ECE 430 week 4 assignment (please DO NOT SEND ME A CHAT MESSAGE) (DO NOT CHANGE THE AMOUNT, PRICE IS SET) ONLY CONTACT ME BY MESSAGES-NO CHATS UNLESS I MESSAGE YOU BY CHAT AFTER I READ YOUR MESSAGE

Chapter 5

Assessment and Evaluation: The Background

© Blend Images/Ariel Skelley/The Agency Collection/Getty Images

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Describe historical points in the evolution of assessment and evaluation in the United States.

Identify the four essential purposes of assessment and evaluation.

Identify some of the most popular standardized tests used in early childhood education.

Compare and contrast formal and informal assessment.

Introduction

Chapter 1 provided a brief overview of the need for and functions of assessment and evaluation. As you will recall, assessment is the process of gathering information for the purpose of observation and planning for next steps, while evaluation uses the gathered information to make judgments. If, for example, an assessment of a new infant's reflexes shows potential problems, further assessments will be conducted and evaluations made to determine appropriate treatments. In this chapter, we will expand on these definitions and explanations, as well as provide case studies that demonstrate the importance of using assessments and evaluations in early education. As is often the case, we will rely on the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) as a valuable resource, although we will refer to other expert sources as well.

5.1 Assessment and Evaluation: A Brief History

© Dtimiraos/E+/Getty Images

Doctors conduct assessments and evaluations, techniques also employed by teachers.

Tests related to school performance had their origins in the early 20th century with the creation in France of the "Binet Scale," designed to measure intelligence and, thus, predict future success or failure in education. Later, the scale was revised at Stanford University by the psychologist Lewis Terman and became known as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, complete with the concept of intelligence quotient, or IQ (Gullo, 2005). In subsequent years, various modifications were made to the Stanford-Binet, most recently in 2003.

Competing with the Stanford-Binet were the intelligence tests developed by David Wechsler in the 1940s. By 1967, he had published a preschool version that lowered the age range to less than 3 years (Wechsler, 1989). Both the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) are administered to children individually. Both contain a number of sub-sections that test abilities such as verbal and quantitative skills, short-term memory, and reasoning. It is important to remember that while intelligence tests are useful for understanding children's cognitive capabilities, they do not relate directly to educational performance.

The Emergence of Standardized Early Childhood Testing

Public Domain

Edward Lee Thorndike introduced the first standardized test in 1909.

The first standardized test directly related to education was the 1909 Thorndike Handwriting Scale, and testing became increasingly more common throughout the 1930s and beyond (Perrone, 1990). When a test is standardized, it is administered and scored consistently for all test takers. The Thorndike Handwriting Scale was a norm-referenced test, so called because performance was measured relative to that of all other students taking the test. It was, however, a test for children in the fifth grade and beyond; testing for younger children was not seen as necessary at this time.

The need for early childhood testing and program evaluations arose in the 1960s, with the emergence of Head Start and the many variations of curricula that were created. The development of these programs was one of the outcomes of President Lyndon Johnson's "War on Poverty." Because they were federally funded, evaluations were necessary for continued financial support. The evaluation instruments that were developed were less than perfect, but they did contribute to what was then a growing field of early childhood assessment, and they continued to improve over time (Gullo, 2005). Although more than 200 preschool tests were published over a 10-year period, even more were needed after the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, P.L. 94-142 in 1975. For example, such developmental instruments as the Bayley Scales could be used to identify potential developmental delays before a child's entrance into a Head Start program. And the Test of Early Language Development could be used either before or during the program. Its purpose has been to "identify children who are significantly language delayed as compared to their age peers, to assess their language strengths, and to document their progress as a result of intervention" (Gullo, 2005, p. 158).

The development of such widespread testing was, to a great extent, responsible for teachers beginning to "teach to the test," or focusing the curriculum primarily on what would appear on an upcoming standardized test. Assessment expert James Popham (2003) expressed his concerns about teaching in this way:

[T]eachers must aim their instruction not at the tests, but toward the skill, knowledge, or affect that those tests represent. . . . Preoccupation with test scores becomes so profound that many teachers and administrators mistakenly succumb to the belief that increased test scores are appropriate educational targets. They're not. (p. 27)

Along with teaching to the test, early childhood educators, sometimes at the insistence of their administrators, began watering down the elementary curriculum in the belief that scores would be higher. Somehow forgotten by many was the fact that

young children are active learners by nature. They learn and develop best when they have opportunities to manipulate concrete objects. . . . They construct their knowledge about the world through experiences that involve interactions with objects and people in their environment. . . . They are concrete thinkers and interactive learners; they are active thinkers and active learners. (Gullo, 2005, pp. 36–37)

Concerns over teaching to the test and inappropriately watering down the curriculum led to the writing of position papers on the part of NAEYC and other organizations from the 1980s onward. For example, the National Association of State Boards of Education stated in 1988, that "Preschool, kindergarten and primary grade teachers report an increasing use of standardized tests, worksheets and workbooks, ability grouping, retention and other practices that focus on academic skills too early and in inappropriate ways" (p. 3). Authoritative statements such as these, coupled with the popularity of NAEYC's publications, made it possible for early educators to resist some inappropriate curricula and testing. A move toward alternative assessment (also known as authentic assessment) began to emerge. This type of assessment represents a shift away from standardized testing and makes use of methods that assess children's progress in ways that are more meaningful to the learner, both inside and outside the classroom. Both child and teacher are involved, and materials may be tangible products, portfolio collections of work, and other teacher documentation. Authentic assessment will be discussed later in this chapter, as well as in Chapter 6.

The Current State of Standards-Based Testing

Today, we continue to find much standardized testing in the classroom, particularly within the constraints of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2002. This act, a product of the George W. Bush administration, brought a standards-based approach to educational reform. Public schools, their districts, and their states were to be held accountable for the annual yearly progress of all their students. The act affected educational requirements and funding nationally, but individual states were given the power to create their own assessment of basic skills in literacy and mathematics. Although the act mandated yearly testing only from grade 3 onward, many states instituted tests for younger children as well. Despite the pressures related to such testing, many educators continued to work toward assessments that would be more authentic, or meaningful, to both their students and themselves. Subsequent education legislation under Barack Obama's administration became known as Race to the Top (RTTT), with a focus on providing more flexibility to states under the NCLB requirements. Most recently, a Race to the Top—Early Learning Challenge (RTTT – ELC) was announced. Its focus was to improve early learning programs, from birth to age 5, in three ways:

"increase the number and percentage of low-income and disadvantaged children in each age group of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers who are enrolled in high-quality early learning programs"

"design and implement an integrated system of high-quality early learning programs and services"

"ensure that any use of assessments conforms with the recommendations of the National Research Council's report on early childhood" (U.S. Department of Education, 2012)

Note particularly the requirements of the last bullet point. The National Research Council's extensive report from 2008 covers the many kinds of assessments given to infants and young children, such as those relating to cognitive, social, and physical development, and progress in academic subjects. It also addresses assessments focused on entire programs, as well as the need for well-trained assessors for many of the assessments given to young children (Snow & Van Hemel, 2008).

ECE in Motion: Tests and Teaching Strategies

Educators talk about the issue of tailoring instruction to fit standardized tests.

Critical Thinking Question

Do you think it is more effective to base instruction on established tests, or to create a tailored curriculum and then design the test to match instruction?

As of December 2011, nine states of the 35 that had applied for RTTT—ELC had received grants. In its announcement of the successful applicants, the White House press office stated that key reforms would include "aligning and raising standards for existing early learning and development programs; improving training and support for the early learning workforce through evidence-based practices; and building roust evaluation systems that promote effective practices and

| Table 5.1: Commonly Used Standardized Tests | ||||

| Test | Category | most recent edition | Ages tested | Skills tested |

| AGS Early Screening Profiles | Developmental screening | 1990 | 2–6 | Cognitive, language, motor, social development; self-help skills |

| Basic School Skills Inventory | Readiness | 1998 | 4–8 | Oral language, reading, math, behavior, daily living skills |

| Bayley Scales of Infant Development | Developmental screening | 1993 | Birth–2½ | Mental, motor, behavior |

| Boehm Test of Basic Concepts | Readiness | 2000 | 3–5 | Size, direction, spatial relationships, quantity |

| Brigance Diagnostic Inventory | Assessment/Readiness | 2004 | Under 7 | Knowledge, comprehension, pre-academics, psychomotor, self-help, language |

| California Achievement Test (CAT) | Educational achievement | 1996 | School age | Literacy, spelling, language, math, science, social studies, study skills |

| Child Development Inventory (CDI) | Developmental screening | 1992 | 15 months–6 | Social development, self-help, motor, language, letters, numbers |

| Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning (DIAL-3) | Developmental screening | 2011 | 2–6 | Motor, conceptual, language, self-help skills; social development |

| Early Screening Inventory | Developmental screening to identify at-risk children | 2008 | N/A | Cognitive, social/emotional, motor development; communication, adaptive behaviors |

| Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) | Educational achievement | 2007 | K–grade 3 | Language, math |

| Metropolitan Achievement Tests | Educational achievement | 2000 | School age | Language, math, social studies, science |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | Diagnostic test | 2007 | 2½ and up | Receptive vocabulary |

| Preschool Language Scale | Diagnostic test | 2011 | Birth–7 | Auditory comprehension, communication |

| Screening | Developmental test | 2001 | K and up | Reasoning, general information related to giftedness |

| Stanford Early Achievement Test | Achievement | 2010 | K–grade 1 | Language, math |

| Test of Early Language Development (TELD) | Diagnostic test | 1999 | 2–7 | Receptive and expressive language related to language delays |

| Wechsler Individual Achievement Test | Achievement | 2009 | School age | Comprehensive language, math |

| Wechsler Preschool & Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) | Diagnostic test | 2012 | 3–7 | Intelligence: verbal, performance |

| Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) | Achievement | 2006 | School age | Language, math |

programs to help parents make informed decisions" (White House, 2011). Thus, the development of appropriate assessment and evaluation in early childhood continues.

The Most Widely Used Standardized Tests

Readers of this text who pursue a career in early childhood education will, no doubt, encounter at least one or more standardized tests for children and perhaps be expected toadminister them. Table 5.1 lists some of the most commonly used, high-quality tests. Note that the names of the tests have been alphabetized for easy reference and that this list includes tests of diverse types, such as developmental screenings, intelligence tests, and educational achievement tests.

5.2 The Purpose of Assessment and Evaluation

According to NAEYC,

assessment of children's development and learning is essential for teachers and programs in order to plan, implement, and evaluate the effectiveness of the classroom experiences they provide. Assessment also is a tool for monitoring children's progress toward a program's desired goals . . . [and] sound assessment takes into consideration such factors as a child's facility in English and stage of linguistic development in the home language. (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, pp. 21–22)

In the following sections, the components of this statement by NAEYC are each addressed.

Planning and Adapting a Curriculum

A curriculum for young children should never be totally set in stone, kept the same way from year to year simply because it worked in earlier times. Different children have differentinterests and needs, and changes take place within the community and culture. Knowing how and when to adapt or alter curriculum, as well as how to create original plans, is achieved in part through assessing the interests, capabilities, and needs of the center's or school's children.

Assessment for this purpose is stated by NAEYC as "planning and adapting curriculum to meet each child's developmental and learning needs" (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 178). The National Education Goals Panel, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education, stated this first purpose as "assessing to promote children's learning and development" (Gullo, 2005, p. 22). And in the words of Brough and Pool (2005), assessment is meant "to inform the teacher about effectiveness of the curriculum approach and instructional strategies used to present the objectives to the students. . . . [W]ithout well-planned effective assessment, educators lack data to make critical decisions about teaching and learning" (p. 196).

Ongoing, frequently administered assessment in a center or classroom is referred to as formative assessment. Its purpose is to check into children's development and learning to determine what can be done to help them continue to improve. Such "assessment of the child is implemented on a regular basis to determine progress and to suggest modifications that need to be made to insure progress" (Gullo, 2005, p. 137). From the viewpoint of NAEYC, there must be an assessment plan that is systematic and ongoing, one "that is clearly written, well-organized, complete, comprehensive, and well-understood by administrators, teachers, and families" (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 248). In addition, ongoing assessments should address the whole child: cognitive, social, emotional, and physical. Informal observations of preschoolers' use of a newly combined block-and-housekeeping center could be an example of formative assessment. Results might lead to the realization that a few children need some intervention from the teacher, perhaps in the form of playing with them for a while to model play possibilities.

Without ongoing formative assessment, a school year may end with only the final, or summative evaluation, providing unwelcome surprises for the families and no possible ways for the teachers to alter the curriculum to improve children's progress. A summative evaluation tells educators the end results of their teaching of a unit, a project, or an entire semester or year. Standardized achievement tests are an example of summative evaluation, as are report cards. Summative evaluations might even come much later when the long-term effects of an experimental curriculum are seen. Such was the case in evaluations of the different models of the original Head Start programs, when it appeared that the initial academicbenefits wore off by the third grade. Those data, however, were not considered the very final summative evaluation. Children's progress was followed into young adulthood, where it was found that the truly long-term benefits were positive (Zigler & Muenchow, 1992).

© Stockbyte/Stockbyte/Thinkstock

Common assessments provide both formative and summative information. They help teachers identify challenges individual students are facing.

When there is more than one teacher for an age- or grade-level of children, assessing by means of common assessment can be a positive approach to learning more about children's progress. Common assessments are created collaboratively by the teachers as a way to plan instruction, identify difficulties their individual children are having, and improve their own teaching. Common assessments can be both formative and summative.

Whether done collaboratively or individually, some assessment methods are used to determine the need for curriculum creation and alteration or updating. Specific examples will be described and discussed in the upcoming section Two Approaches to Assessment of Young Children. As a general statement, however, the intent of appropriate assessment is to see what needs to be done with the curriculum rather than to put the burden on the children, to try to "fix" them. The following case study demonstrates how one group of teachers collaborates on unit learning and how an informal, formative assessment led one of them in a different direction.

CASE STUDY:

Assessing Curriculum for the Benefit of Children's Learning

As part of a team of three kindergarten teachers, Judy has participated for the past four years in a study unit that takes place every spring called "It's Circus Time!" The teachers coordinate with the physical education teacher to create various age-appropriate tricks to do for an audience. Classes read books about the circus, watch videos of real circuses, and even decorate their rooms like a big top. Until this year, Judy's children have all loved it. For unidentified reasons, however, this year's children have been largely unenthusiastic, going through the activities as required but without enjoyment.

Judy, mystified, decides to discuss the problem with the class. During group time, she asks them directly if they can tell her what the problem is. "The children in the other kindergartens love this unit," she says, a little surprised at the defensiveness in her voice. No one seems to have a good answer. The children just are not interested.

One day, during free choice time, Judy observes the children's preferences closely. She sees several gravitating toward the books they read during their last unit, "Life under the Seas." They even hold stuffed dolphins and fish on their laps while they look at the books. Judy decides that some informal assessment is in order. She has already engaged in direct observation. Now, she will take an informal verbal survey to determine what is going on.

During group time, Judy asks the class, "Do you miss our undersea studies?" Almost everyone nods a big yes.

"Would you like to learn more about the ocean than study the circus?"

This time the yes is out loud. One child says, "We didn't get to do it long enough!" Another adds, "I want to go to the aquarium again."

A bit of applause follows. Judy gulps inwardly, knowing what this will mean if she follows through: The other teachers may well be annoyed that she is not participating, the parents will be disappointed that their children will not be performing, and she will have to revise the list of standards that would have been met by the circus unit. She is well aware that the collaborative approach the teachers took will be endangered, but she is also aware that the needs of her children come first and that she works with a group of teachers who feel the same way.

Thus, Judy decides to revise her curriculum plan based on this informal assessment of the children's interests. She finds that the other teachers, after some argument, are reasonably understanding; the parents barely mention the change when informed of it; and standards can be aligned with the expanded curriculum with relative ease. The big top decorations come down, the room again turns into an under-the-sea atmosphere, and almost everyone is pleased to gain more in-depth knowledge about the ocean. Two boys who state their preference for circus performance are permitted to join another class during their physical education periods.

When the time for the circus performance arrives, two parents from Judy's class show up to watch their boys perform. The rest of the class is perfectly happy to sit on the sidelines and applaud.

Think About It

Would you have made the same decision Judy did? Would it have taken some courage? What if the teachers had remained upset about the change? What if the parents were vocally disappointed about not seeing their children perform in the circus? What are your arguments for making your decision?

Improving Teacher and Program Effectiveness

© iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Students benefit from enhanced learning when course curriculum is adapted to match their interests. While one class might be particularly enthralled with all things "under the sea," others might be more captivated by the circus.

All states have some way of identifying teacher—as well as program or school—effectiveness through assessment and evaluation of children's progress. NAEYC defines this "beneficial purpose" as "evaluating and improving teaching effectiveness" (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 178). The National Education Goals Panel described this as "assessing academic achievement to hold individual students, teachers, and schools accountable" (Gullo, 2005, p. 27). In the words of a researcher who was speaking of programs, evaluation should "provide accountability data on program outcomes for the purpose of program improvement" (Slentz, 2008, p. 14). Passage of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2002 alerted schools to the issue of accountability as never before. As mentioned earlier, testing was mandated and instituted for grades 3 and above, but many districts across the United States began testing younger children as well, as preparation for the accountability that would soon matter for their programs.

Although the NCLB has put more outside pressure on individual teachers and programs, the concept of using children's progress as a "beneficial purpose" of evaluating teacher effectiveness is not a new one. A characteristic of effective assessments has always been the inclusion of teaching that is guided by corrective feedback for teachers as well as for children. Accurate self-assessment is a core activity related to suchfeedback, and effective teachers openly model their self-assessments so that students can learn to do so themselves.

Examples of teacher self-assessment techniques include thinking aloud with children listening, emphasizing the fact that teaching and learning often include making mistakes and that is okay, engaging in activities that are new and challenging and then reflecting on them, and providing examples of good work and best practice (Brough & Pool, 2005). Case Study: Modeling Self-Assessment in the Preschool demonstrates that, even in preschool, self-assessments are possible for both teachers and children.

CASE STUDY:

Modeling Self-Assessment in the Preschool

Allison teaches in a mixed-age class of 3- to 5-year-olds. Morning snack time is decided individually as children feel hungry and join one or two friends at a small table in the back of the room. They know they are permitted one visit only to the snack table during the morning and, after a few false starts, all but the 3-year-olds have gained enough self-discipline to comply. Occasionally one of the younger children will quietly return a second time or neglect to clean up afterward, but for the most part they follow the rules.

Allison, on the other hand, has felt that the rules do not apply to her. She carries her coffee cup around all morning and occasionally reaches for a graham cracker from the master supply whenever she feels the need. One morning, a mother who volunteers frequently in the class comments, "It used to bother me that you carry your cup around. But now I think it's probably all right since the kids can get their snack whenever they want."

Allison is a bit taken aback by the comment, especially because the mother apparently has not observed her delving into the graham crackers. Reminding herself that it is important to be a role model and also important to let children know that adults are at times imperfect, Allison decides to share with the class her realization that she needs to change her behavior. This will be one way to engage in some self-assessment, and also demonstrate to the class how it can be done. The next day during circle time, she first reviews with the class the rules about using the snack table. Then she says, "I have been thinking that I should obey the same rules," and announces that she will no longer carry her cup around with her and that she will eat her snack at the table and have only one serving. "I think that's more fair, don't you?" she asks.

The children look a bit puzzled, and Allison realizes they probably believe that adults can behave as they choose, making her definition of fairness a bit over their heads. Nevertheless, they are happy to have their teacher join them each morning at the snack table, and Allison is careful to take turns with every child. They would certainly understand the unfairness of doing otherwise! While there, she continues to demonstrate her self-assessment by stating her behaviors aloud, such as, "Now, I'm going to clean up. I've spilled a little, so I'll use the sponge to wipe up. That's our rule."

Allison notes that, within a few days, every child in the class participates perfectly at the snack table, even the 3-year-olds. Sometimes a child even states something like, "I just spilled, so I'm going to sponge it up."

Think About It

Very young children can learn about self-assessment, but demonstration accompanied by explanation teaches it best. One part of the preschool curriculum includes learning social behaviors such as these. How might Allison extend her lesson so the children would begin to use self-assessment in new ways?

Tracking Children's Progress for Teachers and Families

© iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Teachers should always act as an example by modeling andexplaining the behavior they want their students to exhibit.

Families as well as teachers need ongoing and continuous information about their children's progress, or formative assessment. They may also be in a position to provide information that teachers need. According to NAEYC, ongoing assessments "are based on multiple sources of information," including "observations by teachers and specialists and also information from parents" (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 247). Returning to our earlier example of preschoolersneeding teacher assistance to learn to play in the block-and-housekeeping center, it might be that parents feel their neighborhood is unsafe, requiring them to keep their children inside watching television much of the time. When they share this information with the teacher and the teacher shares observations of the children's play, joint planning can take place. For example, if the teacher describes or demonstrates how she plays with the children, the parents might be encouraged to do the same.

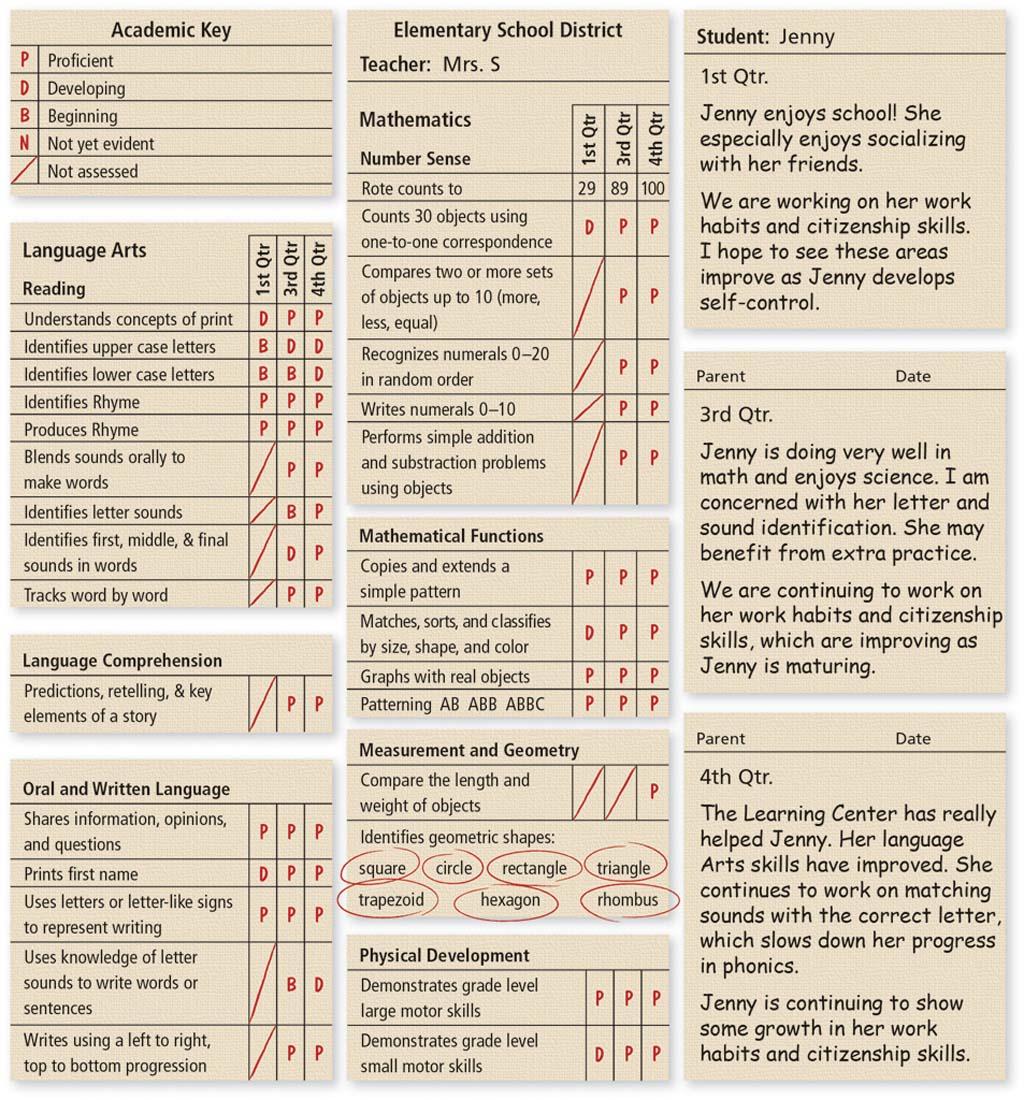

One method that teachers and families rely on to share both ongoing assessment and summative evaluations is report cards. These typically start formally in kindergarten, but preschools sometimes produce them as well. The following case studies present samples of report cards for the early years, along with some opportunities to read between the lines. Information about what really happened to the children described in the case studies is supplied in the Reflections and Critical Thinking section at the end of the chapter. If you are curious about the answers, please wait to read them until you have supplied your own!

CASE STUDY:

Sample Kindergarten Report Card

Figure 5.1 represents a kindergarten report card that shows an effort on the part of the school district to be developmentally appropriate in its grading of kindergartners. Grades are not yet used, but a three-tier rating system demonstrates each child's growth.

Think About It

Examine the ratings and teacher comments for Jenny in language and math. Which subject provides her more success? Look over the teacher's comments for each quarter. What are Jenny's greatest challenges as a kindergarten student? What should be done with children like this? Should they be held back a year? Should the curriculum or teaching methodology be altered to meet their needs? If so, how might you do it? If not, why would it be a bad idea? What would you hope to see in terms of teacher-family interactions during this kindergarten year?

Figure 5.1: Sample kindergarten report card

Click the figure below to view an enlarged version.

CASE STUDY:

Sample First Grade Report Card

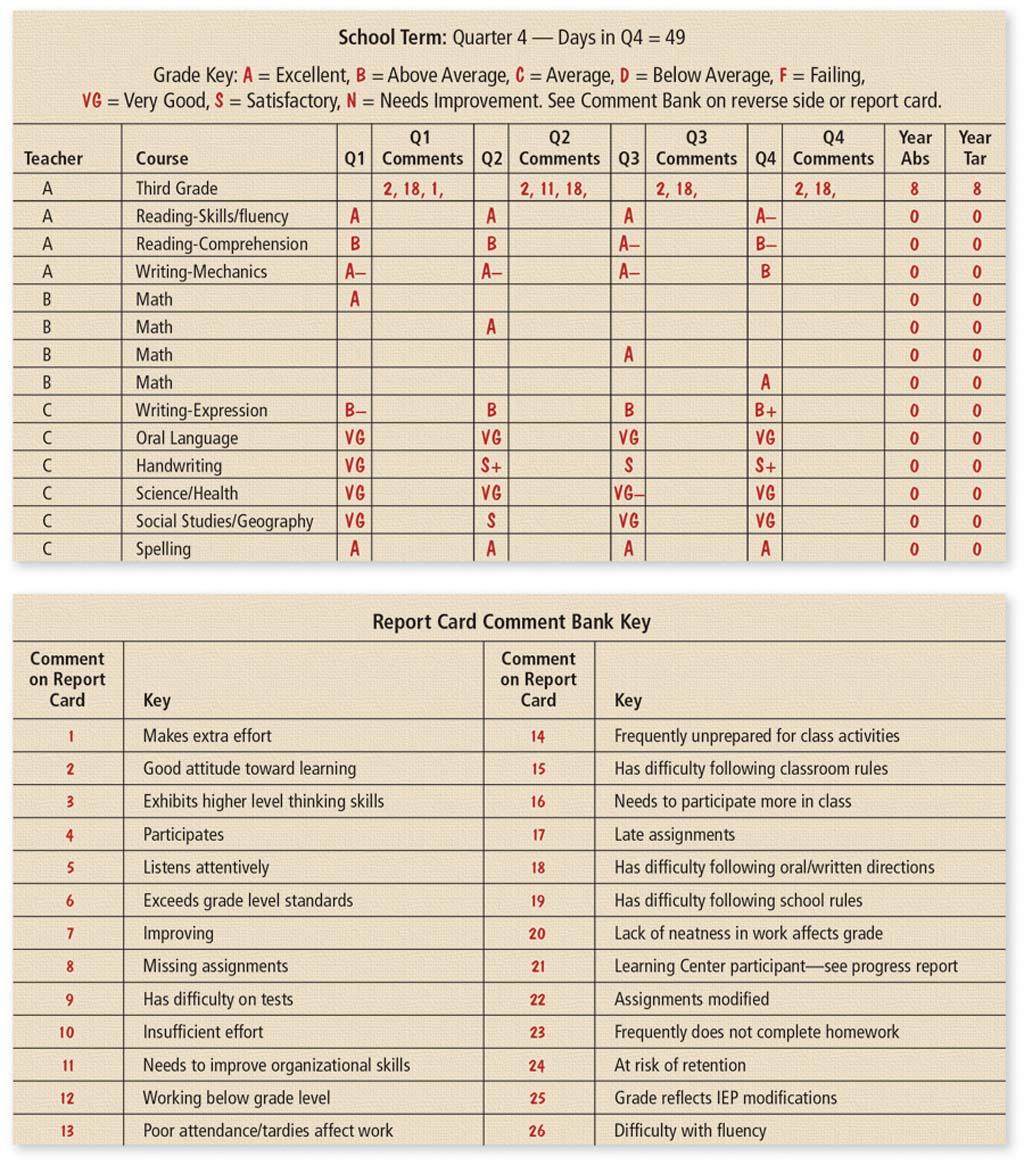

In first and second grade, the terminology that tells how well a child is doing tends to remain the same as in kindergarten. In the following report card (Figure 5.2), a different school district in a different state chose to use somewhat different terminology, but the intent is the same: a system that is informative, but not overly formal and intimidating.

Think About It

As you note the grades Ben has made and read the teacher's comments, what conclusions do you reach about Ben's greatest strengths and "Developing" areas? (Refer also to the comments under "Science & Health," a subject taught by another teacher.) Can you think of some ways the teacher might help Ben improve in the areas that seem difficult for him?

Ben left his school after the first term. What challenges might he face in his new situation? If you were Ben's parent, what would you want the new teacher to know, and what would you want to let evolve naturally?

Figure 5.2: Sample first grade report card

Click the figure below to view an enlarged version.

CASE STUDY:

Sample Third Grade Report Card

By the third grade, many report card models become more formal. In the sample report card shown in Figure 5.3 at right, letter grades now replace the earlier "Proficient, Developing, and Beginning" or "Applying/Understanding, Developing, Not Applying/Not Understanding" terminology. In this case, there is now a math specialist, while the homeroom teacher is in charge of evaluating literacy and other subjects. Perhaps most notable is the new lack of a personalized note from the teacher. Instead, there is a numerical code that the teacher enters in the Comments column.

Figure 5.3: Sample third grade report card

Click the figure below to view an enlarged version.

Think About It

From the point of view of the teacher, the school, and the school district, what do you think are the reasons for these changes? From the point of view of a parent, how would you respond to the changes? In both cases, are there pluses as well as minuses? What are they?

Look now at the Comment numbers for Dee. What might they tell you about her? Are there ongoing problems? If so, do you think they are being dealt with based on teacher comments over time?

Screening for Special Needs

Young children with disabilities have been a focus of federal legislation since the passage of PL 94-142 in 1975, titled the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. For the first time, such children were guaranteed equal education in public schools receiving funds from the federal government. In 1986, amendments to the law strengthened the support for early childhood, so that provisions begin at birth. In 1990, PL 101-576, or the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), added a requirement that the needs of all children must be met within an early childhood program. What had previously been called mainstreaming was now called inclusion (Gullo, 2005). The idea behind mainstreaming was to invite children with special needs into the regular classroom. Inclusion, on the other hand, assumes that everyone is included from the start, that there are no outsiders in need of an invitation. Such an approach to early education indicates the importance of regarding young children on a continuum of development rather than an either/or designation of "regular" and "special."

NAEYC identifies the federally required purpose of assessment as "screening and diagnosis of children with disabilities or special learning or developmental needs" (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 247). Slentz (2008) defines this purpose as "to diagnose strengths and areas of need to support development, instruction, and/or behavior. To diagnose the severity and nature of special needs, and establish program eligibility" (p. 14). In the words of the National Education Goals Panel, such assessment means "identifying children for health and special services." The panel defined special needs as "blindness, deafness, speech and language disabilities, cognitive delays, emotional disturbance, learning disabilities, and motor impairment" (Gullo, 2005, p. 23). Teachers and caregivers can expect to participate in initial screening, but once that is done, further tests are undertaken by specialists appropriate to the situation. Case Study: Two Children, Two Approaches shows how the federal requirements were carried out in one kindergarten class. This case also demonstrates how vital assessment is "because positive developmental and academic outcomes are associated with early identification of and attention to problems" (Slentz, 2008, p. 15).

Whatever the purpose might be for assessment and evaluation, here is a short list of some important things to remember (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009):

Teachers need to engage continually in assessment, keeping in mind that its goal is to improve both teaching and learning.

There is wide variance between individual children; they should be allowed to demonstrate their competence in multiple ways, not just according to what is easiest for the teacher. This is especially important when decisions will have a major impact, e.g., placement or screening for special needs.

Families should be called on whenever possible to contribute information about their children; this information should be an integral part of assessment.

Assessment should be geared toward goals that are developmentally appropriate and educationally important.

CASE STUDY:

Two Children, Two Approaches

At the beginning of the kindergarten school year, Ms. Davidson was quickly able to identify two children who would need some special assistance. Katie had difficulty making a number of sounds, and her speech was sometimes difficult to understand. Romero found it impossible to sit still for more than a minute, to keep from poking other children, or to control his very loud voice.

Help for Katie arrived almost immediately. She had spent the previous year and a half in a Head Start program and had already been screened, her problems had been identified, and an individual plan had been created and approved. The plan included a twice-a-week specialist who simply showed up one morning in Ms. Davidson's classroom, asking that she be allowed to work with Katie at a small table in the back of the room. Their previous experiences had, no doubt, beenpositive, because Katie was delighted to see her old friend. Within a short time, the specialist asked Ms. Davidson if she might include a few other children as well. Soon, a number of kindergartners were vying for spots at Katie's table so that they could play the fun games too. Within about two months, the specialist deemed Katie improved enough that she would come only once a week. By the end of the school year, a conference was held with Ms. Davidson, the specialist, and Katie's grandmother, who was raising her. Katie's speech was now almost perfect, and it was decided that the plan was no longer needed.

Romero was another story. Kindergarten was his first school experience, so initial screening was yet to be done. After observing him for a few days, Ms. Davidson asked the principal to observe as well. Afterward, they agreed that the district office should be contacted and further observation requested. It was at least a month before the very busy school psychologist could make an appearance but, once he did, Ms. Davidson requested that he observe all her interactions with Romero as well as focusing on Romero himself.

The psychologist remained about an hour, reassured Ms. Davidson that her interactions with Romero were excellent, and said he was ready to discuss a plan for Romero. Ms. Davidson especially wanted Romero to learn to control his behavior on his own, so it was decided that he could learn to predict for himself when he was about to engage in inappropriate behaviors. Then, he would remove himself from the group to sit in his favorite beanbag chair for a bit. Getting to this point would take some time, so for the time being, a plan of rewards for appropriate behavior would also be instituted.

A follow-up meeting with Romero's mother revealed that his problems had been hers when she was younger and that "I don't want him to go through what I did." Thus, she was entirely amenable to a plan of rewards for improved behaviors, as well as the longer-term plan for self-correction. Ms. Davidson found the reactions of the rest of the class interesting, because only Romero was receiving small snacks and occasional educational toys. Without having to discuss any of this with them, she observed that they seemed to understand Romero's need and accept what was happening. Whenever he received a reward along with an explanation and compliment, they simply looked on for a moment and then returned to whatever they were doing. Ms. Davidson even found a way to give Romero a chance to shine as a class leader once she discovered that his loud voice was accompanied by serious musical talent. When it was time to lead a song, she simply stepped aside and let Romero take over.

Unlike Katie's, Romero's challenges did not disappear at the end of the year, and further observations and diagnosis would be done at the beginning of first grade.

5.3 Two Approaches to Assessment of Young Children

For students of any age, early childhood through adulthood, two basic approaches to assessment and evaluation can be accessed: formal and informal. In the next section, we will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches in the context of early childhood education.

Formal Assessment and Evaluation

Formal assessment and evaluation consists of standardized tests, that is, tests that have been rigorously evaluated to ensure that they reliably compare the competence of one individual child to others with similar backgrounds or characteristics, and that they do so with fairness. You will recall that the Thorndike Handwriting Test, fulfilling these qualifications, was called norm-referenced. Although standardized tests may be designed for different purposes, such as special education screening or achievement testing, they have the following characteristics in common:

A specifically stated purpose that guides each application of the test

Established procedures for administering the test that are not deviated from

Meaningful interpretations of results that are described for test givers and graders

A clearly stated description of the sample group of students on which the test was developed

Clearly stated limitations of the test (Gullo, 2005)

There are many standardized tests to choose from for young children and the programs they attend. Although standardized tests have existed since the early years of the 20th century, their numbers increased with the advent of Head Start in the 1960s and have continued to grow with the introduction of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002. These tests may have any number of purposes, such as evaluating children's language development or early literacy skills, mathematics ability, motor capabilities, temperament and behavior, or general intelligence.

Although formal tests have the advantage of standardization, thus ensuring some measure of fairness, they present only a snapshot in time. As NAEYC points out, "Sound assessment of young children is challenging because they develop and learn in ways that are characteristically uneven and embedded within the specific cultural and linguistic contexts in which they live" (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 22). In addition, if a child is hungry, tired, upset, fidgety, or uncooperative, the results might well vary extensively from one day to the next. Many young children do not yet have the verbal or cognitive skills to do well on a structured formal test. Finally, tests may be standardized across some criteria such as age and gender, but neglect other criteria such as class, ethnicity, or English language competence. Thus, it is important to assess in multiple forms.

Informal Assessment and Evaluation

The less formal methods of assessment and evaluation are often presented as an alternative to standardized testing. The intent of using them is to assess children's progress in ways that are more authentic to their lives. Thus, the various informal approaches are also referred to as authentic assessment or alternative assessment. In addition, they provide good ways to engage in formative assessment so that instruction can be altered for better learning experiences.

Simply because these methods are informal, however, does not mean that one should be less careful when using them. Observation methods, for example, may be biased based on the observer's opinion of a child. Checklists might lead to less bias, but they can also leave out important behaviors to look for. Multiple methods of assessment are necessary for the full picture of a child, a class, a teacher, or a center or school. Following are explanations of authentic or alternative assessment listed alphabetically. In Chapter 6, you will haveopportunities to explore them further.

Anecdotal Records

This might be the most informal observational technique, but it can still provide useful information if observers have specific behaviors they are looking for. Focused on a specific event, an anecdotal record is a written observation of what a child or group of children does within a designated time frame. The goal is to describe what is seen without making editorial comments or inserting opinions. Thus, an observer might write, "Tiffany sucks her thumb while dragging her 'blankie' to the doll bed. She lies on the floor next to the bed while staring quietly out the window." The observer would not, during this time, comment, "Tiffany is obviously very tired today." Comments such as these are written in later, when all evidence has been gathered and reflected on.

© Wealan Pollard/OJO Images/Getty Images

Writing a reflection and creating a checklist are examples of informal assessment, which is another way to assess a child's progress.

Checklists

Some checklists are available commercially. For example, readiness for preschool can be tested using checklists from Leap Frog at http://www.leapfrog.com. Included are social and motor skills, reasoning, language, math, science, and creative arts. Other checklists can be created as needs and interests arise; these will be tailored to a specific center or school, reflecting local culture and expectations. They might be extensive with sub-sections or contain just a few items as appropriate.

Checklists require the observer to either check or leave blank a behavior that is evident or a criterion that has been met. Behaviors for youngsters just learning to eat at the table with others might include using a spoon effectively, drinking from a cup with two hands and no adult help, and carrying dishes to the dirty dish tub. A criterion checklist might relate to academic milestones that children are expected to meet before advancing to the next grade. For example, many kindergartens require letter recognition, and a checklist could be used for each child with each letter listed and ready to check off. The use of a checklist for such a purpose indicates that it is criterion-referenced. That is, there are stated criteria or goals to be met, but children are not ranked across a standardized set of peers, as would be the case in a norm-referenced test.

ECE in Motion: Components of PerformanceAssessment

Performance assessment emphasizes observation of certain criteria instead of assessment of rigid standards.

Critical Thinking Questions

In what instances might performance assessment be impractical or inadequate for gauging a student's progress?

Why is it important to distinguish between performance criteria and knowledge norms?

Event Sampling

This observational method focuses on a single child and a single behavior that is cause for concern. Each time such an event takes place, the observer writes down what leads up to it, what takes place during it, and how it eventually ceases. Writing about what happens before and after, as well as during the event, helps the observer determine cause and effect. Perhaps a small boy has been biting others but the teachers have not been able to figure out what causes it. They begin to keep a record of each time it happens, noting the time of day and the events immediately before and after the biting behavior. Soon it becomes apparent that the child is most inclined to bite just before naptime and is calmed afterward, not by teachers talking to him about appropriate behavior, but by a teacher rubbing his back as he goes to sleep. Thus, once the event sampling is analyzed, teachers know to keep a close watch on the child before naptime, ready to redirect his behavior, and they know that a quiet backrub will no doubt be in order.

Portfolios

Portfolios are not in themselves assessment methods but instead are collections of artifacts. Portfolios contain children's work over time and can take the form of a manila folder, box, or other type of container. A portfolio box for younger children will probably contain art products or science projects that take up too much space for a folder. Children in the primary grades are more likely to have portfolios made up of written work. When teachers help children evaluate their products over time by giving them specific things to look for, children gain skills in self-assessment.

Rating Scales

A rating scale is essentially a checklist that has been modified to indicate levels of quality. Some are commercially available, especially those for teachers and administrators who wish to evaluate their care and learning sites. Perhaps the best known of these comes from the University of North Carolina. There are four versions available: the original Early Childhood Rating Scale (revised), Infant-Toddler, Family Childcare, and School-Age Care. These can be explored at ers.fpg.unc.edu. Another example of rating scales can be seen in the report cards in Case Studies 5.1–5.3. Whether letter grades or descriptive words such as "developing" and "proficient" are used, the degree of competence is stated.

Rubrics

Originally, a "rubric" was the ornate red heading to a new chapter in a medieval manuscript. Today, the word "rubric" tends to be used in a different sense, to mean a chart containing a list, long or short, of criteria to be met, along with a rating scale. The criteria are usually lined up along the left side of a page. Across the top of the same page, the associated ratings are listed. A kindergarten example might be a list of alphabet letters to be learned. The top of the page could be in three sections: Confident, In Progress, Introductory. Children can participate in self-assessment using a rubric, and these are usually simple and attractive, with clever illustrations. One might say, for example, "I can tie my shoes" and be illustrated with a picture of a shoe. Ratings at the top might be two faces, one with a smile and the other with a neutral expression indicating that the skill is still in progress.

Running Record

© Hemera/Thinkstock

When teachers observe a student learning a new skill such as addition, they often take a running record.

This technique is often used when children are learning to read, but it is adaptable to any number of situations. The teacher sits close to the child and makes notes pertaining to whatever is being observed. A running record form is typically in three columns: a left-hand column for date and time, a central column to record behavior, and a column on the right for comments. The form is most typically used with a single child for a finite period of time and to record a single activity, such as the reading of a story or playing during a recess. Skills and problems with the activity are usually the focus, and the observer typically writes down everything the child does, perhaps in abbreviated form.

Teacher and Child Self-assessments

In the case study Modeling Self-Assessment in the Preschool, we met Allison, who engaged in self-assessment and changed her behavior. Further, she was quite verbal about what she did at the snack table, and even the younger children began to assess their own behavior and, as needed, alter it. The same can be done with any area of the curriculum. When children are permitted to work with the teacher to choose exemplary products for their portfolios, they gain skills in self-assessment. One-on-one discussions between teacher and child about any work product can also enhance children's skills in this area.

Time Sampling

This form of observation is similar to event sampling, but it is confined to a specific period of time. As an example, there might be observations lasting one or two minutes, scheduled for every five or 10 minutes, for a total of a half hour. If done over a period of days or weeks, it would be possible to evaluate the improvement of behaviors, or lack thereof. Time sampling is one way of observing a child to see how often a behavior of concern appears.

Informal methods offer a variety of ways to assess progress and are known for the greater flexibility they provide as compared with formal methods. Because they are typically not standardized, however, there is always the danger of assessing in a biased way. Having more than one person, particularly an outsider, engage in the same method for a specific assessment is one way to deal with this potential problem. Without some training, teachers may find that the results of their assessment are inconclusive as well as biased. It is suggested that beginners turn to trained, experienced evaluators for assistance.

Chapter Summary

This chapter focused on the importance of assessment and evaluation, and it stressed the following points:

Assessment and evaluation for young children, just as for older students, changes over time depending on society's needs and demands.

One purpose of assessment is to plan and adapt curriculum to serve children's needs and interests more effectively.

Assessment is often used to improve teacher and program effectiveness, and may use children's progress as one measure of success.

A third purpose is to track children's progress, not only for teachers, but for their families as well. Report cards are one way this is accomplished.

A fourth purpose is to screen children for special needs. Federal legislation makes this not only ethically responsible, but also legally necessary.

Formal assessment uses standardized methods, thus providing fairness to the assessment process. Such methods, however, often cannot be relied upon to evaluate young children whose immaturity and constant change provide challenges.

Informal assessment is often referred to as alternative, or authentic, assessment. These methods provide flexibility and real-life application for formative assessment, but may not be as reliable as approaches that are more formal.

Reflections and Critical Thinking

In the case study Sample Kindergarten Report Card, a kindergarten child showed herself adept at math-related topics but challenged by some literacy areas, including the motor skills needed for writing. "Citizenship skills" and "work habits" remained a problem throughout the year. You possibly found Jenny to be immature. Did you think that holding her back a year would be a good idea? Her school believes that children should not be held to the results of readiness tests and that it is the school's responsibility to adapt to the child's needs. In the case of Jenny, this meant that the school had a special pull-out program that she could participate in each morning to improve her literacy skills. The parents' permission was required, however, and they refused, arguing that those hours were important for improving her citizenship skills as well; she needed to stay in her own class. Jenny is now in third grade. Her citizenship grades are middling, the child having developed perhaps too much skill at being the class clown. Her literacy skills are all at grade level, but she does not enjoy reading. Do you think the school was wrong not to hold Jenny back? Do you think her parents made a mistake by refusing the pull-out program? Why?

In the case study Sample First Grade Report Card, a first grader demonstrated very advanced reading skills in his first term, although he had not yet learned to spell or write on his own. An excellent all-around student academically, Ben, like Jenny, had difficulties with citizenship skills. What did you think the teacher in Ben's new school should know about him? As it turned out, the new school proved challenging both academically and socially for Ben. His family embarked on a yearlong experience in an Eastern European country. The mother had never spoken her native language with Ben, who now had to learn to speak Russian and read the Cyrillic alphabet. The first-grade teacher in the neighborhood elementary school was a warm and caring woman, but she had no training in teaching a foreign language child. Ben was put in the back of the classroom, where he could not even begin to track what was going on. Previously a good math student, Ben began to fail the subject because the teacher did not think to explain the addition and subtraction symbols. Some intervention from Ben's mother led to increased scores in both math and reading. Nevertheless, the principal suggested that Ben stay home during the school-wide final evaluations so he would not bring down their usually stellar scores.

Of course, this outcome is not one most, if any, readers would have guessed. It is shared here so that you can turn the story upside down. Suppose a first grader came to your class from a Russian-speaking, Cyrillic-writing country. What would you do that this teacher did? What would you avoid? What would you do to ensure the child's success? Are there resources you might have that the other teacher might not? The teacher did not speak the same language as the child; this might happen in your program. What can a teacher do in this situation?In the case study Sample Third Grade Report Card, the report card format changed dramatically to a model that is similar to what students can expect throughout all their formal years of schooling, although there are still some subjects that have evaluations that are less formal than a letter grade. You no doubt noted that Dee had trouble throughout the year following directions, but that she still had a positive attitude toward school. Did you guess what her problem might be? It was during this year that both school and parentsrealized that Dee should have specialized testing, and she was diagnosed as having attention deficit disorder (ADD). A therapist began to help Dee with coping skills, and she is now a successful fourth-grade student.

Regarding the lack of personalized comments from the teacher, this was not an issue with the parents, most likely because they engaged in much contact and communication with Dee's teacher.

Websites for Further Teaching Assistance

Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The CCSSO site contains useful information related to early education assessment and evaluation. Two documents on the site are especially helpful for understanding formal processes and definitions of terms. In the search box, type "ecea glossary."

http://www.ccsso.org

Joint Position Statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education (NAECS-SDE). These two important and influential organizations have laid out, in their position statement, a detailed description of what they argue are the ethical, appropriate, valid, and reliable approaches to assessing young children. Go to "Policies." There you will also find interesting links to other policy statements as well.

http://www.naecs-sde.org

Chapter 5 Flashcards

Key Terms

Click on each key term to see the definition.

alternative assessment

Assessment that uses methods that are meaningful to both children and teachers and that have application to the world outside school. Also known as authentic assessment.

common assessment

Assessment plans designed by two or more teachers of similar grades or levels, to be used with all their students.

criterion-referenced

Assessment that grades or ranks students on the basis of set goals or criteria.

formal assessment and evaluation

Standardized tests that permit the comparison of an individual's performance with a larger and similar group.

formative assessment

Ongoing or continual assessments that can be used to modify curriculum or methods as needed.

inclusion

Placing all children together in the center or classroom, including those with special cognitive, physical, or social/emotional needs.

No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB)

Official title: "An act to close the achievement gap with accountability, flexibility, and choice so that no child is left behind." A 2002 federal act providing standards-based educational requirements across all states.

norm-referenced test

Assessment that grades or ranks students in comparison with their peers.

Race to the Top—Early Learning Challenge (RTTT—ELC)

A competitive grant program provided to individual states to improve early childhood education, including assessment programs. First grants were awarded to nine states in late 2011.

standardized test

See formal assessment and evaluation.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales

Developed first in France, then updated at Stanford University in California, these tests assess an individual's intelligence quotient, or IQ.

summative evaluation

A final evaluation of a teaching-learning sequence, either short- or long-term.