EDU 371: Phonics Based Reading & Decoding week 2 assignment

5 Using Authentic Texts to Learn New Words and Develop Fluency

It was a rainy vacation day at the beach. Three-year-old Annie took a nap; her mom and her Aunt Nancy each grabbed a book and were engrossed in their reading when Annie awoke. After she rubbed the sleep from her eyes, she began trying to find a playmate. She asked her mom to play dolls; her mom said, “Sure. Just let me finish this chapter.” She asked Nancy to do watercolors with her; Nancy’s reply was the same. Annie looked around at the adults reading, went to her room, and came back with Bill Martin’s Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? (2010). She hopped up on the couch, opened her book, and began reading aloud.

Annie had heard Brown Bear many times and had read it along with her mother. The story’s pattern was easy for her to recall, so she read the words by remembering previous readings and by looking at the pictures for clues. For Annie, Brown Bear was a supportive and encouraging text. Support and encouragement are important concepts for all readers, but particularly for those who are just beginning to learn to read or who struggle with reading. They describe the instructional environment, the teacher’s role, and especially materials. Effective materials for beginners or struggling readers support and encourage them in their quest for meaning. Authentic texts that are predictable, like Brown Bear, work well because they enable even a beginning reader to predict, sample, and confirm—in short, do all the things a mature reader does. For our purposes in this book, an added benefit of authentic predictable text is that its familiar, dependable context provides a rich resource for word learning. Moreover, because predictable books are easy for children to read, they often read them repeatedly, which enhances fluency development.

Materials are predictable when children can easily determine what will come next—both what the author will say and how it will be said. Language-experience texts (see Chapter 13) are predictable because they reflect children’s own experiences in their own words. We describe many other sources of predictable text in this chapter, and we also offer some suggestions for using predictable texts to foster word learning. First, however, we explore some conceptions (and misconceptions) about what makes material easy to read.

5.1 What Is Easy to Read?

We can all agree that beginning and struggling readers need access to texts that they can easily read (Allington 2005). We may disagree, however, about what makes something easy to read. Is a highly structured text with controlled vocabulary easier to read than one that relies on natural language patterns? Some believe structure and control facilitate learning. Others, however (and we include ourselves here), see faults with this “go, Spot, go” type of writing. Simple language patterns are usually unfamiliar to children because they do not represent the natural oral language they hear in daily life; moreover, the vocabulary repetition is unnatural (when was the last time you said, “Look. Oh look, look, look” in conversation?). Stories written to fit a formula with certain words and restricted sentence patterns usually lack literary merit.

Heidi Mesmer (2006) surveyed 300 primary-level teachers who were members of the International Reading Association about the materials they used for beginning reading instruction. Most chose not to use decodable texts or controlled vocabulary readers (14 percent and 15 percent, respectively). Teachers said decodable text was “stilted, boring, and flat” (p. 411). Mesmer (2010) also explored the influence of text type (decodable vs. more natural language patterns) on first-grade children’s word recognition and fluency. Three times over the school year she assessed children who regularly read each type of text. Decoding results were inconclusive, but children who read texts with more natural language patterns read more fluently than their peers who read decodable texts.

For these reasons, among others, many educators rely on pattern books and other authentic, predictable texts for reading instruction. These texts contain distinct language patterns—naturally repetitive language, cumulating events, and/or use of rhythm or rhyme—all of which support children’s reading success. Moreover, the repetitive and predictable language patterns are an enjoyable way for children to play with sounds, words, phrases, and sentences.

5.2 Types of Authentic Text

In addition to dictated texts (see Chapter 13), several other types of authentic texts provide the support that beginning and struggling readers need to learn words—indeed, to learn to read. Following are a variety of suggestions we recommend for use with these readers.

Pattern Books

Many wonderful, new children’s pattern books are published each year. And because teachers continue to be interested in using pattern books for instruction, many old favorite titles are still available as well. These predictable books are easy for children to read because they quickly catch on to the pattern that the author used to write the book. Patterns usually involve repetitive language and/or repeating or cumulative episodes (as in The House That Jack Built). Rhyme may also be used. Figure 5.1 provides titles of dozens of pattern books. Many titles are appropriate for older struggling readers and English language learner (ELL) students as well as beginning readers. Rereading pattern books, first with support and later independently, is important for all three groups of readers (Barone 1996; Helman and Burns 2008; Rasinski, Padak, and Fawcett 2010).

Many pattern books are available from children’s book clubs in big book format, so teachers might strive to collect sets of children’s favorites that include both a big book version and several copies of little books. After the whole group works with the big book version, copies of the little books are eagerly sought for independent reading.

Figure 5.1 Predictable Pattern Books

Adams, P. (2007). This old man. New York: Grosset and Dunlap.

Aliki. (1991). My five senses. New York: Crowell.

Allenberg, J. and Allenberg, A. (1986). Each peach, pear, plum. New York: Viking Press.

Baer, G. (1994). Thump, thump, rat‑a‑tat-tat. New York: Harper and Row.

Barton, B. (1993). Dinosaurs, dinosaurs. New York: Crowell.

Brown, M. W. (1947). Goodnight moon. New York: Harper and Row.

Brown, M. W. (1949/1999). The important book. New York: HarperCollins.

Brown, R. (1992). A dark, dark tale. New York: Dial.

Campbell, R. (2007). Dear zoo. New York: Four Winds.

Carle, E. (1996). The grouchy ladybug. New York: Crowell.

Carle, E. (1997). Today is Monday. New York: Putnam.

Carle, E. (2009). The very hungry caterpillar. New York: Philomel.

Carle, E. and Iwamura, K (2003). Where are you going? To see my friend! New York: Orchard Books.

Chaconas, D. (2007). One little mouse. Glenview, IL: Pearson Scott Foresman.

Cowley, J. (2006). Mrs. Wishy-Washy. Bothell, WA: Wright Group.

Dillon, L. (2002). Rap a tap tap: Here’s Bojangles. New York: Blue Sky Press.

Dougherty, T. (2006). Days of the week. Minneapolis, MN: Picture Window Books.

Fox, M. (1992). Hattie and the fox. New York: Bradbury.

Galdone, P. (1986). The teeny tiny woman. New York: Clarion.

Galdone, P. (2006). The little red hen. New York: Scholastic.

Guarino, D. (1989). Is your mama a llama? New York: Scholastic.

Hayles, M. (2005). Pajamas anytime. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Hennessy, B. G. (1992). Jake baked the cake. New York: Viking.

Hoberman, M. (2000). The seven silly eaters. New York: Voyager.

Hoberman, M. (2007). A house is a house for me. New York: Puffin.

Hutchins, P. (1971). Rosie’s walk. New York: Macmillan.

Hutchins, P. (1989). The doorbell rang. New York: Greenwillow.

Hutchins, P. (1993). Titch. New York: Aladdin.

Janovitz, M. (2007). Look out, bird! New York: North-South.

Jonas, A. (1989). Color dance. New York: Greenwillow.

Jones, C. (1998). Old MacDonald had a farm. New York: Sandpiper.

Keats, E. J. (1999). Over in the meadow. New York: Scholastic.

Kraus, R. (2000). Whose mouse are you? New York: Macmillan.

Langstaff, J. (1991). Oh, a‑hunting we will go. New York: Atheneum.

Leuck, L. (1996). Sun is falling, night is calling. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Lies, B. (2006). Bats at the beach. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Martin, B. (2010). Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see? New York: Holt.

Martin, B. (2009). Chicka chicka boom boom. New York: Aladdin.

McKissack, F. (1986). Who is coming? Chicago: Children’s Press.

Neitzel, S. (1998). The bag I’m taking to Grandma’s. New York: Harper Trophy.

Numeroff, L. (1985). If you give a mouse a cookie. New York: Harper and Row.

Numeroff, L. (1994). If you give a moose a muffin. New York: HarperCollins.

Peek, M. (2006). Mary wore her red dress. New York: Clarion.

Raffi. (1988). Down by the bay. New York: Crown.

Ricci, C. (2004). Say “cheese”! New York: Simon Spotlight.

Sadler, M. (2006). Money, money, honey, bunny. New York: Random House.

Sendak, M. (1994). Chicken soup with rice. New York: Williams.

Seuss, Dr. (1960). Green eggs and ham. New York: Random House.

Seuss, Dr. (2005). Wet pet, dry pet, your pet, my pet. New York: Random House.

Shaw, N. (1992). Sheep on a ship. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Shaw, N. (2006). Sheep in a jeep. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Strickland, P. (2002). One bear, one dog. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Wescott, N. (1980). I know an old lady who swallowed a fly. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Williams, S. (2000). I went walking. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Wood, A. (1991). The napping house. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Wood, A. (2007). Silly Sally. San Diego: Harcourt.

Yolen, J. (2000). How do dinosaurs say goodnight? New York: Blue Sky Press.

Zelinsky, P. (1990). The wheels on the bus. New York: Dutton.

Some teachers also make their own big books. Materials needed for making a big book include chart paper (18” × 20” or larger) for the pages, stiff cardboard such as poster board for covers, a wide felt-tip marker for printing the text, materials for illustrations, and something, such as metal shower rings, to bind the finished product together. Individual pages might be laminated so that they will withstand repeated readings. Print should be large and legible from at least 15 feet.

Children can prepare illustrations for class-made big books. The first step in this process is for the teacher and students to read the story several times in order to decide where the page breaks should be. Pairs of learners can then read a portion of the text to be illustrated, talk about illustration possibilities, decide, and illustrate. All this activity involves reading and rereading the text—excellent fluency practice and a wonderful opportunity for word learning; children must also comprehend their individual pages in order to create appropriate illustrations. Moreover, children’s pride of ownership and accomplishment are a joy to see.

Songs, Finger Plays, and Other Rhymes

These are already staples in most primary classrooms. To make them into material for reading instruction, the teacher simply needs to make text copies of them, make the copies available for children to see, and use them instructionally. Since children already know the words, these items are particularly useful for developing concepts about print (e.g., What is a word?) and for learning sight words.

Some songs are used repeatedly throughout the school year, such as “Happy Birthday to You.” The teacher can make a copy of this song, leaving a blank where the child’s name is to be sung. The birthday child can create a name card to be affixed at the appropriate spot. After the class sings to the birthday child, the teacher can use the text of the song to help children learn new words.

Because of the repetitive nature of the language and the accompanying actions, children likewise learn finger plays rapidly. These, too, become reading material as soon as the teacher creates a large version of the rhyme for children to read. Some finger plays and other childhood rhymes have many stanzas, but they tend to be highly repetitive. A generic chart containing most of the stanza can be prepared, and word cards can be used to differentiate the stanzas. In the rhyme below, for example, the beginning blank is completed with word cards containing the numbers ten through one:

_______ little monkeys jumping on the bed.

One fell off and bumped its head.

Mama called the doctor, and the doctor said,

“No more monkeys jumping on the bed!”

As children chant the verse, they need to read the number cards to decide which goes next. In this way, they learn the number words by sight.

Jump rope rhymes and other childhood chants are likewise helpful for word learning. Teachers should keep their ears open while children are on the playground; opportunities for reading material will abound!

Nursery Rhymes and Poems

Many Mother Goose rhymes and other childhood poems are excellent choices for authentic, predictable texts. These short poems with strong rhythms and clear rhymes are easy for children to learn. As we note in Chapters 7 and 16, these texts are also quite useful for building students’ competencies in both phonics and fluency. Easy‑to‑read poems are located in most children’s poetry anthologies. Moreover, teachers and students can write their own rhymes and poems. Poetry reading should be a daily routine in classrooms.

Environmental Print

Children learn a great deal from their surroundings. Print in the environment, both outside of school and in the classroom, is a great source for incidental word learning. Children begin to recognize print in real-life contexts, such as road signs, fast-food logos, and the packaging on their favorite toys, at a very early age, as anyone who lives with a preschooler knows. To recognize environmental print, children appear to attend to shapes, colors, and logos, as well as print. Recognition of decontextualized print comes later, usually when children enter school (Lomax and McGee 1987). Nevertheless, children’s strong interest in environmental print makes it a good choice for reading material.

Although simply seeing environmental print and other predictable texts may be too indirect to foster precise word learning (Stahl and Murray 1993), teachers can focus children’s attention on the words in environmental print messages fairly easily. For example, children can look through old newspapers, magazines, and junk mail to find material to put into theme books about environmental print (Christie, Enz, and Vukelich 1997). Theme books can be created for such topics as soft drinks, sneakers, pizza, fast food, cereal, cookies, and professional sports teams. To encourage focus on the words and not just the logos, teachers can insert pages into the theme books that contain the words alone in standard print or type format. Many children enjoy guessing which words belong with which logos.

Labels, lists, schedules, directions, messages, and other forms of environmental print inside the classroom can also foster word learning. In general, we recommend using as much functional print as possible in the classroom. Children see and often must use these words daily, so they naturally learn them. Moreover, such a print-rich classroom shows children rather directly about the functions of writing and the value of the written word.

5.3 Using Authentic Text

Probably the best way to introduce authentic, predictable texts to children is through what Holdaway (1979) calls the “shared Book Experience,” an idea inspired by parents and children reading bedtime stories in a comfortable, relaxed manner. Translating this experience into classroom practice involves preparing an enlarged version of the text, since it is critical for the children to see the words as the teacher reads them. Teachers may use chart paper to make these enlarged texts; electronic versions can be projected using an LCD projector. We recommend that teachers prepare smaller versions of the texts, perhaps with room for children’s illustrations, so that each child can have an individual copy.

In general, pattern books or other types of authentic text should be read to children several times to allow children to learn them thoroughly. The next stage is to read the text with children in choral or antiphonal fashion (see Chapter 16). Many teachers pause before reading repetitive portions of the text; the children chime in, usually with gusto, to say the parts they know. Finally, children are invited to read the text alone. (See Chapter 16 for other ideas for repeated readings.) All this can be done over several days, if needed. This overall pattern, “I’ll read it to you. You read it with me. Now you read it alone,” provides the support that children need to decode the text successfully.

After children have learned the text, the teacher can begin to direct their attention to individual sentences, phrases, words, letters, and letter combinations. This natural progression from whole to part, which we have also described in other chapters, allows children to discover how smaller units of language work without distorting or disrupting the process of reading and enjoying the entire text. Moreover, it’s easy to help children see the value of what they learn about words and sounds because the new knowledge can be easily related back to the text. Thus, transfer, a critical element in word recognition instruction, is facilitated.

Guessing Games

Texts can be used for instruction that focuses on the conventions of print and other aspects of word learning in a guessing-game format. For example, the teacher can ask questions like these:

Where’s the title? How many words are in the title? Where’s the first word in the title? Where’s the last word? Who can circle all the words in the title?

Where’s the first word in the story? Where’s the last word? Where’s the first word in line _______? How many words are in the first sentence? How many words are in the last line?

Where does the first sentence begin? Where does it end? How can we tell where a sentence begins and where one ends? How many sentences are in our text? How many lines?

Who can find a [letter] in the text? Are there more [letter]s? Who can find a capital [letter]? A lowercase [letter]?

Who can find the word [a word with a featured word family]? How many words that contain the _______ family are in our text? What are they?

Who can find a word that has a [phonic element]? How many words that contain [phonic element] are in our text? What are they?

Who can find a two-syllable word? How many two-syllable words are there in our text?

Lessons like this focus children’s attention on the parts of written language—lines, sentences, words, letters, and phonic elements. Note too the variation in difficulty of the guessing-game questions. Some focus on very beginning print concepts (e.g., Who can circle all the words in the title? Who can find a lowercase [letter]?), and others are more advanced (e.g., How many words that contain [phonic element] are in our text? Who can find a two-syllable word?). Children enjoy this sort of guessing game; it’s also an easy way to differentiate instruction to accommodate different ability levels among individual children.

Children can use markers to circle or underline their responses to these questions on a second copy of the text. They can point with their fingers or use a pointer or flashlight. Some teachers use word whoppers, which are fly swatters with rectangles cut in them. Words of interest to children (or the teacher) can also be added to each student’s word bank (see Chapter 11) . However children respond, working with familiar and meaningful text provides support and allows them to discover relationships between the parts and the whole. And the multiple readings that occur naturally support both word learning and fluency development.

Word Sorts

Word sort activities (see Chapter 11) can also be used to direct children’s attention to the language of the texts. Consider, for example, the following Mother Goose rhyme:

Jelly on a plate, jelly on a plate

Wibble, wobble, wibble, wobble

Jelly on a plate.

Sausage in a pan, sausage in a pan

Frizzle, frazzle, frizzle, frazzle

Sausage in a pan

Baby on the floor, baby on the floor

Pick him up, pick him up

Baby on the floor.

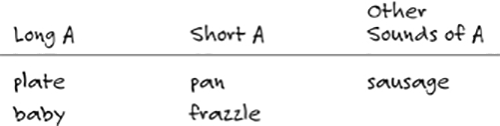

After the poem is enjoyed for its own sake, its words can be used to focus children’s attention on the sounds of long and short A. The teacher can ask children to circle all the words containing the letter A in the poem. Next, in pairs or groups of three, they can complete a closed word sort in which they put each A word into a category, as shown here:

Copy Change

Individuals or small groups can make their own versions of authentic, predictable texts, especially pattern books and poems. This writing activity is often called copy change because children use the author’s copy as a framework, but change it to reflect their own ideas. Simple pattern books, like Brown Bear, work well for introducing children to copy change. The teacher can simply read the book several times to children, eventually asking them to identify what the author “does over and over.” Some teachers write children’s ideas on the chalkboard so that they can refer to them later. Others prepare sheets with some of the text provided for children.

Little mouse, little mouse, what do you see?

I see a hungry cat looking at me.

Pitcher, pitcher, what do you see?

I see the batter looking at me.

Students thought about rhyming words and syllables as they wrote their own books. They also practiced writing sight words. Most important, they enjoyed the entire lesson and celebrated their authorship.

Songs can also be used for copy change activities. Here’s a version of “Yankee Doodle” that a struggling first-grader recently wrote (and performed) in our reading clinic.

Yankee Doodle went to town

Riding on a doggy

They got lost on their way

Because it was so foggy.

In this case the student used the original text as a scaffold, but at the same time had to attend to rhythm, rhyme, and meaning as she created her own version of this simple text.

Copy change activities encourage careful reading and listening so that children can discover, appreciate, and use the author’s words and language patterns. Children must also analyze the structure of the original text (Leu and Kinzer 1999). Best of all, students find it fun and satisfying to write stories or poems that are similar to those they have read and to share these new stories or poems with their classmates and families. All this practice promotes fluent, expressive reading.

Figure 5.2 Kevin’s Mother Goose Page

Other Independent Activities

Children can illustrate their copy change texts; they can also type their texts, one sentence per page, to make their own books. Figure 5.2 shows an example of an individual book Kevin made of the Mother Goose rhyme “One, two, three, four, five.” Cloze exercises (see Chapter 12) are also effective.

All instructional texts should be available for children to reread independently. Because of the support they have received during the repeated reading and study of the texts, children can usually read them alone or with peers. They take great pride in this accomplishment and are generally interested in reading the texts again and again. This success fosters positive attitudes toward reading and helps children develop good concepts of themselves as readers. Children also learn about the conventions of print, acquire sight vocabulary, practice word recognition strategies, and develop fluency as they practice with the texts; these findings hold for both beginning readers and ELL students (Barone 1996; Helman and Burns 2008; Kuhn 2004).

5.4 Just Good Books

Finally, we recommend good stories and lots of reading for students . Not only do good stories provide students with great opportunities for practicing their word recognition skills and strategies, they also make reading satisfying and exciting for students—they help to get students hooked on reading and hooked on books. We know that students who are voracious readers tend to be our best readers. Indeed, the National Assessment of Educational Progress results from 1992, 1994, 1998, and 2000 showed that fourth-graders who read the most at school and at home had the highest levels of reading achievement (National Center for Educational Statistics 2001). Thus, teachers need to know the very best reading materials available for students, even when the instructional focus is phonics and word recognition.

With the thousands of children’s books published every year, it’s difficult for teachers to become experts in instruction and experts in children’s literature at the same time. Fortunately, teachers can use several resources to help find great books for students to read. The primary resources, we think, are media specialists or librarians and other veteran teachers. These professionals are filled with knowledge about the very best books for students, books they know will turn kids on to reading. Media specialists and librarians, in particular, are trained to find books that students will enjoy. They read the professional materials that review, rate, and recommend books for children. If you are a new teacher, be sure to ask your school librarian and teacher colleagues to recommend books and other reading material, including online resources, for your students. You will find them most accommodating.

Book awards are another good resource for finding good books for children. The American Library Association (ALA) sponsors several awards for children’s literature each year, including the prestigious Caldecott (for illustrations in books) and Newbery (for best story) medals. But don’t limit yourself only to the winners. Caldecott and Newbery Honor Books didn’t win the awards but are still of exceptional merit. Other important annual awards include the Batchelder Award for best books translated into English and the Coretta Scott King Awards for African American authors, illustrators, and “new talent’’; both of these are also sponsored by the ALA. Current and past winners and Honor Books for all of these awards are located at the ALA website: http://www.ala.org/awardsgrants/. The Orbis Pictus Award for nonfiction books for children is sponsored by the National Council of Teachers of English (http://ncte.org). Many states also sponsor book awards. Children love reading books that have been recognized by others in their state.

Professional journals are also a valuable resource for teachers in search of good books. The Reading Teacher (RT), published by the International Reading Association (IRA) (1‑800-336-READ, www.reading.org), is one of the best. Many elementary and middle schools receive it. (If yours doesn’t, ask your principal to get a subscription or two for your school.) Published monthly during the school year, RT frequently features review columns, written by children’s literature and reading experts, on recently published books for students. RT also publishes Children’s Choices (October issue) and Teachers’ Choices (November issue). Children’s Choices reports on recently published books that children across the country rated as their favorites. Teachers’ Choices reports on favorite books of recent vintage from the teachers’ point of view. The IRA newspaper, Reading Today, also publishes book reviews. The Web is another outstanding resource for learning about children’s books.

Online bookstores such as http://www.barnesandnoble.com/ and http://www.amazon.com/ offer synopses and sometimes book reviews of selected titles. In fact, children can write and publish reviews of books they have read on these websites. The following list shows other handy Web resources for children’s book lists:

Association for Library Service to Children

www.ala.org/alsc/

Carol Hurst’s Children’s Literature Site

http://www.carolhurst.com

Children’s Literature Web Guide

www.ucalgary.ca/~dkbrown/index.html

The Internet Public Library (also includes many online texts for children to read)

http://www.ipl.org/div/kidspace/

Recommended Trade Books at the Ohio Literacy Resource Center

http://literacy.kent.edu/eureka/

5.5 Texts and Phonics

Our main reason for selecting or recommending books for children should be their literary quality. Is the book a good read? Will the reader find the text engaging? Will the material lead students to want to read more? As students read books of exceptional merit, they exercise their phonics and word study strategies in real life and satisfying contexts.

This issue of providing children with authentic practice opportunities is very important. In their discussion of phonics research, for example, the National Reading Panel (2000) concluded:

Programs that focus too much on the teaching of letter-sound relations and not enough on putting them to use are not likely to be very effective. In implementing systematic phonics instruction, educators must keep the end in mind and ensure that children understand the purpose of learning letter-sounds and are able to apply their skills in their daily reading and writing activities. (p. 2–96)

Authentic texts especially effective for providing this needed practice are a critical tool. Listed in Figure 5.3 (adapted from Trachtenburg 1990) are books that highlight particular vowel sounds. Figures 5.4 and 5.5 offer some resources for working with ELLs. Figure 5.4 mentions several easy bilingual series books, and Figure 5.5 lists single titles. After providing students with instruction in a particular vowel sound, introducing them to books associated with the relevant vowel will give them immediate practice in using their newfound knowledge in real reading.

Figure 5.3 Trade Books That Repeat Phonic Elements

Short a

Flack, M. (1997). Angus and the cat. New York: Doubleday.

Griffith, H. (1982). Alex and the cat. New York: Greenwillow.

Kent, J. (1971). The fat cat. New York: Scholastic.

Most, B. (1992). There’s an ant in Anthony. New York: William Morrow.

Robins, J. (1988). Addie meets Max. New York: Harper and Row.

Schmidt, K. (1985). The gingerbread man. New York: Scholastic.

Seuss, Dr. (1957). The cat in the hat. New York: Random House.

Long a

Aaredema, V. (1992). Bringing the rain to Kapiti Plain. New York: Dial.

Bang, M. (1987). The paper crane. New York: Greenwillow.

Byars, B. (1975). The lace snail. New York: Viking.

Henkes, K. (1996). Sheila Rae, the brave. New York: Greenwillow.

Hines, A. (1983). Taste the raindrops. New York: Greenwillow.

Short e

Aliki. (1996). Hello! Good-bye. New York: Greenwillow.

Ets, M. (1972). Elephant in a well. New York: Viking.

Galdone, P. (2006). The little red hen. New York: Scholastic.

Ness, E. (1974). Yeck eck. New York: Dutton.

Shecter, B. (1977). Hester the jester. New York: Harper and Row.

Thayer, J. (1975). I don’t believe in elves. New York: William Morrow.

Long e

Brown, M. W. (1996). Four fur feet. Mt. Pleasant, SC: Dell.

Keller, H. (1983). Ten sleepy sheep. New York: Greenwillow.

Martin, B. (2010). Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see? New York: Holt.

Oppenheim, J. (1967). Have you seen trees? New York: Young Scott Books.

Reiser, L. (1996). Beachfeet. New York: Greenwillow.

Shaw, N. (1995). Sheep out to eat. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Shaw, N. (2006). Sheep in a jeep. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Short i

Hutchins, P. (1993). Titch. New York: Aladdin.

Kessler, C. (1997). Konte Chameleon: Fine, fine, fine. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills.

Lewis T. (1981). Call for Mr. Sniff. New York: Harper and Row.

Lobel, A. (1988). Small pig. New York: Harper and Row.

McPhail, D. (1992). Fix‑it. New York: Dutton.

Robins, J. (1986). My brother, Will. New York: Greenwillow.

Long i

Cameron, J. (1979). If mice could fly. New York: Atheneum.

Cole, S. (1985). When the tide is low. New York: Lothrop, Lee and Shepard.

Gelman, R. (1976). Why can’t I fly? New York: Scholastic.

Hazen, B. (1983). Tight times. New York: Viking.

Short o

Dunrea, O. (1985). Mogwogs on the march! New York: Holiday House.

Emberley, B. (1972). Drummer Hoff. New York: Prentice-Hall.

McKissack, P. (1986). Flossie & the fox. New York: Dial.

Seuss, Dr. (1965). Fox in socks. New York: Random House.

Long o

Cole, B. (2001). The giant’s toe. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gerstein, M. (1984). Roll over! New York: Crown.

Johnston, T. (1972). The adventures of Mole and Troll. New York: Putman.

Johnston, T. (1977). Night noises and other Mole and Troll stories. New York: Putnam.

Hamanaka, S. (1997). The hokey pokey. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Pinczes, E. (1997). One hundred hungry ants. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Short u

Cooney, N. (1987). Donald says thumbs down. New York: Putnam.

Lorenz, L. (1982). Big Gus and little Gus. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Marshall, J. (2001). The cut-ups at Camp Custer. New York: Puffin.

Udry, J. (2001). Thump and plunk. New York: Harper and Row.

Long u

Lobel, A. (1966). The troll music. New York: Harper and Row.

Medearis, A. (1997). Rum‑a‑tum-tum. New York: Holiday House.

Segal, L. (1977). Tell me a Trudy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Books and Poetry Anthologies That Feature Several Vowel and Consonant Sounds

Carle, E. (1999). Eric Carle’s animals animals. New York: Philomel.

de Regniers, B. S., et al. (1988). Sing a song of popcorn: Every child’s book of poems. New York: Scholastic.

Lansky, B. (1996). Poetry party. Deephaven, MN: Meadowbrook.

Lansky, B. (1999). The new adventures of Mother Goose: Gentle rhymes for happy times. New York: Atheneum.

Lobel, A. (Ed). (2003). The Arnold Lobel book of Mother Goose. New York: Knopf.

Moss, L. (2000). Zin! Zin! Zin! A violin. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Slier, D. (Ed.). (2003). Make a joyful sound: Poems for children by African-American poets. New York: Checkerboard Press.

Source: Adapted from P. Trachtenburg (1990). Using children’s literature to enhance phonics instruction. The Reading Teacher, 43, 648–654.

Figure 5.4 Spanish-English Bilingual Series Books

Barron’s I Can Read Spanish series (also available in French): George the Goldfish; Get Dressed, Robbie; Goodnight Everyone; Happy Birthday; Hurry Up, Molly; I Want My Bandana; I’m Too Big; Puppy Finds a Friend; Space Postman; What’s for Supper?

DK Publishing, My First Spanish . . . (board books): Animals, Words, Farms, Numbers, Trucks

Houghton Mifflin’s Good Beginnings series, written by P. Zagarenski: How Do I Feel? / Como Me Siento; What Color Is It? / Que Color Es Este?

Little, Brown’s Concept Books, written by R. Emberley: My Animals, My Food, My Numbers, My Shapes, My Toys, My Clothes, My Day, My House, My Opposites

Figure 5.5 Bilingual and Multilingual Books for Early Readers

Ada, A. and Zubizarreta, R. (Trans.). (1999). The lizard and the sun: A folktale in English and Spanish / La lagarija y el sol. New York: Dell.

Chin, C. (1997). China’s bravest girl: The Legend of Hua Mu Lan / Chin Kuo Ying Hsiung Hua Mulan. Emeryville, CA: Children’s Book Press.

De Zutter, H. (1997). Who says a dog goes bow-wow? New York: Doubleday.

Ehlert, L. (2003). Moon rope / Un lazo a la luna. San Diego: Harcourt.

Elya, S. (1997). Say hola to Spanish, otra vez (again!). New York: Lee and Low Books.

Griego, M., Bucks, B., Gilbert, S., Kimball, L., and Cooney, B. (1988). Tortillas para Mama and other nursery rhymes (bilingual edition). New York: Holt.

Heiman, S. (2003). Mexico ABCs. Minneapolis, MN: Picture Window Books.

Hinojosa, T. (2004). Cada niño / Every child: A bilingual songbook. El Paso, TX: Conco Punto Press.

Jaramillo, N. (Comp.). (1996). Las nanas de abuelita / Grandmother’s nursery rhymes. New York: Holt.

Johnston, T. (1996). My Mexico-México mío. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Morales, Y. (2003). Just a minute: A trickster tale and counting book. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Reiser, L. (1998). Tortillas and lullabies / Tortillas y cancioncitas. New York: Greenwillow.

Rohmer, H. (1997). Uncle Nacho’s hat / El sombrero del Tio Nacho. Emeryville, CA: Children’s Book Press.

Soto, G. (1995). Chato’s kitchen. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

We are great believers in the potential of language-experience activities for nurturing students’ reading development. Language experience for young readers begins with an experience, individual or shared (see Chapter 13), that is discussed with classmates and the teacher. Next, the child or children dictate a text about the experience to the teacher, who immediately transcribes the oral text onto paper that all participants can see or onto a computer screen using large fonts that enable easy viewing.

The dictated and written text then becomes instructional material. Students can read these texts because they are familiar. Moreover, children come to see themselves as writers as well as readers.

Dictated texts contain a variety of phonic and structural word patterns because they are derived from natural language. For this reason dictated texts are useful for focused instruction and practice in decoding skills and strategies. For example, after instruction about a particular beginning consonant (onset) or structural element, students can search their dictated texts for words that contain that element. The additional and repeated readings that occur when students read their dictated stories for targeted elements or patterns will also build their sight vocabulary and proficiency in reading fluency.

5.7 Texts and Reading Fluency

Fluency is the bridge between word recognition and comprehension. It is marked by quick, accurate, and expressive oral reading that the reader understands well. Fluency is a relative concept—all readers are more or less fluent depending on the nature and difficulty of the text being read. Although you are probably a fairly good reader, we could easily make you a disfluent reader by asking you to read something highly technical for which you have little background, perhaps an essay on nuclear physics or a legal contract.

Thus, when teaching reading fluency, we recommend that the texts students read not be overly difficult. For building reading fluency, we recommend predictable stories and texts, stories drawn out of a series (e.g., Cynthia Rylant’s Henry and Mudge series or Barbara Park’s Junie B. Jones series), stories around a given theme, stories with a minimum of difficult words or grammar, and stories that are not too long. Once students become familiar with a book that is part of a series, for example, their familiarity with the author’s style, the book’s characters and setting, and the general plots will enable them to read succeeding books in the series with greater fluency and understanding.

Difficult texts may require teacher support. The teacher may read the text once or repeatedly, for example, or ask students to read with partners. Stahl and Heubach (2005) found that under these conditions students can benefit from working with more challenging texts.

Among the instructional strategies we have advocated for fluency development is repeated readings (Samuels 1979/1997). Because repeated readings, by its very nature, requires students to read a passage more than once, texts used in repeated readings should be relatively short (50 to 250 words in length). Where do you find such texts? One way is to break a story into 250-word segments. Another and preferred approach is to use poetry for students. Poetry is short, highly patterned, and predictable, and it contains letter patterns that can be adapted to phonics instruction. Perhaps most importantly, poetry is meant to be performed, to be read aloud to an audience. If a text is meant to be performed orally, the reader has a real reason to practice so that reading to the audience will be flawless and meaningful. Thus, poetry, the same poetry that we mentioned earlier in this chapter for phonics and word study instruction, is ideal for building students’ fluency.

With current reading programs’ emphasis on prose reading, poetry is sometimes ignored in the reading curriculum (Perfect 2005). Using poetry for fluency instruction will certainly improve students’ fluency. Of equal or greater importance, integrating poetry and poetry performance into the classroom will add variety and help students develop greater appreciation for this most aesthetic of reading texts.

In ConclusionPredictable materials offer beginning readers the support and encouragement they need to grow as readers, and to grow in their belief in themselves as readers. Benefits are similar for children learning English and for those who struggle in reading. One study that compared children’s learning with predictable literature to their learning with basal reading materials concluded that “using predictable materials with beginning readers spurs their acquisition of sight vocabulary, encourages them to use context clues when encountering unfamiliar words, and creates more positive feelings about reading aloud” (Bridge, Winograd, and Haley 1983, p. 890). This conclusion is a strong endorsement for using authentic, predictable materials, and one with which we concur.