MGT426 Questions

18 Transformational Change

Learning objectives

Describe the characteristics of transformational change.

Explain the organization design intervention for both domestic and worldwide situations.

Learn about the integrated strategic change intervention and understand how it represents the revolutionary and systemic characteristics of transformational change.

Discuss the process and key success factors associated with culture change.

This is the first of three chapters describing strategic change interventions. In prior chapters of this text, organizational development processes aimed at improving specific parts of an organization were described. For example, third-party interventions addressed conflict between two individuals, team-building interventions improved group functioning, employee involvement interventions increased member engagement, and reward system interventions aligned individual and team incentives with business strategy. In every case, the intervention focused on one particular organizational subsystem and placed other subsystems in the background. That is, diagnostic data pointed to one specific aspect of the organization, such as a structure, system, or process, as needing development. More importantly, there was an implicit or explicit assumption that the organization's culture was part of that background and that the interventions were unlikely to influence the culture in any significant way.

The focus of the interventions in Part 6 is on the whole system—on organization development. These change programs are “strategic” in that they are intended to alter the relationship between an organization and its environment, and they are intended to affect outcomes at the organization level, including sales, profitability, and culture. These interventions involve changing the strategy and/or design of a single organization or combining or orchestrating the activities of multiple organizations.

This chapter describes transformational interventions. These change processes bring about important alignments between the organization and its competitive environment and among the organization's strategy, design elements, and culture. They are initiated in response to or in anticipation of major changes in the organization's environment or technology. As a result, these changes often trigger significant revisions in business strategy, which, in turn, may require modifying internal structures and processes to support the new direction. Such fundamental change entails a new paradigm for organizing and managing the organization; it requires qualitatively different ways of perceiving, thinking, and behaving. Movement toward this new way of operating requires senior executives to take an active leadership role. The change process is characterized by considerable innovation as members discover new ways of improving the organization and adapting it to changing conditions.

Transformational change is an emerging part of organization development, and there is some confusion about its meaning and definition. This chapter starts with a description of several major features of transformational change. For example, transformational change is triggered by internal or external disruptions; initiated by line managers and executives; influenced by multiple stakeholders, systemic and revolutionary; and characterized by significant learning and a new paradigm.

Organization design interventions address the different elements that comprise the “architecture” of the organization, including structure, work design, human resources practices, and management processes. In either domestic or worldwide settings, organization design interventions seek to fit or align these components with each other so they direct members' behaviors in support of a strategic direction. Integrated strategic change is a comprehensive OD intervention that builds on the systemic and revolutionary nature of transformational change. It leverages traditional change management frameworks and aims to transform a single organization or business unit. It suggests that business strategy and organization design must be aligned and changed together to respond to external and internal disruptions. A strategic change plan helps members manage the transition between the current strategic orientation and the desired future strategic orientation.

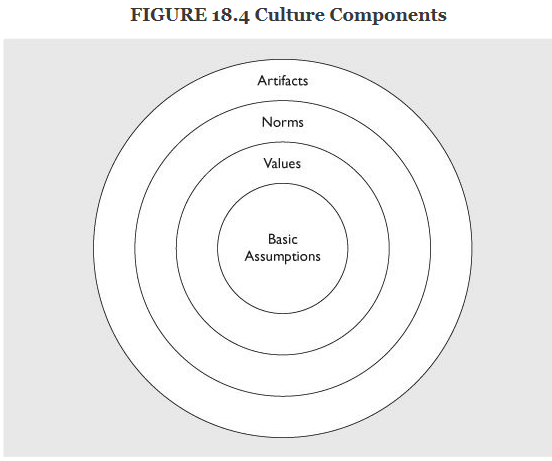

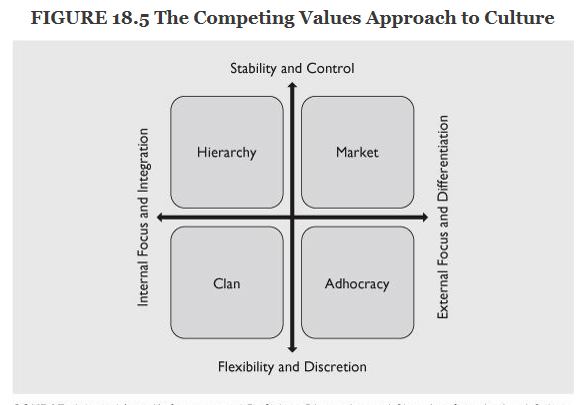

Organizational culture is the pattern of assumptions, values, and norms regarding correct behavior that is shared, more or less, by organization members. A growing body of research confirms that culture can affect strategy formulation and implementation as well as the firm's ability to achieve high levels of performance.1 Culture change involves helping senior executives and administrators diagnose the existing culture and make necessary alterations in the basic assumptions and values underlying organizational behaviors.

18-1 Characteristics of Transformational Change

Organization transformation implies radical changes in how members perceive, think, and behave at work. These changes go far beyond making the existing organization better or fine-tuning the status quo. They are concerned with fundamentally altering the prevailing assumptions about how the organization functions and relates to its environment. Changing these assumptions entails significant shifts in corporate values and norms and in the structures and organizational arrangements that shape members' behaviors. Not only is the magnitude of change greater, but it can fundamentally alter the qualitative nature of the organization.

18-1a Change Is Triggered by Environmental and Internal Disruptions

Increased global competition and the lingering economic recession are forcing many organizations to engage in radical changes to their operating strategies and structures, downsize or consolidate, or become leaner, more efficient, and flexible.2 Global warming, social unrest, and the rise of watchdog nongovernmental organizations are pushing firms to implement a variety of corporate social responsibility and sustainability initiatives. Public demand for less government intervention and lower deficits conflicts with expectations of support during hard times. Public sector agencies must try to expand services, streamline operations, and deliver more for less. Rapid changes in technologies render many organizational practices obsolete, pushing firms to be continually innovative and agile.

However, research suggests that traditional organizations are unlikely to undertake transformational change without significant reasons to do so.3 Power, emotion, and expertise are vested in the existing organizational arrangements, and when faced with problems, organizations are more likely to fine-tune those structures than to alter them drastically. Thus, in most cases, organizations must experience or anticipate a severe threat to survival before they will be motivated to undertake large-scale, transformational change.4 Such threats arise when environmental and internal changes render existing organizational strategies and designs obsolete. These disruptions threaten the existence of the organization's current design and the likelihood of continuing to perform at a high level.

In studying a large number of organization transformations, researchers suggest that large-scale change occurs in response to at least three kinds of disruption:5

1. Industry discontinuities—sharp changes in legal, political, economic, and technological conditions that shift the basis for competition within an industry.

2. Product life cycle shifts—changes in product life cycle that require different business strategies or business models.

3. Internal company dynamics—changes in size, corporate portfolio strategy, or executive turnover.

In each case, the organization's current or future performance is threatened in substantive ways. These disruptions severely jolt organizations and push them to question their business strategy and, in turn, their organization's design.

18-1b Change Is Initiated by Senior Executives and Line Managers

Senior executives and line managers usually initiate transformational change.6 They are responsible for maintaining the organization's character and performance. As a result, senior managers decide when to initiate large-scale change, what the change should be, how it should be implemented, and who should be responsible for directing it. Because existing executives may lack the talent, energy, or commitment to undertake these tasks, the organization may recruit outsiders to lead the change. Externally recruited executives are three times more likely to initiate such change than are existing executives.7

Executive leadership in large-scale and transformational change is critical, especially when the change must happen quickly. Lucid accounts of transformational change describe how executives, such as Ray Anderson at Interface Carpet, Lou Gerstner at IBM, and Victor Fung at Li and Fung, actively managed both the organizational and personal dynamics of transformational change. Researchers have identified four key roles for executive leadership during transformational change:8

• Envisioning. Executives must articulate a clear, credible, compelling, and consistent vision of the new strategic orientation. During changes of this magnitude, it is imperative that leaders throughout the organization maintain the message and their commitment to a desired future state that is fundamentally better than the current one. In periods of change, when anxiety is elevated, people need to know that everyone in the organization is committed to the new organization and its purpose. Creating and discussing the organization's future configuration is a leadership behavior that helps to meet this need.

• Energizing. Executives must demonstrate personal excitement for the changes and model the behaviors that are expected of others. Behavioral integrity, credibility, and “walking the talk” are important ingredients.9 Christening initiatives and allocating resources to key transformation tasks in line with the vision demonstrates that commitment. Change is accelerated when organization members see important and scarce resources being devoted to large-scale change tasks. Executives must provide the resources necessary for undertaking significant change and use rewards to reinforce new behaviors.

• Enabling. The third leadership behavior that contributes to large-scale change is communication that helps people make sense of transformation. They must communicate examples of early success to mobilize energy for change. By “connecting the dots”—showing people how certain accomplishments, results, milestones, and other activities are working together to achieve the transformation—leaders help organization members understand that change can happen and is happening.

• Engaging. Executives also must set new and difficult standards for performance, and hold people accountable to those new standards. During transformational change, the organization explicitly or implicitly voids prior employment relationship understandings and all of its implied behaviors and incentives. Managers must lay out the new expectations and incentives. Sending clear signals in conversations with people about the values and behaviors that will be supported in the new organization—and those values and behaviors that will not be supported—is an important contributor to transformational change. While there must be an appropriate recognition for past performance and pride in past accomplishments, there must also be enthusiastic support for the new strategy.

18-1c Change Involves Multiple Stakeholders

Transformational change invariably affects many organization stakeholders, including owners, managers, employees, vendors, regulators, and most importantly, customers. An organization's current performance is the result of tacit and explicit coordination among a variety of stakeholders. As performance declines due to the internal or external disruptions described above, these different stakeholders are likely to have different goals and interests related to the change process. Unless the differences are revealed and reconciled, enthusiastic support for change may be difficult to achieve. Consequently, the change process must attend to the interests of multiple stakeholders.10

The creation of a “stakeholder map” or open systems plan, such as that described in Chapter 11, facilitates transformational change.11 It helps to document the current demands of relevant stakeholders, the current organizational responses to each stakeholder, how each stakeholder's demands are changing or likely to change, and the implications of those changes on the organization's mission and strategy. Involving a variety of organization stakeholders creates an accurate view of the environment, organization, and the change challenges.

18-1d Change Is Systemic and Revolutionary

Transformational change involves reshaping the organization's strategy and design elements to affect culture and performance. These changes can be characterized as systemic and revolutionary because the focus is on the realignment of the entire organization in a relatively short period of time.

An organization's design includes the structure, work design, human resources practices, and management processes that support the business strategy. Because each of these features significantly affects member behavior, they need to be designed and changed together to reinforce their mutual support of a new strategic direction and its desired behaviors.12 This comprehensive and systemic view of transformational change contrasts sharply with piecemeal approaches that address the design elements separately. A fragmented approach risks misaligning design elements and sending mixed signals about desired behaviors.13 For example, many organizations have experienced problems implementing team-based structures because their existing human resource systems emphasize individual-based performance.

Longitudinal change studies also underscore the revolutionary nature of transformational change and point to the benefits of implementing change as rapidly as possible.14 Organizations often move through relatively long periods of smooth growth, operational improvements, and incremental changes. At times, however, they experience severe external or internal disruptions that render existing organizational arrangements ineffective. Successful firms respond to these survival threats by transforming themselves to fit the new conditions. Examples of successful transformational change include IBM, Harley Davidson, and DaVita. These periods of total system and quantum change represent abrupt shifts in the organization's strategy, structure, and processes. Also, the majority of the people in the organization change their behavior.15 Typically driven by senior executives, change occurs rapidly so that it does not get mired in politics, individual resistance, and other forms of organizational inertia.16 The faster the organization can respond to disruptions, the quicker it can attain the benefits of operating in a new way. If successful, the shift enables the organization to experience another long period of smooth functioning until the next disruption signals the need for drastic change.17

18-1e Change Involves Significant Learning and a New Paradigm

Organizations undertaking transformational change are, by definition, involved in second-order or gamma types of change.18 Gamma change involves discontinuous shifts in mental or organizational frameworks19 and therefore requires much learning and innovation.20 Organizational members must learn how to enact the new behaviors required to implement new strategic directions. This typically involves trying new behaviors, assessing their consequences, and modifying them if necessary. Because members usually must learn qualitatively different ways of perceiving, thinking, and behaving, the learning process is likely to be substantial and to involve a considerable amount of “unlearning.”

Creative metaphors, such as “organization learning” or “continuous improvement,” are often used to help members visualize the new paradigm.21 Increases in technological change, changes in climate patterns, concern for quality, and worker participation have led many organizations to shift their organizing paradigm. This transformation has been characterized as the transition from a “command and control-based” paradigm to a “commitment-based” or “sustainability-based” paradigm.22 The features of the new paradigm include broader, more inclusive organizational goals; leaner, more flexible structures; information and decision making pushed down to the lowest levels; decentralized teams and business units accountable for specific products, services, or customers; and participative management and teamwork. This new organizing paradigm is well suited to changing conditions. Thus, a compelling vision of the future organization and the values and norms needed to support it also encourage the learning process. Because the environment itself is likely to be changing during the change process, transformational change often has no clear beginning or ending point but is likely to persist as long as the firm needs to adapt to change. Learning how to manage change continuously can help the organization keep pace with a dynamic environment. It can provide the built-in capacity to fit the organization continually to its environment. Chapter 19 presents OD interventions for helping organizations gain this capability for continuous change and learning.

18-2 Organization Design

Organization design configures the organization's structure, work design, human resources practices, and management processes to guide members' behaviors in a strategic direction. This intervention typically occurs in response to a major change in the organization's strategy that requires fundamentally new ways for the organization to function and members to behave. It involves many of the organizational features discussed in previous chapters such as restructuring organizations (Chapter 12), work design (Chapter 14), and performance management (Chapter 15).

18-2a Conceptual Framework

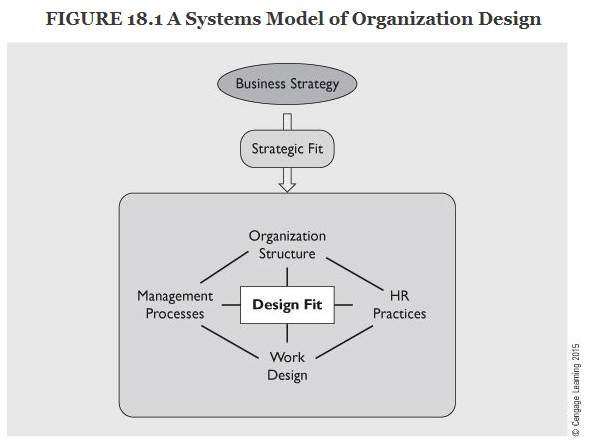

A key notion in organization design is “fit,” “congruence,” or “alignment” among the organizational elements.23 Figure 18.1 presents a systems model similar to the one presented in Chapter 5 showing the different components of organization design and the interdependencies among them. It highlights the idea that the organization is designed to support a particular strategy (strategic fit) and that the different design elements must be aligned with each other and all work together to guide members' behavior in that strategic direction (design fit). Research shows that the better these fits, the more effective the organization is likely to be.24 These design components have been described previously in this book, so they are reviewed briefly below.

• Business strategy determines how the organization will use its resources to gain competitive advantage and achieve its objectives in the short to medium term. It may change, for example, the degrees of breadth, aggressiveness, and differentiation to focus on introducing new products and services (innovation strategy) or controlling costs and reducing prices (cost-minimization strategy). Strategy sets the direction for organization design by identifying the organizational capabilities needed to make the strategy happen.

• Structure describes how the organization divides tasks, assigns them to departments, and coordinates across them. It generally appears on an organization chart showing the chain of command—where formal power and authority reside and how departments relate to each other. Structures can be highly formal and promote control and efficiency, such as a functional structure; or they can be loosely defined, flexible, and favor change and innovation, such as a matrix, process, or network structure.

• Work design specifies how tasks are performed and assigned to individual or groups to add value. That is, work and organization design must be aware of the underlying processes that transform inputs into valued outputs. Work design can create traditional jobs and groups that involve standard tasks with little task variety and decision making or enriched jobs and self-managed teams that involve highly variable, challenging, and discretionary work.

• Human resource practices involve recruiting, selecting, developing, and rewarding people. These methods can be oriented to hiring and paying people for specific jobs, training them when necessary, and rewarding their individual performance. Conversely, human resource practices can also select people to fit the organization's culture, continually develop them, and pay them for learning multiple skills and contributing to business success.

• Management processes describe how goals are set, how decisions are made, how resources are allocated, and how information and knowledge is stored and communicated. Managers can set direction, allocate resources, or make decisions using a command and control style that relies on hierarchical authority and the chain of command; or they can utilize highly participative methods that facilitate employee involvement. Information can be tightly controlled and centralized, with limited access and data sharing; or it can be transparent and shared freely throughout the organization.

18-2b Basic Design Alternatives

Table 18.1 shows how these design components can be configured into two radically different organization designs: mechanistic, supporting efficiency and control, and organic, promoting innovation and change.25 Mechanistic designs have been prevalent in organizations for over a century; they propelled organizations into the industrial age. Today, competitive conditions require many organizations to be more flexible, fast, and inventive.26 Thus, organization design is aimed more and more at creating organic designs, both in entirely new start-ups and in existing firms that reconfigure mechanistic designs to make them more organic. Designing a new organization is much easier than redesigning an existing one in which multiple sources of inertia and resistance to change are likely embedded.

TABLE 18.1 Organization Designs

| Mechanistic Design | Organic Design | |

| Strategy |

|

|

| Structure |

|

|

| Work design |

|

|

| Human resources practices |

|

|

| Management processes |

|

|

| © Cengage Learning | ||

As shown in Table 18.1, a mechanistic design supports an organization-strategy emphasizing cost minimization, such as might be found at Carrefour and McDonalds or other firms competing on price. The organization tends to be structured into functional departments, with employees performing similar tasks grouped together for maximum efficiency. The managerial hierarchy is the main source of coordination and control. Accordingly, work design follows traditional principles, with jobs and work groups being highly standardized with minimal decision making and skill variety. Human resources practices are geared toward selecting people to fit specific jobs and training them periodically when the need arises. Employees are paid on the basis of the job they perform, share a standard set of fringe benefits, and achieve merit raises based on their individual performance. Management processes stress centralized decision making, with power concentrated at the top of the organization and orders flowing downward through the chain of command. Similarly, communication and goal setting systems are driven from the top. Information is not widely shared. When taken together, all of these design elements direct organizational behavior toward efficiency and cost minimization.

Table 18.1 shows that an organic design supports an organization strategy aimed at innovation, such as might be found at 3M, Google, and Unilever or other firms competing on new products and services. All the design elements are geared to getting employees directly involved in the innovation process, facilitating interaction among them, developing and rewarding their knowledge and expertise, and providing them with relevant and timely information. Consequently, the organization's structure tends to be flat, lean, and flexible like the matrix, process, and network structures described in Chapter 12. Work design is aimed at employee motivation and decision making with enriched jobs and self-managed teams. Human resources practices focus on attracting, motivating, and retaining talented employees. They send a strong signal that employees' knowledge and expertise are key sources of competitive advantage. Members are selected to fit an organization culture valuing participation, teamwork, and invention. Training and development are intense and continuous. Members are rewarded for learning multiple skills, have choices about fringe benefits, and gain merit pay based on the business success of their work unit. Management processes are highly participative and promote employee involvement. Communication systems are highly open, inclusive, and transparent providing relevant and timely information throughout the organization. In sum, these design choices guide members' behaviors toward change and innovation.

Application 18.1 describes organization design at Deere & Company27 It illustrates how the different design elements must fit together and reinforce each other to promote a high-performance organization.

18-2c Worldwide Organization Design Alternatives

An important trend facing many business firms is the emergence of a global marketplace. Driven by competitive pressures, lowered trade barriers, increased knowledge work, and advances in information technologies, the number of companies developing or offering products and services in multiple countries continues to rise. Worldwide organizations28 offer products or services and actively manage direct investments in more than one country; must balance product and functional concerns with geographic issues of distance, time, and culture; and must carry out coordinated activities across cultural boundaries using expatriates, short-term and extended business travelers, and local employees. They must relate to a variety of demands, such as unique product requirements, tariffs, value-added taxes, governmental and environmental regulations, labor practices, transportation laws, and trade agreements, and adapt their human resources policies and procedures to fit different cultures. Tobacco companies, for example, face technological, moral, and organizational issues in determining whether to market cigarettes in less-developed countries, and if they do, they must decide how to integrate manufacturing and distribution operations on a global scale. The organizational complexity associated with managing these organizations is challenging.

How these firms choose to arrange their products/services, organization, and personnel enable them to compete in the global marketplace.29 Despite the many possible combinations, researchers have found that two dimensions are useful in guiding managerial decisions about these choices.

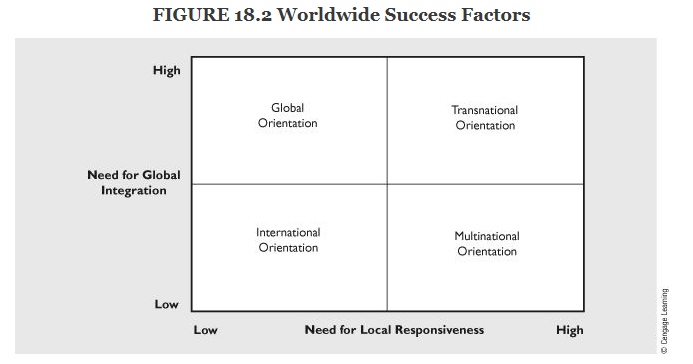

As shown in Figure 18.2, managers need to assess two key success factors: the degrees to which there is a need for global integration or for local responsiveness.30 Global integration refers to whether or not business success requires tight coordination of people, plants, equipment, products, or service delivery on a worldwide basis. For example, Intel's “global factory” designs semiconductors in multiple countries, manufactures them in a variety of locations around the world, assembles and tests the finished products in different countries, and then ships the final product to customers. All of this activity must be coordinated carefully to maintain an integrated flow of goods. Local responsiveness, on the other hand, is the extent to which business success is dependent on customizing products, services, support, packaging, and other aspects of operations to local conditions. Intel has to do very little customization; a microprocessor is a microprocessor everywhere in the world.

application 18.1 ORGANIZATION DESIGN AT DEERE & COMPANY

Deere & Company, one of the world's leading producers of agricultural, construction, forestry, and turf care equipment, has a rich history of dedicated employees, quality products, and loyal customers. When Robert W. Lane, an 18-year veteran of Deere, became Chairman and CEO in August of 2000, however, economic and organizational problems were threatening this tradition. The company's operations were capital intensive, extremely decentralized, and spread across a diversity of products with highly cyclical business cycles. This meant that overall company profitability required constant vigilance and comparison of profit margins across products with an eye to reducing cyclical swings and to optimizing the whole business and not just a particular business unit. Unfortunately, Deere focused too loosely on managing assets and profit margins and was too decentralized to do business this way, often wasting economic value. Lane described the firm as “asset heavy and margin lean.” Moreover, Deere was having problems keeping pace with a rapidly changing and demanding global business environment.

With the support of a unified senior team, Lane immediately created a plan to manage assets more efficiently, to make a new generation of products geared to emerging market demands, and to reduce the firm's vulnerability to cyclical swings and uncertain agriculture and construction markets which together accounted for about 70% of Deere's sales. To make the plan work over the next several months, Lane made a number of related changes in the company's management and information systems, structure, and human resources practices.

Deere's redesign effort started with a simple yet powerful approach to measuring firm performance: shareholder value added (SVA), which is net operating profit after taxes minus cost of capital. Because this value-based metric is straightforward and intuitive, it was easily understood and embraced by operating people throughout the firm. SVA became the central tool for managing the company's business. It provided a common performance measure that could be applied to every product; it addressed the fundamental question: What value does this product add to Deere's shareholders?

Consistent with this new performance measure, Deere restructured its largest division, agriculture, into two business units: worldwide harvesting and tractors/implements. This enabled each new unit to focus more diligently on the underlying economics of its products. It also provided for a far more integrated business than the previous structure allowed. Thus, for example, worldwide harvesting could now get its combine harvester factories in Asia, Europe, and North America to all work together as one global product team with common metrics. It could also do the same for its factories that made cotton pickers and so on.

Next, Lane introduced an online performance management system to align goals and rewards with SVA. All 18,000 salaried employees now had to develop goals that were explicitly linked to the firm's goals. Specific SVA targets were set for each product line at various points in the business cycle. High expectations for improvements in operating performance and SVA growth were set and widely communicated. Then, rewards were tied directly to progress on meeting those objectives. The simplicity and consistency of this system focused employee behaviors on the economics of the business and reinforced the need to continuously improve performance and raise SVA.

Finally, Lane made significant changes in Deere's talent mix to better meet the higher performance standards and the increasing demands of global competition. Employee selection and training practices were oriented to acquiring and developing a workforce with a strong customer orientation and collaborative skills. Employees needed to understand customer needs fully so they could respond with appropriate technological solutions and product innovations. They needed to be able to work together in teams on a worldwide basis.

Six years into Deere's organization redesign, financial results were remarkable. In contrast to 2003, the firm's 2006 net income more than doubled and revenues were up almost 50%. In 2006, SVA was near $1 billion. Perhaps more important, Deere's culture had shifted from mainly family values to those promoting a high-performance organization.

Based on that information, worldwide organization development involves one of four designs: international, global, multinational, or transnational. Table 18.2 presents these designs in terms of the features described above. Each design is geared to specific market, technological, and organizational requirements.

The International Design The international design exists when the key success factors of global integration and local responsiveness are low. This is the most common label given to organizations making their first attempts at operating outside their own country's markets. Success requires coordination between the parent company and the small number of foreign sales and marketing offices in chosen countries. Similarly, local responsiveness is low because the organization typically exports the same products and services offered domestically.

TABLE 18.2 Design Characteristics for Worldwide Strategic Orientations

| Worldwide Strategic Orientation | Business Strategy | Structure | Management Processes | Human Resources |

| International | Existing products Goals of increased foreign revenues | International division | Loose but centralized Learning orientation | Volunteer recruitment Retain existing performance management processes |

| Global | Standardized products Goals of efficiency through volume | Global product divisions Global functions | Formal and centralized | Ethnocentric selection Rewards for enterprise performance |

| Multinational | Tailored products Goals of local responsiveness through specialization | Decentralized operations; centralized planning Global geographic divisions | Profit centers | Regiocentric or poly-centric selection Rewards for regional performance |

| Transnational | Tailored products Goals of learning anc responsiveness through integration | Decentralized, worldwide coordination Global matrix or network | Subtle, clan-oriented controls Learning orientation | Geocentric selection |

| © Cengage Learning | ||||

The goal of an international organization is to increase total sales by adding revenues from nondomestic markets. By using existing products/services, domestic operating capacity is extended and leveraged. As a result, most domestic companies will enter international markets by extending their product lines first into nearby countries and then expanding to more remote areas. For example, most U.S.-based companies first offer their products in Canada or Mexico. If a certain period of successful performance and learning occur, they may begin to set up operations in other countries.

To support this goal and operations strategy, an “international division” is given responsibility for marketing, sales, and distribution, although it may be able to set up joint ventures, licensing agreements, distribution territories/franchises, and in some cases, manufacturing plants. The organization retains its original structure and operating practices. The management processes governing the division are typically looser, however. While expecting returns on its investment, the organization recognizes the newness of the venture and gives the international division some “free rein” to learn about operating in a foreign context.

Finally, roles in the new international division are staffed with volunteers from the parent company, often with someone who has appropriate foreign language skills, experience living overseas, or eagerness for an international assignment. Little training or orientation for the position is offered as the organization is generally unaware of the requirements for being successful in international business.

The Global Design This design is appropriate when the need for global integration is high but the need for local responsiveness is low. The decision to favor global integration over local responsiveness must be rooted in a strong belief that the worldwide market is relatively homogenous in character. That is, products and services, support, distribution, or marketing activities can be standardized without negatively affecting sales or customer loyalty. This decision should not be made lightly, and OD practitioners can help to structure rigorous debate and analysis of this key success factor.

The global organization is characterized by a strategy of marketing standardized products in different countries. It is an appropriate orientation when there is little economic reason to offer products or services with special features or locally available options. Manufacturers of heavy equipment (Caterpillar and Komatsu), bathroom fixtures (American Standard, Toto), computers (Dell, HP, Lenovo), and tires (Michelin and Goodyear), for example, can offer the same basic product in almost any country.

The goal of efficiency dominates the design choices for this orientation. Production efficiency is gained through volume sales and a small number of large manufacturing plants, and managerial efficiency is achieved by centralizing product design, manufacturing, distribution, and marketing decisions. The close physical proximity of major functional groups and formal control systems that balance inputs, production, and distribution with worldwide demand supports global integration. Many Japanese firms, such as Honda, Sony, NEC, and Matsushita, used this strategy in the 1970s and early 1980s to grow in the international economy. In Europe, Nestlé exploits economies of scale in marketing by advertising well-known brand names around the world. The increased number of microwave and two-income families, for example, allowed Nestlé to push its Nescafé coffee and Lean Cuisine low-calorie frozen dinners to dominant market-share positions in Europe, North America, Latin America, and Asia.

In the global design, the organization tends to be centralized with a global product structure. Presidents of each major product group report to the CEO and form the line organization. Each of these product groups is responsible for worldwide operations. Management processes in global organizations tend to be quite formal with local units reporting sales, costs, and other data directly to the product president. The predominant human resources policy integrates people into the organization through ethnocentric selection and staffing practices. These methods seek to fill key foreign positions with personnel from the home country where the corporation headquarters is located.31 Key managerial jobs at Emerson, Siemens, Nissan, and Michelin, for example, are often occupied by American, German, Japanese, and French citizens, respectively. Ethnocentric policies support the global orientation; expatriate managers are more likely than host-country nationals to recognize and comply with the need to centralize decision making and to standardize processes, decisions, and relationships with the parent company. Although many Japanese automobile manufacturers have decentralized production, Nissan's global strategy has been to retain tight, centralized control of design and manufacturing, ensure that almost all of its senior foreign managers are Japanese, and have even low-level decisions emerge from face-to-face meetings in Tokyo.

Application 18.2 describes how one organization faced the challenges of implementing a global strategy.32 They tried to find the right balance between strong headquarters control and local responsiveness. The OD practitioner in the case describes her data, actions, and results.

The Multinational Design This design is appropriate when the need for global integration is low, but the need for local responsiveness is high. The decision to favor local responsiveness over global integration must be made with the same analytic rigor described earlier. In this case, the analysis must support the belief that worldwide markets are relatively heterogeneous in character. That is, success requires customized and localized products and services, support, distribution, or marketing activities. It represents a strategy that is conceptually quite different from the global strategic orientation.

application 18.2 IMPLEMENTING THE GLOBAL STRATEGY: CHANGING THE CULTURE OF WORK IN WESTERN CHINA

China has a strong culture, but one that allows it, paradoxically, to assimilate other ideas and philosophies. For example, Buddhism was added to Confucianism during the heydays of the Silk Road, and China has adapted to globalization quickly since it began market reforms in the early 1990s. For many firms entering China, the question is, “Will China assimilate Western cultural ways from the multinational corporations that enter, or will they insist on a Chinese cultural process of doing business?” This application describes the process one American technology company utilizing a global worldwide strategy used in opening a manufacturing plant in a western Chinese province. The story is told from the perspective of the internal OD consultant who was charged with plant start-up support.

In 2003, a major U.S. multinational broke ground for a new set of factories in the “second tier” Chinese city of Chengdu. A city of more than ten million people in Western China, Chengdu is correctly considered the heartland of Chinese culture with a strong tradition of Taoism and a relaxed, friendly culture. In contrast, the multinational technology company came to western China with a strong business-centered, “just get results,” U.S. culture. While the organization had facilities all over the world, and several in China, it had not started-up a true greenfield plant as the first MNC in a city in more than ten years. In keeping with the firm's global strategy, the corporate headquarters expected each plant to integrate seamlessly with other plants in the supply chain. Low costs and meeting the technical specifications of the product were the key measures of performance.

The first time I saw the factory site in Chengdu it was bare dirt with the wind blowing dust over what had been a farmer's field. Even as the buildings came out of the ground—an office building, one factory and then another, a large warehouse, and a training center—the local culture of Chengdu was being challenged in the way it thought about safety. In China, construction projects have a traditional algorithm for safety: the millions of Yuan (the local currency) spent in construction was proportionate to the number of deaths resulting from it. This project was different. There was a clear expectation that no deaths would occur, and that no injuries more serious than cut fingers were going to be tolerated. Subcontractors were required to wear hard hats, steel-toed shoes, goggles, and the like, and not everyone liked it. One subcontractor walked off the job believing the safety equipment was too burdensome.

About 30 expatriates were brought in to manage the site. They were experienced company employees from four different cultures: Malaysia, Philippines, Costa Rica, and the United States. Most were Malaysian; very few were American. The first local employees hired were support personnel in human resources, accounting, and purchasing. They were trained in their jobs in the way that the company expected them to work. The first Chinese factory workers were part of the Early Involvement Team (EIT), and they were sent to another of the company's factories to learn the correct processes and behaviors necessary to run the production lines. When the EIT returned, they were to teach the next generation of employees. While this training could be considered just learning the job, it was also a culture change for people who had never worked in a Western high-tech factory. Ramping up this factory to production required that we hire and integrate 100 to 200 people per month; 70% of those hired were recent college graduates.

As the OD manager, my job was to set up systems to transmit the culture and develop leaders, managers, and teams. I began with the site's Vision, Mission, and Guiding Principles. To help the team begin the process, I defined the Vision as “the best we could be,” the Mission as “our marching orders—what the corporation expected of us” and Guiding Principles as “how we make decisions and treat each other.” We utilized two off-site sessions with the “whole system in the room.” Inclusive processes employing exercises and conversations about what was important to people were used to formulate beginning statements. After we had a set of draft statements, I formed small teams of Chinese leaders who debated the elements of Vision, Mission, and Guiding Principles. The teams came to consensus for each statement to ensure that both the English and Chinese words we used reflected Chinese culture and spoke in a way that fit the Chinese thought processes. We unpacked each statement using Chinese metaphors to provide depth of meaning. Essentially, we were defining the site's specific culture, which while congruent with the corporation, was specific to this site and its chosen values. When completed, these statements went back to the site leadership for ratification. To disseminate the Vision, Mission, and Guiding Principles, each leader, whether expatriate or local Chinese, took responsibility to waterfall the message to their team using dialogues to explore the meaning of the statements for the team. It was not enough to have posters on the wall, or simply tell people what they were. People needed to talk through the meaning and come to some conclusion for themselves as to their own belief. Additionally, people needed to see that leadership practiced what they espoused. So, when an important site decision was made, its fit with the Guiding Principles was publicly communicated. When certain initiatives were begun, such as management training, it was tied to the site Vision. Only because people could see the Vision, Mission, and Guiding Principles in practice did they become real.

Before the first building was under construction, I came to Chengdu to do the initial cultural research for the site. I interviewed university students, business leaders, and Chinese cultural experts in Chengdu. I found a disparity between how the middle managers viewed management and leadership and what the young, university students wanted in a manager. As this was the first multinational organization in Chengdu, most of the middle managers we hired were from state-owned enterprises with a very top-down, hierarchical culture. The university students expected Western-style, consensual decision making—a clear mismatch even within the Chinese culture. Management training and coaching would be required to help middle managers learn to work in a consensual way.

To accomplish that, we engaged the expatriate site leaders as teachers and mentors in a nine-month management development program that included two outdoor “adventure-style” sessions. The first program placed the initial outdoor session after four months of activities. I found that in the classroom, Chinese managers could “talk the talk,” but when we put them in the team decision-making situations of the outdoor sessions, they were unable to make productive decisions. In the second management development program, I placed the outdoor session earlier so that the Chinese managers would understand the required managerial behaviors right away. We eventually graduated more than 50 managers with two-thirds of them receiving promotions within a year of completion.

The corporation had a number of key espoused values in its culture, including quality, safety, and business practice excellence. These were primary and nonnegotiable values. While that may seem the arbitrary hubris of a foreign multinational, I found that the Chinese employees appreciated these three values, especially safety. As mentioned above, China has a poor record of workplace safety. When asked about this value, many people responded that “the company cares for my life.” Rather than seeing it as an imposition of a foreign cultural value, they found it fit the Chinese value of renqing or human heartedness.

The company also employed six values as basic to its culture. However, these values were really expected behaviors, such as discipline, risk taking, and being open and direct. In my work in Chengdu, I designed and implemented a process to develop those values as part of the expected behaviors of the site. I had learned that “telling-teaching,” or putting posters on the wall, was not very effective in this culture, so I engaged a cadre of volunteer “ambassadors” for each value. They used a positive approach of catching people “doing it right” and rewarding them in a public ceremony with a “Star of Chengdu Culture” award. To create a common understanding of each value, we again used an interactive and participative process. We provided materials that allowed and encouraged every manager to have a conversation with their team as to the meaning of that particular value. We endeavored to make the materials relevant to a Chinese audience using Chinese stories and situations to illustrate the meaning of the value.

However, not all these values fit within Chinese culture, and this created cultural dilemmas for Chinese employees. Being open and direct was one example of a value that did not fit. Generally, the organization talked about being open and direct in terms of “constructive confrontation,” which the Chinese employees shortened to “con con.” In my interviews, I found that this value was both the most difficult and the least practiced. The Chinese employees related con con to a lack of harmony rather than a method of solving problems directly and easily. It was antithetical to Chinese culture. Chinese employees who learned to practice con con in the workplace found themselves out of step when those behaviors were used with their family and friends outside of the factory. Essentially they had to bifurcate their life, learning to be one way inside the organization and another way outside. When I asked people what they lost by coming to work at the factory, employees often noted that they had lost some friends because they were now different from the Chinese culture at large. Practicing con con was a big part of that. They also told me of many instances in which they appeared to the expatriates as though they were practicing con con, when in fact they were practicing harmony. They felt that harmony was a better long-term solution to the problem at hand than creating a situation in which fellow workers lost “face.” They talked about finding a “middle way” to do business that allowed problem solving while still maintaining harmonious relationships.

If real cultural differences can keep people from assimilating into an organization, the question becomes, “Did these skilled Chinese workers actually assimilate into the factory culture, or did they simply appear to apply the organization's value system while maintaining traditional Chinese values?” While much of the work on Values, Mission, and Guiding Principles was well accepted and understood, the Chinese workers in this situation had difficulty placing con con into a usable framework that worked in their social setting because it did not align with the Chinese value of harmony. Since con con was a foundational behavior/value for the company, such a misfit reveals a lack of real assimilation into the corporate culture.

Some Chinese lament that China is losing her cultural traditions as the country becomes part of the global economy. At least in Chengdu, I did not find that to be true. People described themselves as traditional Chinese who practiced their own culture and struggled with those organizational processes that did not fit Chinese culture. They continued to look for the middle way that allows them to maintain their Chinese cultural values while moving into a capitalistic future. Just as China assimilated Buddhism into their Confucian practices millenniums ago, they see the value of assimilating some Western practices into their way of doing business, but it will still be capitalism with a Chinese face—a middle way.

A multinational organization is characterized by a product line that is tailored to local conditions and is best suited to markets that vary significantly from region to region or country to country. At American Express, for example, charge card marketing aligns to local values and tastes. The “Don't leave home without it” and “Membership has its privileges” brand messages that were popular in the United States had to be translated to “Peace of mind only for members” in Japan because of the negative connotations of “leaving home” and “privilege.”33

The multinational design emphasizes a decentralized, global division structure. Each regional or country division reports to headquarters but operates autonomously and mostly controls its own resources. This results in a highly differentiated and loosely coordinated corporate structure. Operational decisions, such as product design, manufacturing, and distribution, are decentralized and tightly integrated at the local level. For example, laundry soap manufacturers offer product formulas, packaging, and marketing strategies that conform to the different environmental regulations, types of washing machines, water hardness, and distribution channels in each country. On the other hand, planning activities are often centralized at corporate headquarters to achieve important efficiencies necessary for worldwide coordination of emerging technologies and of resource allocation. A profit-center control system allows local autonomy as long as profitability is maintained. Examples of multinational corporations include Hoechst and BASF of Germany, MTV and Procter & Gamble of the United States, and Fuji Xerox of Japan. Each of these organizations encourages local subsidiaries to maximize effectiveness within their geographic region.

People are integrated into multinational firms through polycentric or regiocentric personnel policies because these firms believe that host-country nationals can understand native cultures most clearly34 By filling positions with local citizens who appoint and develop their own staffs, the organization aligns the needs of the market with the ability of its subsidiaries to produce customized products and services. The distinction between a polycentric and a regiocentric selection process is one of focus. In a polycentric selection policy, a subsidiary represents only one country; in the regiocentric selection policy, the organization takes a slightly broader perspective and regional citizens (that is, people who might be called Europeans, as opposed to Belgians or Italians) fill key positions.

The Transnational Design This orientation exists when the need for global integration and local responsiveness are both high. It represents the most complex and ambitious worldwide strategic orientation and reflects the belief that products or services should be developed, produced, or distributed in the places where it makes the most sense but customized to sell anywhere.35

The transnational design combines customized products with both efficient and responsive operations; the key goal is learning. This is the most complex worldwide strategic orientation because transnationals can manufacture products, conduct research, raise capital, buy supplies, and perform many other functions wherever in the world the job can be done optimally. They can move skills, resources, and knowledge to regions where they are needed.

Transnational organizations combine the best of global and multinational design and add a third capability—the ability to transfer resources both within the firm and across national and cultural boundaries. Otis Elevator, a division of United Technologies, developed a new programmable elevator using six research centers in five countries: a U.S. group handled the systems integration; Japan designed the special motor drives that make the elevators ride smoothly; France perfected the door systems; Germany created the electronics; and Spain produced the small-geared components.36 In addition, Otis has the production capability to ensure that all the parts made in different places all fit together perfectly as well as the logistics capability to guarantee that all the parts will arrive at a specific job site on the right day. Other examples of transnational firms include General Electric, Asea Brown Boveri (ABB), Unilever, Electrolux, HP, and most worldwide professional services firms.

Transnational firms organize themselves into global matrix and network structures especially suited for moving information and resources to their best use. In the matrix structure, local sales and marketing divisions are crossed with product groups at the headquarters office, engineering groups in different countries, and other dimensions as required. The network structure treats each local office, including headquarters, product groups, functions, call centers, and production facilities, as self-sufficient nodes that coordinate with each other to move knowledge and resources to their most valued place. Because of the heavy communication and logistic demands needed to operate these structures, transnationals have sophisticated information systems. State-of-the-art information technology stores and moves strategic and operational information and knowledge throughout the system rapidly and efficiently. Organizational learning practices (see Chapter 19) gather, organize, and disseminate the knowledge and skills of members who are located around the world.

People are integrated into transnational firms through a geocentric selection policy that staffs key positions with the best people, regardless of nationality.37 This staffing practice recognizes that the unique capability of a transnational firm is its capacity to optimize resource allocation on a worldwide basis. Unlike global and multinational firms, which spend more time training and developing managers to fit the strategy, the transnational firm attempts to hire the right person from the beginning. Recruits at any of HP's foreign locations, for example, are screened not only for technical qualifications but for personality traits that match the company's cultural values.

18-2d Application Stages

Organization design can be applied to the whole organization or to a major subpart, such as a large department or stand-alone unit. It can start from a clean slate in a new organization or more commonly, reconfigure an existing organization design. To construct the different design elements appropriately requires broad content knowledge of them. Thus, organization design interventions typically involve a team of OD practitioners with expertise in business strategy, organization structure, work design, human resources practices, and management processes. This team works closely with senior executives who are responsible for determining the organization's strategic direction and leading the organization design intervention. The design process itself can be highly participative, involving stakeholders from throughout the organization. This can increase the design's quality and stakeholders' commitment to implementing it.38

Organization design interventions generally follows the three broad steps outlined below.39 Although they are presented sequentially, in practice they are highly interactive, often feeding back on each other and requiring continual revision as the process unfolds.

1. Diagnosing the current design. This preliminary stage, following the processes outlined in Chapter 5, involves assessing the organization's current performance and alignment of design features. It starts with a description of current effectiveness and the extent to which changes in the strategy and organization design elements are required. The organization's new strategy and objectives are examined to determine what organization capabilities are needed to achieve them. For worldwide designs, this involves a careful analysis of the required levels of global integration and local responsiveness. Then, the organization is assessed against these capabilities and requirements to uncover gaps between how it is currently designed and the necessary design changes. This gap analysis identifies current problems the design intervention should address. It provides information for determining which design elements will receive the most attention and the likely magnitude and timeframe of the design process.

2. Designing the organization. This step involves describing and configuring the design components to support the business strategy and objectives. The most effective design sequence is to first identify the work processes and work designs that will best add value to customers and other key stakeholders according to the strategy. Based on these work processes, alternative structures, such as functional, matrix, or customer-centric, should be described and debated among the design team and senior executives. The core structure that best supports the work and strategy should be chosen, although no structure is perfect. Managers need to be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of each structural alternative and be conscious about the tradeoffs. OD practitioners can help managers work through this difficult decision. Once the strategy-structure-work design decisions are made, the next step is to specify the management processes and human resource practices that will compliment and support them. These two design features are well suited to address any weaknesses in the chosen structure. For example, functional structures are good at promoting technical excellence but weaker with respect to coordination. Management processes can be designed to increase the flow of cross-functional information exchange and human resource practices can be designed to reward cross-functional decision making. The resulting design usually falls somewhere along the continuum from mechanistic to organic. A broader set of organizational members often participates in these decisions, relying on its own as well as experts' experience and know-how, knowledge of best practices, and information gained from visits to other organizations willing to share design experience. This stage results in an overall design for the organization, detailed designs for the components, and preliminary plans for how they will fit together and be implemented.

3. Implementing the design. The final step involves making the new design happen by putting into place the new structures, practices, and systems. In all cases, implementation draws heavily on the methods for leading and managing change discussed in Chapter 8 and applies them to the entire organization or subunit, and not just limited parts. Because organization design generally involves large amounts of transformational change, this intervention can place heavy demands on the organization's resources and leadership expertise. Members from throughout the organization must be motivated to implement the new design; all relevant stakeholders must support it politically. Organization designs usually cannot be implemented in a single step but must proceed in phases that involve considerable transition management. They often entail significant new work behaviors and relationships that require extensive and continuous organization learning.

The transition from domestic to global or multinational designs is an important period in an organization's development. It represents a significant shift in strategic breadth even though many firms approach it as a simple and incremental extension of the existing strategy into new markets. Despite the logic of such thinking, the shift is neither incremental nor simple. OD practitioners can play an important role in making the transition smoother and more productive by maintaining a focus on the systemic nature of the change and applying the appropriate human process, technostructural, and human resource interventions. For example, team-building interventions are appropriate in almost every implementation of a worldwide design. The centralized policies of the global design make the organization highly dependent on the top management team, and team building with this group can help to improve the speed and quality of decision making and improve interpersonal relationships. Team building remains an important intervention for the multinational design, but unlike team building in global designs, the local management teams require attention in multinational firms. This presents a challenge for OD practitioners because polycentric selection policies can produce management teams with different cultures at each subsidiary. Thus, a program developed for one subsidiary may not work with a different team at another subsidiary, given the different cultures that might be represented.

Similarly, managers can apply technostructural interventions to design organization structures that clarify new tasks, work roles, and reporting relationships between corporate headquarters and foreign-based units. Finally, managers and staff can apply human resource interventions to train and prepare managers and their families for international assignments and to develop selection methods and reward systems relevant to operating internationally.40

The evolution from a global or multinational to a transnational design is a particularly complex strategic change effort because it requires the acquisition of two additional capabilities. First, global organizations, which are good at centrally coordinating far-flung operations, need to learn to trust local management teams, and multinational organizations, which are good at decentralized decision making, need to become better at coordination. Second, both types of organizations need to acquire the ability to transfer resources efficiently around the world. Much of the difficulty in evolving to a transnational strategy lies in developing these additional capabilities.

In the transition from a global to a transnational design, the administrative challenge is to encourage creative over centralized thinking and to let each functional area contribute and operate in a way that best suits its context. For example, if international markets require specialized products, then operations must configure manufacturing or service capacity to minimize costs but optimize customization. OD interventions that can help this transition include training efforts that increase the tolerance for differences in management practices, control systems, performance appraisals, and policies and procedures; reward systems that encourage entrepreneurship, coordination, and performance at each location; and structural changes at both the corporate office and local levels.

In moving from a multinational to a transnational design, products, technologies, and regulatory constraints can become more homogeneous and require more efficient operations. The competencies required to compete on a transnational basis, however, may be located in different geographic areas. The need to balance local responsiveness against the need for coordination among organizational units is new to multinational firms. They must create interdependencies among organizational units through the flow of parts, components, and finished goods; the flow of funds, skills, and other scarce resources; or the flow of intelligence, ideas, and knowledge. For example, prior to Alan Mulally's appointment as CEO, Ford was operating as a multinational with different divisions in different parts of the world acting independently. Mulally's “One Ford” strategy recognized that its operational assets were not being leveraged. As a result of the strategy, ten different car models now use the same platform and share about 80 of the parts which can be sourced anywhere in the world. The strategy has allowed Ford to offer different looking cars in different markets but to have similar platforms and parts that lower costs.41

18-3 Integrated Strategic Change

As described above, transformational change is systemic and revolutionary in nature. Integrated strategic change (ISC) is an OD intervention that extends traditional OD processes into the content-oriented discipline of strategic management and describes how to conduct a systemic and revolutionary change program. It is an intentional process that leads an organization through a realignment between the environment and a firm's strategic orientation, and that results in improvement in performance and effectiveness.42

The ISC process was initially developed by Worley, Hitchin, and Ross in response to managers' complaints that good business strategies often are not implemented.43 Research suggested that managers and executives were overly concerned with the financial and economic aspects of strategic management.44 The predominant paradigm in strategic management—formulation and implementation—artificially separates strategic thinking from operational and tactical actions; it ignores the contributions that planned change processes can make to implementation.45 In the traditional process, senior managers and strategic planning staff prepare economic forecasts, competitor analyses, and market studies. They discuss these studies and rationally align the firm's strengths and weaknesses with environmental opportunities and threats to form the organization's strategy.46 Then, implementation occurs as middle managers, supervisors, and employees hear about the new strategy through memos, restructuring announcements, changes in job responsibilities, or new departmental objectives. Consequently, because participation has been limited to top management, there is little understanding of the need for change and little ownership of the new behaviors, initiatives, and tactics required to achieve the announced objectives.

18-3a Key Features

ISC, in contrast to the traditional strategic management process, is more integrated, comprehensive, and participative. It has three key features:47

1. The relevant unit of analysis is the organization's strategic orientation comprising its strategy and organization design. An organization's business strategy and the design features that support it must be considered as an integrated whole.

2. Creating a strategic plan, gaining commitment and support for it, planning its implementation, and executing it are treated as one integrated process. The ability to repeat such a process quickly and effectively when conditions warrant is valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate. Thus, a strategic change capability represents a sustainable competitive advantage.48

3. Individuals and groups throughout the organization are integrated into the analysis, planning, and implementation process to create a more achievable plan, to maintain the firm's strategic focus, to direct attention and resources on the organization's key competencies, to improve coordination and integration within the organization, and to create higher levels of shared ownership and commitment.

18-3b Implementing the ISC Process

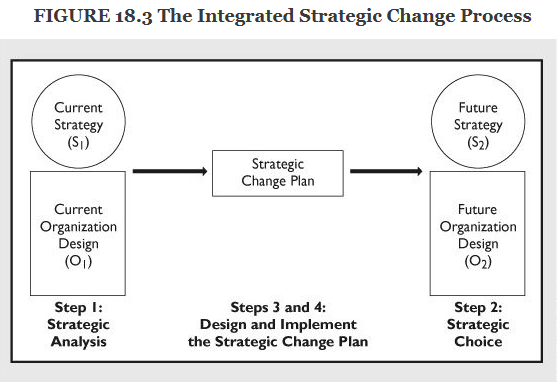

The ISC process is applied in four phases: performing a strategic analysis, exercising strategic choice, designing a strategic change plan, and implementing the plan. The four steps are discussed sequentially but actually unfold in overlapping and integrated ways. Figure 18.3 displays the steps in the ISC process and its change components. An organization's existing strategic orientation, identified as its current strategy (S1) and organization design (O1), is linked to its future strategic orientation (S2/O2) by the strategic change plan.

1. Performing the strategic analysis. The ISC process begins with a diagnosis of the organization's readiness for change and its current strategy and organization design (S1/O1). The most important indicator of readiness is senior management's willingness and ability to carry out strategic change. Greiner and Schein suggest that the two key dimensions in this analysis are (1) the leader's willingness and commitment to change and (2) the senior team's willingness and ability to follow the leader's initiative.49 Organizations whose leaders are not willing to lead and whose senior managers are not willing and able to support the new strategic direction when necessary should consider team-building or coaching interventions to align their commitment. The second stage in strategic analysis is to understand the current strategy and organization design. The diagnostic process begins with an examination of the organization's industry and current performance. This information provides the necessary context to assess the current strategic orientation's viability. Porter's industry attractiveness model50 and the environmental frameworks introduced in Chapter 5 should be used to look at both the current and likely future environments. Next, the current strategic orientation is described to explain current levels of performance and human outcomes. Several models for guiding this diagnosis exist.51 For example, the organization's current strategy, structure, and processes can be assessed according to the model and methods introduced in Chapter 5. A metaphor or other label that describes how the organization's mission, objectives, and business policies lead to improved performance can be used to represent strategy. 3M's traditional strategy of “differentiation” aptly summarizes its mission to solve unsolved problems innovatively, its goal of having a large percentage of current revenues come from products developed in the last five years, and its policies that support innovation, such as encouraging engineers to spend up to 15% of their time on new projects. An organization's objectives, policies, and budgets signal which parts of the environment are important, and allocate and direct resources to particular environmental relationships.52 Intel's new-product development objectives and allocation of more than 20% of revenues to research and development signal the importance of its linkage to the technological environment. The structure, work design, management processes, and human resources system describe the organization's design. These descriptions should be used to assess the likely sources of customer dissatisfaction, product and service offering problems, financial issues, employee disengagement, or other outcomes. The strategic analysis process actively involves organization members. Large group conferences, employee focus groups, interviews with salespeople, customers, and purchasing agents, and other methods allow a variety of employees and managers to participate in the diagnosis and increase the amount and relevance of the data collected. This builds commitment to and ownership of the analysis; should a strategic change effort result, members are more likely to understand why and be supportive of it.

2. Exercising strategic choice. Once the strengths and weaknesses of the existing strategic orientation are understood, a new one must be designed. For example, the strategic analysis might reveal misfits among the organization's environment, strategic orientation, and performance. These misfits can be used as inputs for crafting the future strategy and organization design. Based on this analysis, senior management formulates visions for the future and broadly defines two or three alternative sets of strategies and objectives for achieving those visions. Market forecasts, employees' readiness and willingness to change, competitor analyses, and other projections can be used to develop the alternative future scenarios.53 The different sets of strategies and objectives also include projections about the organization design changes that will be necessary to support each alternative. It is important to involve other organizational stakeholders in the alternative generation phase, but the choice of strategic orientation ultimately rests with top management and cannot easily be delegated. Senior executives are in the unique position of viewing a strategy from a general management position. When major strategic decisions are given to lower-level managers, the risk of focusing too narrowly on a product, market, or technology increases. This step determines the content or “what” of strategic change. The desired strategy (S2) defines the ideal breadth of products or services to be offered and the markets to be served. It also describes the aggressiveness with which these outputs will be pursued and the differentiators to be employed. The desired organization design (O2) specifies the structures and processes necessary to support the new strategy. Aligning an organization's design with a particular strategy can be a major source of superior performance and competitive advantage.54

3. Designing the strategic change plan. The strategic change plan is a comprehensive agenda for moving the organization from its current strategy and organization design to the desired future strategic orientation. It represents the process or “how” of strategic change. The change plan describes the types, magnitude, and schedule of change activities, as well as the costs associated with them. In line with the research on transformational change, the change plan should be aggressive and attempt to complete the required change activities in as short a time frame as possible. As a result, the change plan also specifies how the changes will be implemented, given power and political issues, the nature of the organizational culture, and the current ability of the organization to implement change.55