Annotated Bib. - Part 3 - Add five references to your annotated bibliography and submit to Canvas. Follow the sample annotated bibliography. full page per annotated bib

Wilson, A., & Pearson, R. (1993). The Problem of Teacher Shortages. Education Economics, 1(1), 69–75.

Title:

The problem of teacher shortages.

Authors:

Wilson, Andrew

Pearson, Richard

Source:

Education Economics. 1993, Vol. 1 Issue 1, p69. 7p. 3 Graphs.

Document Type:

Article

Subject Terms:

Supply & demand of teachers

Geographic Terms:

United Kingdom

Abstract:

Examines the demand for teachers in the United Kingdom and establishes the factors which determine teacher shortages. Number of teachers; Used data on teacher shortages and vacancy rates; How teachers can enter the active teaching workforce; Initiatives to reduce teacher shortages; Trends on the demand for teachers.

Full Text Word Count:

3127

ISSN:

0964-5292

DOI:

10.1080/09645299300000009

Accession Number:

9707171931

THE PROBLEM OF TEACHER SHORTAGES

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the demand for teachers in the UK and establishes the factors which determine teacher shortages. Policy options aimed at alleviating these shortages are suggested.

Introduction

Given the rising public interest in, and concern about, the quality of our education system, it is not surprising that reports about teacher shortages regularly hit the headlines. The purpose of this paper is to look at the extent of teacher shortages in England and Wales, and what can be done to minimize any future difficulties.

Numbers of Teachers

Teachers are a major professional group in the labour market. In 1991 there were 442 100 teachers (measured as full-time equivalents) employed by Local Authorities (LEAs) and grant-maintained schools in England and Wales. Just under two-thirds were women. The teachers were split almost evenly between the primary and secondary sectors. In addition there were almost as many qualified teachers in the population who were not currently employed in teaching (over 350 000 in 1986 of whom nearly two-thirds were women). Further details are given in Figure 1 and Appendix 1.

Teacher Shortages

It is hard to define what constitutes a shortage and difficult to collect relevant data. The most readily available and widely used data on teacher shortages are those on vacancy rates produced by the Department For Education (DFE) each January for England. The figures do not, however, take account of `hidden' or `suppressed' shortages, whereby staff without relevant qualifications teach specialist subjects and in this respect they tend to underestimate the problem. Conversely they also include vacancies which are part of `normal' turnover and in this respect the figures may over estimate the problem (see Appendix 2).

The vacancy rate has fluctuated somewhat in recent years, reaching a peak level of 1.8% in 1990, up from 1.2% in 1988. Since 1990 it has fallen back to 1.5% in 1991 and is believed to have fallen further in 1992 because of the recession. Vacancy rates have traditionally been higher in the primary and nursery sector (2.1% in 1991) than in the secondary sector (1.5% in 1991). There are also marked differences between different parts of the country; Greater London was in the worst position with a vacancy rate of 5.3% in 1990, and within it the Inner London area had an even higher vacancy rate. By contrast the Northern region had a vacancy rate of 0.6% in 1990 and the East Midlands a rate of 0.9%.

Within secondary schools, there are significant variations across subjects, the highest rates being in music, languages and careers teaching. However, languages account for the highest proportion of all vacancies (at 16%), followed by the sciences (14%), English (13%) and mathematics (9%). The lowest rates are in biology and home economics.

In 1988, the latest year for which data are available, 20% of tuition in secondary schools was undertaken by teachers without specialist qualifications in the subject they were required to teach. This is a `hidden shortage' or `mismatch'. This `mismatch' varied widely across subjects, with low levels in chemistry (5%), biology (6%), physics, French, geography and music (all at 8%). Much higher rates of mismatch occurred in computer studies (56%), business studies (37%) and craft, design and technology (35%). However, for virtually all subjects, the degree of mismatch was lower among the older pupil age groups. For example, while mathematics had a mismatch of 15% in years 7-9 (11-14 year olds), it fell steadily to only 2% in year 12 (the sixth form). Several other subjects also have had very low levels of mismatch in the sixth form: geography, history, biology, chemistry, physics English and French (all under 5%).

It can be seen that the available data on shortages show that the problems of unfilled vacancies are focused in certain subjects and locations. There is also a significant proportion of secondary teaching that is being carried out by those lacking the relevant subject qualifications. While these shortages have eased over the last 2 years, it is not clear how much of this improvement is due to factors beyond the recession and lack of alternative jobs.

Looking ahead, the extent to which shortages become easier or get worse depends on the flows into and out of teaching. These are considered next.

The Flows into Teaching

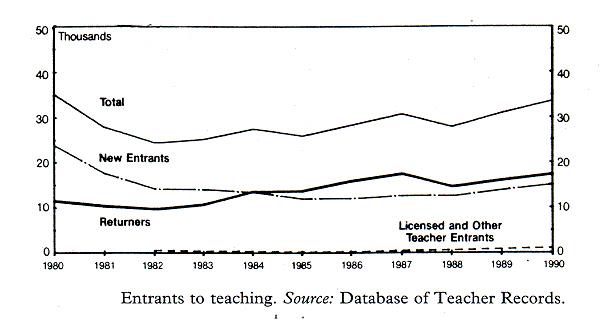

Teachers can enter the active teaching workforce through three main routes (see Figure 2).

New Entrants

Traditionally, new entrants come from teacher training courses at universities, colleges and polytechnics leading to either the degree of Bachelor of Education (BEd; or BA/BSc with Qualified Teacher Status) or a 1-year Postgraduate Certificate of Education (PGCE). These are now being supplemented by the 2-year, school-based PGCE or `articled teacher' scheme which is targeted at young graduates and received its first intake in 1990. In 1986, bursaries were introduced to attract entrants to training in `shortage' subjects and, while they had the initial effect of increasing entrant numbers, they do not seem since to have added a further boost to the already rising numbers.

Over the last decade the numbers of newly qualifying teachers have fluctuated between 12 000 and 15 000 each year. Numbers are, however, set to grow in the coming years as applications and acceptances for BEd and PGCE courses have shown rapid growth, with a 50% increases in intakes between 1987 and 1991.

Some 13 000 students started BEd courses and 15 000 PGCE courses in 1991. Applicants for places on courses starting in 1992 are up by a further 50%, big rises occurring across all the subject areas, including the perceived areas of shortage such as mathematics, the sciences and modern languages. This growth has been fuelled in part by the recession and the sharp downturn in the number of altenative job opportunities open to graduates.

Within these rising totals there is a rising proportion of `mature' students, who were aged 26 or over when they started their course. Mature students accounted for 35% of the intakes in 1990, up from under 30% in 1987.

These figures tell only part of the story. It is also necessary to take into account wastage from training. In 1991, 13% of PGCE entrants and 22% of BEd entrants did not complete their training. In addition, only around 75% of the students who qualify normally go on to enter some form of teaching within a year of qualifying, with a further 10% entering after a gap of more than one. Finally it is important to note that not all those qualifying are able to find what they regard as appropriate teaching jobs. Some 3% were still unemployed 6 months after qualifying in 1990.

Re-entrants

Re-entrants or qualified returners are the other major source of entrants to the active teaching workforce. The numbers have grown by over 50% in the last decade to total over 17 000 in 1990. Qualified returners accounted for over half the overall intake to teaching in 1990. They include men and women returning after a career break, after ill health or from other employment. The majority are women returning to primary school teaching.

Among the 350 000 currently inactive teachers, nearly one in five definitely intend to return while another 40% would consider returning, so that there is a large pool of potential returners for the future (see Appendix 1).

Licensed Teachers and Other Entrants

This is the path to Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) for those who have been trained as teachers in a country other than England and Wales, or who are unqualified but experienced teachers from the independent sector. Licensed teacher status can also be granted to anyone who is over 26 years of age. Licensed teachers have to have completed successfully at least 2 years full-time higher education in England or Wales and to have undertaken a period of training in a school accompanied by a programme of teacher education for a period ranging from one term to two years, depending on previous experience. In 1987 such entrants accounted for less than 4%, of the total inflow into the profession. However, the recent extension of licensed teacher status to those with no teaching experience might well increase the importance of this entry route.

Overall, then, the supply of new teachers is currently growing fast, although much of the recent growth is probably due to the recession. It is also noticeable that recruits, comprising both new entrants and re-entrants, are increasing mature students or adults and that there is a large pool of inactive teachers who provide a significant potential resource available to the education system. This contrasts with the traditional image of a profession fed by `young graduates' only.

Flows out of Teaching

On the face of it the numbers leaving the profession annually are high. The proportion of qualified teachers leaving rose from 7.8% in 1988 to almost 10% in 1990, although the figure has fallen back again in the last year. The crude figures can however be misleading, as retirement and early retirement accounted for over half (58%) of the teachers leaving the profession in 1990. Only one in six of the leavers left teaching for alternative employment outside education, and about 7% of leavers left to start a family or look after young children. The destinations of the other 18% of leavers were unknown. To put these figures in perspective, only 3160 teachers were known to have left in 1990 to take up work outside teaching, a total that had risen from 2560 three years earlier. The number of retirements due to ill health had however doubled over this period to total 3290 in 1990.

There is little information available about the motivation of teachers and their reasons for staying in or leaving teaching. A recent pilot survey did however show that teachers were motivated by inherent `job satisfaction', `good relations with pupils', `being rewarded fairly' and `working in a well managed school', and that up to a third had poor experiences of these factors (see also Appendix 1).

As well as flows out of teaching it is also important to consider the turnover of teachers within the profession (i.e. those teachers who resign to move to other teaching posts), since this also represents a potential disruption in pupils' education. Teacher turnover stood at 13.1% in 1990. There were significant regional variations. The turnover rate amongst teachers in secondary schools in Greater London was 17.4% and that in the South East (excluding London) was 15.0%. Both these figures represent a slight fall in the turnover rate for 1990, following increases in the previous 2 years. The turnover rate amongst newly appointed teachers in London was even higher; 24% of newly qualified teachers moved within 2 years, and 42% within 5 years.

Alleviating Shortages

Various initiatives have been undertaken, or proposed, to reduce teacher shortages. These include:

Nationally widening access through the introduction of more flexible training courses, especially part-time training opportunities and shortened BEd or PGCE courses. The `licensed' and the `articled' teacher schemes are currently growing sources of new entrants. Such flexibility is particularly attractive to mature entrants.

Bursary payments for trainees in shortage subjects. While such payments have had an initial effect on recruitment it seems that such effects may not be long-lasting.

The promotion of teaching through the Teaching as a Second Career (TASC) unit, which runs regular national advertising and publicity campaigns competing directly with the efforts of graduate recruiters in other sectors.

Locally, in some LEAs and individual schools, the introduction of more flexible working arrangements, including part-time jobs, job-sharing, career breaks and creche facilities. These would particularly benefit women teachers and might not only encourage ax-teachers to return (see Appendix 1), but could also have benefits in terms of retaining teachers currently in service.

Retraining which helps to reduce the problems of mismatch and hidden shortages.

Re-examining teacher workloads and the amount of time spent on administrative activities. Recent research shows that on average only about half of teachers' time is devoted to direct teaching and lesson preparation. Administrative and other duties take up the largest part of teachers' time and many of those activities might potentially be delegated to support staff.

Reviewing pay and reward structures and levels in order to attract teachers in shortage subjects and locations. This is a very controversial area. Opponents of differential pay say that it would be divisive, that shortage subjects change over time and that differentiated salaries could prove to be insensitive to such changes.

The Department For Education, LEAs and schools need to continue with and develop initiatives of the kinds to minimize future shortages. Some of these policies, initiated by LEAs, may however be much harder to extend or implement when schools are locally managed or grant-maintained. It is also important that the effect of initiatives should be carefully assessed from the point of view both of their overall impact and of the extent of the `additionality', i.e. the extent whereby to which additional teaching resources result as distinct from an effect whereby a `solution' simply redistributes teachers and creates a problem elsewhere. Moreover, it is also essential to monitor effects on quality as well as quantity.

Future Trends

Looking ahead, the school population is projected to grow by over 12% over the next decade, generating a demand for more teachers. At an operational level, changes in school management, most notably local management of schools and `opting out' will also influence the demand for teachers. While subject provision is now largely determined by the National Curriculum, the balance of staffing within subjects will still be determined locally. The key determinant of the demand for teachers will, however, be the level of funding allocated to education.

In 1990 the DFE produced an assessment of future supply and demand trends. The department used demographic data together with a `high demand' scenario based on current class sizes (with average pupil teacher ratios of 17:1), and a `low demand' scenario based on class sizes 10% larger. The figures suggest that on the supply trends prevailing in 1990, shortages would worsen over the period to 1997 unless class sizes grew, while if there were improvements on the supply side there would be no worsening of existing shortages at current class sizes. The department did not however provide an assessment based on an assumption of smaller class sizes. Such a development would lead to a worsening of the gap between supply and demand. The DFE report also provided supplementary data relating to individual subjects.

It is clear that schools will require more teachers in the coming years. Given that the decade started with shortages, improvements will be required both in making full use of existing and inactive teachers and in the supply of new entrants, if shortages are to be minimized and the education system is to function satisfactorily.

Figure 1. How many teachers are there? Source: Database of Teacher Records.

ACTIVE 442 100 Full-Time Equivalents Primary Full-Time 40.4% Secondary Full-Time 42.4% Other 8.1% Primary Part-Time 5.1% Secondary Part-Time 4.0% INACTIVE More than 350 000 Qualified Teachers WOMEN Primary 36.0% WOMEN Secondary 37.0% MEN Primary 5.0% MEN Secondary 22.0%

: Figure 2. Entrants to teaching. Source: Database of Teacher Records.

: Figure 2. Entrants to teaching. Source: Database of Teacher Records.

Appendix 1: The Pool of Inactive Teachers

There are over 350 000 qualified teachers who are not currently working as teachers. A 1991 survey of out-of-service teachers showed that 17% of those not currently teaching definitely intended to return to teaching while 41% would consider returning tO teaching. This suggests there is a pool of up to 60 000 people prepared and willing toe return to teaching.

The `definite' returners were more likely to be women in their 30s with young families who intended to return once their children are older. Over half of this group had more than 5 years teaching experience, this experience being fairly evenly split between the primary and secondary sectors.

This characterization fits in with the reasons given for leaving teaching, the most common being to `raise a family' (cited by 28%). Other reasons were `dissatisfaction with teaching--other than financial reasons' (24%) and `to take up other employment' (17%). Only 5% of the sample suggested that their main reason for leaving was to do with pay.

When all those who were undecided or definitely against returning to teaching were asked for their reasons for not wanting to return, the most frequently cited reason was `prefer current employment' (33%) followed by `dissatisfaction with teaching--other than financial reasons' (27%). Only 8% cited pay as the main factor.

When possible returners were asked what factors would encourage them back into teaching, the most popular measure was the `availability of part-time work, more flexible hours and `job-shares' (25% of respondents) and `better pay generally' (14%). `Refresher courses' and `opportunities to reacquaint with life in the classroom' were each cited by 10% The conclusion was that `pay is a factor influencing decisions on re-entering teaching, but is rarely regarded as the most important factor'.

Appendix 2: What is a Shortage?

There is no clear, universally agreed measure of what actually constitutes a shortage in relation to a given number of teaching posts.

In practice three potential measures can be considered; there are `vacancy rates', `hidden shortages' and `suppressed shortages'. Issues of teacher shortages also have a qualitative aspect (how many teachers are required?) and a qualitative aspect (are the available teachers appropriate for the posts that exist?).

Vacancy Rates

The simplest measure is the number of unfilled vacancies for teachers. However, such a measure is not necessarily reliable. Very few vacancies cannot be filled in some way (perhaps by temporary staff, supply teachers or those not fully qualified for the particular post). Quality is therefore an issue (see also `hidden shortages' below). Second, it is possible that some schools might not create vacancies for staff if they are convinced that a particular post will not be filled by a teacher with the appropriate skills and abilities. Finally, vacancies are a normal part of the process by which any organization recruits staff and makes appointments. What is of greater interest is the number of `difficult to fill vacancies or those which have been `unfilled' for a significant period of time, but data of this kind are not readily available.

Hidden Shortages (or Mismatch)

Hidden shortages are said to exist when teaching is carried out by someone who is not qualified to teach the subject. It is often referred to as a `mismatch' and is usually measured either as the proportion of teachers teaching a subject in which they are not qualified, or as the proportion of tuition provided by such teachers.

Suppressed Shortages

Suppressed shortages occur when tuition in certain subjects is reduced, or subjects are simply not taught at all, because the appropriate staff are not available.