the company’s smartphone app, and after paying the $1 unlocking fee riders are charged 15 cents per minute of use. By 2019, the company had $169.1 million in revenues with over 1,200 total employees, up from just 50 employees in 2017.13

Policies and Regulations

Over the past decade, shared active transportation systems in the United States have begun to thrive. These systems are highly dependent on the assistance and cooperation of the government and the public. In many places, coordination between cities, operators, and other community stakeholders has allowed bike-share practitioners to grapple with complex issues around access and equity, expanding transportation options for low-income individuals, and focusing investments among communities with a history of chronic disinvestment.14

The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) is a nonprofit coalition of 89 major North American cities and 10 transit agencies formed to exchange transportation ideas, insights, and practices to cooperatively approach national transportation issues. The NACTO Policy states the guidelines for the regulation and management of shared active transportation. These guidelines include policies regarding small vehicle parking, community engagement, and equity programs. Some of the general provisions include:

Relevant local government or city authorization is required for bike-share companies and other mobility service providers to operate in the public right-of-way.

Cities should reserve the right to limit the number of companies operating (e.g., cap the number of permits or licenses issued, issue exclusive contracts, permits, or licenses).

Cities should reserve the right to revoke permits, licenses, or contracts from specific companies (e.g., when a company fails to comply with permit, contract, or license terms, or fails to meet national accreditation standards if applicable).

Cities must reserve the right to prohibit specific companies from operating in the public-right-of way based on conduct or prior conduct (e.g., when a company deploys equipment prior to applying for a permit, license, or contract, or fails to comply with permit, contract, or license terms).

Cities are required to reserve the right to establish operating zones and fine companies for bikes and equipment found outside of those designated areas.

With regard to the Operations Oversight by NACTO, cities should require companies to remove small vehicles (e.g., damaged, abandoned, improperly placed, etc.) within contractually agreed-upon time frames and assess penalties for failure to do so (see Exhibit 4). Each city is also required to have a limited number of shared small vehicles allowed. Los Angeles allows a minimum of 500 bikes and a maximum of 500 bikes per company, while Washington, DC, which recently witnessed a few cases of vandalism, allows a minimum of 50 bikes and a maximum of 2,500 bikes per company.

Page C123

EXHIBIT 4 Selected Permit Fees in the United States

City Status Permit/License Fee Per Bike Fee Performance Bond Relocation/ Removal Permit Duration

Boulder Approved $3,300 (Renewal: $1,800) $100 $O $80/bike Annual

Charlotte Approved(pilot) $O $O $O All costs Pilot endedNovember 1, 2018

Dallas Pending $1,620 — $48,600(Renewal Fee: $404) $21 $10,000 All costs 6 months

Sacramento Approved $14,480 — $28,440(Renewal Fee: $12,380 —$26,340) $O $O All costs Annual

St. Louis Approved $500 $10/bike $O All costs Annual

Washington, DC Approved(pilot) $O $O $O $O Pilot endedAugust 31, 2018

Source: nacto.org.

Intense Competition

With 136 million trips in 2019 and strong year-on-year growth since 2010, bike share is gaining hold as a transportation option in cities across the United States. High venture capital funding, coupled with generally low ridership, raises questions regarding the overall sustainability and volatility of the dockless bike-share market. The big four dockless bikes in the United States are Lime, Bird, Jump, and Spin. In less than a year of existence, one U.S.-focused company, Bluegogo, and a number of China-based companies have filed for bankruptcy, merged with other companies, or ceased operations.15

Lime believes it can fend off rivals with a city-friendly approach. That includes investing in higher-quality bikes (including safety features like solar-powered lights), sharing aggregated usage data with cities, and educating riders about where to leave their bikes.16 Cities are proceeding cautiously, watching the results of pilot efforts, and encouraging dockless companies to share more data so that cities can better evaluate and understand how dockless bike share can further city goals of safety, equity, and sustainable mobility (see Exhibits 5 and 6).

EXHIBIT 5 Lime’s Operating Cities

Source: Bloomberg.com

EXHIBIT 6 Global Monthly Active Users of Select E-Scooter Apps

Note: Lime and Bird are U.S.-based firms, Voi is based in Sweden, and Tier is based in Germany.

Source: Bloomberg.com.

Bird

Founded in 2017 in Santa Monica, California, and started with 250 e-scooters on Venice beach by CEO Travis VanderZanden, an alumnus of both Lyft and Uber, Bird began publicly trading on the NYSE (BRDS) in late 2021. The lead investor in Bird is Fidelity Management.17 The firm has raised more than $750 million in funding and operates in more than 350 cities.

Spin

Founded in 2016, Spin presented the idea of introducing Chinese dockless bikes to the United States. It first launched in Seattle, and further expanded to over 12 cities and 7 college campuses in the United States, and had over 1 million rides. In November 2018, Ford Motor Company acquired Spin for an estimated value of $80 to $90 million. With regard to the safety concerns of electric bikes, Spin offered an anonymous tip-line and promoted helmet usage. They also initiated pilot partnerships with safe street groups where Spin works with local community leaders who identify protected bike lane networks that are needed, and advocate for them to be built.

JUMP DC

JUMP’s bikes have an electric motor in the front wheel with a battery in the frame. When a rider pedals a little, the bike senses the effort and adds some of its own. JUMP’s bikes are the only dockless entry in Washington, DC, that use pneumatic tires, so their ride is less harsh.18 JUMP was originally founded as Social Bicycles and has been creating the hardware and software behind some of the greatest innovations in bike share since 2010.19 The company soon partnered with Uber, and in 2018 was acquired by Uber Technologies Inc.

Electric Scooters

While many cities now have bike-sharing services, electric scooters, which cost less than $2 per ride, are the next innovation in mobility. Investors rooting for the next Uber Technologies, Inc. and Lyft, Inc.,20 the app-based car-hailing services, are adding to the scooter-frenzy by pouring money into Bird and Lime, which are competing on a city-by-city basis to become the premier electric scooter brand. Bird is limited to operating scooter services in about 44 U.S. cities, while Lime offers its services in 53 U.S. cities.

Lime has established a presence in France, Germany, and Spain. Scooters are even more prevalent in parts of China, an early pioneer of the market. No company has been able to break into the UK, however, because of strict laws that classify the electric scooters as motor vehicles requiring drivers’ licenses and subject to tax and insurance. Even then, regulators will not allow scooters because they do not comply with “normal vehicle construction rules.”

Page C124

The scooter industry is experiencing some of the same problems as ride hailing, with aggressive startups butting heads with local governments. But there are key differences. With ride hailing, entrenched taxi industries argued that unregulated startups had an unfair advantage. There is no such incumbent industry opposing scooters. Urban congestion and climate change have also made alternatives to automobiles more popular with city governments.

Vandalism

There have been numerous cases of vandalism reported for shared bikes around the world. Dockless bike-sharing company Gobee bike had to pull out of Paris after 60 percent of the bikes were stolen, vandalized, or “privatized” (the practice of renting the bike on a permanent basis, thereby removing it from the co-sharing space).21 Not long after that, the Hong Kong-based company announced its closure due to losses and high maintenance costs. In the United States, cases of vandalism have been on the rise since companies have been trying to introduce incentives to keep their bikes safe. Washington, DC, witnessed a couple of cases in 2019. Kimberly Lucas, the city’s bike program specialist, told a group of regional transportation officials at a dockless share workshop that companies have told city transportation officials that they have lost up to half of their fleets. This is significant because each company is allowed to operate a maximum of 400 bikes in the city.22 In Arizona, dozens, if not hundreds, of Lime bikes were spotted at a scrapyard just northwest of Phoenix. A company spokesman said the bikes “were damaged beyond repair” and were being recycled. Mary Caroline Pruitt, a spokeswoman for Lime, said the company takes “meaningful steps” to prevent vandalism and theft. “All our bikes and scooters have anti-theft locks and audible alarms that sound if someone tries to tamper with them,” she said. “If we find someone has vandalized one of our products, we do our best to make sure they are held responsible, including working with local authorities when appropriate.”23

While Bird scooters have faced vandalism in San Francisco, Lime experienced trouble when they left several hundred of their scooters on the streets without the permission of municipal authorities. People started acting against the company when they figured out that the scooters were programmed to play the message “Unlock me to ride me, or I’ll call the police” repeatedly, at a high volume, when their controls were touched. These cases, documented on social media and neighborhood blogs, are igniting complaints. As of 2021, Washington, DC, transportation officials say they are allowing each company to have only 500 bikes on the ground so that the number is manageable and bikes do not end up piling on sidewalks, as has been the experience in other cities. Five companies are currently operating, Bird, Helbiz, Lime, Lyft and Spin.24 Critics say that if the city allows more bikes, it could become a larger concern.25

The potential problem with an excessive amount of bikes in the future can be predicted from what has happened in China. A decade ago, a bike-sharing app seemed to be the ideal solution and millions of bikes were poured into China’s streets by the private sector without proper regulations. But today, as the companies fail, unused units pile up in bicycle graveyards, and queues of angry users demand their deposits back.26 Ofo, a Chinese bike-sharing firm, was flushing with cash until it faced a chaotic expansion that resulted in bankruptcies and huge piles of impounded bikes.27 It resulted in hordes of angry customers outside its headquarters demanding refunds.

The Future of Lime

Lime’s ridership did not improve until the summer of 2021, when Covid restrictions began to ease up. With more white-collar workers returning to the workplace and rising gas prices in 2022, the situation seems to be improving for Lime. The number of trips taken in the first three months of 2022 is up 75 percent over the same period last year, bringing the company roughly back to where it was in 2019, though those trips are spread over more cities. By March 2022, Lime had crossed 300 million trips worldwide.28 As the world emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, what is the way ahead for Lime? Will the bike-sharing company adopt the strategy of its closest competitor Bird and go public?

Although Lime is taking on new initiatives to explore and innovate, and while some investors see a promising future for the bike-sharing business, analysts who witnessed the rise and fall of some of the Chinese bike-share companies disagree. These days, people want to use one app where “you can hail a scooter or a bike or a car,” said Tu Le, founder of consulting firm Sino Auto Insights. “That’s where the sweet spot’s going to be.”29

With car-hailing services like Uber and Lyft entering the bike-share market, do startups like Lime and Bird have a future?

Chapter 3

VALUE-CHAIN ANALYSIS

Value-chain analysis views the organization as a sequential process of value-creating activities. The approach is useful for understanding the building blocks of competitive advantage and was described in Michael Porter’s seminal book Competitive Advantage.2 Value is the amount that buyers are willing to pay for what a firm provides them and is measured by total revenue, a reflection of the price a firm’s product commands and the quantity it can sell. A firm is profitable when the value it receives exceeds the total costs involved in creating its product or service. Creating value for buyers that exceeds the costs of production (i.e., margin) is a key concept used in analyzing a firm’s competitive position.

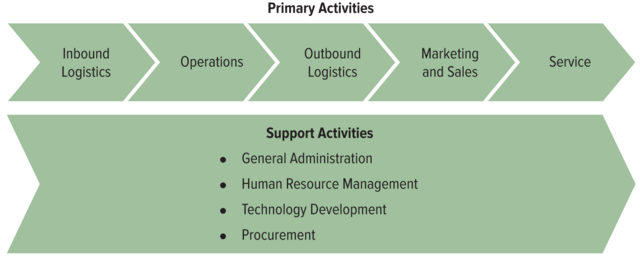

Porter described two different categories of activities. First, five primary activities—inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service—contribute to the physical creation of the product or service, its sale and transfer to the buyer, and its service after the sale. Second, support activities—procurement, technology development, human resource management, and general administration—either add value by themselves or add value through important relationships with both primary activities and other support activities. Exhibit 3.1 illustrates Porter’s value chain.

EXHIBIT 3.1 The Value Chain: Primary and Support Activities

Source: Adapted from Porter, M. E. 1995, 1998. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: Free Press.

To get the most out of value-chain analysis, view the concept in its broadest context, without regard to the boundaries of your own organization. That is, place your organization within a more encompassing value chain that includes your firm’s suppliers, customers, and alliance partners. Thus, in addition to thoroughly understanding how value is created within the organization, be aware of how value is created for other organizations in the overall supply chain or distribution channel.3

Next, we’ll describe and provide examples of each of the primary and support activities. Then we’ll provide examples of how companies add value by means of relationships among activities inside the organization as well as activities outside the organization, such as those activities associated with customers and suppliers.4