the text book Practicing Texas Politics Texas Edition (16th Edition), Brown, et.al. for this assignment: 3,4,5,6,10,13.

Chapter5

Campaigns and Elections

Chapter Introduction

5-1 Political Campaigns

5-1a Conducting Campaigns in the 21st Century

5-1b Campaign Reform

5-1c Campaign Finance

5-2 Racial and Ethnic Politics

5-2a Latinos

5-2b African Americans

5-3 Women in Politics

5-4 Voting

5-4a Obstacles to Voting

5-4b Democratization of the Ballot

5-4c Voter Turnout

5-4d Administering Elections

5-5 Primary, General, and Special Elections

5-5a Primaries

5-5b General and Special Elections

5-6 Chapter Review

5-6aConclusion

5-6bChapter Summary

5-6cKey Terms

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections Chapter Introduction

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

Chapter Introduction

Nick Anderson Editorial Cartoon used with the permission of Nick Anderson, the Washington Post Writers Group and the Cartoonist Group. All rights reserved.

Critical Thinking

How might a voter be considered the most powerful person in the free world?

Learning Objectives

5.1 Analyze the components of a political campaign, specifically how the process of running and financing a campaign has changed over the years.

5.2 Describe the role that race and ethnicity play in politics, focusing on the importance of minority voters.

5.3 Describe the role that women have played in Texas politics and how that role has evolved.

5.4 Explain the complexities of voting and how the voting process promotes, and inhibits, voter participation.

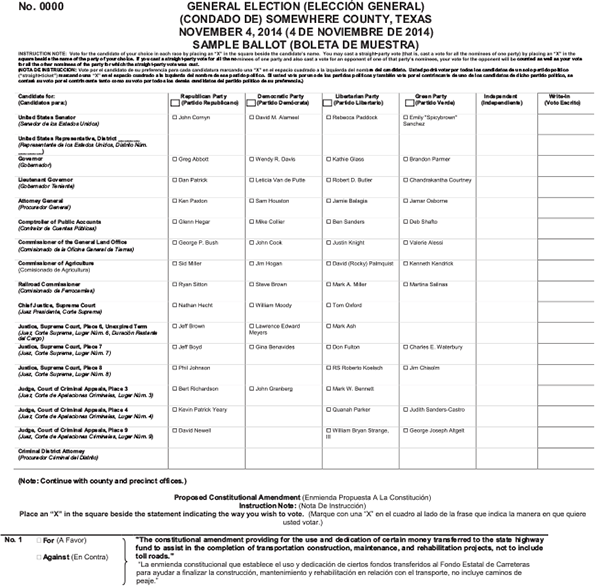

5.5 Identify the differences among primary, general, and special elections.

The fundamental principle on which every representative democracy is based is citizen participation in the political process. As Nick Anderson's cartoon depicts, voters are considered to be the most powerful people in the free world. Yet in Texas, even as the right to vote was extended to almost every citizen 18 years of age or older, participation declined throughout the 20th century's final decades and into the 21st century. This chapter focuses on campaigns and the role that media and money play in our electoral system. Citizen participation through elections and the impact of that participation are additional subjects of our study.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-1 Political Campaigns

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-1 Political Campaigns

LO 5.1

Analyze the components of a political campaign, specifically how the process of running and financing a campaign has changed over the years.

Elections in Texas allow voters to choose officials to fill national, state, county, city, and special district offices. With so many electoral contests, citizens are frequently besieged by candidates seeking votes and asking for money to finance election campaigns. The democratic election process, however, gives Texans an opportunity to influence public policymaking by expressing preferences for candidates and issues when they vote.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-1a Conducting Campaigns in the 21st Century

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-1a Conducting Campaigns in the 21st Century

Campaigns are no longer limited to speeches by candidates on a courthouse lawn or from the rear platform of a campaign train. Today, prospective voters are more likely to be harried by a barrage of campaign publicity involving television and radio broadcasting, targeted emails designed to encourage likely supporters to vote and give money, yard signs, bumper stickers, newspapers, and billboards. Moreover, voters will probably receive campaign information by electronic mail, be solicited for donations to pay for campaign expenses, encounter door-to-door canvassers, receive political information in the U.S. mail, receive requests to post candidate “likes” on Facebook pages and other social media sites, and be asked to answer telephone inquiries from professional pollsters or locally hired telephone bank callers. In recent years, the Internet and the array of available social media tools have altered political campaigns in Texas and other states. Politicians set up Facebook pages inviting voters to friend them. Other campaigners “tweet” their supporters on Twitter to announce important events and decisions. To the dismay of some politicians, YouTube videos provide a permanent record of misstatements and misdeeds. Private and public lives of candidates remain open 24/7 for review and comment.

Despite increasing technological access to information about candidates and issues, a minority of Texans, and indeed other Americans, are actively concerned with politics. To most voters, character and political style have become more important than issues. A candidate's physical appearance and personality are increasingly important because television has become a primary mode of campaign communication.

Importance of the Media

Since the days of W. Lee “Pappy” O'Daniel, the media have played an important role in Texas politics. In the 1930s, O'Daniel gained fame as a radio host for Light Crust Flour and later his own Hillbilly Flour Company. On his weekly broadcast show, the slogan “Pass the biscuits, Pappy” made O'Daniel a household name throughout the state. In 1938, urged by his radio fans, O'Daniel ran for governor and attracted huge crowds. With a platform featuring the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule, he won the election by a landslide. In an attempt to duplicate O'Daniel's feat, Kinky Friedman (a singer, author, and humorist with a cult following) ran unsuccessfully as an independent candidateA candidate who runs in a general election without party endorsement or selection. for governor in 2006, using TV appearances the way O'Daniel used the radio. In 2014, Friedman ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for agriculture commissioner.

By the 1970s, television and radio ads had become a regular part of every gubernatorial and U.S. senatorial candidate's campaign budget. Radio became the medium of choice for many “middle-of-the-ballot” (statewide and regional candidates for offices other than governor or senator) and local candidates. The prohibitive cost of television time, with the exception of smaller media markets and local cable providers, forced the use of radio to communicate with large numbers of potential voters. Today, with more than 13 million potential voters in 254 counties, Texas is, by necessity, a media state for political campaigning. To visit every county personally during a primary campaign, a candidate would need to go into four counties per day, five days a week, from the filing deadline in January to the March primary (the usual month for party primaries). Such extensive travel would leave little time for speechmaking, fundraising, and other campaign activities. Although some candidates for statewide office in recent years have traveled to each county in the state, none has won an election. Therefore, Texas campaigners must rely more heavily on television, radio, and social media exposure than do candidates in other states.

Most Texas voters learn about candidates through television commercials that range in length from 10 seconds for a sound biteA brief statement of a candidate's theme communicated by radio or television in a few seconds. (a brief statement of a candidate's campaign theme) to a full minute. Television advertisements allow candidates to structure their messages carefully and avoid the risk of a possible misstatement that might occur in a political debate. Therefore, the more money a candidate's campaign has, the less interest the candidate has in debating an opponent. Usually, the candidate who is the underdog (the one who is behind in the polls) wants to debate.

Candidates also rely increasingly on social media to communicate with voters. The benefit of low cost must be balanced against problems unique to the medium of websites and email. Issues with using social media include limited use and understanding of this type of media by the older (over 65) voting population. Additional complexities include access to and use of computers by older voters, consumer resistance to “spam” (electronic junk mail), hyperlinks to inappropriate websites, and “cybersquatting” (individuals other than the candidate purchasing domain names similar to the candidate's name and then selling the domain name to the highest bidder). In his 2010 general election campaign, Jim Prindle, a Libertarian, purchased rights to RalphHall.org in his bid to defeat U.S. Representative Ralph Hall (R-Rockwall). This site rerouted viewers to Prindle's campaign site. Although he was unsuccessful in his bid to unseat the 15-term incumbent, Prindle said that he had “explored many strategies in marketing and campaigning to help bridge the advantage that incumbents share.” Hall failed to win the GOP nomination for a 17th term in 2014.

Mudslide Campaigns

Following gubernatorial candidate Ann Richards's victory over Jim Mattox in the Democratic runoff primary of April 1990, one journalist reported that Richards had “won by a mudslide.” This expression suggests the reaction of many citizens who were disappointed, if not infuriated, by the candidates' generally low ethical level of campaigning and by their avoidance of critical public issues. Nevertheless, as character became more important as a voting consideration in the 1990s and early 21st century, negative campaigning has become even more prominent.

The 2014 gubernatorial election was particularly acrimonious. In an ad titled “Justice,” Democratic gubernatorial nominee Wendy Davis's campaign attempted to demonstrate how Republican gubernatorial nominee Greg Abbott was a hypocrite as both a judge and as attorney general by restricting victims' access to the courts despite his award of over $10 million in 1984 after a tree fell on him and left him paralyzed. The ad showed an empty wheelchair with a narrator saying, “A tree fell on Greg Abbott. He sued and got millions. Since then, he's spent his career working against other victims. Abbott argued a woman whose leg was amputated was not disabled because she had an artificial limb. He ruled against a rape victim who sued a corporation for failing to do a background check on a sexual predator. He sided with a hospital that failed to stop a dangerous surgeon who paralyzed patients. Greg Abbott, he's not for you.” Several conservative commentators criticized the ad, and a representative from Abbott's campaign called it “disgusting.” In a press release issued by Greg Abbott's campaign, titled, “Sen. Davis Has A Lot To Answer For,” Abbot claimed that Davis once raised money for a U.S. House Democrat who is a member of a Democratic socialists group. This statement earned a “Pants on Fire” rating from the Austin American Statesmen's PolitiFact Truth-O-Meter as unconfirmed and ridiculous.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-1b Campaign Reform

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-1b Campaign Reform

Concern over the shortcomings of American election campaigns has given rise to organized efforts toward improvement at all levels of government. Reformers range from single citizens to members of the U.S. Congress and large lobby groups. Reform issues include eliminating negative campaigning, increasing free media access for candidates, and regulating campaign finance.

Eliminating Negative Campaigning

Almost 25 years ago, the Markle Commission on the Media and the Electorate concluded that candidates, the media, consultants, and the electorate were all blameworthy for the increase in negative campaigns. Candidates and consultants, wishing to win at any cost, employ negative advertising and make exaggerated claims. The media emphasize poll results and the horserace appearance of a contest, rather than basic issues and candidate personalities that relate to leadership potential. In 2010, another study tested the effectiveness of “comparative” ads run during the Texas governor's race to see if they persuaded voters. Research findings showed that negative commercials influenced voters (especially undecided voters), drawing their preference away from the candidate being attacked.

The 2014 Republican runoff primary for lieutenant governor featured several negative commercials and other attacks between the incumbent lieutenant governor, David Dewhurst, and his opponent and eventual nominee, state senator Dan Patrick. One Dewhurst commercial showed a shirtless Dan Patrick and claimed that Patrick was caught pocketing employees' federal income tax withholdings, not paying his taxes 28 times, hiding assets from creditors and sticking them with $800,000, knowingly employing illegal immigrants, and changing his name from Dannie Goeb to Dan Patrick. A Patrick ad claimed that under Dewhurst's leadership, the Texas Senate passed an expansion of in-state tuition and free health care to illegal immigrants, and that Dewhurst's record was more taxpayer-funded benefits for illegal immigrants.

Increasing Free Media Access

Certainly a candidate for statewide office in Texas cannot win without first communicating with a large percentage of the state's voting population. As noted previously, television is the most important, and the most expensive, communication tool. One group supporting media access reform is the Campaign Legal Center. Although initially they sought to increase requirements for broadcasters to make the air waves more available at no cost to political candidates, more recent efforts have focused on campaign finance reform. As long as paid media advertising is a necessary part of political campaigns and media outlets generate a significant source of revenue from political campaigns, fundraising will remain important to electoral success.

By the early 21st century, many political campaigns used social networking resources to get their message out to a larger voter base. Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube became commonly used tools for candidates to reach potential voters. In 2008, Barack Obama used cell phone text messaging as one means of announcing his vice presidential selection (U.S. Senator Joe Biden). That year, Obama also became the first presidential candidate to provide a free iPhone application (Obama ’08). Users could get current updates about the campaign and network with other users. Relaying campaign information by phone also provided the Obama campaign with millions of cell phone numbers. These strategies became common practice in both the Obama and Romney presidential campaigns in 2012. This shift, however, was not limited to presidential campaigns.

In 2014, most candidates for statewide office in Texas regularly used social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, LinkedIn, YouTube, Vimeo, and Pinterest to reach potential voters and provide forums for comment and feedback. Because of the open nature of these media and the ability of the public to post comments, campaigns often set strict guidelines for posting comments on candidates' social media sites. However, such guidelines do not always prevent inappropriate comments from appearing or prevent candidates from becoming involved in controversies that arise from such comments. In late 2013, the eventual Republican gubernatorial nominee, Greg Abbott, was criticized for the following exchange:

“@GregAbbott_TX would absolutely demolish idiot @WendyDavisTexas in Gov race – run Wendy run! Retard Barbie to learn life lesson. #TGDN @tcot”

—Jeff Rutledge (@jefflegal) August 17, 2013

“Jeff, thanks for your support.”

—Greg Abbott (@GregAbbott_TX) August 17, 2013

After the post went viral and Democratic party leaders labeled Abbott insensitive and disrespectful of women, the gubernatorial candidate tweeted that he did “not endorse anyone's offensive language.”

(For a detailed discussion about the 2014 gubernatorial candidates' use of social media, as well as challenges they encountered with inappropriate postings on their websites, see this chapter's Selected Reading, “Campaigns Contend with Vitriol on Social Media.”)

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-1c Campaign Finance

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-1c Campaign Finance

On more than one occasion, President Lyndon Johnson bluntly summarized the relationship between politics and finance: “Money makes the mare go.” Although most political scientists would state this fact differently, it is obvious that candidates need money to pay the expenses of election campaigns. Texas's 1990 gubernatorial campaign established a record of $45 million spent on the primary and general election races combined, including more than $22 million by Midland oilman Clayton Williams. He narrowly lost to Ann Richards, who spent $12 million. The 1990 record, however, was shattered by the 2002 gubernatorial election, in which Tony Sanchez's and Rick Perry's campaigns spent a combined record of more than $95 million. Sanchez outspent Perry by more than two to one ($67 million to $28 million) in the race for governor. Despite his big spending, however, Sanchez lost by 20 percent. Even though $95 million set a new record for spending in a Texas race, it ranks as only the fifth most expensive gubernatorial race. California's 2010 gubernatorial contest, which cost an estimated $250 million, ranks first, followed by New York's gubernatorial race in 2002 ($148 million) and California's gubernatorial races in 1998 ($130 million) and 2002 ($110 million).

Many Texans are qualified to hold public office, but relatively few can afford to pay their own campaign expenses (as gubernatorial candidates Clayton Williams and Tony Sanchez and lieutenant gubernatorial candidate David Dewhurst did). Others are unwilling to undertake fundraising drives designed to attract significant campaign contributions.

Candidates need to raise large amounts of cash at local, state, and national levels. Successful Houston City Council candidates often require from $150,000 (for district races) to $250,000 (for at-large races), and mayoral candidates may need $2 million or more. In 2003, Houston businessman Bill White spent a record $8.6 million on his mayoral election, including $2.2 million of his own money. Some individuals and political action committees (PACs)An organizational device used by corporations, labor unions, and other organizations to raise money for campaign contributions. which are organizations created to collect and distribute contributions to political campaigns, donate because they agree with a candidate's position on the issues. The motivations of others, however, may be questionable. In return for their contributions, big donors receive access to elected officials. Many politicians and contributors assert that access does not mean that donors gain control of officials' policymaking decisions. Yet others, such as former Texas House Speaker Pete Laney, attribute the decline in voter participation to a growing sense that average citizens have no voice in the political process because they cannot afford to make large financial donations to candidates.

Both federal and state laws have been enacted to regulate various aspects of campaign financing. Texas laws on the subject, however, are relatively weak and tend to emphasize reporting of contributions with few limits on the amounts of the donations. Federal laws are more restrictive, featuring both reporting requirements and limits on contributions to a candidate's political campaign by individuals and PACs. In 1989, chicken magnate Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim handed out $10,000 checks on the Texas Senate floor, leaving the “payable to” lines blank, as legislators debated reforming the state's workers' compensation laws. Many were surprised to find that Texas had no laws at that time prohibiting such an action. Two years later, the Texas legislature passed laws prohibiting political contributions to members of the legislature while they are in session; and in 1993 Texas voters approved a constitutional amendment establishing the Texas Ethics CommissionA state agency that enforces state standards for lobbyists and public officials, including registration of lobbyists and reporting of political campaign contributions.. Among its constitutional duties, this commission requires financial disclosure from public officials. Unlike the Federal Election Campaign Act, however, Texas has no laws that limit political contributions.

Further restricting the amount of money that can be contributed to campaigns is another area of possible reform. However, success in this area has been fairly limited. In 2002, the U.S. Congress passed the long-awaited Campaign Reform ActEnacted by the U.S. Congress and signed by President George W. Bush in 2002, this law restricts donations of “soft money” and “hard money” for election campaigns, but its effect has been limited by federal court decisions., signed into law by President Bush. This federal law prohibited soft moneyUnregulated political donations made to national political parties or independent expenditures on behalf of a candidate.; increased the limits on individual hard moneyCampaign money donated directly to candidates or political parties and restricted in amount by federal law. (or direct) contributions; and restricted corporations' and labor unions' ability to run “electioneering” ads that feature the names or likenesses of candidates close to Election Day.

Plaintiffs, including former Texas Congressman Ron Paul (R-Clute) and others, challenged the constitutionality of this act, claiming it was an unconstitutional restraint on freedom of speech. In a sharply divided decision, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the “soft money” ban in McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93 (2003). Seven years later, however, in a 5–4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 50 (2010), overturned a provision of the act that banned unlimited independent expendituresExpenditures that pay for political campaign communications that expressly advocate the nomination, election, or defeat of a clearly identified candidate but are not given to, or made at the request of, the candidate's campaign. made by corporations, unions, and nonprofit organizations in federal elections. This decision was widely criticized by Democrats and by some members of the Republican Party as judicial activism that would give corporations and unions unlimited power in federal elections. In his 2010 State of the Union address, President Obama admonished the Supreme Court, stating, “Last week, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law to open the floodgates for special interests, including foreign corporations, to spend without limit in our elections. Well, I don't think American elections should be bankrolled by America's most powerful interests, or worse, by foreign entities.”

That same year, a nine-judge federal appeals court unanimously ruled in SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, 599 F. 3rd 686 (2010), that campaign contribution limits on independent organizations using the funds only for independent expenditures are unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear this case on appeal, letting the lower court's decision stand. Decisions in these cases led to creation of super PACsIndependent expenditure–only committees that may raise unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, nonprofit organizations, and individuals., which are independent expenditure–only committees that may raise unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, nonprofit organizations, and individuals. Super PACs are then able to spend unlimited sums to openly support or oppose political candidates. By 2012, super PACs had been in existence for less than two years; but 1,310 of these PACs reported having raised more than $828 million and having spent more than $609 million on the 2012 presidential candidates. Some of the better-known, better-funded super PACs of the 2012 presidential election included “Priorities USA Action” (supporting Barack Obama), “Restore Our Future” (supporting Mitt Romney), “American Crossroads” (headed by Republican strategist Karl Rove), and “Make Us Great Again” (supporting Rick Perry). Founded by Perry's former chief of staff, Mike Toomey, “Make Us Great Again” contributors included Dallas businessman Harold Simmons, Dallas tax consultant Brint Ryan, Houston attorney Tony Buzbee, Dallas energy executive Kelcy Warren, and Midland energy executive Javaid Anwar. “Make Us Great Again” spent approximately $4 million on Perry's behalf. In a parody of campaign finance rules, comedian Stephen Colbert formed his own super PAC—“Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow,” also known as “Stephen Colbert's Super PAC.” By mid-2014, there were more than 1,000 organized super PACs.

Although the Citizens United decision removed limits on how much money can be given to or spent by outside groups on behalf of federal candidates, it did not address limits on campaign contributions to candidates or committees by individual donors. In another sharply divided decision, the U.S. Supreme Court in McCutcheon v. FEC, 572 U.S. ___ (2014), struck down the aggregate limits on the amount an individual may contribute during a two-year period to all federal candidates, parties, and political action committees combined. By a vote of 5–4, the Court ruled that the aggregate limit an individual could donate to candidates for federal office, political parties, and political action committees per election per cycle ($117,000, including a limit of $46,200, in 2012, although amounts are adjusted annually for inflation) was unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The amount that can be donated to a specific candidate, political party, or PAC is limited, however. As with the Citizens United decision, several groups criticized this ruling as a further erosion of protections against undue influence in elections by a small portion of the electorate. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, only 591 donors out of an estimated 310 million Americans (approximately .0000019 percent of the population) gave the maximum of $46,200 to federal candidates during the 2012 election cycle.

Texas's state campaign finance laws have focused on making contributor information more easily available to citizens. Restrictions on the amount of donations apply only to some judicial candidates. Treasurers of campaign committees and candidates are required to file periodically with the Texas Ethics Commission. With limited exceptions, these reports must be filed electronically. Sworn statements list all contributions received and expenditures made during designated reporting intervals. Candidates who fail to file these reports are subject to a fine.

In 2003, the Texas legislature passed a law requiring officials of cities with a population of more than 100,000 and trustees of school districts with enrollments of 5,000 or more to disclose the sources of their income, as well as the value of their stocks and their real estate holdings. In addition, candidates for state political offices must identify employers and occupations of people contributing $500 or more to their campaigns and publicly report “cash on hand.” The measure also prohibits state legislators from lobbying for clients before state agencies.

Recent court decisions and loopholes in disclosure laws have opened the door for “dark money,” money spent on elections by anonymous donors. In 2013, a bill passed by the Texas Legislature that would have required nonprofit organizations that spend $25,000 or more on political campaigns to publicly disclose contributors who donate more than $1,000 was vetoed by Governor Perry. One conservative dark money group, “Empower Texans,” filed a federal lawsuit in 2014 to prevent the Texas Ethics Commission from compelling them to disclose their list of donors, asserting a right to keep donors' names confidential.

Learning Check 5.1

True or False: Most Texas voters learn about candidates through newspaper editorials.

Which state commission requires financial disclosure from public officials?

Federal and state campaign finance laws have largely failed to cope with buying influence through transfers of money in the form of campaign contributions. It may well be that as long as campaigns are funded by private sources, they will remain inadequately regulated.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-2 Racial and Ethnic Politics

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-2 Racial and Ethnic Politics

LO 5.2

Describe the role that race and ethnicity play in politics, focusing on the importance of minority voters.

Racial and ethnic factors are strong influences on Texas politics, and they shape political campaigns. Slightly more than half of Texas's total population is composed of Latinos (chiefly Mexican Americans) and African Americans, making Texas a majority-minority state. Politically, the state's historical ethnic and racial minorities wield enough voting strength to decide any statewide election and determine the outcomes of local contests in areas where their numbers are concentrated. Large majorities of Texas's African American and Latino voters participate in Democratic primaries and vote for Democratic candidates in general elections. However, increasing numbers of African Americans and Latinos claim to be politically independent and do not identify with either the Republican or the Democratic party.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-2a Latinos

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-2a Latinos

Early in the 21st century, candidates for elective office in Texas, and most other parts of the United States, recognized the potential of the Latino vote. Most Anglo candidates use Spanish phrases in their speeches, advertise in Spanish-language media (television, radio, and newspapers), and voice their concern for issues important to the Latino community (such as bilingual education and immigration). In each presidential election since 2000, candidates from both major political parties included appearances in Latino communities and before national Latino organizations, such as the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the National Council of La Raza, as a part of their campaign strategy. Such appearances recognize the political clout of Latinos in the Republican and Democratic presidential primaries, as well as in the general election.

Although Mexican Americans played an important role in South Texas politics throughout the 20th century, not until the 1960s and early 1970s did they begin to have a major political impact at the state level. A central turning point was during the late 1960s with the creation of a third-party movement, La Raza Unida Party. Founded in 1969 by José Ángel Gutiérrez of Crystal City and others, La Raza Unida fielded numerous candidates at the local and state levels and mobilized many Mexican Americans who had been politically inactive. It also attracted others who had identified with the Democratic Party but who had grown weary of the party's unresponsiveness to the needs and concerns of the Mexican American community. By the end of the 1970s, however, Raza Unida had disintegrated. According to Ruben Bonilla, former president of LULAC, the main reason Raza Unida did not survive as a meaningful voice for Texas's Mexican American population was “the maturity of the Democratic Party to accept Hispanics.”

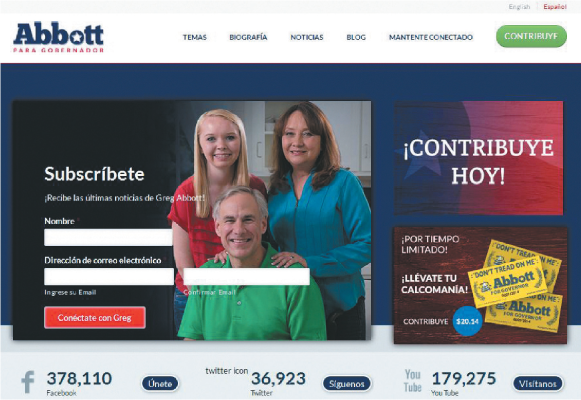

In the 1980s, Mexican American election strategy became more sophisticated as a new generation of college-educated Latinos sought public office and assumed leadership roles in political organizations. Although Latinos are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, Republican candidates such as George W. Bush have succeeded in winning the support of many Latino voters, and Republican candidates fare better among Latino voters in Texas than they do nationally. Successful GOP candidates emphasize family issues and target heavily Latino areas for campaign appearances and media advertising. Gubernatorial candidate Greg Abbott's first post-primary ad in 2014 was in Spanish and featured his sister-in-law explaining to other Latinos that Abbott shared their values and beliefs. Coincidentally, the ad highlighted that his wife, Cecilia, would be the first Latina First Lady in Texas history.

In 2003, Governor Perry appointed Victor Carrillo to the Texas Railroad Commission. When Carrillo lost his bid for reelection in the 2010 Republican primary, he blamed his defeat by an unknown and underfinanced candidate on his Hispanic surname and its inability to attract support among Republican voters. Governor Perry also appointed two Latino secretaries of state (Henry Cuellar in 2001 and Esperanza “Hope” Andrade in 2008), one Texas Supreme Court justice (Eva Guzman in 2009), and one judge to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (Elsa Alcala in 2011). In 2010, Justice Guzman became the first Latina to win a statewide election.

Many members of the Democratic Party believe it is important to have Latino nominees for high-level statewide offices in order to attract Latino voters to the polls. They argue that because the majority of Latinos are more likely to support Democratic candidates, a higher voter turnout will elect more Democrats to office. Focusing on registering and turning out voters among the increasing Latino population, Democratic strategists hope to turn Texas into a Democratic stronghold again (see Chapter 4 Selected Reading, “What Must Happen for Texas to Turn Blue”).

In 2002, Laredo businessman Tony Sanchez Jr. became the first Latino candidate nominated for governor by a major party in Texas. Challenged for the Democratic nomination by former Texas attorney general Dan Morales, on March 1, 2002, the two men held the first Spanish-language gubernatorial campaign debate in U.S. history. Underscoring its strategy to attract more Latino voters, in 2012 the Democratic Party selected the first Latino chair of a major political party in Texas when it chose Gilberto Hinojosa to be its state chair. In 2014, Latino candidates for statewide office included the Democratic nominee for lieutenant governor, Leticia Van De Putte, and the Republican nominee for commissioner of the general land office, George P. Bush (son of former Florida governor Jeb Bush and his Latina wife, nephew of former Texas governor and president George W. Bush, and grandson of former president George H. W. Bush).

By early 2015, a substantial number of Latinos held elected office, including the following:

Three statewide positions (commissioner of the general land office, one supreme court justice, and one judge on the Court of Criminal Appeals)

One U.S. senator

Five U.S. representative seats in Texas's congressional delegation

42 legislative seats in the Texas legislature

More than 2,100 of the remaining 5,200 elected positions in the state

Among the many issues, such as bilingual education and political representation, affecting the Latino community, none is more relevant than immigration reform. The Latino community's political impact was clear in the debate over immigration laws, when millions of Latinos in Texas took part in demonstrations or boycotts in early 2006. In addition, in 2010, an estimated 28,000 people participated in a demonstration in Dallas protesting Arizona's immigration law that gave law enforcement broad authority to inquire about immigration status. A similar bill was defeated in the Texas legislature in 2011. Another piece of legislation, however, that would require people to prove U.S. citizenship or legal residence before they can get or renew a Texas driver's license passed and took effect in 2011. In 2014, Governor Perry ordered 1,000 National Guard troops to the Texas-Mexico Border to limit illegal immigration. As the Latino population continues to grow, the immigration issue will in large part determine many Latinos’ party support.

Unlike in the past, Democratic candidates can no longer assume they have Latino voter support in statewide electoral contests. Latinos' voting behavior indicates that they respond to candidates and issues, not to a particular political party. Further divisions occur between socioeconomic levels, with Hispanics who earn more than $50,000 per year more likely to support Republican candidates than Hispanics with annual incomes of less than $50,000. Although both national and state Republican Party platforms discourage bilingual education and urge stricter immigration controls, Republican candidates frequently do not endorse these positions. Often, successful Republican candidates actually distance themselves from their party, especially in the Latino community. For instance, during a Republican presidential candidate debate in 2011, Governor Perry drew criticism from his opponents by defending his support for a state law that allows some undocumented students who graduate from a high school in Texas and are working toward legal status to qualify for in-state tuition at Texas public colleges and universities.

In 2012, the Republican National Committee launched the Growth and Opportunity Project, with a list of recommendations and strategies designed to expand the base of the party and win more elections. Among its recommendations, this report encouraged the Republican Party to focus its messaging, strategy, outreach, and budget efforts to gain new supporters and voters in the Hispanic community (as well as in other racial/demographic communities including Pacific Islanders, African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, women, and youth). In 2013, in an effort to garner greater support among Latinos, a “figurative memo” (informal agreement) went out to all Texas Republican lawmakers urging them not to introduce bills that would embarrass the party with Latino voters.

In an effort to win support among Latino voters, 2014 Republican gubernatorial nominee Greg Abbott launched a website in Spanish.

Source: www.gregabbott.com

Critical Thinking

How might developing a website in Spanish win support among Latino voters?

The sheer size of the Latino population causes politicians to solicit their support because Latino voters can represent the margin of victory for a successful candidate. Lower levels of political activity than the population at large, however, both in registering to vote and in voting, limit an even greater impact of the Latino electorate.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-2b African Americans

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-2b African Americans

In April 1990, the Texas State Democratic Executive Committee filled a candidate vacancy by nominating Potter County court-at-law judge Morris Overstreet, an African American Democrat, for a seat on the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. Because the Republican candidate, Louis Sturns, was also African American, this historic action guaranteed the state's voters would elect the first African American to statewide office in Texas. Overstreet won in 1990 and again in 1994. He served until 1998, when he ran unsuccessfully for Texas attorney general. Governor George W. Bush appointed Republican Michael Williams to the Texas Railroad Commission in 1999. This African American commissioner was elected to a six-year term in 2002 and again in 2008. Williams stepped down from the Texas Railroad Commission in 2011 to make an unsuccessful run for Congress, but in August 2012 he was appointed by Governor Perry as commissioner of education.

The appointment of Justice Wallace Bernard Jefferson to the Texas Supreme Court in 2001 made him the first African American to serve on the court. He and another African American, Dale Wainwright, were elected to that court in 2002 and again in 2008. Jefferson again made history in 2004 when Governor Perry appointed him as chief justice. Both Jefferson and Wainwright resigned their respective offices in 2013. Two Anglo male justices replaced them on the court. In 2002, former Dallas mayor Ron Kirk became the first African American nominated by either major party in Texas as its candidate for U.S. senator. Although unsuccessful in the general election, Kirk's candidacy appeared to many political observers as an important breakthrough for African American politicians. Kirk later was appointed U.S. Trade Representative by President Barack Obama and in 2013 resigned to join a Dallas law firm. In 2014, no African Americans from either party were candidates for statewide office.

Learning Check 5.2

Which party have Latinos traditionally supported?

True or False: In 2014, no African Americans were holding statewide elected office.

Since the 1930s, African American Texans have tended to identify with the Democratic Party. With a voting-age population in excess of 1 million, they constitute roughly 10 percent of the state's potential voters. As demonstrated in recent electoral contests, approximately 80 percent of Texas's African American citizens say they are Democrats, and only 5 percent are declared Republicans. The remainder are independents. In recent years, African American support for the Democratic Party and its candidates has declined slightly. By early 2015, a number of African Americans held elected office, including the following:

Five U.S. representative seats in Texas's congressional delegation

19 seats in the Texas legislature

More than 500 of the remaining 5,200 elected positions in the state

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-3 Women in Politics

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-3 Women in Politics

LO 5.3

Describe the role that women have played in Texas politics and how that role has evolved.

Texas women did not begin to vote and hold public office for three-quarters of a century after Texas joined the Union. Until 1990, only four women had won a statewide office in Texas, including two-term governor Miriam A. (“Ma”) Ferguson (1925–1927 and 1933–1935). Ferguson owed her office to supporters of her husband, Jim, who had been impeached and removed from the governorship in 1917. Nevertheless, in 1990, Texas female voters outnumbered male voters, and Ann Richards was elected governor. After 1990, the number of women elected to statewide office increased dramatically.

In the early 1990s, Texas women served as mayors in about 150 of the state's towns and cities, including the top four in terms of population (Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and El Paso). Mayor of Dallas Annette Strauss (1988–1991) was fond of greeting out-of-state visitors with this message: “Welcome to Texas, where men are men and women are mayors.”

In 2010, when Annise Parker was sworn in as mayor of Houston, she made history as the first openly gay mayor of a major U.S. city. Although Parker had been open about her sexual orientation during her previous elections as the city's comptroller and, before that, as a city council member, her November 2009 election as mayor of the nation's fourth-largest city received national media attention. The impact of women's voting power was also evident in several elections early in the 21st century, when women (U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison and state comptroller Carole Keeton Rylander) led all candidates on either ticket in votes received. In 2013, Governor Perry appointed Indian American Nandita Berry the 109th Texas secretary of state. The Democratic primary election results in 2014 marked the first election in which female candidates held the top two positions on a party's ticket in Texas. The Democratic Party nominated Wendy Davis for governor and Leticia Van De Putte for lieutenant governor. Republicans had no female nominees for statewide office in 2014.

Female candidates also succeeded in winning an increasing number of seats in legislative bodies. In 1971, no women served in Texas's congressional delegation, and only two served in the Texas legislature. As a result of the 2014 election, in 2015 the number of women in Texas's congressional delegation was 3. The number of women in the Texas legislature was 37 (7 in the Senate and 30 in the House of Representatives), a decline from the 44 women who served in the 81st legislature (2009). The expanded presence of women in public office is changing public policy. For example, increased punishment for family violence and sexual abuse of children, together with a renewed focus on public education, can be attributed in large part to the presence of women in policymaking positions.

Learning Check 5.3

True or False: Women candidates received the most votes for a single office in some elections early in the 21st century.

By 2015, how many women had served as governor of Texas?

Despite their electoral victories in Texas and elsewhere across the nation, fewer women than men seek elective public office. Several reasons account for this situation, chief of which is difficulty in raising money to pay campaign expenses. Other reasons also discourage women from seeking public office. Although women enjoy increasing freedom, they still shoulder more responsibilities for family and home than men do (even in two-career families). Some mothers feel obliged to care for children in the home until their children finish high school. Such parental obligations, together with age-old prejudices, deny women their rightful place in government. Yet as customs, habits, and attitudes change, new opportunities for women in public service are expanding.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-4 Voting

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-4 Voting

LO 5.4

Explain the complexities of voting and how the voting process promotes, and inhibits, voter participation.

The U.S. Supreme Court has declared the right to vote the “preservative” of all other rights. For most Texans, voting is their principal political activity. For many, it is their only exercise in practicing Texas politics. Casting a ballot brings individuals and their government together for a moment and reminds people anew that they are part of a political system.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-4a Obstacles to Voting

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-4a Obstacles to Voting

The right to vote has not always been as widespread in the United States as it is today. Universal suffrageVoting is open for virtually all persons 18 years of age or older., by which almost all citizens 18 years of age and older can vote, did not become a reality in Texas until the mid-1960s. Although most devices to prevent people from voting have been abolished, their legacy remains.

Adopted after the Civil War (1861–1865), the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution were intended to prevent denial of the right to vote based on race. But for the next 100 years, African American citizens in Texas and other states of the former Confederacy, as well as many Latinos, were prevented from voting by one barrier after another—legal or otherwise. For example, the white-robed Ku Klux Klan and other lawless groups used terrorist tactics to keep African Americans from voting. Northeast Texas was the focus of the Klan's operations in the Lone Star State.

Literacy Tests

Beginning in the 1870s, as a means to prevent minority people from voting, some southern states (although not Texas) began requiring prospective voters to take a screening test that conditioned voter registrationA qualified voter must register with the county voting registrar, who compiles lists of qualified voters residing in each voting precinct. on a person's literacy. Individuals who could not pass these literacy testsAlthough not used in Texas as a prerequisite for voter registration, the test was designed and administered in ways intended to prevent African Americans and Latinos from voting. were prohibited from registering. Some states used constitutional interpretation or citizenship knowledge tests to deny voting rights. These tests usually consisted of difficult and abstract questions concerning a person's knowledge of the U.S. Constitution or understanding of issues supposedly related to citizenship. In no way, however, did these questions measure a citizen's ability to cast an informed vote. The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 made literacy tests illegal.

Grandfather Clause

Another device, not used in Texas but enacted by other southern states to deny suffrage to minorities, was the grandfather clauseAlthough not used in Texas, the law exempted people from educational, property, or tax requirements for voting if they were qualified to vote before 1867 or were descendents of such persons.. Laws with this clause provided that persons who could exercise the right to vote before 1867, or their descendants, would be exempt from educational, property, or tax requirements for voting. Because African Americans had not been allowed to vote before adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, grandfather clauses were used along with literacy tests to prevent African Americans from voting while assuring this right to many impoverished and illiterate whites. The U.S. Supreme Court, in Guinn v. United States (1915), declared the grandfather clause unconstitutional because it violated the equal voting rights guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment.

Poll Tax

Beginning in 1902, Texas required that citizens pay a special tax, called the poll taxA tax levied in Texas from 1902 until voters amended the Texas Constitution in 1966 to eliminate it; failure to pay the annual tax (usually $1.75) made a citizen ineligible to vote in party primaries or in special and general elections., to become eligible to vote. The cost was $1.75 ($1.50, plus $0.25 that was optional with each county). For the next 64 years, many Texans—especially low-income persons, including disproportionately large numbers of African Americans and Mexican Americans—failed to pay their poll tax during the designated four-month period from October 1 to January 31. This failure, in turn, disqualified them from voting during the following 12 months in party primaries and in any general or special election. As a result, African American voter participation declined from approximately 100,000 in the 1890s to about 5,000 in 1906. With ratification of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in January 1964, the poll tax was abolished as a prerequisite for voting in national elections. Then, in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966), the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated all state laws that made payment of a poll tax a prerequisite for voting in state elections.

All-White Primaries

The so-called white primaryA nominating system designed to prevent African Americans and some Latinos from participating in Democratic primaries from 1923 to 1944., a product of political and legal maneuvering within the southern states, was designed to deny African Americans and some Latinos access to the Democratic primary. Following Reconstruction, Texas, like most of the South, was predominantly a one-party (Democratic) state. Between 1876 and 1926, the Republican Party held only one statewide primary in Texas. Thus, the Democratic primary was the main election in every even-numbered year.

White Democrats nominated white candidates, who almost always won the general elections. The U.S. Supreme Court had long held that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, as well as successive civil rights laws, provided protection against public acts of discrimination, but they did not protect against private acts of discrimination. In 1923, the Texas legislature passed a law explicitly prohibiting African Americans from voting in Democratic primaries. When the U.S. Supreme Court declared this law unconstitutional, the Texas legislature enacted another law giving the executive committee of each party the power to decide who could participate in its primaries. The State Democratic Executive Committee immediately adopted a resolution that limited party membership to whites only, which in effect allowed only whites to vote in Democratic primaries. This practice lasted from 1923 to 1944, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944).

Racial Gerrymandering

GerrymanderingDrawing the boundaries of a district designed to affect representation of a political party or group in a legislative chamber, city council, commissioners court, or other representative body. is the practice of manipulating legislative district lines to underrepresent persons of a political party or group. “Packing” black voters into a single district or “cracking” them to make black voters a minority in two or more districts both illustrate racial gerrymandering. Although racial gerrymandering that discriminates against minority voters is disallowed, federal law allows affirmative racial gerrymanderingDrawing the boundaries of a district designed to favor representation by a member of a historical minority group (e.g., African Americans) in a legislative chamber, city council, commissioners court, or other representative body. that results in the creation of “majority-minority” districts (also called minority-opportunity districts) favoring election of more racial and ethnic minority candidates. These districts must be reasonable in their configuration and cannot be based solely on race. In Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), the U.S. Supreme Court condemned two extremely odd-shaped African American–minority-opportunity districts in North Carolina.

A controversial redistricting plan adopted by the Texas legislature in 2003 to draw new U.S. congressional districts was challenged both by the Texas Democratic Party and by minority groups, contending it diluted minority voting strength. Although the primary purpose of the plan, as crafted by U.S. House majority leader Tom DeLay, was to increase the number of Republican representatives in the Congress, an internal memo from the U.S. Justice Department revealed that all of the attorneys in the department's voting section believed that the plan “illegally diluted black and Hispanic voting power in two congressional districts.” Despite these conclusions, senior-level administrators at the Justice Department approved the redistricting plan. Shortly after the plan was passed, it was challenged in court. By a 5–4 margin, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld most of the plan, which altered the Texas congressional delegation from a 17–15 Democratic majority to a 21–11 Republican majority for the remainder of the decade. But the Court invalidated one GOP-held district in South Texas on the grounds that it violated the Voting Rights Act by removing approximately 100,000 Democrats of Latino origin.

In 2011, the Texas legislature passed controversial redistricting plans designed to increase the number of Republicans in the state's congressional delegation and both chambers of the Texas legislature. This time, Texas was allowed four additional seats in the U.S. House of Representatives as a result of its population growth in relation to that of other states between 2000 and 2010. African American and Latino groups argued that growth in minority populations accounted for 89 percent of the state's population increase over that period. The congressional redistricting plan passed by the Republican-controlled state legislature, however, did not reflect the growth in these populations. Several minority organizations, including the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the League of United Latin American Citizens, the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, and the Texas NAACP (the state branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), brought suit against this plan because it diluted minority representation. In February 2012, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas agreed and drew interim congressional district maps that included two new districts with Latino majorities and two new districts with Anglo majorities. (For details on this subject, see the Chapter 8 Selected Reading, “Recent Congressional Redistricting in Texas.”) In early March of that year, the district court also ordered a revised election schedule that moved the primary election date to late May. In August, a three-judge federal district court in Washington ruled that the intent of the Texas legislature was to illegally discriminate against minorities, but the congressional and legislative redistricting plans were retained for the November 2012 general election.

In Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. ___ (2013), the U.S. Supreme Court declared unconstitutional Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which established a formula for determining which jurisdictions were required to obtain preclearance from the U.S. Department of Justice before making any alterations to their election laws. Writing for a 5–4 Court, Chief Justice John Roberts invalidated the provision because the coverage formula was based on 40-year old data, making the formula no longer responsive to current needs and “an impermissible burden on the constitutional principles of federalism and equal sovereignty of the states.” Governor Perry called the ruling “a clear victory for federalism and the states.” He noted, “Texas may now implement the will of the people without being subject to outdated and unnecessary oversight and the overreach of federal power.” Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott announced that “redistricting maps passed by the Legislature [could] also take effect without approval from the federal government.” In September 2013, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas denied a request by the State of Texas to dismiss claims about the 2011 House and congressional maps on grounds that, following the Shelby County decision, Texas was no longer required to seek preclearance from the U.S. Department of Justice. However, the district court ordered that the 2013 enacted congressional and Texas House maps be used as interim plans for the 2014 elections, deciding that a full, fair, and final review of all legal issues could not be resolved in time for these elections.

Diluting Minority Votes

Because of the likelihood that Latinos and African American voters will support the Democratic Party, attempts by the state legislature to favor Republican candidates in legislative and Congressional districts has resulted in claims that minority voting strength has been diluted. Another way minority voting strength may be diluted is through the creation of at-large majority districtsA district that elects two or more representatives. (each electing two or more representatives) for state legislatures and city councils. Under this scenario, the votes of a minority group can be diluted when combined with the votes of a majority group. Federal courts have declared this practice unconstitutional where representation of ethnic or racial minorities is diminished. In 2009, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that the city of Irving's method of choosing council members through citywide at-large elections diluted the influence of Latinos and violated the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-4b Democratization of the Ballot

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-4b Democratization of the Ballot

In America, successive waves of democratization have removed obstacles to voting. In the second half of the 20th century, the U.S. Congress enacted important voting rights laws to promote and protect voting nationwide.

Federal Voting Rights Legislation

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 expanded the electorate and encouraged voting. This act has been renewed and amended by Congress four times, including in 2006, when it was extended until 2031. The law (together with federal court rulings, including the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Shelby County v. Holder) now does the following:

Abolishes the use of all literacy tests in voter registrations

Prohibits residency requirements of more than 30 days for voting in presidential elections

Requires states to provide some form of absentee or early votingConducted at the county courthouse and selected polling places before the designated primary, special, or general election day.

Allows individuals (as well as the U.S. Department of Justice) to sue in federal court to request that voting examiners be sent to a particular area

Requires states and jurisdictions within a state with a significant percentage of residents whose primary language is one other than English to use bilingual ballots and other written election materials as well as provide bilingual oral assistance. In Texas, this information must be provided in Spanish throughout the state and in Vietnamese and Chinese in Harris County and Houston.

A bill passed by the Texas legislature in 2011 that required voters to provide photo identification to cast a ballot failed to obtain Department of Justice preclearance in August 2012. Following the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Shelby County v. Holder, Texas Attorney Greg Abbott announced that the state's voter ID law that had been challenged by the U.S. Department of Justice “[would] take effect immediately” and tweeted:

“Eric Holder can no longer deny #VoterID in #Texas after today's #SCOTUS decision. #txlege #tcot #txgop”

—Greg Abbott (@GregAbbott_TX) JUNE 25,2013

For a detailed discussion about the photo identification requirement, see this chapter's Point/Counterpoint feature.

The National Voter Registration Act, or motor-voter lawLegislation requiring certain government offices (e.g., motor vehicle licensing agencies) to offer voter registration applications to clients., permits registration by mail; at welfare, disability assistance, and motor vehicle licensing agencies; or at military recruitment centers. People can register to vote when they apply for, or renew, driver's licenses or when they visit a public assistance office. Motor vehicle offices and voter registration agencies are required to provide voter registration services to applicants. Using an appropriate state or federal voter registration form, Texas citizens can also apply for voter registration or update their voter registration data by mail. If citizens believe their voting rights have been violated in any way, federal administrative and judicial agencies, such as the U.S. Department of Justice, are available for assistance.

Amendments to the U.S. Constitution have also expanded the American electorate. The Fifteenth Amendment prohibits the denial of voting rights because of race; the Nineteenth Amendment precludes denial of suffrage on the basis of gender; the Twenty-Fourth Amendment prohibits states from requiring payment of a poll tax or any other tax as a condition for voting; and the Twenty-Sixth Amendment forbids setting the minimum voting age above 18 years.

Two Trends in Suffrage

From our overview of suffrage in Texas, two trends emerge. First, voting rights have steadily expanded to include virtually all persons, of both genders, who are 18 years of age or older. Second, there has been a movement toward uniformity of voting policies among the 50 states. However, democratization of the ballot has been pressed on the states largely by the U.S. Congress, by federal judges, and by presidents who have enforced voting laws and judicial orders.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-4c Voter Turnout

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-4c Voter Turnout

Now that nearly all legal barriers to the ballot have been swept away, the road to the voting booth seems clear for rich and poor alike; for historical minority groups, as well as for the historical majority; and for individuals of all races, colors, and creeds. But universal suffrage has not resulted in a corresponding increase in voter turnout, either nationally or in Texas.

Voter turnoutThe percentage of the voting-age population casting ballots in an election. is the percentage of the voting-age population casting ballots. In Texas, turnout is higher in presidential elections than in nonpresidential elections. Although this pattern reflects the national trend, electoral turnout in Texas tends to be significantly lower than in the nation as a whole. Even with George W. Bush running for reelection in the 2004 presidential election, Texas ranked below the national average in voter turnout, at 46 percent of the voting-age population, compared with the national average of 55 percent. According to the Center for the Study of the American Electorate, national turnout was even lower in 2012. Texas had the fifth lowest turnout in the nation, at 44 percent of the voting-age population, compared with the national average of 54 percent. Texas's lower voter turnout rates can be explained in part by the lower percentage of eligible voters in the state. Researchers at the U.S. Election Project at George Mason University estimated that 14 percent of the Lone Star State's population was ineligible to vote in 2012 because of citizenship status. Another 0.2 percent of Texas's population was ineligible to vote because of their status as convicted felons who had not completed serving their sentences. Therefore, voter turnout in Texas fares better when the voting-eligible population (rather than voting-age population) is considered. According to the United States Election Project, the 2012 statewide general election turnout rate of the voting-eligible population in Texas was slightly under 50 percent compared with a national turnout rate of more than 58 percent.

Due in part to less media attention, voter turnout in state and local elections is usually lower than in presidential elections. For instance, the 2010 Texas gubernatorial election yielded only a 27 percent turnout. Although few citizens believe their vote will determine an election outcome, some races have actually been won by a single vote. In local elections at the city or school district level, a turnout of 20 percent is relatively high. Among the five largest cities conducting city council elections in Texas in 2013, none yielded a turnout greater than 20 percent. These figures illustrate one of the ironies in politics: People are less likely to participate at the level of government where they can potentially have the greatest influence.

Low citizen participation in elections has been attributed to the influence of pollsters and media consultants, voter fatigue resulting from too many elections, negative campaigning by candidates, lack of information about candidates and issues, and feelings of isolation from government. Members of the Texas legislature determined that low voter turnout was caused by governmental entities holding too many elections. To cure “turnout burnout,” the legislature passed a law that limits most elections to two uniform election dates each year: the second Saturday in May and the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. However, this change has failed to yield a higher voter turnout as anticipated. For instance, in 2013, less than 6 percent of the voting-age population participated in the state's constitutional amendment election. Elections specifically exempted by statute that can be held on nonuniform dates include the following:

Runoff elections

Local option elections under the Alcoholic Beverage Code

Bond or tax levy elections for school districts or community college districts

Emergency elections called for or approved by the governor

Elections to fill vacancies in the two chambers of the Texas legislature

Elections to fill vacancies in the Texas delegation to the U.S. House of Representatives

Recall elections as authorized by city charters

People decide to vote or not to vote in the same way they make most other decisions: on the basis of anticipated consequences. A strong impulse to vote may stem from peer pressure, self-interest, or a sense of duty toward country, state, local community, political party, or interest group. People also decide whether to vote based on costs measured in time, money, experience, information, job, and other resources.

Cultural, socioeconomic, and ethnic or racial factors also contribute to the low voter turnout in the Lone Star State. As identified in Chapter 1, some elements of Texas's political culture place little emphasis on the importance of voting.

Of all the socioeconomic influences on voting, education is by far the strongest. Statistics clearly indicate that as educational level rises, so does the likelihood of voting, assuming all other socioeconomic factors remain constant. Educated people usually have more income and leisure time for voting; moreover, education enhances one's ability to learn about political parties, candidates, and issues. Education also strengthens voter efficacy (the belief that one's vote makes a difference). In addition, income strongly affects voter turnout. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2012 Texas ranked eighth in the nation in poverty, with 17.2 percent of the population living below the poverty level. People of lower income often lack access to the polls, information about the candidates, or opportunities to learn about the system. Income levels and their impact on electoral turnout can be seen in the 2012 general election. For example, Starr County, with a median household income of less than $25,000, had a turnout of slightly over 38 percent of its registered voters. By contrast, Collin County, with a median income of more than $83,000, experienced a turnout of almost 70 percent of its registered voters.

Although far less important than education and income, gender and age also affect voting behavior. In the United States, women are slightly more likely to vote than men. Young people (ages 18–25) have the lowest voter turnout of any age group. Nevertheless, participation by young people has increased in the last 10 years. The highest voter turnout is among middle-aged Americans (ages 40–64).

Race and ethnicity also influence voting behavior. Historically, the turnout rate for African Americans has remained substantially below that for Anglos. African Americans tend to be younger, less educated, and poorer than Anglos. In 2012, however, perhaps because of President Obama's candidacy, the percentage of African Americans who registered to vote and voted exceeded the state average for all races. Although Latino voter turnout rates in Texas are slightly below the state average in both primaries and general elections, findings by scholars indicate that the gap is narrowing. Latino voter registration rates for eligible voters in 2012 was 12 percent below that of Anglos and more than 19 percent below that of African Americans, and their voting rate remained approximately two-thirds of the state average.

//what about non-chapter activities //

Chapter 5: Campaigns and Elections: 5-4d Administering Elections

Book Title: Practicing Texas Politics

Printed By: Ali Hussain G Almutlaq ([email protected])

© 2015 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning

5-4d Administering Elections

In Texas, as in other states, determining voting procedures is essentially a state responsibility. The Texas Constitution authorizes the legislature to provide for the administration of elections. State lawmakers, in turn, have made the secretary of state the chief elections officer for Texas but have left most details of administering elections to county officials.

All election laws currently in effect in the Lone Star State are compiled into one body of law, the Texas Election CodeThe body of state law concerning parties, primaries, and elections.. In administering this legal code, however, state and party officials must protect voting rights guaranteed by federal law.

Qualifications for Voting

To be eligible to vote in Texas, a person must meet the following qualifications:

Be a native-born or naturalized citizen of the United States

Be at least 18 years of age on Election Day

Be a resident of the state and county for at least 30 days immediately preceding Election Day

Be a resident of the area covered by the election on Election Day

Be a registered voter for at least 30 days immediately preceding Election Day

Not be a convicted felon (unless sentence, probation, and parole are completed)

Not be declared mentally incompetent by a court of law

Most adults who live in Texas meet the first four qualifications for voting, but registration is required before a person can vote. Anyone serving a jail sentence as a result of a misdemeanor conviction or not finally convicted of a felony is not disqualified from voting. The Texas Constitution, however, bars from voting anyone who is incarcerated, on parole, or on probation as a result of a felony conviction and anyone who is “mentally incompetent as determined by a court.” A convicted felon may vote immediately after completing a sentence or following a full pardon. (For examples of misdemeanors and felonies, see Table 12.1.) Voter registration is intended to determine in advance whether prospective voters meet all the qualifications prescribed by law.

Most states, including Texas, use a permanent registration system. Under this plan, voters register once and remain registered unless they change their mailing address and fail to notify the voting registrar within three years or lose their eligibility to register in some other way. However, a story published in the Houston Chronicle in 2012 revealed that, as a result of outdated computer programs and faulty procedures, more than 1.5 million voters in Texas were purged from the voting rolls. It was reported that the registrations of one out of every 10 Texas voters was currently suspended (one out of every five Texas voters under 30). In Collin County, 70 percent of the voters who were removed from voter registration rolls were actually able to prove their eligibility. Following the voter roll purge controversy, Texas Secretary of State Hope Andrade submitted her resignation to Governor Perry on November 20, 2012.

Because the requirement of voter registration may deter voting, the Texas Election Code provides for voter registration centers in addition to those sites authorized by Congress under the motor-voter law. Thus, Texans may also register at local marriage license offices, in public high schools, with any volunteer deputy registrar, or in person at the office of the county voting registrar. Students away at college may choose to reregister using their college address as their residence if they want to vote locally. Otherwise, they must request an absentee ballot or be in their hometown during early voting or on Election Day if they wish to cast a ballot.

Between November 1 and November 15 of each odd-numbered year, the registrar mails to every registered voter in the county a registration certificate that is effective for the succeeding two voting years. Postal authorities may not forward a certificate mailed to the address indicated on the voter's application form to another address; instead, the certificate must be returned to the registrar. This practice enables the county voting registrar to maintain an accurate list of names and mailing addresses of persons to whom voting certificates have been issued. Registration files are open for public inspection in the voting registrar's office, and a statewide registration file is available in Austin at the Elections Division of the Office of the Secretary of State. Although certificates are normally issued in early November, the issuance of new voter registration certificates in 2011 was delayed because of legal battles surrounding redistricting. In early 2012, an order by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas instructed counties to issue the new certificates no later than April 25 of that year.