A term paper for the Buddhist Religions study (2000-2500 words)

Background

The Problem of Understanding Another World View

Q: What is religion? Why do people adopt a religion?

The “World View” in the Indian subcontinent in 567 BCE.

People generally believed the world view of Brahmanism, the Vedic tradition, and the many different gods and goddesses who were the forces of life and death and. Today we call this Hinduism.

People of that time thought about the world differently than the modern materialistic view we are familiar with today.

The cyclical nature of time and life

Atman and rebirth

Karma and the social caste system; social and political power

How did people learn in those times? In all ancient cultures that long ago people learned through oral teaching – stories and repeated recitations. Written language and texts were rare and few people could read.

Myth and stories were living experiences

People had faith in sadhus and yogis as people with special insights and powers.

People also had devotional practices taught by the Brahman priests, sadhus and yogis

The Story of the Buddha: his early life

Prince Siddhartha was born in Lumbini, in what is today Nepal, in approximately 567 BCE. Prince Siddhartha was born to a royal family in the Shakya clan.

Most likely the clan chose its leaders by consensus; it was probably more of a republic than an absolute monarchy.

At birth, a prophet predicted that Prince Siddhartha would become either a great king or great spiritual leader. His father, the local king, vowed that Prince Siddhartha would become a king.

The young prince was confined to the palace grounds and was surrounded by riches and pleasures. He was treated with kindness and deference by all and saw only healthy, happy people. He was trained as a prince in various arts and disciplines of his time.

Once as a child, standing under a tree and watching a garden being plowed, he became very quiet and had a deep sense of peace. This only lasted for a short period of time, but he remembered this moment later in life.

(Q. Have you had any similar experiences?)

As a young man he married Yasodhara, a princess, and had a son, Rahula. (Both become Buddhists later on.)

Discovering Samsara (the cycle of suffering)

Out of curiosity and intuition, Siddhartha contrived to go outside the palace grounds. He had four experiences that changed his life: the first three occurred when he saw an old man, a sick man, and a corpse. He asked, “Why, when all people are destined to suffer old age, sickness, and death, none can escape these things, yet they look on the old age, sickness, and death of other people with fear and scorn.”1

The fourth experience occurred on his second visit outside. He saw a wandering yogi, a spiritual seeker and ascetic, one who was looking for spiritual meaning through self-denial and discipline.

Having seen the impermanence of life, Siddhartha resolved that he too would renounce the things of this world and become a spiritual seeker. He wanted to find the solution to human suffering and he felt he could not do it living as a prince.

(Q. Why couldn’t he do it as a prince?)

Siddhartha escaped on horseback, cut his hair, gave up the horse and royal clothes and disappeared into the forest.

As a wandering spiritual seeker he joined Hindu sages who possessed “partial knowledge” but he did not profess to be enlightened or completely liberated from suffering.

Siddhartha practiced various types of concentration and learned to control his mind, but all of this was before he became enlightened.

The Enlightenment of the Buddha

After six years, Prince Siddhartha found he had many extraordinary experiences through the ascetic practices of the sadhus and yogis. But these practices did not give him the great transcending experience he was seeking that would end all suffering.

Instead, he changed his approach and he adopted the “Middle Way” to training the mind – and this was the beginning of Buddhist meditation. He found a middle way between the extremes he had experienced. The first sign of the Middle Way approach may have been that Siddhartha took food offered by a passing woman. (Q. Why would that be significant?)

This new approach, the Middle Way, was neither:

too tight nor too loose in concentration (mind training).

ascetic nor hedonist (in lifestyle),

eternalist nor nihilist (in philosophic or religious view)

Recalling his experience of momentary peace and tranquility as a child, he was reminded that it occurred when he was not striving for a goal, not seeking to accomplish or understand anything, but being completely present, in open attention, rather than seeking for whatever is next. That peace did not depend on anything but attention to the present moment.

As he practiced this new style of meditation, he went through many periods that were unsettling. He had thoughts and images of passion and aggression, but he remained true to his sole intention, which was to look right into the present moment, whether his experience was tranquil or unsettling.

The peace became deeper and deeper now that he had the natural discipline to remain in the present moment without being misled by daydreaming. He learned that being in the present moment did not mean chasing away bad experiences or clinging to good experiences.

After this simple practice of attention to the moment, the experience of “waking up,” also called “Enlightenment,” arose. At first, the Buddha had no way to describe it. Then he described Enlightenment as the complete and direct experience of reality beyond words and concepts. We can say that that the Buddha’s mind cleared completely of all hopes and fears, he saw the world just as it truly is. There is no word or label that can really contain this experience, although Buddhists use the word “enlightenment” or the expression “completely awake.”

With hindsight, later he said to others that he had woken up, and now all thoughts and images were transparent yet vivid, like the images remembered from a strong dream.

Rather than focusing on Enlightenment as a thing in itself, he talked to his friends about what he now knew about suffering.

Mindfulness Meditation Instruction

1. When we sit, we sit with our legs crossed and shoulders relaxed. We have a sense of what is above, a sense that something is pulling us up at the same time that we have a sense of the ground and connection to the earth. The arms should rest comfortably on the thighs. Whether you are sitting in a chair or on a cushion the main point is to breathe normally without constriction.

2. The chin is tucked slightly in, the gaze is softly focusing downward about six to eight feet in front, and the mouth can be open a little. The basic feeling is one of comfort, dignity and confidence. If you feel you need to move you should just move, just change your posture a little bit. So that is how we relate with the body.

3. And then the next part-actually the simple part-is relating with the mind. The basic technique is that we begin to notice our breath, that we could have a sense of our breath. The breath is what we're using as the basis of our mindfulness technique; it brings us back to the moment, back to the present situation. The breath is something that is constant and at the same time it’s always changing.

4. We put a little emphasis on the out-breath. We don't accentuate or alter the breath at all, just notice it. So we notice our breath going out, and after we breathe out, there is just a momentary gap, a space. There are all kinds of meditation techniques and this is actually a more advanced one. We're learning how to focus on our breath while at the same time giving some kind of space to our experience.

5. Then we may notice that even though what we're doing is quite simple, we have a many thoughts and feelings - about life and about the practice itself. And the way we deal with all these thoughts and feelings is simply by acknowledging them, noticing them, and returning to our breathing. We can be open to whatever comes up without chasing it away, just very gently return to the breath. There are no exceptions to this technique: there are no judgments necessary about good thoughts or bad thoughts, good feelings or bad feelings….In the face of all our thoughts and feelings, it is difficult to be in the moment and not be swayed. Our life has created a barrage of different storms, elements that are trying to unseat us, trying to destabilize us. All sorts of things come up, but in this practice they are all reminders to come back to the present moment and remain open. That is known as “holding our seat,” and developing our stability in the present moment.

Contemplation:

Why do human beings have so much suffering?

The Enlightenment of the Buddha

Prince Siddhartha went through many periods of unsettling experience as he sat in meditation. Afterwards he reported that he felt peaceful sometimes, but sometimes he had many distracting thoughts and images and feelings of desire and anger. But he remained true to his intention, which was to look right into the present moment and see what was real. He was not trying to escape the experiences of life, but to see life for what it is without filters of hope and fear. He wanted to understand why there was suffering in the world and he started with his experience in the present moment.

After this simple practice of attention to the present moment without clinging to any extreme views, the experience of enlightenment arose. This is the point at which Prince Siddhartha, also known as Siddhartha Gotama, became the Buddha. “Buddha” means “one who is awake,” “one who knows.”

What do Buddhists mean when they refer to enlightenment? Enlightenment is the complete and stable experience of reality as it is, without assumptions or projections. The Buddha did not label enlightenment as an experience of “God” or “Brahma” as the Hindu yogis might have because he knew that would make people think that Enlightenment was something outside themselves, something external, beyond their own experience. On the other hand, he did not label enlightenment as “Self,” which would lead people to think that their ordinary sense of themselves – thoughts, feelings, perceptions – was all there was. So if enlightenment was not an experience of God or an experience of the ordinary self, what was it?

What was unique about what the Buddha discovered was the “Middle Way” approach to experience. The Middle Way teaches the student to let go of fixation on extreme views of reality. What does “extreme views” mean? Extreme views have opposites that exclude each other, for example a person’s:

lifestyle can be ascetic or hedonist

mental focus (in mind training) can be too tight or too loose,

philosophy or religious view can be theistic or nihilist.

The Buddha regarded extreme views as not reflecting reality as it is. The Buddha said that reality does not conform to any extreme beliefs.

Important Themes from the Buddha’s early teaching based on his own life story that pervade Buddhism throughout its history:

The Buddha taught that he was a human, not a god. He was an example of every human being’s potential.

The Buddhist path is the Middle Way; it is not being fixed on extreme views.

Enlightenment is a natural state of awareness possible for all human beings. It is not bestowed by a savior or an external deity. No one can undo the habitual patterns of the ego that lead to suffering other than the individual. While guidance and support are valuable, and even essential for most people, each person must find the path to enlightenment for him or herself.

The liberation from personal suffering, also called “nirvana,” enables the meditator to experience a stable, profound peace of mind even in the midst of suffering, even at the moment of death. It is not a trance-like absorption or some other state of consciousness. It is clarity beyond conceptual extreme views.

Theoretical speculation about metaphysical issues (such as what is the origin of the universe and who created it, is there life after death, etc.) is a sidetrack until the student of Buddhism understands the nature of the ego (self) and its concepts. Buddhists understand metaphysical questions differently once they understand the illusions of ego and false beliefs about reality.

At first, even the Buddha had no way to describe enlightenment. With hindsight, later the Buddha said to other spiritual seekers that he had “woken up,” as if his own past as an Indian Prince was all a kind of vivid dream. After the other spiritual seekers asked him what he had learned, here is how he described it:

The Four Noble Truths – the first teaching of the Buddha

Suffering. There is basic suffering that comes with the impermanence of all things and relationships: losing what one has is inevitable. Impermanence leads to the suffering connected with our own body: sickness, old age and death. Suffering also includes all forms of pain, anxiety and worry that we will not be happy. On a more subtle level, suffering even includes all sense of struggle. All sentient beings experience suffering.

The Origin of Suffering. Ordinarily, all beings cling to a limited notion of self, our “ego.” The ego depends on what we become attached to: our physical body, relationships with others, our home, the many things we possess, and most importantly, our ideas. This attachment (grasping and fixation) is the origin of suffering. This attachment brings about the desire, hatred, and ignorance that comprise further suffering. Thus, clinging to attachments is the origin of all suffering.

The Buddha focused in particular on how we become attached to a notion of our self, our ego. Does the ego truly exist?

The Buddha described this idea of self as the sum of all our attachments.

He acknowledged that ego appears to exist. But for something to truly exist from a Buddhist point of view it would have to be permanent, singular, and independent of everything else. Otherwise it is impermanent, compound (assembled from parts) and interdependent with other appearances.

From the Buddhist point of view the ego is an illusion; it does not truly exist. The ego is like a dream we need to wake up from. The ego only appears to exist, just like the experience in a dream.

If we let go of attachments we begin to let go of our ego and illusions.

The Cessation of Suffering.

Nirvana, which is the cessation of individual suffering, is possible. It is possible to see through the illusions of ego.

It doesn’t work to accept the Dharma (the Buddhist teachings) on blind faith: Addressing his early students, the Buddha said,

“… just as a goldsmith tests his gold by melting, cutting, and rubbing, wise people accept my teaching after full examination and not just out of devotion. Accept my words only when you have examined them for yourselves; do not accept them simply because of the reverence you have for me.”

and,

“Those who have faith in me and devotion to me will not find final freedom. But those who have faith in the truth and are determined on the path, they will find awakening."

The term “nirvana” means the cessation of suffering, peace without struggle. (Later we will see that complete Enlightenment is even greater than nirvana.)

The Path: The Path is the way to achieve the cessation of suffering. The Buddha presented the path in its most simplified form in three aspects:

The View: holding the attitude and considering all things that have a beginning and an end to be impermanent, compounded and interdependent;

Meditation: practicing mindfulness and awareness of the present moment at all times; and

Conduct: acting in ways that cultivate “waking up” from ignorance and illusion and refraining from actions that are based on ignorance, aggression and personal desire.

Sometimes the Path is elaborated as the Eightfold Path which will look at next week.

The Early Sangha (Community of Practitioners)

From the beginning, some people became monks and nuns while others remained as non-monastic practitioners, people who could not or would not take monastic vows, but still tried to study and practice as much as they could.

Examples: householders, merchants, even kings. (e.g. records show King Bimbasara and King Sucandra were students of the Buddha)

However, the predominant way to follow the Buddha was to become monastic. The monastic order began when the Buddha realizes that some people benefited from rules to simplify one’s life. (Story of the rowdy feast.)

The monastic life was a more intensive way to uproot habitual mental and behavioral patterns that perpetuate suffering and the conditions that bring suffering.

Women were admitted to the monastic order in the time of the Buddha. The same teachings that were given to monks were given to nuns. The Buddha believed women could attain Enlightenment as well as men. This was probably resisted by the early monks and surprised people in the wider population. In those times women might be religious, but to give up their role in their families and become a nun would have been very unusual.

However, because of the general social views on women, nuns were still regarded as subservient to monks, just as wives were regarded as subservient to their husbands in general society.

The monks and nuns trained rigorously to pay attention to their experience in the present moment: not just in formal meditation, but during eating, walking, going about chores, etc. They were trained to recognize their own desires, anger, and ignorance. They were trained to look carefully at the consequences as well as the fundamental cause of their passion, aggression, and ignorance.

The role of monks and nuns in the larger society was:

to share the Dharma so that people could understand the truth of how suffering gets created;

to provide counsel and guidance on daily life for people at all levels of society; and

to provide a place for temporary retreat, although for many it became a lifelong commitment.

The Mission of the Buddha: Whether they became monks and nuns or remained as ordinary people, the motivation of Buddhists is to look directly at their own experience is generally described as two-fold:

wanting to reduce suffering (anxiety, dissatisfaction, pain), both our own and others; and

genuine curiosity about what is actually going on; wanting to learn the truth.

From ancient times, Buddhists trained to remain relaxed and alert, and look directly and simply at what actually is happening, beginning with mindfulness – basic meditation practice. That is how the early Buddhists reduced suffering and discovered the truth.

Taking Refuge

There is a formal vow called taking “refuge” that establishes someone as a Buddhist. Buddhists take “refuge” from Samsara (the cycle of confusion and suffering) by committing themselves to the path taught by the Buddha (one who is completely awake), the Dharma (the teachings) and the Sangha (community of practitioners).

The Buddha is the example of one who has completely mastered the Path

The Dharma is the Teaching; and

The Sangha is the community of practitioners.

The Teaching of the Theravadin Tradition, the earliest teaching of the Buddha is contained in the Tripitaka (the Three Baskets).

The Sutras: the original words of the Buddha, such as the teaching on the Four Noble Truths.

The Abhidharma: classifications of mind, its functions, and matter; Buddhist psychology.

The Vinaya: the monastic guidelines (to be discussed briefly later)

Contemplation:

What does your happiness really depend on? Is it possible to achieve permanent happiness?

The Origin of Suffering

The Sutras are regarded by Buddhists as the actual words of the Buddha preserved through oral tradition and eventually recorded in writing. In the Sutras, the Buddha described how mind works to create the illusion of a permanent self and consequently gets trapped in suffering.

If people could understand how we create our ego, moment to moment, they will understand how we create suffering for ourselves and others.

Q: What is the “self” that we identify with? Are we are just bodies? Are we our memories? Classically, the Buddha taught five ways that we collect information again and again to make up our ordinary experience of self, the ego:

The Development of Self through the Five Skandhas:

Form: the basic duality of self and other, “me” and “not me.”

Sensation: very basic positive, negative, neutral reactions to “other;” where we encounter “not me.” (Sensation is not to be confused with emotions or feelings that develop through concept formation.)

Perception: experiencing the sensory details and qualities; the beginning of context.

Concept Formation: the use of memory to label certain perceptions and relate them to previous experience. Concepts help solidify experiences into “things” that have names.

Consciousness: the story-line we tell ourselves about what is happening. Here concepts come together to explain what is happening. Emotions develop from concepts and consciousness.

What is the conventional sense of self (or the ego) from a Buddhist perspective? The ego is the total of these five skandhas working without our awareness. Ego operates primarily by habit or “previous conditioning,” to put it in psychological terms. Yet our basic awareness of the present moment is always there underneath or mixed in with ego.

If people have clear awareness then the skandhas can be seen as they develop, according the Buddhist teaching and the experience of meditation masters. Clear awareness of the skandhas comes when the person recognizes each skandha as it is without attachment or fixation.

People who gradually develop such “egoless” awareness see the five skandhas as “transparent’, They see through them which means “without attachment.” Then the skandhas are said to be “transformed into wisdom.” In other words, awake people still experience form, sensation, perception, concepts and consciousness but they do not fixate on them and cause suffering.

The traditional term for developing egoless awareness is “purifying one’s mind and heart.” Western Buddhists often interpret this in psychological terms rather than traditional religious terms such as “purification.”

The Eightfold Path: the way the early monastic Buddhist community (the sangha) lived:

The Buddha did not want people to feel bad about their imperfections, rather people should learn from their imperfections. People can see themselves more clearly when they do no push particular experiences away, or cling to particular experiences, or ignore particular experiences. Therefore gentleness and practice are essential; guilt and anger do not help.

In the Buddhist tradition, one aspires to the eight-fold Path. Bu it is not a “sin” if one cannot always practice perfectly. A famous Chinese Buddhist, the Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism said: “The highest realization is to be without anxiety about imperfection.”

Especially for modern Buddhists, whether they are from the west or Asia, this means there is no guilt or shame if one is honestly trying but unable to practice perfectly. In fact, patience is one of the virtues to be cultivated.

The Eightfold Path:

View

Mindful understanding, also called contemplation (examining for oneself the nature of suffering, impermanence, interdependence, etc.), which leads naturally to

Mindful intention (not causing harm to others; loving kindness and compassion for all beings)

Meditation

Mindful effort (not too tight, not too loose)

Mindful meditation practice (one-pointed attention – focusing on the present without becoming totally fixated or absorbed)

Mindful awareness (unbiased experience, open yet clear and penetrating); extended during and after formal meditation practice.

Conduct

Mindful speech (abstaining from lying, gossip, etc.; speaking the truth when it is useful and timely)

Mindful action (not killing, not taking what is not given; not indulging in sense pleasures, not being ascetic, giving what others need, etc.)

Mindful livelihood (not engaging in practices that cause harms to others)

Turning the Wheel of Dharma: The Three Yanas (stages on the Buddhist Path)

(See file on Blackboard Class Notes/Overview of the Stages)

The Theravada (the tradition of the elders) the core teaching for people who are suffering and beginning the Buddhist Path. The Theravada focuses on self-liberation. This is sometimes called the Hinayana, which means the “narrow way,” the way through monastic living.

The Mahayana – (the “open” way”) of working for the benefit of others; teaching focuses on absolute and relative truth, emptiness and compassion; more inclusive than Theravada because it is not necessarily monastic. The Mahayana focuses on benefiting all sentient beings as the path to Enlightenment.

The Vajrayana – (the indestructible way) If we can understand the Theravada and the Mahayana it is possible to transmute suffering in all its forms (passion, aggression, ignorance and all conflicting emotions) into their wisdom nature and use the energy of suffering to benefit others. The Vajrayana is a more provocative and difficult approach, but it is still firmly based on lower yanas (stages).

***************

Contemplation Part 1: Are you something more than your ego? If so, what?

Class 4

Review: The Development of Ego

From the Buddha’s teaching, the origin of suffering is the ego, defined by attachment and fixation on things and ideas that give us an illusory sense of identity and security. The Buddha taught how the ego develops its patterns and habits through the Five Skandhas (Aggregates):

Form: the spark, or momentary events that we experience as self and other.

Sensation: positive, negative, neutral connections to momentary events

Perception: details, qualities; the beginning of context

Concept Formation: the use of memory to label certain perceptions

Consciousness: the narrative or story-line we tell ourselves about what is happening – this is where the ego fully manifests

Ego arises in the consciousness when the five skandhas operate “automatically” without awareness. This false sense of self produces ignorance, aggression and blind desire. From these come jealousy, pride and envy and other negative states of mind.

Why is this teaching about the ego so important?

Understanding the ego is central to understanding suffering in Buddhism. From the Buddhist perspective people can’t actually see things as they are when they are caught in the habitual patterns of ego. People filter information, distort what they experience, and usually rely on habits. The usual approach to experience is soaked in habitual patterns. For example, we take external experience as objective (solidifying what we see) by:

identifying things mostly according to memory and past conditioning,

making judgments and assumptions based on the past, and

acting as if our experience is absolutely true.

We may then act in ways that cause more suffering for ourselves and others.

If something happens and we like it, we try to hold on to it (passion); if something happens and we don’t like it we try to reject or destroy it (aggression); and if something happens that doesn’t seem to matter, we try to ignore it (ignorance).

Examples

(Story of the man on Parliament Hill)

Can you think of a story where you were caught in habitual thinking and then learned you were mistaken?

Ambiguous figures (to be discussed in class)

The Way of the Elders (Theravada Buddhism)

The predominant way to follow the Buddha during his life was to become monastic, study the Sutras (the teachings given by the Buddha himself) and to practice the eightfold path. The monastic order began when the Buddha realized that many people benefited from rules on how to simplify one’s life.

(The picture to the left is taken from a Buddhist monastery in Prince Edward Island, Canada – an unusual place for Buddhism to appear that has now grown to 400 monks and nuns, mainly from Taiwan.)

![A term paper for the Buddhist Religions study (2000-2500 words) 3]()

The monastic life was a more intensive way to uproot habitual mental and behavioral patterns that perpetuate suffering and the conditions that bring suffering.

Women were admitted to the monastic order in the time of the Buddha. The same teachings that were given to monks were given to nuns. The Buddha believed women could attain Enlightenment as well as men. This was probably resisted by the early monks and surprised people in the wider population. In those times, women might be religious, but to give up their role in their families and become a nun would have been very unusual. (Today, the leader of a Buddhist community in Prince Edward Island is a woman, Master Zhen-Ru.)

However, because of the general cultural views on women in Indian society, nuns were still regarded as subservient to monks, just as wives were regarded as subservient to their husbands in the general society.

The monks and nuns trained rigorously through the eightfold path to pay attention to their experience in the present moment: not just in formal meditation, but during eating, walking, going about chores, etc. They were trained to recognize their own desires, anger, and ignorance and, at the same time to be kind to themselves and others through mindfulness and awareness. They were trained to look carefully at the consequences as well as the fundamental cause of their passion, aggression, and ignorance.

The monks and the nuns were not entirely isolated from society. The role of monasteries, monks and nuns, in the larger society of ancient India was:

to share the Dharma so that people could understand the truth of how suffering gets created;

to provide counsel and guidance on daily life for people at all levels of society (including matters of health); and

to provide a place for temporary retreat, although for many it became a lifelong commitment.

Beyond Ego

What is it that enables people to see their habitual patterns? What else is there in every moment besides the development of ego?

First, meditators don’t lose form, feeling, perception, concept or consciousness. People don’t lose ability to relate with the world or lose all their individual characteristics when they are in the present moment and open.

Through meditation and contemplation, people experience the openness of awareness, or “things as they are” before they make up a context. They notice there is nothing to be afraid of by looking directly at their own experience. People can explore their perceptions, concepts and even their personal stories without losing awareness.

There is a sense of energy and well-being in direct perception or “bare attention” as described in the basic meditation practices of the Theravadin Buddhist tradition.

The two qualities of direct perception are clarity and stability. Things can seem more vivid yet somehow transparent at the same time.

The sense of energy and well-being is called bodhichitta in the Sanskrit language of ancient India, (it literally means “knowing mind”) and is sometimes translated in English as Buddha Nature.

In modern translations, it has been called the “basic goodness” of being human (see Shamabhla.org).

In Chinese Buddhism, one word for this sense of energy and well-being appears as:

菩提心, putixin

At the most profound level, bodhichitta is a pre-conceptual experience that underlies all constructed experience. Another way to talk about bodhichitta is a natural feeling of confidence and kindness to oneself that extends to others. It is the seed of compassion.

Bodhicitta is also described as the desire to alleviate others’ suffering.

If we identify with this basic goodness, ego begins to dissolve.

This teaching on developing kindness to oneself and compassion for others was there in the most ancient forms of Buddhism. When it was emphasized later in Mahayana Buddhism it enabled Buddhism to spread to an even wider audience and reach all across Northern Asia. It became known as the Greater Way.

Turning the Wheel of Dharma: The Three Yanas (stages on the Buddhist Path)

(See file on Blackboard Class Notes/Overview of the Stages)

The Theravada (the tradition of the elders) the core teaching for people who are suffering and beginning the Buddhist Path. The Theravada focuses on self-liberation. This is sometimes called the Hinayana, which means the “narrow way,” the way through monastic living.

The Mahayana – (the “open” way”) of working for the benefit of others; teaching focuses on absolute and relative truth, emptiness and compassion; more inclusive than Theravada because it is not necessarily monastic. The Mahayana focuses on benefiting all sentient beings as the path to Enlightenment.

The Vajrayana – (the indestructible way) If we can understand the Theravada and the Mahayana it is possible to transmute suffering in all its forms (passion, aggression, ignorance and all conflicting emotions) into their wisdom nature and use the energy of suffering to benefit others. The Vajrayana is a more provocative and difficult approach, but it is still firmly based on lower yanas (stages).

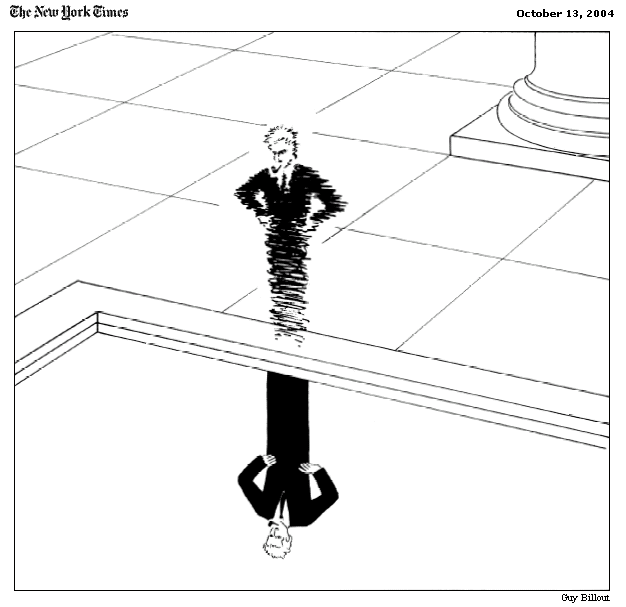

Contemplation Exercise: What does this cartoon mean in terms of ego and egolessness?

The Buddhist Understanding of Karma and Interdependence

From the Buddhist point of view, our conventional experience is not objective absolute truth. Although our everyday experience is functional and agrees with how most people see the world around us, we don’t see things clearly or completely. We see things and think about them through the processes of ego. We project onto our experience from habitual patterns, memory, and bias that we may not even be aware of.

Acting from ego, we produce karma.

Karma means action and the results of action.

What we experience now, our current conditions, is the result of previous actions (karma). Everything we do ordinarily creates causes and conditions for future results (rope demonstration).

But karma does not necessarily ripen all at once. It has no timetable that we can easily see because we are not aware of all the conditions that must come together to produce a particular result. That is why it is so difficult to understand our karma. Instead, we often think things happen by chance.

From the Buddhist point of view, nothing in our current conditions is viewed as arbitrary or random. From the conventional point of view, what we consider “good results” comes from past “good actions” and what we consider “bad results” comes from past “bad actions.” There are also “neutral results” that we consider neither bad nor good.

What distinguishes the Buddhist view of cause and effect from other views is that how we respond to our karma is not predetermined. Therefore, the future is not predetermined. If we see our whole situation clearly we do not have to repeat old patterns that may have caused suffering; we do not have to reproduce past karma again and again (story of Moggallana).

“If a person is able to meet the present situation, the present coincidence, as it is, a person can develop tremendous confidence...a tremendous spaciousness because the future is completely open.” - Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

That is why it is so important in Buddhism to train the mind to be fully in the present, not acting only out of habitual patterns from the past. If we act with insight into karma, then we “wake up” and help others “wake up” from the illusions that cause suffering and fear.

Q. What is it that enables us to see our habitual patterns at all? What else is there in every moment besides the repeated development of ego and its confusion?

The Wheel of Life (or Wheel of Suffering): Samsara (the cycle of suffering)

In the Buddha’s time most people could not read and write. So the Buddha and his disciples, monks and nuns, taught with the use of scroll paintings like the Wheel of Life. Without awareness we perpetuate the cycle of suffering (See .jpg file Wheel of Life)

Three Poisons:

Passion (rooster) (desire/greed)

Aggression (snake) (hatred)

Ignorance (pig) (delusion)

The three poisons are at the centre of the Wheel of Life. They propel beings through the endless cycle of birth and death and the difficulties associated with the six realms. With mindfulness and awareness the energy that goes into ego-centred desire, hate, and delusion can be seen for what it is. Then the three “poisons” can become “medicine” – compassion, clarity, patience, and other virtues.

Six Realms of Existence (see .pdf file from Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism course Readings in Brightspace for more detailed descriptions). For the ancient Indian people, the notion of the six realms of being was not new. They accepted the notion of rebirth in different realms. But Buddhists do not insist that the six realms be taken as literal states of being – they are not to be accepted on faith. The six realms can also be regarded as states of mind we pass through in our ordinary lives, and most people in any culture or historical time can relate to them.

The God Realm (Absorption/Fixation/Arrogance)

Jealous God Realm/Asuras (Feeling Jealousy/Feeling Paranoia)

Human Realm (Feeling Desire/Passion)

Animal Realm (Being Stupid/Ignorance)

Hungry Ghost Realm (Feeling Completely Impoverished/ Frustrated)

Hell Realm (Feeling Angry/Hatred /Aggression)

The Twelve Nidanas: the twelve links in the Wheel of Suffering

The Twelve Nidanas are another way that the Buddha presented how karma works.

Links 1 and 2 are said to be effects from the past, or past causes, which set the stage for the activity in the remainder of the nidanas. They operate in the background underneath our ordinary consciousness. As we come to know our current patterns, we gradually begin to see these first two nidanas as well.

Ignorance (metaphor: a blind person leading other blind people in a stubborn refusal to see the struggle of maintaining ego)

Formations/Concepts (Sanskrit: samskaras) The tendencies of ignorance to form into repeated activity and results, symbolized by a potter solidifying his clay. Note the speed involved in habitual patterns, just like the spinning of the potter’s wheel.

Links 3 through 7 represent the present effects of past causes and the solidification of ego. They happen so rapidly and so interdependently that it is difficult to see their separate functions. Taken together they set the stage for the next three links. It is between the 7th and 8th link that there is the greatest opportunity to cut the chain and see the nature of suffering. This is where compassion can arise as well.

Dualistic consciousness. We constantly assemble the component parts of what we call ego, symbolized by a monkey busily picking fruit.

Name and form. The mental and physical aspects of self-identity. (The passengers in the image of the boat are the emotional, discursive, and perceptual aspects of human experience being ferried by the boatman, consciousness.)

The six senses. The senses are the avenue to relationship with “other” – five physical and one mental sense. The ego reaches out to its world through perception to confirm itself, symbolized by a six windowed house.

Contact. Contact with “other” is made, illustrated by a couple in embrace.

Feeling. The response to contact, pleasure or pain arises as an initial flicker. The basic flavour of any feeling is intensity and this is shown as an arrow in the eye. This intensity makes us retreat further into our instinctive habitual patterns, and is the occasion for the arising of painful situations.

Comment: Links 8 through 10 are the present causes for future effects.

Craving (thirst). The overt presence of painful habitual patterns, self-indulgence, and impulsive reaction; shown by a greedy man about to slurp down a drink of milk and honey. From a Buddhist point of view, it is ultimately destructive to react impulsively to ego-centred demands.

Grasping/Attachment (consuming, holding on). The expansion of craving into emotional, intensified desire, shown by a man climbing a tree laden with fruit and eating voraciously.

Becoming/existence. The blindness of grasping inevitably propels itself toward form; symbolized by a woman getting pregnant and then about to give birth.

Birth through Old Age. A new form arises. The scale of experience could be the birth of a particular emotional state, a life time, a human relationship, or the beginning of a single thought process.

Death. Some level of panic and fear characterizes the habitual experience of death and leads back through the cycle of bewilderment and confusion.

Interdependence (Dependent Origination).

Another aspect of understanding karma is interdependence. No phenomenon truly exists by itself. All phenomena are dependently arising and therefore they have no true self-existence.

Even we, as individuals, do not truly exist by ourselves, although our egos would like to believe that we do.

Seeing the interdependence of causes and conditions can change the cycle of doing the same thing again and again out of ignorance (samsara) and relax the struggle inherent in suffering.

Awareness of interdependence is also called insight or panoramic awareness. (Sanskrit: vipassana) Insight is seeing clearly the causes and conditions of the present situation, which appear as both external and internal causes and conditions. Insight reveals interdependence.

According to Buddhist teaching, meditation produces a natural letting go of conceptual fixations and habitual patterns. Meditation opens the door to insight. This is how human beings are liberated from suffering without ignoring or turning away from reality.

From mindfulness and awareness people mature in their ability to experience all kinds of adversity without panicking, it becomes possible to open to the suffering that we and others experience.

Developing awareness of karmic interdependence requires regular practice and patience. Such awareness is not likely to become stable for meditators in a few minutes of meditation.

Karma and Meditation: What is the effect of meditation practice?

The immediate effect of meditation practice is the development mindfulness and awareness.

In the practice of sitting meditation we acknowledge our thoughts and let them go. Acknowledging thoughts without getting caught up in self-criticism is simple mindfulness (Sanskrit: shamatha), paying attention to the present moment, not too tight, not too loose. This one-pointedness is stable, focused attention, but not rigid fixation.

We can give in to the power of habitual tendencies and keep reproducing our karma, or we can let go.

Letting thoughts go is the same as awareness of space: just being awake, alert, present, without trying to make anything happen. Awareness is open attention without expectations; seeing things as they are. Then a Buddhist can act or not act from a point of view of wisdom.

Historical Notes

There were 18 schools of Buddhism that each emphasized different interpretations of what the Buddha said. Yet there were no quarrels about the basic teaching of the Buddha: the four noble truths, impermanence, egolessness, interdependence, refuge vows, and the motivation to reduce suffering by “waking up” from the delusions of ego.

Everything that follows in the history of Buddhism in some way comes out of the early teachings in India, although Buddhism may look quite different in each country and culture that it appeared.

Around 275BCE, about 200 years after the Buddha died, King Asoka in India proclaimed Buddhism as the best way for all of India to move forward, and for almost a thousand years Buddhism flourished in most of the Indian subcontinent.

It is said that Ashoka sent his son and daughter to Sri Lanka to establish the Dharma there around 250 BCE. From there it spread to all of Southeast Asia. (See Map 3. Pg. 92, Buddhism, third edition)

Contemplation Exercise Part 1:

“The experience of our interdependence with each other and our environment is the basis for compassion.” What does this mean?

Religious Studies 2327.1

Buddhist Religious Tradition

Class 6

Review: The Ego and Awareness

From the Buddhist perspective, if we have awareness in the present moment we can develop insight beyond our egos’ habitual thinking.

Insight uncovers bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is a pre-conceptual experience that underlies all conceptually constructed experience. Another way to talk about bodhicitta is a natural feeling of confidence and kindness to oneself that extends to others. Bodhicitta is the seed of compassion.

Bodhicitta is also described as the desire to alleviate others’ suffering.

If we identify with bodhicitta, ego relaxes its attachments.

Mahayana and The Three Turnings of the Buddhist Teaching

Why the Mahayana Arose

Ordinary people wanted to practice the Dharma too, but they did not have circumstances that allowed them to become monks and nuns. Since the Buddha taught that one had to rely on one’s own experience in the end, there must be a way for non-monastic Buddhists to practice.

It is said by some Buddhist scholars that the Buddha “turned the wheel of Dharma” three times. That is, he taught the Dharma in different ways according to people’s capabilities. Thus, the Theravada (Way of the Elders), the Mahayana (the Great Way), and the Vajrayana (the Indestructible Way) were all complete paths to enlightenment, but each was better suited to different audiences (see the file Overview of Stages).

Mahayana was the form of Buddhism that was later carried to China and all of central and eastern Asia. It became popular because it encouraged ordinary people to learn and practice the Dharma, not only monks and nuns.

Mahayana Buddhism, the Great Way

The path of compassion is the essence of Mahayana: The Bodhisattva Path

The Mahayana is also known as the Bodhisattva Path. [Bodhisattva: Sanskrit: knowledge holder].

Mahayana begins with the commitment to help all sentient beings gain freedom from suffering and in so doing the Buddhist moves toward complete enlightenment by letting go of the ego’s illusions.

The Bodhisattva Vow

The bodhisattva vow is the commitment to put others before ourselves: “From today until attainment of enlightenment I will work for the benefit of all sentient beings.”

The bodhisattva vow means working with others, not just yourself. One metaphor for the bodhisattva path is the story of the butterfly. First it is wrapped in a cocoon and you could say it is only interested in itself. Then it emerges from the cocoon and it is interested in the whole world, as far as it can fly.

First one develops Maitri (Sanskrit: loving kindness, including being kind to oneself; making friends with oneself). Then one establishes relationships, communicating with others by opening to them, without becoming a nuisance or harming others. Third, one helps others without looking for something in return:

“The point of our making the first move or taking the bodhisattva vow is not to convert people to our particular view, necessarily; the idea is that we should contribute something to the world simply by our own way of relating, by our own gentleness.… It takes a long time and a long process of disciplined patience.” – Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, The Myth of Freedom

The Bodhisattva Path

Taking the bodhisattva vow implies that instead of defending ourselves while ignoring others, we become open to the world that we are living in. It means we are willing to take on greater responsibility than ourselves and our immediate family. We want to help all sentient beings “wake up” from suffering.

Bodhicitta

Bodhicitta is the “thought of complete enlightenment.” (Sanskrit: bodhi = knowledge, knowing; citta = thinking “with all my heart.”

The connection of mind and heart in Chinese is 心神合一(Xin Shen He Yi) (This was contributed by a former student Xiang Lin)

There are two types of bodhichitta:

Relative bodhicitta is the intention, aspiration to work for the benefit of all sentient beings; it is like “buying the ticket”

Absolute bodhicitta: the actual experience of egoless compassion: actually taking the journey, being “the traveler on the path.”

How to Practice the Bodhisattva Path: The Six Paramitas (Transcendent Virtues). The Paramitas actually appear in the original Sutras of the Theravadin tradition, but they became a central aspect of the Mahayana teachings. This teaching was directed to everyone, not just monks and nuns:

Generosity - offering the territory of our ego. Because these virtues are not intended to support our sense of ego, they are “transcendent.” If we are being generous and expecting something in return, really bargaining with our situation, that has a more limited result. (This is related to understanding karma.)

Discipline - arising from trust in oneself, not a moralistic or guilt-ridden sense of discipline. (Experience in individual retreat.)

Patience - working with our emotions through meditation, not always opting for pleasure and security, nor panicking at discomfort.

Exertion - willingness to work hard for the sake of others. Nothing is regarded as an absolute obstacle; no one is regarded as unworthy of compassion or absolutely evil or bad.

Meditation - willingness to work continuously with our ego-centeredness and “speed” (~ constantly occupying ourselves with mental activity) by resting the mind openly in the present moment.

Wisdom (Sanskrit: Prajña) Prajña means “higher knowledge” or “wisdom.” It comes to fruition when we experience complete two-fold egolessness. Mahayana describes two-fold egolessness:

Egolessness of self: At this stage Buddhists know there is no truly existing ego, but “moments of consciousness” still seem real.

Egolessness of other (all phenomena): Even the smallest observable moments of consciousness are not ultimately real. Each moment of consciousness appears according to conditions and causes of karma and is therefore relatively true; it is only by relationship to past moments that it appears. It doesn’t appear by itself.

Wisdom is the extension of recognizing impermanence and interdependence.

Someone who has wisdom also understands the consequences of his or her actions and understands the conditional nature of relationships.

Someone who has wisdom understands the inherent emptiness of all things that appear to exist. (The idea of emptiness became a central teaching and we will discuss it in the next class.)

Compassion and the Interdependent Self

In Buddhism, compassion is also described as the insight or openness in which you see yourself as interdependent with your world, as in the poem below. It is possible to feel the connection with all sentient beings, just as one naturally feels connected to family and loved ones.

Compassion for all sentient beings arises naturally.

The deepest view of compassion in Buddhism is more than the view of charity. It is more than following social rules so that we can feel good about ourselves. It is not just reasoning that we are better off than others so we should be generous. Although thinking that way can be helpful and it is not wrong, it is not the deepest understanding of compassion.

The deep understanding of Buddhist compassion is recognizing and feeling that the true “self” is interdependent or not completely separate from others. People who think of themselves as “better” and separated from those who are in need are not really separate from them.

Experientially, the insight in meditation that opens to compassion comes when there is a sense of gentleness and patience. This gentleness and patience is first kindness toward oneself (Sanskrit: maitri). From kindness toward oneself comes kindness toward others. Kindness toward others is compassion.

Poem on the Interdependent Self or “Interbeing”

Please Call Me By My True Names

By Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese monk (b. 1926 – present)

Don't say that I will depart tomorrow -- even today I am still arriving.

Look deeply: every second I am arriving to be a bud on a Spring branch, to be a tiny bird, with still-fragile wings, learning to sing in my new nest, to be a caterpillar in the heart of a flower, to be a jewel hiding itself in a stone.

I still arrive, in order to laugh and to cry, to fear and to hope. The rhythm of my heart is the birth and death of all that is alive.

I am a mayfly metamorphosing on the surface of the river. And I am the bird that swoops down to swallow the mayfly.

I am a frog swimming happily in the clear water of a pond. And I am the grass-snake that silently feeds itself on the frog.

I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones, my legs as thin as bamboo sticks. And I am the arms merchant, selling deadly weapons to Uganda.

I am the twelve-year-old girl, refugee on a small boat, who throws herself into the ocean after being raped by a sea pirate. And I am the pirate, my heart not yet capable of seeing and loving.

I am a member of the politburo, with plenty of power in my hands. And I am the man who has to pay his "debt of blood" to my people dying slowly in a forced-labor camp.

My joy is like Spring, so warm it makes flowers bloom all over the Earth. My pain is like a river of tears, so vast it fills the four oceans.

Please call me by my true names, so I can hear all my cries and laughter at once, so I can see that my joy and pain are one.

Please call me by my true names, so I can wake up and the door of my heart could be left open, the door of compassion.

The Two Accumulations

The practice of the Six Paramitas leads to the accumulation of merit (in terms of generating positive karma), and

the accumulation of wisdom. Wisdom does not come from meditation and study alone, but from compassionate action.

Contemplation Exercise:

Can a person have too much compassion? What is the Buddhist view? What is your view and how do you explain it?

The Perfection of Wisdom Sutras

Introduction to The Heart Sutra: the Mahayana Teaching on Emptiness (Sanskrit: Shunyata)

The full title of this Sutra is The Sutra Of The Heart Of Transcendent Knowledge. Historians say the earliest written version is from around 100 BCE, almost 400 years after the Buddha died. Nagarjuna is the Buddhist philosopher/scholar credited with writing down and explaining it in detail, although the Mahayana Schools believe that the Buddha spoke these words himself. This is possible because the Buddha’s teachings were preserved in an oral culture that relied on repetition and memory to pass the teachings on.

The Heart Sutra is one of the most well-known of Buddhist Sutras, and one that radically changed the focus of many students from self-liberation to working for the benefit of all beings (the bodhisattva path). This was the beginning of the Second Turning of the Wheel of Dharma (see file: Overview of Stages).

The Heart Sutra was so shocking for those who regarded the earlier teaching of the Buddha as absolute doctrine (dogma) that it is said 500 monks had heart attacks when they heard the Heart Sutra. (It is assumed they all recovered!)

Why did the Buddha present the Heart Sutra?

From the earliest time of the Buddha’s teaching he recognized that amongst his students there was a diversity of learning styles, spiritual inclinations and interests. He found that he had to teach differently in accord with different contexts to make a good connection with his audience.

Despite his insistence that one has to find the truth of teachings in one’s own experience, many of his older students treated the Buddha’s words as religious dogma, as if the words were the absolute truth themselves. The Buddha was concerned that they were not getting to the experience itself, only learning the words. The Heart Sutra was aimed at them as well as those who were more intellectually sophisticated, who knew there was a level of realization, an experience of wisdom, that was possible.

Theravada Buddhism (the Hinayana) is the oldest teaching, but by the time Buddhism began to expand and attract interest from all levels of Indian society, there were many well-educated people with philosophical questions about the nature of reality that did not seem to be completely answered in earlier sutras.

[Reading from the Heart Sutra]

The Essence of the Heart Sutra, the teaching on emptiness [Sanskrit: shunyata]

Form is emptiness,

Before we project our concepts onto our direct perception of experience, there is just form – the colorful, vivid, qualities that exist in every situation. Q. When do we encounter direct perception?

Evaluation of what we experience is created later in our minds, after initial direct perception.

So form itself is empty of our conceptions, our judgments. Form could be anything in subject/object experience: a garbage heap, the leaf on the Canadian flag, or even a face in a dream; a taste, a touch, an emotion, or an idea.

Q. How is this aspect of shunyata different from ordinary experience?

Emptiness is form,

Even to label things as “just empty” is a subtle way to clothe them in concept. “We have to feel them properly, not just try to put a veil of emptiness over them.” (Chogyam Trungpa). If practitioners just strip away concepts as a practice that could become could be an escape, a bias toward the idea of everything being empty.

First we see through the heavy conceptual projections, then we let go of the subtlety of labels, including the label “empty.”

Story of Suzuki Roshi’s funeral.

Emptiness is no other than form,

There is no way to appreciate emptiness other than through form.

There is no absolute void, just as there are no absolutely existing things.

Form and emptiness are inseparable; they are not two things.

Form is no other than emptiness.

Finally things are just what they are and there is no effort necessary to see them in a special way. The realization of emptiness is not a kind of inspired mystical state. Shunyata means the mind not dwelling (or fixating) on anything; completely open.

Shunyata is the complete absence of filters, things as they are without conceptualization or bias.

Words or concepts can only point to partial aspects of experience.

Analogy of “pointing to the moon.”

The meaning of the Sanskrit mantra “Gate, gate, paragate, parasamgate, bodhi svaha” is in items 1-4 above.

The first “Gate” overcomes the veil of emotions that cause conflict

The second “gate” overcomes believing appearances to be real,

Third, ”paragate” is non-dwelling, and

Fourth, “parasamgate” is “completely awake,” enlightenment.

Emptiness and Compassion

To the extent that one has understood and realized the origin of his or her own suffering, the suffering can be seen as empty. The same potential exists in others, although they may not know it.

As fixation on one’s own ego diminishes, our natural connectedness to others is revealed. Empathy and compassion come and go for most people depending on various causes and conditions. For the bodhisattva who realizes the empty nature of existence, compassion becomes continuous and it is not limited by particular causes and conditions. This is absolute bodhicitta.

Along the path of the bodhisattvas, as a practice for Mahayana students, it possible to exchange oneself for others in terms of feeling. Exchanging oneself for others is compassion.

Seeing the emptiness of suffering, absolute bodhicitta is unobstructed. Compassion for all sentient beings and oneself is natural and unbiased – compassion is not directed only at people we like, it comes naturally even when we think we have enemies or certain people are evil.

One takes no “credit” for genuine compassion; whatever merit or positive karma there may be is dedicated to all sentient beings. Thus, no further karma is produced.

**************************************

Contemplation:

How does contemplating the Heart Sutra affect your understanding of compassion?

Buddhism in India After the Buddha

By the second century CE the teachings of the Buddha had been codified and agreed on in the Thervada tradition, King Ashoka had established Buddhism across the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka. Ashoka also protected the rights of people who believed in Brahmanism and other spiritual traditions in India. (This kindness was repaid nine hundred years later when Buddhism was essentially destroyed in India. Much of the teaching was taken into various other traditions and respected even though the institutions were destroyed by 1100 CE.)

Some monasteries in India became universities and records indicate that for hundreds of years people from all over Asia came to study at places like Nalanda University, in Bihar, India. Buddhists all over Asia could trace their sources back to India.

While the Mahayana tradition thrived in northern India, the Theravadin tradition thrived in southern India and Sri Lanka. Both traditions were taken throughout Asia. The Theravada went as far as Indonesia in the south and the Mahayana went as far as Japan in the east and parts of Siberia in the North.

Mahayana: The Second Turning -- Relative and Absolute Truth

Relative truth describes the way the world of appearance works.

All phenomena are empty of conceptual meaning unless we organize our perception and provide a context. (The examples of ambiguous figures shown in class demonstrated this.)

In the relative truth, all that appears to be real is conditional and mutually dependent (interdependent).

To say something is conditional is to say it depends on causes and conditions. Your responses to the ambiguous figures exercise were relative. Relative truth is conditional truth and can be expressed through concepts.

To show that things are interdependent is to show that things do not truly exist independently. Relative truth, conventional meaning, is derived from interdependence.

The Buddhist teacher Nagarjuna (ca. 150–250 CE) applied the teaching of interdependence and summarized it this way: all things arise in dependence on causes and conditions and have no self-nature. (This agrees, at least to some extent, with modern social constructionist views in the social sciences.)

But, if everything is relative, does that mean that all our values are also relative? Is there really nothing wrong and nothing right? Are personal values just a matter of opinion and everyone’s opinion is equal?

Absolute Truth

In the Middle Way School of Buddhism there is absolute truth and it is called “emptiness” so that we challenge the solidity and fixation of our thoughts. Absolute truth is without conceptual reference points; it cannot be expressed fully by concepts because concepts only refer to other concepts. Absolute truth is unconditional and empty of our projections. It does not depend on causes and conditions. It cannot be described fully by concepts because is not “like” anything. But it is the basis of everything that arises.

In Mahayana Buddhism, there is both relative and absolute truth. Reality is not mere relativism. That is why it is called the Middle Way School of Mahayana Buddhism: it the middle way, neither extreme of relative or the extreme of absolute, but the two as inseparable.

We can infer absolute truth through:

studying the relative truth – through experiencing our world as relative truth; and

we can know absolute truth through direct experience. According to masters of meditation, we can directly experience, or at least glimpse, absolute truth ourselves when the mind rests in itself without holding on to concepts.

Seeing that all phenomena are empty of our concepts, then bodhicitta, awake mind, our natural intelligence, is unobstructed. Unobstructed mind sees interdependence and gives rise to compassion naturally. Recognizing the unobstructed mind is recognizing Buddha Nature.

Thus, emptiness and compassion are inseparable and the personal and social values we hold can reflect that. The six paramitas are an example and that is why they are known as “transcendent virtues.”

Nargarjuna in India and the later Middle Way Schools in China also fully acknowledged that relative truth was useful and necessary in diminishing the suffering we cause ourselves and others. Mahayana Buddhists fully accepted that is where students must begin.

Review of Emptiness as a Path to Compassion

To the extent that one has understood and experienced the origin of his or her own suffering (the ego), the suffering can be seen as empty. In other words, the ego begins to feel less solid but one’s natural intelligence gains confidence.

Buddhists teach that as fixation on one’s own ego diminishes, natural connectedness to others is revealed. This empathy and compassion is expected to come and go for most practitioners on the Mahayana path and depends on various causes and conditions. It does not stabilize all at once, but it increases progressively over time and with much practice.

Gradually, compassion for all sentient beings and oneself is natural and unbiased – compassion is not directed only toward people that the Mahayana Buddhist likes, it comes naturally even when others appear as enemies or evil people. For the accomplished practitioner of Mahayana Buddhism who realizes the empty nature of existence (the emptiness of all phenomena, self and other), compassion becomes continuous and it is not limited by particular causes and conditions. This is called absolute bodhicitta and wisdom, the sixth paramita.

With the development of wisdom comes more possibilities for skillful means – compassionate action -- knowing what to do that is truly helpful for others. (For example, as Buddhists see the emptiness of selfish accumulation and short-term profits, they could learn to preserve our natural resources and clean-up the environment. That is how Buddhists believe we could live on this planet more sustainably.)

One takes no “credit” for genuine compassion and compassionate action; whatever merit or positive karma there may be is dedicated to all sentient beings. Thus, no further karma is produced.

Chinese Buddhism: “Awake from the Bias of Words”

The emptiness of all phenomena does not mean that suffering is meaningless. Rather, it means that genuine compassion requires an unbiased view.

From a former student, Kaiyin Guo:

“从偏见的词句中醒悟”

"从" means "from". "偏见" means bias and here I add "的" behind "偏见" , so "偏见的" means "prejudiced", it become adj.

"词句" in Chinese means "words and sentences", in general it means “what we said.” Finally, "醒悟" means "awake and understand".

And I just recalled an idiom that I did not have chance to use for a long time, but it is very suitable for this sentence. "一视同仁"

"一视同仁" means treating anything and anyone equally without bias.

This came from Hanyu, who is one of leaders of ancient Chinese literature in the Tang dynasty (618-906 CE). The original text is "是故圣人一视而同仁,笃近而举远." It means that the sage treats anything and anyone equally without bias, and whether the people are close to him/her or not, sage always treats all the people with virtue and sincerity.

Historical Background of Chinese Buddhism

The earliest translation of Buddhist texts from India into classical Chinese began as early as the second century CE. At that time Daoism, the indigenous spirituality of ancient China, stressed inner cultivation and refining of the spirit. This fit very well with the Buddhist teachings on self-awareness through meditation, egolessness, and the eightfold path.

“Dao” translates as “the Way” and was considered to be the natural unfolding of the universe.

The Dao itself was considered to be the essence of all phenomena, and could be related to emptiness and interdependence in Mahayana Buddhism. This essence was not something that existed; it was a nameless, formless “nonbeing”.

But when the Dao manifested into the events and things that people experience, it was considered as “being.” “Nonbeing” and “Being” were the same or very similar to the absolute and relative truth taught in the Mahayana Middle Way School of Indian Buddhism.

Although there were some rivalries, Daoism and Buddhism coexisted for more than 1500 years in China.

Dharmaraksha was the Sanskrit name for a Chinese Buddhist monk who translated the Heart Sutra into classical Chinese and started Buddhist monasteries in the Dunhuang area of north China in the late second century CE.

Three types of monasteries in China developed:

Central monasteries were devoted primarily to study of texts and appealed to scholarly, educated people. These were supported by government leaders and so some monasteries grew wealthy and influential. Buddhism spread to southern China with the help of the ruling class in Nanjing. However, many monasteries were also subject to political favoritism.

Rural monasteries served local populations outside the cities. These became associated with devotional Buddhism as time went on and there was less emphasis on study and the basic practice of formless meditation.

But mountain and forest monasteries were created by Buddhists who wanted to devote much of their time to meditation and were less controlled by the government. These monasteries were often remote and poor financially, but they remained apart from the social and political strife.

By the third century a nunnery for Buddhist women was started in Chang’an and this lineage of Buddhist nuns carried forward to modern times.

Devotional Buddhism

In the 5th century CE Buddhist art started to appear in paintings and architecture in both North and South China and ordinary people were drawn to images of the Buddha and to Avalokitshevara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, Guanyin. (See figures 7.1 – 7.3 in the textbook.)

In the next class we will explore how devotional Buddhism was related to the understanding of emptiness and compassion.

Contemplation

Review: Overview of Progressive Stages on the Buddhist Path

The Middle Way School and The Heart Sutra taught that everything (including mental phenomena) is empty of self-nature; all phenomena do not exist the way we ordinarily think they do.

The Middle Way School introduced the teaching that each thing and each experience appears to be separate and self-existing, but it appears only in dependence on causes and conditions and is empty of the self-existence that we usually attribute to it.

In other words, each thing and each experience is relatively true or real, not absolutely true or real.

This view was further developed in China, but it was not the only view further developed in China.

Yogachara: the Mind Only School

Before we continue to trace Buddhism in China and Japan we need to look back again at another line of teaching that developed first in India around the third century, CE. For some Buddhists in ancient India the question remained, how do things even appear to exist? What is the basis for appearance?

The Mind Only School, also known as Yogachara Buddhism took a more direct, experiential approach (in addition to reasoning) to the question of how things even appear to exist.

Two Indian sages, Asanga and Vasabandu, developed the Mind Only School system and taught it at Nalanda University in ancient India.

They said that the division of each moment of awareness into an inner perceiving mind and an outer perceived object is a conceptual invention. It is ultimately an illusion.

The Mind Only school was also carried into China and later popularized by a monk known as Bodhidharma who gained support from the ruling classes. In China, the Mind Only School became known as Chan Buddhism.

A special tradition outside the scriptures;

With no dependence on words and letters.

A direct pointing into the mind;

Seeing there one’s own nature, and attaining Buddhahood.

-- Bodhidharma

Ordinary consciousness is deluded and takes the duality of perceiver and perceived to be ultimately real. The basis for all appearance is mind. In other words, everything is “mind,” but here mind does not mean our ordinary dualistic, subject/object consciousness that believes in an inner and outer world as separate and independent.

Vijñana, the Sanskrit word for the ordinary consciousness mind, is composed of vi which means “split” and jñana which means wisdom. The split is the illusory “perceiver/perceived” experience.

Vijñana, ordinary consciousness, is the mind that believes in the split between subject and object – duality.

Jñana is the innate wisdom mind always present but obscured by the delusions of ego and “split mind.” Everything is really inseparable from this mind, wisdom mind, or Buddha Nature.

Ordinary consciousness can feel like it is separate from the body, but even the experience of the body is still happening within the mind. So ordinary consciousness and mind itself are not really the same. The mind is like the ocean and consciousness is like a wave on the ocean.

Analogy: The wisdom mind is like the ocean. When a wave rises it may seem separate, but is a wave different from the ocean? Is it really something else, independent of the ocean?

![A term paper for the Buddhist Religions study (2000-2500 words) 5]()

In the Yogachara system of Buddhism, and in the Chinese Chan Buddhism tradition, what is ultimately real is the underlying, non-dual basic awareness itself, not separate from the mind, which is also called Buddha Nature. It is the recognition of this Buddha Nature which is the ultimate wisdom, awake mind, or jñana, that is real and absolute, “before” the apparent split into duality.

Excerpts from an Indian Buddhist Poem-- The Royal Song of Saraha, translated by Herbert Guenther:

All those with minds deluded by interpretative thoughts are in two minds and so discuss emptiness and compassion as two things.

When [in winter] still water by the wind is stirred,

It takes [as ice] the shape and texture of a rock.

When the deluded are disturbed by discursive thoughts,

That which is as yet unpatterned turns very hard and solid.

[Ultimately] There’s nothing to be negated, nothing to be

Affirmed or grasped; for it can never be conceived.

By the fragmentation of the intellect are the deluded fettered;

undivided and pure remains spontaneity [spontaneous wisdom].

Although scholars debated the Middle Way approach and the Mind Only/ approach both in India and in China, they both provide important insight for study.

The Third Turning: Beyond Duality: Buddha Nature [See File: Progressive Stages…]

All beings possess Buddha Nature; it is the same totally clear awareness that the Buddha realized when he became enlightened. Realizing our Buddha Nature is enlightenment.

Suffering arises only when we take appearances themselves to be real, including the appearance of a separate self – the knower. We commonly regard the subject/object experience as ultimately real. But it is only the non-dual awakened mind, our Buddha Nature that is real and independent of conditions.

“Just as space, being all-pervading, cannot be polluted because of its subtle nature; similarly, abiding everywhere among living beings, Buddha Nature remains unpolluted.” –Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (CTR)

Like a sun obscured by clouds, Buddhists recognize people cannot easily recognize Buddha Nature unless they are willing to commit themselves to a genuine spiritual path.

Implications for Compassionate Action: There are two components to compassion:

Prajña means wisdom: both learned wisdom and jñana, the direct experience of nonduality, become the highest prajña

Upaya – Skillful means, ways to express compassion through activity.

“Exchanging oneself for others” is the basic Mahayana practice called tonglen (in Tibetan) that can be incorporated into meditation practice.

Three Traditions in China

Although there were ten major schools of Buddhism, two of them survived to modern times: Chan Buddhism and Pure Land Buddhism (Jingtu). A third school, Shingon Buddhism will be discussed when we cover the Vajrayana.

Chan Buddhism preserved two of the major traditions of Buddhism: 1) the meditation training centers and 2) over time, monasteries dedicated to the study of Yogchara Sutras in Chinese based on the nondual view of Buddha Nature and Awake Mind.

Pure Land included rituals, prayers and devotional Buddhism which were accessible and inspiring to common people, not only the intellectual elite. To the right is Amitabha Buddha as he may have appeared in the Indian tradition and initially in China. He is red to symbolize the color of compassion and he sits on a lotus flower seat. The Lotus Sutra was a teaching that emphasized both the human Buddha, Gautama Buddha of the Theravadin tradition and the ideal form of the Buddha in the form of Amithabha, the Buddha of Compassion.

Instead of relying on oneself, which can generate self-centeredness, the practitioner relies on the power of Amitabha Buddha, humbly allowing oneself to be transformed.

In Pure Land Buddhism, as it was developed in China by Tanluan (476-542), there was little emphasis on studying the sutras for intellectual development or the meditation techniques of Chan Buddhism. In Pure Land Buddhism the ego and suffering are overcome by faith in Buddha Nature in the form of Amitabha Buddha (right) and vowing to help others.

Devotional forms of Buddhism in China eventually included androgynous forms of the Buddha such as the one depicted in this porcelain Guanyin statue from the Ming dynasty in China (right)

Some images are more clearly female form as this Buddha Kwan Yin statue below:

Japanese Buddhism