CIS375 Assignment

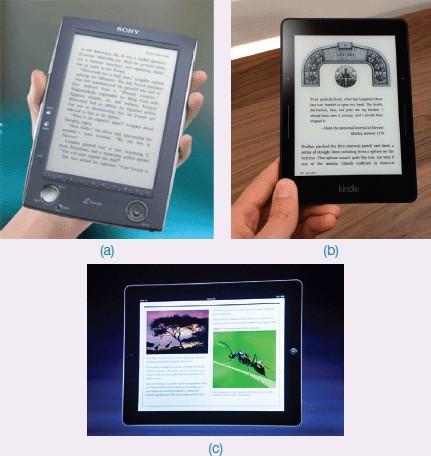

Activity 7.2Several ereaders for reading ebooks, watching movies, and browsing photographs are available on the market (see Figure 7.4). These devices are thin and lightweight and are ideally designed for reading books, newspapers, and magazines. The exact design differs between makes and models, but they all support book reading that is intended to be as comfortable as reading a paper book.

Source: (a) Courtesy of Sony Europe Limited, (b) and (c) ©PA Images.

The developers of a new ereader want to find out how appealing it will be to young people under 18 years of age. To this end, they have asked you to conduct some interviews for them.

What is the goal of your data gathering session?

Suggest ways of recording the interview data.

Suggest a set of questions that are suitable for use in an unstructured interview that seek opinions about ereaders and their appeal to the under18s.

Based on the results of the unstructured interviews, the developers of the new ereader have found that two important acceptance factors are whether the device can be handled easily and whether the typeface and appearance can be altered. Write a set of semistructured interview questions to evaluate these two aspects. If you have an e reader available, show it to two of your peers and ask them to comment on your questions. Refine the questions based on their comments.

It is helpful when collecting answers to list the possible responses together with boxes that can just be checked (i.e. ticked). Here's how we could convert some of the questions from Activity 7.2.

Have you used an ereader before? (Explore previous knowledge) Interviewer checks box

Yes

No

Don't remember/know

Would you like to read a book using an ereader? (Explore initial reaction, then explore the response)

Interviewer checks box Yes

No

Don't know

Why?

If response is ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ interviewer says, ‘Which of the following statements represents your feelings best?’

For ‘Yes,’ interviewer checks the box I don't like carrying heavy books

This is fun/cool

My friend told me they are great

It's the way of the future

Another reason (interviewer notes the reason) For ‘No,’ interviewer checks the box

I don't like using gadgets if I can avoid it

I can't read the screen clearly

I prefer the feel of paper

Another reason (interviewer notes the reason)

In your opinion, is an ereader easy to handle or cumbersome? Interviewer checks box

Easy to handle

Cumbersome

Neither

Running the Interview

Before starting, make sure that the aims of the interview have been communicated to and understood by the interviewees, and they feel comfortable. Some simple techniques can help here, such as finding out about their world before the interview so that you can dress, act, and speak in a manner that will be familiar. This is particularly important when working with children, seniors, people from different ethnic and cultural groups, people who have disabilities, and seriously ill patients.

During the interview, it is better to listen more than to talk, to respond with sympathy but without bias, and to appear to enjoy the interview (Robson, 2011). Robson suggests the following steps for conducting an interview:

An introduction in which the interviewer introduces herself and explains why she is doing the interview, reassures interviewees regarding any ethical issues, and asks if they mind being recorded, if appropriate. This should be exactly the same for each interviewee.

A warmup session where easy, nonthreatening questions come first. These may include questions about demographic information, such as ‘What area of the country do you live in?'

A main session in which the questions are presented in a logical sequence, with the more probing ones at the end. In a semistructured interview the order of questions may vary between participants, depending on the course of the conversation, how much probing is done, and what seems more natural.

A cooloff period consisting of a few easy questions (to defuse any tension that may have arisen).

A closing session in which the interviewer thanks the interviewee and switches off the recorder or puts her notebook away, signaling that the interview has ended.

- Other Forms of Interview

Conducting facetoface interviews and focus groups can sometimes be impractical, especially when the participants live in different geographical areas. Skype, email, and phonebased interactions, sometimes with screensharing software, are therefore increasing in popularity.

These are carried out similarly to facetoface sessions, although such issues as dropped Skype connections and insufficient Internet bandwidth for reliable video can be a challenge to conducting them. However, there are some advantages to remote focus groups and interviews, especially when done through audioonly channels. For example, the participants are in their own environment and are more relaxed, participants don't have to worry about what they wear, who other people are, or interact in an unnatural environment surrounded by strangers; for interviews that involve sensitive issues, interviewees may prefer to be anonymous. In addition, participants can leave the conversation whenever they want to by just putting down the phone, which adds to their sense of security. While it is questionable whether data collected faceto face can be compared directly with data collected remotely, it seems that remote phonebased group or individual interviews are preferable at least in some circumstances.

Retrospective interviews, i.e. interviews which reflect on an activity or a data gathering session in the recent past, may be conducted with participants to check that the interviewer has correctly understood what was happening.

Link to more information on telephone focus groups, at

http://mnav.com/shockingtruth/ and for some interesting thoughts on remote usability testing, see http://www.uxbooth.com/articles/hiddenbenefitsremoteresearch/

- Enriching the Interview Experience

Facetoface interviews often take place in a neutral environment, e.g. a meeting room away from the interviewee's normal place of work or their home. In such situations the interview location provides an artificial context that is different from the interviewee's normal tasks. In these circumstances it can be difficult for interviewees to give full answers to the questions posed. To help combat this, interviews can be enriched by using props such as prototypes or work artifacts that the interviewee or interviewer brings along, or descriptions of common tasks (examples of these kinds of props are scenarios and prototypes, which are covered in Chapters

10 and 11). These props can be used to provide context for the interviewees and help to ground the data in a real setting. Figure 7.5 illustrates the use of prototypes in a focus group setting.

For example, Jones et al (2004) used diaries as a basis for interviews. They performed a study to probe the extent to which certain places are associated with particular activities and information needs. Each participant was asked to keep a diary in which they entered information about where they were and what they were doing at 30 minute intervals. The interview questions were then based around their diary entries.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are a wellestablished technique for collecting demographic data and users’ opinions. They are similar to interviews in that they can have closed or open questions but they can be distributed to a larger number of participants so more data can be collected than would normally be possible in an interview study. Furthermore, the issues of involving people who are located in remote locations or cannot attend an interview at a particular time can be dealt with more conveniently. Often a message is sent electronically to potential participants to direct them to an online questionnaire.

Effort and skill are needed to ensure that questions are clearly worded and the data collected can be analyzed efficiently. Welldesigned questionnaires are good at getting answers to specific questions from a large group of people. Questionnaires can be used on their own or in conjunction with other methods to clarify or deepen understanding. For example, information obtained through interviews with a small selection of interviewees might be corroborated by sending a questionnaire to a wider group to confirm the conclusions.

Questionnaire questions and structured interview questions are similar, so how do you know when to use which technique? Essentially, the difference lies in the motivation of the respondent to answer the questions. If you think that this motivation is high enough to complete a questionnaire without anyone else present, then a questionnaire will be appropriate. On the other hand, if the respondents need some persuasion to answer the questions, it would be better to use an interview format and ask the questions facetoface through a structured interview. For example, structured interviews are easier and quicker to conduct in situations in which people will not stop to complete a questionnaire, such as at a train station or while walking to their next meeting.

It can be harder to develop good questionnaire questions compared with structured interview questions because the interviewer is not available to explain them or to clarify any ambiguities. Because of this, it is important that questions are specific; when possible, closed questions should be asked and a range of answers offered, including a ‘no opinion’ or ‘none of these’ option. Finally, negative questions can be confusing and may lead to the respondents giving false information, although some questionnaire designers use a mixture of negative and positive questions deliberately because it helps to check the users’ intentions.

- Questionnaire Structure

Many questionnaires start by asking for basic demographic information (gender, age, place of birth) and details of relevant experience (the time or number of years spent using computers, or the level of expertise within the domain under study, etc.). This background information is useful for putting the questionnaire responses into context. For example, if two respondents conflict, these different perspectives may be due to their level of experience – a group of people who are using a social networking site for the first time are likely to express different opinions to another group with five years’ experience of such sites. However, only contextual information that is relevant to the study goal needs to be collected. In the example above, it is unlikely that the person's shoe size will provide relevant context to their responses!

Specific questions that contribute to the data gathering goal usually follow these more general questions. If the questionnaire is long, the questions may be subdivided into related topics to make it easier and more logical to complete.

The following is a checklist of general advice for designing a questionnaire:

Think about the ordering of questions. The impact of a question can be influenced by question order.

Consider whether you need different versions of the questionnaire for different populations.

Provide clear instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. For example, if only one of the boxes needs to be checked, then say so. Questionnaires can make their message clear with careful wording and good typography.

A balance must be struck between using white space and the need to keep the questionnaire as compact as possible.

- Question and Response Format

Different formats of question and response can be chosen. For example, with a closed question, it may be appropriate to indicate only one response, or it may be appropriate to indicate several. Sometimes it is better to ask users to locate their answer within a range. Selecting the most appropriate question and response format makes it easier for respondents to answer clearly. Some commonly used formats are described below.

Check Boxes and Ranges

The range of answers to demographic questionnaires is predictable. Gender, for example, has two options, male or female, so providing the two options and asking respondents to circle a response makes sense for collecting this information. A similar approach can be adopted if details of age are needed. But since some people do not like to give their exact age, many questionnaires ask respondents to specify their age as a range. A common design error arises when the ranges overlap. For example, specifying two ranges as 15–20, 20–25 will cause confusion: which box do people who are 20 years old check? Making the ranges 14–19, 20–24 avoids this problem.

A frequently asked question about ranges is whether the interval must be equal in all cases. The answer is no – it depends on what you want to know. For example, if you want to identify people who might use a website about life insurance, you will most likely be interested in people with jobs who are 21–65 years old. You could, therefore, have just three ranges: under 21, 21– 65, and over 65. In contrast, if you wanted to see how the population's political views varied across the generations, you might be interested in looking at 10year cohort groups for people over 21, in which case the following ranges would be appropriate: under 21, 22–31, 32–41, etc.

Rating Scales

There are a number of different types of rating scales that can be used, each with its own purpose (see Oppenheim, 1998). Here we describe two commonly used scales: the Likert and semantic differential scales. The purpose of these is to elicit a range of responses to a question that can be compared across respondents. They are good for getting people to make judgments about things, e.g. how easy, how usable, and the like.

The success of Likert scales relies on identifying a set of statements representing a range of possible opinions, while semantic differential scales rely on choosing pairs of words that represent the range of possible opinions. Likert scales are more commonly used because identifying suitable statements that respondents will understand is easier than identifying semantic pairs that respondents interpret as intended.

Likert scales.

Likert scales are used for measuring opinions, attitudes, and beliefs, and consequently they are widely used for evaluating user satisfaction with products. For example, users’ opinions about the use of color in a website could be evaluated with a Likert scale using a range of numbers, as in (1), or with words as in (2):

The use of color is excellent (where 1 represents strongly agree and 5 represents strongly disagree):

![CIS375 Assignment 3]()

The use of color is excellent:

![]()

In both cases, respondents could be asked to tick or ring the right box, number or phrase. Designing a Likert scale involves the following three steps:

Gather a pool of short statements about the subject to be investigated. For example, ‘This control panel is clear’ or ‘The procedure for checking credit rating is too complex.’ A brainstorming session with peers in which you identify key aspects to be investigated is a good way of doing this.

Decide on the scale. There are three main issues to be addressed here: How many points does the scale need? Should the scale be discrete or continuous? How to represent the scale? See Box 7.3 for more on this topic.

Select items for the final questionnaire and reword as necessary to make them clear.

In the first example above, the scale is arranged with 1 as the highest choice on the left and 5 as the lowest choice on the right. While there is no absolute right or wrong way of ordering the numbers, some reseachers prefer to have 1 as the higher rating on the left and 5 as the lowest rating on the right. The logic for this is that first is the best place to be in a race and fifth would be the worst. Other researchers prefer to arrange the scales the other way around with 1 as the lowest on the left and 5 as the highest on the right. They argue that intuitively the higher number suggests the best choice and the lowest number suggests the worst choice. Another reason for going from lowest to highest is that when the results are reported, it is more intuitive for readers to see high numbers representing the best choices. The important things to remember are to decide which way around you will apply the scales, make sure your participants know, and then apply your scales consistently throughout your questionnaire.

Semantic differential scales.

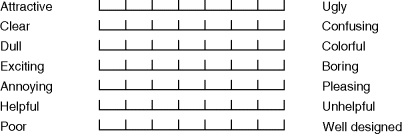

Semantic differential scales explore a range of bipolar attitudes about a particular item. Each pair of attitudes is represented as a pair of adjectives. The participant is asked to place a cross in one of a number of positions between the two extremes to indicate agreement with the poles, as shown in Figure 7.6. The score for the investigation is found by summing the scores for each bipolar pair. Scores can then be computed across groups of participants. Notice that in this example the poles are mixed, so that good and bad features are distributed on the right and the left. In this example there are seven positions on the scale.

BOX 7.3

What Scales to Use: Three, Five, Seven, or More?

When designing Likert and semantic differential scales, issues that need to be addressed include: how many points are needed on the scale, how should they be presented, and in what form?

Many questionnaires use seven or fivepoint scales and there are also threepoint scales. Some even use 9point scales. Arguments for the number of points go both ways.

Advocates of long scales argue that they help to show discrimination. Rating features on an interface is more difficult for most people than, say, selecting among different flavors of ice cream, and when the task is difficult there is evidence to show that people ‘hedge their bets.’ Rather than selecting the poles of the scales if there is no right or wrong, respondents tend to select values nearer the center. The counterargument is that people cannot be expected to discern accurately among points on a large scale, so any scale of more than five points is unnecessarily difficult to use.

Another aspect to consider is whether the scale should have an even or odd number of points. An odd number provides a clear central point. On the other hand, an even number forces participants to make a decision and prevents them from sitting on the fence.

We suggest the following guidelines: How many points on the scale?

Use a small number, e.g. three, when the possibilities are very limited, as in yes/no type answers:

Use a mediumsized range, e.g. five, when making judgments that involve like/dislike, agree/disagree statements:

![]()

Use a longer range, e.g. seven or nine, when asking respondents to make subtle judgments. For example, when asking about a user experience dimension such as ‘level of appeal’ of a character in a video game:![]()

Discrete or continuous?

Use boxrs for discrete choices and scales for finer judgments.

What order?

Decide which way you will order your scale and be consistent. For example, some people like to go from the strongest agreement tot eh weakest because they find it intuitive to order the scale that way:

-strongly agree

-slightly agree

-agree

-slightly disagree

-strongly disagree