M2_A1

Gathering Information

The appropriate use of interview, collateral, and test data in Mr. Smith's case may yield important information about an individual who could be malingering—feigning psychiatric illness for secondary gain. Because he has received disability in the past and has been on treatment units during his incarceration, he is unable to identify a history consistent with the development and onset of the type of psychiatric illness he claims to have. The psychology professional should be questioning whether he is feigning illness for his own benefit.

The initial clue to this possibility is his behavior during the interview—he is not able to give clear descriptions of his psychotic experiences or history and is evasive about his personal and criminal history. It is not typical for someone who suffers from psychosis to be unable to offer a clear description of the nature of the experience. In addition, evasiveness in these types of forensic cases is often seen in clients who do not want to reveal aspects about themselves or their history in contradiction to their claims of psychosis or mental illness.

The second clue is the information found in his collateral sources. He has a history of receiving benefits in both community and criminal justice settings, offered to those who suffer from psychiatric conditions, and there is no evidence to support his suffering from such illness.

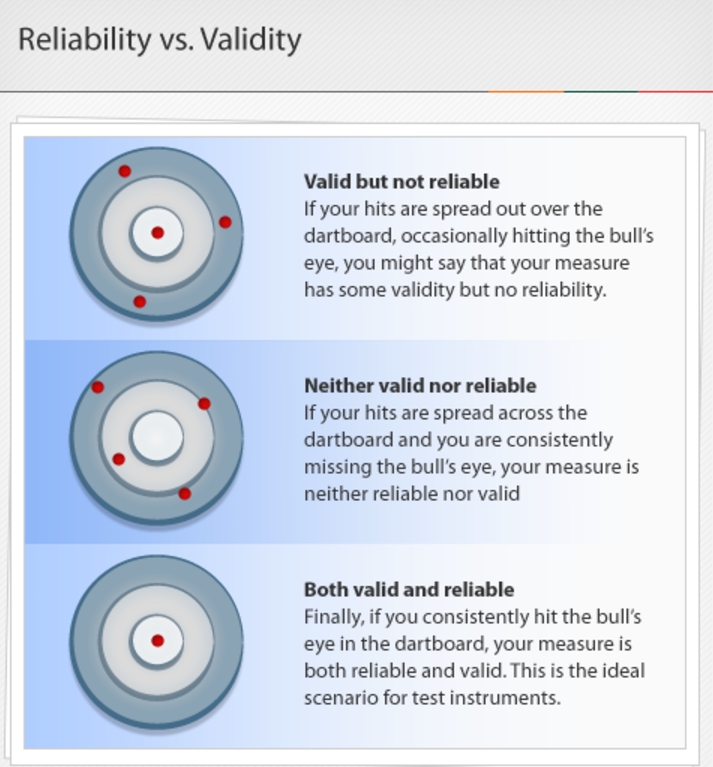

The last determining factor is his psychological test result. He seems to be a person exaggerating psychiatric symptoms and answering test items on the measure in a way to make him seem to be psychiatrically ill. Assuming that your interview skills are well established and that you understand the real presentation of an individual with active psychosis or a history of psychotic symptoms, this portion of the assessment can be deemed valid and reliable. If your collateral sources of information are legitimate, you have good evidence and support for a possible feigning of psychiatric illness for secondary gain when compared to interview and testing data, and this part of your assessment is probably valid and reliable. If you used a psychological test normed, validated, and tested for reliability within the forensic population of which Mr. Smith is a part, your test data can be considered valid and reliable. This data, combined with the other sources of information (interview and collateral information), suggests that your assessment and report are valid and reliable and appropriate to submit to the court. Because all sources of information came from valid and reliable sources, your forensic assessment would be appropriate and defensible in court, would eliminate the possibility of misappropriation of benefits, and would better inform the treatment needs of this individual, who may be depressed or have sociopathic tendencies and antisocial personality traits. He would not have to be exposed to the potentially harmful effects of medication that he would not need, and treatment providers would have a clearer direction on what types of psychological interventions to use with him.

Intellectual and Organic Factors

You will be introduced to the intelligence and organic factors that contribute to criminal activity. You will learn about how important it is to know an individual's mental competencies when assigning him or her punishment or treatment and when determining his or her intent in the commission of crimes.

Often, cognitive (e.g., intelligence), genetic, and organic factors contribute to criminal activity. Discerning between organic and personality factors in the commission of crimes can be a challenging task for law enforcement, courts, and psychology professionals. This module will also introduce you to some of the intellectual and organic factors common among criminal offenders and the assessment procedures and psychological instruments often used to determine the presence of such conditions.

It is important to know an individual's mental capacities when assigning him or her punishment or treatment and when determining his or her intent in the commission of crimes. Punishing someone for a criminal offense committed because of intellectual deficits, organic personality factors, or episodes of brain abnormality is basically penalizing that individual for biological and genetic factors beyond his or her control. Just as people do not choose to have cancer, they do not necessarily choose to have low intellectual capacity or brain abnormality, resulting in loss of impulse control and a display of excessive aggression toward others in the community. The legal and mental health communities have to treat these cases with special concern to be fair in the assignment of punishment.

While learning disabilities have primarily been the specialized focus of educational psychology professionals, they have been receiving more attention lately among forensic mental health professionals because of the high incidence of learning-disabled inmates. Often, frustration because of academic failures and the limited employment opportunities for individuals with learning disabilities result in criminal behavior. This behavior arises not only because these individuals are unable to understand the basic rules but also because their lack of employment limits their ability to obtain necessities and material items. To punish these individuals in the same manner as individuals committing crimes with intent and knowing right from wrong is to punish them for deficits beyond their control. This is why determining the intellectual capacity of these criminal offenders is important when assigning punishment. In addition, these individuals may be better served with community services, such as vocational rehabilitation and educational programs.

Intelligence Testing

Intelligence testing plays an important role in forensic assessment. In some criminal cases, an individual might have intellectual difficulties that may have contributed to his or her crime. For example, an uncle had taught his adult nephew to steal small high-priced electronics, which the uncle would then sell online and profit from. His nephew was mentally challenged, meaning he had an intellectual disability, or a low intelligence quotient (IQ). His nephew thought that taking things from stores was not wrong because it was for his uncle who had told him to do it. According to our legal system, it would not be appropriate to view this individual in the same way as other adults of average intelligence.

In many cases, intelligence tests are needed to determine whether someone is trying to malinger in order to avoid responsibility for his or her crime. In the case of Mr. Smith, intelligence testing would likely produce some information in regard to his malingering. For example, if Mr. Smith is unable to perform some basic tasks, such as adding small numbers (2 + 2), spelling short words (D-O-G), or writing his name, he is probably malingering by trying to make himself seem cognitively impaired since someone who could not complete such extremely basic cognitive skills probably could not carry out a crime of aggravated robbery or the sophisticated crimes of fraud that Mr. Smith has engaged in. In this example, collateral historical data and testing data work in tandem to produce a clear picture of the individual.

Intelligence testing is used in civil cases as well. For example, an individual with an intellectual disability who has a child might need to undergo a parent fitness evaluation that would involve an intelligence test to determine whether his or her level of intellect might interfere with his or her ability to parent. Intelligence testing is also used in disability cases to determine whether an individual might be pretending to have some type of cognitive impairment to qualify as having a disability. Since there are strong financial incentives on being awarded a disability status, intelligence testing is an excellent way to determine whether malingering is occurring.

Phases of Clinical Assessment

The following are the phases in clinical assessment. In the assessment process, most evaluations will follow these steps:

Evaluation of the referral question

Understanding of the context of referrals and assessment

Collation of knowledge of the current problem

Identification of the nature of the problem

Creation of a theoretical framework

Identification of methods of assessment

Collection of data and third-party information

Proceeding through each step thoroughly will probably yield a more comprehensive evaluation.

Evaluation of the Referral Question

Clinical assessment begins before even meeting the individual to be tested because upon the initial review of the referral, the evaluator must contemplate the relevance of the referral question. For example, is someone being referred for a substance abuse evaluation because his or her charges are related to selling drugs? If so, the referral question may need to be reexamined because people who sell drugs do not necessarily have substance abuse issues themselves. If someone is being referred for an evaluation to assess for psychopathy when he or she is charged for minor shoplifting, more data would be needed to determine whether the referral question was applicable since petty shoplifting is not indicative of psychopathy. Essentially, the evaluator must determine whether the referral question is appropriately tailored to the specific circumstances of the individual.

Understanding of the Context of Referrals and Assessment

In the context of referrals, the most important question to consider is who is requesting the evaluation, such as a family member, an attorney, the individual being evaluated, an employer, or the court. For example, if family members are requesting an evaluation of a family member with serious, violent charges to determine whether any mitigating circumstances may have played a role in the person's offense, collateral data from the family might need to be scrutinized closely as the family might be motivated to manipulate it in the hopes of a favorable evaluation.

Collation of Knowledge of the Current Problem

This aspect of assessment attempts to ascertain what is known about the problem at hand. Essentially, how long has the problem been occurring? In cases of malingering, either psychotic symptoms or an intellectual deficit, it is particularly important to determine when the issue began and when it became worse. For example, when interviewing a victim of domestic violence, it is important to ask when the first incident, the worst incident, and the most recent incident of abuse occurred to get a full picture of the problem.

Identification of the Nature of the Problem

The nature of the problem in assessment focuses on the extent of the issue at hand. Essentially, this question concerns the severity of the problem. For example, if someone has had symptoms of psychosis for years that are now under control with medication, he or she could very well be found competent to stand trial if his or her current disorder is not interfering with his or her ability to function. Therefore, an evaluator must carefully consider more than just a diagnosis when making recommendations and conclusions. The evaluator must gauge the impact of the severity of the symptoms on the individual's behavior.

Creation of a Theoretical Framework

In this component of assessment, an evaluator makes reasonable estimations about the possible conclusions of the test data. While the evaluator's thoughts about the possible results of the evaluation should never override the actual results, an idea about the possible results can serve to shape testing. For example, if historical reports indicate that an individual has had numerous psychiatric hospitalizations over the years due to symptoms of psychosis related to auditory hallucinations and bizarre delusions, the evaluator will begin to consider that the person may have been psychotic at the time of his or her offense. Conversely, if an evaluator observes a person who is very socially engaged and animated in the psychiatric unit but is very withdrawn, dismissive, and mumbling to himself or herself during the evaluation, the evaluator might begin to consider that testing results will indicate malingering since there are such variations in the person's behaviors. Nonetheless, the bulk of the evaluator's conclusions must be based on reliable, objective test data rather than a subjective hypothesis, since speculation can leave room for doubt in court.

Identification of Methods of Assessment

Testing is one method of clinical assessment, but it is not the only method. A clinical interview is also a useful method of assessment. Whether the clinical interview is structured or unstructured, it is a valuable opportunity for the clinician to make direct observations about the person he or she is evaluating. For example, a methamphetamine user may have scabs on his or her face and look much older than his or her stated age. A smoker will have wrinkles around his or her lips. Someone with cognitive impairment or dementia may have his or her shirt buttoned in a mismatched way or the shirt may be inside out. A homeless person might be dressed inappropriately for the weather, for example, may be wearing a coat in summer because he or she has no residence for storing the same. When you know what to look for, there is much to see. Nonetheless, the data from the clinical interview is subjective data, which inherently has its limitations.

Collection of Data and Third-Party Information

In addition to the clinical interview, collateral data is also obtained. Collateral data consists of information from outside sources, such as hospital staff, correctional staff, doctors, family members, and therapists. To complete a forensic evaluation, all of the data from the clinical interview, collateral sources, and testing results are compiled to establish a clear picture of the individual, his or her disorder, if any, and circumstances that may have influenced his or her behavior. Typically, the clinical interview and collateral information are considered to be of secondary importance to the information from the actual tests because test data is objective, which means that it is free from personal bias. No matter how reliable they might seem, the clinical interview and collateral information are considered to be subjective sources of data. For example, in a substance abuse evaluation of a teenager, family members might inaccurately report the amount of alcohol that the adolescent is consuming either because they are unaware of the scope of the problem or because they are apprehensive about being blamed for it.

Analyzing the Data

Psychometrics and Test Development

Tests used in forensic assessment must be valid in the sense that they must measure what they are supposed to measure. For example, giving someone a memory test in his or her nonnative language would probably be more of a language test than one of memory since his or her difficulty in remembering words might simply be due to not knowing them in the first place.

Validity in Forensic Testing

Consider the following case for an illustration of the issue of validity in forensic testing:

Ms. Williams is a thirty-two-year-old mother of two young children and is currently incarcerated for possession of illegal substances. While in prison, she seems to be having difficulty concentrating and following short, simple directions from prison staff. She is referred for intelligence testing to determine whether she has any cognitive limitations. Results of the intelligence test indeed show low scores. However, before making a conclusion of intellectual disabilities, her evaluator administers the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess the presence of the sad effect. Her BDI scores are indeed quite high.

Assessment, Descriptive, and Inferential Statistics

As tests are developed, statistics are required in order to interpret the data and make sense of it. Descriptive statistics are used to summarize the data. For example, if in the development of a test for neurological functioning, the test is administered to a sample of three thousand people, the descriptive statistics would provide a summary of the sample on gender, ethnicity, and age. Descriptive statistics can also yield information on whether the sample had anomalous data (outliers) or whether it was normally distributed.

Descriptive statistics related to the sample can be useful in providing information on whether the test can be used on various demographic groups, that is, whether the sample is representative of the entire population. For example, initially, many intelligence tests were developed using a predominantly Caucasian sample and when those tests were administered to non-Caucasian groups, their intelligence levels seemed lower because the test was culture specific due to the homogeneity of the normative sample. Since no one culture or ethnicity is more intelligent than others, the phenomenon of differences in scores according to ethnicity sheds light on the need of developing more sophisticated, generalizable intelligence tests, which more accurately measure intellect rather than cultural knowledge.

Inferential statistics are also used in test development. As the name implies, inferential statistics are used to make inferences and draw conclusions about a data set by discerning differences between groups. Most importantly, they are used to determine whether the results for the normative sample on which the test was developed were likely to have occurred by chance. Using the above example, in the development of a test for neurological functioning that uses a sample of three thousand people, inferential statistics could determine whether the test was effective in identifying the differences between groups of neurologically impaired individuals and nonimpaired individuals, specifically whether differences between those groups were likely to have occurred by chance (as a fluke). If inferential statistics can show that the differences did not occur by chance, then it means that the test can successfully differentiate between neurologically impaired and nonimpaired individuals.

Conclusion

The psychometrics involved in test development are essential for ensuring that a given psychological test measures what it is supposed to measure and that it is generalizable, which means that it can be used on various types of populations. When a specific test is normed on a nondiverse group, the test should be avoided on individuals who are outside of the normative group. Also, the chosen test should be valid as an evaluator needs to have confidence that the test measures what it is intended to measure. The evaluation should also include collateral data and a clinical interview in order to supplement, but not as a substitute for, essential objective testing data, which is tantamount to making conclusions and recommendations in a report.

Further, intelligence testing plays an important role in forensic assessment for determining whether a person's intellectual deficiencies might have played a role in his or her crime, which would lead to a different treatment in the penal system than if he or she had full intellectual capacity. Intelligence testing is also crucial in detecting malingering in cases where offenders try to make themselves appear to have limited cognitive functioning in an attempt to avoid accountability for their crimes.