Critical Thinking Case Analysis

![]()

W19246

TO BREW OR NOT TO BREW: THE CORKFORD BREWERY ACQUISITION

Brittney MacKinnon wrote this case under the supervision of Mary Gillett and Chris Sturby solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality.

This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) [email protected]; www.iveycases.com. Our goal is to publish materials of the highest quality; submit any errata to [email protected].

Copyright © 2019, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2019-10-03

In the spring of 2017, James MacKinnon was reviewing his latest business opportunity. As the president and co-owner of MacKinnon Industries (MI), MacKinnon was intrigued by the opportunity to both diversify his business lines and bring a former family business back into the MacKinnon family. Beginning in 1990, MacKinnon had built up extensive experience acquiring and managing manufacturing businesses. He now had the opportunity to purchase Corkford Brewery Inc. (Corkford Brewery), including the land, building, and equipment, as well as four successful brands from Tanzer Brewing Company (Tanzer), who owned Corkford Brewery. MacKinnon was very reluctant to pass up this opportunity. He was eager to assess the financial viability of the business venture under three different potential operating scenarios, assess the potential of adding ciders to the product mix, and consider the price that he would be willing to pay to acquire the business.

HISTORY AND BACKGROUND

Corkford Brewery began operations in Corkford, Ontario, in 1870, when a European immigrant and relative of MacKinnon’s started the brewery. For the next 84 years, the MacKinnon family operated Corkford Brewery almost continuously, except from 1922 to 1924, when the brewery was closed during the prohibition period. The brewery was reopened in 1924 and was subsequently modernized. Sales at the brewery continued steadily, with spikes in 1958 and 1968, when beer sales elsewhere in Ontario were temporarily suspended due to striking unionized brewery employees. The brewery changed owners multiple times in the 1980s and 1990s. It was rebuilt and subsequently sold to Tanzer in 1997. The brewery had been a major employer in the small farming community of Corkford for many years. Despite changes in ownership and management, a steadfast commitment to quality and community had always remained the hallmark of the operation. In early 2017, the brewery was listed for sale. The community worried that the brewery would cease operations for good if a new owner could not be not found.

MACKINNON INDUSTRIES

MacKinnon was an active investor, owner, director, and manager of numerous businesses throughout his career. He was primarily involved in manufacturing businesses producing industrial components for

major original equipment manufacturers. He had also been actively involved in numerous start-ups and early-stage companies, where he had served various roles, from advisor to operator. MacKinnon was mainly involved in the operational and strategic side of the businesses in which he invested; his husband, Ian Rockwell, handled the accounting, finance, and data analytics roles. After almost three decades of successful acquisitions, the two men decided to expand their activities and founded MI as a holding company for a portfolio of operating companies.

By 2017, MI operated four manufacturing businesses in Ontario, serving distinct market segments around the world, and employed approximately 200 people. MI’s group of companies delivered industry-leading products in four unique, but related, markets. Although all of the businesses were separate operations, they were all centred around manufacturing and steel, thereby allowing MI to achieve economies of scale in the sourcing of raw materials.

Throughout the nearly 30 years of MacKinnon’s career, he had developed a passion for acquiring family manufacturing businesses. MacKinnon had acquired and sold many such operations and had developed a strong, loyal management team with whom he was able to acquire, grow, and ultimately sell successful businesses. Including MacKinnon and Rockwell, there were five experienced principals in the organization, each with a strong background in manufacturing and steel operations.

MacKinnon spent a great deal of his time seeking out the next opportunity for acquisition. When considering new investment opportunities, he looked for companies that had sustainable and growing earnings and favourable cash flow and that could benefit from MI’s operating management experience. The companies were generally market leaders with a reputation for high quality. Target businesses also had to be generating a healthy return on assets that could be leveraged with prudent levels of debt.

TANZER BREWING COMPANY

Tanzer was an Ontario-based publicly traded company that was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Tanzer produced and distributed beers, ciders, and other bottled alcoholic beverages. All of its production was located in Ontario, and most of its sales occurred within the province. Tanzer’s products were distributed through the Beer Store and the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO). Over the years, as demand for Tanzer’s products grew, the company increased its capacity through acquisitions of existing brewing facilities, such as its purchase of Corkford Brewery. However, after an expansion of a Tanzer facility adjacent to the company’s headquarters was completed, the Corkford site became redundant, and Tanzer listed Corkford Brewery for sale.

THE BEER INDUSTRY

The Brewing Process and Brewmaster

Beer was typically made with barley, a grain that grew in abundance in the area within and surrounding the town of Corkford. The town was located adjacent to a fresh water spring that allowed the brewery to draw fresh water locally for the brewing process. Despite the importance of both the barley and water source, the brewmaster was the true key to success. The brewmaster was responsible for creating the recipe and combining the malted barley with hops, yeast, and water in the perfect ratio and at the ideal temperature to make beer.1 The success of the brewery was very much dependent on the ability of the

1 “How Beer Is Made,” Beer Canada, accessed September 11, 2018, https://beercanada.com/beer-101/how-beer-made.

brewmaster to not only create an excellent beer but to do so consistently, batch after batch. There were only three brewmaster college programs in Canada where students were taught the complicated science of beer making.2 Corkford Brewery was lucky to have had the same brewmaster for quite some time, as this had resulted in a consistent and reliable product. Interestingly, long before the current brewmaster joined Corkford Brewery, MacKinnon’s great grandfather had once been the brewmaster at the Corkford site.

Beer Industry Segments

The beer industry in Ontario traditionally had three market segments, based on the price and quality of the beer: value beer, mid-priced domestic beer, and premium beer. The value beer (lowest-priced segment) consumed in Ontario was generally made within the province or North America. It was made with lower quality raw materials and sold at a lower price. The minimum price for the majority of value beers was regulated by the government.3 Mid-priced domestic beer was made within Canada and was priced between the value and premium brands. With annual increases of the minimum price, the price points of value brands and mid-priced brands were coming closer together, thus increasing competition within both groups. Premium beer was typically made locally or internationally and came with a higher price point.

Craft beer had more recently emerged as a new segment in the industry, often with higher prices and higher quality than even premium beers. Craft beer was locally brewed in limited quantities with unique flavours, usually by smaller independent breweries. Craft beer brought significant innovation in recipes to the beer industry with the introduction of novel ingredients and brewing processes.4 In 2016–17, the LCBO reported only a 0.6 per cent increase in traditional beer sales but a 27.6 per cent increase in the sales of craft beers.5 Sales in the value brands also continued to be strong, whereas mid-priced beer sales declined.6

Regulation and Distribution

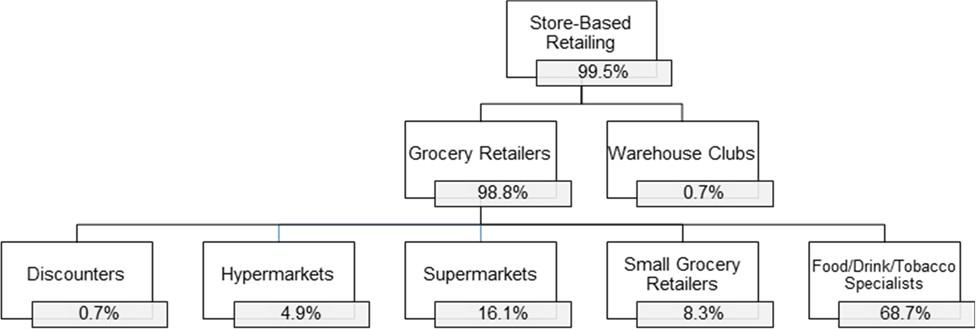

The beer market was heavily regulated both by federal and provincial bodies, including the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Health Canada.7 Regulations at the federal level changed frequently in regard to labelling and marketing restrictions, creating challenges for breweries.8 Regulations at the provincial level affected distribution channels for beer sales. For example, beer could be sold in Ontario at the Beer Store, the LCBO, selected grocery stores, the brewery’s own site, and bars and restaurants (see Exhibit 1).

Market Size and Market Share

The Canadian beer market was projected to grow at an annual rate of 3.2 per cent from 2013 through 2018. However, industry growth was forecasted to slow through to 2023, as the craft beer market was

2 “Rare Brewmaster Program Lures People from Around the World to Small Alberta Town of Olds,” Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, accessed September 9, 2018, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/olds-college-brewmaster-program-1.4465618.

3 Brick Brewing Co. Limited, Condensed Interim Financial Statements, accessed September 9, 2018, https://investorrelations.waterloobrewing.com/sites/waterloobrewinv/files/interim_financial_statements_-_english_q2.pdf.

4 Mike Pomranz, “Does Craft Beer Have Any Room Left for Innovation?,” Food & Wine, September 14, 2017, accessed September 14, 2018, www.foodandwine.com/articles/does-craft-beer-have-any-room-left-innovation.

5 Liquor Control Board of Ontario, Transforming for the Future: LCBO Annual Report 2016–17, accessed September 12, 2018, www.lcbo.com/content/dam/lcbo/corporate-pages/about/pdf/LCBO_AR16-17-english.pdf.

6 “Big Rock Brewery, Inc.: Consumer Packaged Goods—Company Profile, SWOT & Financial Analysis,” The Drinks Business, accessed January 10, 2019, www.thedrinksbusiness.com/dbreport/big-rock-brewery-inc-consumer-packaged- goods-company-profile-swot-financial-analysis.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

expected to become saturated with microbreweries, causing consumers to continue to shift focus away from traditional light and premium beer brands.9 Market share in the beer industry was still dominated by the historic mega-brewers Anheuser-Busch InBev and Molson Coors. However, the emergence of craft and microbreweries had shifted some market share away from these large breweries. In 2017, there were over 80 craft breweries in Ontario.10 With new breweries sharing a limited portion of the industry’s market share, it was nearly impossible to capture a major portion of the Ontario beer industry (see Exhibit 2). Craft breweries had to compete on quality, new product offerings, brewery service, branding, marketing and advertising, and price.

MacKinnon was familiar with two significant craft beer competitors: Brick Brewing Co. Ltd. (Brick) and Big Rock Brewery Inc. (Big Rock). Located in Waterloo, Ontario, Brick operated a craft beer branch and competed in the value beer segment with its most successful brand, Laker.11 Brick was a publicly traded company that was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Big Rock, another publicly traded brewery, produced premium craft beers and other alcoholic products. Headquartered in Calgary, Alberta,12 Big Rock sold its products across Canada and exported some products to South Korea (see Exhibit 3).

Contract Brewing

Unlike mainstream beers, craft beers were highly susceptible to seasonal fluctuations, with most sales occurring from May to October.13 To smooth out the seasonality effect and to achieve maximum capacity, many craft breweries relied on contract brewing, where larger breweries would rent out space to smaller, and often less established, breweries on a contract basis. The smaller breweries completed the full brewing process, including bottling, packaging, and storing at the larger brewery’s facility. MacKinnon estimated that contract brewing in Ontario was priced at approximately CA$12014 per hectolitre (hl), or 100 litres. The customer (i.e., the smaller brewery) typically provided all raw materials except water, along with the recipe and packaging. The customer was also responsible for fees to Brewers Retail Inc. The contract brewer essentially provided the labour and facility capacity.

CORKFORD BREWERY

Corkford Brewery was one of Ontario’s oldest breweries. Located on approximately 8 hectares (20 acres) of land, it had the capacity to produce 50,000 hl of beer per year. There were three wells on the brewery’s site that provided access to high quality spring water, which was used in the brewing process, for the minimal cost of extraction of the water (rather than accessing the town’s water).

Tanzer brewed four different brands of beer at the Corkford Brewery site, all of which competed in the craft beer segment of the industry. Each brand was sold in cases of 24 beers exclusively through the Beer Store. Corkford Original Lager was Corkford Brewery’s first recipe, made with Corkford’s barley malt. Corkford Amber Ale was a pale ale brewed with amber malt, which gave the beer a light copper colour.

9 Lucie Couillard, Breweries in Canada: IBISWorld Industry Report 31212CA, October 2018, accessed January 10, 2019, www.ibisworld.ca/reports/reportdownload.aspx?cid=124&rtid=101.

10 “About Ontario Craft Brewers,” Ontario Craft Brewers, accessed September 14, 2018, www.ontariocraftbrewers.com

/About.html.

11 2017 Annual Report for Brick Brewing Co. Limited, Waterloo Brewing, accessed January 10, 2019, https://investorrelations.waterloobrewing.com/sites/waterloobrewinv/files/sbb0543_01_annual_report_pages_lr[4].pdf.

12 “Big Rock Brewery, Inc.: Consumer Packaged Goods—Company Profile, SWOT & Financial Analysis,” op. cit.

13 Brick Brewing Company: Condensed Interim Financial Statements, Waterloo Brewing, accessed September 9, 2018, https://investorrelations.waterloobrewing.com/sites/waterloobrewinv/files/interim_financial_statements_-_english_q2.pdf.

14 All currency amounts are in CA$ unless otherwise specified.

Corkford Lime was a blonde brew with a squeeze of lime flavour. Corkford Platinum Light had less than 70 calories and was low in carbohydrates, sugar, and fat content. It had a dark colour and a strong flavour. Total production of the four brands was 5,000 hl per year (see Exhibit 4).

Tanzer’s remaining capacity was used to brew some of the company’s other brands. After the sale of Corkford Brewery, Tanzer intended to relocate 45,000 hl in contract brewing to its own facilities. Most of the 18 workers the company employed at Corkford Brewery had been with the brewery for many years and were expected to remain after the sale. The workers were non-unionized, local, and took great pride in their contribution to the brewery and community. The staff consisted of the brewmaster; an operations supervisor; 13 production workers, including four in blending and brewing and nine in packaging; two maintenance workers; and a quality control employee. The production staff worked 35 hours per week at an average hourly rate of $18.50. The workers were fully employed 48 weeks per year thanks to the contract brewing business that Tanzer ran at the brewery. These workers were considered casual, employed only when production work was available. However, to ensure availability of labour, Tanzer had always guaranteed a minimum of 30 weeks of work to these employees. The operations supervisor was paid an annual salary of

$40,000; maintenance and quality control staff were each paid $35,000 per year.

Tanzer centrally managed all other administrative functions such as finance, human resources, and marketing. MacKinnon assumed that, after the acquisition, he would have to spend $250,000 per year to provide these functions at Corkford Brewery.

The brewmaster had been with Corkford Brewery for 26 years. Her experience launching new products had been invaluable, with the diversified product offerings of previous owners. She had a strong track record of leading the other employees, improving quality, reducing costs, and increasing output. As a result of her experience, the Corkford Brewery brewmaster was paid $45,000, an amount close to the upper end of the range for the craft beer industry.

Waste water was managed under an agreement with the township of Corkford, for which the brewery paid a flat fee of $25,000 per year. In addition, ongoing maintenance of the building and equipment averaged

$100,000 per year. Miscellaneous overhead expenses, including power, utilities, and minor supplies, was estimated at $200,000 per year. Delivery of non-contract product was provided by an external provider at a specific rate per hl. Tanzer arranged for the pickup and delivery of its other brands brewed at Corkford Brewery.

CONSIDERING THE ACQUISITION

MacKinnon sat down to review the data provided by Tanzer regarding costs associated with operating Corkford Brewery (see Exhibit 5). MacKinnon had three options to consider regarding operating the facility and generating returns, including the expected return on assets of each option. He also knew that any future decisions regarding the brewery’s business model would affect the amount that he would be willing to pay for the brewery.

The first option MacKinnon considered was to continue the production of only the four Corkford Brewery brands. Despite the LCBO’s report of nearly 28 per cent growth for the craft beer industry, he expected the next year’s sales to remain unchanged from the current year. He also knew that he lacked Tanzer’s supply chain power, so he expected that he would pay 25 per cent more for raw materials.

The second option MacKinnon considered was also based on existing brands. He was convinced that by focusing all production and marketing attention on only two of the existing brands, he could still achieve a total sales volume of 5,000 hl, split evenly between the two brands. However, he was unsure how to select which two brands to pursue.

The third option MacKinnon considered involved the four brands plus some contract brewing. He was intrigued by the idea of using some of the brewery’s capacity by securing brewing contracts. MacKinnon knew that Corkford Brewery would have significant excess capacity, given that Tanzer planned to move its contract brewing work to other facilities after the brewery’s sale. MacKinnon was anxious to get started building business connections, but he wondered if he could generate a healthy profit at the industry rate of $120 per hl for contract brewing.

MacKinnon estimated that he could realistically secure 10,000 hl worth of contract brewing, in addition to the four Corkford Brewery brands, but that administrative costs would likely increase by $200,000. Any contract brewing customer would be expected to have steady volume throughout the year and payment terms would be 60 days. Corkford Brewery would have to cover federal excise taxes and delivery fees but would not have to pay Brewers Retail Inc. fees related to this product or stock any inventories.

Without any contract brewing business, Corkford Brewery’s total assets consisted of $1.5 million in working capital and $5 million in property, plant, and equipment. If the brewery only produced Corkford Brewery brands, without contract brewing, the brewery could have excess equipment to sell for approximately $2 million.

As an additional and independent consideration, MacKinnon knew that ciders were becoming very popular but would require investing in specific types of equipment for the facility. He was reasonably confident that he could sell 500 hl of cider at the same contribution as Corkford Original Lager, and he expected that no further changes would be required in the plant. The equipment would cost $1.25 million, it would have a useful life of 10 years, and it could qualify for the very lucrative 50 per cent capital cost allowance rate. Any increased profits would be taxed at the expected corporate rate of 25 per cent. Regardless of his production assumptions, MacKinnon wanted to consider whether the equipment investment made sense.

Finally, MacKinnon considered how much he would potentially bid for the brewery. He knew he would have to negotiate a purchase price with Tanzer and that the three options would each lead to a different valuation of the brewery. He wanted to understand the range of values before he sat down with Tanzer’s negotiating team. As a starting point, he wanted to value the business assuming that the following year’s cash flows would be realized in perpetuity, with an expected 2–3 per cent growth rate.

MacKinnon was unsure if this was the best way to diversify his current business, but he was drawn by the family connection and his enjoyment of beer. He wanted to be sure he was making a sound business decision and that it would generate the 10 per cent post-tax returns that he required from all his investments. MacKinnon opened up a cold bottle of Corkford Original Lager and settled in to consider his options.

EXHIBIT 1: DISTRIBUTION OF BEER IN CANADA IN 2017

Note: The remaining 0.5 per cent of the market is Internet-based retailing.

Source: Created by the case authors using data from Euromonitor International, “Beer in Canada,” Passport, accessed January 10, 2019.

EXHIBIT 2: MARKET SHARE

Canadian Beer Retail Market Share by Volume (%)

| Company | 2016 | 2017 |

| Anheuser-Busch InBev | 47.3 | 47.2 |

| Molson Coors Canada Inc. | 36.3 | 36.1 |

| Others | 16.4 | 16.7 |

Canadian Beer Retail Market Share by Value (%)

| Company | 2016 | 2017 |

| Anheuser-Busch InBev | 45.3 | 44.8 |

| Molson Coors Canada Inc. | 38.0 | 37.3 |

| Others | 16.8 | 17.9 |

Source: Created by the case authors using data from Mintel Market Sizes, “Beer in Canada 2017,” accessed January 10, 2019.

EXHIBIT 3: SELECT COMPETITOR INFORMATION (CA$)

| Brick Brewing Co Ltd. | Big Rock Brewery Inc. | ||||||||||||

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | ||||||||

| Profitability | |||||||||||||

| Gross margin | 34.78% | 28.01% | 28.06% | 40.58% | 43.24% | 44.88% | |||||||

| Profit margin | 5.23% | 8.85% | 4.24% | -2.19% | -1.05% | -2.72% | |||||||

| Return on assets | 4.56% | 7.64% | 3.40% | -1.90% | -0.85% | -2.16% | |||||||

| Return on equity | 6.84% | 10.90% | 4.56% | -2.75% | -1.21% | -2.83% | |||||||

| Capacity | |||||||||||||

| Total debt/equity (x:1) | 0.213 | 0.086 | 0.078 | 0.115 | 0.237 | 0.036 | |||||||

| Cash Flow ($ millions) | |||||||||||||

| Cash from operations | 10.490 | 2.281 | 9.768 | 1.414 | 3.543 | 2.103 | |||||||

| Cash from investing | (4.768) | (6.733) | (5.185) | 0.398 | (7.584) | (6.808) | |||||||

| Cash from financing | (3.052) | 1.620 | (2.144) | (1.851) | 3.708 | 3.761 | |||||||

Source: Created by the case authors using data from YCharts, accessed January 10, 2019.

EXHIBIT 4: CORKFORD BREWERY BRANDS, VOLUMES AND SELLING PRICE DETAILS (CA$)

| Corkford Original Lager | Corkford Amber Ale | Corkford Lime | Corkford Platinum Light | |

| Volume produced (in hectolitres) | 2,000 | 1,000 | 750 | 1,250 |

| Cases per hectolitre | 12.6 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 12.6 |

| Volume produced (24-bottle cases) | 25,200 | 12,600 | 9,450 | 15,750 |

| Wholesale selling price per case | $ 39.60 | $ 44.40 | $ 44.40 | $ 40.80 |

Source: Company files.

EXHIBIT 5: TANZER’S CURRENT UNIT COST (PER HECTOLITRE) FOR THE CORKFORD BREWERY OPERATION (CA$)

Unit Cost (per hectolitre)—Assumes volume of 50,000 hectolitres

| Corkford Original Lager | Corkford Amber Ale | Corkford Lime | Corkford Platinum Light | Tanzer Product | |

| Raw material (ingredients, water, bottles, packaging) | $ 94.500 | $ 97.650 | $ 98.280 | $ 91.350 | $ 10.000 |

| Direct labour | 8.081 | 8.081 | 8.081 | 8.081 | 8.081 |

| Indirect labour | 3.800 | 3.800 | 3.800 | 3.800 | 3.800 |

| Overhead (waste water, maintenance, etc.) | 6.500 | 6.500 | 6.500 | 6.500 | 6.500 |

| Federal excise tax | 22.288 | 22.288 | 22.288 | 22.288 | 22.288 |

| BRI fees | 42.780 | 42.780 | 42.780 | 42.780 | |

| Delivery | 18.000 | 18.000 | 18.000 | 18.000 | |

| $ 195.849 | $ 198.999 | $ 199.629 | $ 192.699 | $ 50.569 |

Notes:

Federal excise tax is charged to brewers on a sliding scale as follows: Volume Produced Tax per hl

0 to 5,000 hl $6.368 per hl

5,000 to 50,000 hl $22.288 per hl (rate applicable to ALL volume, including first 5,000 hl)

BRI fees are paid to the Beer Store as a “stocking charge” at the rate of $42.78 per hl.

Note: hl = hectolitre; BRI = Brewers Retail Inc. Source: Company files.