EDU 371: Phonics Based Reading & Decoding week 3 DQ 1

9 Word Walls

A classroom that fosters word learning looks the part. Words are everywhere—labels, children’s writing, chart stories, and other displays. Sometimes children’s attention is purposefully drawn to all this print. Other times, the print is a literate backdrop while children engage in other activities. It’s been said that interest in words is caught, not taught. We agree, and we think that the physical environment in the classroom can encourage children to catch an interest in words.

Within these word-laden classrooms, several principles drive word recognition instruction (Rasinski, Padak, and Fawcett 2010). Word recognition instruction is an inherent part of, rather than separate from, meaningful reading and other reading activities. Instruction takes on a playful, problem-solving feel, so children think about words actively and develop a thorough understanding of how words work. Children need lots of opportunities to see words and word parts within the context of meaningful activity, a notion that Sandy McCormick (1994) calls multiple contexts/multiple exposures. The teacher’s role is to help children see their options for word recognition and to encourage word recognition practice in real reading situations (National Reading Panel 2000).

Word walls can help to achieve these goals. Moreover, word walls send significant messages to students and classroom visitors: “Words and reading are important in this room,” “We celebrate words here!” In this chapter, we describe word walls and offer lots of examples of word wall activities.

9.1 What Is a Word Wall?

Think of a word wall as a working bulletin board that focuses on words. That’s essentially what it is—and more. A word wall can also be thought of as a billboard or advertisement to students about words. To create a word wall, the teacher first places a large sheet of chart paper or butcher paper on the wall. Either alone or in discussion with students, the teacher decides on the focus of the word wall. From that point on, anything goes. Students may add several words to the word wall each day, and the teacher may add words as well. Students may look for and make connections between and among words. The teacher may ask students to read the words on the word wall for practice or may use the words as a source of quick guessing games: “Find a word on the word wall that _______.” And of course, the words are easily visible for other student uses, such as checking on spelling.

Although the teacher and children may write directly on the word wall, we advise making word cards that can be manipulated. Words can be printed on large sticky notes or cut‑up pieces of newsprint; masking tape or spray‑on adhesive can be used to affix the word cards, which should be large enough for easy viewing.

All students should watch and listen when word wall words are added. The teacher should say the word and comment briefly on it. These comments may connect to the word’s meaning, its relevance to the focus of the word wall, or even some aspect of word study, such as “What vowel sound do you hear?” or “How many syllables does this word have?” These quick conversations provide just the sort of multiple exposures essential for successful word learning.

Most word walls are temporary; after a few days or weeks, new word walls replace old ones. You might want to keep the old word walls available to children, however; one teacher noted that her students enjoyed adding new words to old word walls as the school year progressed: “These were actually living word walls, and I, and the kids, used them and loved them and loved watching them grow” (Blachowicz and Obrochta 2007, p. 148). Word walls are meant to be used not just viewed.

9.2 Sources of Words

Word wall words can come from any area of the curriculum. One caution, though: don’t include too many totally unfamiliar words on a word wall. Learning new words in isolation is very challenging for most children. New words or concepts should first be encountered in the context of reading or discussion. After students have gained some familiarity with new words, they will be able to think about them apart from context. This is the time for word wall activity.

Beyond this general guideline, teachers will find many uses for word walls. In reading, for example, a word wall might focus on synonyms, particular word families or roots, or vowel or consonant sounds. Word walls are a good choice for vocabulary development activities as well. Bi‑ or trilingual word walls can provide names for common objects (or other areas of study) in English and other languages spoken by members of the class. Including pictures of these objects will support all children’s learning but is especially important for English language learner (ELL) students (Helman and Burns 2008). In writing, word walls may be used to collect powerful verbs, similes, or metaphors. A math word wall might offer synonyms for addition or examples of geometric figures (perhaps accompanied by sketches). Figure 9.1 provides several websites that have lots of additional word wall activities and ideas.

Word walls are adaptable. In essence, teachers may use them in any way that supports students’ learning, either about words and word parts or about new concepts. This versatility is one of their instructional strengths. Students quickly become accustomed to what word walls are and how they work, so teachers have a useful routine for addressing lots of curricular goals.

Figure 9.1 Online Resources for Word Walls

http://www.teachnet.com/lesson/langarts/wordwall062599.html

Information about goals, construction, and possible uses of word walls

http://www.teachingfirst.net/wordwallact.htm

Word wall activities

http://abcteach.com/directory/teaching_extras/word_walls/

Some starter lists of possible word wall words

www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/word-walls-work

An article called “Word Walls That Work”

http://specialed.about.com/od/wordwalls/a/morewordwalls.htm

Lots of quick word wall activities

9.3 Using Word Walls

In this section, we offer ways to construct and use word walls. By no means is this an exhaustive list. Our intent is to help you think about possibilities.

Name Walls

Early in the school year, most kindergarten/early primary teachers focus on children’s names. The children get to know one another through an immediately meaningful reading activity. Word walls of students’ names are a handy instructional tool. Children can read the names each day, with teacher assistance as needed. Names can be sorted into categories such as boys or girls, present or absent, or school lunch or brought lunch. Later in the year, the name wall can be used to introduce alphabetical order or draw children’s attention to letters within words. The latter could involve simply counting letters within each person’s name, grouping names by numbers of letters, or arranging the entire list from least to most letters (or vice versa). Even quick guessing games, such as “Who has more letters? [Student A or Student B]?” or “How many of us have a B in our names?” provide quick, game-like practice thinking about letters as parts of words. “Who has more letters?” is also a way to teach the mathematical concepts more and less.

Hall and Cunningham’s (1997) “ABC and You” activity is easily adapted to word wall format. First, children’s names are listed in alphabetical order; next, each child selects at least one word that begins with the same letter as his or her name. These are added to the alphabetical list:

A . . . Adorable Annie

E . . . Energetic Emily

M . . . Merry Matt

. . . Mysterious Mike

Children’s interest in these name walls sometimes leads to their finding new words to go along with their names. If moveable word cards are used, “Adorable Annie” can easily become “Active, adorable Annie” and so forth. “Hey!” one child said to Mike. “You could add munching to yours.”

Figure 9.2 Sam’s Name Wall

Student of the Week is another feature in many classrooms. Why not create a word wall about the featured student? It might contain words that are special to and descriptive of the student: names of family members, pets, favorite foods, personal characteristics. Or it might be a sort of name poem that includes words other children think are related to the featured child. Figure 9.2 shows an example of this kind of word wall. At the end of the week, the featured student can take the word wall home for further celebration.

Environmental Print Walls

Attention to environmental print is a staple in many early literacy classrooms because of children’s interest and familiarity in the words that surround them outside of school. An environmental print word wall may be general—for example, “Words We See.” Another option is to select some category of environmental print—for instance, cereal or sneakers—and challenge children to find as many examples as possible. They may even want to bring in logos from empty boxes or look through old newspapers and magazines for homework, to find additions to the wall. Since the logos are often more salient than the print for beginning readers, teachers should also print the words separately, apart from the logos, to provide children with a context-free look at the words.

The resulting wall can be used for practicing words and developing other early literacy notions, such as letter recognition. Depending on the focus of the wall, children’s concepts of print can also be addressed. Think of fast-food restaurants, for example, that have one-word names (or two-word names), or a math activity in which children select their favorite fast-food restaurants and create a class bar graph entitled “where we like to eat.”

Word Webs

Word webs (Fox 1996) is a small-group instructional activity that focuses students’ attention on particular word parts. To engage students in word webbing, the teacher selects a meaningful word part for focus, such as a prefix or Greek or Latin root, and assembles dictionaries, paper, pencils, chart paper, and markers. To begin, the teacher introduces the word part—for example, port—and invites students to brainstorm words that contain it. (See Chapter 8 for more on derivations.) These are written on the chalkboard; after a few have been suggested, the teacher asks students to speculate on the meaning of the word part.

Next, small groups assemble. One person in each group circles the word part in the center of a sheet of paper. Now group members search their memories and the dictionary for other words containing the word part. The goal is to find as many words as possible. They list these, talk about word meanings, and ultimately group related words in ways that make sense to them. These word groups are added to the word web as clusters or mini-webs (see Figure 9.3). Finally, groups share their webs with the rest of the class.

After the whole-class discussion, small groups reconvene, make changes in their initial word webs if they desire, and prepare a final copy of their webs using chart paper and markers. These final copies are combined on a word web wall, which is a large sheet of chart paper labeled with the word part that children studied. Another alternative, perhaps a bit more challenging, is to ask different groups to create webs for different word parts, such as prefixes. The resulting word wall, then, would be a compilation of webs about different prefixes.

Figure 9.3 A Word Web

Word webbing is probably most appropriate for intermediate-level students, but the same idea could be used in primary classrooms to create word family walls. Here, students would brainstorm about words that contain a given word family—for example, ant—then proceed as described earlier. Reading a book like Cathi Hepworth’s (1992) Antics! to children beforehand may spark their imaginations.

Content Area Walls

A content area word wall can record words that students believe to be important to some unit of study. As a new unit begins, the teacher can ask students to brainstorm words associated with the topic of the unit: “We’re going to study electricity. What words do you think of when I say the word electricity?” This brief activity serves two important purposes. First, since it gets students thinking about the topic of the unit, it’s a quick and effective prereading activity. A second benefit is the diagnostic value of the resulting list, since teachers can learn about students’ prior topical knowledge by examining the quantity and variety of words.

Occasionally throughout the unit, the teacher can invite children to add more words to the content area wall. Word walls can also provide content area cohesion for teachers who use trade books to augment conceptual learning. Here’s how Bonnie, an intermediate-grade teacher, explains it:

Our textbooks are pretty boring and much too difficult for some of my students, so I try to supplement with a few library books. When we started studying electricity last fall, I read Nikola Tesla: Spark of Genius [Dommermuth-Costa 1994] to the children, one chapter each day. In addition to learning about this fascinating man’s life, the students jotted down words related to electricity as I read, then they talked in small groups to decide which words to add to our electrifying word wall. Sometimes these were interesting and lively discussions—I remember quite a chat about gigantic streaks of light, which ended up on the word wall, and nature’s secrets, which didn’t.

Finding important words to add to the wall is a comprehension activity—students must understand the content and select words that are important to the topic under study. The content area wall provides a good record of what children have learned, especially if new additions are written with different colors of markers. A semantic web (like a word web) of all the words is an effective culminating activity.

Sight Word Walls

Sight words are those students recognize instantly and effortlessly. Common, high-frequency words (see Appendix B) are good candidates for learning by sight. Sight words are best learned by lots of contextual reading because students will encounter these high-frequency words often. A sight word wall can reinforce this learning. Five words can be added to the word wall every week and practiced occasionally during spare moments. In one year over 100 words can be added to a sight word wall. Although this may not seem like much, the first 100 words in Fry’s Instant Word List (Fry 1980) represent 50 percent of all words elementary students encounter in their reading!

Games can keep children’s practice with the words fresh. For example, children can say the first five words in soft voices, the next five in loud voices, and so on. Or one student might read the first word, two the second, three the third—a sort of word symphony! Children also enjoy reading in different voices (e.g., grumpy or happy) or as different characters (e.g., Donald Duck or Superman).

Story Word Walls

Teaching has been described as the process of making visible for learners that which is often invisible to them. When being read to (or reading on their own) students are so involved in the story that they often do not notice the interesting words that the author has used. Yet it is the author’s choice of interesting words that makes stories so engaging. When you read to your students (or when they read independently) ask students to take note of any interesting words that the author may have used. Put these words on a story word wall. Talk about the meaning of the words and why the author may have chosen those words over alternatives that may be more common. You may also want to have students add the chosen words to their personal word banks (see Chapter 11) . Then, encourage students to use the words in their oral and written language over the next several days. As the teacher, you should take the lead in this and try to use the words yourself. Be sure to point out to students when you do use these words. When they begin to use literary words in their own writing, their writing (and reading comprehension) will certainly improve.

Word Walls for ELL Students

Word walls are an instructional bonanza for ELL students. Meier (2004) outlines several principles and strategies for promoting second language development. Among them are the following:

Use of visuals and graphics

Careful introduction and teaching of key vocabulary

Informal attention to patterns and regularities in English spelling

Use of concrete objects and hands‑on literacy activities.

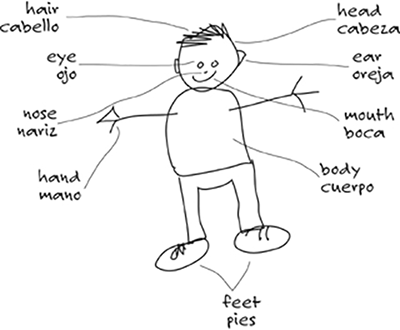

Word walls are useful for achieving all these purposes. Words might be illustrated with pictures of the objects they represent. These may even be presented conceptually, as seen in Figure 9.4. Moreover, if children’s first languages are included along with the English words, the word wall can be used to draw children’s attention to important phonetic contrasts between their first language and English (Helman and Bear 2007), which supports spelling development in English. A bilingual word wall also shows ELLs that their teacher values their first language; other students can learn some about the first language as well.

Figure 9.4 An Illustrated Word Wall

Writing Word Walls

Drawing children’s attention to effective aspects of others’ writing can help them see their own options as writers. Word walls are useful here, too (Ziebicki and Grice 1997). For example, the teacher might ask children to collect especially descriptive words, good character descriptions, or powerful sentences from their independent reading. As they find these features, children can write them on strips of newsprint and affix them to a writing word wall. These examples can be used instructionally. Discussions can focus on drawing conclusions based on the examples: What can we learn about effective character descriptions? What makes a powerful sentence?

The notion that students can choose and add words to such walls challenges and empowers them to be on the lookout for good writing—whether words, phrases, or sentences. Students are more likely to be fully engaged in an activity when we give them choice and ownership.

Spelling Word Walls

Certain words—because, of, and they, to name three—seem to cause universal problems for young spellers. At least part of a child’s spelling ability depends on visual memory. In fact, we teach children to inspect their writing to see if the words look right. A spelling word wall consisting of a few of these troublesome words may provide additional spelling support for children. Words can be collected from children’s unaided writing; good candidates would be common words that many children misspell. The teacher can remind children to check the wall if they are unsure of spelling; some teachers even require word wall words to be spelled properly. In time, when most children have mastered the first group of troublesome words, a new spelling word wall can be created.

A spelling word wall can be a useful instructional prop for lessons that focus on common rules, such as when to double a consonant before adding a suffix. Children and the teacher can collect words, decide about whether the consonant should be doubled before adding the ending, and put both the base word and its inflected forms in one of two columns on the spelling word wall: Double or Do Not Double. In addition to providing visual reinforcement of the rule, the decisions about where to place the words involve problem solving aimed at the spelling rule of interest.

Manipulating words on the spelling word wall can encourage students to use what they have learned in their own writing. In a review of four research studies about developing word knowledge in K–2 classrooms, Williams (2009) concluded that many children don’t naturally apply what they have learned about words to their independent writing. She also found that “students were more likely to use the word wall as a resource for their writing when their teacher used it as a teaching tool and also encouraged her students to use it strategically to support their independent writing endeavors” (p. 577).

Quick Word Wall Games

The presence of word walls in the classroom offers lots of incidental word learning and word play opportunities. Jasmine and Schiesl (2009) used these activities in a study with first-graders. They found that word wall games such as the following promoted sight word acquisition:

Be the Teacher: Children use all words to develop word quizzes or spelling “tests” for peers to solve.

Guess That Word: Children ask others to guess words they have selected; they offer clues based on the words’ formations.

Let’s Be Creative: Partners write a text using as many word wall words as possible.

Letters in Words: Teacher calls out a letter within a word wall word; students find as many other words as possible that contain the target letter.

One goal of word recognition instruction is to create a physical environment that invites exploration and play with words. The many possible word wall formats described in this chapter can help to achieve this goal. No matter the variation selected, all these activities meet the criteria we established at the beginning of the chapter for effective instruction about words. Students are free to explore and play with words; thinking and sharing are featured. Developing a word wall is a meaningful way for children to work with words, and using the word wall becomes a joint venture that interests all children. As such, word walls are an easy and effective addition to the classroom.