250 words DQ

Option B: Obedience to Authority: Cause and Effect. First, read Stanley Milgram’s classic article on his infamous ‘shock’ experiments in the 1960’s. Follow this up by watching Obeying or Resisting Authority: A Psychological Retrospective, available via the Films on Demand section of the Ashford University Library. Read Chapter 7: Power and Politics. Then, address each of the following questions.

What specific factors would cause people to continue to shock other people, past the perceived thresholds of extreme pain, unconsciousness, or even death?

Provide three different explanations for this behavior, utilizing the three perspectives we have learned so far: the anthropological, political, and sociological perspectives.

In other words, to what specific causal factor would an anthropologist attribute this behavior? What about a political scientist? A sociologist?

Be sure to provide concrete examples from the text and from your own research. In crafting your response, you must make reference to at least two sources beyond the textbook or the assigned documentary

Below are links that will help compete assignment along with chapter 7

http://www.apa.org/research/action/order.aspx

https://simplypsychology.org/milgram.html

https://youtu.be/fxiWkTCjMmY

CHAPTER 7: Power and Politics

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students will be able to:

Describe the discipline of political science and explain what it is concerned with.

Define democracy.

Describe the kind of democracy that exists in the United States.

List the branches of the U.S. government.

Explain the source of each branch’s power and how that power is exercised.

Politics, Political Science, and Government Power

A distinguished American political scientist, Harold Lasswell, defined politics as “who gets what, when, and how.” “The study of politics,” he said, “is the study of influence and the influential. The influential are those who get the most of what there is to get. . . . Those who get the most are the elite; the rest are mass.”1 He went on to define political science as the study of “the shaping and sharing of power.” Admittedly, Lasswell’s definition of political science is very broad. Indeed, if we accept Lasswell’s definition of political science as the study of power, then political science includes cultural, economic, social, and personal power relationships—topics that we have already discussed in chapters on anthropology, economics, sociology, and psychology.

politics

the study of power

Although some political scientists have accepted Lasswell’s challenge to study power in all its forms in society, most limit the definition of political science to the study of government and how individuals influence government action. This chapter focuses primarily on the study of government and how individuals influence government action in the United States.

political science

the study of government and how individuals influence government action

What distinguishes government power from the power of other institutions, groups, and individuals? The power of government, unlike that of other institutions in society, is distinguished by (1) the legitimate use of physical force and (2) coverage of the whole society rather than only segments of it. By legitimate, we mean the right or power of the government to exercise authority. By physical force, we mean that the government can legitimately compel action, sometimes through law enforcement agencies and sometimes through the threat of punishment, including incarceration. Because government decisions extend to the whole of society and because only government can legitimately use physical force, government has the primary responsibility for maintaining order and for resolving differences that arise between segments of society. Thus, government must regulate conflict by establishing and enforcing general rules by which conflict is to be carried on in society, by arranging compromises and balancing interests, and by imposing settlements that the parties in the dispute must accept. In other words, government lays down the “rules of the game” in conflict and competition between individuals, organizations, and institutions within society.

government power

the legitimate use of force; coverage of the whole society

Democracy means individual participation in the decisions that affect one’s life, often through voting. Here Egyptian soldiers stand guard as voters leave a polling station in Cairo in 2011, the first Egyptian elections held after the popular uprising that ousted long-time dictator Hosni Mubarak from power.

The Meaning of Democracy

Ideally, democracy means individual participation in the decisions that affect one’s life. In traditional democratic theory, popular participation has been valued as an opportunity for individual self-development. Responsibility for governing one’s own conduct develops character, self-reliance, intelligence, and moral judgment—in short, dignity. Even if a benevolent king could govern in the public interest, the true democrat would reject him.2

democracy

individual participation in the decisions that affect one’s life

Procedurally, popular participation was to be achieved through majority rule and respect for the rights of those with a minority view. Self-development means self-government, and self-government can be accomplished only by encouraging each individual to contribute to the creation of public policy and by resolving conflicts over public policy through majority rule. Minorities who had had the opportunity to influence policy but whose views had not succeeded in winning majority support would accept the decisions of majorities. In return, majorities would permit minorities to attempt openly to win majority support for their views. Freedom of speech and press, freedom to dissent, and freedom to form opposition parties and organizations are essential to ensure meaningful individual participation.

John Locke and the Idea of Limited Government

Oftentimes, majority rule and respect for the rights of minorities occurs by limiting the power of the government through a social contract. Constitutionalism is the belief that government power should be limited. A fundamental ideal of constitutionalism—“a government of laws and not of men”—suggests that those who exercise government authority are restricted in their use of it by a higher law. A constitution governs government.

constitutionalism

the belief that government power should be limited

A famous exponent of the idea of constitutional government was the English political philosopher John Locke (1632–1704). Perhaps more than anyone else, Locke inspired the political thought of our nation’s founders in that critical period of American history in which the new nation won its independence and established its constitution. Locke’s ideas are written into both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

According to Locke, all people possess natural rights. These rights are not granted by government but derive from human nature itself. Governments cannot deprive people of their “unalienable rights to life, liberty, and property.” People are rational beings, capable of self-government and able to participate in political decision making. Locke believed that human beings formed a contract among themselves to establish a government in order to better protect their natural rights, maintain peace, and protect themselves from foreign invasion.

natural rights

rights are not granted by government but derive from human nature itself

Because government was instituted as a contract to secure the rights of citizens, government itself could not violate individual rights. If government did so, it would dissolve the contract establishing it. Revolution, then, was justified if government was not serving the purpose for which it had been set up. However, according to Locke, revolution was justified only after a long period of abuses by government, not over any minor mismanagement.

A social contract is the idea (not an actual written contract) that people consent to be governed and voluntarily give up some of their liberties so that the remainder of their liberties can be protected. For example, in the United States, people enjoy the right of freedom of speech, but this right is limited: One cannot exercise freedom of speech if it means joking to airport security personnel about bringing a bomb onboard an aircraft. But this rule protects people from the inconvenience of more delayed flights if security had to identify and search the bags of every prankster.

social contract

the idea that people consent to be governed and in doing so agree to give up some of their liberties so that the remainder of their liberties can be protected

The social contract that established government made for safe and peaceful living and for the secure enjoyment of one’s life, liberty, and property. Thus, the ultimate legitimacy of government derived from a contract among the people themselves and not from gods or kings. It was based on the consent of the governed. To safeguard their individual rights, the people agree to be governed.

Thomas Jefferson eloquently expressed Lockean ideals in the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Democratic Ideals of Liberty and Equality

The underlying value of democracy is individual dignity. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote that human beings, by virtue of their existence, are entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Government control over the individual should be kept to a minimum; this means the removal of as many external restrictions, controls, and regulations on the individual as possible without infringing on the freedom of other citizens.3

Another vital aspect of classic democracy is a belief in the equality of all people. The Declaration of Independence expresses the conviction that “all men are created equal.” The founders believed in equality before the law, notwithstanding the circumstances of the accused. Although the founders’ view of who was equal was limited—women and racial minorities were not afforded the same political rights as white males—the notion of equality informed early American political life. Eventually, the idea of equality has come to mean that a person is not to be judged by social position, sex, economic class, creed, or race. Many early democrats also believed in political equality, that is, equal opportunity to influence public policy.4 Political equality is expressed in the concept of “one person, one vote.”

Over time, the notion of equality has also come to include equality of opportunity in all aspects of American life—social, educational, and economic, as well as political—and to encompass employment, housing, recreation, and public accommodations. All people are to have equal opportunity to develop their individual capacities to their natural limits.

In summary, democratic thinking involves the following ideas:

Popular participation in the decisions that shape the lives of individuals in a society, including consent of the governed

Limited government formed by a social contract, which establishes the right of revolution if the government consistently tramples the rights of individuals

Government by majority rule, with recognition of the rights of minorities to try to become majorities; these rights include the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and petition, and the freedom to dissent, to form opposition parties, and to run for public office

A commitment to individual dignity and the preservation of the liberal values of liberty and property

A commitment to equal opportunity for all to develop their individual capacities

Power and the American Constitution

A constitution establishes government authority. It sets up government bodies (such as the House of Representatives, the Senate, the presidency, and the Supreme Court in the United States). It grants them powers, determines how their members are to be chosen, and prescribes the rules by which they make decisions. Constitutional decision making is deciding how to decide, that is, it is deciding on the rules for policy making. It is not policy making itself. Policies will be decided later, according to the rules set forth in the Constitution.5

constitution

the establishment of government authority; the creation of government bodies, granting their powers, determining how their members are selected, and prescribing the rules by which government decisions are to be made; considered basic or fundamental, a constitution cannot be changed by ordinary acts of government bodies

A constitution cannot be changed by the ordinary acts of government bodies; change can come only through a process of general popular consent. The U.S. Constitution, then, is superior to ordinary laws of Congress, orders of the president, decisions of the courts, acts of the state legislatures, and regulations of the bureaucracies. Indeed, the Constitution is “the supreme law of the land.”

Constitutionalism: Limiting Government Power

As we noted, constitutions govern government. To place individual freedoms beyond the reach of government and beyond the reach of majorities, a constitution must truly limit and control the exercise of authority by government. It does so by setting forth individual liberties that the government—even with majority support—cannot violate. In the United States, many of these individual liberties can be found in the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

The Bill of Rights

The U.S. Constitution contains many specific written restrictions on government power. The original text of the Constitution that emerged from the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 did not contain a Bill of Rights—a listing of individual freedoms and restrictions on government power. The nation’s founders originally argued that a specific listing of individual freedoms was unnecessary because the national government possessed only enumerated powers; the power to restrict free speech or press or religion was not an enumerated power, so the national government could not do these things. But Anti-Federalists (who did not favor ratifying the Constitution and argued for states’ rights) in the state ratifying conventions were suspicious of the power of the new national government.6 They were not satisfied with the mere inference that the national government could not interfere with personal liberty; they wanted specific written guarantees of fundamental freedoms. The Federalist supporters of the new Constitution agreed to add a Bill of Rights as the first ten amendments to the Constitution in order to win ratification in the state conventions. This is why our fundamental freedoms—speech, press, religion, assembly, petition, and due process of law—appear in the Constitution as amendments (Table 7-1).

Bill of Rights

the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution listing individual freedoms and restrictions on government power

Anti-Federalists

those who argued against ratification of the U.S. Constitution; they were wary of a strong national government and favored states’ rights

Federalists

advocates for ratification of the U.S. Constitution

TABLE 7-1: THE BILL OF RIGHTS

The Bill of Rights limits the power of government by proscribing what it cannot do, and it also specifies some individual rights citizens enjoy. In recommending the rights to be included in the Bill of Rights, James Madison chose from among more than two hundred suggestions.* That the rights he selected still have applicability today is a testament to his forethought and understanding of human nature and the nature of governments.

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

* Leonard W. Levy, Origins of the Bill of Rights (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999).

The Constitution Structures Government

The Constitution that emerged from the Philadelphia convention on September 17, 1787, founded a new government with a unique structure. That structure was designed to implement the founders’ belief that government rested on the consent of the people, that government power must be limited, and that the purpose of government was the protection of individual liberty and property. But the founders were political realists; they did not have any romantic notions about the wisdom and virtue of “the people.” James Madison wrote: “A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.”7 The key structural arrangements in the U.S. Constitution—national supremacy, federalism, republicanism, separation of powers, checks and balances, and judicial review—all reflect the founders’ desire to create a strong national government while ensuring that it would not become a threat to liberty or property.

National Supremacy

National supremacy simply means that when state and federal law conflict in an area in which both have jurisdiction, federal (national) laws are superior. The heart of the Constitution is the National Supremacy Clause of Article VI:

national supremacy

when state and federal law conflict in an area in which both have jurisdiction, federal (national) laws are superior

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

This sentence ensures that the Constitution itself is the supreme law of the land. Laws made by Congress must not conflict with the Constitution. The Constitution and the laws of Congress supersede state laws.

Federalism

The Constitution divides power between the nation and the states, creating a federalist system. Federalism recognizes that both the national government and the state governments have independent legal authority over their own citizens: Both can pass their own laws, levy their own taxes, and maintain their own courts.8 The states have an important role in the selection of national officeholders—in the apportionment of congressional seats and in the allocation of electoral votes for president. Most important, perhaps, both the Congress and three-quarters of the states must consent to changes in the Constitution itself.

federalism

the division of power between states and nations

Republicanism

To the founders, a republican government (republicanism, not to be confused with the name of the Republican political party) meant the delegation of powers by the people to a small number of representatives “whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice, will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations.” The founders believed that government rests ultimately on “the consent of the governed.” But their notion of republicanism envisioned decision making by representatives of the people, not the people themselves. The U.S. Constitution does not provide for direct democracy—voting by the people on national questions—that is, unlike many state constitutions today, it does not provide for national referenda (see Controversies in Social Science: “Direct Democracy versus Representative Democracy”). Moreover, in the original Constitution of 1787, only the House of Representatives are elected directly by voters in the states. Members of the Senate were elected by state legislatures; not until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913 would voters directly elect their U.S. senators. The president is elected by “electors” (chosen in a way prescribed by state legislatures) and the U.S. Supreme Court and other federal judges are appointed by the president with the consent of the Senate.

republican government (republicanism)

government by elected representatives of the people

direct democracy

people themselves vote directly on issues, rather than their representatives

These republican arrangements may appear undemocratic from our perspective today, but in 1787 this Constitution was more democratic than any other governing system in the world. Most other nations of that time were governed by monarchs, emperors, chieftains, and hereditary aristocracies. Later democratic impulses in America greatly altered the original Constitution and reshaped it into an even more democratic document. Specifically, the Constitution has reflected the increasing democratization of American society through the expansion of suffrage—the right to vote. Constitutionally, we see suffrage expanding to African Americans, women, and those 18 to 20 years old, mirroring the changes in society’s notions about who is qualified to elect the nation’s leaders.

The Separation of Powers

The separation of powers in the national government—separate legislative, executive, and judicial branches—was intended by the nation’s founders as an additional safeguard for liberty. Number 51 of The Federalist Papers, written to convince colonists of the merits of ratifying the Constitution, expresses the logic behind creating separate branches of government and giving them checks over each other:

separation of powers

the principle of dividing government powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. . . . It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.9

In practical terms, this has meant that the power to create, administer, and judge the laws has rested with the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, respectively.

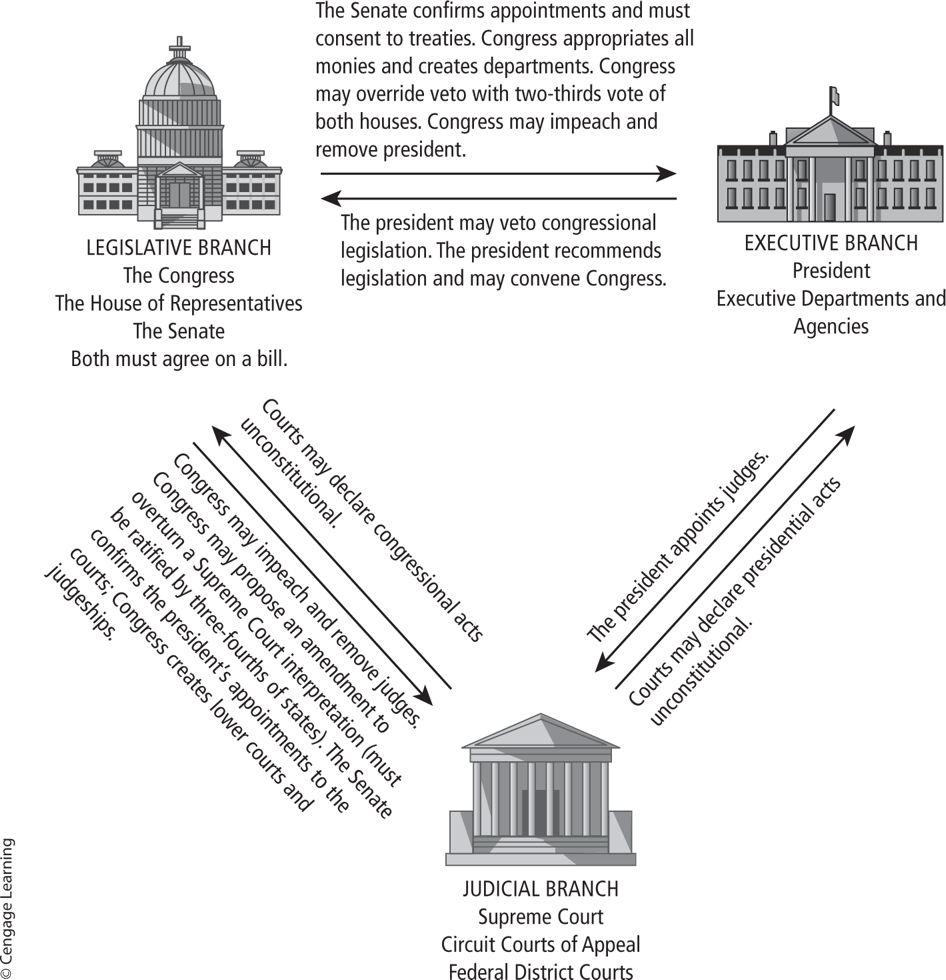

Checks and Balances

Each of the major decision-making bodies of American government possesses important checks and balances (Figure 7-1) over the decisions of the others. No bill can become law without the approval of both the House and the Senate. The president shares in legislative power through the veto and the responsibility of the office to “give to the Congress information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” The president also can convene sessions of Congress. But the president’s powers to make appointments and treaties are shared by the Senate. Congress also can override executive vetoes.

checks and balances

the principle whereby each branch of the government exercises a check on the actions of the others, preventing too great a concentration of power in any one person or group of persons

FIGURE 7-1: CHECKS AND BALANCES IN THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

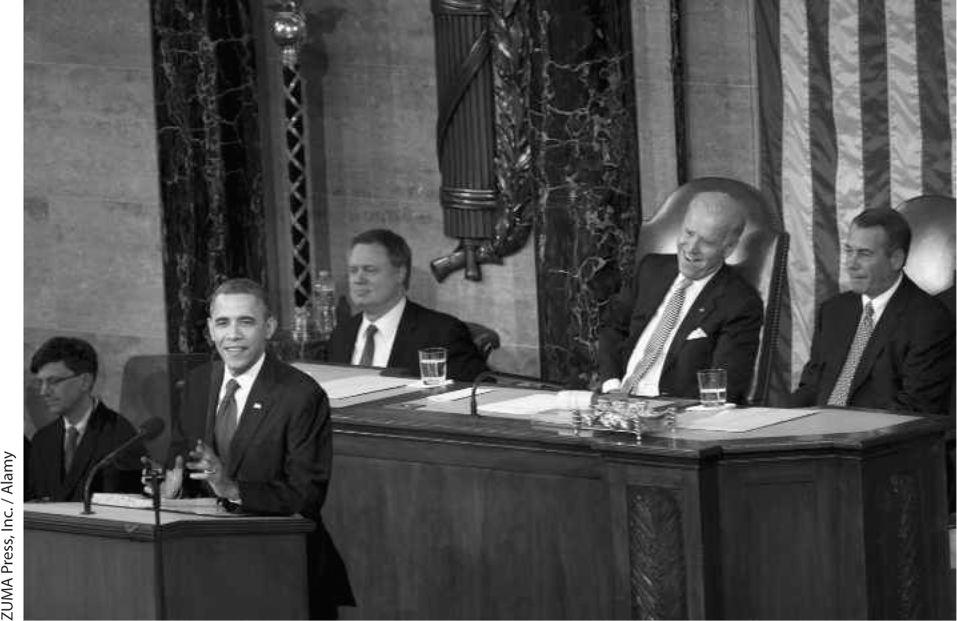

The president shares legislative power by setting the congressional agenda through his State of the Union address, shown here in 2012. Sitting behind President Obama are Vice President Joe Biden and House Speaker John Boehner (far right).

The president must execute the laws, but to do so he or she must rely on the executive departments, and they must be created by Congress. Moreover, the executive branch cannot spend money that has not been appropriated by Congress.

Federal judges, including members of the U.S. Supreme Court, must be appointed by the president, with the consent of the Senate. Congress must create lower and intermediate courts, establish the number of judges, fix the jurisdiction of lower federal courts, and make “exceptions” to the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

Perhaps the keystone of the system of checks and balances is the idea of judicial review, an original contribution by the nation’s founders to the science of government. Judicial review is the power of the courts to strike down laws that they believe conflict with the Constitution. Article VI grants federal courts the power of judicial review of state decisions, specifying that the Constitution and the laws and treaties of the national government are the supreme law of the land, superseding anything in any state laws or constitutions. However, nowhere does the Constitution specify that the U.S. Supreme Court has power of judicial review of executive action or of federal laws enacted by Congress. This principle was instead established in the case of Marbury v. Madison in 1803, when Chief Justice John Marshall argued convincingly that the founders had intended the Supreme Court to have the power of invalidating not only state laws and constitutions but also any laws of Congress or executive actions that came into conflict with the Constitution of the United States. Thus, the Court stands as the final defender of the constitutional principles against the encroachments of popularly elected legislatures and executives.

judicial review

the power of the courts to strike down laws they believe conflict with the Constitution

CONTROVERSIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCE: Direct Democracy versus Representative Democracy

CONTROVERSIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCE: Direct Democracy versus Representative Democracy

Democracy means popular participation in government. (The Greek roots of the word mean “rule by the many.”) But “popular participation” can have different meanings. To our nation’s founders, who were quite ambivalent about the wisdom of democracy, it meant that the voice of the people would be represented in government. Representational democracy means the selection of government officials by vote of the people in periodic elections open to competition in which candidates and voters can freely express themselves.

Direct democracy means that the people themselves can initiate and decide policy questions by popular vote. The founders were profoundly skeptical of this form of democracy. The U.S. Constitution has no provision for direct voting by the people on national policy questions. It was not until over one hundred years after the U.S. Constitution was written that widespread support developed in the American states for direct voter participation in policy making. Direct democracy developed in states and communities, and it is to be found today only in state and local government.

Initiative and Referendum

The initiative is a form of direct democracy whereby a specific number or percent of voters, through the use of petition, may have a proposed state constitutional amendment or state law placed on the ballot for adoption or rejection by the electorate of a state. This process bypasses the legislature and allows citizens to both propose and adopt laws and constitutional amendments.

The referendum is a device by which the electorate must approve citizen initiatives or decisions of the legislature before these become law or become part of the state constitution. Most states require a favorable referendum vote for a state constitutional amendment. Referenda on state laws may be submitted by the legislature (when legislators want to shift decision-making responsibility to the people), or referenda may be demanded by popular petition (when the people wish to change laws passed by the legislature).

Arguments for Direct Democracy

Proponents of direct democracy make several strong arguments on behalf of the initiative and referendum devices.

Direct democracy enhances government responsiveness and accountability. The threat of a successful initiative and referendum drive—indeed, sometimes the mere circulation of a petition—encourages officials to take the popular actions.

Direct democracy allows citizen groups to bring their concern directly to the public. For example, taxpayer groups have been able through the initiative and referendum devices to place their concerns on the public agenda.

Direct democracy stimulates debate about policy issues. In elections with important referendum issues on the ballot, campaigns tend to be more issue oriented.

Direct democracy stimulates voters’ interest and improves election-day turnout. Controversial issues on the ballot—the death penalty, abortion, gun control, taxes, gay rights, a ban on racial preferences, and so on—bring out additional voters.

Arguments for Representative Democracy

Opponents of direct democracy, from our nation’s founders to the present, argue that representative democracy offers far better protection for individual liberty and the rights of minorities than direct democracy. The founders constructed a system of checks and balances not so much to protect against the oppression of a ruler but to protect against the tyranny of the majority. Opponents of direct democracy echo many of the founders’ arguments:

Direct democracy encourages majorities to sacrifice the rights of individuals and minorities. This argument supposes that voters are generally less tolerant than elected officials.

Voters are not sufficiently informed to cast intelligent ballots on many issues. Many voters cast their vote in a referendum without ever having considered the issue before going into the polling booth.

A referendum does not allow consideration of alternative policies or modifications or amendments to the proposition set forth on the ballot. In contrast, legislators devote a great deal of attention to writing, rewriting, and amending bills and seeking out compromises among interests.

Direct democracy enables special interests to mount expensive initiative and referendum campaigns. Although proponents of direct democracy argue that these devices allow citizens to bypass legislatures dominated by special-interest groups, in fact, only a fairly well-financed group can mount a statewide campaign on behalf of a referendum issue.

SOURCE: See Thomas E. Cronin, Direct Democracy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989).

Federalism and the Growth of Power in the Federal Government

Since the founding of the United States, the power of the national government has increased significantly.10 Major developments in the history of American federalism have contributed to this increase in national power.

Expansion of Implied National Power

Chief Justice John Marshall added immeasurably to national power in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) when he broadly interpreted the “necessary and proper” clause of Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution, which states that the Congress has the power “to make all laws necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing powers, and all other Powers vested in this Constitution in the Government of the United States . . . .” Marshall asserted powers for the federal government that were not explicitly expressed in the Constitution. In approving the establishment of a national bank (a power not specifically delegated to the national government in the Constitution), Marshall wrote:

Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adopted to that end, which are not prohibited but consistent with the letter and the spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.11

Since then, the “necessary and proper” clause has been called the “implied powers” clause or even the “elastic” clause, suggesting that the national government can do anything not specifically prohibited by the Constitution. Given this tradition, the courts are unlikely to hold an act of Congress unconstitutional simply because no formal constitutional grant of power gives Congress the power to act.

The Civil War as a Victory for Federalism

Although we often view the Civil War as a war about slavery, the war also was the nation’s greatest crisis in federalism. A key question decided by the war was whether a state has the right to oppose federal action by force of arms. The same issue was at stake when, to enforce desegregation, the federal government sent troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957; to Oxford, Mississippi, in 1962; and to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in 1963. In these confrontations, it was clear that the federal government held the military advantage.

Growth of Interstate Commerce

The growth of national power under the interstate commerce clause is also an important development in American federalism. The Industrial Revolution created a national economy governable only by a national government. Yet, until the 1930s, the U.S. Supreme Court placed many obstacles in the way of government regulation of the economy. Finally, in National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation (1937), the Supreme Court recognized the principle that Congress could regulate production and distribution of goods and services for a national market under the interstate commerce clause. As a result, the national government gained control over wages, prices, production, marketing, labor relations, and all other important aspects of the national economy. Today, we can see government regulation of interstate commerce in our everyday lives, whether in the minimum wages paid by employers or the federal regulations on workplace conditions.

Federal Civil Rights Enforcement

Over the years, the U.S. Supreme Court has built a national system of civil rights based on the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified after the Civil War: “No State shall . . . deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” In early cases, the Supreme Court held that the general guarantee of liberty in the first phrase (the due process clause) prevents state and local governments from interfering with free speech, press, religion, and other personal liberties. Later, particularly after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954, the Court also used the equal protection clause to prohibit state and local government officials from denying equality of opportunity.

Federal Grants-in-Aid

The federal government also exerts power through the use of money. The income tax (established in 1913) gave the federal government the authority to raise large sums of money, which it spent for the “general welfare,” as well as for defense. Gradually, the federal government expanded its power in states and communities by use of grants-in-aid. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the national government used its taxing and spending powers in a number of areas formerly reserved to states and communities. Congress began grants-in-aid programs to states and communities for public assistance, unemployment compensation, employment services, child welfare, public housing, urban renewal, highway construction, and vocational education and rehabilitation.

grants-in-aid

payments of funds from the national government to state or local governments, usually with conditions attached to their uses

Today, federal grants-in-aid might pay for more police officers in your town, the creation of a bike path in your county, textbooks in your public schools, or highway improvement programs in your state. Table 7-2 shows the number of governments that exist in the United States. Nearly every government receives federal monies to provide services, though oftentimes these monies are channeled through the states to counties, municipalities, and school and special districts.

TABLE 7-2: THE NUMBER OF GOVERNMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES TODAY

Federal (national) government

1

State governments

50

County governments

3,043

Municipal and township governments

36,011

School districts

13,051

Special Services districts*

37,381

SOURCE: www.census.gov//govs/cog/GovOrgTab03ss.html.

* Includes governments that administer natural resources, fire protection services, or housing and community development.

Federalism Today

Today, federal grants-in-aid are the principal source of federal power over states and communities. Nearly one-quarter of all state and local government revenues are from federal grants. These grants almost always come with detailed conditions regarding how the money can be used. Categorical grants specify particular projects or particular individuals eligible to receive funds; block grants provide some discretion to state or local officials in using the money for a particular government function, such as law enforcement. Federal grant money is distributed in hundreds of separate programs, but welfare (including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF) and health (including Medicaid) account for nearly two-thirds of federal aid money.

Federal mandates, which are requirements issued by the national government that state and local governments must comply with, also centralize power in Washington. The federal government often passes laws requiring state and local governments to perform functions or undertake tasks that Congress deems in the public interest. Many of these federal mandates are “unfunded,” that is, Congress does not provide any money to carry out these mandated functions or tasks even though they impose costs on states and communities. For example, environmental protection laws passed by Congress require local governments to provide specified levels of sewage treatment, and the Americans with Disabilities Act requires state and local governments to build ramps and alter curbs in public streets and buildings.

federal mandate

a requirement issued by the national government with which state and local governments must comply

Devolution?

Over the years, various efforts have been made to return power to states and communities. President Ronald Reagan was partially successful in his “New Federalism” efforts; many categorical grant programs were consolidated into block grants with greater discretion given to state and local governments.

In recent decades, Congress has considered the devolution of some government responsibilities from the national government to the states and their local governments. So far, welfare cash assistance is the only major federal program to “devolve” back to the states. Since Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, with its federal guarantee of cash Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), low-income mothers and children had enjoyed a legal “entitlement” to welfare payments. Welfare reform in 1996, however, increased the power of state government by devolving responsibility for determining eligibility to the state. This is a major change in federal social welfare policy (see Chapter 11) and may become a model for future shedding of federal entitlement programs.

devolution

the transfer of federal programs to state and local governments

During the George W. Bush administration, some evidence indicates a trend away from devolution and toward increased federal involvement, particularly in education policy. The federal No Child Left Behind Act has created a vast array of federal mandates that local school districts must comply with to continue to receive federal funding. Some of these requirements, including mandatory yearly assessment testing of students, have been met with criticism by teachers and administrators. Nonetheless, the act represents a radical departure from the devolutionary trend of previous administrations.

Power and the Branches of the Federal Government

The changes in federalist relations and the increase in size of the national government have necessarily resulted in changes in the powers of the branches of the federal government—the Congress, the presidency, and the judiciary. When the founders drafted the Constitution, the powers of the Congress were quite strong, while their fear of a tyrannical king-type leader made them limit the powers of the presidency. The powers of the judiciary were barely defined. Over the years, the powers of all three branches of government have grown considerably, both because of circumstance and because of the authority exerted by individuals who have served in these branches.

Presidential Power

Americans look to their president for “greatness.” Great presidents are those associated with great events—George Washington with the founding of the nation, Abraham Lincoln with the preservation of the Union, Franklin D. Roosevelt with the nation’s emergence from economic depression and victory in World War II (see Focus: “Rating the Presidents”). People tend to believe that the president is responsible for “peace and prosperity” as well as “change.” They expect their president to present a “vision” of America’s future and to symbolize the nation.

Providing National Leadership

The president personifies American government for most people.12People expect the president to act decisively and effectively to deal with national problems. They expect the president to be compassionate—to show concern for problems confronting individual citizens. The president, while playing these roles, is the focus of public attention and is the nation’s leading celebrity. Presidents receive more media coverage than any other person in the nation, for everything from their policy statements to their favorite foods.

The nation looks to the president for leadership. The president has the capacity to mobilize public opinion, to communicate directly with the American people, to offer direction and reassurance, and to advance policy initiatives in both foreign and domestic affairs.

One source of presidential power is being viewed favorably by the American people. Presidential popularity is an important asset in giving presidents power and providing national leadership. Popular presidents cannot always transfer their popularity into power in the way of policy successes, but popular presidents usually have more success than unpopular presidents. Presidential popularity is regularly tracked in national opinion polls. Over the years, national surveys have asked the American public the following: “Do you approve or disapprove of the way the current president is handling his job?” (see Focus: “Explaining Presidential Approval Ratings”). Generally, presidents have been more successful in providing leadership in both foreign and domestic affairs when they have enjoyed high approval ratings.

Managing Crises

In time of crisis, the American people look to their president to take action, to provide reassurance, and to protect the nation and its people. For example, when the economic crisis hit in 2008, expectations were high for President Barack Obama, who had just been elected president. It is the president, not the Congress or the courts, who is expected to speak on behalf of the people in time of national triumph and tragedy. The president also gives expression to the nation’s sadness in tragedy and strives to help the nation go forward. For example, in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, then–President George W. Bush addressed the nation and also attended memorial services where he performed in a ceremonial capacity as the nation’s “chief mourner.” The president also gives expression to the nation’s pride in victory. The nation’s heroes are welcomed and its championship sports teams are feted in the White House Rose Garden.

Providing Policy Leadership

The president is expected to set policy priorities for the nation. Most policy initiatives originate in the White House and various departments and agencies of the executive branch and then are forwarded to Congress with the president’s approval. Presidential programs are submitted to Congress in the form of messages, including the president’s annual State of the Union Address to Congress and the Budget of the United States Government, which the president presents each year to Congress.

As a political leader, the president is expected to mobilize political support for policy proposals. It is not enough for the president to send policy proposals to Congress. The president must rally public opinion, lobby members of Congress, win legislative battles, and perhaps even fend off judicial challenges to policy proposals. Take, for example, President Obama’s reform of the nation’s health care system. In addition to fighting a scathing battle to get the measure passed in Congress, President Obama had to court the public on this matter and fend off legal challenges that questioned the constitutionality of the new law. To avoid being perceived as weak or ineffective, presidents must get their key legislative proposals through Congress. Presidents use the threat of a veto to prevent Congress from passing bills that they oppose; when forced to veto a bill, they fight to prevent an override of the veto. The president thus is responsible for “getting things done” in the policy arena.

Managing the Economy

The American people hold the president responsible for maintaining a healthy economy, or for fixing a damaged one. Presidents are blamed for economic downturns, whether or not government policies had anything to do with market conditions. The president is expected to “Do something!” in the face of high unemployment, declining personal income, high mortgage rates, rising inflation, or even a stock market crash. Herbert Hoover in 1932, Gerald Ford in 1976, Jimmy Carter in 1980, and George H. W. Bush in 1992—all incumbent presidents defeated for reelection during recessions—learned the hard way that the general public holds the president responsible for hard economic times. Presidents must have an economic strategy to stimulate the economy—tax incentives to spur investments, spending proposals to create jobs, and plans to lower interest rates. In today’s economy, they must also develop programs to improve America’s international competitiveness. Presidents also manage the economy through their appointment of the Federal Reserve Board, as is discussed in Chapter 8.

FOCUS: Rating the Presidents

From time to time, historians and political scientists have been asked to rate U.S. presidents. The ratings given the presidents have been remarkably consistent. Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Franklin Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson are universally recognized as the greatest American presidents. Ulysses S. Grant and Warren G. Harding both dominate on the bottom, or “failure” side, of most rating lists. It is more difficult for historians to rate recent presidents; the views of historians are influenced by current political controversies. Often the passage of time allows scholars to make more objective evaluations. Richard Nixon may be evaluated higher by future historians than he is today. How would you rate Bill Clinton? Barack Obama?

Schlesinger (1948)

Schlesinger (1962)

Dodder (1970)

Murray (1982)

Ridings & McIver (1996)

Great

1. Lincoln

2. Washington

3. F. Roosevelt

4. Wilson

5. Jefferson

6. Jackson

Near Great

7. T. Roosevelt

8. Cleveland

9. J. Adams

10. Polk

Average

11. J. Q. Adams

12. Monroe

13. Hayes

14. Madison

15. Van Buren

16. Taft

17. Arthur

18. McKinley

19. A. Johnson

20. Hoover

21. B. Harrison

Below Average

22. Tyler

23. Coolidge

24. Fillmore

25. Taylor

26. Buchanan

27. Pierce

Failure

28. Grant

29. Harding

Great

1. Lincoln

2. Washington

3. F. Roosevelt

4. Wilson

5. Jefferson

Near Great

6. Jackson

7. T. Roosevelt

8. Polk, Truman (tie)

9. J. Adams

10. Cleveland

Average

11. Madison

12. J. Q. Adams

13. Hayes

14. McKinley

15. Taft

16. Van Buren

17. Monroe

18. Hoover

19. Arthur, Eisenhower (tie)

20. B. Harrison

21. A. Johnson

22. B. Harrison

23. A. Johnson

Below Average

24. Taylor

25. Tyler

26. Fillmore

27. Coolidge

28. Pierce

29. Buchanan

Failure

30. Grant

31. Harding

Accomplishments of Administration

1. Lincoln

2. F. Roosevelt

3. Washington

4. Jefferson

5. T. Roosevelt

6. Truman

7. Wilson

8. Jackson

9. L. Johnson

10. Polk

11. J. Adams

12. Kennedy

13. Monroe

14. Cleveland

15. Madison

16. Taft

17. McKinley

18. J. Q. Adams

19. Hoover

20. Eisenhower

21. A. Johnson

22. Van Buren

23. Arthur

24. Hayes

25. Tyler

26. B. Harrison

27. Taylor

28. Buchanan

29. Fillmore

30. Coolidge

31. Pierce

32. Grant

33. Harding

Presidential Rank

1. Lincoln

2. F. Roosevelt

3. Washington

4. Jefferson

5. T. Roosevelt

6. Wilson

7. Jackson

8. Truman

9. J. Adams

10. L. Johnson

11. Eisenhower

12. Polk

13. Kennedy

14. Madison

15. Monroe

16. J. Q. Adams

17. Cleveland

18. McKinley

19. Taft

20. Van Buren

21. Hoover

22. Hayes

23. Arthur

24. Ford

25. Carter

26. B. Harrison

27. Taylor

28. Tyler

29. Fillmore

30. Coolidge

31. Pierce

32. A. Johnson

33. Buchanan

34. Nixon

35. Grant

36. Harding

Overall Ranking

1. Lincoln

2. F. Roosevelt

3. Washington

4. Jefferson

5. T. Roosevelt

6. Wilson

7. Truman

8. Jackson

9. Eisenhower

10. Madison

11. Polk

12. L. Johnson

13. Monroe

14. J. Adams

15. Kennedy

16. Cleveland

17. McKinley

18. J. Q. Adams

19. Carter

20. Taft

21. Van Buren

22. G. H. W. Bush

23. Clinton

24. Hoover

25. Hayes

26. Reagan

27. Ford

28. Arthur

29. Taylor

30. Garfield

31. B. Harrison

32. Nixon

33. Coolidge

34. Tyler

35. W. Harrison

36. Fillmore

37. Pierce

38. Grant

39. A. Johnson

40. Buchanan

41. Harding

Note: These ratings result from surveys of scholars ranging in numbers from 55 to 950.

SOURCES: Arthur Murphy, “Evaluating the Presidents of the United States,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 14 (1984): 117–126; William J. Ridings Jr., and Stuart B. McIver, Rating the Presidents (Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1997).

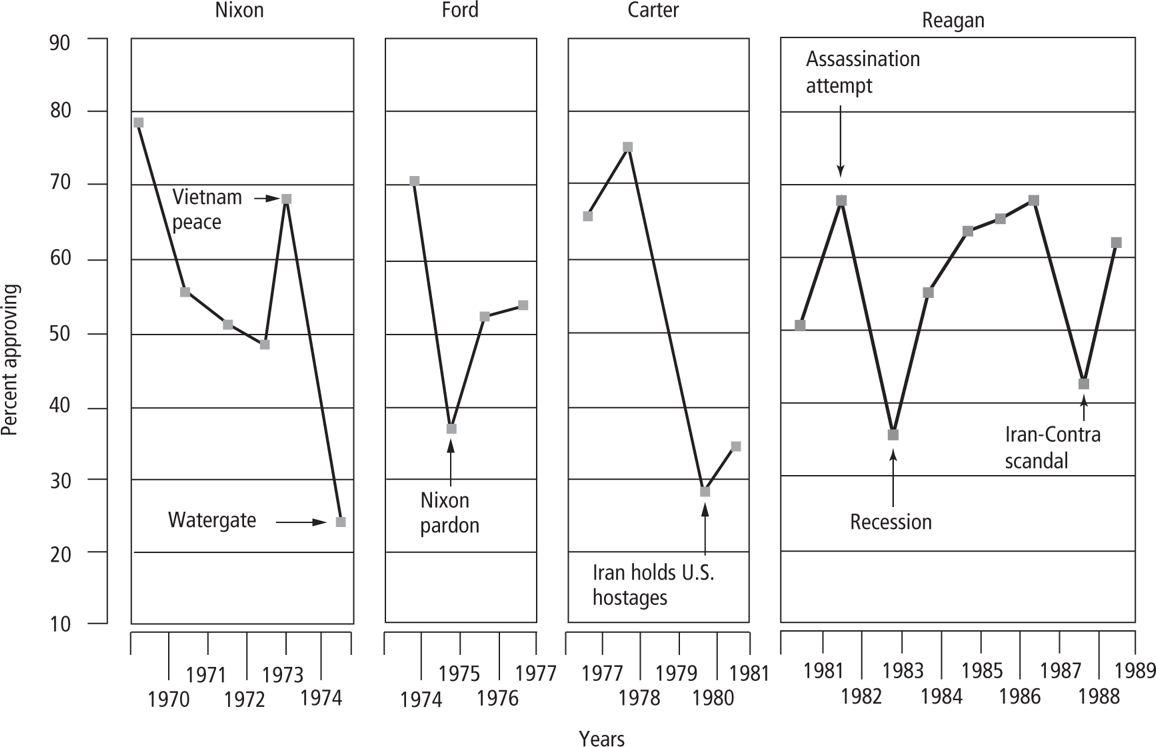

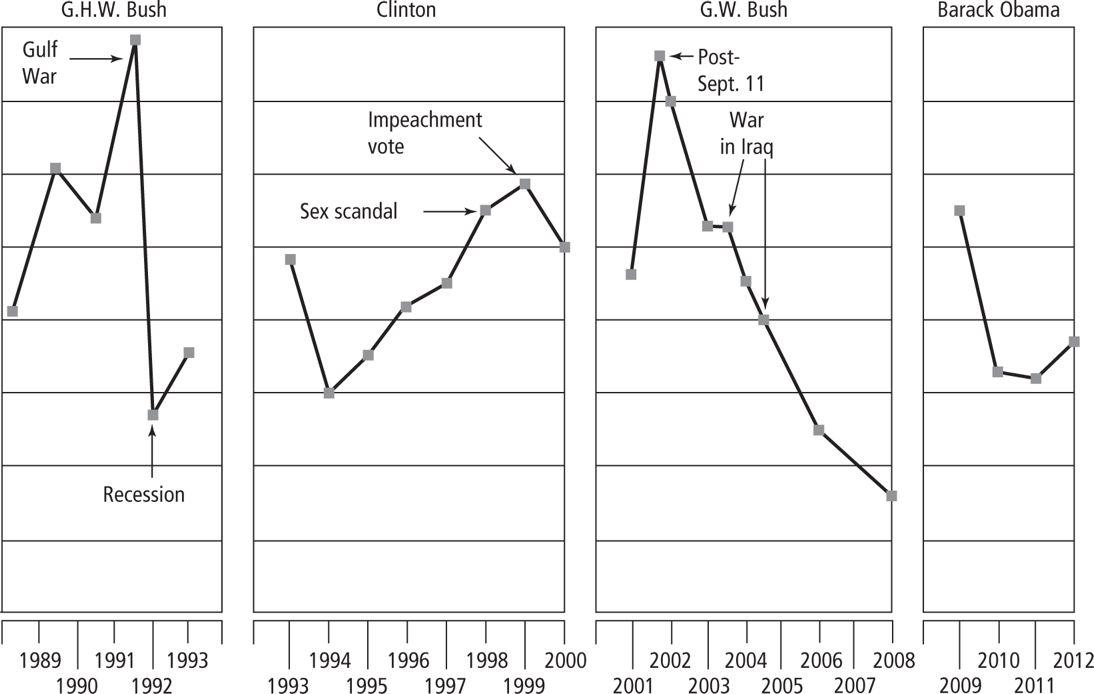

FOCUS: Explaining Presidential Approval Ratings

President-watching is a favorite pastime among political scientists. Regular surveys of the American people ask the question “Do you approve or disapprove of the way the current president is handling his job?” By asking this same question over time about presidents, political scientists can monitor the ups and downs of presidential popularity. Then they can attempt to explain presidential popularity by examining events that correspond to changes in presidential approval ratings.

One hypothesis that helps explain presidential approval ratings centers on the election cycle. The hypothesis is that presidential popularity is usually highest immediately after election or reelection, but it steadily erodes over time. Note that this hypothesis tends to be supported by the survey data in the accompanying figure. This simple graph shows, over time, the percentage of survey respondents who say they approve of the way the president is handling his job. Presidents usually begin their administrations with high approval ratings—Barack Obama started out his presidential term in 2009 with a 69 percent approval rating. Presidents and their advisors generally know about this “honeymoon”-period hypothesis and try to use it to their advantage by pushing hard for their policies in Congress early in the term.

Presidential Approval Ratings

Another hypothesis centers on the effects of international crises. Initially, people “rally ’round the flag” when the nation is confronted with an international threat and the president orders military action. President George H. W. Bush registered an all-time high in presidential approval ratings during the Persian Gulf War in 1991. But prolonged, indecisive warfare erodes popular support for a president. The public approved of President Johnson’s handling of his job when he first sent U.S. ground combat troops into Vietnam in 1965, but support for the president waned over time as military operations mounted.

Major scandals may hurt presidential popularity and effectiveness. The Watergate scandal produced a low of 22 percent approval for Nixon just prior to his resignation. Reagan’s generally high approval ratings were blemished by the Iran–Contra scandal in 1987. Yet Clinton’s ratings continued their upward trend despite a White House sex scandal and a vote for impeachment by a Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

Finally, it is widely hypothesized that economic recessions erode presidential popularity. Every president in office during a recession has suffered loss of popular approval, including Reagan during the 1982 recession. But no president suffered a more precipitous decline in approval ratings than George H. W. Bush, whose popularity plummeted from its Gulf War high of 89 percent to a low of 37 percent in only a year, largely as a result of recession. Barack Obama did rival Bush though, with a high honeymoon approval rating of 69 percent in 2009, followed by a low of 38 in August 2011, an evaluation many believed was a reflection of the poor economy.

SOURCE: www.gallup.com/poll/124922/presidential-approval-center.aspx

Presidents themselves are partly responsible for these public expectations. Incumbent presidents have been quick to take credit for economic growth, low inflation, low interest rates, and low unemployment. And presidential candidates in recessionary times invariably promise “to get the economy moving again.”

Managing the Government

As the chief executive of a mammoth federal bureaucracy with 2.8 million civilian employees, the president is responsible for implementing policy—that is, for achieving policy goals. Policy making does not end when a law is passed. Policy implementation involves issuing orders, creating organizations, recruiting and assigning personnel, disbursing funds, overseeing work, and evaluating results. It is true that the president cannot perform all these tasks personally. But the ultimate responsibility for implementation—in the words of the Constitution, “to take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”—rests with the president. Or as the sign on Harry Truman’s desk put it: “The Buck Stops Here.”

The Global President

Nations strive to speak with a single voice in international affairs; for the United States, the global voice is that of the president. As commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the United States, the president is a powerful voice in foreign affairs.14 Efforts by Congress to speak on behalf of the nation in foreign affairs and to limit the war-making power of the president have been generally unsuccessful. It is the president who orders American troops into combat. It is the president’s finger that rests on the nuclear trigger.

As the “leader of the free world” the president of the United States has the unique ability to make an imprint not only on the United States’ foreign policy, but also on the entire international political environment. For example, during the George W. Bush administration, U.S. foreign policy was shaped by the notion that a “clash of civilizations” characterized relations between the United States and many Muslim nations, while the Obama presidency stressed a more conciliatory relationship with these countries (see Chapter 14 for further discussion of U.S. foreign policy under these presidents).

Commander-in-Chief

Global power derives primarily from the president’s role as commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the United States. Presidential command over the armed forces is not merely symbolic; presidents may issue direct military orders to troops in the field. For example, President Barack Obama’s decision to increase troops in Afghanistan in a military surge strategy was a manifestation of his role of commander-in-chief. This role is one of the defining aspects of the presidency: As president, George Washington personally led troops to end the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794; Abraham Lincoln issued direct orders to his generals in the Civil War; Lyndon Johnson personally chose bombing targets in Vietnam; and George H. W. Bush personally ordered the Gulf War cease-fire after one hundred hours of ground fighting. As commander-in-chief, President George W. Bush issued a military order concerning the detention, treatment, and trial of noncitizen “combatants” believed to be involved in terrorism. All presidents, whether they are experienced in world affairs or not, soon learn after taking office that their influence throughout the world heavily depends on the command of capable military forces.

Modest Constitutional Powers

Popular expectations of presidential leadership far exceed the formal constitutional powers granted to the president. Compared with the Congress, the president has only modest constitutionally expressed powers (Table 7-3). Nevertheless, presidents over the years have consistently exceeded their specific grants of power in Article II, from Thomas Jefferson’s decision to double the land area of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase to William Jefferson Clinton’s decision to send U.S. troops to keep the peace in Bosnia and Kosovo.

TABLE 7-3: CONSTITUTIONAL POWERS OF THE PRESIDENT

Chief Administrator

Implement policy: “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” (Article II, Section 3)

Supervise executive branch of government

Appoint and remove executive officials (Article II, Section 2)

Prepare executive budget for submission to Congress (by law of Congress)

Chief Legislator

Initiate policy: “give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient” (Article II, Section 3)

Veto legislation passed by Congress, subject to override by a two-thirds vote in both houses

Convene special session of Congress “on extraordinary Occasions” (Article II, Section 3)

Chief Diplomat

Make treaties “with the Advice and Consent of the Senate” (Article II, Section 2)

Exercise the power of diplomatic recognition: “receive Ambassadors” (Article II, Section 3)

Make executive agreements (by custom and international law)

Commander-in-Chief

Command U.S. armed forces: “The president shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy” (Article II, Section 2)

Appoint military officers

Chief of State

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President” (Article II, Section 1)

Grant reprieves and pardons (Article II, Section 2)

Represent the nation as chief of state

Appoint federal court and Supreme Court judges (Article II, Section 2)

Limits on Presidential Power

Despite the great powers of the office, no president can monopolize policy making. The president functions within an established political system and can exercise power only within its framework.15 The president cannot act outside existing political consensus, outside the “rules of the game.” To ensure that the president does not overstep constitutionally-prescribed boundaries, both the Congress and the courts provide checks on the president, as described earlier in this chapter. So presidents may face a Congress that overrides a presidential veto, or fails to confirm judicial appointments; or a Court that declares a presidential action unconstitutional.

Electing the President

The 2008 presidential election proved to be historical, with Barack Obama succeeding in his quest to become the first African American elected president of the United States. Obama came to be the Democratic nominee for the presidency via another historic contest: He and Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton vied for their party’s nomination, each seeking to make history (she attempted to be the first woman major party nominee and U.S. president). Obama won the Democratic nomination with a well-organized and well-financed campaign that targeted young and first-time primary voters, and made savvy use of new technologies, including social networking sites like Facebook and MySpace.

These technologies would prove even more important in the 2012 contest between Obama and Republican Governor Mitt Romney. That year, we saw both campaigns rely on technology as tool of campaigning. The Republicans and Democrats each used the Internet and cellular technology to communicate with voters, mobilize supporters, organize their campaigns, and to raise money.

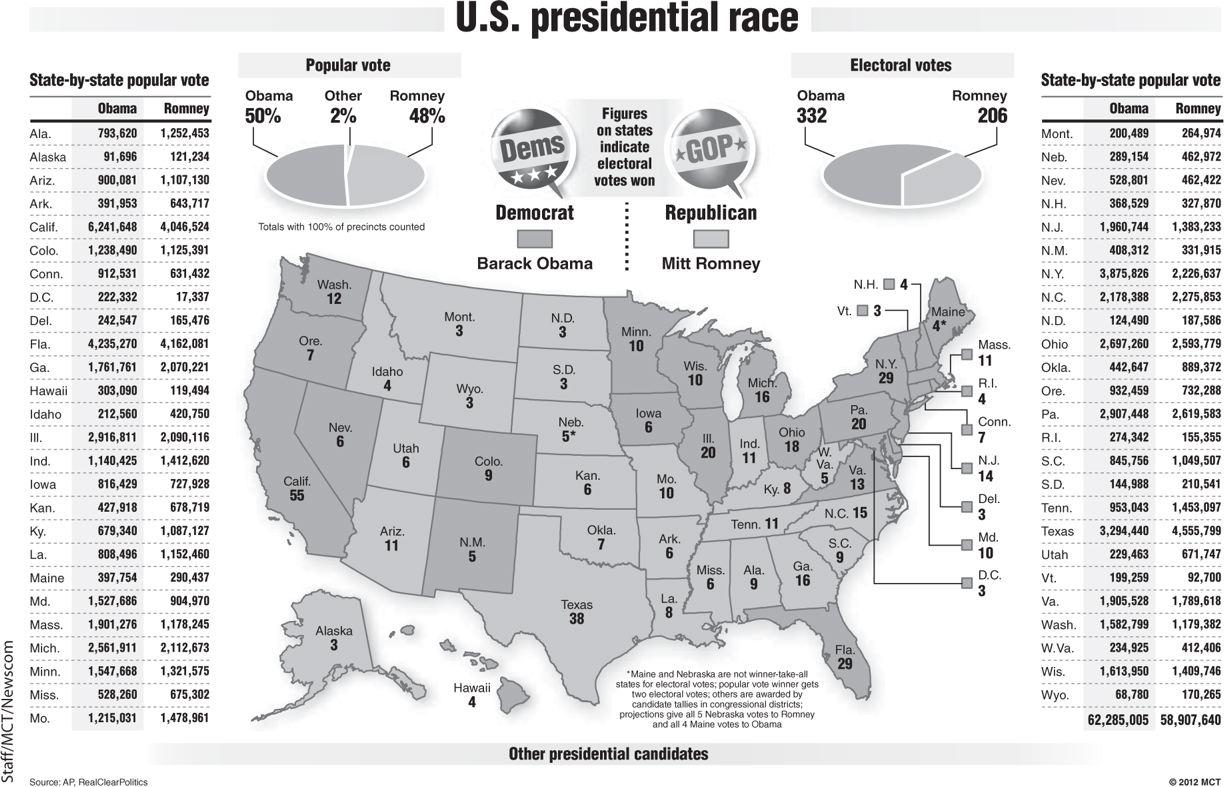

While the 2012 election was groundbreaking in terms of the campaigns’ use of technology, back in the year 2000 another dramatic election took place. That year, Americans were given a dramatic reminder that the president of the United States is not elected by nationwide popular vote but rather by a majority of votes in the Electoral College. In most states, electors are chosen in winner-take-all system, whereby the candidate who receives the most popular votes wins all of that states’ electoral votes. This system typically serves to exaggerate the popular margin of victory. But in 2000, Democrat Al Gore won 500,000 more votes nationwide (out of over 100 million cast) than his opponent Republican George W. Bush. But Bush won a majority of the states’ electoral votes—271 to 267—the narrowest margin in modern American history. And Florida’s crucial 25 electoral votes were decided by the U.S. Supreme Court more than a month after election day.

The Electoral College

The U.S. Constitution provides that the president will be chosen by the majority of the number of “electors” chosen by the states. Article II says “Each state shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress . . .” This means that each state gets a number of electors to the Electoral College equal to the size of their congressional delegation. Each state’s congressional delegation is composed of two U.S. senators and a number of members of the House of Representatives based on the state’s population. Although the number of each state’s electors is equal to the size of their congressional delegation, the members of Congress themselves are not the actual electors. The number of members of the House of Representatives is determined every ten years after the U.S. census is taken. Thus, the number of electoral votes of each state is subject to change after each ten-year census. The Twenty-Third Amendment granted three electoral votes to the District of Columbia even though it has no voting members in Congress. Winning the presidency requires winning enough states to garner at least 270 of the 538 total electoral votes.

The U.S. Constitution specifically gives state legislatures the power to determine how electors in their states are to be chosen. By 1840 the spirit of Jacksonian democracy (see Chapter 6) had inspired state legislatures to allow the voters of their states to choose slates of presidential electors pledged to vote for one or another party’s presidential and vice-presidential candidates. The slate that wins a plurality of the popular vote in a state (more than any other slate, but not necessarily a majority) casts all of the state’s votes in the Electoral College.

It is possible for a presidential candidate to win more popular votes nationwide and yet lose the election by failing to win a majority of the electoral votes. That is, a candidate could win by large margins of the popular vote in some states, yet lose by small margins in states with a majority of electoral votes, and thus lose the presidency despite having more popular votes nationwide.

Presidential candidates are well aware of the necessity to garner a majority of the electoral votes of the states. So in their campaigns they generally concentrate their efforts on the “swing” states—those that are judged to be close and that could swing either way—and give less attention to states that they feel are solidly in their column or hopelessly lost. Presidential candidates also focus on the larger states. Indeed, it is possible to win the presidency by winning the electoral vote in just eleven states. (As shown in Figure 7-2, the electoral votes of California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, and New Jersey total 270 electoral votes, just enough to win the presidency.)

FIGURE 7-2: THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE, 2012

The Historical Record

The Constitution specifies that if no candidate wins a majority of the electoral votes, the House of Representatives chooses the president, with each state delegation casting one vote. But the Constitution does not specify what happens if competing slates of electors are submitted by one or more states. This problem is left up to the full Congress to resolve.

Only two presidential elections have ever been decided formally by the House of Representatives. In 1800 Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in the Electoral College because the Twelfth Amendment had not yet been adopted to separate presidential from vice-presidential voting; all the Democratic–Republican electors voted for both Jefferson and Burr, creating a tie. In 1824 Andrew Jackson won the popular vote and more electoral votes than anyone else but failed to get a majority. The House chose John Quincy Adams over Jackson, causing a popular uproar and ensuring Jackson’s election in 1828. In addition, in 1876 the Congress was called on to decide which electoral results from the Southern states to validate; a Republican Congress chose to validate enough Republican electoral votes to allow Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to win, even though Democrat Samuel Tilden had won more popular votes. Hayes promised the Democratic southern states that in return for their acknowledgment of his presidential claim, he would end the military occupation of the South.

In 1888 the Electoral College vote failed to reflect the popular vote. Benjamin Harrison received 233 electoral votes to incumbent president Grover Cleveland’s 168, even though Cleveland won about 90,000 more popular votes than Harrison (with fewer states in the union, there were fewer members of the House of Representatives and electors in the Electoral College). Cleveland was elected for a second time in 1892, the only president to serve two nonconsecutive terms.

The 2000 Presidential Election

In 2000, the battleground states were Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and especially Florida. Bush’s younger brother, Jeb Bush, had been elected governor of Florida in 1998, and Republicans controlled both houses of the legislature. Early in the campaign, Bush had been so certain of winning Florida that he made very few appearances there. Only late in the campaign, when Gore was showing a lead in the Florida polls, did Bush mount a serious effort in that state.

Early in the evening on election night, the television networks “called” all of the battleground states for Gore, in effect declaring him the winner. But by 9 p.m. on the East Coast, Florida was yanked back into the undecided column; the Electoral College vote looked like it was splitting down the middle. Then around 1 a.m., Florida was “called” for Bush, and the networks pronounced him the next president of the United States. Gore telephoned Bush to concede, but after learning that the gap in Florida was closing fast, Gore called again and withdrew his concession. For the second time, the television networks pulled Florida back into the “Too Close to Call” column.

The Count Continues

The morning after election day, it was clear that Gore had won the nationwide popular vote. But the Electoral College outcome depended on Florida’s 25 electoral votes. Bush’s lead in Florida, after several machine recounts and the count of absentee ballots, was 930 votes out of 6 million cast in that state.

Armies of lawyers descended on Florida. The Gore campaign demanded hand recounts of the votes in the state’s three most populous and Democratic counties—Miami-Dade, Broward (Fort Lauderdale), and Palm Beach. Bush’s lawyers argued that the hand counts in these counties were late, unreliable, subjective, and open to partisan bias. Gore’s lawyers argued that the Palm Beach “butterfly” ballot was confusing (the Gore–Lieberman punch hole was positioned third instead of second under Bush/Cheney; Pat Buchanan’s punch hole was positioned second). They also argued that partially detached and indented “chads” (small perforated squares in the punch cards that should fall out when the voter punches the ballot) should be inspected to ascertain the “intent” of the voter.

A President Chosen by the Supreme Court

Gore formally protested the Florida vote, expecting that his protest would eventually be decided by the Florida Supreme Court, with its seven Democratic-appointed justices. And, indeed, by a four-to-three vote the Florida high court agreed. It ordered a hand recount of all “undervotes” in the state—ballots that failed to register a presidential selection on machines—to determine the “intent” of the voter.

However, Bush appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the Florida Supreme Court had overreached its authority under the U.S. Constitution when it substituted its own deadline for the deadline enacted by the state’s legislature. (Article II, Section 1, declares that “Each State shall appoint [presidential electors] in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct. . . .”) Bush’s lawyers also argued that without specific standards to determine the “intent” of the voter, different vote counters would use different standards (counting or not counting chads that were “dimpled,” “pregnant,” “indented,” and so on). Without uniform rules, such a recount would violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Bush v. Gore, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed (by a seven-to-two vote) that the Florida court had created “constitutional problems” involving the equal protection clause, and the Court ordered (by a five-to-four vote) that the hand count be ended altogether. The effect of the decision was to reinstate the Florida secretary of state’s certification of Bush as the winner of Florida’s 25 electoral votes and consequently the winner of the Electoral College vote for president by the narrowest of margins—271 to 267.

For the first time in the nation’s history, a presidential election was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Perhaps only the Supreme Court possesses sufficient legitimacy in the mind of the American public to bring about a resolution to the closest presidential electoral vote in history.

The Power of the Courts

The founders of the United States viewed the federal courts as the final bulwark against threats to individual liberty. Since Marbury v. Madison first asserted the U.S. Supreme Court’s power of judicial review over congressional acts, the federal courts have struck down more than eighty congressional laws and uncounted state laws that they believed conflicted with the Constitution.

Judicial review and the right to interpret the meaning and decide the application of the Constitution and laws of the United States are great sources of power for judges.16

Key Court Decisions

Some of the nation’s most important policy decisions have been made by courts rather than by executive or legislative bodies. The federal courts took the lead in eliminating racial segregation in public life, ensuring the separation of church and state, defining relationships between citizens and law enforcers, and guaranteeing voters equal voice in government. Today, the federal courts grapple with the most controversial issues facing the nation: abortion, affirmative action, the death penalty, religion in schools, the rights of criminal defendants, and so on. Courts are an integral component of America’s government system, for sooner or later most important policy questions are brought before them.17

Democracy and the U.S. Supreme Court

The undemocratic nature of judicial review has long been recognized in American politics. Nine Supreme Court justices—who are not elected to office, whose terms are for life, and who can be removed only for “high crimes and misdemeanors”—possess the power to void the acts of popularly elected presidents, Congresses, governors, and state legislators. Why should the views of an appointed court about the meaning of the Constitution prevail over the views of elected officials? Presidents and members of Congress are sworn to uphold the Constitution, and it can reasonably be assumed they do not pass laws that they believe to be unconstitutional. Why should the Supreme Court have judicial review of the decisions of these bodies?

The answer appears to be that the founders distrusted both popular majorities and elected officials who might be influenced by popular majorities. They believed that government should be limited so it could not attack principle and property, whether to do so was the will of the majority or not. So the courts were deliberately insulated against popular majorities; to ensure their independence, judges were not to be elected but appointed for life terms. Only in this way, the writers of the Constitution believed, would they be sufficiently protected from the masses to permit them to judge courageously and responsibly. Insulation is, in itself, another source of judicial power.

Judicial Restraint

The power of the courts, especially the U.S. Supreme Court, is limited only by the justices’ own judicial philosophy. The doctrine of judicial restraint argues that because justices are not popularly elected, the Supreme Court should defer to the decisions of Congress and the president unless their actions are in clear conflict with the plain meaning of the Constitution. Former Justice Felix Frankfurter once wrote, “The only check upon our own exercise of power is our own sense of self-restraint. For the removal of unwise laws from the statute books, appeal lies not with the Courts but to the ballot and to the processes of democratic government.”18 One should not confuse the wisdom of a law with its constitutionality; the courts should decide only the constitutionality of laws, not the wisdom or fairness.

judicial restraint

judges should defer to the decision of elected representatives unless it is in clear conflict with the plain meaning of the Constitution

A related limitation on judicial power is the principle of stare decisis, which means the issue has already been decided in earlier cases. Reliance on precedent is a fundamental notion in law; it gives stability to the law. If every decision ignored past precedents and created new law, no one would know what the law is from day to day.

stare decisis

reliance on precedent to give stability to the law