Lipohaemarthosis of the knee

Content page

Introduction………...…………...…………………………….……………………3

Background…………………………………………………………………. ….…4

Background…………………………………………………………………. ….…5

Case Report…….…….…………………………...……………………………….6

Figure 1…………………………………………………………………………….7

Figure 2…………………………………………………………………………….8

Figure 3…………………………………………………………………………….8

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………9

References…………...…...…...……………………………………………….10-11

Introduction

According to Thawait et al.2012, Lipohaemarthrosis is a joint effusion comprised of synovial fluid with fat and blood. As fat is less dense than synovial fluid the fat floats on the top, which in X-ray images, is detected as fluid-fluid level. pursuant to Tahara et al.2011, the first visualisation of lipohaemarthrosis was made a number of decades ago by horizontal beam technology. The condition arises from trauma, such as an intra-articular fracture that extends from the surface to the bone marrow, allowing fat and blood from the marrow to seep into the joint space, because of the differences in X-ray attenuation of blood components, fat and synovial fluid, cross-sectional imaging techniques, such as CT, can be used to visualise lipohaemarthrosis. As Thawait et al.2012, said that MRI scans are also able to differentiate the various subcomponents of the effusion because blood products, fat and synovial fluid varies in their T1 and T2 relaxation times. Lugo-Olivieri et al.1996 said submit that intra-articular haemorrhage can manifest without fat in the joint cavity; this could be seen as a single fluid-fluid level. The researchers argue that double fluid-fluid level may be specific to lipohaemarthrosis (Lugo-Olivieri et al.1996). When blood enters synovial fluid, it separates with serum floating over haemoglobin- and iron rich- erythrocytes. With the serum’s density being comparable to that of water, it forms the first fluid-fluid level. In lipohaemarthrosis, being less dense than serum fat floats at the top of the effusion, creating another fluid-fluid level. Thus, lipohaemarthrosis is characterised by two fluid-fluid levels; the top-most fluid layer lies between the fat and serum layers, whilst the second fluid-fluid layer occurs between the serum layer and that of the concentration of erythrocytes (Thawait et al.2012).

Background

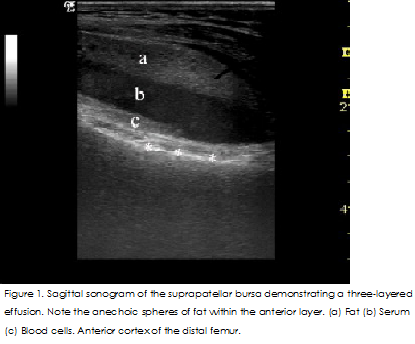

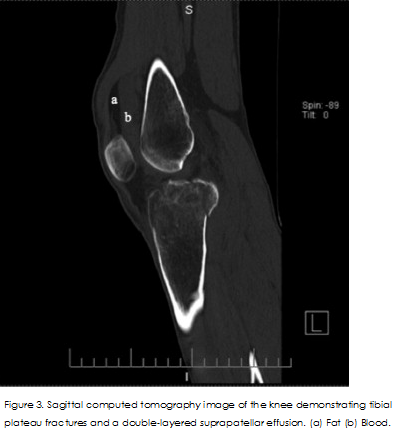

Pallin,2007 and BONNEFOY et at.2006 said that The literature recognises lipohaemarthrosis, as being a dependable predictor of intra-articular fractures. It arises when bones fracture to the marrow, releasing fat from the marrow that escapes into the joint space Conventionally, as lipohaemarthrosis was determined from X-rays as a fat-fluid level on horizontal, cross-table lateral radiographs. However, pursuant to Schick et at.2003 and Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013, it can also be identified through the use of other tomographic and non-tomographic techniques; also there are advantages and disadvantages associated with the different techniques, the Correct diagnosis is important as it determines whether treatment should be surgical or conservative (Schick et at.2003). In ultrasound images, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT Scan, lipohaemarthrosis can be visualised as a single fluid-fluid level, comprised of fat and blood, or as a double fluid-fluid layer with layers of blood cells, serum and fat (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). The fat layer is made up of many fat globules that generate almost no ultrasound echoes. Beneath this is the serum layer, which also does not generate echoes, but the last layer of clotting blood cells does is echogenic (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). Intra-articular knee fractures can be distinguished with high specificity by X-rays but the technology has low sensitivity for lipohaemarthrosis. A study revealed that X-rays were unable to detect fat-fluid levels in 65% of patients with intra-articular fractures, but for 100% of the patients with lipohaemarthrosis detected in their X-rays had intra-articular fractures (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). Lipohaemarthrosis is reliably identifiable by CT and MRI when X-rays find no indication of fracture. Yet not all patients with knee trauma have access to these diagnostic technologies. Research indicates that the distinctive sonographic pattern of lipohaemarthrosis takes time to emerge (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). Using an in vitro blood and oil mix that was subjected to sonography immediately after mixing and thirty mints later, two layers were found in the first image but in the later image, this had increased to three layers. For the clinical aspect of this study, 7 patients whose knee had been immobilised following intra-articular knee fractures received ultrasound scans either twenty mints or three hours after immobilisation. In sex of the patients scanned after 20 min, the effusion appeared as two-layers only. In the patient scanned after three hours, a three-layered effusion was identified (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). According to the study conducted by (Bonneyfoy et al.2006) in 2 patients, no lipohaemarthrosis was detected by ultrasound but CT scans revealed they had intra-articular fractures. The sonograms for these patients were performed within two hours of trauma and this may not have been adequate time for lipohaemarthrosis to progress. There are a number of factors, apart from timing, that ought to be considered when attempting to diagnose lipohaemarthrosis by ultrasound. Chief amongst these is it is important not to mistake the normal pad of fat that lies above the knee for the fat layer of lipohaemarthrosis (Aponte EM, Novik JI, e2013). The fat pad is positioned behind the quadriceps tendon and in front of the suprapatellar bursa. Differentiation of these structures can be achieved by squeezing the joint, which in lipohaemarthrosis will cause the layers in the effusion to mix and the image of the fat-fluid level will blur (Aponte EM, Novik JI, e2013). Another cause for lipohaemarthrosis is rupture of the infrapatellar fat pad. Using lipohaemarthrosis to distinguish between a fracture and a fat pad ruptured by trauma is challenging. It is thought that isolated infrapatellar fat pad rupture due to trauma is rare (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013).

Cause Report

There is a 35-year-old male suffering with pain and swelling of his left knee came to the emergency department. He did not have any previous medical history, but he was Fallen from a height of three meters the day before. Upon physical examination, his vital signs were found to be normal, as were the neurological and vascular systems in his left leg, but there was swelling with effusion in the bursa above the knee (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). There was tenderness when palpating medial and lateral joint lines, as well as at the proximal tibia. Motion of the knee was painful and was limited to zero to forty-five degrees. There was mild laxity with valgus stress compared to the right leg. Anterior-posterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the knee were requested, but equipment failure prevented these images from being obtained (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). In the absence of functioning X-ray equipment, and based upon the belief that the knee had suffered a fracture, the emergency doctor performed bedside ultrasound of the joint using a Thirteen to five MHz compact linear transducer (GE Logiq-e), The patient lay face up, with his knee extended and scans were taken along the axial and sagittal planes of the suprapatellar bursa (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013). Confirmation that the joint had indeed suffered an intraarticular fracture came from visualising a triple layer of fat, plasma and blood cells within the bursa (Figure 1). Once the x-ray machine has been repaired after a few hours, was checked the request card and the patient's history on the hospital information system (HIS) system to check for any previous history and corresponding images, radial image was taken (Figure 2). This revealed an intra-articular fracture of the tibia plateau coupled with a fractured fibula head. A computer tomography (CT) scan of the knee showed that the tibia plateau bone had fractured into more than two pieces, which were impacted. The fracture was classified as grade 5 (Figure 3). The knee was wrapped in a compressive bandage and immobilised. The patient was told not to bear weight on the leg and was given an orthopaedic follow-up appointment. Later in the week, the patient underwent surgery to repair the fracture (Aponte EM, Novik JI,2013).

Conclusion

For an acute injury setting, the associated fracture should be studied so as to investigate more about the fat fluid level found at the knee. The presentation that is most common is Lipohermarthrosis. Besides, extracapsular free fat in the body may also be assessed in rare forms. The acute trauma of bones found at the knee can be evaluated with the aid of knowledge of the imaging patterns that that belong to the floating fat.

References

Aponte EM, Novik JI. Identification of lipohemarthrosis with point-of-care emergency ultrasonography: Case report and brief literature review. J Emerg Med 2013; 44:453-6

Le Corroller T, Parratte S, Zink JV, Argenson JN, Champsaur P. Floating fat in the wrist joint and in the tendon sheaths. Skeletal Radiol 2010; 39:931‑3.

Lugo-Olivieri, C., Scott, W. and Zerhouni, E. (1996) Fluid-fluid levels in injured knees: do they always represent lipohemarthrosis? Radiology. Vol.198(2), pp.499-502. [viewed 30 march2017].Available fromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8596856

BONNEFOY, O., DIRIS, B., MOINARD, M., AUNOBLE, S., DIARD, F. and HAUGER, O., 2006. Acute knee trauma: role of ultrasound. European radiology, 16(11), pp. 2542-8.

Pallin, D. (2007) Images in Emergency Medicine. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Vol.50(2), pp.120-135.

O'Regan KN, Jagannathan J, Krajewski K, Zukotynski K, Souza F, Wagner AJ, et al. Imaging of liposarcoma: Classification, patterns of tumor recurrence, and response to treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197: W37-43.

Shaerf DA, Mann B, Alorjani M, Aston W, Saifuddin A. High-grade intra-articular liposarcoma of the knee. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40:363-5.

Schick, C., Mack, M.G., Marzi, I. & Vogl, T.J. 2003, "Lipohemarthrosis of the knee: MRI as an alternative to the puncture of the knee joint", European radiology, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1185-7.

Tahara, M., Katsumi, A., Akazawa, T., Otsuka, Y. & Kitahara, S. 2011, "Post-traumatic chylous knee effusion", The Knee, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 133-5

Thawait,Shrey K.; Vossen,Josephina A.; Muro,Gerard J.; Karol,Ian Traumatic Lipohemarthrosis of the wrist joint due to a Scaphoid fracture Radiology Case Reports, 2012, 7, 3