Juvenile Justice System Paper

An Overview of Juvenile Justice in the United States

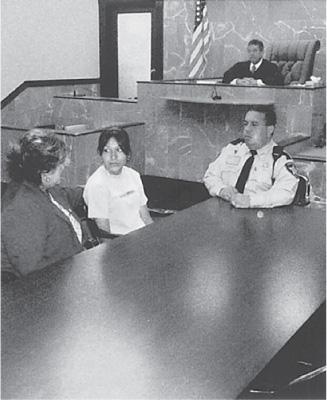

(HO/AFP/Getty Images/Newscom)

Learning objectives

AFTER READING THIS CHAPTER, THE STUDENT WILL BE ABLE TO:

Explain the concept of parens patriae.

Differentiate between the types of juvenile offenders, including delinquents and status offenders.

Explain the structure of the juvenile justice system and the roles and functions of various juvenile justice agencies.

Summarize how juvenile offenders are processed through the criminal justice system.

Understand the meaning of the deinstitutionalization of status offenders.

Introduction

The juvenile justice system is unique. This book explains the system and how it has evolved. The organization of this chapter is as follows: First, the juvenile justice system is described. Certain features of juvenile justice are similar in all states. Various professionals work with youth, and they represent both public and private agencies and organizations. From police officers to counselors, professionals endeavor to improve the lives of youth.

Every jurisdiction has its own criteria for determining who juveniles are and whether they are under the jurisdiction of the juvenile court. A majority of states classify juveniles as youth who range in age from 7 to 17 years, and juvenile courts in these states have jurisdiction over these youth. Some states have no minimum-age provisions and consider each case on its own merits, regardless of the age of the juvenile.

Because juveniles are not considered adults and, therefore, fully responsible for some of their actions, special laws have been established that pertain only to them. Thus, violations specific to juveniles are referred to as status offenses. Juveniles who commit such infractions are categorized as status offenders. Juveniles who engage in acts that are categorized as crimes are juvenile delinquents, and their actions are labeled juvenile delinquency. In brief, delinquent acts for youth would be crimes if committed by adults. By contrast, status offenses are not considered crimes if adults engage in them. Examples of status offenses include runaway behavior, truancy, unruly behavior, and curfew violation. The characteristics of youth involved in such behaviors will also be described.

In 1974, the U.S. Congress enacted the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA). This act, although not binding on the states, encouraged all states to remove their status offenders from secure institutions—namely secure juvenile residential or custodial facilities—where they were being held. States subsequently removed status offenders from institutions and placed these youth with community, social service, or welfare agencies. This process is called the deinstitutionalization of status offenses (DSO) and will be described in some detail.

Next, a general overview of the juvenile justice system is presented. While later chapters will focus upon each of these components in greater detail, the juvenile justice system consists of the processes involved whenever juveniles come in contact with law enforcement. Several parallels exist between the criminal and juvenile justice systems. For those juveniles who advance further into the system, prosecutors make decisions about which cases to pursue. The prosecutors’ decisions are often preceded by petitions from different parties requesting a formal juvenile court proceeding. These youth have their cases adjudicated. Compared to criminal court judges, however, juvenile court judges have a more limited range of sanctions. Juvenile court judges may impose nominal, conditional, or custodial dispositions. These dispositions will be described more fully in the following sections.

The Juvenile Justice System

The juvenile justice system, similar to criminal justice, consists of a network of agencies, institutions, organizations, and personnel that process juvenile offenders. This network is made up of law enforcement agencies, also known as law enforcement; prosecution and the courts; corrections, probation, and parole services; and public and private programs that provide youth with diverse services.

The concept of juvenile justice has different meanings for individual states and for the federal government. No single, nationwide juvenile court system exists. Instead, there are 51 systems, including the District of Columbia, and most are divided into local systems delivered through either juvenile or family courts at the county level, local probation offices, state correctional agencies, and private service providers. Historically, however, these systems have a common set of core principles that distinguish them from criminal courts for adult offenders, including (1) limited jurisdiction (up to age 18 in most states); (2) informal proceedings; (3) focus on offenders, not their offenses; (4) indeterminate sentences; and (5) confidentiality (Feld, 2007).

When referring to juvenile justice, the terms process and system are used. The “system” connotation refers to a condition of homeostasis, equilibrium, or balance among the various components of the system. By contrast, “process” focuses on the different actions and contributions of each component in dealing with juvenile offenders at various stages of the processing through the juvenile justice system. A “system” also suggests coordination among elements in an efficient production process; however, communication and coordination among juvenile agencies, organizations, and personnel in the juvenile justice system may be inadequate or limited (Congressional Research Office, 2007).

In addition, different criteria are used to define juveniles in states and the federal jurisdiction. Within each of these jurisdictions, certain mechanisms exist for categorizing particular juveniles as adults so that they may be legally processed by the adult counterpart to juvenile justice, the criminal justice system. During the 1990s, a number of state legislatures enacted procedures to make it easier to transfer jurisdiction to the adult system (Snyder and Sickmund, 2006). These changes signaled a shift in the perception of youth, who were now being viewed as adults and subject to the same processes and most of the same sanctions.

Who Are Juvenile Offenders?

Juvenile Offenders Defined

Juvenile offenders are classified and defined according to several different criteria. According to the 1899 Illinois Act that created juvenile courts, the jurisdiction of such courts would extend to all juveniles under the age of 16 who were found in violation of any state or local law or ordinance (Ferzan, 2008). About one-fifth of all states place the upper age limit for juveniles at either 15 or 16 years. In most other states, the upper age limit for juveniles is under 18 years; an exception is Wyoming, where the upper age limit is 19 years. Ordinarily, the jurisdiction of juvenile courts includes all juveniles between the ages of 7 and 18. Federal law defines juveniles as any persons who have not attained their 18th birthday (18 U.S.C., Sec. 5031, 2009).

The Age Jurisdiction of Juvenile Courts

The age jurisdiction of juvenile courts is determined through established legislative definitions among the states. The federal government has no juvenile court. Although upper and lower age limits are prescribed, these age requirements are not uniform among jurisdictions. Common law has been applied in many jurisdictions where the minimum age of accountability for juveniles is seven years. Youth under the age of seven are presumed to be incapable of formulating criminal intent and are thus not responsible under the law. While this presumption may be refuted, the issue is rarely raised. Thus, if a six-year-old child kills someone, deliberately or accidentally, he or she likely will be treated rather than punished. In some states, no lower age limits exist to restrict juvenile court jurisdiction. Table 1.1 shows the upper age limits for most U.S. jurisdictions.

Table 1.1 Age at Which Criminal Courts Gain Jurisdiction over Youthful Offenders, 2008

| Age (years) | States |

| 16 | New York and North Carolina |

| 17 | Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Missouri, South Carolina, Wisconsin, and Texas |

| 18 | Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Federal Districts |

| 19 | Wyoming |

Source: Jeffrey A. Butts, Howard N. Snyder, Terrence A. Finnegan, Anne L. Aughenbagh, and Rowen S. Poole (1996). Juvenile Court Statistics 1993: Statistics Report. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Updated 2011 by authors.

The states with the lowest maximum age for juvenile court jurisdiction include New York and North Carolina. In these states, the lowest maximum age for juvenile court jurisdiction is 15. The states with the lowest maximum age of 16 for juvenile court jurisdiction are Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas, and Wisconsin (Szymanski, 2007). All other states and the federal government use 18 years as the minimum age for criminal court jurisdiction. Under the JJDPA, juveniles are individuals who have not reached their 18th birthday (18 U.S.C., Sec. 5031, 2009).

Juvenile offenders who are especially young (under age seven in most jurisdictions) are often placed in the care or custody of community agencies, such as departments of human services or social welfare. Instead of punishing children under the age of seven, various kinds of treatment, including psychological counseling, may be required. Some states have further age-accountability provisions. Tennessee, for instance, presumes that juveniles between the ages of 7 and 12 are accountable for their delinquent acts, although this presumption may be overcome by their attorneys through effective oral arguments and clear and convincing evidence.

Some states have no minimum age limit for juveniles. Technically, these states can decide matters involving children of any age. This control can result in the placement of children or infants in foster homes or under the supervision of community service or human welfare agencies. Neglected, unmanageable, abused, or other children in need of supervision are placed in the custody of these various agencies at the discretion of juvenile court judges. Thus, juvenile courts generally have broad discretionary power over most persons under the age of 18. Under certain circumstances that will be discussed in a later chapter, some juveniles, particularly 11- and 12-year-olds, may be treated as adults in order to prosecute them in criminal court for alleged serious crimes.

Parens Patriae

Parens patriae is a concept that originated with the King of England during the 12th century. It literally means “the father of the country.” Applied to juvenile matters, parens patriae means that the king is in charge of, makes decisions about, and has the responsibility for all matters involving juveniles. Within the scope of early English common law, parents had primary responsibility in rearing children. However, as children advanced beyond the age of seven, they acquired some measure of responsibility for their own actions. Accountability to parents was shifted gradually to the state whenever youth seven years of age or older violated the law. In the name of the king, chancellors in various districts adjudicated matters involving juveniles and the offenses they committed. Juveniles had no legal rights or standing in any court; they were the sole responsibility of the king or his agents. Their future depended largely upon chancellor decisions. In effect, children were wards of the court, and the court was vested with the responsibility of safeguarding their welfare (McGhee and Waterhouse, 2007).

Chancery courts of 12th- and 13th-century England (and in later years) performed various tasks, including the management of children and their affairs as well as care for the mentally ill and incompetent. Therefore, an early division of labor was created, involving a three-way relationship among the child, the parent, and the state. The underlying thesis of parens patriae was that the parents were merely the agents of society in the area of childrearing, and that the state had the primary and legitimate interest in the upbringing of children. Thus, parens patriae established a type of fiduciary or trust-like parent–child relationship, with the state able to exercise the right of intervention to limit parental rights (Friday and Ren, 2006).

Since children could become wards of the court and subject to its control, the chancellors were concerned about the future welfare of these children. The welfare interests of chancellors and their actions led to numerous rehabilitative and/or treatment measures, including placement of children in foster homes or assigning them to perform various tasks or work for local merchants (Rockhill, Green, and Furrer, 2007). Parents had minimal influence on these child placement decisions.

In the context of parens patriae, it is easy to trace this early philosophy of child management and its influence on subsequent events in the United States, such as the child savers movement, houses of refuge, and reform schools. These latter developments were both private and public attempts to rescue children from their environments and meet some or all of their needs through various forms of institutionalization.

Modern Interpretations of Parens Patriae

Parens patriae continues in all juvenile court jurisdictions in the United States. The persistence of this doctrine is evidenced by the wide range of dispositional options available to juvenile court judges and others involved with the early stages of offender processing in the juvenile justice system. Typically, these dispositional options are either nominal or conditional, meaning that the confinement of any juvenile for most offenses is regarded as a last resort. Nominal or conditional options involve various sanctions (e.g., verbal warnings or reprimands, diversion, probation, making financial restitution to victims, performance of community service, participation in individual or group therapy, or involvement in educational programs), and they are intended to reflect the rehabilitative ideal that has been a major philosophical underpinning of parens patriae.

The Get-Tough Movement

The treatment or rehabilitative orientation reflected by parens patriae, however, is somewhat in conflict with the themes of accountability and due process. Contemporary juvenile court jurisprudence stresses individual accountability for one’s actions. The get-tough movement emphasizes swifter, harsher, and more certain justice and punishment than the previously dominant, rehabilitative philosophy of American courts (Mears et al., 2007). Overall, youth are viewed as “mini-adults” who make rational choices that include the deliberate decision to engage in crime (Merlo and Benekos, 2000). In the last 20 years, states have modified their statutes to allow release of the names of juveniles to the media, to allow prosecutors to decide which youth should be transferred to adult court, and to open juvenile court proceedings to the public. These actions are consistent with a more punitive attitude toward youth (Merlo, 2000).

For juveniles, this includes the use of nonsecure and secure custody and sanctions that involve placement in group homes or juvenile facilities. For juveniles charged with violent offenses, this means transfer to the criminal courts, where more severe punishments, such as long prison sentences or even life imprisonment, can be imposed. Although legislatures have enacted laws making it possible to transfer youth to adult court, it is not clear that these policies reflect the public’s opinion regarding how best to address juvenile offending (Applegate, Davis, and Cullen, 2009). The public may favor a juvenile justice system separate from the adult criminal justice system, and evidence suggests a strong preference for a system that disposes most juveniles to treatment or counseling programs in lieu of incarceration, even for repeat offenders (Applegate, Davis, and Cullen, 2009; Piquero et al., 2010).

Parens patriae has been subject to the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of the constitutional rights of juveniles. Since the mid-1960s, the Supreme Court has afforded youth constitutional rights, and some of these are commensurate with the rights enjoyed by adults in criminal courts. The Court’s decisions to apply constitutional rights to juvenile delinquency proceedings have resulted in a gradual transformation of the juvenile court toward greater criminalization. As juvenile cases become more like adult cases, they may be less susceptible to the influence of parens patriae.

Another factor is the gradual transformation of the role of prosecutors in juvenile courts. As more prosecutors actively pursue cases against juvenile defendants, the entire juvenile justice process may weaken the delinquency prevention role of juvenile courts (Sungi, 2008). Thus, more aggressive prosecution of juvenile cases is perceived as moving away from delinquency prevention for the purpose of deterring youth from future adult criminality. Fifteen states, according to Snyder and Sickmund (2006), now authorize prosecutors to decide whether to try a case in adult criminal court or juvenile court. The intentions of prosecutors are to ensure that youth are entitled to due process, but the social costs may be to label these youth in ways that will propel them toward, rather than away from, adult criminality (Mears et al., 2007).

Juvenile Delinquents and Delinquency

Juvenile Delinquents

Legally, a juvenile delinquent is any youth under a specified age who has violated a criminal law or engages in disobedient, indecent, or immoral conduct and is in need of treatment, rehabilitation, or supervision. A juvenile delinquent is a delinquent child (Champion, 2009). These definitions can be ambiguous. What is “indecent” or “immoral conduct?” Who needs treatment, rehabilitation, or supervision? And what sort of treatment, rehabilitation, or supervision is needed?

Juvenile Delinquency

Federal law says that juvenile delinquency is the violation of any law of the United States by a person before his or her 18th birthday that would be a crime if committed by an adult (18 U.S.C., Sec. 5031, 2009). A broader, legally applicable definition of juvenile delinquency is a violation of any state or local law or ordinance by anyone who has not yet achieved the age of majority. These definitions are qualitatively more precise than the previously cited ones.

Definitions of Delinquents and Delinquency

Juvenile courts often define juveniles and juvenile delinquency according to their own standards. In some jurisdictions, a delinquent act can be defined in various ways. To illustrate the implications of such a definition for any juvenile, consider the following scenarios:

Scenario 1 It is 10:15 P.M. on a Thursday night in Detroit. A curfew is in effect for youth under age 18 prohibiting them from being on city streets after 10:00 P.M. A police officer in a cruiser notices four juveniles standing at a street corner, holding gym bags, and conversing. One youth walks toward a nearby jewelry store, looks in the window, and returns to the group. Shortly thereafter, another boy walks up to the same jewelry store window and looks in it. The officer pulls up beside the boys, exits the vehicle, and asks them for IDs. Each of the boys has a high school identity card. The boys are 16 and 17 years of age. When asked about their interest in the jewelry store, one boy says that he plans to get his girlfriend a necklace like one in the store window, and he wanted his friends to see it. The boys then explain that they are waiting for a ride, because they are members of a team and have just finished a basketball game at a local gymnasium. One boy says, “I don’t see why you’re hassling us. We’re not doing anything wrong.” “You just did,” says the officer. He makes a call on his radio for assistance from other officers and makes all the boys sit on the curb with their hands behind their heads. Two other cruisers arrive shortly, and the boys are transported to the police station, where they are searched. The search turns up two small pocket knives and a bottle opener. The four boys are charged with “carrying concealed weapons” and “conspiracy to commit burglary.” Juvenile authorities are notified.

Career Snapshot

(Courtesy of Peter J. Benekos)

Name: Caitlin Ross

Position: Law Student

School attending: University of Maine School of Law

Background

As an undergraduate at Mercyhurst College, I was a double major in Criminal Justice and Marriage and Family Studies. I graduated with a B.A. in each field. I worked hard in classes and maintained a high GPA, which was very important when it came time to apply to law schools. In my first two years at college, I took very broad classes so that I could explore many career options; and in my final two years, I began choosing classes that were tailored to my interests and the career path I wanted to pursue. I was able to take many prelaw and juvenile justice courses, which have greatly benefited me already. Through a constitutional law course, I was able to participate in a mock trial. I took on the role of the defense attorney, and it was an incredibly rewarding experience.

In a class of my sophomore year, I was asked to create a program that served people in some way. After doing extensive research and discovering how ineffective juvenile defense is in many areas of our country, I created a program meant to aid public defenders in educating their juvenile clients about the system and their rights. That spring, I applied for a summer internship at Pine Tree Legal Assistance in Maine, and I was offered the position because of the work I had done on my program. At Pine Tree, I obtained some experience in the legal field by handling a number of public interest cases. My summer at Pine Tree proved to me that my interest in the law was not fleeting. In the spring of my junior year, I began interning in the Juvenile Division of the Erie County Public Defender’s Office. I showed one of the defense attorneys the program I had created, and she was excited to adapt and use it because she wanted to improve her client outreach. Every Friday, we went to the local detention centers and met with her clients to discuss their cases and their due process rights. Her relationship with her clients improved quickly and significantly, and I left the internship confident that I wanted to be a juvenile defense attorney.

I also worked for a professor on campus as a research assistant. For two years, I assisted him with a research project tracking juvenile offenders processed in the adult system. In addition to this work, I wrote papers on juvenile defense and potential policy changes, and I presented them at three conferences over two years. These experiences allowed me to gain some expertise in juvenile defense as well as make connections with professors and criminal justice professionals around the country.

I took the LSAT the summer before my senior year, and in the fall, I applied to a number of law schools. I chose Maine Law for a number of reasons, including their juvenile defender’s clinic, their location, and their scholarship offer. I graduated feeling I had spent my time as an undergraduate well and was ready to take on the challenges of law school.

Advice to Students

My advice to undergraduate students is to make the most of the resources your school and community have to offer. Academic success is important, but it is not the only piece of the undergraduate experience that matters. There are many ways to explore careers and determine your strengths, such as through volunteer programs, school clubs, research opportunities with professors, and internships. Pick internships and activities related to the field in which you see yourself working: Not only will these activities “pad” your resume, they will also help you explore your interests. If you are interested in a particular office that does not do internships, ask if there is anything you can do to get involved with their work—my internship position at the public defender’s office was created for me because I asked. Create opportunities for yourself, and make the most of your college experience: Not only will you get what you want, you will also show future employers and graduate schools that you are driven and resourceful.

Scenario 2 A highway patrol officer spots two young girls with backpacks attempting to hitch a ride on a major highway in Florida. He stops his vehicle and asks the girls for IDs. They do not have any but claim they are over 18 and are trying to get to Georgia to visit some friends. The officer takes both girls into custody and to a local jail, where a subsequent identification discloses that they are, respectively, 13- and 14-year-old runaways from a Miami suburb. Their parents are looking for them. The girls are detained at the jail until their parents can retrieve them. In the meantime, a nearby convenience store reports that two young girls from off the street came in an hour earlier and shoplifted several items. Jail deputies search the backpacks of the girls and find the shoplifted items. They are charged with “theft.” Juvenile authorities are notified.

Are these scenarios the same? No. Can each of these scenarios result in a finding of delinquency by a juvenile court judge? Yes. Whether youth are “hanging out” on a street corner late at night or have shoplifted, it is possible in a juvenile court in the United States that they could be defined collectively as delinquents or delinquency cases.

Of course, some juvenile offending is more serious than other types. Breaking windows or violating curfew would certainly be less serious than armed robbery, rape, or murder. Many jurisdictions divert less serious cases away from juvenile courts and toward various community agencies, where the juveniles involved can receive assistance rather than the formal sanctions of the court.

Should one’s age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity or race, attitude, and other situational circumstances influence the police response? The reality is that juveniles experience subjective appraisals and judgments from the police, prosecutors, and juvenile court judges on the basis of both legal and extralegal factors. Because of their status as juveniles, youth may also be charged with various noncriminal acts. Such acts are broadly categorized as status offenses.

Status Offenders

Status offenders are of interest to both the juvenile justice system and the criminal justice system. Status offenses are acts committed by juveniles that would bring the juveniles to the attention of juvenile courts but would not be crimes if committed by adults. Typical status offenses include running away from home, truancy, and curfew violations. Adults would not be arrested for running away from home, truancy, or walking the streets after some established curfew for juveniles. However, juveniles who engage in these behaviors in particular cities may be grouped together with more serious juvenile offenders who are charged with armed robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, auto theft, or illicit drug sales. Overall, there has been an increase in the number of youth being processed for status offenses. From 1985 to 2004, the number of status offense cases that were petitioned to the court doubled (ACT 4 Juvenile Justice, n.d.).

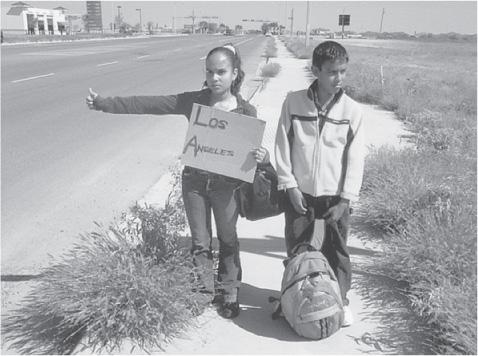

Runaways

It is difficult to determine exactly how many youth are runaways in the United States. Some youth actually do run away from their parents or caretakers, while others are “thrown out.” It was estimated that in 1999, more than 1.6 million youth were either runaway or thrownaway (Snyder and Sickmund, 2006). In terms of arrests for runaways, it was estimated that in 2008, there were over 100,000 arrests of runaways in the United States (Puzzanchera, 2009).

One type of status offense is underage drinking.

(Courtesy of Dean John Champion)

Runaways are those youth who leave their homes, without permission or their parents’ knowledge, and who remain away from home for periods ranging from a couple of days to several years. Many runaways are apprehended eventually by police in different jurisdictions and returned to their homes. Others return because they choose to go back. Some runaways remain permanently missing, although they likely are part of a growing number of homeless youth who roam city streets throughout the United States (Slesnick et al., 2007). Information about runaways and other types of status offenders is compiled annually through various statewide clearinghouses and the federally funded National Incidence Studies of Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Throwaway Children (NISMART) (Sedlak, Finkelhor, and Hammer, 2005).

Runaway behavior is complex. Some research suggests that runaways can have serious mental health needs (Chen, Thrane, and Whitbeck, 2007). In addition, these youth may seek others like themselves for companionship and emotional support (Kempf-Leonard and Johansson, 2007). Runaways view similarly situated youth as role models and peers, and they may engage in delinquency with other youth. Studies of runaways indicate that boys and girls often have familial problems (e.g., neglect and parental drug use) and have been physically and sexually abused by their parents or caregivers (McNamara, 2008b). Evidence suggests that youth who run away may engage in theft or prostitution to finance their independence away from home. In addition, these youth may be exploited by peers or adults who befriend them (Armour and Haynie, 2007).

Some research confirms that runaways tend to have low self-esteem as well as an increased risk of being victimized on the streets (McNamara, 2008b). Although all runaways are not alike, there have been attempts to profile them. Depending upon how authorities and parents react to children who have been apprehended after running away, there may be either positive or negative consequences.

Youth who run away may hitchhike.

(Courtesy of Dean John Champion)

Various strategies have been used to address runaway youth. Congress first enacted the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act in 1974 (Runaway and Homeless Youth Act, 1974). In 2008, the 110th Congress amended the Act and continued to authorize funding for outreach programs, shelters, and transitional living (Reconnecting Homeless Youth Act, 2008). These services are available in many cities. On the streets, outreach workers share information about and make referrals for counseling services, medical care and treatment, and other kinds of community assistance programs. Runaway shelters have been established to offer runaways a nonthreatening residence and social support system in various jurisdictions. These shelters locate services that will help meet the runaways’ needs. Shelters are a short-term option designed to stabilize youth and, if possible, reunite them with family. Finally, services are also available for older youth who cannot return home and require assistance in moving into independent living quarters (McNamara, 2008b).

Truants and Curfew Violators

Truants

Status offenders also include truants as well as curfew and liquor law violators. Truants are those who absent themselves from school without school or parental permission. The national data on truancy rates are problematic for several reasons: One school district can define truancy differently than another district; sociodemographic characteristics of truants are not normally maintained, even by individual schools; and no consistent, central reporting mechanisms exist for data compilations about truants. For instance, one state may define a truant as a youth who absents himself or herself from school without excuse for five or more consecutive school days. In another state, a truant may be defined as someone who misses one day of school without a valid excuse.

Truancy is more likely to occur in urban schools than in suburban schools. Research suggests that truancy is a “gateway activity” (McNamara, 2008b, p. 47) for further problem behaviors ranging from gang behavior to substance abuse. For example, Chiang et al. (2007) found that about two-thirds of all male youth arrested while truant tested positive for drug use.

Truancy is not a crime. It is a status offense. Youth can be charged with truancy and brought into juvenile court for status offense adjudication. Truancy is taken quite seriously in many jurisdictions.

Several states have developed formal mechanisms to deal with the problem of truancy. The Family Court system of Rhode Island has established truancy courts to increase status offender accountability relating to truancy issues. Chronic truants are referred to the Truancy Court, where their cases are handled. The process involves the truant youth, the parents/guardians, a truant officer, and a Truancy Court magistrate. The purpose of the Truancy Court is to avoid formal juvenile court action. Youth can do this by obeying the behavioral requirements outlined, which include (1) attending school every day, (2) arriving to school on time, (3) behaving in school, and (4) completing classroom work and homework. Failure to comply with one or more of these requirements may result in a referral to Family Court or placement in a program administered by the Department of Children, Youth, and Families. The youth might be subject to increasingly punitive sanctions if the truancy persists following the Truancy Court hearing.

The Truancy Court also requires parents to sign a form that permits the release of confidential information about the truant. This information is necessary to devise a treatment program and provide any counseling or services the truant may require. Thus, the Family Court is vested with the power to evaluate, assess, and plan activities designed to prevent further truancy, and various interventions are initiated to enhance the youth’s awareness of the seriousness of truancy and the importance of staying in school.

Delaware has a truancy prevention program that is available throughout the state. Five judges deal with truant youth and their families, and they utilize an approach similar to the drug court model. The same judge works with the youth and the family throughout the process. Parents are encouraged to be responsible for their children, and the court collaborates with a number of social service agencies to work with the family and offer services to family members. Research suggests that this approach has been effective in reducing truancy in the state, and in helping youth stay in school (McNamara, 2008b).

Curfew Violators

Curfew violators are those youth who remain on city streets after specified evening hours when they are prohibited from loitering or are not in the company of a parent or guardian. In 2010, more than 73,000 youth were arrested for violating curfew and loitering laws in the United States (U.S. Department of Justice, 2011).

Shoplifting is a common delinquent offense.

(Courtesy of Dean John Champion)

In an effort to decrease the incidence of juvenile crime during the mid-1990s, many cities throughout the United States enacted curfew laws specifically applicable to youth. The theory is that if juveniles are obliged to observe curfews in their communities, they will have fewer opportunities to commit delinquent acts or status offenses (Urban, 2005). For example, in New Orleans, Louisiana, in June 1994, the most restrictive curfew law went into effect. Under this law, juveniles under age 17 were prohibited from being in public places, including the premises of business establishments, unless accompanied by a legal guardian or authorized adults. The curfew began at 8:00 P.M. on weeknights and 11:00 P.M. on weekends. Exceptions were made for youth who might be traveling to and from work or were attending school, religious, or civil events. A study on the impact of this strict curfew law, however, revealed that juvenile offending shifted to noncurfew hours (Urban, 2005). Furthermore, the enforcement of this curfew law by New Orleans police was difficult, because curfew violations often occurred outside of a police presence. If anything, the curfew law tended to induce rebelliousness among those youth affected by the law. The research indicates that curfew laws have not been an especially effective deterrent to status offending or delinquency generally (Adams, 2003; Urban, 2005). Nonetheless, in the summer of 2011, the Mayor of Philadelphia imposed a temporary 9:00 P.M. curfew on Friday and Saturday nights in specific geographical areas to prevent flash mobs, who had attacked some residents, from congregating in the city (CNN Wire Staff, 2011).

Juvenile and Criminal Court Interest in Status Offenders

Among status offenders, juvenile courts are most interested in chronic or persistent offenders, such as those who habitually appear before juvenile court judges (Hill et al., 2007). Some research suggests that greater contact with juvenile courts can result in youth acquiring labels or stigmas as either delinquents or deviants (Feiring, Miller-Johnson, and Cleland, 2007). Therefore, diversion of juvenile offenders from the juvenile justice system has been advocated and recommended to minimize stigmatization.

One increasingly popular strategy is to remove certain types of offenses from the jurisdiction of juvenile court judges (Trulson, Marquart, and Mullings, 2005). Because status offenses are less serious than juvenile delinquency cases, many state legislatures have pushed for the removal of status offenses from juvenile court jurisdiction. The removal of status offenders from the discretionary power of juvenile courts is, in part, an initiative based on the deinstitutionalization of status offenders (DSO).

The Deinstitutionalization of Status Offenses (DSO)

The JJPDA of 1974

Congress enacted the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) of 1974 in response to a national concern about growing juvenile delinquency and youth crime (Bjerk, 2007). This Act authorized establishment of the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), which is extremely helpful and influential in funding research and disseminating data and information about juvenile offending and prevention. The Act had two main provisions: (1) to remove juveniles who were involved in status offenses from secure detention or juvenile correctional facilities within two years of the legislation and (2) to make certain that youth were not held in facilities where they would have contact with adults convicted of a crime (OJJDP, n.d.). This mandate became known as the deinstitutionalization of status offenders (DSO). Although state participation was voluntary, funding for state initiatives was tied to state compliance with the legislation (Schwartz, 1989).

Changes and Modifications in the JJDPA

Throughout its history, the JJDPA has been reviewed and amended by Congress. In 1977, Congress increased and expanded its earlier initiatives in the deinstitutionalization of status offenders and its restrictions on sight and sound separation for juvenile offenders in adult institutions (OJJDP, n.d.). In 1980, Congress recommended that states refrain from detaining juveniles in jails or adult lockups. These requirements were enhanced in the 1984 amendments to the legislation.

In 1988, Congress also directed that states examine their secure confinement policies relating to minority juveniles and determine reasons—and justification—for the disproportionately high rate of minority confinement. The disproportionate minority confinement (DMC) requirement prompted states to investigate why minority youth were incarcerated at a higher rate and to develop strategies to address the imbalance. When Congress reauthorized the legislation in 1992, there was a focus on girls in the system, and states were required to examine existing programs for girls and make certain that the programs were specific to their needs. States also were to ascertain that each youth was treated equally (Chesney-Lind and Irwin, 2006).

The 2002 revisions to the Act expanded DMC to include all parts of the juvenile justice process. Today, DMC refers to disproportionate minority contact (Snyder and Sickmund, 2006). Subsequent amendments and authorizations of the JJDPA have occurred since it was enacted, and Congress is currently considering the proposed reauthorization of the legislation.

For approximately 20 years, Congress has directed that any participating state would have up to 25 percent of its formula grant money withheld to the extent that the state was not in compliance with each of the JJDPA mandates. Thus, state compliance with the provisions of the JJDPA was encouraged by providing grants-in-aid to jurisdictions wanting to improve their juvenile justice systems and facilities. Overall, states have endeavored to comply with the JJDPA mandate throughout their juvenile justice systems, and the Act has served as a significant catalyst for reform initiatives.

DSO Defined

The best definition of DSO is the removal of status offenders from juvenile secure institutions. Deinstitutionalization of youth from training schools, reform schools, and other secure juvenile facilities was first stipulated by Congress.

Deinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalization refers to the removal of status offenders from secure juvenile institutions, such as state industrial or training schools. Before the JJDPA of 1974, states incarcerated both status and delinquent offenders together in reform schools or industrial schools (Champion, 2008a). Should truants, curfew violators, runaways, and difficult-to-control children be placed in secure facilities together with adjudicated juvenile burglars, thieves, robbers, arsonists, and other violent and property felony offenders? Clearly, substantial differences exist between status offenders and delinquent offenders.

Congress determined that requiring status offenders to live and interact with delinquents in secure confinement, especially for prolonged periods of time, is detrimental to status offenders and inconsistent with the mission of the juvenile court. The exposure of status offenders to the criminogenic influence of, and close association with, serious delinquents adversely affects the social and psychological well-being of status offenders. The damage to a status offender’s self-concept and self-esteem, coupled with the further immersion into the system, was perceived as problematic (Champion, 2008a).

Subsequently, states have implemented deinstitutionalization policies for status offenders. To expedite the removal of status offenders from secure juvenile facilities, the federal government made available substantial sums of money for establishing alternative social services. Overwhelmingly, states have complied with the regulations and successfully accessed the federal money allocated.

Under certain conditions, however, states may incarcerate status offenders who are under some form of probationary supervision. For instance, a Texas juvenile, E.D., was on probation for a status offense (In re E.D., 2004). During the term of E.D.’s probation, she violated one or more of the conditions of probation. The juvenile court elected to confine E.D. to an institution for a period of time as a sanction for the probation violation. E.D. appealed, contending that as a status offender, she should not be placed in a secure facility. The Court of Appeals in Texas disagreed and held that the juvenile court judge had broad discretionary powers to determine E.D.’s disposition, even including placement in a secure facility. The appellate court noted that secure placement of a status offender is warranted whenever the juvenile probation department has (1) reviewed the behavior of the youth and the circumstances under which the juvenile was brought before the court, (2) determined the reasons for the behavior that caused the youth to be brought before the court, and (3) determined that all dispositions, including treatment, other than placement in a secure detention facility or secure correctional facility have been exhausted or are clearly inappropriate.

The juvenile court judge set forth an order that (1) it is in the child’s best interests to be placed outside of her home, (2) reasonable efforts were made to prevent or eliminate the need for the child’s removal from her home, and (3) the child, in her home, could not be provided the quality of care and support that she needs to meet the conditions of probation. There was no suggestion in the record that the judge failed to comply with these three major requirements. Thus, this ruling suggests that despite the deinstitutionalization initiative, status offenders may be incarcerated if they violate court orders while on probation.

Diverting Dependent and Neglected Children to Social Services

A different application of DSO deals with dependent and neglected children. While the juvenile court continues to exercise jurisdiction over dependent and neglected youth, programs have been established to receive referrals of these children directly from law enforcement officers, schools, parents, or even the youth. These diversion programs provide crisis intervention services for youth, and their aim is to eventually return juveniles to their homes. However, more serious offenders may need services provided by shelter homes, group homes, or even foster homes (Sullivan, Veysey, et al., 2007). Collaborative community programs have been established to address this need.

Potential Outcomes of DSO

There are three potential outcomes of the DSO:

The number of status offenders in secure confinement, especially in local facilities, may be reduced. Greater numbers of jurisdictions are adopting deinstitutionalization policies, so the actual number of institutionalized status offenders should decrease.

Net-widening, or bringing youth into the juvenile justice system who would not have been involved in the system previously, may swell. Some state jurisdictions may have increased the number of status offenders in the juvenile justice system following DSO. Previously, status offenders in those states would have been handled informally. When specific community programs were established for status offenders, however, the net widened, and youthful offenders were eligible to be placed in programs that offered specialized social services. The result is that more youth can come into contact with the system.

Relabeling, or defining youth as delinquent or emotionally disturbed who in the past would have been defined and processed as status offenders, may occur in certain jurisdictions following DSO. For instance, police officers in some jurisdictions might label juvenile curfew violators or loiterers as larceny or burglary suspects and detain these youth. In brief, by attaching a new or different label to the behavior, youth can be brought into the juvenile justice system.

Based upon the last 38 years, DSO has clearly become not just widespread but also the prevailing juvenile justice policy. The DSO requirements stipulated that agencies and organizations contemplate new and innovative strategies to cope with youth with diverse needs, which has resulted in various programs to better serve status offenders. Greater cooperation and collaboration among the public, youth services, and community-based treatment programs facilitate developing the best program policies and practices. The implementation of DSO has helped foster these initiatives.

Some Important Distinctions between Juvenile and Criminal Courts

Some of the major differences between juvenile and criminal courts are indicated below. These general principles reflect most jurisdictions in the United States.

Juvenile courts are civil proceedings designed for juveniles, whereas criminal courts are proceedings designed to try adults charged with crimes. In criminal courts, adults are the focus of criminal court actions, although some juveniles may be tried as adults in these same courts. The civil–criminal distinction is important, because an adjudication of a juvenile court case does not result in a criminal record for the juvenile offender. In criminal courts, either a judge or a jury finds a defendant guilty or not guilty. In the case of guilty verdicts, offenders are convicted and acquire criminal records. These convictions follow offenders for the rest of their lives. However, when juveniles are found to be involved in delinquent behavior by juvenile courts, states can authorize procedures to seal or expunge juvenile court adjudications once the youth reaches adulthood or the age of majority.

Juvenile proceedings are more informal, and criminal proceedings are more formal. Attempts are made in many juvenile courts to avoid the prescribed aspects that characterize criminal proceedings. Juvenile court judges frequently address juveniles directly and casually, and proceedings are sometimes conducted in the judge’s chambers rather than a courtroom. Despite attempts by juvenile courts to minimize formal proceedings, juvenile court procedures in recent years have become increasingly formalized. At least in some jurisdictions, it may even be difficult to distinguish criminal courts from juvenile courts in terms of their formality.

In 30 states (including the District of Columbia), juveniles are not entitled to a trial by jury; in 10 states, juveniles have a constitutional right to a jury trial; and in 11 states, youth can be granted a jury trial under specific circumstances (Szymanksi, 2002). In all criminal proceedings, defendants are entitled to a trial by jury if the crime or crimes they are accused of committing carry a possibility of incarceration for more than six months. Judicial approval is required to hold a jury trial for juveniles in some jurisdictions. This is one more manifestation of the legacy of the parens patriae doctrine in contemporary juvenile courts. Eleven states have legislatively mandated jury trials for juveniles in juvenile courts if they are charged with certain types of offenses, are above a specified age, may be sentenced to an adult facility, and request a jury trial (Szymanksi, 2002, p.1).

Juvenile court and criminal court are adversarial proceedings. Juveniles may or may not wish to retain or be represented by counsel (In re Gault, 1967). In a juvenile court case, prosecutors allege various infractions or law violations by the juveniles, and these charges can then be refuted by juveniles or their counsel. If juveniles are represented by counsel, defense attorneys are permitted to offer a defense to the allegations. Criminal courts are obligated to provide counsel for anyone charged with a crime if the defendant cannot afford to retain his or her own counsel and could be sentenced to a term of incarceration (Argersinger v. Hamlin, 1972). Every state has provisions for providing defense attorneys to indigent juveniles who are to be adjudicated in juvenile court. However, a recent review of state procedures suggests that not all youth receive the assistance of effective counsel (Ross, 2011).

Criminal courts are courts of record, whereas transcripts of juvenile proceedings are made only if the state law authorizes them. Court reporters record all testimony presented in most criminal courts. State criminal trial courts are courts of record, where either a tape-recorded transcript of the proceedings is maintained or a written record is kept. Thus, if trial court verdicts are appealed by the prosecution or defense, transcripts of these proceedings can be presented by either side as evidence of errors committed by the judge or other violations of due process rights. Juvenile courts, however, are not courts of record. Therefore, in any given juvenile proceeding, whether a juvenile court judge will ask for a court reporter to transcribe the adjudicatory proceedings depends on the specific jurisdiction. One factor that inhibits juvenile courts from being courts of record is the expense of hiring court reporters for this work. Furthermore, the U.S. Supreme Court has declared that juvenile courts are not obligated to be courts of record (In re Gault, 1967). Nonetheless, in some jurisdictions, juvenile court judges may have access to a court reporter to transcribe or record all court matters.

The standard of proof used for determining one’s guilt in criminal proceedings is beyond a reasonable doubt. The less rigorous civil standard of preponderance of the evidence is used in some juvenile court cases. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that if any juvenile is in jeopardy of losing his or her liberty as the result of a delinquency adjudication by a juvenile court judge, then the evidentiary standard must be the criminal court standard of beyond a reasonable doubt (In re Winship, 1970). The Court’s decision dealt with youth who could be incarcerated for any period of time, whether for one day, one month, one year, or longer. Thus, juveniles in juvenile court who confront the possible punishment of confinement in a juvenile facility are entitled to the evidentiary standard of beyond a reasonable doubt in determining their involvement in the act. Juvenile court judges apply this standard when adjudicating a juvenile’s case and the loss of liberty is a possibility.

The range of penalties juvenile court judges may impose is limited, whereas in most criminal courts, the range of penalties may include life-without-parole sentences or even the death penalty. The jurisdiction of juvenile court judges also typically ends when the juvenile reaches adulthood. Some exceptions are that juvenile courts may retain jurisdiction over mentally ill youthful offenders indefinitely after they reach adulthood. In California, for instance, the Department of the Youth Authority supervises youthful offenders ranging in age from 11 to 25.

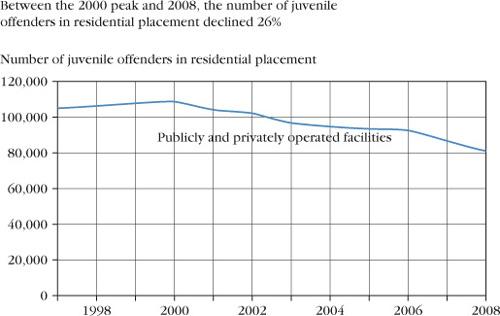

The purpose of this comparison is to illustrate that criminal court actions are more serious and have harsher long-term consequences for offenders compared with juvenile court proceedings. Juvenile courts continue to be guided by a strong rehabilitative orientation in most jurisdictions, where the most frequently used sanction is probation. In 2007, probation was used in approximately 56 percent of the cases in which a juvenile was adjudicated delinquent (Livsey, 2010, p. 1). Criminal courts also use probation as a sanction in about 60 percent of all criminal cases, and in 2009, about 4.2 million adult offenders were on probation (Glaze, 2010). Although juvenile courts may be utilizing more punitive sanctions, many youth continue to receive treatment-oriented punishments rather than incarceration in secure juvenile facilities. Secure confinement is viewed by most juvenile court judges as a last resort, and this disposition is reserved for only the most serious youthful offenders (LaMade, 2008).

An Overview of the Juvenile Justice System

The Ambiguity of Adolescence and Adulthood

Police have broad discretionary powers in their encounters with the public and in dealing with street crime, and police handle a large number of youth informally. However, police arrests and detentions of juveniles in local facilities remain the primary way that a juvenile enters the juvenile justice system.

Some juveniles are clearly children. It is difficult to find youth under 13 who physically appear to be 18 or older. Yet, nearly 10 percent of all juveniles held for brief periods in adult jails each year are 13 or younger (OJJDP, 2007). For juveniles 14 to 17 years of age, visual determination of one’s juvenile or nonjuvenile status is increasingly difficult. This might explain why police officers initially—and mistakenly—may take youthful offenders to jails for identification and questioning.

Other ways that juveniles can enter the juvenile justice system include referrals from or complaints by parents, neighbors, victims, and others (e.g., social work staff or probation officers) unrelated to law enforcement. Dependent or neglected children may be reported to police initially, and in investigating these complaints, police officers may take youth into custody until arrangements for their care can be made. Alternatively, police officers may apprehend youth for alleged crimes.

Being Taken into Custody

Being taken into custody is another term for arrest. Rarely are dependent or neglected youth taken into custody, but police might apprehend a runaway or missing youth and then hold him or her until the parent or guardian is notified (Armour and Haynie, 2007). Youth on the streets after curfew may also be taken into custody by police.

When youth are taken into police custody, it generally means that they are suspected of delinquent behavior. Formal charges may be filed against them once it is established which court has jurisdiction in their cases. Police may determine that the juvenile court has jurisdiction, depending on the age or youthfulness of the offender. Conversely, the prosecutor and/or judge may decide that the criminal court has jurisdiction and the youthful offender should be charged as an adult.

Juveniles in Jails

In 2009, approximately 7,200 juveniles under the age of 18 were being held in jails (Minton, 2010). About 80 percent of these juveniles were being held as adults. This represents roughly one percent of all inmates held in jails for 2009, and it does not reflect the total number of juveniles who are brought to jail annually after they have been arrested by police. Many youth are held for short periods of time (e.g., two or three hours) even though they have not been specifically charged with an offense. Legislators in Illinois have enacted a statute preventing police officers from detaining juveniles in adult jails for more than six hours (Arya, 2011). Such laws reflect the jail removal initiative, in which states are encouraged to avoid holding juveniles in adult jails, even for short periods.

The Illinois policy preventing the police from detaining juveniles in jails except for limited periods is consistent with a major provision of the JJDPA of 1974. Although the JJDPA is not binding on any state, it does advise law enforcement officials to treat juveniles differently from adult offenders if juveniles are taken to jails for brief periods. For instance, the JJDPA recommends that youth be separated in jails by sight and sound from adult offenders. Furthermore, they should be held in nonsecure areas of jails for periods not exceeding six hours and should not be restrained in any way with handcuffs or other devices while detained. Their detention should only be as long as is necessary to identify them and reunite them with their parents, guardians, or a responsible adult from a public youth agency or family services.

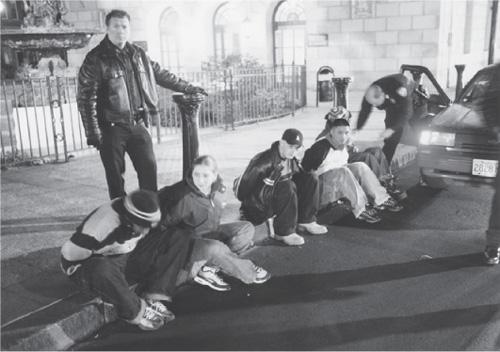

Similar to adults, teens are arrested, handcuffed, and taken into custody.

(Courtesy of Mark C. Ide)

Even more serious delinquent offenders brought to jail to be detained should be processed according to JJDPA recommendations. Sight and sound separation from adult offenders is encouraged, although juveniles alleged to have committed delinquent offenses are subject to more restrictive detention provisions. The general intent of this aspect of the JJDPA is to minimize the adverse effects of labeling and victimization that might occur if juveniles are treated like adult offenders. Another factor is the recognition that most of these offenders’ cases will eventually be handled by the juvenile justice system. Any attributions of criminality arising from how juveniles are treated while they are in adult jails are considered to be incompatible with the rehabilitative ideals of the juvenile justice system and the outcomes or consequences ultimately experienced by most juvenile offenders. Thus, some of the JJDPA goals are to prevent juveniles from being influenced, psychologically or physically, by adults through jail contact, to prevent their victimization, and to insulate them from defining themselves as criminals, which might occur through processing.

Despite new laws designed to minimize or eliminate holding juveniles in adult jails or lockups, even for short periods of time, juveniles continue to be held in jails. Their detention may be related to a number of factors. For example, juveniles can appear to be older to police officers than they really are. They may present false IDs or even no IDs, offer fictitious names when questioned, or refuse to provide police with any information about their true identities. It takes time to determine who the youth are and which responsible adult or guardian should be contacted. Some runaways who police apprehend are from different states, and planning may be required for their parents or guardians to reunite with them. Juveniles can also be aggressive, assaultive, and obviously dangerous. They are sometimes confined or restrained, if only to protect others. Some youth are even suicidal and need temporary protection.

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that preventive detention of juveniles for brief periods can be used without violating their constitutional rights, especially for those offenders who pose a danger to themselves or others (Schall v. Martin, 1984). In that particular case, a juvenile, Gregory Martin, was detained at the police department’s request for serious charges. Gregory refused to give his name or other identification and was perceived to be dangerous, either to himself or to others. His preventive detention was upheld by the Supreme Court as not violating his constitutional right to due process. Before this ruling, however, many states had similar laws that permitted pretrial and preventive detention of both juvenile and adult suspects. Although pretrial detention presupposes a forthcoming trial of those detained and preventive detention does not, both terms are often used interchangeably—or even combined, as in the term preventive pretrial detention (Brookbanks, 2002).

Referrals

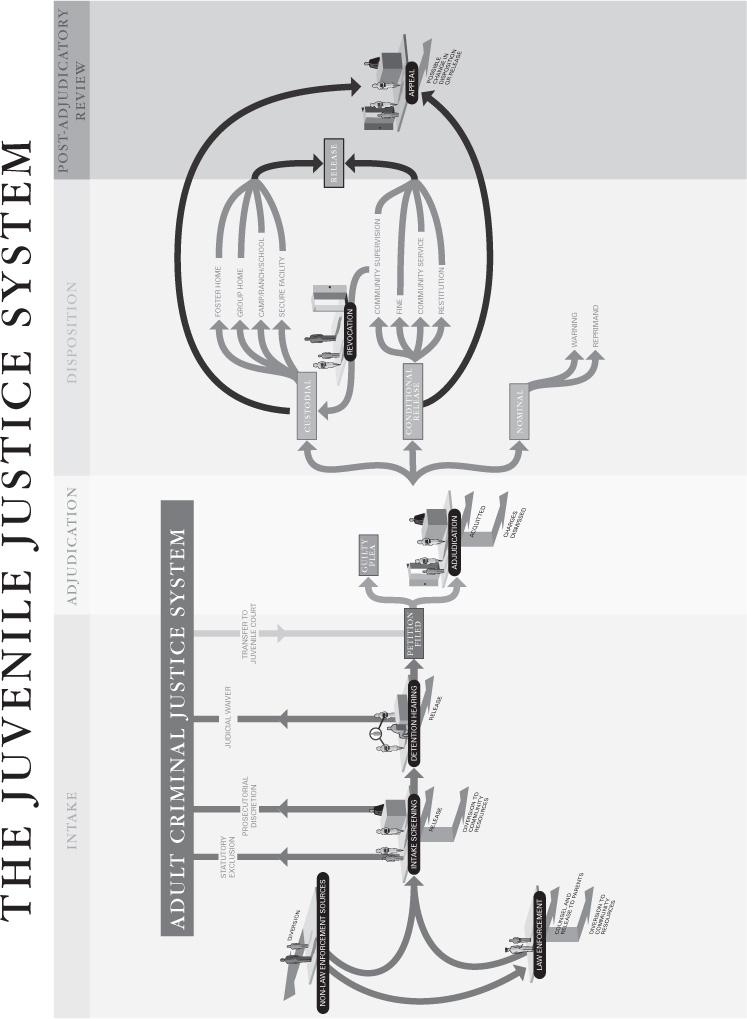

Figure 1.1 is a diagram of the juvenile justice system. Although each jurisdiction in the United States has its own methods for processing juvenile offenders, Figure 1.1 encompasses most of these stages. As shown on this diagram, a majority of juvenile encounters with the juvenile justice system are through referrals from police officers. Referrals are notifications made to juvenile court authorities that a juvenile requires the court’s attention. Referrals can be made by various individuals, including concerned parents, school principals, teachers, neighbors, truant officers, and social service providers. However, most referrals to juvenile courts are made by law enforcement officers. In 2007, police referrals accounted for approximately 83 percent of the delinquency cases, but some variation occurs in offense categories. For example, police referrals occurred in over 93 percent of cases involving drug law violations or property offenses (Puzzanchera, Adams, and Sickmund, 2010, p. 31). Referrals may be made for runaways; truants; curfew violators; unmanageable, unsupervised, or incorrigible children; children with drug or alcohol problems; or any youth suspected of committing a crime (Kuntsche et al., 2007).

Figure 1.1 Diagram of the Juvenile Justice System

Each jurisdiction throughout the United States has its own policies relating to how referrals are handled. In Figure 1.1, following an investigation by a police officer, juveniles are counseled and released to parents; referred to community resources; cited and referred to juvenile intake, followed by a subsequent release to parents; or transported to juvenile detention or shelter care to be held. Each of these actions is the result of police discretion. The discretionary action of police officers who take youth into custody for any reason is governed by what the officers observed. If a youth has been loitering, especially in cities with curfew laws for juveniles, the discretion of police officers might be to counsel the youth and release him or her to the parents without further action. If the youth violated liquor laws or committed some minor infraction, he or she may be cited by police and referred to a juvenile probation officer for further processing. Most youth are returned to the custody of their parents or guardians. However, some youth are apprehended while committing serious crimes. If that occurs, police officers typically transport the youth to a juvenile detention center or shelter to await further action by juvenile justice system personnel.

In New Mexico, for example, whenever a juvenile is referred to the juvenile justice system for any offense, the referral is first screened by the Juvenile Probation/ Parole Office. Juvenile probation/parole officers (JPPOs) are assigned to initially review a police report and file. This function is performed, in part, to determine the accuracy of the report and if the information is correct. If the information is accurate, an intake process will commence, in which the youth undergoes further screening by a JJPO assigned to the case by a supervisor (New Mexico Juvenile Justice Division, 2002).

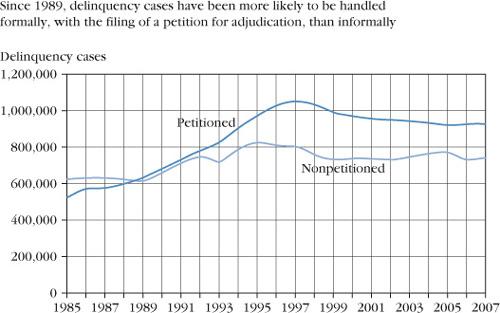

Once a referral has been made to the Juvenile Probation/Parole Office, a decision is made whether to file a petition or to handle the case informally. About 56 percent of all delinquency cases are handled formally (Puzzanchera, Adams, and Sickmund, 2010, p. 37). A petition is an official document filed in juvenile court on the juvenile’s behalf that specifies the reasons for the youth’s court appearance. These documents assert that juveniles fit within the jurisdictional categories of dependent or neglected, status offender, or delinquent, and the reasons for such assertions are usually provided. Filing a petition formally places the juvenile before the juvenile court judge. However, juveniles may come before juvenile court judges in less formal ways. About 44 percent of the cases brought before the juvenile court each year are nonpetitioned cases (Puzzanchera, Adams, and Sickmund, 2010, p. 37).

When individual cases are handled informally, JPPOs in jurisdictions in New Mexico have several options. Whenever youth are determined to require special care, are neglected or dependent, or are otherwise unsupervised by adults or guardians, JPPOs may refer them to a Juvenile Early Intervention Program (JEIP). The JEIP is a highly structured program for at-risk, nonadjudicated youth. Other states have similar programs designed to help youth who might need specific services.

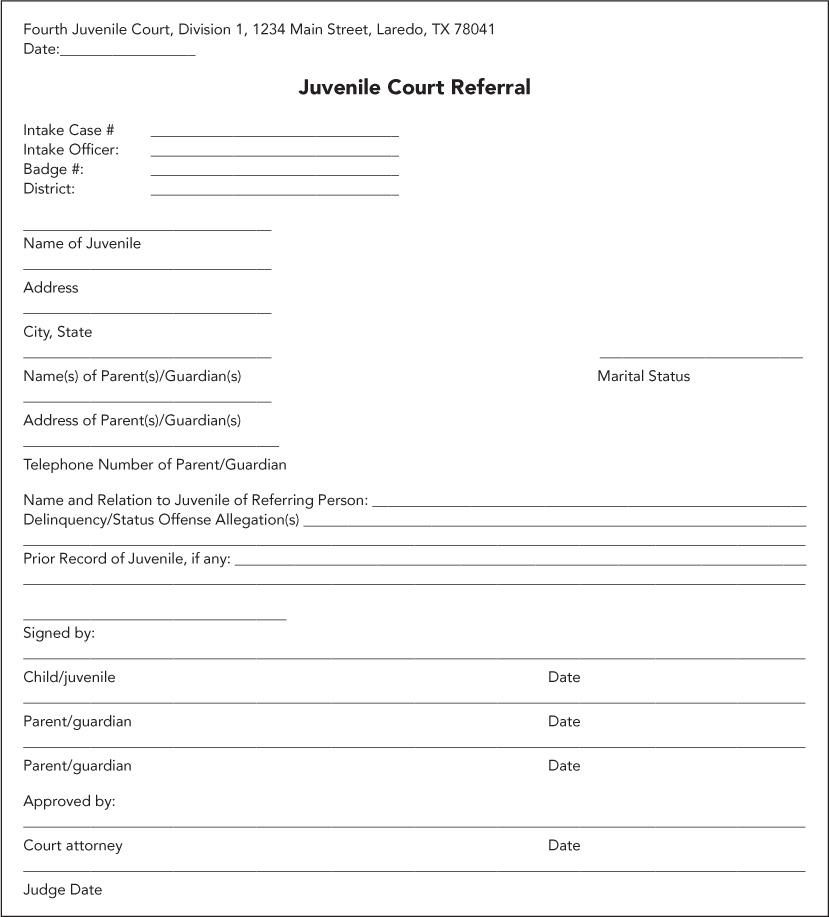

Depending upon the jurisdiction, however, the majority of alleged juvenile delinquents will be advanced further into the juvenile justice system. Some status offenders, especially recidivists, will also progress through the system. Alternatively youth may be held in juvenile detention facilities temporarily to await further action. Other youth may be released to their parent’s custody, but these juveniles may be required to reappear later for further court action. Most of these youth will subsequently be interviewed by an intake officer in a proceeding known as intake. Figure 1.2 shows an example of a juvenile court referral form used by an intake officer.

Figure 1.2 Juvenile Court Referral Form Source: Prepared by authors.

Intake

Intake varies among jurisdictions. Intake is a screening procedure usually conducted by a juvenile probation officer and during which several recommendations can be made. Some jurisdictions conduct intake hearings or intake screenings, where information and explanations are solicited from relevant individuals, such as police, parents, neighbors, or victims. In other jurisdictions, intake proceedings are quite informal, usually consisting of a dialogue between the juvenile and the intake officer. These are important proceedings, regardless of their degree of formality. Intake is a major screening stage in the juvenile justice process, where further action against juveniles may be contemplated or required. Intake officers can hear complaints against juveniles and informally resolve the less serious cases, or they can be juvenile probation officers who perform intake as a special assignment. Also, juvenile probation officers may perform diverse functions, including intake, enforcement of truancy statutes, and juvenile placements (Champion, 2008a).

Intake officers also consider the youth and his or her attitude, demeanor, age, seriousness of offense, and a host of other factors. Has the juvenile had frequent prior contact with the juvenile justice system? If the offenses alleged are serious, what evidence exists against the offender? Should the offender be referred to social service agencies or for psychological counseling, receive vocational counseling and guidance, acquire educational or technical training and skills, be issued a verbal reprimand, be placed on some type of diversionary status, or be returned to parental custody? Interviews with parents are conducted as a part of an intake officer’s information gathering. Although intake is supposed to be an informal proceeding, it is nevertheless an important stage in juvenile processing. The intake officer often acts in an advisory capacity, because he or she is the first juvenile court contact children and their parents will have following an arrest or being taken into custody. The youth and the parents have a right to know the charge(s). It is indicated to the youth and the parents that the intake hearing is a preliminary inquiry and not a fact-finding session to determine one’s guilt, and the intake officer advises the youth that statements made by the child and/or parents may be used in court if such action is warranted.

In most jurisdictions, depending upon the discretion of intake officers, intake results in one of five actions: (1) dismiss the case, with or without a verbal or written reprimand; (2) remand the youth to the custody of the parents; (3) remand the youth to the custody of the parents, but with provisions for or referrals to counseling or special services; (4) place the youth on informal probation or supervision; or (5) refer the youth to the juvenile prosecutor for further action and possible filing of a delinquency petition (Champion and Mays, 1991). In 2007, more than half the cases referred to the juvenile court for delinquency resulted in a formal petition being filed (Knoll and Sickmund, 2010).

Police officers explain drugs, alcohol, and tobacco and their effects to classes of students in schools.

(Anne Vega/Merrill Education)

Theoretically, at least, only the most serious juveniles will be referred to detention to await a subsequent juvenile court appearance. For a youth to be detained while awaiting a juvenile court appearance, a detention hearing must be conducted. Juveniles considered for detention generally are determined to be a danger to the community, are believed likely to be harmed if released, or are perceived as likely to flee the jurisdiction to avoid prosecution in juvenile court. Other youth may be released to the custody of their parents, sometimes with a referral to community service organizations; usually, these community resources are intended to meet the specific needs of particular juvenile offenders. For serious cases, a petition is filed with the juvenile court. The juvenile court prosecutor further screens these petitions and decides which ones merit an appearance before the juvenile court judge. In Alaska, for example, a petition for adjudication of delinquency is used to bring delinquency cases before the juvenile court.

Other petitions may allege status offending, such as truancy, runaway behavior, curfew violation, or violation of drug or liquor laws (McNamara, 2008b). Not all petitions result in formal action by a juvenile court prosecutor. Like prosecutors in criminal courts, juvenile court prosecutors prioritize which cases they will pursue. This case ranking depends upon a number of factors, including the seriousness of the alleged offense, the volume of petitions filed, the time estimated for the juvenile court judge to hear and act on these petitions, and the sufficiency of evidence supporting these petitions (Backstrom and Walker, 2006). As shown in Figure 1.3, however, there has been a more formal response to youthful offending in the last two decades, and more delinquency cases referred to the juvenile court result in a formal petition than those that are handled informally.

Figure 1.3 Number of Delinquency Cases Formally Processed: 1989–2007

Source: Charles Puzzanchera, Benjamin Adams, and Melissa Sickmund (2010). Juvenile Court Statistics 2006–2007. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Alternative Prosecutorial Actions

Cases referred to juvenile prosecutors for further action tend to be more serious. Exceptions might include those youth who are chronic offenders or technical probation violators and nonviolent property offenders (e.g., status offenders, vandalism, petty theft, or public order offenders).

Juvenile court prosecutors have broad discretion. They may cease prosecutions against alleged offenders or reduce the charges in the petition from felonies to misdemeanors or from misdemeanors to status offenses. In some instances, prosecutors may divert some of the more serious juvenile cases for processing by criminal courts. The least serious cases are disposed of informally. Prosecutors either file petitions or act on petitions filed by others, such as intake officers, the police, school officials, or interested family and citizens (LaMade, 2008).

Police encounters with juveniles on city streets sometimes lead to arrests and juvenile processing.

(© A. Ramey / PhotoEdit)

Adjudicatory Proceedings

Jurisdictions vary considerably concerning juvenile court proceedings. In some states, juvenile courts appear to be emulating criminal courts. The physical features of criminal courts are present, including the judge’s bench, tables for the prosecution and defense, and a witness stand. Further, evidence suggests that courts are currently holding juveniles more accountable for their actions (LaMade, 2008).

Besides the more formal atmosphere of juvenile courts, the procedure is becoming increasingly adversarial. The prosecutor represents the state, and the youth is entitled to be represented by defense counsel. However, research shows that only about 50 percent of the juvenile offenders in delinquency proceedings have the assistance of counsel (Bishop, 2010; LaMade, 2008). Typically, juvenile court judges have discretion in determining how court proceedings are conducted. Juvenile defendants alleged to have committed various offenses may or may not be entitled to a jury. In 2007, only 11 states provided jury trials for juveniles in juvenile courts, and these jury trials were restricted to a narrow list of serious offenses.

After hearing the evidence presented by both sides in any juvenile proceeding, the judge decides or adjudicates the matter in an adjudication hearing, sometimes called an adjudicatory hearing. Adjudication is a judgment or action on the petition filed with the court. If the petition alleges that the youth is a delinquent, the judge determines whether this is so. If the petition alleges that the juvenile involved is dependent, neglected, or otherwise in need of care by agencies or others, the judge decides the matter. If the adjudicatory hearing fails to yield facts supporting the petition filed, the case is dismissed, and the youth exits the juvenile justice system. If, however, the adjudicatory hearing supports the allegations in the petition, the judge must dispose of the juvenile’s case according to a range of sanctions (Champion and Mays, 1991).

Juvenile Dispositions

Disposing of a juvenile’s case is the equivalent of sentencing adult offenders. When adult offenders are convicted of crimes, they are sentenced. When juveniles are adjudicated delinquent, the judge makes a disposition. At least 12 different dispositions or sanctions are available to juvenile court judges if the facts alleged in petitions are upheld (Jarjoura et al., 2008). These dispositions are (1) nominal, (2) conditional, or (3) custodial options.

Juvenile offenders have the right to testify on court in their defense.

(© Design Pics Inc. / Alamy)

Nominal Dispositions

Nominal dispositions are either verbal warnings or reprimands and are the least punitive dispositional options. The nature of such verbal warnings or reprimands is a matter of judicial discretion. The youth is released to the custody of the parents or legal guardians, and this completes the juvenile court action (Foley, 2008). Nominal dispositions are most often utilized for low-risk, first offenders who may be considered the least likely to recidivate and commit new offenses (Abbott-Chapman, Denholm, and Wyld, 2007). The emphasis of nominal dispositions is on rehabilitation and fostering a continuing, positive, reintegrative relationship between the juvenile and his or her community (Ross, 2008).

Conditional Dispositions

Most conditional dispositions involve probation, which is the most frequently imposed sanction. Youth are placed on probation and required to comply with certain conditions for a specified period lasting from several months to a couple of years. The nature of the conditions to be fulfilled depends on the specific needs of the offender and the offense committed. If youth have alcohol or drug dependencies, they may be required to undergo individual or group counseling and some type of therapy to cope with substance abuse (McMorris et al., 2007). Juvenile court judges impose probation as a disposition more than any other sanction (Puzzanchera, Adams, and Sickmund, 2010).