Art History

Two Takes on Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1948, both excerpted from longer essays.

Michael Fried, from “Three American Painters” (1965)

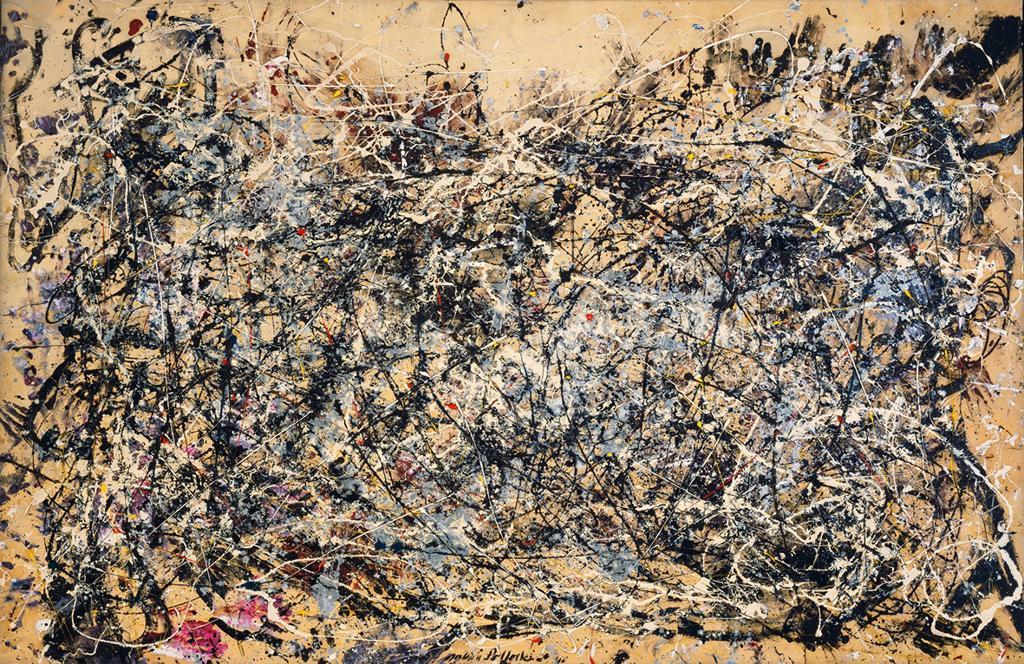

The Museum of Modern Art’s Number 1, 1948, typical of Pollock’s best work during these years, was made by spilling and dripping skeins of paint onto a length of unsized canvas stretched on the floor which the artist worked on from all sides. The skeins of paint appear on the canvas as a continuous, allover line which loops and snarls time and again upon itself until almost the entire surface of the canvas is covered by it. It is a kind of space-filling curve of immense complexity, responsive to the slightest impulse of the painter and responsive as well, one almost feels, to one’s own act of looking. There are other elements in the painting besides Pollock’s line: for example, there are hovering spots of bright color, which provide momentary points of focus for one’s attention, and in this and other paintings made during these years there are even handprints put there by the painter in the course of his work. But all these are woven together, chiefly by Pollock’s line, to create an opulent and, in spite of their diversity, homogenous visual fabric which both invites the act of seeing on the part of the spectator and yet gives the eye nowhere to rest once and for all. That is, Pollock’s allover drip paintings refuse to bring one’s attention to a focus anywhere. This is important. Because it was only in the context of a style entirely homogenous, allover in nature, and resistant to ultimate focus that the different elements in the painting—most important, line and color—could be made, for the first time in Western painting, to function as wholly autonomous pictorial elements.

At the same time, such a style could be achieved only if line itself could somehow be prized loose from the task of figuration. Thus, an examination of Number 1, 1948, or of any of Pollock’s finest paintings of these years, reveals that his allover line does not give rise to positive and negative areas: we are not made to feel that one part of the canvas demands to be read as figure, whether abstract or representational, against another part of the canvas read as ground. There is no inside or outside to Pollock’s line or to the space through which it moves. And this is tantamount to claiming that line, in Pollock’s allover drip paintings of 1947-50, has been freed at last from the job of describing contours and bounding shapes. It has been purged of its figurative character. Line, in these paintings, is entirely transparent both to the nonillusionistic space it inhabits but does not structure and to the pulses of something like pure, disembodied energy that seem to move without resistance through them. Pollock’s line bounds and delimits nothing—except, in a sense, eyesight. We tend not to look beyond it, and the raw canvas is wholly surrogate to the paint itself. We tend to read the raw canvas as if it were not there. In these works Pollock has managed to free line not only from its function of representing objects in the world, but also from its task of describing or bounding shapes or figures, whether abstract or representational, on the surface of the canvas. In a painting such as Number 1, 1948 there is only a pictorial field so homogenous, overall, and devoid both of recognizable objects and of abstract shapes that I want to call it optical, to distinguish it from the structured, essentially tactile pictorial field of previous modernist painting from Cubism to de Kooning and even Hans Hofmann. The materiality of his pigment is rendered sheerly visual, and the result is a new kind of space—if it still makes sense to call it space—in which conditions of seeing prevail rather than one in which objects exist, flat shapes are juxtaposed, or physical events transpire.

T. J. Clark, from “The Unhappy Consciousness,” in Farewell to An Idea (1999)

Number 1, 1948. The painting is 5 feet 8 inches high and 8 feet 8 inches wide. Rounding the corner of the gallery and catching sight of it, I am struck again by the counter-intuitive use it makes of these dimensions. To me it always looks small. Partly this is because it hangs in the same room as One: Number 31, 1950, which measures 8 feet 10 by 17 feet 6. But this comparison is anyway the right one. The canvases Pollock did in 1950—the 15 and 17 footers—define what bigness is, in this kind of painting. And it is not a matter of sheer size. Lavender Mist is only a foot or so longer than Number 1, 1948. Number 1, 1949 is the same length and not quite as high. But I should call both of them big pictures, because what happens within them reaches out toward a scale and velocity that truly leaves the world of bodies behind.

Not so Number 1, 1948. It looks as wide as one person’s far-flung (maybe flailing) reach. The handprints at top left and right of the picture—a dozen in black, a fainter four or five in blood-brown—are marks which seem made all from one implied center, reaching out as far as a body can go. (I am describing the way they look in the finished picture, not their actual means of production.) The picture is fragile. Tinsel-thin. A hedge of thorns. A gray and mauve jewel case, spotted with orange-red and yellow stones. The clouds of aluminum and the touches of pink toward bottom left only confirm the essential brittleness of the whole thing—the feeling of its black and white lines being thin, hard, friable, dry, each of them stretched to breaking point. They are at the opposite end of the spectrum of markmaking from One’s easy, spreading trails. Number 1, 1948 is a thrown painting. One can imagine many of its lines hurled at speed as far as possible from their points of origin. One, by contrast, is more poured than thrown, and more splashed (rained) than poured. Spotted. Strayed. Which does not mean that its surface looks straightforwardly liquid. Finding words for the contradictory qualities of Pollock’s surfaces is, you see already, a tortuous business.

Number 1, 1948 is thrown. Therefore it is flat, with lines hurtling across the picture surface as if across a paper-thin firmament. Shooting Stars. Comets. Once again, as with Malevich, the high moment of modernism comes when the physical limits of painting are subsumed in a wild metaphysical dance. The Manheims’ titles are wonderful on this. And I think the verdict applies even to those aspects of the picture that aim to rub our noses in physicality. For instance, the handprints.

Commentators have argued that one thing the handprints do is make the resistant two dimensions of the canvas come to life again. They show flatness actually occurring—here, here, and here in the picture, at this and this moment. I am sure that is right. But anyone who does not go on to say that there is a histrionic quality to the here and now in this case is not looking at the same picture as I am. Pollock was quite capable of putting on handprints matter-of-factly when he wanted. The ones at the left-hand side of Lavender Mist, for example, are as gentle and positive—as truly repetitive—as handprints can be. They climb the edge of the picture like a ladder. Everything about the prints in Number 1, 1948, by contrast—their placement in relation to the web of lines and the picture’s top, their shifting emphasis and color, their overlapping, the way they tilt to either side of uprightness, the rise and fall of the row they make—is pure pathos, and presumably meant to be. The tawdriest Harold-Rosenberg-type account will do here. Because part of Pollock is tawdry. (It is just that Rosenberg could not see any other part.)

The same goes for flatness conceived as a characteristic of the whole criss-cross of lines. There is no ipso facto reason why a web of lines should be, or look, flat. Often in Pollock it does not. But in Number 1, 1948 flatness is the main thing. Even more than the handprints, this overall quality is what gives the picture its tragic cast. And in a sense, there is no mystery to how the quality is achieved. It is a matter of manufacture. This particular web is built on a pattern of rope-like (literally string-thick) horizontal throws of white, seemingly the first things to be put down; most of them overlain by subsequent throws of black, aluminum and so on; but think enough that they emblematize the physical resting of the paint on a surface just below—a surface wrinkling and flexing into shallow knots, like tendons or muscles under a thin skin. All of Pollock’s more elaborate drip paintings are built in layers, or course. But this quality of the final surface’s being stretched over a harder, spikier skeleton is specific to Number 1, 1948. The layers of One, by comparison, are deeply interfused, and do not look to be on top of the canvas surface so much as soaked into its warp and woof. Even Number 1, 1949, which may look superficially similar to its 1948 partner, is built essentially out of a top layer of flourishes which push the darker under-layers back into space. The aluminum Number 1, 1948 has no such illusory power.

All this, as I say, is unmysterious. It can be described in technical terms. But compare what happens along the painting’s top edge. No viewer has ever been able to resist the suggestion that here is where the picture divulges its secrets, literal and metaphorical. Here is where the thicket of line adheres to the canvas surface—becomes consubstantial with it. And though the handprints tend to be what commentators talk about, they are only part of the effect: they are not what does the adhering: they are one kind of mark among others, less important than the transverse jets of white, and the final loops of white and black, which somehow—improbably, in spite of their wild spiraling back into space—make the thicket flatten and thin out, become papery-insubstantial, and therefore (by some logic I cannot get straight) part of the rectangle.

I cannot get the logic straight because obviously the marks at the top do not pay any literal, formal obeisance to the canvas edge. They meet it, as critics have always said, in a devil-may-care kind of way. (Compare the delicate, essentially circumspect dance along the top of One.) And yet everything they do is done in relation to the final limit. The central black whiplash with its gorgeous bleep of red, and final black spot to the right of it, seal the belonging of everything to easel-size and easel-shape. I do not understand why these—of all shapes and velocities—do this kind of work. Still less why the incident should strike me, as it does each time I see it, as condensing the whole possibility of painting at a certain moment into three or four thrown marks.