the text book Practicing Texas Politics Texas Edition (16th Edition), Brown, et.al. for this assignment: 3,4,5,6,10,13.

Chapter10

Public Policy and Administration

Chapter Introduction

10-1 State Agencies and State Employees

10-1a State Agencies and Public Policy

10-1b The Institutional Context

10-1c State Employees and Public Policy

10-2 Education

10-2a Public Schools

10-2b Colleges and Universities

10-3 Health and Human Services

10-3a Human Services

10-3b Health and Mental Health Services

10-3c Employment

10-4 Economic and Environmental Policies

10-4a Economic Regulatory Policy

10-4b Business Promotion

10-4c Environmental Regulation

10-5 Chapter Review

10-5aConclusion

10-5bChapter Summary

10-5cKey Terms

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration Chapter Introduction

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

Chapter Introduction

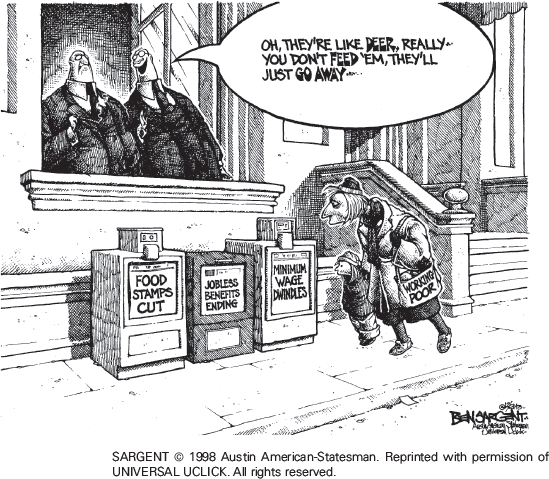

SARGENT © 1998 Austin American-Statesman. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK. All rights reserved.

Critical Thinking

Some groups in Texas are served well by public policy, others poorly. Why?

Learning Objectives

10.1 Describe the role of bureaucracy in making public policy in Texas.

10.2 Analyze the major challenges faced by the Texas education system.

10.3 Describe the health and human services programs in Texas and discuss how efforts to address the needs of its citizens have been approached.

10.4 Compare the roles of government in generating economic development while maintaining a safe and clean environment for the state's residents.

One good way to see what is important in public policy is to follow the money. For many years in Texas, the state government has spent the lion's share of the budget on four areas. For example, in the 2014–2015 biennium (two-year budget cycle), the legislature appropriated $200 billion as follows:

Education: 37 percent

Health and human services: 37 percent

Business and economic development: 13 percent

Public safety and criminal justice: 6 percent

Everything else: 7 percent

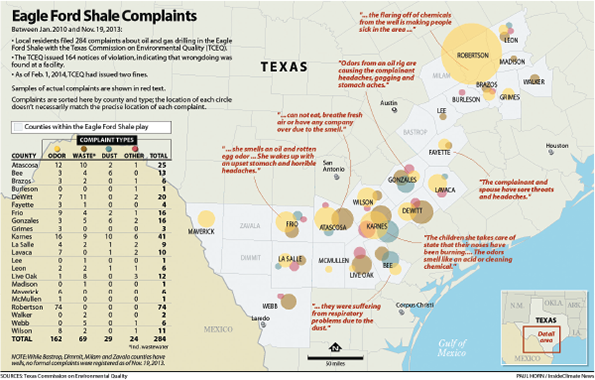

Although regulation costs the state government little (0.6 percent of the total in 2014–2015), it has profound cost effects on individuals, companies, and local governments. Regulation commonly shifts costs and benefits from one group to another. For example, contaminated air hurts the quality of life and increases medical costs for children with respiratory problems such as asthma, as well as for the elderly, but regulations requiring special equipment to reduce emissions from smokestacks cost businesses money. Not surprisingly, regulatory policy is fraught with controversy.

This chapter examines public policy in Texas through two lenses: (1) the situation and behavior of the agencies and people who implement the policies and (2) the nature of the policies themselves. Covered are the major policy areas of education, health and human services, business and economic development, and the environment. The other big-ticket item in Texas state government—public safety and criminal justice—is covered in Chapter 12, “The Criminal Justice System,” and details on state spending are provided in Chapter 13, “Finance and Fiscal Policy.”

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-1 State Agencies and State Employees

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-1 State Agencies and State Employees

LO 10.1

Describe the role of bureaucracy in making public policy in Texas.

Surprisingly, scholars who study public policy have not agreed on a single definition of it. However, many suggest the simple and useful definition utilized in this chapter: Public policyWhat government does or does not do to and for its citizens. is what government does or does not do to and for its citizens. Policy is both action, such as state or local governments raising or lowering speed limits, and inaction, such as Texas state government not accepting federal funds for expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare).

State government policies profoundly affect the lives of all of us. Services, subsidies, taxes, and regulations affect students from kindergarten through graduate school, the impoverished, the middle class, the wealthy, and small and large businesses. State policies affect our safety and health and the profitability of businesses. The impact of a given policy varies by group. (Who gets a tax cut? Who doesn't?) Thus, public policy is a source of great conflict because groups compete to gain benefits and reduce costs to themselves. As the opening cartoon suggests, some are better positioned than others to win this battle.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-1a State Agencies and Public Policy

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-1a State Agencies and Public Policy

Public policy is the product of a series of interactions among a variety of groups and institutions. Commonly, an interest groups begins the process by bringing problems to the attention of government and then lobbying for solutions that benefit the members of the group. Political parties and chief executives often select and combine the proposals of interest groups into a manageable number and push them as part of their program or agenda. The legislature then accepts some of the proposals through the passage of laws, the creation or modification of agencies, and the appropriation of money to carry out the policies. Finally, the executive branch implements the policies. At the national level, the president provides rules and instructions for the agencies that actually carry out the policies. In Texas, the more than 200 agencies have substantial independence from the governor, which means that each agency has more latitude and independence than federal agencies in deciding what was meant by the legislature and in applying the law to unforeseen circumstances. Not surprisingly, a great deal of informal interaction (and lobbying) occurs among Texas interest groups, political parties, top executives, legislators, and agencies themselves.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-1b The Institutional Context

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-1b The Institutional Context

The way in which the Texas executive branch is organized has a major effect on public policy. A key reason is that the fragmentation of authority strongly affects who has access to policy decisions, as well as how visible the decision process is to the public. The large number of agencies means they are covered less by the media and, therefore, are less visible to the public. The power of the one state official to whom the public pays attention (the governor) is limited. Special interest groups, on the other hand, have strong incentives (profits) to develop cozy relationships with agency personnel, and most agencies do not have to defend their decisions before a higher authority (such as the governor).

In addition to agencies headed by the elected officials discussed in Chapter 9, “The Executive Branch,” more than 200 boards, commissions, and departments implement state laws and programs in Texas. Most boards and commissions are appointed by the governor; however, once citizens are appointed to a board, the governor relies on persuasion and personal or political loyalty to exercise influence. The exceptionally long tenure of Governor Rick Perry meant that he appointed all of the members of most boards and developed a close working relationship with those agencies of special concern to him. For example, Governor Perry had a strong interest in his alma mater, Texas A&M University, and significantly influenced its direction through the policies and hiring decisions made by members of the board of regents of the Texas A&M University System (whom he appointed).

Fragmentation of the state executive into so many largely independent agencies was an intentional move by the framers of the Texas Constitution and later legislatures to avoid centralized power. Administering state programs through boards was also thought to keep partisan politics out of public administration. Unfortunately, this fragmentation simply changes the nature of the politics, making it more difficult to coordinate efforts and hold the agencies responsible to the public.

Boards governing state agencies are not typically full-time; instead, they commonly meet quarterly. In most cases, a full-time board-appointed executive director oversees day-to-day agency operations. Boards usually make general policy decisions and leave the details to the executive director; however, some boards are much more active and involved (for example, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality). In recent years, the governor's influence has increased through the ability to name a powerful executive commissioner to run two major agencies—the Health and Human Services Commission and the Texas Education Agency. Two important boards—the Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC) (which regulates the oil and gas industry) and the State Board of Education—are elected. Members of both tend to be quite active; however, the State Board of Education is limited by its lack of authority over the commissioner of education, who heads the Texas Education Agency and reports to the governor.

Some agencies were created in the Texas Constitution. Others were created by the legislature, either as directed by the state constitution or independent of it. As problems emerge that elected officials believe government must address, they look to existing state agencies or create new ones to provide solutions. Sometimes, citizen complaints force an agency's creation. For example, citizen outrage at rising utility rates resulted in the creation in 1975 of the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) to review and limit those rates. (Lobbying by special interest groups and the orientation of gubernatorial appointments over time, however, have changed the direction of the PUC's policies to again draw the ire of consumer advocates.) Lobbying by special interest groups to protect their own interests is also important in the creation of agencies. The most famous Texas case was lobbying by the oil and gas industry in the early 20th century to have the Railroad Commission create a system of regulation to reduce economic chaos in the fledgling industry.

The sunset review processDuring a cycle of 12 years, each state agency is studied at least once to see if it is needed and efficient, and then the legislature decides whether to abolish, merge, reorganize, or retain that agency. is an attempt to keep state agencies efficient and responsive to current needs. Each biennium, a group of state agencies is examined by the Sunset Advisory Commission, which recommends to the legislature whether an agency should be abolished, merged, reorganized, or retained. It is the legislature that makes the final decision. At least once every 12 years, each of 130 state agencies must be evaluated. (Universities and courts are not subject to the process.) The Sunset Advisory Commission is composed of 10 legislators (five from each chamber) and two public members. The commission has a staff of 32 employees. In 2014–2015, it reviewed 21 agencies, including the giant Health and Human Services Commission and the University Interscholastic League (UIL, which regulates public school competitions such as athletics), along with lesser known agencies such as the State Office of Administrative Hearings.

A major problem with the sunset review process, according to critics, is that the legislature has little taste for the abolition or major restructuring of large agencies. For example, the Sunset Advisory Commission's staff found that the mission and “byzantine” regulations of the Alcoholic Beverage Commission were hopelessly outdated, yet the legislature continued the commission with only minor changes. In the 2013 session, the legislature failed to pass the sunset bills making changes in the Texas Education Agency and the Railroad Commission but did pass bills continuing their existence. It is not surprising that regulated groups (often enjoying close relationships with friendly administrators and legislators) and state employees fighting for their jobs and turf (the agency's size, power, and responsibility) wage vigorous campaigns to preserve agencies and continue business as usual. From the Sunset Advisory Commission's authorization in 1977 through 2013, a total of 437 agencies were reviewed. Eighty-two percent were retained, 8 percent were abolished, and 10 percent were reorganized in major ways (such as combining two or more agencies). Of those agencies retained, some had changes, such as adding public members (people not from the regulated industry) on governing boards, improving procedures, or changing policies. According to the commission, from 1982 through 2013, the sunset process saved the state $946 million, or approximately $25 for every dollar spent in the sunset review process.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-1c State Employees and Public Policy

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-1c State Employees and Public Policy

For most people, the face of state government is the governor, legislators, and other top officials. Certainly, these people are critical decision makers. However, most of the work of Texas state government (called public administrationThe implementation of public policy by government employees.) is in the hands of people in agencies headed by elected officials and appointed boards. These bureaucratsPublic employees. (public employees), though often the subject of criticism or jokes about inefficiency and “red tape,” are responsible for delivering governmental services to the state's residents. The public may see them in action as a clerk taking an application, a supervisor explaining why a request was turned down, or an inspector checking a nursing home.

The nature of bureaucracy is both its strength and its weakness. Large organizations, such as governments and corporations, need many employees doing specialized jobs with sufficient coordination to achieve the organization's goals (profits for a company, service for a government). That means employees must follow set rules and procedures so they can provide relatively uniform results. When a bureaucracy works well, it harnesses individual efforts to achieve the organization's goals. Along the way, however, “red tape” (the rules and procedures that bureaucrats must follow) slows the process and prevents employees from making decisions that go against the rules. State rules should mean the same in Dallas as in Muleshoe, but making decisions may seem slow, and “street level” bureaucrats may not have the authority to make adjustments for differences in local conditions. Thus, bureaucracies are necessary but sometimes frustrating.

Bureaucracy and Public Policy

We often think of public administrators as simply implementing the laws passed by the legislature, but the truth is that they must make many decisions about situations not clearly foreseen in the law. Not surprisingly, their own views, their bosses' preferences, their agency's culture, and the lobbying they receive make a difference in how they apply laws passed by the legislature. Agencies also want to protect or expand their turf. Lobbyists understand the role of the bureaucracy in making public policy and work just as hard to influence agency decisions as they work to influence legislation.

Public agencies also must build good relations with state leaders (such as the governor), key legislators, and executive and legislative staff members because these people determine how much money and authority the agency receives. Dealing with the legislature often involves close cooperation between state agencies and lobbyists for groups that the agencies serve or regulate. For example, the Texas Good Roads/Transportation Association (mostly trucking companies and road contractors) and the Texas Department of Transportation have long worked closely, and relatively successfully, to lobby the legislature for more highway money.

In Texas, three factors are particularly important in determining agencies' success in achieving their policy goals: the vigor and vision of their leadership, their resources, and the extent to which elites influence implementation (called elite accessThe ability of the business elite to deal directly with high-ranking government administrators to avoid full compliance with regulations.). Many Texas agencies define their jobs narrowly and make decisions on narrow technical grounds, without considering the broader consequences of their actions. Texas environmental agencies have often taken this passive approach, which is one reason for Texas's many environmental problems. For example, a former Texas Commission on Environmental Quality commissioner complained:

One [issue] that always floored me was the high mercury level in East Texas lakes.… People were eating fish contaminated with levels of mercury that could only be attributed to pollution from nearby coal-fired power plants. Yet when permit applications for new coal plants came before the board, the majority of commissioners refused to consider the impact on area lakes. They said water issues are not relevant to air permits.… The regulators tasked with cleaning up the lake, meanwhile, considered airborne emissions to be beyond their purview. So the issue never gets addressed.

Other agency heads, however, take a proactive approach. Beginning in 1975, for example, three successive activist comptrollers transformed the Texas Comptroller's Office. It became a major player in Texas government, a more aggressive collector of state taxes, a problem solver for other agencies, and, under comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn, a focus of controversy. Elected agency heads, such as the comptroller and attorney general, have more clout (and perhaps incentive) to be proactive about their agency's job than do appointed agency heads.

Historically, Texas government agencies have had minimal funds to implement policy. Consider the example of nursing homes, which are big business today and mostly run for profit. A major problem is that almost two-thirds of nursing home residents depend on Medicaid to pay for their care. However, Medicaid rates, set by the state, have not gone up as fast as costs. For at least the last decade, Texas's rates have ranked 49th among the 50 states. Low rates make it increasingly difficult for nursing homes to make a profit. The less scrupulous companies maintain profits by cutting staff and services.

Nursing home residents are generally weak and unable to leave if the service is bad or threatens their well-being. Therefore, residents depend heavily on government inspectors to ensure that they are treated well. Unfortunately, the number of nursing home inspectors in Texas has been like a roller coaster—sometimes up, sometimes down. When the number of inspectors relative to the number of residents decreases, the number of inspections decreases, and abuse tends to increase. Even when there are enough inspectors, connections of nursing home company executives and lobbyists to top agency administrators often ensure that infractions result in a slap on the wrist and a promise to do better. (This process is called elite access.)

One study noted that Texas ranked 10th worst among the states in serious deficiencies per home but in the middle for the amount of average fines. A 2011 Texas State Auditor's report found that the Department of Aging and Disability Services (DADS) “rarely terminates its contracts with nursing facilities that have a pattern of serious deficiencies. In fiscal year 2010, the Department recommended contract termination for 372 nursing facilities. However, it reconsidered or rescinded all but one of those terminations.” Over the years, both the Health and Human Services Commission and the state attorney general have been criticized for their lack of fervor in pursuing nursing home violations.

As these reports indicate, elite access and lack of resources make policy less effective and abuse more common in Texas nursing homes. (Also contributing is Texas's shortage of nurses, in major part because of too few state nursing programs.) At least since the 1990s, Texas has had more severe and repeated violations of federal patient care standards than most other states. A study by a nursing home advocacy group ranked Texas the worst nursing home state, failing on six of eight statistical measures. A study by the Commonwealth Fund, the SCAN foundation, and AARP ranked Texas's long-term care system 42nd on quality of care, due largely to poor nursing home ratings. Harm to residents can include neglect, physical and verbal abuse, injury, and death. For-profit nursing homes tend to do more serious and repeated harm to residents than do government and nonprofit homes. Clearly, bureaucrats do greatly affect policy, and their decisions impact people's lives.

Number of State Employees

Governments are Texas's biggest employers. In 2012, the equivalent of 311,000 Texans drew full-time state paychecks. Put another way, Texas had 119 full-time state employees for every 10,000 citizens. Although this number sounds like a lot, Texas ranked 43rd of the 50 states in number of state employees per 10,000 citizens. Texas is following a national pattern. More populated states tend to have fewer employees relative to their population. Thus, as populations grow, most states, including Texas, are hiring proportionately fewer employees. From 1993 to 2012, the number of state employees declined relative to the population in both Texas and the nation. This decline is because of the economies of scale (meaning that as agencies grow, they may require more total employees but not as many relative to the population they serve; for example, as demand increases, many employees may be able to process more cases in the same amount of time). Another reason Texas ranks so low compared to other states is that Texas state government passes a great deal of responsibility to local governments. In 2012, Texas local governments employed 1,105,000 workers, or 424 per 10,000 residents, placing Texas seventh among the 50 states. Moreover, as with local governments in other states, local government employment in Texas is increasing faster than the state's population.

Competence, Pay, and Retention

Although most public administrators do a good job, some are less effective than others. Many observers believe that bureaucratic competence improves with a civil service system along with good pay and benefits. In the first century of our nation, many thought that any fool could do a government job, and as a result, many fools worked in government. From local to national levels, government jobs were filled through the patronage systemHiring friends and supporters of elected officials as government employees without regard to their abilities., also known as the spoils system. Government officials hired friends and supporters, with little regard for whether they were competent. The idea was that “to the victor belong the spoils.” Merit systemsHiring, promoting, and firing on the basis of objective criteria such as tests, degrees, experience, and performance., on the other hand, require officials to hire, promote, and fire government employees on the basis of objective criteria such as tests, education, experience, and performance. If a merit system works well, it tends to produce a competent bureaucracy. A merit system that provides too much protection, however, makes it difficult to fire the incompetent and gives little incentive for the competent to excel.

Texas has never had a merit system covering all state employees, and the partial state merit system was abolished in 1985. What replaced it was a highly centralized compensation and classification system covering most of the executive branch but not the judicial and legislative branches or higher education. The legislature sets salaries, wage scales, and other benefits. Individual agencies are free to develop their own systems for hiring, promotion, and firing (so long as they comply with federal standards, where applicable). Critics worried that the result would be greater turnover and lower competence. A survey of state human resource directors, however, indicates that agencies have developed more flexible personnel policies that provide some protection for most employees. Moreover, patronage appointments have not become a major problem in state administration. In the words of one observer, “It's not uncommon for state agencies to become repositories for campaign staff or former officeholders.… But there are no wholesale purges” when new officials are elected.

In Texas, most employees (public and private) are “at will”—that is, they can be fired or can quit for good, bad, or no reason. The employment relationship is voluntary. Generally, only those under a contract or union agreement are not “at will” employees. The employer cannot fire a person for illegal reasons, such as race, retaliation for reporting illegal activity, or exercising civil liberties. For example, in a Virginia case, a federal appeals court held that a sheriff violated his employees' free speech rights by firing them for “liking” his opponent's campaign site on Facebook.

In recent years, Texas state government employee turnover has been consistently high: 14 to 17 percent in fiscal years 2003–2010. By comparison, in fiscal year 2004, turnover was 9 percent for Texas's local governments and 10 percent for the nation. In that year, turnover cost the state government $345 million, according to the State Auditor's Office. Turnover is highest for workers in social services and criminal justice. Exit surveys (filled out by employees leaving state employment) reveal that the top three reasons for leaving state employment are retirement, desire for higher pay or better benefits, and desire for more satisfactory working conditions. Note in “How Do We Compare … in State Employee Compensation?” that state government salaries in Texas tend to be higher than those of our neighbors but lower than those of other large states. In 2009, the legislature increased the number of state positions with salaries that compare favorably with Texas's private sector from approximately 56 to 83 percent. The higher wages and the recent recession have contributed to holding down turnover.

How Do We Compare … in State Employee Compensation?

Average Monthly Pay per Full-Time-Equivalent (FTE) Employee, 1993 and 2012

Source: Calculations by author based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 Census of Governments, and 2010 Annual Survey of Public Employment and Payroll, revised January 2012, http://www.census.gov//govs/apes/historical_data_2010.html.

Critical Thinking

What factors would account for the wide variations in pay shown in the table?

Other nonfinancial factors help attract state employees. Studies consistently show that large numbers of government employees have a strong sense of service and thus find being a public servant rewarding. Three “perks” also increase the attractiveness of public employment: paid vacations, state holidays, and sick leave.

Learning Check 10.1

True or False: Public administrators simply implement the laws passed by the legislature without making any changes.

What three factors are particularly important in determining how successful agencies are in achieving their policy goals?

Another incentive for employment can be equitable treatment. For many years, Texas state government has advertised itself as an “equal opportunity employer,” and evidence indicates that it has been, albeit imperfectly. Table 10.1 shows that women make up more than one-half of state employees and are more likely to hold higher positions (official, administrator) in government than in the private economy. Women and African Americans make up a greater proportion of public than private employment, whereas Latino Texans are more likely to be employed in the private economy. In relation to their numbers in the state's population, Latinos are underrepresented in the top job categories in both the public and private arenas. Data on newly hired state employees indicate that these patterns will probably continue.

Table 10.1

Texas Minorities and Women in State Government Compared with the Total Civilian State Workforce (in percentage)

Note on interpretation: The first cell indicates that 10 percent of Texas government officials and administrators are African American; the next cell to the right shows that 9 percent of the officials and administrators in the state's total economy are African American.

Source: Compiled from Texas Workforce Commission, Civil Rights Division, January 11, 2013, Equal Employment Opportunity and Minority Hiring Practices Report, Fiscal Years 2011–2012, http://www.twc.state.tx.us/news/eeo-minority-hiring-2013.pdf.

Critical Thinking

Where are there larger differences between the government and total workforce? Why?

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-2 Education

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-2 Education

LO 10.2

Analyze the major challenges faced by the Texas education system.

After a legislative hearing on health problems along the Mexican border, Representative Debbie Riddle (R-Tomball) asked an El Paso Times reporter, “Where did this idea come from that everybody deserves free education, free medical care, free whatever? It comes from Moscow, from Russia. It comes straight out of the pit of hell.” While this phrasing is extreme, education and social services are controversial in Texas.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-2a Public Schools

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-2a Public Schools

Texas's commitment to education began with its 1836 constitution, which required government-owned land to be set aside for establishing public schools and “a University of the first class.” Later, framers of the 1876 constitution mandated an “efficient system of public free schools.” What continues to perplex state policymakers is how to advance public schools' efficiency while seeking equality of funding for students in districts with varying amounts and values of taxable property. (See Chapter 13, “Finance and Fiscal Policy,” for a discussion of school finance issues.) Texas schools are also faced with meeting the needs of a changing student body.

In the 21st century, students have come increasingly from families that are ethnic minorities or economically disadvantaged. According to Texas Education Agency data, in the 2012–2013 academic year, 51 percent of Texas students were Latino, 30 percent Anglo, 13 percent African American, 4 percent Asian, and 2 percent other (multiracial, Native American, and Pacific Islander). In addition, 60 percent of Texas students were economically disadvantaged (those eligible for free or reduced-price lunches). Historically, Texas has not served minority and less affluent students as well as it has Anglo and middle-class students. If this pattern continues, studies project that Texans' average income will decline, while the costs of welfare, prisons, and lost tax revenues will increase. Table 10.2 looks at how Texas's educational efforts and outcomes compare to those of other states.

Table 10.2

Effort and Outcomes in Texas Education (Rank Among the 50 States)

| Texas Public Schools | Texas Public Higher Education | ||

| State and local expenditure per pupil | 39th | Expenditure per full-time student | 12th |

| Average teacher salary | 33rd | Average faculty salary | 27th |

| High school graduation rate | 44th | Average tuition and fees at public universities | 27th |

| Percent of students scoring Advanced or Proficient in math on NAEP | 8 states higher, 22 lower, 9 similar | Percent of population with a bachelor's degree or higher | 30th |

| Percent of students scoring Advanced or Proficient in reading on NAEP | 29 states higher, 5 lower, 5 similar | ||

| Percentage of high school students who play on a sports team | 12th | ||

Source: Legislative Budget Board, Texas Fact Book, 2012, http://www.lbb.state.tx.us; Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2012 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac, http://www.thecb.state.tx.us; and National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2013, http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/.

Critical Thinking

Education is often said to be important to individuals, the state, and the nation. But how serious are we? Do the numbers above suggest that Texas is seeking or achieving the excellence in education that it could?

One indication that the state can do better comes from U.S. News and World Report's ranking of the nation's best high schools (based on criteria such as college readiness and geometry and reading proficiency). Of 1,492 Texas high schools examined, 357 made the 2014 list. Fourteen Texas high schools were ranked among the top 100 in the nation, including the nation's highest ranked school, Dallas's School for the Talented and Gifted. Three schools making the top 100 were located in Donna, Mercedes, and Brownsville, all in South Texas. Of the 14 high-achieving schools, 12 had a non-Anglo majority, and 8 had a majority of economically disadvantaged students.

Today, more than 1,000 independent school districts and about 200 charter operators shoulder primary responsibility for delivery of educational services to 5 million students. (Chapter 3, “Local Governments,” discusses the organization and politics of local school districts.) Although local school districts have somewhat more independence than in the past, they are part of a relatively centralized system in which state authorities substantially affect local decisions, from what is taught to how it is financed.

State Board of Education

Oversight of Texas education is divided between the elected State Board of Education (SBOE)A popularly elected 15-member body with limited authority over Texas's K–12 education system. and the commissioner of education, who is appointed by the governor to run the Texas Education Agency. Over the years, the sometimes extreme ideological positions taken by many SBOE members have embarrassed the legislature and caused it to whittle away the board's authority. For several years, the board was even made appointive rather than elective. Today, the greater power over state education is in the hands of the commissioner of education through control of the Texas Education Agency, but the SBOE remains important and highly controversial.

Among the board's most significant powers are curriculum approval for each subject and grade, textbook review for public schools, and management of investment of the Permanent School Fund. Revenue from the $29 billion fund goes to public schools ($1.9 billion in the 2012–2013 biennium). Among other things, it pays for textbooks and guarantees more than $55 billion in bonds for school districts. (The guarantee allows districts to pay lower interest rates on their bonds.)

Representing districts with approximately equal population (1.8 million), the 15 elected SBOE members serve without salary for overlapping terms of four years. The governor appoints, with Senate confirmation, a sitting SBOE member as chair for a two-year term.

Deep ideological differences divide the board. The ideological split also follows partisan and ethnic lines. The socially conservative members tend to be Anglo Republicans, whereas the moderate and liberal members are commonly African American and Latino Democrats. Openly hostile debates on subjects such as textbook adoption and public criticism of possible conflicts of interest in the selection of investment managers and independent financial consultants for the Permanent School Fund have been common. The clashes have led some legislators to advocate reforming board procedures and others to call for elimination of the SBOE.

Probably the most contentious issue facing the SBOE is its periodic review of textbooks. Books for the foundation curriculum (English, math, science, and social studies) are reviewed at least once every eight years; other textbooks may have a longer cycle. The SBOE places a book on an accepted or rejected list. To be eligible for adoption, instructional materials must cover at least 50 percent of the elements of the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) for its subject and grade level. Approved books must also meet the SBOE's physical specifications (for example, quality of binding and paper). Recently, the number of electronic books and instructional materials has been increasing, although traditional paper materials still predominate. Books must be free of factual errors. Critics charge that some board members have interpreted this requirement to mean that ideas conflicting with their own views are errors.

A long-standing source of conflict has been the challenge to the theory of evolution by supporters of creationism and intelligent design. The board's debate over the TEKS social studies standards in 2010 was particularly harsh and was described by some as a “culture war.” In 2014, in a rare display of compromise, the board responded to a request for Mexican American studies by putting out a request for materials for use in Mexican American studies and courses that highlight contributions from African Americans, Native Americans, and Asian Americans.

Individual school districts make their own textbook adoption decisions. Traditionally, the state paid 100 percent of the cost if local school districts used books on the approved lists but not more than 70 percent for books not on the adoption lists. This rule made SBOE approval very important to the cash-strapped districts. However, in 2011, the legislature created an Instructional Materials Allotment that districts can use to buy books and materials regardless of SBOE approval. This change is reducing the significance of board textbook approval. The change is also of great importance to other states. Texas, California, and Florida purchase huge numbers of textbooks (more than 48 million textbooks a year in Texas). Thus, publishers cater to these markets. Other states have complained that their textbook options are limited to books published for one or more of the three big “state adoption” markets.

Texas Education Agency

Which level of government should make educational policy? The local level, according to many Texans. Local officials know local needs, and most parents and citizens believe that they should have a say. However, many public officials and scholars who study education believe that the broader, more professional perspective found at the state or national level encourages higher educational standards. Texas responds to both of these views. Local school boards and superintendents run the schools, but almost all of their decisions are shaped by state and, to a much smaller extent, federal rules and procedures. The U.S. Department of Education provides some financial assistance, requires nondiscrimination in several areas (including race, gender, and disability), and, under the No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top programs, demands extensive testing.

In the Lone Star State, the Texas Education Agency (TEA)Administers the state's public school system of more than 1,200 school districts and charter schools., headquartered in Austin, has fewer than 700 employees. Created by the legislature in 1949, the TEA today is headed by the commissioner of educationThe official who heads the TEA., appointed by the governor to a four-year term with Senate confirmation. Under Governor Rick Perry, commissioners were closely connected and responsive to the governor. The TEA has the following powers:

Oversees development of the statewide curriculum

Accredits and rates schools (during 2012–2014, the rating system was under review)

Monitors accreditation (whenever a local school district or school fails to meet state academic or financial standards for consecutive years, TEA has a range of sanctions, including changing its leaders and closure)

Oversees the testing of elementary and secondary school students

Serves as a fiscal agent for the distribution of state and federal funds (administers about three-fourths of the Permanent School Fund and supervises the Foundation School Program, which allocates state money to independent school districts)

Monitors compliance with federal guidelines

Approves new charter schools and supervises existing ones (moved from the SBOE by the legislature in 2013)

Grants waivers to schools seeking charter status and exemptions from certain state regulations

Manages the textbook adoption process, assisting the State Board of Education and individual districts

Administers a data collection system on public school students, staff, and finances, and operates research and information programs

Handles the administrative functions of the State Board for Educator Certification (placed under TEA in 2005 as part of the sunset review process)

Much of what the TEA does goes unnoticed by the general public, but some decisions receive considerable attention and have effects beyond education. The ratings of schools are advertised to draw home buyers into neighborhoods and subdivisions, and the decision to close a school or school district has profound effects on the community it serves. Thus, TEA has been cautious and taken less drastic steps before closing schools or districts. One of the few districts closed by TEA is the North Forest ISD in northeast Houston. After decades of warnings and interventions, the district was marked for closure in 2011, then given a reprieve, and finally combined with the Houston ISD in 2013.

Charter Schools

In 1995, the legislature authorized the SBOE to issue charters to schools that would be less limited by TEA rules. There was hope that with greater flexibility, these schools could deal more effectively with at-risk students. Compared with students at traditional schools, charter school students are more economically disadvantaged, more are African American, slightly more are Latino, and fewer are Anglo. Although charter schools are public schools, they draw students from across district lines, use a variety of teaching strategies, and are exempt from many rules, such as state teacher certification requirements. Charters are granted to nonprofit corporations that, in turn, create a board to govern the school. The particular organization varies from school to school. Charter schools cannot impose taxes but can now issue bonds for new construction. They receive most of their funding from the state, with the rest coming from federal and private sources. Thus, most charter schools have less revenue per pupil than do traditional schools ($1,703 less per student in terms of ADA [Average Daily Attendance] in 2013–2014). In addition, charter schools have to spend part of the state money on facilities (an average of $829 per student). In early 2014, Texas had 552 charter school campuses serving 179,000 students (which is less than 4 percent of all public school students). In 2013, the Texas legislature passed a major revision of charter school regulations, including raising the cap on the number of charters granted from 215 in 2013 to 305 in 2019. The legislation also made the commissioner of education responsible for initial charter approval.

The effectiveness of charter schools in meeting the needs of at-risk students is sharply debated. Some Texas charter schools have “compiled terrific records of propelling minority and low-income kids into college.” In the 2014 U.S. News and World Report listing of the nation's best high schools, three of the 10 best high schools in Texas were charter schools: Yes Prep North Central in Houston (28th in the nation), IDEA Academy and College Preparatory School in Donna (South Texas, 30th), and Kipp in Austin (63rd). Some other charter schools have been marked by corruption and academic failure. A study by Stanford University researchers found that results varied by state. In Texas, the researchers compared the progress of students of comparable background in charter and traditional schools and found that Latino and African American students tended to do better in traditional schools, whereas students in poverty (including all ethnicities) tended to fare slightly better in charter schools.

Testing

Educators and political leaders are sharply divided about how to assess student progress and determine graduation standards. Nevertheless, testing as a major assessment tool is now federal and state policy. Texas first mandated a standardized test in 1980 and began to rely heavily on testing in 1990. An essential component of the state testing program is the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS)A core curriculum (a set of courses and knowledge) setting out what students should learn., a core curriculum that sets out the knowledge students are expected to gain. This curriculum is required by the legislature and is approved by the State Board of Education.

The current testing program is the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness (STAAR)A state program of end-of-course and other examinations begun in 2012.. Mandated by the legislature in 2007 and 2009, STAAR went into effect in the spring of 2012. It included a number of key mandates:

End-of-course examinations in the four high school core subject areas (math, science, English, and social studies).

A requirement to pass both end-of-course tests and courses in order to graduate.

For grades 3–8, new tests to assess reading and math for each level, as well as writing, science, and social studies for certain grade levels.

The new tests and curriculum to be more closely tied to college readiness and preparation for the workplace.

The new tests to be more rigorous and standards to be gradually raised through 2016.

In the first round of STAAR tests, statewide passing rates for freshmen varied from 55 percent for writing to 87 percent for biology. However, if the 2016 standards had been applied, a majority of students would have failed in each subject. Not surprisingly, the results were met with controversy.

Increasing the number of tests, how much they count, and their level of difficulty caused a strong backlash. In 2013 the legislature decreased the number of end-of-course tests to five and cut testing for high-performing students in grades 3–8. Although testing continues to be a major part of Texas's education policy, the testing program was in a period of transition in 2014, the outcome of which was not clear.

One of the most controversial aspects of the testing programs is that test results are used to evaluate teachers, administrators, and schools. This practice is intended to increase “accountability”—that is, to hold teachers and administrators responsible for increasing student learning. Many educators object to having their pay—and perhaps their job—depend on student performance because student success is so much affected by students' backgrounds and home environments. The use of test results for accountability is continued under STAAR; however, the ratings were temporarily suspended in 2012 to allow development of a new system. For 2014, schools had to meet performance targets on each of four indexes (student achievement, student progress, disadvantaged students closing performance gaps, and postsecondary readiness). Schools were labeled: Met Standard, Met Alternative Standard (both are acceptable), or Improvement Required (unacceptable).

From its beginning, the statewide testing program has drawn cries of protest from many parents and educators. Social conservatives argue that the program tramples on local control of schools, whereas African American and Latino critics charge that the tests are discriminatory. Educational critics complain that “teaching to the test” raises scores on the test but causes neglect of other subjects and skills. Questions are also raised when the federal No Child Left Behind program sometimes produces substantially different evaluations of schools than does the Texas system (because they use different criteria). Supporters of testing argue that the policy holds schools responsible for increasing student learning. As proof, they point to the improved test scores of most groups of students since the program began.

Because test results are so important to both students and their schools, there has been controversy over how high standards should be. Some parents and advocates for disadvantaged students argue that standards are too high. Other critics argue that the previous test (Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills, or TAKS) suffered from grade inflation—that is, scores increased because of low standards, not student improvement. In January 2012, education commissioner Robert Scott, who led much of the development of the use of tests as a policy tool, said that testing had become a “perversion.” Over the previous decade, he argued, too much reliance had been placed on tests. He wanted test results to be “just one piece of the bottom line, and everything else that happens in a school year is factored into that equation.”

In August 2012, following Scott's resignation, Governor Perry named former Railroad Commissioner Michael Williams to head the agency.

Some critics believe that national tests such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) are better measures because they are not “taught to.” The NAEP shows mixed results for Texas. For example, between 1990 and 2013, math scores on the NAEP for Texas eighth graders improved significantly for each major ethnic group and economic level. The gap in scores between African American and Anglo eighth graders narrowed, as did the gap between the less and more affluent. However, the gap between Latinos and Anglos was not significantly different. On the other hand, on the eighth-grade reading test, the scores over the years were flat, and the score gap did not substantially improve for African American, Latino, or economically disadvantaged students.Table 10.2 compares NAEP scores in Texas to those of other states. The results are mixed.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-2b Colleges and Universities

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-2b Colleges and Universities

Texas has many colleges and universities—103 public and 44 private institutions of higher education serving more than 1.6 million students annually. There is also a growing number of for-profit and nonprofit online institutions. This large and growing number of institutions reflects several factors: the early tradition of locating colleges away from the “evils” of large cities, the demand of communities for schools to serve their needs, the desire to make college education accessible to students, and the growing popularity of online programs. Most potential Texas students live within commuting distance of a campus. Public institutions include 37 universities, nine health-related institutions, 50 community college districts (many with multiple campuses), three two-year state colleges, and four colleges of the Texas State Technical College System. All receive some state funding and, not surprisingly, state regulation.

Texas has three universities widely recognized as being among the prestigious tier-one national research universities: Rice University (private), the University of Texas at Austin (public), and Texas A&M University in College Station (public). All three are ranked by U.S. News and World Report among the top 100 national universities, along with three private schools, SMU, Baylor, and TCU. Three other Texas universities made the second 100: UT-Dallas at 142nd, Texas Tech (161st), and University of Houston (190th).

Among public universities, UT-Austin and A&M-College Station are commonly referred to as the state's “flagship” universities; they have traditionally been the most prestigious academically and the most powerful politically. Most observers believe that Texas needs more flagship universities to serve the increasing number of highly qualified students and to carry out the research necessary to attract new businesses and grow the economy. In 2009, a constitutional amendment gave access to funding through the Texas Research Incentive Program that encourages seven other universities to try to join the list of tier-one universities: the Universities of Texas at Arlington, Dallas, El Paso, and San Antonio; Texas Tech University; University of Houston; and University of North Texas. In 2012, Texas State University–San Marcos was added to the list of emerging research institutions by the Higher Education Coordinating Board. To achieve tier-one status, each school will have to raise more money and produce more research and successful doctoral graduates. There are no universally accepted criteria for tier-one status. Having met some of the common criteria, including a listing by the Carnegie Foundation, the University of Houston advertises itself as a tier-one university.

Most Texas universities are members of a system governed by a board of regents and managed by a chancellor and other administrators. The University of Texas and Texas A&M University have evolved into large systems with multiple campuses spread across the state. Four universities are not members of a system (for example, Texas Woman's University), and the rest are part of four other university systems (for example, the Texas State University System). The Texas Almanac lists Texas state and private schools and indicates their systems.

Boards of Regents

Texas's public university systems, public universities outside the systems, and the Texas State Technical College System are governed by boards of regents. Regents are appointed by the governor for six-year terms with Senate approval. A board makes general policy, selects each university's president, and provides general supervision of its universities. In the case of systems, the board usually selects a chancellor to handle administration and to provide executive leadership. The president of one of the universities may simultaneously serve as chancellor. Day-to-day operation of the universities is in the hands of the individual school's top officials (commonly the president and the academic vice president, though terminology varies). Governance of community colleges is by local boards, as discussed in Chapter 3, “Local Governments.”

Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board

The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB)An agency that provides some coordination for the state's public community colleges and universities. is not a super board of regents, but it does provide some semblance of statewide direction for all public (not private) community colleges and universities. In the 2013 sunset review process, the legislature significantly changed the agency's focus from regulation of public higher education to coordination. The sunset bill removed significant parts of the agency's authority, including the power to consolidate or eliminate low-producing academic programs and to approve capital projects. Other changes adopted during the sunset process aim to improve the effectiveness of the agency's coordination efforts and its relationship with higher education institutions through paying more attention to their input.

The nine members of the board receive no pay and are appointed by the governor to six-year terms with Senate approval. Gubernatorial power also extends to designating two board members as chair and vice chair, with neither appointment requiring Senate confirmation. Governors have substantial influence over higher education because they generally have a close relationship with the board. The commissioner of higher education, who runs the agency on a day-to-day basis and plays a significant role in higher education policy, is appointed (and can be removed) by the board.

Students in Action

Booze and Ballots: A Tale of Two Different Times

“We involved a lot of students in the public sphere for the first time, and some continued to be involved. We saved some lives and had a lot of fun.”

— Anonymous

Texas law allows citizens of almost any political entity to vote their area wet (the sale of alcohol is allowed) or dry (the sale of alcohol is prohibited). Walker County, home of Huntsville and Sam Houston State University (Sam), voted dry in 1914 and remained so until 1971. That year, Citizens for a Progressive Huntsville, composed mainly of Sam students and led by two students, circulated a petition for an election to permit alcohol sales within the city. Most of the 916 who signed the petition were thought to be Sam students or faculty. Townspeople were reluctant to sign the petition because others could see their names on the list. When the vote was held by secret ballot, however, all four voting boxes favored a wet community, which won with 62 percent of the votes. An estimated 800 students voted (out of 3,118 total votes).

In 2008, a Sam student ran unsuccessfully for the Huntsville City Council. Although it was not part of his public message, he told fellow students that his major concern was to extend bar hours from 12 midnight to 2 a.m. Even so, he couldn't get his own fraternity brothers out to the polls.

In 1971, in the wet issue, campus activists found a concern that could pull together students of widely varying views. Nearly 40 years later, the presidential election of 2008 produced a larger-than-usual student vote, but there was no local student-led movement to capitalize on the bar hours issue.

What's the Advice to Students?

“Sometimes it takes an issue like booze to get people interested enough to act on other, more important matters.”

Sources: Interviews and archives of the Walker County Clerk, City of Huntsville, and the Huntsville Public Library.

© Andresr/Shutterstock.com

Higher Education Issues

Two sets of issues have challenged Texas higher education in recent years: funding and affirmative action. Funding and the sharp increase in tuition rates are discussed in Chapter 13, “Finance and Fiscal Policy,” but we address affirmative action in the following paragraphs.

Improving the educational opportunities of Texas's ethnic minorities and the economically disadvantaged is an important but controversial issue, and one with a long history in the state. A 1946 denial of admission to the University of Texas law school on the grounds of race led to the “landmark [U.S. Supreme Court] case, Sweatt v. Painter, that helped break the back of racism in college admissions” throughout the country. Texas's long history of official and private discrimination still has consequences today. Although many Latinos and African Americans have become middle class since the civil rights changes of the 1960s and 1970s, both groups remain overrepresented in the working class and the ranks of the poor. To overcome this problem, in 2000 the THECB adopted an ambitious program, called Closing the Gaps, to increase college enrollment and graduation rates for all groups by 2015. The program has been quite successful. By 2014, African American enrollment in higher education was on target to double the 2015 goals. Latinos had doubled their enrollment but were at 86 percent of target levels. Anglo participation was down slightly. In terms of graduation or receipt of certificates, both Latinos and African Americans were on track to reach the 2015 goals. Women were enrolled and graduating at significantly higher rates than men.

A study financed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation concluded that if the goals of Closing the Gaps were achieved, “When all public [state and local] and private costs are considered, the annual economic returns per $1 of expenditures by 2030 are estimated to be $24.15 in total spending, $9.60 in gross state product, and $6.01 in personal income.”

Texas colleges and universities commonly describe themselves as equal opportunity/affirmative action institutions. Equal opportunityEnsures that policies and actions do not discriminate on factors such as race, gender, ethnicity, religion, or national origin. simply means that the school takes care that its policies and actions do not produce prohibited discrimination, such as denying admission on the basis of race or sex. Affirmative actionTakes positive steps to attract women and members of racial and ethnic minority groups; may include using race in admission or hiring decisions. means that the institution takes positive steps to attract women and minorities. For most schools, this means such noncontroversial steps as making sure that the school catalog has pictures of all groups—Anglos and minorities, men and women—and recruiting in predominantly minority high schools, not just Anglo schools. However, some selective admission universities have actively considered race along with other factors in admissions and aid, and other schools have had scholarships for minorities. This side of affirmative action has created confict.

Some Anglo applicants denied admission or scholarship benefits challenged these affirmative action programs in the courts. In the case of University of California v. Bakke (1978), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that race could be considered as one factor, along with other criteria, to achieve diversity in higher education enrollment; however, setting aside a specific number of slots for one race was not acceptable. Relying on the Bakke decision, the University of Texas Law School created separate admission pools based on race and ethnicity, a practice the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals declared unconstitutional in Hopwood v. Texas (1996).

In 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court issued two rulings on affirmative action. In the Michigan case of Grutter v. Bollinger, the court ruled that race could constitute one factor in an admissions policy designed to achieve student body diversity;

on the same day in another Michigan case, Gratz v. Bollinger, the court condemned the practice of giving a portion of the points needed for admission to every underrepresented minority applicant.

After the Hopwood ruling, Texas schools looked for ways to maintain minority enrollment. In 1997, Texas legislators mandated the top 10 percent ruleTexas law gives automatic admission into any Texas public college or university to those graduating in the top 10 percent of their Texas high school class, with limitations for the University of Texas at Austin., which provided that the top 10 percent of the graduating class of every accredited public or private Texas high school could be admitted to tax-supported colleges and universities of their choosing, regardless of admission test scores. Thus, the students with the best grades at Texas's high schools, including those that are heavily minority, economically disadvantaged, or in small towns, can gain admission. The top 10 percent rule has helped all three groups. For students not admitted on the basis of class standing, the University of Texas at Austin used a “holistic review” of all academic and personal achievements, which might take into consideration family income, race, and ethnicity (with no specific weight and no quotas). The use of race in the holistic review produced another court challenge (Fisher v. University of Texas), which was heard before the U.S. Supreme Court during the fall of 2012. The Court held that a university's use of race must meet a test known as “strict scrutiny,” meaning that affirmative action will be constitutional only if it is “narrowly tailored.” Courts can no longer simply accept a university's determination that it needs to consider race to have a diverse student body. Instead, courts themselves will need to confirm that the use of race is “necessary.” The Supreme Court sent the case back to the Fifth Circuit Court, which in July 2014 upheld the university's use of race in admissions. An appeal was expected.

In fall 2010 through fall 2013, Anglos were a minority of incoming University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin) freshmen—46 to 48 percent—although they remained a majority of the total student body until 2012. In 2003–2004, Texas A&M University announced that it would not use race in admissions decisions but would increase minority recruiting and provide more scholarships for first-generation, low-income students. (First-generation students are the first in their immediate family to attend college.) A&M also dropped preferences for “legacies” (relatives of alumni), who were predominantly Anglo. A&M's freshmen and transfers were 60 percent Anglo in fall 2013. All Texas institutions of higher education are under mandate from the Higher Education Coordinating Board to actively recruit and retain minority students under its Closing the Gaps initiative.

Learning Check 10.2

Which two state government entities are most important for public schools?

What is the “top 10 percent rule” in Texas higher education?

The top 10 percent rule is controversial, especially among applicants from competitive high schools denied admission to the state's flagship institutions—the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University. In fall 2009, 86 percent of students offered admission to the University of Texas at Austin qualified by the top 10 percent rule, a situation that left little room for students to be admitted on the basis of high scores or other talents (such as music or leadership). According to the university's president, even football might have had to be abolished. In response, the 2009 legislature modified the rule so that UT-Austin would not have to admit more than 75 percent of its students on the basis of class standing. The class standing that the university chose for admission varied by year: top 8 percent for fall 2011 and 2013, 9 percent for 2012, and 7 percent for 2014 and 2015. The 75 percent cap is in effect only through the 2015 school year, unless it is renewed by the legislature.

Point/Counterpoint

Should Texas Continue to Use the “Top 10 Percent Rule”?

THE ISSUE To promote diversity in Texas colleges and universities without using race as an admission criterion, the state legislature in 1997 passed a law guaranteeing admission to any public college or university in the state to Texas students who graduate in the top 10 percent of their high school class. The law sought to promote greater geographic, socioeconomic, and racial/ethnic diversity. The law applies to all public colleges and universities in the state, but it has had its greatest effect on the two flagship universities, the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University—prestigious schools with more qualified applicants than they can admit. The rule has increased minority representation at both schools but more so at the University of Texas. In 2009, the legislature capped automatic admission to the University of Texas at Austin at 75 percent through the 2015–2016 academic year.

| Arguments For the Top 10 Percent Rule | Arguments Against the Top 10 Percent Rule |

|

|

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 10: Public Policy and Administration: 10-3 Health and Human Services

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

10-3 Health and Human Services

LO 10.3

Describe the health and human services programs in Texas and discuss how efforts to address the needs of its citizens have been approached.

Most people think of Texas as a wealthy state, and indeed there are many wealthy Texans and a substantial middle class. Texas, however, also has long been among the states with the largest proportion of its population in poverty. Texas's 2011–2012 poverty rate was the sixth highest in the nation at 23 percent. From 1980 to 2012, Texas's poverty rate varied from 15 to 23 percent of the population. Poverty is particularly high for children and minorities, as can be seen in detail in Table 10.3. Poverty is defined in terms of family size and income. In 2014, for a family of three, poverty was an annual family income of less than $19,790; for a family of four, it was $23,790.

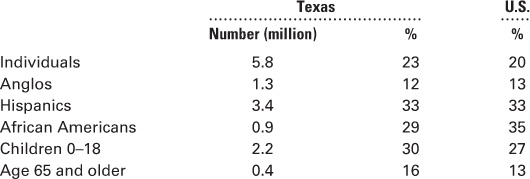

Table 10.3

Who's in Poverty in Texas and the United States? (2011–2012)

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, “State Health Facts,” 2014, http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/. Based on U.S. Census Bureau, March 2012 and 2013 Current Population Surveys.

Critical Thinking

Why is poverty so substantial and persistent in Texas?

Even more Texans are low income, meaning they earn an income above the poverty line but insufficient income for many “extras,” such as health insurance. (A common measure of low income is an income up to twice the poverty level. In 2010, more than one in five Texans fell into this category—that is, between 101 and 200 percent of the poverty level.)

Access to health care is a national issue that is even more acute in Texas. Although the state's major cities have outstanding medical centers, they are of little use to those who lack the resources to pay for care. For at least the last decade, studies comparing health care in the various states consistently rank Texas near the bottom. For example, from 2007 to 2014, the Commonwealth Fund, a well-respected foundation, did five state-by-state comparisons of various aspects of health system performance. All ranked Texas in the bottom quarter of the states. In 2014, the Lone Star State ranked 44th.

A key factor in access to health care is health insurance. Texas has led the nation in the proportion of people without health insurance since at least 1988. About one in four Texans has no health insurance, as compared with one in six in the nation. Texas also leads in the proportion of uninsured children.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (popularly known as ACA or Obamacare), passed by Congress in 2010, is aimed at improving this situation. Some provisions of the act are widely supported: for example, young adults up to age 26 can be on their parents' insurance, preexisting conditions are covered in many cases, and caps on lifetime benefits have been lifted.

The heart of the ACA is an attempt to provide health insurance to almost all Americans: requiring those who can afford it to purchase health insurance and expanding Medicaid to cover those who cannot afford to buy insurance on their own. Both provisions have met with controversy.

For individuals who do not already have a health insurance plan that meets ACA requirements, states can provide insurance “exchanges” or “marketplaces” to assist them. For states such as Texas that opt not to have an exchange, the federal government's exchange provides the assistance. Major technical difficulties in the rollout of the federal exchange provoked a storm of criticism. However, the problems were fixed, and most people met the 2014 enrollment deadline.

The second major effort of the ACA was to expand the coverage of Medicaid, the joint federal-state program to provide medical care to the poor. In June 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld most of the Affordable Care Act in a suit brought by Texas and 25 other states (National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 132 S.Ct. 2566 [2012]). However, very importantly, the court held that the national government could not use the threat to cut existing Medicaid funds to coerce states into expanding Medicaid coverage. This allowed Texas and other states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion. (There is more discussion of Medicaid and the consequences of Texas not expanding its coverage in the Health and Mental Health Services section that follows.)

Since the Great Depression of the 1930s, state and national governments have gradually increased efforts to address the needs of the poor, the elderly, and those who cannot afford adequate medical care. In the 20th century, social welfare became an important part of the federal relationship (see Chapter 2, “Federalism and the Texas Constitution,” and Chapter 3, “Local Governments”). Over time, the national government has taken responsibility for relatively popular social welfare programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, and aid to the blind and disabled. The states, on the other hand, have responsibility for less popular welfare programs that have less effective lobbying behind them, such as Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). The federal government pays a significant part of the cost of state social welfare programs, but within federal guidelines the states administer them, make eligibility rules, and pay part of the tab.

Health and human services programs are at a disadvantage in Texas for two reasons. First, the state's political culture values individualism and self-reliance; thus, anything suggesting welfare is difficult to fund at more than a minimal level. In addition, the neediest Texans lack the organization and resources to compete with the special interest groups representing the business elite and the middle class. Thus, the Lone Star State provides assistance for millions of needy Texans, but at relatively low benefit levels. And many people are left out.

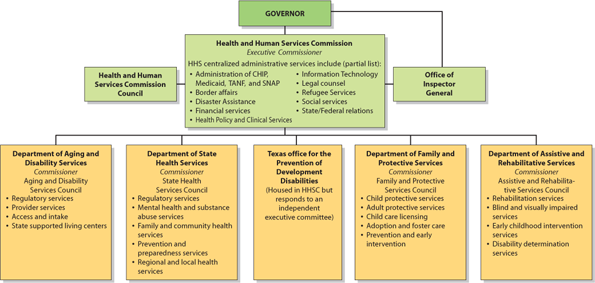

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) coordinates social service policy. Sweeping changes were launched in 2003 when the 78th Legislature consolidated functions of 12 social service agencies under the Executive commissioner of the Health and Human Services CommissionAppointed by the governor with Senate approval, the executive commissioner administers the HHSC, develops policies, makes rules, and appoints (with approval by the governor) commissioners to head the commission's four departments.. This legislation also began a process of privatizing service delivery, creating more administrative barriers to services, and slowing the growth of expenditures.

The executive commissioner of the HHSC is appointed by the governor for a two-year term and confirmed by the Senate. This official controls the agency directly and is not under the direction of a board; instead, executive commissioners tend to respond to the governor. The executive commissioner appoints, with the approval of the governor, commissioners to head the four departments of the HHSC: Department of State Health Services, Department of Aging and Disability Services, Department of Assistive and Rehabilitative Services, and Department of Family and Protective Services. See Figure 10.1 for the commission's organization chart and major tasks of the departments. The HHSC itself handles centralized administrative support services, develops policies, and makes rules for its agencies. In addition, the commission determines eligibility for TANF, SNAP, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid, and long-term care services. For the 2014–2015 biennium, the legislature authorized 58,000 employees for HHSC and its four departments.

Figure 10.1

The Consolidated Texas Health and Human Services System

Based on Texas Health and Human Services Commission, March 2014, http://www.hhsc.state.tx.us/about_hhsc/index.shtml.

Critical Thinking

Draw on this organization chart and the discussion of the commissioner in the text. What are the strengths and weaknesses of the executive commissioner in shaping Texas health and human services policy?

The legislature not only consolidated agencies under HHSC in 2003, but it also mandated a major change in the state's approach to social services—privatizationTransfer of government services or assets to the private sector. Commonly, assets are sold and services contracted out.. The belief is that private contractors can provide public services more cheaply and efficiently than can government. Under the legislative mandate, local social services offices and caseworkers were replaced with call centers operated by private contractors. Applicants for social services were encouraged to use the telephone and Internet to establish eligibility for most social services. A similar but much smaller privatized system had worked reasonably well in 2000. However, this new, larger system performed poorly. After 2003, the number of children covered by insurance dropped sharply, and eligible people faced long waits and lost paperwork. In response to these problems, the offshore private contractor was replaced, many state employees were rehired, and attempts were made to bring children back into the system. Yet in 2010, a federal official complained about Texas's “five-year slide” to last place among the states in the speed and accuracy of handling food stamp applications after privatization. Promised savings and better service have yet to appear.