3D1-00-Discuss examples of how leaders interject themselves into the process of "organized anarchy": in ways that either bring order or expand the confusion..

Chapter Five Policy Entrepreneurship and the Common Good

The quintessential problem of politics [is] how to judge rightly the lesser evil, the relatively best, the ends that justify the means and the means themselves….

Mary Dietz

The common good … is good human life of the multitude, of a multitude of persons; it is their communion in good living.

Jacques Maritain

We now turn to policy entrepreneurship, or coordination of leadership tasks over the course of a policy change cycle. Leaders who are policy entrepreneurs—such as Marcus Conant, Stephan Schmidheiny, Gary Cunningham, Jan Hively, and many of their colleagues—are catalysts of systemic change (Roberts and King, 1996). Policy entrepreneurs “introduce, translate, and implement an innovative idea into public practice” (1996, p. 10). Like entrepreneurs in the business realm, they are inventive, energetic, and persistent in overcoming systemic barriers. They can work inside or outside government organizations; unlike Nancy Roberts and Paula King (1996), we do not reserve the term policy entrepreneur for nongovernmental leaders.

The essential requirements of policy entrepreneurship are a systemic understanding of policy change and a focus on enacting the common good. This chapter offers an overview of these two requirements; subsequent chapters are devoted to individual phases of the policy change cycle.

Before going further, we should note that public policy has both substantive and symbolic aspects. It can be defined as substantive decisions, commitments, and implementing actions by those who have governance responsibilities (including, but going beyond government), as interpreted by various stakeholders. Thus public policy is what the affected people think it is, and based on what the substantive content symbolizes to them. Public policies may be called policies, plans, programs, projects, decisions, actions, budgets, rules, or regulations. Moreover, they may emerge deliberately or as the result of mutual adjustment among partisans (Lindblom, 1959; Mintzberg and Waters, 1985). Exhibit 5.1 presents brief definitions of public policy and other key terms in this chapter.

Understanding Policy Change

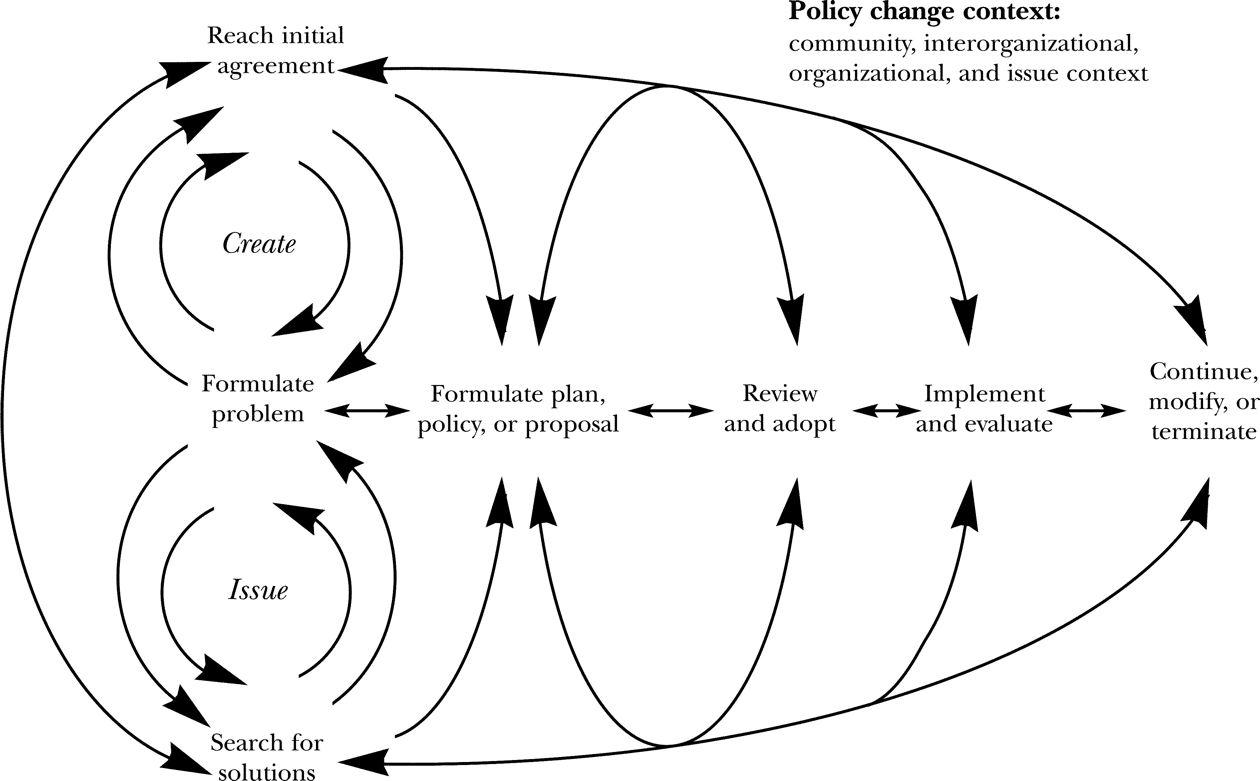

The policy change process can be described as a seven-phase cycle (Figure 5.1), in which a shifting set of change advocates work in multiple forums, arenas, and courts to remedy a public problem. The phases are interconnected and build on each other, but policy entrepreneurs are seldom able to march through them in an orderly, sequential fashion. In the case of a highly complex public problem such as AIDS or global warming, the cycle (and “re-cycling”) may extend over decades. The effort to enact solutions for less complex problems, such as homelessness in a particular city, may be successful in a much shorter period. No matter what, the same set of leaders and constituents who began a change effort may not be able to see the effort all the way through the cycle. Moreover, new leaders and constituencies are likely to join the process all along the way. Wise leaders attend to timing and are prepared to handle disruptions and delays throughout the process.

The policy change cycle is an orienting framework rather than a precise causal model (Sabatier, 1991). It contains a set of repeating and intersecting loops that highlight the frequency and pervasiveness of feedback throughout the cycle. The phases of the cycle and their central actions are on page 160.

Exhibit 5.1. Policy Entrepreneurship and the Common Good: Some Definitions.

Figure 5.1. Policy Change Cycle.

Source: Copyright © 2002 Reflective Leadership Center, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs and University of Minnesota Extension Service.

1. Initial agreement: Agree to do something about an undesirable condition, or “plan for planning”

2. Problem formulation: Fully define the problem; consider alternative problem frames

3. Search for solutions: Consider a broad range of solutions; develop consensus on preferred solutions

4. Policy or plan formulation: Incorporate preferred solutions into winning proposals for new policies, plans, programs, proposals, budgets, decisions, projects, rules, and so on; proposals must be technically and administratively feasible, politically acceptable, and morally and legally defensible

5. Proposal review and adoption: Bargain, negotiate, and compromise with decision makers; maintain supportive coalition

6. Implementation and evaluation: Incorporate formally adopted solutions throughout relevant systems, and assess effects

7. Continuation, modification, or termination: Review implemented policies to decide how to proceed

Designing and using forums (and visionary leadership) is most important in the first three phases, designing and using arenas (and political leadership) is most important in the middle, and designing and using courts (and ethical leadership) is most important toward the end of the cycle. Leadership in context and personal leadership are important at the outset; team and organizational leadership are vital throughout.

Policy entrepreneurs may become involved at any phase of a change cycle. Those dealing with emergent problems, such as the early AIDS crisis, must devote lots of attention to the first three phases, which constitute issue creation. If, as in the World Business Council case, leaders become involved after an issue is already well defined and new policies, programs, and projects are already being considered or implemented in arenas, they have to devote attention to the middle phases. They may also recycle through earlier phases to involve new constituents or develop alternatives to solutions that are under consideration.

If policy regimes are already fully implemented yet unable to remedy the problems they are supposed to address, leaders will focus on the last phase of the change cycle to determine whether the regime merits minor renovation, major overhaul, or destruction. For major overhaul or destruction, the change advocates may have to circle back to issue creation and involve new groups, redefine the problem, and search for new solutions. For example, when Hively and her colleagues became concerned about the lack of resources and support systems to help older adults lead productive lives, they were, in effect, pointing to the deficiencies of existing policy regimes (such as Medicaid and Medicare) that defined older adults as either frail dependents or self-centered retirees.

Before describing each phase, we want to examine policy making as a type of “organized anarchy” and emphasize the importance of managing ideas, analyzing and involving stakeholders, and designing institutions throughout the change cycle. Policy innovation simply won't happen without introducing compelling new ideas and additional players into the policy process. Nor is it likely to happen without altering or replacing existing institutional or shared-power arrangements.

Understanding the Policy Process as Organized Anarchy

The phrase organized anarchy has been used to describe the disorder, confusion, ambiguity, and randomness that accompany much decision making in large, “loosely coupled” organizations (Cohen, March, and Olsen, 1972). The term applies, perhaps with even more force, to the shared-power, interorganizational, interinstitutional policy environments where no one is in complete charge, and many are partly in charge.

Several scholars (see Cohen, March, and Olsen, 1972; Pfeffer, 1992; and Kingdon, 1995) emphasize the “anarchic” qualities of an organized anarchy:

• Goals and preferences are fairly consistent, at least for a time, within an individual, group, organization, or coalition. Goals and preferences are, however, inconsistent and pluralistic across individuals, groups, organizations, and coalitions.

• The position of an interest group and the composition of a coalition can change, sometimes quickly.

• Conflict is legitimate and expected as part of the free play of the political marketplace. Struggle, conflict, and winners and losers are normal.

• Information is used and withheld strategically.

• Within a social group, people hold consistent (often ideological) beliefs about the connection between actions and outcomes. Across groups, however, there may be considerable disagreement about the action-outcome relationship.

• The decision process often appears disorderly because of the clash of shifting coalitions and interest groups.

• Decisions result from the negotiation, bargaining, and interplay among coalitions and interest groups, indicating that these groups find it necessary to share power.

Despite this evidence of anarchy, there are points of stability and predictability in the policy process. Indeed, a shared-power arrangement is typically designed to furnish some of this stability. The basic organizing features of the policy process are the rules, resources, and transformation procedures that structure, enable, and legitimate specific actions. (These rules, resources, and procedures link action and underlying social structure in the “second dimension of power,” described in Resource D). Thus the shared-power world is not as anarchic as it may seem at first. It has many predictable features that policy entrepreneurs can use to achieve desirable change (Feldman, 2000). Moreover, the anarchic features open up innumerable opportunities to alter shared-power arrangements and create new ones (Huxham and Beech, 2003).

Policy analysts identify two types of policy change: “off-cycle,” or incremental change resulting from ongoing, routine, behind-the-scenes decision making in established policy regimes; and “on-cycle,” major change efforts that move onto the public agenda and force policy makers to thoroughly rethink and restructure existing policy regimes or develop new ones. Policy entrepreneurs attend most to on-cycle decision-making processes (represented by the policy change cycle), but they also need to understand off-cycle processes.

For example, in the African American Men case, policy entrepreneurs must understand the off-cycle decision-making process in education and criminal justice systems as they try to introduce mentoring programs for African American boys into the public schools, or to establish a process for expunging the records of ex-prisoners who have successfully completed probation and parole.

Managing Ideas

Practical people often underestimate the power of ideas, but as Guy Peters notes, “Shaping the nature of issues and policy problems is a basic aspect of the policy process, and the fundamental coordination issues arise from conflicts over ideas rather than from organizational interests” (1996b, p. 76). The idea or ideas promoted by policy entrepreneurs must compete with opposing ideas that are incorporated into existing policy regimes related to the problem at hand. These regimes are what Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones (1993) call policy subsystems, which operate behind the scenes, or off-cycle. Policy makers have already enacted major policies and established programs and regulatory mechanisms on the basis of a set of ideas about a public problem and optimal solutions. Participants in a shared-power arrangement are implementing those policies, programs, and regulations more or less in line with policy makers' intentions. Off-cycle policy and decision making are not part of the policy makers' agenda because day-to-day bureaucratic decision making—though it may have widespread indirect effects—does not directly affect most people, and therefore few take an interest in it. Moreover, policy subsystems have numerous built-in reinforcing and stabilizing mechanisms (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993). Change occurs, but it is incremental. Advocates of major change often must call established policy subsystems into question, because the systems are failing to deal with the problem at hand (even though they are expected to deal with this kind of problem), because the systems' efforts to remedy the problem are largely ineffectual, or because they are causing the problem.

Let's take a look at our four cases. Doctors and public health workers who became concerned in the early 1980s about the deaths of gay men from a mysterious disease were themselves already operating within a public health policy system, consisting of numerous interacting subsystems. In the system, local health departments administered vaccination programs, inspected restaurants, collected statistics about diseases, and the like. Nonprofit organizations pooled government and foundation funding to campaign against unhealthy lifestyles. The national government administered a host of research programs, operated hospitals and clinics, and investigated disease outbreaks. Nonprofit and for-profit hospitals and clinics treated patients and offered their own health education programs. Universities conducted medical research and operated teaching hospitals. Journalists specialized in health reportage; think tanks analyzed health policy.

Clearly, the system embraced a host of organizations (business, government, and nonprofit) and organized and unorganized constituencies (from newborns to cancer patients, from hospital associations to mental health support groups). It could accommodate problems that fit existing categories and required minimal reallocation of resources. Physicians, gay activists, and public health officials concerned about the emerging AIDS crisis realized after some initial effort that the new disease could not be dealt with through existing policy subsystems. These policy entrepreneurs began insisting that the local and national health policy makers put the new disease on their agenda and substantially redirect resources to investigate, treat, and prevent it.

The founders of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development were confronted with multiple policy systems and subsystems at the global, national, and industry levels. For example, the U.N. Development Programme and a multitude of nonprofits, national governments, and businesses were engaged in a development policy system that included subsystems focusing on specific aspects of development, such as farming. Other pertinent policy systems aimed at environmental protection or market regulation. None of these systems, however, were marshaling adequate business support for combining economic development and environmental protection.

The organizers of the African American Men Project (AAMP) had to deal with state and local policy systems related to education, criminal justice, housing, health care, and families. Within a given policy system, they called for changes in particular subsystems—such as physician education—that had an impact on the well-being of African American men. Jan Hively, Hal Freshley, and Darlene Schroeder created the Vital Aging Initiative to shake up the aging policy system of Minnesota and the United States. The system overlaps with health policy systems, education policy systems, and employment regulation systems; it embraces numerous policy subsystems, such as the Medicaid program.

To call policy subsystems into question, policy entrepreneurs present compelling ideas or explanations of the problem that concerns them. Marcus Conant, Michael Gottlieb, and Linda Laubenstein emphasized the idea that the disease affecting gay men was a medical problem, to be dealt with through the accepted protocols of epidemiology and infectious disease. Thus they redefined the mysterious as something familiar. They also defined a problem affecting a large number of gay men as a public responsibility. Change advocates also engage in other types of redefinition:

• Something previously thought of as good may be redefined as bad (for example, nuclear power is redefined as a threat to human health, or productive factories are redefined as contributors to global warming).

• Something previously thought of as bad is redefined as good (old age is redefined as productive maturity).

• The familiar is redefined as mysterious (the previous understanding of what causes a public problem is disproved, and the problem again becomes a mystery to be explored).

• Something thought of as a personal failure is redefined as a public, or communal responsibility (as with the switch from defining smoking as a personal choice to making it a public health issue).

If you are concerned about a public problem, you might use Exercise 5.1 to sort out your own ideas about the problem. What are the causes of the problem? What potential remedies should be considered, given the hypothesized causes? Which policy subsystems might be expected to deal with the problem? What redefinitions of the problem might be necessary to change existing subsystems or establish new ones? What opposing policy ideas am I likely to encounter? What is the “ideal” outcome of a change effort, and what does it imply about the problem? For example, does my desired outcome help me see that some other problem is more important?

In addition to problem definition, the policy change process may also be driven by “problem finding.” In other words, change advocates may be vested in a preferred solution and seek connections to problems that need solving. The solution may have resulted from a policy system that was designed to remedy some other problem that has now been resolved or diminished in importance. The advocates promote ideas that forge new connections between their preferred solution and one or more public problems.

Exercise 5.1. Thinking About a Public Problem.

Focus on a public problem that concerns you.

1. What are the causes of the problem?

2. What potential remedies should be considered, given the hypothesized causes?

3. What policy subsystems might be expected to deal with the problem?

4. What redefinitions of the problem might be necessary to change existing subsystems or establish new ones?

5. What opposing policy ideas am I likely to encounter?

6. What is the “ideal” outcome of a change effort, and what does that imply about the problem?

As you become involved in efforts to remedy the problem, you may wish to revise your answers from time to time.

Analyzing and Managing Stakeholders

Any ideas about how a problem should be understood and remedied must be developed and refined in concert with an array of stakeholders, since successful navigation of the policy change cycle requires the inspiration and mobilization of enough key stakeholders to adopt policy changes and protect them during implementation. Recall that a stakeholder is any person, group, or organization that is affected by a public problem, has partial responsibility to act on it, or has resources needed to resolve it. Key stakeholders are those most affected by the problem (regardless of their formal power) and those who control the most important resources needed to remedy the problem.

A stakeholder group consists of people who generally share an orientation to a problem and potential solutions. Specific individuals, however, may have weaker or stronger ties to the group. Indeed, individuals are likely to belong to more than one stakeholder group. Moreover, as philosopher Hannah Arendt has pointed out, it is important to remember that each citizen has a unique view of a public problem. She argues, “For though the common [i.e., public] world is the common meeting ground for all, those who are present have different locations in it, and the location of one can no more coincide with the location of another than the location of two objects…. Everybody sees and hears from a different position” (Arendt, 1958, p. 57).

Policy entrepreneurs need to keep this plurality of citizens in mind as they seek to draw individuals and groups into any new advocacy coalition that seeks to overcome the power of an existing coalition sustaining the current policy regime. Subsequent chapters suggest a variety of methods and tools appropriate to the various phases of the policy change cycle to analyze the interests, views, and power of stakeholders and involve them in the change process. Members of the mass media may be especially important since they have the capacity to magnify messages that policy entrepreneurs want to deliver.

Deciding who should be involved, how, and when in doing stakeholder analysis is a key strategic choice, one in which the devil and the angels are in the details. In general, particular people should be involved if they have information that cannot be gained otherwise, or if their participation is necessary to ensure successful implementation of initiatives built on the analysis (Thomas, 1993, 1995). In other words, involving people early on may be a key strategic step in building a supportive coalition needed later.

For entrepreneurs working inside government, stakeholder involvement may come under the heading of public participation. Entrepreneurs working outside government can also use an official public participation event such as a public hearing to promote their policy ideas.

Entrepreneurs must often strike a balance between too much and too little participation. The balance depends on the situation, and there are no hard and fast rules (let alone good empirical evidence) on when, where, how, and why to draw the line. Entrepreneurs should consider the important trade-offs between early and late participation and one or more of these desirable outcomes: representation, accountability, analysis quality, analysis credibility, analysis legitimacy, and the ability to act on the basis of the analysis. These trade-offs have to be thought through. The challenge may be, for example, “how to get everyone in on the act and still get some action” (Cleveland, 2002), or how to avoid cooptation (Selznick, 1949) to the point that the change advocates' mission is unduly compromised. Or the challenge may be how to have enough stakeholder representatives so that stakeholder interests and perspectives are not misunderstood (Taylor, 1998). Fortunately, the supposed choice actually can be approached as a sequence of choices, in which first an individual or small planning group begins the effort and then others are added later as the advisability of doing so becomes apparent (Finn, 1996; Bryson, 2004a).

Designing Institutions

A policy regime or subsystem is a set of institutions that we see as relatively stable patterns of formal and informal rules, regulations, customs, norms, sanctions, and expectations, governing—or setting strong incentives for—behavior. An institution is also a system of power relations and supporting communication patterns; it represents what E. E. Schattschneider (1975) calls a “mobilization of bias” that may or may not enhance the common good.

An institution is a powerful means of coordinating the actions of diverse individuals and groups. Policy entrepreneurs understand that they must design appropriate institutions if they are to ensure some permanency, or “institutionalization,” of desired changes. They often need to alter existing institutions and create new ones. Because of institutions' power and persistence, policy entrepreneurs have the responsibility to assess carefully whether an institution will be a vehicle for enacting the common good. Note that an institution may be formal or informal. Policy design typically is about formal institutions directly and informal institutions (such as the family) indirectly. Wise policy makers also know that formal institutions won't work without informal institutional supports (Ostrom, 1990; Scott, 1998).

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development, for example, emphasizes the importance of institutional design as it argues in favor of the Kyoto Protocol, or promotes the Global Compact (a U.N.-sponsored initiative in which participating corporations commit themselves to protect human rights and the environment), or helps establish certification programs for sustainable development practices. The council is also engaged in an effort to redesign markets generally, as through accounting and reporting methods that would assign costs to waste and pollution.

To take another example, the African American Men Project is itself a new institution with elaborate mechanisms for governance and oversight of initiatives. The project also aims to change major institutions, such as the public schools, city and county government, the court system, public libraries, radio and television programming, and the job market.

Exploring the Phases of the Change Cycle

Although ideas, stakeholders, and institutions are important throughout the policy change process, each phase offers particular challenges or opportunities for developing and refining policy ideas, analyzing and involving stakeholders, and altering institutions. Before describing each phase, we want to highlight the way the first three phases interact to produce public issues. The three phases together constitute issue creation, in which a public problem and at least one solution (with pros and cons from the standpoint of various stakeholders) gain a place on the public agenda. An issue is on the public agenda once it has become a subject of discussion among a broad cross-section of a community (of place or of interest). Typically, to gain a place on the agenda, policy entrepreneurs must help diverse stakeholder groups develop a new appreciation of the nature and importance of a problem and its potential solutions. Usually the three phases are highly interactive. Various agreements are struck, as problem formulations and solutions are tried out and assessed in an effort to push or block change. If policy entrepreneurs are unsuccessful in placing the issue on the public agenda, it remains a “nonissue” as far as the general community is concerned (Gaventa, 1980; Cobb and Ross, 1997).

Issues—linked problems and solutions—drive the political decision-making, or policy-making, process. Unfortunately, all too often in this process the real problems and the best solutions get lost (if ever they were “found”). Instead, a vaguely specified problem searches for possible policy options; policy advocates try to find a problem their solution might solve; and politicians seek both problems and solutions that might advance a career, further some group's goals, or be in the public interest. Hence visionary leadership becomes particularly important during the process of issue creation. A good idea can give the issue momentum; it is a compelling way of defining or framing the problem and attendant solutions so that key stakeholders are convinced the issue can and must be addressed by policy makers.

Initial Agreement

The purpose of the first phase of the policy change cycle is to develop an understanding among an initial group of key decision makers or opinion leaders about the need to respond to an undesirable condition and develop a basic response strategy. Policy entrepreneurs may initiate this phase with a simple conversation or small meeting with people they think may share their concern or have helpful insights. An example is the conversation between Mark Stenglein and Gary Cunningham that would ultimately lead to the AAMP. Before long, though, policy entrepreneurs must expand the circle to include at least some key stakeholders—those most affected by the problem and those with crucial resources for resolving the problem. (Guidelines for deciding whom to involve and how are offered in Chapter Six.) Policy entrepreneurs need visionary leadership skills as they organize forums (face-to-face and virtual) in which key stakeholders (many of whom represent a group of stakeholders) can develop at least a preliminary shared understanding of the problem and why doing something about it is important, and possibly urgent. The policy entrepreneurs must also convince stakeholders that their participation is vital and is likely to lead to personal and societal benefits.

Policy entrepreneurs have to practice leadership in context; that is, they must examine the policy environment in order to decide whether the time is right to try to launch a change effort. Timing may not be everything, but if it is off then a change effort may have difficulty gaining momentum beyond a small group of people. Thus policy entrepreneurs stay alert for subtle signals of change and any more visible “focusing event” (such as a disaster, official report of a new threat, a scientific breakthrough, a journalistic exposé)—evidence that existing policy regimes are being questioned. Focusing events are also likely to attract media attention to the problem and thus may help policy entrepreneurs involve additional stakeholders in the initial agreement. A focusing event can contribute to a window of policy-making opportunity, in which public concern about a problem comes together with promising solutions and political shifts to make policy change possible (Kingdon, 1995). (For further discussion of focusing events and related phenomena, see Baumgartner and Jones, 1993.) In the AIDS case, for example, as physicians and public health workers fought to get the epidemic that was affecting gay men on the public agenda in the early 1980s, they were attuned to scattered reports of a similar disease among drug addicts, Haitian immigrants, and hemophiliacs. These reports activated some additional stakeholders but did not attract the media attention that such subsequent focusing events as candlelight marches and the death of Rock Hudson would receive.

The desired outcome of this phase is one or more initial agreements that can guide a developing group of change advocates as they proceed through the policy change process. At the very least, the group should agree on the purpose and worth of the effort and outline a plan for planning. The agreement should be recorded in some way so that it can be a reference for future work. Subsequent agreements are likely to be struck later in the change process as more stakeholders become involved, and as an array of possible problem definitions and solutions becomes clear.

Problem Formulation

In this phase, policy entrepreneurs organize additional forums to deepen shared understanding of the problem that concerns them and to set direction for the next phases. They take a diagnostic stance, gathering information about how the problem manifests itself and about likely causes of or contributors to the problem. Information gathering can happen through stakeholder consultation (such as the stakeholder dialogues sponsored by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development), action research (such as that conducted for the African American Men Project and the Vital Aging Network), or professional conferences (such as gatherings of AIDS researchers).

Attention to framing is especially important in this phase. Policy entrepreneurs ensure there are opportunities for stakeholders to consider how they and others are framing the problem. They also help potential supporters of change understand the power of framing (the ability of a problem frame to exclude some solutions and privilege others). Thus Hively and her colleagues in the Vital Aging Initiative explicitly attacked the framing of older adults as frail dependents, which can only lead to a solution search that focuses on services and social welfare policy. Instead, they insisted on framing older adults as diverse, productive citizens. This view directed the search for a solution toward programs of empowerment and elimination of barriers to employment. Additionally, policy entrepreneurs emphasize the power of broader, more complex frames to “open up the search for solutions” (Nutt, 2002, p. 112) and attract a wider array of stakeholders. For example, the AAMP began with a narrow employment frame: the problem was that young African American men did not have jobs. Soon, however, county commissioners and staff began to focus more broadly. Once the project steering committee was established, the members understood that the “current social and economic situation of many young African American men does not stem from a single cause, but from a multitude of interrelated ones” (Hennepin County, 2002, p. 2). The committee then decided to focus on housing, family structure, health, education, economic status, community and civic involvement, and criminal justice.

Attention to frames can also constrain a group's habitual rush to a solution and help it think about the outcomes or objectives desired (Nutt, 2002; Nadler and Hibino, 1998). Chapter Seven includes exercises that can help a group identify its problem frames. Included is one adapted from Paul Nutt's work that helps individuals move from solution preferences to objectives.

Problem framing also relates to what Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones call policy image, which combines empirical information and emotional appeal (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993). For example, framing older adults as frail dependents is likely to prompt attention to statistics about disease and longevity or health care costs; it rouses emotions of compassion and responsibility on the positive side, but quite likely pity and resentment on the negative side. Thus policy entrepreneurs should think about not just the solutions themselves that flow from a problem frame but also the nonrational responses that may suffuse the ensuing debate about the solutions.

Policy entrepreneurs should also consider whether particular problem frames activate partisan agendas. In the United States, for example, using a government-failure frame (to explain something like the spread of the AIDS epidemic) activates long-standing disagreement between the Republican and Democratic parties about the amount and purpose of government expenditures.

Framing a problem as a crisis may also have unanticipated side effects. Stakeholders are certainly motivated to do something about the problem; reporters may begin covering it. At the same time, a crisis atmosphere can drive out thorough consideration of solutions. Journalists may even exacerbate the crisis as they seek out opposing views of what is causing the problem and thus promote controversy that sells newspapers or attracts viewers.

Search for Solutions

In this phase, policy entrepreneurs organize forums to consider solutions that might achieve the desired outcomes identified in the previous phase. In searching for solutions, forum participants can use three basic approaches: adapting solutions they know about, searching for solutions that exist but are not known to the group, and developing innovative solutions (Nutt, 2002). Organizers of the AAMP, for example, have developed a mentoring project called Brother Achievement (adapted from a program called Public Achievement) that coaches young people in citizenship.

Beyond identifying or developing solutions, the policy entrepreneurs also consider which solutions are likely to elicit interest and support from key stakeholders and the broader public. This analysis is helpful in placing the problem, and one or more promising solutions, on the public's agenda, thus creating a public issue that can attract the attention of policy makers and other affected parties who will then influence the formulation, adoption, and implementation of specific policies. It may also be possible to place an issue on the policy makers' agenda without gaining widespread public attention (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993). In the case of the AAMP, county commissioners were involved from the outset; thus the recommendations of the project steering committee were virtually ensured a place on the county board's agenda. Of course, many of the recommendations would require action by other policy makers, so supporters of the project planned a variety of forums that would attract additional stakeholders as well as media coverage that would influence decision making by state legislators, school board members, corporate boards, nonprofit leaders, and foundation grant makers.

At the conclusion of this phase, a strong advocacy coalition should be developing. Members of the group accept a shared problem frame and support a set of related solutions that require action by a range of policy makers. The coalition is likely to include a formal advocacy group and outside supporters—journalists, elected officials, public administrators, party officials—who are not members of the formal group. Our definition of an advocacy coalition is more inclusive than the one offered by Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, theirs being “an advocacy coalition consists of actors from a variety of public and private institutions at all levels of government who share a set of basic beliefs (policy goals plus causal and other perceptions) and who seek to manipulate the rules, budgets, and personnel of governmental institutions in order to achieve these goals over time” (1993, p. 5). We would include nonprofit and business organizations as well as governmental institutions as objects of the coalition's effort.

Even though the emphasis in this phase is on solutions, the forums that explore solutions are also likely to spend time reconsidering problem definitions. More specific guidance about solution search strategies and coalition development is offered in Chapter Eight.

Policy or Plan Formulation

In this phase, policy entrepreneurs shift their focus from forums to arenas. Working with their advocacy coalition, they develop plans, programs, budgets, projects, decisions, and rules for review and adoption by policy-making arenas in the next phase. They attempt to design and redesign institutions (and, if the desired change is sweeping enough, entire policy regimes). Policy design must address real problems in a way that is technically and administratively feasible, politically and economically acceptable, and legally and ethically responsible (Benveniste, 1989; Kingdon, 1995). Further guidance about designing policies or plans is offered in Chapter Nine.

When more than one arena might include the problem in its domain, policy entrepreneurs consider which arena is likely to look most favorably on their proposal—a process that Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones (1993) call “venue shopping.” Policy entrepreneurs often focus on arenas that are at multiple levels and in different realms. For example, the physicians fighting to stem the U.S. AIDS epidemic took their recommendations to local, state, and federal governments as well as to nonprofit and business arenas. Schmidheiny and his colleagues at WBCSD have focused on global and regional arenas as well. Attention to arenas may be phased, as when the initial focus in the AAMP was on the county board, which then funded further work that would include placing issues affecting African American men on other policy-making agendas. The Vital Aging Network focused initially on policy makers at the University of Minnesota and in state agencies or boards dealing with aging, but it soon sought grants from foundations and launched an educational program to help older adults press the state legislature for policy changes.

Bargaining and negotiation are common in this phase, but so is a collegial informality in which members of the advocacy coalition—elected officials, policy analysts, planners, and interest group advocates—try out alternative policies on one another, speak persuasively of the relative merits of their option, and engage in the give-and-take of a successful design session (Innes, 1996; N. C. Roberts, 1997). Policy entrepreneurs require political leadership skills, especially the skill of attending to the goals and concerns of all affected parties so as to build a coalition large and strong enough to secure adoption and implementation of a desired plan or proposal in subsequent phases.

The bargaining and negotiation, as well as the collegial give-and-take, of this phase are typically a somewhat behind-the-scenes preparation for the public battle to come in an arena. Policy entrepreneurs attempt to ensure that any proposal developed in this phase is of the kind that will survive the intense scrutiny and power plays expected in official policy-making meetings—especially those that attract television and other press coverage. If a proposal has not reached the point at which official decision makers can comfortably say yes to it under the glare of klieg lights and the scrutiny of journalists, it will be tabled for further work or buried indefinitely.

As an advocacy group converges around specific structural changes (ideas, rules, modes, media, and methods), policy entrepreneurs help the group think about how these new structures enable some behaviors and restrain others. They also help the group anticipate various stratagems that opponents may employ in the next phase, such as attacking or undermining the group; defusing, downgrading, blurring, or redefining the issue; controlling the policy makers' agenda; and strategic voting (Cobb and Elder, 1983; Riker, 1986).

Proposal Review and Adoption

In this phase, policy entrepreneurs call on their political leadership skills to persuade policy makers to adopt the policy or plan supported by their group. The first task is to place a proposed policy on the formal, or decision, agenda of the policy makers. The second is to engage in the bargaining, negotiation, and often compromise that characterize a policy-making arena without losing sight of policy objectives and alienating members of the advocacy coalition.

Crucial to policy adoption is what Guy Benveniste calls the “multiplier effect” (Benveniste, 1989, p. 27), which kicks in when stakeholders begin to perceive that a policy has a high probability of adoption. As this perception spreads, many stakeholders who were on the fence, or even against the proposed policy, join the supporting coalition. On the other hand, the same perception can cause opposition to harden if the opponents feel their fundamental beliefs or identity is threatened. A crisis may turn on the multiplier effect, changing perceptions about the costs and benefits of a proposed course of action. In the midst of crisis, advocates of change might be seen as system saviors, promising benefits to many, rather than as self-interested partisans whose proposed changes will benefit only themselves and place an undue burden on others (Wilson, 1967; Bryson, 1981).

Although implementation and evaluation are emphasized in the next phase, policy entrepreneurs should make sure that adopted policies are clear, workable, and politically acceptable to likely implementers. The new laws, regulations, or directives also should include an evaluation mechanism to help implementers ensure that problems are actually being remedied by the new policy, program, or project, and to help the implementers make needed adjustments in the initial implementation plan.

In the case of the AAMP, for example, the county commissioners were persuaded to approve the steering committee's recommendation for a permanent African American Men Commission that would include diverse stakeholders. The commission was to hammer out an action plan based on all the recommendations contained in the committee's report. It was also charged with coordinating, facilitating, and monitoring the implementation process and with publishing periodic reports on “outcomes for young African American Men in Hennepin County” (Hennepin County, 2002, p. 75). The county board also approved $500,000 in seed money to provide staffing and other support for the commission.

If change advocates fail to have their proposal adopted in this phase, they have the option of cycling back through previous phases to improve the proposal, find a more politically acceptable solution, reframe the problem, and build a stronger coalition of support. Additional guidance about proposal adoption and review is in Chapter Ten.

Implementation and Evaluation

In this phase, policy entrepreneurs attempt to ensure that adopted solutions are incorporated throughout a system, and their effects assessed. Successful implementation doesn't just happen. It requires careful planning and management; ongoing problem solving; and sufficient incentives and resources, including competent, committed people. The original leaders of the change effort may have to play new roles and allow new leaders to emerge.

The creation of the African American Men Commission attracted many additional supporters to the AAMP; in all, 130 people were appointed to the new group. The project staff organized twenty-six Saturday training sessions for all commissioners. Nine functional, or “domain,” committees plus an executive committee generate many leadership opportunities for the members. Additionally, county commissioners and Minneapolis city council members are ex-officio members of the executive committee.

The initial action plans developed by the commission established objectives for projects connected to each committee domain: fundraising, housing, family structure, health, education, economic status, community and civic involvement, criminal justice, and communications. The plans included numerous initiatives aimed at expanding the network of organizations working to improve the lives of African American men. Many were implemented almost immediately. For example, a major AAMP public conference, held just months after the county board approved the project's continuation, attracted 650 participants. Several organizations also agreed to join the project's Quality Partnerships Initiative, which brings together the AAMP, community nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and businesses to share information about their efforts to support African American men. By the time a year had elapsed from the appointment of the African American Men Commission, the AAMP was sponsoring a highly successful Day of Restoration, in which people who had piled up traffic violations could clear their records by paying fines or performing community service. The project also was preparing to launch Right Turn, which helps young men who have committed minor crimes create and implement an individual development plan.

Successful evaluation also does not just happen. Like implementation, it must be planned and supported if it is to inform judgment about program performance. Policy entrepreneurs need to keep in mind two contrasting purposes of evaluation. One is accountability to policy makers and other stakeholders, ensuring that a program or project is fulfilling policy makers' intentions and benefiting stakeholders. The second is improvement of a program or project as it is developing. Thus the Vital Aging Network's Advocacy Leadership Certificate Program includes assessment of participant learning and civic impact. Results are used to improve future renditions of the program and inform supporting organizations about the impact of their investment. Assessment of participant learning, with its focus on program improvement, is mainly what evaluation experts call “formative evaluation,” and assessment of civic impact, with its focus on program results, is mainly “summative evaluation” (Patton, 1997, p. 76).

Policy entrepreneurs should beware of making evaluation so cumbersome that it hinders program development. They also need to strike a balance in deciding on the timing of evaluations. On the one hand, they should ensure that a reasonable amount of time elapses, so that a new program or project has a chance to produce results. On the other hand, they need to be wary of allowing a new practice to become so entrenched that it can't be easily altered if evaluation shows it is misguided.

In this phase, policy entrepreneurs need political leadership skills as they attempt to influence administrative policy decisions and maintain or even expand the advocacy coalition. They also require ethical leadership skills, as they appeal to formal and informal courts that can enforce the ethical principles, laws, and norms undergirding the changes being implemented. They are likely to need visionary skills as they convene forums to understand implementation difficulties and develop new processes, mechanisms, or structures for resolving the difficulties. More guidance about implementation and evaluation is offered in Chapter Eleven.

Continuation, Modification, or Termination

Once a new policy has been substantially implemented, policy entrepreneurs review it to decide whether to continue, modify, or terminate the policy. They can take advantage of the routines of politics (upcoming elections, budgeting cycles, annual reporting) to organize forums in which the review occurs. Visionary leadership skills become especially important as these entrepreneurs focus on what is really going on: What constitutes evidence of success, or of failure? Has the original problem been substantially remedied? Has it worsened? Are the costs of the new policy regime acceptable when weighed against its benefits? If the answers indicate that the new regime is generally successful, policy entrepreneurs will seek to maintain or modify the enacted policy only slightly. They should marshal supportive evidence and maintain constituency support to ward off any effort to drain resources away from the new regime. If major modifications or an entirely new policy is warranted, a whole new pass through the policy change cycle is required. Policy entrepreneurs must rally their troops to reformulate the problem concerning them so they can consider new solutions to be placed on the public agenda. More guidance about this phase is in Chapter Twelve.

A Hierarchy of Process

In addition to the distinction between off-cycle and on-cycle policy making, another useful way of viewing the phases of the policy change cycle is to assign them to different levels of the “game of politics.” Each level typically involves its own participants, addressing certain kinds of challenges, with differing rhetoric, all of which together has a significant impact on the character of the action and outcomes of the game (Schattschneider, 1975, pp. 47–48; Kiser and Ostrom, 1982; Throgmorton, 1996; Flyvbjerg, 1998; Forester, 1999).

Lawrence Lynn (1987) describes three such levels of the public policy-making process: high, middle, and low. He argues that participants at each level must answer a different question. At the high level, the question is whether or not there is a public problem that requires action by policy makers, and if there is, what the purpose of that action should be. In terms of the policy change cycle, the high-level activity is principally one of issue creation. This activity, as we noted earlier, involves articulation and appreciation of emergent or developmental problems in terms of the values, norms, or goals used both to judge why the problem is a problem, and to seek optimal solutions.

In the middle level, the question is what strategies or policies should be pursued to achieve the agreed-upon purpose. The main challenges at this level are programming problems, as change advocates add detail to their preferred solutions. They have to specify policy mechanisms (taxes, subsidies, vouchers, mandated or voluntary agreements, deregulation or regulation, reliance on government service delivery or on contracts with business or nonprofit providers) and decide which government agencies, nonprofit organizations, or businesses will be responsible for applying and overseeing these mechanisms. They must also decide how statutory roles and financial, personnel, and other resources should be allocated among implementing agencies or organizations. In terms of the policy change cycle, middle-level action moves the process into the policy formulation and review and adoption phases.

At the low (or what we would call the operational) level, the questions revolve around the implementation details of plans, programs, budgets, rules, and projects. Exactly what management routine will be adopted? What schedule will be followed? What evaluation questions will be asked, and how will evaluation data be collected?

This analysis of the game of politics reinforces the importance of focusing on issue creation. It is here that stakeholders engage in passionate debate (and, ideally, considerable reflection) about values, civic responsibility, and justification for a policy decision. As Lynn notes, this debate “focuses on the right thing to do, on philosophies of government and the fundamental responsibilities of our institutions, on what kind of nation and society we should be, on social justice and our basic principles” (1987, p. 62).

Enacting the Common Good

So how do policy entrepreneurs discern and enact the common good in the policy change process, particularly if they are likely to personally identify with their causes, given the sense of importance and “rightness” they are sure to attach to the change effort? Not only that, as opposition intensifies they undoubtedly see the well-being of their own group as being synonymous with the common good and shut out any alternative version (Price, 2003; Gray, 2003). At worst, they may decide that their overwhelmingly virtuous ends justify immoral means (Price, 2003).

Before offering our own views of how policy entrepreneurs and their supporters can discern and enact the common good, we want to explore an array of conceptions of the common good, because it is a phrase that (like the word leadership) has a taken-for-granted quality that overlays vast differences of opinion about what it really means.

As we have considered how the common good appears in ordinary conversation, in philosophical treatises, and in political exhortations, we have noted that it may be applied at more than one level. Most often, it is connected to the condition of an entire community or society. Frequently, though, it has a much narrower application: to an organization or smaller group. Less often, the term is applied to a global region or the entire planet.

Our examination of philosophical and political pronouncements about the common good reveals that the term is actually part of a family of concepts. This “common good family” includes “the good society” (Galbraith, 1996; Bellah and others, 1991; Friedmann, 1979), “the commons” (Lohmann, 1992; Cleveland, 1990), “commonwealth” (Boyte, 1989), the “public interest” (Campbell and Marshall, 2002), and the “public good” (Campbell and Marshall, 2002). Other closely related concepts are community, the collective, and the just society. These concepts can be seen as distinct from, or in relation to, a contrasting set of concepts that include the individual, the personal, and the private.

The distinction between the two sets can be seen as central to an age-old debate about the relationship of the individual and society. The debate often stems from an understanding that what is best for a group of people or an entire society is in some way different from what might be best, or most advantageous, for a particular member of the group or society. Debate also arises from awareness that at least some people and groups will attempt to maximize their own interests at the expense of others.

Additionally, many philosophers argue that human beings can truly thrive only if they establish generally beneficial arrangements that provide services and goods that individuals are unable to obtain for themselves. These arrangements include governance mechanisms that balance individual and collective interests, sometimes by constraining and sometimes by liberating individual behavior. Debate then arises as to which governance mechanisms are best and how to provide collective goods and services. Traditionally, protection of the common good or public interest has been assigned to government. As Aristotle argued in his Politics, “True forms of government … are those in which the one, or the few, or the many, govern with a view towards the common interest; but governments which rule with a view to the private interest, whether of the one, the few, or the many, are perversions” (Aristotle, 1943, p. 139).

Guidelines for Thinking About the Common Good

Our examination of multiple views of the common good revealed four main themes that appear with a varying degree of emphasis in philosophical and political writings:

1. The relation between the individual and the community

2. The group whose common good is important

3. The content of the common good

4. The means of achieving the common good

From these themes, we have developed four guidelines for thinking about the common good:

1. Clarify your group's views of human nature and the relationship between the individual and society.

2. Decide whose common good is important.

3. Develop a general idea of what the common good might be.

4. Choose the means of achieving the common good.

Clarify Your Views on Human Nature and Society

Clearly, any conception of the common good rests on an understanding of the connection between the welfare of the individual and the society of which he or she is a part.

A minimalist stance is based on the recognition that individuals have differing goals and interests, and that some societal referee (government) is needed to deal with conflict among individuals. Government thus has the minimal (or negative) goal of preventing one person's actions from harming another. A more expansive stance is based on the recognition that society contributes to individual well-being above and beyond acting as a protector of individual freedom. Government has positive goals of supplying public goods, such as universal education, that help individuals thrive (see Berlin, 2002).

Thus one starting place for people trying to clarify their thinking about the common good is to explore how they see the relation of the individual and society, and perhaps how they view human nature. They might consider questions such as these:

• How does or should the community enhance individual development?

• Are people mainly self-interested, mainly concerned with and about others, or some mixture?

• Are people fundamentally equal?

• Is human life sacred? Less abstractly, are individual human beings sacred? Where is the line of sacredness drawn between individual human beings and human life generally?

Decide Whose Common Good Is Important

Major policy change efforts often arise from the perception that the common good of some large group, or of an entire society, is being undermined, or certainly not fulfilled. Policy entrepreneurs naturally focus on the well-being of the groups with whom they identify; it might be the advocacy coalition they've assembled, or some group within the coalition, or even some large category such as women or the poor. There are pragmatic as well as ethical reasons, however, to think more expansively. The pragmatic argument is that those whose interests are not considered in a change effort are quite unlikely to be committed members of an advocacy coalition and much more prone to join an opposing coalition. If they are not part of the coalition, they can be expected to resist the coalition's proposals. The ethical argument is that most ethical systems require adherents to consider the well-being of others. The life of every human being is deemed sacred by the majority of religions and by widely accepted treatises such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Ethically, policy entrepreneurs need to ask how any proposed changes affect everyone within the political unit in which they are operating. Even more expansively, they may have to consider how the change will affect those outside the unit (even all the other citizens of the world). Indeed, they might want to include future generations in their consideration. There are, of course, practical limitations on how many stakeholder groups can be thoroughly considered and involved in a policy change effort. The stakeholder analysis methods we offer help policy entrepreneurs and their supporters think about the interests of a diverse array of stakeholders, and certainly those most affected by a public problem and proposed changes.

Many of the policy entrepreneurs in the AIDS case cared most passionately about particular groups of people: gay men, children of drug users, hemophiliacs, Haitians. At the same time, many of them were deeply concerned about all the groups that were contracting AIDS and about the threat the disease posed to everyone in the United States. Some of these leaders would eventually become involved in efforts to fight AIDS in other societies around the world.

Leaders in the World Business Council for Sustainable Development have thought expansively from the beginning because of their concern for the well-being of future generations and poorer countries. However, they have also clearly focused their efforts on business stakeholders. In the African American Men Project, Mark Stenglein possibly cared most about the interests of the voters in his district, and Gary Cunningham had a lifelong commitment to the advancement of African Americans, but both also had to care about the well-being of all Hennepin County citizens. Jan Hively and her colleagues in the Vital Aging Network may be most concerned about the effects of ageism on older adults, but they also care about younger adults and children in Minnesota.

Develop a General Idea of What the Common Good Might Be

In the simplest terms, the common good might be viewed as the flip side of “the common bad”—the public problem that a group sets out to remedy. Since the problem affects a diverse group of stakeholders, the common good might be any new arrangement that substantially reduces the harmful effects on stakeholders. More extensive notions of the common good are grounded in an idea of what it takes for human beings to flourish (and such ideas are based in turn on a view of human nature). For Immanuel Kant, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Kenneth Galbraith, and other philosophers, the emphasis is on freedom and equality of opportunity. Galbraith, for example, argues, “The essence of the good society can be easily stated. It is that every member, regardless of gender, race, or ethnic origin, should have access to a rewarding life…. There must be economic opportunity for all” (1996, p. 23).

For some, the good for an entire group is equated with the interests of an elite few (a certain class, those who control the government). The notion is captured in phrases such as noblesse oblige, l'état c'est moi, father knows best. The utilitarians (notably Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill) are more egalitarian and offer a common sense formula—“the greatest good for the greatest number”—for deciding whether a policy is in the public interest or promotes the common good.

Others view the common good as connection to God or a communal tradition. For example, the Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain describes a host of “material and immaterial” endowments (from public roads to cultural treasures and spiritual riches) that are vital for a society to enjoy “communion in good living” (1947, p. 41). The communitarian philosophers of recent years would fit here.

The most egalitarian philosophers—Karl Marx comes readily to mind—equate the common good with a classless society. More recently, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania combined elimination of class distinctions with communal tradition into what he called “ujamaa socialism.” He sought to revive tribal traditions in which each person cared for the welfare of others in the tribe and in which each person could depend on the wealth of the community and enjoy a sense of security and hospitality (Duggan and Civille, 1976).

Another vision of the common good is the “caring community,” described by philosopher Nel Noddings and planning theorist Peter Marris (Noddings, 1984; Marris, 1996). In such a community, citizens give primacy to nurturing other human beings. In this work, they draw on the moral intuition and commitment that arise from parent-child relationships or from moral education. Reciprocity governs political life (Marris, 1996).

Given these diverse views, it's not surprising that the phrase the common good is so full of ambiguity and dispute. The loudest debate swirls around the pros and cons of utilitarian thinking and around issues of distributive justice. Critics of utilitarian thinking want to know what happens to those not included in “the greatest number.” They also want to know who decides what the greatest good is. Contemporary utilitarians offer a ready calculus known as “cost-benefit analysis”; once we determine the costs of a course of action and compare it to the worth of the outcomes, we can decide whether one course is better than some other. Cost-benefit analysis certainly is an extremely useful tool, but skeptics still question the wisdom and accuracy of even attempting to put a price on every aspect of life. Additionally, it is impossible to precisely predict costs and benefits of many proposed actions.

The most egalitarian visions of the common good require considerable redistribution of material and immaterial goods to those who are poor and disenfranchised. Obviously, those who are advantaged by existing distributions may think this is a bad idea; even if they favor a more egalitarian arrangement, they are rightly skeptical of massive government “social engineering” that is fraught with dangers to human freedom. Some philosophers—for example, Iris Marion Young—question the whole idea of a common good. They fear that any attempt to promote a common view of the common good will founder on the reality of power relationships, leading ultimately to the dominance of some elite's ideas (Young, 1990).

Our own general sense of the common good is captured by our definition of regimes of mutual gain: a set of principles, laws, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures that achieve lasting benefit at reasonable cost and that tap and serve the stakeholders' deepest interest in, and desire for, a better world for themselves and those they care about. This idea of mutual gain, as exemplified by the cases emphasized in this book, draws on several of these perspectives on the content of the common good. The African American Men Project has emphasized the quest for equal opportunity and for a community in which everyone cares about the well-being of everyone else. The Vital Aging Network too is fighting for equal opportunity, but in this case for older adults; Vital Aging leaders have also emphasized the societal benefits of enabling older adults to have a rewarding life. Leaders of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development talk about improving opportunities for small- and medium-sized business owners in “developing nations and nations in transition.” They emphasize that businesspeople have a responsibility for caring for the environment and the world's poor, and they argue that ultimately this approach benefits business as well.

Choose the Means of Achieving the Common Good

Perhaps views vary most about how to achieve the common good. Let's consider several methods that have been widely used around the world, often together in the same society; some of them are a ready match for the general ideas of the common good noted earlier.

• The authoritarian state, which enforces a particular group's view of the common good throughout society.

• The market, which allows people to obtain goods and services through buyer-seller exchange. A market transaction is, in effect, cost-benefit analysis in action; participants decide whether to engage in an exchange depending on the cost versus the benefit of the product or service involved. At the societal level, policy experts or government officials use a similar analysis to decide whether or not a program or project achieves the greatest good for the greatest number.

• Representative government, in which elected representatives hash out the common good. They are responsible for protecting minority interests and handling public needs (called commons problems) that are imperfectly handled by the market. Among the political philosophers who have elaborated this approach are Edmund Burke, John Stuart Mill, and James Madison.

• A religious regime that enacts and enforces policies aimed at enforcing what religious leaders deem to be God's will for human society. Examples are seventeenth-century Puritan societies in North America and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

• Expert judgment, in which professional policy analysts research societal issues and recommend best policies, on the basis of learning from the past and predicting the future.

• Informed public, or civic republic, in which citizens of a state debate, discuss, and persuade each other about the policies that government should pursue in dealing with public problems. This public deliberation also includes consideration of candidates for public office. Experts are involved, but their role is to furnish facts for the public to consider. The operations of government itself must be transparent so that citizens can evaluate their efficacy. This approach is associated with Thomas Jefferson and the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey.

• Active citizenry, or civic engagement, in which citizens themselves name public problems, make collective decisions about what should be done, and involve government officials and experts as needed. They carry out some decisions themselves, and they judge the results (Mathews, 1997). They perform what Harry Boyte and Nancy Kari (1996) call “public work.” They form a civil society, “where all versions of the good are worked out and tested” (Walzer, 1997, p. 15). Philosopher Hannah Arendt (1958) emphasized the simultaneous equality and diversity of the participants in this society; philosopher Cornel West echoes this perspective in his call for radical democracy (Lerner, 2002). Iris Marion Young argues that this public work does not require overall agreement on the nature of the common good. Her view supports the notion that citizens can find common ground by engaging in reflective conversation, or dialogue, in which they clarify meaning, describe social relationships, and defend their ideas and principles without pressing for joint endorsement of a theory of justice or the like (Young, 1990).

• Collaboration and organizing among the less powerful. Those who believe enactment of the common good requires direct confrontation of the mechanisms of power, class, and privilege advance this method. West (1994) also supports it. Danish political scientist Bent Flyvbjerg advises those who find themselves left out: “Then you team up with like-minded people and you fight for what you want, utilizing the means that work in your context to undermine those who try to limit participation” (1998, p. 236). These groups may have to work for transparency in a political system or promote civic virtues (such as engaging in respectful debate). Sometimes, counsels Flyvbjerg, direct power struggle works best, sometimes changing the ground rules, and sometimes writing studies that illuminate power relations (1998). Young is among those who argue that minority groups should have the ability to make their own policy decisions. A society might consist of loosely connected publics, and the common good would be determined by the people within them; to the extent there is an overarching common good, it should include some guarantee of self-determination for these groups. Marris, meanwhile, calls for nurturing social conditions that foster a politics of reciprocity. Moral education would help citizens draw on the morality of human nurture that is preached (and often practiced) in the family realm and apply it to public policies. He champions a “grown-up moral understanding” that fuses insight about nurturing and social control and justifies social control by the principles of nurturing relationships (1996, p. 170).

The last three approaches—informed public, active citizenry, and collaboration—are often directly opposed to the others (in the case of the authoritarian state and religious regime) or highly critical of the others (in the case of the market, representative government, and expert judgment).

The Leadership for the Common Good approach emphasizes comprehensive stakeholder analysis and involvement in order to develop shared understanding and enactment of the common good. It is a means of discerning and discovering, rather than pronouncing the common good. It has close affinity with the last three approaches: informed public, active citizenry, and collaboration. The policy entrepreneurs introduced in this book have emphasized these three approaches, but they have also used several of the others.

The U.S. physicians and health professionals concerned about the emerging AIDS crisis certainly applied expert judgment in their effort to understand and stop the disease, and they appealed to other experts to get involved. When they realized that public policies had to change, they put pressure on elected officials. When those avenues proved inadequate, they turned more avidly to collaborating with gay activists and trying to convey a sense of urgency to the general public.

Schmidheiny and his colleagues in the WBCSD have promoted active citizenry among businesspeople worldwide and also participated in (and often organized) forums involving numerous other citizen groups debating how best to deal with the problems of pollution and poverty. At the same time, these leaders have promoted a market approach and emphasized that governments of all stripes must become partners in sustainable development initiatives.

In launching the AAMP, Stenglein and Cunningham turned to elected officials (the county commissioners) to sponsor the project, but the project itself has engaged diverse groups of African Americans and other community leaders and experts in deciding what should be done and taking responsibility for advancing the project. The project recruited additional experts who could conduct needed research or facilitate group decision making. Several project initiatives also emphasize empowerment of young African American men, notably through training programs and job fairs that can help these men compete in the labor market.

Hively, Freshley, Schroeder, and their colleagues in the Vital Aging Network (VAN) have convened numerous forums, especially the Vital Aging Summits, to activate citizens—chiefly older people, but also people who work with them or are related to them—to work out the best means of enabling older adults to live a productive, satisfying life. The Advocacy Leadership Certificate Program in particular aims to empower older adults to be effective policy advocates. VAN also seeks to remove barriers to older adults' participation in the labor market.

Policy entrepreneurs in all these cases have attempted to foster an informed public that may join the advocacy coalition and help press policy makers to adopt proposals for change. To do this, they have employed plays, newspapers, television, the Internet, and other media.

Exercise 5.2 can help you and your colleagues think about the common good in relation to a public problem that concerns you. The exercise includes questions about whose common good is to be emphasized, the content of the common good, and the means of achieving it.

Exercise 5.2. Thinking About the Public Interest and the Common Good.

Justification of policy change efforts is usually connected to the common good (well defined or not). How, then, can policy entrepreneurs and other citizens judge whether a proposed change will serve the common good?

It may be helpful to see the common good as a family of concepts:

• Common good

• Good society

• Commons

• Commonwealth

• Public interest

• Public good

• Just society

• Community

This family of concepts contrasts with other concepts:

• Individual

• Personal

• Private

Debate over the common good is part of an age-old debate about the relationship between the individual and society. Some philosophers are skeptical about a common good. They advocate a focus on:

• Loosely connected publics determining their own interest

• Protections that counter majoritarianism: the common good might then be protection of the ability of minority groups, in particular, to make their own policy decisions

Exercise

As your group focuses on a public problem that concerns you, you may want to develop tentative answers to these questions.

1. How do you see connections between the individual and society, the citizen and government:

• What do you think an individual needs from society to flourish?

• What is the role of government in protecting individual interests and common interests?

2. Whose common good will you emphasize:

• The inhabitants of a geographic territory?

• Citizens or residents of a state, nation, or other government?

• Members of a group or organization?

• Future generations?

3. Develop a general idea of what a regime of mutual gain might look like in this case:

• What widespread, substantial benefit do you hope to achieve that could be accomplished at reasonable cost?

• What might be the elements of a desirable regime (ideas, rules and norms, formal relationships, informal relationships, rights, responsibilities, etc.)?

4. What combination of methods will you use to achieve the common good?

• Markets

• State control

• Informed public

• Active citizenry

• Expert judgment

• Religious directives

• Other (please specify)

The group can record its answers to the questions and refer to them as it proceeds with the policy change effort. The answers may be revised as the group expands and develops a deeper appreciation of the problem and promising solutions.

Summary

This chapter has given an overview of the policy change cycle and explored several approaches to enacting the common good. The policy change cycle has been described as organized anarchy that includes many predictable features as well as constant flux. To be effective navigators of the change cycle, policy entrepreneurs must manage ideas, analyze and involve stakeholders, and wisely design institutions. To discern and foster the common good, policy entrepreneurs can help constituents think about the relationship between individuals and their communities, the groups whose well-being is most crucial, the content of the common good, and means of achieving it.

This chapter has introduced the seven phases of the policy change cycle. The remainder of this book amounts to a handbook for policy entrepreneurs seeking to operate wisely in each phase. Particular attention is given to stakeholder analysis and involvement.

(Crosby 156)