the text book Practicing Texas Politics Texas Edition (16th Edition), Brown, et.al. for this assignment: 3,4,5,6,10,13.

Chapter13

Finance and Fiscal Policy

Chapter Introduction

13-1 Fiscal Policies

13-1a Taxing Policy

13-1b Budget Policy

13-1c Spending Policy

13-2 Revenue Sources

13-2a The Politics of Taxation

13-2b Revenue from Gambling

13-2c Other Nontax Revenues

13-2d The Public Debt

13-3 Budgeting and Fiscal Management

13-3a Budgeting Procedure

13-3b Budget Expenditures

13-3c Budget Execution

13-3d Purchasing

13-3e Facilities

13-3f Accounting

13-3g Auditing

13-4 Future Demands

13-4a Public Education

13-4b Public Higher Education

13-4c Public Assistance

13-4d Infrastructure Needs

13-5 Chapter Review

13-5aConclusion

13-5bChapter Summary

13-5cKey Terms

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy Chapter Introduction

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

Chapter Introduction

John Branch

Critical Thinking

Do you believe Texas should spend more or less money building and maintaining roads and bridges?

Learning Objectives

13.1 Assess the fairness of Texas's budgeting and taxing policies.

13.2 Describe the sources of Texas's state revenue.

13.3 Describe the procedure for developing and approving a state budget.

13.4 Evaluate the effectiveness of the state's financing of public services.

Bad roads and traffic jams aren't just an inconvenience; they cost money. A 2012 study by the Road Information Program placed that cost at $23.2 billion annually for all Texans. In Houston, wasted time, vehicle wear-and-tear, and extra fuel expenses totaled $1,900 per driver; in Dallas, $1,550; in San Antonio, $1,425; and in Austin, $1,235. Urban Texans spend as much as 37 additional hours in traffic each year because of road congestion. Outdated and unsafe roads and bridges account for 45 percent of the state's transportation infrastructure. The oil and gas boom that has fostered a strong economy in rural areas has also damaged or destroyed roads. The 1,500 new Texans who arrive each week add to traffic congestion. If funding for transportation needs continues at current levels, Texas A&M University's Texas Transportation Institute predicts that within 15 years urban Texans will spend approximately 75 hours per year waiting in traffic jams.

The third special session of the 83rd Legislature asked Texans to address the problem of inadequate funding for road repair and construction in the state. In November 2014, Texas voters amended the state's constitution to allow the diversion of some money intended for the Rainy Day Fund, the state's savings account, to the State Highway Fund. Although an improvement over previous funding levels, as the opening cartoon to this chapter indicates, this solution was only a Band-Aid approach to a much more substantial problem. Texans, who abhor high taxes, also demand good roads.

This chapter examines the balance between costs and services; it provides an overview of the Lone Star State's fiscal policies, budgeting processes, and most costly public policy areas. Taxing, public spending, and governmental policy priorities will continue to have significant impacts on 21st-century Texans.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-1 Fiscal Policies

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-1 Fiscal Policies

LO 13.1

Assess the fairness of Texas's budgeting and taxing policies.

During the 83rd legislative session in 2013, Texas's traditional low-tax approach to fiscal policyPublic policy that concerns taxing, government spending, public debt, and management of government money. (public policy that concerns taxes, government spending, public debt, and management of government money) faced key challenges. Students at all levels of publicly financed education, uninsured Texans, a decaying infrastructure, and water needs competed for state funding. A rapidly improving economy provided more funds to address these needs than had been available to the 82nd Legislature, but the session was not without conflict about the appropriate use of state revenue.

Tax revenue includes state sales taxes, as well as taxes on specific items such as cigarettes, motor vehicles, and gross receipts from businesses. Revenue sources other than taxes include oil and gas royalties, land sales, and federal grants-in-aid. The 82nd Legislature used a number of accounting maneuvers, such as delaying some mandatory payments beyond August 31, 2013 (the end of the biennial budget period), encouraging early payment of taxes to speed up revenue collection, and intentionally underfunding high-cost items such as Medicaid, to achieve a balanced budget. Spending was reduced for public education, higher education, health care programs, children's protective services, and all other areas of the budget except natural resources and economic development. Because of an improved economy, the 83rd Legislature was able to reverse many of these accounting devices, or “tricks.” Even with an improving economy, state agencies were directed in 2012 to reduce their upcoming budget requests to the 83rd Legislature by 10 percent. The 84th Legislature, meeting in 2015, faced no such limitations.

Texans remain committed to pay-as-you-go spending and low taxes, no matter the strength of the economy. The Lone Star State's fiscal policy has not deviated from its 19th-century origins. Today, the notion of a balanced budget, achieved by low tax rates and low to moderate government spending levels, continues to dominate state fiscal policy. Consequently, state government, its employees, and its taxpayers face the daily challenge of meeting higher demands for services with fewer resources.

The state's elected officials appear to adopt the view expressed by economist and Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman (1912–2006) that “the preservation of freedom requires limiting narrowly the role of government and placing primary reliance on private property, free markets, and voluntary arrangements.” Texas legislators and other state leaders have repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to reduce services, outsource governmental work to decrease the number of employees on the state's payroll, and maintain or lower tax rates as solutions to the state's fiscal problems.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-1a Taxing Policy

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-1a Taxing Policy

Texans have traditionally opposed mandatory assessments for public purposes, or taxesA mandatory assessment exacted by a government for a public purpose.. Residents have pressured their state government to maintain low taxes. When additional revenues have been needed, Texans have indicated in poll after poll their preference for regressive taxesA tax in which the effective tax rate falls as the tax base (such as individual income or corporate profits) increases., which favor the rich and fall most heavily on the poor (“the less you make, the more government takes”). Under such taxes, the burden decreases as personal income increases. Figure 13.1 illustrates the impact of regressive taxes on different levels of income. Under the current tax structure, the poorest 20 percent of Texans pay more than four times as much of their income in taxes as the wealthiest 20 percent.

Figure 13.1

Percent of Average Annual Family Income Paid in Local and State Taxes in Texas (FY2011).

Source: Chandra King Villanueva, “Who Pays Texas Taxes?” (Austin: Center for Public Policy Priorities, September 25, 2012). http://library.cppp.org/research.php?aid=1060.

Critical Thinking

What are the benefits and problems of a regressive tax system?

Texas lawmakers have developed one of the most regressive tax structures in the nation. A general sales tax and selective sales taxes have been especially popular. Progressive taxesA tax in which the effective tax rate increases as the tax base (such as individual income or corporate profits) increases. (taxes in which the impact increases as income rises—“the more you make, the more government takes”) have been unpopular. Texas officials and citizens so oppose state income taxes that the state constitution requires a popular referendum before an income tax can be levied. Newspaper columnists often observe that any elected official who proposes a state income tax commits political suicide.

To finance services, Texas government depends heavily on sales taxes, which rank among the highest in the nation. In addition, the Lone Star State has a dizzying array of other taxes. The Texas state comptroller's office collects more than 60 separate taxes, fees, and assessments on behalf of the state and local governments. Yet the sales tax remains the most important source of state revenue.

Many observers have criticized the regressive characteristics of Texas's tax system as being unfair. An additional concern is that the state primarily operates with a 19th-century land- and product-based tax system that is no longer appropriate to the knowledge- and service-based economy of the 21st century. Local governments rely heavily on real estate taxes for their revenue. More than half of the state's general revenue tax collections are sales and use taxes. Until 2006, business activities of service sectorBusinesses that provide services, such as finance, health care, food service, data processing, or consulting. employers (including those in trade, finance, and the professions) remained tax-free. In that year, however, the state altered the franchise tax law to require most Texas businesses to pay taxes calculated on their profit margins. This extension of the franchise tax subjected many service sector entities to taxation.

Texas is recognized as one of the “top performers” in the nation in the ability of its tax system to respond to shifts in the economy. Even so, a comparison of sales and use tax collections ($50 billion) and franchise tax collections ($9.3 billion) for the 2012–2013 biennium reflects the extent to which the Lone Star State persists in relying on sales tax revenue. Changes in Texas's economy, without corresponding changes in its tax system, are projected to continue to erode the tax base. Under the current structure, the part of the economy generating the greatest amount of revenue frequently pays the least amount in taxes.

In addition, the state charges special fees and assessments that are not called taxes but that represent money the state's residents pay to government. Texas legislators, reluctant to raise taxes, have often assessed these fees and surcharges. Is a feeA charge imposed by an agency upon those subject to its regulation., defined as a charge “imposed by an agency upon those subject to its regulation,” different from a tax? Some argue that these assessments represent an artful use of words, not a refusal to raise taxes, and that these charges meet the definition of a tax if the proceeds benefit the general public. For example, the state requires attorneys to pay an annual legal services fee to fund legal assistance for the poor. Attorneys who fail to pay this fee lose their right to practice law in the state. No matter the designation, this mandatory fee is money that an attorney must pay to finance government services for the general public.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-1b Budget Policy

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-1b Budget Policy

Hostility to public debt is demonstrated in constitutional and statutory provisions that are designed to force the state to operate with a pay-as-you-go balanced budgetA budget in which total revenues and expenditures are equal, producing no deficit.. The Texas Constitution prohibits the state from spending more than its anticipated revenue “[e]xcept in the case of emergency and imperative public necessity and with a four-fifths vote of the total membership of each House.” In addition, the cost of debt service limits the state's borrowing power. This cost cannot exceed 5 percent of the average balance of general revenue funds for the preceding three years.

To ensure a balanced budget, the comptroller of public accounts must submit to the legislature in advance of each regular session a sworn statement of cash on hand and revenue anticipated for the succeeding two years. Appropriation bills enacted at that particular session, and at any subsequent special session, are limited to not more than the amount certified, unless a four-fifths majority in both houses votes to ignore the comptroller's predictions or the legislature provides new revenue sources.

Texas accounts for the state's revenue and spending in several different budgets. The All Funds Budget includes all sources of revenue and all spending. It is the All Funds Budget that must be balanced each biennium. Additionally, reference is often made to the General Revenue Funds Budget. This budget includes the nondedicated portion of the General Revenue FundAn unrestricted state fund that is available for general appropriations. (money that can be appropriated for any legal purpose by the legislature) plus some of the funds used to finance public education (Available School Fund, the State Instructional Materials Fund, and the Foundation School Fund). Casual deficits (unplanned shortages) sometimes arise in the General Revenue Fund. Like a thermometer, this fund measures the state's fiscal health. If the fund shows a surplus (as occurred in FY2012–2013), fiscal health is good; if a deficit occurs (as occurred in FY 2010–2011), then fiscal health is poor. Less than one-half of the state's expenditures come from the General Revenue Fund; the remainder comes from other funds that state law designates for use for specific purposes.

The General Revenue–Dedicated Funds Budget includes more than 200 separate funds. Because of restrictions on use, these accounts are defined as dedicated fundsA restricted state fund that has been identified to fund a designated purpose. If the fund is consolidated within the general revenue fund, it usually must be spent for its intended purpose. Unappropriated amounts of dedicated funds, even those required to be used for a specific purpose, can be included in the calculations to balance the state budget.. In most cases, the funds can only be used for their designated purposes, though in some instances money can be diverted to the state's general fund. Even amounts that can only be spent for a designated purpose may be manipulated to satisfy the mandate for a balanced budget. The legislature can incorporate any unspent balances into its budget calculations. In the 82nd legislative session, for example, the legislature refused to appropriate more than $5 billion in General Revenue–Dedicated Funds in order to give the appearance of a balanced budget. State lawmakers justify these actions by noting that the high costs of programs such as Medicaid force them to freeze these balances. State Representative Sylvester Turner has characterized this practice somewhat differently, calling it “dishonest governing,” because it is an accounting trick that makes money appear available on paper that in fact is not available. The 83rd Legislature limited this practice and in 2014, Speaker Joe Straus announced that the 84th legislature would only use the State Highway fund to build and maintain transportation infrastructure.

The Federal Funds Budget includes all funding from the federal government. These amounts must be spent for their designated purposes. Likewise, the Other Funds Budget includes an additional 200-plus dedicated funds, each of which must be spent for its stated purpose, such as the Property Tax Relief Fund that must be used to fund public education.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-1c Spending Policy

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-1c Spending Policy

Learning Check 13.1

What are three characteristics of Texas's fiscal policy?

The state of Texas has one of the highest sales tax rates in the nation. It does not have a state income tax. Is Texas's tax structure an example of a regressive or a progressive tax system?

Historically, Texans have shown little enthusiasm for state spending. In addition to requiring a balanced budget, the Texas Constitution restricts increases in spending that exceed the rate of growth of the state's economy and limits welfare spending in any fiscal year to no more than 1 percent of total state expenditures. Consequently, public expenditures have remained low relative to those of other state governments. Texas has consistently ranked between 48th and 50th in state spending per capita. Although the state's voters have indicated moderate willingness to spend for highways, roads, and other public improvements, they have demonstrated much less support for welfare programs, recreational facilities, and similar social services.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-2 Revenue Sources

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-2 Revenue Sources

LO 13.2

Describe the sources of Texas's state revenue.

Funding for government services primarily comes from those who pay taxes. In addition, the state derives revenue from fees for licenses, sales of assets, investment income, gambling, borrowing, and federal grants. When revenue to the state declines, elected officials have only two choices: increase taxes or other sources of revenue or decrease services. In times of projected budget shortfalls, as occurred prior to the 2012-2013 biennium, the legislature's first response has been to decrease services. When revenue is plentiful, as was the situation at the end of that biennium, pressure builds to reduce taxes.

Point/Counterpoint

How Should the State Use a Budget Surplus?

THE ISSUE In December 2013, Comptroller of Public Accounts Susan Combs certified that the 2012–2013 state budget had $2.6 billion in unspent revenue at the end of the budget cycle. Some observers believed this excess represented a surplus that should be returned to the people through reduced sales taxes. Others argued that this amount was not a surplus but the result of the legislature's failing to meet the needs of Texas's population.

| Arguments For Refunding Tax Collections Above Budgeted Amounts | Arguments Against Refunding Tax Collections Above Budgeted Amounts |

|

|

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-2a The Politics of Taxation

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-2a The Politics of Taxation

Taxes are but one source of state revenue. According to generally accepted standards, each tax levied and the total tax structure should be just and equitable. Opinions vary widely about what kinds of taxes and what types of structures meet these standards. Conflicts are most apparent in the struggle to finance the state's public schools as elected officials strive to lower real estate taxes for the state's property owners and replace local funding with additional state-level taxes. Texas has a constitutional mandate to provide “an efficient system of public free schools,” and the state's courts have defined adequate funding as a key element of this requirement. Determining who should pay taxes to finance public education is a challenge.

In 2006, despite resistance from several large law firms, the 79th Legislature modified and expanded the business franchise tax. It also imposed an additional $1 tax on cigarettes, increased taxes on other tobacco products (except cigars), and required buyers to pay a tax on used cars at their presumptive value as determined by publications such as Kelley Blue Book. Since 2006, legislators have yielded to the demands of small business owners by reducing the number of businesses subject to the franchise tax and lowering the tax rate. Concomitantly, the legislature has increased taxes on tobacco products. These modifications reflect both the political strength of business owners and the ease of raising taxes on items that some people deem morally questionable.

Sales Taxes

By far the most important single source of state tax revenue in Texas is sales taxation. (See Figure 13.2 for the sources of state revenue.) Altogether, sales taxes accounted for more than 55 percent of state tax revenue and 26 percent of all revenue in fiscal years 2014–2015. These sales taxes function as a regressive tax, and the burden they impose on individual taxpayers varies with spending patterns and income levels.

Figure 13.2

Projected Sources of State Revenue, Fiscal Years 2014–2015.

Note: Amounts are in billions of dollars.

Source: Legislative Budget Board, Fiscal Size-up, 2014–15 Biennium (Austin: Legislative Budget Board, February 2014), 29, http://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/Publications/Fiscal_SizeUp/Fiscal_SizeUp.pdf.

Critical Thinking

What other sources of revenue do you believe are available to the State of Texas?

For more than 50 years, the state has levied and collected two kinds of sales taxes: a general sales taxTexas's largest source of tax revenue, applied at the rate of 6.25 percent to the sale price of tangible personal property and “the storage, use, or other consumption of tangible personal property purchased, leased, or rented.” and several selective sales taxes. First imposed in 1961, the limited sales, excise, and use tax (commonly referred to as the general sales tax) has become the foundation of the Texas tax system. The current (2014) statewide rate of 6.25 percent is one of the nation's highest (ranking as the 12th-highest rate among the 45 states that imposed a sales tax as of midyear 2014). Local governments have the option of levying additional sales taxes for a combined total of state and local taxes of 8.25 percent (see Chapter 3, “Local Governments”). The base of the tax is the sale price of “all tangible personal property” and “the storage, use, or other consumption of tangible personal property purchased, leased, or rented.” Among exempted tangible property are the following: receipts from water, telephone, and telegraph services; sales of goods otherwise taxed (for example, automobiles and motor fuels); food and food products (but not restaurant meals); medical supplies sold by prescription; nonprescription drugs; animals and supplies used in agricultural production; and sales by university and college clubs and organizations (as long as the group has no more than one fundraising activity per month).

Two other important items exempt from the general sales tax are goods sold via the Internet and most professional and business services. According to U.S. Supreme Court decisions, a state cannot require businesses with no facilities in the state to collect sales taxes on its behalf because the practice interferes with interstate commerce. Therefore, when a student buys a textbook from an online seller with no facilities in the state, no sales tax is collected. The book is, however, subject to a use tax, which requires the purchaser to file a form with the comptroller's office and pay taxes on items purchased out of state for use in Texas. Because the cost of enforcing such a provision on individual consumers is prohibitive, these transactions remain largely untaxed.

Some online merchants, such as kitchen retailer Williams-Sonoma, Inc., voluntarily collect sales taxes for the states. Other sellers argue that multiple rates and definitions of products subject to state sales taxes create a collection nightmare. Through the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board, 24 states, not including Texas, have signed Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreements that provide a uniform tax system to overcome these arguments. Approximately 2,000 online retailers voluntarily collect taxes for these states. To force all out-of-state retailers to participate, the U.S. Congress would be required to act because of its authority under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. To benefit from such a law, Texas would need to sign a Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. Based on estimated electronic sales in 2012, Texas lost more than $870 million in tax revenue.

One way to tax online retailers is through affiliate-nexus or “Amazon” laws (a reference to the online retailer Amazon). Under these laws, if an online retailer has a facility or employees in a state, the physical presence of the facility or people creates “a nexus” (or connection with the state). If any goods or services subject to sales tax are sold to the residents of that state, the seller must collect the tax and remit it to the state. Failure to do so subjects the seller to tax liability, interest, and penalties. In 2011, the 82nd Legislature clarified that the mere use of a Texas-based web hosting service was not sufficient to create a nexus with the State of Texas.

Having a distribution center in the state creates a nexus with the state, however. In 2012, State Comptroller Susan Combs settled a long-running dispute with Amazon regarding whether having a distribution center in the Dallas area was sufficient to force collection of sales tax on goods purchased by Texas customers. Under terms of the settlement agreement, the state forgave $269 million in unpaid sales taxes, interest, and penalties. In return, as of July 2012, Amazon began collecting sales taxes on customer purchases by Texans. In addition, the retailer agreed to invest more than $200 million in the state and create an additional 2,500 jobs. In 2013, the company completed construction of three new distribution centers in Texas, each at least 1 million square feet in size, and hired 1,000 workers to staff the centers. Although most of the jobs were hourly wage jobs, Amazon noted they paid higher than retail sales jobs and included health insurance. Additional controversy surrounded this settlement when some legal experts argued that the Texas Constitution prohibited the comptroller's forgiving unpaid taxes. Other attorneys and tax specialists countered that the comptroller had great latitude in resolving tax disputes.

Because the general sales tax primarily applies to tangible personal property, many services are untaxed. Sales taxes are charged for dry cleaning, football tickets, and parking; however, accountants, architects, and consultants provide their services tax-free. Because professional service providers and businesses represent some of the most powerful and well-organized interests in the Lone Star State, proposals that would require these groups to collect a sales tax have faced strong resistance. (See Chapter 7, “The Politics of Interest Groups.”) Although the comptroller estimates that eliminating sales tax exclusions for professional and other service providers would generate approximately $6.5 billion in additional annual revenue, even in difficult economic times, legislators made no effort to change the law.

Since 1931, when the legislature first imposed a sales tax on cigarettes, many items have been singled out for selective sales taxesA tax charged on specific products and services.. These items may be grouped into three categories: highway user taxes, sin taxesA selective sales tax on items such as cigarettes, other forms of tobacco, alcoholic beverages, and admission to sex-oriented businesses., and miscellaneous sales taxes. Highway user taxes include taxes on fuels for motor vehicles that use public roads and registration fees for the privilege of operating those vehicles. The principal sin taxes are those on cigarettes and other tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, and mixed drinks. One of the most contested taxes is the $5 fee added to admission fees to so-called gentlemen's clubs. The Texas Supreme Court rejected club owners' arguments that the law interfered with exotic dancers' free speech rights. In 2014, the Third Court of Appeals (Austin) found that the fee was a valid excise tax. The state collected approximately $17 million from this tax source between 2008 (when the law took effect) and 2013. Additional items subject to selective sales taxes include hotel and motel room rentals (also called a “bed tax”) and retail sales of boats and boat motors.

Business Taxes

As with sales taxes, Texas imposes both general and selective business taxes. A general business tax is assessed against a wide range of business operations. Selective business taxes are those levied on businesses engaged in specific or selected types of commercial activities.

Commercial enterprises operating in Texas have historically paid three general business taxes:

Sales taxes, because businesses are consumers

Franchise taxesA tax levied on the annual receipts of businesses that are organized to limit the personal liability of owners for the privilege of conducting business in the state., because many businesses operate in a form that attempts to limit personal liability of owners (that is, corporations, limited liability partnerships, and similar structures)

Unemployment compensation payroll taxes, because most businesses are also employers

The franchise tax, which has existed for almost 100 years, is imposed on businesses for the privilege of doing business in Texas. As a part of the restructuring of the state's school finance system, the legislature expanded the franchise tax to include all businesses operating in a format that limited the personal liability of owners. Sole proprietorships, general partnerships wholly owned by natural persons, passive investment entities (such as real estate investment trusts or REITs), and businesses that make $1 million or less in annual income or that owe less than $1,000 in franchise taxes are exempt. The tax is levied on a business's taxable margin, which is an amount equal to the least of (1) total revenue minus the cost of goods sold, (2) total revenue minus compensation and benefits paid to employees, (3) 70 percent of total revenue, or (4) total revenue minus $1 million.

Although proponents estimated that this tax would produce about $6 billion in state revenue each fiscal year, actual collections have been far less. In FY2013, franchise tax collections were $4.8 billion. For the two-year period covering the 2014–2015 biennium, the comptroller projected total collections of $9.2 billion (or approximately $4.6 billion per fiscal year). Thus, collections remain below the amounts predicted by the tax's original proponents. Several reasons have been cited for this shortfall, including a weak economy, the increase in the exemption from tax liability to include businesses earning less than $1 million, and a definition of “cost of goods sold” that includes deductions not available under federal law. The tax is highly unpopular among small business owners, who continue to seek its repeal.

All states have unemployment insurance systems supported by payroll taxesAn employer-paid tax levied against a portion of the wages and salaries of workers to provide funds for payment of unemployment insurance benefits in the event employees lose their jobs.. Paid by employers, these taxes are levied against a portion of the compensation paid to workers to insure employees against unemployment. Although collected by the state, the proceeds are deposited into the Unemployment Trust Fund in the U.S. Treasury. Benefits are distributed to qualified workers who lose their jobs.

The most significant of the state's selective business taxes are levied on the following:

Oil and gas production

Insurance company gross premiums

Public utilities gross receipts

Selective business taxes accounted for approximately 15 percent of the state's tax revenue in FY2008, when the economy was strong and oil and gas prices and production were high. When the economy floundered and oil and gas prices and production declined, these taxes amounted to only 10 percent of tax collections for the 2010–2011 biennium. By 2014–2015, primarily due to the recovery of the oil and gas industry, revenue from these sources rebounded to comprise 14 percent of the state's revenue.

One of the more important selective business taxes is the severance taxAn excise tax levied on a natural resource (such as oil or natural gas) when it is severed (removed) from the earth.. Texas has depended on severance taxes, which are levied on a natural resource, such as oil or natural gas, when it is removed from the earth. Texas severance taxes are based on the quantity of minerals produced or on the value of the resource when removed. The Texas crude oil production tax and the gas-gathering tax were designed with two objectives in mind: to raise substantial revenue and to regulate the amount of natural resources mined or otherwise recovered. Each of these taxes is highly volatile, reflecting dramatic increases and decreases as the price and demand for natural resources fluctuate. Current production in Texas relies heavily on hydraulic fracture stimulation (fracking) to recover oil and gas reserves. Controversies about the environmental impact of this recovery method on groundwater and on underground stability and water supply could reduce production and, therefore, decrease revenue to the Lone Star State.

Inheritance Tax

Because of changes to federal law, no inheritance or estate tax (frequently called a death tax) is collected on the estates of individuals dying on or after January 1, 2005. Some states have enacted laws imposing a tax on estates. It is unlikely that Texas will do so.

Tax Burden

The Tax Foundation places Texas well below the national average for the state tax burden imposed on its residents. In 2011, when state taxes alone were considered, the Lone Star State's tax burden ranked 45th among the 50 states. A candidate's “no new taxes” pledge remains an important consideration for many Texas voters and will likely result in state officials' continuing to choose fewer services over higher taxes to balance the state budget.

Tax Collection

As Texas's chief tax collector, the comptroller of public accounts collects more than 90 percent of state taxes, including those on motor fuel sales, oil and gas production, cigarette and tobacco sales, and franchises. Amounts assessed by the comptroller's office can be challenged through an administrative proceeding conducted by that office. Taxpayers dissatisfied with the results of their hearings can appeal the decision to a state district court.

Some taxpayers commit tax fraud by not paying their full tax liability. Electronic sales suppression devices and software, like zappers and phantomware, are used to report fewer sales than retailers actually have. These devices allow users to maintain an electronic set of books for tax purposes that erases some credit card and cash transactions from the register's memory. The devices and software are difficult to detect. Their use reduces the payment of any taxes based on a business's receipts, such as sales taxes, mixed drink taxes, and the gross margins or franchise tax. Although through May 2014 Texas had no reported cases of electronic tax fraud, one estimate suggests the state may lose as much as $1.6 billion per year from this type of fraud. More than 10 states have made some form of the use, installation, or sale of zappers and phantomware a crime. Texas is not one of them. Retailers and restaurateurs are not the only sources of tax fraud. Motor fuels are also subject to taxation and therefore tax fraud. An additional consequence of Governor Rick Perry's line-item veto of funding for the state's Public Integrity Unit was the elimination of the motor fuels fraud enforcement division. Enforcement of motor fuels tax fraud is now the responsibility of local district attorneys' offices.

Other agencies also collect taxes on behalf of the state. The Department of Motor Vehicles collects motor vehicle registration and certificate-of-title fees through county tax collectors' offices; the State Board of Insurance collects insurance taxes and fees; and the Department of Public Safety collects driver's license, motor vehicle inspection, and similar fees. The Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission collects state taxes on beer, wine, and other alcoholic beverages. Although taxes represent the largest source of state revenue, Texas has other funding means.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-2b Revenue from Gambling

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-2b Revenue from Gambling

The Lone Star State receives revenue from three types of gambling operations (called “gaming” by supporters): horse racing and dog racing, a state-managed lottery, and bingo. Owners of horse racing operations have lobbied politicians for legalization of slot machines at their tracks. In addition, the state's three Native American tribes (the Kickapoo nation near Eagle Pass, the Alabama-Coushatta in East Texas, and the Tigua near El Paso) continue to argue for the right to operate Las Vegas–style casinos. Opposition from both social conservatives and many Democrats remains strong. This opposition is not restricted to casino gambling. In 2013, the Texas House of Representatives voted to abolish the Texas Lottery Commission. When proponents argued the legislature would have to replace $2.2 billion in funding for public schools if the lottery were eliminated, some opponents changed their votes. As a result, the Texas Lottery Commission will continue in existence through 2025, although the same bill created the Legislative Committee to Review the Texas Lottery and Texas Lottery Commission. Among the committee's responsibilities is investigating the viability of phasing out the lottery.

Racing

Pari-mutuel wagers on horse races and dog races are taxed. This levy has never brought Texas significant revenue. Proceeds from uncashed mutuel tickets, minus the cost of drug testing the animals at the racing facility, revert to the state. In most years, the Racing Commission collects far less revenue than its operating expenses. Texas has four types of horse racing permits, ranging from Class 1 (with no limit on the number of race days per year) to Class 4 (limited to five race days annually). As of 2014, the Lone Star State had 10 permitted horse racing tracks (four that were active and six that were inactive) and three dog tracks providing live and simulcast racing events on which people could wager legal bets.

Lottery

Texas operates one of 43 state-run lotteries as well as the multistate lotteries, Mega Millions and Powerball. Through April 2014, Texans had won more than $43 billion in prizes. Chances of winning the state lottery jackpot, however, are 1 in 26 million. No Texan has won a Mega Millions jackpot, and only one has won a Powerball jackpot since the state began participating in these lotteries in 2003. Chances of winning Mega Millions are 1 in 176 million. Powerball odds are even more daunting: 1 in 195 million.

The Texas Lottery Commission administers the state's lottery. The five-member commission is appointed by the governor for six-year terms. Because the commission also oversees bingo operations, one member must have experience in the bingo industry. Among the commission's functions are determining the amounts of prizes, overseeing the printing of tickets, advertising ticket sales, and awarding prizes. The commission maintains a Twitter account through which the public receives regular updates on winning lottery numbers and upcoming jackpot amounts.

Almost all profits from the lottery are dedicated to public education spending. In 2013, more than $1.1 billion went to the Texas Foundation School Fund. This amount constituted a small portion of the state's budgeted expenditure of more than $26 billion on public education in that same year. Proceeds from a Veteran's Cash scratch-off game benefit the Veterans' Assistance Fund, which received $5.2 million from ticket sales in 2013. Unclaimed prizes from the Texas lottery revert to the state 180 days after a drawing. These funds are transferred to hospitals across the state to provide partial reimbursement for unfunded indigent medical care. Five percent of ticket sale revenue is used to pay commissions to retailers who sell the tickets.

Bingo

State law allows bingo operations to benefit charities (for example, churches, veterans' organizations, and service clubs). The 5 percent tax on bingo prizes is divided 50–50 between the state and local governments. State revenue from bingo taxes remains low. Local charities benefit somewhat from the portion of the proceeds that is distributed to them. In 2011, the last year for which information is available, these donations were approximately $29 million. In that same year, the Texas Lottery Commission reported gross receipts from charitable bingo games of $705 million, exceeding all previous years. This increase in gross revenue was not reflected in donations, however. The amount was used to increase winners' prizes. Investigations in the Dallas area identified several bingo operations that paid little, if any, of their proceeds to charitable organizations. One bingo hall collected $1 million in gross receipts from which the charity received $1,600. The Legislative Committee to Review the Texas Lottery and Texas Lottery Commission was required to evaluate the effect of mandatory charitable distributions on charitable bingo.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-2c Other Nontax Revenues

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-2c Other Nontax Revenues

Less than 50 percent of all Texas state revenue comes from taxes and gambling operations; therefore, other nontax revenues are important sources of funds. The largest portion of these revenues comes from federal grants. Figure 13.3 reflects the growth of this funding source over the last seven biennia. State business operations (such as sales of goods by one government agency to another government agency) and borrowing also are significant sources of revenue. In addition, the state has billions of dollars invested in interest-bearing accounts and securities.

Figure 13.3

Federal Grants to Texas by Biennium (FY2002–2015) (in billions).

Source: Developed from information available from State Comptroller, “Texas Net Revenue by Source, 1973–2010” and “Texas Net Revenue by Source, 2011,” and Legislative Budget Board, Fiscal Size-up: 2014–2015 Biennium.

Critical Thinking

Is Texas too reliant on federal grants to balance its budget?

Federal Grants-in-Aid

Gifts of money, goods, or services from one government to another are defined as grants-in-aidMoney, goods, or services given by one government to another (for example, federal grants-in-aid to states for financing public assistance programs).. Federal grants-in-aid contribute more revenue to Texas than any single tax levied by the state. More than 95 percent of federal funds are directed to three programs: health and human services, business and economic development (especially highway construction), and education. For the 2012–2013 biennium, federal funds, including grants, accounted for approximately $74 billion in revenue. In the 2010–2011 biennium, during the Great Recession, the state relied on an additional $12 billion in one-time federal grants to balance the state budget.

State participation in federal grant programs is voluntary. Participating states must (1) contribute a portion of program costs (varying from as little as 10 percent to as much as 90 percent) and (2) meet performance specifications established by federal mandate. Funds are usually allocated to states on the basis of a formula. These formulae usually include (1) lump sums (made up of identical amounts to all states receiving funds) and (2) uniform sums (based on items that vary from state to state, such as population, area, highway mileage, need and fiscal ability, cost of service, administrative discretion, and special state needs).

Land Revenues

Texas state government receives nontax revenue from public land sales, rentals, and royalties. Sales of land, sand, shell, and gravel, combined with rentals on grazing lands and prospecting permits, accounted for approximately 1.1 percent of the state's budget in the 2014–2015 biennium. A substantial portion of revenue from state lands is received from oil and natural gas leases and from royalties derived from mineral production. Volatility of oil and natural gas prices causes wide fluctuations in the amount the state receives from these mineral leases. Projected collections for 2014–2015 represented a $300 million decline from 2012–2013 land revenues. A new source of revenue is lease payments from commercial offshore wind turbines. The General Land Office, the agency responsible for managing the more than 20 million acres of land surface and mineral rights that the state owns, also leases offshore sites for wind power. As of 2013, the state had 52,000 acres in Texas's tidelands under lease for wind energy production. Like most other lease payments and royalties derived from the state's public lands, rental amounts are deposited in the Permanent School Fund for the benefit of public schools.

The Tobacco Suit Windfall

Early in 1998, the American tobacco industry settled a lawsuit filed by the State of Texas. During a period of 25 years, cigarette makers will pay the Lone Star State $18 billion in damages for public health costs incurred by the state as a result of residents' tobacco-related illnesses. These funds support a variety of health care programs, including the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid, tobacco education projects, and endowments for health-related institutions of higher education. Payments averaged approximately $500 million per year through 2011. Because of increases in taxes that have reduced consumption in Texas and other states, revenue from the sale of tobacco products has declined in recent years. As a result, the comptroller predicted that settlement payments from the tobacco lawsuit would decline by $45 million in the 2014–2015 biennium. An additional $2.3 billion is administered as a trust by the state comptroller to reimburse local governments (cities, counties, and hospital districts) for unreimbursed health care costs.

Miscellaneous Sources

Fees, permits, and income from investments are major miscellaneous nontax sources of revenue. Fee sources include those for motor vehicle inspections, college tuition, student services, state hospital care, and certificates of title for motor vehicles. The most significant sources of revenue from permits are those for trucks and automobiles; the sale of liquor, wine, and beer; and cigarette tax stamps. During the 2014–2015 biennium, income from these sources increased over the previous biennium, providing further evidence of Texas's return to economic health.

At any given moment, Texas has billions of dollars on hand, invested in securities or on deposit in interest-bearing accounts. Trust funds constitute the bulk of the money invested by the state (for example, the Texas Teacher Retirement Fund, the State Employee Retirement Fund, the Permanent School Fund, and the Permanent University Fund). Investment returns closely track fluctuations in the stock market. Chaos in the financial markets that began in September 2008 had a direct effect on this revenue source. Interest and investment income for the 2014–2015 biennium was less than half of amounts collected during fiscal years 2008 and 2009.

The Texas state comptroller is responsible for overseeing the investment of most of the state's surplus funds. Restrictive money management laws limit investments to interest-bearing negotiable order withdrawal (NOW) accounts, U.S. Treasury bills (promissory notes in denominations of $1,000 to $1 million), and repurchase agreements (arrangements that allow the state to buy back assets such as state bonds) from banks. Interest and investment income was expected to provide 1 percent of state revenue in 2014–2015.

The University of Texas Investment Management Company (UTIMCO) invests the Permanent University Fund and other endowments for the University of Texas and Texas A&M University systems. Its investment authority extends to participating in venture capital partnerships that fund new businesses. Board members for UTIMCO include the chancellor and three regents from the University of Texas System, two individuals selected by the Board of Regents of the Texas A&M University System, and three outside investment professionals. This nonprofit corporation was the first such investment company in the nation affiliated with a public university.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-2d The Public Debt

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-2d The Public Debt

When expenditures exceed income, governments finance shortfalls through public borrowing. Such deficit financing is essential to meet short- and long-term crises and to pay for major projects involving large amounts of money. Most state constitutions, including the Texas Constitution, severely limit the authority of state governments to incur indebtedness.

Bonded Indebtedness

For more than 70 years, Texans have sought, through constitutional provisions and public pressure, to force the state to operate on a pay-as-you-go basis. Despite those efforts, the state is allowed to borrow money by issuing general obligation bondsAmount borrowed by the state that is repaid from the General Revenue Fund. (borrowed amounts repaid from the General Revenue Fund) and revenue bondsAmount borrowed by the state that is repaid from a specific revenue source. (borrowed amounts repaid from a specific revenue source, such as college student loan bonds repaid by students who received the funds). Commercial paper (unsecured short-term business loans) and promissory notes also cover the state's cash flow shortages. Whereas general obligation bonds and commercial paper borrowings require voter approval, other forms of borrowing do not. Outstanding bonded debt must be repaid from the General Revenue Fund. This debt, including bonds issued by the state's universities, was approximately $37.9 billion as of FY2013, of which $22.5 billion was issued as revenue bonds and the remainder as general obligation bonds.

Bond Review

Specific projects to be financed with bond money require legislative approval. Bond issues also must be approved by the Texas Bond Review Board. The four members of this board are the governor, lieutenant governor, Speaker of the House, and comptroller of public accounts. The board approves all borrowings by the state or its public universities with a term in excess of five years or an amount in excess of $250,000.

Economic Stabilization Fund

The state's Economic Stabilization Fund (popularly called the Rainy Day FundA fund used like a savings account for stabilizing state finance and helping the state meet economic emergencies when revenue is insufficient to cover state-supported programs.) operates like a savings account. It is intended for use when the state faces an economic crisis and is used primarily to prevent or eliminate temporary cash deficiencies in the General Revenue Fund. The Rainy Day Fund is financed with one-half of any excess money remaining in the General Revenue Fund at the end of a biennium and with oil and natural gas taxes that exceed 1987 collections (approximately $1.3 billion in that year). This fund has provided temporary support for public education, Medicaid, and the criminal justice system, as well as financing for the Texas Enterprise Fund (TEF), which is designed to attract new businesses to the state, and the Emerging Technology Fund, intended for use by companies engaged in work with medical or scientific technologies. A 2014 audit of TEF disclosed a number of improprieties including noncompetitive funding of grants and unpunished defaults in companies' obligations to create new jobs.

Learning Check 13.2

What is the largest source of tax revenue for the state of Texas?

What is the stated purpose of the Rainy Day Fund?

The weakness or strength of the economy is revealed in collections by the Rainy Day Fund. During the two biennia in 2008–2011, the state experienced the effects of the Great Recession and had no budget surpluses to transfer into the fund. By 2013, all sectors of Texas's economy were doing well, especially oil and gas. As a result, Texas had a $2.6 billion budget surplus for the 2013–2014 biennium, one-half of which ($1.3 billion) was deposited in the Rainy Day Fund. The state collected an additional $2.76 billion in excess oil and gas taxes. Because of the constitutional amendment approved in November 2014 that required the use of one-half of this amount for transportation infrastructure needs, the Rainy Day Fund received $1.38 billion. When the 84th Legislature convened in January 2015, the economic stabilization fund totaled $8.1 billion, well below the maximum amount of $14.5 billion that could be held in the fund. Deposits to the Rainy Day Fund are limited to an amount equal to 10 percent of revenue collections from the previous biennium. Should the maximum be reached, the state suspends transfers and deposits earned interest in the General Revenue Fund. The 2014 drop in oil prices made this option unlikely.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3 Budgeting and Fiscal Management

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3 Budgeting and Fiscal Management

LO 13.3

Describe the procedure for developing and approving a state budget.

The state's fiscal management process begins with a statewide vision for Texas government and ends with an audit. Other phases of this four-year process include development of agency strategic plans, legislative approval of an appropriations bill, and implementation of the budget. Each activity is important if the state is to derive maximum benefit from the billions of dollars it handles each year.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3a Budgeting Procedure

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3a Budgeting Procedure

A plan of financial operation is usually referred to as a budgetA plan of financial operation indicating how much revenue a government expects to collect during a period (usually one or two fiscal years) and how much spending is authorized for agencies and programs.. In modern state government, budgets serve a variety of functions, each important in its own right. A budget outlines a plan for spending that shows a government's financial condition at the close of one budget period and the anticipated condition at the end of the next budget cycle. Based on estimated revenue, the budget also makes spending recommendations for the coming budget period. In Texas, the budget period covers two fiscal years. Each fiscal year begins on September 1 and ends on August 31 of the following year. The fiscal year is identified by the initials FY (for “fiscal year”) preceding the number for the ending year. For example, FY2015 began on September 1, 2014, and ended on August 31, 2015.

Texas is one of only four states that have biennial (every two years) legislative sessions and budget periods. Many political observers argue that today's economy fluctuates too rapidly for this system to be efficient. Voters, however, have consistently rejected proposed constitutional amendments requiring annual state appropriations.

Legislative Budget Board

By statute, the Legislative Budget Board (LBB)A 10-member body cochaired by the lieutenant governor and the Speaker of the House. This board and its staff prepare a biennial current services budget. In addition, they assist with the preparation of a general appropriation bill at the beginning of a regular legislative session. If requested, staff members prepare fiscal notes that assess the economic impact of a proposed bill or resolution. is a 10-member joint body of the Texas House of Representatives and the Texas Senate. Its membership includes as joint chairs the lieutenant governor and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. Assisted by its director and staff, the LBB prepares a biennial (two fiscal years) current services–based budget. This type of budget projects the cost of meeting anticipated service needs of Texans over the next biennium. The comptroller of public accounts furnishes the board with an estimate of the growth of the Texas economy covering the period from the current biennium to the next biennium. Legislative appropriations from tax revenue not dedicated by the Texas Constitution cannot exceed that rate of growth. Based on the comptroller's projections, the LBB capped the growth of appropriations from undedicated revenue at slightly less than 11 percent for the 2014–2015 biennium.

The board's staff also helps draft the general appropriation bill for introduction at each regular session of the legislature. If requested by a legislative committee chair, staff personnel prepare fiscal notes that estimate the potential economic impact of a bill or resolution. Employees of the LBB also assist agencies in developing performance evaluation measures and audits, and they conduct performance reviews to determine how effectively and efficiently agencies are functioning.

Governor's Office of Budget, Planning and Policy

Headed by an executive budget officer who works under the supervision of the governor, the Governor's Office of Budget, Planning and Policy (GOBPP) is required by statute to prepare and present a biennial budget to the legislature. Traditionally, the governor's plan is policy based. It presents objectives to be attained and a plan for achieving them. As a result of this dual arrangement, two budgets, one legislative in origin and the other executive, should be prepared every two years. Governor Perry submitted separate budgets for each of the first four biennia of his administration (2001–2007). For the last three biennia (2009–2015) of his governorship, however, Perry proposed budgets that were the same or varied only minimally from those prepared by the LBB.

Budget Preparation

Compilation of each budget begins with development of a mission statement for Texas by the governor in cooperation with the LBB. That vision for the 2016–2017 biennium, as for the preceding biennium, urged agency personnel to “continue to critically examine the role of state government by identifying core programs and activities necessary for the long-term economic health of our state.” Every even-numbered year, each operating agency requesting appropriated funds must submit a five-year strategic operating plan to the GOBPP and to the LBB. These plans must incorporate the state's mission and philosophy of government, along with quantifiable and measurable performance goals. Texas uses performance-based budgeting; thus, strategic plans provide a way for legislators to determine how well an agency is meeting its objectives. For example, in 2012, the Office of the Comptroller submitted a strategic plan in which the agency set a goal of improving taxpayers' voluntary compliance with the Tax Code. One performance measure was to assure that each tax collector had an average of 269 delinquent account closures annually (presumably, if taxpayers believe a high likelihood exists of their being caught for noncompliance, they are more likely to comply with tax laws).

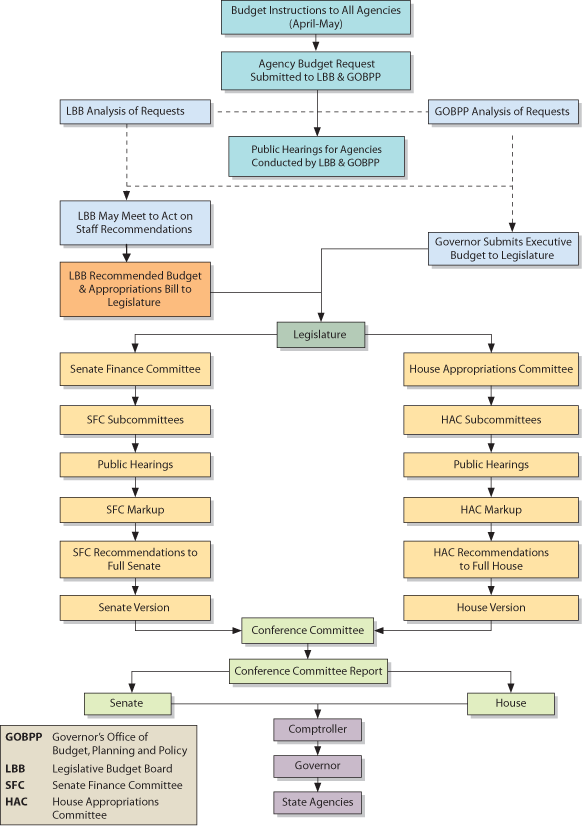

Legislative Appropriation Request forms and instructions are prepared by the LBB. (See Figure 13.4 for a diagram of the budgeting process.) These materials are sent to each spending agency in late spring in every even-numbered year. For several months thereafter, representatives of the budgeting agencies work to complete their proposed departmental requests. An agency's appropriations request must be organized according to strategies that the agency intends to use in implementing its strategic plan over the next two years. Each strategy, in turn, must be listed in order of priority and tied to a single statewide functional goal.

Figure 13.4

Texas Biennial Budget Cycle.

Source: Senate Research Center, Budget 101: A Guide to the Budget Process in Texas (Austin: Senate Research Center, January 2013), p. 5, http://www.senate.state.tx.us/SRC/pdf/Budget101WebsiteSecured_2013.pdf.

Critical Thinking

Is Texas's budgeting process efficient?

By early fall in even-numbered years, state agencies submit their departmental estimates to the LBB and GOBPP. These budgeting agencies then carefully analyze all requests and hold hearings with representatives of spending departments to clarify details and glean any additional information needed. At the close of the hearings, budget agencies traditionally compile their estimates of expenditures into two separately proposed budgets, which are then delivered to the legislature.

Thus, during each regular session, legislators normally face two sets of recommendations for all state expenditures for the succeeding biennium. Since the inception of the dual budgeting systemThe compilation of separate budgets by the legislative branch and the executive branch., the legislature has shown a marked preference for the recommendations of its own budget-making agency, the LBB, over those of the GOBPP and the governor. Therefore, the governor's proposed budget frequently varies little, if at all, from the LBB's proposed budget.

By custom, the legislative chambers rotate responsibility for introducing the state budget between the chair of the Senate Finance Committee and the chair of the House Appropriations Committee. At the beginning of each legislative session, the comptroller provides the legislature with a biennial revenue estimate. The legislature can only spend in excess of this amount upon the approval of four-fifths of each chamber. In subsequent months, the legislature debates issues surrounding the budget, and members of the Senate Finance Committee and the House Appropriations Committee conduct hearings with state agencies, including public universities and colleges, regarding their budget requests. During the hearings, agency officials are called upon to defend their budget requests and the previous performance of their agencies or departments.

The committees then make changes to the appropriations bill (a practice known as “markup”) and submit the bill to each chamber for a vote. (For a discussion of how a bill becomes a law, see Chapter 8, “The Legislature.”) After both chambers approve the appropriations bill, the comptroller must certify that the State of Texas will collect sufficient revenue to cover the budgetary appropriations. Only upon certification is the governor authorized to sign the budget. The governor has the power to veto any spending provision in the budget through the line-item veto (that is, rejecting only a particular expenditure in the budget). Governor Perry's exercise of his line-item veto authority in 2013 was the subject of a Travis County grand jury investigation and Perry’s subsequent indictment for “abuse of power.” The governor demanded the resignation of Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lembaugh in exchange for an appropriation to the Public Integrity Unit directed by the District Attorney's office. (See Chapter 9, “The Executive Branch.”) When she did not comply, he vetoed funding.

Budget approval does not guarantee that funds will remain available to an agency, including public colleges and universities. For example, in January 2010, Governor Perry, Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, and House Speaker Joe Straus directed all state-funded entities to identify ways to reduce by 5 percent the portion of their FY2010 and FY2011 budgets funded by the state. Approximately $1.2 billion in reductions were required (cuts amounting to 1.4 percent of state funding).

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3b Budget Expenditures

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3b Budget Expenditures

Analysts of a government's fiscal policy classify expenditures in two ways: functional and objective. The services being purchased by government represent the state's functional budget. An objective analysis is used to report how money was spent for items such as employees’ salaries. Figure 13.5 illustrates Texas's proposed functional expenditures for fiscal years 2014 and 2015. For more than five decades, functional expenditures have centered on three principal functions: public education, human services, and highway construction and maintenance (included under business and economic development). The 2014–2015 biennial budget reflected the same priorities.

Figure 13.5

All Texas State Funds Appropriations by Function for Fiscal Years 2014–2015 (in millions).

Source: House Research Organization, Texas Budget Highlights: Fiscal 2014–15, State Finance Report No. 83-4 (Austin: House Research Organization, May 2, 2014), 3, http://www.hro.house.state.tx.us/pdf/focus/highlights83.pdf

Critical Thinking

On what services do you believe the state should spend more or less money?

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3c Budget Execution

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3c Budget Execution

In most state governments, the governor's office or an executive agency responsible to the governor supervises budget executionThe process whereby the governor and the Legislative Budget Board oversee (and, in some instances, modify) implementation of the spending plan authorized by the Texas legislature. (the process by which a central authority in government oversees implementation of a spending plan approved by the legislative body). The governor of Texas and the Legislative Budget Board have limited power to prevent an agency from spending part of its appropriations, to transfer money from one agency to another, or to change the purpose for which an appropriation was made. Any modification the governor proposes must be made public, after which the LBB may ratify it, reject it, or recommend changes. If the board recommends changes in the governor's proposals, the chief executive may accept or reject the board's suggestions.

The proper functioning of Texas's budget execution system requires a coordinated effort among the state's political leadership. The board met twice in 2012, in August and November, to receive updates on the state's economic condition. The board met in August 2014 for a similar update through FY2014.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3d Purchasing

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3d Purchasing

Agencies of state government must make purchases through or under the supervision of the Texas Procurement and Support Services (TPASS), a division of the Office of the Comptroller of Public Accounts. Depending on the cost of an item, agency personnel may be required to obtain competitive bids. This division places greater emphasis on serving state agencies for which it purchases goods than on controlling what they purchase. It also provides agencies with administrative support services, such as mail distribution and management of vehicle fleets. In addition, the division negotiates contracts with airlines, rental car agencies, and hotels to obtain lower prices for personnel traveling on state business. These services are also available to participating local governments. The seven-member Council on Competitive Government, chaired by the governor, is required to determine exactly what kinds of services each agency currently provides that might be supplied at less cost by private industry or another state agency.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3e Facilities

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3e Facilities

A seven-member appointed board oversees the Texas Facilities Commission. This agency provides property management services for state facilities, including the Texas State Cemetery. In addition, agency personnel, in collaboration with the Longhorn Foundation, manage football tailgating on state property in Austin. The agency begins taking online reservations in June of each year.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3f Accounting

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3f Accounting

The comptroller of public accounts oversees the management of the state's money. Texas law holds this elected official responsible for maintaining a double-entry system, in which a debit account and a credit account are maintained for each transaction. Other statutes narrow the comptroller's discretion by creating numerous dedicated funds or accounts that essentially designate revenues to be used for financing identified activities. Because this money is usually earmarked for special purposes, it is not subject to appropriation for any other use by the legislature.

Major accounting tasks of the comptroller's office include preparing warrants (checks) used to pay state obligations, acknowledging receipts from various state revenue sources, and recording information concerning receipts and expenditures in ledgers and other account books. Contrary to usual business practice, state accounts are set up on a cash basis rather than an accrual basis. In cash accounting, expenditures are entered when the money is actually paid rather than when the obligation is incurred. In times of fiscal crisis, the practice of creating obligations in one fiscal year and paying them in the next allows a budget to appear balanced. Unfortunately, it complicates the task of fiscal planning by failing to reflect an accurate picture of current finances at any given moment. The comptroller issues monthly and annual reports that include general statements of revenues and expenditures. These reports allocate spending based on the object of expenditures that are the goods, supplies, and services used to provide government programs. Salaries, wages, and employment benefits for state employees consistently lead all objective expenditures.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-3g Auditing

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-3g Auditing

State accounts are audited (examined) under direct supervision of the state auditor. This official is appointed by and serves at the will of the Legislative Audit Committee, a six-member committee comprised of the lieutenant governor; the Speaker of the House of Representatives; one appointed member from the Senate; and the chairs of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Appropriations Committee, and the House Ways and Means Committee. The auditor may be removed by the committee at any time without the privilege of a hearing.

Learning Check 13.3

What is a fiscal year?

Texas has a dual budgeting system. What does this mean?

With the assistance of approximately 200 staff members, the auditor provides random checks of financial records and transactions after expenditures. Auditing involves reviewing the records and accounts of disbursing officers and custodians of all state funds to assure compliance with the law. Another important duty of the auditor is to examine the activities of each state agency to evaluate the quality of its services, determine whether duplication of effort exists, and recommend changes. The State Auditor's Office is also responsible for reviewing performance measures that agencies include in their strategic plans to ensure that accurate reporting procedures are in place. The agency conducts audits in order of priority by reviewing activities most subject to potential or perceived abuse first. Its stated mission is to provide elected officials with information to improve accountability in state government.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-4 Future Demands

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-4 Future Demands

LO 13.4

Evaluate the effectiveness of the state's financing of public services.

Elected officials have worked to keep taxing levels low. As a result, Texas has also kept its per capita spending levels among the lowest in the nation. Some observers believe that this limited funding is merely deferring problems in the areas of education, social services, and the state's infrastructure for years to come. Problems that continue to compete for public money include increasing enrollment in our public schools, colleges, and universities; additional social service needs; and an outdated infrastructure.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 13: Finance and Fiscal Policy: 13-4a Public Education

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

13-4a Public Education

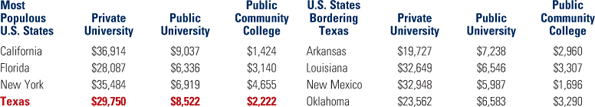

The state, together with local school districts, is responsible for providing a basic education for all Texas school-age children. State and local spending on public education remains below the national average ($8,275 per student in Texas versus $10,938 nationally for 2012–2013). Public education accounted for 28 percent of the state's projected expenditures (approximately $28 billion per year) for the 2014–2015 biennium. That amount of state funding reportedly accounted for less than 50 percent of the actual cost of public education. Legislators had, however, restored some of the 82nd Legislature's historic $5.4 billion funding reduction from 2011. The cuts had been required to balance the state's budget for the 2012–2013 biennium. All remaining costs for public education must be covered with local taxes and federal grants.

This hybrid arrangement may explain some of the difficulties in operating and financing Texas's schools. Is public education a national issue deserving of federal funding, attention, and standards, similar to the interstate highway system, in which the federal government pays for roads that connect all parts of the nation? Or should education be a state function, similar to the state's role in building and maintaining state highways so that all Texans are entitled to drive on the same quality of paved roads? Or is public education a local responsibility, more akin to city streets so that towns with more money have better-quality streets than their poorer neighbors? Although education appears to integrate all three levels of government—national, state, and local—into one system, confusion and conflict surround the fiscal responsibility and role of each in the state's educational system. When the Texas legislature created the Property Tax Relief Fund in 2006, state leaders predicted that by 2008 state funding would provide at least 50 percent of public school funding. Through 2015, however, the state's share of funding for public schools remained at less than 50 percent.

Sources of Public School Funding

Texas state government has struggled with financing public education for more than 40 years.Table 13.1 provides a history of relevant court decisions, state constitutional provisions, and legislative responses that have established funding sources and shaped the ways in which those sources are administered. In promoting public education, Texas state government has usually confined its activity to establishing minimum standards and providing basic levels of financial support. School districts and state government share the cost of three elements—salaries, transportation, and operating expenses. Local funding of school systems relies primarily on the market value of taxable real estate within each school district, because local schools raise their share primarily through property taxes. Average daily attendance of pupils in the district, types of students (for example, elementary, secondary, or disabled), and local economic conditions determine the state's share.

Table 13.1

History of Texas Public School Finance in the Courts

| Case | Year | Question | Decision | Legislative Response |

| Rodriguez v. San Antonio (U.S. Supreme Court) | 1971 | Does Texas's school funding system violate the Equal Protection Clause? | No, because education is not a federally protected right. | None |