PM-A5

Reading Three Perceptions of Project Cost

Three Perceptions of Project Cost12

D. H. Hamburger

Project cost seems to be a relatively simple expression, but “cost” is more than a four letter word. Different elements ofthe organization perceive cost differently, as the timing of project cost identification affects their particular organizational function. The project manager charged with on-time, on-cost, on-spec execution of a project views the “on cost” component of his responsibility as a requirement to stay within the allocated budget, while satisfying a given set ofspecified conditions (scope of work), within a required time frame (schedule). To most project managers this simply means a commitment to project funds in accordance with a prescribed plan (time-based budget). Others in the organization are less concerned with the commitment of funds. The accounting department addresses expense recognition related to a project or an organizational profit and loss statement. The accountant's ultimate goal is reporting profitability, while positively influencing the firm's tax liability. The comptroller (finance department) is primarily concerned with the organization's cash flow. It is that person's responsibility to provide the funds for paying the bills, and putting the unused or available money to work for the company.

To be an effective project manager, one must understand each cost, and also realize that the timing of cost identification can affect both project and corporate financial performance. The project manager must be aware of the different costperceptions and the manner in which they are reported. With this knowledge, the project manager can control more than the project's cost of goods sold (a function often viewed as the project manager's sole financial responsibility). The project manager can also influence the timing of cost to improve cash flow and the cost of financing the work, in addition to affecting revenue and expense reporting in the P&L statement.

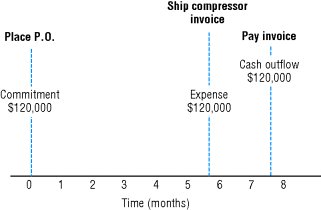

Three Perceptions of CostTo understand the three perceptions of cost—commitments, expenses, and cash flow—consider the purchase of a major project component. Assume that a $120,000 compressor with delivery quoted at six months was purchased. Figure 1 depicts the order execution cycle. At time 0 an order is placed. Six months later the vendor makes two shipments, a large box containing the compressor and a small envelope containing an invoice. The received invoice is processed immediately, but payment is usually delayed to comply with corporate payment policy (30, 60, 90, or more days may pass before a check is actually mailed to the vendor). In this example, payment was made 60 days after receipt of the invoice or 8 months after the order for the compressor was given to the vendor.

Figure 1 Three perceptions of project cost.

Commitments—The Project Manager's ConcernPlacement of the purchase order represents a commitment to pay the vendor $120,000 following satisfactory delivery ofthe compressor. As far as the project manager is concerned, once this commitment is made to the vendor, the available funds in the project budget are reduced by that amount. When planning and reporting project costs the project manager deals with commitments. Unfortunately, many accounting systems are not structured to support project cost reporting needs and do not identify commitments. In fact, the value of a purchase order may not be recorded until an invoice is received. This plays havoc with the project manager's fiscal control process, as he cannot get a “handle” on the exact budget status at a particular time. In the absence of a suitable information system, a conscientious project manager will maintain personal (manual or computer) records to track his project's commitments.

Expenses—The Accountant's ConcernPreparation of the project's financial report requires identification of the project's revenues (when applicable) and all project expenses. In most conventional accounting systems, expenses for financial reporting purposes are recognized upon receipt of an invoice for a purchased item (not when the payment is made—a common misconception). Thus, the compressor would be treated as an expense in the sixth month.

In a conventional accounting system, revenue is recorded when the project is completed. This can create serious problems in a long-term project in which expenses are accrued during each reporting period with no attendant revenue, and the revenue is reported in the final period with little or no associated expenses shown. The project runs at an apparent loss in each of the early periods and records an inordinately large profit at the time revenue is ultimately reported—the final reporting period. This can be seriously misleading in a long-term project which runs over a multi-year period.

To avoid such confusion, most long-term project P&L statements report revenue and expenses based on a “percentage of completion” formulation. The general intent is to “take down” an equitable percentage of the total project revenue (approximately equal to the proportion of the project work completed) during each accounting period, assigning an appropriate level of expense to arrive at an acceptable period gross margin. At the end of each accounting year and at the end of the project, adjustments are made to the recorded expenses to account for the differences between actual expenses incurred and the theoretical expenses recorded in the P&L statement. This can be a complex procedure. The misinformed or uninformed project manager can place the firm in an untenable position by erroneously misrepresenting the project's P&L status; and the rare unscrupulous project manager can use an arbitrary assessment of the project's percentage of completion to manipulate the firm's P&L statement.

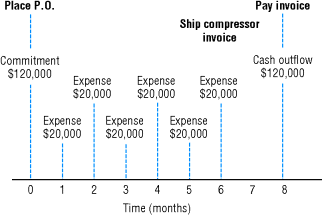

There are several ways by which the project's percentage of completion can be assessed to avoid these risks. A typical method, which removes subjective judgments and the potential for manipulation by relying on strict accounting procedures, is to be described. In this process a theoretical period expense is determined, which is divided by the total estimated project expense budget to compute the percentage of total budget expense for the period. This becomes the project's percentage of completion which is then used to determine the revenue to be “taken down” for the period. In this process, long delivery purchased items are not expensed on receipt of an invoice, but have the value of their purchase order prorated over the term of order execution. Figure 2 shows the $120,000 compressor in the example being expensed over the six-month delivery period at the rate of $20,000 per month.

Figure 2 Percentage of completion expensing.

Cash Flow—The Comptroller's ConcernThe comptroller and the finance department are responsible for managing the organization's funds, and also assuring the availability of the appropriate amount of cash for payment of the project's bills. Unused funds are put to work for the organization in interest-bearing accounts or in other ventures. The finance department's primary concern is in knowing when funds will be needed for invoice payment in order to minimize the time that these funds are not being used productively. Therefore, the comptroller really views project cost as a cash outflow. Placement of a purchase order merely identifies a future cash outflow to the comptroller, requiring no action on his part. Receipt of the invoice generates a little more interest, as the comptroller now knows that a finite amount of cash will be required for a particular payment at the end of a fixed period. Once a payment becomes due, the comptroller provides the funds, payment is made, and the actual cash outflow is recorded.

It should be noted that the compressor example is a simplistic representation of an actual procurement cycle, as vendor progress payments for portions of the work (i.e., engineering, material, and delivery) may be included in the purchase order. In this case, commitment timing will not change, but the timing of the expenses and cash outflow will be consistent with the agreed-upon terms of payment.

The example describes the procurement aspect of project cost, but other project cost types are treated similarly. In the case of project labor, little time elapses between actual work execution (a commitment), the recording of the labor hours on a time sheet (an expense), and the payment of wages (cash outflow). Therefore, the three perceptions of cost are treated as if they each occur simultaneously. Subcontracts are treated in a manner similar to equipment purchases. A commitment is recorded when the subcontract is placed and cash outflow occurs when the monthly invoice for the work is paid. Expenses are treated in a slightly different manner. Instead of prorating the subcontract sum over the performance period, the individual invoices for the actual work performed are used to determine the expense for the period covered by each invoice.

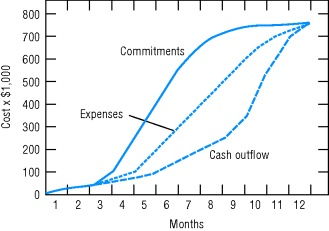

Thus the three different perceptions of cost can result in three different time-based cost curves for a given projectbudget. Figure 3 shows a typical relationship between commitments, expenses, and cash outflow. The commitment curve leads and the cash outflow curve lags, with the expense curve falling in the middle. The actual shape and the degree of lag/lead between the curves are a function of several factors, including: the project's labor, material, and subcontract mix; the firm's invoice payment policy; the delivery period for major equipment items; subcontract performance period and the schedule of its work; and the effect of the project schedule on when and how labor will be expended in relation to equipment procurement.

Figure 3 Three perceptions of cost.

The conscientious project manager must understand these different perceptions of cost and should be prepared to plan and report on any and all approaches required by management. The project manager should also be aware of the manner in which the accounting department collects and reports “costs.” Since the project manager's primary concern is in the commitments, he or she should insist on an accounting system which is compatible with the project's reporting needs. Why must a project manager resort to a manual control system when the appropriate data can be made available through an adjustment in the accounting department's data processing system?

Putting Your Understanding of Cost to WorkMost project managers believe that their total contribution to the firm's profitability is restricted by the ability to limit and control project cost, but they can do much more. Once the different perceptions of cost have been recognized, the project manager's effectiveness is greatly enhanced. The manner in which the project manager plans and executes the project can improve company profitability through influence on financing expenses, cash flow, and the reporting ofrevenue and expenses. To be a completely effective project manager one must be totally versed in the cost accounting practices which affect the firm's project cost reporting.

Examination of the typical project profit & loss statement (see Table 1) shows how a project sold for profit is subjected to costs other than the project's costs (cost of goods sold). The project manager also influences other areas of cost as well, addressing all aspects of the P&L to influence project profitability positively.

TABLE 1Typical Project Profit & Loss Statement

| Revenue (project sell price) | $1,000,000 |

| (less) cost of goods sold (project costs) | ($ 750,000) |

| Gross margin | $ 250,000 |

| (less) selling, general & administrative expenses | ($ 180,000) |

| Profit before interest and taxes | $ 70,000 |

| (less) financial expense | ($ 30,000) |

| Profit before taxes | $ 40,000 |

| (less) taxes | ($ 20,000) |

| Net profit | $ 20,000 |

Specific areas of cost with examples of what a project manager can do to influence cost of goods sold, interest expense, tax expense, and profit are given next.

Cost of Goods Sold (Project Cost)Evaluation of alternate design concepts and the use of “trade-off” studies during the development phase of a projectcan result in a lower project cost, without sacrificing the technical quality of the project's output. The application ofvalue engineering principles during the initial design period will also reduce cost. A directed and controlled investment in the evaluation of alternative design concepts can result in significant savings of project cost.

Excessive safety factors employed to ensure “on-spec” performance should be avoided. Too frequently the functional members of the project team will apply large safety factors in their effort to meet or exceed the technical specifications. The project team must realize that such excesses increase the project's cost. The functional staff should be prepared to justify an incremental investment which was made to gain additional performance insurance. Arbitrary and excessive conservatism must be avoided.

Execution of the project work must be controlled. The functional groups should not be allowed to stretch out the project for the sake of improvement, refinement, or the investigation of the most remote potential risk. When a functional task has been completed to the project manager's satisfaction (meeting the task's objectives), cut off further spending to prevent accumulation of “miscellaneous” charges.

The project manager is usually responsible for controlling the project's contingency budget. This budget represents money that one expects to expend during the term of the project for specific requirements not identified at the projectonset. Therefore, these funds must be carefully monitored to prevent indiscriminate spending. A functional group's need for a portion of the contingency budget must be justified and disbursement of these funds should only be made after the functional group has exhibited an effort to avoid or limit its use. It is imperative that the contingency budget be held for its intended purpose. Unexpected problems will ultimately arise, at which time the funds will be needed. Use of this budget to finance a scope change is neither advantageous to the project manager nor to management. The contingency budget represents the project manager's authority in dealing with corrections to the project work. Management must be made aware of the true cost of a change so that financing the change will be based on its true value (cost-benefit relationship).

In the procurement of equipment, material, and subcontract services, the specified requirements should be identified and the lowest priced, qualified supplier found. Adequate time for price “shopping” should be built into the projectschedule. The Mercury project proved to be safe and successful even though John Glenn, perched in the Mercury capsule atop the Atlas rocket prior to America's first earth orbiting flight, expressed his now famous concern that “all this hardware was built by the low bidder.” The project manager should ensure that the initial project budget is commensurate with the project's required level of reliability. The project manager should not be put in the position ofhaving to buy project reliability with unavailable funds.

Procurement of material and services based on partially completed drawings and specifications should be avoided. The time necessary for preparing a complete documentation package before soliciting bids should be considered in the preparation of the project schedule. Should an order be awarded based on incomplete data and the vendor then asked to alter the original scope of supply, the project will be controlled by the vendor. In executing a “fast track” project, the project manager should make certain that the budget contains an adequate contingency for the change orders which will follow release of a partially defined work scope.

Changes should not be incorporated in the project scope without client and/or management approval and the allocation of the requisite funds. Making changes without approval will erode the existing budget and reduce projectprofitability; meeting the project manager's “on-cost” commitment will become extremely difficult, if not impossible.

During periods of inflation, the project manager must effectively deal with the influence of the economy on the projectbudget. This is best accomplished during the planning or estimating stage of the work, and entails recognition ofplanning in an inflationary environment for its effect by estimating the potential cost of two distinct factors. First, a “price protection” contingency budget is needed to cover the cost increases that will occur between the time a vendor provides a firm quotation for a limited period and the actual date the order will be placed. (Vendor quotations used to prepare an estimate usually expire long before the material is actually purchased.) Second, components containing certain price-volatile materials (e.g., gold, silver, etc.) may not be quoted firm, but will be offered by the supplier as “price in effect at time of delivery.” In this case an “escalation” contingency budget is needed to cover the added expense that will accrue between order placement and material delivery. Once the project manager has established these inflation-related contingency budgets, the PM's role becomes one of ensuring controlled use.

The project's financial cost (interest expense) can be minimized by the project manager through the timing of order placement. Schedule slack time can be used to defer the placement of a purchase order so that the material is not available too early and the related cash outflow is not premature. There are several risks associated with this concept. Delaying an order too long could backfire if the desired material is unavailable when needed. Allowing a reasonable margin for error in the delivery cycle, saving some of the available slack time for potential delivery problems, will reduce this risk. Waiting too long to place a purchase order could result in a price increase which can more than offset the interest savings. It is possible to “lock-up” a vendor's price without committing to a required delivery date, but this has its limitations. If vendor drawings are a project requirement, an “engineering only” order can be placed to be followed by hardware release at the appropriate time. Deferred procurement which takes advantage of available slack time should be considered in the execution of all projects, especially during periods when the cost of money is excessively high.

Vendors are frequently used to help “finance the project” by placing purchase orders which contain extended payment terms. Financially astute vendors will build the cost of financing the project into their sell price, but only to the extent of remaining competitive. A vendor's pricing structure should be checked to determine if progress payments would result in a reduced price and a net project benefit. A discount for prompt payment should be taken if the discount exceeds the interest savings that could result from deferring payment.

Although frequently beyond the project manager's control, properly structured progress payment terms can serve to negate most or all project financial expenses. The intent is simple. A client's progress payment terms can be structured to provide scheduled cash inflows which offset the project's actual cash outflow. In other words, maintenance of a zero net cash position throughout the period of project execution will minimize the project's financial expense. In fact, a positive net cash position resulting from favorable payment terms can actually result in a project which creates interest income rather than one that incurs an interest expense. Invoices to the client should be processed quickly, to minimize the lost interest resulting from a delay in receiving payment.

Similarly, the project manager can influence receipt of withheld funds (retention) and the project's final payment to improve the project's rate of cash inflow. A reduction in retention should be pursued as the project nears completion. Allowing a project's schedule to indiscriminately slip delays project acceptance, thereby delaying final payment. Incurring an additional expense to resolve a questionable problem should be considered whenever the expense will result in rapid project acceptance and a favorable interest expense reduction.

On internally funded projects, where retention, progress payments, and other client-related financial considerations are not a factor, management expects to achieve payback in the shortest reasonable time. In this case, projectspending is a continuous cash outflow process which cannot be reversed until the project is completed and its anticipated financial benefits begin to accrue from the completed work. Unnecessary project delays, schedule slippages, and long-term investigations extend system startup and defer the start of payback. Early completion will result in an early start of the investment payback process. Therefore, management's payback goal should be considered when planning and controlling project work, and additional expenditures in the execution of the work should be considered if a shortened schedule will adequately hasten the start of payback.

On occasion, management will demand project completion by a given date to ensure inclusion of the project's revenue and profit within a particular accounting period. This demand usually results from a need to fulfill a prior financial performance forecast. Delayed project completion by only a few days could shift the project's entire revenue and profit from one accounting period to the next. The volatile nature of this situation, large sums of revenue and profit shifting from one period to the next, results in erratic financial performance which negatively reflects on management's ability to plan and execute their efforts.

To avoid the stigma of erratic financial performance, management has been known to suddenly redirect a carefully planned, cost-effective project team effort to a short-term, usually costly, crash exercise, directed toward a projectcompletion date, artificially necessitated by a corporate financial reporting need. Unfortunately, a project schedule driven by influences external to the project's fundamental objectives usually results in additional cost and reduces profitability.

In this particular case, the solution is simple if a percentage of completion accounting process can be applied. Partial revenue and margin take-down during each of the project's accounting periods, resulting from this procedure (rather than lump sum take-down in a single period at the end of the project, as occurs using conventional accounting methods) will mitigate the undesirable wild swings in reported revenue and profit. Two specific benefits will result. First, management's revenue/profit forecast will be more accurate and less sensitive to project schedule changes. Each project's contribution to the overall forecast will be spread over several accounting periods and any individual performance change will cause the shift of a significantly smaller sum from one accounting period to the next. Second, a project nearing completion will have had 90–95 percent of its revenue/profit taken down in earlier periods, which will lessen or completely eliminate management pressure to complete the work to satisfy a financial reporting demand. Inordinate, unnecessary spending to meet such unnatural demands can thereby be avoided.

An Investment Tax Credit,13 a net reduction in corporate taxes gained from a capital investment project (a fixed percentage of the project's installed cost), can be earned when the project actually provides its intended benefit to the owner. The project manager should consider this factor in scheduling the project work, recognizing that it is not necessary to complete the entire project to obtain this tax benefit as early as possible. Failure to substantiate beneficial use within a tax year can shift this savings into the next tax year. The project manager should consider this factor in establishing the project's objectives, diligently working toward attainment by scheduling the related tasks to meet the tax deadline. Consideration should also be given to expenditures (to the extent they do not offset the potential tax savings) to reach this milestone by the desired date.

In managing the corporate P&L statement, the need to shift revenue, expenses, and profit from one tax period to the next often exists. By managing the project schedule (expediting or delaying major component procurements or shifting expensive activities), the project manager can support this requirement. Each individual project affords a limited benefit, but this can be maximized if the project manager is given adequate notice regarding the necessary scheduling adjustments.

Revenue/profit accrual based on percentage of completion can create a financial problem if actual expenses greatly exceed the project budget. In this case the project's percentage of completion will accumulate more quickly than justified and the project will approach a theoretical 100 percent completion before all work is done. This will “front load” revenue/profit take-down and will ultimately require a profit reversal at project completion. Some managers may find this desirable, since profits are being shifted into earlier periods, but most reputable firms do not wish to overstate profits in an early period which will have to be reversed at a later time. Therefore, the project manager should be aware of cost overruns and, when necessary, reforecast the project's “cost on completion” (increasing the projected cost and reducing the expected profit) to reduce the level of profit taken down in the early periods to a realistic level.

Cost is not a four letter word to be viewed with disdain by the project manager. It is a necessary element of the projectmanagement process which the project manager must comprehend despite the apparent mysteries of the accounting systems employed to report cost. The concept of cost is more than the expenses incurred in the execution of the projectwork: the manner in which cost is treated by the organization's functional elements can affect project performance, interest expenses, and profitability. Therefore, the conscientious project manager must develop a complete understanding of project cost and the accounting systems used to record and report costs. The project manager should also recognize the effect of the timing of project cost, and the differences between commitments, expenses, and cash flow. The project manager should insist on the accounting system modifications needed to accommodate project costreporting and control requirements. Once an appreciation for these concepts has been gained, the project manager can apply this knowledge towards positively influencing project and organizational profitability in all areas of cost through control of the project schedule and the execution of the project's work.

QuestionsWhat is the major point of the article?

How does the accountant view project costs?

How does the controller view project costs?

How does the project manager view project costs?

What other costs does the project manager need to be cognizant of? What actions should the PM take concerning these other costs?