AS BELOW

C H7A P T E R Collecting

Qualitative Data

Qualitative data collection is more than simply deciding on whether you will observe or interview people. Five steps comprise the process of collecting qualitative data. You need to identify your participants and sites, gain access, determine the types of data to collect, develop data collection forms, and administer the process in an ethical manner.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

◆ Identify the five process steps in collecting qualitative data.

◆ Identify different sampling approaches to selecting participants and sites.

◆ Describe the types of permissions required to gain access to participants and sites.

◆ Recognize the various types of qualitative data you can collect.

◆ Identify the procedures for recording qualitative data.

◆ Recognize the field issues and ethical considerations that need to be anticipated in administering the data collection. Maria is comfortable talking with students and teachers in her high school. She does not mind asking them open-ended research questions such as “What are your (student and teacher) experiences with students carrying weapons in our high school?” She also knows the challenges involved in obtaining their views. She needs to listen without injecting her own opinions, and she needs to take notes or tape-record what people have to say. This phase requires time, but Maria enjoys talking with people and listening to their ideas. Maria is a natural qualitative researcher.

204

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 205 WHAT ARE THE FIVE PROCESS STEPS

IN QUALITATIVE DATA COLLECTION?

There are five interrelated steps in the process of qualitative data collection. These steps should not be seen as linear approaches, but often one step in the process does follow another. The five steps are first to identify participants and sites to be studied and to engage in a sampling strategy that will best help you understand your central phenome- non and the research question you are asking. Second, the next phase is to gain access to these individuals and sites by obtaining permissions. Third, once permissions are in place, you need to consider what types of information will best answer your research questions. Fourth, at the same time, you need to design protocols or instruments for collecting and recording the information. Finally and fifth, you need to administer the data collection with special attention to potential ethical issues that may arise.

Some basic differences between quantitative and qualitative data collection are helpful to know at this point. Based on the general characteristics of qualitative research, qualita- tive data collection consists of collecting data using forms with general, emerging questions to permit the participant to generate responses; gathering word (text) or image (picture) data; and collecting information from a small number of individuals or sites. Thinking more specifically now,

◆ In quantitative research, we systematically identify our participants and sites through random sampling; in qualitative research, we identify our participants and sites on purposeful sampling, based on places and people that can best help us understand our central phenomenon.

◆ In both quantitative and qualitative research, we need permissions to begin our study, but in qualitative research, we need greater access to the site because we will typically go to the site and interview people or observe them. This process requires a greater level of participation from the site than does the quantitative research process.

◆ In both approaches, we collect data such as interviews, observations, and documents. In qualitative research, our approach relies on general interviews or observations so that we do not restrict the views of participants. We will not use someone else’s instrument as in quantitative research and gather closed-ended information; we will instead collect data with a few open-ended questions that we design.

◆ In both approaches, we need to record the information supplied by the participants. Rather than using predesigned instruments from someone else or instruments that we design, in qualitative research we will record information on self-designed protocols that help us organize information reported by participants to each question.

◆ Finally, we will administer our procedures of qualitative data collection with sensitivity to the challenges and ethical issues of gathering information face-to-face and often in people’s homes or workplaces. Studying people in their own environ- ment creates challenges for the qualitative researcher that may not be present in quantitative research when investigators mail out anonymous questionnaires or bring individuals into the experimental laboratory.

![]()

206 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT SAMPLING APPROACHES

FOR SELECTING PARTICIPANTS AND SITES?

In qualitative inquiry, the intent is not to generalize to a population, but to develop an in- depth exploration of a central phenomenon. Thus, to best understand this phenomenon, the qualitative researcher purposefully or intentionally selects individuals and sites. This distinction between quantitative “random sampling” and qualitative “purposeful sampling” is portrayed in Figure 7.1.

In quantitative research, the focus is on random sampling, selecting representative indi- viduals, and then generalizing from these individuals to a population. Often this process results in testing “theories” that explain the population. However, in qualitative research, you select people or sites that can best help you understand the central phenomenon. This understanding emerges through a detailed understanding of the people or site. It can lead to information that allows individuals to “learn” about the phenomenon, or to an under- standing that provides voice to individuals who may not be heard otherwise.

Purposeful Sampling

The research term used for qualitative sampling is purposeful sampling. In purposeful sampling, researchers intentionally select individuals and sites to learn or understand the central phenomenon. The standard used in choosing participants and sites is whether they are “information rich” (Patton, 1990, p. 169). In any given qualitative study, you may decide to study a site (e.g., one college campus), several sites (three small liberal arts campuses), individuals or groups (freshman students), or some combination (two liberal arts campuses and several freshman students on those campuses). Purposeful sampling thus applies to both individuals and sites.

If you conduct your own study and use purposeful sampling, you need to identify your sampling strategy and be able to defend its use. The literature identifies several qualitative sampling strategies (see Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 1990). As seen in Figure 7.2, you have a choice of selecting from one to several sampling strategies that educators frequently use. These strategies are differentiated in terms of whether they are employed before data collection begins or after data collection has started (an approach consistent with an emerging design). Further, each has a different intent, depending on

![]()

| FIGURE 7.1 |

| Difference between Random Sampling and Purposeful Sampling |

| Random “Quantitative” Sampling To make “claims” about the population To build/test “theories” that explain the population Purposeful “Qualitative” Sampling That might provide “useful” information That might help people “learn” about the phenomenon That might give voice to “silenced” people Select representative individuals Select people or sites who can best help us understand our phenomenon To generalize from sample to the population To develop a detailed understanding |

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 207

| FIGURE 7.2 |

| Types of Purposeful Sampling |

|

Before Data Collection? What is the intent? After Data Collection Has Started? What is the intent? When Does Sampling Occur? To develop many perspectives To describe particularly troublesome or enlightening cases To describe what is “typical” to those unfamiliar with the case To describe a case that illustrates “dramatically” the situation To describe some subgroup in depth To take advantage of whatever case unfolds To explore confirming or disconfirming cases To locate people or sites to study Maximal Variation Sampling Critical Sampling Opportunistic Sampling Confirming/ Disconfirming Sampling Snowball Sampling Extreme Case Sampling Homogeneous Sampling To generate a theory or explore a concept Theory or Concept Sampling Typical Sampling |

the research problem and questions you would like answered in a study. All strategies apply to sampling a single time or multiple times during a study, and you can use them to sample from individuals, groups, or entire organizations and sites. In some studies, it may be necessary to use several different sampling strategies (e.g., to select teachers in a school and to select different schools to be incorporated into the sample).

Maximal Variation Sampling

One characteristic of qualitative research is to present multiple perspectives of individu- als to represent the complexity of our world. Thus, one sampling strategy is to build that complexity into the research when sampling participants or sites. Maximal variation sampling is a purposeful sampling strategy in which the researcher samples cases or

208 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

individuals that differ on some characteristic or trait (e.g., different age groups). This pro- cedure requires that you identify the characteristic and then find sites or individuals that display different dimensions of that characteristic. For example, a researcher might first identify the characteristic of racial composition of high schools, and then purposefully sample three high schools that differ on this characteristic, such as a primarily Hispanic high school, a predominantly white high school, and a racially diverse high school.

Extreme Case Sampling

Sometimes you are more interested in learning about a case that is particularly trouble- some or enlightening, or a case that is noticeable for its success or failure (Patton, 1990). Extreme case sampling is a form of purposeful sampling in which you study an outlier case or one that displays extreme characteristics. Researchers identify these cases by locating persons or organizations that others have cited for achievements or distinguish- ing characteristics (e.g., certain elementary schools targeted for federal assistance). An autistic education program in elementary education that has received awards may be an outstanding case to purposefully sample.

Typical Sampling

Some research questions address “What is normal?” or “What is typical?” Typical sam- pling is a form of purposeful sampling in which the researcher studies a person or site that is “typical” to those unfamiliar with the situation. What constitutes typical, of course, is open to interpretation. However, you might ask persons at a research site or even select a typical case by collecting demographic data or survey data about all cases. You could study a typical faculty member at a small liberal arts college because that individual has worked at the institution for 20 years and has embodied the cultural norms of the school.

Theory or Concept Sampling

You might select individuals or sites because they help you understand a concept or a theory. Theory or concept sampling is a purposeful sampling strategy in which the researcher samples individuals or sites because they can help the researcher generate or discover a theory or specific concepts within the theory. To use this method, you need a clear understanding of the concept or larger theory expected to emerge during the research. In a study of five sites that have experienced distance education, for example, you have chosen these sites because study of them can help generate a theory of student attitudes toward distance learning.

Homogeneous Sampling

You might select certain sites or people because they possess a similar trait or char- acteristic. In homogeneous sampling the researcher purposefully samples individuals or sites based on membership in a subgroup that has defining characteristics. To use this procedure, you need to identify the characteristics and find individuals or sites that possess it. For example, in a rural community, all parents who have children in school participate in a parent program. You choose members of this parent program to study because they belong to a common subgroup in the community.

Critical Sampling

Sometimes individuals or research sites represent the central phenomenon in dramatic terms (Patton, 1990). The sampling strategy here is to study a critical sample because it is an exceptional case and the researcher can learn much about the phenomenon. For example, you study teenage violence in a high school where a student with a gun threat- ened a teacher. This situation represents a dramatic incident that portrays the extent to which some adolescents may engage in school violence.

Opportunistic Sampling

After data collection begins, you may find that you need to collect new information to best answer your research questions. Opportunistic sampling is purposeful sampling undertaken after the research begins, to take advantage of unfolding events that will help answer research questions. In this process, the sample emerges during the inquiry. Researchers need to be cautious about engaging in this form of sampling because it might divert attention away from the original aims of the research. However, it captures the developing or emerging nature of qualitative research nicely and can lead to novel ideas and surprising findings. For example, you begin a study with maximal variation sampling of different pregnant teenagers in high schools. During this process you find a pregnant teenager who plans to bring her baby to school each day. Because a study of this teen- ager would provide new insights about balancing children and school, you study her activities during her pregnancy at the school and in the months after the birth of her child.

Snowball Sampling

In certain research situations, you may not know the best people to study because of the unfamiliarity of the topic or the complexity of events. As in quantitative research, quali- tative snowball sampling is a form of purposeful sampling that typically proceeds after a study begins and occurs when the researcher asks participants to recommend other individuals to be sampled. Researchers may pose this request as a question during an interview or through informal conversations with individuals at a research site.

Con rming and Discon rming Sampling

A final form of purposeful sampling, also used after studies begin, is to sample individu- als or sites to confirm or disconfirm preliminary findings. Confirming and disconfirm- ing sampling is a purposeful strategy used during a study to follow up on specific cases to test or explore further specific findings. Although this sampling serves to verify the accuracy of the findings throughout a study, it also represents a sampling procedure used during a study. For example, you find out that academic department chairs support faculty in their development as teachers by serving as mentors. After initially interviewing chairs, you further confirm the mentoring role by sampling and studying chairs that have received praise from faculty as “good” mentors.

Sample Size or Number of Research Sites

The number of people and sites sampled vary from one qualitative study to the next. You might examine some published qualitative studies and see what numbers of sites or participants researchers used. Here are some general guidelines:

◆ It is typical in qualitative research to study a few individuals or a few cases. This is because the overall ability of a researcher to provide an in-depth picture dimin- ishes with the addition of each new individual or site. One objective of qualitative research is to present the complexity of a site or of the information provided by individuals.

◆ In some cases, you might study a single individual or a single site. In other cases, the number may be several, ranging from 1 or 2 to 30 or 40. Because of the need to report details about each individual or site, the larger number of cases can become unwieldy and result in superficial perspectives. Moreover, collecting qualitative data and analyzing it takes considerable time, and the addition of each individual or site only lengthens that time. Let’s look at some specific examples to see how many individuals and sites were used. Qualitative researchers may collect data from single individuals. For example, in

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 209

210 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

the qualitative case study of Basil McGee, a second-year middle school science teacher, Brickhouse and Bodner (1992) explored his beliefs about science and science teaching and how his beliefs shaped classroom instruction. Elsewhere, several individuals partici- pated in a qualitative grounded theory study. The researchers examined 20 parents of children labeled as ADHD (Reid, Hertzog, & Snyder, 1996). More extensive data collec- tion was used in a qualitative ethnographic study of the culture of fraternity life and the exploitation and victimization of women. Rhoads (1995) conducted 12 formal interviews and 18 informal interviews, made observations, and collected numerous documents.

If you were Maria, and you sought to answer the question “What are the students’ experiences with carrying weapons in the high school?” what purposeful sampling strat- egy would you use? Before you look at the answers I provide, write down at least two possibilities on a sheet of paper.

Let’s create some options depending on the students that Maria has available to her to study.

◆ One option would be to use maximal variation sampling and interview several students who vary in the type of weapon infraction they committed in the school. For instance, one student may have threatened another student. Another student may have actually used a knife in a fight. Another student may have kept a knife in a locker and a teacher discovered it. These three students represent different types of weapon possession in the school, and each will likely provide different views on students having knives in the school.

◆ Another option would be to use critical sampling. You might interview a student who actually used a knife during a fight. This is an example of a public use of a weapon, and it represents a dramatic action worthy of study by itself. Can you think of other approaches to sampling that you might use? Also, how many students would you study and what is the reason for your choice? WHAT TYPES OF PERMISSIONS WILL BE REQUIRED TO GAIN ACCESS TO PARTICIPANTS AND SITES? Similar to quantitative research, gaining access to the site or individual(s) in qualitative inquiry involves obtaining permissions at different levels, such as the organization, the site, the individuals, and the campus institutional review boards. Of special importance is negotiating approval with campus review boards and locating individuals at a site who can facilitate the collection of qualitative data. Seek Institutional Review Board Approval Researchers applying for permission to study individuals in a qualitative project must go through the approval process of a campus institutional review board. These steps include seeking permission from the board, developing a description of the project, designing an informed consent form, and having the project reviewed. Because qualitative data collection consists of lengthy periods of gathering information directly involving people and recording detailed personal views from individuals, you will need to provide a detailed description of your procedures to the institutional review board. This detail is needed because the board may not be familiar with the qualitative approach to educational research and because you will spend time in people’s homes, workplaces, or sites in which you gather data.

![]()

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 211 Several strategies might prove useful when negotiating qualitative research through

the institutional review board process:

◆ Determine if individuals reviewing proposals on the review board are familiar with qualitative inquiry. Look for those individuals who have experience in conducting qualitative research. This requires a careful assessment of the membership of the review board.

◆ Develop detailed descriptions of the procedures so that reviewers have a full dis- closure of the potential risks to people and sites in the study.

◆ Detail ways you will protect the anonymity of participants. These might be masking names of individuals, assigning pseudonyms to individuals and their organizations, or choosing to withhold descriptors that would lead to the identification of partici- pants and sites.

◆ Discuss the need to respect the research site and to disturb or disrupt it as little as possible. When you gain permission to enter the site, you need to be respectful of property and refrain from introducing issues that may cause participants to question their group or organization. Doing this requires keeping a delicate balance between exploring a phenomenon in depth and respecting individuals and property at the research site.

◆ Detail how the study will provide opportunities to “give back” or reciprocate in some way to those individuals you study (e.g., you might donate services at the site, become an advocate for the needs of those studied, or share with them any monetary rewards you may receive from your study).

◆ Acknowledge that during your prolonged interaction with participants, you may adopt their beliefs and even become an advocate for their ideas.

◆ Specify potential power imbalances that may occur between yourself and the participants, and how your study will address these imbalances. For exam- ple, a power imbalance occurs when researchers study their own employers or employees in the workplace. If this is your situation, consider researching sites where you do not have an interest or try to collect data in a way that minimizes a power inequality between yourself and participants (e.g., observing rather than interviewing).

◆ Detail how much time you will spend at the research site. This detail might include the anticipated number of days, the length of each visit, and the times when visits will take place.

◆ Include in the project description a list of the interview questions so reviewers on the institutional board can determine how sensitive the questions may be. Typically, qualitative interview questions are open ended and general, lending support to a noninvasive stance by the researcher. Gatekeepers In qualitative research, you often need to seek and obtain permissions from individuals and sites at many levels. Because of the in-depth nature of extensive and multiple inter- views with participants, it might be helpful for you to identify and make use of a gate- keeper. A gatekeeper is an individual who has an official or unofficial role at the site, provides entrance to a site, helps researchers locate people, and assists in the identification of places to study (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995). For example, this individual may be a teacher, a principal, a group leader, or the informal leader of a special program, and usu- ally has “insider” status at the site the researchers plan to study. Identifying a gatekeeper at a research site and winning his or her support and trust may take time. You might be

212 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research required to submit written information about the project to proceed. Such information

might include:

◆ Why their site was chosen for study

◆ What will be accomplished at the site during the research study (i.e., time and resources required by participants and yourself)

◆ How much time you will spend at the site

◆ What potential there is for your presence to be disruptive

◆ How you will use and report the results

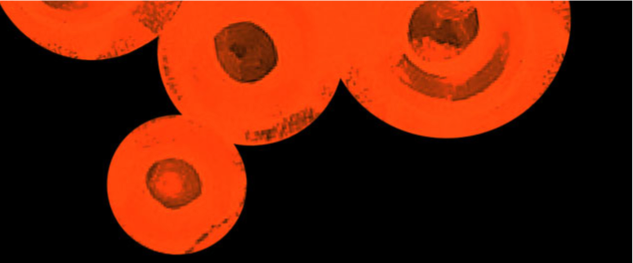

◆ What the individuals at the site will gain from the study (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998) Let’s look at an example of using a gatekeeper in a qualitative study: While conducting a qualitative study exploring the behavior of informal student cliques that may display violent behavior, a researcher talks to many high school personnel. Ultimately, the social studies coordinator emerges as a good gatekeeper. She suggests the researcher use the school cafeteria as an important site to see school cliques in action. She also points out specific student leaders of cliques (e.g., the punk group) who might help the researcher understand student behavior. WHAT TYPES OF QUALITATIVE DATA WILL YOU COLLECT? Another aspect of qualitative data collection is to identify the types of data that will address your research questions. Thus, it is important to become familiar with your ques- tions and topics, and to review them prior to deciding upon the types of qualitative data that you will collect. In qualitative research you pose general, broad questions to partici- pants and allow them to share their views relatively unconstrained by your perspective. In addition, you collect multiple types of information, and you may add new forms of data during the study to answer your questions. Further, you engage in extensive data collection, spending a great deal of time at the site where people work, play, or engage in the phenomenon you wish to study. At the site, you will gather detailed information to establish the complexity of the central phenomenon. We can see the varied nature of qualitative forms of data when they are placed into the following categories: ◆ Observations ◆ Interviews and questionnaires ◆ Documents ◆ Audiovisual materials Specific examples of types of data in these four categories are shown in Figure 7.3. Variations on data collection in all four areas are emerging continuously. Most recently, videotapes, student classroom portfolios, and the use of e-mails are attracting increasing attention as forms of data. Table 7.1 shows each category of data collection listed, the type of data it yields, and a definition for that type of data. Now let’s take a closer look at each of the four categories and their strengths and weaknesses. Observations When educators think about qualitative research, they often have in mind the process of collecting observational data in a specific school setting. Unquestionably, observations represent a frequently used form of data collection, with the researcher able to assume different roles in the process (Spradley, 1980).

![]()

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 213

| FIGURE 7.3 |

| A Compendium of Data Collection Approaches in Qualitative Research |

| Observations Gather fieldnotes by: Conducting an observation as a participant Conducting an observation as an observer Spending more time as a participant than observer Spending more time as an observer than a participant First observing as an “outsider,” then participating in the setting and observing as an “insider” Interviews and Questionnaires Conduct an unstructured, open-ended interview and take interview notes. Conduct an unstructured, open-ended interview; audiotape the interview and transcribe it. Conduct a semistructured interview; audiotape the interview and transcribe it. Conduct focus group interviews; audiotape the interviews and transcribe them. Collect open-ended responses to an electronic interview or questionnaire. Gather open-ended responses to questions on a questionnaire. Documents Keep a journal during the research study. Have a participant keep a journal or diary during the research study. Collect personal letters from participants. Analyze public documents (e.g., official memos, minutes of meetings, records or archival material). Analyze school documents (e.g., attendance reports, retention rates, dropout rates, or discipline referrals). Examine autobiographies and biographies. Collect or draw maps and seating charts. Examine portfolios or less formal examples of students’ work. Collect e-mails or electronic data. Audiovisual Materials Examine physical trace evidence (e.g., footprints in the snow). Videotape a social situation of an individual or group. Examine photographs or videotapes. Collect sounds (e.g., musical sounds, a child’s laughter, or car horns honking). Examine possessions or ritual objects. Have participants take photos or videotapes. |

Sources: Creswell, 2007; Mills, 2011.

Observation is the process of gathering open-ended, firsthand information by observing people and places at a research site. As a form of data collection, observation has both advantages and disadvantages. Advantages include the opportunity to record information as it occurs in a setting, to study actual behavior, and to study individuals who

214 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

| TABLE 7.1 | ||

| Forms of Qualitative Data Collection | ||

| Forms of Data Collection | Type of Data | De nition of Type of Data |

| Observations | Fieldnotes and drawings | Unstructured text data and pictures taken during observations by the researcher |

| Interviews and questionnaires | Transcriptions of open-ended interviews or open-ended questions on questionnaires | Unstructured text data obtained from transcribing audiotapes of interviews or by transcribing open-ended responses to questions on questionnaires |

| Documents | Hand-recorded notes about documents or optically scanned documents | Public (e.g., notes from meetings) and private (e.g., journals) records available to the researcher |

| Audiovisual materials | Pictures, photographs, videotapes, objects, sounds | Audiovisual materials consisting of images or sounds of people or places recorded by the researcher or someone else |

have difficulty verbalizing their ideas (e.g., preschool children). Some of the disadvantages of observations are that you will be limited to those sites and situations where you can gain access, and in those sites, you may have difficulty developing rapport with individu- als. This can occur if the individuals are unaccustomed to formal research (e.g., a nonuni- versity setting). Observing in a setting requires good listening skills and careful attention to visual detail. It also requires management of issues such as the potential deception by people being observed and the initial awkwardness of being an “outsider” without initial personal support in a setting (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995).

Observational Roles

Despite these potential difficulties, observation continues to be a well-accepted form of qualitative data collection. Using it requires that you adopt a particular role as an observer. No one role is suited for all situations; observational roles vary depending on your com- fort at the site, your rapport with participants, and how best you can collect data to under- stand the central phenomenon. Although many roles exist (see Spradley, 1980), you might consider one of three popular roles.

Role of a Participant Observer To truly learn about a situation, you can become involved in activities at the research site. This offers excellent opportunities to see experiences from the views of participants. A participant observer is an observational role adopted by researchers when they take part in activities in the setting they observe. As a participant, you assume the role of an “inside” observer who actually engages in activities at the study site. At the same time that you are participating in activities, you record information. This role requires seeking permission to participate in activities and assuming a comfortable role as observer in the setting. It is difficult to take notes while participating, and you may need to wait to write down observations until after you have left the research site.

Role of a Nonparticipant Observer In some situations, you may not be familiar enough with the site and people to participate in the activities. A nonparticipant observer is an observer who visits a site and records notes without becoming involved in the activities

of the participants. The nonparticipant observer is an “outsider” who sits on the periphery or some advantageous place (e.g., the back of the classroom) to watch and record the phenomenon under study. This role requires less access than the participant role, and gatekeepers and individuals at a research site may be more comfortable with it. However, by not actively participating, you will remove yourself from actual experiences, and the observations you make may not be as concrete as if you had participated in the activities.

Changing Observational Roles In many observational situations, it is advantageous to shift or change roles, making it difficult to classify your role as strictly participatory or non- participatory. A changing observational role is one where researchers adapt their role to the situation. For example, you might first enter a site and observe as a nonparticipant, simply needing to “look around” in the early phases of research. Then you slowly become involved as a participant. Sometimes the reverse happens, and a participant becomes a nonparticipant. However, entering a site as a nonparticipant is a frequently used approach. After a short time, when rapport is developed, you switch to being a participant in the set- ting. Engaging in both roles permits you to be subjectively involved in the setting as well as to see the setting more objectively.

Here is an illustration in which a researcher began as a nonparticipant and changed into a participant during the process of observing:

One researcher studying the use of wireless laptop computers in a multicultural education methods class spent the first three visits to the class observing from the back row. He sought to learn the process involved in teaching the course, the instructor’s interaction with students, and the instructor’s overall approach to teaching. Then, on his fourth visit, students began using the laptop computers and the observer became a participant by teaming with a student who used the laptop from her desk to interact with the instructor’s Web site.

The Process of Observing

As we just saw in the discussion of different observational roles, the qualitative inquirer engages in a process of observing, regardless of the role. This general process is outlined in the following steps:

1. Select a site to be observed that can help you best understand the central phenom- enon. Obtain the required permissions needed to gain access to the site.

Ease into the site slowly by looking around; getting a general sense of the site; and taking limited notes, at least initially. Conduct brief observations at first, because you will likely be overwhelmed with all of the activities taking place. This slow entry helps to build rapport with individuals at the site and helps you assimilate the large amount of information.

At the site, identify who or what to observe, when to observe, and how long to observe. Gatekeepers can provide guidance as you make these decisions. The practical requirements of the situation, such as the length of a class period or the duration of the activity, will limit your participation.

Determine, initially, your role as an observer. Select from the roles of participant or nonparticipant during your first few observations. Consider whether it would be advantageous to change roles during the process to learn best about the individuals or site. Regardless of whether you change roles, consider what role you will use and your reasons for it.

Conductmultipleobservationsovertimetoobtainthebestunderstandingofthesiteand the individuals. Engage in broad observation at first, noting the general landscape of activities and events. As you become familiar with the setting, you can begin to

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 215

216 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

narrow your observations to specific aspects (e.g., a small group of children interact- ing during reading time). A broad-to-narrow perspective is a useful strategy because of the amount of information available in an observation.

6. Design some means for recording notes during an observation. The data recorded during an observation are called fieldnotes. Fieldnotes are text (words) recorded by the researcher during an observation in a qualitative study. Examine the sample fieldnotes shown in Figure 7.4. In this example, the student-observer engaged in participant observation when the instructor asked the class to spend 20 minutes observing an art object that had been brought into the classroom. This object was not familiar to the students in the class. It was from Indonesia and had a square, bamboo base and a horsehair top. It was probably used for some religious activities. This was a good object to use for an observational activity because it could not be easily recognized or described. The instructor asked students to observe the object and record fieldnotes describing the object and reflecting on their insights, hunches, and themes that emerged during the observation.

As we see in Figure 7.4, one student recorded the senses—touch, sight, sound, and smell—of the object, recording thoughts every 5 minutes or so. Notice that the student’s fieldnotes show complete sentences and notations about quotes from other students. The notes in the right column indicate that this student is beginning to reflect on the larger ideas learned from the experiences and to note how other

| FIGURE 7.4 |

| Sample Fieldnotes from a Student’s Observation of an Art Object |

| —Art Object in the Classroom Setting: Classroom 306 Observer: J Role of Observer: Observer of object Time: 4:30 p.m., March 9, 2004 Length of Observation: 20 minutes Description of Object 4:35 Touch I taps on the base. Gritty wood, pieced p.m together unevenly. The object’s top feels like a cheap wig. The base was moved and the caning was tight. The wicker feels smooth. 4:40 Sight The object stands on four pegs that holds a square base. The base is decorated with scalloped carvings. The wood is a light, natural color and sanded smooth and finished. It is in the shape of a pyramid, cropped close at the bottom on the underside. 4:50 Sound Students comment as they touched the object, “Oh, that’s hair?” Is it securely fastened?” A slight rustling is heard from brushing the bristles . . .” 5:02 The object smells like roof-dry slate. It is odorless. But it has a musty, dusty scent to the top half, and no one wants to sniff it. (insights, hunches, themes) –Many students touch the object—most walk up slowly, cautiously. –Several good analogies come to mind. –This object is really hard to describe—perhaps I should use dimensions? But it has several parts. –Pickup on good quotes from the students. –“Sounds” could definitely be one of my themes! –This object seems to change smells the more I am around it—probably a dusty scent fits it best. Observational Fieldnotes Reflective Notes |

students in the class are reacting to the object. The heading at the top of the field-

notes records essential information about the time, place, and activities observed. 7. Consider what information you will record during an observation. For exam- ple, this information might include portraits of the participants, the physical setting, particular events and activities, and personal reactions (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998). In observing a classroom, for example, you may record activities by the teacher, the stu- dents, the interactions between the students and teacher, and the student-to-student

conversations. 8. Record descriptive and reflective fieldnotes. Descriptive fieldnotes record a

description of the events, activities, and people (e.g., what happened). Reflec- tive fieldnotes record personal thoughts that researchers have that relate to their insights, hunches, or broad ideas or themes that emerge during the observation (e.g., what sense you made of the site, people, and situation).

9. Make yourself known, but remain unobtrusive. During the observation, be introduced by someone if you are an “outsider” or new to the setting or people. Be passive, be friendly, and be respectful of the people and site.

10. After observing, slowly withdraw from the site. Thank the participants and inform them of the use of the data and the availability of a summary of results when you complete the study.

Figure 7.5 summarizes the steps listed above in a checklist you might use to assess whether you are prepared to conduct an observation. The questions on this checklist represent roughly the order in which you might consider them before, during, and after the observation, but you can check off each question as you complete it.

Interviews

Equally popular to observation in qualitative research is interviewing. A qualitative inter- view occurs when researchers ask one or more participants general, open-ended ques- tions and record their answers. The researcher then transcribes and types the data into a computer file for analysis.

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 217

| FIGURE 7.5 |

| An Observational Checklist |

| _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Did you gain permission to study the site? Do you know your role as an observer? Do you have a means for recording fieldnotes, such as an observational protocol? Do you know what you will observe first? Will you enter and leave the site slowly, so as not to disturb the setting? Will you make multiple observations over time? _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Will you develop rapport with individuals at the site? Will your observations change from broad to narrow? Will you take limited notes at first? Will you take both descriptive as well as reflective notes? Will you describe in complete sentences so that you have detailed fieldnotes? Did you thank your participants at the site? |

218 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

In qualitative research, you ask open-ended questions so that the participants can best voice their experiences unconstrained by any perspectives of the researcher or past research findings. An open-ended response to a question allows the participant to cre- ate the options for responding. For example, in a qualitative interview of athletes in high schools, you might ask, “How do you balance participation in athletics with your school- work?” The athlete then creates a response to this question without being forced into response possibilities. The researcher often audiotapes the conversation and transcribes the information into words for analysis.

Interviews in qualitative research have both advantages and disadvantages. Some advantages are that they provide useful information when you cannot directly observe participants, and they permit participants to describe detailed personal information. Com- pared to the observer, the interviewer also has better control over the types of informa- tion received, because the interviewer can ask specific questions to elicit this information.

Some disadvantages are that interviews provide only information “filtered” through the views of the interviewers (i.e., the researcher summarizes the participants’ views in the research report). Also, similar to observations, interview data may be deceptive and provide the perspective the interviewee wants the researcher to hear. Another disadvan- tage is that the presence of the researcher may affect how the interviewee responds. Inter- viewee responses also may not be articulate, perceptive, or clear. In addition, equipment issues may be a problem, and you need to organize recording and transcribing equipment (if used) in advance of the interview. Also during the interview, you need to give some attention to the conversation with the participants. This attention may require saying little, handling emotional outbursts, and using icebreakers to encourage individuals to talk. With all of these issues to balance, it is little wonder inexperienced researchers express surprise about the difficulty of conducting interviews.

Types of Interviews and Open-Ended Questions on Questionnaires

Once you decide to collect qualitative interviews, you next consider what form of inter- viewing will best help you understand the central phenomenon and answer the questions in your study. There are a number of approaches to interviewing and using open-ended questions on questionnaires. Which interview approach to use will ultimately depend on the accessibility of individuals, the cost, and the amount of time available.

One-on-One Interviews The most time-consuming and costly approach is to conduct individual interviews. A popular approach in educational research, the one-on-one inter- view is a data collection process in which the researcher asks questions to and records answers from only one participant in the study at a time. In a qualitative project, you may use several one-on-one interviews. One-on-one interviews are ideal for interviewing participants who are not hesitant to speak, who are articulate, and who can share ideas comfortably.

Focus Group Interviews Focus groups can be used to collect shared understanding from several individuals as well as to get views from specific people. A focus group interview is the process of collecting data through interviews with a group of people, typically four to six. The researcher asks a small number of general questions and elicits responses from all individuals in the group. Focus groups are advantageous when the interaction among interviewees will likely yield the best information and when interview- ees are similar to and cooperative with each other. They are also useful when the time to collect information is limited and individuals are hesitant to provide information (some individuals may be reluctant to provide information in any type of interview).

When conducting a focus group interview, encourage all participants to talk and to take their turns talking. A focus group can be challenging for the interviewer who

lacks control over the interview discussion. Also, when focus groups are audiotaped, the transcriptionist may have difficulty discriminating among the voices of individuals in the group. Another problem with conducting focus group interviews is that the researcher often has difficulty taking notes because so much is occurring.

Let’s consider an example of a focus group interview procedure:

High school students, with the sponsorship of a university team of researchers, conducted focus group interviews with other students about the use of tobacco in several high schools (Plano Clark et al., 2001). In several interviews, two student interviewers—one to ask questions and one to record responses—selected six stu- dents to interview in a focus group. These focus group interviews lasted one-half hour and the interviewers tape-recorded the interview and took notes during the interview. Because the groups were small, the transcriptionist did not have difficulty transcribing the interview and identifying individual voices. At the beginning of the interview each student said his or her first name.

Telephone Interviews It may not be possible for you to gather groups of individuals for an interview or to visit one-on-one with single individuals. The participants in a study may be geographically dispersed and unable to come to a central location for an interview. In this situation, you can conduct telephone interviews. Conducting a telephone interview is the process of gathering data using the telephone and asking a small number of general questions. A telephone interview requires that the researcher use a telephone adaptor that plugs into both the phone and a tape recorder for a clear recording of the interview. One drawback of this kind of interviewing is that the researcher does not have direct contact with the participant. This causes limited communication that may affect the researcher’s ability to understand the interviewee’s perceptions of the phenomenon. Also, the process may involve substantial costs for telephone expenses. Let’s look at an example of a tele- phone interview procedure:

In a study of academic department chairpersons in colleges and universities, Creswell et al. (1990) conducted open-ended telephone interviews lasting 45 minutes each with 200 chairpersons located on campuses in the United States. They first obtained the permission of these chairpersons to participate in an interview through contacting them by letter. They also scheduled a time that would be convenient for the interviewee to participate in a telephone interview. Next, they purchased tape recorders and adaptors to conduct the interviews from office telephones. They asked open-ended questions such as “How did you prepare for your position?” The interviews yielded about 3,000 transcript pages. Analysis of these pages resulted in a report about how chairpersons enhance the professional development of faculty in their departments.

E-Mail Interviews Another type of interview useful in collecting qualitative data quickly from a geographically dispersed group of people. E-mail interviews consist of collecting open-ended data through interviews with individuals using computers and the Internet to do so. If you can obtain e-mail lists or addresses, this form of interviewing provides rapid access to large numbers of people and a detailed, rich text database for qualitative analysis. It can also promote a conversation between yourself as the researcher and the participants, so that through follow-up conversations, you can extend your understanding of the topic or central phenomenon being studied.

However, e-mail interviewing raises complex ethical issues, such as whether you have permission for individuals to participate in your interview, and whether you will protect the privacy of responses. In addition, it may be difficult, under some circumstances, to obtain

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 219

220 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

good lists of e-mail addresses that are current or the names of individuals who will be well suited to answer your questions. For example, how do you locate e-mail addresses for chil- dren under the age of 10, who probably do not have such an address? Despite these poten- tial shortcomings, e-mail interviewing as a form of collecting data will probably increase due to expanding technology. Consider this example of an open-ended e-mail survey:

Four researchers combined resources to develop an e-mail list of faculty who might be teaching courses in mixed methods research (Creswell, Tashakkori, Jensen, & Shapely, 2003). They began with an e-mail list of 31 faculty and sent an open-ended interview to these faculty, inquiring about their teaching practices. They asked,

for example, “Have you ever taught a course with a content of mixed methods research?” “Why do you think students enroll in a mixed methods course?” and “What is your general assessment of mixed methods teaching?” After receiving the e-mail survey, the participants answered each question by writing about their expe- riences, and sent the survey back using the “reply” feature of their e-mail program. This procedure led to a qualitative text database of open-ended responses from a large number of individuals who had experienced mixed methods research.

Open-Ended Questions on Questionnaires On questionnaires, you may ask some ques- tions that are closed ended and some that are open ended. The advantage of this type of questioning is that your predetermined closed-ended responses can net useful infor- mation to support theories and concepts in the literature. The open-ended responses, however, permit you to explore reasons for the closed-ended responses and identify any comments people might have that are beyond the responses to the closed-ended ques- tions. The drawback of this approach is that you will have many responses—some short and some long—to analyze. Also, the responses are detached from the context—the set- ting in which people work, play, and interact. This means that the responses may not represent a fully developed database with rich detail as is often gathered in qualitative research. To analyze open-ended responses, qualitative researchers look for overlapping themes in the open-ended data and some researchers count the number of themes or the number of times that the participants mention the themes. For example, a researcher might ask a closed-ended question followed by an open-ended question:

Please tell me the extent of your agreement or disagreement with this statement:

“Student policies governing binge drinking on campus should be more strict.” ___________ Do you strongly agree? ___________ Do you agree? ___________ Are you undecided?

___________ Do you disagree? ___________ Do you strongly disagree? Please explain your response in more detail.

In this example, the researcher started with a closed-ended question and five predeter- mined response categories and followed it with an open-ended question in which the participants indicate reasons for their responses.

Conducting Interviews

In all of the various forms of interviewing, several general steps are involved in conduct- ing interviews or constructing open-ended questionnaires:

1. Identify the interviewees. Use one of the purposeful sampling strategies discussed earlier in this chapter.

Determine the type of interview you will use. Choose the one that will allow you to best learn the participants’ views and answer each research question. Consider a telephone interview, a focus group interview, a one-on-one interview, an e-mail interview, a questionnaire, or some combination of these forms.

During the interview, audiotape the questions and responses. This will give you an accurate record of the conversation. Use adequate recording procedures, such as lapel microphone equipment (small microphones that are hooked onto a shirt or collar) for one-on-one interviewing, and a suitable directional microphone (one that picks up sounds in all directions) for focus group interviewing. Have an adequate tape recorder and telephone adapter for telephone interviews, and understand thor- oughly mail programs for e-mail interviewing.

Take brief notes during the interview. Although it is sound practice to audiotape the interview, take notes in the event the tape recorder malfunctions. You record these notes on a form called an interview protocol, discussed later in this chapter. Recog- nize that notes taken during the interview may be incomplete because of the diffi- culty of asking questions and writing answers at the same time. An abbreviated form for writing notes (e.g., short phrases followed by a dash) may speed up the process.

Locate a quiet, suitable place for conducting the interview. If possible, interview at a location free from distractions and choose a physical setting that lends it to audiotap- ing. This means, for example, that a busy teachers’ or faculty lounge may not be the best place for interviewing because of the noise and the interruptions that may occur.

Obtain consent from the interviewee to participate in the study. Obtain consent by having interviewees complete an informed consent form when you first arrive. Before starting the interview, convey to the participants the purpose of the study, the time the interview will take to complete, the plans for using the results from the interview, and the availability of a summary of the study when the research is completed.

Have a plan, but be flexible. During the interview, stick with the questions, but be flexible enough to follow the conversation of the interviewee. Complete the ques- tions within the time specified (if possible) to respect and be courteous of the par- ticipants. Recognize that a key to good interviewing is to be a good listener.

Use probes to obtain additional information. Probes are subquestions under each question that the researcher asks to elicit more information. Use them to clarify points or to have the interviewee expand on ideas. These probes vary from exploring the content in more depth (elaborating) to asking the interviewee to explain the answer in more detail (clarifying). Table 7.2 shows these two types of probes. The table uses a specific illustration to convey examples of both clarifying and elaborating probes.

Be courteous and professional when the interview is over. Complete the interview by thanking the participant, assuring him or her of the confidentiality of the responses, and asking if he or she would like a summary of the results of the study. Figure 7.6 summarizes good interviewing procedures in a checklist adapted from

Gay, Mills, and Airasian (2005). The questions on the checklist represent the order in which you might consider them before, during, and after the interview.

Let’s return to Maria, who needs to decide what data collection procedure to use. Because she has experience talking with students and fellow teachers, she decides inter- viewing would be best. She proceeds to conduct five interviews with students and five with teachers in her high school. After obtaining permission from the school district and the principal of her school, she must obtain permission from the students (and their parents or guardians) and the teachers. To select these individuals, she will purposefully sample individuals who can speak from different perspectives (maximal variation sam- pling). She realizes there are different groups in the school, such as the “athletes,” the “singers,” the “punkers,” the “class officers,” and the “cheerleaders.” She identifies one

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 221

222

PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

| TABLE 7.2 | ||

| Types of Probes Used in Qualitative Interviewing | ||

| Examples | ||

| Clarifying Probes | Elaborating Probes | |

| A question in the study asks, “What has happened since the event that you have been involved in?” Assume that the interviewee says, “Not much” or simply does not answer. | Probe areas | “Tell me more.” “Could you explain your response more?” “I need more detail.” “What does ‘not much’ mean?” |

| Comments to other students: “Tell me about discussions you had with other students.” | ||

| Role of parents: “Did you talk with your parents?” | ||

| Role of news media: “Did you talk with any media personnel?” | ||

| FIGURE 7.6 | ||

| A Checklist for Interviewing | ||

| _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Who will participate in your interviews? What types of interviews are best to conduct? Is the setting for your interview comfortable and quiet? If you are audiotaping, have you prepared and tested the equipment? Did you obtain consent from the participants to participate in the interview? Did you listen more and talk less during the interview? Did you probe during the interview? (ask to clarify and elaborate) Did you avoid leading questions and ask open-ended questions? Did you keep participants focused and ask for concrete details? Did you withhold judgments and refrain from debating with participants about their views? Were you courteous and did you thank the participants after concluding the interview? | ||

Source: Adapted from Gay, Mills, & Airasian, 2005.

student from each group, realizing that she will likely obtain diverse perspectives repre- senting complex views on the topic of weapon possession.

Next, she selects five teachers, each representing different subject areas, such as social studies, science, physical education, music, and drama. After that, she develops five open-ended questions, such as “How do weapons come into our school?” and “What types of weapons are in our school?” She needs to schedule interviews, conduct them, record information on audiotapes, take notes, and respect the views and rights of the students and faculty participating in the interviews.

As you read this procedure, what are its strengths and its limitations? List these strengths and weaknesses.

Documents

A valuable source of information in qualitative research can be documents. Documents consist of public and private records that qualitative researchers obtain about a site or participants in a study, and they can include newspapers, minutes of meetings, personal journals, and letters. These sources provide valuable information in helping researchers understand central phenomena in qualitative studies. They represent public and private documents. Examples of public documents are minutes from meetings, official memos, records in the public domain, and archival material in libraries. Private documents consist of personal journals and diaries, letters, personal notes, and jottings individuals write to themselves. Materials such as e-mail comments and Web site data illustrate both public and private documents, and they represent a growing data source for qualitative researchers.

Documents represent a good source for text (word) data for a qualitative study. They provide the advantage of being in the language and words of the participants, who have usually given thoughtful attention to them. They are also ready for analysis without the necessary transcription that is required with observational or interview data.

On the negative side, documents are sometimes difficult to locate and obtain. Infor- mation may not be available to the public. Information may be located in distant archives, requiring the researcher to travel, which takes time and can be expensive. Further, the documents may be incomplete, inauthentic, or inaccurate. For example, not all minutes from school board meetings are accurate, because board members may not review them for accuracy. In personal documents such as diaries or letters, the handwriting may be hard to read, making it difficult to decipher the information.

Collecting Documents

With so much variation in the types of documents, there are many procedures for col- lecting them. Here are several useful guidelines for collecting documents in qualitative research:

Identify the types of documents that can provide useful information to answer your qualitative research questions.

Consider both public (e.g., school board minutes) and private documents (e.g., per- sonal diaries) as sources of information for your research.

Once the documents are located, seek permission to use them from the appropriate individuals in charge of the materials.

If you ask participants to keep a journal, provide specific instructions about the pro- cedure. These guidelines might include what topics and format to use, the length of journal entries, and the importance of writing their thoughts legibly.

Once you have permission to use documents, examine them for accuracy, com- pleteness, and usefulness in answering the research questions in your study.

Record information from the documents. This process can take several forms, includ- ing taking notes about the documents or, if possible, optically scanning them so a text (or word) file is created for each document. You can easily scan newspaper sto- ries (e.g., on speeches by presidential candidates) to form a qualitative text database. Collecting personal documents can provide a researcher with a rich source of infor-

mation. For example, consider a study that used journals prepared by several women:

An important source for learning about women in superintendent positions is for them to keep a personal journal or diary of their experiences. A researcher asked three women superintendents to keep a diary for 6 months and record their reactions to being a woman in their capacity of conducting official meetings comprised primarily of men.

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 223

224 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research These journals were useful for learning about the working lives of women in educa-

tional settings.

Audiovisual Materials

The final type of qualitative data to collect is visual images. Audiovisual materials con- sist of images or sounds that researchers collect to help them understand the central phe- nomenon under study. Used with increasing frequency in qualitative research, images or visual materials such as photographs, videotapes, digital images, paintings and pictures, and unobtrusive measures (e.g., evidence deduced from a setting, such as physical traces of images such as footsteps in the snow; see Webb’s [1966] discussion about unobtru- sive measures) are all sources of information for qualitative inquiry. One approach in using photography is the technique of photo elicitation. In this approach, participants are shown pictures (their own or those taken by the researcher) and asked to discuss the con- tents. These pictures might be personal photographs or albums of historical photographs (see Ziller, 1990).

The advantage of using visual materials is that people easily relate to images because they are so pervasive in our society. Images provide an opportunity for the participants to share directly their perceptions of reality. Images such as videotapes and films, for exam- ple, provide extensive data about real life as people visualize it. A potential disadvantage of using images is that they are difficult to analyze because of the rich information (e.g., how do you make sense of all of the aspects apparent in 50 drawings by preservice teach- ers of what it is like to be a science teacher?). Also, you as a researcher may influence the data collected. In selecting the photo album to examine or requesting that a certain type of drawing be sketched, you may impose your meaning of the phenomenon on partici- pants, rather than obtain the participants’ views. When videotaping, you face the issues of what to tape, where to place the camera, and the need to be sensitive with camera-shy individuals.

Collecting Audiovisual Materials

Despite these potential problems, visual material is becoming more popular in qualitative research, especially with recent advances in technology. The steps involved in collecting visual material are similar to the steps involved in collecting documents:

Determine what visual material can provide information to answer research ques- tions and how that material might augment existing forms of data, such as interviews and observations.

Identify the visual material available and obtain permission to use it. This permis- sion might require asking all students in a classroom, for example, to sign informed consent forms and to have their parents sign them also.

Check the accuracy and authenticity of the visual material if you do not record it yourself. One way to check for accuracy is to contact and interview the photogra- pher or the individuals represented in the pictures.

Collect the data and organize it. You can optically scan the data for easy storage and retrieval. To illustrate the use of visual material, look at an example in which the researcher

distributed cameras to obtain photographs:

A researcher gives Polaroid cameras to 40 male and 40 female fourth graders in a science unit to record their meaning of the environment. The participants are asked to take pictures of images that represent attempts to preserve the environment in

our society. As a result, the researcher obtains 24 pictures from each child that can be used to understand how young people look at the environment. Understand- ably, photos of squirrels and outside pets dominate the collection of pictures in this database.

WHAT PROCEDURES WILL BE USED TO RECORD DATA?

An essential process in qualitative research is recording data (Lofland & Lofland, 1995). This process involves recording information through research protocols, administer- ing data collection so that you can anticipate potential problems in data collection, and bringing sensitivity to ethical issues that may affect the quality of the data.

Using Protocols

As already discussed, for documents and visual materials, the process of recording informa- tion may be informal (taking notes) or formal (optically scanning the material to develop a complete computer text file). For observations and interviews, qualitative inquirers use specially designed protocols. Data recording protocols are forms designed and used by qualitative researchers to record information during observations and interviews.

An Interview Protocol

During interviewing, it is important to have some means for structuring the interview and taking careful notes. As already mentioned, audiotaping of interviews provides a detailed record of the interview. As a backup, you need to take notes during the interview and have the questions ready to be asked. An interview protocol serves the purpose of reminding you of the questions and it provides a means for recording notes. An inter- view protocol is a form designed by the researcher that contains instructions for the process of the interview, the questions to be asked, and space to take notes of responses from the interviewee.

Development and Design of an Interview Protocol To best understand the design and appearance of this form, examine the qualitative interview protocol used during a study of the campus reaction to a gunman who threatened students in a classroom (Asmussen & Creswell, 1995), shown in Figure 7.7. This figure is a reduced version of the actual pro- tocol; in the original protocol, more space was provided between the questions to record answers. Figure 7.7 illustrates the components that you might design into an interview protocol.

◆ It contains a header to record essential information about the interview, statements about the purpose of the study, a reminder that participants need to sign the con- sent form, and a suggestion to make preliminary tests of the recording equipment. Other information you might include in the header would be the organization or work affiliation of the interviewees; their educational background and position; the number of years they have been in the position; and the date, time, and location of the interview.

◆ Following this header are five brief open-ended questions that allow participants maximum flexibility for responding to the questions. The first question serves the purpose of an icebreaker (sometimes called the “grand tour” question), to relax the interviewees and motivate them to talk. This question should be easy to understand and cause the participants to reflect on experiences that they can easily discuss,

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 225

![]()

226

PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

| FIGURE 7.7 |

| Sample Interview Protocol |

| Interview Protocol |

| Project: University Reaction to a Gunman Incident Time of Interview: Date: Place: Interviewer: Interviewee: Position of Interviewee: [Describe here the project, telling the interviewee about (a) the purpose of the study, (b) the individuals and sources of data being collected, (c) what will be done with the data to protect the confidentiality of the interviewee, and (d) how long the interview will take.] [Have the interviewee read and sign the consent form.] [Turn on the tape recorder and test it.] Questions: 1. Please describe your role in the incident. 2. What has happened since the event that you have been involved in? 3. What has been the impact on the University community of this incident? 4. What larger ramifications, if any, exist from the incident? 5. Whom should we talk to to find out more about campus reaction to the incident? (Thank the individuals for their cooperation and participation in this interview. Assure them of the confidentiality of the responses and the potential for future interviews.) |

Source: Asmussen & Creswell, 1995.

such as “Please describe your role in the incident.” The final question on this

particular instrument helps the researcher locate additional people to study.

◆ The core questions, Questions 2 through 4, address major research questions in the study. For those new to qualitative research, you might ask more than four questions, to help elicit more discussion from interviewees and move through awkward moments when no one is talking. However, the more questions you ask, the more you are examining what you seek to learn rather than learning from the participant. There is often a fine line between your questions being too detailed or too general. A pilot test of them on a few participants can usually help you decide which ones to use.

◆ In addition to the five questions, you might use probes to encourage participants to clarify what they are saying and to urge them to elaborate on their ideas.

◆ You provide space between the questions so that the researcher can take short notes about comments made by interviewees. Your notes should be brief and you can develop an abbreviated form for stating them. The style for recording these notes varies from researcher to researcher.

◆ It is helpful for you to memorize the wording and the order of the questions to minimize losing eye contact. Provide appropriate verbal transitions from one ques- tion to the next. Recognize that individuals do not always respond directly to the question you ask: when you ask Question 2, for example, they may jump ahead and respond to Question 4.

◆ Closing comments remind you to thank the participants and assure them of the confidentiality of the responses. This section may also include a note to ask the interviewees if they have any questions, and a reminder to discuss the use of the data and the dissemination of information from the study. An Observational Protocol You use an observational protocol to record information during an observation, just as in interviewing. This protocol applies to all of the observational roles mentioned earlier. An observational protocol is a form designed by the researcher before data collection that is used for taking fieldnotes during an observation. On this form, researchers record a chronology of events, a detailed portrait of an individual or individuals, a picture or map of the setting, or verbatim quotes of individuals. As with interview protocols, the design and development of observational protocols will ensure that you have an organized means for recording and keeping observational fieldnotes. Development and Design of an Observational Protocol You have already seen a sample observational protocol in Figure 7.4, in which the student took notes about the art object in class. An observational protocol such as that one permits qualitative researchers to record information they see at the observation site. This information is both a descrip- tion of activities in the setting and a reflection about themes and personal insights noted during the observation. For example, examine again the sample observational protocol shown in Figure 7.4. This sample protocol illustrates the components typically found on a recording form in an observation:

◆ The protocol contains a header where you record information about the time, place, setting, and your observational role.

◆ You write in two columns following the header. These columns divide the page for recording into two types of data: a description of activities and a reflection about themes, quotes, and personal experiences of the researcher.

◆ The exact nature of this description may vary. Figure 7.4 illustrates possible topics for description. For example, you may include a description of the chronological order of events. This description is especially useful if the observer is examining a process or event. You may also describe the individuals, physical setting, events, and activities (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998). You may also sketch a picture of the site to facilitate remembering details of the setting for the final written report.

◆ Reflective notes record your experiences as a researcher, such as your hunches about important results and insights or emerging themes for later analysis. Think-Aloud About Observing I typically ask my graduate students to practice gathering qualitative data by observ- ing a setting. One of my favorite settings is the campus recreational center, where they can watch students learn how to climb the “wall.” It is an artificial wall created

CHAPTER 7 Collecting Qualitative Data 227

228 PART II The Steps in the Process of Research

so that students can learn how to rock climb. At this site, we typically find students who are learning how to climb the wall, and an instructor who is giving climbing les- sons. The wall itself is about 50 feet high and has strategically located handholds to assist the climbers. The wall contains several colored banners positioned for climbers to use to scale the wall. The objective is for a student to climb to the top of the wall and then rappel down.

Before the observation, my students always ask what they should observe. Here are the instructions that I give them:

◆Design an observational protocol using Figure 7.4 as a guide. ◆Go to the recreational center and to the base of the wall. Find a comfortable

place to sit on one of the benches in front of the wall, and then observe for about 10 minutes without recording information. Initially, simply observe and become acclimated to the setting.

◆After these 10 minutes, start focusing on one activity at the site. It may be a student receiving instructions about how to put on the climbing gear, students actually scaling the wall, or other students waiting their turn to climb.

◆Start recording descriptive fieldnotes. Consider a chronology of events, portraits of individuals, or a sketch of the site. To provide a creative twist to this exercise, I ask students to describe information about two of the following four senses: sight, sound, touch, or smell.

◆Also record reflective notes during the observation. ◆After 30 minutes, the observational period ends, and I ask students to write a brief

qualitative passage about what they observed, incorporating both their descriptive and their reflective fieldnotes. This final request combines data collection (observ- ing), data analysis (making sense of their notes), and report writing (trying to compose a brief qualitative research narrative).

WHAT FIELD AND ETHICAL ISSUES NEED TO BE ANTICIPATED?