EDU 371: Phonics Based Reading & Decoding week 2 DQ 1

6 Teaching Phonemic Awareness

Walk into Juanita’s kindergarten classroom at the beginning of any school day, and you will find a lot of singing and choral reading going on. Children sing favorite songs and reread familiar and favorite rhyming poems. Sometimes Juanita asks children to change the refrain of a song to emphasize different sounds. For example, in “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” the refrain “Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily” becomes “verrily . . .” or “cherrily. . . .” After reading the poems, Juanita asks children to name rhyming words from them and then to add other rhyming words. She also says individual sounds from a significant word from the poem and asks the children to name the word: “What is this word—j, a, k?”

Juanita’s students love the songs and poetry, but Juanita also understands that in order to be successful in phonics and reading, children need to learn how sounds work, so she extends her music and poetry activities into natural opportunities for children to play with and manipulate sounds.

It’s no problem to move from the singing of a lyric into drawing students’ attention to the sounds in the lyrics. In fact, I think it’s kind of fun, and I know the children enjoy it too. . . . At the beginning of the school year, I am amazed by the number of children who have trouble with sounds. But as we make playing with songs, rhymes, and sounds a part of our day, it’s not long before they all begin to hear the individual sounds in words. Kindergarten is a place for children to become ready for school and ready to learn to read. I think our work with sounds is really helping prepare them by showing them that words have sounds and that those sounds can be moved and changed.

Phonemic awareness, or what Juanita calls sound knowledge and sound play, refers to a person’s awareness of speech sounds smaller than a syllable and the ability to manipulate them through such tasks as blending and segmenting. Phonemic awareness is a key element in learning word recognition through phonics and overall reading. Literacy scholar Keith Stanovich (1994) calls phonemic awareness a superb predictor of early reading acquisition, “better than anything else that we know of, including IQ” (p. 284).

Phonemic awareness provides the foundation for learning phonics, the knowledge of letter-sound correspondences, which readers use to decode unknown words. Since readers must recognize, segment, and blend sounds that are represented by letters, phonemic awareness is a very important precondition for learning phonics as well as reading (Adams 1990; Ball and Blachman 1991; Bradley and Bryant 1983, 1985; Fielding-Barnsley 1997; Lundberg, Frost, and Peterson 1988; National Reading Panel 2000; Perfetti, Beck, Bell, and Hughes 1987; Stanovich 1986; Yopp 1992, 1995a, 1995b). Students who lack phonemic awareness are most at risk to experience difficulty in learning phonics and, more importantly, learning to read (Catts 1991; Maclean, Bryant, and Bradley 1987). Thus, success in phonics requires some degree of phonemic awareness. Indeed, the report of the prestigious Committee on the Prevention of Reading Difficulties in Young Children recommends that, among other instructional activities, “beginning readers need explicit instruction and practice that lead to an appreciation that spoken words are made up of small units of sound” (Snow, Burns, and Griffin 1998, p. 7). Similarly, in its position statement on phonemic awareness, the International Reading Association (1998), the leading professional literacy organization in the world, notes the importance of phonemic awareness and how it can easily be nurtured at home and school:

It is critical that teachers are familiar with the concept of phonemic awareness and that they know that there is a body of evidence pointing to a significant relation between phonemic awareness and reading acquisition. . . . Many researchers suggest that the logical translation of the research to practice is for teachers of young children to provide an environment that encourages play with spoken language as part of the broader literacy program. Nursery rhymes, riddles, songs, poems, and read-aloud books that manipulate sounds may be used purposefully to draw young learners’ attention to the sounds of spoken language. (p. 6)*

* Reprinted with the permission of the International Reading Association.

However, the Association’s statement further notes that 20 percent of young children have not attained sufficient phonemic awareness to profit from phonics instruction by the middle of first grade. For these children we need to go beyond the “natural.” As the Association notes, we must

promote action that is direct, explicit, and meaningful. . . . We feel we can reduce this 20% figure by more systematic instruction and engagement with language early in students’ home, preschool, and kindergarten classes. We . . . can reduce this figure even further through early identification of students who are outside the norms of progress in phonemic awareness development, and through the offering of intensive programs of instruction. (p. 6)

The National Reading Panel (2000) reviewed research about the importance of phonemic awareness and about ways to teach it productively. With regard to importance, the NRP report says, “Correlational studies have identified phonemic awareness and letter knowledge as the two best school-entry predictors of how well children will learn to read during their first two years in school” (p. 2–1). This makes sense. Children who come to school with well-developed phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter names have probably had lots of preschool language and literacy experiences, which provide a firm foundation for subsequent reading achievement. The NRP also found that phonemic awareness instruction helped students learn to decode unfamiliar words, also logical given the relationship between phonemic awareness and phonics.

Several instructional guidelines can be derived from the National Reading Panel:

Focus on one or two types of phoneme manipulation at one time.

Assess before teaching; many children may not need instruction.

Teach children in small groups.

Keep sessions brief (only a total of 20 hours over an entire year).

Make activities as “relevant and exciting as possible so that the instruction engages children’s interest and attention in a way that promotes optimal learning” (p. 2‑7).

Most children develop phonemic awareness naturally through everyday play with language sounds, from reciting nursery rhymes and childhood poems, from chanting and creating jump rope rhymes, from singing songs (e.g., “I’ve been working on the railroad; fee, fi, fiddly, I, oh”), and from simply talking with family members and friends. Through these opportunities to make and manipulate the sounds of language, children gradually develop phonemic awareness. By the time they enter kindergarten, this awareness of language sounds allows them to connect specific sounds with individual letters and letter patterns (i.e., phonics).

A significant number of children, however, enter school with insufficient awareness of language sounds. Some may have been plagued with chronic ear problems that make sound perception and manipulation difficult. Others may have had few opportunities to play with language through childhood rhymes and songs. For whatever reason, a fairly significant minority of young children entering school may not have sufficiently developed phonemic awareness to find success in phonics instruction. Difficulty perceiving sounds makes learning letter-sound correspondence and blending sounds into words—phonics—overwhelming and an early frustration in learning to read.

6.1 Assessing Phonemic Awareness

Because children’s levels of phonemic awareness vary at school entrance, assessment is critical. Fortunately an easy‑to‑use phonemic awareness assessment is available. The Yopp-Singer Test of Phonemic Segmentation (Yopp 1995b) is a set of 22 words that students segment into constituent sounds (see Figure 6.1 for our variation of the Yopp-Singer Test). For example, the teacher says back, and the student says the three separate sounds that make up back: b, a, k.

The assessment takes only minutes to administer, yet the child’s performance can provide an indication of his or her current awareness of language sounds, later success in reading, and important information to guide instruction. Phonemic awareness, as measured by the Yopp-Singer Test, is significantly correlated with students’ reading and spelling achievement through grade 6 ( Yopp 1995b). Clearly, this and related research (National Reading Panel 2000; Stanovich 1994) suggest that phonemic awareness must be considered when assessing young children and struggling readers.

Yopp reported that second-semester kindergarten students obtained a mean score of 12 on the test. Kindergartners who fall significantly below this threshold, say a score of 5 or below, should be provided additional opportunities to develop phonemic awareness, opportunities that fit well within a normal kindergarten classroom.

Figure 6.1 Test for Assessing Phonemic Awareness

Test of Phonemic Segmentation

Student’s name __________________________________ Date __________

Student’s age _________

Score (number correct) _________ Examiner _________________________

Directions: I’d like to play a sound game with you. I will say a word and I want you to break the word apart into its sounds. You need to tell me each sound in the word. For example, if I say “old,” you should say “/o/-/l/-/d/.” (Administrator: Be sure to say the sounds in the word distinctly. Do not say the letters.) Let’s try a few practice words.

Practice items: (Assist the child in segmenting these items as necessary. You may wish to use blocks to help demonstrate the segmentation of sounds.) kite, so, fat

Test items: (Circle those items that the student correctly segments; incorrect responses may be recorded on the blank line following the item.)

to ______

me ______

fight ______

low ______

he ______

vain ______

is ______

am ______

be ______

meet ______

jack ______

dock ______

lace ______

mop ______

this ______

jot ______

grow ______

nice ______

cat ______

shoe ______

bed ______

stay ______

Source: Adapted from Yopp (1995b).

The Yopp-Singer Test has implications beyond kindergarten as well. We routinely administer it in our reading center to elementary-level struggling readers, many of whom have difficulty with the assessment. We expect students at second grade or beyond to score 20 or better. And yet it is not unusual to find fifth- and sixth-grade students, frustrated in reading, who score between 10 and 15. We wonder if these older students’ struggles in reading began when they were asked to master phonics before they were developmentally ready to do so. Rather than being provided an alternative route to reading or the chance to develop phonemic awareness, they may have been forced down a road that they were unable to negotiate to begin with—more phonics, more intensive phonics. It is easy to imagine how these students became turned off to reading. While others read for pleasure and information, these students were stuck reading less and drilling more (Allington 1977, 1984, 1994), which in turn led to even less self-selected reading and further frustration in reading.

The Yopp-Singer Test of Phonemic Segmentation and our variation published here are valuable tools. Identifying students who lack phonemic awareness as early as possible may save them from years of frustration in reading.

6.2 Teaching and Nurturing Phonemic Awareness through Text Play and Writing

For most students, phonemic awareness is nurtured more than it is taught. Children learn language sounds as they talk, sing, and play at home. Informed teachers can nurture phonemic awareness in enjoyable, playful, and engaging ways at school, as well. Perhaps one of the most useful is simply to use rhymes, chants, and songs that feature play with language sounds. Children can read and reread nursery rhymes, jump rope chants, poetry, and songs. For example, playing with nursery rhyme lines such as the following will help children grasp the concept of the sound of d.

Dickery dickery dare, the pig flew up in the air . . .

Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle . . .

Diddle diddle dumpling, my son John . . .

And the tongue-twisting rhyme “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers . . .” will help children develop an awareness of p.

Jump rope chants, poems, and song lyrics can serve the same purpose as nursery rhymes. Griffith and Olson (1992) recommend that teachers read rhyming texts and other texts that play with sounds to students daily and help develop students’ sensitivity to sounds. (See Figure 6.2 for a list of texts for developing phonemic awareness.) Moreover, these texts can be altered to feature different language sounds (Yopp 1992). For example, the familiar refrain of “Ee‑igh, ee‑igh, oh” in “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” can become “Dee-igh, dee-igh, doh” to emphasize d.

Older students can accomplish the same tasks with more sophisticated texts. Poems, tongue twisters, popular song lyrics, and raps can be learned, altered, rewritten, and ultimately performed to emphasize language sounds.

Figure 6.2 Texts for Developing Phonemic Awareness

Adams, P. (2007). There was an old lady. Auburn, ME: Child’s Play International.

Anastasio, D. (1999). Pass the peas, please. Los Angeles: Lowell House.

Anderson, P. F. (1995). The Mother Goose pages. Dreamhouse Nursery Bookcase. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~pfa/dreamhouse/nursery/sources.html

Baer, G. (1994). Thump, thump, rat‑a‑tat-tat. New York: Harper and Row.

Barrett, J. (2001). Which witch is which? New York: Atheneum.

Bayor, J. (1984). A: My name is Alice. New York: Dial.

Benjamin, A. (1987). Rat‑a‑tat, pitter pat. New York: Cromwell.

Berger, S. (2001). Honk! Toot! Beep! New York: Scholastic.

Brown, M. W. (1996). Four fur feet. Mt. Pleasant, SC: Dell.

Buller, J. (1990). I love you, good night. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Butterworth, N. (1990). Nick Butterworth’s book of nursery rhymes. New York: Viking.

Bynum, J. (2002). Altoona Baboona. Orlando: Harcourt.

Cameron, P. (1961). “I can’t,” said the ant. New York: Coward-McCann.

Capucilli, A. (2001). Mrs. McTats and her houseful of cats. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Carter, D. (1990). More bugs in boxes. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cole, J. (1993). Six sick sheep. New York: HarperCollins.

DePaola, T. (1985). Tomie DePaola’s Mother Goose. New York: Putnam.

Dodd, L. (2000). A dragon in a wagon. Milwaukee, WI: Gareth Stevens.

Eagle, K. (2002). Rub a dub dub. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Ehlert, L. (2001). Top cat. Orlando: Harcourt.

Eichenberg, F. (1988). Ape in a cape. San Diego, CA: Harcourt.

Enderle, J. (2001). Six creepy sheep. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mill.

Galdone, P. (1968). Henny penny. New York: Scholastic.

Gordon, J. (1991). Six sleepy sheep. New York: Puffin.

Hawkins, C. and Hawkins, J. (1986). Top the dog. New York: Putnam.

Hennessey, B. G. (1990). Jake baked the cake. New York: Viking.

Hoberman, M. (2004). The eensy-weensy spider. New York: Little, Brown.

Hymes, L. and Hymes, J. (1964). Oodles of noodles. New York: Young Scott Books.

Kellogg, S. (1985). Chicken Little. New York: Mulberry Books.

Krauss, R. (1985). I can fly. New York: Golden Press.

Kuskin, K. (1990). Roar and more. New York: Harper Trophy.

Langstaff, J. (1985). Frog went a‑courting. New York: Scholastic.

Lansky, B. (1993). The new adventures of Mother Goose. Deerhaven, MN: Meadowbrook.

Lee, D. (1983). Jelly belly. Toronto, ON: Macmillan.

Leedy, L. (1989). Pingo the plaid panda. New York: Holiday House.

Lewis, K. (1999). Chugga-chugga choo-choo. New York: Hyperion.

Lewison, W. (1992). Buzz said the bee. New York: Scholastic.

Low, J. (1986). Mice twice. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Martin, B., Jr. and Archambault, J. (1989). Chicka chicka boom boom. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Marzollo, J. (1989). The teddy bear book. New York: Dial.

Marzollo, J. (1990). Pretend you’re a cat. New York: Dial.

O’Connor, J. (1986). The teeny tiny woman. New York: Random House.

Obligado, L. (1983). Faint frogs feeling feverish and other terrifically tantalizing tongue twisters. New York: Viking.

Ochs, C. P. (1991). Moose on the loose. Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Books.

Patz, N. (1983). Moses supposes his toeses are roses. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Pearson, M. (1999). Pickles in my soup. New York: Children’s Press.

Perez-Mercado, M. M. (2000). Splat! New York: Children’s Press.

Pomerantz, C. (1974). The piggy in the puddle. New York: Macmillan.

Pomerantz, C. (1987). How many trucks can a tow truck tow? New York: Random House.

Prelutsky, J. (1986). Read-aloud rhymes for the very young. New York: Knopf.

Provenson, A. and Provenson, M. (1977). Old Mother Hubbard. New York: Random House.

Purviance, S. and O’Shell, M. (1988). Alphabet Annie announces an all-American album. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Raffi. (1988). Down by the bay. New York: Crown.

Salisbury, K. (1997). My nose is a rose. Cleveland, OH: Learning Horizons.

Salisbury, K. (1997). There’s a bug in my mug. Cleveland, OH: Learning Horizons.

Scarry, R. (1970). Richard Scarry’s best Mother Goose ever. New York: Western.

Schwartz, A. (1972). Busy buzzing bumblebees and other tongue twisters. New York: HarperCollins.

Sendak, M. (1962). Chicken soup with rice. New York: HarperCollins.

Serfozo, M. K. (1988). Who said red? New York: Macmillan.

Seuss, Dr. (1957). The cat in the hat. New York: Random House.

Seuss, Dr. (1960). Green eggs and ham. New York: Random House.

Seuss, Dr. (1965). Fox in socks. New York: Random House.

Seuss, Dr. (1965). Hop on pop. New York: Random House.

Seuss, Dr. (1972). Marvin K. Mooney, will you please go now! New York: Random House.

Seuss, Dr. (1974). There’s a wocket in my pocket. New York: Random House.

Shaw, N. (1986). Sheep on a ship. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Shaw, N. (2006). Sheep in a jeep. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Showers, P. (1991). The listening walk. New York: Harper Trophy.

Slepian, J. and Seidler, A. (1988). The hungry thing. New York: Scholastic.

Trapani, I. (2006). Shoo fly. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Wadsworth, O. A. (1985). Over in the meadow. New York: Penguin.

Winthrop, E. (1986). Shoes. New York: Harper Trophy.

Yektai, N. (1987). Bears in pairs. New York: Macmillan.

Zemach, M. (1976). Hush, little baby. New York: E. P. Dutton.

For other texts for developing phonemic awareness see Griffith and Olson (1992), Ericson and Juliebo (1998), and Yopp (1995a).

Hinky Pinkies are a playful way to develop sound awareness. Hinky Pinkies are simply riddles with answers that are two or more rhyming words. To make one, begin with the rhyming word pair answer and then think of a riddle that describes it. For example, duck’s truck could be the answer to the riddle What vehicle does a quacker drive? Students love making and figuring out Hinky Pinkies. The Hinky Pinky idea can also focus on two or more words with the same initial sounds (alliterations). A wet pup, then, is a soggy doggy when the answer rhymes, but becomes a drenched dog when the game is changed to alliterations.

To succeed in these activities, students must attend to the sounds of language. Playing with language in this way develops sensitivity to sounds. In addition to songs and poems, many books feature sounds. Although the texts listed in Figure 6.2 are most appropriate for younger children, older students needing help in phonemic awareness could learn to read the books to younger buddies, thus developing their own and their younger partners’ phonemic awareness. Students can also write their own versions of the books simply by changing the emphasized sounds.

Writing in which students use their knowledge of sound-symbol correspondence, also known as invented or phonemic spelling, is a powerful way to develop both phonemic awareness and basic phonics knowledge (Clay 1985; Griffith and Klesius 1990; Morris 1998). When students attempt to write words using their knowledge of language sounds and corresponding letters, they segment, order, and blend sounds to make real words. Even if the words are not spelled conventionally, this type of writing provides students with unequaled practice in employing their understanding of sounds.

Invented spelling is not an end state in learning to write. Just as children move from babbling and incorrect pronunciation to full and correct pronunciation when learning to talk, children move rapidly from invented spelling to conventional spelling. By the late primary grades there is little if any difference in spelling errors of children taught to spell in a highly rigid and disciplined system and other children who are encouraged to invent spelling. In fact, one study showed that first-grade children encouraged to invent spellings were more fluent writers and better word recognizers than children who experienced a traditional spelling curriculum (Clarke 1988). Considering all the sound-symbol thinking that occurs when children invent their spelling, such results are to be expected.

6.3 Teaching and Nurturing Phonemic Awareness through More Focused Activities

For those 20 percent of children who have not yet developed sufficient phonemic awareness skills to benefit from phonics instruction, more specific instruction is needed. Yopp (1992) and the National Reading Panel (2000) have identified these conceptual levels of activity to develop phonemic awareness:

Sound matching

Sound isolation

Sound blending

Sound substitution

Sound segmentation

These levels provide a conceptual framework for planning and designing instruction that treats phonemic awareness comprehensively, in an easy‑to‑more-complex order that eventually leads to learning phonics.

Most of the activities can be presented as simple games for children to play with their teacher and with one another. They can be effective for English language learners (ELLs) who are developing phonemic awareness in English, especially if teachers offer the time and support that children need. As Daniel Meier (2004) says, “In learning aspects of phonology in a new language, children experience all over again the journey of developing an ear for the particular rhymes and intonation of words in a language, a process that takes time, discovery, and practice” (p. 23). Understanding common phonological differences between the child’s first language and English is also essential. For example, Spanish vowels, unlike their English counterparts, have single sounds (Helman 2005). Moreover, saying English sounds in isolation (e.g., duh, ah, guh) misrepresents the same sounds used in a word (e.g., dog), which may lead to additional confusion for ELL students (Meier 2004). So basic knowledge of language differences along with patience and support can assist teachers in helping ELL children develop phonemic awareness .

Sound Matching

Sound matching simply requires students to match a word or words to a particular sound. When a teacher asks students to think of words that begin with p, students are challenged to find words that match that sound. Having students think of the way they form their mouths to articulate individual sounds may help them form a more lasting concept of the sound. Sound matching can be extended to middle vowel sounds, ending sounds, rhyming words, and syllables. Familiar written words can be placed on a word wall (see Chapter 9) according to their beginning, middle, ending, or word family sounds.

Another sound-matching activity involves presenting students with three words, two of which have the same beginning sound—for example, bat, back, rack. Students must determine which two words have the same initial sound. This activity can also be played with middle and ending sounds, rhyming words, and words with differing numbers of syllables.

Sound Isolation

Sound isolation activities require students to determine the beginning, middle, or ending sounds in words. For example, the teacher may provide three words that begin with the same sound, pig, pot, pet, and ask students to tell the beginning sound ( Yopp 1992). The same procedure can be done for middle and ending sounds, as well as for word families or rimes. After students develop proficiency in determining initial sounds from similar words, they can isolate sounds from different words. For example, the teacher may ask, “What is the beginning [middle, ending] sound you hear in these words: bake, swim, dog, pin, that?”

Sound Blending

In sound-blending activities, students synthesize sounds in order to make a word—this is required when decoding words using phonics. Using a game-like or sing-song format, the teacher simply presents students with individual sounds and asks them to blend the sounds together to form a word. The teacher might, for example, say to the class, “I am thinking of a kind of bird and here are the sounds in its name: d, u, k” (Yopp 1992). Of course, the children should say duck. Teachers can make this task easier by presenting three pictures of birds and asking students to pick the one that represents the sounds. Students can eventually create their own questions and present their own sounds and riddles to classmates.

Sound Substitution

Sound substitution requires students to subtract, add, and substitute sounds from existing words. A question such as “What word do you get when you take the w off win?” requires students to segment sounds from words and then re‑blend using the remaining sounds. Similarly, sounds can be added to existing words to make up new words: “Add b to the beginning of us and what do you get?”

After adding and subtracting sounds from given words, students can try substituting sounds. Ask students to think what the names of their classmates might be if all their names began with a particular sound (Yopp 1992). If t were used as the new sound, Billy’s name would become Tilly, and Mary and Gary would have the same name—Tary. Substituting middle and ending sounds is also possible.

Sound Segmentation

Sound segmentation requires students to determine all the constituent sounds in a word. This may begin with simply segmenting words into onsets (the sounds that precede the vowel in a syllable) and rimes (the vowel and consonants beyond the vowel in a syllable; another name for word family). So stack would be segmented into st and ak. Later, students can segment words into their individual sounds. This time stack would be segmented into s, t, a, k. Be sure to begin with short, two-sound words at first (e.g., us, in, at).

The generic activities we describe here can easily be transformed into a variety of games, performances, and playful activities. Teachers should try to make these activities engaging and enjoyable for students. We’ve found that several short game-like sessions throughout the day keep children’s interest better than longer, more involved sessions. The activities can be shared with parents, even parents of preschoolers, so that they too may participate in their children’s development of phonemic awareness.

Turtle Talk

As children are developing phonemic awareness, they may find that individual language sounds are not readily apparent. They cannot see, touch, feel, or smell them. Although language sounds can be heard, our normal speech is generally fast—so fast that children may have difficulty identifying individual sounds in normal speech.

One way to help children hear language sounds more distinctly is to slow down our speech. This is what happens in the game called Turtle Talk ( Nicholson 2006). During a 10‑minute Turtle Talk session the teacher explains that turtles are slow creatures. They move slowly and if they could speak they would likely speak slowly as well. Then the teacher demonstrates how a turtle might talk—for example, she says the word c‑a‑t in a slow, drawn-out fashion, asking students to look at how she uses her mouth to make the words. She asks students if they are able to determine the word that she is saying. Then she asks students to say the word in the same way, paying attention to how they have to move their mouths to go from one sound to another. This routine continues through several words—m‑ou‑se, sh‑ou‑t, c‑l‑a‑p, and so on. These quick lessons (games) done on a regular basis will help students become aware that words are made up of individual sounds (sound isolation and segmenting) and that those sounds need to be blended (sound blending) together to make words.

A Routine that Adds Meaning

By the time children are in first grade, nearly all have developed sufficient phonemic awareness to benefit from phonics and decoding instruction. Those who continue to struggle, however, need additional instruction. With such students in mind, Smith, Walker, and Yellin (2004) have developed and tested an instructional routine that combines attention to whole, meaningful texts and phonemic awareness. The routine has six key steps:

Hold a shared reading of a predictable rhyming book (such as one listed in Figure 6.2).

Highlight rhyming words from the book. Write a few on a chart, and provide children with small cards containing the words.

Select several rime patterns or word families that appear in the rhyming words, and draw children’s attention to these. Provide small cards containing the rimes/word families, and ask children to spread these cards (and the rhyming words) out on their tables.

Reread the predictable book, drawing children’s attention to the rhymes and rimes. Ask them to hold their cards up when they hear words or word families.

Ask students to create new rhymes and rimes that fit the pattern from the book. Write their contributions on the board or chart paper.

Reread this newly generated book in small groups.

Smith (2002) tested this strategy with 76 struggling second-graders and found that it led to significant improvement on a standardized reading achievement test. Smith and colleagues (2004) concluded that results “support the importance of providing students with specific word-recognition strategies in the context of authentic reading and writing experiences” (p. 305).

Add a Degree of Concreteness

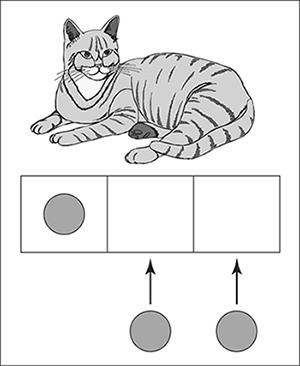

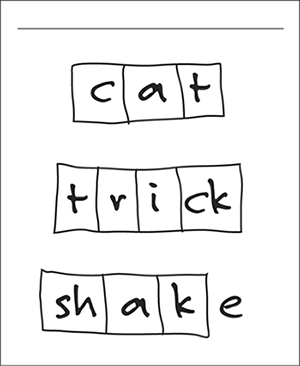

Sounds are abstract. Not only are sounds invisible, they can’t be held or made to stay. One way to make sound tasks more concrete is to use physical objects to represent the sounds, such as Elkonin boxes ( Griffith and Olson 1992). An Elkonin box is simply a series of boxes drawn on a sheet of paper, one for each phoneme in a given word. As students listen to words and hear discrete sounds, they push markers into the boxes, one for each sound. Later, as children become more familiar with written letters, they can write individual letters or letter combinations that represent individual sounds in the words (see Figures 6.3 and 6.4).

Other ways to make children’s learning concrete are also possible. For example, our friend Denise has a “morning stretch” each day. She stretches a large rubber band while inviting children to elongate common words, a process she says helps children learn to segment. Children can also write words or letters in shaving cream or sand, use individual whiteboards, or arrange magnetic letters on cookie sheets. Children find these activities interesting and enjoyable.

Figure 6.3 Example of Boxes Used for Hearing Sounds in Words

Figure 6.4 Example of Boxes Used for Hearing Sounds and Writing Letters

Sorting Sounds

When students sort or categorize items, they become actively involved in sophisticated analysis of what is to be learned. Indeed, scientists frequently sort or classify to make sense of their area of study. Sorting combines student constructivist learning with teacher-directed instruction (Bear, Invernizzi, Templeton, and Johnston 2012). Word and concept sorting offer opportunities for active student engagement, manipulation, control of the learning task, repeated practice of the learning content, and verbal explanation and reflection of the learning experience in order to deepen what has been learned (Templeton and Bear 2011). Needless to say we are big fans of sorting for students. Sorting can be used to help students develop phonemic awareness through picture sorts.

In a picture sort the teacher provides students with a preselected collection of simple pictures (online clip art is a great source of pictures; Words Their Way [Bear et al. 2012] provides another excellent collection). The pictures provide a concrete link to sounds embedded in the words depicted. Then, the teacher asks the students to sort the pictures by a particular category (e.g., words that begin with the t sound, words that end with the s sound, words that contain the at rhyme). As students sort the pictures, they are asked to say the word in the picture and identify the target sound. The teacher provides assistance as needed and engages the students in a discussion on sounds that are represented in the pictures and how the pictures might best be sorted. Students are then asked to explain their sort. As students become more adept at sorting, they can also create and explain their own categories.

In ConclusionLiteracy development involves more than phonics and phonemic awareness. Every day, children need to listen to the best children’s literature available, to explore word meanings, to write in their journals, and to work with language-experience stories. Predictable books, big books, poems, and stories should be read chorally, individually, and repeatedly in a supportive environment.

Nevertheless, research tells us that phonemic awareness is essential for phonics and reading success. Children benefit from phonics when they understand and can manipulate speech sounds. Teachers of young children and of older students who struggle in phonics and word recognition should develop curricula that are varied, stimulating, and authentic for teaching and developing students’ phonemic awareness.