the text book Practicing Texas Politics Texas Edition (16th Edition), Brown, et.al. for this assignment: 3,4,5,6,10,13.

Chapter3

Local Governments

Chapter Introduction

3-1 Local Politics in Context

3-1a Local Governments and Federalism

3-1b Grassroots Challenges

3-2 Municipal Governments

3-2a Legal Status of Municipalities

3-2b Forms of Municipal Government

3-3 Municipal Politics

3-3a Rules Make a Difference

3-3b Socioeconomic and Demographic Changes

3-3c Municipal Services

3-3d Municipal Government Revenue

3-3e Generating Revenue for Economic Development

3-4 Counties

3-4a Structure and Operation

3-4b County Finance

3-4c County Government Reform

3-4d Border Counties

3-5 Special Districts

3-5a Public School Districts

3-5b Junior or Community College Districts

3-5c Noneducation Special Districts

3-6 Metropolitan Areas

3-6a Councils of Governments

3-6b Municipal Annexation

3-7 Chapter Review

3-7aConclusion

3-7bChapter Summary

3-7cKey Terms

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments Chapter Introduction

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

Chapter Introduction

Nick Anderson Editorial Cartoon used with the permission of Nick Anderson, the Washington Post Writers Group and the Cartoonist Group. All rights reserved.

Critical Thinking

How do different levels of local government work together and at times also work against each other?

Learning Objectives

3.1 Explain the relationships that exist between a local government and all other governments, including local, state, and national governments.

3.2 Describe the forms of municipal government organization.

3.3 Identify the rules and social issues that shape local government outcomes.

3.4 Analyze the structure and responsibilities of counties.

3.5 Explain the functions of special districts and their importance to the greater community.

3.6 Discuss the ways that local governments deal with metropolitan-wide and regional issues.

When most Texans think about government, they think about the national or state government, but not about the many local governments. Yet of all three levels of government, local government has the greatest impact on citizens' daily lives. Most people drive every day on city streets or county roads, drink water provided by the city or a special district, attend schools run by the local school district, play in a city or county park, eat in restaurants inspected by city health officials, and live in houses or apartments that required city permits and inspections to build. Many citizens' contacts with local governments are positive. Potholes are filled, trash is picked up regularly, baseball fields are groomed for games—but other experiences are less positive. Streets and freeways are increasingly congested, many schools are overcrowded, and the property taxes to support them seem high. The cartoon that begins this chapter illustrates the complexity of local politics. Because of limited resources, local governments must choose from among competing interests, including sports arenas.

Local governments in Texas, from cities to counties to special districts, have a problem with debt. Harris County, the most populated county in Texas, with a population of more than 4 million residents, has been deemed the state's most indebted county. Harris County has more debt than the combined total of the next nine largest Texas counties, which have a population of more than 10 million people. Local governments have argued that the state has refused to fund necessary projects, thereby forcing them to assume increasing debt. Through a bond election in 2013, Harris County asked its voters to allow the county to borrow almost $300 million. The first bond proposal was for $217 million to renovate and restore the Astrodome; this borrowing would have required higher property taxes. Additionally, Harris County wanted $70 million in bond money to establish a city-county jail processing center. The Astrodome bond issue failed, whereas the jail processing center passed. As of 2014, Harris County has higher per capita property taxes than any other county in Texas.

To confront problems and make local governments more responsive to citizens' needs and wishes, people have to understand how those governments are organized and what they do. Local government comes in many forms. Texas has municipalities (approximately 1,200 city and town governments), counties (254), and special districts (more than 3,000). The special district that most students know best is the school district, but there are also special districts for water, hospitals, conservation, housing, and a multitude of other services. Each local government covers a certain geographic area and has legal authority to carry out one or more government functions. Most collect revenue such as taxes or fees, spend money while providing services, and are controlled by officials ultimately responsible to voters. These local, or grassroots, governments affect our lives directly.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-1 Local Politics in Context

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-1 Local Politics in Context

LO 3.1

Explain the relationships that exist between a local government and all other governments, including local, state, and national governments.

Who are the policymakers for grassrootsLocal (as in grassroots government or grassroots politics). governments? How do they make decisions? What challenges do they face daily? Putting local politics in context first requires an understanding of the place of local government in American federalism.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-1a Local Governments and Federalism

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-1a Local Governments and Federalism

In the 19th century, two opposing views emerged concerning the powers of local governments. Dillon's RuleA legal principle, still followed in the majority of states including Texas, that local governments have only those powers granted by their state government., named after federal judge John F. Dillon and still followed in most states (including Texas), dictates that local governments have only those powers granted by the state government, those powers implied in the state grant, and those powers indispensable to their functioning. The opposing Cooley Doctrine, named after Michigan judge Thomas M. Cooley and followed in 10 states, says “Local Government is a matter of absolute right; and the state may not take it away.”

Texas's local governments, like those of other states, are at the bottom rung of the governmental ladder, which makes them politically and legally weaker than the state and federal governments. In addition, Texas is among those states that more strictly follow Dillon's Rule. Cities, counties, and special district governments are creatures of the State of Texas. They are created through state laws and the Texas Constitution, and they make decisions permitted or required by the state. Local governments may receive part of their money from the state or national government, and they must obey the laws and constitutions of both. States often complain about unfunded mandates (requirements placed on states by the federal government without federal money to pay the costs). Local governments face mandates from both the national and state governments. Some of these mandates are funded by the higher levels of government, but some are not. Examples of mandates at the local level are as diverse as improving the quality of the air, meeting state jail standards, providing access for the disabled, and meeting both federal and state educational standards.

At the local level, federalism is more than just dealing with the state and national governments. Local governments have to deal with each other as well. Texas has almost 5,000 local governments. Bexar County (home of San Antonio) has 62 local governments, Dallas County has 61, and Travis County (Austin) has 121. The territories of local governments often overlap. Your home, for example, may be in a county, a municipality, a school district, a community college district, and a hospital district—all of which collect taxes, provide services, and hold elections.

Local governments generally treat each other as friends but occasionally behave as adversaries. For example, the City of Houston and Harris County worked with each other, as well as with state and national officials, to coordinate the response to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Ike. On the other hand, a small city along the border, La Villa, has been in a dispute with the school district over high water rates. In 2014, the city shut off the school district's water after they refused to pay their bill, impacting over 600 students. Clearly, federalism and the resulting relationships between and among governments (intergovernmental relationsRelationships between and among different governments that are on the same or different levels.) are important to how local governments work. (For more on federalism, see Chapter 2, “Federalism and the Texas Constitution.”)

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-1b Grassroots Challenges

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-1b Grassroots Challenges

When studying local governments, it is important to keep in mind the challenges these governments face daily. More than 80 percent of all Texans reside in cities, and residents have immediate concerns they want addressed: fear of crime; decaying infrastructures, such as streets, roads, and bridges; controversies over public schools; and the threat of terrorism. Residents' concerns can be addressed in part through communication between government and citizens. For example, the City of Austin has created several Internet websites to inform and engage its citizens on issues. SpeakupAustin! is an online social media portal that was developed with the younger residents of the city in mind. The site gives information on city projects, has a forum for different political and social topics, and allows users to vote and share their opinions on issues. The city has a website, austintexas.gov, that provides resources for all areas of city government, including paying city service bills, business updates, city council emails, and more.

Learning Check 3.1

Do local governments have more flexibility to make their own decisions under Dillon's Rule or the Cooley Doctrine? Which one does Texas follow?

Are intergovernmental relations marked by conflict, cooperation, or both?

Texas cities are also becoming increasingly diverse, with many African American and Latino Texans seeking access to public services and local power structures long dominated by Anglos. Making sure that all communities receive equal access to public services is a key challenge for grassroots-level policymakers, community activists, and political scientists. Opportunities to participate in local politics begin with registering and then voting in local elections. (See Chapter 5, “Campaigns and Elections,” for voter qualifications and registration requirements under Texas law.) Some citizens may even seek election to a city council, county commissioners court, school board, or another policymaking body. Additional opportunities to be politically active include homeowners' associations, neighborhood associations, community or issue-oriented organizations, voter registration drives, and election campaigns of candidates seeking local offices. By gaining influence in city halls, county courthouses, and special district offices, individuals and groups may address grassroots problems through the democratic process.

Grassroots government faces the challenge of widespread voter apathy. Many times, fewer than 10 percent of a community's qualified voters participate in a local election. The good news is that voter interest increases when people understand that they can solve grassroots problems in Texas through political participation.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-2 Municipal Governments

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-2 Municipal Governments

LO 3.2

Describe the forms of municipal government organization.

Perhaps no level of government influences the daily lives of citizens more than municipal (city) governmentA local government for an incorporated community established by law as a city.. Whether taxing residents, arresting criminals, collecting garbage, providing public libraries, or repairing streets, municipalities determine how millions of Texans live. Knowing how and why public policies are made at city hall requires an understanding of the organizational and legal framework within which municipalities function.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-2a Legal Status of Municipalities

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-2a Legal Status of Municipalities

City government powers are outlined and restricted by municipal charters, state and national constitutions, and statutes (laws). Texas has two legal classifications of cities: general-law citiesA municipality with a charter prescribed by the legislature. and home-rule citiesA municipality with a locally drafted charter.. A community with a population of 201 or more may become a general-law city by adopting a charter prescribed by a general law enacted by the Texas legislature. A city of more than 5,000 people may be incorporated as a home-rule city, with a locally drafted charter adopted, amended, or repealed by majority vote in a citywide election. Once chartered, a general-law city does not automatically become a home-rule city just because its population increases to greater than 5,000 people. Citizens must vote to become a home-rule city, but that status does not change even if the municipality's population decreases to 5,000 or fewer people.

Texas has almost 900 general-law cities, most of which are fairly small in population. Although some of the more than 350 home-rule cities are small, most larger cities tend to have home-rule charters. The principal advantage of home-rule cities is greater flexibility in determining their organizational structure and how they operate. Citizens draft, adopt, and revise their city's charter through citywide elections. The charter establishes the powers of municipal officers; sets salaries and terms of offices for council members and mayors; and spells out procedures for passing, repealing, or amending ordinancesA local law enacted by a city council or approved by popular vote in a referendum or initiative election. (city laws).

Home-rule cities may exercise three powers not held by the state government or general-law cities: recall, initiative, and referendum. RecallA process for removing elected officials through a popular vote. In Texas, this power is available only for home-rule cities. provides a process for removing elected officials through a popular vote. In November 2013, two members of the city council for Cibolo City, outside of San Antonio, were recalled by voters. The recall was initiated by citizens who opposed the council members' approval of plans for a Walmart to be built in the community. Recall elections in Texas have become more common and can cost a community many thousands of dollars. An initiativeA citizen-drafted measure proposed by a specific number or percentage of qualified voters, which becomes law if approved by popular vote. In Texas, this process occurs only in home-rule cities. is a citizen-drafted measure proposed by a specified number or percentage of qualified voters. If approved by popular vote, an initiative becomes law without city council approval, whereas a referendumA process by which issues are referred to the voters to accept or reject. Voters may also petition for a vote to repeal an existing ordinance. In Texas, this process occurs at the local level in home-rule cities. At the state level, bonds secured by taxes and state constitutional amendments must be approved by the voters. approves or repeals an existing ordinance. Ballot referenda and initiatives require voter approval and, depending on city charter provisions, may be binding or nonbinding on municipal governments.

Initiatives and referenda can be contentious. For example, in November 2012, Austin voters passed an initiative to change the election system for city council members from a place system, in which council members were elected at large (voted on by all citizens), to single-member districts (voted on by citizens from within a specific geographic area). One controversy resulting from the new election system is the concern that council members will focus more on issues in their districts and less on citywide issues. Austin's mayor, elected at large, will need to draw some consensus among council members to help Austin continue to grow and move forward. On occasion, implementation of voters' decisions may be slow or blocked.

Red-light cameras installed by various cities to reduce the number of accidents (and, according to critics, produce more municipal revenue) brought popular votes over repeal in some communities. In College Station and Baytown, city councils responded to the citizens' rejection of the cameras by turning them off promptly. Voters in Houston rejected the cameras in 2010, but because of legal issues the cameras were not turned off definitively until more than a year after the election. A suit by the company administering the program for the city was not settled until 2012. In Sugar Land, a suburb of Houston, residents petitioned the city to put the red-light camera system on their November 2013 ballot, but the city council tossed out the petition. The city cited technicalities, stating that the petition did not include some names and addresses of petitioners and was not submitted by the required deadline.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-2b Forms of Municipal Government

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-2b Forms of Municipal Government

The four principal forms of municipal government used in the United States and Texas—strong mayor-council, weak mayor-council, council-manager, and commission—have many variations. The council-manager form prevails in almost 90 percent of Texas's home-rule cities, and variations of the two mayor-council systems operate in many general-law cities. Citizens often ask, “How do you explain the structure of municipal government in my town? None of the four models accurately depicts our government.” The answer lies in home-rule flexibility. Various combinations of the forms discussed in the following sections are permissible under a home-rule charter, depending on community preference, as long as they do not conflict with state law. Informal practice also may make it hard to define a city's form. For example, the council-manager form may work like a strong mayor-council form if the mayor has a strong personality and the city manager is timid.

Strong Mayor-Council

Among larger American cities, the strong mayor-council formA type of municipal government with a separately elected legislative body (council) and an executive head (mayor) elected in a citywide election with veto, appointment, and removal powers. continues as the predominant governmental structure. Among the nation's 10 largest cities, only Dallas, San Antonio, and San Jose, California, operate with a structure (council-manager) other than some variation of the strong mayor-council system. In New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia, the mayor is the chief administrator and the political head of the city. Of Texas's 25 largest cities, however, only Houston and Pasadena still have the strong mayor-council form of government. Many people see the strong mayor-council system as the best form for large cities because it provides strong leadership and is more likely than the council-manager form to be responsive to the full range of the community. In the early 20th century, however, the strong mayor-council form began to fall out of favor in many places, including Texas, because of its association with the corrupt political party machines that once dominated many cities. Now, most of Texas's home-rule cities have chosen the council-manager form.

In Texas, cities operating with the strong mayor-council form have the following characteristics:

A council traditionally elected from single-member districts, although many now have a mix of at-large and single-member district elections

A mayor elected at large (by the whole city), with the power to appoint and remove department heads

Budgetary power (for example, preparation and execution of a plan for raising and spending city money) exercised by the mayor, subject to council approval before the budget may be implemented

A mayor with the power to veto council actions

Houston's variation of the strong mayor-council form features a powerful mayor aided by a strong appointed chief of staff and an elected controller with budgetary powers (see Figure 3.1). Most Houston mayors have delegated administrative details to the chief of staff, leaving the mayor free to focus on the larger picture. Duties of the chief of staff, however, vary widely depending on the mayor currently in office.

Figure 3.1

Strong Mayor-Council Form of Municipal Government: City of Houston

http://www.houstontx.gov/budget/11budadopt/orgchrt.pdf.

Critical Thinking

What is the difference between the strong mayor-council and weak mayor-council form of government?

Weak Mayor-Council

As the term weak mayor-council formA type of municipal government with a separately elected mayor and council, but the mayor shares appointive and removal powers with the council, which can override the mayor's veto. implies, this model of local government gives the mayor limited administrative powers. The mayor's position is weak because the office shares appointive and removal powers over municipal government personnel with the city council. Instead of being a chief executive, the mayor is merely one of several elected officials responsible to the electorate. In popular elections, voters choose members of the city council, some department heads, and other municipal officials. The city council has the power to override the mayor's veto.

The current trend is away from this form. None of the largest cities in Texas has the weak mayor-council form, though some small general-law and home-rule cities in Texas and other parts of the country use it. For example, Conroe, a city with a population of more than 55,000 in Montgomery County (north of Houston), describes itself on its website as having a mayor-council form of government. The mayor's powers are limited, and the city administrator manages city departments on a day-to-day basis. The mayor, however, maintains enough status to serve as a political leader.

Council-Manager

When the cities of Amarillo and Terrell adopted the council-manager formA system of municipal government in which an elected city council hires a manager to coordinate budgetary matters and supervise administrative departments. in 1913, a new era in Texas municipal administration began. Today, most of Texas's almost 350 home-rule cities follow the council-manager form (sometimes termed the commission-manager form).

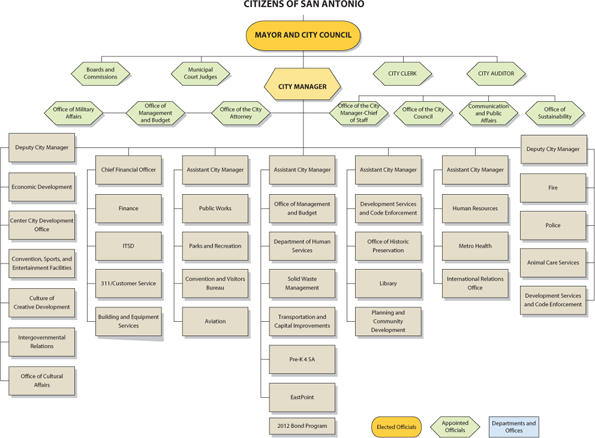

Figure 3.2 illustrates how this form is used in San Antonio. The council-manager form has the following characteristics:

A mayor, elected at large, who is the presiding member of the council but who generally has few formal administrative powers

City council or commission members elected at large or in single-member districts to make general policy for the city

A city manager who is appointed by the council (and can be removed by the council) and who is responsible for carrying out council decisions and managing the city's departments

Figure 3.2

Council-Manager Form of Government: City of San Antonio (2014)

http://www.sanantonio.gov/Portals/0/Files/manager/jan2014.pdf

Critical Thinking

What advantages does the city manager have in this form of government over the mayor? What concerns would citizens have about this form of government and why?

Under the council-manager form, the mayor and city council make decisions after debate on policy issues, such as taxation, budgeting, annexation, and services. The city manager's actual role varies considerably; however, most city managers exert strong influence. City councils generally rely on their managers for the preparation of annual budgets and policy recommendations. Once a policy is made, the city manager's office directs an appropriate department to implement it. Typically, city councils hire professionally trained managers. Successful applicants usually possess graduate degrees in public administration and can earn competitive salaries. In 2014, city managers for Texas's five largest cities earned $233,000 to $400,000 annually, plus bonuses. Dallas pays its city manager $400,000, the highest salary in the country, plus benefits. Obviously, a delicate relationship exists between appointed managers and elected council members. In theory, the council-manager system has a weak mayor and attempts to separate policymaking from administration. Councils and mayors are not supposed to “micromanage” departments. However, in practice, elected leaders sometimes experience difficulties in determining where to draw the line between administrative oversight and meddling in departmental affairs.

A common major weakness of the council-manager form of government is the lack of a leader to whom citizens can bring demands and concerns. The mayor is weak; the city council is composed of a number of members (anywhere from 4 to 16 individuals, with an average of 7, among the 25 largest cities in Texas); and the city manager is supposed to “stay out of politics.” Thus, council-manager cities tend to respond more to elite and middle-classSocial scientists identify the middle class as those people with white-collar occupations (such as professionals and small business workers). concerns than to those of the working classSocial scientists identify the working class as those people with blue-collar (manual) occupations. and ethnic minorities. (The business elite and the middle class have more organizations and leaders who have access to city government and know how to work the system.) Only a minority of council-manager cities have mayors who regularly provide strong political and policy leadership. One of these exceptions is San Antonio, where mayors, due to personality, generally are strong leaders. The council-manager form seems to work well in cities where most people are of the same ethnic group and social class and, thus, share many common goals. Obviously, few central cities fit this description, but many suburbs do.

Commission

Learning Check 3.2

Name the two legal classifications of cities in Texas and indicate which has more flexibility in deciding its form and the way it operates.

Which form of municipal government is most common in Texas's larger home-rule cities? In smaller cities?

Today, none of Texas's cities operates under a pure commission formA type of municipal government in which each elected commissioner is a member of the city's policymaking body, but also heads an administrative department (e.g., public safety with police and fire divisions). of municipal government. First approved by the Texas legislature for Galveston after a hurricane demolished the city in 1900, this form lacks a single executive, relying instead on elected commissioners that form a policymaking board.

In the commission form, each department (for example, public safety, finance, public works, welfare, or legal) is the responsibility of a single commissioner. Most students of municipal government criticize this form's dispersed administrative structure and lack of a chief executive. The few Texas municipalities that have a variation of the commission form operate more like the mayor-council form and designate a city secretary or another official to coordinate departmental work.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-3 Municipal Politics

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-3 Municipal Politics

LO 3.3

Identify the rules and social issues that shape local government outcomes.

Election rules and socioeconomic change make a difference in who wins and what policies are more likely to be adopted. This section examines several election rules that affect local politics. It then looks at social changes that affect the nature of local politics in Texas.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-3a Rules Make a Difference

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-3a Rules Make a Difference

All city and special district elections in Texas are nonpartisan electionsAn election in which candidates are not identified on the ballot by party label.. That is, candidates are listed on the ballot without party labels in order to reduce the role of political parties in local politics. This system succeeded for a long time. However, party politics is again becoming important in some city elections, such as those in the Houston and Dallas metropolitan areas.

Nonpartisan elections have at least two negative consequences. First, without political parties to stir up excitement, voter turnout tends to be low compared with state and national elections. Studies of voting patterns in the United States suggest that voters are racially polarized (that is, people tend to vote for candidates of their own race or ethnicity). Because those who do vote are more likely to be Anglos and middle class, the representation of ethnic minorities and the working class is reduced. San Antonio, for example, has a majority Latino population, but the greater Anglo voter turnout has meant that most San Antonio mayors have been Anglo. The three recent exceptions have been Mexican Americans who have appealed to both Anglos and Latinos (Henry Cisneros, Edward Garza, and Julián Castro). A second problem is that nonpartisan elections tend to be more personal and less issue oriented. Thus, voters tend to vote for personalities, not issues. In smaller cities and towns, local elections are often decided by who has more friends and neighbors.

The two most common ways of organizing municipal elections are the at-large electionMembers of a policymaking body, such as some city councils, are elected on a citywide basis rather than from single-member districts., in which council members are elected on a citywide basis, and the single-member district electionVoters in an area (commonly called a district, ward, or precinct) elect one representative to serve on a policymaking body (e.g., city council, county commissioners court, state House and Senate)., in which voters cast a ballot only for a candidate who resides within their district. Texas municipalities have long used at-large elections. However, this system was challenged because it tended to overrepresent the majority Anglo population and underrepresent ethnic minorities. In at-large elections, the city's majority ethnic group tends to be the majority in each electoral contest. This electoral structure works to the disadvantage of ethnic minorities.

Throughout the country, representative bodies whose members are elected from districts (such as the state legislature and city councils) must redistrictRedrawing of boundaries after the federal decennial census to create districts with approximately equal population (e.g., legislative, congressional, commissioners court and city council districts in Texas). (redraw their districts) after every 10-year census. (As we will see later, this also applies to county commissioners courts and some school boards.) After the 2010 census, Texas's city council districts had to be redrawn because of shifts in population within cities and between districts. In 1975, because of its history of racial discrimination, Texas was placed under a provision of the federal Voting Rights Act that required governments to receive clearance from the U.S. attorney general or the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia for rule changes in voting. However, the Supreme Court case of Shelby v. Holder (2013) altered preclearance. The Court ruled Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act, which set the formula for determining which states and local governments required preclearance, unconstitutional. Section 5 still allows preclearance, but the Supreme Court's holding now requires new lawsuits for a voting jurisdiction to be brought back under Section 5 through a process called “bailing in.” As of 2014, “bailing in” lawsuits had been filed against Texas and the cities of Galveston and Beaumont. In January 2014, several members of the U.S. Congress proposed the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2014 to reassert federal oversight of voting in Texas and three other states (Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi). Despite calls for action from religious groups and civil rights organizations, Congress did not vote on the bill.

In recent decades, the major controversy over redistricting at the local level has been the issue of the representation of Texas's major ethnic groups—particularly Latinos, who were the main source of the state's population growth in the 2010 census. Expansion of the Latino population in urban areas has increased the number of districts in which Latino candidates have a better chance of winning. Low Latino turnout, however, has limited the number of Latino council members who are actually elected.

In 2011, Houston struggled with increasing Latino representation while also providing representation of African Americans, Asian Americans, and Anglos. The final 2011 redistricting plan included four majority Hispanic districts, two majority African American districts, three majority Anglo districts, and two without a majority of one group. (A Latino opportunity district, for example, is one in which there is a large enough population of Latinos to give a Latino candidate a good chance of winning.) Asian Americans were 18 percent of one of the districts with no single ethnic majority. (There were also five at-large positions elected by the whole city.) In the elections that year, two of the Hispanic majority districts were won by Hispanics, two by Anglos. Blacks won the two African American majority districts and one in which there was no ethnic majority. An Asian American won the other district without an ethnic majority. Anglos won all three Anglo majority districts. In 2013, of the 16 positions on the Houston City Council, four were won by African Americans, two by Latinos, one by an Asian American, and the remaining nine by Anglos.

Dividing a city into single-member districts tends to create some districts with a majority of historically excluded ethnic minorities, thereby increasing the chance of electing a Latino, African American, or Asian American candidate to the city council. Prompted by lawsuits and ethnic conflict, 20 of Texas's 25 largest cities have adopted single-member districts or a mixed system of at-large and single-member districts. Houston, for example, has 5 council members elected at large (citywide) and 11 elected from single-member districts. Increased use of single-member districts has led to more ethnically and racially diverse city councils. Low voter turnout by an ethnic group, however, can reduce the effect of single-member districts, as happened in Houston in 2011.

Approximately 50 Texas local governments (including 40 school districts) use cumulative votingWhen multiple seats are contested in an at-large election, voters cast one or more of the specified number of votes for one or more candidates in any combination. It is designed to increase representation of historically underrepresented ethnic minority groups. to increase minority representation. In this election system, voters cast a number of votes equal to the positions available and may cast them for one or more candidates in any combination. For example, if eight candidates vie for four positions on the city council, a voter may cast two votes for Candidate A, two votes for Candidate B, and no votes for the other candidates. By the same token, a voter may cast all four votes for Candidate A. In the end, the candidates with the most votes are elected to fill the four positions.

Where racial minority voters are a numerical minority, cumulative voting increases the chances that they will have some representation. The largest government entity in the country to use cumulative voting is the Amarillo Independent School District, which adopted the system in 1999 in response to a federal Voting Rights Act lawsuit. The district was 30 percent minority but had no minority board members for two decades. With the adoption of cumulative voting, African American and Latino board members were elected.

Home-rule cities may also determine whether to institute term limitsA restriction on the number of terms officials can serve in a public office. for their elected officials. Beginning in the 1990s, many cities, including San Antonio and Houston, amended their charters to institute term limits for their mayor and city council members. Houston has a limit of three two-year terms for its mayor. Although Houston's popular mayor, Bill White, won election in 2003 with 63 percent of the vote and was reelected twice with 91 and 86 percent of the vote, he could not run again in 2009. (In 2010, he was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee for governor.) In 2008, San Antonio changed its limits from two to four two-year terms for its mayor and city council members, a move expected to make it easier for Latino city council members to build the support necessary to run for mayor. Both supporters and opponents feel strongly about term limits. U.S. Term Limits (USTL) is a non-profit organization that lobbies for term limits in Texas and throughout the country.

Point/Counterpoint

Should Cities Adopt a Council-Manager Form of Government?

THE ISSUE The council-manager form of government is popular in the United States, and the same is true for many Texas cities. Yet most major cities in the United States, including New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and Houston, use the strong mayor-council form of government. Home-rule cities in Texas, which have a population of more than 5,000, can choose their form of local government. The following are arguments for and against the council-manager form of municipal government.

| Arguments For a Council-Manager Form | Arguments Against a Council-Manager Form |

|

|

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-3b Socioeconomic and Demographic Changes

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-3b Socioeconomic and Demographic Changes

It should be clear, then, that election rules make a difference in who is elected. Historical, social, and economic factors make a difference as well. Texas's increasing levels of urbanization, education, and economic development have made the state more economically, culturally, and politically diverse (or more pluralist). Local politics reflect these changes. Many Texas city governments were long dominated by elite business organizations, such as the Dallas Citizens Council and the San Antonio Good Government League. But greater pluralism and changes in election rules have given a say to a wider range of Texans in how their local governments function. Racial and ethnic conflict remains a problem in Texas, but communities are working to resolve their issues, albeit in differing ways and to different degrees. Growth in the population's size, amount of citizen organization, and income tend to increase the demands on local government and produce higher public spending.

Houston has long been Texas's most diverse local political system. It has a strong business community, many labor union members, an African American community with more than 80 years' experience in fighting for its views and interests, a growing and increasingly organized Latino community, an expanding Asian American community that is becoming more active, and an activist gay community. Multiethnic coalitions have been the norm in Houston's mayoral races for decades, and nonbusiness interests have significant, if variable, access to city hall.

Dallas has long had serious black-white racial tensions. Although these conflicts have not been resolved, changes in election rules have increased the number of racial minorities on the city council. In 1995, Dallas's Ron Kirk became the first African American in modern times elected mayor of a major Texas city.

In 1991, Austin elected its first Latino mayor, Gus Garcia; in 1998, Laredo elected its first Latina mayor, Betty Flores; and in 2009, San Antonio elected Julián Castro, the youngest mayor (at age 34) of a major U.S. city. Castro was reelected twice, but in 2014 he was appointed by President Obama to head the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Today, there are more Latino elected officials in Texas than in any other state, with most of them serving at the local level.

Since the 1970s, South Texas's majority Latino population has elected Latino (and some non-Latino) leaders at all levels. In the rest of the state, central cities and some near-in suburbs tend to have a majority of Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans, which gives these groups more electoral clout. Suburbs farther from the center tend to be predominantly Anglo and often heavily middle class, which produces more middle-class Anglo leaders. In Texas, as throughout the United States, an increasing number of ethnic and racial minority populations are moving to the suburbs. Clearly, the face of local government has changed as a result of increased use of single-member districts; greater pluralism in the state; and the growing number, organization, and political activity of minority Texans.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-3c Municipal Services

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-3c Municipal Services

Most citizens and city officials believe city government's major job is to provide basic services that affect people's day-to-day lives: police and fire protection, streets, water, sewer and sanitation, and perhaps parks and recreation. These basic services tend to be cities' largest expenditures, though the amounts spent vary from city to city. Municipalities also regulate important aspects of Texans' lives, notably zoning, construction, food service, and sanitation.

Zoning ordinances regulate the use of land, for instance, by separating commercial and residential zones, because bringing businesses into residential areas often increases traffic and crime. Zoning has received more opposition in Texas than in most other states, although its use is growing. Among Texas's 10 largest municipalities, only Houston has no zoning authority, though the city does help enforce deed restrictions that protect neighborhoods and uses its control of access to utilities to control and direct growth. Developers in Houston use private covenants and deed restrictions in place of city zoning laws. Citizens with complaints about deed restrictions may receive help from the city in resolving issues. Although there are no zoning laws, development is governed by city codes that address how property can be subdivided. For example, there are requirements on lot size and minimum parking.

Students in Action

Service in the Community

“Working within the community provided an experience in government that I could not have learned in a classroom. It truly exposes the individual needs of those within the community and gives you the sense that you can actually make a difference.”

— Kaitlin Piraro

Kaitlin Piraro worked for the City of Austin part-time at the Dittmar Recreation Center from the spring of 2011 through fall 2012. As a counselor, she worked one-on-one with children aged 5 to 11 in the recreation center's after-school program. Her primary responsibility was to keep the youth, who were from local neighborhoods, focused on positive after-school activities. Kaitlin soon volunteered to work on the teen art project at the center. She provided specific classes for the students in art, cooking, sculpture, painting, and film. She found that introducing new projects to the students was rewarding and they were excited to be involved in interactive learning. Selected art projects were shown at local galleries in Austin. At the end of the semester, Kaitlin worked with others at the center to create an awards ceremony to recognize the students' hard work. She learned how to work with young students, coordinate projects, and communicate with parents and others in the community.

This experience opened Kaitlin's eyes to local bureaucracy, how it works, and how it helps communities. Her hope is to someday work again with city government. She believes that opportunities to work in community projects, as a volunteer, intern, or paid employee, are a great way to learn firsthand about government. Her advice to other students is to explore all possible community projects, so that they can give back and learn more about the needs of their community.

Interview with Kaitlin Piraro on February 24, 2014

© Andresr/Shutterstock.com

Over time, many Texas cities have added libraries, airports, hospitals, community development, and housing to their list of services. Scarce resources (particularly money) of local governments increase competition between traditional services and newer services demanded by citizens or the state and national governments, such as protection of the homeless, providing elder services and job training, fighting air pollution, and delinquency prevention. These competing demands for municipal spending often result in controversy, thus requiring elected officials to make difficult decisions.

The Denton City Council discusses a grassroots petition to ban hydraulic fracking.

AP Images/Tony Gutierrez

Critical Thinking

What are the political and economic ramifications for Texas if cities passed ordinances to ban hydraulic fracturing?

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-3d Municipal Government Revenue

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-3d Municipal Government Revenue

Most city governments in Texas and the nation face a serious financial dilemma: they barely have enough money to provide basic services and thus must reject or shortchange new services. Cities' two largest tax sources—sales and property taxes—are limited by state law. These taxes produce inadequate increases in revenue as the population grows, and they are regressive (that is, they put a heavier burden on those who make less money). Moreover, Texas voters are increasingly hostile to higher property taxes. Adding to the problem are low levels of state assistance to Texas cities as compared with the pattern exhibited in many other states. As a result, Texas cities are relying more heavily on fees (such as liquor licenses, franchise fees for cable television companies, and water rates) and are going into debt. Per capita local government debt in Texas, for example, was nearly five times greater than state government debt for the whole country as of 2013.

Local governments were hurt by the recent “Great Recession,” particularly the decrease in property values (which are the basis of property taxes) and the slowing of sales tax receipts. The 2009 federal stimulus bill provided $16.8 billion to Texas, but most of that money went to the state rather than to local governments. The major revenue sources for local government, property and sales tax receipts, have grown in counties and municipalities with oil and gas development. Nevertheless, local governments must contend with the costs of growth due to oil and gas exploration and production, including road repairs and sewer and water infrastructure. In 2013, the legislature passed a bill to allocate roughly $225 million to counties to assist with cost of road repairs due to oil and gas activity. This legislative action shows state government's willingness to provide limited assistance for local governments.

Taxes

The state of Texas allows municipalities to levy taxes based on the value of property (property taxA tax that property owners pay according to the value of real estate and other tangible property. At the local level, property owners pay this tax to the city, the county, the school district, and often other special districts.). The tax rate is generally expressed in terms of the amount of tax per $100 of the property's value. This rate varies greatly from one city to another. In 2012 (the most recent year for comprehensive data), rates varied from 5 cents per $100 valuation to $1.52, with an average of 52 cents. A problem with property taxes is that poorer cities with low property values must charge a high rate to provide minimum services. In the Dallas area, for example, in 2012 Highland Park had an annual median family income of $247,000 and set a property tax rate of 22 cents per $100 in valuation. Wylie (north of Dallas) had an annual median family income of $82,000 and set its tax rate at 90 cents per $100 in valuation.

The other major source of city tax revenue is the optional 1¼–2 percent sales tax that is collected along with the state sales tax. Local governments are in competition for sales tax dollars. The sum of city, county, and special district government sales taxes cannot exceed 2 percent. So, for example, a city might assess 1 percent; the county, 0.5 percent; and a special district, 0.5 percent. In order to prevent going over the cap of 2 percent, state law sets up the order in which sales taxes are required to be collected. First to collect is the city, then the county, and third are special districts. Further, voters must approve the imposition of a local sales tax within their jurisdiction. An additional problem is that sales tax revenues fluctuate with the local economy, making it difficult to plan how much money will be available. The hotel occupancy tax is another significant source of revenue for cities with tourism or major sports events, such as the NFL Super Bowl or the NCAA Final Four.

Fees

Lacking adequate tax revenues to meet the demands placed on them, Texas municipalities have come to rely more heavily on fees (charges for services and payments required by an agency upon those subject to its regulation). Cities levy fees for such things as beer and liquor licenses and building permits. They collect traffic fines and may charge franchise fees based on gross receipts of public utilities (for example, telephone and cable television companies). Texas municipalities are authorized to own and operate water, electric, and gas utility systems that may generate a profit for the city. Charges also are levied for such services as sewage treatment, garbage collection, hospital care, and use of city recreation facilities. User fees may allow a city to provide certain services with only a small subsidy from its general revenue fund or perhaps no subsidy at all.

Bonds and Certificates of Obligation

Taxes and fees normally produce enough revenue to allow Texas cities to cover day-to-day operating expenses. Money for capital improvements (such as construction of city buildings or parks) and emergencies (such as flood or hurricane damage) often must be obtained through the sale of municipal bondsA mechanism by which governments borrow money. General obligation bonds (redeemed from general revenue) and revenue bonds (redeemed from revenue obtained from the property or activity financed by the sale of the bonds) are authorized under Texas law., which may be redeemed over periods of 1 to 30 years. The Texas Constitution allows cities to issue bonds, but any bond issue to be repaid from taxes must be approved by the voters. During the recent recession, local governments made more use of certificates of obligation, which do not require voter approval and typically reach maturity in 15 to 20 years. The certificates traditionally have been used for smaller amounts and short-term financing.

Property Taxes and Tax Exemptions

Property owners pay taxes on the value of their homes and businesses not just to the city but also to the county, the school district, and often other special districts. When property values or tax rates go up, the total tax bill goes up as well. To offset the burden of higher taxes resulting from reappraisals of property values, local governments (including cities) may grant homeowners up to a 20 percent homestead exemption on the assessed value of their homes. Cities may also provide an additional homestead exemption for disabled veterans and their surviving spouses, for homeowners 65 years of age or older, or for other reasons such as adding pollution controls.

Cities, counties, and community college districts may also freeze property taxes for senior citizens and the disabled. Property tax caps (or ceilings) can be implemented by city council action or by voter approval. The dilemma is that cities can help their disadvantaged citizens, but doing so costs the city revenue. In 2013, exemptions cost Texas cities an estimated $43.9 billion in revenue. As baby boomers reach retirement age, exemptions and property tax caps will reduce revenue even further. Table 3.1 illustrates property taxes from different local governments and the consequences of exemptions and caps.

Table 3.1

One Home but Property Taxes from Four Governments (An Example from Walker County on a Home with an Appraised Value of $120,220; Taxes Paid in January 2014)

Sources: Calculated by the author from data and rules provided by Walker County Appraisal District, http://www.walkercountyappraisal.com, and Texas Comptroller, http://www.window.state.tx.us/taxes.

Critical Thinking

Would it be fair for local governments to give further exemptions to those in need, or is it unfair to shift the burden to other homeowners?

The Bottom Line

Because of pressure against increasing property tax rates, municipal governments sometimes refrain from increased spending, cut services or programs, or find new revenue sources. Typically, city councils are forced to opt for one or more of the following actions:

Create new fees or raise fees on services such as garbage collection

Impose hiring and wage freezes for municipal employees

Cut services (such as emergency rooms) that are especially important for inner-city populations

Contract with private firms for service delivery

Improve productivity, especially by investing in technology

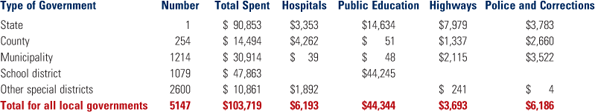

How Do We Compare … in Funding Services at State and Local Levels?

Texas Expenditures (in millions of dollars)

Source: U.S. Census of Governments, 2007, Revised October 24, 2011, http://www.census.gov. A Census of Governments was conducted in 2012, but results will be released over several years. More recent total expenditure data are available for the state and all local governments taken together, but the Census of Governments provides the breakdown for each form of local government. Expenditures are Direct General Expenditures for the function. Totals may vary because of rounding.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-3e Generating Revenue for Economic Development

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-3e Generating Revenue for Economic Development

Learning Check 3.3

Which of the following election forms tend to increase the representation of minorities in local government: nonpartisan elections, redistricting, at-large elections, single-member district elections, or cumulative voting?

What are the two largest tax sources that provide revenue to local governments? Do these taxes usually provide enough revenue for local governments to meet the demands placed on them?

State and federal appropriations to assist cities are shrinking, especially for economic development. Inner cities face the challenge of dilapidated housing, abandoned buildings, and poorly maintained infrastructure (such as sewers and streets). This neglect blights neighborhoods and contributes to social problems such as crime and strained racial relations. Texas cities do have the local option of a half-cent sales tax for infrastructure upgrades, such as repaving streets and improving sewage disposal. The increased sales tax, however, must stay within the 2 percent limit the state imposes on local governments. Following a national trend, some Texas cities are trying to spur development by attracting businesses through tax incentives. The Texas legislature authorizes municipalities to create tax reinvestment zonesAn area in which municipal tax incentives are offered to encourage businesses to locate in and contribute to the development of a blighted urban area. Commercial and residential property taxes may be frozen. (TRZs) to use innovative tax breaks to attract investment in blighted inner cities and other areas needing development. Major cities using TRZs include Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin, San Antonio, and El Paso. Smaller cities also have used TRZs. Whether such plans work is controversial. Many observers of similar plans argue that companies attracted by tax breaks often make minimal actual investments and leave as soon as they have realized a profit from tax subsidies. Yet, because TRZs sometimes work, many cities starved for the monetary resources to combat decay are willing to take the gamble.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-4 Counties

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-4 Counties

LO 3.4

Analyze the structure and responsibilities of counties.

Texas countiesTexas is divided into 254 counties that serve as an administrative arm of the state and that provide important services at the local level, especially in rural areas. present an interesting set of contradictions. They are technically an arm of the state, created to serve its needs, but both county officials and county residents see them as locally controlled governments and resent any state “interference.” Counties collect taxes on both urban and rural property but focus more on the needs of rural residents and people living in unincorporated suburbs, who do not have city governments to provide services. This form of county government, out of the 19th century, serves 21st-century Texans.

Texas is divided into 254 counties, the most of any state in the nation. The basic form of Texas counties is set by the state constitution, though their activities are heavily shaped by whether they are in rural or metropolitan areas. As an agent of the state, each county issues state automobile licenses, enforces state laws, registers voters, conducts elections, collects certain state taxes, and helps administer justice. In conjunction with state and federal governments, the county conducts health and welfare programs, maintains records of vital statistics (such as births and deaths), issues various licenses, collects fees, and provides a host of other public services. Yet state supervision of county operations is minimal. Rural counties generally try to keep taxes low and provide minimal services. They are reluctant to take on new jobs, such as regulating septic systems and residential development. In metropolitan areas, however, counties have been forced by citizen demands and sometimes the state to take on varied urban tasks such as providing ballparks and recreation centers, hospitals, libraries, airports, and museums. Bexar County, which includes the city of San Antonio, created a digital library, bexarbibliotech.org. This program is one of the first of its kind in the United States; it's a bookless public library where patrons scan their library cards and then check out or return virtual books. Visitors can download e-books on their tablets or e-readers, or if they don't have their own they may check out one of 600 devices provided by the library. This system allows the library to reduce costs associated with books that are damaged or not returned, plus it introduces residents to e-technology.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-4a Structure and Operation

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-4a Structure and Operation

As required by the state constitution, all Texas counties have the same basic governmental structure, despite wide demographic and economic differences between rural and urban counties. (Contrast Figure 3.3, Harris County, the most populous Texas county with more than 4 million residents in 2010, with Figure 3.4, Loving County, the least populous with 82 residents in that year.)

Figure 3.3

Harris County Government (County Seat: Houston).

Compiled by author using FY2014-2015 Approved Budget, http://www.hctx.net/budget.

Critical Thinking

Do most citizens know the role of their county commissioners court? Why is it important for more citizens to understand its role?

Figure 3.4

Loving County Government (County Seat: Mentone) Second Smallest County in the Nation.

© Cengage Learning®

Critical Thinking

How does a county's population size change the job of the county commissioners court? Compare Figure 3.3 (Harris County) to Figure 3.4 (Loving County).

The Texas Constitution provides for the election of four county commissioners, county and district attorneys, a county sheriff, a county clerk, a district clerk, a county tax assessor-collector, a county treasurer, and constables, as well as judicial officers, including justices of the peace and a county judge. All elected county officials are chosen in partisan elections and serve four-year terms. In practice, Texas counties are usually highly decentralized, or fragmented. No one person has formal authority to supervise or coordinate the county's elected officials, who tend to think of their office as a personal fiefdom and to resent interference by other officials. Sometimes, however, the political leadership of the county judge produces cooperation.

Commissioners Court

All elected county officials make policies for their area of responsibility, but the major policymaking body is called the commissioners courtA Texas county's policymaking body, with five members: the county judge, who presides, and four commissioners representing single-member precincts.. Its members are the county judge, who presides, and four elected commissioners. The latter serve staggered four-year terms, so that two commissioners are elected every two years. Each commissioner is elected by voters residing in a commissioner precinct, thus commissioners are elected from single-member districts. Boundary lines for a county's four commissioner precincts are set by its commissioners court. Precincts must be of substantially equal population as mandated by the “one-person, one-vote” ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court in Avery v. Midland County 390 U.S. 474 (1968).

Like cities, counties must redistrict every 10 years, following the federal census. After the 2010 census, county redistricting battles centered on political party power in Dallas County, and racial and ethnic representation were major sources of conflict in Harris County (Houston), Galveston County, and Travis County (Austin). In Dallas County, the Democratic-controlled commissioners court added another Democratic seat, and the Republican majority on Harris County's commissioners court was sued over dilution of Latino votes. The Galveston County plan was rejected by the U.S. Department of Justice for diluting minority votes. Bexar County's (San Antonio) redistricting was less controversial than usual and was overshadowed by the battle over congressional redistricting. (For an in-depth discussion, see the Selected Reading in Chapter 8, “The Legislative Branch.”)

The term commissioners court is actually a misnomer because its functions are administrative and legislative rather than judicial. The court's major functions include the following:

Adopting the county budget and setting tax rates, which are the commissioners court's greatest sources of power and influence over other county officials

Providing a courthouse, jails, and other buildings

Maintaining county roads and bridges, which is often viewed by rural residents as the major county function

Administering county health and welfare programs

Administering and financing elections (general and special elections for the nation, state, and county)

Beyond these functions, a county is free to decide whether to take on other programs authorized, but not required, by the state.

In metropolitan areas, large numbers of people live in unincorporated communities with no city government to provide services such as police protection and water. Within those communities, the county takes on a multitude of functions. In rural areas, counties take on few new tasks, and residents are generally happy not to be “hassled” by too much government. County commissioners may have individual duties in addition to their collective responsibilities. Commissioners in counties that do not have a county engineer, for example, are commonly responsible for the roads and bridges in their respective precincts.

County Judge

The county judgeA citizen popularly elected to preside over the county commissioners court, and in smaller counties, to hear civil and criminal cases., who holds the most prominent job in county government, generally is the most influential county leader. This county officer presides over commissioners court, has administrative responsibility for most county agencies not headed by another elected official, and, in some counties, presides over court cases, but does not need to be a lawyer. Much of the county judge's power or influence comes from his or her leadership skills and from playing a lead role in the commissioners court's budget decisions. The judge has essentially no formal authority over other elected county officials.

County Attorney and District Attorney

The county attorneyA citizen elected to represent the county in civil and criminal cases, unless a resident district attorney performs some of these functions. represents the state in civil and criminal cases and advises county officials on legal questions. Nearly 50 counties in Texas do not elect a county attorney because a resident district attorney performs those duties. Other counties elect a county attorney but share the services of a district attorneyA citizen elected to serve one or more counties who prosecutes criminal cases, gives advisory opinions, and represents the county in civil cases. with one or more neighboring counties. Where there are both a county and a district attorney, the district attorney generally specializes in the district court cases, and the county attorney handles lesser matters in county and justice of the peace courts. District attorneys tend to be important figures in the criminal justice system because of the leadership they provide to local law enforcement and the discretion they exercise in deciding whether to prosecute cases. The legal advice of the county or district attorney carries considerable weight with other county officials.

If a vacancy occurs during a county attorney's term of office, this office is filled by the commissioners court. Although local voters choose the district attorney, the governor fills a vacancy that occurs between elections. In 2014, Governor Rick Perry was indicted by a Travis County grand jury for abuse of office involving his alleged attempts to force the resignation of Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg. A unique responsibility of the Travis County District Attorney's office is overseeing the Public Integrity Unit that is charged with the duty to investigate possible corruption of state-level officials. Complainants suggested that Perry sought Democrat Lehmberg's resignation after she pled guilty to driving while intoxicated, so he could replace her with a Republican district attorney who would be friendlier to Perry's appointees and other Republican elected officials.

County Sheriff

The county sheriffA citizen popularly elected as the county's chief law enforcement officer; the sheriff is also responsible for maintaining the county jail., as chief law enforcement officer, is charged with keeping the peace in the county. In this capacity, the sheriff appoints deputies and oversees the county jail and its prisoners. In practice, the sheriff's office commonly focuses on crime in unincorporated areas and leaves law enforcement in cities primarily to the municipal police. In a county with a population of fewer than 10,000, the sheriff may also serve as tax assessor-collector, unless that county's electorate votes to separate the two offices. In a few rural counties, the sheriff may be the county's most influential leader.

Law Enforcement and Judges

Counties have a number of officials associated with the justice system, ranging from sparsely populated Loving County to heavily populated Harris County. The judicial role of the constitutional county judge varies. In counties with a small population, the county judge may exercise important judicial functions such as handling probate matters, small civil cases, and serious misdemeanors. But in counties with a large population, county judges are so involved in their political, administrative, and legislative roles that they have little time for judicial functions. Instead, there are often statutory county courtsCourt created by the legislature at the request of a county; may have civil or criminal jurisdiction or both, depending on the legislation creating it. that have lawyers for judges and tend to operate in a more formal manner. In addition to the sheriff and county and district attorneys discussed above, there are the district clerk, justices of the peace, and constables. The district clerkA citizen elected to maintain records for the district courts. maintains records for the district courts.

Each county has from one to eight justice of the peace precincts. The number is decided by the commissioners court. Justice of the peace courts can also be abolished by a commissioners court, as occurred in Brazos County in 2014. Justices of the peaceA judge elected from a justice of the peace precinct who handles minor civil and criminal cases, including small claims court. (commonly called JPs) handle minor civil and criminal cases, including small claims court cases. Statewide, JPs hear a large volume of legal actions, with traffic cases representing a substantial part of their work. Other duties vary. In most counties, they also serve as coroner (to determine cause of death in certain cases) and as a magistrate (to set bail for arrested persons). Similar to the constitutional county court judge, they do not have to be lawyers but are required to take some legal training. ConstablesA citizen elected to assist the justice of the peace by serving papers and in some cases carrying out security and investigative responsibilities. assist the justice court by serving subpoenas and other court documents. They and their deputies are peace officers and may carry out security and investigative responsibilities. In some counties, they are an important part of law enforcement, particularly for rural areas of the county. Like other county officials, the judges, justices of the peace, district clerks, and constables are elected in partisan elections for four-year terms.

County Clerk and County Tax Assessor-Collector

A county clerkA citizen elected to perform clerical chores for the county courts and commissioners court, keep public records, maintain vital statistics, and administer public elections, if the county does not have an administrator of elections. keeps records and handles various paperwork chores for both the county court and the commissioners court. In addition, the county clerk files legal documents (such as deeds, mortgages, and contracts) in the county's public records and maintains the county's vital statistics (birth, death, and marriage records). The county clerk may also administer elections, though counties with larger populations often have an administrator of elections.

A county office that has seen its role decrease over time is the county tax assessor-collectorThis elected official no longer assesses property for taxation but does collect taxes and fees and commonly handles voter registration.. The title is partially a misnomer. Since 1982, the countywide tax appraisal districtThe district appraises all real estate and commercial property for taxation by units of local government within a county. assesses (or determines) property values in the county. The tax assessor-collector, on the other hand, collects county taxes and fees and certain state fees, including the license tag fees for motor vehicles and fees for handicapped parking permits. The office also commonly handles voter registration, although some counties have an elections administrator.

Treasurer and Auditor

The county treasurerAn elected official who receives and pays out county money as directed by the commissioners court. receives and pays out all county funds authorized by the commissioners court. If the office is eliminated by constitutional amendment, the county commissioners assign treasurer duties to another county office. Local voters allowed Tarrant and Bexar Counties to eliminate the office. These counties then authorized the county auditor to deal with responsibilities that were once held by the county treasurer. A county of 10,000 or more people must have a county auditorA person appointed by the district judge or judges to check the financial books and records of other officials who handle county money., appointed by the county's district court judges. The auditing function involves checking the account books and records of officials who handle county funds. Some observers worry that allowing the county auditor to perform both jobs of auditor and treasurer eliminates necessary checks and balances in county government.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 3: Local Governments: 3-4b County Finance

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

3-4b County Finance

Increasing citizen demands for services and programs impose on most counties an ever-expanding need for money. Just as the structure of county governments is frozen in the Texas Constitution, so is the county's power to tax and, to a lesser extent, its power to spend. Financial problems became even more serious for most counties during the recent Great Recession. As the state's economy strengthened beginning in 2012, so too did financial problems lessen.

Taxation

The Texas Constitution authorizes county governments to collect taxes on property, and that is usually their most important revenue source. Although occupations may also be taxed, no county implements that provision. Each year the commissioners court sets the county tax rate. If property tax rate increases exceed an amount that would generate up to 8 percent more than the previous year's revenues, citizens may circulate a petition for an election to roll back (limit) the higher rate. (The other local governments face similar limitations.) Counties may also add 0.5 to 1.5 cents onto the state sales tax, which is 6.25 cents on the dollar. (Remember, however, that the add-on by all local governments may not exceed 2 cents.) Fewer than half of Texas counties (primarily those with relatively small populations) impose a sales tax, and most set the rate at 0.5 cents.

Revenues From Nontax Sources

Counties receive small amounts of money from various sources that add up to an important part of their total revenue. All counties may impose fees on the sale of liquor, and they share in state revenue from liquor sales, various motor vehicle taxes and fees, and traffic fines. Like other local governments, counties are eligible for federal grants-in-aid; but over the long term, this source continues to shrink. With voter approval, a county may borrow money through sale of bonds to pay for capital projects such as a new jail or sports stadium. The Texas Constitution limits county indebtedness to 35 percent of a county's total assessed property value.

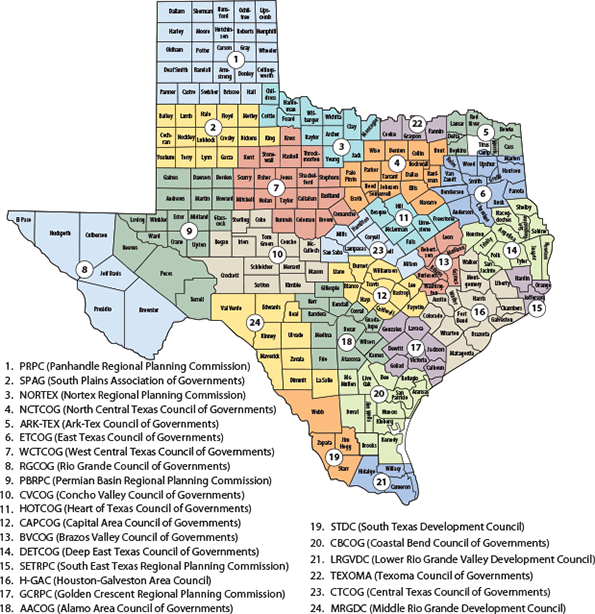

Tax Incentives and Subsidies